Eximius: The "Cheque Zero" of India

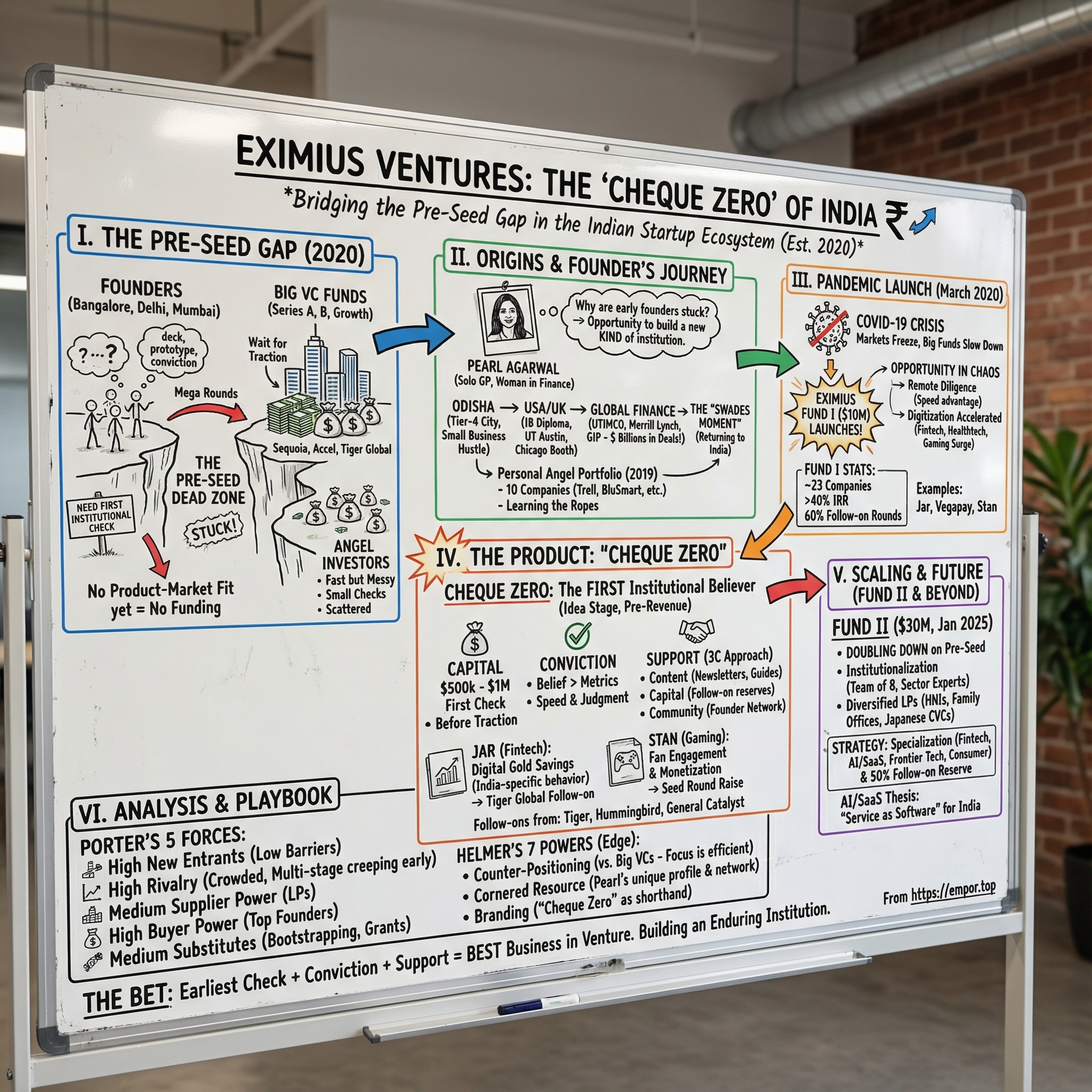

I. Introduction: The Pre-Seed Gap

Picture the Indian startup ecosystem in early 2020. The headlines were all mega-rounds: Flipkart alumni raising enormous funds, Paytm commanding jaw-dropping valuations, and late-stage capital rushing into the same familiar winners. Sequoia Capital India, Accel, Tiger Global—everyone was battling for Series A and B allocation in companies that had already found product-market fit. The playbook looked settled: wait for traction, then deploy at scale.

But under the surface was a quiet, structural problem almost nobody wanted to touch. For every celebrated unicorn, there were thousands of first-time founders in Bangalore, Delhi, and Mumbai—often in tiny co-working offices—showing up with a deck, a prototype, and a conviction that was still unproven. What they needed wasn’t a growth round. It was their first real institutional check.

And they were stuck.

