GAIL (India): The Quiet Giant of India's Energy Infrastructure

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

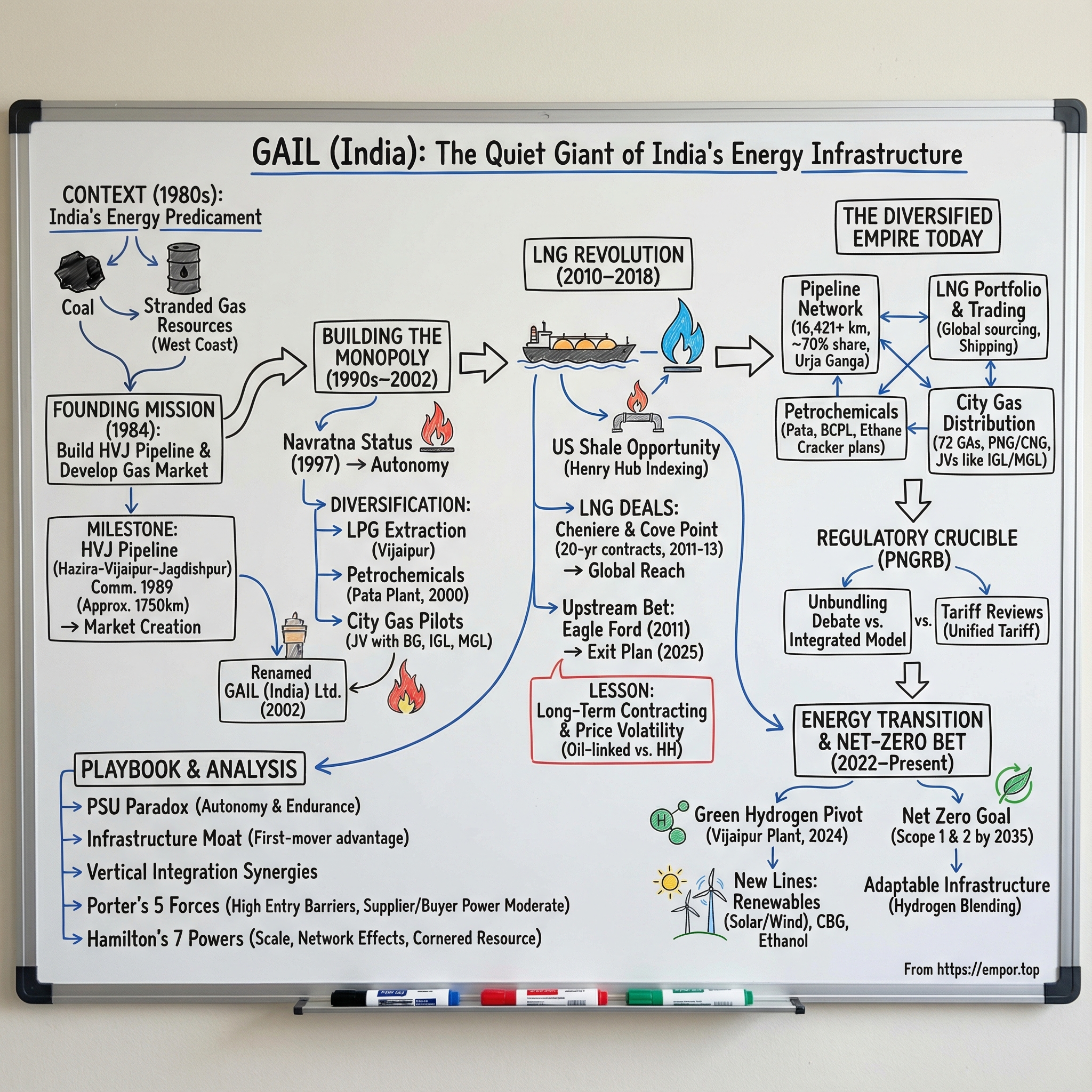

Picture this: every day, more than 160 million cubic metres of natural gas moves quietly through a hidden web of steel arteries across India. It powers factories, feeds fertilizer plants that support a billion people, and fuels power stations that keep the lights on—from Gujarat’s industrial belt to the megacities of Delhi and Mumbai. The flow never stops. And yet, ask most investors about the company that moves so much of it—GAIL (India) Limited—and you’ll often get a blank look.

GAIL transmits more than 160 million cubic metres of gas per day (at standard conditions) through its pipeline network, and it holds more than 70% market share in both gas transmission and gas marketing. That’s near-monopoly influence over a critical national utility—paired with the kind of public-sector complexity that can make the story easy to overlook. The result is a strange paradox: one of the most dominant infrastructure businesses in the country, hiding in plain sight.

The question at the heart of this story is simple: how did a government-mandated pipeline operator—born in the 1980s to build essentially one backbone line—turn into India’s energy spine? And the follow-on question is even more interesting: can a state-owned monopoly reinvent itself for the net-zero era?

GAIL began life as the Gas Authority of India Ltd., incorporated in August 1984 as a Public Sector Undertaking under the Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas. Its initial mandate was clear: build, operate, and maintain the HVJ gas pipeline. The mission statement was straightforward but sweeping—“accelerating and optimizing the effective and economic use of Natural Gas and its fractions for the benefit of the national economy.” What no one could fully see then was how that one mandate would expand into an entire ecosystem: pipelines, petrochemicals, LNG trading, city gas distribution—and now, green hydrogen.

Along the way, a few big themes keep showing up.

First is the paradox of a monopoly that actually works: how GAIL built real capabilities and scale while operating under government ownership and oversight. Second is infrastructure as destiny: how an early, audacious pipeline build created a moat that’s still shaping India’s gas market decades later. Third is the LNG gamble: the decision to lock in long-term contracts for American shale gas—deals that, depending on the year, looked either genius or disastrous, sometimes both. And finally, the question hanging over everything: energy transition. What does “reinvention” look like for a company whose core purpose has been moving fossil fuels?

This isn’t the story of a company fading into irrelevance. In FY 2024, GAIL reported annual revenue of Rs 1,30,638 crore, profit before tax of Rs 11,555 crore (up 75% from FY23), and profit after tax of Rs 8,836 crore (up 67%). However you feel about the role of state-owned enterprises, those are the results of a business with leverage, scale, and momentum.

