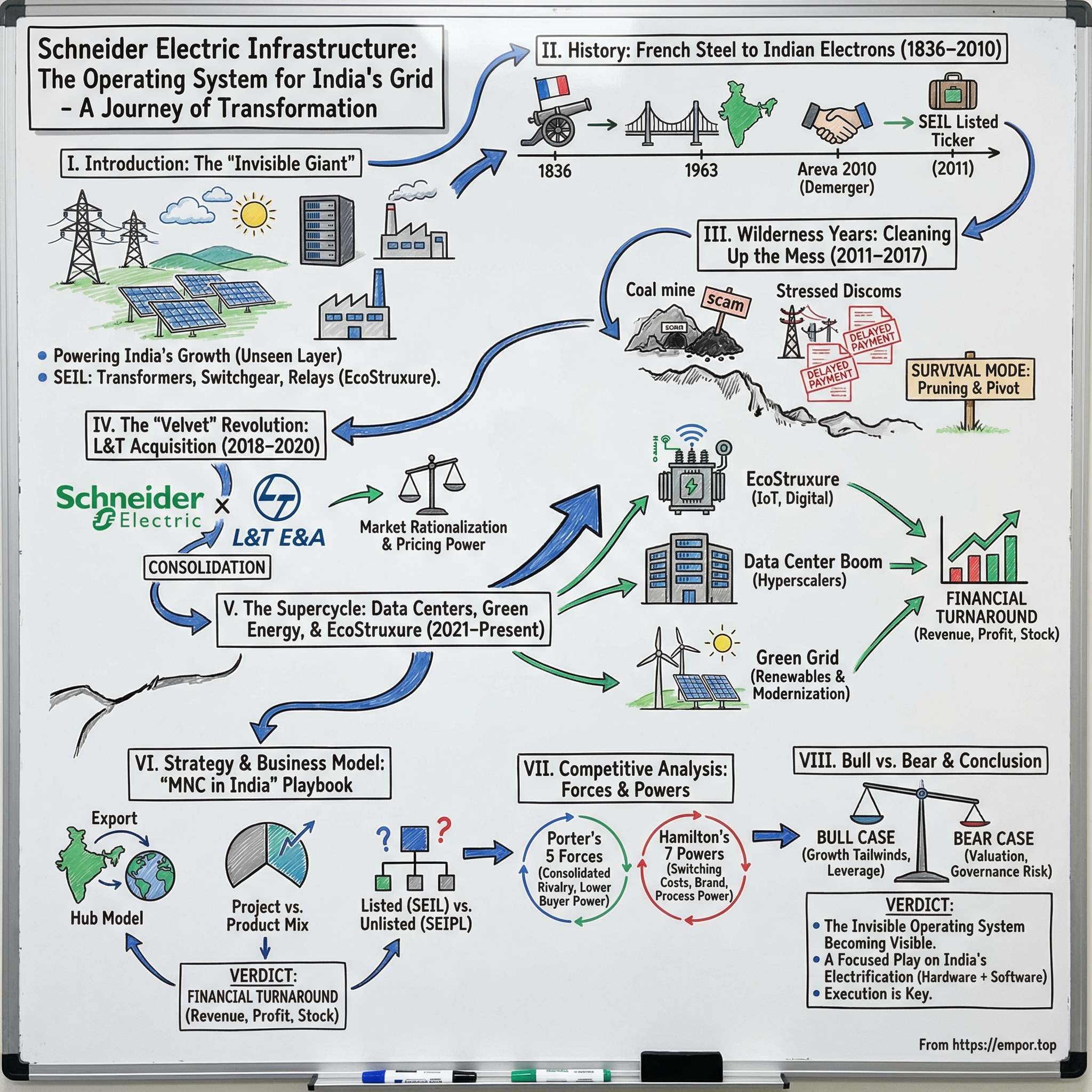

Schneider Electric Infrastructure: The Operating System for India's Grid

I. Introduction: The "Invisible" Giant

Picture this: a gleaming data center in Navi Mumbai, rows of servers humming as they process transactions for a global hyperscaler. Or a vast solar park in Rajasthan. Wind farms off Gujarat’s coast. Clean power pouring into the grid in bursts that are, by nature, unpredictable.

All of this is the part of the “India Story” you can see: the cranes, the capital, the ambition.

What you don’t see is the harder problem underneath. Someone has to manage the flow of electrons. Someone has to make sure that when clouds roll in over a solar farm, Mumbai doesn’t even notice. Someone has to guarantee that when a data center demands massive, uninterrupted power, it gets it—cleanly, safely, and without a flicker.

Increasingly, that someone is Schneider Electric Infrastructure Limited.