Big venture funds weren’t built to move early. A $200k or $300k decision wasn’t worth the time, the meetings, or the internal process. On the other end, angel investing was fast in theory but messy in practice—small checks, scattered decision-makers, and closes that could drag on for months. So founders landed in a dead zone: too early for the giants, too ambitious to stitch together a dozen angels.

This is where Eximius Ventures enters the story. The firm didn’t just notice the gap—it built its entire model around it. And it did so through Pearl Agarwal: a solo GP, and a woman, stepping into one of the most male-dominated, relationship-driven corners of Indian finance. She launched a fund in the middle of a global pandemic and worked her way onto the cap tables of what would become breakout companies.

What makes Eximius interesting isn’t simply the list of investments. It’s that the firm itself is a business with a strategy. In venture, the product is money plus judgment plus access. The customers are founders who can choose whose money to take. The competition is relentless, switching costs are low, and reputation compounds. So the question isn’t “Can you invest?” It’s “How do you win deals you have no right to win?”

Eximius’s answer is a deceptively simple positioning statement that became its signature: “Cheque Zero.” Not just an early check—being the first institutional believer, when everyone else is still asking for more proof. That stance isn’t marketing fluff. It shapes everything: who takes the call, how quickly decisions get made, what ownership Eximius can earn, and how deeply it can embed with founders before the big names arrive.

So this isn’t a tour of a portfolio. It’s a teardown of an operating model—how Eximius sources, decides, and supports; how it competes against massive multi-stage funds creeping earlier and angel syndicates moving faster; and whether “Cheque Zero” can scale without losing the very edge that makes it work.

The timing matters. India’s startup ecosystem is hitting an inflection point: GDP per capita is rising toward $5,000, digital rails like UPI have unlocked business models that couldn’t exist elsewhere, and a new wave of operators from Flipkart, Ola, and Swiggy is becoming a new wave of founders. The bet Eximius is making is simple to say and hard to execute: that the earliest check, written with conviction, can be the best business in venture.

II. History & Origins: From Odisha to Wall Street

To understand Eximius Ventures, you have to understand Pearl Agarwal. And to understand Pearl, you have to start in Bhubaneswar, a Tier-4 city in Odisha that almost never shows up in glossy startup origin stories. This wasn’t Bangalore or Mumbai. It was provincial India in the 1990s, where “entrepreneurship” usually meant a small trading business or a neighborhood shop—and where the safe, respectable paths were engineering, medicine, or a government job.

Pearl grew up around that kind of day-to-day hustle. Her family ran a small business, and the experience stuck. By the time she was eight, she’d already decided business was the direction she wanted to take.

But the leap she wanted wasn’t just from school to a job. It was from a conservative, patriarchal environment to the US—an ambition that met plenty of resistance. She pushed anyway. That willingness to take the less-approved path, to keep going when the default answer is “no,” becomes a recurring theme in her career.

Her credentials, on paper, are the kind that normally point to a lifetime in global finance. She completed the IB Diploma Programme at Kodaikanal International School with a score of 42 out of 45 and participated in the National Honor Society. She then earned a bachelor’s degree in Economics and Corporate Finance from the Texas McCombs School of Business, where she dove into the finance track through Delta Sigma Pi and the Investment Club. Later, she got an MBA with honors from the University of Chicago Booth School of Business.

Then came the decade in the US and UK investment world. She worked at UTIMCO, the University of Texas endowment fund, as well as Merrill Lynch and Global Infrastructure Partners. This wasn’t dabbling. It was the commanding heights of capital—big institutions, big mandates, big numbers. At Merrill Lynch in Houston, she executed more than $3 billion in M&A transactions. At Global Infrastructure Partners, she worked across a $70 billion global portfolio and executed more than $5 billion in transactions.

Which is why her next move feels almost irrational on first read: going from helping deploy billions to starting a $10 million micro-VC fund.

So why take that trade?

Because she started noticing something odd about India’s startup boom. Capital was flowing—everyone could see that. But it was flowing to the same place: companies that already had traction. Meanwhile, at the very beginning of the journey, founders were still stuck. As she put it, even with money pouring into startups, there was still a real need for funding at the super-early, pre-seed stage.

This was her “Swades moment”—the idea of returning home, not just for nostalgia, but to build something that mattered. She saw founders burning time chasing angel investors, coordinating small checks, and dealing with paperwork—time that could have gone into product and execution. And structurally, the market was offering founders two bad options: angel networks that were fragmented and slow, or large institutional VCs that simply weren’t built to care about a $200k opportunity.

Before she formalized any of it, she pressure-tested the idea in 2019 by angel investing. She built a personal portfolio of 10 companies across edtech, fintech, and gaming. The list included Trell, Exprs, Ewar, BluSmart Mobility, GroMo, Redwing Labs, Nexweave, Lattu Kids, InFeedo, and InFeedo. These weren’t random darts. They were deliberate reps—learning how Indian founders raised, where the friction was, and what kind of investor they actually needed early on.

