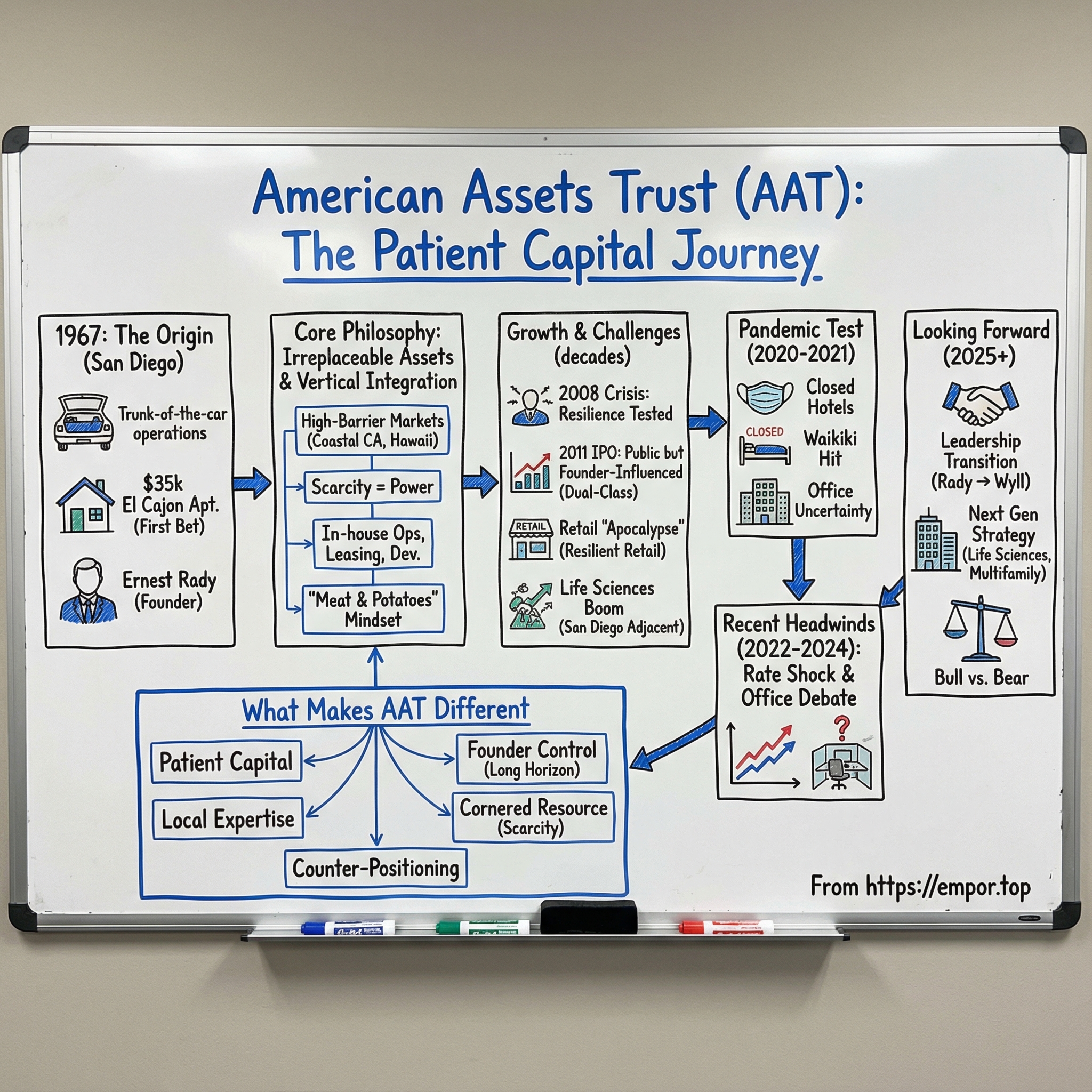

American Assets Trust: The Story of San Diego's Patient Capital REIT

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s 1967, and a young Canadian lawyer named Ernest Rady has just landed in San Diego. He’s not chasing a booming market or some grand business plan. He’s there because his wife, Evelyn, needs a different climate—Winnipeg’s allergies had become unbearable.

“We tried several places, and we ended up in San Diego, and she hasn't had allergies in 60 years,” Rady would later say. “So that was a good move.”

It turned out to be a good move in more ways than one.

Not long after arriving, Rady made his first real estate bet: a small apartment property in San Diego County that he bought for $35,000. In the beginning, there was no office, no staff, no institutional capital—just Rady, hustling deals and running the operation out of the trunk of his car.

Fast forward nearly six decades, and that trunk-of-the-car business has become American Assets Trust: a full-service, vertically integrated, self-administered real estate investment trust headquartered in San Diego. Over more than 55 years, it has built a portfolio of premier office, retail, and residential properties across the United States—acquiring them, improving them, developing them, and managing them in-house.

Today, the scale is real. As of September 2025, American Assets Trust reported gross real estate assets of $3.7 billion and liquidity of $538.7 million. The portfolio included roughly 4.3 million rentable square feet of office, about 2.4 million rentable square feet of retail, one mixed-use property with approximately 94,000 rentable square feet of retail plus a 369-room all-suite hotel, and 2,302 multifamily units.

But the real question here isn’t the square footage or the balance sheet.

It’s whether the philosophy that built this company still works. In a world of mega-REITs with national footprints—and private equity roll-ups engineered for speed—can a family-controlled, regionally focused platform still win? Can patient capital and local expertise hold their own against giants like Alexandria Real Estate in life sciences, or the sheer force of Blackstone?

That’s what this story is really about: how a Winnipeg immigrant quietly built one of the West Coast’s most distinctive real estate businesses, how it went public without surrendering founder control, and how it positioned itself for a generational handoff at a pivotal moment in the company’s evolution.

II. The Founding Families & San Diego Real Estate Origins (1967–2000s)

To understand American Assets Trust, you have to start with Ernest Rady. He fits the classic immigrant-success template—hardworking, ambitious, self-made—but his path doesn’t sit neatly in any one box. After growing up in Winnipeg in a family surrounded by business, Rady and his wife, Evelyn, moved to San Diego in 1966, when he was 29. The catalyst wasn’t a market call. It was health.

