Venus Remedies: From Financial Crisis to AMR Pioneer

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

In a sterile intensive care unit somewhere in India, a doctor faces a choice that didn’t really exist thirty years ago. The patient has a gram-negative bacterial infection. First-line antibiotics have failed. Second-line antibiotics have failed. The bacteria have learned how to neutralize almost everything the hospital can throw at them.

So the doctor reaches for the last resort: polymyxin B.

It’s a drug that can save a life and wreck a kidney in the same week. Using it isn’t just prescribing medicine. It’s making a trade. Beat the infection, but accept real odds of serious toxicity in the process.

That dilemma is the day-to-day face of antimicrobial resistance, or AMR. The World Health Organization calls it one of the greatest threats to global health. And it’s the problem that Venus Remedies, a mid-cap Indian pharma company most people have never heard of, has spent years organizing itself around.

Venus Remedies is listed on India’s National Stock Exchange as VENUSREM, with a market capitalization of around ₹978 crore. At first glance, it’s easy to bucket it with the hundreds of other Indian companies that make generic injectables for hospitals. But look closer, and Venus is something rarer: a company trying to build an innovation engine pointed directly at antibiotic resistance.

It has more than 135 patents. It holds over 1,040 marketing authorizations across 90-plus countries. And it recently earned a USFDA Qualified Infectious Disease Product designation for a next-generation polymyxin B formulation—exactly the kind of regulatory signal that says, “This is not just another commodity vial.”

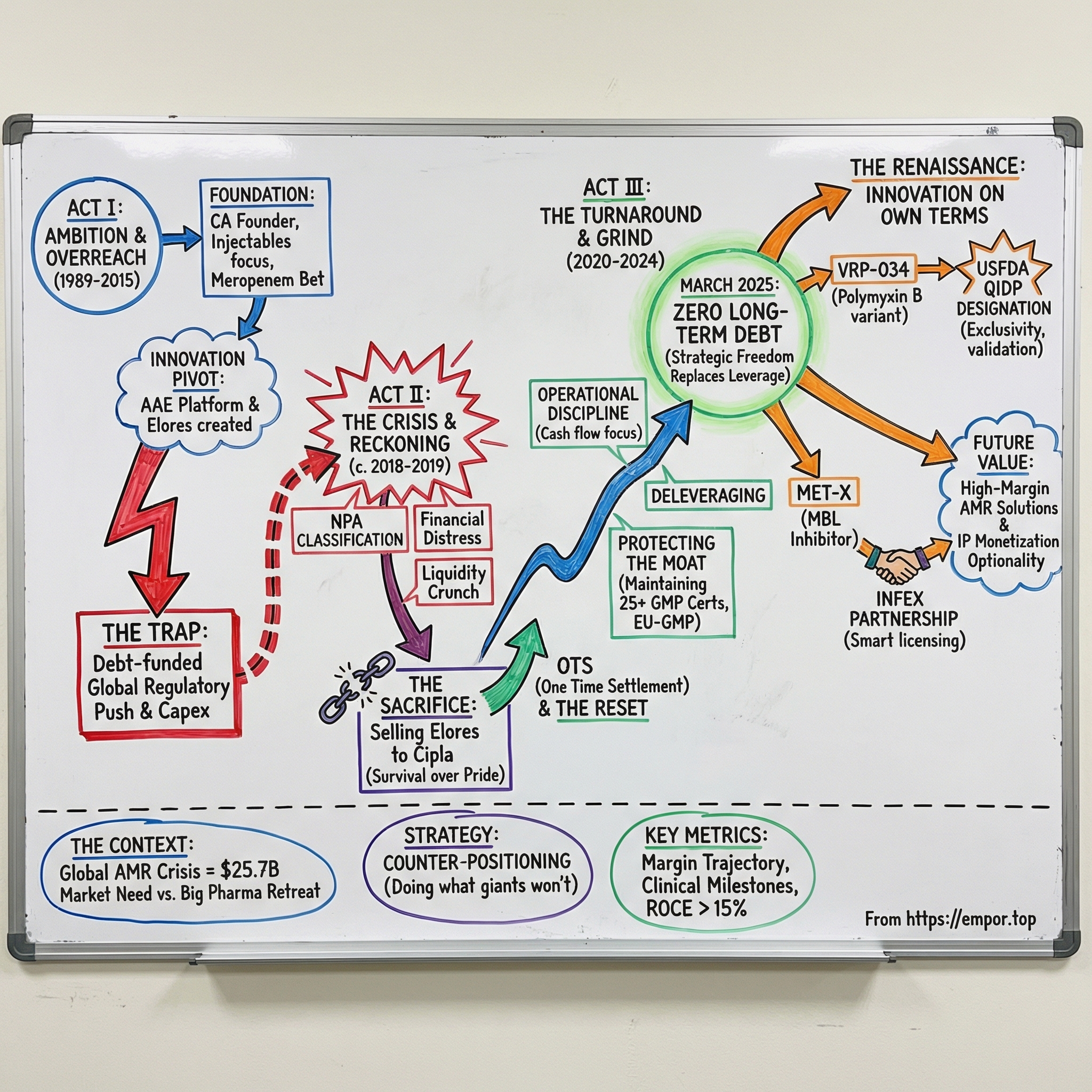

The story of Venus plays out like a three-act drama.

Act one: a chartered accountant-turned-entrepreneur builds an injectable business through the 1990s and, along the way, stumbles into serious science—antibiotic adjuvants designed to make old drugs work again.

Act two: the balance sheet breaks. Lenders classify the company’s loans as non-performing assets. Venus gets forced into a painful decision, ultimately selling its most promising drug to Cipla just to stay alive.

Act three: Venus rebuilds the business the hard way—back to zero debt, back into regulatory credibility, and into a position where it can credibly claim a seat at the AMR table right as the global market for AMR solutions marches toward an estimated $25.7 billion by 2032.

So the question driving this deep dive is simple: how does a near-bankrupt injectable manufacturer turn into a USFDA QIDP-designated innovator?

The answer runs through financial distress that forced strategic clarity, a founder willing to choose survival over pride, and a counterintuitive bet on antibiotics at the exact moment Big Pharma decided they weren’t worth the trouble.

Along the way, we’ll hit the big themes: debt restructuring and balance-sheet trauma, an R&D pivot from generics to resistance-breaking technology, the quiet power of regulatory “arbitrage” across dozens of countries, and the uncomfortable reality that AMR is both a public health crisis and a massive, still-underbuilt market opportunity.

Whether Venus ultimately converts that positioning into durable shareholder value is still an open question. But the arc—from NPA classification to QIDP designation—is already one of the more remarkable turnaround stories in Indian pharma.

II. Founding Context and India's Pharmaceutical Landscape

The Chartered Accountant Who Built a Pharma Company

Pawan Chaudhary was not the obvious candidate to build a pharmaceutical company. He trained as a chartered accountant—India’s version of a CPA, with its own level of rigor and status—and that pipeline usually leads to audit, corporate finance, or a family enterprise. It does not usually end with someone running sterile injectable plants.