Understanding how GAIL got here—and what could disrupt it next—offers a masterclass in PSU dynamics, energy geopolitics, infrastructure moats, and the peculiar competitive reality of a regulated natural monopoly.

II. India's Gas Vision: Context & Founding (1980s)

Setting the Stage: India's Energy Predicament

To understand why GAIL exists, you have to go back to India in the early 1980s. The country ran on coal, relied heavily on imported oil, and had just lived through two decades-defining wake-up calls: the oil shocks of 1973 and 1979. Energy security wasn’t an abstract policy goal. It was a national vulnerability.

At the same time, natural gas was starting to look like a way out. Discoveries in western India—especially Bombay High offshore and the South Bassein gas fields—hinted at a cleaner, domestic fuel that could power industry and reduce exposure to global crude markets.

But India had a classic “stranded resource” problem. The gas was on the coast. The demand—the fertilizer plants, power stations, and factories that mattered most—sat hundreds of kilometres inland, especially across northern India. Without a pipeline network, gas might as well have stayed underground.

Solving that gap required more than incremental planning. It required a single, audacious piece of national infrastructure: a cross-country pipeline on a scale India had rarely attempted. The plan was enormous for its time—about 1,750 kilometres, one of the largest natural gas pipeline projects in the world, built at a cost of ₹17 billion (about US$200 million). And it wasn’t merely a construction project. It was the beginning of an entirely new energy market.

The HVJ Pipeline: India's Energy Artery

That pipeline was the Hazira–Vijaipur–Jagdishpur line—HVJ. It became the project that defined GAIL, and in many ways, it helped define modern India’s gas economy.

Construction began in June 1987 and the line was energised by July 1989—an unusually fast build for something of that size and complexity.

The brilliance wasn’t just speed. It was the route. HVJ linked Hazira in Gujarat—fed by western gas supplies—into the heart of North India via Vijaipur in Madhya Pradesh and onward to Jagdishpur in Uttar Pradesh. In practical terms, it connected gas molecules to the places where they could actually change the economy: fertilizer production, industrial fuel, and eventually, power generation. It didn’t just move gas. It moved industrial competitiveness inland.

GAIL was originally entrusted with building, operating, and maintaining the HVJ project—one of the largest cross-country pipeline builds anywhere. The line initially spanned roughly 1,800 kilometres and was constructed at an initial cost of about Rs 1,700 crore, laying the groundwork for India’s natural gas market.

Why This Matters: Creating a Market, Not Just a Pipeline

Here’s the part that’s easy to miss if you only focus on steel and kilometres: HVJ wasn’t just infrastructure. It was market creation.

Before HVJ, there wasn’t a meaningful natural gas market in India at all. Industrial buyers didn’t have established procurement habits. Pricing systems were underdeveloped. Distribution networks were minimal. Safety standards, technical skills, and operating playbooks weren’t widely institutionalized.

So GAIL had to do two jobs at once. It had to build the physical network—pipelines, compressor stations, operations. And it had to build the commercial world around it: educating customers, setting up contracts, defining processes, and making gas a fuel Indian industry could trust and plan around.

That foundational role—builder and market maker—is why GAIL has remained central. Since its inception in 1984, it became the dominant force in marketing, transmission, and distribution of natural gas in India, instrumental in developing the market itself.

And once you’re first in a natural-monopoly business, the advantage compounds. Rights-of-way get harder over time, not easier. Costs rise. Networks interlock. Customers build their operations around the grid that already exists. When GAIL built HVJ, it didn’t just lay pipe. It set the architecture that future pipelines would connect into—and the ecosystem that customers would grow inside.

That’s the moat, born in the 1980s: not a single asset, but a system.

III. Building the Monopoly: Expansion & Diversification (1990s–2002)

The Navratna Era: Freedom to Act Like a Corporation

By the early 1990s, GAIL had done the hard part: it proved India could build and run a cross-country gas backbone. Now came the more interesting question—what do you do once you’ve built the highway?

The Indian government’s answer, at least for its best-performing PSUs, was to loosen the leash. On 1 January 1997, GAIL was awarded Navratna status, citing its “excellent track record” and “potential to become a global giant.” In plain terms, Navratna status meant more autonomy: more freedom to invest, form joint ventures, and pursue opportunities without having to route every decision through layers of government approval.

For GAIL, this was a structural turning point. It could keep the credibility and stability of government ownership, but start behaving more like a corporation—with a mandate to expand, not just operate.

Strategic Diversification: Beyond Pipelines

There’s a basic reality about pipeline businesses: they’re phenomenal at producing steady cash flows, but they’re not designed for fast growth. A pipeline has a fixed route and a fixed capacity. Once you’ve built the asset, the next leap isn’t automatic.

So GAIL started widening the definition of “gas business.” Instead of only transporting molecules, it moved into extracting, processing, and upgrading them—turning infrastructure into an integrated value chain.

One early move came even before Navratna. In November 1988, GAIL received approval to build an LPG extraction plant at Vijaipur, with capacity of 400,000 tonnes per annum. Phase I (200,000 tonnes per annum) was commissioned in 1990–91—eight months ahead of schedule. The logic was elegant: if you already handle natural gas, extracting LPG and monetizing it is one of the most direct ways to create a second stream of value from the same upstream flow.

Then came the bolder step: petrochemicals. In March 2000, GAIL commissioned a petrochemical plant at Pata in Uttar Pradesh, designed to process 300,000 tonnes of ethylene and produce 260,000 tonnes of HDPE and LLDPE. This was a different level of ambition. Instead of being paid to move fuel, GAIL was now converting gas into polymers—products tied to manufacturing, consumer goods, packaging, and construction.

Pata also gave GAIL something strategically rare: a major polymer footprint in the north. It remains the only HDPE/LLDPE plant operating in Northern India, and its entry helped catalyze downstream polymer processing in the region—an industrial ecosystem that had historically been concentrated further west.

The City Gas Distribution Bet

If petrochemicals were the move up the value chain, city gas was the move down it—right to the customer’s kitchen and the vehicle’s fuel tank.

