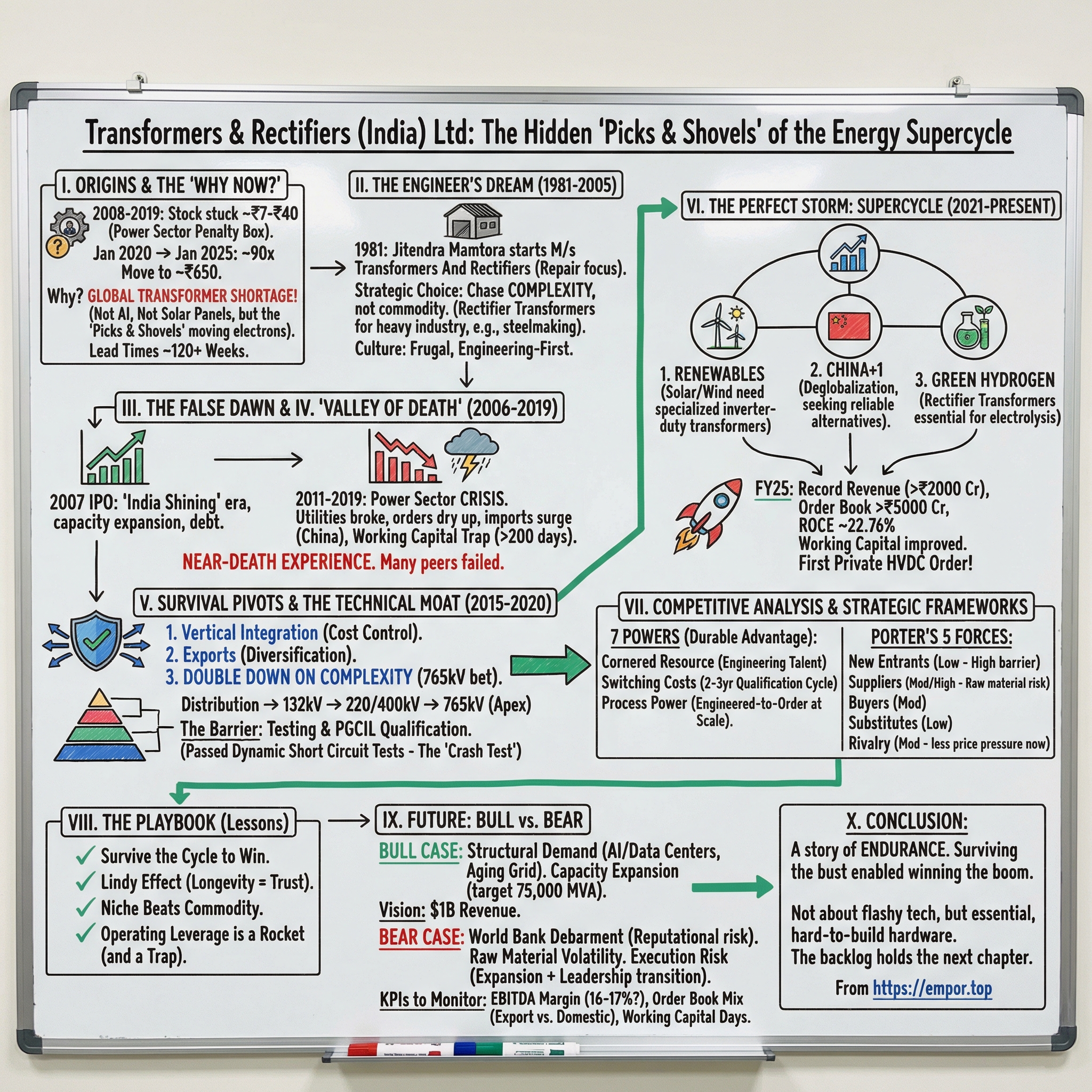

Transformers & Rectifiers (India) Ltd: The Hidden "Picks & Shovels" of the Energy Supercycle

I. Introduction & The "Why Now?"

The chart looks wrong at first.

For a full decade, from 2008 to 2019, shares of Transformers & Rectifiers (India) Ltd—TARIL—did almost nothing. The stock drifted between ₹7 and ₹40, stuck in the penalty box with the rest of India’s power sector, an industry investors had come to treat like a graveyard of stalled projects and broke state utilities.

Then the line on the chart stops meandering and goes vertical.

In January 2020, TARIL traded around ₹7.40. By January 2025, it had climbed to about ₹650—roughly a 90x move in five years. That kind of run is supposed to belong to software darlings, not to a company that builds oil-filled slabs of steel that can weigh as much as 400 tons.

So what changed?

Not a flashy new product. Not a sudden, genius reinvention. The real shift happened outside the company: the world woke up to an unglamorous bottleneck in the electrification story.

Everyone talks about Nvidia powering AI and solar panels remaking generation. Almost nobody asks the more basic question: once you produce electricity, how do you move it—reliably, at scale, across long distances, into cities, factories, and data centers?

