Infosys: From ₹10,000 to Global IT Powerhouse

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

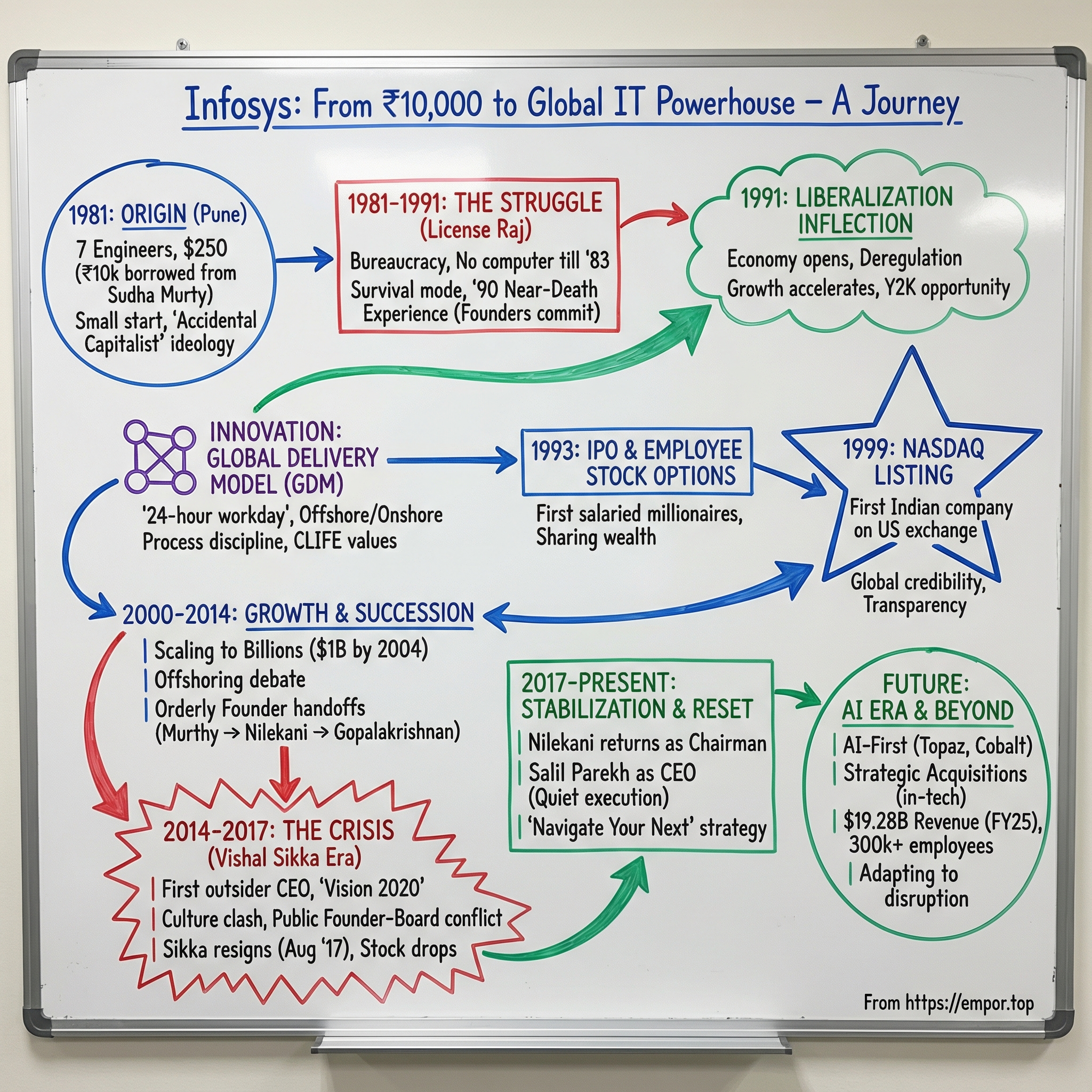

It’s 1981. Pune is wet with monsoon rain, and in a small room seven engineers are about to do something that, on paper, makes almost no sense. They’ve just left Patni Computer Systems. They’ve scraped together about $250 between them. And they’re signing the documents to incorporate a new company: Infosys Consultants Private Limited.

Their starting capital is ₹10,000—money Narayana Murthy borrowed from his wife, Sudha. It’s the kind of sum that wouldn’t cover a decent laptop today. And yet, over the next four decades, that tiny stake grows into one of the world’s most valuable technology companies, with a market cap that has at times topped $80 billion.

The question that powers this whole story is simple to ask and hard to explain: how did a group of middle-class engineers in socialist India build a company that helped invent a new industry—and, in the process, reshape how the world buys and builds software?

Murthy would go on to be called the “father of the Indian IT sector,” not because he wrote the most code or shipped the flashiest product, but because he helped popularize a model—outsourcing at global scale—that transformed India’s economy. It created millions of jobs, exported Indian talent to the world, and turned “Bengaluru” into shorthand for a new kind of technological power.

The Infosys saga hits nearly every enduring theme in business: ideology colliding with reality, navigating bureaucracy, a business model that looks obvious only after it works, the hazards of founder succession, and the brutal requirement to keep reinventing yourself in an industry that never stops moving. Founded in 1981 by seven engineers and headquartered in Bengaluru, Infosys would become one of the Big Six Indian IT companies.

