Lightspeed India: The Index of the Next Billion

I. Introduction: The "Berkshire of Indian Tech"

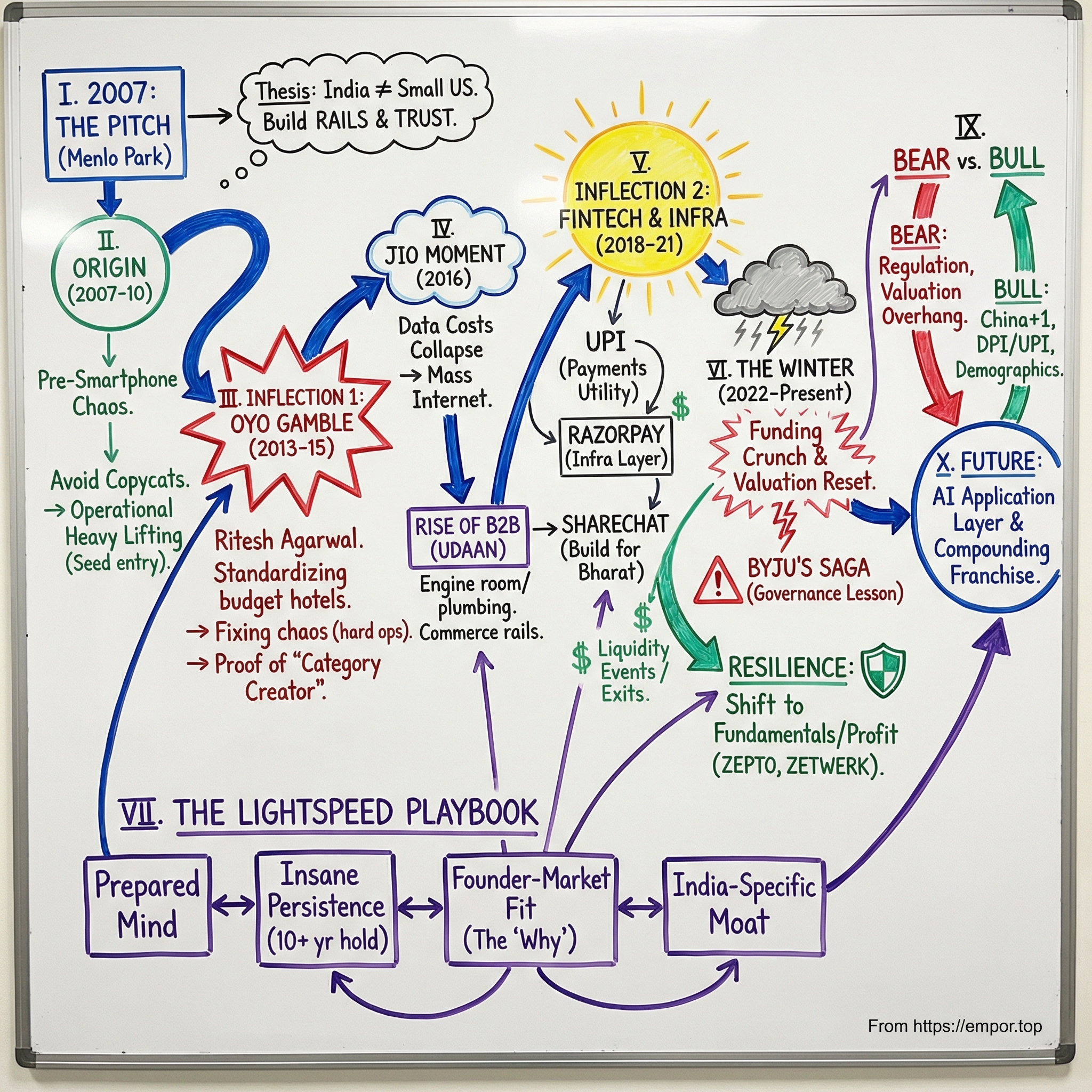

Picture this: it’s 2007, in a conference room in Menlo Park. Lightspeed Venture Partners is hearing a pitch that, on paper, sounds almost reckless. A young investor, Bejul Somaia, wants to build a venture franchise in India—a country where reliable internet access is still rare, logistics are messy, and “trust” in digital commerce is more hope than reality.

The partners listen. They nod. And they write the check.

In 2008, Bejul joined Lightspeed to start the firm’s India practice. What began as a small outpost of a Silicon Valley brand grew into something far bigger: a portfolio that reads like a map of India’s internet economy. OYO. Udaan. Razorpay. ShareChat. Byju’s. Zepto. Along the way, Bejul helped lead early investments in market leaders like India Energy Exchange (NSE:IEX), OYO, Udaan, and MagicPin—and, collectively, those bets have returned over $1 billion to investors.

Now, here’s the thought experiment: if Lightspeed India were a publicly traded stock, it might be the cleanest way to buy the “Indian Internet” story in one ticker. A kind of Berkshire Hathaway for Indian tech—not because it operates these companies day-to-day, but because it’s built a compounding engine for spotting and supporting category creators.