That answer runs through transformers. Massive machines that step voltage up and down as power travels from plants to transmission lines, into substations, and eventually into your home. And in the 2020s, the transformer shortage turned into one of the most important supply chain constraints in energy—showing up in utility capex plans, renewable rollout timelines, and national conversations about grid resilience.

What began as a tight market became a full-blown crunch: years of underinvestment in manufacturing capacity collided with a post-pandemic surge in construction and electrification, while key inputs like grain-oriented electrical steel and copper stayed volatile.

The U.S. felt it acutely. By 2025, shortages for power transformers and distribution transformers were estimated at about 30% and 10%, respectively. Demand since 2019 had jumped—up 116% for power transformers and 41% for distribution transformers. And lead times became the headline. In 2024, the North American Electric Reliability Corporation reported waits of roughly 120 weeks—more than two years—with large power transformers stretching as long as 210 weeks, nearly four years.

This wasn’t just an American problem. It was global. And it created a moment where surviving, capable manufacturers suddenly became strategic assets.

That’s where TARIL enters the story: a company that endured the brutal Indian power-sector downturn of the 2010s and came out the other side with something rare—engineering depth and manufacturing capability for high-complexity, high-voltage transformers. From modest beginnings in repair work, TARIL grew into one of India’s largest private transformer makers, hitting major technical milestones along the way, including India’s first 1200 kV transformer and a 420 kV ester-filled reactor, and expanding its reach beyond India.

This is the story of how a business started by an electrical engineer in a small shed in Gujarat ended up becoming a critical node in the global energy transition.

It’s a classic picks-and-shovels setup. While the world chases the gold rush of AI and clean power, the companies that make the heavy, essential hardware—the stuff that actually moves electrons—can end up as the quiet winners.

II. Origins: The Engineer's Dream (1981 – 2005)

Long before TARIL became a name utilities and heavy industry would recognize, it was just one engineer learning the trade the hard way.

In 1969, Jitendra Mamtora, fresh out of electrical engineering school, took a job at the Electrical Equipment Manufacturing Company. He wasn’t selling transformers or managing projects from a distance. He was inside the work—understanding how these machines are designed, built, and, most importantly, how they fail. He spent more than a decade sharpening that craft.

Then, in 1981, he bet on himself.

Mamtora set up a small proprietary concern under the name M/s Transformers And Rectifiers (India). It wasn’t a gleaming factory turning out new equipment by the truckload. It was a workshop, focused largely on repairing and servicing transformers—work that forces you to confront reality. If manufacturing teaches you how things should work, repair teaches you why they don’t.

After working as an engineer in eastern India, Mamtora moved to Gujarat and started building a business with a simple intent: design and manufacture quality transformers. Over time, TARIL developed a pan-India footprint—but the seed of that growth was planted early, in one very specific strategic choice.

Mamtora didn’t chase the easy market.

Across India, plenty of small players could build standard distribution transformers. Those products are essential, but they’re also close to commodity: units that step voltage down from 11kV to 400V are widely available, and buyers can often pit suppliers against each other on price.

Mamtora went in the opposite direction. He chased complexity—because in transformers, complexity is where the moat lives.

That’s where rectifier transformers come in. These aren’t general-purpose grid machines. They sit at the boundary between the AC grid and DC industrial processes—used in heavy applications like electrolysis, chemical production, and metal smelting. And they demand a different kind of engineering.

Take steelmaking in an electric arc furnace. Electrodes generate arcs that can reach roughly 3,000°C to melt scrap. The electrical load is brutal: sudden current spikes, ugly harmonics, intense heat, and stress patterns that can punish equipment nonstop. A normal transformer, designed for steadier conditions, can’t survive that environment for long.

TARIL’s rectifier transformers were built for it—bridging AC supply and DC conversion with specialized features like in-built snubber circuits, configurable LV terminals, and oil-to-water heat exchangers, engineered to cope with high harmonic currents in processes like electrolysis and smelting.

The market for these products was smaller, and the work was harder. But the payoff was the kind of customer relationship you don’t easily lose. In heavy industry, a transformer failure isn’t just a replacement cost. It can mean stalled production and enormous losses. When reliability is the difference between profit and shutdown, customers don’t switch suppliers casually.

As the business matured, it formalized. The company was incorporated as Triveni Electric Company Limited on July 11, 1994, promoted by Mr. Jitendra U. Mamtora, Mrs. Karunaben J. Mamtora, and Mr. Satyen J. Mamtora. In 1995, it was renamed Transformers and Rectifiers (India) Limited—the TARIL we know today.

By 1998, TARIL had earned ISO 9001-2000 certification from Bureau Veritas for the design, manufacturing, and servicing of distribution transformers, power transformers up to 200 MVA in the 220 kV class, and furnace transformers up to 63 MVA in the 33 kV class. For a young company, this wasn’t just a credential—it was a signal. While many peers stayed in the safer, lower-voltage lane, TARIL was already pointing itself toward the higher-stakes end of the market.