GAIL entered city gas distribution through partnerships. On 6 December 1994, it signed a joint venture agreement with British Gas to create Mahanagar Gas Limited for the Bombay City Gas Distribution project. The combination mattered: British Gas brought mature city-gas know-how; GAIL brought the domestic network, supply access, and the credibility to work through Indian policy and local execution.

Then GAIL began testing the model in the capital. In 1997, it launched a city gas distribution pilot in New Delhi by setting up nine CNG stations. In 1998, it formed Indraprastha Gas with Bharat Petroleum and the Government of Delhi to build out the Delhi gas distribution network.

The bet was quietly prescient. Indian cities were heading toward an air-quality crunch, and regulators were going to need cleaner fuels they could deploy at scale. CNG for vehicles and piped natural gas for households fit that bill. By planting flags early in Delhi and Mumbai—through IGL and MGL—GAIL positioned itself ahead of a demand wave that would later become a policy priority.

Those early metro pilots became proof points. The city gas projects moved from experiment to commercial operations, and their impact was visible—especially in the air quality conversation. On the back of that success, GAIL went on to set up six more joint venture companies in city gas.

The Renaming: Identity Shift

By the early 2000s, “pipeline authority” no longer described what the company had become. On 22 November 2002, the Gas Authority of India was renamed GAIL (India) Limited.

It reads like a cosmetic change, but it captured a real transition: from a single-mandate infrastructure builder to an integrated gas and energy company. Transmission remained the backbone—stable, regulated, and moat-like. But around it, GAIL had assembled a broader machine: LPG extraction, petrochemicals, and city gas distribution, each expanding the surface area of the business while still feeding off the same underlying advantage—control of the network.

IV. The LNG Revolution: GAIL's Global Gambit (2010–2018)

Inflection Point #1: The US Shale Gas Opportunity

By the late 2000s, GAIL ran into a problem that no amount of pipeline-building could solve on its own: India’s appetite for natural gas was growing faster than domestic production. If gas was going to keep expanding as a fuel for power, fertilizer, and industry, India would need imports—at scale.

Then, halfway around the world, the U.S. shale boom rewrote the rules. Hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling unlocked huge new supplies, and American gas prices fell hard. The benchmark was Henry Hub, and compared with what Asian buyers were paying for LNG from traditional suppliers like Qatar and Australia—often linked to crude oil—Henry Hub looked almost unreal.

For GAIL, the opportunity was straightforward: if you could secure long-term LNG tied to Henry Hub instead of oil, you could import gas at a structural cost advantage. In other words, this wasn’t just “buy LNG.” This was a chance to buy a different pricing system.

The Cheniere & Cove Point Deals: A Masterclass in Energy Sourcing

In December 2011, GAIL swung big. It signed a 20-year LNG sale and purchase agreement with Cheniere, agreeing to buy about 3.5 million tonnes per year from Sabine Pass (train four). The bold part wasn’t just the size—it was the timing. GAIL was committing years in advance, before the U.S. export machine had fully proven it could be built and run at scale.

The structure mattered. GAIL’s purchase price was indexed to the monthly Henry Hub price, plus a fixed component. Cargoes were on an FOB basis—meaning GAIL would take delivery at the terminal and lift the LNG on its own ships. The contract ran for 20 years from first commercial delivery, with an option to extend up to another 10.

Then came the second pillar. In April 2013, GAIL signed another 20-year deal—this time for about 2.3 million tonnes per year from Dominion’s Cove Point liquefaction project in Maryland. (In the project’s marketed capacity, the other half went to a joint venture of Sumitomo Corporation and Tokyo Gas.)

Put together, these contracts made GAIL one of the largest Henry Hub–indexed LNG portfolio holders globally—about 5.8 mtpa from the U.S., split between Cheniere’s Sabine Pass in Louisiana and Cove Point (now part of Berkshire Hathaway Energy’s portfolio).

Going Upstream: The Eagle Ford Investment

GAIL didn’t stop at buying LNG. It also decided to own some of the source.

In September 2011, it incorporated a wholly owned U.S. subsidiary—GAIL Global (USA) Inc., in Texas—to invest in shale assets. That same year, GAIL acquired a 20% interest in an Eagle Ford shale position for about $95 million, and committed to further development spending of $300 million over five years.

The logic was classic commodity strategy: build a hedge into the system. If Henry Hub prices rose, GAIL’s LNG bills would rise too—but the value of upstream production would also improve. If prices stayed low, LNG would be cheap and the import advantage would persist. Either way, the upstream stake was meant to provide both supply exposure and protection.

In practice, it was harder. With gas prices depressed, returns didn’t match expectations. And in early 2025, GAIL announced plans to exit the Eagle Ford investment, following other Indian companies that had also stepped back from U.S. shale positions.

The Strategic Logic: Hedging & Price Arbitrage

The real test of the U.S. strategy began in 2018—when the molecules finally started moving.

Cheniere and GAIL marked the start of their 20-year agreement on March 1, 2018, with supplies from Sabine Pass. Commercial deliveries from Cove Point began the next month, in April 2018. After years of construction timelines and uncertainty, GAIL’s American LNG bet became operational.

And almost immediately, the bet revealed its double edge.

These Henry Hub–linked contracts weren’t just “Henry Hub.” They also carried fixed liquefaction fees—costs that don’t disappear when markets turn. For example, LNG under the Cheniere arrangement worked out to 115% of Henry Hub plus a fixed liquefaction fee of $3/MMBtu. When oil prices collapsed in 2014–2016 and again during COVID, oil-linked LNG could look cheaper, and GAIL had to lean on swap deals and active portfolio management to stay flexible.

Then the cycle turned again. When energy prices surged after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the original logic snapped back into focus: Henry Hub–indexed supply could look extremely attractive versus expensive oil-linked LNG in Asia. The arbitrage GAIL had been aiming for showed up—dramatically.

This is the hidden lesson of the LNG chapter. Long-term contracts are not “good” or “bad” in isolation—they’re massive, timed exposures. Depending on where oil, gas, and freight land, the same deal can look like a mistake one year and a masterstroke the next.