Yes, there are stats you can cite: a 55-person team, 27 partners, 75 companies backed. But those numbers miss the point. The real story is conviction and timing—getting into the right companies early, and staying long enough for the chaos of India to turn into durable advantage. Lightspeed wasn’t just early to India. It was early to the right set of problems.

Bejul brought more than two decades of experience as a builder and early-stage investor, helped expand Lightspeed’s global footprint through new offices and strategic initiatives, and earned recognition like the 2019 Midas Touch award for best venture capital investor in India. But his bigger achievement was helping build one of the deepest benches and strongest venture franchises in the country.

Out of those early years came the thesis that shaped everything: India isn’t a smaller America. It’s a low-trust, high-friction market where the biggest opportunities don’t come from copying what worked in the West. They come from building what India is missing—rails, infrastructure, and institutions—so entirely new businesses can exist on top.

That shift—from “clone the US” to “build for Bharat”—is the throughline of the Lightspeed India story. And for anyone watching from the sidelines, it’s a masterclass in what emerging-market venture really demands: patience, local context, and the nerve to back founders whose ideas sound impossible… right up until they aren’t.

II. Origin Story: Silicon Valley Lands in Delhi (2007–2010)

To understand why Lightspeed worked in India when so many smart investors didn’t, you have to rewind to the country that existed before the smartphone era.

In 2007, internet penetration was still in the low single digits. Phones were everywhere, but they were feature phones—great for calls and SMS, basically useless for building an internet economy. Logistics was a maze of regional operators, inconsistent roads, and local rules that could change district by district. And digital payments? Outside a small slice of affluent urban India, they might as well not have existed.

And yet, global venture firms started circling anyway, hunting for “the next China.” Sequoia had already planted a flag. Accel was building its presence. The simple playbook most outsiders brought was: find the Indian version of a proven U.S. winner, fund it hard, and let scale do the rest.

That playbook would be tempting. It was also wrong.

Lightspeed, for its part, was already in expansion mode. The firm had been founded in 2000 by four enterprise founders who’d worked at Weiss, Peck & Greer and had gone to Stanford together. In 2006, they opened their first international office in Tel Aviv after Yoni Cheifetz joined. India was the next frontier.

Enter Bejul Somaia. He’d studied economics at the London School of Economics, then earned an MBA at Harvard Business School. But the formative chapter wasn’t a degree—it was 1999, when he joined a venture-backed startup in the U.S. as an early employee.

“My journey with venture capital started back in 1999, when I joined a venture-backed startup in the U.S. as an early employee,” Bejul has said. “It changed the arc of my career. I was on a really conventional path up to that point; banking, business school and consulting.”

That operator’s lens shaped how he looked at India. While many investors were busy searching for the “Indian Amazon” or “Indian eBay,” Somaia was asking a more dangerous question: why wouldn’t these models work here?

The first wave of the market answered quickly. The copycat trap swallowed a lot of capital. E-commerce models built on dependable last-mile delivery cracked under India’s logistics reality. Social networks patterned after Facebook struggled to take hold. Payment products designed for credit cards ran into a country that barely used them. These weren’t just execution failures. They were mismatches between assumptions and reality.

Out of that came Somaia’s core insight: in India, you couldn’t just build software and wait for the environment to mature. If the rails didn’t exist—trust, payments, logistics, compliance—you either built around them or helped build them yourself.

That pushed Lightspeed toward a very specific kind of founder: the one willing to do unglamorous, operational work. The kind of business that didn’t just ship code. It trained people, built process, created supply, set standards, navigated regulations—the stuff you normally hope the market “eventually” takes care of.

From the beginning, Lightspeed leaned into the earliest stages. Since starting in India in 2007, it partnered with founders pre-product and pre-traction in many cases, with more than 80% of its capital committed at seed or Series A. The bet wasn’t just on an idea—it was on a team’s willingness to wrestle with India as it actually was.

This “roll up your sleeves” approach became the signature. While others wrote checks and waited for the market to become easier, Lightspeed behaved like India would stay hard—and invested accordingly. In the firm’s own words: in service of bold founders with big ideas, it stands behind companies with high conviction from Seed to Series F and beyond.

By 2010, the mindset was set. The portfolio wasn’t built to mimic Silicon Valley. It was being shaped for a market where infrastructure had to be created, not assumed. The dedicated India fund would come later—$135 million, raised in 2015—but the real foundation was already in place: a willingness to treat India not as a smaller America, but as its own problem set.

And that would matter, because the next decade would transform India’s digital economy faster than almost anyone predicted—and Lightspeed would be sitting right at the center of the blast radius.

III. Inflection Point 1: The OYO Gamble (2013–2015)

In 2013, a nineteen-year-old named Ritesh Agarwal walked into a meeting that would end up defining both his career and Lightspeed India’s reputation. Agarwal had just been accepted into the Thiel Fellowship, the program created by PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel that offered $100,000 to young entrepreneurs willing to skip or leave college to build a company.