And a culture formed around that choice: frugal, engineering-first, and built for manufacturing reality rather than corporate theater. Gujarat—India’s western industrial heartland—was a natural home. Heavy industry customers were close by, technical talent was available, and the local business environment respected builders. The Mamtora family kept the operation tight, reinvesting into capability instead of appearances.

It wasn’t glamorous. But it was foundational.

III. The IPO & The False Dawn (2006 – 2012)

The mid-2000s were India’s golden years for infrastructure. GDP growth regularly cleared 8%, foreign capital poured into emerging markets, and the country finally looked ready to fix the power shortages that had held back industry for decades.

The government’s 11th Five Year Plan (2007–2012) captured the mood: add 78,700 MW of generation capacity, roughly a 50% jump over the installed base at the time. And every new megawatt needed the same unglamorous supporting cast—transmission lines, substations, and, at every step, transformers.

TARIL didn’t watch this wave from the shore. It paddled straight into it.

In 2006, the company expanded the Changodar plant’s capacity from 4,000 MVA per year to 6,000 MVA. Then, in 2006–07, it acquired the Odhav manufacturing facility that had previously operated as Mr. Jitendra Mamtora’s proprietorship. Two sites around Ahmedabad meant bigger throughput, bigger orders, and the ability to credibly pitch to bigger customers.

And then came the public markets.

On December 28, 2007, TARIL launched its IPO—almost perfectly timed for the “India Shining” era, when infrastructure stories were in fashion and anything tied to power looked like a multi-year runway. The order book was swelling with contracts from state electricity boards and industrial buyers. The narrative was simple: India would build, and TARIL would supply the hardware.

Operationally, the company was stepping up the voltage ladder. It began producing transformers up to 245 kV and executed large orders for GETCO and TNEB. It moved deeper into EHV products, including electric arc furnace and traction transformers. After listing on NSE and BSE, it delivered 132 kV+ transformers in bulk and supplied 400 kV class units for customers like NTPC and PGCIL.

For a brief moment, it looked like a straight line up and to the right.

So TARIL did what many capital-intensive manufacturers do at the top of a cycle: it geared up. The company borrowed to expand, bought land for new facilities, and invested in the specialized equipment needed for higher-voltage work. On paper, it was entirely rational. The grid needed to grow dramatically, and TARIL was building the capability to meet that demand.

Then the trap sprang.

By the end of 2011, India’s power sector was back in a familiar place: financial crisis, barely a decade after the 2001 bailout of state electricity boards. State distribution utilities in several regions were effectively broke—unable to pay suppliers, unable to service debt, and unable to keep the ecosystem moving.

The 2008 global financial crisis didn’t cause all of this, but it made everything worse. Credit tightened just when the sector needed vast amounts of project finance. And the deeper dysfunction became impossible to ignore after the massive 2012 outage that left more than 600 million people without power—an event that put a spotlight on a utility system in disarray, carrying an estimated $70 billion of accumulated debt.

The nightmare twist was that India didn’t just have a “not enough power plants” problem. It had power plants sitting idle because the distribution companies couldn’t afford to buy electricity. Roughly 25,000 MW of capacity was reportedly lying idle for that reason. Under pressure from the finance ministry, banks kept lending into the sector anyway, and by this period Indian banks’ exposure to power had climbed to ₹5.83 lakh crore—about 22% of all outstanding banking loans to industry.

For transformer manufacturers like TARIL, this was catastrophic.

When the utilities went broke, orders didn’t just slow—they disappeared. Payments stretched from weeks into months, sometimes longer. Projects stalled midstream. And TARIL, having expanded capacity and taken on debt for growth, was suddenly staring at the worst possible combination: underutilized factories and rising interest bills.

IV. The "Valley of Death" (2013 – 2019)

The seven years between 2013 and 2019 were TARIL’s near-death experience. This is the stretch where, for most companies, the story ends: demand dries up, debt stays, banks tighten, and the factory turns from an engine into an anchor.

The industry-wide data tells you the direction of travel. In the years leading up to FY14, transformer makers across India saw profitability slide and debt metrics deteriorate. FY15 brought a modest improvement over FY14, but it was the kind of “recovery” that barely registers when you’re still bleeding. The underlying crisis never really let up.

Competition got vicious. Order inflows weakened because the biggest buyers—state power utilities—were financially strained and simply couldn’t execute capex plans the way the country needed. One major reason was technical and mundane, but devastating in its impact: high AT&C losses of around 25%. When a quarter of the power is lost or never paid for, the utility can’t fund upgrades, can’t pay on time, and can’t build the grid it’s supposed to maintain.

At the same time, imports surged. Reduced domestic order flow combined with rising imports—especially in higher kV classes—hit plant utilization hard. And the biggest source of those imports was China, accounting for 39% of total transformer imports in FY14.

That Chinese pressure wasn’t just “competition.” It was existential. Chinese manufacturers had subsidized material prices, export incentives, and low labor costs that Indian players couldn’t replicate. When utilities shifted to open tenders to stretch thin budgets, Chinese suppliers routinely undercut Indian manufacturers by 15–20%. In a business where margins are often decided by a few percentage points, that’s not a haircut. That’s a guillotine.