But India in 1989 created unusual openings for people who could read the rules and spot the incentives. The economy was still constrained by the License Raj. Yet pharma had a structural advantage that made it one of the few industries where a newcomer could realistically build something big: India followed a process patent regime, not a product patent regime. In plain terms, companies could legally reverse-engineer a molecule and sell it, as long as they developed their own way of making it. The “what” could be the same; the “how” had to be different. That distinction powered the rise of Indian generics champions, and Chaudhary saw the same opportunity.

He started Venus Glucose Private Limited in 1989. The name was honest about the initial plan: glucose and basic IV fluids for hospitals. Not glamorous, not high science—just a product hospitals needed every day. India was expanding its hospital infrastructure, especially in cities, and it still imported more basic injectable products than you’d expect. The business case was simple and very Indian for that era: make it domestically, price it competitively, and become a reliable supplier. Import substitution was the thesis.

What separated Chaudhary from many first-generation pharma founders wasn’t the early product mix. It was how naturally he thought in terms of capital structure. As a CA, he understood fundraising, markets, and financial engineering. That skill would help Venus scale. And later, when confidence turned into leverage, it would become a source of real danger.

The Injectable Opportunity

Injectables sit in a strange, valuable corner of pharma. They’re far harder to make than pills because sterility isn’t a feature—it’s the entire product. A contaminated tablet is a quality problem. A contaminated injectable can be fatal.

That reality creates higher barriers to entry. You need clean rooms with tightly controlled air, water-for-injection systems, aseptic filling lines, and quality labs that can run sterility and endotoxin testing day in and day out. The capex is heavy. The processes are unforgiving. And one failure—one contamination event, one bad inspection—can shut a line for months and damage a reputation for years.

Chaudhary leaned into that difficulty instead of avoiding it. Through the 1990s, as the post-1991 liberalization wave changed Indian business, Venus moved beyond basic fluids into more complex injectables. In 1994, the company went public and raised money to expand. At that point, Venus was still a straightforward story: a generic injectables manufacturer focused on execution—manufacturing discipline, regulatory compliance, and distribution. There was no big R&D narrative yet.

But the listing was a tell. Chaudhary wasn’t building a small regional supplier financed only by internal cash flows. He wanted the ability to fund ambition.

The Meropenem Bet

The decision that shaped Venus for the next two decades was its commitment to carbapenems—especially meropenem.

Here’s why that matters. Antibiotics function like a ladder doctors climb as bacteria adapt. Start with older, cheaper drugs for routine infections. When those fail, escalate to broader-spectrum options. Carbapenems live near the top—powerful “big gun” antibiotics typically reserved for severe, hospital-acquired infections that have already beaten the earlier lines of defense.

Meropenem became the workhorse in that category. It’s a staple in ICUs worldwide for serious infections—complicated urinary tract infections, bloodstream sepsis, ventilator-associated pneumonia. When a hospital needs something strong, meropenem is often where they land.

Building a business around meropenem was a bet on two forces. First, that India’s expanding healthcare system—more hospitals, more surgeries, more ICU beds—would inevitably produce more severe infections that require hospital-grade antibiotics. Second, that resistance would keep spreading, pushing more patients up the ladder to carbapenems. Both bets were right. And the second one, the slow march of resistance, would eventually become the backdrop for Venus’s near-death experience.

Venus invested heavily in manufacturing capacity and became one of India’s largest meropenem producers, with facilities in Panchkula and Baddi in Himachal Pradesh, plus a German subsidiary, Venus Pharma GmbH, in Werne. That footprint mattered. It wasn’t just about volume—it was about credibility and access. A presence in Germany gave Venus a base inside the European Union, a path toward meeting EU-GMP expectations, and a way into markets that many similarly sized Indian companies never reach. For a company of Venus’s scale, it was an unusually aggressive move.

By the early 2000s, Venus had an identity: an Indian injectable manufacturer with a serious carbapenem franchise, growing exports, and a founder starting to look beyond the standard generic playbook. The question hanging over the business wasn’t whether the ambition was real.

It was whether Venus’s resources—and its balance sheet—could keep up with it.

III. The Innovation Inflection: Elores and the AAE Platform

A Pharmacist's Insight, A Chemist's Obsession

Venus didn’t wake up one morning and decide to become an innovator. The shift crept in, driven by an uncomfortable reality the company could see up close: the antibiotics it was manufacturing were gradually losing their edge.

In Indian hospitals, resistance patterns were getting uglier every year. The bacteria were adapting faster than new drugs were arriving. Even meropenem—Venus’s flagship “big gun”—was starting to run into organisms that could break it down. Carbapenem-resistant infections weren’t an abstract public health headline anymore. They were showing up in wards, in cultures, in outcomes.

For Venus, that was both a clinical tragedy and a business problem. If the drugs you make stop working, the whole machine eventually grinds down. The obvious industry response—discover a brand-new antibiotic—wasn’t realistic at Venus’s scale. Novel antibiotic programs take a decade-plus, cost enormous sums, and most candidates never make it through clinical development.

So Venus took a different path. Out of necessity, it built what it called the Antibiotic Adjuvant Entity platform, or AAE. The premise was straightforward: instead of inventing a new antibiotic, restore the power of existing ones by pairing them with compounds that disarm resistance.

Here’s the intuition. The antibiotic is the battering ram. The bacteria’s resistance mechanisms are the fortress—enzymes, membranes, and biochemical tricks that blunt the attack. The adjuvant isn’t the weapon. It’s the team that sabotages the defenses so the weapon can work again. The adjuvant doesn’t have to kill the bacteria directly; it just has to take away the bacteria’s advantage.

It was a clever sidestep around the economics of drug discovery: take molecules doctors already understand, that factories already make at scale, and make them useful again.

Elores: The Breakthrough Product

The first breakout product from that idea was Elores, a three-part combination: ceftriaxone, sulbactam, and EDTA.

Ceftriaxone is the familiar, widely used third-generation cephalosporin—the main antibiotic doing the killing. Sulbactam is a beta-lactamase inhibitor, designed to block one of the most common bacterial enzymes used to dismantle beta-lactam antibiotics. EDTA adds another layer: it disrupts bacterial defenses further, including by binding the metal ions some resistance enzymes rely on and destabilizing the bacterial cell membrane.

Put together, the formulation wasn’t just “stronger.” In clinical settings, it could treat infections caused by bacteria that had become resistant to ceftriaxone on its own. For certain patients, that translated into something stark: the difference between having a viable option and having none.

Venus patented the formulation and kept going, building an intellectual property portfolio that eventually reached more than 135 patents globally. The work ran through the Venus Medicine Research Centre, the company’s dedicated R&D arm, which pushed the AAE concept across other antibiotic classes and resistance pathways.

The Global Regulatory Push and Its Cost

Venus didn’t stop at patents. It went after approvals—aggressively.

By the mid-2010s, the company had accumulated more than 1,040 marketing authorizations across 90-plus countries. Each one meant dossiers, stability data, audits, local requirements, and endless regulatory back-and-forth. For a company whose revenue was still in the low hundreds of crores, that footprint was unusually ambitious.

