Amalgamated Bank: America's Only Union-Owned Bank

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

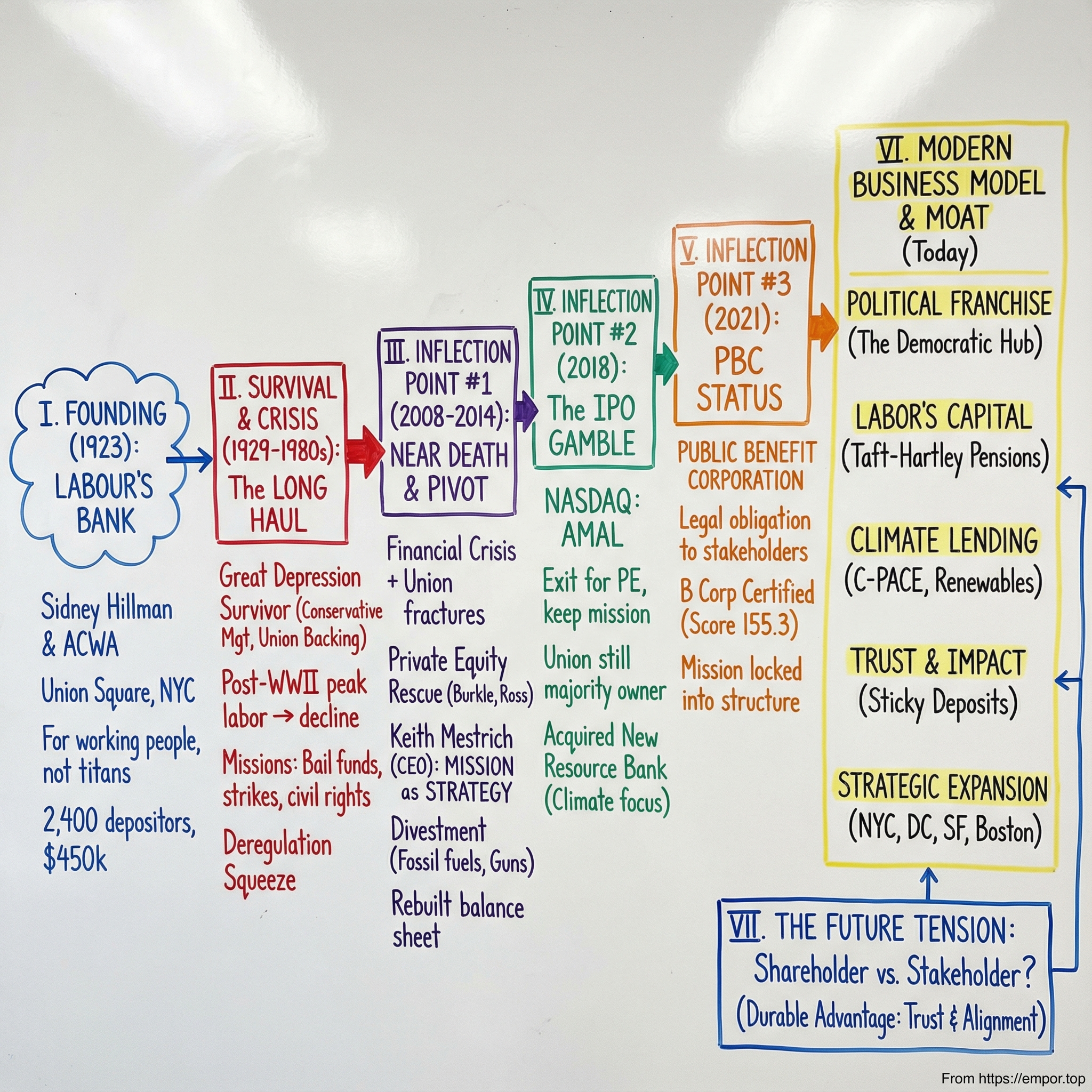

Picture this: it’s April 14, 1923. A small bank opens its doors on East 14th Street in Manhattan, right off Union Square, next to what had once been a Tiffany’s location. And almost immediately, something unusual happens. People pour in.

In short order, about 2,400 depositors bring roughly $450,000 to this brand-new institution. Within weeks, the bank has to take over space upstairs just to keep up.

And here’s the twist: this isn’t a Wall Street project. The founders aren’t titans of finance. They’re garment workers—many of them immigrants—organized under a Lithuanian-born labor leader named Sidney Hillman. Hillman’s premise was simple and radical for the era: working people deserved the same access to safe, fair banking that industrialists took for granted.

Fast forward more than a century, and that improbable bank is still here. Amalgamated Bank has grown into the largest union-owned bank in the United States, and one of the only unionized banks. As of July 30, 2023, it reported $7.8 billion in assets. But the headline isn’t just longevity. It’s reinvention: Amalgamated didn’t merely survive modern finance—it found a lane that turned its identity into an advantage, becoming a progressive banking powerhouse and, in practice, a key financial hub for Democratic politics.

So that’s the central question for this story: how does a 100-year-old labor bank make it through deregulation, survive crises, go public, and still operate as a mission-driven institution that banks political campaigns, climate initiatives, and advocacy organizations—while remaining majority-owned by a union?

Along the way, we’ll keep coming back to a set of tensions that feel extremely modern: Can a company serve two masters—shareholders and society—without tearing itself apart? Can authentic mission become a durable competitive edge instead of a feel-good slogan? And what happens when your political identity isn’t just culture, but strategy?

Because there is one arena where Amalgamated seems to face remarkably little competition: progressive politics. In mid-September 2019, the campaigns of the top five Democratic presidential candidates—former Vice President Joe Biden, Senators Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and Kamala Harris, and South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg—all banked with Amalgamated. When that many top-tier campaigns choose the same bank, it’s a sign the product isn’t just checking accounts. It’s trust, expertise, and infrastructure competitors can’t easily copy.