Rady had married while in law school, and Evelyn’s asthma and allergies were made worse by Manitoba’s wheat fields. They stayed in Winnipeg until after his father died and Rady finished law school—where he earned the Law Society Award for Academic Achievement in Law—then they left. “We ended up in San Diego,” he later said. “We went from one of the worst climates in North America to one of the best.”

San Diego didn’t just give them better air. It gave Rady room to build.

The Serial Entrepreneur

Rady’s real estate story is only part of what makes him unusual. He wasn’t a lifelong “property guy” who discovered a niche and stayed in it. He was a builder of businesses—plural—and he kept widening the circle.

In 1962, at 25, he became half owner of a construction equipment rental company. That same year, he bought control of Western Homes. In 1967, he merged Western Homes with a small oil and gas company, Summit Resources, which eventually went public. In 1968, he bought a majority interest in Dixieline Lumber, then sold his stake in 1975 to Weyerhaeuser. And in 1971, he started Western Thrift and Loan, which later became Westcorp.

Along the way, he got involved in a grab bag of local ventures: a beer distributorship, a partnership group that briefly owned the San Diego Padres, and a broadcast station.

Westcorp, though, is the one that best captures how he thought. It began with humble beginnings—“started out of a trailer with $850,000,” as he put it—and eventually was purchased by Wachovia Bank for $3.9 billion. Rady’s explanation for how he did it is revealing: “I built that business by continually raising my sights and associating with good people. The business can't walk out the door if an employee decides to leave. Also, I never invested in anything too technical. I'm a meat and potatoes kind of guy.”

That “meat and potatoes” mindset—practical, controllable, built around people you trust—shows up all over American Assets.

The San Diego Thesis

So why bet on San Diego in the first place? In the 1960s, it wasn’t the obvious choice. Los Angeles was the economic engine. San Francisco had the financial establishment. San Diego was still largely a Navy town—important, growing, but not yet the kind of city outsiders circled as a real estate goldmine.

Rady built a simple rule for himself: operate in high-value markets where the barriers to entry stay high. Over time, that meant focusing on places like Hawaii, San Diego, San Francisco, Monterey, Oregon, and Washington.

The logic was straightforward and, in hindsight, powerful: pick markets where new supply is naturally hard to create. Coastal constraints, mountains, islands, and zoning rules all do the same thing—they make scarcity durable. If you own great real estate inside those boundaries, you’re not just buying buildings. You’re buying permanence.

American Assets was formed in 1967, and its first real estate investment was modest: a $35,000 interest in an apartment complex in El Cajon. From there, the company stayed private for 44 years, quietly assembling what Rady would describe as “irreplaceable” assets.

The Culture of Vertical Integration

From early on, American Assets didn’t want to be a passive owner relying on outside firms to do the real work. Instead, it built the capabilities inside the company—property management, leasing, development, construction. The business positioned itself as a full-service, vertically integrated and self-administered real estate investment trust, headquartered in San Diego, with decades of experience acquiring, improving, developing, and managing premier retail, office, and residential properties across the United States.

This wasn’t just about saving fees. It was about control. When your team handles the leasing, the tenant relationships, and the capital projects, you don’t manage real estate by spreadsheet. You manage it by knowing the properties intimately—what’s working, what’s not, and what needs to be fixed before it becomes a problem.

And when your strategy is to buy and hold “forever,” that kind of operating muscle compounds.

The 2008 Crisis and a Near-Death Experience

Then came 2008—and it nearly wiped them out.

That year, Forbes ranked Rady as the 743rd richest person in the world, and American Assets was valued at $1.8 billion. But the recession hit hard, and the damage was personal. Rady later recalled, “I remember going to an ATM that rejected my card. I was struggling to survive. It was the most difficult time of my life. I don't sit around licking my wounds, though at the time it was very troublesome. We have made a comeback, frankly. I made back the money I lost.”

The crisis exposed both sides of real estate. The risk is obvious: leverage can turn a downturn into an existential threat. But the resilience matters too. High-quality assets in supply-constrained markets don’t just bounce back—they tend to recover faster than commodity properties in places where developers can flood the market the moment capital returns.

And that’s why this part of the origin story isn’t trivia. It explains the conservatism that shows up later: why AAT talks the way it does about leverage, liquidity, and survival. They don’t treat downside as theoretical. They’ve lived it.

III. The Portfolio Strategy: High-Barrier Markets & Trophy Assets

Walk through American Assets Trust’s portfolio and one thing jumps out fast: this isn’t a collection of generic office parks and interchangeable retail pads. These are properties where the address does most of the heavy lifting—places where supply is boxed in by oceans, hills, zoning, and politics. In other words: scarcity you can’t manufacture.

Waikiki Beach Walk: The Hawaii Bet

Waikiki Beach Walk sits in the middle of the action in Honolulu—between Kalakaua Avenue, Waikiki’s marquee shopping strip, and the beach itself. Waikiki has long been Hawaii’s top visitor destination, drawing more than 5 million domestic and international visitors annually. That foot traffic is the fuel.

The property is a mixed-use destination anchored by a 369-room, all-suite, two-tower Embassy Suites hotel, built above an outdoor entertainment plaza. Down at street level, it’s designed to keep people lingering: open-air performances, a lineup of more than 40 retailers, and six restaurants serving both locals and the year-round tourist flow.

Waikiki Beach Walk was developed in 2007 by Outrigger Enterprises Group in partnership with American Assets Trust. And it captures AAT’s strategy in one snapshot—the upside and the trade-offs. The upside is obvious: beachfront retail in Waikiki is as close to “no new competition” as real estate gets. The trade-off is just as real: when your customers arrive on airplanes, the business can swing hard when travel slows, something the COVID-19 pandemic would later make painfully clear.

Torrey Reserve and La Jolla: Life Sciences Adjacency

Back in San Diego, AAT’s playbook looks different—but it’s still the same core idea: own the irreplaceable.

Torrey Reserve is a large, amenity-rich campus in the Carmel Valley/Del Mar Heights area, right at the intersection of I-5 and SR-56. It includes eight multi-tenant Class-A office buildings, three medical office buildings, and three specialty mixed-use buildings. The pitch isn’t just the buildings. It’s the ecosystem: quick access to affluent coastal communities like La Jolla, Del Mar, and Solana Beach, plus sweeping views of the Pacific Ocean and Torrey Pines State Park.

