Himadri Specialty Chemical: The Alchemy of Carbon

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a sweltering monsoon afternoon in Kolkata, the financial capital of eastern India. Out in the industrial belt of Hooghly district, a thick black liquid—closer to hot molasses than oil—is being heated to over 200°C and pumped into specially designed tanker trucks. This isn’t gasoline. It isn’t crude. It isn’t even “asphalt,” at least not in the way most people mean it.

It’s coal tar pitch: the sticky residue left behind when steel mills bake coal into coke. For most industries, it’s a messy byproduct—something to manage, store, and get rid of.

For one Kolkata-based family, it was a starting point.

Because if you look at coal tar pitch and you don’t see waste, you see carbon. And if you understand carbon—really understand it—you can turn that black gunk into materials that hold together aluminum smelters… reinforce the tires of millions of vehicles… and, increasingly, sit inside the battery packs that power electric cars.

That’s the story of Himadri Speciality Chemical Ltd.

On paper, HSCL is easy to describe in the language of annual reports: a specialty chemical company focused on R&D, innovation, and sustainability. But that gloss misses what makes Himadri interesting. This is a company that has spent decades getting unusually good at one thing: upgrading carbon. Step by step, product by product, they’ve moved from basic coal tar distillation to far more advanced carbon materials—right up to synthetic graphite and lithium-ion battery anode material.

And that’s where the plot widens from “regional industrial company” to “geopolitical supply chain story.”

Because the world’s battery supply chain has a center of gravity, and it’s China. In 2022, China produced the vast majority of the world’s key battery components—anodes, electrolytes, separators, cathodes. In 2023, it also accounted for a huge share of global battery pack and component exports. That concentration isn’t just an economic fact; it’s a strategic risk for the West, and a glaring dependency for India’s own EV ambitions.

So the question becomes almost absurdly compelling: can a family-run company from Kolkata—one that began by collecting and processing steel-plant byproduct—actually become a credible, scaled alternative in battery materials?

That’s what this story sets out to answer.