The conclusion she reached was simple, and it came with a glaring contrast. In the US, micro-VC had already matured—there was a 230% increase in the number of micro-VC funds closed in 2017 compared to 2009. In India, the category was still early. The opportunity wasn’t just to start another fund. It was to build a new kind of first-check institution: the speed and accessibility of angels, with the structure, reserves, and support of a real venture firm.

That insight became the foundation for Eximius Ventures.

III. Founding in the Fire: The 2020 Pandemic Launch

There’s a particular kind of audacity required to launch a venture fund in March 2020.

COVID was spreading fast. Countries were shutting down. Markets were whipsawing. And in venture capital, the default playbook in moments like that is simple: slow down, protect the portfolio, and wait.

For first-time founders, that caution showed up immediately. Larger funds moved “up the stack,” leaning toward later-stage bets that felt safer. Pre-seed only got harder. If you were a founder with little more than a prototype and a narrative, you weren’t just early—you were radioactive.

Pearl Agarwal went the other way.

She founded Eximius Ventures right as the world locked up, targeting a $10 million debut fund. By global standards it was small, but for a first-time, solo GP in India—raising into a full-blown crisis—it was a real hill to climb. Fundraising for Fund I was grueling. LPs were freezing capital, delaying decisions, pulling back commitments, and generally behaving exactly how you’d expect rational institutions to behave in a moment of maximum uncertainty.

So the pitch couldn’t just be “here’s my thesis.” It had to be, “I believe this is precisely the moment to start.”

And here’s the twist: the pandemic didn’t just create fear. It also created motion. India’s entrepreneurial engine didn’t stop—it rerouted. New problems appeared overnight, and ambitious founders started building around them. Eximius was built to meet those founders in the dead zone—pre-seed—when conviction matters more than traction.

The pandemic also handed a structural advantage to a nimble micro-VC. Remote diligence leveled the playing field. Big funds with layers of committees and process struggled to translate their machinery into an all-Zoom world. A lean operation like Eximius could take a founder call, build conviction quickly, and move in days instead of weeks. In a market where speed suddenly mattered more than pedigree, bureaucracy became a handicap.

At the same time, the pandemic accelerated digitization across India. People began ordering groceries online, consulting doctors over video, managing money through apps, and spending more time in digital entertainment. The sectors Eximius had already been leaning toward—fintech, healthtech, gaming, and media—didn’t just hold up. They pulled forward years of adoption.

Healthtech, in particular, saw a surge as startups tackled gaps in access, diagnostics, delivery, and preventive care through digital-first models. The broader point wasn’t just that the sector got hot—it was that the crisis made the opportunity obvious.

From the start, Eximius planned to deploy Fund I across roughly 25 to 30 startups over three years, spanning categories like edtech, fintech, gaming, healthtech, B2B SaaS, and online media. But the key wasn’t breadth—it was intent. Eximius positioned itself as thesis-driven, aiming to build conviction in a handful of areas rather than “spray and pray” across anything that moved.

The firm rolled out its $10 million first fund in 2021 and invested in 23 companies. About 60% of those companies went on to raise multiple up-rounds from prominent global investors, with the fund delivering an IRR greater than 40%. Jar, Vegapay, and Stan were among the companies backed out of Fund I.

Those metrics matter because pre-seed is supposed to be chaotic. A high follow-on rate in this part of the market isn’t normal. It’s a signal that Eximius wasn’t just getting into rounds—it was picking companies that later investors wanted badly.

Since inception, Eximius became a trusted partner for pre-seed entrepreneurs, investing in 24 companies across fintech, SaaS, healthtech, and consumer tech. Around half of those companies raised follow-on funding, reinforcing the firm’s role as a first institutional check that helped founders get to the next one.

In hindsight, the timing that looked reckless at launch turned out to be strategic. While others hesitated, Eximius moved. And by moving when the market was frozen, it earned its way onto cap tables that would have been far more competitive in normal conditions.

The crisis created the opportunity—and the need—for exactly what Eximius was selling: fast conviction, real support, and a first believer when belief was the scarcest commodity in the ecosystem.

IV. "Cheque Zero": Defining the Product

In venture capital, the “product” is strangely hard to pin down. A fund doesn’t ship software or sell a physical thing. It offers a bundle: capital, yes—but also judgment, speed, credibility, and the kind of behind-the-scenes help that can change a company’s trajectory. Every investor has money. The real differentiation is what shows up with it.

Eximius distilled its entire identity into a phrase that became its calling card: “Cheque Zero.” As Pearl put it, Eximius backs founders at the idea stage—sometimes even before incorporation—when few others will.

That sounds like branding. But it’s actually a business model.