This is a story of unlikely capitalists building an unlikely empire in an unlikely place. It’s about the Global Delivery Model—distributed work across time zones, run with industrial discipline—before that idea had a name. It’s about becoming the first Indian company to list on NASDAQ, about employee stock options that created some of India’s first salaried millionaires, and about a very public corporate governance fight in 2017 that threatened to fracture the company’s identity.

By the fiscal year ending March 2025, Infosys reported $19.28 billion in revenue, with 4.2% growth in constant currency, and operating margins of 21.1% even as wages rose across India’s talent market. The company that began with seven founders and $250 now employs more than 300,000 people across 50-plus countries.

But to understand how Infosys became Infosys, we have to start with a story that has almost nothing to do with software—and everything to do with a train ride through communist Yugoslavia.

II. The Founding Story & Ideological Origins

The Accidental Capitalist

In 1974, Narayana Murthy still thought of himself as a “confused leftist/communist.” He’d recently finished a stint in Paris, where he helped design an operating system to handle air cargo at Charles de Gaulle Airport. Now he was heading back to India by train, cutting across Europe—until a stop in a small border town near the Yugoslav-Bulgarian border changed everything.

Murthy has said that he was arrested and expelled for no good reason. He’s never lingered on the details, and over the years he’s been deliberately vague about what exactly happened. But he’s been crystal clear about what it did to him. The experience jolted him out of ideology and into reality. It didn’t turn him into a zealot for unfettered markets. It turned him into what he later called a “compassionate capitalist”—someone who believed wealth creation could be a force for good, but only if it was paired with ethics, transparency, and respect for people.

That shift mattered because it became Infosys’s operating system.

Before Infosys, Murthy worked as a systems programmer at IIM Ahmedabad and led a startup in Paris. Somewhere in that stretch—between building software, watching how modern companies operated, and thinking about what India could be—he began to form a simple thesis: an Indian company could deliver world-class software services to global clients. Not as a low-grade back office, but as a serious engineering partner.

And just as importantly, it could do it the “right” way. Murthy didn’t merely want to build a successful firm. He wanted to prove that an Indian company could run with strong corporate governance and treat employees as stakeholders in the mission, not disposable inputs. Over time, Infosys would become as known for how it conducted itself as for what it built.

The Seven Founders

Infosys was founded by seven engineers: N. R. Narayana Murthy, Nandan Nilekani, Kris Gopalakrishnan, S. D. Shibulal, K. Dinesh, N. S. Raghavan, and Ashok Arora. They were colleagues from Patni Computer Systems, and in 1981 they struck out together with about $250 in total capital.

The company was incorporated as Infosys Consultants Private Limited in Pune on 2 July 1981. In 1983, it relocated to Bangalore—where its global headquarters campus still stands today. Ashok Arora left in 1989 and sold his shares to the other co-founders.

But the famous $250 origin story has a very human detail inside it: the initial ₹10,000 came from Murthy’s wife, Sudha Murty. At the time, it wasn’t some symbolic gesture. It was the seed money that made the paperwork real. An act of faith in an idea that had no obvious reason to work.

In the beginning, the “company” was essentially wherever they could fit. The front room of Murthy’s home became the first office, though the registered office was at N. S. Raghavan’s home. Raghavan was also the first employee. Murthy, notably, was employee number four—he took nearly a year to finish up his responsibilities at Patni before joining the company he’d helped found.

And then there’s the detail that tells you everything about the era they were operating in: Infosys didn’t have a computer until 1983. Not because they didn’t think they needed one, but because Murthy couldn’t afford to import the system he wanted. Imagine a software company that, for its first two years, didn’t own a computer. That’s not a quirky startup anecdote. That’s pre-liberalization India—capital-starved, infrastructure-poor, and wrapped in red tape.

The 1990 Near-Death Experience

The founding myth—seven engineers, ₹10,000, a dream—skips the part where the dream almost died.

Murthy later described a moment in 1990 when Infosys was floundering. There were offers to buy them out, and some of the founders wanted to take them. They sat for hours—four or five, by Murthy’s telling—talking through what to do. The mood was bleak. After nearly a decade, they were tired, and momentum was hard to find.

Complicating things, a joint venture with Kurt Salmon Associates had fallen apart in 1989. It wasn’t the only problem, but it added to the sense that maybe the experiment had run its course.

This was the point where Murthy made what might have been the most consequential move in the company’s history: he offered to buy out anyone who wanted to leave.

It’s a deceptively simple decision, but it changes the whole dynamic. It turns a wobbly partnership into a conviction test. If you don’t believe, take the exit. But if you stay, you’re all-in. Murthy wasn’t quitting, and he wasn’t going to let uncertainty drag the company into a compromise sale.

The group rallied. The founders who stayed chose the long road—slow growth, steady execution, and the belief that the world was about to open up.

And then, almost on cue, the environment changed. In the early 1990s, as India embraced economic liberalization, Infosys began to find its footing and then accelerate. That 1990 crossroads became the hinge point: a moment of despondency that, through sheer stubbornness and shared belief, turned into the foundation for everything that came next.