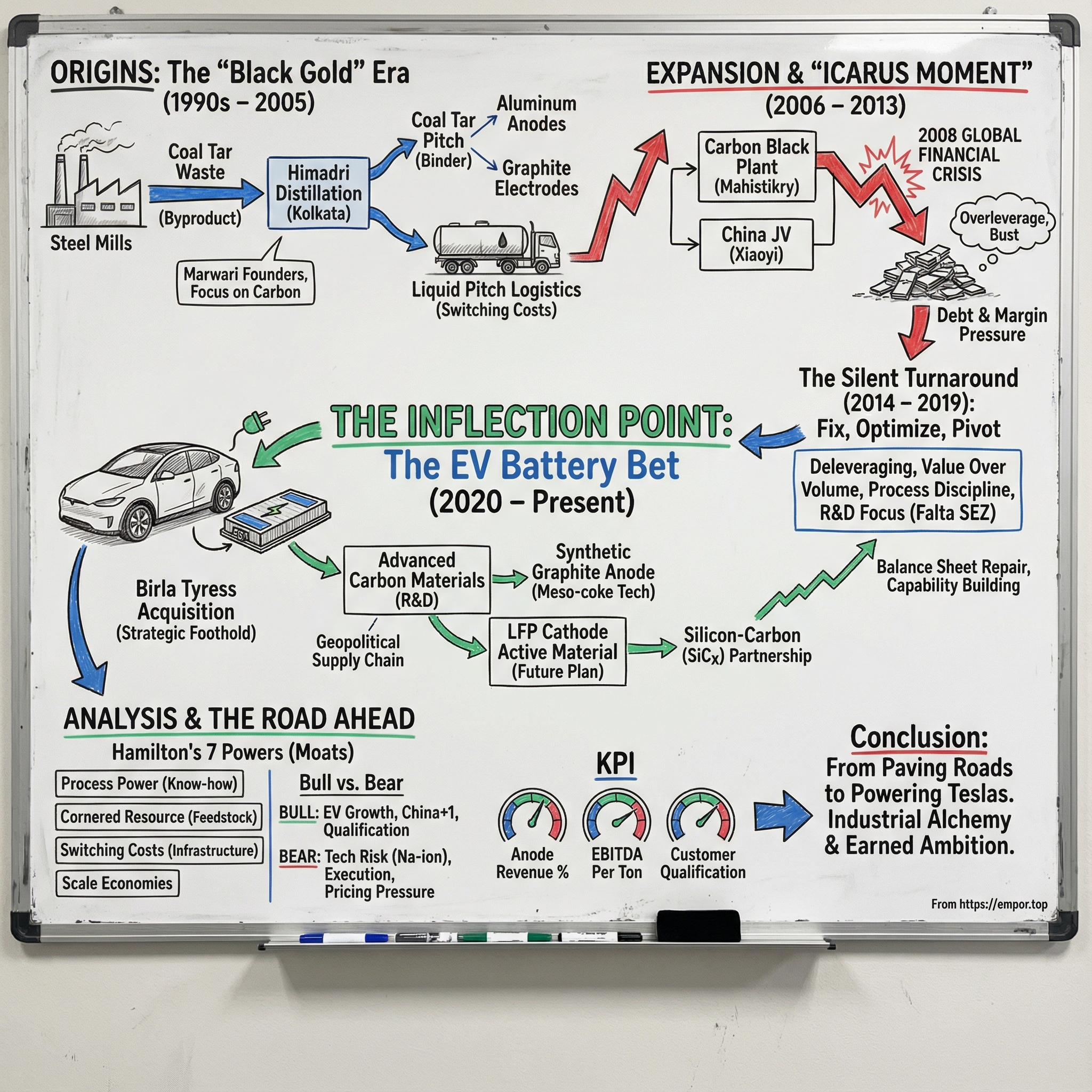

We’ll trace Himadri’s full arc: its beginnings in the early 1990s as a coal tar distillation business; the expansion years that nearly broke it during India’s crisis period; the quiet, disciplined turnaround; and then the big swing—building toward what it claims is end-to-end vertical integration from coal tar to finished anode material.

Along the way, we’ll pull apart the logic behind each pivot, the moats they’ve built (some intentional, some accidental), and the real question investors care about: does the bull case hold up once you strip away the buzzwords?

Because underneath the chemistry and the capex is a set of universal investing themes: turning someone else’s waste into your wealth; the strange, powerful versatility of carbon; and the classic fallen-angel comeback—a company that nearly wiped out, cleaned up the balance sheet, and then tried to reinvent itself into something much bigger than its origins.

II. Origins: The "Black Gold" Era (1990s – 2005)

Himadri’s corporate origin story starts with paperwork: incorporated on 28.07.1987 as Himadri Castings Pvt Ltd. But the real story begins a few years later, when the Choudhary family—Marwari businessmen with roots in trading and light manufacturing—noticed something hiding in plain sight inside India’s growing steel industry.

The founders were four brothers: Bankey Lal Choudhary, Vijay Kumar Choudhary, Shyam Sundar Choudhary, and Damodar Prasad Choudhary. Together, they had the mix you want at the beginning of any industrial journey: relationships to source material, discipline around capital, and a willingness to go where other people wouldn’t—into the messy, high-temperature, chemically finicky world of coal tar.

In 1990, the promoters set up a coal tar distillation unit at Liluah–Howrah in West Bengal. Commercial production began in December 1990, with an initial capacity of 4,800 MTs. To understand why that mattered, you have to zoom out to the steel value chain. When metallurgical coal is heated in coke ovens to make coke for blast furnaces, it doesn’t just produce coke. It also releases coal tar—a thick, sticky byproduct that amounts to roughly 3–4% of the coke produced. Small percentage, huge absolute volumes when a country is scaling steel.

Himadri’s business was built around a simple but powerful idea: don’t treat coal tar like a disposal problem. Distill it. Split it into intermediate chemical products. And then refine what’s left.

That “what’s left” is coal tar pitch—the residue after distillation. And pitch isn’t one uniform material; it’s something you engineer. Through distillation and further processing, you tune chemical and physical properties to meet exact downstream requirements.

The Choudhary brothers’ key insight was that steel mills wanted coal tar off their hands, while other industries desperately needed what was inside it. Over time, Himadri became the largest coal tar pitch manufacturer in India, with more than 70% market share. Its pitch became a trusted binder for two critical applications: aluminum anodes and graphite electrodes.

Aluminum is where the demand story really clicked. Producing aluminum through electrolysis requires carbon anodes to conduct electricity into molten alumina. And those anodes don’t hold together on their own—you need a carbon-rich binder. Coal tar pitch is that binder. So as India’s aluminum industry expanded through the 1990s—with players like Hindalco, Vedanta, and NALCO adding capacity—pitch demand rose right alongside it.

Himadri supplied coal tar pitch to major domestic customers including Nalco, Hindalco, Balco, and Graphite India, and also to international names like Dubal, AOG, and SGL.

Then came the move that looks obvious in hindsight, but was operationally gutsy at the time: they changed how pitch was delivered.

Traditionally, coal tar pitch was shipped as solid blocks. You’d cool it, solidify it, transport it, and then the customer would have to melt it again before use. That meant extra cost, extra handling, and inconsistent quality.

Himadri invested in a fleet of specially designed insulated tanker trucks capable of transporting liquid pitch at temperatures above 200°C—delivering it directly into customer facilities.

That sounds like a logistics detail. It wasn’t. It created real switching costs. Customers had to build receiving infrastructure—heated tanks, pipelines, unloading systems—designed around liquid pitch deliveries. Once a smelter made that investment and tuned operations to Himadri’s supply, switching suppliers wasn’t just signing a new contract. It meant disruption and capex. These relationships didn’t just live in purchase orders; they were bolted into plant layouts.