Bejul Somaia noticed immediately. “You don’t often see Indian entrepreneurs selected for it, so we took notice of Ritesh,” he said later.

Still, the first pitch didn’t land.

At the time, Agarwal’s startup was called Oravel Stays. The idea was essentially an aggregation marketplace for budget rooms—an Airbnb-ish model adapted to Indian hotels. Somaia didn’t mince words. “I told him it wasn’t the right model for India. The sharing economy model is a challenge in India because of inconsistency in quality and safety,” he said.

This is where the Lightspeed story gets interesting. They didn’t pass and move on. Somaia kept the conversation going—and he pushed Agarwal to go deeper. If India’s hotel market was chaotic, the opportunity wasn’t to list the chaos. The opportunity was to fix it.

Agarwal came back with a different proposition: OYO.

In 2013, after the Thiel Fellowship grant, Oravel was renamed OYO—originally “On Your Own.” But the real change wasn’t the name. The company shifted from aggregating rooms to standardizing them. OYO would take budget hotels and impose a reliable experience: consistent amenities, technology, training, and a single brand guests could actually trust.

That idea clicked. Lightspeed became an early backer, putting in $600,000 in seed capital. Over time, OYO expanded beyond “updating and reselling” rooms, leaning into full rebranding—turning independent properties into OYO hotels.

There’s some timeline messiness in how OYO’s early rounds get described publicly: OYO was founded in 2012, and Lightspeed’s first involvement dates back to late 2012, with later investment participation as the company scaled through subsequent rounds, including by 2014.

But the essence of the bet is clear—and at the time, it looked borderline insane.

Agarwal was proposing to organize India’s unbranded budget hotel market, where quality was inconsistent, safety could be questionable, and there was basically no tech infrastructure. The objections were obvious and brutal: how do you enforce standards across thousands of properties? Why would owners accept outside control? How do you build trust with travelers in a market where trust is the rarest commodity?

Lightspeed saw the mismatch everyone else was stepping around. Indians were traveling domestically at massive scale, and the budget end of the market was a roulette wheel. If OYO could make a cheap hotel feel predictable—clean, safe, consistent—the market wasn’t just big. It was wide open.

And then came the part no pitch deck can capture: scaling hell.

This wasn’t a startup that could win by shipping code faster. It was operational warfare—training staff, setting processes, upgrading rooms, enforcing standards, and building a brand that meant something in a country where brands in that category rarely did. Bedsheets, paint, housekeeping checklists, owner negotiations, constant execution pressure. The exact kind of unglamorous infrastructure-building that Lightspeed’s India thesis had been pointing toward all along.

The results made OYO one of India’s most visible consumer tech stories. The company went on to raise billions across many rounds, bringing in a roster of major investors that included SoftBank Group, Sequoia India, Didi Chuxing, Greenoaks Capital, and others. In October 2019, OYO raised a $1.5 billion Series F led by SoftBank Group, Lightspeed Venture Partners, and Sequoia India.

For Lightspeed India, OYO wasn’t just a big outcome. It was proof of identity: this team could find category creators, not copycats. Not “the Indian version” of a Silicon Valley idea—but the founder willing to solve an India-specific problem by building the missing rails from scratch.

That lesson would become a pattern. And in the next phase of India’s internet economy, it would get even more powerful.

IV. The "Jio Moment" & The Rise of B2B (2016–2018)

On September 5, 2016, Mukesh Ambani walked onto a stage and flipped a switch that rewired India’s internet economy. Reliance Jio launched as a 4G-only network and, for a few surreal months, it treated mobile data like a giveaway. The Welcome Offer ran through the end of 2016: free voice calls, a daily allowance of data at 4G speeds, and just enough generosity to force the entire telecom industry to reset.

The effects showed up almost immediately in one simple metric: usage. India went from being a relatively light mobile-data market to the heaviest on Earth. The price of a gigabyte—which had been a real household expense—collapsed. Suddenly the internet wasn’t a luxury for the urban elite; it was something that could follow you into smaller towns, and then into villages. India’s digital story started to split cleanly into two eras: before Jio and after Jio.

For Lightspeed, this wasn’t just a macro headline. It was the thesis coming true in public. For years, the firm had been telling itself that India’s winners wouldn’t be built by copying Silicon Valley apps—they’d be built by laying rails in a market that didn’t have them. Jio was a rail so big it changed what was even possible.

But it also created the next question: if hundreds of millions of people were now online, what was the most valuable thing to build on top of that connection?

Most investors chased the obvious answer. They flooded into B2C—Flipkart versus Amazon, food delivery wars, social apps battling for attention. Lightspeed made a different move. The firm looked past the consumer and toward the engine room of the economy: the millions of small merchants and neighborhood shops—kiranas—that actually move goods across India.

Enter Udaan.

Udaan was founded in 2016 by Sujeet Kumar, Vaibhav Gupta, and Amod Malviya, all alumni of Flipkart’s early leadership team. They’d seen the magic and the limits of consumer e-commerce up close. Their conviction was that India’s bigger, messier opportunity was upstream: the broken supply chains connecting manufacturers and brands to retailers.

