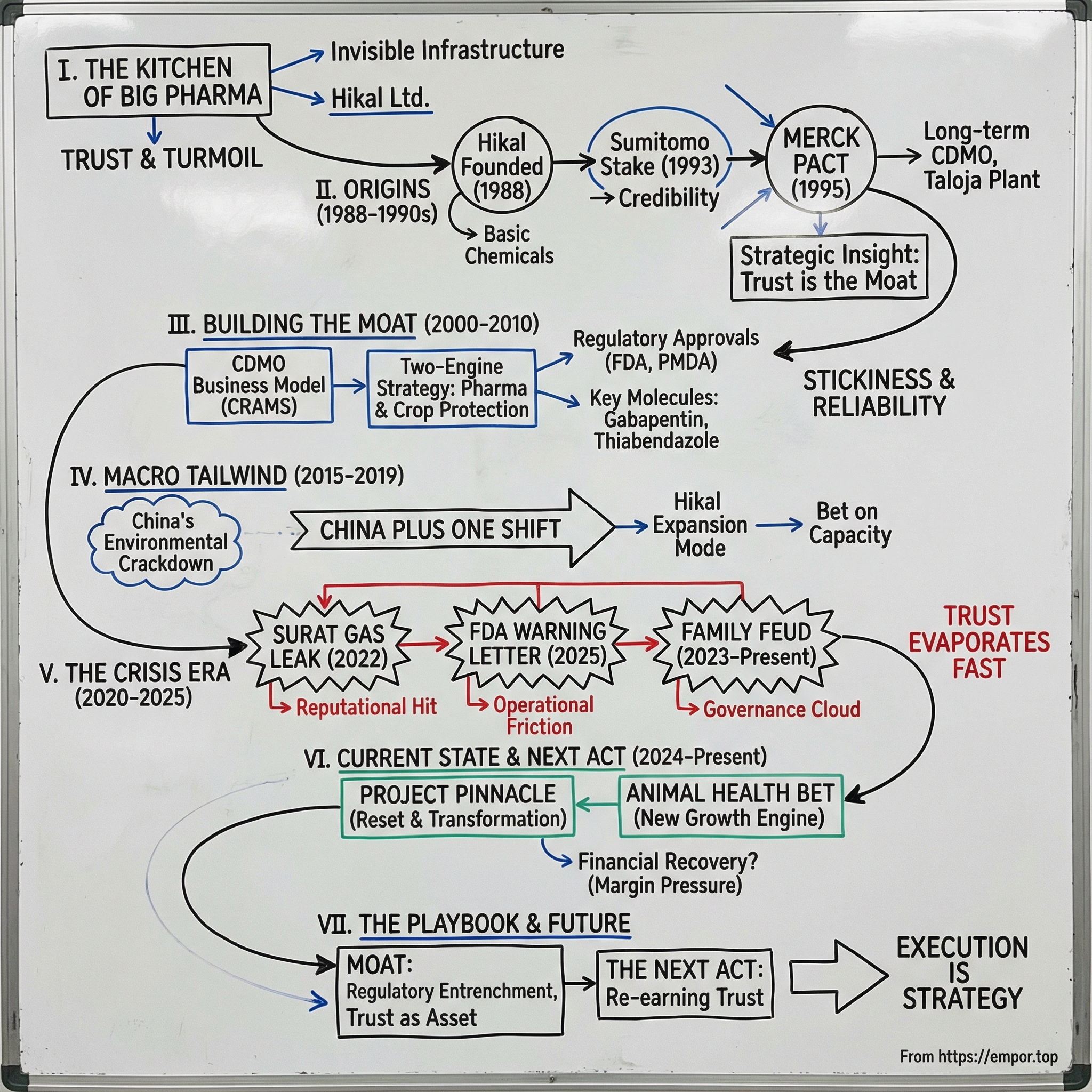

Hikal Ltd: The Chemistry of Trust & Turmoil

I. The "Kitchen" of Big Pharma

Picture a pill bottle in an American medicine cabinet. Maybe it’s Gabapentin for nerve pain, picked up at a pharmacy in Cleveland or Seattle. The patient twists the cap, swallows a capsule, and moves on with their day.

What they don’t see is the long chain behind that moment. There’s a decent chance the active ingredient in that capsule was cooked up thousands of miles away—inside a steel reactor in Maharashtra, India—by a company they’ve never heard of: Hikal Limited.

That’s Hikal’s world: invisible infrastructure. They sit behind the logos. Behind the brand names. They work with big pharmaceutical and crop protection companies, supplying research support, intermediates, and active ingredients—the kind of complex chemistry you can’t just source from anywhere and hope it works out. When Pfizer needs a specific molecule, when Bayer needs a fungicide ingredient made consistently at scale, when a Japanese innovator wants an anti-parasitic compound for animal health, companies like Hikal are the ones expected to deliver, quietly and flawlessly. These are the kitchens of Big Pharma: the back-of-house operations that do the hard, regulated work so the front-of-house can sell certainty.

