ADTRAN Holdings Inc.: From Alabama Garage to Global Fiber Networks

I. Introduction: The Telecom Company Hiding in Plain Sight

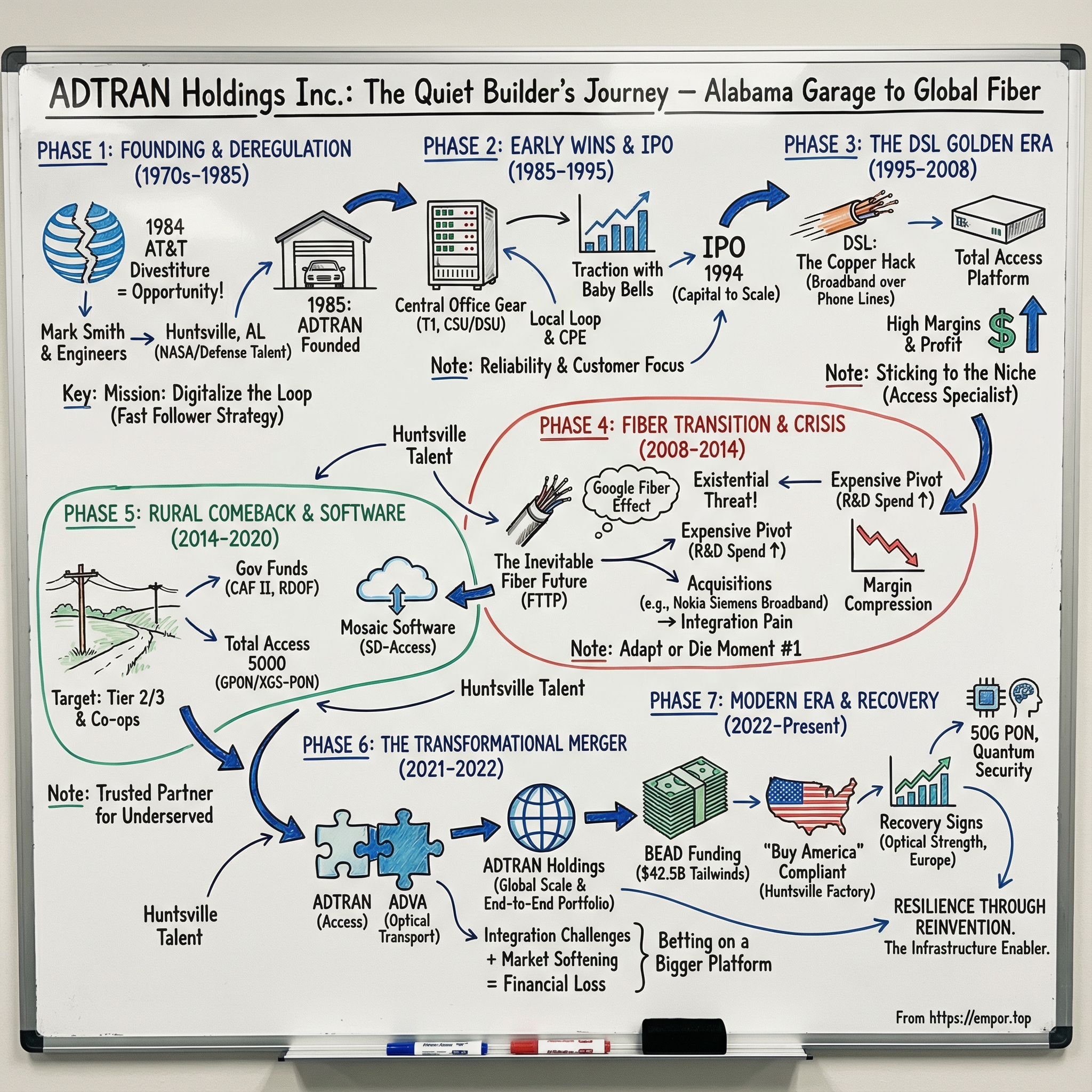

In the summer of 2022, a merger closed that barely registered outside telecom circles. A company headquartered in Huntsville, Alabama—better known for rocket scientists, missile defense, and NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center—combined with a German optical networking firm in a deal worth nearly €800 million. Overnight, the new entity, ADTRAN Holdings, stretched across continents: more than 3,000 employees, and close to a billion dollars a year in revenue.

And yet, to most investors, ADTRAN might as well not exist.

That’s the paradox. For four decades, ADTRAN has been one of the quiet builders of modern connectivity: the kind of company that helps a rural telephone cooperative light up gigabit service, or gives a small-town provider the gear to replace aging copper lines with fiber. It doesn’t dominate consumer headlines. It enables them. ADTRAN doesn’t sell the apps you use. It sells the infrastructure that makes using them possible.

ADTRAN was founded in 1985 by Mark C. Smith. Over the years it built a business around communications platforms—hardware, software, and services—that move voice, data, video, and internet traffic through broadband access and optical networking systems. Today the company positions itself around open, disaggregated networking, serves everyone from service providers to government agencies, and holds more than 1,000 technology patents.

So here’s the question that makes this story worth telling: how did a handful of Alabama engineers, starting out at the dawn of telecom deregulation, build a company sturdy enough to fight on a global stage against names like Nokia, Cisco, and Calix? And what does that journey teach us about surviving technology transitions—where moats are thin, cycles are brutal, and the winners are often the ones who pivot at exactly the right moment?

Because ADTRAN’s timeline is basically the timeline of American telecom: the breakup of AT&T, the dial-up era, the DSL boom, the painful shift to fiber, and then the newest chapter—government-backed urgency to close the digital divide. Fiber networks are seeing historic levels of investment, and the pandemic made one thing impossible to ignore: in many rural areas, broadband access still wasn’t there, because the economics of deployment are so unforgiving. That realization helped push state and federal lawmakers toward unprecedented funding to offset the cost of building into the hardest-to-serve places.

Through every era, ADTRAN kept running into the same existential choice: adapt or die. Sometimes it got the call exactly right. Sometimes it got there late. It rode DSL to real success, nearly got swept away by the fiber transition, and then bet its future on a transformational deal. In July 2022, ADTRAN Holdings announced it had closed its business combination with ADVA Optical Networking SE. Whether that gamble ultimately pays off is still being decided—but after a rough stretch, the early returns have started to show signs of life.

So let’s start where this kind of story always starts: with a regulatory earthquake that cracked open an industry—and created room for outsiders to build.