That’s what makes this story so compelling for investors and business strategists: a publicly traded bank that explicitly prioritizes stakeholder impact; a deposit base that can swell and shift with election cycles; and a century-old institution that has reinvented itself more than once without abandoning the core idea it was founded on. Let’s dig in.

II. Founding Context: The Amalgamated Clothing Workers & Labor Banking Movement

To understand Amalgamated Bank, you have to start with Sidney Hillman—because the bank is essentially Hillman’s worldview turned into a balance sheet.

Hillman was born in Žagarė, Lithuania—then part of the Russian Empire—on March 23, 1887, to Lithuanian Jewish parents. His family background carried two threads that would define him: on one side, a maternal grandfather who was a small-scale merchant; on the other, a paternal grandfather who was a rabbi, known more for piety than for any interest in money.

His life turned on politics. After the failed 1905 revolution, Hillman became the kind of person the czar’s regime liked to make disappear. In late 1906, he fled Russia to avoid persecution, and the following year he arrived in the United States. He settled in Chicago and got work as an apprentice cutter in a garment factory—an existence defined by long hours and harsh conditions.

Then came the break. On September 22, 1910, a small group of women, including Hillman’s future wife, Bessie Abramowitz, walked off the job. The walkout detonated into a mass strike; by late October it had roughly forty-five thousand participants, Hillman among them. In the chaos, Hillman stepped into leadership—negotiating with factory heads and urging workers toward a settlement.

The strike succeeded. Hillman never went back to the factory floor.

A few years later, he helped lead a break from the conservative United Garment Workers union. Many locals had affiliated with the UGW, but by 1914 dissatisfaction boiled over. Insurgent locals formed a new national organization: the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, or ACWA. At the founding convention, delegates chose Hillman as president. Under his leadership, ACWA became the leading garment union in the men’s clothing industry.

But Hillman wasn’t building a union in the narrow sense. As president of ACWA from 1914 to 1946, he pushed a form of “constructive cooperation” between labor and garment firms—meant to stabilize the industry while raising worker standards. He championed dispute-resolution systems that foreshadowed modern grievance and arbitration procedures, and he treated political education and action as core union work, not an afterthought. Most importantly, he believed the union should serve members not only on the job, but in the rest of their lives too—through benefits and community services.

That philosophy leads straight to Amalgamated Bank. In 1923, Hillman and ACWA’s leadership decided that working families should have the same access to fair, affordable banking that big businesses and wealthy people already enjoyed.

And the moment was right. The post–World War I era saw a brief boom in “labor banking,” with unions creating their own institutions for members who were often excluded—or exploited—by traditional finance. Dozens of union-affiliated banks appeared across the country.

ACWA founded Amalgamated Bank in 1923 with $500,000 in resources and 1,300 depositors on opening day. Almost immediately, the bank started doing things mainstream banks simply weren’t doing for working people. The year after it opened, it introduced the nation’s first unsecured personal loans—something that looks a lot like the ancestor of today’s credit cards. It offered the city’s first free checking accounts. And it created a foreign-exchange transfer service for immigrants who needed to send money back to family overseas.

Hillman still wasn’t satisfied. The bank wasn’t the end goal; it was one tool in a broader blueprint. The Amalgamated Housing Cooperative in the Bronx became the first limited equity housing cooperative in the United States, funded and inspired by Hillman and Abraham Kazan. Add in unemployment insurance programs and other union-backed services, and a pattern emerges: these weren’t isolated initiatives. They were components of Hillman’s version of capitalism—one where workers weren’t just labor inputs, but participants in stability and prosperity.

Even the bank’s early leadership signaled what it was. In the Liberator magazine, the bank advertised that it was owned and operated by the Amalgamated Clothing Workers. It listed chairman Hyman Blumberg, president R. L. Redheffer, vice president Jacob S. Potofsky, cashier Leroy Peterson, and directors including Gold, Sidney Hillman, Max Lowenthal, August Bellanca, Fiorello H. La Guardia, Abraham Miller, Joseph Schlossberg, Murray Weinstein, Max Zaritsky, and Peter Monat. And yes—this was the same Fiorello H. La Guardia who would later become New York City’s legendary mayor, sitting on the board alongside union organizers and immigrant-community leaders.

This founding context matters because it set the bank’s DNA. Amalgamated wasn’t built to maximize shareholder returns. It was built to serve a community that mainstream capitalism routinely ignored—and to prove that a financial institution could be run for workers, not around them.

III. Survival Through Crisis: Depression, War, and the Death of Labor Banking

The labor-banking boom of the 1920s had the energy of a movement. Then the Great Depression arrived and turned it into a mass grave.

Between 1929 and 1932, roughly five thousand banks collapsed. By 1933, nearly half of America’s banks had failed. Union banks didn’t get special treatment; they failed right alongside everyone else. Most disappeared completely, taking depositors’ savings—and the idea of worker-owned finance—with them.

Amalgamated didn’t.

That survival wasn’t luck. It came down to a few instincts that would quietly define the bank for decades.

First: conservative management. While other labor banks chased expansion or took bigger bets to prove they could play in the same league as commercial banks, Amalgamated stayed disciplined—tight geography, careful lending, and a preference for safety over flash. Even much later, by 1977, it still looked like a bank that valued staying power: four branches in the New York area and $720 million in assets, with about 90% allocated to the basics—cash, loans, and securities.

Second: union backing. In a bank run, confidence is currency. Amalgamated had something most banks didn’t: depositors who felt they owned the place, culturally if not literally. When panic hit and faith in “the system” evaporated, workers trusted their institution in a way they never trusted Wall Street.

Third: mission-aligned deposits. Customers weren’t there to squeeze out the last bit of yield. They were there because the bank stood for something. That made deposits stickier than the rate-chasing money that runs at the first sign of trouble.

And through the Depression, that original purpose held: affordable, accessible banking for immigrant workers and their families—people who were often ignored, or outright shut out, by mainstream finance.