And that’s why this story isn’t really about chemistry. It’s about what happens when the world stops being stable.

Because Hikal’s arc sits right at the intersection of three forces that don’t play nicely together: geopolitics that reshape supply chains overnight, regulation that punishes tiny mistakes like existential sins, and a family partnership whose origin story was literally baked into the company’s name.

Hikal isn’t a random string of letters. It’s a hybrid: the first two letters of Hiremath and three letters of Kalyani. The company was set up in the early nineties after the Hiremath family took a loan from Neelkanth Kalyani, the father of Baba Kalyani and Sugandha Hiremath.

The name itself foreshadowed the entanglement. And decades later, that entanglement would spill into public view as a boardroom and legal battle.

Zoom out, and you see the core rule of the CDMO business: the product you sell isn’t just a molecule. It’s trust. When a pharmaceutical company files a product with regulators using your manufacturing process, you’re no longer just a supplier. You’re part of their approval. Replacing you can mean years of rework, re-filings, audits, delays—millions in cost and the risk of blowing up a launch timeline. That’s the moat: once you’re in, you’re hard to swap out.

But trust has a brutal downside. It takes decades to earn and one incident to lose. A chemical leak. An FDA warning letter. A public governance meltdown. Any one of those can erase confidence faster than it was built.

Hikal’s journey captures that entire tension: the tailwind of “China Plus One,” the fragility of reputation in a hazardous industry, the promise of animal health as a growth engine—and the uniquely Indian drama of a public company caught in the crossfire of personal relationships and ownership rights.

One theme runs through all of it: in regulated chemicals, being boring and reliable is a superpower—until the boardroom stops being boring.

II. The Origins: From Surfactants to Strategy (1988–1990s)

Jai Hiremath was never the stereotype of a swashbuckling chemical baron. He was trained as a Chartered Accountant, qualified in India and in England and Wales, and later attended Harvard in 2002. But he chose a world that rewards the opposite of flash: regulated manufacturing, where consistency is the product and credibility is the currency.

He founded Hikal in Mumbai in 1988, in the closing years of India’s “License Raj,” when building anything industrial meant wading through permits, quotas, and bureaucracy. The early vision was straightforward—make basic chemicals, intermediates, dyes. Useful, unglamorous building blocks for industry.

Commercial production began in 1991 at the Mahad facility, manufacturing intermediates for dyes, pharmaceuticals, and agrochemicals. And like most companies that start in commodities, Hikal learned quickly what that life looks like: thin margins, relentless competition, and no real way to stand apart. If everyone can make the same molecule, the only lever left is price. And price wars don’t create great businesses.

Then came the first signal that Hikal might be building something different. In December 1993, Sumitomo Corporation of Japan—one of the world’s major trading houses—took an equity stake in the company. Hikal became the first chemical company in India in which Sumitomo invested, buying about 3.62%.

The money mattered. But the message mattered more. When a global Japanese institution puts its name next to yours, doors open. Your quality claims start sounding less like marketing and more like fact.

Still, the real turning point arrived two years later, in 1995, when Hikal entered a long-term contract manufacturing agreement with Merck, Sharpe and Dohme (MSD). This was for a veterinary and crop science product, and it wasn’t a small, “let’s see how it goes” pilot. The partnership led Hikal to build a significant greenfield production facility dedicated to the project—an investment of more than USD 35 million in the mid-1990s.

In context, that’s a huge swing. A relatively young Indian company convinced one of the most respected names in global pharma to trust it with critical manufacturing—and to do it through deep technical collaboration. Merck didn’t just place orders. It worked with Hikal on process and plant design, effectively lending Hikal a kind of reputational collateral that’s priceless in regulated industries.

The two companies signed a 10-year agreement—an unusually long commitment for a relationship that, in most cases, would have started with cautious trial batches and endless audits. The molecule at the center of it was Thiabendazole, an anthelmintic and fungicidal compound used across crop protection and veterinary applications.

Hikal built the Taloja plant in technical collaboration with Merck, and it became the only fully integrated plant in the world to produce Thiabendazole. Over time, Thiabendazole became one of Hikal’s key crop protection products (accounting for less than 15% of sales), used on grapes, potatoes, tobacco, and vegetables—and Hikal grew into the world’s largest supplier of it.

This was the moment Hikal’s identity snapped into focus. It wasn’t trying to be just another chemical maker. It was trying to become the kind of partner that global innovators could build around.

Corporate milestones were stacking up too. The company went public in 1994, was listed on Indian exchanges in 1995, and later renamed Hikal Limited in 2000. Going public brought capital and visibility—but also a level of scrutiny and formal governance that would, years later, prove to be both protection and pressure.