What insulated GAIL, at least partially, was portfolio thinking. The company didn’t bet on one source or one index alone. Alongside its U.S. commitments, GAIL maintained a broader LNG book—contracted volumes from Australia, Qatar, the U.S., and traders like Vitol and Adnoc—so it could balance Henry Hub–linked supply, oil-linked contracts, and spot purchases as market conditions changed.

V. The Regulatory Crucible: PNGRB & the Unbundling Debate (2006–Present)

Inflection Point #2: The Threat of Deintegration

Every monopoly eventually runs into the same counterforce: a regulator with a crowbar. For GAIL, that crowbar has a name—unbundling.

The Petroleum Ministry has periodically examined splitting GAIL into two separate businesses: one for transporting gas through pipelines, and another for marketing and selling it. The core argument is conflict of interest. If the same company both owns the highway and runs the biggest fleet of trucks on it, everyone else worries the toll booth won’t be neutral.

That tension surfaced in the open. At an “Open House” convened by India’s gas regulator, the Petroleum and Natural Gas Regulatory Board (PNGRB), on July 17 to discuss a “unified” or “pooling” method for gas transmission tariffs, GAIL found itself facing a formidable alignment of global majors. Shell pushed for “legal unbundling” of gas trading and transmission so benefits flow to all shippers. BP went further, arguing unified tariffs should come only after an entity’s transmission and marketing functions are split.

This wasn’t just foreign companies taking potshots. It was a broader belief—drawn from Europe’s playbook—that you don’t get a truly competitive gas market until the pipes and the trading desk live in different companies.

The PNGRB Dynamic

PNGRB, created under the PNGRB Act of 2006, is the referee here. It’s a sector regulator with quasi-judicial powers, responsible for approving pipelines, setting tariffs, and enforcing the idea that pipeline access should be non-discriminatory.

After extensive stakeholder consultations and committee recommendations, PNGRB introduced a Unified Tariff for natural gas pipelines under the slogan “One Nation, One Grid and One Tariff.”

This is a meaningful shift. Historically, pipeline charges were heavily distance-based—bad news for customers far from the coast or major hubs. Unified tariffs pool costs across the network, aiming to make gas more viable in far-flung regions and accelerate the build-out of a national gas grid. In policy terms, it’s a market-expansion move: less punishing geography, more predictable access, more demand.

GAIL's Response: Fighting for Its Model

GAIL’s stance has been consistent: it doesn’t accept the premise that unbundling is necessary. The company argues its integrated model is more efficient, and that building a market in a still-developing gas economy requires coordination between supply, marketing, and pipeline capacity. In its words: “Unbundling is not related to the unification of tariff. Unification of tariff is a separate exercise and should be implemented on a standalone basis.”

But tariffs themselves are where the battle gets real, because that’s where regulation touches cash flow.

When PNGRB approved an increase in pipeline tariff to ₹65.69 from ₹58.60/MMBtu, GAIL’s share price slipped—less because tariffs went up, and more because the hike was still below what GAIL had sought (₹78/MMBtu). The message was clear: even when the regulator moves in GAIL’s direction, it does so on its own terms.

The strain has been building for years. Tariffs for this regulated segment hadn’t been revised since 2018, even as GAIL expanded its grid and continued spending heavily on new pipelines. That creates a familiar infrastructure dilemma: capital goes out the door today, but the regulated return doesn’t always keep pace.

Under the latest order, PNGRB approved a levelized tariff of ₹65.69/MMBtu effective 01.01.2026—about a 12% increase versus ₹58.61—and GAIL estimated the impact at roughly ₹1,200 crore. It’s relief, but not a blank check, and it reinforces the underlying reality: in a regulated monopoly, the regulator is effectively your most important customer.

For investors, this chapter cuts both ways. Unbundling—if it ever happened—would be a structural earthquake for GAIL’s business model. Yet successive governments have hesitated to actually split the company, aware of both the execution risk and GAIL’s central role in energy security. The more plausible path is what we’ve seen so far: gradual regulatory tightening that keeps the integrated structure intact, while pushing harder on third-party access, transparency, and how much GAIL is allowed to earn on the pipes that underpin the entire system.

VI. The Diversified Empire Today: A Deep Dive into the Business Model

The Pipeline Network: India's Gas Highways

Zoom out from the regulatory tug-of-war, and you see what GAIL really is: a national machine built out of steel, contracts, and hard-to-replicate permissions.

At the center is the pipeline grid. GAIL owns and operates about 16,421 kilometres of natural gas pipelines spread across the country—decades of capex, engineering know-how, and, just as importantly, irreplaceable rights-of-way. This isn’t a business where a competitor can show up with a better app. If you control the route, you control the flow.

That’s why GAIL still commands roughly 65% of India’s natural gas transmission market. It’s the compounding effect of being early in a natural-monopoly industry: once the first backbone exists, everything else tends to connect into it.

The flagship remains the Hazira–Vijaipur–Jagdishpur (HVJ) pipeline—about 2,300 kilometres long, with capacity of 33.4 million cubic metres per day at standard conditions. HVJ started as the project GAIL was born to build. Today it’s just the best-known segment inside a much larger network.

GAIL’s major pipeline systems include the Integrated Hazira–Vijaipur–Jagdishpur Pipeline; the Dahej–Vijaipur–Dadri–Bawana–Nangal Pipeline Network; the Jagdishpur–Haldia–Bokaro–Dhamra (JHBDPL) and Barauni–Guwahati pipelines (together associated with the Pradhan Mantri Urja Ganga project); the Dabhol–Bengaluru Pipeline Network (DBPL); and the Kochi–Koottanad–Bengaluru–Mangaluru Pipeline Network (KKBMPL).

And the build-out is still in motion. The Pradhan Mantri Urja Ganga effort is essentially GAIL pushing the grid deeper into eastern and northeastern India—regions that historically sat off the map of gas infrastructure. GAIL has also said its Mumbai–Nagpur–Jharsuguda Pipeline (MNJPL) is in the final stages of execution and is expected to be fully commissioned by December 31, 2025.

LNG Portfolio: Global Reach

If pipelines are the domestic moat, LNG is the global lever.