Most venture firms are built to write fewer, larger checks into companies that already show product-market fit. Concentration is efficient: fewer boards, fewer fires to put out, higher ownership in the winners that matter, and an easier time deploying large pools of capital. The trade-off is that this machine leaves a gap right where founders are most fragile—when they need a relatively small amount of money, quickly, plus real hands-on support.

Eximius lives in that gap. It typically invests $500,000 to $1 million in a startup’s first institutional round, often before traction—or even before a product is fully built. At pre-seed, belief matters more than metrics, and speed can matter more than pedigree.

The portfolio is where this becomes real. Jar is one of Eximius’s signature early bets. The Bengaluru-based fintech went on to raise more than $58 million, and after launch it scaled quickly, reaching more than 9 million registered users and processing roughly 220,000 transactions a day.

Jar’s momentum showed up in its later rounds too. In its Series B, the company raised $22.6 million led by Tiger Global at a $300 million valuation, with existing investors—including Eximius—participating. It was the kind of outcome that defines why “Cheque Zero” matters: a company that moved from idea to a major valuation in about 18 months.

The underlying bet was deeply India-specific. Jar reduced the friction of saving by anchoring on an asset Indians already trust: gold. As Eximius framed it, Indians have long preferred to store savings in gold—an instinct backed by an enormous private stash of the metal. Jar turned that cultural behavior into a modern, app-native habit. This is the Eximius style at its best: finding a wedge that only works because of India’s unique consumer psychology and financial infrastructure.

Gaming shows a different side of the thesis. STAN emerged as a gamified fan engagement platform riding India’s growing gaming wave. It partnered with influential creators and built mechanics that let them monetize their followers through games and real-world rewards. In early 2022, still very young, Stan raised $2.5 million in its seed round—an early marker that the market was forming around the same conviction Eximius had been building.

At a product level, STAN positioned itself as a hub for gamers, creators, and fans: playing games, collecting cards of pro players, and trading through auctions and a marketplace. The bet wasn’t just “gaming is big.” It was that India’s creator economy would need new engagement and monetization primitives—and that a company built early, with the right community DNA, could own them.

Healthtech is the third pillar where “Cheque Zero” shows up clearly. Eka. Care sits at the intersection of consumer software and national digital infrastructure. Founded in December 2020 by Vikalp Sahni and Deepak Tuli—previously co-founders of Goibibo—Eka Care lets consumers manage digital health records, with doctors accessing them through an in-house clinic management tool. Sahni’s view was straightforward: a future where health data remains largely non-digital doesn’t make sense.

Eka Care claimed it became the largest repository of health records in India, with more than 30 million health records and 1.6 million ABHAs. It also added practical features like Gmail integration so medical records could be stored straight from email—small touches that matter when you’re trying to change behavior.

The company went on to raise $19.5 million, including funding from Hummingbird Ventures and PeerCapital—another example of Eximius entering early, then watching top-tier capital validate the bet later.

But “Cheque Zero” isn’t only about writing an early check. It’s also about what happens after. Eximius positions itself as a working partner in the messy middle between idea and momentum. When STAN needed to pivot and expand its market, Eximius worked closely with the founders on the model and strategy. Vegapay, similarly, benefited from support on fundraising and hiring—two of the highest-leverage problems a young company faces.

To systematize that support, Eximius built what it calls a 3C approach: Content, Capital, and Community. It publishes bi-weekly newsletters and funding updates to share market context and the VC perspective, and it has rolled out a pre-seed guide aimed at helping founders navigate the earliest, most chaotic phase.

This is also where the management company’s operating model comes into view. Eximius isn’t trying to “win” by doing what big funds do, just smaller. It’s trying to win by getting founders through the first 500 days—the period when most startups die—not just with capital, but with the kind of practical execution help that keeps momentum alive.

And the follow-on list is part of the story. Companies like Jar, Eka.care, Stan, and Skydo went on to attract investors like Tiger Global, Hummingbird, General Catalyst, and Elevation. That quality of follow-on capital is its own form of proof: if the best firms are consistently showing up after your first check, it’s a signal that you’re seeing something early—and that founders trust you enough to bring you in before the rest of the market catches up.

V. The Second Inflection Point: Fund II & Institutionalization

Going from Fund I to Fund II is never just a bigger number. It’s the moment an emerging manager either turns into a repeatable franchise—or gets exposed. The question is brutally simple: can you scale the machine without breaking the thing that made it work? Can you add process and people without losing the speed, conviction, and founder-first feel that “Cheque Zero” depends on?

In January 2025, Eximius Ventures announced its second fund, targeting $30 million—roughly triple Fund I. Big enough to matter, but not so large that it forces a total strategy reset. The plan was to back 25 to 30 companies across fintech, AI/SaaS, frontier tech, and consumer tech. The initial cheque size stayed consistent at around $500,000, and Eximius earmarked half the fund for follow-on rounds—because at pre-seed, getting in early is only half the battle. Staying in as the company breaks out is what turns good picks into fund-defining outcomes.