Then there’s La Jolla Commons, AAT’s statement piece in the University Town Center submarket. It’s a LEED Gold and Platinum campus made up of two 13-story towers, one 11-story tower, and two parking structures. It’s walkable to major dining, high-end retail, and entertainment, with immediate freeway access—and a “soon-to-be-completed” UC San Diego Blue Line connection that helped frame it as transit-served, not just car-served.

Just as importantly, it’s planted in the middle of San Diego’s technology and biotech orbit, near major employers and the University of California, San Diego.

The Acquisition Strategy

In 2019, AAT made its largest single acquisition: La Jolla Commons. Ernest Rady called it out plainly at the time: “We are thrilled to expand into the University Town Center submarket of San Diego and proud to add La Jolla Commons to our portfolio of trophy assets.”

The deal was priced at $525 million, reduced by an approximately $11.5 million seller credit, and funded with a mix of cash on hand plus draws on the company’s existing credit facility.

The campus included buildings delivered in 2008 and 2014 and totaled roughly 724,000 square feet. One tower—about 421,000 square feet—was 100% leased to credit-rated LPL Financial, giving AAT the kind of stable, predictable income it loves to underwrite.

This is the AAT pattern: pay up for a premier asset in a supply-constrained pocket, lean on in-house operations to keep it performing, and hold for the long haul. The stability buys time. The location creates pricing power. And in this case, the campus also came with future potential.

That future started showing up in the next phase of the campus. La Jolla Commons III, the third office development within the project, came online in 2023. It’s an 11-story building with floorplates around 20,000 square feet, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill and built by Whiting Turner Contracting Co. One early data point on demand: JLL signed a 15,869-square-foot lease at the 212,800-square-foot tower.

Why AAT Avoided Sun Belt Sprawl

There’s also something you don’t see on AAT’s map: the usual Sun Belt checklist—Phoenix, Las Vegas, Dallas, Atlanta.

Those markets have been magnets for corporate relocations and population growth, and plenty of real estate capital has followed. But AAT has largely stayed put, and the reason goes back to the company’s central belief in “irreplaceable assets.”

In much of the Sun Belt, land is abundant and zoning tends to be more permissive. When demand heats up, new supply can show up quickly. That’s a fundamentally different game than coastal California or Hawaii, where the constraints don’t loosen just because rents rise.

So AAT’s portfolio is making a specific bet: scarcity over sprawl. The reward is typically stronger pricing power when cycles turn favorable. The cost is fewer easy lanes to expand simply by building the next new thing on the edge of town.

IV. The 2011 IPO: Going Public While Staying Private

After 44 years as a private company, American Assets went public in January 2011. The timing wasn’t random. It was both an opening in the market—and a turning point for the family.

In 2011, American Assets Trust was formed to succeed to the real estate business of American Assets, Inc., the privately held company founded back in 1967. Same real estate DNA. New wrapper.

The Context: Post-Crisis Capital Markets

The 2008–2009 financial crisis had crushed property values and, for a while, shut the financing window almost entirely. By 2011, the panic had faded enough for capital markets to function again. REIT stocks had rebounded off the bottom, and institutional investors were returning to real estate—cautiously, but visibly.

For American Assets, an IPO solved multiple problems at once. It opened access to public equity for future acquisitions. It created liquidity for long-time limited partners who’d been effectively locked into a private structure for decades. And for the Rady family, it helped with estate planning—without giving up the steering wheel.

At the time of the IPO, the company controlled roughly 3.1 million square feet of rentable space, 2,122 multifamily units, and a 369-room, all-suite hotel.

The Structure: Maintaining Family Control

What made AAT’s IPO different wasn’t just that it went public—it was how it did it.

As of November 2025, the shareholder base is dominated by institutions like BlackRock and Vanguard, who together represent the kind of long-duration, low-drama ownership most REITs want. But inside that “institutional” label sits the defining fact of AAT: founder Ernest S. Rady still held a stake large enough to shape outcomes. With institutional ownership over 90% and Rady at 30.03%, the company ended up with an unusual blend—widely owned in the market, but meaningfully influenced by the person who built it.

That’s the trade. Minority shareholders get less of a governance voice, but more alignment with a deeply invested owner-operator whose incentives are tied to the long game. It’s less “typical REIT run by professional managers,” and more “public company with a controlling philosophy”—closer in spirit to a founder-led compounder than a committee-driven landlord.

Early Skepticism and Proving Operational Discipline

Of course, Wall Street doesn’t give anyone credit for a philosophy. It wants proof.

After the IPO, AAT had to show that the private-company instincts—patience, selectivity, operating control—could translate into public-company performance. Over time, the company said it substantially increased its Net Asset Value from where it started in 2011, driven by disciplined, accretive acquisitions, increased occupancy, and strong same-store net operating income growth.

That’s the crux of the AAT story in public markets: a family-run operator stepping into the spotlight without changing its core identity.

And it leaves investors with the enduring question: does founder control create value through long-term thinking and disciplined capital allocation—or does it introduce governance risk through entrenchment? With AAT, you’re not just buying the buildings. You’re buying the structure, too.

V. The 2010s: Navigating Recovery, Retail Apocalypse, and Market Cycles

The years after the IPO were the real test. It’s one thing to pitch “patient capital” in a roadshow. It’s another to live it quarter after quarter, with public shareholders watching—and with the temptation to grow fast just because you finally can.

Post-IPO Growth Strategy

AAT didn’t sprint. Instead of spraying IPO-era capital across whatever was available, it stayed picky and used the public platform to keep building in places it already understood.

In 2017, the company agreed to acquire Pacific Ridge Apartments in San Diego for about $232 million. The property—533 units, completed in 2013—fit the diversification push into multifamily and sat in the middle of the city with access to transit and major demand drivers like the airport, the zoo, shopping, dining, and universities. At the time, it was about 97% leased, which told you the story you needed to know: this wasn’t a turnaround bet. It was a “buy quality, keep it full” bet.

The Retail Apocalypse Narrative

Then came the mid-2010s drumbeat: e-commerce is killing retail. Amazon was eating everything. Mall REITs got punished, and “retail apocalypse” became a default headline.