GAIL has built a large LNG portfolio—around 16.55 MMTPA sourced from the U.S., Qatar, Australia, and more—turning it into one of the more active LNG players from India on the international stage. Separately, GAIL has contracted to buy 15.5 million tonnes per year of LNG, including supplies from Australia, Qatar, and the United States, as well as traders like Vitol and Adnoc.

To control more of the chain, GAIL has also expanded its shipping capacity with five LNG vessels: GAIL Bhuwan, GAIL Sagar, GAIL Urja, Mediterranean Spirit and Grace Emilia. Owning ships adds flexibility—especially when global shipping tightens and freight becomes its own kind of commodity.

A lot of the portfolio and trading work sits with GGSPL, which manages and optimizes LNG across the full value chain—liquefaction capacity, shipping, regasification capacity, and downstream pipelines—and also undertakes independent trading. GGSPL has MSPAs with more than 65 counterparties, spanning producers, consumers, traders, and portfolio players. Over time, it has executed trading and delivery of around 225 LNG cargoes across spot, strip, and mid-term transactions.

Petrochemicals: The Vertical Integration Play

Then there’s the part of GAIL that surprises people: polymers.

GAIL was an early pioneer in using natural gas as a feedstock for petrochemicals. At its Pata complex, it has total polymer capacity of 810 KTA. Its subsidiary, Brahmaputra Cracker & Polymer Limited (BCPL), adds another 280 KTA. Together, they hold about 15% market share in India’s petrochemical sales.

GAIL has also increased the nameplate capacity of HDPE and LLDPE to 410,000 MTPA by adding a dedicated downstream HDPE polymerisation unit of 100,000 MTPA. In BCPL—based in Dibrugarh, Assam—GAIL holds 70% equity, with nameplate capacity of 220 KTA of HDPE & LLDPE and 60 KTA of PP.

And it’s not stopping. GAIL is planning a major new ethane cracker in Madhya Pradesh, which would almost double the scale of its existing Pata petrochemical facility near Kanpur. Engineers India Ltd is preparing the detailed feasibility report, and the project is expected to be operational in the next 5–6 years.

Strategically, petrochemicals do two things. They offer a margin profile that can be more attractive than regulated transmission. But they also introduce cycle risk: polymer spreads move with global energy and industrial demand. GAIL’s expansion plans are a clear signal that it still likes the long-term upside enough to live with that volatility.

City Gas Distribution: The Last Mile

If petrochemicals take gas “up” into manufacturing inputs, city gas takes it “down” into everyday life.

GAIL is a pioneer in City Gas Distribution (CGD), with group companies authorized in 72 Geographical Areas, serving more than 9.71 million PNG customers and operating roughly 3,100+ CNG stations.

In parallel, GAIL highlights its scale across the system: with 24,623 kilometres of operational natural gas pipelines, it says it holds around 70% market share in gas transmission and over 50% share in gas trading in India. It also cites a strong CGD footprint, including the highest connected PNG base of 76.6 lakh and 2,410 CNG stations.

This is the part of the business that touches consumers directly—kitchens and car fleets. Through joint ventures like Mahanagar Gas in Mumbai and Indraprastha Gas in Delhi, GAIL participates in the last-mile margin where reliability and density matter. Indraprastha Gas is the largest CGD entity in India in terms of CNG sales and the number of vehicles supplied by CNG.

And the customer mix reinforces why GAIL remains strategically important. Currently, GAIL sells around 52% of the natural gas sold in the country. Of that, roughly 21% goes to the power sector and about 43% to the fertilizer sector. That’s energy security and food security—two policy-priority sectors, but also two sectors where pricing is politically and economically sensitive.

For investors, this is the core appeal of GAIL’s empire: a diversified set of gas-adjacent businesses, anchored by transmission stability, with upside from trading, petrochemicals, and city gas—while still being exposed to the big structural arc India is on: more energy demand, more cleaner fuels, and a long transition away from coal and oil.

VII. The Energy Transition: GAIL's Net-Zero Bet (2022–Present)

Inflection Point #3: The Green Hydrogen Pivot

For a company whose identity was forged in fossil-fuel infrastructure, the energy transition isn’t a side project. It’s an existential question: what happens to a pipeline empire in a world that wants fewer hydrocarbons?

GAIL’s answer, so far, has been to lean in—not by pretending natural gas disappears overnight, but by framing it as a bridge fuel while building real capability in what comes next: green hydrogen and renewables.

The headline move is Vijaipur. GAIL’s green hydrogen plant there made it the first state-owned gas utility in India to start megawatt-scale green hydrogen production. The facility uses 10 MW of PEM (proton exchange membrane) electrolyzer units and has the capacity to produce 4.3 tonnes of hydrogen per day. It’s also symbolically perfect: Vijaipur is already a familiar name in the GAIL story—one of the company’s historic gas hubs—now becoming a launchpad for the post-gas era.

The plant was officially inaugurated on May 24, 2024, by Secretary Shri Pankaj Jain of the Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas. Framed in policy terms, it fits neatly into India’s national objectives: energy independence by 2047 and Net Zero by 2070.

Around that plant, GAIL has been building partnerships designed to pull it further into the hydrogen ecosystem. Accelera by Cummins and GAIL signed an MoU to collaborate on green hydrogen and zero-emissions technologies in India. The stated idea is to combine Accelera’s hydrogen-generation technology with GAIL’s existing strengths—its infrastructure and operational footprint—to explore hydrogen production, blending, transportation, and storage. Following the commissioning at Vijaipur, Accelera supplied a 10 MW PEM electrolyzer system for the site in December 2024.

The Net-Zero Strategy

The second big signal is not a project, but a deadline.

GAIL advanced its net zero target for Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions by five years, moving it from 2040 to 2035. The company said its Board approved the shift—an important internal commitment for a state-owned utility, where targets have to survive both operational reality and governance layers.

That timeline is also striking in context. India’s national Net Zero goal is 2070. GAIL is now targeting net zero for its Scope 1 and 2 emissions by 2035, while aiming for a 35% reduction in Scope 3 emissions.

To get there, GAIL has laid out a mix of levers: electrification of natural gas-based equipment, renewable power, battery energy storage systems (BESS), compressed biogas (CBG), green hydrogen, CO2 valorization initiatives, and afforestation.