II. Founding Context: Deregulation & The Birth of Telecom Innovation (1970s–1985)

To understand where ADTRAN came from, you have to understand the industry it was born into. For most of the twentieth century, American telecommunications effectively meant one thing: AT&T. The Bell System operated as a regulated monopoly, controlling the network, the standards, and the hardware. If you made a phone call in America, odds were you were doing it on Ma Bell’s lines, with Ma Bell’s equipment, on Ma Bell’s terms.

Then the ground shifted.

The hinge point was the 1984 AT&T divestiture. The consent decree—effective January 1, 1984—didn’t just split one company into eight. It rewired the incentives of the entire industry. The seven newly formed Regional Bell Operating Companies, the “Baby Bells,” could no longer lean on Western Electric, AT&T’s in-house manufacturing arm. They suddenly had to buy from third-party equipment suppliers.

And that created a once-in-a-generation opening for outsiders.

Mark C. Smith had been preparing for this kind of moment for a long time. He wasn’t a first-time founder or a starry-eyed engineer with a napkin sketch. He had already built a business once—starting with his own money and a garage. After working at SCI Systems, Inc., and earning an electrical engineering degree from Georgia Tech in 1962, Smith rose into management. Then in 1969, he left to co-found Universal Data Systems (UDS) with $30,000 in savings. UDS became the first data communications company in Alabama, grew into a meaningful business, and by 1979—at roughly $20 million in annual revenue—was acquired by Motorola.

Post-acquisition, Smith became president of the DDS-Motorola Division. But by 1985, he was ready to go again. He left Motorola and co-founded ADTRAN, Inc., later serving as CEO and chairman. The idea wasn’t to build another modem company. It was to build the kind of digital transmission gear the post-divestiture phone companies were now required to source in the open market.

ADTRAN was founded in 1985 in Huntsville, Alabama, by Smith along with John Jurenko, Lonnie McMillian, and four other engineers. The mission: help modernize—digitalize—telecom infrastructure at the exact moment the industry was being forced to change. Even the name telegraphed the ambition: ADTRAN, short for “advanced transmission.”

Huntsville wasn’t a random dot on the map, either. It was an engineering town hiding in plain sight. The company set up in Cummings Research Park, next to the U.S. Army’s Redstone Arsenal and a dense web of federal agencies and contractors—NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, the Missile Defense Agency, and many more. Huntsville was swimming in technical talent, especially the kind of systems-minded engineers you get from aerospace and defense work. When Smith needed people who could build reliable, carrier-grade digital equipment, the local labor market could supply them.

Smith saw the divestiture for what it was: not just a legal event, but a demand shock. The Baby Bells and independent telcos still had millions of miles of copper wire in the ground, and they needed ways to squeeze more performance out of it—faster, cleaner, more digital. As Smith later told Investor’s Business Daily, “We founded this company to take advantage of the trend toward complete digital systems ... the technology of the future.”

ADTRAN began operations in January 1986, and the early traction came fast. By that year, the company had secured contracts to supply high-speed digital transmission equipment for central offices and local loops to all seven RBOCs, plus more than 1,300 independent U.S. telephone companies. For a brand-new company, that kind of customer list wasn’t just impressive—it was a signal that the market was starving for credible alternatives.

Within roughly a year of starting up, ADTRAN had won contracts with every Baby Bell. That wasn’t luck. It was strategy: build equipment that was less expensive than the old AT&T-era pricing, more flexible than the legacy systems carriers had inherited, and designed by engineers who would actually incorporate customer feedback.

There’s a broader lesson in that origin story. Some of the biggest opportunities don’t come from a breakthrough technology at all—they come from a rule change that forces an industry to unbundle. The AT&T breakup did for telecom equipment what airline deregulation did for aviation: it turned a closed world into an open market. Smith and his co-founders had the experience, the timing, and the Huntsville talent base to step through the opening.

III. The Early Years: T1 Multiplexers & Finding Product-Market Fit (1985–1995)

Picture a telephone company’s central office in 1986. Rows of equipment racks. Blinking LEDs. Fans whining as they push heat out of metal boxes stacked like drawers. Somewhere in that maze, a technician is trying to hook up a business customer—maybe a bank branch or a factory—to the broader phone network.

The customer wants something simple: multiple voice channels at once. Not one phone call at a time, but a whole bundle—up to 24 simultaneous calls—delivered reliably over the existing copper infrastructure. That’s what a T1 line did. And the workhorse device that made it usable, stable, and compatible with the network was the CSU/DSU, short for Channel Service Unit/Data Service Unit.

This was ADTRAN’s first arena: unglamorous, mission-critical gear that sat in central offices and on customer premises, managing the digital signals that let businesses talk, transmit, and operate. In practice, that meant building digital transmission equipment for two parts of the phone network that mattered most: the “Central Office,” where local switching and distribution happened, and the “Local Loop,” the last stretch of network connecting the central office to the customer.

The company moved fast. By 1991, ADTRAN had already captured leading market share in its target niche—central office and local loop equipment sold to U.S. telcos. Mark Smith doubled down with a straightforward playbook: keep pushing out new products, obsess over customer service, and make the hardware excellent. Telcos rewarded reliability. They also rewarded vendors who picked up the phone and fixed problems without drama.

But Smith wasn’t blind to the risk. Even with strong traction, ADTRAN was exposed to the capricious nature of carrier spending. So the company started looking downstream, beyond the central office, toward a second customer: the corporate end-user at the edge of the local loop. That market was called customer premises equipment, or CPE—and it offered a way to diversify demand without abandoning ADTRAN’s core strengths.

A big part of what made ADTRAN competitive in those years was how it approached engineering. Smith pushed teams to design products with the next redesign in mind. The goal wasn’t to create one perfect box and ship it forever. It was to build something solid, then be ready to upgrade it quickly and cheaply when standards shifted or competitors forced a reset. That discipline shortened ADTRAN’s new-product life cycle to about 18 months—an eternity in software, but extremely fast in carrier-grade hardware.

Early products leaned on the same DDS technology that had been central to AT&T’s digital data services. But by 1989, ADTRAN was already building for what came next, developing equipment for emerging protocols like ISDN and HDSL. ISDN—Integrated Services Digital Network—was pitched as a leap forward: it used ordinary copper phone lines to carry digital services like text, video, audio, or fax data at up to 128,000 bits per second, while still allowing a normal phone conversation on the same line.

Underneath all of this was ADTRAN’s core innovation model: fast follower execution. The company wasn’t trying to invent new protocols from scratch. It was taking established standards and building equipment that was cheaper, more reliable, and better tuned to what telcos actually needed. That required deep relationships with purchasing managers and network engineers—and a ruthless focus on cost and manufacturability.

Then came a defining milestone: ADTRAN’s IPO on August 9, 1994.