III. The License Raj & Pre-Liberalization Struggle (1981-1991)

Building in Bureaucratic India

If 1990 was the moment the founders chose to stay in the fight, the decade before that was the reason the fight felt so exhausting.

In 1981, starting a business in India didn’t just mean finding customers and writing code. It meant navigating a state built to control who could produce what, where, and how. The system had a name—License Raj—and it turned ordinary business decisions into endurance tests.

Want to import a computer? Paperwork, approvals, delays, and the constant risk that your file simply disappears into the system. Want to expand an office? More permissions. Want to bring in outside expertise? Another wall of “good luck.”

Infosys was trying to build a modern software company inside an economy that made modernity feel like a special request.

So the early years were defined by constraint: little capital, limited infrastructure, and a regulatory environment that punished speed. India’s pre-liberalization model prized self-sufficiency, but in practice it often produced the opposite of what entrepreneurs needed—inefficiency, scarcity, and suspicion of global ambition. The idea that a small Indian firm could sell world-class software services to American corporations sounded, to many people, like a fantasy.

Which meant survival came first. Throughout the 1980s, Infosys did whatever work it could find. It wasn’t glamorous, and it didn’t look like destiny. But it built muscle: shipping under pressure, staying disciplined, keeping the team together, and learning how to operate in one of the toughest business environments on earth.

The Liberalization Inflection Point

Then, in 1991, India hit a breaking point. Foreign exchange reserves fell so low the country could barely pay for two weeks of imports. The crisis forced a reset. Under Finance Minister Manmohan Singh, the government began dismantling the License Raj and opening the economy—more competition, more foreign investment, fewer choke points.

For Infosys, it was a before-and-after moment.

Murthy later described the shift in plain terms: “We could travel abroad, we could travel easily, we could get consultants from outside, we could import—all of that.” The friction that had slowed everything started to lift. Infosys could access tools, talent, and—most importantly—markets that had previously been out of reach.

Growth had been steady but modest through the 1980s. In the early 1990s, as deregulation kicked in, India’s technology sector began to surge—and Infosys surged with it. Liberalization was like oxygen hitting a fire that had been smoldering for a decade.

And the global timing couldn’t have been better. U.S. companies were staring down a massive systems overhaul as the millennium approached—the Y2K problem. They needed programmers at scale. India had a growing pool of engineers, and companies like Infosys were positioned to deliver customized software quickly and cost-effectively to American clients.

What made Infosys stand out wasn’t just that the door opened. It was that they’d spent ten years getting ready for the moment it did. While others scrambled to assemble teams and credibility after liberalization, Infosys had already been building capability, discipline, and a point of view. When the constraints finally eased, they didn’t have to reinvent themselves.

They just had to accelerate.

IV. The Innovation That Changed Everything: Global Delivery Model

Inventing the GDM

Liberalization opened the door. Infosys still needed a way to walk through it—at scale.

If you had to name the single idea that best explains Infosys’s rise, it’s the Global Delivery Model. Not a product, not a patent: a way of organizing work across oceans that turned a talent advantage into an operating advantage.

Infosys is now a global software services company listed in the U.S. (on the NYSE) and in India (on the Bombay Stock Exchange). But the playbook that made that possible was first conceptualized, articulated, and implemented by Narayana Murthy: build in India, deliver to the world, and do it with process discipline strong enough to earn the trust of the biggest enterprises on the planet.

At the time, the prevailing model for Indian IT was basically a “body shop”: fly engineers to the client site in the United States, bill by the hour, rinse and repeat. Infosys flipped that. Instead of moving people to the work, they moved the work to India—keeping a smaller team onsite for client coordination and doing the bulk of development and execution offshore.

Yes, this captured the wage difference between Indian and American engineers. But the breakthrough wasn’t cheap labor. It was repeatability. The GDM made software delivery something you could industrialize: standardized processes, rigorous quality controls, and the ability to add capacity without losing your grip.

And then Murthy layered on a deceptively powerful idea: the “24-hour workday.” When teams in the U.S. logged off, teams in India were logging on. Work progressed around the clock through disciplined handoffs. For clients under pressure—especially during the Y2K rush—that was like adding a whole extra day to every calendar day.

Murthy also described the company’s cultural operating system as CLIFE: customer focus, leadership by example, integrity and transparency, fairness, and excellence. Call it values if you want. But in practice, it functioned like scaffolding—what kept the machine steady as Infosys grew from a small group of engineers into a global organization.

The IPO & Employee Stock Options Revolution

In February 1993, Infosys went public. The shares began trading in June 1993, opening at ₹145 versus an IPO price of ₹95.

But here’s the twist: the IPO was undersubscribed. Investors in India weren’t yet convinced that software services—still a fuzzy category at the time—deserved public-market faith. Morgan Stanley stepped in and took a 13% stake at the offer price, effectively rescuing the deal.

The public listing mattered. But what really changed the company’s trajectory was what Infosys did next. Around the time it listed, Infosys became one of the first Indian companies to introduce an employee stock-option plan.