The rationale was sound. Antibiotics are global. AMR is global. And many of the regions getting hit hardest—parts of Africa, Southeast Asia, Latin America, the Middle East—also needed affordable solutions fast. Each authorization was a door Venus could open later, when its commercial reach caught up. It was regulatory groundwork laid in advance.

But this is where the story starts to tighten.

All that innovation and regulatory expansion sat on a balance sheet that was steadily weakening. Funding R&D, keeping sterile injectable facilities running across three countries, building regulatory teams, filing patents around the world, and competing in a low-margin generics business at the same time required more cash than the core business reliably threw off. Venus was borrowing to build its future—and the debt was rising faster than the innovation was turning into cash.

The AAE platform was real. Elores worked. The need was obvious.

The problem was the scaffolding underneath it. Venus was trying to operate like a company several sizes larger—on a balance sheet that was running out of oxygen. And once that happens, even great science doesn’t buy you time.

IV. Crisis Point: Financial Distress and Near-Death Experience

The Reckoning

By fiscal year 2018–19, Venus Remedies could no longer outrun its balance sheet. The company’s own filings later described the situation as “severe financial stress,” the kind of polished, understated phrase that usually means the walls are already on fire.

For years, Venus had been trying to do two expensive things at once: run a capital-intensive sterile injectables business and fund a global innovation-and-regulatory push. That ambition was real. But the funding model was increasingly borrowed money. Debt swelled, interest began to crowd out operating profits, and working capital tightened as receivables stretched and obligations came due faster than cash came in.

The pressure built across multiple public-sector banks—State Bank of India, Punjab National Bank, and Canara Bank. Then came the three letters that can turn a struggling company into a pariah overnight: NPA. Non-Performing Asset.

In India, NPA classification isn’t just an accounting label. It’s a chain reaction. Fresh credit dries up. Vendors shorten terms or demand cash upfront. Customers—especially government hospitals buying through tenders—start to worry about continuity of supply. Employees read the headlines and quietly update their resumes. The stock price, already weak, takes another hit as the market realizes this isn’t a temporary stumble.

And the spiral feeds itself.

For Pawan Chaudhary, this was the nightmare scenario. He’d spent three decades building Venus from a basic glucose business into a global injectables player with a real scientific edge. Elores worked. The patents were real. The authorizations existed. But science without solvency isn’t a moat—it’s an auction catalog waiting to happen.

The Cipla Deal: Selling the Crown Jewel

So Venus did the thing founders swear they’ll never do until they have no choice: it sold its crown jewel.

In 2019, Venus sold Elores to Cipla, one of India’s largest pharmaceutical companies, with annual revenue north of ₹15,000 crore. The full deal terms weren’t publicly disclosed, but the structure included an upfront payment plus milestones, with a final tranche of roughly ₹11 crore received in later years.

For Cipla, it was clean and strategic: a validated anti-infective with existing data and a regulatory footprint, acquired from a distressed seller. Cipla had everything Venus lacked in that moment—scale, a hospital sales force, marketing muscle, and the balance sheet to keep investing.

For Venus, it was much simpler: cash now, or chaos later.

Keeping Elores would have meant funding ongoing commercialization, distribution, and further development at the exact moment the company was struggling to service debt and keep manufacturing running. Selling it meant giving up the product that best proved Venus wasn’t just another generic injectable player. But it also meant buying time.

Did Venus leave value on the table? Almost certainly. Distress sales are designed to do that. When you negotiate with your back against the wall, you don’t get paid for the full future—you get paid for the immediate rescue. But the real comparison isn’t “fair value” versus “low value.” It’s “low value” versus “no deal,” followed by deeper distress and potentially a forced breakup of the whole company.

Elores wasn’t sold because it was the best deal. It was sold because it was the only deal that kept Venus alive.

One Time Settlement: The Reset

With the Cipla proceeds and a blunt acceptance that the balance sheet had to be rebuilt, Venus moved to the next step: One Time Settlement negotiations with its lenders.

OTS is the Indian banking system’s off-ramp for bad loans. The borrower and the bank agree on a settlement amount—typically less than the full dues—and once it’s paid, the account is resolved and the NPA tag can be removed. It’s imperfect and often stigmatized. Banks take haircuts, and borrowers swallow pride. But it’s usually better than the alternative: drawn-out insolvency proceedings, years of uncertainty, and assets sold at fire-sale prices.

The specific settlement terms with SBI, PNB, and Canara Bank weren’t fully disclosed. But the outcome shows up clearly in what came next: Venus exited NPA classification, the relationships were reset, and the company began the slow work of earning back credibility—first with banks, then with suppliers, then with the market.

The deeper change was internal. Companies that survive near-death don’t come out the same. Venus learned the lesson in the harshest possible way: debt kills optionality. Borrowing doesn’t just add risk; it hands control to creditors who won’t care about your patents or your pipeline when the numbers don’t work. They care about repayment.

The Venus that emerged from OTS wasn’t only financially restructured. It was rewired. The posture shifted from aggressive, debt-fueled expansion to something far more conservative and durable: protect cash, shorten cycles, rebuild trust, and earn the right to take risks again—later, on better terms.

V. The Turnaround: Operational Excellence and Balance Sheet Repair

The Grinding Years

From 2020 to 2023, Venus Remedies didn’t get a neat “comeback moment.” No splashy acquisitions. No heroic product launches. No victory lap.

It was just work.

Collect receivables. Tighten inventory. Control costs. Keep the plants humming. Keep shipments moving. Pay down what you owe. Then do it again next quarter.

This is the part of a turnaround that rarely makes it into the highlight reel, even though it’s the part that decides whether the company actually survives. Crisis moves are visible: sell an asset, negotiate with banks, restructure. Recovery is quieter and harder. It’s years of saying no—no to risky growth, no to vanity projects, no to the old habits that got you in trouble.

Venus operated like a company that had learned the lesson the painful way: cash flow isn’t a KPI. It’s oxygen. Management stayed focused on what they could control: better execution inside the plants, tighter working-capital discipline, and protecting the regulatory standing that kept the export engine alive. Free cash flow didn’t get reinvested into big new bets. It went where it had to go first—toward reducing debt.

Exports mattered even more in this phase than they had before. Selling across 90-plus countries helped smooth out the inevitable bumps in any single market. If domestic procurement slowed, demand elsewhere could keep volumes steady. And the company’s 11 overseas marketing offices weren’t just “presence.” They were infrastructure—local relationships and on-the-ground commercial capability that made the export book more resilient.

The Regulatory Moat Deepens

What Venus chose not to cut during recovery is just as important as what it did cut.

When money is tight, the instinct is to simplify: fewer markets, fewer jurisdictions, fewer compliance costs. Venus leaned the other way. It kept investing in manufacturing quality and regulatory certifications even as it worked through the aftermath of its balance-sheet crisis.

By 2025, Venus had built up more than 25 GMP certifications from regulators around the world, including WHO-GDP, SAHPRA in South Africa, Australia’s TGA, Colombia’s INVIMA, and UNICEF pre-qualification—credentials that open doors to institutional procurement and export-heavy growth.

The EU-GMP renewal through Infarmed in 2025 was a particularly meaningful stamp. In practical terms, EU-GMP isn’t a badge you hang on a website. It’s a passport that makes Europe accessible—and it signals to other markets that your systems can withstand some of the toughest scrutiny in pharma.