SEIL isn’t a household name. It doesn’t sell consumer gadgets. It doesn’t sponsor cricket broadcasts. But its transformers, switchgear, and protection relays sit in substations, factories, campuses, and utility networks—quietly doing the work that makes electrification possible. SEIL builds and supplies the equipment and systems that run electricity distribution: transformers, medium-voltage switchgear, protection relays, and digital grid solutions under Schneider’s EcoStruxure platform.

A useful analogy is the internet. Cisco doesn’t create the content you watch; it routes the traffic that makes everything else work. SEIL plays a similar role for power. It doesn’t generate electricity, but it helps route, control, and protect it. Without that layer, the headline-grabbing buildout—renewables, data centers, industrial expansion—doesn’t scale.

The stakes here are enormous. India is the world’s third-largest carbon emitter and has committed to net zero by 2070. It set an enhanced target at COP26: 500 GW of non-fossil fuel-based energy by 2030. That’s not incremental—it’s a rewiring of the country’s energy system. And then there are data centers: India’s capacity is expected to surge from about 1.4 GW last year to 9 GW by 2030. Every incremental megawatt of always-on computing brings a shadow requirement: substations, transformers, switchgear, protection, and, increasingly, software intelligence to keep the whole machine stable.

Now for the part that makes most investors squint: Schneider Electric Infrastructure Limited—the company listed on the NSE under the ticker SCHNEIDER—is only one piece of a much larger Schneider puzzle in India.

The listed company is a subsidiary of Energy Grid Automation Transformers and Switchgears India Private Limited. Above that sits the global parent, Schneider Electric SE, a roughly €38 billion multinational. Alongside it is the giant unlisted Indian operating arm, Schneider Electric India Private Limited (SEIPL)—the entity that absorbed L&T’s electrical business. And then there’s SEIL itself, focused on medium-voltage distribution and grid automation.

To understand what you actually own when you buy SEIL—and why it can still be one of the cleanest public-market proxies for India’s electrification—you have to understand that web, how it formed, and what it’s been optimized to do.

II. History: From French Steel to Indian Electrons (1836–2010)

The French Origins: Cannons to Circuits

This story doesn’t start in Gurugram. It starts in Le Creusot, in the rolling hills of Burgundy.

In 1836, brothers Adolphe and Joseph-Eugène Schneider took over an iron foundry there. Within two years, they’d founded Schneider-Creusot—an early version of what would eventually become Schneider Electric. They weren’t tinkers. They were industrial empire builders, scaling steel, heavy machinery, and transportation equipment at a time when Europe was being remade by factories and rail.

Then geopolitics intervened. After France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, Schneider expanded aggressively into weapons manufacturing. For decades, Schneider & Cie became synonymous with French military industry: cannons, armaments, specialized alloys, armor plating—industrial capacity pointed outward.

The shift to electricity didn’t happen in a single board meeting. It happened in steps. One symbolic moment came in 1881, when Schneider attended the first International Exposition of Electricity in Paris. The company could see where the world was going.

After World War II, the direction became clearer. Groupe Schneider moved away from weapons and toward rebuilding infrastructure—power, industry, and the systems that keep modern economies running. Over the second half of the 20th century, Schneider assembled its modern identity through acquisitions: Télémécanique, Square D, Merlin Gerin, Modicon—names that, together, built a global footprint in electrical distribution and industrial automation.

By 1999, the company made it explicit. It renamed itself Schneider Electric.

The India Entry: Six Decades of Quiet Building

Schneider’s India story began early, in 1963, through a joint venture with the Tata group. It wasn’t a flashy market entry. It was long-horizon, relationship-heavy, engineering-first growth—the kind that compounds quietly over decades.

In 1995, Schneider Electric established a wholly owned subsidiary, Schneider Electric India Pvt. Ltd. Over the years, it built manufacturing capacity, trained engineers, and became a familiar name to the people who actually buy and run electrical equipment: state electricity boards, utilities, and industrial customers.

By the time India’s economy began accelerating in the 2000s, Schneider wasn’t “entering” the market. It was already embedded in the ecosystem.

The Areva Moment: The Birth of the Ticker

The listed company we’re talking about—SEIL—didn’t come from a clean, conventional IPO. It came from a complicated corporate event in 2010: Schneider Electric and Alstom acquired AREVA T&D.

On 7 June 2010, AREVA T&D’s global activities were bought by a consortium of Alstom and Schneider Electric, in a deal valued at about €2.29 billion. But the headline price wasn’t the interesting part. The structure was.

The business was split. High Voltage Transmission and Power Electronics would go with Alstom. Medium Voltage activities—distribution systems, equipment, and related automation—would sit with Schneider Electric. It was less like buying a company and more like taking it apart with a scalpel.