Then came the working capital trap.

Lower cash accruals, delayed payments from customers—including state utilities and private players—and project execution delays tightened liquidity across the sector. The median gross operating cycle for listed transformer manufacturers stretched from 166 days in FY11 to 240 days in FY14. Companies funded that gap with more bank borrowing, pushing median gearing from 0.27x in FY11 to 0.60x by FY14.

For TARIL, this played out in the most painful way possible. Growth stalled. Profits compressed. The stock collapsed. And the working capital cycle stretched beyond 200 days—meaning TARIL often had to pay for steel, copper, labor, and testing months before a customer paid a rupee back.

This is where the story could have ended. Many competitors didn’t make it through this period—some went bankrupt, others got picked up in distressed sales. The industry had roughly 4.20 lakh MVA of installed capacity, but was running at barely 50% utilization. To keep factories alive, companies cut prices to the bone, erasing the very margin cushion that might have helped them survive.

TARIL lived anyway—not by finding a miracle market, but through grit and a set of pivots that were hard to justify in the moment and obvious only in hindsight.

First: vertical integration. When pricing collapses, the only lever you still control is cost. TARIL initiated backward integration and commissioned fully automated radiator and fabrication units. Making key components in-house wasn’t just about saving money. It also meant tighter control over quality at a time when failures were unaffordable and every warranty claim could become a liquidity event.

Second: exports. With domestic demand weak, TARIL pushed for international certifications and approvals and looked outward for orders. It earned the ‘Best Supplier Award’ from GETCO and expanded exports, including supplying high-capacity transformers to Russia. These were not easy wins—global customers demand rigorous standards and a track record that takes years to build—but they gave the company diversification when the Indian market was effectively frozen.

Third—and most consequential—TARIL doubled down on technical complexity. Instead of retreating into easier, more commoditized products, it leaned further into the high-voltage end of the market where fewer players could compete. The company entered into an arrangement with ZTR, a reputed Ukrainian company, for the manufacture and supply of 765 kV class transformers to PGCIL.

On the surface, it looked like a strange bet. The 765 kV segment was small compared to the mass-market lower-voltage world, and the technical risk was enormous. But Mamtora understood something basic: if you can survive long enough to earn credibility at the highest voltage levels, you don’t just win orders—you change what kind of company you are.

V. The Technical Moat: Breaking the 765kV Barrier (2015 – 2020)

To understand why voltage class matters so much in the transformer business, picture a pyramid.

At the base are distribution transformers—the ubiquitous boxes that step voltage down to household levels. Nearly any competent manufacturer can make them. They’re essential, but they’re commodities, and commodities get priced like commodities.

Climb a level, and the game changes. At 132 kV, you’re supplying substations. At 220 kV and 400 kV, the engineering demands jump: insulation systems get more complex, thermal design gets harder, tolerances tighten, and the cost of mistakes climbs fast. The field narrows, because not everyone can build to that standard consistently.

At 765 kV, you’re at the apex. These are the massive transformers and reactors that sit on India’s national transmission backbone—the electrical highways that move power across regions. TARIL’s product range spans roughly 0.5 MVA to 500 MVA, across voltage classes from 5 kV up to 1200 kV. But in practice, the real “you’re in the club now” threshold is: can you reliably execute at the very top end?

And here’s the thing: the barrier isn’t just engineering. It’s permission.

Power Grid Corporation of India Limited (PGCIL), the central transmission utility that runs much of India’s grid, doesn’t buy 765 kV equipment from just anyone. Vendor qualification is strict, slow, and built around proof—years of it. TARIL stacked credibility points over time: developing India’s first 1200 kV transformer, delivering 170 MVA electric arc furnace units for the MENA region, and expanding its 765 kV capabilities through technology tie-ups with Fuji Electric and ZTR Ukraine.

But the ultimate credibility stamp comes from a test that’s as dramatic as it sounds: the short circuit test.

This is the high-voltage version of a crash test—except you’re not wrecking a car. You’re subjecting a giant, oil-filled transformer to violent electrical forces to prove it can survive real grid faults. If it fails, it doesn’t fail quietly. It can destroy the unit in the lab. That’s why a passed test isn’t just compliance paperwork; it’s a moat.

For years, this created another bottleneck for Indian manufacturers: testing capacity. Because short circuit testing facilities were limited, large power transformers—especially 100 MVA and above—often had to be shipped overseas to labs like KEMA in the Netherlands and CESI in Italy. That meant extra cost, extra logistics risk, and months added to delivery schedules.

Historically, India could handle high-voltage testing for EHV equipment and short circuit testing only up to 84 MVA in the 400 kV class. Anything bigger forced manufacturers and utilities to rely on Europe. That started to change after NHPTL’s facility in Bina began commercial operations in July 2017, enabling domestic testing for transformers rated up to 400 kV class at 500 MVA, and 765 kV class at 315 MVA.