Going public gave ADTRAN the resources—and the credibility—to scale at exactly the moment the market was about to change again. The early years had been about digitizing the phone network. The next era would be about feeding a new kind of demand: data, internet traffic, and the growing expectation that copper lines should do more than carry voice.

By the time it hit the public markets, ADTRAN had already built a track record: it focused early on central office and local loop equipment, expanded into HDSL, and launched its first ISDN Service Unit product family by 1993. The IPO didn’t change the company’s DNA. It amplified it. ADTRAN had proven that a relatively small, Huntsville-based engineering shop could compete with far larger manufacturers by staying close to customers and executing relentlessly on product quality.

And for investors who bought into Smith’s vision, the payoff wouldn’t be immediate—but it would be real. Over the following years, ADTRAN’s stock would climb to an all-time end-of-day high of $36.38 on March 3, 2011.

IV. The DSL Revolution: ADTRAN's Golden Era (1995–2008)

The late 1990s handed every telecom equipment company the same, make-or-break problem: the “last mile.”

The internet was taking off. Long-haul fiber routes between cities could carry oceans of data. But the final connection into homes and offices—the part customers actually experienced—still ran over old copper telephone wires. For most people, “going online” meant a dial-up modem and a connection that crawled.

DSL changed that. Digital Subscriber Line wasn’t one single invention so much as a family of techniques that squeezed far more data through copper by using frequencies above the voice band. All of a sudden, the same pair of wires that carried a phone call could also deliver broadband—fast enough to feel like the future. And because cable companies were starting to sell high-speed internet over coax, phone companies had no choice but to respond. They rushed to roll out DSL, and they needed vendors who could ship reliable gear at scale.

This was exactly the kind of transition ADTRAN had been building toward. The company had already been supplying HDSL equipment, and because it started manufacturing and selling those solutions earlier than many competitors, it entered the DSL era with a head start: hard-earned experience in pushing high-speed services over existing copper. As businesses began leaning on the internet for everything from email to early e-commerce, ADTRAN had the know-how to deliver market-leading products for high-speed T1 services without requiring carriers to rebuild their networks from scratch.

The company’s Total Access line became a workhorse of the broadband buildout. Telcos needed systems that could take thousands of copper lines coming into a central office and turn them into broadband service out to customers. That’s the job of DSL access equipment, including DSLAMs, and ADTRAN became a trusted supplier alongside larger players. Major carriers like BellSouth, Verizon, and AT&T were racing to upgrade their copper footprints. ADTRAN gave them a combination they valued: dependable performance, practical deployment, and a cost profile that made the math work.

By this point, ADTRAN wasn’t just a clever upstart with a few successful boxes. It had become a scaled supplier to U.S. telecom operators, with a broader portfolio that included customer premises equipment—gear that sat at the edge of the network in businesses and homes. That mix mattered. It meant ADTRAN could serve carriers not only in the central office, but also in the messy, high-volume reality of installations at the customer end.

The results looked different than the typical telecom equipment story. This industry is famous for booms, busts, and flameouts. Nortel and Lucent grabbed headlines with massive scale and aggressive deal-making. ADTRAN built a quieter reputation: steady profitability, healthy margins, and execution that made operators comfortable betting their networks on a company from Huntsville.

In the mid-2000s, those margins were especially strong—extraordinary for a hardware business. Part of that came from the product mix. High-margin T1 products made up a big portion of revenue, helping push gross margins to levels that were the envy of the sector. Over time, as the industry shifted and mix changed, margins trended down—one more reminder that in networking, yesterday’s cash cow rarely stays a cash cow forever.

Underneath the numbers was a culture that fit the moment. ADTRAN was engineering-led in a way that wasn’t performative. The company’s center of gravity was technical excellence, not big-brand marketing. Huntsville reinforced that instinct. When you’re surrounded by NASA engineers and defense contractors, you learn to care about reliability, systems thinking, and getting the details right—exactly what carriers demand from equipment that can’t fail.

This era also marked a leadership handoff. Thomas R. Stanton joined ADTRAN in 1995 as vice president of marketing for the Carrier Networks Division and moved through a series of senior roles, including senior vice president and general manager of that division. In September 2005, he was named CEO, and in 2007 he became chairman of the board. The transition happened near the high-water mark of DSL—when ADTRAN’s strategy of staying focused on broadband access, instead of trying to be everything to everyone, looked like a blueprint for how to win as a specialist.

But technology never lets you keep your victories for long. Even as DSL reached its peak, the next wave was already forming—and it wasn’t going to be friendly to a company built on making copper do more than it was ever meant to do.

V. Inflection Point #1: The Fiber Transition & Strategic Crossroads (2008–2014)

The uncomfortable truth about DSL was that it was always a brilliant hack.

It took century-old copper and, through clever signal processing, made it feel like broadband. But it was still a workaround. And by the mid-2000s, the industry was starting to admit what it had been trying not to say out loud: the real endgame was fiber.

In 2004, three of America’s largest phone companies—BellSouth, SBC Communications, and Verizon—aligned on a common set of technical requirements for fiber-to-the-premises, or FTTP. Translation: this wasn’t just a lab project anymore. This was the start of a standard, industrial-scale path toward running fiber all the way to homes and businesses—unlocking bandwidth that copper simply couldn’t match, and enabling not just faster internet, but new voice and video services too.

For ADTRAN, that was an existential signal.

The company’s entire identity had been built around making copper networks better: cheaper boxes, smarter architectures, and incremental upgrades that let carriers delay the painful, capital-heavy move to something new. But if the telcos were now committing to rip-and-replace—swapping copper for fiber in the last mile—then a huge portion of ADTRAN’s product portfolio was staring at an expiration date.

At the same time, competitive pressure wasn’t easing. Cable operators had a relatively straightforward upgrade story: with DOCSIS, they could keep using their existing coaxial plant and still push toward gigabit-class broadband. Telcos didn’t have that luxury. Their upgrade path was steeper, slower, and more expensive—often requiring new fiber construction. The only way to make that math work, especially outside dense metro areas, was to find ways to share risk and cost, sometimes partnering with communities, while creating higher revenue potential through improved service and new offerings.

Then, in 2010, Google poured gasoline on the conversation.

When Google announced its “Think Big with a Gig” initiative, it didn’t just introduce a new product. It introduced a new threat. Google Fiber showed that there was room to rethink broadband pricing and packaging—and, more importantly, that a deep-pocketed entrant could embarrass incumbents on speed and customer experience. Even where Google never built, the mere possibility of competition pushed operators to improve their broadband offerings.

This was the innovator’s dilemma, telecom edition.