In India, that meant a legal and operational demerger to separate the transmission side from the distribution side. The company’s board approved the demerger on 28 May 2011, carving out the Medium Voltage activities with effect from 1 April 2011 into a wholly owned subsidiary named Smartgrid Automation Distribution and Switchgear Limited.

It’s a mouthful, but it matters: that entity is the seed of today’s listed company. In December 2011, it was renamed Schneider Electric Infrastructure Limited. Incorporated in 2011 and based in Gurugram, it became the public-market vehicle investors can buy today.

And it was born with baggage.

SEIL inherited serious engineering DNA from the AREVA lineage—hard-won expertise in transmission and distribution. But it also inherited the less glamorous parts of an industrial carve-out: legacy contracts, debt, and operational complexity. This wasn’t a company stepping into the market on its own terms. It was a business spun out of a larger machine, carrying both the strengths and the problems of what came before.

That setup created the opportunity. It also set the stage for the difficult years that followed.

III. The Wilderness Years: Cleaning Up the Mess (2011–2017)

The Crisis

The timing could not have been worse. SEIL arrived as a freshly carved-out, newly listed company just as India’s power sector fell into one of its ugliest slumps in decades. If you were selling equipment to the grid, the years after 2011 weren’t a cycle. They were a graveyard.

The mood turned sharply after the Comptroller & Auditor General’s audit on coal block allocations detonated in the public arena, alleging massive “undue benefits” from allocations made without auction between 2004 and 2009. The “coal scam” wasn’t just political theatre. It froze decision-making across the energy value chain. Projects stalled. Lenders pulled back. Developers waited for clarity that didn’t come.

Then came the legal hammer. As coal allocations were cancelled, power plants and transmission plans that had assumed fuel security were suddenly stranded. Meanwhile, SEIL’s core customers—the state electricity boards and state-run distribution companies—were already in trouble. They were losing money, piling on debt, and increasingly behaving like customers in name only.

By 2022–23, state-owned discoms had accumulated losses of about ₹6.77 lakh crore, with debt crossing ₹7.5 lakh crore. But even in the earlier years, the reality for suppliers was the same: payments stretched out endlessly. When invoices take 180+ days to clear, you aren’t running a business. You’re financing your customers.

The Financial Bleed

So SEIL bled. It got hit from three directions at once: interest costs from inherited debt, thin margins on long-duration government contracts that had been bid in sunnier times, and a buyer base that couldn’t—or wouldn’t—pay on time.

And this isn’t a business where you can simply “tighten belts” and ride it out. Consumer companies can cut ad budgets and wait for demand to return. Power infrastructure doesn’t work that way. You can’t pause a substation mid-build. You can’t renegotiate a state utility contract because the macro got ugly. The commitments are physical, contractual, and unforgiving.

The Survival Strategy

Management’s response was essentially triage. In later years, they described it as “relentless pruning,” and that’s the right image: cutting away low-margin legacy work, shrinking exposure where possible, and swallowing near-term pain to protect the patient.

At the same time, SEIL started laying the tracks for the version of the company that would eventually matter. The pivot was simple to say and hard to execute: move from “selling boxes” to “selling solutions.” A standalone transformer is a product, and products get commoditized. But equipment that communicates, integrates, and can be monitored—gear that fits into a broader grid automation system—moves you into a different category. Less bidding war. More partnership. More value captured.

One more thing kept SEIL alive: the patience of the French parent. In a period when many multinationals either exited India or retreated from public markets, Schneider Electric SE kept supporting the business. The logic was straightforward: India’s need for power infrastructure wasn’t going away. It was just getting postponed, trapped in policy and balance-sheet dysfunction.

These years also nudged SEIL’s customer mix in an important direction. Government utilities remained the center of gravity, but the company began leaning into private industrial customers—buyers who cared about reliability, valued quality over the lowest bid, and, crucially, paid on time.

In hindsight, the most important takeaway is almost unglamorous: the company made it through. It didn’t buckle under debt, broken payment cycles, and a frozen sector. It cut, it shifted, and it waited—just long enough for the environment to change.

IV. The "Velvet" Revolution: The L&T Acquisition (2018–2020)

The Setup

On October 30, 2018, Schneider Electric announced what would become one of the most consequential consolidation moves in India’s electrical equipment industry. The plan, first revealed in May 2018, was simple in headline and massive in implication: Schneider would acquire Larsen & Toubro’s Electrical & Automation (E&A) business for about US$ 1.93 billion, roughly ₹14,000 crore.

For L&T—India’s iconic engineering and construction powerhouse—it was a strategic exit from a unit that no longer fit where the group wanted to go. For Schneider, it was a land grab: scale, distribution, installed base, and a deeper lock on the electrical “plumbing” of India’s industrial economy.