Fund II also signaled something else: a more deliberate, diversified LP base. Capital would come from a mix of high net-worth individuals, founder-investors, family offices, and global Japanese corporate venture companies. The Japanese CVC angle stood out—not as a vanity logo, but as a hint that Eximius was building a network of strategic relationships that could offer more than money: operating context, distribution pathways, and potential support in later rounds.

The messaging was clear, and it wasn’t shy. Eximius framed Fund II as a doubling down, not a pivot:

"At a time when funding is becoming increasingly selective, Eximius is doubling down on pre-seed startups, with an aim to drive momentum in India's innovation ecosystem. We reject the 'spray and pray' mentality, especially at the earliest stages, and instead focus on backing bold, thesis-driven ideas with contrarian viewpoints."

That stance mattered because the market had changed. After the 2021–2022 boom gave way to the 2023–2024 funding winter, plenty of investors moved “safer,” gravitating to later-stage rounds where metrics feel more concrete. Eximius chose the opposite bet: that pre-seed, in a tight market, offers better pricing, less noise, and a clearer shot at earning meaningful ownership in the right companies.

To make that bet scalable, Eximius leaned into institutionalization—starting with the team. Led by Pearl Agarwal and Preeti Sampat, and drawing on more than 25 years of global investment experience between them, Eximius built out an eight-person team with defined sector ownership. The investment committee also included sector experts with more than 40 years of operating and financial experience.

That structure is a direct response to one of micro-VC’s hardest problems: you can’t be “high conviction” in everything. The solution Eximius is reaching for is specialization—fewer generalists making broad calls, and more vertical depth that can actually help founders once the cheque clears, without slowing decision-making to a crawl.

The follow-on reserve policy is another tell. Setting aside half the fund for follow-ons is a choice, not a default. Small funds often suffer a familiar tragedy: they spot the winner early, then get diluted away when larger investors show up. By keeping meaningful dry powder, Eximius gave itself the ability to maintain ownership through multiple rounds and press its advantage when a company starts to separate from the pack.

By the time of the announcement, Fund II had already invested in four companies across consumer tech and AI/SaaS. Those deals were either led or co-led by Eximius alongside other well-known institutional investors—an early indicator that the firm wasn’t just participating, but aiming to help shape rounds.

The increased emphasis on AI/SaaS also marked an evolution in the thesis. Eximius pointed to a shift from traditional SaaS toward what it described as “service as software,” where AI automates human-heavy workflows—particularly relevant in a service-led economy like India’s. The implication is that as foundation models become more accessible, the durable opportunity moves up the stack into application-layer businesses designed around India’s unique operating realities.

And all of this was built on the credibility earned in Fund I. Around 60% of the first fund’s portfolio raised multiple up-rounds from major global investors, and the fund reported an IRR above 40%. For pre-seed—where outcomes are supposed to take longer, and the early years are often a slog—that kind of momentum suggested Eximius wasn’t just catching a temporary market wave.

Fund II, in other words, wasn’t just “more Eximius.” It was Eximius trying to become more selective, more durable, and more repeatable. As Agarwal put it: "We will be looking at companies led by seasoned operators and entrepreneurs, solving with a first-principles mindset and exceptional execution capacity in large markets." That’s a subtle but real shift—from proving the model to sharpening it.

VI. Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces for Venture Capital

To see where Eximius really sits in the Indian venture ecosystem, it helps to step back and treat venture capital like any other industry. Michael Porter’s 5 Forces framework is useful here, because it makes the invisible parts of the business visible: where the power sits, where the pressure comes from, and what actually counts as a defensible edge.

1. Threat of New Entrants (HIGH)

Venture has unusually low barriers to entry. If you have money, a point of view, and a network, you can start writing checks. That reality has pulled in a flood of new players: AngelList syndicates widening access to deals, operator-angels deploying their own wealth, family offices investing directly, and corporate venture arms showing up with strategic budgets.

For Eximius, the defense isn’t a regulatory barrier or a proprietary dataset. It’s reputation and access. In a world where top founders pick their investors, being early in companies that later attract follow-on capital from firms like Tiger Global and Hummingbird becomes its own kind of moat. It signals judgment—and it gets the next founder to take the meeting.

2. Rivalry Among Competitors (HIGH)

Early-stage India is crowded, and it’s getting more competitive by the quarter. Firms like Ankur Capital (founded in 2013 in Mumbai) back mission-driven tech and, as of June 2025, have invested in 36 companies. Kae Capital focuses heavily on pre-seed and pre-Series A and has reported 14 exits across 82 investments. Blume Ventures, founded in 2010 in Bengaluru, is another established early-stage player, known for seed and pre-Series A checks and targeting meaningful multiples.