Lightspeed led Udaan’s first funding round in November 2016, investing $10 million at a $40 million valuation. Bejul Somaia framed the bet in the language VCs always use—team, market size, retention, frequency—but the subtext was pure India: this would only work if Udaan could build trust and infrastructure where neither came easily.

Because Udaan wasn’t “just” a marketplace. The app was the easy part.

To make the model real, Udaan had to do the unglamorous work: move inventory reliably across chaotic routes, and extend credit to merchants who couldn’t pay upfront. It had to replace generations of relationship-based wholesale trade with something that felt just as dependable, but ran at internet speed. In other words, it had to build the rails.

As Udaan scaled, it became one of the most heavily funded players in Indian B2B commerce, raising nearly $2 billion. In one later round, Lightspeed invested heavily—filings show roughly $203.5 million of that tranche—alongside Tencent Cloud and Moonstone Investment.

What made the Udaan bet especially important for Lightspeed wasn’t only Udaan’s growth. It was what it signaled about portfolio construction. This was the period when Lightspeed started to look less like a set of disconnected venture bets and more like a system. Logistics and commerce. Marketplaces and credit. Companies that could feed one another demand, data, and distribution. A portfolio that behaved, at least in spirit, like a keiretsu.

Then came the milestone that turned the contrarian thesis into consensus. In 2018, Udaan became the world’s quickest startup to reach unicorn status. And suddenly, “B2B India” wasn’t a niche idea—it was one of the largest stages in global venture.

The Jio moment didn’t just bring India online. It exposed how much of India’s economy still ran on missing infrastructure: distribution networks that leaked efficiency, credit systems that excluded small businesses, supply chains that depended on local middlemen and cash. Lightspeed’s bet was that the real compounding returns wouldn’t come from fighting for consumer attention. They’d come from rebuilding the plumbing underneath the entire market.

And that instinct—to bet on the infrastructure layer instead of the flashy front end—was about to become even more valuable.

V. Inflection Point 2: Fintech & The Infrastructure Layer (2018–2021)

If the Jio moment made the internet cheap, India’s next leap came from somewhere far less expected: policy.

On November 8, 2016—just weeks after Jio’s launch—Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced demonetization, invalidating most of the currency in circulation overnight. The immediate impact was chaos. The lasting impact was clearer: India was pushed toward digital payments faster than anyone had predicted.

But demonetization wasn’t the long-term unlock. The real unlock was UPI.

UPI—the Unified Payments Interface—is an instant payment system and protocol developed by the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) in 2016. In plain terms, it let anyone move money between bank accounts in seconds, using just a UPI ID, whether person-to-person or person-to-merchant. It turned payments into a utility: always on, broadly accessible, and cheap enough to feel like free.

Adoption followed in a way that didn’t look linear—it looked like a step function. Over the years that followed, UPI grew from a promising rail into the dominant one. By the mid-2020s, it accounted for the vast majority of India’s digital payment volume and, remarkably, represented about half of global digital transaction volume.

That created a brutal question for venture investors: if moving money becomes a commodity, where does the profit go?

The obvious answer—back the wallets—turned out to be a trap. Payments apps could pile up users, but they often did it by spending heavily on incentives, only to discover that the underlying act of “paying” didn’t confer pricing power. The better answer was less flashy and far more durable: own the infrastructure layer that businesses depend on, regardless of which wallet the consumer uses.

That’s where Razorpay comes in.

Razorpay positioned itself as a full-stack financial solutions company built for Indian businesses. It started with payments, but the bigger ambition was obvious from the beginning: make it easy for companies—especially the long tail of Indian SMEs—to accept digital payments and then layer on more financial services over time.

Founded in 2014 by Shashank Kumar and Harshil Mathur, Razorpay evolved from a payments gateway into an omnichannel payments and banking platform. Over the years, it raised more than $740 million from investors including GIC, Tiger Global, and Lightspeed.

The strategic idea was classic “sell shovels in a gold rush.” While others competed for consumer mindshare, Razorpay focused on merchants and the plumbing they needed to operate. And in India, plumbing includes regulation. Razorpay had to navigate the Reserve Bank of India’s shifting rules and compliance expectations—work that was slow, complex, and easy to underestimate. Done well, it became a moat.

By FY24, Razorpay reported sharply higher profitability, with profits rising to INR 33.5 Cr, alongside operating revenue of INR 2,475 Cr, most of it from payment aggregation services.

All of this unfolded during what felt like the industry’s “unicorn factory” era. From 2018 through 2021, global interest rates were near zero and capital poured into emerging-market tech. Lightspeed’s portfolio was perfectly positioned for the moment.

ShareChat was the clearest example of what “building for Bharat” actually looked like in product. Founded in 2015 and backed by Lightspeed in 2016, it wasn’t trying to win English-speaking metros. It was building a multilingual, multi-format social platform for the next wave of India: users in smaller towns and villages who wanted to post, watch, and connect in their native languages. Later, Moj became a major short-video platform under the same umbrella.