AAT’s retail held up better than the stereotype because it wasn’t built like the malls everyone was shorting. Their properties leaned into the categories that don’t ship well in a cardboard box—and the locations people still go out of their way to visit. The mix looked more like this:

- Irreplaceable locations, including Waikiki Beach and coastal California neighborhoods

- Tenants skewed toward restaurants, fitness, personal services, and grocery—businesses that are harder to replace with a click

- Built-in traffic from tourism and affluent local populations

- Outdoor, walkable formats that match California’s year-round climate

It wasn’t that AAT was immune to retail cycles. It was that it owned the kind of retail that behaves differently when the world changes.

Life Sciences Tailwind

While retail was busy defending itself, San Diego office—especially anything near the research ecosystem—was getting a very different narrative: biotech and life sciences were turning the region into a durable demand engine.

Biocom California’s 2023 Life Science Economic Impact Report captured the momentum. It said life sciences employment in the San Diego cluster grew by 8% in 2022, with a workforce of more than 77,000 direct employees. The report also noted average annual pay of $144,000 and a regional economic impact of $57.4 billion. The point wasn’t the exact figures—it was the direction: this was becoming a pillar industry.

And it wasn’t new. The foundations were laid decades earlier, as research institutions clustered around Torrey Pines Mesa and La Jolla: UC San Diego (established in 1960), the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, the Salk Institute (1963), and Case Western’s southern branch that later became Sanford Burnham Prebys (1976). That slow accumulation of talent and research dollars is exactly the kind of long-cycle setup AAT tends to like—because it usually translates into long-cycle real estate demand.

Capital Allocation Discipline

Another thing that showed up in this era: AAT wasn’t afraid to prune. The company’s discipline wasn’t just about buying trophy assets. It was also about selling when something no longer fit the “scale and focus” equation.

In February 2025, AAT announced it would sell Del Monte Shopping Center, a premier retail destination in Monterey, California, for about $123.5 million (before closing prorations). Management framed it as a deliberate choice to focus on markets where the company could drive greater economies of scale and operational efficiency, while still staying aligned with long-term growth.

And they didn’t sit on the proceeds. The sale closed on February 25, 2025, and three days later—February 28—AAT acquired Genesee Park, a 192-unit apartment community in San Diego, for $67.9 million.

That pairing tells you a lot about the playbook: recycle capital out of good assets in less-core markets, and back into the home field where the company believes its operating advantage is strongest.

VI. COVID-19 & The Pandemic Test (2020–2021)

March 2020 was the kind of moment that doesn’t just dent a real estate portfolio—it interrogates the entire philosophy behind it. And for AAT, the pandemic hit every major line of business at once, each for a different reason.

The Hawaii Collapse

Nowhere was the shock more visible than Waikiki Beach Walk. The whole model there runs on planes landing, tourists walking, and restaurants turning tables. When travel shut down, that engine stalled almost overnight.

In the mixed-use portfolio, same-store NOI declined by 10%, driven largely by softer-than-expected occupancy and average daily rate at the Embassy Suites Waikiki. Paid occupancy dropped by 5.5% versus the prior year period. Revenue per available room (RevPAR) came in at $298, down 11.7%, and ADR fell to $381, down 5.4%. Quarterly NOI was about $2.7 million—down sharply.

Importantly, management noted the pain wasn’t unique to AAT. Results tracked similarly to other hotels in Waikiki’s comp set. Their message was consistent: this was macro pressure, not a broken asset. The near term looked ugly, but they remained confident in the hotel’s long-term fundamentals.

Office and Retail Uncertainty

At the same time, COVID opened two big questions that weren’t going away with a single quarter’s earnings report.

First: if work-from-home became permanent, what happens to office demand—especially in urban markets?

Second: if lockdowns pushed even more consumer behavior online, did physical retail take a final, fatal step toward irrelevance?

AAT’s response was less dramatic than some, but more durable: protect the balance sheet and keep relationships intact. The company entered the crisis with conservative leverage and meaningful liquidity, which bought them time when cash flows came under pressure. And rather than playing the villain during eviction moratoriums, management worked with tenants through payment plans and lease modifications.

The Recovery Validation

By 2021, the story started to turn. Vaccines rolled out. Restrictions eased. Tourism began to return to Hawaii. Retail tenants reopened and resumed paying full rent.

Office was slower—across the country, it stayed below pre-pandemic levels—but AAT’s better-located properties, particularly in life sciences-adjacent markets, held up better than commodity office.

Zooming out, the pandemic didn’t erase the company’s long-run trajectory—it interrupted it. American Assets Trust grew FFO per unit every year from 2012 through 2019. That streak broke in 2020, then the trust rebounded, reaching a record FFO per unit of $2.34 in 2022.

For investors, COVID became a real-world stress test of the “irreplaceable assets” thesis. AAT’s portfolio proved it could absorb a shock that crushed weaker landlords—especially with a diverse tenant base in supply-constrained markets. But it also made the fault lines impossible to ignore: Waikiki is sensitive to travel cycles, and office—everywhere—was walking into a new era of uncertainty.

VII. Life Sciences Boom & The Torrey Pines Transformation

If COVID was the stress test, the life sciences boom has been the tailwind—the kind of long-duration demand driver that can quietly reshape a real estate portfolio over a decade.

San Diego’s rise into “Biotech Beach” has become one of the most important secular forces working in AAT’s favor, especially across its San Diego office footprint.

Why San Diego Became a Life Sciences Hub

San Diego’s biotech cluster didn’t happen by accident. It’s the result of an unusually dense concentration of research firepower packed into a small geography.

At the center is UC San Diego—one of the nation’s leading life-science research universities and a consistent top-10 recipient of NIH funding. UCSD’s medical and bioengineering strengths, plus the proximity of UCSD Medical Center, create a steady loop: research attracts funding, funding supports discoveries, discoveries become companies, and companies need talent and space. The university also feeds the workforce pipeline, with more than 7,000 graduate students enrolled—many in STEM fields that translate directly into local biotech and pharma jobs.

The region’s culture matters too. Scott Struthers, co-founder and CEO of Crinetics Pharmaceuticals, put it simply: “My number one observation about San Diego is the culture — we're very collaborative.” He’s pointed to the “seven-mile cluster” spanning Torrey Pines, Sorrento Valley, and La Jolla, arguing that the tight geography and closeness are part of what keeps the ecosystem alive, even when capital is harder to find.

