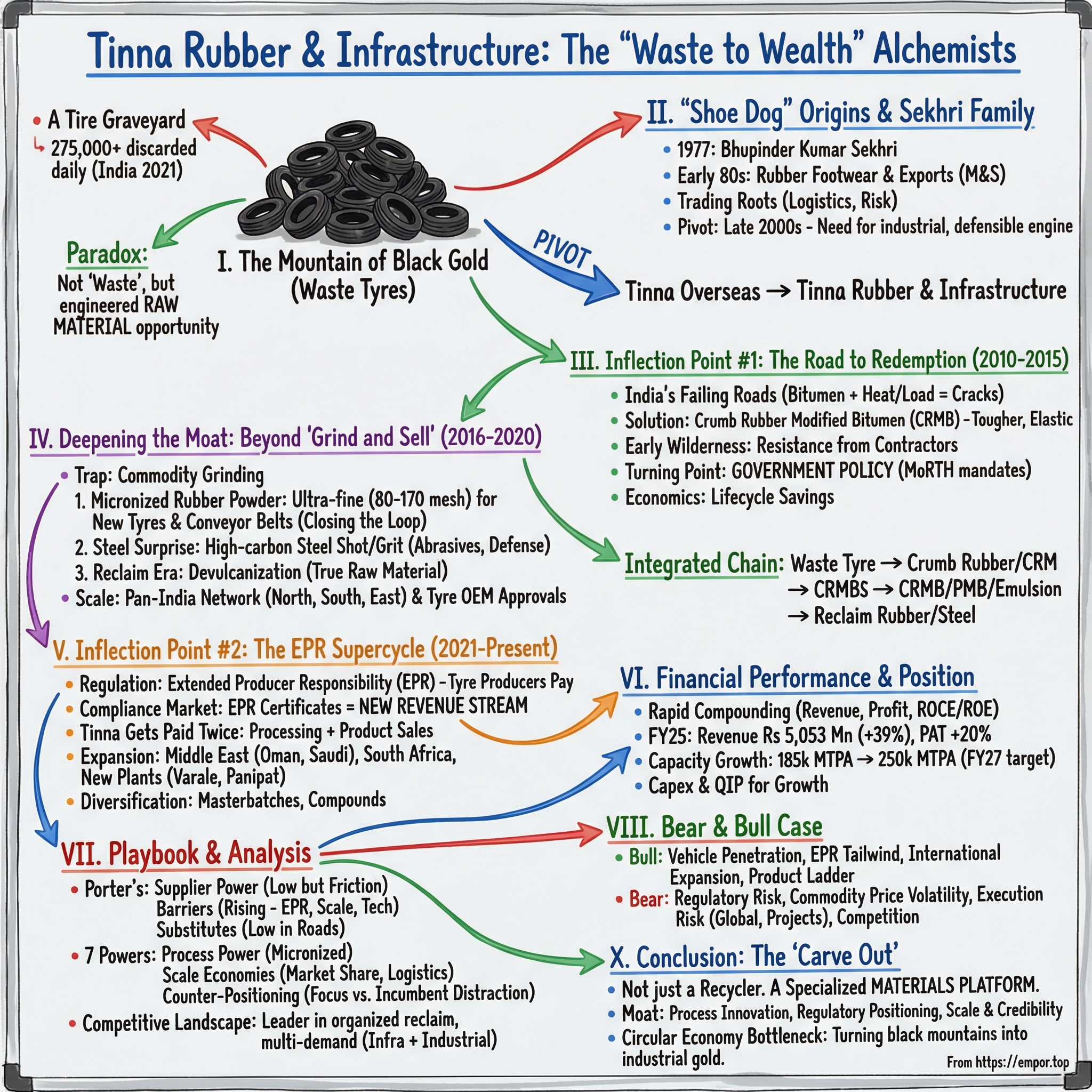

Tinna Rubber & Infrastructure: The "Waste to Wealth" Alchemists

I. Introduction: The Mountain of Black Gold

Picture a tire graveyard. Not a neat stack behind a workshop, but a landscape of black rings stretching to the horizon—a monument to modern mobility and what it leaves behind.

In 2021, India was discarding about 275,000 tyres every day, according to a Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs report. The same report noted a more troubling detail: there was no reliable tracking or monitoring of where those tyres ended up. Globally, the scale is even harder to wrap your head around. Roughly 2.5 billion new tires are produced each year, consuming enormous amounts of oil and natural rubber in the process.

For decades, end-of-life tyres sat in an ugly limbo: too bulky to manage, too tempting to ignore. Burn them and you get toxic fumes. Bury them and you create a fire hazard that can smolder for months. Dump them and they become permanent scars on the edge of cities and highways.