As ShareChat scaled, Lightspeed kept leaning in. The firm participated with $20 million in a $100 million Series C. In a later round, Mohalla Tech—ShareChat’s parent—raised a $502 million Series E that valued the company at just over $2.1 billion, led by Lightspeed and Tiger Global.

By this point, Lightspeed had something else going for it: liquidity, not just paper marks. Over a single year, the firm made two high-profile partial exits—OYO and Byju’s—that together returned more than $900 million in cash.

The roster read like a greatest-hits list of Indian venture: Byju’s, Innovaccer, Udaan, ShareChat, Razorpay. And the firm kept building its war chest. Lightspeed India Partners announced the close of a $500 million early-stage fund, LSIP Fund IV, alongside a partnership with blockchain firm Lightspeed Faction.

By 2021, Lightspeed India had cemented itself as one of the region’s premier venture franchises. In our thought experiment, a publicly traded Lightspeed India stock would have been hitting all-time highs—buoyed by a portfolio concentrated in some of the most valuable private technology companies in the country.

But markets don’t go up forever. And as every investor learns eventually, gravity always returns.

In 2022, it did.

VI. The Winter, Governance, & Resilience (2022–Present)

The music stopped in early 2022. Interest rates rose, public-market tech valuations cratered, and the “growth at all costs” era ended the way it always does: all at once.

For India’s startup ecosystem, the correction was severe. Late-stage capital—the fuel that had kept mega-rounds and sky-high valuations afloat—fell off a cliff. In 2023, total startup funding dropped sharply from the prior year and sank to the lowest levels since the late 2010s, a stark reversal from the 2021 peak. The takeaway wasn’t the exact totals. It was the new reality: the easy money was gone, and the market was demanding proof—of margins, governance, and staying power.

For Lightspeed, winter wasn’t just about valuation compression. It came with a reputational stress test. Byju’s—once India’s most valuable startup and a marquee Lightspeed portfolio company—became the clearest example of what could go wrong when hypergrowth outruns controls.

By 2023, the edtech giant was in open crisis. Deloitte resigned as auditor. Board members stepped down. Funding tightened. The company faced a combination of pressure points all at once: a post-pandemic demand hangover as schools reopened, accusations of aggressive sales practices, debt, and escalating questions about financial reporting and corporate governance. Aakash Educational Services, part of the broader Byju’s universe, saw similar scrutiny—its auditor BDO (MSKA & Associates), appointed after Deloitte, also resigned amid financial and governance concerns.

Investors, too, were signaling they’d hit their limits. Peak XV Partners cited an inability to influence management on compliance and governance as a factor behind its director stepping away. In June 2023, nominee directors from Prosus, Peak XV Partners, and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative exited the board.

Then came the gut-punch moment of candor. By October 2024, founder Byju Raveendran publicly acknowledged that the company’s valuation had fallen to “zero,” an extraordinary collapse from its earlier peak, and admitted that investor confidence had been shattered.

The Byju’s saga wasn’t just one company’s downfall. It was a hard lesson about governance in emerging markets: even sophisticated investors can find themselves with less control than they assumed, especially when founder power goes unchecked and headline growth masks deeper issues. For the ecosystem, it was a wake-up call. The era of writing checks and hoping the discipline would arrive later was over.

And yet, the same winter that exposed fragility also revealed what was durable inside Lightspeed’s portfolio. Companies built on real demand and improving unit economics didn’t just survive—they used the downturn to separate themselves from the pack.

By 2025, Lightspeed was looking to book profits from several high-profile portfolio companies, including PhysicsWallah, OYO, Zepto, and Zetwerk.

Quick commerce, in particular, emerged as an unexpected bright spot. Zepto—founded in July 2021 by Aadit Palicha and Kaivalya Vohra and headquartered in Bengaluru—became one of the defining stories of the cycle. In August 2023, its Series E round raised $200 million at a $1.4 billion valuation, making it India’s first unicorn of that year. By 2024, as Zepto raised further rounds, the cap table featured major names including StepStone, Lightspeed Venture Partners, DST Global, and General Catalyst. By August 2024, it was valued at over $5 billion, operating more than 250 dark stores across ten metro areas. In its last funding round in October, it was valued at $7 billion, and it planned to raise additional capital.

The narrative across the portfolio shifted accordingly—from hypergrowth to compounders. The new prestige wasn’t “how fast can you grow?” but “can you grow and make money doing it?” Even Udaan, built in the prior cycle, leaned into that framing. “This fundraise is a vote of confidence in the disciplined, margin-focused model we’ve built over the past three years,” said Vaibhav Gupta, co-founder and CEO.

Underneath it all, there was another tailwind building: global capital rebalancing. “If there is a market to invest in the world right now, it is India,” said Rahul Taneja, partner at Lightspeed. He pointed to limited partners reassessing their exposure to China and increasing their weight to India.