The Merck relationship also revealed the strategic insight that would define Hikal’s long game: in the CDMO world, once you’re embedded in a customer’s process and regulatory ecosystem, you’re not easily replaced. Switching isn’t just a procurement decision; it’s a multi-year exercise in re-validation and regulatory risk.

Hikal’s earliest value creation didn’t come from scaling commodity output. It came from locking in trust—first with an equity signal from Sumitomo, then with a decade-long manufacturing marriage to Merck. That’s where the company started to move from competing on price to competing on reliability.

III. Building the Moat: The Business Model of "Stickiness" (2000–2010)

By the early 2000s, Hikal had a clear idea of what kind of company it wanted to be. Not a faceless “job shop” that simply takes an order and runs a batch. A partner that helps take a molecule from “this works in a lab” to “this can be made safely, consistently, and at scale.”

That’s where the industry’s acronym soup comes in: CRAMS and CDMO. In plain English, it means companies hire Hikal to do the hard part they can’t—or don’t want to—do themselves: develop the manufacturing process and then run it, year after year, under unforgiving quality and regulatory expectations. Hikal’s work spans contract research, custom synthesis, and custom manufacturing of APIs and intermediates.

The key is that scaling chemistry is not just “make more.” A synthesis route that behaves nicely in a beaker can fall apart in a reactor. Yields drop. Impurities spike. A step that’s safe at grams becomes dangerous at tons. So you need process chemists to redesign the route, engineers to translate it into equipment and controls, and quality systems that can withstand the scrutiny of global regulators. When Hikal does its job well, the customer isn’t just buying output. They’re buying confidence.

And that’s how Hikal used crop sciences as a passport into pharma. As the company put it:

"Hikal's successful track record as a reliable and quality supplier to the crop sciences industry gave us our entry into the pharmaceutical sector, as Big Pharma companies typically require the same quality standards from their suppliers, whether it relates to their crop sciences, veterinary, or human health divisions."

It’s a subtle point, but a powerful one. If you can meet the standards for chemicals that end up on food crops, you’re already speaking the language of discipline, traceability, and compliance. That credibility transfers. Hikal didn’t have to introduce itself to pharma as a newcomer; it could show up with receipts.

During this decade, the “Two-Engine” strategy also hardened into company doctrine. Hikal would run two major businesses—pharmaceuticals and crop protection—while nurturing animal health as an extension of the pharma engine. The logic wasn’t complicated: the cycles are different. Crop protection swings with seasons, commodity prices, and weather. Pharmaceuticals move to a different rhythm—regulatory approvals, patent cliffs, and healthcare demand. When one side gets choppy, the other can keep the ship steady. That diversification repeatedly helped offset pressure in any single segment.

To support all of this, Hikal expanded its footprint. It built out five manufacturing facilities across India—Taloja and Mahad in Maharashtra, Panoli in Gujarat, and Jigani near Bangalore in Karnataka—plus a Research & Technology center in Pune.

Two sites, in particular, mattered because they signaled something important to global customers: this wasn’t “India-quality.” This was global-quality.

Panoli came first. In 2000, Hikal acquired the facility from Novartis. That move was more than expansion—it was a shortcut through time. Novartis had already built the plant to international standards, and Hikal stepped into an asset designed for regulated work, producing key intermediates and regulatory starting materials. The site carried the approvals that matter in this business: US FDA, Japan’s PMDA, and EU certification.

Then came the Bangalore facility, which manufactured key pharma APIs and also earned approvals from the US FDA, PMDA, and European authorities. In a world where credibility is earned in audits and paperwork, those approvals weren’t administrative details. They were commercial weapons.

The relationships kept compounding, too. In 2008, Hikal entered a long-term manufacturing agreement with Bayer CropScience for active ingredients. It wasn’t just a contract; it came with real commitment. Hikal set up a new plant at Taloja specifically for Bayer’s needs, with supplies expected to begin in the second half of 2008.

By now, the customer list was starting to read like a roll call of global life sciences: Merck, Bayer, and other major relationships taking shape. And in this industry, one trusted logo tends to unlock the next. If you’re already making a critical ingredient for Bayer, your pitch to another innovator isn’t theoretical. It’s proven.

Underneath the customer names, Hikal’s portfolio was also taking on a more deliberate shape. In pharma (including animal healthcare), the business was split roughly 60:40 between APIs and CDMO work. In crop protection, about 70% of sales came from CDMO, with the rest from proprietary products, specialty chemicals, and specialty biocides.

Two anchor molecules became shorthand for what Hikal was building. On the pharma side: Gabapentin, used for epilepsy and nerve pain, where Hikal became one of the largest API suppliers. On the crop side: Thiabendazole, where Hikal was already a leading global supplier.