This wasn’t treated as a perk. It was a statement of how Murthy believed the company should work: if you want people to act like owners, make them owners. It helped Infosys attract and retain talent in a fast-heating market—and, over time, it created some of India’s first salaried millionaires: engineers and managers who didn’t just earn wages, but participated directly in the upside they were building.

The NASDAQ Moment (1999)

In March 1999, Infosys listed its American depositary receipts on Nasdaq—becoming the first Indian company to list on an American stock exchange.

This was more than a financing event. It was a declaration that Infosys wanted to be measured against the world’s best, in the world’s most demanding market. Nasdaq wasn’t just a bigger pool of capital; it came with higher expectations around disclosure, governance, and credibility. Passing that bar signaled to global clients and investors that this wasn’t an outsourcing upstart—it was an institution in the making.

Infosys’s stock performance over the decades became legendary in India. The exact figures vary depending on the date you measure from, but the point is consistent: long-term shareholders saw extraordinary wealth creation simply by holding on.

And that’s the real story of this era. Infosys didn’t win because it discovered a secret market. It won because it systematized delivery—then proved to the world, quarter after quarter, that the system could be trusted.

V. The Growth Era & Founder Succession (2000-2014)

Scaling to Billions

The decade after the Nasdaq listing looked, from the outside, like a straight line up.

Y2K had been the introduction—an emergency that forced American corporations to take Indian software services seriously. But once the panic passed, something more durable happened: clients realized the work wasn’t just cheaper. It was good. Those one-off remediation projects turned into long-running relationships that expanded into application development, maintenance, and infrastructure management.

Then came a milestone that made Infosys impossible to ignore. In April 2004, Murthy announced that the Bengaluru-based company had crossed $1.06 billion in annual revenue, a 33% jump over the prior year—right in the middle of a global downturn in IT.

That context mattered. This was the post-dot-com hangover, when many U.S. tech companies were laying people off and cutting spending. Infosys, meanwhile, was compounding. The Global Delivery Model wasn’t just a growth engine—it was proving oddly resilient. When budgets tightened, the case for offshore delivery often got easier, not harder.

The Offshoring Controversy

Of course, a model that moved work across borders didn’t grow quietly.

In the mid-2000s, offshoring became a political flashpoint in the United States, with a heated debate over job losses and the outsourcing of work overseas. For Infosys, this wasn’t background noise. The company generated more than two-thirds of its revenue from American corporations, which meant U.S. politics could become a business variable.

Murthy’s response was pragmatic. He said it was “normal” for job-loss concerns to be raised, argued that outsourcing was “here to stay,” and then tried to take some heat out of the conversation by announcing that Infosys would establish a consulting unit in the U.S. that would employ 500 workers.

In the end, the controversy didn’t appear to materially dent the business. When Murthy retired in 2006, Infosys had roughly 70,000 employees and about $3 billion in annual revenue.

But the episode left a lasting imprint: political risk was real, and geographic concentration risk was real. If most of your revenue sits in one market, public sentiment and policy shifts in that market can matter as much as your delivery metrics. Infosys’s answer—building a larger onshore presence in key geographies—became a strategic priority that still shapes how the company operates.

Founder Succession Dance

One of the most underappreciated parts of the Infosys story is that, for a long time, it did succession unusually well.

Murthy served as CEO for 21 years, from 1981 to 2002, and then handed the role to co-founder Nandan Nilekani. Murthy stayed on as chairman from 2002 to 2011, and later became chairman emeritus.

In many founder-led companies, that handoff is where the trouble begins. At Infosys, it looked like a blueprint. Nilekani’s tenure as CEO—from 2002 to 2007—was a bright stretch: the company kept growing, its market capitalization surged, and when it was time to pass the reins again, Kris Gopalakrishnan took over without drama.

For a while, Infosys appeared to have solved a problem that trips up even iconic companies: how to transition leadership without losing the culture, the credibility, or the plot.

That impression wouldn’t last.

VI. The Vishal Sikka Era & The 2017 Crisis

Bringing in the First Outsider

By 2014, the founder-led era at Infosys was fading. The original team had either retired or was nearing retirement, and the market that had made Infosys great was shifting under its feet. Competitors like Accenture and Cognizant were pushing up the stack into consulting and digital work, while traditional IT services were starting to look more like a commodity.

So the board made a decision that would have been unthinkable for most of Infosys’s history: bring in an outsider.

Infosys appointed Vishal Sikka as its first non-founder CEO and managing director in more than three decades.

Sikka, born May 1, 1967, was an Indian-American executive best known for his time at SAP, where he served as CTO and led products and innovation. He arrived with deep technical credibility and an explicit mandate: don’t just run the services machine—reinvent it.

And he looked and acted the part of a different era. He spent more time in the United States, where Infosys earned most of its revenue. He carried himself differently than the suit-and-tie founder generation—often in a black t-shirt and blazer, a style that drew inevitable comparisons to Silicon Valley. Investors liked the narrative. From the time he took over on August 1, 2014, Infosys shares rose more than 20 percent.

His pay package also signaled how high the stakes were. His annual compensation was set at $13 million, plus stock options worth $9 million.