Lightspeed kept building through the cycle. The firm had started investing in India in 2007 through its global fund, then launched its first dedicated India and Southeast Asia fund in 2015 with $135 million. It followed with a $275 million fund in 2020, and then its largest yet in 2022 at $500 million.

Winter didn’t reward hype. It rewarded fundamentals. And the Lightspeed franchise that came out the other side was leaner, more skeptical, and—if it had learned the right lessons from Byju’s—better equipped for the next cycle.

VII. The Playbook: The Lightspeed Method

So what actually separates Lightspeed India from the long list of venture firms that tried to “do India” and never quite got it right? After nearly two decades of investing—and more than a few bruises—there’s a pattern to how the team works. Call it the Lightspeed playbook.

Prepared Mind Investing

Lightspeed doesn’t sit back and wait for the next hot round to hit their inbox. They start earlier than that. The team forms a view of where the market is going, then goes looking for the founders building in that direction—often before the category even has a name.

Their thesis, in plain English, sounds like this: partner with founders who have non-obvious insights into a new audience, because they’ve watched real behavior up close—not because a spreadsheet says it should work. Back teams that are relentlessly product-driven, iterate fast, and build habits strong enough to show up in daily engagement and long-term retention. Favor distribution that can scale with low friction and minimal paid growth. And in India, don’t be afraid of models that look “inelegant” on paper—like relying on feet-on-the-street salesforces to reach and serve businesses where digital-only playbooks won’t.

This kind of thesis-first approach is why Lightspeed was already leaning into categories like B2B commerce with Udaan and vernacular social with ShareChat before much of the market saw them as inevitable. By the time everyone else showed up, Lightspeed often already had the relationships—and the trust—with the founders shaping the category.

Insane Persistence: The 10+ Year Hold

Lightspeed also plays a longer game than most. Plenty of investors talk about being “long-term.” Fewer are willing to live through the messy middle—when growth slows, the narrative breaks, and the hard operational work starts.

For over twenty years, Lightspeed has aimed to be the first check and the early partner for companies it believes can be generational. In their own framing: in service of bold founders with big ideas, they stand behind companies with high conviction from Seed to Series F and beyond.

That patience does two things. It signals alignment to founders who aren’t building for a quick flip. And it lets Lightspeed capture the compounding that happens when a company grows from an early idea into an IPO-scale business.

The Founder-Market Fit Filter

This is where the “why” matters as much as the “what.”

Bejul has said he’s drawn to founders who can play the same long game: deeply insightful, unusually clear on the opportunity, and driven by something more than momentum. In meetings, one of his first questions is simple: “Why are you doing this?” If the answer feels thin, it’s usually a pass—because the hard years are too long to run on vibes.

Lightspeed tends to back specific founder archetypes—often aggressive, sometimes polarizing, usually unconventional—because India’s hardest problems don’t yield to conventional approaches. The early bet on Ritesh Agarwal at OYO is the template: a teenage dropout taking on a chaotic, low-trust market with a plan that required operational intensity, not just code.

But underneath the appetite for outliers is a more conservative requirement: trust. “The relationships I’ve been able to build are really the most precious part of this business,” Bejul has said. In a market where governance can make or break outcomes, the partnership itself becomes the asset.

The India-Specific Moat

Maybe the biggest filter of all: Lightspeed India actively avoids “Indian versions” of American ideas. If a model works perfectly in the U.S., it’s often a red flag—not because it can’t work in India, but because it’s either too obvious and already crowded, or it assumes rails India still doesn’t have.

“Over the previous decade, internet and mobile penetration has skyrocketed, the tech talent pool has become deeper, and a new breed of entrepreneurs has emerged – fearless and keen to tackle extremely hard problems,” said Rohil Bagga, an investor at Lightspeed.

So the team leans into problems that are uniquely Indian: fragmented budget hospitality (OYO), inefficient B2B distribution (Udaan), and the unmet demand for local-language content and community (ShareChat). These are categories where imported playbooks don’t translate cleanly—you have to build something indigenous.

That instinct shows up even in smaller, earlier bets. “At Lightspeed, we believe that the future of learning is social & community-based and have been fortunate to partner with Bluelearn from day one,” Rohil Bagga said.

Put it all together, and the playbook looks less like a checklist and more like a worldview: build a point of view early, find founders with earned insight, commit for the long haul, and focus on India-specific problems where the hardest work creates the strongest moats.

VIII. Grading the Business: Power & Forces

So how do you grade a venture firm like it’s a business?

A VC isn’t selling subscriptions. It isn’t shipping product. Most years, it doesn’t even have “revenue” in the way public-market investors would recognize. What it does have is a machine for repeatedly doing three hard things: getting access, picking correctly, and holding on long enough for the bet to mature.

That means the right way to evaluate Lightspeed India isn’t with a P&L. It’s with competitive dynamics.

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis

Competitive Rivalry: High and Intensifying

Lightspeed India plays in one of the most competitive investing markets on the planet. The rivals are exactly who you’d expect: Peak XV Partners (the former Sequoia India), Prosus, SoftBank, Tiger Global, Accel, and a deep bench of domestic funds that have gotten sharper every year.