And yet, the paradox is that a tyre isn’t really “waste.” It’s a dense bundle of engineered materials—rubber compounds built to endure heat, friction, and impact, reinforced with high-carbon steel, and packed with hydrocarbons. In other words: it’s a junk problem that also happens to be a raw-material opportunity.

This is where Tinna Rubber enters the picture, riding the tailwinds of the circular economy. The company sources end-of-life (EOL) tyres and recycles them into crumb rubber, crumb rubber modifier, reclaim rubber, and recovered steel as a by-product. By scale, it has become India’s largest EOL tyre recycler.

But the real hook in the Tinna story is that it didn’t begin as an environmental crusade or a tech startup idea. Tinna is the flagship of the broader Tinna group, with roots in leather footwear and components, thermoplastic rubber (TPR) compounds, edible oil, shipping and warehousing, and merchant exports across markets like the UK, Canada, Italy, Australia, and Portugal. This was a family-run trading and manufacturing house that spotted a world-changing opportunity hiding in plain sight—inside a discarded tyre.

Tinna Rubber & Infrastructure Limited (TRIL) was founded in 1977 under the leadership of Mr. Bhupinder Kumar Sekhri, who brought decades of experience in the rubber industry. The business focuses on transforming end-of-life tyres into recycled rubber and steel—materials that flow back into roads, new tyres, conveyor belts, and other rubber-moulded products.

Over time, TRIL grew into the largest integrated waste tyre recycler in India and one of the global leaders in recycled rubber materials. It built manufacturing facilities across Panipat (Haryana), Haldia (West Bengal), Gumudipoondi (Tamil Nadu), Wada (Maharashtra), and Oman, positioning itself as a one-stop supplier across recycled rubber applications.

The thesis is simple: Tinna Rubber is not just a recycler. It is a materials business that understood early that a waste tyre is a collection of valuable inputs, if you know how to unlock them. And it has placed itself right at the intersection of two powerful tailwinds—India’s infrastructure push that demands better road materials, and an Extended Producer Responsibility framework that forces tyre makers to deal with what they sell.

So the investor question becomes: as this market gets more formal, more regulated, and more competitive, can Tinna keep its early lead—scaling beyond India, deepening its technology, and continuing to turn garbage into something that looks a lot like industrial gold?

II. The "Shoe Dog" Origins & The Sekhri Family

To understand Tinna Rubber’s transformation, you have to start with the Sekhri family’s first business—and it wasn’t recycling.

The group was founded in 1977 under Mr. Bhupinder Kumar Sekhri. Within a few years, the company was already doing something unusual for Indian manufacturing at the time: importing state-of-the-art technology from Japan and automating rubber compounding to make footwear soling sheets.

This was the moment when India was beginning to plug into global supply chains. And the Sekhris weren’t building for a protected domestic market. They were training themselves to meet the toughest standards money could buy.

In 1982, the company introduced lightweight rubber slippers using Japanese technology and became a leading rubber footwear manufacturer in India. By 1987, it had commissioned a leather footwear manufacturing unit with machinery imported from Italy and Korea—and grew into one of the largest exporters of high-quality footwear.

That export trajectory matters, because it shaped the company’s operating DNA. If you can ship footwear to European buyers like Marks & Spencer, you learn ruthless quality control, process discipline, and how to hit precise specifications, every time. On 1 April 1991, the company was recognized as an Export House by the Government of India.

The people around the business also reflected that bridge between industry and policy. Board member Mr. Vaibhav Dange brought deep experience in government administration and infrastructure, including associations with the National Highways Authority of India, the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways, and FICCI. He drafted policy papers and worked across investment promotion and policy reform—expertise that would become increasingly relevant once “rubber” and “infrastructure” started to converge.

The second generation stepped in with a different but equally useful toolkit. Mr. Gaurav Sekhri, who studied business in London, became a promoter director of Tinna Rubber and Infrastructure Ltd and led Tinna Trade Limited as Managing Director. With more than two decades in trading, he developed the instincts that matter in physical commodities: logistics, timing, relationships, and risk management across cargo handling and warehousing.

That merchant-trading background turned out to be more than a footnote. Decades of moving goods across borders teaches you shipping logistics, customs processes, currency exposure, and the rhythm of global markets—the same muscles you need when your raw material is something as unglamorous and logistically messy as end-of-life tyres.

But by the late 2000s, the old playbook was losing its edge. Footwear exports were commoditizing fast, and low-cost competition from Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Cambodia was squeezing India’s position. The Sekhris needed a new engine—something industrial, defensible, and less vulnerable to the whims of fashion cycles.