The Vision 2020 Strategy

Sikka quickly put a flag in the ground: “vision 2020,” a plan to reach $20 billion in revenue by 2020.

It was a daring target. Hitting it meant not just growing faster than Infosys had historically grown, but doing it in a more crowded, more skeptical market. Sikka’s bet was that the next phase of growth would come from reinventing what Infosys sold: more artificial intelligence, more design thinking, more platforms—less pure labor arbitrage.

Inside the company, the pitch landed with many employees. “Sikka was trying to change the way we do business,” an Infosys engineer said. “He was trying to make Infosys an innovation-driven company, not a commoditized service provider it has come to be known for.”

To push that mindset into a company built on process and predictability, Sikka launched “Zero Distance,” an initiative meant to embed innovation into every client engagement. Infosys also pursued acquisitions to build capabilities in newer areas. For a while, it looked like the reset might actually stick.

The Founder-Board Conflict

But while the strategy was being sold to the market, something else was happening in parallel: the trust between founders, board, and management was fraying in public.

Starting in early 2017, Infosys’s founders made repeated allegations about corporate governance and board decisions. The disputes weren’t abstract. They centered on executive compensation, the size of severance packages paid to departing executives, and concerns about certain acquisitions.

The founders still owned about 12.75 percent of the company—meaning they were minority shareholders. But ownership wasn’t the point. Murthy and the founding group carried enormous moral authority. They had built the institution, and they had spent decades positioning Infosys as a gold standard for governance. When they questioned the board publicly, it didn’t read like a normal shareholder disagreement. It read like a legitimacy crisis.

Compensation became the lightning rod. It was reported that Sikka drew an annual pay package during 2015–16 of Rs 49 crore, well above peers in Indian IT. Murthy framed the issue not as envy or optics, but as fairness. He wrote: “Giving nearly 60% to 70% increase in compensation for a top level person (even including performance-based variable pay) when the compensation for most of the employees in the company was increased by just 6% to 8% is, in my opinion, not proper. This is grossly unfair to the majority of the Infosys employees.”

Then the fight turned more personal. In a letter to his advisors, Murthy said Sikka was “not a CEO material but CTO material,” and claimed that at least three board members shared that view. Within hours of those comments becoming public, Sikka resigned.

The Resignation & Fallout

On August 18, 2017, Vishal Sikka stepped down, blaming what he called a “continuous drumbeat of distractions” and an ongoing row with founders over the company’s direction. In a blog post, he wrote: “I cannot carry out my job as CEO and continue to create value, while also constantly defending against unrelenting, baseless/malicious and increasingly personal attacks.”

The news hit like a thunderclap. Investors panicked. Infosys shares fell more than 13 percent to a three-year low of 884.20 rupees ($14.71), wiping about $4.85 billion off the company’s market value.

The board publicly backed Sikka—and just as publicly blamed Murthy’s pressure campaign for driving him out. Murthy responded that he was “extremely anguished by the allegations, tone, and tenor of the statements,” and said his concern was the deteriorating standard of corporate governance.

The spectacle was extraordinary: a board and a founder, both claiming to be defending the soul of Infosys, fighting it out in press releases.

“Murthy’s campaign against the board and the company has had the unfortunate effect to undermine the company’s efforts to transform itself,” the board said, adding that it had spent a year in dialogue with Murthy “without compromising its independence.”

For investors—and for anyone who had long viewed Infosys as a model citizen—the deeper shock was structural. This was the company celebrated for transparency and governance, and yet it had no clean way to resolve a conflict between influential founders and an independent board without detonating in public.

Infosys had built an operating system for global software delivery. In 2017, it discovered it still needed one for power.

VII. The Nilekani-Parekh Turnaround (2017-Present)

Nilekani's Return

Sikka’s exit didn’t just leave a CEO-shaped hole. It left a trust-shaped hole.

Infosys suddenly had to do two hard things at once: calm a spooked market, and find leadership that could stand in the middle of a very public tug-of-war between founders and board—without getting pulled apart.

The fix came from the one person who could plausibly talk to everyone. Nandan Nilekani, one of the original seven founders and a former CEO, agreed to return as chairman. In a sense, it closed the loop. The company’s three-year experiment with a fully professionalized, outsider-led era was over.

But calling it a retreat misses the point. Nilekani’s return wasn’t about going backward. It was about restoring enough stability to move forward again.

Salil Parekh Takes the Helm

On 2 January 2018, Salil Parekh joined Infosys as CEO and managing director, succeeding Vishal Sikka.

Parekh wasn’t a splashy choice—and that was exactly what Infosys needed. He came with nearly three decades in IT services and a reputation for operating discipline. Before Infosys, he spent 25 years at Capgemini, rising to the Group Executive Board and holding leadership roles across application services, cloud infrastructure, and engineering services through Sogeti. He also chaired Capgemini’s North America Executive Council and played a key role in building growth and turnaround momentum there, including expanding offshoring capabilities. Earlier in his career, he worked at Ernst & Young, where he was widely credited with helping scale its Indian operations.

His academic background matched the engineer-turned-operator profile: Master of Engineering degrees in Computer Science and Mechanical Engineering from Cornell, and a Bachelor of Technology in Aeronautical Engineering from IIT Bombay.