Out of that corridor has come a deep bench of companies—genomics and diagnostics leaders like Illumina and Caris Life Sciences, drug discovery and development players like Neurocrine Biosciences, Maravai LifeSciences, Halozyme Therapeutics, and Sorrento Therapeutics, plus startups across mRNA therapies, gene and cell therapies, synthetic biology, biologics manufacturing, and bioinformatics. Illumina is a useful example of the cluster’s ceiling: a La Jolla-grown genomic sequencing company that scaled into a multi-billion-dollar empire.

AAT’s Positioning

American Assets Trust isn’t a pure-play life sciences REIT. It doesn’t try to be Alexandria. But it doesn’t have to.

AAT’s advantage is adjacency. Its San Diego office portfolio sits right next to the action, and properties like Torrey Reserve Campus and La Jolla Commons can pick up demand as life sciences companies expand beyond purpose-built lab environments. Not every employee needs wet lab space. Administrative teams, finance, legal, HR, and computational work often fit just fine in high-quality traditional office—especially when it’s located where talent wants to live and work.

San Diego’s life sciences engine is also broader than biotech headlines suggest. The region is consistently recognized as a top-three life sciences market in the U.S., powered by universities and research institutions that produce both talent and technology—and keep drawing NIH funding and venture capital year after year. The ecosystem spans biotechnology, genomics, medical devices, RNA therapeutics, and pharmaceuticals, with companies pushing everything from life-saving therapeutics to early detection and next-generation medical devices.

For AAT, that matters because it supports a durable thesis: when a region becomes an innovation hub, demand for well-located, high-quality space tends to persist—even as the specific winners and losers rotate.

The Competition Challenge

Of course, this is not a quiet corner of real estate. The biggest prize in life sciences—purpose-built lab campuses—has attracted specialist capital at enormous scale.

Alexandria Real Estate is the archetype here: a life science REIT founded in 1994 that effectively pioneered the category, and built a reputation as the preeminent owner, operator, and developer of “Megacampus” ecosystems in top innovation clusters across the U.S. As of October 2025, Alexandria had a market cap of about $13 billion with 173 million shares, and as of September 2025 it reported trailing 12-month revenue of $2.98 billion.

That’s the kind of competitor that can outspend you on lab infrastructure and out-market you to the biggest venture-backed tenants.

AAT’s response has been to compete differently. Rather than chasing the most capital-intensive, specialized lab product, it leans into traditional office that can still serve life sciences tenants—especially for administrative and computational needs. The trade-off is clear: it may come with lower rent ceilings than high-end lab space. But it also typically requires less specialized buildout and can appeal to a broader tenant pool, which matters when markets turn and flexibility becomes its own form of risk management.

VIII. 2022–2024: Interest Rate Shock & The New REIT Reality

Then the macro backdrop changed again—fast.

After a decade where cheap money helped lift almost every kind of real estate, the Federal Reserve’s rapid rate hikes in 2022 and 2023 reset the rules for REITs. Higher rates don’t just make new debt more expensive. They also change what investors are willing to pay for a stream of rent that arrives over many years. The result, across the sector, was predictable: fewer transactions, softer property values, and lower REIT multiples.

AAT didn’t escape that gravity. By that point, the stock was trading at a price-to-FFO multiple of about 8.2—less than half its 10-year average of 19.4. The same “steady compounder” profile that once earned it a premium now looked different in a world where risk-free yields suddenly had teeth.

Balance Sheet Resilience

This is where the company’s long-running conservatism started to matter again.

Yes, higher rates hit everyone. But AAT’s interest burden didn’t balloon the way it did for many peers. Net interest expense rose 16%, from $53 million in 2020 to $61.4 million. Over that same period, Realty Income, Douglas Emmett, and Cousins Properties saw much bigger jumps—111%, 35%, and 64%, respectively.

Another way to say it: interest expense consumed about 51% of AAT’s operating income—meaning the company could still cover its debt costs without living on the edge. And it carried investment-grade credit ratings from the major agencies, which, in this environment, is the difference between “expensive capital” and “capital that disappears.”

The Return-to-Office Debate

But balance sheets don’t fully solve narrative—and in 2022 through 2024, the narrative that mattered most was office.

AAT’s retail and multifamily assets largely found their footing again as the economy reopened. The office portfolio, however, stayed under pressure, caught in the crosscurrent of work-from-home and tenant hesitation. That mix—rate shock plus office uncertainty—helped drive the stock’s underperformance and heightened volatility.

By November 2025, the market’s mood was still cautious. Investors weren’t just watching quarterly numbers; they were watching proof points. Could AAT keep leaning on what it does best—well-located, high-quality properties and disciplined operations—while navigating the parts of the portfolio that were slower to heal?

IX. The Competitive Landscape & What Makes AAT Different

To understand where AAT fits, it helps to line it up against the other West Coast landlords chasing the same scarce coastline—and the same tenants.

Alexandria Real Estate (ARE): The Life Sciences Giant

If AAT is “adjacent to life sciences,” Alexandria is the category.

Founded in 1994 and now an S&P 500 company, Alexandria more or less pioneered the modern life science REIT. Its calling card is the Megacampus: dense, collaborative ecosystems in top-tier innovation clusters, designed specifically for biotech and pharma tenants that need specialized lab space and want to be surrounded by talent, capital, and peers.

Alexandria also plays the game at a completely different weight class—roughly ten times AAT’s scale—with the balance sheet and platform to build purpose-built lab campuses and even invest in tenant companies.

But the flip side of being a giant is that giants have to keep feeding the machine. Scale can bring complexity, and specialization can bring concentration risk—two things AAT’s more diversified, less development-heavy approach is designed to avoid.

Kilroy Realty (KRC): West Coast Office Focus

Kilroy is closer to AAT’s world: West Coast office and mixed-use, with decades of development and operating history. It’s publicly traded, sits in the S&P MidCap 400, and has built a roster of innovation-driven tenants across technology, entertainment, digital media, and health care.

Geographically, Kilroy’s footprint overlaps heavily with AAT’s orbit—San Diego, Greater Los Angeles, the San Francisco Bay Area, the Pacific Northwest—plus Austin, Texas. But Kilroy has also been more directly exposed to the market’s post-2020 office anxiety. Short interest in its stock rose to 5.2%, a reminder of how skeptical investors have been about the entire office category.