But the sharpest edge of competition may be coming from above. Multi-stage giants have been moving earlier through structured programs and scout-style models designed to spot companies before they’re obvious. That means Eximius isn’t just competing with other micro-VCs for “Cheque Zero” deals—it’s increasingly competing with firms that can dangle something smaller funds often can’t: a clearer path to much larger follow-on capital.

3. Bargaining Power of Suppliers (MEDIUM)

In venture capital, the “suppliers” are LPs—the limited partners who provide the money. Their leverage swings with the market. In a funding winter, LPs can push terms, avoid emerging managers, and concentrate commitments with established brands. In a bull market, the best-performing GPs get to choose their LPs instead.

For a firm like Eximius, this relationship matters more than it does for incumbents, because emerging managers don’t have decades of realized returns to lean on. Eximius’s approach has been to build a diversified LP base, including high net-worth individuals, founder-investors, family offices, and global Japanese corporate venture companies—spreading dependence while bringing in relationships that can be valuable beyond capital.

4. Bargaining Power of Buyers (HIGH)

The “buyers” in venture are founders. They’re the ones selling equity, and at the top of the market, they have real power. Founders with strong pedigrees—think IIT/IIM backgrounds and operating experience at companies like Flipkart or Ola—can run tight processes, dictate terms, and judge investors not just on check size, but on brand signal and actual usefulness after the wire hits.

That’s why differentiation becomes existential at pre-seed. Eximius leans hard into being the kind of partner founders can rely on day-to-day. As one founder put it: "From timely feedback on growth ideas to help in hiring tech talent, Eximius has been a great partner throughout. You can bank on them for any help you need in your startup journey." In a market this competitive, endorsements like that aren’t just nice quotes—they’re deal flow.

5. Threat of Substitutes (MEDIUM)

Even if you want to start a company, VC isn’t the only way to fund it. Founders can bootstrap, use revenue-based financing, go through accelerators like Y Combinator, or tap into government support. India’s Start-up India Seed Fund Scheme (SISFS), for example, offers financial aid of up to INR2 million to early-stage startups for concept development.

Eximius’s answer to these substitutes is the combined package: more capital than most angel networks can reliably assemble, more speed and accessibility than large VCs typically offer, and ongoing support aimed at getting a company from idea to the next institutional round.

VII. Analysis: Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework gives us a sharper way to talk about advantage—less about vibes, more about why a firm can keep winning even as the market catches up. For Eximius, three of the seven powers matter most.

Counter-Positioning

This is Eximius’s cleanest edge. Counter-positioning happens when a challenger adopts a model that incumbents can’t copy without breaking their own economics.

Against Big VCs: Eximius made its bet explicit, even as the market tightened:

"At a time when funding is becoming increasingly selective, Eximius is doubling down on pre-seed startups, with an aim to drive momentum in India's innovation ecosystem. We reject the 'spray and pray' mentality, especially at the earliest stages, and instead focus on backing bold, thesis-driven ideas with contrarian viewpoints."

That’s easy to say. It’s hard for large funds to do. Firms like Sequoia/Peak XV or Accel manage vehicles measured in the hundreds of millions. Writing $200,000 to $500,000 checks at the very beginning is simply an inefficient use of time for their fund sizes, and their investment committee processes are built for larger decisions. Go too early, and they also risk clogging their own pipeline—backing companies that may never fit their later-stage bar.

Eximius, by design, doesn’t have that conflict. “Cheque Zero” isn’t a side quest. It’s the whole game.

Against Angels: Angels can absolutely move fast and get in early. But they often can’t offer what matters after that first burst of capital: reserves for follow-ons, structured operational support, and the signaling power that comes with an institutional firm. When Eximius leads, it’s not just money. It’s a credible marker to the next set of investors that this company has cleared a more rigorous bar than a scattered syndicate.

Cornered Resource

Micro-VC is unusually people-driven. The GP is the product, the network, and the decision engine. Eximius is led by Agarwal and Preeti Sampat, who bring more than 25 years of combined global investment experience.

But the harder-to-copy asset is Pearl Agarwal herself: the mix of Wall Street and Global Infrastructure Partners experience, a network that spans the US-India corridor, early reps as an angel in companies like BluSmart and GroMo before Eximius existed, and a founder-first reputation that compounds.

Her motivation is personal, too. She grew up in a micro-business family, watched firsthand how entrepreneurs operate with relentless zeal, and developed a genuine pull toward helping founders and the broader ecosystem. That’s what brought her back to India after a decade investing in the US.

It’s a rare combination: institutional polish plus small-town operator empathy. Competitors can copy check sizes. They can’t copy that history.