ADTRAN’s DSL products were still throwing off real revenue and real profit. But the future was clearly bending toward fiber. So what do you do? Milk the copper business while it lasts and risk getting leapfrogged? Or invest aggressively in fiber—cannibalizing your own franchise before someone else does?

Historically, ADTRAN won by doing something almost counterintuitive: it stepped a pace behind the bleeding edge, took mature technology, and built a better “mousetrap.” Cleaner designs. Fewer unnecessary features. Lots of room to drive costs down. That approach worked especially well when bigger vendors were distracted chasing the next big thing.

But starting around the middle of 2009, management began a gradual shift in posture—from being a humble supplier that could often stay out of the industry’s heaviest knife fights, to positioning ADTRAN as a leading provider of next-generation networking solutions. That move put the company in more direct competition with larger players, and it showed up in the results.

The transition was expensive. Gross margins compressed as investment ramped. The stock struggled. Analysts openly questioned whether ADTRAN had the scale to fight in fiber against giants like Nokia and Huawei.

To accelerate the shift, ADTRAN turned to acquisitions. In 2006, it acquired Luminous Networks, a manufacturer of access network equipment. In 2011, it acquired Bluesocket, an enterprise Wi‑Fi company based in Burlington, Massachusetts. In 2012, it acquired Nokia Siemens Networks’ broadband access business, based in Germany.

That Nokia Siemens deal mattered. It gave ADTRAN technology and customer reach it would have struggled to build organically, along with a real foothold in Europe. But it also brought the hard part: integration. Cross-border acquisitions don’t just add products; they add complexity—different teams, different operating rhythms, different expectations. Management attention gets pulled into the machinery of making two organizations behave like one.

By the mid-2010s, ADTRAN had repositioned itself toward fiber access—but not without scars. The company that had once been associated with exceptionally high gross margins now fought to hold the line closer to 40%. Meanwhile, the competitive landscape was shifting under its feet. Specialists like Calix leaned hard into fiber access, while Chinese manufacturers pressured pricing with low-cost alternatives.

So the question hanging over ADTRAN wasn’t whether fiber was the future. That part was settled.

The question was whether ADTRAN had moved fast enough to meet that future on its own terms—or whether, in trying to reinvent itself, it had traded its old strengths for a market where it would always be fighting uphill.

VI. The Comeback: Winning in Fiber & The Rural Broadband Opportunity (2014–2020)

Salvation came from an unlikely place: rural America.

As the biggest phone companies concentrated their fiber budgets in dense cities and suburbs—where the payback was clearest—a different kind of buildout was gathering steam in small towns and wide-open counties. Tier 2 and Tier 3 operators—regional telcos, rural electric cooperatives, municipal utilities—were under pressure to modernize. And, increasingly, they were getting help from government programs designed to push broadband into places the market alone would never justify.

These operators didn’t just need “equipment.” They needed a vendor that would pick up the phone, ship on time, and stay involved after the install.

Industry watchers noticed the pattern. Infonetics, for example, called out vendors including Calix, Alcatel-Lucent, and ADTRAN as beneficiaries of Tier 3 providers upgrading copper to VDSL2 or going straight to fiber-to-the-home. ADTRAN leaned into that opening. As ADTRAN described it at the time, a significant portion of its activity flowed through distribution partners selling into hundreds of smaller carriers—exactly the Tier 3 segment where relationships and responsiveness mattered as much as feature checklists.

There was also a practical reason so much “gigabit activity” showed up first in these smaller markets: many Tier 2 and Tier 3 operators had already deployed fiber-to-the-home. They’d done the hard, expensive part—building the network. Upgrading service tiers was suddenly more achievable. Many of those networks were built on GPON, where a single high-speed link from the central office fed a splitter serving dozens of homes.

ADTRAN’s product answer to this moment was the Total Access 5000.

The Total Access 5000 platform became the backbone of ADTRAN’s rural fiber strategy: a fiber access system built around an Ethernet core and designed to support multiple deployment models and technologies, including GPON and XGS-PON. In other words, it wasn’t a one-off box for a single architecture. It was a platform carriers could grow with—whether they were serving a sparse rural footprint, a small city, or a mix of both. Over time, the company reported the Total Access 5000 portfolio reaching hundreds of customers, tens of thousands of nodes, and deployments across dozens of countries.

Then policy kicked the flywheel into a higher gear.

Programs like the Connect America Fund (CAF II), the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund (RDOF), and state broadband initiatives directed billions toward rural broadband upgrades and new fiber builds. For operators taking that money, vendor choice carried extra scrutiny. ADTRAN worked to position itself as a “trusted American manufacturer” for carriers trying to build quickly, meet compliance requirements, and avoid supply-chain surprises.

CEO Tom Stanton put it plainly: demand and government support for fiber-based broadband were at an all-time high. He pointed to RDOF in particular, noting that winning bidders were expected to receive $9.2 billion over a ten-year period to build service to more than five million homes.

One customer type stood out as especially powerful for this wave: electric cooperatives.

The logic was simple. Co-ops already had two things most broadband newcomers spend years fighting for—poles and rights-of-way, and deep community trust. That infrastructure lowered deployment cost and time. That credibility helped adoption. For ADTRAN, co-ops were ideal: mission-driven builders who wanted a partner, not just a catalog.

NHTC, based in New Hope, Alabama, is a good example of what this looked like on the ground. As the area grew and competition intensified, NHTC needed to scale its fiber broadband offering quickly to keep up with much larger Tier 1 carriers. ADTRAN helped NHTC secure equipment on a tight timeline and roll out multi-gigabit services broadly across its footprint.

At the same time, ADTRAN made another important bet: software.

Hardware was becoming more competitive, and margins weren’t what they used to be. ADTRAN’s answer was to invest in software-driven differentiation, including Mosaic, which it described as the industry’s first open SD-Access services architecture—aimed at faster service creation and better management of broadband services at scale.

For operators like NHTC, the promise wasn’t abstract. Daniel Martin, NHTC’s general manager, described Mosaic One as a way to gain visibility into both the access network and the in-home subscriber experience—improving uptime while also reducing truck rolls by letting the Network Operations Center troubleshoot issues remotely.

By 2020, ADTRAN had pulled off a real repositioning. It wasn’t the DSL-era profit machine anymore, and it wasn’t chasing the flashiest corners of telecom. But it had become something durable: a fiber access specialist with a strong foothold among smaller operators and rural builders—customers who valued execution and support as much as technology.

The open question was what always comes next in this industry: could a niche that made strategic sense also scale into the kind of financial performance public-market investors expect?