After World War II, the story gets paradoxical. Organized labor reached peak influence and membership in American life, but labor banking as a broader concept essentially vanished. Amalgamated kept growing anyway, in its steady, unglamorous way. By 1962, it had $115 million in assets and served around 30,000 depositors and borrowers. When the bank marked its 40th anniversary in 1963, it was notable not because it was the biggest, but because it was still standing—one of the few union-owned banks to make it through the Depression and the economic shifts that followed, while staying focused on the working-class customers larger institutions often overlooked.

Meanwhile, the union behind the bank kept evolving. In 1976, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers merged with the Textile Workers Union of America to form ACTWU. More mergers followed, and the clothing workers rebranded as UNITE. In 2004, UNITE merged with HERE to create UNITE HERE—a marriage that soon got complicated, including a break from the AFL-CIO and a move into the rival Change to Win federation led by SEIU and the Teamsters.

Through all of it, the bank stayed what it had always been: a financial backstop for movements.

There are stories that sound almost mythic, but they’re part of Amalgamated’s operating history. On one Saturday, it opened its vaults to provide $300,000 in bail for striking workers. The NAACP received $800,000 to post a cash bond within 24 hours. In 1982, during a strike, Amalgamated made a $200,000 loan to the NFL Players Association—even though the union didn’t even have an account at the bank.

That’s not standard banking behavior. But it’s perfectly logical if you understand what Amalgamated believed it was: an institution designed to keep causes alive when money gets weaponized against them. When Philadelphia teachers went on strike in 1973, bank employees worked through the weekend to process bail for arrested workers. When the NFL players needed emergency funds, Amalgamated didn’t lead with paperwork. It led with solidarity.

By the 1980s, though, that identity ran into an existential problem. The core constituency was shrinking. Private-sector union membership was falling fast. And deregulation was reshaping banking into a scale game—one that punished small, mission-driven players who couldn’t spread costs or compete on flashy new products.

Amalgamated had survived the Depression. The next test was different: not a sudden crash, but a slow squeeze. Could a union bank built for working people survive the Reagan era and a banking industry racing toward consolidation?

IV. Inflection Point #1: The Workers United Acquisition & Strategic Pivot

The late 2000s hit Amalgamated with a one-two punch that nearly ended the story—and then forced it to evolve.

The first blow was political and internal. As UNITE HERE fractured, control of the bank shifted to the SEIU through its affiliate, Workers United. UNITE HERE went on to rejoin the AFL-CIO. Amalgamated, meanwhile, was suddenly navigating new ownership dynamics at exactly the wrong moment.

Because the second blow was the financial crisis. When the housing bubble burst, Amalgamated got caught with subprime and real estate exposure that went sour. Over the following years it had to write off roughly $150 million in troubled loans. Losses mounted, including more than $12 million in 2011, and regulators began pressing hard: clean up the balance sheet, raise capital, or risk being seized and shut down.

For a bank created to protect working people from the failures of the system, the threat was grimly symbolic. After nearly a century of threading the needle through American finance, Amalgamated was staring down the possibility that the government would simply take it away.

The rescue, when it came, was unlikely. In April 2012, Ron Burkle’s Yucaipa Cos. and Wilbur Ross’s WL Ross & Co. each put in $50 million, together ending up with about 41% of the bank. The politics made for strange bedfellows—Burkle was a Democratic fundraiser with labor ties; Ross would later become Commerce Secretary under President Trump. But both had reputations for investing in unionized businesses and working alongside labor to preserve jobs in struggling industries.

The deal bought Amalgamated time. Workers United remained the majority owner, and union leaders kept majority control of the board. But the message was clear: private equity doesn’t invest for nostalgia. If Amalgamated was going to justify that capital—and survive long term—it needed a strategy that didn’t depend on a shrinking pool of traditional union banking alone.

That’s where Keith Mestrich comes in. Mestrich had spent four years as chief financial officer at the SEIU. He joined Amalgamated in 2012 to run its Washington office, and he arrived with a specific mandate: expand the bank’s political business beyond unions. In June 2014, he became CEO and president, and pushed even harder to broaden the franchise to organizations and businesses that shared the bank’s social and environmental priorities.

Mestrich’s insight was simple and contrarian: the bank’s progressive identity wasn’t just a mission. It could be a differentiator. If you made values real—operationally, not rhetorically—you could win customers who weren’t choosing a bank based on a tiny difference in rates.

The pivot started with actions that were small in balance-sheet terms but huge in signaling. Amalgamated divested from fossil fuels, gun manufacturers, and private prisons—moves that were far from mainstream at the time. Mestrich was explicit about it: Amalgamated would not use its money to support gun manufacturers or domestic oil production.

At the same time, he did the unglamorous work of rebuilding a bank. He reengineered the balance sheet by shedding hundreds of millions of dollars in indirect commercial and industrial loans bought from other originators—improving asset quality in the process. And he worked to replace high-cost borrowings with low-cost core deposits by refocusing the bank on bringing in the kinds of long-term, mission-aligned customers it was uniquely positioned to serve.

The turnaround showed up in the fundamentals. Net interest margin improved from 2.55% in 2014 to 3.66% by the second quarter referenced, and noninterest-bearing deposits reached 46% of total deposits for that quarter.

By 2018, Amalgamated wasn’t just a union bank that had survived another crisis. It had become something rarer: a bank rebuilding itself around the idea that mission could be strategy—and that, if you did it credibly, it could actually make the business stronger.

V. Inflection Point #2: The IPO Gamble

The private equity investors who helped save Amalgamated in 2012 were never going to be permanent partners. They wanted an exit. But a straightforward sale came with an obvious fear: new owners could treat Amalgamated like just another community bank, and the mission would become optional—if it survived at all. So the bank faced a question that was as philosophical as it was financial: how do you give investors liquidity without giving up control of what makes you you?

Amalgamated’s answer was weirdly clean: go public.

