Stellaris Venture Partners: Building India's Early-Stage VC Playbook

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

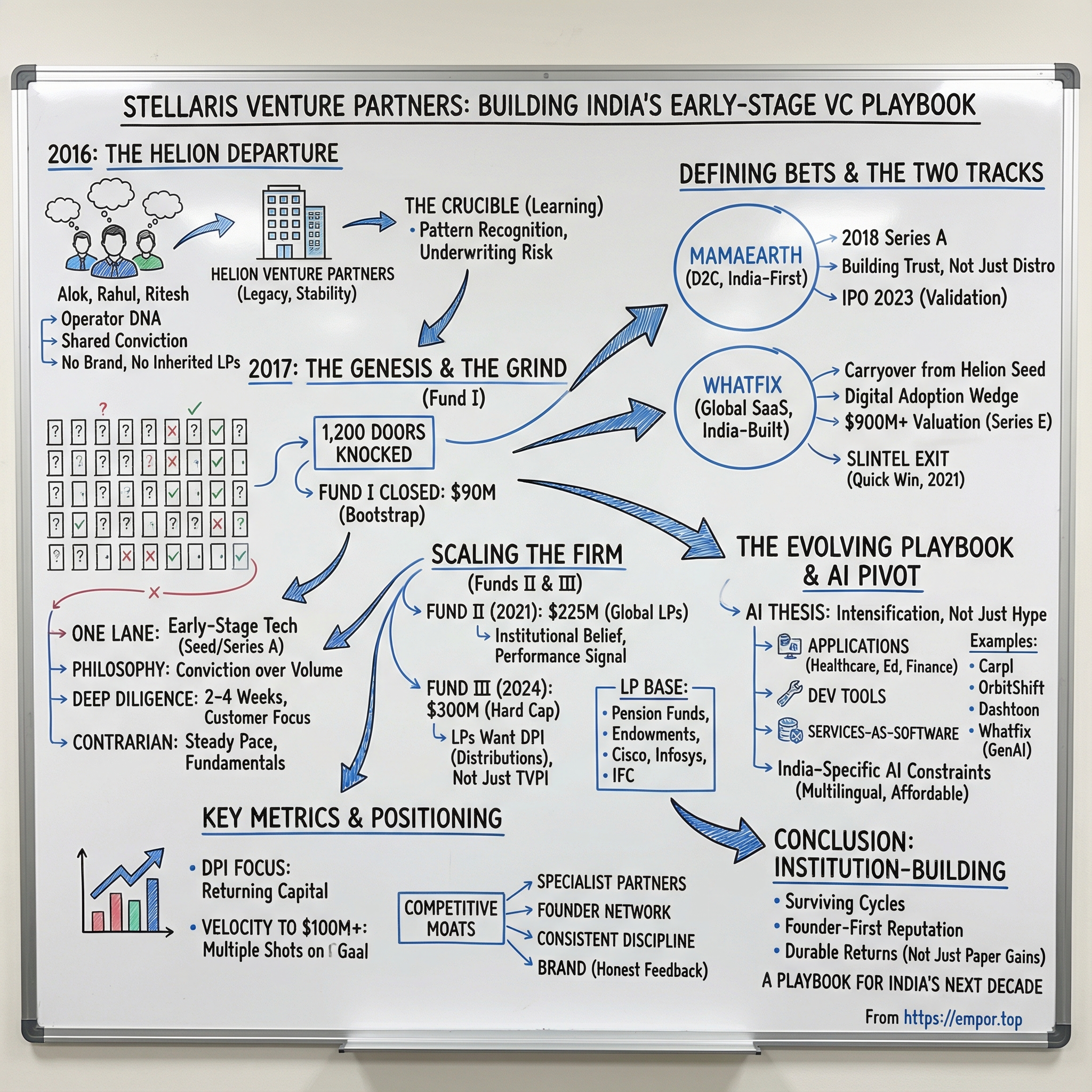

Picture this: it’s 2016. Three venture investors have just walked away from one of India’s most established VC partnerships—and they’re about to start over from zero. No brand-name platform. No ready-made LP roster. No fund already wired and waiting to deploy.

What they do have is rarer: trust in each other, a decade of scar tissue from India’s startup boom, and the willingness to do the most humbling job in venture—ask. Again and again. In their case, about 1,200 times.

That’s the origin story of Stellaris Venture Partners. Today, the firm manages more than $600 million, and in November 2024 it closed its third fund at $300 million—taking total assets under management beyond that $600 million mark.

But the numbers are just the wrapper. The portfolio has produced a unicorn, an IPO, and multiple acquisitions, with companies like Glance, Mamaearth, and Shop101 along the way. The real story is how Stellaris earned its reputation: three partners, building with patience, stubbornness, and a genuinely contrarian streak—helping write what many now see as the modern playbook for domestic, early-stage venture investing in India.

So here’s the question driving this deep dive: how did Alok Goyal, Rahul Chowdhri, and Ritesh Banglani leave the stability of Helion Venture Partners—one of India’s pioneering VC firms—bootstrap a new franchise from scratch, and end up among the country’s most respected early-stage investors?

Along the way, we’ll zoom out too: how India’s VC ecosystem grew from niche to one of the Asia-Pacific region’s most important venture markets; what it actually means to be contrarian when everyone claims they’re hunting the next unicorn; and what it takes to build a venture firm that can survive funding winters and still return real money to LPs.

Because the leap from knocking on 1,200 doors to closing a fund at its hard cap isn’t just a Stellaris story. It’s a window into how India’s venture industry grew up in real time—right alongside them.