And it wasn’t just Kilroy. Douglas Emmett—another coastal office and multifamily owner, concentrated in Los Angeles and Honolulu—saw its shares fall about 75% from the all-time high it hit in December 2019. The common theme across the peer set is simple: even great buildings can’t fully outrun a sector-wide narrative when capital markets decide they don’t like “office” anymore.

The AAT Differentiation

So what, exactly, makes AAT different? Not one silver bullet—more like a stack of advantages that show up over long holding periods.

Vertical Integration: While plenty of REITs outsource key functions, AAT runs property management, leasing, and operations in-house. That can mean tighter cost control, faster decision-making, and tenant relationships that go deeper than a third-party manager’s call sheet.

Generational Ownership: With Ernest Rady still holding roughly 30%, the time horizon is structurally longer. The company doesn’t have to optimize solely for the next quarter if that comes at the expense of the next decade.

Local Market Expertise: More than five decades focused on San Diego and other high-barrier West Coast markets builds something hard to buy: real relationships, real-time market feel, and pattern recognition across cycles.

Selective Portfolio Concentration: AAT doesn’t try to be everywhere. It concentrates in markets it knows intimately, aiming to be the best operator in a narrower lane rather than an empire builder with a national map.

The investor’s question is the obvious one: is that combination—operator DNA, patient capital, and local edge—enough to overcome what the mega-REITs have in abundance: cheaper capital, more diversification, and more sheer scale?

X. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

The Power of Patient Capital

AAT’s story is a reminder that in real estate, time is its own edge. When you hold buildings for decades, you stop thinking like a trader and start thinking like an operator. You can afford to make improvements that pay back slowly, nurture tenant relationships, and let great locations do what they do best: get more valuable as scarcity tightens.

Geographic Specialization vs. National Footprint

AAT also makes a quiet argument against being everywhere. In real estate, there are real diseconomies of scope. Knowing a market deeply—who’s building, who’s buying, which intersections are getting better, how zoning really works in practice—creates an advantage that’s hard to replicate from a corporate headquarters thousands of miles away. AAT picked a handful of high-barrier places and tried to become a native in each one.

When Vertical Integration Creates Value

Vertical integration isn’t automatically good. It works when the business rewards tight control and tight feedback loops. In AAT’s world, it tends to create value when:

- There are meaningful information gaps between owners and third-party managers

- Relationship continuity matters to tenants

- Coordination across leasing, construction, and operations is complex and high-stakes

- The operator actually has deep, in-house capability to execute

For AAT’s markets and property types, those conditions largely apply—which is why keeping the machine in-house has been more feature than burden.

Family Control Trade-offs

Founder-controlled companies always come with a trade. You give up some governance rights in exchange for strategic patience. That bargain can work—sometimes exceptionally well—when the founder has:

- Real operating skill in the core business

- Strong alignment through meaningful personal ownership

- Thoughtful succession planning

- Enough institutional oversight to deter self-dealing and keep accountability real

AAT’s structure asks investors to buy into that bet: that long-term control is a stabilizer, not an anchor.

XI. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Zooming out, you can pressure-test AAT with two classic lenses: Porter’s Five Forces (what the industry does to you) and Hamilton’s 7 Powers (what you can do to the industry).

Porter's Five Forces

Competitive Rivalry (Moderate-to-High): Real estate is crowded with capital. AAT isn’t just competing with other public REITs, but also with private equity, institutional investors, and local operators. The twist is that AAT doesn’t sit neatly in one box—it isn’t a pure office, pure retail, or pure life sciences platform—so it’s often competing deal-by-deal and lease-by-lease across multiple categories.

Threat of New Entrants (Low-to-Moderate): Anyone can raise money to buy real estate. Not everyone can win the best assets in the best West Coast submarkets, then operate them well for decades. The true barriers aren’t financial—they’re local knowledge, long-standing relationships, and the ability to acquire “irreplaceable” locations that almost never trade.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Low): The vendors that keep buildings running—construction trades, maintenance, service providers—are largely interchangeable. There’s no single supplier that can hold AAT hostage.

Bargaining Power of Buyers/Tenants (Moderate): Big, creditworthy tenants can negotiate. If you’re LPL Financial, you don’t sign a lease like a mom-and-pop does. But in supply-constrained submarkets, choice is limited. When the location is the product, the landlord has real leverage—especially for high-quality, well-located space.

Threat of Substitutes (Moderate): This is the modern shadow over the whole sector. Remote work is a substitute for office. E-commerce is a substitute for retail. But the substitution risk isn’t evenly distributed. Experiential retail, life sciences-adjacent space, and premium residential in constrained markets tend to hold up better because they’re tied to place, not convenience.

Hamilton's 7 Powers

Counter-Positioning (YES): AAT’s patient-capital posture is a genuine differentiator. Plenty of public REITs, under quarterly pressure, end up doing things that look rational in the moment but degrade the asset over time—accepting weaker tenants, deferring maintenance, or chasing growth through deals that dilute long-term value. Founder control gives AAT more freedom to trade short-term optics for long-term compounding.

Cornered Resource (YES): This is the heart of the thesis. There is no “next” Waikiki beachfront. There is no easy way to replicate a prime La Jolla campus near UCSD. When you own assets in locations that can’t be recreated, scarcity does a lot of competitive work for you.

Process Power (YES): Vertical integration isn’t just a structure; it’s an operating system. After more than five decades running leasing, property management, and development internally, AAT’s advantage lives in habits, systems, and relationships that aren’t easy for a newcomer—or a more financial, outsourced competitor—to copy quickly.

Scale Economies (Limited): This isn’t like data centers or industrial logistics where scale can meaningfully change unit economics. Bigger REITs can spread overhead and access cheaper capital, but real estate still wins and loses at the property level.

Network Effects (No): Owning more buildings doesn’t automatically make each building more valuable in the way a platform business does. AAT doesn’t get stronger because “more users” join; it gets stronger by owning better real estate and operating it better.

Switching Costs (Moderate): Tenants don’t move on a whim. Office relocations are disruptive, expensive, and risky. But switching costs aren’t a permanent lock-in—if tenants want to leave badly enough, they can.

Branding (Limited): In this business, “brand” is mostly shorthand for trust and track record. Tenants care about the property, the location, and the quality of the landlord relationship—not a consumer-facing logo.