As the operating business took shape, the company structure evolved quickly. The name changed to Himadri Chemicals & Industries Pvt Ltd on 20.11.1991, and it was converted into a public limited company on 27.11.1991. In 1992–93, the company made a public issue of Rs 30,000,000.

By the mid-1990s, a pattern was already emerging—the playbook Himadri would run for decades: start with an unwanted waste stream, develop processing know-how, make the product dependable, lock in customers through infrastructure and quality, and expand capacity as demand grows.

In 1996, Himadri developed a method to produce impregnating pitch—an early step toward more advanced, higher-value carbon materials. Impregnating pitch is used to densify carbon products for specialized applications, and it represented a clear move up the value chain from standard binder pitch.

Expansion followed. The company commissioned another coal tar distillation plant in Howrah and set up a manufacturing unit in Visakhapatnam. Visakhapatnam wasn’t random—it brought Himadri closer to industrial customers in the region and to port infrastructure, opening the door to smoother logistics and exports.

This is also when the next generation began to take shape inside the business. Anurag Choudhary joined Himadri in 1992 and later became CEO in 2006. He joined young—at eighteen—and spent years learning the technical details of carbon chemistry alongside the commercial realities of selling into heavy industry. He wasn’t being groomed in a conference room. He was learning specifications, process behavior, and customer pain points the hard way.

By 2005, Himadri had cemented itself as the dominant player in India’s coal tar pitch market, supplying the aluminum and graphite electrode industries at scale. The moat around the core business wasn’t one thing—it was a stack: supply relationships for raw material, distillation expertise, the liquid pitch logistics system, and deeply embedded customer operations.

But dominance in pitch wasn’t the destination. The founders were already looking downstream, toward bigger markets and more value-added products that could ride on the same carbon backbone. The open question was whether they could scale that ambition without stretching the balance sheet too far.

As you’ll see next, they came very close to answering that question the wrong way.

III. Expansion & The "Icarus Moment" (2006 – 2013)

The mid-2000s were rocket fuel for Indian industrial companies. GDP growth was strong, steel output was rising, infrastructure capex was everywhere, and capital was plentiful. Himadri, coming off years of success in coal tar pitch, decided it was time to go bigger—and to go downstream.

The big bet was carbon black.

In 2007–08, Himadri commissioned a melting plant at Korba—dedicated facilities built close to major customers so it could supply pitch faster and tighter, more like a just-in-time industrial partner than a commodity vendor.

At the same time, it kicked off a much more ambitious project at Mahistikry in West Bengal: a carbon black plant with about 50,000 MT of annual capacity, plus a 12 MW captive power plant that used waste-heat gas. This was forward integration in its purest form—build the next link in the chain, then bring your own power along for the ride.

Carbon black is the fine black powder inside tire rubber. It’s what makes tires black, but more importantly, it’s what makes them tough—improving strength, durability, and wear resistance. And it doesn’t stop at tires. Carbon black also shows up in inks and coatings, plastics, conductive cables, packaging, and other applications where color and conductivity matter.

The logic for Himadri was clean: they already had the feedstock. Coal tar distillation doesn’t just produce pitch; it also produces oils. Those oils could become raw material for carbon black. One process feeding the next. Less waste, more value captured.

The market backdrop helped too. India’s auto and tire sectors were expanding, and domestic carbon black supply was struggling to keep pace. Himadri saw an opening to become a meaningful player.

Capital showed up to fund the story. Bain Capital agreed to invest up to $124 million in Himadri, including $54 million for new shares that gave Bain a 15% stake. For a mid-cap industrial company out of Kolkata, that was a loud signal. A global private equity firm had underwritten the expansion plan—and the market treated Himadri accordingly. The stock became part of the era’s favorite trade: the “India infrastructure growth” proxy.

Himadri even reached beyond India. In September 2008, through its wholly owned subsidiary Himadri Global Investment Ltd, the company entered into a joint venture contract with a Chinese partner to take over an existing coal tar distillation plant in Xiaoyi, Shanxi. It was an attempt to plant a flag inside the world’s biggest carbon-materials ecosystem.

And then the world snapped.

The global financial crisis hit in 2008. Even though it started in American housing, it quickly became a global liquidity event. Capital fled risk markets, currencies moved violently, and India saw sharp depreciation as foreign investors pulled money out. The rupee weakened, and suddenly everything connected to imports or foreign-currency borrowing got more expensive at the exact wrong time.

Himadri had financed its expansion aggressively. With currency moves and tighter credit, that debt got heavier. Costs rose. Margins compressed. And the balance sheet—built for a boom—was forced to absorb a bust.

For a company expanding into carbon black, where input costs can be volatile and pricing power can be limited, the squeeze was brutal. What had looked like a confident move toward integration began to look, to the market, like classic overreach.