II. The Helion Backstory: Where It All Began

To understand Stellaris, you have to start with Helion.

Go back to 2006. India’s startup ecosystem is still more promise than proof. The iPhone hasn’t been announced. Facebook is still mostly a college thing. “Venture capital” isn’t a dinner-table phrase. But a small set of entrepreneurs and investors can see what’s coming: technology is getting cheaper, internet adoption is rising, and a new generation of Indian companies is about to be built from the ground up.

Helion Venture Partners is founded that year, primarily based out of Gurugram. Over time, it grows into an India-focused, early-to-mid-stage firm backing technology-powered and consumer services businesses—everything from internet and mobile to retail services, healthcare, education, outsourcing, and financial services.

For roughly a decade starting in the mid-2000s, Helion becomes one of the most active venture firms in the country, mentioned in the same breath as Nexus Venture Partners, Sequoia India (now Peak XV), and Elevation Capital. It’s not just riding India’s first venture wave. It’s helping define what that wave even looks like.

The results cement the reputation. Helion’s portfolio ultimately includes two unicorns, six IPOs, and dozens of acquisitions, with companies like Flipkart, Myntra, and MakeMyTrip. Flipkart later sells to Walmart for $16 billion. MakeMyTrip becomes one of India’s early, defining tech IPO stories on NASDAQ. These are foundational companies of India’s first internet era, and Helion is in the story early.

It also racks up the kind of liquidity moments that, in that era, felt almost mythical. In 2010, Helion records a successful exit from MakeMyTrip at around 10x. In 2013, Helion Ventures, Seedfund, and Inventus Capital Partners sell their stake in Redbus to Naspers—one of the deals that helps persuade the market that Indian internet startups can actually deliver real outcomes, not just headlines.

But for Stellaris, Helion’s most important output isn’t any single exit.

It’s the people.

The Three Musketeers Emerge

Alok Goyal arrives at Helion as a Partner in January 2013, coming from a very different track than most investors: the operator world. Before venture, he’s the COO of SAP India, after holding leadership roles at SAP starting in 2004. He’s an alumnus of IIT Delhi, the University of Texas at Austin, and INSEAD—and outside work he’s a founding trustee of CAPED, an NGO, and a co-founder of Plaksha University.

The key point isn’t the pedigree. It’s what that background does to his instincts. Alok doesn’t view startups as pitch decks and valuation marks. He’s lived inside real organizations with real customers and real constraints. That “operator DNA” shows up later in the way Stellaris thinks about helping founders, not just selecting them.

Rahul Chowdhri joins Helion in 2007. He’s an IIT Kanpur and IIM Calcutta graduate, with experience across BCG and product roles at Microsoft, MarketRx, and i2 Technologies. By the time he’s a Partner at Helion, he’s already building a portfolio that, in hindsight, reads like the early chapters of modern Indian consumer tech: BigBasket, Simplilearn, Livspace, iD Fresh, and more.

Those aren’t just logos. They’re new behaviors being built—online grocery, ed-tech at scale, home interiors going digital, packaged fresh food becoming mainstream. The pattern Rahul sharpens at Helion is simple, but hard: back founders early who can reshape how India actually lives and buys.

Ritesh Banglani enters venture in 2010 and becomes a Partner at Helion, leading investments including cab aggregator TaxiForSure, stem cell bank Lifecell, and online dating platform Trulymadly. Before investing, he’s in product roles building online and mobile consumer products, including at Cisco and Adobe—shaped by the same IIT Delhi and INSEAD ecosystem.

One outcome becomes especially instructive: TaxiForSure is eventually acquired by Ola, reinforcing a lesson India teaches fast. In winner-take-most markets, timing—when you enter, how long you can hold, and when you exit—can matter as much as the original thesis.

Together, Alok, Rahul, and Ritesh—alongside Helion managing director Rahul Chandra—form the team leading Helion’s investments in that era. And Helion gives them a front-row seat to what venture in India really is: rapid change, lumpy capital cycles, fragile distribution moats, and a long, grinding distance between a seed check and a meaningful exit.

The Crucible: Learning at Helion

Those years become the apprenticeship. How to evaluate founders when data is thin. How to underwrite risk in a market still inventing itself. How to build conviction without needing a crowd to validate it.

And one deal, in particular, becomes a thread that runs straight from Helion into Stellaris.

In 2015, while still at Helion, the team participates in the seed round of Whatfix. At the time, it’s an enterprise software company still working its way toward product-market fit—promising, but far from inevitable.

That investment will later become one of the most important bridges between their old world and the firm they’re about to build.

The Departure Decision

By 2016, something shifts. The three begin planning a new firm: Stellaris Venture Partners.

Leaving Helion isn’t the obvious move. Helion is established, respected, and loaded with institutional momentum. But Alok, Rahul, and Ritesh see room to build something different—something shaped by their own operating and investing scars, and designed to be more focused and more founder-centric from day one.

As is often the case in partnership firms, the precise reasons for the exits aren’t fully public. What is clear is what happens next. Helion co-founder Rahul Chandra goes on to unveil Arkam Ventures for seed and Series A bets. Another co-founder, Sanjeev Aggarwal, forms Fundamentum Partnership to pursue the “middle India” opportunity.

Helion effectively becomes an origin point for a new generation of firms—Stellaris, Arkam, and Fundamentum among them. In hindsight, the split doesn’t shrink the ecosystem; it expands it.

And with that diaspora in motion, the stage is set for the hardest part of this story: three partners walking out without a fund, without a brand, and deciding to build Stellaris from scratch.