In sterile injectables, that scrutiny is the moat. These certifications take years to earn and constant discipline to keep. Regulators don’t just review outcomes; they inspect processes. They walk the floors, interrogate documentation, test your quality systems, and revisit you later to make sure you didn’t slip. The real asset isn’t the certificate itself—it’s the organizational muscle that can repeatedly pass those inspections.

For a company of Venus’s size, the sheer density of certifications was striking. And it created a kind of asymmetric advantage: plenty of manufacturers can compete on price inside India, but far fewer can credibly supply regulated and institutional markets abroad. Venus could.

The Financial Trajectory

The financials during this period weren’t a rocket ship. They were a staircase.

In FY2023, Venus posted net margins of 4.8% and return on equity of 5.8%—not the profile of a high-quality pharma compounder, but a real improvement for a business that had been fighting for survival not long before. In FY2024, revenue reached ₹613 crore and net margins nudged up to 5.3%, the kind of incremental progress that comes from better execution and a slow shift away from the most commoditized parts of the portfolio.

Then FY2025 made the direction unmistakable. Net margins rose to 7.0%. ROE improved to 8.1%. ROCE reached 12.8%. Net profit jumped 59.1% year-over-year. Venus still wasn’t posting the kind of mid-teens returns that define India’s best pharma businesses, but the company was clearly moving from recovery to momentum.

And the most important number wasn’t a margin at all.

By March 2025, Venus Remedies had zero long-term debt.

For a company that had worn the NPA label only a few years earlier, that’s not just balance-sheet repair. It’s a change in what the company is allowed to do next. No looming covenants. No interest burden dictating strategy. No constant fear that one bad quarter could start the spiral again.

Most importantly, it meant Venus had something it hadn’t had in a long time: the freedom to invest in R&D on its own terms.

VI. Current Management and Governance

The Architect Who Survived

Pawan Chaudhary is still the center of gravity at Venus Remedies. He remains Chairman and Managing Director, and after everything the company went through, that continuity matters. Venus didn’t stumble into a zero-debt balance sheet by accident—it chased it deliberately. And it’s hard not to read that as autobiography: Chaudhary saw what leverage does when cash gets tight, and he built the post-crisis Venus to make sure the company never ends up trapped like that again.

What’s notable is how hands-on he appears to be. Based on public statements and company communications, Chaudhary doesn’t operate like a ceremonial chairman who signs off on slide decks. He’s closely tied to the levers that determine whether Venus stays a commodity injectables player or becomes something more: R&D direction, regulatory strategy, and the long, grinding work of building a global footprint market by market.

He’s also spoken about AMR with a conviction that comes across as more than positioning. Venus sells anti-infectives, yes, but he talks like someone who has internalized the stakes—like the fight against antibiotic resistance is a mission the company was built to pursue, not just a convenient growth narrative.

In Indian mid-cap pharma, founder-central leadership is both asset and risk. The upside is consistency and patience—two qualities you need to keep investing long enough to get something like a QIDP designation. The downside is concentration. When too much runs through one person, the organization can slow down at exactly the moments it needs speed, and it becomes more exposed to the founder’s judgment, bandwidth, and health.

The Next Generation and Professional Management

Manu Chaudhary serves as Joint Managing Director, bringing the next generation into the core leadership seat. For any family-run business, this is the moment that quietly determines the next twenty years. Founder-to-second-generation transitions are notoriously difficult, often because the founder’s edge—instincts formed under pressure, risk appetite, hard-earned pattern recognition—doesn’t transfer cleanly. Whether Venus can make this handoff without losing momentum will be one of the defining questions of the next decade.

Alongside that, Venus has senior leadership roles filled by Peeyush Jain as Deputy Managing Director and Ashutosh Jain as Executive Director. The overall setup is familiar in India: founder at the top, family continuity in key roles, and experienced professionals supporting execution. For investors, the issue isn’t whether that structure is “good” or “bad” in theory—it’s whether it produces accountability, attracts talent, and keeps decision-making resilient as the company scales and its innovation bets get bigger.

Ownership Structure

Promoter shareholding is 41.76%. The largest single holding, 17.21%, sits with Sunev Pharma Solutions, the promoter entity. “Sunev” is “Venus” spelled backwards—a classic Indian promoter-company flourish that says more about identity than strategy.

The more important signal is this: none of the promoter shares are pledged. In Indian equities, pledged shares are one of the clearest early-warning signs of stress—promoters borrowing against their stake, then getting hit with margin calls when prices fall, triggering forced selling and a vicious downward spiral. Venus having zero pledges fits the company’s post-crisis posture: the equity is not being used as a private credit line. After the NPA chapter, that’s not just neat governance. It’s a statement of intent.

Non-promoters hold 55.63%, which is meaningful. Institutional trust, once broken, doesn’t come back quickly. It returns quarter by quarter, after consistent execution and fewer unpleasant surprises. A public float this large suggests the turnaround has become credible beyond a retail narrative—and that the market, at least in part, believes Venus is operating like a different company than it was in the distress years.

VII. The Renaissance: R&D Pipeline and Innovation Resurgence

VRP-034: The USFDA Breakthrough

If selling Elores was the moment Venus chose survival, the USFDA’s QIDP designation for VRP-034 in April 2025 was the moment it earned the right to talk about a comeback.

To see why, you have to start with polymyxin B—and the brutal bargain it represents in an ICU.

Polymyxin B is an old antibiotic, first discovered in the late 1940s. For years it sat on the sidelines because the side effects were simply too severe, especially nephrotoxicity: kidney damage. The reason is almost painfully direct. Polymyxin B kills gram-negative bacteria by attacking their cell membranes—basically tearing holes in the barrier that keeps the cell alive. That same membrane-disrupting behavior is also what makes it dangerous to human kidney cells. The thing that makes it powerful is the thing that makes it risky.

Then antimicrobial resistance pushed medicine into a corner. As multidrug-resistant gram-negative infections became more common through the 2000s and 2010s, polymyxin B returned as a “last resort” option. When pathogens like Acinetobacter baumannii or Klebsiella pneumoniae have learned to shrug off nearly everything else, polymyxin B is often what’s left. And clinicians use it knowing the tradeoff: the drug might save the patient from the infection, but it can also permanently injure the kidneys, sometimes to the point of dialysis. It’s not a choice doctors want. It’s a choice they’re forced into.

VRP-034 is Venus’s attempt to change that equation. It’s a supramolecular cationic formulation of polymyxin B—essentially a redesigned formulation approach meant to retain the antibiotic’s killing power while reducing the damage to kidney cells.

The company’s proprietary Renal Guard technology was validated using kidney-on-a-chip models, lab systems designed to better mimic human kidney function than traditional cell cultures or animal testing. The point isn’t the novelty of the hardware. It’s what it enables: a more realistic read on toxicity, earlier in development, using human kidney cells in a controlled environment.

In preclinical testing, Venus reported a 70% reduction in nephrotoxicity compared to marketed polymyxin B. If that kind of reduction holds up in humans—which is a big and important “if”—it wouldn’t be a marginal improvement. It would change how aggressively and how early clinicians could consider polymyxin B for resistant infections, without feeling like they’re gambling a patient’s kidneys every time.