That pivot became visible in the early 2010s. The company started production at its Haldia plant in May 2013. And as the business increasingly centered on crumb rubber, crumb rubber modifier, and the processing and mixing of bituminous products, it changed its name in 2012–13 from Tinna Overseas Limited to Tinna Rubber And Infrastructure Limited.

That name change was more than branding. “Overseas” spoke to trading and exports. “Rubber and Infrastructure” signaled a bet on a completely different future: India would build roads at massive scale, road quality requirements would rise, and waste tyres could become a reliable feedstock for better-performing materials.

What the Sekhris were really hunting for wasn’t fickle consumer demand. It was sticky, industrial B2B revenue—long-term relationships with road contractors, tyre companies, and infrastructure players who would need supply year after year.

And they found the opportunity in the least romantic place imaginable: the growing mountains of discarded tyres.

III. Inflection Point #1: The Road to Redemption (2010-2015)

The insight that changed Tinna’s trajectory didn’t come from a lab. It came from a very Indian reality: roads that fall apart.

India’s highways take a beating—scorching summers, waterlogged monsoons, and trucks that carry more than they should. Traditional asphalt can’t keep up. It cracks, ruts, and sheds layers far sooner than anyone wants, turning road maintenance into a recurring national expense and a constant friction point for economic growth.

At the center of it all is bitumen: the sticky black binder that holds aggregates like sand, gravel, and crushed stone together. Bitumen is derived from crude oil, and it’s good at what it’s supposed to do—until it isn’t. In extreme heat it can soften and deform; in wet conditions it can become slick; and as it ages it turns brittle, making cracks almost inevitable.

The fix had already been proven elsewhere. In markets like the United States, engineers had learned that blending rubber into bitumen makes roads tougher and more elastic. That’s the idea behind Crumb Rubber Modified Bitumen (CRMB): use recycled crumb rubber from end-of-life tyres to change the performance of the binder. The rubber improves flexibility and heat stability, helps the road “recover” after stress, and reduces cracking driven by temperature swings and heavy traffic. And as a bonus, it turns a waste problem into a construction input—an early, practical version of the circular economy.

Tinna says it pioneered rubberised bitumen in India and laid 48 test tracks across the country in 1998. Over time, it became the largest producer of crumb rubber modifier (CRM), which it says has been used in road construction across the nation at significant scale.

But inventing a solution and getting the industry to adopt it are two very different battles. The early years were the wilderness years.

Road contractors didn’t want to change a working recipe. Conventional bitumen had familiar specs, entrenched suppliers, and predictable procurement. Rubberised roads meant new handling, new standards, and perceived risk. And there was resistance from incumbents who had no incentive to welcome a material shift.

Still, Tinna kept building capability. It claims that by 2010 it had become the largest producer of CRMB and had commissioned a bitumen emulsion plant. In 2014, it commissioned a reclaim rubber plant—another step toward extracting more value from every tyre it processed.

Then came the moment that turned persistence into momentum: policy.

India’s Ministry of Road Transport and Highways (MoRTH) recommended the use of polymer/rubber modified bitumen in specific pavement layers for national and state highways, and issued circulars supporting its use on NHs and other centrally sponsored schemes. For a company trying to convince thousands of contractors one project at a time, a government push like that changes the whole game.

As India’s road-building agenda accelerated—through programs that expanded and upgraded highway networks—rubber-modified bitumen stopped being an “interesting option” and started becoming a specified material. The sales pitch shifted from innovation to compliance, and from “try this” to “this is what the project calls for.”

The economics helped. CRMB can increase road life versus conventional bitumen modifiers, making the trade-off easier to justify: slightly higher cost upfront, fewer repairs and rebuilds later. In a country laying and maintaining enormous highway mileage, those lifecycle savings add up quickly.

Tinna didn’t just grind rubber and sell a commodity. It worked to integrate the chain—from waste tyre processing into crumb rubber and CRM, into CRMB and related bituminous products such as polymer modified bitumen (PMB) and bitumen emulsion, and into adjacent outputs like reclaimed rubber, ultrafine crumb rubber compound, and cut wire shots. These products fed into road construction, tyre manufacturing, and auto components.

By the end of 2015, the story had flipped. Tinna wasn’t a niche player trying to persuade a reluctant market. The market itself was moving—pulled by government standards and the demand for longer-lasting roads—and Tinna’s products were increasingly positioned right in the middle of that shift.

IV. Deepening the Moat: Beyond "Grind and Sell" (2016-2020)

Success attracted copycats. Once Tinna showed there was real money in end-of-life tyres, the obvious question followed: what stops anyone else from buying a shredder, setting up a yard, and selling crumb rubber?

That was the trap. Basic tyre grinding isn’t proprietary. The machines can be bought off-the-shelf, the process is widely understood, and the feedstock is everywhere. If Tinna stayed a “grind and sell” player, it risked becoming just another commodity producer, fighting on price and nothing else.