And when the market turned in 2022–2023, the whole board shifted. Investments by large global VCs in India fell dramatically—by as much as 85%—as capital pulled back and risk tolerance snapped shut.

This is where Lightspeed’s differentiation matters. In a world where most firms can look smart in a boom, Lightspeed’s edge has been built around three things: brand (a history of category-defining bets), empathy (local context and relationships), and patience (staying in the fight across cycles). During the funding winter, when a lot of “tourist” capital retreated, Lightspeed kept deploying—consistently, selectively, and with the posture of a long-term partner rather than a momentum buyer.

Threat of New Entrants

Venture has a funny entry barrier. Writing a first check is easy. Getting into the best companies is not.

Founders don’t take capital from “the market.” They pick a small set of humans they want in the room for the hardest years of their lives. That makes access the real gate—and it’s why a two-decade track record, a dense portfolio network, and long-standing founder relationships compound into an advantage that’s difficult for new entrants to manufacture on demand.

Supplier Power (Founders)

In the best deals, founders have leverage. The strongest companies become auctions, and the scarce resource isn’t capital—it’s allocation.

In that environment, Lightspeed’s portfolio functions like a résumé. A founder looking at OYO, Udaan, Razorpay, and ShareChat isn’t just seeing outcomes; they’re seeing a pattern of what this firm tends to back, and what kind of support it knows how to provide when things get complicated.

Hamilton’s 7 Powers (Applied to the Portfolio)

Network Effects

Some of the most valuable companies Lightspeed has backed get stronger as they get bigger. ShareChat is a clear example: it has grown into one of India’s most popular social platforms, with over 325 million users. More users create more content, which attracts more users—classic flywheel behavior.

You see similar network-shaped dynamics in OYO’s inventory and brand pull, and in Udaan’s buyer-seller marketplace—where liquidity and trust reinforce each other.

Switching Costs

Other parts of the portfolio win in a very different way: once you’re in, it’s painful to leave.

B2B SaaS companies like Innovaccer and Darwinbox embed into core workflows. Over time, they become infrastructure inside an enterprise. Switching stops being a “vendor decision” and turns into an operational risk—expensive, disruptive, and easy to postpone. That’s a real form of durability.

Counter-Positioning

Lightspeed also made a strategic positioning choice that looked subtle in the boom and obvious in the bust.

While “global tourists” like Tiger Global—and SoftBank during its most aggressive phases—optimized for speed and scale, Lightspeed leaned into being a local partner with global reach. When the winter hit, founders learned the difference the hard way: tourists disappear. Local partners stay.

Cornered Resource: The Talent Mafia

Finally, there’s an asset that never shows up on a cap table: people.

The Flipkart alumni who went on to build Udaan. The operators and repeat founders who’ve worked with Lightspeed companies and then show up again with the next idea. That network doesn’t just create deal flow—it creates pattern recognition, hiring pipelines, and operational help that’s hard for competitors to replicate quickly, even with more money.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

If you were tracking Lightspeed India as a hypothetical public entity, the metrics that matter aren’t vanity counts. They’re signals of whether the machine is still working:

-

Deal Access Rate: How often does Lightspeed get a seat at the table for top-quartile deals, and how often does it actually win allocation?

-

Portfolio Company Graduation Rate: How many seed bets earn the right to become real companies—making it to Series B, reaching profitability, or ultimately reaching IPO scale?

-

Exit Multiple/IRR: The scoreboard. Over time, venture success is measured in realized returns. Lightspeed’s reported $1 billion-plus returned to investors from partial exits in OYO and Byju’s offers a concrete benchmark—especially in an ecosystem where paper marks can vanish overnight.

IX. Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bear Case

The skeptical view of Indian tech venture comes down to a handful of risks that don’t show up in the pitch decks—but absolutely show up when it’s time to exit.

Valuation Reset Risk

Even after the winter, a lot of Indian startups still carry valuations that assume a very friendly exit environment. The hard question is whether India’s public markets are deep enough to digest a wave of unicorn IPOs at attractive prices. If the IPO window stays shut—or opens only a crack—returns don’t disappear, but they do get delayed. And in venture, time is a tax.

Regulatory Unpredictability

India’s regulatory environment can feel like driving on a road where the speed limit changes without warning.

Crypto is the cleanest example: effectively banned, then partially unbanned. Gaming taxes shifted dramatically. E-commerce rules have created recurring uncertainty for foreign investors. Fintech regulations keep evolving as the RBI tightens and clarifies its stance.

To be fair, there have also been meaningful positive moves—policy reforms like eliminating the angel tax, reducing long-term capital gains tax rates, removing the National Company Law Tribunal process, and simplifying foreign venture capital investor registrations have signaled momentum for the startup ecosystem. The risk is reversals. In India, regulation can be both a tailwind and a trapdoor.

Key Man Risk

Like most top venture franchises, Lightspeed’s edge isn’t just capital—it’s people. The firm has built a deep team over time, but relationships and reputation still matter enormously for access and founder trust. Any fund that’s closely associated with a small set of key partners carries concentration risk, even if the bench is strong.