The IPO raised no new capital. Instead, it was structured largely as an exchange of shares—essentially a controlled release valve that let the private equity backers start getting out without forcing the bank into a “highest bidder wins” process. As Keith Mestrich put it, “We’re not a great sales candidate.”

The logic was almost elegant. Public markets could absorb the shares. Workers United could still keep a substantial stake and meaningful board influence. And the mission would be defended by governance and culture, not by clinging to a permanently closed ownership structure.

Before the IPO, Amalgamated made a move that strengthened the story it would take on the road: it merged with New Resource Bank in San Francisco. Based on each bank’s financial statements as of March 31, 2018, the combined institution would have about $4.5 billion in assets and $41.0 billion in assets under custody and management. New Resource, founded in 2006, had built its brand lending to sustainability-focused businesses and nonprofits. The combination didn’t just add scale—it added a West Coast footprint and a deeper bench in impact banking. Suddenly Amalgamated wasn’t just New York and Washington. It could credibly say it was building a national platform for mission-aligned organizations.

In August 2018, Amalgamated went public on the NASDAQ under the ticker “AMAL.”

Workers United and certain affiliates, along with funds affiliated with WL Ross & Co. LLC and The Yucaipa Companies, LLC, sold 7.7 million shares of Class A common stock in the IPO, including 1.0 million shares sold through the underwriters’ option, at $15.50 per share. The total offering size was $120 million. As a result, Workers United and affiliates reduced their stake from 55.2% to 41%. The union was still the largest shareholder—but now the bank also lived under the constant grading of quarterly earnings calls and market expectations.

For management, the upside wasn’t just the exit. It was what being public unlocked. As Mestrich argued, having a liquid currency—publicly traded stock—created flexibility for future growth, especially through acquisitions, and made the idea of a true national footprint feel achievable.

Of course, the IPO didn’t magically resolve the tension at the heart of the company. If anything, it made it more visible. Could a bank built around stakeholder values satisfy public shareholders? Early market reception suggested a complicated answer: Amalgamated’s mission wasn’t always appreciated by Wall Street. In the years after the IPO, the stock price barely moved and it traded at a discount to peers.

But by the standard that mattered most inside the building, the deal worked. It created the off-ramp Ron Burkle and Wilbur Ross had been promised, without forcing Amalgamated to sell itself to someone who might strip the mission for parts. Burkle and Ross had each bought roughly 20% stakes for $50 million in 2012; filings later showed Ross’s firm sold its remaining shares in late 2020, after he served as President Donald Trump’s commerce secretary.

The private equity investors made their money. The union kept a major stake. The mission survived the liquidity event. And public markets got something rare: a chance to own shares in a bank that wasn’t trying to pretend values were a marketing line—it was trying to prove they could be a business model.

VI. Inflection Point #3: Becoming a Public Benefit Corporation

Three years after going public, Amalgamated made the move that took its mission from culture to contract. On March 1, 2021, it completed a holding company reorganization and, in the process, became the first publicly traded financial institution to be organized as a Delaware public benefit corporation, or PBC. In plain terms: the bank didn’t just say it cared about impact. It hardwired that commitment into its corporate structure.

The reorganization made Amalgamated Financial the parent bank holding company of Amalgamated Bank. That sounds like legal plumbing, and it is—but it mattered. A holding company structure can create more flexibility to pursue strategic opportunities for long-term growth. It can also open up additional ways to raise capital and provide more room to engage in certain non-banking financial activities.

But the headline was the PBC status. As a PBC, Amalgamated is still a for-profit company. The difference is that it is explicitly required to consider the impact of its decisions on more than stockholder return—including workers, customers, suppliers, community, the environment, and society.

That’s a direct response to the core tension of being a mission-driven public company. In a traditional corporate structure, directors face fiduciary duties that put shareholder value first. If purpose and profits collide, mission can get treated like a nice-to-have. The PBC framework changes the rulebook: it gives directors legal permission—really, a legal obligation—to balance stakeholder interests, even when the most profitable short-term path might point elsewhere.

As the company framed it at the time, “Our incorporation as a benefit corporation will enable us to consider the social and environmental impacts of our business when making key corporate decisions, while the holding company structure will provide us with increased flexibility to pursue strategic opportunities to drive long-term growth.”

Public benefit corporations aren’t a novelty in the abstract; they’re recognized in 38 states and the District of Columbia. What made Amalgamated unusual wasn’t that it became a PBC—it was that it did so as a publicly traded financial institution.

The bank also carried another credential that reinforced the point: B Corp certification, a third-party assessment of social and environmental performance. On the B Impact assessment, Amalgamated Bank scored 155.3. The median score for ordinary businesses completing the assessment was 50.9—meaning Amalgamated landed at more than triple the median.

Strategically, the PBC conversion did more than protect the mission on paper. It signaled credibility to customers who might otherwise wonder if “values” would survive life as a public stock. It helped attract talent who wanted their priorities embedded in governance, not just written on a careers page. And it acted as a defense against hostile takeovers or activist shareholders pushing a pure profit-maximization agenda.

None of this guaranteed Amalgamated would be more or less profitable. But it could make the bank more competitive where it actually plays: winning trust from people and institutions that care about what their bank enables.

The bigger question still hung in the air: can you truly serve shareholders and stakeholders at the same time? Amalgamated’s answer wasn’t a slogan. It was a legal bet that stakeholder capitalism could be strategy, not theater.

VII. The Political Banking Franchise: Building an Unassailable Moat

Here’s where Amalgamated’s story gets genuinely unusual. Most banks compete on rates, convenience, and technology. Amalgamated built a franchise around something far harder to copy: political identity, operationalized into a product.

In modern campaign banking, two community banks have emerged as the go-to institutions for national politics: Chain Bridge Bank on the Republican side, and Amalgamated on the Democratic side. Federal Election Commission data shows both outcompeting far larger banks in this niche.