TARIL didn’t just show up to these tests and hope. It invested heavily to get designs ready for the rigors—and then cleared the bar. The company completed a Dynamic Short Circuit Test on a 500 MVA, 400/220/33 kV three-phase auto transformer as per IEC 60076-5 and the latest CEA guidelines. And it later passed a Short Circuit Test on 250 MVA, 2x33/400 kV power transformers—among the highest ratings globally—for solar application transformers in FY 2024.

Each pass compounds. Utilities like PGCIL don’t want a new supplier’s “best effort.” They want demonstrated survival, repeatedly, at the edge cases. Every successful test, every on-grid commissioning, every year without a major failure raises the switching costs. Because when the downside is a catastrophic grid event, nobody wants to be the person who “tried a new vendor.”

By the time the industry cycle finally turned, TARIL wasn’t just alive. It had quietly accumulated what the market values most in high-voltage hardware: a track record at the top of the pyramid. Under management’s stewardship, the company went on to commission high-capacity 765 kV transformer banks, earn awards from PGCIL, GETCO, CPRI, and Tata Power-DDL, secure Star Export House status from the Government of India, and be recognized by Forbes Asia among the “Best Under a Billion” companies. It also posted record revenues exceeding ₹2,000 crore in FY 2024–25—placing it among the leaders in India’s transformer industry.

VI. The Perfect Storm: The Supercycle Begins (2021 – Present)

By 2021, the external world finally started cooperating with what TARIL had been building internally for years. Three forces—each powerful on its own—clicked into place at the same time. And together, they turned a hard-won survival story into a growth story.

The first force was renewables.

The energy transition wasn’t just about putting up solar panels and wind turbines. It was about wiring them into the grid. Every new solar farm and wind installation needs step-up transformers to push power from generation voltage into transmission voltage. And renewables don’t behave like conventional power plants—solar inverters and wind systems create harmonic distortions and operating profiles that punish generic equipment. Utilities and developers needed specialized, inverter-duty transformers that could handle that reality.

This surge was visible everywhere. India installed more solar capacity in the first quarter of 2024 than in any previous quarter, yet commissioning timelines started stretching because transformers became a bottleneck. In the U.S., some manufacturers saw transformer demand jump sharply over the previous two years. And globally, demand for large power transformers—above 100 kV—rose strongly from 2020 and was expected to keep climbing through 2030.

In other words: the grid wasn’t just growing. It was getting more complex. That played directly into TARIL’s DNA.

The second force was “China+1,” plus a broader shift toward deglobalization.

For years, the world patched its transformer supply gaps through imports. Historically, roughly 80% of large transformers were imported from countries like Mexico, China, and Thailand. But as trade tensions escalated and utilities grew uneasy about supply chain security, China’s share of U.S. imports steadily declined—falling from about 21% in 2018 to 13% in 2024, and dropping to just under 10% in 2025.

Utilities still needed hardware. They just wanted it from somewhere else.

That made India—and manufacturers like TARIL—suddenly far more interesting: technically capable, scaled enough to matter, and based in a country viewed as more geopolitically aligned with Western buyers.

The third force was green hydrogen.

This is where TARIL’s original niche came roaring back in a new form. Hydrogen production at scale depends on electrolysis—an electricity-hungry process that needs AC-to-DC conversion done reliably and efficiently. That conversion chain runs through transformer-rectifier systems, and TARIL had been building rectifier transformers long before “green hydrogen” became a boardroom buzzword.

As Jitendra Mamtora, Chairman & Wholetime Director, put it: demand for special transformers for green hydrogen was rising, and while transformer-rectifier equipment wasn’t new, its importance was. In these systems, the transformer isn’t a commodity box—it’s a critical component whose design and efficiency are “carefully and practically considered,” because it feeds directly into the rectifier circuit.

The economics underline why buyers obsess over this hardware. In green hydrogen projects, a large share of cost sits in capital investment and financing—and within that, electrical systems can account for a significant chunk. For a single 100 MW PEM electrolyzer project, that translated into roughly ₹1,000–1,200 crore ($120–145 million) for transformers, rectifiers, converters, switchgear, sensors, and control systems. When the electrical backbone is that expensive, you don’t treat the transformer as an afterthought.

All of this demand showed up in TARIL’s numbers—and fast.

FY 2024–25 became a landmark year. The company recorded its highest-ever production, manufacturing 29,118 MVA, up from 16,425 MVA in FY ’24. Order inflow reached ₹4,504 crore, also a record, and the unexecuted order book stood at ₹5,132 crore as of March 31, 2025—enough to provide clear revenue visibility for the next 15 to 18 months.

The company also raised ₹500 crore through a QIP, won large orders including ₹740 crore from GETCO, and expanded manufacturing capability by 37,000 MVA.

Just as important as growth was what happened underneath it: the balance sheet began to reflect a healthier business. Return on capital employed rose to 22.76% from 6.7% the prior year, and return on investment increased to 23.13%. Cash conversion improved too—debtor days dropped from 142 to 84.8, and working capital requirements fell from 73.6 days to 34.2. In a working-capital-heavy industry, that shift is the difference between “growing” and “growing without breaking.”