VII. Inflection Point #2: The ADTRAN-ADVA Merger & Global Ambitions (2021–2022)

By 2021, ADTRAN had fought its way back into relevance in fiber access. But there was still a ceiling on how big it could get on its own—especially when the next phase of broadband wasn’t just about connecting the home, but also about hauling all that traffic through metro networks, into data centers, and across long-haul optical transport.

So in August 2021, ADTRAN announced the kind of move that signals a company is done playing only one position: it agreed to merge with ADVA Optical Networking. The idea was straightforward. ADTRAN was strong in broadband access and subscriber connectivity. ADVA was strong in optical transport and cloud connectivity—things like metro WDM, data center interconnect, business Ethernet, and network synchronization. Put them together and you could pitch operators an end-to-end fiber broadband networking solutions provider, not just “the box at the edge.”

The deal structure also made clear this was meant to be a true combination. The merger created a new parent company, Adtran Holdings, with ADTRAN shareholders owning about 54% and ADVA shareholders owning the rest. It was an all-stock transaction valued at roughly €789 million in equity value (about $981 million) and €759 million in enterprise value (about $896 million).

On paper, the strategic logic read clean. As the companies put it, the merger would combine ADTRAN’s leadership in fiber access, fiber extension, and subscriber connectivity with ADVA’s leadership in optical transport, data center interconnect, Ethernet services, and synchronization.

Even outside observers could see the fit. One analyst, Yu, pointed out a classic merger risk: value gets destroyed when two companies have too much overlap and spend years rationalizing duplicated products and teams. But here, ADTRAN and ADVA largely operated in adjacent layers of the network—fixed access on one side, optical transport on the other—making the combination look more complementary than redundant.

Still, “complementary” isn’t the same as “category-defining.” Some analysts were quick to tamp down the hype. John Lively, principal analyst at LightCounting, told SDxCentral the deal wasn’t going to reshape the optical networking industry. In his view, the two companies would improve their position together, but they still wouldn’t meaningfully threaten the biggest players. He suggested the deal might put more pressure on smaller competitors such as Infinera and Calix.

That scale gap was real. Together, ADTRAN and ADVA had generated about $1.2 billion in revenue the prior year, while ADTRAN’s deal presentation showed much larger totals over the same period for incumbents like Nokia and Ciena.

The companies also promised synergies—along with the unavoidable bill for getting there. They targeted annual run-rate pre-tax synergies of about $52 million by year two after closing, and estimated roughly $37 million in one-off costs to achieve them.

Then, in July 2022, the deal became official. ADTRAN Holdings announced it had closed the business combination with ADVA Optical Networking SE after securing regulatory approvals and shareholder consent. Structurally, ADTRAN Holdings became the parent of ADTRAN, Inc., and tendered ADVA shares were exchanged for shares of ADTRAN Holdings, making ADTRAN Holdings the majority shareholder of ADVA. The company also stated it intended to enter into either a domination agreement or a domination and profit and loss transfer agreement to further drive integration.

The acquisition immediately broadened what ADTRAN could sell. It added end-to-end data transport products to complement ADTRAN’s access networking portfolio, and it brought in ADVA’s subsidiaries—most notably Oscilloquartz, the Switzerland-based timing and synchronization specialist.

But the timing was brutal.

Integration was ramping just as the telecom equipment market began to soften. After COVID-era supply chain chaos, many customers had over-ordered to protect themselves. When supply finally loosened, those same customers were sitting on inventory—and spending slowed sharply in 2023 and 2024.

The financials reflected that comedown. In 2024, ADTRAN Holdings reported revenue of $922.72 million, down 19.70% from $1.15 billion the year before. Losses widened as well: the company reported losses of -$447.89 million, 68.2% worse than in 2023. The weakness showed up on the European side too. In fiscal year 2024, ADTRAN Networks SE saw revenue fall 28.6%, and ADTRAN Holdings, Inc. reported a net loss of $450.9 million amid the broader industry slowdown.

Those losses weren’t only macro. They were also operational gravity. Cross-border mergers are hard under the best conditions—two continents, different cultures, different systems, different customer expectations. ADTRAN now had to integrate while demand was cooling, and that combination tends to expose every seam in the deal.

The merger gave ADTRAN a bigger story and a broader product set. It also raised the bar: now it had to prove it could execute at global scale, in a down cycle, with the eyes of both customers and public markets watching.

VIII. The Modern Era: Government Funding, Fiber Wars & Recovery (2022–Present)

Even with integration still in progress, ADTRAN entered 2024 and 2025 with a rare kind of tailwind: Washington. The Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment program—BEAD—set aside $42.5 billion to expand high-speed internet to underserved Americans, the largest federal broadband investment ever.

BEAD wasn’t just about writing checks. It came with rules. Through the Build America, Buy America framework, a meaningful portion of that spending was expected to favor domestically produced equipment. ADTRAN moved quickly to position itself as a “ready on day one” supplier. The company pointed to a commitment to U.S.-based manufacturing going back more than three decades and highlighted its BABA-compliant fiber access portfolio as the kind of gear that could help carriers hit BEAD timelines while meeting sourcing requirements.

That Huntsville footprint—long a cultural identity for ADTRAN—suddenly became a strategic asset. The company announced an expansion of advanced telecommunications manufacturing at its state-of-the-art facility in Huntsville, Alabama, aiming to meet rising demand for domestically produced network electronics. It earmarked up to $5 million for the effort and said it could create up to 300 jobs.

In 2024, ADTRAN also self-certified as “Buy America-compliant” with the U.S. Department of Commerce, landing on a list that service providers could reference as they applied for BEAD funding.

Then came the frustrating part: the money didn’t move.

BEAD funding was slow to materialize in the field, which meant it was slow to show up in ADTRAN’s order flow. CEO Tom Stanton spelled it out: “The way BEAD will impact us is a direct flow of dollars from the stimulus program to our customers and from those customers onto us, but that has not started happening yet in any material way.” With allocations still in the early innings, carriers were still figuring out how to participate.

That hesitation hit exactly where ADTRAN had built its comeback—smaller operators. “The Tier 3 space, predominantly what people think about being the biggest recipients of BEAD funding, slowed down last year,” Stanton said. “The general thought is they are waiting to see how the BEAD program will play out.”

But even as timelines slipped, the underlying bet didn’t change. In Stanton’s view, broadband dollars would eventually flow, and when they did, they would mostly fund fiber. “Money will flow, and it will be predominantly for fiber,” he said. “Even without BEAD, it was going to be built out.”

And by late 2025, the numbers finally started to look like a company catching its footing again.