More importantly, Parekh represented a different kind of external hire than Sikka. Sikka was a product-and-vision executive, brought in to jolt Infosys into a new future. Parekh was a services veteran who understood the realities of running a massive IT delivery engine—and how to modernize it without setting it on fire.

His tenure quickly became defined by what you might call a quiet reset: fewer grand proclamations, more steady execution. The focus shifted toward winning large digital deals and continuing the move away from the old “body-shopping” reputation. Under Parekh, Infosys also leaned into ESG and aggressive upskilling, including training over 250,000 employees in AI and cloud technologies.

In time, Parekh was credited with stabilizing Infosys after the founder-management friction of the prior years. His term as CEO was extended through 2027.

The contrast with Sikka is the lesson. Where Sikka was charismatic and openly ambitious, Parekh was methodical and understated. Where Sikka set bold revenue targets, Parekh emphasized consistency, credibility, and calm. Under him, Infosys rallied around a strategy branded “Navigate Your Next”: help clients modernize through digital transformation, while protecting the operational excellence that made Infosys trusted in the first place.

VIII. The AI Era & Infosys Today

AI-First Strategy

After the 2017 governance crisis and the steadying hand of the Nilekani–Parekh era, the next question for Infosys was the same one facing every services giant: what happens when “digital transformation” stops being a differentiator and starts being table stakes?

Infosys’s answer has been to plant its flag in generative AI.

Infosys Topaz is the company’s AI-first set of services, solutions, and platforms built around generative AI. The promise is straightforward: help enterprises turn AI into real business outcomes—higher productivity, better decision-making, faster delivery—while holding the line on trust, privacy, security, and compliance.

The launch of Infosys Topaz in 2023 marked its biggest bet on the GenAI wave. The company positioned Topaz as “Responsible by design,” and backed the story with scale: a large library of AI assets, pre-trained models, and multiple AI platforms guided by AI specialists and data strategists. Topaz is built on Infosys’s applied AI framework, meant to help clients create an AI-first core and deliver cognitive solutions faster.

Salil Parekh put it in human terms: “Infosys Topaz is helping us amplify the potential of people – both our own and our clients'. We are seeing strong interest from our clients for efficiency and productivity-enhancing programs, even as businesses are keen to secure their future growth.”

In today’s portfolio, Topaz is the intelligence layer—and it pairs naturally with Infosys Cobalt, the cloud offering. If Cobalt helps clients move and modernize in the cloud, Topaz is designed to add AI on top of that foundation, including a growing set of active AI agents.

Infosys has also leaned on ecosystem partnerships to strengthen the pitch. Infosys and Intel expanded their strategic collaboration to help global enterprises accelerate AI adoption, with a focus on solutions that improve cost and performance while staying “responsible by design.”

Strategic Acquisitions

Alongside building new platforms, Infosys has kept buying capability—especially in areas that plug into its digital transformation roadmap.

After making two acquisitions in the year referenced, Infosys signaled it was still looking. Salil Parekh told PTI the company was interested in acquisitions across areas like data analytics and SaaS, and could also target select geographies in Europe and the U.S. He added that a deal at the scale of the recent in-tech acquisition was a real possibility.

That in-tech acquisition is a good example of what Infosys is trying to add: depth in Engineering R&D and a stronger foothold in Europe’s industrial base. Infosys announced a definitive agreement to acquire in-tech, an Engineering R&D services provider focused on the German automotive industry. in-tech works across e-mobility, connected and autonomous driving, electric vehicles, off-road vehicles, and railroads. The deal also brought Infosys a multidisciplinary team of about 2,200 people and relationships with marquee German original equipment manufacturers, with operations across Germany, Austria, China, the UK, and nearshore locations including the Czech Republic, Romania, Spain, and India.

Current Scale

By 31 March 2024, Infosys operated 94 sales and marketing offices and 139 development centers worldwide, spanning India, the United States, Canada, China, Australia, Japan, the Middle East, and Europe. In fiscal year 2023–24, revenue remained heavily weighted toward the West: about 61% from North America and 25% from Europe, with India at roughly 3% and the remaining 11% coming from other regions including the Middle East, Australia, and Japan.

The company described that year in terms of efficiency as much as growth: 4.2% constant-currency revenue growth, 8.3% earnings per share growth (after normalization of income tax refunds), 29.0% return on equity, and 44.8% free cash flow growth.

Financial year 2025 continued that execution pattern: 4.2% growth, operating margin of 21.1%, and free cash flow of $4.1 billion.

Zoom out, and the scale is almost absurd relative to the origin story. Among India’s IT giants, TCS is the largest employer, and Infosys sits right behind it, ahead of Wipro. Infosys today provides consulting, technology, outsourcing, and next-generation digital services to help clients execute digital transformation—and it remains the second-largest IT company in India, behind TCS.

IX. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces

1. Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MEDIUM

Breaking into IT services isn’t impossible. But breaking in at Infosys scale is. Over four decades, Infosys has built delivery infrastructure, hiring and training engines, and, most importantly, long-term client relationships that are painfully slow to replicate. It operates across 50-plus countries and works across industries like banking, healthcare, and manufacturing. It has also strengthened its reach through partnerships with major technology platforms, including Microsoft and Oracle.