The USFDA’s QIDP designation is the external validation here. QIDP—Qualified Infectious Disease Product—is granted under the GAIN Act (Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now), which was designed to revive antibiotic development by making the economics less punishing. With QIDP, VRP-034 becomes eligible for priority review, fast-track status, and an additional five years of market exclusivity on top of standard protections. For a company of Venus’s size, that added exclusivity isn’t a footnote. It’s the difference between “great science” and “financeable science.”

And there’s a second layer to the significance: Venus is keeping the IP this time. Elores taught the company what distress does to negotiating power—when you’re forced to sell, someone else captures the upside. Coming into 2025 with a repaired balance sheet and improving cash flows, Venus had the ability to fund development without immediately auctioning off its best asset. The contrast isn’t subtle. It’s the point.

MET-X: The Infex Partnership

Just two months earlier, in February 2025, Venus signed an exclusive licensing agreement with Infex Therapeutics, a UK-based clinical-stage company, for a molecule called MET-X.

MET-X is a metallo-beta-lactamase (MBL) inhibitor. In plain terms, it targets one of the nastiest tricks bacteria use to defeat carbapenems like meropenem. MBL enzymes break down the antibiotic before it can work—molecular scissors that cut the drug apart on arrival. In hospitals, MBL-producing pathogens are feared because they can be resistant to an enormous swath of the antibiotic arsenal.

MET-X is designed to inhibit those enzymes. Block the scissors, and you give the antibiotic a chance to do its job again.

Strategically, the fit is almost too perfect. Venus is one of India’s largest meropenem manufacturers. Pair MET-X with meropenem, and the company isn’t just selling the “big gun”—it’s working on the add-on that helps the big gun keep working as resistance spreads. It’s the same underlying logic as the AAE platform: don’t rely on a brand-new antibiotic to save the day; extend and restore the value of the ones the world already depends on.

The development plan starts with a Phase I study of MET-X in combination with meropenem, then moves into Phase II and Phase III trials, initially targeting complicated urinary tract infections. This is still drug development—long timelines, high failure rates, and no guarantees. But Venus brings something many small innovation programs don’t: manufacturing capability, hospital-channel familiarity, regulatory credibility, and an export footprint built over years.

The deal also signals something about Venus itself. Not long ago, the company was struggling to keep lenders at bay. By early 2025, it was signing international licensing agreements and committing to multi-stage clinical development from a position of choice, not desperation. That’s what a turnaround looks like when it starts to compound.

The Manufacturing Foundation

Behind both VRP-034 and MET-X is the base Venus spent decades building: manufacturing.

The company operates facilities in Panchkula and Baddi in India, along with its German subsidiary in Werne. That footprint isn’t just historical sprawl. It’s a way to operate across regulatory environments and to use each geography as a platform for the markets around it.

Just as importantly, Venus has vertical integration—from API capabilities through to finished formulation. In sterile injectables, where consistency and contamination control are existential, that control matters. It strengthens supply reliability, cost discipline, and quality outcomes, and it supports the kind of stringent regulatory certifications Venus has worked so hard to earn and maintain.

In other words: the innovation story only works if the execution engine underneath it is real. For Venus, that execution engine is the part they’ve been building since the 1990s—and the part they were forced to harden during the turnaround years.

VIII. Hidden Businesses and High-Growth Segments

The Core: Anti-Infectives

For all the excitement around QIDP designations and next-gen formulations, Venus Remedies is still, day to day, a hospital anti-infectives company.

Meropenem and other carbapenems. Cephalosporins. The unglamorous, high-volume vials that ICUs and wards rely on. This is the machine that produces recurring revenue—sold in India through direct channels and, abroad, through distributors, institutional buyers, and government tenders across 90-plus countries.

It’s also a business with commodity physics. Lots of manufacturers can make broadly similar molecules. Procurement teams are trained to be price-sensitive. Tenders often push everyone toward the lowest compliant bid, which means margins are always under attack from somebody willing to go a little lower.

And yet, Venus isn’t a pure price-taker. The certifications and regulatory footprint it kept alive through the turnaround years matter here. A meropenem vial backed by EU-GMP and WHO-GDP systems can enter markets that a “domestic-only” manufacturer simply can’t. Sometimes that access translates into better pricing; more often, it translates into something just as valuable: stable demand and a wider set of doors to knock on when one market gets tough.

This core may be mature, but it’s the cash-flow base. Without it, there is no pipeline story.

The Emerging Story: AMR Innovation Pipeline

VRP-034 and MET-X are where the upside lives—and the market context explains why Venus is getting a second look.

The global market for antimicrobial resistance solutions is projected to reach $25.7 billion by 2032, growing at about 8.2% annually. For Venus, the more interesting detail is where that growth is expected to show up fastest: Asia-Pacific, with some estimates putting regional growth far higher through 2032.

And India sits right in the blast radius. It accounts for over 40% of global antibiotic consumption and has some of the highest resistance rates in the world. That’s a grim statistic for public health. But for a company building AMR products, it also means the “home market” is not hypothetical. The need is present, urgent, and growing.

Policy momentum is starting to line up with that need. India’s National AMR Action Plan, WHO partnerships, and Venus’s participation in the UN Global Compact all point to rising attention and, over time, more institutional support. Abroad, the US GAIN Act is already shaping incentives through mechanisms like QIDP, while countries like the UK and Sweden have been piloting subscription-style procurement models to make antibiotic development economically viable. Add in efforts like the Global AMR R&D Hub, and you get something AMR has historically lacked: a policy framework that’s trying to meet the science halfway.

AMR is one of the rare corners of healthcare where the medical necessity is obvious, the commercial opportunity is real, and governments are actively experimenting with ways to make the business model work.

Beyond Antibiotics: Oncology and Specialty Injectables

Venus has also been quietly building a second growth vector: oncology injectables.

This is a different game than commodity antibiotics. The regulatory hurdles are higher, the manufacturing demands are less forgiving, and the products are more differentiated. The payoff is that oncology tends to support better margins and a more favorable pricing environment—especially compared to antibiotics, where stewardship pressures effectively tell you, “Use this sparingly,” even when the drug is valuable.

Venus has been leaning on its EU-GMP-certified capabilities to play here, while also maintaining portfolios in pain management, wound care, and neurology. In total, the company has more than 180 formulations globally. It doesn’t publicly break down revenue by therapeutic area, but the strategic logic is clear: diversify the mix so the entire company isn’t hostage to one drug class, one tender cycle, or one pricing war.

The Hidden Asset: Intellectual Property

Then there’s the asset that doesn’t show up cleanly on the balance sheet: Venus’s patent portfolio.

The company has over 135 patents globally. But under Indian accounting standards, internally developed IP usually gets expensed as it’s created. So the balance sheet doesn’t reflect the economic value of the patents that come out the other end. A patent that could one day throw off meaningful licensing income can still appear on the books as basically nothing.

The Elores sale to Cipla proved that Venus’s IP can be monetized in the real world. And the QIDP designation for VRP-034 suggests the pipeline may contain more assets with that kind of commercial weight.