During the 2023–2024 election cycle, roughly 1,100 committees listed Amalgamated as their first bank, and about 1,000 listed Chain Bridge. Compare that with nearly 800 for Bank of America and around 500 for Wells Fargo. Two community banks beating two of the biggest banks in America isn’t an accident. It’s what specialization looks like when the brand is credible and the service is built for the customer’s reality.

Amalgamated spent the last decade deliberately building a business to serve what Priscilla Sims Brown called “the industry of politics”—not just on Election Day, but through every phase of a campaign, from organizing to the final media blitz. And it behaves like a bank that understands campaigns don’t run on banker hours. The pitch is simple: wire windows that stay open later, responsiveness when it matters, and white-glove support that feels like a concierge, not a hotline. Campaigns need speed, certainty, and compliance fluency. Amalgamated sells all three.

That work shows up in the balance sheet, too—because campaign money doesn’t sit still. Political deposits swell when fundraising is high and spending is low, and then drain as the race heats up and ad buys start flying. At one point, about 21% of Amalgamated’s total deposits—roughly $1.8 billion—was tied to political campaigns. But that share can fall into the low teens as campaigns ramp spending. On a second-quarter earnings call in July, Brown described the model as expecting political deposits to trough around $700 million at year-end, “modestly above the 2022 trough.”

The volatility is big, but it’s not mysterious. The bank even spells it out in its disclosures: deposits held by politically active customers—campaigns, PACs, advocacy organizations, and party committees—were $1.0 billion as of December 31, 2024, down by $992.3 million during that quarter.

Importantly, this political franchise doesn’t stand alone. Amalgamated’s client list includes major labor and progressive institutions: AFSCME, the International Association of Firefighters, SEIU, the United Federation of Teachers, the Democratic Governors Association, the Economic Policy Institute, the League of Conservation Voters, Organizing for Action, and Public Citizen. The connective tissue is trust—built over decades—and a bank that looks, sounds, and acts like it’s on the same team.

And then there’s the other pillar of the moat: labor’s long-term money.

Beyond campaign deposits, Amalgamated built a leading position in Taft-Hartley pension plan administration. Through its Institutional Asset Management and Custody Division, the bank is one of the leading providers of investment and trust services to Taft–Hartley plans in the United States, overseeing more than $45 billion in investment advisory and custodial services.

Formed in 1973, Amalgamated’s Investment Management Division ultimately came to serve more Taft-Hartley pension plans than any other U.S. money manager. The selling point isn’t just returns; it’s fluency. Trustees of large pension and health-and-welfare funds operate under unique governance and fiduciary constraints, and Amalgamated built a business around understanding those constraints. Its LongView Funds also became known for corporate governance initiatives and aggressive shareholder activism—another way the bank turned “values” into a differentiated offering rather than a slogan.

Put those pieces together and you get powerful cross-selling dynamics. A union relationship can lead to managing the pension plan. A pension plan relationship can lead to treasury services. A campaign account can introduce the bank to a broader ecosystem of committees, consultants, and advocacy groups. Each connection reinforces the others, and the whole network becomes harder to displace.

Not every growth move worked, though—even when the logic was almost storybook-perfect.

Amalgamated Financial Corp. (Nasdaq: AMAL), the holding company for Amalgamated Bank, announced that it withdrew its application for regulatory approval to acquire Amalgamated Bank of Chicago after being unable to obtain approval. That ended the transaction.

The irony was thick: Amalgamated Bank of Chicago had been founded in 1922 by the same union— the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America—that started the New York bank. The deal would have reunited two institutions with shared roots and a similar mission orientation. Instead, it became a reminder of a basic truth in banking: you don’t do M&A because it makes sense on paper. You do it only if regulators let you.

All of this raises a risk that’s obvious the moment you say it out loud: concentration. If you’re “the Democratic bank” and a major player in green energy, you may invite extra scrutiny in a polarized era. One observer put it bluntly at the time: even if Amalgamated is “very well-managed and profitable,” it could see parts of its business pressured and regulatory scrutiny ramp up—and, in the wrong political climate, “become a target.”

Management’s response has been pragmatic. Brown’s message was essentially: judge us like a bank. “Those solid returns and strong profitability is really our best answer to what you're hearing,” she said, adding that the company did not expect “any material risk” to the business model or customer base, because “we are a bank first and foremost.”

The bet Amalgamated is making is that this niche—politics as an industry, labor as an ecosystem—doesn’t just create volatility. Done right, it creates a moat.

VIII. Strategic Acquisitions & Geographic Expansion

Amalgamated’s growth plan has stayed intentionally narrow: expand into the places where progressive institutions actually live, and avoid the temptation to become a generic, branch-heavy retail bank.

That’s why the New Resource Bank deal mattered. On May 18, 2018, Amalgamated completed its acquisition of New Resource Bank, giving it a real foothold in the San Francisco metro area, including a branch. The bank’s view was straightforward: this wasn’t expansion for expansion’s sake. It was an entry into a market dense with exactly the kinds of customers Amalgamated was built to serve—mission-aligned businesses, nonprofits, and values-driven institutions.

At the time, New Resource brought a meaningful base of assets, loans, and deposits. Under the merger agreement, each share of New Resource common stock converted into the right to receive 0.0315 shares of Amalgamated’s Class A common stock. Total consideration was about $58.8 million, largely paid in Amalgamated Class A shares, and Amalgamated recorded $12.9 million of goodwill tied to the acquisition.

But the bigger contribution wasn’t just financial. New Resource also brought specialized credibility in climate-focused lending. New Resource Bank had a very different origin story: founded in 2006, it was built around a specific idea—move money toward clean, renewable energy—while also supporting sustainable agriculture, nonprofits, and B Corps.

Zoom out, and you can see the map the bank is drawing. Amalgamated is headquartered in New York City, and it operates five branches: three in New York City, one in Washington, D.C., and one in San Francisco.