So the company made a deliberate move up the value chain—toward products that required tighter process control, deeper customer relationships, and more specialized output.

The Micronized Rubber Powder Pivot

The first leap was from standard crumb rubber to ultra-fine micronized rubber powder. Tinna began producing ultra-fine, high-structure crumb in the 80–100 mesh range from radial truck and bus tyres.

The point of going finer is simple: the smaller the particle, the easier it is to blend uniformly into higher-performance applications. Coarse crumb works for some uses, but ultra-fine powder starts to behave like an ingredient—something you can formulate with, not just mix in.

The Indian Rubber Manufacturers Research Association (IRMRA), in its study, concluded that as crumb particle size reduces, physical properties improve. It also found that using 10 phr of 80/100 mesh crumb did not lead to a loss of properties, even though carbon phr had to be reduced to maintain hardness—meaning manufacturers could reduce costs without sacrificing performance.

Tinna says it was among the first companies globally to produce micronized rubber powder up to 170 mesh, and it manufactures up to 180 mesh. And that matters for one big reason: ultra-fine rubber powder can be used in new tyre manufacturing. That’s the loop closing—waste tyres becoming input material for the next generation of tyres.

Tinna became the largest supplier of micronized rubber powder (MRP) to the tyre and conveyor belt industry in India. IRMRA’s work using Tinna crumb showed that up to 15 phr of crumb rubber in a standard tyre tread compound did not significantly affect key properties. The company also cites a separate study in the USA, conducted with large tyre companies, that confirmed the use of 80–100 mesh crumb in new tyres.

The Steel Surprise

The second moat-builder was hiding inside every tyre: steel.

Tinna’s product portfolio expanded beyond rubber outputs into materials like high-carbon steel shot, high-carbon steel grit, and high-carbon cut wire shots (polished and conditioned), alongside its rubber and bitumen-linked products such as CRM, CRMB, PMB, and bitumen emulsion.

A typical truck tyre contains about 15–20% steel by weight—the belts that give radial tyres their strength. For many recyclers, that steel is an annoyance, pulled out and dumped into the scrap market.

Tinna saw something else. It began commercial production of high-carbon steel shots in FY 2014–15 and established wire processing to make value-added, higher-quality high-carbon steel products. Processed correctly, recovered steel could be sold as abrasives used for shot blasting and surface preparation—critical steps in shipbuilding, construction, and industrial manufacturing. The company also pointed to defense demand as a driver of growth for steel abrasives.

This wasn’t about competing head-on with virgin steel producers. It was about carving out a high-spec niche where consistency and cleanliness matter—and where “recycled” doesn’t automatically mean “low value.”

The Reclaim Era

Then came reclaimed rubber—the step that pushed Tinna furthest away from commodity recycling.

The company started reclaimed rubber and ultra-fine crumb rubber compound during FY 2015–16. Unlike crumb rubber, reclaimed rubber goes through a devulcanization process that partially restores rubber’s chemical properties, making it far closer to a true raw material than a filler.

Tinna had commissioned a reclaim rubber plant in 2014, and it sold reclaim rubber to manufacturers of tyres, conveyor belts, and mats. This shift changed the company’s identity in the supply chain: it was no longer just processing waste. It was supplying an input that tyre companies could qualify and rely on.

That qualification isn’t easy. Tyre manufacturers typically take 2–3 years to approve recycled raw materials, because performance and consistency are non-negotiable. Tinna says it does business with all leading tyre manufacturers in India and has also been approved to supply two international players.

By 2016–17, the company had reinforced this strategy with geography. It built a nationwide footprint with plants in the North at Panipat (Haryana) and Kala-amb (Himachal Pradesh), in the South at Gummdipoondi (Tamil Nadu), and in the East at Haldia (West Bengal).

The logic was straightforward: national customers prefer national suppliers. A pan-India network meant Tinna could serve road contractors operating across states and tyre companies with multiple plants—coverage that smaller regional recyclers simply couldn’t match. Scale, at this point, wasn’t just efficiency. It was part of the moat.

V. Inflection Point #2: The EPR Supercycle (2021-Present)

If government road-building standards were Tinna’s first regulatory tailwind, Extended Producer Responsibility, or EPR, was the wave that rewired the entire industry’s economics.

Waste tyre management in India is regulated under Schedule IX of the Hazardous and Other Waste (Management and Transboundary Movement) Amendment Rules, 2022, built around the principle of Extended Producer Responsibility. On July 22, 2022, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) notified the Hazardous and Other Wastes (Management and Transboundary Movement) Amendment Rules, 2022, formally bringing waste tyres under EPR through Schedule IX of the 2016 rules.