The stock, which had ridden the optimism of the boom, collapsed. Himadri went from “mid-cap darling” to something far less flattering: a commodity player with too much leverage.

Credit markets noticed too. ICRA cited a consistent decline in operating margins and weakening debt-protection metrics as key reasons behind rating pressure. Once ratings slide, refinancing doesn’t just get harder—it gets more expensive, and the spiral tightens.

This was Himadri’s near-death experience: not a failure of technology or customers, but a failure of timing and balance-sheet resilience. The company spent years in the penalty box, ignored by most institutions who assumed it would remain stuck—exposed to volatile inputs, boxed in by commodity dynamics, and weighed down by debt.

For the Choudhary family, this period became a crucible. Plenty of promoter-run companies respond to this kind of stress by chasing volume, sacrificing profitability just to stay visible. Others sell out. Himadri chose a slower, harder option: repair first, and only then rebuild.

It’s the part of the story investors often skip, because it’s not glamorous. But it’s the setup for everything that comes next: a long, disciplined turnaround—and a pivot from “more capacity” to “better economics,” from commodity momentum to engineered carbon.

IV. The Silent Turnaround: Fix, Optimize, Pivot (2014 – 2019)

From 2014 to 2019, Himadri did something rare in Indian industry: it turned itself around without an external savior, without a flashy new narrative, and largely without the market noticing.

After the 2013 hangover, the stock stayed depressed and coverage thinned out. But inside the business, management was doing the unglamorous work—tightening operations, repairing the balance sheet, and quietly building the capabilities that would later make the EV pivot even possible.

Anurag Choudhary had joined Himadri in 1992 and became CEO in 2006. This was the period where his leadership style really showed. The company stopped acting like a volume-chasing commodity producer and started behaving like an operator obsessed with unit economics.

The internal mantra became “value over volume.” Instead of maximizing tonnage, the focus shifted to profitability per ton and returns on capital. That meant walking away from business that looked good in revenue terms but didn’t pay in margin. It meant process improvements, cost discipline, and a much stricter filter for where every rupee of capital went.

That discipline wasn’t just philosophical—it was enforced by reality. The most important project of these years wasn’t a new plant. It was deleveraging.

The company chose to prioritize debt reduction over dividends, expansion, and even some near-term investments. Cash that could have funded growth instead went to the banks. It was slow, painful, and exactly what the prior decade had made non-negotiable.

They also used structural fixes where they could. In March 2016, Deferred Deep Discount Debentures were converted into 32,675,297 equity shares at Rs 19 per share, after shareholder approval at an Extra-Ordinary General Meeting. It was a pragmatic move: reduce repayment pressure, simplify the balance sheet, and buy breathing room.

By the end of this stretch, the headline outcome mattered: Himadri was virtually net debt-free. For a company the market had written off as overleveraged, that was the foundation stone for everything that followed.

But here’s what made the turnaround more than just financial rehab: while the company was paying down debt and tightening operations, it was also laying track for the next decade.

Himadri’s R&D unit at Mahistikry was recognized by the Department of Science and Technology and Industrial Research, Government of India, and the centre was accredited by the National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration Laboratories (NABL). During years when resources were constrained, the company still built a serious R&D engine and staffed it with experienced talent, including international experts.

This wasn’t R&D for press releases. It was the beginning of Himadri’s shift from “products that happen to be made from carbon” to “carbon as a platform.”

As Anurag Choudhary put it: “The most interesting thing about coal tar is it’s a powerhouse of 250 organic chemicals. It’s an unending carbon chemistry, which one can explore to the best of ability to generate innumerable compounds.”

That’s not poetry—it’s strategy. Coal tar isn’t one substance; it’s a dense cocktail of organics at different boiling points. If you know how to separate and purify them, you can build an entire portfolio: naphthalene, specialty oils, quinoline, fluorene—and, crucially, the kind of precursors that start to matter when the world begins caring about synthetic graphite and advanced carbon anodes.

In fact, one of the early signals of where Himadri wanted to go had already appeared years earlier: the company commenced production at its Advanced Carbon Material plant in Falta SEZ, West Bengal. That milestone didn’t change the market’s opinion at the time, but it mattered internally. It was the first real step toward the category that would later define the next act: lithium-ion battery materials.

So the “silent turnaround” wasn’t just about survival. It was capability-building—developing proprietary processes and know-how for higher-grade carbon materials before EV supply chains became dinner-table conversation.

Even the company’s identity was updated to match the direction of travel. Himadri Speciality Chemical Limited was formerly known as Himadri Chemicals & Industries Limited, and it changed its name to Himadri Speciality Chemical Limited in July 2016. It was a signal, both internally and externally: this wasn’t supposed to be a commodity story anymore.

By 2019, Himadri had done what few believed it could do after the crash: restore profitability, clean up the balance sheet, and create a pipeline of R&D-led growth options—setting the stage for the electric-vehicle era. Under Anurag’s execution-driven approach, the company delivered a 30% CAGR over six years.