The key difference now is leverage—strategic leverage, not financial leverage. Venus no longer has to sell innovation under duress. It can choose: out-license from a position of strength, partner and co-develop as it did with MET-X, or push commercialization itself where it has the capabilities. That flexibility is what the patents really represent.

Optionality is easy to say. In Venus’s case, it’s unusually literal.

IX. Competitive Landscape and Market Positioning

David Among Goliaths

To understand where Venus fits, start with scale. Sun Pharma is in a different universe. Cipla and Dr. Reddy’s are, too. Venus Remedies, by comparison, is a mid-cap company with revenue measured in the hundreds of crores, not the tens of thousands.

In pharma, that gap isn’t cosmetic. Scale buys procurement leverage, a larger hospital sales force, and the ability to fund R&D without having to justify every rupee against next quarter’s cash flow. A company like Sun can outspend Venus on research many times over. Cipla can show up in hospitals across India with a commercial engine Venus simply can’t replicate.

So Venus’s strategy can’t be “go broader.” It has to be “go narrower.”

Venus isn’t trying to compete with the giants across their full portfolios. It’s trying to be unusually strong in a specific lane: injectable anti-infectives, and especially the parts of that lane that intersect with antimicrobial resistance. While the big Indian players have built their growth stories around respiratory, oncology, dermatology, biosimilars, and complex US generics, AMR innovation has rarely been anyone’s headline priority. That creates an opening. Not because it’s easy—but because it’s hard, messy, and, for most large companies, strategically optional.

Venus is leaning into what others have treated as non-core. That’s the bet: become the specialist in the category everyone agrees is important, but few are willing to build around.

The Cipla relationship shows how complicated that can get. Cipla bought Elores from Venus—meaning it’s both a validator of Venus’s science and, in anti-infectives, a direct competitor. In pharma, this “partner and rival” dynamic is common. For the smaller company, it’s also uncomfortable. You’re proving your value to a giant that can, in other parts of the market, outmuscle you.

The Big Pharma Retreat

The most important competitive dynamic for Venus isn’t just in India. It’s global—and it’s been playing out quietly in the portfolios of multinational giants.

Over the past couple of decades, Big Pharma has steadily deprioritized antibiotics. The logic is cold but consistent: an antibiotic can cost about as much to develop as any other new drug, but it usually can’t earn like one. Cancer and diabetes therapies can generate years of recurring revenue because patients take them continuously. Antibiotics are short-course by design, and stewardship programs actively push doctors to use new ones sparingly to slow resistance. Even when an antibiotic works, the market often punishes it for being used responsibly.

That’s not theoretical. Several companies that brought new antibiotics to market still ended up in bankruptcy or distress soon after, because approval didn’t translate into a sustainable commercial outcome.

This is the paradox Venus is trying to turn into an advantage: some of the drugs the world most urgently needs are the ones the largest, best-funded companies are least incentivized to build. That leaves a gap—scientific, regulatory, and commercial—for smaller, more focused players to step into.

Venus’s claim is that, at its scale, with its manufacturing base and AMR-focused pipeline, that gap isn’t just a moral mission. It’s a strategy.

X. Strategic Framework Analysis

Porter's Five Forces

Venus is really two businesses living under one ticker, and the competitive dynamics look completely different depending on which one you’re looking at.

On the generic injectables side, the threat of new entrants is moderate. Sterile manufacturing is hard and heavily regulated, but it isn’t mythical—India has produced hundreds of capable manufacturers who’ve figured out how to clear the capex and compliance hurdles. The AMR innovation side is a different species. Here, the barrier isn’t just building a plant. It’s years of R&D, specialized scientific talent, and the stamina to navigate global regulators while betting on a market Big Pharma has largely written off as economically unattractive.

Supplier power, by contrast, stays low across both worlds. India’s chemical ecosystem gives manufacturers plenty of sourcing options for APIs, and Venus reduces dependency further through backward integration into API manufacturing.

Buyer power is where things get interesting. For standard hospital injectables, it’s high. Hospitals and government procurement agencies—especially in tender systems—are trained to push price down to the lowest compliant bid. But for a truly differentiated AMR product, that equation changes fast. When the alternative is “there isn’t another drug,” the negotiation stops looking like procurement and starts looking like triage. In those moments, pricing power shifts toward the manufacturer because the buyer’s real leverage—choice—disappears.

Substitutes and rivalry follow the same split. In generics, substitutes are everywhere and rivalry is relentless. In AMR innovation, substitutes are scarce by definition, and competitive intensity is far lower—especially in India, where there simply aren’t many scaled players building in this lane.

Hamilton's Seven Powers

Through Hamilton Helmer’s lens, Venus’s clearest power is counter-positioning: incumbents can’t—or won’t—copy the challenger because it breaks their model.

Big Pharma doesn’t misunderstand AMR. It understands it perfectly. It has the labs, the regulatory teams, and the balance sheets to develop antibiotics. But doing so means diverting attention from chronic therapies that generate far higher returns and far more predictable revenue. For any one company, staying away is rational. For the world, it’s disastrous.

For Venus, that collective retreat creates a vacuum. Each year the giants stay out, Venus gets more time to build real assets: patents, regulatory credibility, clinical milestones, and manufacturing readiness. And those assets don’t just help Venus compete today—they make the company harder to copy if the big players ever decide to come back.

Other powers show up, but more lightly. Scale economies are weak because Venus can’t out-scale companies that are an order of magnitude larger. Network effects aren’t really a thing in injectables. Switching costs are moderate: hospitals don’t change suppliers casually, and formulary inclusion plus qualification processes create friction, but tenders can reset the playing field. Branding isn’t consumer-facing, yet it matters in a B2B, institution-driven market—signals like QIDP designation and GMP certifications can carry more weight than any sales pitch.

Venus’s patent portfolio and Renal Guard technology look like a cornered resource: not unassailable, but meaningfully differentiated. And process power—the muscle memory of running regulated sterile plants and maintaining 25-plus certifications—is real, even if a deep-pocketed competitor could replicate it with enough time and commitment.

It all rolls up to the same conclusion: the dominant power here is counter-positioning. Venus is building value in the space others walked away from, and the reasons they walked away haven’t changed.

XI. Capital Deployment and Strategic Direction

An Organic Growth Story

Venus Remedies doesn’t have a long list of acquisitions in its back pocket. It was built the slower way—through internal investment, facility build-outs, regulatory work, and R&D done in-house. The biggest corporate transaction in its modern history wasn’t a splashy deal to expand. It was the Elores sale to Cipla: a divestiture made under pressure, meant to keep the company alive, not to redefine it.

That organic path comes with real tradeoffs. On the plus side, Venus avoided the classic M&A landmines—overpaying, messy integration, culture clashes, and debt-funded dealmaking that can undo years of operating progress. But the other side of the coin is speed. Without acquisitions, you can only grow as fast as your own execution engine allows. And going forward, that means Venus’s trajectory will hinge on two things: how productive its internal pipeline becomes, and how well it can choose and execute partnerships like MET-X.

Post-Debt Capital Priorities

With long-term debt off the table, Venus now gets to make a very different kind of decision: not “how do we survive?” but “where do we place our bets?”