The idea is simple, and its consequences are anything but: tyre producers are now responsible for what happens after the sale. They can’t just manufacture tyres, collect payment, and leave municipalities and informal operators to deal with the mountain that follows. The burden of disposal shifts back onto the companies that put tyres into the system in the first place.

The obligations were phased in. EPR requirements ramped up from partial coverage in the initial years to full coverage after FY 2024–25, reaching 100% based on prior-year production/imports. For units built after April 2022, obligations are tied to the previous year and can go up to 100%.

And critically, compliance runs through a formal, trackable market. Producers are deemed to have met their EPR obligations by purchasing EPR certificates online from registered recyclers and submitting them through the portal on a quarterly basis.

This is where Tinna’s model flips.

Before EPR, waste tyres were a raw material the company largely had to buy—often including imports—turning feedstock into a meaningful cost line. Under EPR, the producer needs proof of recycling, and the recycler is the one who can issue it. So instead of paying to acquire tyres, Tinna can get paid to process them and generate certificates.

That changes everything. Tinna now effectively gets paid twice: once through EPR credits purchased by tyre manufacturers, and again when it sells the resulting outputs—crumb rubber, reclaimed rubber, and steel abrasives—into end markets. Compared with the pre-EPR era, the unit economics become dramatically more attractive.

You can see the pressure this created upstream. Tyre makers themselves acknowledged the impact: Apollo Tyres, CEAT, and MRF cited profit hits tied to provisions for EPR compliance. MRF, for example, took a Rs 145 crore provision in a recent quarter related to EPR. For context, MRF is India’s largest tyre manufacturer, with annual sales exceeding Rs 27,000 crores. When that kind of money has to be set aside for compliance, it doesn’t disappear—it flows to authorized recyclers who can supply the certificates.

Tinna, as a registered and scaled player, was positioned to be a direct beneficiary. The company reported revenue growth of 46% year-on-year to Rs 1,350 Mn, including Rs 296 Mn from EPR credits.

The Expansion Phase

With the economics improving and regulation doing the heavy lifting on demand, Tinna moved into expansion mode.

One major step was the Middle East. Tinna expanded by acquiring a majority stake in an Oman-based tyre recycling operation, which it said would take combined capacity to about 200,000 tonnes of waste tyres per year—positioning it, by its claim, to become the largest waste tyre recycler in Asia. Just as important, Oman becomes a platform for the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region.

In 2023, at Saham—about 200 km from Muscat—the Oman operation ran as Global Recycle LLC. The plant was operating successfully at around 85% capacity utilization.

Tinna also began trying to export one of its earliest playbooks into a new geography: rubberized roads. The company engaged with Oman’s Road Ministry to promote rubberized bitumen for roads and highways. A trial patch using waste rubber powder was laid and was under evaluation. It hired professionals to build demand for recycled rubber materials across the GCC.

Saudi Arabia was next on the map. Tinna incorporated a joint venture entity, Tinna Rubber Arabia Ltd., with an initial plan to set up a tyre recycling plant of 24,000 MT per annum. The Saudi JV’s 24,000 TPA plant was scheduled for commissioning in H2 FY26. A South Africa JV received permission to export 24,000 end-of-life tyres to India, with operations expected to start in Q1 FY26.

The geographic logic is straightforward: the Middle East and Africa generate significant tyre waste, but much of the recycling ecosystem is still underdeveloped. By placing processing capacity closer to where tyres are discarded, Tinna can reduce shipping friction and capture value that otherwise leaks into informal channels or landfills.

Back in India, the build-out continued. In FY 2024, Tinna established a tyre recycling plant at Varale, Maharashtra, and a Polymer Composites/TPR/TPV plant at Panipat, which began production in February 2024.

And then came the next broadening of the ambition. In 2024, Tinna diversified into masterbatches, polymer compounds, and composites—an extension of the same underlying thesis: don’t just be a recycler at the bottom of the value chain. Become the materials supplier industries depend on, with circularity baked into the product.

VI. Financial Performance and Strategic Position

By the time EPR kicked in and the expansion plans started turning into real plants, the business stopped looking like a clever niche and started looking like a machine. The pivot from footwear exports to waste-tyre recycling didn’t just create a new narrative—it showed up in the numbers.

Over the last few years, the company reported rapid compounding across the P&L, with revenue and profitability rising sharply and returns staying strong. It posted FY24 ROCE of 28% and ROE of 32%. Under its Vision 2027 plan, management has talked about sustaining high growth—targeting a revenue CAGR of more than 25% and profit CAGR of 33%.

In FY25, Tinna reported 20% year-on-year PAT growth, with revenue up 39% to Rs 5,053 Mn. It also highlighted its widening footprint beyond India, with operations underway in Oman and planned moves into Saudi Arabia and South Africa.