This wasn’t a decade of flashy expansion. It was a decade of becoming difficult to replace. Hikal focused on depth: the kind of know-how, compliance muscle, and customer integration that turns a supplier relationship into something closer to a long marriage. It might not maximize short-term growth in any given year, but it builds the one thing that matters most in regulated manufacturing: stickiness.

IV. The Macro Tailwind: The "China Plus One" Shift (2015–2019)

For decades, the global chemical industry ran on a simple assumption: if you needed something made at scale, you went to China. The country had become the default factory for everything from electronics to pharmaceutical intermediates, powered by a mix of cost advantages, vast capacity, and state support that was hard to match.

But by the mid-2010s, that certainty started to crack.

China’s environmental crackdown—often nicknamed the “Blue Skies” push—began shutting down polluting plants across the country. Chemical factories were hit especially hard. And because so much of the world’s supply chain flowed through those plants, the impact didn’t stay local. Shortages rippled outward. Raw materials got tight. Prices jumped. And Western multinationals that had over-optimized for “China at all costs” suddenly found themselves exposed.

That’s the moment “China Plus One” stopped being a consulting slide and became a procurement directive. The idea was straightforward: don’t bet your entire supply chain on one country. Add a second manufacturing base—India, Thailand, Vietnam—anywhere credible enough to reduce geopolitical and operational risk.

For Indian CDMO companies, this was the opening they’d been waiting for. As China’s upstream disruptions continued, customers started looking for partners who could step in fast, not just promise capacity someday.

Hikal was unusually well positioned for that call.

While some competitors were still pouring concrete and chasing regulatory approvals, Hikal already had FDA- and globally certified facilities and long-standing relationships with innovators. So when a Bayer or a Syngenta needed an alternative source, Hikal didn’t have to respond with, “Give us two years.” It could respond with, “Yes.”

And Hikal didn’t treat this as a temporary bump. It treated it like a cycle shift—and started building for it. The company moved into an aggressive expansion mode, investing to increase capacity across its businesses and prepare for a world where “China-only” sourcing would feel reckless.

That bet came with real risk. Building multi-purpose plants and scaling regulated capacity isn’t cheap, and if China’s supply base fully normalized, excess capacity could quickly turn into underutilized assets and a heavier balance sheet.

Zooming out, the broader logic behind the shift was hard to argue with. India had been steadily building a reputation as a reliable global manufacturing base for life sciences, backed by FDA-compliant facilities, a deep talent pool, and meaningful cost advantages. It wasn’t just a political hedge; it could be a structural upgrade.

But macro tailwinds don’t hand out guaranteed wins. The next phase of Hikal’s story would reveal whether the company could convert this historic opening into durable advantage—or whether shocks, scrutiny, and internal strain would get there first.

V. The Crisis Era: Accidents, FDA, and The Family Feud (2020–2025)

From 2020 through 2025, Hikal ran into the nightmare version of its own business model: the kind where trust doesn’t just compound slowly—it can evaporate fast. In regulated chemicals, you can do a thousand things right and still get defined by the one thing that goes wrong. For Hikal, the shocks didn’t arrive one at a time. They stacked.

The Surat Gas Leak Tragedy

Early on the morning of January 6, 2022, a gas leak tore through the Sachin industrial area in Surat, Gujarat. At least six people died, and more than twenty others fell sick. Reports said the leak came from a tanker parked in the Sachin GIDC area, and that the driver had been illegally dumping chemical waste into a drain, triggering the release of toxic fumes.

Hikal’s name entered the story through the supply chain. Investigators alleged the chemical involved—reported as sodium hydrosulphide—had been purchased from Hikal’s Taloja facility in Maharashtra under the pretext of selling it onward, before being illegally dumped in Surat. Media reports also said the crime branch detained three Hikal officials, along with the owner of a local mill, as the investigation widened into illegal waste disposal practices.

Hikal publicly pushed back on the implication that it was responsible for the leak. The company said the incident involved a different tanker, and later stated that there had been judicial recognition of the “non-existent role of Hikal and its employees,” referencing an order by the Gujarat High Court. The matter, Hikal noted, remained sub judice, and it maintained it was on strong legal footing.

But the market doesn’t wait for a final verdict. The episode dragged Hikal into a much larger, uglier conversation: how hazardous byproducts move once they leave the factory gate, and where corporate responsibility begins and ends. Even if Hikal wasn’t directly culpable for the dumping, critics argued that traceability and controls around hazardous material were part of the job—especially for a company whose entire value proposition is reliability.

The reputational hit was immediate. The stock fell sharply. ESG-focused investors backed away. And the incident became a brutal reminder of the industry’s reality: your risk isn’t only what happens inside your plant. It’s what happens because your product exists at all.

The FDA Warning Letter

If Surat challenged Hikal’s standing on environment and governance, 2025 hit the center of the bullseye: pharmaceutical quality.