The Byju’s Overhang

Governance failures don’t stay contained to one company. They spill outward—into reputation, into founder perception, into how limited partners and public markets think about the whole ecosystem.

Byju’s raised uncomfortable questions about investor oversight and the limits of VC governance in founder-controlled companies. Lightspeed wasn’t alone in backing the company, but the episode remains a blunt reminder: even elite investors can be wrong, and when they are, it can take years to fully wash off.

The Bull Case

The optimistic view is that India is still early—and the forces pushing it forward are structural, not cyclical.

The China+1 Opportunity

Limited partners have been reassessing exposure to China and increasing their weight to India. And if global capital is looking for a market with real scale, a massive domestic economy, and the potential to produce enduring tech giants, India is the only credible alternative. That reallocation doesn’t just help a few startups raise rounds—it can change the baseline for the entire ecosystem.

Digital Public Infrastructure

India has built digital rails that are hard to overstate. UPI now accounts for roughly 85% of all digital transactions in the country and powers nearly half of global real-time digital payments.

And it’s not just UPI. Aadhaar for identity. ONDC for commerce. These platforms don’t guarantee winners—but they dramatically lower the friction of scaling. In much of the emerging world, companies have to build around missing infrastructure. In India, more of that infrastructure is becoming a shared utility.

Demographics

India has the world’s youngest major population. The median age is about 28, compared with about 38 in both China and the United States. That’s not just a statistic—it’s a long runway: more workers entering the economy, more consumers moving up the income curve, and more years of compounding growth ahead.

The Recovery Is Underway

After the pullback, the data started pointing up again. In 2024, India’s venture funding rebounded to $13.7 billion, about 1.4 times 2023 levels, supported by strong domestic fundamentals, progressive regulatory reforms, and improving public market sentiment—helping India hold its place as Asia-Pacific’s second-largest VC destination.

Exits held up too: 2024 exit activity came in at $6.8 billion. And importantly, more of that value came through public markets. Public market exits rose from roughly 55% to roughly 76% of total exit value over 2023–24, driven by a sharp surge in IPO exit value—helped by rising liquidity, a recovery in key tech stock valuations, regulatory reforms, and a backlog of companies waiting for the window to reopen.

X. Conclusion & The Future

Looking out over the next decade, the India opportunity is shifting again—just like it has at every major turning point in this story.

The first wave was about building rails: payments, logistics, digital identity. The second wave was about scale: companies learning how to serve hundreds of millions of newly connected Indians. Now the third wave is taking shape, and it’s about intelligence—what happens when software stops being static and starts adapting, predicting, and working on your behalf.

That’s why generative AI at the infrastructure layer is so exciting. India has one of the largest developer bases in the world—about 9 million developers—and a deepening bench of software founders who’ve already proven they can build through constraint.

At the same time, it’s worth being clear-eyed about where India is—and isn’t—likely to win. India probably won’t build the next frontier foundational model. That game rewards extreme concentration of capital and compute, and it currently tilts toward the U.S. and China. But India may become the world’s best proving ground for applying AI to real problems at massive scale—because the country already has what many markets don’t: widespread digital rails and enormous, diverse demand.

In other words: India doesn’t need to win the “who builds the biggest model” contest to win big. It can win by becoming the place where AI gets turned into products that actually work in the messy real world—across healthcare, education, financial services, and agriculture.

You can see Lightspeed leaning into that future. Lightspeed Ventures launched an accelerator program, India Ascends 2026, to back under-25 Indian founders building R&D-first tech startups.

For Lightspeed India, the method stays the same even as the categories change: find founders tackling uniquely Indian problems, stay with them for the full journey, and keep betting on the unglamorous infrastructure that becomes everyone else’s advantage later. Over nearly two decades, that approach has become more than a set of good investments. It’s become a franchise—one that, at its best, compounds through cycles.

The broader market backdrop helps too. The IPO environment was expected to stay constructive in 2025, with M&A activity supporting liquidity. India has continued to solidify its position as Asia-Pacific’s second-largest VC market, with startups pushing into AI, SaaS, fintech, and consumer tech.

Funding momentum has followed. Indian startups raised over $12 billion in 2024, up about 20% from the year before. Projections suggested that could climb to roughly $15 billion by the end of 2025.

Which brings us back to the investor’s question. It isn’t whether India matters. It’s how to get exposure.

If you’re looking for a proxy to the Indian internet economy, Lightspeed’s portfolio is about as concentrated a bet as you can make on the structural transformation of the world’s largest democracy—whether through direct LP commitments, owning portfolio companies as they list, or simply studying the pattern and applying the lessons elsewhere.

The next billion internet users aren’t coming from the West. They’re already online in India. And more and more, the infrastructure—and now the intelligence—serving them is being built by companies Lightspeed chose early and stayed with. For patient capital with a long horizon, that’s still one of the most compelling compounding stories in global technology.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music