And then TARIL crossed another threshold that wasn’t about volume—it was about status.

The company received an HVDC transformer-related order from Power Grid Corporation of India Ltd (PGCIL), making it the first Indian-origin private-sector company to win such an order. TARIL said the contract would bring it into a “unique club of HVDC transformer manufacturers” globally and open major opportunities in the HVDC segment.

After spending a decade fighting to survive—and then years proving it could play at the top end—TARIL was now getting pulled into the next frontier of grid infrastructure.

VII. Competitive Analysis & Strategic Frameworks

By now, the shape of TARIL’s story is clear: survive the bad years, build capability in the hard corners of the market, and be standing when demand snaps back.

But what, exactly, makes that defensible? Two lenses help here. Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers is about durable advantage—why a company keeps winning once it starts. Porter’s Five Forces is about structure—whether an industry lets anyone win at all.

Cornered Resource: Engineering Talent and Institutional Knowledge

Transformer winding is one of those industrial crafts that looks straightforward until you try to scale it. You’re winding thousands of turns of copper or aluminum around a core, with precise insulation, consistent tension, and thermal behavior that has to hold under years of load, vibration, and faults. A lot of it can be measured. Not all of it can be automated. And much of what matters lives in the hands—and habits—of experienced teams.

That’s the cornered resource in this business: skilled people and accumulated know-how. TARIL built its capability to develop power, distribution, furnace, and specialty transformers across three plants around Ahmedabad, supported by world-class infrastructure. The company is run by a team of roughly 1,200 employees whose day-to-day job is not just to build, but to hit quality benchmarks repeatedly—because in high-voltage equipment, “almost right” is just another way to say “failed in the field.”

Switching Costs: The Two-to-Three Year Qualification Cycle

Utilities don’t “trial” transformer suppliers the way a retailer trials a new snack brand.

For high-voltage equipment, qualifying a vendor can take two to three years. The buyer evaluates the factory, audits the quality systems, checks design capability, tests sample units, and often waits for real field performance before opening the door to critical applications. That timeline creates a quiet moat: once you’re approved, you’re very hard to replace.

And the reason is simple. A transformer failure isn’t a warranty inconvenience. It can mean a cascading outage, equipment damage, and reputational fallout for everyone involved. Against that risk, shaving a few percentage points on price is rarely worth it—especially when the “cheaper” option is unproven.

Process Power: Engineered-to-Order at Scale

Most manufacturers prefer made-to-stock products because they scale cleanly. But the most valuable work in transformers often isn’t standardized. It’s engineered-to-order—custom designs built around the customer’s grid conditions, footprint constraints, harmonic profiles, cooling requirements, and performance guarantees.

TARIL’s process power is its ability to do that custom work at meaningful volume, without pricing itself out of the tender. Its portfolio spans single-phase power transformers up to 500 MVA and 1200 kV class, furnace transformers, rectifier and distribution transformers, specialty transformers, series and shunt reactors, mobile substations, and earthing transformers. It’s a pure B2B business serving power generation, transmission, distribution, and industrial customers—markets where “good enough” doesn’t clear the spec.

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants (Low): Entering the high-voltage transformer market is brutally hard, and not just because the factories are expensive. A new entrant needs deep engineering capability, years of process learning, and—most importantly—a track record that convinces conservative buyers. Testing constraints add to the barrier. Historically, many large power transformers, especially 100 MVA and above, had to be sent to overseas labs like KEMA in the Netherlands or CESI in Italy for short circuit testing, adding time, cost, and risk. On top of that, PGCIL’s vendor qualification process effectively locks the top end of the market—especially 765 kV—into a small group of approved players.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Moderate to High): This is the soft underbelly of the business. Copper and electrical steel can make up a majority of manufacturing cost, so swings in commodity prices flow straight through the P&L and contract economics. CRGO steel—the specialized material used for transformer cores—is an even tighter constraint. Supply is limited globally, and India imports virtually all of what it needs. Prime-quality availability remains a major industry challenge, and a large portion of material in circulation is scrap grade.

TARIL has tried to blunt that risk through backward integration. A major step was acquiring a controlling stake in Posco Poggenamp Electrical Steel, strengthening vertical integration in CRGO laminations—an important input for high-efficiency transformers. Posco Poggenamp’s facility, with production capacity of 24,000 MT per annum, is among the largest and most advanced in India.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Moderate): Customers like PGCIL, state transmission utilities such as GETCO and TNEB, and large industrial buyers have real negotiating leverage—big tenders, strict specs, and competitive bidding. But that leverage is constrained by qualification friction, switching risk, and, in the current cycle, a supply shortage that has shifted some pricing power back toward manufacturers.

Threat of Substitutes (Low): There’s no real substitute for transformers in an AC grid. Solid-state transformers and other alternatives exist as concepts and pilots, but they aren’t ready to take over at the power levels and reliability demands of national transmission systems.