The real “new entrant” risk isn’t a fresh services firm trying to recreate Infosys from scratch. It’s that cloud-native specialists can win narrow slices of work in specific verticals, and hyperscalers like AWS, Google, and Microsoft keep expanding into territory that used to belong exclusively to services companies. The threat isn’t a head-on collision so much as gradual erosion at the edges.

2. Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

This is the pressure that never goes away. Infosys sells primarily to large enterprises, and large enterprises buy from a position of strength. These customers have options, they negotiate hard, and they can use vendor competition as a lever on pricing and terms—especially when cost optimization becomes a board-level priority.

Infosys and its peers counter this with long-term engagements, deeper integration into client systems, and “strategic partnership” language that’s meant to raise switching costs. But the underlying reality stays the same: in a market with many credible suppliers, buyers usually set the rules.

3. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

In IT services, the key input isn’t steel or oil. It’s engineers.

India’s graduate pipeline and the sheer size of the labor market generally keep supplier power low. Even though competition for scarce skills is intense—especially in AI, cloud, and cybersecurity—the overall dynamics still favor large employers that can recruit, train, and deploy talent at scale.

Among the India-centric giants, TCS is the largest employer, with Infosys behind it, and Wipro next. The exact rankings matter less than the takeaway: this is an industry where talent supply is broad, and the biggest firms are built to absorb it.

4. Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM-HIGH

This is where the story turns from competition to disruption.

AI can be read two ways: as the next big revenue wave, and as the tool that makes parts of today’s work disappear. Tasks like coding, testing, documentation, and basic support—the bread-and-butter of large delivery organizations—are exactly the kinds of activities automation keeps targeting.

Infosys’s public posture has been confidence. “We don't see any layoffs in Infosys with these new-age technologies, and in fact, we continue to increase our recruiting as the economic environment changes,” Parekh said. But optimism doesn’t erase the core question. If customers can get more output with fewer humans, what happens to the economics of a people-heavy model?

The companies that win in the AI era will be the ones that turn substitution into repositioning: selling outcomes, running transformation programs, and owning higher-value layers of work—before the lower-value layers get compressed.

5. Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Rivalry in IT services is relentless because differentiation is hard. Most large providers can credibly offer IT consulting, outsourcing, and digital transformation across global markets. The fight often comes down to relationships, pricing, delivery reliability, and who can de-risk big programs for risk-averse enterprise buyers.

Infosys competes directly with Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), Accenture, Cognizant, HCL Technologies, Tech Mahindra, and Wipro. TCS is the market leader, and it has long been the reference point for scale and consistency.

One metric that often gets cited is productivity: in 4Q24, Infosys had the highest revenue per employee among the India-centric vendors, ahead of Cognizant, TCS, and Wipro ITS. That’s a useful signal, but it doesn’t change the nature of the battlefield. This is a crowded arena with capable opponents, and wins are usually earned one deal at a time.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Infosys benefits from meaningful scale, especially in delivery centers, training, and the ability to spread platform and operational investments across a huge revenue base. But this advantage is shared with other giants, which keeps it from being decisive on its own.

Network Effects: There aren’t strong classic network effects. Still, there are softer, indirect effects: an alumni network across global tech, a large installed base of clients, and reputational momentum that can lead to referrals and repeat business.

Counter-Positioning: The Global Delivery Model was counter-positioning at its best. Traditional incumbents like IBM and Accenture had cost structures and operating models that made it hard to match Infosys on price while maintaining margins. Over time, that edge faded as competitors adopted similar models and India-based delivery became industry standard.

Switching Costs: Moderate. Outsourcing relationships embed vendors deep into systems, processes, and institutional knowledge, and contracts can be multi-year. But switching is absolutely possible—and happens regularly, especially at renewal points or after major delivery failures.

Branding: Infosys carries strong brand equity in its core markets. In a services business where trust matters as much as technical skill, being known for reliability and governance has real value—especially after living through a public governance crisis and still remaining an institutional-grade supplier.

Cornered Resource: The Indian talent pool is broadly available, so labor isn’t a cornered resource. Where Infosys does have something more defensible is in accumulated intellectual property and platforms—Finacle, Topaz, and Cobalt—which represent years of product and capability building that competitors can’t instantly copy.

Process Power: This is the most enduring advantage. Infosys’s discipline in delivery—refined through the Global Delivery Model, quality processes, and massive training infrastructure—creates a kind of organizational muscle memory. It’s not glamorous, but it’s hard to replicate, and it’s exactly what big enterprises buy when they hand over mission-critical work.

X. Bull Case, Bear Case & Key Metrics

The Bull Case

The bull case for Infosys is basically a bet that the company’s core strength—running complex, global change programs for big enterprises—still matters, even as the technology underneath those programs keeps shifting.

AI could be the accelerant, not the arsonist. Infosys’s flagship here is Infosys Topaz, its AI-first suite built to weave generative AI into real business workflows. Cobalt modernizes the cloud foundation; Topaz is meant to add the intelligence layer on top. Infosys has said Topaz includes over 12,000 AI assets and 300 active AI agents. And in late 2025, it deepened ties with Microsoft by integrating Copilot across its 300,000+ workforce.