ADTRAN Holdings reported unaudited results for the third quarter ended September 30, 2025, with revenue of $279.4 million—up 23% year over year. Stanton said, “Our third quarter revenue and operating margin were above the midpoint of our expectations, with robust sequential and year-over-year growth. The results reflect disciplined execution, broad-based growth, and continued momentum in a healthy industry environment. We’ve strengthened our capital structure, improved efficiency, and remain focused on key areas of the company.” He added, “We look forward to a strong finish to the year.”

All three business categories delivered double-digit year-over-year growth. The company also completed a $201 million financing transaction that lowered borrowing costs and increased financial flexibility.

Most telling was where momentum showed up: optical. Optical Networking solutions grew 47% year over year and 15% sequentially, driven by strength in Europe—exactly the kind of benefit the ADVA combination was supposed to unlock. The growth reflected access to European markets and optical transport products that legacy ADTRAN simply didn’t have, while access and aggregation continued to benefit from ongoing fiber deployments in North America and Europe.

Stanton also pointed to continued customer adds in the core access business: “Tier 2, Tier 3s, we added somewhere around 10 or 11 carriers during the quarter just for fiber access alone.” In other words, as service providers worked through their post-supply-chain inventory glut—especially in optical—ADTRAN was again showing up on the right side of purchasing decisions.

And that’s the shape of the modern ADTRAN story: a company built on the unglamorous realities of deployment now trying to ride a once-in-a-generation funding wave, while proving that its cross-Atlantic merger can translate into something more than a broader product catalog—real growth, in the categories that matter.

IX. Business Model Deep Dive & Competitive Dynamics

ADTRAN’s business today is best understood as a two-part machine. Through ADTRAN Holdings, it sells networking platforms, software, systems, and services across the U.S. and Europe, with operations spanning the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, and beyond. Financially, it reports two operating segments: Network Solutions, and Services & Support.

The product lineup reflects what the company has become since the fiber pivot and the ADVA combination: equipment that lives at the edge of the network and equipment that hauls traffic deeper into it. On the access side, that includes residential gateways, optical network terminals and units for GPON and XGS-PON, optical line terminals, and legacy copper access gear. On the transport and timing side, it includes optical transport and “optical engine” solutions, plus Oscilloquartz timing and synchronization products. Layer in packet aggregation, carrier Ethernet interface devices, and the usual routing and switching, and you get the picture: ADTRAN isn’t trying to sell one killer box. It’s trying to be a full broadband networking supplier, from subscriber to backbone.

Revenue follows a straightforward pattern for this kind of company. Most of it comes from selling hardware to service providers, enterprises, and government customers, with software licenses and professional services layered on top. Then there’s the annuity-like piece: support and maintenance contracts that keep networks running and keep ADTRAN involved long after the install.

That’s the business. The harder part is the arena it competes in.

Fixed-line broadband access is a fragmented, high-pressure market. Vendors fight on performance, standards compliance, and, often, price. In North America, ADTRAN’s most direct rival is Calix—another fiber access specialist, and one with a formidable software story of its own. ADTRAN’s bet is that Mosaic One and its broader software capabilities narrow that differentiation gap, giving operators more tools across marketing, customer success, and operations to deliver a better subscriber experience, not just a faster connection.

ADTRAN also leans hard into a philosophical positioning: open, standards-based access. The pitch is flexibility—modular architectures that reduce vendor lock-in, shorten integration cycles, and make it easier to deploy new applications without disrupting service. In a world where operators increasingly want multi-vendor networks and the freedom to evolve without ripping everything out, that “open” posture is meant to be a strategic advantage.

Zoom out globally and the competitive set widens fast. In optical transport, ADTRAN now finds itself compared with giants like Nokia, Cisco, and Ciena. In fiber access, it’s competing with Nokia and, in many regions, Huawei—though Huawei is effectively shut out of much of the West due to security concerns. ADTRAN’s stated approach is not to outmuscle these incumbents head-on in their strongest accounts, but to win where execution, responsiveness, and customer intimacy matter more than sheer scale.

Geography matters here too. Today, about 85% of ADTRAN’s revenue comes from the U.S. and Europe. As Tom Stanton put it, “Europe has been fairly strong and has grown as a higher percentage mainly because of fiber to the premises rollouts in Europe.” In other words: the merger didn’t just add products. It pulled ADTRAN deeper into a region where fiber deployments are accelerating—and where the company now has a real seat at the table.

X. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is one of those markets where nobody gets to relax. ADTRAN competes against giants with deep pockets and broad portfolios, like Cisco and Nokia; against specialists that live and breathe fiber access, like Calix; and, historically, against ultra-low-cost manufacturers such as Huawei and ZTE—though regulatory restrictions have increasingly boxed them out of Western markets. Pricing is a knife fight, product cycles move fast, and staying relevant requires constant R&D just to keep your seat at the table.

Threat of New Entrants: MEDIUM

Telecom gear isn’t an app you can ship and iterate on in public. New entrants face real barriers: carrier-grade reliability expectations, long certification processes, and customer relationships that take years to earn. Building hardware at scale also demands real capital. But the industry is also shifting toward open, disaggregated architectures, and that trend matters: it lowers the “full system” barrier by letting newcomers compete in narrower slices of the stack instead of needing to deliver the whole end-to-end platform on day one.

Supplier Power: MEDIUM-HIGH

In telecom equipment, silicon is destiny—and the silicon vendors know it. Suppliers like Broadcom and Marvell carry outsized leverage, and the 2020–2023 supply chain crunch made the dependency painfully visible. When critical components get constrained, it doesn’t matter how strong demand is: you can’t ship what you can’t build. And for a company like ADTRAN, vertical integration into semiconductors isn’t a realistic escape hatch.

Buyer Power: HIGH

On the other side of the table are customers who buy in huge volumes and negotiate like professionals—carriers such as AT&T, Verizon, and Deutsche Telekom. They can dictate terms, run competitive bake-offs, and pressure pricing over multi-year contracts. Smaller operators have less leverage individually, but they’re often extremely price-sensitive. Combine that with long sales cycles and competitive bidding, and the balance of power tilts heavily toward the buyer.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM

Fiber is still the gold standard when you want high bandwidth and low latency. But alternatives are getting better, and they’re “good enough” in more places than they used to be. Fixed wireless access over 5G and satellite broadband like Starlink can substitute for fiber in certain geographies and use cases, especially where running new fiber is slow or expensive. Meanwhile, cable operators can keep upgrading their networks with DOCSIS and stay competitive in residential broadband without rebuilding from scratch.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Assessment

Scale Economies: WEAK — There are some benefits to scale in manufacturing and procurement, but this isn’t a winner-take-all market. Smaller, regional-focused players can still build sustainable businesses.