III. The Genesis: Founding Stellaris (2016-2017)

There’s something clarifying about starting from scratch. No legacy structures to navigate. No inherited portfolio competing for attention. No LPs anchoring you to “the way things have always been done.” Just three partners, a point of view, and the uncomfortable task of convincing the market they deserved to exist.

In 2017, Ritesh Banglani, Alok Goyal, and Rahul Chowdhri—fresh off their run as partners at Helion—founded Stellaris Venture Partners with a deliberate constraint: pick one lane, and stay in it.

“When we started, we decided to focus on one thing… we didn’t want to do multistage, we didn’t want to do multigeography, we didn’t want to do… non tech,” as one of them put it. Their “one thing” was early-stage technology—seed and Series A—showing up when founders were still at the very beginning of the climb.

That choice wasn’t just philosophy; it was positioning. As larger firms drifted upstream toward later stages, bigger checks, and more “de-risked” companies, Stellaris aimed to own the hardest part of the journey: the messy, high-uncertainty phase where the product is still forming, the go-to-market is still a hypothesis, and the company is more belief than proof.

The 1,200 Doors Story: Fund I’s Grueling Birth

If the strategy was clean, the timing was brutal.

In 2016 and 2017, the mood around Indian venture was shaky. Even insiders were asking whether the model really worked in India—whether enough companies could scale, whether exits would materialize, whether the ecosystem could produce durable returns.

And Stellaris was trying to raise a first fund right into that skepticism.

So they did what first-time firms without institutional momentum have to do: they went door to door. A lot of doors. By their telling, roughly 1,200.

That number isn’t a cute origin-story flourish. It’s months of polite nos, endless “circle back”s, meetings that feel promising until they don’t, and follow-ups that quietly die. It’s also the kind of experience that hardwires empathy into a firm. If you’ve lived the fundraising grind yourself, you don’t hand-wave it when founders go through it—you recognize it in their faces.

Eventually, they closed Fund I at $90 million.

And like most first funds, it didn’t come easily. Even with individual track records, they didn’t yet have a fund-level one. Big LPs might take the meeting, but in that era, they rarely wrote the check for a new India manager.

So Stellaris leaned on a different base of belief: Indian entrepreneurs who already knew the partners from earlier deals. When institutional capital stayed cautious, founders backed the people they trusted—because they’d seen how these investors showed up when things got difficult.

The Philosophy Takes Shape

From the beginning, Stellaris wanted to win with conviction, not volume.

They built a model around doing relatively few investments, but going deeper than most. They also committed to having specialists on the team—people with real depth in specific sectors—so diligence wasn’t a surface scan. It was a serious attempt to understand the market, the product, and the founder.

“We are famous in our industry for very deep diligence,” they’ve said. “Since we also do very few investments, we are very selective. We don’t believe that conviction comes out of thin air.”

In practice, that meant talking to customers and prospects. Pulling in domain experts. Running what they’ve called an “insane number” of reference checks. Spending time with the humans behind the pitch, not just the metrics—because, as they put it, “it’s a marriage and not a transaction.” Typically, it took them two to four weeks to underwrite a deal.

In a market where early-stage can devolve into speed, hype, and FOMO, Stellaris made a quieter bet: rigor plus concentration would compound.

The First Investment: Carrying Forward Whatfix

One of the earliest proof points of that approach came from a company they already knew well.

Back at Helion, the team had participated in Whatfix’s seed round in 2015. When Stellaris formed in 2017, one of their first moves was to back the company again—this time at Series A, led by Stellaris.

On paper, it wasn’t an obvious “safe” bet. Whatfix was building in a category most people weren’t even naming yet: digital adoption. Enterprise software from India still drew skepticism in many global circles, and the path to scale wasn’t guaranteed. Alok Goyal later recalled that at the time, “the story was just not going anywhere.”

But the insight was simple: software is everywhere, and most of it is hard to use. Companies spend enormous time and money training employees and supporting users—not because the software is bad, but because adoption is brittle. Whatfix aimed to make software usable in the flow of work, with on-demand walkthroughs that reduce training and support burden while improving adoption.

For Stellaris, it was exactly the kind of company they wanted to be known for backing: a clear, global problem; a product-led wedge; and founders willing to keep building through uncertainty.

And over time, that carryover decision—from a Helion seed check to a Stellaris-led Series A—became more than a single investment. It became one of the earliest threads of credibility in Stellaris’s new identity.

IV. The Investment Thesis: Building Conviction

Venture capital gets described as pattern recognition. But the real edge is judgment: what you do when everyone is stampeding in one direction, and what you do when the music stops.

Stellaris’s advantage was never about chasing whatever happened to be hot. It was about building conviction the slow way, then holding onto a handful of rules even when the market made those rules feel outdated.

The Contrarian Philosophy

Most funds end up investing to the rhythm of the cycle. In the boom, they hurry. In the bust, they hide. And when a sector gets its moment—consumer, SaaS, fintech, now AI—firms often contort their identity to match the trend.

Stellaris tried to do the opposite: keep a steady hand.

“Over the last seven years, we decided that every year we will do ‘x’ number of investments,” Rahul Chowdhri has said. The firm has made 37 investments across sectors, largely at seed and Series A.

That consistency isn’t just a nice principle. It forces discipline. If you only invest when the market is euphoric, you’re usually paying peak prices. If you stop investing when the market is scared, you miss the vintages that often produce the strongest companies. Stellaris wanted to keep showing up through both.