The investor lesson is uncomfortable, but useful: real turnarounds are slow. Himadri spent years in the wilderness doing work that didn’t show up in the stock chart right away. But when the market finally started pricing the EV supply chain opportunity, Himadri wasn’t scrambling to invent a strategy—it had already done the hard part.

V. The Inflection Point: The EV Battery Bet (2020 – Present)

The pandemic in 2020 broke a lot of supply chains. It also made one trend impossible to ignore: electrification was no longer a niche. Governments started putting real timelines on the phaseout of internal combustion engines. Tesla’s rise reset expectations for what “automotive” even meant. And suddenly, the world began asking a new kind of energy-security question.

Not “who controls the oil?” but “who controls the battery?”

Himadri’s management had been quietly preparing for this moment. Because if EVs were going to scale, battery materials would have to scale with them—and the supply chain, especially for key components, was overwhelmingly concentrated in China.

By 2022, China was producing roughly 90% of anodes and lithium electrolyte solutions. Versions of that number showed up across research reports and presentations, and it landed the same way in boardrooms and government offices: this wasn’t just a commercial issue. It was a strategic vulnerability.

And the deepest choke point in that system is graphite.

Benchmark has pointed out that China isn’t just a major player in graphite—it dominates it end to end. China mines a large share of natural flake graphite and, more importantly, controls conversion into spherical graphite, the processed form required for most battery anodes.

To see why that matters, you need a quick lithium-ion battery refresher.

Most EV battery conversations obsess over the cathode. That’s where the headline metals live—lithium, cobalt, nickel—and where the dramatic supply-chain stories come from. But the anode, the negatively charged electrode, is just as non-negotiable. In most lithium-ion batteries globally, the anode is graphite. Graphite’s structural stability and electrochemical behavior make it ideal for reversible lithium-ion storage. It’s what allows current to flow, and it’s what hosts lithium ions as they shuttle back and forth during charge and discharge.

In other words: you can’t build a lithium-ion battery without graphite.

Even better, cheaper cathode chemistry doesn’t solve that. The anode remains stubbornly carbon-heavy. Natural graphite can offer slightly higher capacity and lower cost, but much of today’s battery anode market is synthetic anode active material. The reason is consistency: synthetic graphite tends to be more uniform and reliable at scale, which matters when you’re qualifying materials for high-performance cells.

This is where Himadri’s decades in carbon stop looking like legacy baggage and start looking like a launchpad.

Himadri has positioned itself to make best-in-class anode materials with a low carbon footprint, and it points to a key differentiator: it’s backward integrated into the precursor coke required for anode materials, through its in-house “Meso-coke” technology.

Vertical integration here isn’t a vague slogan. A synthetic graphite anode supply chain usually begins with a precursor like petroleum coke or needle coke. That precursor gets pushed through extreme high-temperature processing to create the crystalline graphite structure, and then it’s milled, shaped, and coated into the particle profile battery makers demand. Many anode producers buy their precursor from third parties. Himadri produces its own precursor from coal tar derivatives—an advantage that can translate into both supply security and better control over cost and quality.

Himadri describes its synthetic graphite as a strong anode material because of its conductivity, stability, cycle life, and well-defined crystalline structure—traits that come from how the precursor is processed and graphitized.

But the company’s ambitions don’t stop at the anode.

Himadri announced what it called India’s first commercial plant for Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) Cathode Active Material. The company said it plans to build up to 200,000 MTPA of LFP cathode active material capacity in phases over the next five to six years, aimed at supplying material for up to 100 GWh of lithium-ion batteries.

It’s a big swing. Phase I alone is slated at 40,000 MTPA, with an estimated cost of INR 1,125 crores. If executed, it would move Himadri from being “an anode story” to something broader: a materials platform that can potentially serve both sides of the cell.

At the same time, Himadri has been signing up for next-generation optionality. It announced an exclusive technology licensing partnership with Sicona, an Australian battery materials company, giving Himadri rights to access, localize, and commercialize Sicona’s Silicon-Carbon (SiCx) anode technology in India.

Silicon-carbon is widely viewed as the next frontier because silicon can store far more lithium than graphite—but it comes with engineering challenges. Sicona’s approach is positioned as an additive used alongside traditional graphite. Himadri has pointed to typical blend proportions of 5–20%, with potential improvements of about +20% energy density and +40% charging performance. The takeaway isn’t the exact percentages—it’s that Himadri is trying to secure a seat at the table for what comes after today’s graphite-dominant anode.

Then came the move that made even longtime followers do a double-take: Birla Tyres.

A consortium acquired Birla Tyres through a resolution plan approved by the National Company Law Tribunal in October 2023. Dalmia Bharat Refractories Limited (DBRL) was the acquirer along with Himadri as its strategic partner, with Himadri described as the predominant investor. The deal involved Birla Tyres’ debt of around Rs 1,000 crore and referenced a liquidation value of Rs 335 crore, while the acquisition value cited was Rs 347 crore.