Network Effects: NONE — Telecom equipment doesn’t naturally compound value through network effects the way consumer platforms do. If anything, the closest analogue would be software management platforms, which could develop modest “ecosystem” pull over time, but it’s limited.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE — ADTRAN has long pitched itself as the nimble, cost-effective alternative to the giants. Today, its emphasis on open, standards-based networking also sets it in philosophical contrast to more proprietary approaches, including vendors like Cisco.

Switching Costs: MODERATE — Once equipment is deployed in a live network, swapping vendors is painful. But refresh cycles and new buildouts constantly create openings for competitors, and interoperability standards reduce lock-in compared to closed systems.

Branding: WEAK — This is a technical, B2B sale. Brand helps at the margin, but performance, support, and trust built over time tend to win deals. Being viewed as a “trusted partner” matters—just not in the way a consumer brand does.

Cornered Resource: WEAK — ADTRAN has plenty of patents, but so does everyone else who’s been in this market for decades. Huntsville talent and a European footprint are meaningful assets, but not exclusive ones.

Process Power: MODERATE — This is where ADTRAN’s real edge tends to show up: deep telco experience, an engineering-centric culture, and hard-earned expertise serving rural and regional operators. That said, cross-border integration after the merger adds friction, and it has likely diluted efficiency in the short term.

Overall Assessment: ADTRAN doesn’t have a single, overwhelming “power” that guarantees sustained, above-market returns. It’s a solid business in a punishing industry, where advantages are earned through execution and focus more than structural moats. The ADVA merger was, in part, a bid to strengthen those advantages through greater scale and broader scope—but whether that becomes a durable edge is still playing out.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Thesis

The Bull Case

The bullish read is that ADTRAN is in the middle of a real turnaround. After the bruising 2023–2024 stretch—customers burning down excess inventory while the company absorbed merger integration costs—the setup looks meaningfully better. Demand didn’t disappear. It got delayed. And the secular forces pushing networks from copper to fiber kept moving forward.

Management’s argument is basically: the money is coming, and it’s aimed squarely at fiber. As CEO Tom Stanton put it, “Government subsidies in the U.S. for building out fiber infrastructure are expected to be more than double in the upcoming years, including funding as part of the Infrastructure Bill, Rural Digital Opportunity Fund, and a growing base of state-level funding here in the U.S.” He added that “in Europe, similar initiatives are underway with more than $45 billion of government funding programs proposed to provide universal high-speed broadband connectivity.”

In the U.S., BEAD is the headline: $42.5 billion in federal funding tied to expanding high-speed access. ADTRAN’s bull case leans heavily on being a Buy America-compliant supplier—positioned to benefit if operators want or need domestically compliant gear to hit program requirements and timelines. Zoom out further and the broader thesis is simple: the copper-to-fiber transition is accelerating. “There are whole-country initiatives, including the U.S., to convert to fiber, and BEAD is a stimulus,” Stanton said. “The copper-to-fiber migration is happening all through Europe,” too.

Then there’s the merger logic. The ADVA deal was painful to integrate, but the optimistic view is that it created a more complete fiber networking company than ADTRAN could have built on its own. ADTRAN brings fiber access and aggregation, residential and enterprise connectivity, and cloud-based network optimization and customer experience applications. ADVA brings fiber backhaul and data center interconnect, enterprise fiber access and connectivity, plus network synchronization. Together, the pitch is one platform that spans access, transport, and timing—covering more of what operators actually need as networks converge.

And the bulls can point to recent results as proof that this isn’t just a slide-deck story. The third quarter of 2025 suggested momentum was building, and Stanton and CFO Timothy Santo said they expected operating margin expansion in 2026. They also laid out a clear operating goal: maintain R&D investment while controlling sales expenses, with a revenue level around $315 million as the threshold to reach double-digit operating margins.

The Bear Case

The bear case is that ADTRAN is still ADTRAN: a company in a tough, commoditizing hardware market, competing against much larger players, with limited room for error.

Start with the basics: profitability has been inconsistent. In fiscal year 2024, ADTRAN reported a net loss of $450.9 million amid a broader industry slowdown. Even with the more recent revenue recovery, the company remained only marginally profitable on a non-GAAP basis and unprofitable on a GAAP basis.

Then there’s integration risk—because cross-border mergers don’t get easier just because the strategy makes sense. Two companies, two continents, different cultures, different systems. The operational stumbles showed up in the financial results, and the skeptical view is that this kind of complexity can linger for years, quietly draining focus and margins.

Competition doesn’t let up, either. Cisco, Nokia, and Calix all have deep resources and entrenched positions. And while Chinese manufacturers face restrictions in many Western markets, they still exert pricing pressure globally—keeping a tight ceiling on hardware margins and making “better product” a necessary but not sufficient condition for long-term success.

Finally, there’s the timing risk around BEAD and public funding more broadly. Even if the demand is real, the path from legislation to checks to actual purchase orders can be slow and politically fragile. Regulatory delays and grant complexity can push deployments out. There’s also speculation that the new Trump administration could materially impact BEAD funding allocations. At the same time, even skeptics acknowledge the underlying need for fiber-based broadband remains high—the question is when and how cleanly the dollars translate into revenue.

Key Questions for Investors

- Can ADTRAN reach the double-digit operating margins management is targeting?

- Will BEAD funding convert into meaningful revenue growth, or arrive slower than expected?

- Can ADTRAN’s software platform differentiate enough to blunt hardware commoditization?

- What’s the endgame: a durable independent operator, or an eventual acquisition target?

XII. Key Performance Indicators to Track

If you want to know whether the ADTRAN story is actually improving—or just sounding better on earnings calls—there are three metrics that tend to tell the truth.

1. Non-GAAP Operating Margin

This is the clearest scoreboard for whether the turnaround is real. Management has said it believes the business can reach double-digit operating margins once quarterly revenue is around $315 million. So the question each quarter is simple: are margins steadily climbing as revenue recovers, or are costs and integration friction eating the gains?

2. Revenue Mix: Network Solutions vs. Services & Support

ADTRAN sells a lot of hardware, and hardware is where the margin knife fights happen. The long-term margin story depends on a bigger contribution from Services & Support—where recurring support, professional services, and software can carry better economics than boxes alone. Track how that mix shifts over time, and whether software offerings like Mosaic One are growing in a way that’s visible in the segment results, not just in product messaging.

3. Customer Acquisition: New Carrier Wins

In a market where customers can be slow to spend and quick to churn vendors, new wins matter. Stanton highlighted that “Tier 2, Tier 3s, we added somewhere around 10 or 11 carriers during the quarter just for fiber access alone.” That kind of steady customer adds is a good signal that ADTRAN’s positioning is resonating. If that pace slows, it’s often an early warning that competition, pricing pressure, or execution issues are creeping back in.