That modest footprint isn’t a limitation. It’s a choice. Amalgamated does have a consumer banking operation, but its historical cost reportedly exceeded the value of the funding it produced—one reason Keith Mestrich closed 12 branches in the New York area.

Instead of fighting for retail convenience, Amalgamated puts its weight behind commercial and institutional relationships where mission alignment creates real staying power. It uses loan production offices in strategic locations—supporting commercial real estate and climate lending—without taking on the overhead of building a traditional branch network.

Today, Amalgamated is a New York-based full-service commercial bank and chartered trust company, with five branches across New York City, Washington, D.C., and San Francisco, plus a commercial office in Boston. And for all the reinvention, the throughline is still intact: it began in 1923 as Amalgamated Bank of New York, founded by the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, one of the country’s oldest labor unions.

IX. The Modern Business Model: How Mission Becomes Moat

Amalgamated runs the business through four interconnected pillars: labor and impact organizations, political and advocacy groups, commercial lending, and trust and investment services. The key is that these aren’t separate lines on an org chart. They feed each other. A union relationship can lead to managing a pension plan. A campaign account can introduce a whole constellation of committees and advocacy groups. And those relationships, in turn, drive deposits that power the lending book.

Under CEO Priscilla Sims Brown, the bank has leaned hard into values-based banking as an operating system, not a tagline—pairing customer service with a deliberate lending strategy aimed at social and environmental outcomes. The customer set reflects that: climate organizations, foundations, labor unions, advocacy groups, political campaigns, and socially responsible businesses that care less about squeezing out a few extra basis points and more about what their deposits enable.

That shows up most clearly in what the bank chooses to finance. More than 60% of the bank’s lending and select balance sheet investments are classified as high-impact, flowing to affordable housing, nonprofits, and climate solutions.

The mission doesn’t just shape the portfolio. It shapes the funding. Amalgamated has an unusual deposit advantage for a bank of its size: in one quarter, non-interest-bearing deposits made up 44% of average total deposits and 40% of ending total deposits, contributing to an average total deposit cost of 153 basis points. When a large share of your funding pays no interest at all, it gives you room to lend, invest, and compete without playing the same rate game as everyone else.

And the reason customers accept that trade-off is the simplest one: alignment. Many of Amalgamated’s depositors aren’t shopping for the top yield. They’re picking a bank that matches their identity and priorities. That creates a cost-of-funds advantage that’s hard for a purely rate-driven competitor to replicate.

Management even has a name for the stickiest part of this base. “Super-core” deposits totaled about $3.8 billion, had a weighted average life of 18 years, and represented 54% of total deposits. In other words: long-duration, mission-aligned funding that behaves less like hot money and more like infrastructure—quietly supporting everything else the bank wants to do.

One place that funding has gone, increasingly, is climate lending. Amalgamated has positioned climate-related financing as a major growth engine, including a capital commitment of up to $250 million to fund commercial real estate projects originated through FASTPACE.com, Allectrify’s tech-enabled C-PACE lending platform. The idea is to expand access to long-term, flexible C-PACE financing nationwide, especially for underserved middle-market projects—often in the range of $250,000 to $10 million.

That focus isn’t limited to one initiative. After opening its downtown Boston commercial banking office in 2020, Amalgamated has said it invests nearly 40% of its total lending portfolio in climate protection solutions—financing aimed at decarbonization and renewable energy. The bank has also highlighted that it holds more than $1.2 billion in PACE assets in its investment portfolio, positioning itself as a leader in that category.

Importantly, Amalgamated tries to make the inside of the institution match what it sells to the outside. In 2015, it announced it would become the first bank in the nation to raise all employee wages to a minimum of $15 per hour. And it has pointed to a CEO-to-worker pay ratio of 17:1—standing out in an industry where that ratio can run into the hundreds-to-one.

The financials, at least recently, suggest the model can work as a business, not just a statement. Amalgamated Financial reported strong 2024 results, with net income of $106.4 million, up 20.9% year over year, alongside net interest margin expansion to 3.59% amid loan growth and a strengthened capital position. For the full year, it reported revenue of $304.26 million, up from $274.58 million the year prior, and earnings of $106.43 million, also up about 21%.

X. Competitive Positioning & Market Dynamics

Amalgamated sits in a corner of American banking that’s hard to even benchmark. There are other mission-driven institutions—Beneficial State in California, Sunrise Banks in Minnesota—but none stacks the same combination: union roots and ownership, a public listing, a public benefit corporation structure, and a political banking franchise that’s become the default for much of the Democratic ecosystem.

It also means the competitive set depends on what, exactly, you’re talking about. In day-to-day commercial banking, Amalgamated still competes with giants like JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and PNC. But in its true specialty lanes—values-driven deposits, advocacy organizations, labor institutions, and campaign banking—the real competition isn’t another product feature. It’s trust. And trust is something you can’t buy quickly.

That’s why “why can’t JPMorgan just copy this?” is the wrong question. Of course a megabank can launch an ESG-branded product suite. What it can’t replicate is the credibility that comes from being willing to take a values-based stand and keep it, even when there’s blowback.

After a high-profile mass shooting, three banks—including Amalgamated—said they would do everything in their power not to do business with certain types of gun dealers. Bank of America and Citibank ultimately tempered their commitments. Amalgamated didn’t. That’s the model in its purest form: values-aligned banking isn’t what you say in a press release. It’s what you’re still willing to do when it costs you something.

Keith Mestrich put it bluntly: “Amalgamated’s customer base is aligned on a set of social principles. It’s okay to lose customers who don’t share those convictions.” A large bank serving everyone can’t make that trade-off—not consistently, and not without setting off internal and external backlash. Amalgamated can, because that’s the point.