But here’s the detail that matters if you’re looking at the listed stock: this deal did not get dropped into SEIL.

The L&T E&A business was folded into Schneider Electric India Private Limited (SEIPL), the large unlisted operating company in India. SEIPL is owned 65% by Schneider Electric, with Temasek holding the remaining stake. So yes, Schneider acquired L&T’s electrical crown jewel—but it sat inside the unlisted arm, not inside the listed infrastructure entity.

The Regulatory Drama

Then regulators stepped in.

The Competition Commission of India (CCI) looked at the combination and saw a classic antitrust red flag: in low-voltage (LV) switchgear, Schneider and L&T were the top two players by sales and distribution reach. Put #1 and #2 together, and you don’t just gain share—you gain the ability to set the tone of the market.

The CCI didn’t block the transaction, but it didn’t wave it through either. It imposed meaningful remedies designed to keep competition alive. Most notably, Schneider had to reserve part of L&T’s installed capacity to provide white-label manufacturing services to third-party competitors for five high–market share LV switchgear products. In plain English: rivals could buy L&T-made products at a reasonable price and sell them under their own brands, for five years—an attempt to prevent the merged giant from squeezing everyone else out overnight.

After nearly two years of scrutiny, conditions, and then pandemic-era disruption, the deal finally closed in August 2020.

Why This Matters for SEIL

So why spend time on an acquisition that landed in an unlisted subsidiary, when we’re trying to understand the listed company?

Because it rewired the competitive landscape SEIL operated in.

Before the acquisition, L&T was one of the toughest, most relentless price competitors in the market—especially in the kind of large, specification-heavy projects where suppliers are tempted into brutal bidding wars. L&T’s presence shaped customer expectations and often dragged pricing toward “lowest quote wins.”

After the acquisition, that independent competitor was gone. Not eliminated from the ecosystem—absorbed into the broader Schneider family.

The combined Schneider portfolio in India became vast: energy management, low- and medium-voltage switchgear, automation for industry and buildings, and full electrical systems. And with that breadth came something SEIL hadn’t reliably enjoyed in the wilderness years: the ability to price for value, not just survival.

In practice, the Indian electrical equipment market began to look less like a crowded bazaar and more like an oligopoly, with Schneider, Siemens, and ABB as the major gravitational forces. For SEIL, that consolidation mattered even without a direct transfer of L&T’s revenues—because healthier industry pricing and a stronger Schneider footprint tend to lift the entire franchise.

Schneider also played the branding hand carefully. The L&T electrical brand had deep recall in switchgear, so Schneider retained the right to use related brand insignia for a defined period. Over time, the business began operating under the name Lauritz Knudsen—still under Schneider’s umbrella, but positioned distinctly. The idea was straightforward: two brands and two go-to-market motions, covering more of the customer spectrum without forcing Schneider’s core brand into every price point.

And perhaps the clearest signal of what this meant came straight from the top. Schneider’s global CEO said India would become its third-largest business in the world, and one of its four major global hubs for R&D and manufacturing. That wasn’t marketing fluff. It was a strategic declaration.

For SEIL, the inflection was subtle but real: the shift from fighting for share in a fragmented market to operating inside a family that increasingly helped set the standard. When your parent becomes the center of gravity for an industry, some of that pull inevitably reaches you.

V. The Supercycle: Data Centers, Green Energy, & EcoStruxure (2021–Present)

The Hardware-to-Software Pivot

To understand SEIL’s transformation, you have to understand EcoStruxure. It’s Schneider Electric’s open, interoperable, IoT-enabled platform for energy management and automation—built to improve safety, reliability, efficiency, sustainability, and connectivity.

In plain English, it turns electrical equipment from “dumb” metal into connected infrastructure.

Think about a transformer—the gray workhorse sitting in a substation. Traditionally, it does its job silently until it doesn’t. And when it fails, you learn about it the worst possible way: something trips, something burns, and something goes dark.

EcoStruxure flips that. Now the transformer is instrumented with sensors and connectivity. It can continuously report temperature, load, vibration patterns, and other indicators that hint at trouble long before a failure. You stop reacting to outages and start preventing them.

Schneider describes this as the next evolution of EcoStruxure Power: an IoT-enabled system that digitizes and optimizes electrical distribution to make it smarter, faster, safer, and more resilient. The core idea is real-time visibility that turns electrical data into actions—protecting equipment, improving operational efficiency, and strengthening reliability.

And strategically, this is the shift: SEIL moves from being a hardware vendor to a digital solutions provider. The physical equipment becomes the entry point—the trojan horse—for a longer relationship: monitoring, predictive maintenance, software layers, and ongoing services. Instead of a one-time sale, the customer increasingly buys continuous performance.