It also shows up in how they think about concentration. “We don’t want to build a fund where 70% is fintech or 80% is SaaS. And there is a reason,” Alok Goyal has said. Sectors rotate. What looks inevitable in one cycle can get painfully crowded in the next. By not letting the fund become a single-sector bet, Stellaris keeps exposure to multiple ways the future might arrive.

And even when markets were frothy, they didn’t relax their standards. “Even when markets were going ballistic, we asked topline and bottomline questions to the founders,” Chowdhri has said. In an era when growth-at-any-cost was a badge of honor, Stellaris kept pressing on fundamentals—the stuff that suddenly matters again the moment capital tightens.

Sector Focus & Investment Approach

Stellaris is an early-stage venture firm that invests at seed and Series A in Indian technology companies. The lens is broad by design: back companies solving large India-specific problems for consumers and SMBs, and back global software products built from India.

That “and” matters. They’re not trying to pick between two Indias. They’re underwriting both. One lane is local behavior and distribution. The other is global product ambition—companies like Whatfix that can sell well beyond the country’s borders.

Chowdhri’s own framework makes the priorities clear:

“My investment philosophy is to primarily back the founders and less to evaluate the business models they are starting with. I like founders who are first principles-based, iterative and action oriented. I struggle when founders are not able to provide a top-down view on why they are doing what they are doing. My high in investing is when the investee company significantly improves the experience of a large base of customers.”

It’s a clean articulation of what early-stage really is. At seed and Series A, the business model is often still a draft. The founder is the constant. Stellaris optimizes for people who can reason from first principles, move quickly, and stay grounded in a clear “why.”

The "Double Down" Strategy

Conviction at entry is only half the job. The other half is what you do once something starts working.

Stellaris has a specific way of managing winners: de-risk without abandoning the upside.

“Once a portfolio company is marked at 10x or more, Stellaris generally looks to make a partial exit and return 1x-2x of its investment cost. ‘Even if a company is still growing strongly there might still be substantial risk, so taking some cash off the table has served us well,’” Goyal has said.

That’s not how venture is usually mythologized. The industry loves “never sell your winners.” Stellaris is more practical: if you can return meaningful capital while momentum is strong, you protect downside for LPs—and you give the firm more room to keep backing the portfolio for longer.

It’s a philosophy shaped by hard-earned experience: in venture, it’s not enough to be right on paper. The winners have to turn into real liquidity.

V. The Portfolio Defining Moments: Mamaearth & Whatfix

Every venture firm has a handful of bets that do more than return capital. They explain the firm. They become the stories founders retell, LPs point to, and future investments get measured against.

For Stellaris, two companies have come to play that role: Mamaearth and Whatfix. Together, they validate the two-track thesis Stellaris set out with from day one—build in India for India, and build in India for the world.

The Mamaearth Bet: D2C Before It Was Cool

When Stellaris first met Varun and Ghazal Alagh, Mamaearth was still early—built around a straightforward promise: products that parents could trust, without toxins. The business had traction, but the outcome wasn’t pre-ordained. India’s direct-to-consumer playbook was still being written, and plenty of investors weren’t convinced an internet-native brand could become a public-company story.

In 2018, Stellaris backed Honasa Consumer [NSE:HONASA], Mamaearth’s parent company, leading a $4 million Series A.

This wasn’t a moment when the market was falling over itself to fund consumer brands. When Fireside and Stellaris backed Mamaearth—Fireside earlier, and Stellaris in 2018—D2C still sat outside the “obvious venture” categories for many funds.

What Stellaris leaned into wasn’t just a white space in baby care. It was the way the founders built: test quickly, iterate constantly, listen obsessively, and treat trust as the product. Mamaearth started with baby care, but the bigger bet was that a new kind of consumer brand could be built in India—one that grew through online discovery and repeat affinity, not just shelf space.

The macro tailwinds were there if you looked closely. Beauty and personal care was massive, but dominated by incumbents. At the same time, a new generation of customers was finding products through social and buying online. If a brand could win attention and keep it, distribution followed.

Mamaearth’s trajectory made the bet look prescient. Between January 2020 and June 2023, it became India’s most-searched beauty and personal care brand on Google Trends. It reached a $1.2 billion valuation in 2021, and then went public in November 2023.

By the time of the listing, Peak XV was the largest external shareholder at 23.89%, followed by Fireside and Stellaris with 10.34% and 9.45%, respectively. Founders Varun and Ghazal Alagh together held around 37.35%.

The IPO mattered beyond one company. It gave India’s D2C ecosystem something it had been missing: a public-market reference point.

And it mattered even more for Stellaris. As Alok Goyal put it: "Fund I has at least three winners and several others still in the mix. But what really helped this fundraise was Mamaearth going public in November 2023."

Because when Stellaris went back out to raise capital, LPs weren’t just squinting at paper gains. They wanted the thing venture ultimately has to deliver: real liquidity.

The Whatfix Journey: From "Going Nowhere" to $900M Valuation

If Mamaearth proved Stellaris could spot and scale an India-first consumer brand, Whatfix proved something else: a team based in India could build global, category-defining enterprise software—and Stellaris could help it get there.

Whatfix’s arc is long, and it’s not linear. The company pivoted from SearchEnabler to Whatfix, raised early capital, and then kept climbing round by round. Stellaris led the Series A, then stayed involved as the company raised subsequent financings: a Series B with a group including Stellaris, Eight Roads, Cisco, F-Prime, and Helion; then a Series C as Whatfix began to cement itself among top-tier enterprise SaaS players globally; then a Series D led by SoftBank, with the company’s momentum and valuation accelerating; and then a Series E—$125 million led by Warburg Pincus alongside SoftBank.

That Series E valued Whatfix at nearly $900 million.