Across the most recently cited three-year window, the company reported a CAGR of about 30% in revenue, 27% in EBITDA, and 42% in PAT. Management also framed FY25 as a “beat” versus its own targets—revenue came in at roughly Rs 505 crore against guidance of Rs 500 crore—while PAT grew 20% YoY and EBITDA 22% YoY, despite cost pressures.

Under the hood, the operating metrics tell you where that growth came from. Infrastructure revenue rose 18% YoY to Rs 2,220 Mn. CRMB processing volumes increased 75%, and the bitumen emulsion business grew 50% YoY. The company also reported broad-based volume growth: tyre processing up 35%, steel up 95%, industrial up 46%, and consumer up 58%.

Capacity is the other half of the story. In FY25, Tinna said its tyre crushing capacity scaled to 185,000 MTPA—above earlier guidance of 150,000 MTPA—and it is targeting 250,000 MTPA by FY27. In other words: management isn’t expanding because demand might show up. It’s expanding because, in its view, demand is already pulling the system forward.

That confidence shows up in capital allocation too. The company said it completed capex of Rs 50 Cr in FY25 and planned roughly Rs 100 Cr over the next two years. It also discussed a QIP in the Rs 125–150 Cr range to fund a carbon black plant and further expansion. And while it previously guided to Rs 900 Cr revenue by FY27, it later reset expectations to Rs 1,000 Cr by FY28—still larger, but acknowledging the scale-up takes longer than the most optimistic timeline.

The growth, importantly, wasn’t confined to one year. In the first quarter of FY25, Tinna reported revenue growth of 69% YoY, alongside a 40% increase in EBITDA and EBITDA margins of 18.2%. Net profit rose 130% YoY.

Put it together and you get a clear picture of what Tinna is trying to become: not a recycler that happens to sell some rubber, but a scaled materials platform—built on regulation, reinforced by capacity, and increasingly funded like a growth industrial business rather than a scrap operator.

VII. Playbook: Analysis & Competitive Positioning

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Supplier Power: Low

Waste tyres don’t behave like a normal raw material market. This isn’t iron ore or crude where suppliers can pick and choose among dozens of clean, liquid buyers. Waste tyres are bulky, regulated, and increasingly hard to “dispose of” quietly.

According to TRRAI’s Goyal, India has about 800 registered recyclers, representing roughly 70–80% of the sector. Most of that capacity is concentrated in a few states, especially Uttar Pradesh and Haryana.

For aggregators and generators of waste tyres, the menu of legal options has been narrowing. Environmental enforcement has pushed back on dumping and informal burning, and the unorganized sector is under more scrutiny. That dynamic tilts power toward organized recyclers at scale. In many cases, suppliers need a compliant recycler more than a recycler needs any single supplier.

That said, Tinna hasn’t been fully insulated from sourcing friction. Despite the sheer abundance of end-of-life tyres in India, the company has struggled to secure enough domestic supply and has been importing around 60% of its requirement. Over time, that dependence should reduce as EPR pulls more domestic tyre waste out of informal channels and into the hands of registered recyclers.

Barriers to Entry: Rising

A decade ago, tyre recycling looked like a classic low-barrier business: buy a shredder, find feedstock, sell crumb. EPR changes that. It turns recycling from a loosely policed scrap trade into a compliance-linked industry.

Units are classified based on pollution intensity, and enforcement has already led to the closure of non-compliant facilities. To play in the formal market, recyclers now need registration, audits, and consistent environmental compliance. They also need systems—especially IT and reporting—to track material flows and generate EPR certificates that producers can actually use on the portal.

And then there’s scale. Large tyre manufacturers don’t want dozens of small, inconsistent suppliers. They want a few credible partners who can handle volume, deliver uniform quality, and stay compliant. That combination of regulation, systems, and customer expectations raises the bar well above “anyone with capital can enter.”

Threat of Substitutes: Low

In roads, Tinna’s core infrastructure product—CRMB—doesn’t have a perfect substitute that matches performance, economics, and environmental upside. Conventional bitumen is the obvious alternative, but mandates and specifications increasingly push contractors toward modified binders for durability.

In industrial applications, the substitute is virgin rubber. India’s tyre and rubber recycling industry is estimated at around Rs 35 billion and is expected to grow significantly as the automobile base expands and recycling becomes more value-added.