As Schneider’s Mark Nolan put it: “EcoStruxure Power was originally conceived in response to our customers' requirements for a fully digitized power distribution system, providing valuable energy and power usage insights as well as enhanced resiliency… This latest evolution demonstrates our ongoing commitment to providing customers with the most robust digital ecosystem on the market today.”

Innovation here isn’t just about adding software. It’s also about changing the underlying technology in the gear itself. SEIL’s RM AirSet solution—an SF6-free switchgear technology—won “Most Innovative Product” at the Indo-French Business Awards 2025. That matters because SF6, commonly used in traditional switchgear, is a potent greenhouse gas. The point isn’t a trophy; it’s directionally aligned with where customers and regulators are pushing the industry.

The Data Center Moment

If there’s a single demand shock that explains SEIL’s recent momentum, it’s India’s data center boom.

India’s total data center IT load has doubled in the last four years. S&P Global Commodity Insights estimated data center electricity consumption at about 13 TWh at the end of 2024—around 0.8% of India’s total power demand.

And that’s the warm-up.

Based on pipeline projects and investment announcements, more than 5 GW of additional IT load capacity is expected to be operational by 2030. S&P Global Commodity Insights expects India’s data center power demand to grow nearly five times to about 57 TWh by 2030, taking data centers’ share of electricity demand to roughly 2.6%.

Data centers aren’t like homes or even most factories. Their power needs are obsessive: uninterrupted, stable, high quality. A momentary dip can crash servers. An outage can torch millions in losses. And because the load is so concentrated, a single facility can strain a local network—an average data center can consume power on the scale of an aluminium smelter, or roughly 100,000 homes.

This is exactly where SEIL’s mix of distribution hardware and digital intelligence fits. Hyperscalers don’t negotiate on quality; they specify it. And increasingly, they’re specifying Schneider-grade equipment and systems.

Major global tech companies like Amazon Web Services, Microsoft, and Google have collectively committed more than $2 billion to expand their data center footprints in India. Zooming out, local and global technology firms have announced more than $32 billion in investments over the last two years to expand India’s data center infrastructure. For a company selling the “operating system” layer of reliable power, that’s not just demand—it’s a structural tailwind.

The Green Grid

The second supercycle is renewables.

India’s plan—finalized by the Ministry of New & Renewable Energy in line with the Prime Minister’s COP26 commitment—is to reach 500 GW of installed electricity capacity from non-fossil sources (renewables plus nuclear) by 2030.

But renewables come with a built-in problem: volatility. The sun sets. The wind stalls. Supply swings, even when demand doesn’t.

That’s why India’s renewable buildout isn’t only a generation story. It’s a grid modernization story. Integrating decentralized generation, energy storage, green hydrogen, smart grids, and IoT-based systems is what makes a renewable-heavy grid stable.

Managing that volatility requires exactly the capabilities SEIL sells: smarter distribution, faster protection, better monitoring, and systems that can balance supply and demand in real time. It also requires investment in transmission and storage so intermittent solar and wind can plug into the national grid without breaking it.

Financial Turnaround

When the strategy works, the financials eventually start telling the same story.

SEIL reported robust results for Q2 and H1 FY2025–26, including quarterly revenue of Rs. 35,459.00 lakhs and net profit of Rs. 4,284.00 lakhs. The latest year also saw the company deliver its highest-ever revenue and profit since inception, along with record high free cash flow—evidence not just of growth, but of better execution and cash discipline.

In the same period, SEIL reported that order inflow was up 28% and sales were up 6.6%. It also won the Golden Peacock Award for ESG, and pointed to a positive outlook across power, grid, data centers, renewables, and mobility.

The market has noticed. Over the last three years, Schneider Electric Infrastructure Ltd’s share price rose 374.92% on the BSE. What used to feel like a forgotten, messy carve-out has started to look like a clean, listed way to ride India’s electrification wave.

VI. Strategy & Business Model: The "MNC in India" Playbook

The Hub Model

Schneider Electric doesn’t treat India as just another sales territory. It treats it as a hub—one that can design, build, and ship to the rest of the world.

Looking ahead, Schneider expects double-digit organic sales growth for SEIPL. And it plans to lean harder into India as a core R&D and supply-chain base for Asia Pacific and other emerging markets. That shows up in a very tangible commitment: expanding capacity in India by roughly 2.5x to 3x over the coming years.

SEIL itself sells across 28 states and 6 Union Territories, but it also exports to 44 countries. In the latest year reported, exports were about 15% of total turnover. That matters because it reframes what SEIL is: not just a company riding India’s capex cycle, but a node inside Schneider’s global production network.