Mamaearth remains Stellaris’s only IPO to date. But the firm has been clear that it hopes Whatfix—after that Series E at roughly a $900 million valuation—can eventually follow a similar path.

Still, the most telling part of the Whatfix story isn’t the number. It’s the continuity. The partners first backed Whatfix while they were still at Helion, then carried that conviction into Stellaris and leaned in again. In an industry where investors often change their tune with the cycle, this was a rare through-line: see it early, stick with it, and keep showing up.

The Slintel Exit: A Quick Win

Not every strong outcome takes a decade. Sometimes the market delivers a different kind of win: a strategic acquirer with urgency.

That’s what happened with Slintel, a B2B buyer intelligence platform. Stellaris led its seed round in May 2019, after knowing the company for two years. Then, in 2021, Slintel was acquired by US-based 6Sense—meaning Stellaris held the position for about three years.

Goyal has described it as an inbound offer the founder felt he couldn’t turn down—and as a signal of something Stellaris was betting on early: real US strategic interest in Indian software startups.

The Slintel deal became an early liquidity moment for the portfolio, and a reminder that outcomes for Indian SaaS didn’t have to wait for an IPO window. Build something strong enough, fast enough, and global category leaders will come knocking.

VI. Scaling the Firm: Funds II and III

Building a venture firm is its own kind of startup. Fund I can always be explained away—right place, right time, one breakout winner. The harder question is whether you can do it twice, then three times: keep finding great founders, keep underwriting with the same discipline, and keep compounding relationships and outcomes as the firm grows. For Stellaris, Funds II and III were the answer.

Fund II: 2.5x the Size, Global LP Base (2021)

By 2021, Stellaris wasn’t just intact—it had momentum. The team had kept investing through the volatility of 2020, and the early portfolio was starting to show shape.

So they went back to market. Fund II was initially pitched at $160 million. It ultimately closed with $225 million in commitments.

That oversubscription mattered for more than bragging rights. It was a signal that fundraising had flipped: Stellaris wasn’t pushing a boulder uphill anymore. The market was starting to pull them forward.

Just as important was where the money came from. In Fund II, global LPs contributed more than three-quarters of the capital, with fund-of-funds and development finance institutions well represented.

That’s a very different base than Fund I. The first fund leaned heavily on Indian entrepreneurs and individuals who knew the partners personally and trusted their judgment. Fund II signaled something tougher to earn: institutional confidence in Stellaris as a repeatable platform, not just three talented investors.

The portfolio performance helped make the case. Out of the 19 investments in Fund I, nine crossed a $100 million valuation, with several others still trending upward. For a seed-and-Series-A-focused firm, that’s the kind of traction LPs can underwrite.

Fund III: The Validation (2024)

Then came Fund III, raised in a different era.

By 2024, the venture world had sobered up. LPs weren’t paying for potential. They were paying for evidence. Stellaris closed Fund III at its hard cap of $300 million, above its $250 million target.

Reaching the hard cap is one thing. Choosing to stop there is another. It’s an explicit decision to protect the strategy—to grow, but not so fast that the firm becomes a bigger fund running the same early-stage playbook with the same bandwidth.

What really changed in Fund III was what LPs demanded. As Alok Goyal put it: "In Fund II, having good TVPI [total value to paid-in] was enough. This time around, DPI [distributions to paid-in] mattered a lot more."

That line captures the post-2022 reset perfectly. For years, venture lived comfortably on paper gains. Then exits slowed, liquidity got scarce, and LPs went back to the oldest question in the asset class: how much cash have you actually returned?

Goyal described the LP base as "almost entirely institutional, almost entirely US dollar"—with pension funds, endowments, foundations, and a larger number of fund-of-funds.

Stellaris also counts Cisco and Infosys, along with the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation, among its LPs and backers.

The LPs Behind Stellaris

Having Cisco, Infosys, and IFC on the roster isn’t just a badge. It raises the bar. It also pulls Stellaris into a different kind of relationship with capital—one built on governance, reporting, and long-term credibility, not just a great story and a hot market.

Team Evolution

As the capital base grew, the partnership did too.

Stellaris went from three partners to four, promoting Naman Lahoty, a repeat entrepreneur who joined the firm in 2019.

Lahoty brought more founder and operator muscle into the core team. Before Stellaris, he co-founded Helico Foodlabs and Doormint (backed by Helion and Kalaari). He was also an early hire at Toppr, spanning sales, marketing, and content, and worked at Flipkart in 2012—back when it was still becoming the company that would define Indian e-commerce. He’s an alumnus of IIT Bombay.

The firm also deepened the leadership bench: Chetan GMS was named CFO, Praseedha Premnath was elevated to General Counsel, and Vardhan Dharnidharka—an AI/ML specialist formerly based in New York—joined as Principal.

In total, Stellaris grew to a team of 22 people, including six partners.

The team got bigger, but the intent stayed consistent: stay tight, stay close to founders, and keep decision-making concentrated—so early-stage, hands-on investing doesn’t get diluted as fund sizes scale.

VII. The India VC Landscape: Context & Evolution

Stellaris’s story doesn’t really work in a vacuum. The firm didn’t just ride India’s startup boom—it was shaped by every swell and every wipeout. And as it matured, it helped shape the ecosystem right back.

The Macro Environment: India's Startup Ecosystem

By 2024, Indian venture looked like it had found its footing again. Funding rebounded to $13.7 billion—about 1.4x the 2023 level—supported by stronger domestic fundamentals, regulatory tailwinds, and public markets that started to feel meaningfully open again. India reasserted itself as Asia-Pacific’s second-largest VC destination.