After an inspection of Hikal’s Jigani API facility in Karnataka from February 3 to 7, 2025, the US FDA followed up with a warning letter. The agency cited failures in how Hikal investigated complaints of metal contamination in its products. The FDA said Hikal had initially received 22 complaints since 2020 related to metal contamination. The warning letter also stated that, even after Hikal’s own investigation, inspectors found 28 additional complaints of foreign material in products.

Markets reacted quickly. Hikal’s shares slipped after the company disclosed it had received the warning letter, and the company said it was working closely with the FDA to address the issues raised.

Operationally, the consequences showed up in the numbers soon enough. In May 2025, the Jigani facility received an Official Action Indicated (OAI) classification. And when Hikal reported Q1 FY2026 results on August 7, 2025, it cited a material decline in profitability, driven by deferred orders in the pharma division following that OAI outcome. The February inspection had also produced a Form 483 with six observations.

In a pharma CDMO business, this is the kind of event customers fear. A warning letter doesn’t just create extra paperwork; it creates uncertainty. If you’re a global client relying on that facility for U.S. supply, you don’t want “we’re fixing it.” You want “it’s fixed.” Orders get paused. New program awards get delayed. And the core asset Hikal sells—trust, in the form of consistent, regulator-ready output—takes a direct hit.

The Family Feud: A Shakespearean Battle

And then came the crisis that didn’t involve a plant, a regulator, or a tanker. It involved ownership—messy, personal, and public.

In 2023, a long-simmering dispute between the two families behind Hikal erupted into open litigation. Sugandha Hiremath and her husband, Jai Hiremath, moved the Bombay High Court against her elder brother, Baba Kalyani, and his family. The Hiremaths asked the court to enforce a 1994 family settlement under which the Kalyani faction would sell its entire stake in Hikal to the Hiremaths. Reports described the two factions as holding roughly equal stakes—about 34% each—in the company.

The backstory reads like destiny, because it’s embedded in the brand. Hikal was built with capital from the Kalyani family, and its name combines the two surnames: Hiremath and Kalyani. For decades, the arrangement held. The Kalyanis remained major shareholders and had a board presence. The families stayed aligned.

But the suit hinged on old family agreements from 1993 and 1994, which covered share distributions across multiple businesses and included the transfer of Hikal shares held by Baba Kalyani to his sister Sugandha. After the death of Sugandha’s mother in 2023, Sugandha and Jai sought enforcement of what they described as a long-standing arrangement. They alleged Baba Kalyani had defaulted on those commitments and was instead trying to strengthen his hold on the company.

Baba Kalyani’s position was that the 1994 document was merely a “note” by his father, Neelkanth Kalyani, and not legally binding. The case remained pending.

As the fight escalated, it spilled into the governance machinery of a listed company: exchange disclosures, competing statements, and a boardroom operating under the shadow of a courtroom timeline. Baba Kalyani’s 31-year tenure on Hikal’s board ended in January 2024, a symbolic turning point that made the dispute feel less like a private disagreement and more like a full-blown rupture.

By early 2025, the public back-and-forth continued. Kalyani Investments, a promoter entity, stated to the BSE that a disclosure Hikal made—based on a January 10, 2025 letter from Sugandha and Jai—was incorrect, emphasizing that it was a party to the March 2023 suit and aware of the pleadings and documents.

The next generation got pulled in too. In the dispute involving Baba Kalyani and his sister’s children, Baba submitted an affidavit arguing that Sameer and Pallavi Hiremath were not affiliated with the Kalyani joint family, since they did not have a common male ancestor. He said that, as members of the Hiremath family by birth, they lacked standing to litigate over the Kalyani Family HUF.

Meanwhile, the ownership remained plainly contested in public filings. Exchange disclosures showed Kalyani Investment Company and BF Investment holding 31.36% and 2.64% of Hikal shares, respectively.

This wasn’t just a family disagreement. It was a governance cloud hanging over a regulated business that depends on stability. Litigation turns every strategic decision into a potential landmine. It slows momentum, complicates capital allocation, and makes outsiders wonder who’s really in charge.

And the timing couldn’t have been worse. This was exactly the period when “China Plus One” should have been Hikal’s moment—when customers were looking to diversify, when capacity and credibility could translate into long-term contracts. Instead, Hikal had to fight on three fronts at once: reputation, regulation, and control.

VI. The Current State: Project Pinnacle & The Next Act (2024–Present)

Even after everything—Surat, the FDA scrutiny, the family fight—Hikal didn’t hit pause. Instead, it kicked off a transformation effort it calls “Project Pinnacle,” aimed at fixing the operational weak spots and setting the company up for its next leg of growth.

In its own words, the company framed Pinnacle as the start of a strategic reset: a program to strengthen the key pillars of the business and build a clearer path to the “next phase” over the coming years. Hikal said it partnered with a leading management consultant to define priorities and a new strategic direction for the next five years.