The spending priorities show up clearly in what the company is doing. First, funding the work that turns VRP-034 and MET-X from promising science into real products—clinical development, trials, and the obligations that come with licensing a molecule. Second, continuing to maintain and upgrade facilities so the GMP certifications it fought to earn don’t slip. In sterile injectables, compliance isn’t a box you check once; it’s a treadmill you stay on. Third, expanding the patent estate and keeping the global regulatory pipeline moving, because those filings and submissions are what convert invention into defensible access.

And then there’s the unglamorous part that still matters: investing in operations to support a 90-plus-country footprint. Selling in that many markets isn’t “set it and forget it.” It requires ongoing attention—documentation, supply reliability, partner management, and the ability to respond when a regulator or a distributor changes the rules.

What Venus hasn’t done so far is just as telling. It hasn’t prioritized returning cash to shareholders through dividends or buybacks. That’s consistent with a company in reinvestment mode, but it’s a clear signal: management believes the highest-return use of cash right now is building the pipeline and widening the moat, not distributing profits.

Future Optionality

If MET-X is the partnership, it’s also the playbook.

The deal shows a model Venus could repeat: in-license innovation from global biotech, then use its own manufacturing base, regulatory muscle, and hospital-market access to develop and commercialize in India and other emerging markets. Done well, it’s capital-efficient. Venus doesn’t have to fund every early-stage scientific dead end. It can select molecules that already have meaningful validation and then do what it’s good at—turning complex injectable products into something regulators approve and hospitals actually use.

VRP-034, meanwhile, opens the door in the other direction: out-licensing. If the clinical story continues to hold, Venus could choose to partner with a larger pharma company for the United States and Europe—markets where Venus doesn’t have deep commercial infrastructure—while keeping rights in its core territories. That structure would let Venus participate in global upside without pretending it can suddenly build a Western hospital sales force from scratch.

And that’s the real post-crisis change: negotiating leverage. The shadow of Elores still hangs over the story—Cipla almost certainly bought it at a bargain because Venus needed cash and needed it fast. But the lesson seems to have stuck. Venus’s new default setting is to hold on to its best IP unless it truly can’t afford to. If another out-licensing deal happens, the posture will be different, the terms will be different, and the value captured should reflect that difference.

XII. Bull vs. Bear Case and Investment Thesis

The Bull Case

The optimistic thesis for Venus Remedies sits on three pillars.

First, the balance-sheet repair is no longer a promise. It’s done. Zero long-term debt isn’t just a cleaner set of accounts; it’s strategic freedom. It means Venus can fund R&D, sign serious clinical partnerships, and keep upgrading its manufacturing and compliance engine without every decision being hostage to the next interest payment. And the operating numbers have started to reflect that breathing room, with profitability moving in the right direction and net profit rising sharply in FY2025 alongside expanding margins.

Second, the AMR opportunity is real, growing, and structurally undersupplied. Antimicrobial resistance keeps getting worse. Governments are being forced to respond. And Big Pharma, for all its capabilities, has largely stepped back from antibiotics because the economics have been unattractive. That retreat leaves space for specialists. India’s burden—and by extension, its urgency—creates a home market where demand isn’t theoretical, and where a focused player can build product-market fit faster than a foreign entrant trying to learn the system from scratch.

Third, Venus’s innovation story now has outside validation that it didn’t have during the Elores era. The USFDA’s QIDP designation for VRP-034 is a meaningful signal that the product targets a serious unmet need. Add in the MET-X partnership and a patent portfolio north of 135, and Venus has multiple “shots on goal,” not a single do-or-die asset. At roughly ₹978 crore of market cap, the company can start to look mispriced next to many single-asset, US-listed biotech stories that command far higher valuations on far less manufacturing and regulatory infrastructure.

Then there’s the qualitative piece: the redemption arc. A management team that nearly lost the company—and rebuilt it with visible financial discipline—often ends up making sharper capital-allocation decisions than teams that have never had to learn those lessons the hard way.

The Bear Case

The skeptical thesis is just as grounded.

VRP-034, despite the excitement, is still early. The headline nephrotoxicity reduction comes from kidney-on-a-chip models, not large-scale human trials. And drug development is brutal: the path from preclinical promise to approval is where most programs die. MET-X is earlier still. Believing either molecule reaches the market is not a forecast; it’s a probability bet—and the timeline runs in years, not quarters.

Meanwhile, the core business still lives under generic-injectables gravity. Competition is intense. Tender-based procurement often rewards the lowest compliant bid. And with FY2024 revenue of ₹613 crore, Venus remains at a scale disadvantage versus the Indian majors it competes with in the hospital channel. Returns are improving, but not yet great: ROE around 8.1% and ROCE around 12.8% are progress, not proof of a structurally high-quality pharma compounder. The turnaround has made Venus healthier. It hasn’t yet made Venus elite.

There’s also a strategic risk embedded in success. If AMR economics improve—through bigger market-entry rewards, guaranteed purchase commitments, or other “pull” incentives—larger players could decide antibiotics are investable again. If that happens, they’ll re-enter with R&D budgets and commercial reach that dwarf Venus’s.

Finally, key-person risk remains. Pawan Chaudhary’s fingerprints are on both the overreach that led to crisis and the discipline that drove recovery. The next generation is in place, but deeper succession planning beyond the family isn’t fully visible from the outside. And valuation matters: with the stock trading around Rs. 734 in early February 2026 after a strong rally from distress-era levels, the market is no longer pricing Venus like a broken company. The question becomes how much of the “clean balance sheet plus innovation optionality” story is already in the price.

The Three KPIs That Matter

For investors tracking Venus Remedies from here, three metrics cut through the narrative.

Net margin trajectory is the clearest financial signal. The move from mid-single-digit margins toward 7% tells you execution and mix are improving. If Venus can sustainably reach 10% and hold it, that’s when you can argue the company is escaping commodity physics and earning the right to be valued as more than a generic injectables manufacturer.

VRP-034 clinical milestones are the pipeline’s heartbeat. IND progress, Phase I start, Phase II readouts, Phase III enrollment—each one is a de-risking event that either strengthens the thesis or exposes it. If Venus is going to get a true re-rating, it will likely be pulled forward by credible clinical progress, not by preclinical promise alone.

Return on capital employed trajectory is the “whole-company” efficiency test. A ROCE around 12.8% shows improvement, but it still sits below what many investors expect from a strong pharma business. Getting above 15% and sustaining it would be one of the clearest signs that Venus has crossed from survival and repair into durable value creation.

XIII. The AMR Imperative and Venus's Role

The World Health Organization has warned that antimicrobial resistance could drive as many as 10 million deaths a year by 2050 if current trends continue. It’s such a staggering figure that it almost stops meaning anything—until you translate it into something human. Imagine a country the size of Sweden or Portugal disappearing every year. And then imagine that happening again the next year, and the next.