Then, in 2021, the bank entered its next chapter. Amalgamated named Priscilla Sims Brown as President and CEO, with a start date of June 1, 2021. She came from Commonwealth Bank of Australia, where she served as Group Executive, Marketing and Corporate Affairs—running marketing and branding, stakeholder insights, government and public affairs, and the bank’s environment and social policy work. Across more than 30 years in financial services, she’d held leadership roles spanning banking, wealth management, retirement, and insurance.

Her arrival also underscored something about who Amalgamated is trying to be internally, not just externally. Brown’s appointment made Amalgamated one of the only banks in the country whose CEO and board chair—Lynne Fox—were both women. And women or people of color made up 60% of its workforce.

Strategically, Brown brought exactly what the bank wanted for the next phase: someone who understood that a differentiated bank has to tell its story as clearly as it runs its balance sheet. “I think Amalgamated is an unfortunately well-kept secret,” she said. “I hope my background will help us tell its story louder and prouder.”

XI. Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Starting a bank is hard. Starting a bank that’s union-owned, mission-driven, and trusted inside progressive and labor circles is harder. Regulation alone makes “move fast and break things” impossible here, and the real barrier isn’t just capital or a charter—it’s credibility. Amalgamated’s relationships were built over a century. You can’t spin that up in a funding round.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW-MEDIUM

In banking, deposits are the raw material. Amalgamated’s advantage is that its depositors often behave less like rate shoppers and more like long-term partners, which keeps funding relatively cheap and sticky. Labor is another input: a unionized workforce can add cost pressure, but it’s also part of the brand promise the bank sells. And on technology, Amalgamated relies on many of the same vendors as other banks—important, but not uniquely powerful in negotiations.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM

Some customers are big enough to negotiate: large unions, national campaigns, major advocacy groups. But walking away isn’t frictionless. Once a campaign builds its compliance processes and operating rhythm around a bank that understands the “industry of politics,” switching gets painful. On the consumer side, the dynamic flips: many retail customers aren’t optimizing for the last incremental yield. They’re paying for alignment.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM

Credit unions can cover basic consumer banking. Big banks can market ESG programs, but they often struggle to make them feel authentic or consistent. Fintechs can beat everyone on a narrow feature—payments, onboarding, a slick app—but they don’t replicate the full stack Amalgamated provides, especially the operational and compliance-heavy needs of political organizations. There are alternatives, but none that are truly the same product.

Competitive Rivalry: LOW-MEDIUM

In the specific lane Amalgamated cares most about—progressive institutional banking—the field is surprisingly thin. For certain commercial deals, it still runs into regional and national banks. But in its core markets, competition isn’t a rate war. It’s a trust contest. And Amalgamated’s edge is that it’s not trying to win by looking like every other bank. It’s trying to win by being unmistakably itself.

XII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Counter-Positioning: VERY STRONG ★★★

This is Amalgamated’s superpower. The biggest banks can’t take Amalgamated’s stance without blowing up their own business models. JPMorgan can’t credibly become “the bank of the Democratic Party” without risking relationships on the other side of the aisle. In a polarized America, that constraint becomes Amalgamated’s advantage: the more charged the environment gets, the harder it is for a universal bank to imitate them. Counter-positioning is durable precisely because competitors can’t follow without paying a price they’re structurally unwilling to pay.

Branding: VERY STRONG ★★★

Amalgamated has always been a different kind of bank. Founded in 1923 by the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America—an immigrant-heavy textile and garment union in New York City—it was built to serve working people in an era when banking largely served corporations and the wealthy. Over time, the bank became known for offering products and access that mainstream institutions often didn’t prioritize for everyday customers: free savings and checking, unsecured credit, affordable housing loans, and “second chance” accounts for people who’d struggled with credit in the past.

That history is the brand. A century of lived mission is not something a competitor can replicate with a campaign, a rebrand, or an ESG microsite. To the customers Amalgamated is built for, the bank’s name signals alignment—and that signal has real economic value.

Cornered Resource: STRONG ★★★

Workers United’s ownership isn’t just a cap table detail; it’s an advantage competitors can’t buy. Decades of relationships across labor and progressive organizations create privileged access to customer networks. And Amalgamated’s political banking capability—campaign-finance fluency, compliance infrastructure, and a service model that assumes urgency—was built over years of doing the work, cycle after cycle.

Switching Costs: MEDIUM-STRONG

For retail customers, switching costs are real but manageable. For political campaigns, switching can be painful: you’re not just moving accounts, you’re rebuilding compliance routines, reporting workflows, and operational muscle memory mid-race. And for Taft-Hartley pension plans, switching costs are even higher—multi-year relationships, complex custody and administration, and a level of institutional trust that doesn’t transfer overnight.

Network Effects: MODERATE

There’s a real clustering effect: when Democratic campaigns, unions, and advocacy groups bank in the same place, it creates signaling value and drives referrals inside tight networks. But it isn’t a classic network effect like a payments network, where every new user directly increases utility for every other user. The value is social and reputational, not exponential.

Scale Economies: WEAK

Amalgamated has intentionally stayed at community-bank scale. There are some economies in trust, custody, and institutional servicing, but the bank isn’t trying to win through sheer size or the lowest possible unit costs. In this strategy, staying smaller is a feature: it supports focus, specialization, and mission credibility.

Process Power: MEDIUM

Amalgamated has accumulated expertise in campaign finance, union pension management, and the operational quirks of political and advocacy organizations. That know-how is valuable, and it takes time to build. Still, a determined competitor could learn parts of it—especially if they were willing to commit resources for long enough.

Durability Assessment:

Counter-positioning, Branding, and Cornered Resource are the core of Amalgamated’s durable advantage, and they should hold as long as political polarization continues to make “serving everyone” incompatible with “standing for something.” The biggest vulnerability is concentration: if progressive coalitions splinter, or the political winds shift hard enough, what looks like a moat can start to look like exposure.

XIII. Bull Case vs. Bear Case

Bull Case:

The moat is real—and it may be getting deeper. Amalgamated’s counter-positioning isn’t a clever slogan; it’s a structural advantage. The biggest banks can’t credibly chase progressive institutional customers without triggering conflicts across the rest of their client bases. As more organizations look for values-aligned financial partners, that dynamic expands Amalgamated’s natural market.