The swing factor is crude. When oil prices are high, virgin synthetic rubber gets expensive and recycled rubber looks even more attractive. When oil prices fall sharply, virgin material becomes cheaper, and recycled inputs can face pricing pressure. The flip side is that EPR keeps a floor under recycling activity even when commodities move against it.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Process Power

Tinna says it was among the first companies globally to produce micronized rubber powder up to 170 mesh. Producing ultra-fine rubber consistently and at scale isn’t just about installing a machine—it’s a process capability built through iteration, know-how, and quality control. In a way, it’s a straight line from the group’s footwear-manufacturing heritage: decades of learning how to make rubber behave to spec, every time.

Scale Economies

Tinna says it holds over 60% market share in India and is the first and largest player in rubberized bitumen (CRMB) domestically.

Scale shows up in the unglamorous but decisive places: sourcing leverage, logistics efficiency, ability to supply customers across India, and better absorption of fixed costs. It also signals reliability—something tyre OEMs care about deeply when they’re qualifying recycled inputs.

Counter-Positioning

There’s also a structural advantage in who can even choose to compete.

Traditional tyre manufacturers could, in theory, integrate backward into recycling. In practice, that means building new facilities, learning a different business, and taking on an operational and compliance-heavy workflow that sits far outside their core competency of making new tyres. It competes for the same capital and management attention they’d rather deploy into capacity, branding, and distribution.

For Tinna, recycling isn’t a side project. It is the business. That asymmetry creates real counter-positioning: what’s “optional and distracting” for an incumbent is “core and compounding” for the specialist.

Competitive Landscape

India’s formal reclaim rubber market is still relatively small. Roughly 40 producers participate in the organized reclaim segment, and there are around six to seven key players in tyre recycling and reclaiming rubber products. Industry leaders include Tinna Rubbers, Gujarat Reclaim and Rubber Products Ltd., ELGI Rubber Company Ltd., Balail Industries, Swani Rubber Industries, Gangimani Enterprise Private Limited, and Kohinoor Reclamations.

So yes—there are competitors. But Tinna’s claimed >60% market share suggests more than a crowded commodity fight. It reflects first-mover advantage, a broader product portfolio, and a rare positioning that spans both of the big demand engines: infrastructure (roads) and industrial (tyre manufacturing).

VIII. The Bear & Bull Case

The Bull Case

India’s vehicle penetration is still low compared to developed markets. As incomes rise and more vehicles hit the road, the next thing that grows—quietly but inevitably—is the volume of end-of-life tyres.

That’s why the upside here is not incremental. Industry estimates suggest India’s tyre recycling market, currently around Rs 35 billion, could expand dramatically over the next 5–10 years—potentially toward Rs 350 billion—as automobile sales climb and recycling shifts from informal disposal to higher-value processing.

EPR is the structural tailwind. It isn’t a “nice to have” ESG trend; it’s a compliance requirement. Tyre producers and importers have to close the loop by buying EPR certificates from registered recyclers, and the targets ramp to full coverage—100% in 2024–25 for tyres produced or imported in 2022–23. In other words, demand for compliant recycling is being written into the rulebook.

Then there’s geography. If Tinna executes internationally, it stops being “an Indian recycler” and starts looking like a regional platform. The company has formed Tinna Rubber Arabia Ltd. and outlined plans for a Saudi tyre recycling plant with an initial capacity of 24,000 MT per annum. It is in the process of locating land, starting infrastructure work, and is targeting production in H2 FY26.

Finally, there’s the product ladder. In 2024, Tinna expanded into masterbatches, polymer compounds, and composites—an attempt to move further from “recycling output” and closer to “materials company,” where specifications, customer stickiness, and value-add tend to be higher.

Management has also articulated an ambition of sustaining 30%+ ROCE by FY28, supported by the ramp-up of Varale, a carbon black plant, and contribution from global operations.

The Bear Case

Regulatory Risk

Tinna’s best tailwinds are also its biggest dependencies. EPR was introduced for waste tyres in 2022, but available commentary suggests compliance across the tyre industry is still uneven. If enforcement lags—or if the government softens or delays implementation—EPR-linked cash flows could arrive slower than expected.

The same risk exists in roads. If mandates and specifications around modified bitumen are relaxed, or if infrastructure demand slows, the “rubberized roads” engine loses torque.

Commodity Risk

Tinna ultimately sells into markets that benchmark against virgin inputs. If crude oil falls sharply, virgin rubber and bitumen become cheaper, and recycled alternatives can lose their pricing edge.

You can also see how costs can bite even in good demand environments. The company reported FY25 EBITDA margin of 15.1% versus 17.2% in FY24, attributing the compression to higher ocean freight and raw-material costs.

Execution Risk

Expansion is a double-edged sword. Management has said the QIP is meant to create “firepower” for possible inorganic growth—but that also introduces dilution questions and raises the bar for capital allocation discipline.

There’s also a key project investors are watching: the recovered carbon black plant. It remains strategically important, but the company has not provided clear details on timeline, capex, or location. The longer it stays undefined, the more it becomes an execution overhang.