India sits uncomfortably close to the center of this storm. The country accounts for over 40% of global antibiotic consumption, and it’s not hard to see why: a huge population, a heavy infectious-disease burden, antibiotics that are often easy to obtain without prescriptions, widespread use in agriculture and animal husbandry, and sanitation gaps that make infections easier to spread in the first place. Put those ingredients together and you don’t just get more antibiotic use. You get faster evolution. Resistant bacteria learn quickly in an environment like that, and the cost shows up in hospital wards—where carbapenem-resistant infections, once almost unthinkable, are now part of the grim routine.

That context is what makes Venus Remedies such an unusual character in this story. It’s not a giant. It doesn’t have the scale of India’s pharma titans, let alone multinational R&D budgets. But it’s working on one of the biggest problems in modern medicine at the exact moment the global industry has been backing away. Big Pharma’s retreat from antibiotics has left a vacuum—one that governments, NGOs, and international bodies are trying to patch with incentive programs, “push-pull” funding mechanisms, and national action plans. Venus, with a USFDA QIDP designation, an exclusive licensing partnership for MET-X, and participation in the UN Global Compact, has ended up positioned right where those currents converge.

There’s an irony running through the Venus arc. The financial crisis—the debt build-up, the NPA label, the forced sale of Elores—was brutal. But it also imposed the kind of focus that success rarely does. When a company can’t afford to do everything, it finds out what it’s actually willing to fight for. For Venus, the answer narrowed to a few essentials: AMR-focused innovation, global regulatory credibility, and manufacturing quality strong enough to support both.

Whether Venus completes the leap from survivor to category leader is still unresolved. The pipeline is promising, but it hasn’t yet been proven in large-scale human trials. The balance sheet is clean, but the revenue base is still modest. And the competitive gap created by Big Pharma’s antibiotic pullback is real—yet it could tighten if incentives change and the giants decide the economics finally make sense again.

But the one part of this story that isn’t uncertain is the backdrop. The problem Venus is trying to solve—keeping antibiotics effective as resistance rises—doesn’t fade with market cycles. It gets worse, quietly and steadily, in every hospital, in every country, every year.

XIV. Key Lessons and Takeaways

For Founders and Operators

The Venus Remedies story carries a counterintuitive lesson about survival and strategy. Sometimes selling the crown jewel—the product that defines your identity and represents your best work—isn’t a failure of vision. It’s strategic intelligence under pressure. The Elores sale looked like capitulation in 2019. In hindsight, it was the decision that kept the company alive long enough to rebuild the balance sheet, develop VRP-034, earn QIDP designation, and sign the MET-X partnership with Infex. Survival isn’t the absence of strategy. It’s the prerequisite for it.

The second lesson is brutal, and broadly applicable: debt doesn’t just create financial risk. It destroys optionality. A leveraged company can’t fund speculative R&D with patience. It can’t walk away from bad terms. It can’t wait for the right partner. It negotiates with a countdown clock on the table. Venus’s ability to move forward on VRP-034 and take on a licensing program like MET-X without the same level of financial strain was earned the hard way—through years of deleveraging and the discipline that followed the crisis.

Third, Venus shows how smaller companies can compete in global pharma without trying to win a scale war. Regulatory credibility becomes a kind of moat. Certifications and approvals from bodies like WHO, EU regulators, SAHPRA, and Australia’s TGA aren’t things you can buy instantly, even with money. They take time, systems, and a culture of quality that survives inspections year after year. For Venus, that portfolio has functioned as both a barrier to entry and a trust signal—opening doors that raw size alone can’t.

Finally, the company is a clean example of counter-positioning. Venus didn’t beat Big Pharma at Big Pharma’s game. It stepped into a space many large players have treated as structurally unattractive and built there anyway. That’s often the only way a smaller company gets to matter: not by being better resourced, but by being willing to do the hard thing that better-resourced competitors won’t prioritize.

For Investors

Turnarounds are always, at their core, timing questions. Buying Venus in 2019 or 2020—when it was NPA-classified and selling Elores—would have demanded extreme conviction and a willingness to underwrite real downside. Buying after debt clearance and the QIDP designation in 2025 reduced the existential risk, but it also meant paying up for a business that had already proven it could survive. Same company, completely different risk-reward profile depending on when you enter.

Venus also highlights how much of pharma’s value can be “off-balance-sheet.” Patents, regulatory dossiers, and clinical data often don’t show up as assets because accounting rules treat R&D as an expense. But economically, those outputs can be the company. The Elores transaction demonstrated that Venus’s IP could be monetized. And the QIDP designation suggests the remaining pipeline may contain additional value that isn’t neatly captured by book value—or, potentially, even by the current market capitalization.

One more investor takeaway: in pharma, regulatory events are not just headlines. They’re de-risking moments. QIDP, stringent GMP certifications, and credible clinical milestones change probability-weighted outcomes. In the specific case of QIDP, the benefits are not abstract: the pathway can include priority review, fast-track status, and additional market exclusivity. That’s economics, not PR.

For Policymakers

Venus is a case study in how incentive design shapes innovation. The GAIN Act’s QIDP pathway—priority review and extended exclusivity for qualified infectious disease products—is exactly the kind of pull mechanism that can make antibiotic development investable, especially for smaller companies. Without it, VRP-034 is easier to admire than to finance. With it, the development path and potential commercialization window become clearer, and the underlying economics improve. Venus is evidence of the policy working as intended: creating enough reward to bring more players into antibiotics.

There’s also a domestic policy lesson for India. Tender-based procurement that rewards the lowest price is effective for commodities—but it can unintentionally punish differentiation. If India wants more homegrown AMR innovation, procurement frameworks need room to recognize clinical value, not just unit cost. Venus shows the scientific capability and manufacturing infrastructure exists. The next question is whether the system will consistently reward companies for building beyond commodity medicine.

XV. Recommended Resources

If you want to go deeper on Venus Remedies—and the AMR world it’s betting on—start with the 91 Capital research note. It’s one of the most complete, publicly available investment write-ups on the company, and it does a good job connecting the turnaround story to the innovation pipeline.

From there, go to primary sources. Venus Remedies’ own website lays out the pipeline, facilities, and certifications in the way only the company can. For the two biggest recent inflection points, read the USFDA communication around the QIDP designation for VRP-034 and Infex Therapeutics’ press release on the MET-X licensing deal. Those documents are the cleanest way to separate narrative from what’s actually been announced.

To ground the story in market reality, Grand View Research’s antimicrobial resistance report provides the sizing and growth projections referenced here, while the WHO’s AMR surveillance and prevention materials explain the global policy and public-health context behind the demand. If you want to track the company’s numbers and ownership over time, Screener.in is the easiest place to follow historical financials, and Trendlyne is useful for monitoring quarterly shareholding patterns and institutional participation.

And if you want the bigger, human context—why this category matters, and why its economics are so weird—there are a few books worth your time. Matt McCarthy’s Superbugs: The Race to Stop an Epidemic tells the AMR story through the people living it. Stuart B. Levy’s The Antibiotic Paradox is the classic explanation of how overuse turns miracle drugs into blunt instruments. Ben Goldacre’s Bad Pharma is a sharp, skeptical look at incentives and decision-making in the industry—helpful for understanding why so many large companies walked away from antibiotics in the first place. And Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers gives you the strategic language for what Venus is trying to do: build where the incumbents, for rational reasons, don’t want to play.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music