Branding

Eximius has a simple, memorable promise:

"We like to say we write 'Cheque Zero' backing founders at the idea stage, sometimes even before incorporation when few others will. A Pre Seed VC firm is a venture capital fund that invests in startups at the very beginning of their journey, often before they have a product, traction, or even incorporation."

In a market where founders have dozens of options and very little time, that kind of shorthand matters. “Cheque Zero” isn’t just a tagline—it names the exact moment founders feel most stuck. And when a firm becomes mentally associated with solving a specific, painful problem, brand turns into deal flow.

VIII. The Playbook: Lessons for Investors and Operators

The Eximius story isn’t just interesting because of what they invested in. It’s useful because it leaves behind a playbook—one that applies whether you’re an investor trying to build an early-stage platform, or an operator thinking about how the best early backers actually create leverage.

The "Micro-VC" Blueprint: Specialization Over Generalization

The default temptation for a new fund is to be everything to everyone: stage agnostic, sector agnostic, always “open to great founders.” Eximius is a case study in the opposite. It picked a narrow battlefield—pre-seed—and then went deep in a few lanes where it could build real conviction: fintech, healthtech, gaming, and SaaS.

Eximius Ventures is a dedicated pre-seed fund offering smart capital with deep knowledge. We are a sector-differentiated fund, taking a thesis-driven approach to invest across FinTech, SaaS, HealthTech, and Online Media and gaming.

That kind of focus compounds. If you’re a fintech founder, you want an investor who already understands the regulatory quirks, the distribution hacks, and the second-order effects of UPI. If you’re a gaming founder, you want someone who has already done the work on creator dynamics, monetization loops, and what “community” actually means in India. Specialization turns into faster decisions, better help, and eventually a reputation that brings the best teams to you.

The India Alpha: Digital Public Infrastructure

A core Eximius insight is that India has built a set of digital rails that change what startups can be. UPI, especially, didn’t just make payments easier—it made entirely new business models possible by enabling tiny transactions at near-zero friction.

Jar is a clean example of that India-specific edge. It reduced the pain of saving by anchoring itself to an asset class Indians already trust: gold. Indians, who have a private stash worth $1.5 trillion of the precious metal, have a fascination with gold. For generations, Indians across the socio-economic spectrum have preferred to stash their savings in the form of gold. Such is the demand for gold in India—Indians stockpile more gold than citizens in any other country—that the South Asian nation is also one of the world's largest importers of this precious metal.

But the cultural insight is only half the story. Jar’s mechanics depend on the fact that UPI makes frequent, small-value contributions viable. That’s “India alpha”—the kind of advantage you only see if you understand both the infrastructure and the behavior it unlocks.

Contrarian Betting

Eximius has been explicit about how it thinks:

"We reject the 'spray and pray' mentality, especially at the earliest stages, and instead focus on backing bold, thesis-driven ideas with contrarian viewpoints."

That posture shows up in the willingness to back sectors before they were consensus in India—like gaming when it still looked niche, or fintech infrastructure when the obvious consumer plays felt crowded. And it requires emotional discipline, because the market will try to pull you into whatever is hottest that quarter.

"Being able to control your emotions and not let FOMO drive you is a moat. Consensus is not always right in this market and hot deals are not always the highest return generating ones."

Agility as a Moat

At pre-seed, speed isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the product. When founders are trying to seize a narrow window—hire the first engineers, close the first pilots, ship the first version—the investor who can build conviction and move in days has an edge over the investor who needs weeks of meetings.

Eximius benefited from that structural advantage early on: small team, tight mandate, clear decision-maker. The catch is that this moat is fragile. As a fund grows, process creeps in. The real test is whether you can institutionalize without becoming slow—because in early-stage investing, speed is still the only free lunch.

IX. The Bull and Bear Case for Eximius Capital

The Bull Case

The bull case for Eximius is straightforward: if India keeps compounding, “Cheque Zero” becomes an even better business. But it really rests on three specific pillars.

1. India’s GDP per capita trajectory: India is nearing $3,000 GDP per capita and trending toward $5,000. Historically, that band tends to be where consumer behavior shifts—from “need to have” to “nice to have,” and from offline defaults to digital habits. If that consumption unlock plays out, many of the categories Eximius backs—fintech, consumer tech, and new software models—sit right in the slipstream.

2. Becoming the “index” for early-stage India: Pre-seed is reputation-driven. If Eximius can scale Fund II without diluting the thesis-driven discipline that made Fund I work, it has a credible shot at becoming the default first institutional name for a certain kind of founder. And that positioning can compound: great founders want the investor that other great founders picked, which pulls the next wave of founders in, which reinforces the brand, which improves access, which improves outcomes.

3. Fund II vintage and AI timing: Eximius kept its initial cheque size around $500K, and with Fund II it planned to back 25 to 30 companies across fintech, AI/SaaS, frontier tech, and consumer tech. The timing matters. A 2024/25 deployment window could be an unusually good vintage to invest in the AI application layer—after the 2021 froth, and while the “real” business models are still being formed.