It has also pointed to disciplined capital allocation toward cleaner businesses—green hydrogen (including the 10 MW Vijaipur plant), renewable energy (targeting 3.5 GW by 2035), and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF). On hydrogen specifically, GAIL is targeting 310 MW of electrolyzer capacity to produce 45 KTA of green hydrogen by 2030.

Beyond Pipelines: The New Business Lines

This transition isn’t only hydrogen. It’s a wider attempt to make GAIL’s “molecule business” less carbon-intensive and more diversified.

Today, GAIL has 145 MW of installed alternative energy capacity—118 MW in wind and 27 MW in solar. It has also stated a near-term goal of installing 1 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2025, tied to India’s NDC commitments and its own carbon-neutrality push.

On the fuels side, GAIL has been expanding into ethanol and biogas. It is setting up a 500 KLPD grain-based ethanol plant in Rajasthan. For CBG, it has outlined plans that include a 5 TPD CBG plant in Ranchi, an agreement to establish 10 CBG plants with TruAlt Bioenergy Limited, and an overall plan of 26 CBG plants by 2030.

The CBG strategy is particularly elegant because it’s not a reinvention that requires abandoning the old network. If you can create gas from organic waste and feed it into the same pipelines, you get to decarbonize the molecule while still using the moat.

All of this ladders back to the bigger bet: that GAIL’s pipelines don’t become stranded assets in a hydrogen economy. They become adaptable infrastructure. If hydrogen can be blended with natural gas—and eventually transported at higher concentrations through repurposed networks—then the same grid that once made GAIL indispensable to fossil-energy growth could also make it indispensable to clean-energy distribution.

For investors, the transition creates a very familiar two-sided outcome. The risk is straightforward: if natural gas demand peaks earlier than expected, the core asset base faces pressure. The opportunity is that GAIL is trying to be early to the next grid—hydrogen, biogas, and renewables—while bringing the advantages that newcomers don’t have: an operating network, deep customer relationships, and decades of experience running national-scale energy infrastructure.

VIII. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

The PSU Paradox

GAIL is a useful reminder that “government-owned” doesn’t automatically mean “doomed.” The familiar critique of PSUs—slow, bureaucratic, and value-destroying—doesn’t fully explain a company that built the country’s gas backbone, expanded into adjacent businesses, and still manages to throw off real scale and profits.

A big milestone came on 1 February 2013, when the Indian government conferred Maharatna status on GAIL, alongside 14 other PSUs. In the PSU hierarchy, this was the culmination of a long climb—ordinary PSU to Navratna to Maharatna—each step signaling sustained performance and, crucially, greater autonomy to act.

So why has GAIL worked, despite the constraints of government ownership?

First, the core business is a natural monopoly, and public ownership fits that reality better than people like to admit. Pipelines demand enormous upfront capital, take years to build, last for decades, and exist to serve national priorities as much as shareholder returns. Patient capital and long time horizons—two things governments can provide—match the asset.

Second, GAIL didn’t stop at regulated pipes. It deliberately built profit pools that behave more like competitive businesses: LNG sourcing and trading, petrochemicals, and city gas distribution. Those arenas punish complacency and reward execution, and they forced GAIL to develop commercial muscle beyond “run the network.”

Third, at key moments, GAIL has shown it can think like a strategist, not just an operator fulfilling a mandate. The early city gas joint ventures, the Henry Hub–linked U.S. LNG contracts, and now the push into green hydrogen all point to a management culture that has repeatedly tried to stay ahead of the next demand curve.

Infrastructure as Destiny

The single most important decision in this entire story might still be the first one: build HVJ. That 1980s bet created a moat that’s hard to attack even four decades later, because in infrastructure, being first is often being permanent.

Since its inception in 1984, GAIL has remained the leader in the marketing, transmission, and distribution of natural gas in India—and it has been instrumental in building the market itself. That’s not just corporate chest-thumping; it’s the reality of network industries. The first large grid becomes the default grid. New pipelines tend to connect into it. New customers plan around it. The system starts to compound.

In businesses like this, the “asset” isn’t only steel in the ground. It’s the ecosystem that forms around it: anchor customers, dispatch and scheduling know-how, operating reliability, contracts, relationships, and regulatory muscle memory. Once that ecosystem is in place, copying it is far harder than simply funding a competing line.

The Vertical Integration Debate

GAIL’s integrated model—pipes plus marketing plus downstream businesses—was partly born out of necessity. In the early days, there weren’t enough capable players to take on specialized roles in a nascent gas market. But over time, it also became a choice: integration let GAIL shape demand, secure supply, and keep more of the value chain under one roof.

The synergies are obvious. Transmission supports marketing. Marketing creates load for transmission. Petrochemicals extract more value from gas than selling it as a commodity. City gas distribution captures last-mile margins where density and reliability matter.

But integration also invites scrutiny. When the same company owns the grid and is also the largest shipper on that grid, regulators and competitors will always worry about conflicts of interest—even if the operator is acting in good faith. That’s why unbundling keeps returning as a policy idea. Globally, mature gas markets often end up separating pipes from trading to create a more visibly neutral playing field.

India’s situation is different, though. The country is still expanding gas access, still building new routes, and still treating energy security as a top-tier priority. Those realities are exactly what have allowed the integrated model to survive longer than international precedent might suggest. Whether it continues to survive will be one of the defining questions of GAIL’s next decade.

Long-Term Contracting in Volatile Markets

If HVJ was the foundational bet, the 20-year U.S. LNG deals were the most visible strategic swing.

When GAIL signed them in 2011–2013, they looked like a masterstroke: lock in long-term supply indexed to Henry Hub, not oil, and bring structurally cheaper gas into a growing market. Then came the uncomfortable middle years—when oil-linked LNG got cheaper and fixed liquefaction fees weighed on economics—followed by the reversal, when global energy prices surged and Henry Hub–linked supply looked smart again.

Operationally, the scale is meaningful. GAIL’s long-term U.S. arrangements total about 5.8 million tonnes per year, translating into roughly 90 LNG cargoes annually from Sabine Pass and Cove Point.