Deal activity picked up too: roughly 1,270 deals in 2024 versus about 880 the year before.

But that bounce only makes sense if you remember what came right before it. The correction was violent. Venture funding in India dropped from $25.7 billion in 2022 to $9.6 billion in 2023, echoing the same global risk-off mood.

In plain terms, the market fell more than 60% peak to trough. Companies that raised at sky-high 2021 valuations suddenly struggled to raise follow-on capital at all. Founders who’d only ever known tailwinds had to learn—fast—what a real downcycle feels like.

The Funding Winter & Stellaris's Steady Hand

Stellaris’s edge in that period wasn’t some perfect macro call. It was consistency. While plenty of firms slowed down, Stellaris tried to keep investing at a steady pace.

"Over the last seven years, we decided that every year we will do 'x' number of investments," says Rahul Chowdhri.

And he tells a story that captures how little control VCs actually have over timing:

"So we are always, we have the gift of perfect timing, Siddhartha. Our first fund we tried to raise when nobody was investing in India. Our second fund we plan to launch in April of 2020. March, we were all sitting at home. We had finished building the portfolio. And I remember having the call with one of our largest LPs. That was a call in which I was supposed to ask them, hey, we are starting a new fundraise. Are you guys in? I have the call and the LP on the other side started talking about how they want to delay even the drawdowns of the current fund. I didn't even have the courage to ask him the question about the next fund because they wanted to slow down and look at where else their capital needed to go. So we had to delay the fundraise by a few months."

It’s the most venture kind of whiplash. You walk into a conversation thinking you’re pitching the next chapter. Instead, you realize the current chapter just got riskier—and you may have to protect what you already have before you can even ask for more.

The Rise of Domestic VCs

Stellaris also fits into a bigger structural shift: the rise of homegrown Indian venture firms that can stand shoulder-to-shoulder with global platforms.

New funds, in particular, started showing up in force—accounting for one-third of total VC and growth capital raised, up from 25% in 2023. Many of these were thematic, built around emerging arenas like sustainability, agriculture, defense, sports, and gaming.

That diversification matters. When an ecosystem depends on a small handful of large global firms, capital gets cyclical and concentrated. As domestic managers multiply—across stages, sectors, and styles—the market becomes more resilient. More shots on goal. More local context. More investors built to stay through winters, not just summers.

The IPO Window Opens

Then there are exits—the part of the venture flywheel India spent years trying to get right.

Exit activity held steady in 2024 at $6.8 billion. But the mix shifted in a big way: public market exits rose from roughly 55% to roughly 76% of total exit value over 2023–24, driven by a sharp jump in IPO exit value.

That shift changes the psychology of the entire ecosystem. For a long time, the critique of India was never about building companies—it was about liquidity. You could create real businesses, but outcomes too often depended on finding the right acquirer at the right time.

IPOs change the equation. They create a clearer path to real distributions—what LPs ultimately care about, and what keeps venture firms alive long enough to build enduring franchises.

And for Stellaris, it made something very specific possible. Mamaearth’s listing didn’t just validate one investment. It became proof of something harder: that this firm could help build companies sturdy enough for public markets. And when you’re sitting across the table from the next set of LPs, that kind of proof is worth more than any pitch deck.

VIII. The Current Playbook & AI Pivot

Venture doesn’t let you stand still. What worked five years ago gets copied, competed away, or simply stops working when the platform shifts. The firms that endure are the ones that adapt without losing their center.

For Stellaris, the newest chapter isn’t a sharp turn so much as the same playbook turning up in volume: artificial intelligence has become the most powerful force running through how they think about new investments.

The AI Investment Thesis

The big intensification is AI. On the enterprise side, Stellaris tends to bucket opportunity into three areas: applications, developer tools, and the blending of software and services—what they often describe as “services-as-software.” On the consumer side, they look for AI showing up inside large, everyday categories like healthcare, education, and financial services.

You can see that spread in the portfolio: Carpl, which aims to streamline radiology workflows; OrbitShift, positioned as a co-pilot for account executives in IT services; and Dashtoon, which uses generative AI to create webcomics.

Alok Goyal frames it as a long build, not a sudden pivot:

"In general, if I look at AI as a theme over the last five years, its intensity has actually grown substantially. From our first fund, we had two native AI companies – MFine and Signzy. When we moved to Stellaris fund two, we began to see a lot of AI natives emerging. We also built a thesis at the end of 2020 and published it with the World Bank that said AI was not just going to remain a feature to be added to existing software."

That’s the point: Stellaris isn’t trying to reinvent itself because AI is fashionable. It’s treating AI as a foundational shift across the same kinds of markets they’ve always cared about—and trying to get ahead of the second-order effects.

"We have a massive opportunity in front of us over the next couple of decades," Goyal says in conversation with Shradha Sharma, Founder and CEO of YourStory.

Naman Lahoty breaks that opportunity into two practical changes: AI is altering both how digital products get created and how they get distributed.

On creation, he argues, AI makes entirely new products possible—and makes iteration faster and cheaper. He points to GoodScore, a Stellaris portfolio company that offers a hyper-personalised financial education product to delinquent users to help improve their CIBIL score—something he believes wouldn’t have been feasible without AI.

On distribution, Lahoty sees AI lowering language barriers so products and content can travel further, and lowering production costs so software can reach the next 300 million consumers in India.

That’s the India-shaped AI story Stellaris is leaning into. Not an arms race to build foundation models—an arena that tends to demand enormous capital and extremely scarce technical talent—but applying AI to India’s real constraints: multilingual access, affordable healthcare, financial inclusion, and education at scale.