XIII. Lessons for Founders & Investors: The ADTRAN Playbook

What Founders Can Learn

Regulatory change creates opportunity. ADTRAN didn’t spring from a lone technical breakthrough. It sprang from the AT&T breakup—a rule change that forced an entire industry to buy differently. The lesson is simple: some of the best startup openings come when policy unbundles a market and creates space for new suppliers. Founders should track regulation with the same seriousness they track product roadmaps.

Niche mastery before expansion. ADTRAN earned trust by getting very good at one unglamorous thing—carrier access gear—before moving into the next layer. That focus bought it credibility with operators and created relationships that mattered when competition intensified. The playbook: win a narrow wedge, then expand adjacently from a position of strength.

Geography matters for talent. Huntsville wasn’t a branding exercise. It was a talent strategy. ADTRAN built in a city shaped by NASA and defense work, where systems-minded engineers were abundant and competition for them was lower than in the usual tech hubs. The takeaway isn’t “move to Alabama.” It’s that talent clusters exist outside Silicon Valley—and sometimes the best advantage is being where great people are, but few startups are bidding for them.

Technology transitions are existential. The shift from copper to fiber wasn’t a “new product line” moment. It threatened ADTRAN’s core. When your company is built on a specific technology, the next platform shift is always a potential extinction event. Surviving requires brutal honesty about what’s changing—and the willingness to cannibalize today’s winners before the market does it for you.

What Investors Can Learn

Mergers are difficult. The ADVA merger broadened ADTRAN’s capabilities and made the strategy look cleaner on paper. In reality, integration is a multi-year tax—especially across borders, cultures, and systems. Investors should assume synergy targets take longer than promised and cost more than modeled, even when the strategic fit is real.

Government programs move slowly. BEAD created massive headline tailwinds, but headlines don’t equal purchase orders. Dollars move from legislation to allocations to grant rules to operator plans—then, finally, to vendors. If your thesis depends on government funding, you’re also signing up for bureaucratic timelines.

Hardware commoditization is relentless. ADTRAN’s margin story is what happens when a great hardware niche matures: pricing power erodes, competitors multiply, and yesterday’s premium becomes tomorrow’s table stakes. The durable value tends to shift toward software, services, and customer experience—areas that are harder to compare line-by-line in a bid.

Timing matters. ADTRAN caught DSL early and rode it to a golden era. It arrived later to fiber and paid for it. The investing lesson is that being right about where the world is going isn’t enough. The real money is made—or lost—on when the transition hits, and whether a company moves before it’s forced to.

XIV. Epilogue: The Road Ahead

ADTRAN headed into 2026 at a moment that felt both familiar and new. Familiar, because telecom never stops shifting under your feet. New, because for the first time in a while, the company seemed to have its balance back. The hardest integration work from the ADVA combination was largely in the rearview mirror. Growth had reappeared. Margins were moving in the right direction. And BEAD—slow, bureaucratic, and maddening—still sat in the background as a once-in-a-generation pool of demand waiting to be unlocked.

The product story was evolving too, and in ways that made the merger thesis feel less theoretical. ADTRAN’s SDX 6400 Series OLT was deployed by Netomnia to enable the UK’s first commercial 50G PON service—exactly the kind of “next step” upgrade that fiber operators want once the physical network is in the ground. On the optical side, the company also launched its FSP 3000 IP Open Line System (OLS), a compact, plug-and-play platform designed to scale per wavelength from 400Gbit/s up to 1600Gbit/s, aimed at rising demand from AI-driven workloads and data center connectivity.

Under the hood, the roadmap kept pushing forward. ADTRAN’s implementation of 50Gbit/s passive optical network technology centered on the SDX 6400 family, positioning it for the next generation of access upgrades. And in collaboration with Orange, ADTRAN demonstrated a 400Gbit/s data transmission system using quantum key distribution—pairing quantum-safe encryption with classical cryptographic methods to secure data across a 184 km system.

The competitive landscape didn’t stand still, either. Chinese vendors being excluded from many Western markets eased one source of pricing pressure, at least in the geographies that mattered most to ADTRAN. At the same time, the broader industry continued to consolidate—partly because the economics of selling “boxes” are unforgiving, and partly because customers increasingly want fewer vendors that can cover more of the network.

Scenario Analysis:

Best Case: BEAD funding finally accelerates real deployments. ADTRAN captures meaningful share in rural fiber builds while growing its optical transport business in Europe. Operating margins expand into the double digits, and the market narrative shifts from “messy merger turnaround” to “durable broadband infrastructure compounder.”

Base Case: BEAD arrives, just slowly. ADTRAN holds its ground, adds customers steadily, and posts modest growth with incremental margin improvement. It remains a credible mid-tier player in a consolidating market—good at what it does, but not a breakout winner.

Bear Case: Integration friction lingers longer than expected, competitors press harder on price, and the funding environment gets tangled in politics and delays. ADTRAN’s assets and footprint start to look more valuable inside a larger platform, and the endgame becomes a sale rather than a standalone renaissance.

Either way, the through-line of the ADTRAN story hasn’t changed: resilience through reinvention. From Mark Smith starting in 1985 to a transatlantic company selling access, transport, and timing, ADTRAN has survived transitions that have wrecked bigger, louder names. Whether the current strategy ultimately becomes a clean success is unknowable in advance. But the company’s history suggests something important: it tends to keep finding a way to stay in the game.

For investors, that’s the pitch and the tension. ADTRAN offers exposure to the long arc of fiber deployment without the valuations of the most celebrated tech names. But the risks aren’t cosmetic: competition is relentless, government dollars move slowly, and integration is never truly “done” until the financials prove it.

Still, the broader truth remains. Not every company gets to be Google or Apple. Some companies build the infrastructure that makes those companies possible. And as the world keeps demanding more bandwidth, lower latency, and more reliable connectivity in more places, that unglamorous work only gets more essential.

XV. Further Reading & Resources

Books & Articles: - The Master Switch by Tim Wu (telecom industry history & regulation) - ADTRAN’s annual 10-K filings (2015–2024) for a deeper look at strategy, risks, and financials - Light Reading’s ADTRAN coverage archive (telecom industry reporting and context)

Key Reports & Analysis: - Federal Communications Commission: BEAD program documentation - National Telecommunications and Information Administration: Build America, Buy America guidance - Industry analyst reports from Dell’Oro Group and LightCounting on fiber access markets

Primary Sources: - ADTRAN Holdings investor presentations (2022–present) - Quarterly earnings call transcripts - Fierce Telecom industry news coverage

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music