Competitive Rivalry (Moderate): India has strong incumbents—CG Power, Siemens India, ABB-Hitachi, and BHEL, among others. CG, for example, offers power transformers from 25 kVA up to 1500 MVA and from 11 kV to 765 kV class, and is among the top manufacturers globally. In a normal cycle, rivalry can devolve into price pressure. But in today’s supply-demand imbalance, competition is less about undercutting and more about who can deliver—on time, at spec, and at scale—allowing margins to stay healthier than in the 2013–2019 grind.

VIII. The Playbook: Lessons for Builders & Investors

TARIL’s journey—from flirting with bankruptcy to landing among the most capable players in a suddenly supply-starved world—offers lessons that go well beyond transformers.

Lesson 1: Survive the Cycle to Win the War

TARIL didn’t win because it made perfect decisions at the top of the cycle. It won because it stayed alive at the bottom.

When India’s power sector buckled between 2013 and 2019, plenty of transformer makers—some with real technical competence—either collapsed or got sold in distressed deals. In that kind of downturn, strategy is secondary to solvency. TARIL’s survival wasn’t the “result” of the story; it was the entry ticket to everything that came after.

The takeaway for builders and investors is simple: in cyclical, capital-intensive industries, capital structure and liquidity are not finance details—they’re the product. A conservative balance sheet in good years buys you the one asset that matters in bad years: time.

Lesson 2: The Lindy Effect in B2B Industrial Hardware

In mission-critical equipment, longevity is the most credible form of marketing.

The Lindy Effect says that the longer something has survived, the longer it’s likely to keep surviving. On a power grid, that becomes brutally practical. Every year TARIL’s transformers run without major failure compounds trust. And when utilities evaluate suppliers, they don’t just compare specifications—they compare scars, references, and field performance.

A long operating history becomes a competitive advantage you can’t buy with a branding campaign.

Lesson 3: Niche Beats Commodity

When the downturn hit, the most brutal fighting happened where products were easiest to compare and easiest to replace.

Commodity distribution transformers got pulled into a race to the bottom, and Chinese imports made that race even uglier. TARIL wasn’t immune to the cycle, but its emphasis on specialty segments—rectifier transformers, furnace transformers, and high-voltage equipment—kept it out of the worst of the lowest-bid carnage. The markets were smaller and the work was harder, but the competition set was thinner, and the customer’s pain from failure was far higher.

In industrial hardware, “niche” often means “protected.”

Lesson 4: Operating Leverage Is a Rocket—and a Trap

This business has enormous fixed costs. Once you’ve built the plant, hired the specialists, and set up the processes, you don’t get to turn the expense line off just because orders slow.

So when utilization rises, profits can jump fast. As TARIL moved from roughly 50% utilization in the bust to 65%+ in the boom, the math turned in its favor. The same overhead got spread across much higher output, and returns surged—ROCE improved to 22.76% from 6.7% versus the prior year, and return on investment rose to 23.13%.

But the warning is embedded in the same mechanism: if demand softens and utilization drops, operating leverage reverses just as aggressively, squeezing margins with the same force that once expanded them.

IX. Bear vs. Bull & The Future

The Bull Case

The bull case for TARIL isn’t complicated. It’s structural.

Transformer demand is rising faster than the industry can reasonably respond—because the world is trying to electrify everything at once, on top of a grid that was already aging and underbuilt. Data centers and AI loads aren’t just “new demand.” They’re dense, round-the-clock demand, and they pull hard on the very part of the system that’s already constrained: transmission, distribution, and the equipment in between.

As one industry view puts it: "The convergence of accelerating electricity demand, aging infrastructure and supply chain vulnerabilities has created constraints that will persist well into the 2030s."

TARIL is behaving like a company that believes that sentence.

It has been expanding capacity aggressively to meet the moment. The plan includes adding 15,000 MVA of low- and medium-rating transformer capacity, a project underway since April 2024. The first phase was expected to be completed by May 2025, adding 7,500 MVA, with the balance slated for Q2 FY26. In parallel, TARIL is expanding EHV transformer capacity by 22,000 MVA at its Moraiya plant in Gujarat, targeted for commissioning around February 2026. Once these projects are fully in place, TARIL expects total transformer manufacturing capacity to rise to 75,000 MVA per year.

Management has also set an ambitious destination: a long-term vision of reaching US$1 billion in revenue within three years.

The Bear Case

The bear case is equally clear: in this kind of business, execution and trust matter as much as capability—and both can get tested.

On November 4, 2025, TARIL was debarred by the World Bank in connection with bribery charges related to a Nigerian power project financed by the World Bank. The debarment bars TARIL for four years, up to June 2029, from participating in World Bank-funded contracts and projects.

TARIL has contested the findings and said it has initiated steps to challenge the matter. The company also emphasized that the debarment is limited to World Bank-funded work and stated: "Just for clarification, the debarment is limited to participation in World Bank-funded projects. The Company currently has no ongoing or pending orders under such projects; therefore, this action has no material impact on its business operations, financial performance, or future outlook."