The lesson here isn’t that long-term contracts are always genius or always dangerous. It’s that they are commitments through cycles, not forecasts. They demand balance-sheet stamina and the willingness to look wrong for years without panicking. A private firm might have been forced—by lenders, markets, or shareholders—to unwind the exposure during the down cycle. GAIL’s government backing gave it the capacity to hold through volatility and keep managing the portfolio until the cycle turned.

And that may be the most “PSU paradox” lesson of all: the same ownership structure that can slow decision-making can also provide endurance—an underrated advantage when your business is literally built on 20- to 40-year time horizons.

IX. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces

1. Threat of New Entrants: LOW

In gas transmission, “new entrant” sounds plausible in policy papers and investor decks. On the ground, it’s brutal.

GAIL controls roughly 65% of India’s gas transmission market and operates a nationwide grid of about 16,421 kilometres of pipelines. That scale is the moat. To challenge it, a competitor would need staggering upfront capital, years of right-of-way negotiations across multiple states, and a long march through regulatory approvals. And even if they cleared all of that, they’d still be walking into a market where the incumbent already has the customers, the operating playbook, and decades of reliability under its belt.

Policy also tends to reinforce incumbency when the goal is “finish the national grid.” Add GAIL’s Maharatna status—easier access to financing and approval pathways—and the practical threat from fresh competition stays low.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

On domestic gas, supplier power is capped because pricing is controlled under the APM framework, with major supply coming from players like ONGC and Reliance.

On imported LNG, suppliers have far more optionality—cargoes can flow to whichever market pays best, whether that’s Asia or Europe. But GAIL doesn’t show up as a small buyer. It’s contracted for about 15.5 million tonnes a year of LNG from Australia, Qatar, the U.S., and traders like Vitol and Adnoc, which gives it real leverage in negotiations and portfolio structuring.

The Eagle Ford stake (now being divested) was an attempt to blunt supplier power through backward integration. More broadly, long-term LNG contracts do something subtle: they reduce availability risk by locking supply, but they also lock GAIL into decades of price exposure and fee structures. Supplier power doesn’t disappear; it changes shape.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

GAIL’s biggest customers are concentrated and price-sensitive. Roughly 21% of volumes go to power and about 43% to fertilizers. These buyers are large, politically important, and often operating within pricing constraints of their own—which translates into negotiating pressure back onto gas suppliers.

Power is the clearest example. Gas-based generation regularly struggles to compete with cheaper alternatives, and demand can vanish when dispatch economics turn against LNG. As GAIL itself has noted, LNG-based power often isn’t scheduled by DISCOMs because cheaper options—including renewables—are available, leading to stranded capacity across a large installed base of gas power plants.

Layer on PNGRB’s push for consumer access and transparent pricing, and the balance of power continues to tilt toward buyers over time.

4. Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH

Natural gas is constantly competing with something else.

In power generation, it competes with coal and renewables, and renewables have become increasingly cost-competitive. In transport, CNG competes with liquid fuels and faces the longer-term challenge of electric vehicles. In industry, efficiency improvements and electrification can reduce gas intensity.

The deeper issue is the energy transition itself. It’s not an overnight substitution risk, but it matters because pipelines are multi-decade assets. Over the lifespan GAIL needs for its grid to stay productive, the menu of alternatives keeps improving.

5. Competitive Rivalry: LOW

In transmission, rivalry is structurally limited. This is a natural-monopoly business, and GAIL’s dominance keeps direct competition muted.

Competition is more real in GAIL’s other profit pools—petrochemicals and LNG trading—where global players set margins and cycles are unforgiving. But GAIL does benefit from integration: the transmission backbone, customer relationships, and portfolio scale can create advantages even in competitive segments.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: GAIL’s grid is the classic scale-economies machine. Once the pipes are in the ground, the marginal cost of moving additional volumes is low, and fixed costs get spread over more throughput—an inherent advantage over smaller networks.

Network Effects: Not a consumer-tech network effect, but there are real coordination benefits. As more customers connect, routing options improve, the system becomes more flexible, and utilization becomes easier to optimize.

Counter-Positioning: GAIL’s integrated model creates an awkward choice for would-be competitors: either replicate the full stack (an enormous capital and complexity burden) or enter a single segment and compete against a player that can cross-support activities across the value chain.

Switching Costs: For industrial customers, switching isn’t as simple as signing a new contract. Gas connections, on-site equipment, process modifications, and long-term arrangements create meaningful lock-in.

Branding: Not a major edge in a B2B commodity market like gas.

Cornered Resource: Rights-of-way and operating pipeline corridors are the true cornered resource. They’re difficult to obtain, politically sensitive, and effectively impossible to replicate at speed.

Process Power: Decades of building and operating pipelines translate into accumulated process advantages: construction execution, maintenance routines, safety practices, and dispatch optimization. That operational muscle is real, and it compounds.

Key KPIs for Investors to Track

For ongoing monitoring of GAIL’s performance, three metrics deserve particular attention:

1. Gas Transmission Volume (MMSCMD): This is the clearest read on the health of the core engine: how much gas is actually flowing through GAIL’s pipes. In FY24, transmission volumes rose 12% to 120.46 MMSCMD from 107.28 MMSCMD in FY23. Rising throughput usually signals stronger utilization and demand; flat or falling volumes can indicate stress—either from supply constraints or weakening end-market economics.

2. Marketing Spread (Rs/MMSCMD): The marketing business is where GAIL’s commercial skill shows up. The spread between procurement cost and selling price—shaped by contract mix, spot markets, and timing—often drives profitability volatility. Watching the spread over time tells you whether trading is adding value or merely adding risk.

3. Regulated Tariff Trajectory: Transmission is regulated, which means earnings depend heavily on PNGRB decisions and, just as importantly, when those decisions arrive. Tracking tariff orders, methodology changes, and the cadence of reviews matters. The next tariff review is scheduled for April 1, 2028.

X. Bull Case, Bear Case, and Competitive Position

Bull Case: India's Energy Backbone

The bull case for GAIL is simple: if India wants more gas, GAIL is the company that already owns the roads the gas has to travel on.

A few structural tailwinds drive that view.