The Bear Case

The bear case isn’t that pre-seed is a bad idea. It’s that this exact model can be fragile.

1. Key person risk: Eximius is still tightly associated with Pearl Agarwal. Even with an expanded team of eight and clearer sector ownership, the firm’s network, deal access, and brand are closely tied to the founder. Any prolonged absence would introduce real uncertainty for founders and LPs alike.

2. The “middle squeeze”: Eximius can get squeezed from both sides. From above, large multi-stage funds like Peak XV and Accel are increasingly moving earlier through scout programs and seed vehicles, competing for the same high-potential founders. From below, angel syndicates and platforms like LetsVenture keep making it easier to raise early money quickly, which can fragment deal flow and compress the perceived value of a first institutional check.

3. Liquidity event timelines: Indian public markets have been maturing, but that hasn’t necessarily meant faster exits. VC-backed companies are increasingly prioritizing fundamentals before attempting an IPO, and that often means taking longer to get IPO-ready—sometimes requiring structured liquidity programs along the way. Historically, Indian startups have also taken longer to reach liquidity events than US peers. For a pre-seed fund, that can mean a longer J-curve, with capital tied up for 10+ years, testing LP patience and making performance harder to judge early.

Key Metrics to Monitor

For anyone tracking Eximius going forward, three signals matter more than headline fund size.

-

Follow-on rate: What percentage of the portfolio raises institutional follow-on rounds? Eximius has said around half of its portfolio companies have raised follow-on funding. At pre-seed, this is the simplest test of whether “Cheque Zero” is consistently getting companies to the next rung.

-

Markup multiple and IRR: Eximius has reported that about 60% of portfolio companies raised multiple up-rounds from prominent global investors, with the fund delivering an IRR above 40%. These are still young, largely unrealized returns—but they’re a meaningful indicator of entry discipline and selection quality.

-

Graduation to top-tier investors: How often do Eximius-backed companies attract tier-one global investors—firms like Tiger Global, Hummingbird, and General Catalyst—in subsequent rounds? This is a quality filter, not just a survival metric, and it’s one of the clearest validations that Eximius is seeing the right companies early.

X. Conclusion

The Eximius Ventures story is, in many ways, a snapshot of India’s startup ecosystem growing up in real time. Not long ago, the idea of a solo, first-time, female GP in India raising a micro-VC fund and deliberately living in the pre-seed trenches would’ve sounded almost unrealistic. The rails weren’t as mature, the pool of repeat founders was smaller, and the path to exits felt hazier.

Now Eximius has built a meaningful early portfolio. Depending on the snapshot in time, the firm has been reported as having made 29 investments and as having invested in 32 companies, including Eka Care and Inc42. More important than the exact count is what those early checks enabled: several of these companies went on to bring in sophisticated global investors and scale into real businesses, validating the core bet behind “Cheque Zero.”

That points to the ambition. Eximius doesn’t want to be remembered as a fund that happened to get into a few great rounds early. The long-term vision is bigger: to help shape what pre-seed investing can look like in India—capital paired with context, speed paired with judgment, and a community that makes founders stronger beyond any single deal. Over the next five to ten years, the goal is to be known not just for investments, but for an ecosystem where the earliest-stage founder can reliably find the right first institutional partner.

The open question is whether Eximius can pull off the hard part: scaling without losing its edge. Can it grow from a $10 million debut fund to a $30 million vehicle and still move with the speed and clarity that made Fund I work? Can it become a durable franchise that isn’t overly dependent on one person? And can its portfolio navigate the longer, more uneven timelines to liquidity that have historically defined Indian venture outcomes?

Pearl Agarwal’s personal arc mirrors that tension between improbable beginnings and institutional ambition. Born and raised in a small town in Odisha, she grew up around the practical grit of a family small business. The path from there to global finance, and then back to India to write first checks alongside names like Tiger Global on later cap tables, isn’t just a career story. It’s a sign of a market maturing—where new kinds of investors can emerge with both Wall Street training and deep empathy for what Indian founders actually face.

Venture capital, at its core, is conviction under uncertainty—betting on people and ideas before the evidence is in. That’s exactly where Eximius chooses to play: the moment when belief matters more than metrics, and the right first partner can change the slope of a company’s entire trajectory.

In that sense, Eximius is also a startup. It spotted an underserved market, built a differentiated product, raised capital, and now has to scale while protecting the very qualities that made it worth trusting in the first place. The next decade will determine whether “Cheque Zero” remains a catchy description of how Eximius began—or becomes what the firm set out to build: an enduring institution in Indian venture capital.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Share on Reddit

Share on Reddit

Amazon Music

Amazon Music