If GenAI makes transformations more urgent and more complicated—new architectures, new compliance demands, new operating models—then the companies that already sit inside the world’s largest IT environments may see more demand, not less.

Digital transformation also isn’t “done.” Many enterprises are still early in cloud migration and broader modernization. That keeps the runway open for a scaled player that can sell, deliver, and support multi-year programs across geographies and time zones.

Then there’s the balance sheet. Infosys is almost debt-free, has maintained a strong return on equity track record (with a three-year ROE of 30.7%), and has kept a healthy dividend payout (65.9%). In November 2025, it launched a ₹18,000 crore (about $2.15B) buyback—another signal of the “fortress balance sheet” posture—supported by free cash flow that had reached record highs of over $4 billion.

Finally, leadership and governance are no longer the headline risk they were in 2017. Salil Parekh has been widely credited with stabilizing the company after the turbulence and keeping it credible with both clients and investors—steady enough to execute, and experienced enough to navigate the next transition.

The Bear Case

The bear case is that the same forces that create opportunity for Infosys could also compress its core economics.

AI disruption is real. If AI meaningfully automates coding, testing, and maintenance—work that has historically fed large delivery organizations—then even a well-managed transition could be bumpy. Infosys can adapt, but the question is whether the industry’s revenue model adapts as fast as the tooling does.

Pricing pressure is another constant drag. Even with a modest uptick in discretionary spending among financial services clients in 4Q24, smaller deal wins—especially in consulting—were still infrequent. Vendors have been reprioritizing resources to match demand, and India-centric firms are leaning into competitive pricing enabled by offshore delivery as clients push hard for cost optimization. That environment can make growth harder and margins more contested.

Geographic concentration adds macro risk. In fiscal year 2023–24, roughly 61% of Infosys revenue came from North America. That exposure cuts both ways: it’s where the biggest budgets are, but it also ties Infosys tightly to U.S. economic cycles and policy shifts.

And then there’s simple competitive intensity. The sector remains crowded—Infosys, TCS, HCL, Tech Mahindra, Wipro, and global rivals—all fighting in a market facing volatility, rapid technology shifts, and customers determined to squeeze more value out of every dollar. That combination can threaten profitability and force strategy changes faster than large organizations like to move.

Key Metrics to Watch

For investors tracking Infosys, three metrics tend to tell the story early:

1. Large Deal Total Contract Value (TCV): This is the clearest signal of whether Infosys is winning the kind of multi-year engagements that create revenue visibility. Infosys has reported its highest-ever large-deal TCV at $17.7 billion, with 52% coming from new contracts.

2. Digital Revenue as Percentage of Total Revenue: Digital services made up about 57% of revenue. This bucket includes work that improves customer experience, uses AI-based analytics and big data, builds digital products and IoT, modernizes legacy systems, migrates applications to the cloud, and implements advanced cybersecurity. The direction matters more than the exact number: the higher this mix goes, the more Infosys is proving it can grow beyond legacy IT.

3. Attrition Rate: In a services company, talent is the engine. Attrition is an early warning system—about employee satisfaction, hiring pressure, delivery risk, and cost. Lower attrition usually means more stable delivery and less margin leakage from constant backfilling.

Conclusion: The Infosys Story as Investment Lens

The Infosys story is a useful lens because it compresses four decades of business reality into one arc: business model innovation, the upside and complexity of going global, and the very human problem of what happens when founders eventually have to let go.

This is a company that went from ₹10,000 in seed money to tens of billions in market value; from seven engineers in a Pune apartment to an organization with hundreds of thousands of employees spread across dozens of countries. However you slice it, that’s generational wealth creation.

And over the long term, Infosys has been exactly that: a great wealth creator. The day-to-day noise rarely changes the long-run narrative.

But the story also comes with a warning label. Even companies celebrated for governance and professionalism can face moments that feel existential. The 2017 crisis showed how founder dynamics can destabilize an institution decades after it’s been built. And now the AI revolution raises a harder question: not “who wins the next deal,” but “what happens to the unit economics of a people-heavy model if software work itself gets radically more automated?”

That’s what makes Infosys so interesting as an investment case: the tension between proven resilience and a genuinely uncertain technological future. The company lived through the License Raj, the dot-com bust, the 2008 financial crisis, and its own internal governance blow-up—and each time it found a way to adapt and keep compounding. Whether it can execute another reinvention in the AI era is the next test.

For long-term investors, buying Infosys is ultimately a bet on three things: India’s durable role in global technology services, Infosys’s ability to keep evolving its model without losing its delivery discipline, and the value of institutional capabilities built over decades. The stock has historically rewarded patience—early holders were rewarded beyond imagination—but it has also demanded conviction through inevitable periods of uncertainty.

The seven founders who pooled $250 in 1981 couldn’t have predicted the scale of what they were starting. But they seemed to understand something that doesn’t age: lasting value comes from conviction when it’s unfashionable, discipline when things are going well, and humility when the world shifts. Those principles—not any single technology cycle—are what built Infosys. They’re also what will decide whether the next four decades can be anything like the first.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music