India's Gas Aspiration: The government has talked about raising natural gas’s share in India’s energy mix from roughly 6% to 15% by 2030. If that ambition even partially materializes, it doesn’t just mean more imported LNG or more domestic production—it means more pipelines, more compression, more city gas build-out, and higher utilization of the grid. That’s GAIL’s home turf.

Infrastructure Moat: GAIL’s pipeline network is one of those assets that looks ordinary until you ask what it would take to replicate it: years of approvals, right-of-way battles across states, huge capital, and long construction timelines. In a natural monopoly, being first isn’t just an advantage—it’s often the whole game.

Transition Bridge: Natural gas is still meaningfully cleaner than coal and oil, which puts GAIL in an interesting position. In a gradual decarbonization pathway, gas becomes the bridge fuel that expands before it eventually tapers. And if the transition accelerates, GAIL’s early moves into green hydrogen and renewables give it at least some option value—an attempt to evolve the grid rather than be stranded by it.

Valuation Support: The stock offers a dividend yield of 4.36%. At a share price of Rs 171.7, the P/E stands at 11.1 times trailing earnings. In other words, you’re not paying a “perfect execution” price for an asset-heavy national champion, and the dividend helps while you wait.

Earnings Momentum: Over the past five years, GAIL’s revenue has grown at a 25.0% CAGR. Net profit was Rs 124,629 m in FY25, up 25.9% from Rs 99,028 m in FY24.

Bear Case: Stranded Assets and Transition Risk

The bear case is what happens when the story turns faster than the steel can.

Energy Transition: If renewables plus storage scale faster than expected, or green hydrogen becomes economically viable sooner than expected, natural gas could lose its “bridge fuel” window. That would show up first as weaker pipeline utilization. And because pipelines are built to last for decades, a lot of remaining useful life is effectively embedded in today’s valuation.

Regulatory Uncertainty: Unbundling still hangs over the company. If marketing and transmission were structurally separated, it would change how GAIL makes money and could break some of the integrated logic that has historically helped it manage volumes, contracts, and network planning.

Government Ownership: With promoter holding at 51.9%, the government remains in control—and that creates non-market risks. Policy objectives can override commercial ones. Dividend expectations can fluctuate. Investments can be driven by national priorities rather than returns. And pricing can become a political issue.

Return on Equity Concerns: GAIL’s return on equity has been about 12.1% over the last three years. For a dominant player with regulated returns, that’s not disastrous—but it is modest, and it reflects the fundamental trade-off: capital intensity plus regulatory constraints can cap value creation even when the underlying position is strong.

LNG Contract Risk: Long-term LNG contracts are both a shield and a trap. They secure supply, but if spot prices remain below contract economics for extended periods, GAIL either absorbs losses or has to work hard to remarket higher-cost cargoes.

Competitive Position Summary

GAIL sits in a rare spot in Indian energy: dominant, but not free.

Its advantages are real—scale, network effects, operating expertise, customer relationships, and the inertia that comes with being the incumbent backbone of a national grid. But those strengths are constantly negotiated. Regulation can compress returns. Government ownership can blur priorities. And over the long arc, the question of how much gas India ultimately wants is the question that matters most.

For long-term investors, the appeal is straightforward: exposure to India’s industrialization and urbanization, anchored by a hard-to-replicate infrastructure base, at a valuation that isn’t demanding perfection. The dividend provides cash flow along the way. But the risks are also structural, not cyclical—so position sizing has to respect the fact that regulation and the transition pathway can permanently change the economics.

Material Legal and Regulatory Overhangs

There are also specific overhangs worth keeping in view.

A CGST order dated 10-Dec-2025 demands GST on corporate guarantees, with a penalty of Rs.143,08,40,592.

Separately, a Central Excise Department demand of ₹3,642 crore (including interest as of March 31, 2025) is under challenge in the Supreme Court, and the company has said it expects a favorable outcome.

These are contingent liabilities that may take time to resolve, and they sit alongside the broader regulatory drumbeat. PNGRB’s tariff framework continues to evolve, with the next major review scheduled for FY28. And the recurring gap between what GAIL asks for and what PNGRB approves is a reminder that even a monopoly doesn’t get to set its own economics.

XI. Looking Forward

As Sandeep Gupta prepared to hand over the reins in early 2026—with the Public Enterprise Selection Board (PESB) having already recommended Deepak Gupta as his successor—this moment doubled as a leadership change and a strategic handoff. What got GAIL here won’t be enough to carry it through what comes next.

Because the timing is awkward in the way that matters most. GAIL had worked through the volatility of its long-term LNG bets, pulled forward its net-zero timeline, and finally moved beyond pilot rhetoric into real green hydrogen production at Vijaipur. Now the question shifts from intent to execution: can all of that become durable, compounding value—or does it stay a collection of projects that look good in a transition narrative?

One early clue is that GAIL is already circling back to the U.S.—but in a different form. The company issued a tender to buy up to a 26% stake in a U.S. LNG project, bundled with a 15-year gas import deal. The ask: about 1 million metric tons per year of LNG, free-on-board, with supplies starting around 2029–2030.

That detail matters because it tells you how GAIL is thinking about risk. The company had signaled plans to exit its Eagle Ford shale investment—commodity exposure, drilling risk, and returns that didn’t justify the capital. Yet it still appears to want Henry Hub–linked access for the long run, just with a different kind of ownership: equity in liquefaction infrastructure paired with contracted offtake, rather than equity in the ground. Less geology, more steel-and-contracts—much closer to GAIL’s native language.

And stepping back, GAIL’s next chapter isn’t only about whether it wins as a company. If India wants a gas-based bridge to be credible—on cost, on reliability, and on emissions—someone has to make the system work end to end. Energy security, industrial competitiveness, and the practicality of cleaner fuels all run through the same bottlenecks: supply contracts, terminals, pipelines, and last-mile distribution. GAIL sits at the center of that web.

The quiet giant has already shown it can outlast skepticism. The harder test is ahead: navigating a faster, messier energy transition while defending a dominant position in a market that regulators, competitors, and climate math all want to change. Whether the next four decades look like the first will come down to how well GAIL can turn transition ambition into an operating model—and not lose the plot in the process.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music