That same lens carries into generative AI. Rahul Chowdhri has said that while there may not be many Indian startups building foundational GenAI models, Stellaris is focused on companies that use these platforms to deliver a product or service. Several portfolio companies—including Whatfix, LimeChat, and GTM Buddy—are already building with GenAI capabilities.

The Services-as-Software Thesis

One of Stellaris’s more distinctive ideas is “services-as-software”: the belief that AI can take high-quality service delivery and make it feel more like software—repeatable, scalable, and less tightly coupled to headcount.

At the same time, Stellaris has stayed clear-eyed about what traditional SaaS actually demands. Goyal argues that in recent years, too much capital chased SaaS while investors and founders alike forgot that it often scales in a fairly linear way.

"Most software is sold and if it's sold, you require a sales machine, you need to hire salespeople, you need to sell. It's a relatively linear ramp-up that you have to go through. If you plonk too much capital, that doesn't help," he notes.

The argument isn’t anti-SaaS. It’s pro-discipline. As he puts it, "Thoughtful building and utilising the capital well has not happened in the last few years, but we are seeing people rethink the way they are building today and we are very bullish on the evolution of SaaS from India."

Current Portfolio Positioning

With Fund III, Stellaris is continuing to lean into technology-driven businesses—especially across AI, SaaS, consumer technology, and fintech. The newer set of names reflects that: electric vehicle financing company Turno, credit-on-UPI provider Kiwi, and AI-focused SaaS platforms like OrbitShift and CARPL.ai. The portfolio also includes D2C brands like Nestasia and Zouk, along with credit improvement platform GoodScore.

The pattern is familiar by now: diversified across sectors, consistent on the underlying bet. Technology-first companies built on real fundamentals—where AI isn’t a gimmick, but a lever that expands what’s possible.

IX. Key Metrics & Investment Considerations

If you want to understand Stellaris—or any venture firm, really—you eventually have to come back to the unglamorous stuff: what gets returned, how the portfolio is constructed, and what could break.

Fund Performance Indicators

Stellaris has said, “We have provided 1x DPI to their LPs on a scale of 80 million.” In plain terms, that means LPs have already received back the equivalent of all the capital they paid into that fund—while Stellaris still owns meaningful value in the remaining portfolio. For an early-stage fund within roughly seven years of first close, that’s not just a nice chart. That’s proof the machine can produce real liquidity, not only paper gains.

They’ve also shared another signal from Fund I: out of 19 investments, nine crossed a $100 million valuation. The exact outcomes can still move around from here, but the takeaway is simple: Stellaris didn’t need one miracle to make the portfolio work. It created multiple credible breakout candidates.

Portfolio Construction

Zoom out and you can see how Stellaris actually plays the early stage. The firm has made 55 seed investments, with an average round size of about $2.37 million, and 15 Series A investments, with an average round size of about $6.02 million.

Their typical check sizes follow that shape: roughly $0.5–3 million at seed, and about $3–6 million at Series A.

That’s consistent with how they’ve positioned themselves from day one. Stellaris isn’t trying to win by writing the biggest check. It’s trying to be the first high-conviction institutional partner—and then stay close as the company grows.

The KPIs That Matter

If you’re tracking Stellaris over time, two measures matter more than anything else:

-

DPI (Distributions to Paid-In Capital): This is the venture scoreboard that can’t be faked. TVPI can rise and fall with the market, but DPI is cash back to LPs. Stellaris’s emphasis on partial exits once companies are marked up—plus liquidity events like Mamaearth’s IPO—reflects an intentional focus on turning wins into distributions.

-

Portfolio company velocity to $100M+ valuation: In early-stage venture, you’re constantly asking: which companies are breaking out, and how quickly? The nine Fund I companies that crossed a $100 million valuation form the bench of potential future outcomes—whether through IPOs, acquisitions, or secondaries.

Risk Factors

Even with strong signals, there are real things to watch:

-

Fund size progression: Moving from a $90 million Fund I to a $225 million Fund II and then a $300 million Fund III raises the bar. The question is whether Stellaris can keep generating early-stage returns while deploying more capital—without drifting away from the stage focus that made the firm.

-

LP concentration: Twenty LPs account for about 95% of the corpus. Concentration can be efficient, but it also creates re-up risk if a few large LPs change strategy or pull back from the asset class.

-

Key person risk: The Stellaris brand is still closely tied to the founding partners. Promoting Naman Lahoty is a meaningful step toward succession, but the broader transition—from founder-led to fully institutional—remains a journey.

-

Market cyclicality: Venture is cyclical by nature. A portfolio built during the 2021 boom won’t be tested the same way as one built in more conservative markets. The real measure is how the firm performs across cycles, not just inside one.

X. Competitive Positioning & Strategic Framework

By the time Stellaris went out to raise Funds II and III, the market around them had flipped. Early-stage India wasn’t a niche anymore. It was the main stage. More capital, more firms, more founders who knew the playbook. Which raises the obvious question: when everyone wants the best seed and Series A deals, how does Stellaris keep getting into the ones that matter—and keep winning them?

The answer starts with the world they’re operating in.

The Competitive Landscape

India’s early-stage VC ecosystem has matured into a crowded, highly professional arena. Global firms like Accel, Lightspeed, and Peak XV compete aggressively for the same breakout companies. Strong domestic platforms like Blume and Matrix Partners India are right there too. And the top of the funnel has become more structured: angel networks and accelerators are more organized, and the same promising companies are visible to almost everyone who’s paying attention.