SEIL runs four manufacturing facilities across three locations: Vadodara (two units), Kolkata (one), and Chennai (one). These aren’t just places where parts get bolted together. They sit close to engineering and product development—building equipment that works for Indian conditions, but also meets the specs of overseas customers.

The Listed vs. Unlisted Complexity

Now we come back to the part that makes investors uneasy: the relationship between SEIL (listed) and SEIPL (the much larger, unlisted arm).

Schneider’s India business has been putting up strong revenue and margin growth since the L&T Electrical & Automation acquisition, with momentum picking up in the last few years. India is now the Group’s third-largest market and one of its four major hubs. In 2024, SEIPL reported statutory revenues of €1.8 billion (including exports), and total sales in India across subsidiaries were €2.5 billion.

The mismatch is hard to ignore. The unlisted entity is roughly a $2 billion revenue business. The listed entity is closer to $350–400 million. SEIL is the smaller sibling—around one-fifth the size.

That size gap creates real questions for minority shareholders. Will the parent prioritize growth, products, and capital allocation inside the unlisted company? Could the listed company be delisted at a price that doesn’t reflect its long-term value? These aren’t conspiracy theories. They’re standard governance questions whenever you have an MNC with multiple Indian vehicles.

The balancing point is that SEIL sits in a specific lane—medium-voltage distribution and grid automation—while SEIPL is far more weighted toward low-voltage and broader industrial automation. There’s strategic logic to keeping the structures separate. And Schneider’s willingness to fund and stick with the business through the wilderness years signals that the parent plays a long game in India, even when the short game looks ugly.

Project vs. Product Mix

Operationally, SEIL has also been reshaping what it sells—and to whom.

Large, long-duration government projects may look prestigious, but they come with all the classic infrastructure landmines: execution delays, delayed payments, and margins that get squeezed by scope changes and renegotiations. In contrast, private industrial demand and product-led sales—through distributors into factories, data centers, and commercial buildings—tend to move faster, carry less execution risk, and often support healthier margins.

The company’s recent wins show both sides of that strategy. It delivered a fully digitalised transformer to a central utility in India. It supplied AIS switchboards with partial discharge sensors—positioned as an industry first—to a government oil company. And it provided the T500 remote terminal unit for a 2 GW solar project in Gujarat. These are capability statements: proof that SEIL can execute complex, high-spec work, even as it steadily builds a more repeatable, product-driven engine underneath.

VII. Competitive Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

Porter's Five Forces

Buyer Power: Decreasing — For most of its life, SEIL sold into government utilities: the toughest negotiators, the slowest payers, and the biggest enforcers of the L1 “lowest price wins” culture. In that world, differentiation doesn’t get rewarded. Survival does. But that mix is changing. Data centers, private industry, and commercial real estate don’t buy power equipment like a commodity because they can’t afford to. If a critical breaker fails or a transformer trips, the cost isn’t just a repair bill—it’s downtime, penalties, and reputational damage. As the wallet share shifts toward customers who pay for reliability, buyer power comes down.

Supplier Power: Moderate — This is still a metal-and-manufacturing business. Copper and aluminum move, and margins move with them. The difference is that Schneider isn’t a mid-sized local buyer taking whatever the market gives it. The global parent’s scale adds procurement leverage and better risk management than most peers can access. There’s also currency complexity, given the broader Schneider ecosystem and cross-border linkages, but the core point holds: input costs matter, yet SEIL isn’t structurally at the mercy of suppliers the way smaller competitors are.

Rivalry: Consolidated — After the L&T deal reshaped the landscape, competition in Indian electrical equipment started looking less like a street fight and more like a chessboard. The market is dominated by a handful of sophisticated players—Schneider, Siemens, ABB, and a few others. That doesn’t mean the fight disappears; it means it becomes more rational. Fewer players have the incentive to destroy pricing for everyone, and more of the competition shifts to specs, service, execution, and ecosystems.

Threat of New Entrants: Low — You don’t wake up one morning and decide to become a trusted grid supplier. In this category, credibility is built the slow way: certifications, reference installations, track record, service networks, and engineering talent that can support equipment in the field for decades. Utilities and large industrial customers won’t bet critical infrastructure on an unproven brand. Chinese competitors remain a theoretical threat, but in mission-critical applications, trust and supportability often matter as much as the datasheet.

Threat of Substitutes: Minimal — There’s no “alternative” to switchgear and transformers if you want electricity delivered safely and reliably. Renewables change where power comes from; they don’t remove the need to step voltage up and down, isolate faults, and protect networks. Digital systems don’t replace the hardware either—they make it more intelligent, more observable, and easier to maintain.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Switching Costs (HIGH) — Once EcoStruxure is embedded in a plant or utility network, it’s not just a software license—it’s the operating layer. It ties into physical equipment, builds historical performance data, shapes workflows, and trains operators on specific interfaces. Switching isn’t a clean swap; it’s new hardware integration, new software, retraining, and the very real risk of downtime during the transition. That friction is a moat.