The initiative has moved in phases, and the company has since rolled out “Pinnacle 2.0,” with a sharper emphasis on front-end execution and operational excellence—tightening customer engagement and streamlining internal processes.

The Animal Health Bet

The biggest swing in this next act is animal health.

It’s an attractive pocket of the market for a CDMO: less exposed to the brutal pricing pressure of human generics, with long-term demand tailwinds from the “humanization” of pets and rising protein consumption in developing economies.

Hikal commissioned a new multipurpose animal health facility at Panoli, Gujarat, during the third quarter, and began validation work across several products—work it expected to complete over the next few quarters. The company also said it anticipated gradual growth in animal healthcare as validations from the Panoli facility, commissioned in December 2023, were successfully completed.

This isn’t being positioned as a one-off capacity add. Hikal described it as part of a 10-year, multi-product project with a global innovator, with process development for multiple active ingredients on track. A decade-long program like that is the CDMO version of “you’re in the inner circle”—a relationship that’s built to last, not a spot purchase order.

And there’s an important detail Hikal highlighted: it has developed eight products intended for global supply, and it said it is free to sell those products worldwide to any customer that needs them.

Financial Recovery

On the surface, the latest full-year results suggested a business stabilizing. Hikal reported operating income of Rs. 1,784.6 crore in FY2024 and Rs. 1,859.8 crore in FY2025, with PAT of Rs. 69.6 crore in FY2024 and Rs. 90.8 crore in FY2025. Management characterized FY2025 as a year of positive performance, pointing to revenue of about Rs 1,860 crore and EBITDA of Rs 328 crore, translating to a 17.7% margin.

The mix also remained consistent with what Hikal has been building toward for years: pharma as the primary engine. The pharmaceutical segment contributed about 62% of revenues in FY2024 and in 9M FY2025, with the remainder coming from crop protection.

But near-term reality snapped back hard in Q1 FY2026. Revenue came in at Rs 380 crore versus Rs 407 crore a year earlier. EBITDA dropped to Rs 25 crore from Rs 58 crore, with margin compressing to 6.5%. PAT swung to a loss of Rs -23 crore, compared to a profit of Rs 5 crore in Q1 FY2025.

That’s the warning-letter hangover showing up in real operating results. Deferred orders, paused decisions, slower ramps—the exact knock-on effects you’d expect when a regulated customer base gets cautious.

Management’s message, though, was that the damage was containable. Hikal said it had not seen order cancellations after customer visits and audits, and expected to recoup the lost revenue in H2 FY2026.

VII. The Playbook: How CDMO Moats Work

To understand Hikal’s competitive position, you have to understand how moats actually get built in a CDMO business. It’s not the Silicon Valley version of defensibility—no consumer brand, no viral distribution, no patent portfolio you can point to and relax.

In this world, the moat is made of two things: regulatory entrenchment and trust.

High Switching Costs (The "Velcro" Effect)

Once Hikal is written into a customer’s Drug Master File (DMF) with the FDA, it stops being “just another supplier.” Swapping them out isn’t a sourcing exercise. It’s a regulated project.

A customer has to amend filings, run stability studies, re-validate processes, and potentially invite new inspections—all while risking supply disruption or launch delays. In practice, that can take two to three years and cost millions of dollars.

That’s what creates the “velcro” effect. Customers aren’t trapped because they’re happy; they’re stuck because the act of leaving is expensive, slow, and full of ways to go wrong. Or as Hikal put it in its own words: “In the long run, we however consider that the difficult times experienced by the Indian industry will emerge as a window of opportunity for companies like Hikal: customers have become far more selective when it comes to choosing their Indian partners.”

Trust as an Asset Class

In B2B CDMO, price matters—but it’s rarely the main thing. What customers are really buying is the confidence that the plant won’t have a serious incident, won’t get shut down by regulators, and won’t ship product that triggers recalls or warning letters.

That’s why Hikal spent decades building a reputation around quality systems, compliance, and consistency. And it’s also why the FDA warning letter landed like a punch to the chest. It didn’t just create operational friction. It challenged the core promise Hikal sells: regulator-ready reliability.

The "Long Marriage" Model

Hikal also plays a different game than commodity chemical companies that live and die by spot prices. Its model leans heavily on long-term commitments.

Merck began as a 10-year agreement. Bayer was framed as a long-term manufacturing relationship. The newer animal health partnership is described as a 10-year, multi-product program.

The tradeoff is simple: you give up some short-term price optimization in exchange for durability—revenue visibility, deeper integration, and relationships that are harder to unwind. In an industry where volatility is constant and mistakes are punished, boring predictability is a feature, not a bug.