And running plants across Oman, Saudi Arabia, and South Africa adds real complexity—different regulations, labor markets, and operating environments. International growth can diversify the business, but it can also stretch management bandwidth and distract from the Indian core.

Competition Risk

At the base level, crumb rubber is still a crowded space, with many small regional players.

While EPR and compliance requirements raise barriers over time, attractive economics tend to pull in capital. If larger, well-funded competitors scale up capacity and certification, margins could compress and customer bargaining power could rise—especially in the more commoditized product segments.

IX. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you want to track whether Tinna’s story is getting stronger or just sounding good on slides, there are two KPIs that cut through the noise.

1. Tyre Processing Volume Growth

Tyres processed were about 134,000 MT in FY25, up from 99,280 MT in FY24.

This is the heartbeat of the company. Tinna can have the best regulatory setup in the world, but it only monetizes that advantage if it can physically bring tyres in, run them through the system, and ship consistent output. Volumes tell you whether the plants are ramping, whether sourcing is improving, and whether Tinna is actually taking share.

It’s also the reality check on expansion promises. Management has guided to 250,000 MTPA of capacity by FY27. The key isn’t just announced capacity—it’s throughput. Watching how quickly actual processed volumes close the gap to installed capacity will tell you a lot about demand, execution, and operational discipline.

2. EPR Credit Revenue as a Percentage of Total Revenue

The company reported revenue growth of 46% year-on-year to Rs 1,350 Mn, including Rs 296 Mn from EPR credits.

This is the KPI that captures the new economics of the business. EPR credits are what turn tyre recycling from a tough sourcing game—where you often pay to secure feedstock—into a model where you can get paid for doing the cleanup.

If EPR credit contribution rises over time, it’s a sign that enforcement is tightening, compliance is improving, and the regulatory tailwind is showing up in cash flow. If it stalls or falls, that’s worth paying attention to—it could point to slower compliance, weaker pricing for credits, or more competition among registered recyclers.

X. Conclusion: The "Carve Out"

Tinna was once Tinna Overseas Limited. In December 2012, it changed its name to Tinna Rubber and Infrastructure Limited—a quiet corporate move that, in hindsight, marked a loud strategic pivot. The company had been founded in 1977 and is headquartered in New Delhi.

Because what changed wasn’t just the name. It was the direction of the whole enterprise.

A family business that learned unforgiving quality control by exporting to buyers like Marks & Spencer, that built global logistics instincts through trading, and that developed deep, hands-on understanding of rubber through decades in footwear manufacturing eventually realized those skills all pointed to the same unlikely prize: end-of-life tyres. A messy, regulated, unloved input—hiding a portfolio of industrial raw materials inside it.

Today, Tinna is a leading player in tyre recycling. It converts waste tyres into products like crumb rubber and modified bitumen that feed directly into road construction. It has also positioned itself as a sustainability-linked supplier, offering alternatives that fit the direction infrastructure is being pushed—toward better performance and better compliance. By scale, it has become India’s largest integrated waste tyre recycler, with manufacturing facilities across India and one in Oman, and it ranks among global leaders in recycled rubber materials.

But the most accurate way to describe Tinna now isn’t “recycler,” at least not in the usual sense of the word. This is a specialized materials and chemicals business wearing the clothes of waste management. Its products don’t compete with other scrap operators; they compete with virgin inputs coming from petroleum refineries and steel mills. Its customers aren’t municipalities; they’re road contractors, tyre manufacturers, and industrial buyers who care about consistency, specs, and supply reliability.

That’s the carve-out: Tinna’s moat isn’t built on access to garbage. It’s built on process innovation, regulatory positioning, and the scale and credibility required to serve demanding industrial customers—especially in a world where compliance is no longer optional.

The company says it recovers 99% of materials from end-of-life tyres, pushing the economics further toward “waste to wealth” and deeper into the circular economy.

And that’s why this story matters beyond one company. As the world shifts from “Take-Make-Waste” to “Reduce-Reuse-Recycle,” businesses like Tinna sit right at the bottleneck. Every tyre that rolls off an assembly line eventually becomes someone’s problem. Regulation is increasingly ensuring that “someone” is a registered, compliant recycler. And among those recyclers, the winners won’t be the smallest or the cheapest—they’ll be the ones with technology, throughput, and relationships that make them hard to replace.

The Sekhri family made this bet more than a decade ago, effectively trading a commoditizing footwear export engine for a regulated, industrial materials platform. So far, it looks like the bet is working.

Now comes the investor question: can Tinna defend its lead as the market matures, execute global expansion without losing operational focus, and keep turning black rubber mountains into something that increasingly resembles industrial gold?

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music