On the surface, it’s an odd pairing: a specialty chemical and carbon materials company stepping into a distressed tire manufacturer.

But Himadri’s own framing is straightforward. It had already integrated forward from oils into carbon black, and then into specialty carbon black. Buying Birla Tyres moves it one step closer to the end customer—tyres—where carbon black is a critical input. In that light, Birla becomes both a potential captive customer for Himadri’s carbon black and a strategic foothold in the EV ecosystem, where tire requirements evolve thanks to heavier vehicles and instant torque.

Himadri later completed the acquisition of Birla Tyres, making it a wholly owned subsidiary, through a combination of converting debentures into equity shares and purchasing the remaining shares.

Finally, even the old core business—coal tar pitch—has been gaining new legs geographically. Himadri announced the execution of its first-ever liquid coal tar pitch export shipment to the Middle East from its terminal at the New Mangalore Port, which it described as a December 2025 milestone. The company positioned this as opening a new export corridor alongside its existing Haldia Port terminal on India’s eastern coast.

Put all of this together and the shape of the bet becomes clear: Himadri is trying to turn decades of “dirty” carbon processing into something the modern world suddenly can’t live without—a non-China pathway for critical battery materials, built on process know-how, integration, and speed.

VI. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Now comes the real question: is Himadri building something durable, or just catching a cycle at the right time?

A useful way to answer that is Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework—one of the cleanest lenses for separating “good business” from “good luck.”

Process Power: The Strongest Moat

Process power is what you get when a company discovers a superior way to make something—and that advantage can’t be bought off the shelf or copied quickly.

Himadri’s story is basically a slow compounding of process know-how. Over roughly three and a half decades, it kept getting better at coal tar distillation, then at carbon black, and now at the more demanding world of battery-linked carbon materials. That’s what enables the company’s broader claim: it has helped build one of the world’s most extensive value chains in the carbon segment, moving from “sell pitch” to “engineer carbon.”

And this isn’t just internal confidence. Himadri has developed and supplied a super-specialty grade of coal tar pitch to DRDO. When India’s defense research ecosystem is willing to use your material, you’re no longer competing purely on price and volume—you’re competing on consistency, precision, and repeatability.

This is where carbon turns into “black art.” The final properties depend on variables that interact in messy, non-linear ways: temperature curves, pressure, residence time, and feedstock composition. You don’t master that from a textbook. You master it through accumulated operating experience, specialized equipment, and years of trial-and-error where the failures teach you what not to do. That’s classic process power—and it’s one of the hardest advantages for a competitor to replicate on a timetable.

Cornered Resource: Feedstock Security

The second power is less glamorous but just as real: access.

Coal tar isn’t something you can conjure up with a purchase order. It’s produced in limited quantities as a byproduct of steelmaking, and steel mills generally prefer long-term, reliable offtake partners who can take consistent volumes without drama. Himadri, as the largest producer of coal tar pitch in India with around 70% market share serving the Indian graphite and aluminium industries, sits in a privileged position in that ecosystem.

So if you’re a new entrant trying to compete, your first problem isn’t building a plant—it’s getting the feedstock. Himadri has already built the relationships and operating track record that help secure supply, creating a cornered resource dynamic where the input itself becomes a barrier.

Switching Costs: Infrastructure Lock-in

In the legacy pitch business, switching costs are literally embedded in customer facilities. Himadri’s liquid pitch model requires receiving infrastructure—heated tanks, unloading systems, and process integration. Once a smelter has invested in that setup and tuned operations around it, changing suppliers is not a simple vendor swap. It’s operational disruption and additional capex.

In battery materials, the switching cost logic becomes even stronger. Battery qualification is slow and unforgiving—often taking two to three years. If Himadri’s anode material gets designed into a cell and passes qualification, the customer has every incentive to stick. Switching means re-qualification, risk of production disruptions, and potential downstream implications for warranties and performance guarantees.

Scale Economies: Spreading Fixed Costs

Scale is the power that makes everything else cheaper per unit.

Himadri is the largest coal tar distiller in India, and that lets it spread fixed costs—R&D, compliance, logistics, and plant overhead—across a bigger volume base than smaller competitors can. In a business where process control and regulation matter, that’s not a footnote; it’s a structural cost advantage.

The same logic applies as specialty carbon black expands. Himadri has indicated that once its planned expansion is completed, total specialty carbon black capacity will rise to 1,30,000 MTPA, positioning it as the world’s largest specialty carbon black facility at a single site. If that scale comes online as intended, it reinforces the same advantage: lower unit costs and more leverage to invest in product development and quality systems.

Counter-Positioning and Network Effects

These are less central here. Himadri doesn’t benefit from network effects in the classic platform sense. And while the “China alternative” narrative helps commercially, it’s more positioning than a self-reinforcing structural moat.