VIII. Analysis: Power & Forces

Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework

Switching Costs (Primary Power): This is the big one, and it’s the reason CDMOs can feel “sticky” even when relationships get tense. Once Hikal is baked into a customer’s regulatory filings, replacing them isn’t a vendor swap. It’s a multi-year, regulator-facing project that most customers will avoid unless they absolutely have to.

Process Power (Secondary Power): The moat isn’t just approvals; it’s the accumulated manufacturing know-how that sits inside Hikal’s plants and teams. Molecules like Thiabendazole and Gabapentin aren’t won by being the cheapest bidder—they’re won by being able to run a process safely and consistently, at scale, with the right impurity profile. Hikal’s Taloja plant in Maharashtra, for example, is described as the only fully integrated facility in the world producing Thiabendazole. That kind of integration is hard to replicate quickly.

Network Effects: Limited. There’s no flywheel where each new customer makes the service more valuable for the next. This is closer to industrial craft than software.

Counter-Positioning: There is a real structural shift working in Hikal’s favor. Big Pharma’s legacy model was to manufacture a lot in-house. Over time, many of these companies have chosen to focus on R&D and commercialization and push manufacturing to specialists. CDMOs like Hikal are, in effect, the counter-position to the old vertically integrated pharma giant.

Porter’s 5 Forces

Threat of New Entrants (Low to Medium): The headline barrier isn’t money—it’s time, and the ability to survive the regulatory grind. Getting FDA-ready facilities up and running can take five or more years, and that assumes you already know how to build quality systems that stand up to scrutiny. Indian peers like Syngene, Neuland Labs, and Divi’s have been converting RFQs into pilots and early contracts over the last year or so, but meaningful financial impact tends to show up on a longer, three-to-five-year horizon.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (High): Hikal sells to giants—Pfizer, Bayer, Syngenta—buyers with world-class procurement teams and plenty of alternatives. They negotiate hard, they demand performance, and they rarely overpay. For Hikal, that means it often behaves more like a price-taker than a price-maker.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Moderate): Inputs can swing, especially when supply chains get disrupted. That volatility flows through to profitability, and Hikal has felt it. Management has pointed to demand softness and pricing pressure as contributors to lower operating margins—around the mid-teens in FY2024 and 9M FY2025 versus the high-teens range it had delivered historically.

Threat of Substitutes (Low): For most of what Hikal makes, there’s no magical workaround. APIs and crop-protection actives still need to be synthesized through validated chemical routes. You can switch suppliers, but you can’t switch away from chemistry.

Competitive Rivalry (High): This is a crowded, competitive arena. Indian CDMO has plenty of capable players, and Hikal competes with firms such as Laurus Labs, Symbiotec, and Neuland. The fight is constant—on quality track record, capacity, delivery, and price.

Peer Comparison

Hikal sits in the middle of India’s CDMO landscape. It’s not a scale behemoth like Divi’s Laboratories, and it isn’t as singularly associated with agrochemicals as Pi Industries. Yet it has what many companies want: Tier 1 customers and long-standing relationships.

And still, for shareholders, it has often read as a story of frustration. Relative to some peers, Hikal’s stock returns have disappointed.

The reasons are consistent with the story you’ve just lived through: margins that haven’t held up as well, a long-running family dispute that created a governance overhang, and a series of crises that bruised trust at exactly the wrong time. The open question now is whether those were temporary shocks the company can work through—or signals of deeper, structural disadvantages.

IX. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bear Case

Regulatory Risk is Existential: The FDA warning letter was a reminder of how quickly regulatory issues can derail a CDMO. If deviations aren’t resolved, the FDA can escalate—up to refusing admission of products made at Hikal’s Jigani facility into the U.S. under section 801(a)(3) of the FD&C Act. In the worst case, a facility landing on import alert can effectively cut off a major market and wipe out revenues tied to that site almost overnight.

Agrochemicals are Cyclical: Crop protection lives and dies by forces Hikal can’t control—weather, planting cycles, and commodity prices. The broader industry has also been dealing with subdued demand as channel inventories work their way down, plus intense price erosion as competitors, especially in China, fight for volume with under-utilized capacity.

The "China Comeback": “China Plus One” created a massive opening for India, but it isn’t a one-way street. If China leans back into subsidizing chemicals, or if environmental enforcement softens, pricing pressure can return fast. And for many multinationals, China still sits at the top of the list because it can deliver cost efficiency and supply consistency at scale. Meanwhile, tariffs and trade-policy shifts can complicate both China and India as sourcing hubs.

Governance Concerns: The dispute between the families may have cooled from its peak, but the underlying overhang hasn’t vanished. Baba Kalyani and Sugandha Hiremath, along with Jai Hiremath, have been locked in a legal battle over ownership and control—exactly the kind of uncertainty that makes customers and investors uneasy in a trust-based business.

Debt Levels: The expansion cycle wasn’t free. With capex partly funded through long-term borrowing, debt remained elevated—total debt (including lease liabilities) stood at Rs. 773.5 crore as of September 30, 2023—limiting flexibility at the exact moment the business needed operational breathing room.