Scale Economies (MODERATE to HIGH) — Taken together—listed plus unlisted—Schneider’s India footprint is one of the largest manufacturing and go-to-market platforms in the country. That scale shows up in procurement, in the ability to spread engineering and R&D across a larger base, and in service coverage. Not every individual product becomes dramatically cheaper at higher volumes, but the system-level advantage is meaningful.

Brand (HIGH) — Schneider has made sustainability part of its identity, not just a marketing theme. It was ranked the most sustainable company in Corporate Knights’ Global 100 in 2025, and that kind of signal matters in boardrooms that are chasing ESG targets, green building certifications, and carbon reporting. In deals where the buyer wants a “safe choice” that aligns with sustainability narratives, brand becomes a real edge—not because it sounds good, but because it de-risks the decision.

Network Effects (LOW to MODERATE) — EcoStruxure has a light network effect: more installations can mean more ecosystem partners, more integrations, and more operating data that improves how systems are configured and maintained. But it’s not a runaway flywheel like a consumer social network. Think of it as a steady compounding benefit, not an explosive one.

Process Power (MODERATE) — In grid equipment, execution is strategy. Decades of manufacturing discipline, quality systems, and project delivery muscle are hard to copy and easy to underestimate. Customers remember who shipped on time, who met spec, and whose equipment didn’t fail in the field. That reputation feeds future orders.

Cornered Resource (LOW) — SEIL doesn’t have a single, irreplaceable resource—no exclusive raw material access, no one patent that blocks the industry, no uniquely proprietary dataset that no one else can build.

Counter-Positioning (MODERATE) — SEIL sits at an intersection that’s awkward for specialists to chase. Hardware-only players have to build real software and systems capability. Software-first players have to earn trust in high-voltage, high-stakes electrical infrastructure. SEIL’s medium-voltage and grid-automation focus, paired with Schneider’s digital stack, gives it a position that’s not impossible to attack—but not easy to replicate quickly, either.

VIII. Bull vs. Bear: The Investment Debate

The Bull Case

Structural Growth Tailwinds — India looks like it’s entering a long infrastructure buildout, and electricity demand tends to be the most honest indicator of that momentum. Power consumption isn’t discretionary; it rises with GDP, industrial output, and urbanization. After a strong jump in 2023, demand still grew solidly in 2024, and expectations remain for mid-single-digit growth over the next several years. If India keeps building, it keeps pulling electrons—and SEIL sells the gear and systems that make those electrons usable.

Data Center Supercycle — AI and hyperscale data centers don’t just add demand; they add a new kind of demand: dense, always-on, intolerant of downtime. Analysts expect India’s data center capacity to expand dramatically by 2030, driving a major wave of capex into power infrastructure around these facilities. In that world, SEIL’s positioning matters. If it continues to be a preferred supplier for large, high-spec installations, it doesn’t need to win everything to win big—just enough of the right projects.

Operational Leverage — The wilderness years proved this business can be brutally unforgiving when volumes are weak and costs are fixed. The flip side is powerful: when demand rises, capacity gets utilized, overhead gets absorbed, and profitability can move faster than revenue. The shift from years of pain to record results is the evidence investors point to here—not just growth, but a model that can throw off more cash as scale improves.

Market Consolidation — The post-L&T world is simply a healthier structure for incumbents. Fewer players with credible scale tends to mean fewer irrational bids, more discipline, and better pricing quality. SEIL doesn’t operate in a vacuum; when the market becomes more rational, the entire franchise benefits.

Digital Transformation Premium — The best version of the story is that hardware becomes the wedge, and software plus services become the annuity. If EcoStruxure and digital grid automation keep expanding, SEIL increasingly sells outcomes—uptime, visibility, predictive maintenance—instead of only equipment. That usually means stickier customers, higher margins, and a longer tail of revenue after the initial installation.

The Bear Case

Valuation Concerns — The market is already paying up for this future. With the stock trading at very rich multiples, the margin for error is thin. When expectations are this high, “good” results can still disappoint if they’re not spectacular—and if growth slows even a little, the painful part isn’t always the earnings; it’s the multiple coming down.

Parent Company Risk — The governance overhang is real: SEIL is the smaller listed sibling next to a much larger unlisted India business. That raises uncomfortable but standard questions for minority shareholders. Will the best opportunities, products, and investment flow to SEIPL? And could Schneider Electric SE someday choose to delist SEIL at a price that public shareholders feel doesn’t reflect the long-term potential? These situations have a history in India, and investors ignore that history at their own risk.