Conclusion: If you boil it down, AAT’s edge comes from three powers that fit its personality: Cornered Resource (owning what can’t be replaced), Counter-Positioning (patient capital in a quarterly world), and Process Power (operating muscle built over decades). They’re real advantages—but they’re narrower, and more asset-specific, than the moats you see in software or consumer platforms.

XII. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Perspective

The Bull Case

At today’s price, the bull argument for AAT starts with a simple claim: you’re getting paid to wait.

As of November 2025, AAT traded at a forward P/FFO of 9.6 and offered a 7.3% dividend yield—near historic highs—with that dividend described as well-covered.

Underneath the valuation, the operating picture in the parts of the portfolio that have already “normalized” looks solid. Retail, in particular, remained essentially full—98% leased—benefiting from limited new supply and consumer demand that, so far, has held up better than the doom-loop narrative would suggest.

The broader bull thesis rests on a few pillars:

-

Asset Quality: Trophy properties across San Diego, Hawaii, and the Pacific Northwest that are hard—sometimes impossible—to replicate.

-

Life Sciences Tailwind: San Diego’s biotech engine keeps expanding, supporting demand for office in AAT’s core submarkets, especially the life sciences-adjacent parts of the portfolio.

-

Balance Sheet Strength: Conservative leverage and investment-grade ratings give the company downside protection and, importantly, the option to buy when others can’t.

-

Dividend Sustainability: A diversified coastal portfolio plus a conservative 69% payout ratio makes the stock compelling for income-focused investors.

-

Management Transition Completed: With Adam Wyll as CEO and Ernest Rady as Executive Chairman, the company presents the succession story as largely settled—less “key man risk,” more continuity.

The Bear Case

The bear case is what the market has been shouting for a while. With the stock down nearly 25% year-to-date as of November 2025, investors are effectively asking whether AAT’s mission of “superior returns” can survive a world where office demand is structurally different—and where capital is no longer cheap.

The bear thesis includes:

-

Structural Office Headwinds: Remote and hybrid work may have permanently lowered demand for office, especially in coastal markets where tenants have options and costs are high.

-

Geographic Concentration: Heavy exposure to California and Hawaii increases vulnerability to regional downturns, regulation, and natural-disaster risk.

-

Small Scale: Compared to mega-REITs, AAT has less access to capital and fewer paths to deploy it, which can limit growth and contribute to a valuation discount.

-

Hawaii Tourism Risk: The Embassy Suites Waikiki felt the shock, with RevPAR down 11.7%. Management framed the decline as near-term macro pressure rather than a reflection of long-term fundamentals—but the dependency on travel is real.

-

Governance Concerns: The dual-class structure limits minority shareholder influence, which some investors will always treat as a built-in risk.

Key Metrics to Track

If you want to track whether the bull case is winning or the bear case is right, two metrics do a lot of the work:

1. Same-Store NOI Growth: This is the cleanest read on organic performance—how the properties are doing without the noise of acquisitions and sales. Same-store cash NOI decreased 0.8% year-over-year for the three months ended September 30, 2025, and increased 0.6% year-over-year for the nine months ended September 30, 2025. Consistent positive growth suggests healthy demand and execution; persistent declines suggest something more fundamental is slipping.

2. Office Leasing Spreads: In a shaky office environment, pricing power shows up here first. AAT leased about 181,000 office square feet with average contractual rent increases of 19% on a straight-line basis and 9% on a cash basis. It also leased about 125,000 retail square feet with average contractual rent increases of 21% straight-line and 4% cash. Positive spreads are a sign that demand is still there for the product AAT owns; negative spreads would be the warning light that the market’s skepticism is becoming reality.

XIII. Recent Developments & Looking Forward

2024-2025: Leadership Transition

By 2024, the company was facing the one transition every founder-led business eventually has to navigate: what happens when the founder steps back.

On July 25, 2024, Ernest S. Rady—then Chairman and CEO—gave notice that he intended to move from CEO to Executive Chairman, effective January 1, 2025. The board appointed Adam Wyll, the company’s President and COO, to become President and CEO.

Wyll wasn’t a parachuted-in outsider. He joined the company’s predecessor in 2004 and spent two decades moving through roles across the platform, including Executive Vice President and COO from 2019 to 2021, and President and COO since 2021. His background spans commercial real estate, acquisitions and dispositions, structured finance, leasing, and corporate and securities matters. Rady framed the choice as continuity: “I am pleased to announce the appointment of Adam as the new CEO in January 2025. Adam has demonstrated exceptional leadership, a strong commitment to our mission and a deep understanding of our industry, at all levels of our organization.”

As of 2025, Rady served as Executive Chairman with an annual base salary of $600,000. Wyll stepped into the President and Chief Executive Officer role with an annual base salary of $750,000. Robert Barton continued as Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer.

Latest Financial Performance

Operationally, the story in 2025 looked like a company holding steady in some areas while still working through pressure points in others.

American Assets Trust reported Q3 FFO of $0.49 per diluted share and raised its 2025 FFO guidance to a range of $1.93–$2.01, with a midpoint of $1.97. Liquidity stood at $538.7 million. Same-store cash NOI fell 0.8% in the third quarter but was up 0.6% year-to-date.

For the nine months ended September 30, 2025, FFO decreased by $38.0 million compared to the same period in 2024. Management attributed that decline primarily to litigation income received in the first quarter of 2024, higher interest expense, a drop in retail segment contribution following the sale of Del Monte Center, and lower office occupancy.

Leasing activity remained active. In Q3 2025, the company signed 49 leases covering about 306,500 square feet of office and retail space, along with 593 multifamily apartment leases. Renewals made up most of the activity: 73% of comparable office leases, 96% of comparable retail leases, and 55% of residential leases.

The Generational Question

With Rady now in his mid-90s, the big question isn’t whether there’s a CEO. There is. It’s whether the company can preserve the founder-era operating philosophy while the next generation of leadership takes the wheel.

Rady has served as Executive Chairman since January 2025. Before that, he was Chairman and CEO from September 2015 through December 2024, and from the January 2011 IPO through September 2015 he served as Executive Chairman. He brings decades of experience in real estate management and development, and he remains an influential figure in the company’s direction.