The Bull Case

China Plus One is Secular: The move away from China isn’t just a short-term procurement trend—it’s a multi-decade supply-chain rewiring driven by geopolitics, ESG pressure, and resilience. India’s pharma and biotech ecosystem has already started seeing the payoff, with earlier enquiries and RFQs converting into pilot projects and smaller contracts that can later scale.

Governance Cloud is Lifting: With Baba Kalyani exiting the board and promoter ownership appearing more consolidated, the biggest source of governance uncertainty may be moving into the rearview mirror—allowing management to focus on operations rather than court filings and public disputes.

Animal Health is the Sleeping Giant: Animal health can be a structurally better CDMO market—typically higher margin and less exposed to the brutal pricing pressure of human generics. Hikal expects gradual growth here over the medium term, supported by the animal healthcare manufacturing facility it commissioned in December 2023.

Margin Recovery Potential: If the new facilities ramp smoothly and the FDA situation gets resolved, there’s a credible path back toward Hikal’s historical operating margin range of 17–19%.

Valuation: With a market cap of about Rs. 2,983 crore, a lot of the recent damage looks reflected in the price. If execution improves and confidence returns, the upside can be meaningful.

X. Key Metrics to Monitor

If you want to know whether Hikal is genuinely turning the corner—or just treading water—there are three indicators that matter more than any single quarter’s headline.

1. EBITDA Margin Trajectory

Over the last few years, softer demand and pricing pressure pulled profitability down. Operating margins slipped to about 15% in FY2024 and 15.7% in 9M FY2025, below the 17–19% range Hikal delivered historically.

The cleanest proof that Project Pinnacle and the new capacity are working is a steady climb back toward that historical band. If margins expand, it likely means three things are happening at once: plants are running fuller, the mix is improving, and the newer animal health and multipurpose assets are starting to carry their weight.

2. FDA Resolution Status

Jigani’s regulatory situation is, in practical terms, a pass/fail test. Either Hikal satisfies the FDA’s concerns and normalizes customer confidence—or it escalates, potentially as far as an import alert, which would be a major blow to U.S.-linked supply.

So the signals to watch are straightforward: what the company discloses about remediation, what happens in subsequent inspections, and—most revealing of all—whether customers keep placing orders or stay in “wait and watch” mode.

3. Animal Health Revenue Contribution

This is the growth engine Hikal is trying to build its next chapter around. The company said it has received validation for eight products, and the plan is for those to move from validation into commercialization as the 10-year partnership with a global animal health innovator scales.

The question isn’t whether animal health sounds attractive on paper. It’s whether it shows up in the mix. If this bet is paying off, you should see the segment go from a rounding error to a meaningful share of revenue—and, ideally, do it with a healthier margin profile than the base business.

XI. Concluding Thoughts

Hikal’s story is, in a lot of ways, a proxy for Indian Manufacturing 2.0: the shift from low-cost output to complex chemistry, regulated plants, and the kind of “boring reliability” the world’s biggest life-sciences companies will actually build around. Hikal itself frames the ambition in simple terms—global, sustainable, innovative fine chemical technology, Made in India—and Project Pinnacle is its attempt to make that ambition operational, not aspirational.

On the best days, Hikal proves the point. An Indian company can run to global quality standards, earn the confidence of demanding pharmaceutical and agrochemical giants, and turn supplier relationships into decade-long marriages that are hard to unwind.

But the last few years also revealed the dark side of the model—how quickly the trust account can be drained.

The family dispute showed how a listed company can get pulled off course when ownership and personal relationships collide. The Surat tragedy showed how ESG risk doesn’t stay neatly contained inside a factory gate, and how reputational damage can arrive long before legal clarity. The FDA warning letter showed the harshest rule in pharma manufacturing: credibility is fragile, and regulators don’t grade on a curve.

The opportunity set is still there. “China Plus One” remains real. Animal health still looks like a smart place to build a higher-quality growth engine. Project Pinnacle is aimed at the right targets. But none of that is self-executing. Hikal is trying to do several hard things at once: remediate regulatory findings, ramp new capacity, hold ground in a tough crop protection market, and operate under the shadow of an unresolved promoter dispute.

So the real question isn’t whether Hikal has a moat on paper. It does—switching costs, regulatory approvals, and relationships built over decades. The question is whether that moat still holds when it’s stressed.

Because moats can erode. And in this business, the thing you’re ultimately selling isn’t chemistry. It’s trust.

In a world that’s increasingly uneasy about concentrated supply chains, Hikal’s next act will come down to one test: can it re-earn the right to be the “reliable alternative” customers choose—and then stick with? The next few years will tell us whether this is a durable turnaround, or a reminder that in regulated manufacturing, execution is the strategy.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music