In describing the underlying transaction, the company said it had received an order worth $24.74 million in FY20 to supply 70 transformers to Nigeria on a CFR basis. The order was executed in FY22, and the company said 90% of payment was received under a letter of credit in the same year. TARIL also noted: "During shipment of last consignment, while it was being transported from Nigerian Port to its Storage, 3 transformers got damaged due to accident."

Separate from that headline risk, the classic transformer-business risks haven’t gone away.

Raw materials remain the soft underbelly. India’s power transformer market still depends heavily on imported inputs like electrical-grade steel and specialty insulating oils. When domestic availability is limited or quality varies, manufacturers are forced into imports—exposing them to global price swings, currency moves, and the kind of supply shocks that turn delivery schedules into guesswork. Geopolitics can amplify that risk quickly.

Then there’s execution risk. TARIL is expanding capacity while running its existing operations at high utilization—exactly the kind of moment when small missteps can compound. Add to that a leadership transition: after the board approved unaudited financial results for Q3 and the nine months ended December 31, 2025, CEO Mukul Srivastava resigned effective January 7, 2026, and Satyen J. Mamtora was appointed as MD & CEO from January 8, 2026. Leadership changes during a high-growth buildout don’t guarantee problems, but they do add complexity.

Critical KPIs to Monitor

For anyone tracking TARIL from here, three metrics tell you whether the story is staying on the rails:

-

EBITDA Margin: Management has guided toward 16–17% EBITDA margins. In Q3 FY26, TARIL reported revenue of INR 704.2 crore and EBITDA of INR 114 crore, implying a 16.2% margin. Holding margins around this range would support the case that backward integration and delivery strength are translating into pricing power. A sustained drop below 14% would be a warning sign—either pricing pressure is back, or raw material costs are leaking through.

-

Order Book Composition (Export vs. Domestic): As of March 31, 2025, TARIL’s order book stood at Rs. 5,132 crore, with exports at around 15%. Management has said it intends to keep exports around 15% and focus on domestic demand where payment cycles are more efficient. A major shift in this mix—toward riskier international work, or away from specialty orders—would be worth watching closely.

-

Working Capital Days: One of the most important improvements in the recent cycle was working capital discipline, with working capital requirements falling from 73.6 days to 34.2. If this reverses, it usually means one of two things: customers are paying slower, or inventory is building faster than shipments. In a business like this, either can become a problem before it shows up anywhere else.

X. Conclusion

The story of Transformers & Rectifiers (India) Ltd is, at its core, a story about endurance.

Jitendra Mamtora didn’t start with a disruptive technology or a revolutionary business model. He started in 1981 with a small repair-and-service operation and a builder’s instinct: learn the equipment from the inside, then move up the value chain. Over time, that instinct turned TARIL into one of India’s largest private transformer manufacturers—without ever chasing the easiest part of the market.

What makes the arc compelling is not that TARIL avoided the pain of the 2010s. It took the full hit of India’s power-sector crisis, in the exact kind of capital-intensive business where downturns can be fatal. Many competitors didn’t make it. TARIL did—and instead of pulling back entirely, it kept investing in capability when the rational move looked like retreat. That decision only paid off later, when the world’s grid spending finally caught up with the energy transition and the shortage arrived for real. Suddenly, the hard products TARIL had spent decades learning to build were the ones everyone needed.

Leadership continuity helped. Satyen J. Mamtora, a second-generation entrepreneur with more than three decades in the transformer and power equipment sector, joined TARIL in 1997 as Director – Marketing. Over the years, he played a central role in expanding market presence, deepening customer relationships, and helping push the company from a regional manufacturer toward a globally recognized player. As Managing Director, he has been responsible for setting strategy and overseeing operations across manufacturing, marketing, project execution, and international expansion.

Even now, the ending isn’t “happily ever after.” The World Bank debarment is a real reputational overhang, and it raises governance questions that management will have to answer with actions, not statements. Competition will also intensify as the transformer market becomes more attractive. And the cycle always comes back around—today’s shortage-driven boom can, eventually, become tomorrow’s overcapacity.

That’s what makes TARIL such a clean “picks and shovels” case study. While attention stays locked on AI chips and solar panels, the heavy infrastructure that makes electrification possible is both essential and scarce. Whether TARIL can keep executing through expansion, maintain trust with conservative buyers, and manage the risks that come with scale will decide if this run becomes a new baseline—or a classic example of what happens when a cyclical business meets peak optimism.

Management expects the order book to grow to ₹8,000 crores by FY26. In an industry where lead times can stretch into years and relationships compound over decades, that matters: the next chapter of this story isn’t a forecast. It’s already sitting in the backlog.

XI. Sources

This story was built from TARIL’s own materials—its company website, annual reports, and investor presentations—along with BSE/NSE regulatory filings. For the broader industry backdrop, it draws on reporting and analysis from Wood Mackenzie, IEEE Spectrum, and POWER magazine. Details on the World Bank action come from the World Bank’s published debarment documentation, and testing context comes from CPRI and related short-circuit testing facility sources. Financial figures were cross-checked against quarterly results and third-party databases such as Screener.in and Groww, along with various financial news reports.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music