Brand Power

Himadri isn’t a consumer brand, but it has something industrial companies care about more: trust built through consistent quality and reliable supply over decades.

That brand credibility is also being reinforced through sustainability credentials. Himadri has received EcoVadis Platinum status—awarded to the top 1% of companies assessed globally out of more than 130,000—along with ISCC PLUS certification. For global customers who increasingly treat sustainability as a procurement requirement, not a marketing line, those signals can matter.

VII. The Playbook: Lessons for Builders

Himadri’s arc isn’t just a carbon story. It’s a blueprint for how unglamorous industrial companies can build enduring advantage—if they’re willing to play the long game.

"Don't Waste the Waste"

Himadri was built on a simple idea that most people overlook: the best raw materials are often the ones nobody wants.

Steel mills treated coal tar like a messy disposal problem. Himadri treated it like a feedstock—then kept upgrading it, step by step, into pitch, carbon black, specialty chemicals, and now battery-linked carbon materials. The broader lesson is portable: great businesses often start by turning an ugly byproduct into a reliable input, and then compounding capabilities around it.

The Pivot Requires Patience

Himadri didn’t get to make the EV battery bet by waking up one day and deciding to chase the hottest theme in the market.

It earned the right to pivot. Nearly a decade of balance-sheet repair, operational tightening, and steady R&D investment created the foundation. Without that financial stability and manufacturing credibility, “transformational opportunity” would’ve been just another slide in a presentation. The lesson is blunt: you can’t shortcut a turnaround, and you can’t fund a big pivot on a fragile balance sheet.

Family-Run Long Termism

Family-run Indian companies often get painted with one broad brush: promoter-driven, opaque, and short-term. Himadri offers a different model.

When the post-2013 crash hit, survival meant doing the boring work—deleveraging, improving unit economics, and rebuilding trust—while the market looked elsewhere. And earlier, the willingness to bring in an institutional investor like Bain Capital, even at the cost of dilution, signaled something important: pragmatism over ego.

Anurag Choudhary joined the company at eighteen and later became CEO. Over decades, he moved with the company—from commodity pitch to engineered carbon—without trying to force overnight reinvention. In a business that compounds through process know-how, that kind of continuity matters.

China+1 is Real, but Hard

“Not China” is not a strategy. It’s a starting condition.

To compete with Chinese battery-material producers, you have to match them where it hurts: cost, consistency, and scale. Himadri’s answer is vertical integration—controlling more of the chain from coal tar to precursor to finished anode material—so it isn’t just assembling imported inputs and hoping geography carries the day.

China+1 is real. But the companies that win it won’t be the ones with the loudest announcements. They’ll be the ones that can deliver quality at scale, year after year, with the economics to survive the down cycles.

VIII. Bear vs. Bull & The Road Ahead

The Bull Case

The bullish thesis for Himadri is basically a three-part bet: the EV wave keeps building, the world keeps de-risking away from China, and Himadri converts its carbon know-how into qualified, recurring volumes.

Start with the macro. EV adoption—especially in India—isn’t a one-year trend. It’s a long runway. The EV sector in India is expected to attract around USD 40 billion of investment, and a large share of that is projected to go into lithium-ion battery manufacturing. If that capital actually lands and domestic cell capacity ramps, localizing materials becomes less “nice to have” and more “you either have it or you don’t ship.”

Then there’s China+1. Western automakers and battery makers aren’t just shopping for the lowest-cost supplier anymore; they’re under pressure to diversify. In battery materials, the hard part isn’t building a brochure or a pilot line—it’s getting qualified. If Himadri can qualify as a supplier to global battery manufacturers, it’s not incremental growth. It’s a step-change in scale, because qualification can open the door to long-duration, repeat orders.

And finally, the company’s recent financial trajectory adds credibility to the story. In FY 2024–25, Himadri reported revenue of ₹4,612.63 crore, up from ₹4,184.89 crore in FY24. Net profit rose to ₹555.09 crore from ₹410.68 crore, a year-on-year increase of more than 35%.

Management has also highlighted the longer arc: over the past five years, the company reported revenue growth at a CAGR of 29% since FY 2021, with EBITDA and PAT compounding faster. Just as important, Anurag Choudhary, CMD & CEO, has pointed to an achievement that matters in cyclical, capex-heavy industries: becoming debt-free with a positive net cash balance. That gives Himadri flexibility to fund the next leg—without repeating the balance-sheet stress of the last cycle.

The Bear Case

The bear case isn’t about whether carbon is useful. It’s about whether the specific kind of carbon Himadri is betting on stays essential, and whether the company can execute at battery-grade quality while competing against the most scaled players on earth.