In that environment, Stellaris’s edge hasn’t been “access.” It’s what happens after the first meeting—how they build conviction, how they communicate it, and what founders believe the partnership will look like once the money is in the bank.

-

Specialist Partners: Stellaris leans into partner specialization as a credibility engine. Alok is closely associated with enterprise software, Rahul with consumer, and Ritesh with fintech and mobility. At seed, where the data is thin and the founder is the product, that depth matters. Founders tend to choose investors who can argue the market with them, not just price the round.

-

The Founder Network: Stellaris has worked to be hands-on in a way founders actually want. Their model is simple: the partner who leads the deal stays close and gets involved. The Stellaris Founder Network reinforces that by creating structured peer learning, introductions, and practical help—so support isn’t dependent on chance, charisma, or who happens to know whom.

-

Consistent, Disciplined Approach: Stellaris has tried to differentiate by being predictable. They’ve emphasized not chasing every hot sector, maintaining a steady investing cadence through cycles, and asking the uncomfortable questions—about fundamentals, unit economics, and real durability—even when the market is euphoric. Over time, consistency becomes its own form of brand in an industry that often swings with sentiment.

Strategic Moats (Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework)

If you map Stellaris using a “moats” lens, the defensibility isn’t one magic advantage. It’s a set of reinforcing strengths that compound.

-

Network Effects: The Stellaris Founder Network gets more valuable as more strong founders join and contribute. Each success story makes the network more attractive, and increases the odds the next great company shows up via a warm, high-trust introduction.

-

Process Power: After years of concentrated seed and Series A investing, Stellaris has built repeatable ways to evaluate companies, diligence risk, and support founders. That doesn’t look flashy from the outside, but it’s hard to copy quickly because it’s built through reps—and through mistakes you only earn by doing the work.

-

Brand: Within India’s early-stage ecosystem, Stellaris has built a brand around direct feedback, active support, and long-term orientation. At seed, brand isn’t advertising. It’s what founders tell other founders after the board meeting.

-

Scale Economies: Not “bigger is cheaper,” but “bigger is sharper.” A broader base of investments and operating exposure creates an information advantage—more reference points, better benchmarks, and better instincts for what’s real versus what’s just well-presented.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Porter can feel academic in venture, but the forces map cleanly to the pressures Stellaris faces.

-

Rivalry: High, and rising. More funds are competing for the same top founders, and speed has become part of the game. The ecosystem has expanded too, which helps—but at the sharp end of the market, competition is relentless.

-

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate. New funds can appear quickly; credibility can’t. Track records and LP relationships take years to build, and Stellaris’s increasingly institutional base gives it insulation that newer managers don’t yet have.

-

Buyer Power (LPs): Rising. After 2022, LPs shifted from celebrating paper markups to demanding liquidity—more focus on DPI, less patience for narrative. Funds that can point to real distributions negotiate from a stronger position.

-

Supplier Power (Founders): Uneven, but extreme at the top. The best founders have choice, leverage, and often multiple term sheets. Stellaris’s pitch, then, is rarely “we’ll pay the most.” It’s partnership, usefulness, and the promise of showing up for the hard parts.

-

Substitutes: Increasing. Family offices, corporate VC, and accelerator-style models can substitute for traditional venture in certain rounds. Stellaris’s counter-position is that committed, long-duration capital paired with active support remains meaningfully distinct—especially when the cycle turns and “tourist capital” disappears.

XI. Conclusion: What Stellaris Means for India's Venture Ecosystem

In the end, the Stellaris story isn’t really about a fund. It’s about institution-building in an emerging market—what happens when three experienced investors decide to start over, bringing the lessons but leaving the comfort behind.

By any visible measure, it worked. Stellaris raised three funds, grew to more than $600 million under management, helped take a company public, and built a portfolio with multiple meaningful outcomes. More quietly—and more importantly—it earned something that’s harder to manufacture than performance charts: a reputation for being one of India’s most deliberate, founder-first early-stage firms.

But the bigger significance is what Stellaris represents in the ecosystem. Helion became an origin point not just for a portfolio, but for a generation of firms—Stellaris, Arkam, and Fundamentum among them. In hindsight, that diaspora didn’t weaken India’s venture landscape; it widened it.

Venture loves to spotlight the loud moments: unicorn announcements, giant rounds, headline exits. What gets far less airtime is the slow work of building a firm that can survive multiple cycles, keep showing up for founders, and actually return money to LPs.

Stellaris has been making the case that you can build that kind of venture institution in India. Not by chasing every trend. Not by trying to win every deal with the biggest check. And not by relying on frothy valuations to do the talking. But by doing the unsexy work: deep diligence, concentrated bets, steady pacing through up and down markets, and a real bias toward turning paper gains into cash distributions.

As they’ve put it: "It's very rare to find fund globally who in the seventh year on a scale of 1x DPI has provided 1x DPI to their LPs." The point isn’t the brag. It’s the tell. In venture, investing is the easy part; returning capital—while still keeping meaningful upside in the portfolio—is what separates a good-looking deck from an enduring franchise.

India’s startup ecosystem is still maturing, and the next decade will demand more patient capital—investors who understand that enduring companies take time, and who can keep their nerve when the market doesn’t cooperate. Stellaris has put forward a credible playbook for what that looks like.

Whether they can keep that edge as they scale, as AI reshapes the map, and as early-stage competition gets even more intense—that’s the next chapter.

For now, the partners who once knocked on 1,200 doors have something rare to show for it: not just a set of wins, but a firm that looks built to last.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Share on Reddit

Share on Reddit

Amazon Music

Amazon Music