Climate lending is the other long runway. The bank has positioned itself as a leader in sustainable finance, pushing deeper into PACE and broadening access across different project sizes. With the energy transition demanding enormous amounts of financing over decades, Amalgamated is set up to be a meaningful player in an asset class that keeps getting bigger.

Then there’s the funding engine. A large share of deposits has historically been non-interest-bearing, keeping the overall cost of deposits low and giving Amalgamated room to protect margins even when competitors have to pay up. In banking, cheap and sticky funding is an unfair advantage—especially when it comes from customers choosing you for alignment, not just rate.

Finally, the trust and custody business offers a different kind of growth: scalable, fee-driven, and less dependent on putting more risk on the balance sheet. If you believe those dynamics compound over time, you can also argue the market may be underpricing what this model can produce.

Bear Case:

The biggest risk is concentration—especially political concentration. Amalgamated is widely seen as the bank of the Democratic Party, with longstanding ties to labor unions and a history of handling deposits for major political figures and campaigns, including former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and former Vice President Kamala Harris. In a polarized country, that visibility can cut both ways: it attracts the right customers, but it can also invite scrutiny at exactly the wrong time.

There’s also the size question. Staying at community-bank scale helps the brand and focus, but it can limit the ability to spend aggressively on technology and compete with much larger institutions on digital experience, products, and operational leverage.

Regulatory and governance risks layer on top. In a hostile political environment, scrutiny could rise. And the PBC structure, while a mission shield, could also frustrate shareholders if it’s perceived to constrain profit-maximizing decisions.

Geography is another limiter. The footprint—New York City, Washington, D.C., San Francisco, and Boston—maps well to the customer base, but it also means less diversification if those markets or sectors cool.

And hovering over all of it is the existential tension that never fully goes away: can you truly serve shareholders and society at the same time, year after year, under public-market pressure—or does something eventually give?

Key Metrics to Watch:

If you want to track whether the thesis is working, two measures matter most:

-

Political deposit retention through election cycles: Campaign money is inherently volatile, but the question is whether the relationships persist cycle to cycle—even as balances drain during peak spending.

-

Climate lending growth rate: C-PACE and renewable energy lending are central to the bank’s growth narrative; steady expansion is the clearest signal that the strategy is translating into durable business momentum.

XIV. Epilogue: The Experiment Continues

By December 31, 2024, Amalgamated had grown into an $8.3 billion institution, with $4.6 billion in net loans and $7.2 billion in deposits. Its trust business—quietly one of the most important engines in the whole story—reported $35.0 billion in assets under custody and $14.6 billion under management.

A century after Sidney Hillman opened those doors near Union Square, the bank is still doing what it was designed to do: serve movements, not just manage money.

That doesn’t mean the grand experiment is “proven.” The central tension—whether stakeholder capitalism can hold up under public-market gravity—still sits at the core of the company. But every quarter the bank stays profitable while keeping the mission intact adds another layer of evidence that this isn’t just branding.

The business, at least over the most recent year, reflected that momentum: total revenue rose by about 14% year over year, and net income climbed by about 21%. Earnings per share rose by about 20% as well.

What happens next depends on questions that no single earnings report can answer. Will other banks follow the public benefit corporation path, or will Amalgamated remain an outlier? Can mission-driven banking scale without losing the thing that makes it trustworthy? And does political polarization keep strengthening the moat—or does it eventually turn into the risk that swallows the strategy?

For founders and investors watching from the sidelines, a few lessons are hard to miss.

Sometimes the most durable advantage is simply being willing to serve a market others won’t touch. While larger banks hesitated, diluted commitments, or treated values as a seasonal marketing theme, Amalgamated kept showing up—and that consistency became its product.

Authentic positioning compounds. A century of union roots can’t be manufactured in a conference room, and relationships built in moments of urgency don’t unwind just because a competitor offers a slightly better rate.

And the final “irony” isn’t really irony at all: that a 100-year-old labor bank could be more innovative than most Silicon Valley fintechs. Innovation isn’t only new technology. Sometimes it’s the willingness to build a business model that everyone else insists can’t work.

XV. Sources for Further Reading

If you want to go deeper—into the history, the filings, and the frameworks behind how a union-owned bank ended up as a publicly traded public benefit corporation—here are the best places to start:

-

Amalgamated Bank's Corporate Social Responsibility Reports - Available on the bank’s investor relations site. These annual reports lay out the ESG priorities, the commitments the bank makes publicly, and the progress it reports against them.

-

SEC/FDIC Filings - The 2018 IPO prospectus is the cleanest single document for understanding the modern company, and subsequent filings add the ongoing details: risk factors, business lines, financial performance, and the mechanics of being public.

-

B Lab's Assessment of Amalgamated - The B Corp certification materials show how Amalgamated scored on B Lab’s impact framework, and what it took to land at more than triple the median business score.

-

"Labor Will Rule: Sidney Hillman and the Rise of American Labor" by Steven Fraser - The essential biography for understanding Sidney Hillman, the ACWA, and the worldview that ultimately became Amalgamated’s founding logic.

-

Kheel Center at Cornell University - The ILR School’s labor archives include deep primary-source material on the Amalgamated Clothing Workers and the broader labor ecosystem the bank grew out of.

-

Public Benefit Corporation legal literature - Academic and legal coverage in places like the Delaware Law Review and Stanford Social Innovation Review helps explain what PBC status actually changes—and what it doesn’t.

-

Campaign finance databases - Federal Election Commission filings are the ground truth for seeing how political committees bank, how those relationships cluster, and how Amalgamated fits into the machinery of modern campaigns.

-

Global Alliance for Banking on Values materials - Useful context on the wider values-based banking movement, and where Amalgamated sits within that global peer set.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music