The succession has looked orderly on paper, but investors will still watch for any change in strategy, capital allocation philosophy, or risk tolerance as the new leadership team establishes its identity.

Looking Forward: Opportunities and Risks

The next chapter for AAT is less about a single do-or-die bet and more about a handful of choices that will compound over time.

Life Sciences Expansion: Does AAT lean further into life sciences by converting some office space to lab? The upside is potentially higher rents, but the trade-off is real: heavier capital needs and more specialized requirements.

Multifamily Growth: The Genesee Park acquisition signals the company still sees opportunity in San Diego apartments. In supply-constrained coastal markets, multifamily may offer some of the cleanest risk-adjusted growth—especially when housing shortages persist.

Technology and Climate: San Diego’s growth as a technology hub beyond life sciences could support incremental office demand. At the same time, coastal real estate carries long-term climate risk, including sea level rise and extreme weather.

Market Expansion vs. Concentration: Should AAT broaden beyond its core West Coast footprint to find more growth, or double down where it believes its operating edge is strongest? The Del Monte sale points toward concentration and scale within fewer markets—but that choice can also cap how quickly the company can expand.

XIV. Epilogue & Final Reflections

The story of American Assets Trust is, in many ways, an anachronism. In an era of private equity roll-ups and REIT consolidation, a family-controlled regional operator isn’t supposed to compete. The modern playbook says scale wins: the biggest platforms get the cheapest capital, they buy the best deals, and eventually everyone else gets absorbed—or forced into the same short-term treadmill by quarterly expectations.

And yet, here AAT is.

Fifty-seven years after Ernest Rady bought a $35,000 stake in an apartment complex in El Cajon, the business he started is managing a $3.7 billion portfolio of trophy assets across the West Coast. It survived the financial crisis, rode out the retail apocalypse narrative, took the pandemic hit—especially in Waikiki—and then faced the interest rate reset that punished anything with “office” in the description.

It’s not a straight line. But it’s still standing. And in real estate, that’s often the whole game.

What Surprises

The first surprise is that patient capital still works. AAT is proof that markets don’t always, or automatically, reward the biggest balance sheet. In businesses where the edge comes from knowing a place—its zoning quirks, its tenant base, its invisible politics, its micro-neighborhoods—local expertise and relationship continuity can be a real moat. Not flashy. But durable.

The second surprise is succession. Founder-controlled companies often struggle when it’s time to hand off the keys: the founder can’t let go, the bench isn’t ready, or the culture turns into a personality cult that doesn’t survive the transition. AAT did it the boring way, which is usually the right way. Adam Wyll didn’t arrive with a glossy “transformation plan.” He spent two decades inside the machine before becoming CEO, which is exactly how you preserve a long-running operating system.

The Structural Question

A deeper question still hangs over the whole story: does the public REIT structure actually serve a company like AAT, or would it be better off private?

Public markets bring real costs—quarterly reporting, narrative management, and stock-price volatility that can detach from the underlying value of buildings. For a company that thinks in decades and is controlled by a founder with a long horizon, those frictions can feel like a tax.

But going private isn’t a button you press. It would mean buying out minority shareholders, likely at a meaningful premium, and Rady’s stake—about 30%—wouldn’t come close to funding a full take-private on its own. So the current shape of AAT—publicly traded, but still founder-influenced—may be less a perfect design than the most workable compromise.

Lessons for Operators and Investors

For operators, AAT reinforces a simple, unfashionable point: in real estate, execution compounds. Vertical integration, geographic focus, and a willingness to hold through cycles can build a platform that capital alone can’t easily replicate. It takes time to build that muscle. But once it’s there, it’s hard to copy.

For investors, AAT offers a specific kind of exposure: irreplaceable coastal real estate run by a team with real ownership and a long memory of risk. The trade-offs are just as specific: limited governance voice, a portfolio concentrated in a handful of markets, and real sensitivity to the parts of real estate that are still being repriced—especially office. If you believe in the patient-capital model and accept the governance structure, the appeal at depressed multiples is obvious. If you don’t, no dividend yield will fix that discomfort.

Why This Story Matters

AAT matters because it’s a reminder of what building can look like without financial theatrics.

Ernest Rady didn’t invent a new technology or manufacture a new consumer habit. He did something more old-school: he bought real estate in places where it’s hard to replace, operated it tightly, improved it over time, and held on through downturns that shook out weaker hands.

That doesn’t generate viral headlines. But it does create institutions.

The trunk of the car where Rady once ran the business became a headquarters overseeing billions in assets. The allergies that brought Evelyn Rady to San Diego helped seed one of the city’s landmark real estate empires. And the core thesis—buy irreplaceable assets in supply-constrained markets, then run them with patience—has stayed intact through every cycle the last half-century could throw at it.

That’s the American Assets Trust story: an overnight success, five and a half decades in the making.

XV. Further Reading & Resources

Top Resources

-

American Assets Trust Annual Reports & Investor Presentations (2011-present) - The best starting point: how management thinks, how the portfolio has changed, and what the company has actually done over time.

-

SEC S-11 Filing (2011 IPO) - The origin document for the public company: detailed history, risk factors, and the governance structure that shaped AAT’s “public, but still founder-influenced” identity.

-

Green Street Advisors Research Reports on AAT - Helpful third-party framing, including NAV work and comparisons across REIT peers.

-

San Diego Regional Economic Development Corporation Reports - Regional context on what’s driving San Diego’s growth, especially around innovation and employment trends.

-

Biocom California Life Science Economic Impact Reports - The numbers behind “Biotech Beach,” and why demand for high-quality space in San Diego has had real staying power.

-

"The REITs Book" by Ralph Block - A solid primer on how REITs work, how they’re valued, and what matters (and doesn’t) in the business model.

-

"Pioneering Portfolio Management" by David Swensen - A great lens on patient capital and long-horizon decision-making—useful context for understanding a founder-controlled platform.

-

NAREIT (National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts) Industry Data - Benchmarking, sector history, and the broader REIT landscape AAT sits within.

-

"Where Are the Customers' Yachts?" by Fred Schwed Jr. - A classic reminder of how incentives work in finance—and why “financial engineering” so often beats long-term stewardship in the short run.

-

Earnings Call Transcripts (Seeking Alpha, FactSet) - The closest thing to sitting in the room with management: how they explain performance, justify capital allocation, and frame what comes next.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music