Cyclicality Risk — This is an infrastructure-facing business. If capex sentiment turns—because rates rise, a recession hits, or investment pauses—orders slow quickly. This isn’t a “hold your breath and it’s fine” category like staples. In a downturn, the stock can fall harder than the market, because the end-demand it depends on is cyclical.

Customer Concentration — Even with a better private-sector mix, government utilities still matter. And the core issue hasn’t magically disappeared: discom finances remain strained, which can translate into slow payments and working capital stress for suppliers. If collections stretch out or a handful of large customers delay materially, the impact shows up fast—not just in profits, but in cash flow.

Technology Risk — The digital thesis only works if the company executes like a software-and-services organization, not just a manufacturer that added connectivity. That requires different talent, different sales motions, and different customer success capabilities. Many hardware companies struggle with that transition. The risk isn’t whether the idea is attractive; it’s whether the organization can deliver it consistently.

Key KPIs to Monitor

For investors tracking SEIL’s ongoing performance, three metrics matter most:

-

Order Inflow Growth — The order book is the earliest signal. Strong order growth supports the demand narrative; a slide toward low growth is often the first sign that the cycle is cooling.

-

Operating Margin Trajectory — If the mix is genuinely shifting toward higher-value products, digital solutions, and services—and if operating leverage is real—margins should expand over time. If they stagnate, it suggests the business is still fighting the old, low-margin battles.

-

Working Capital Days — This is the silent killer in grid-facing businesses. Improving receivable days usually means a healthier customer mix and stronger execution. Deterioration is a warning that the company is slipping back toward the same utility-dependent working-capital trap it spent years escaping.

IX. Conclusion: The Verdict

SEIL represents something that’s surprisingly hard to find in emerging markets: a focused, investable way to participate in a structural megatrend, run with enough discipline that the story shows up in execution—not just in slides.

India’s electrification isn’t a narrative you have to believe in. It’s math. A country of roughly 1.4 billion people, with per-capita power consumption still well below many global benchmarks, is industrializing, urbanizing, and digitizing all at once. That means more generation, more transmission, far more distribution, and a grid that has to move from “barely coping” to “always stable.” Someone has to build that nervous system. Someone has to keep it from tripping when the load spikes, or when solar output drops, or when a hyperscale data center demands perfection. SEIL is positioned to be one of those someones.

It also earned its position the hard way. This company didn’t glide into a boom. It survived the wilderness years of policy paralysis, stressed utility customers, and punishing working-capital cycles. It cleaned up, cut back where it had to, and then made the more important shift: from selling standalone equipment to selling systems—hardware plus digital intelligence—where reliability, monitoring, and performance become part of the product.

The broader Schneider ecosystem matters here too. The L&T acquisition didn’t land inside the listed company, but it changed the market around it. Competition became more rational, the franchise gained pricing power, and India became more central to Schneider’s global strategy. SEIL, sitting in medium-voltage distribution and grid automation, benefits from that gravitational pull.

None of this removes the risks. The valuation bakes in a long runway of strong growth. The parent–subsidiary structure will always be a governance question that minority shareholders have to keep revisiting. And infrastructure is cyclical by nature—when capex slows, the slowdown arrives quickly and the stock doesn’t wait politely.

But the cleanest way to understand what SEIL is becoming is this: the transformer is the trojan horse. The real product is the intelligence wrapped around it—the software, monitoring, and automation that turns electrical distribution from reactive to predictive. In that light, the Cisco analogy isn’t just clever. Cisco didn’t win because it made metal boxes; it won because it became the layer the internet ran on. Schneider’s ambition is similar: become the operating layer for how power is distributed, protected, and optimized.

If India wants its grid to support AI-era data centers, renewable intermittency, electric mobility, and a manufacturing boom, it has to get smarter—much smarter. SEIL, with EcoStruxure and a deep footprint in the physical infrastructure of the grid, is positioned to deliver that intelligence.

The invisible giant may not stay invisible for long.

X. Investor Resources

If you want to go a level deeper, SEIL’s investor presentations and EcoStruxure product demos are available on the company’s website. They’re the best way to see how the “hardware-to-software” story shows up in what SEIL is actually building and shipping. The company has also been pushing ahead with capacity expansion and rolling out new SF6-free, highly digitalised AirSet products—signals that the innovation agenda isn’t just a slide deck.

SEIL also schedules one-on-one investor and analyst meets in Mumbai. The company notes that no unpublished price-sensitive information will be shared, and the relevant details are available on its website.

This analysis is for educational purposes only. SEIL operates in a sector with real regulatory, cyclical, and execution risks, and any investment decision should be made with appropriate due diligence and, where relevant, in consultation with a qualified financial advisor.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music