Technology Risk: Battery chemistry can change the rules. Sodium-ion batteries are a real example: they typically use hard carbon—disordered, non-graphitizable, largely amorphous carbon—rather than graphite for the anode. Graphite doesn’t work well in Na-ion systems because sodium ions are larger and don’t intercalate the same way between graphite layers. Today, hard carbon remains a relatively small market, and this isn’t an imminent threat—graphite anodes should dominate for years. But over a long enough horizon, shifts toward sodium-ion or other architectures (including solid-state variants with different anode needs) create a genuine obsolescence risk for graphite-focused investments.

Execution Risk: There’s a big gap between being excellent at specialty chemicals and being trusted as a battery-material supplier. Battery manufacturers run on unforgiving specifications and near-zero tolerance for contamination or inconsistency. The question isn’t whether Himadri can make good material in a lab; it’s whether it can repeatedly make the same material—at scale—batch after batch, month after month, and pass customer audits and qualification cycles.

Geopolitical and Pricing Risk: Even if the science works and qualification happens, pricing can still kill the economics. If Chinese producers decide to defend share with aggressive pricing, margins for new entrants can compress fast. Chinese anode producers benefit from scale, cheaper energy, and deeply integrated supply chains, and they’ve shown an ability to keep lowering costs. In synthetic graphite, two of the biggest cost drivers are feedstock (coke) and graphitisation costs—areas where Chinese incumbents have structural advantages and room to play offense.

Porter's Forces: Threat of Substitutes

In the near term, synthetic graphite is expected to keep a dominant position in lithium-ion anodes. But natural graphite remains the obvious substitute, and it keeps resurfacing because the trade-offs are real.

Natural graphite anodes can offer lower cost, high capacity, and lower energy consumption versus synthetic. Synthetic graphite, meanwhile, typically wins where premium cell makers care most: electrolyte compatibility, fast-charge performance, and longevity.

That tension—natural versus synthetic—will keep shaping the anode market. Himadri’s focus on synthetic graphite positions it toward the higher-performance, higher-consistency end. But if the industry’s center of gravity shifts toward cost, and natural graphite gains share, the market mix could move against synthetic over time.

IX. Key Performance Indicators

If you want to track whether Himadri’s EV bet is turning into a real business—or staying a promising narrative—three KPIs matter more than most.

1. Anode Material Revenue as Percentage of Total Revenue

This is the cleanest scoreboard for the transition. Himadri’s legacy engine is still pitch and carbon black. The re-rating, if it comes, will come from higher-value new energy materials. Over time, you want to see this share rise steadily—proof that batteries are becoming a meaningful contributor, not just a pilot program.

2. EBITDA Per Ton

In carbon, growth can be deceptive. You can ship more tons and still make less money if the mix worsens or input costs move against you. EBITDA per ton is the better truth serum: it reflects pricing power, process efficiency, and whether the company is actually upgrading its product mix as it scales.

3. Customer Qualification Milestones

For battery materials, revenue lags reality. Qualification is the gate. Getting approved by a major cell maker or OEM is a leading indicator that the material meets tight performance and consistency standards—and that volume can follow. Each qualification milestone matters because it’s hard to win, slow to achieve, and once secured, tends to stick.

Conclusion: From Paving Roads to Powering Teslas

Himadri Specialty Chemical’s story is, at its core, a story about industrial alchemy. A company that began by processing one of the steel industry’s messiest byproducts has spent more than three decades methodically climbing the value chain—until that same “black gunk” started to look like a strategic input to the clean-energy economy.

A big part of that arc runs through Anurag Choudhary. He joined Himadri at eighteen and spent the next three decades inside the details—customers, specs, processes, and the slow grind of building manufacturing credibility. Under his leadership, Himadri evolved from a coal tar pitch company into a broader specialty chemicals and advanced carbon materials platform. The company says it has positioned itself as an early Indian mover in lithium-ion battery materials, spanning both anode and cathode-side ambitions.

But this transformation wasn’t a straight line. There was the Icarus phase—debt-fueled expansion colliding with a macro shock. There was the long stretch when the market stopped caring and the real work began: deleveraging, tightening unit economics, and investing in R&D when it would’ve been easier to cut it. And there were the compounding decisions that don’t look dramatic on their own—building proprietary processes, protecting quality even at the cost of volume, and treating carbon not as a commodity, but as a discipline.

Whether Himadri becomes a globally significant battery-materials supplier is still an open question. Execution risk is real. Competition is brutal. Battery chemistry keeps evolving. But what’s also real is the foundation: decades of process know-how, feedstock access, and a manufacturing culture built around consistency—advantages you can’t conjure overnight with capital alone.

If you’re looking for the larger lesson, it’s this: Himadri didn’t “pivot to EV” because EVs became fashionable. It leaned into EVs because it had spent years becoming unusually good at carbon—and the world eventually made carbon strategic.

The last chapter isn’t written yet. But Himadri has already done something rare: it turned a regional, unglamorous, heavy-industry niche into a credible shot at a role in the global EV supply chain. For a family-run company that started by collecting waste from steel mills outside Kolkata, that’s not just reinvention. That’s earned ambition.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music