Siemens Energy India: The Grid, The Split, and The Trillion-Dollar Transition

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

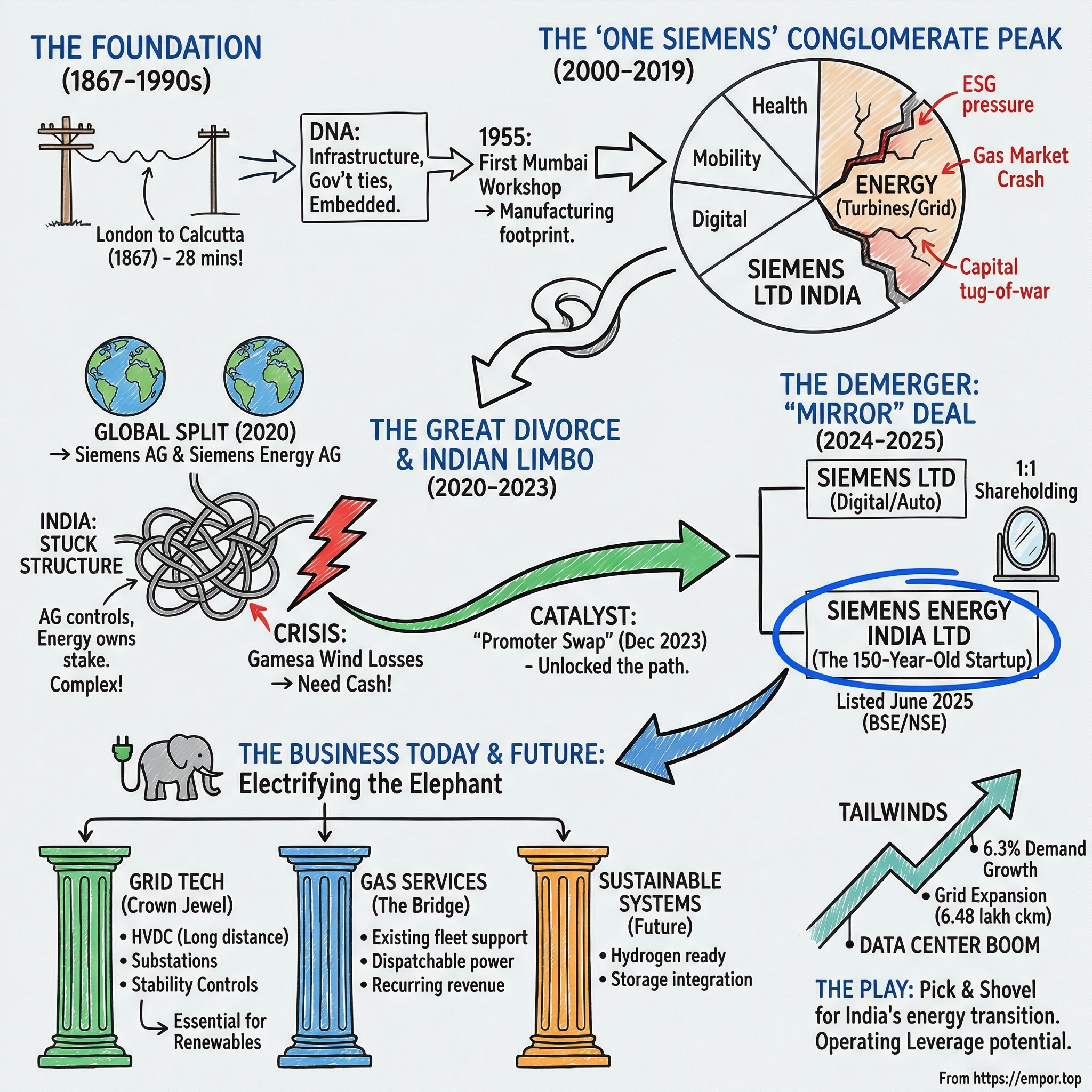

Picture this: every time someone in Chennai flips a light switch, a factory line in Gujarat hums to life, or an EV plugs in to charge in Bangalore, there’s a real chance the electricity making that moment happen is being routed, controlled, or transmitted by Siemens technology. Not the broad Siemens conglomerate—but Siemens Energy India, a newly independent company that, as of June 2025, was standing on its own for the first time after more than a century and a half of being intertwined with India’s infrastructure.

In June 2025, Siemens Energy India Limited listed on both the BSE and the NSE, completing the demerger of Siemens Limited’s energy business. Overnight, what used to be “a division inside Siemens India” became a dedicated, publicly traded pure play with a simple mandate: cover almost the entire energy value chain—from power and heat generation, to transmission, to storage.

And that’s where the paradox begins.

Siemens Energy India is both ancient and newborn. The lineage runs all the way back to Werner von Siemens and the telegraph cables of 1867. But the company itself only became a separate legal entity in 2024. It’s a global brand with Indian muscle—building and assembling heavy equipment locally, while drawing on decades of technology development from overseas labs. Most importantly, it wasn’t born from some founder’s inspiration. It was born from a corporate divorce: a multi-year untangling that required complex financial restructuring and the unwinding of ownership layers that, at times, resembled Russian nesting dolls.

The stakes for India are enormous. Electricity demand is expected to grow strongly—forecast at about 6.3% annually on average from 2025 to 2027. The Ministry of Power has targeted a major expansion of the transmission network to 648,000 circuit kilometers by 2032, up from 485,000 in 2024, to help meet peak demand projected at 458 GW by 2032. Someone has to build the substations, transformers, and HVDC links that carry power across long distances. Someone has to deliver the control systems that keep the grid stable when renewables dip—when the sun goes down and the wind stops.

That “someone,” increasingly, is Siemens Energy India.

The market greeted the listing with immediate enthusiasm. Siemens Energy India listed on June 19, 2025, hit a 10% upper circuit, and traded at roughly 114x estimated FY25 earnings. Whether you think that multiple is justified or stretched, the message was clear: investors weren’t just pricing a spin-off. They were pricing a front-row seat to India’s electrification buildout.

Here’s how this story unfolds. We’ll start at the beginning—with a telegraph line from London to Calcutta that could transmit a message in 28 minutes in 1870, changing what “connected” meant for the world. Then we’ll move into the “One Siemens” era, when the integrated conglomerate model made perfect sense—until the energy transition and ESG pressure turned “dirty” assets into valuation anchors. From there, we’ll walk through the global breakup: the 2020 spin-off of Siemens Energy AG, the crisis at Siemens Gamesa’s wind business, and the “promoter swap” that finally cleared the path for India’s demerger. Then we’ll get into the mechanics of the split and what Siemens Energy India actually does day to day—gas turbine services, grid technologies, and sustainable energy systems—before closing with the competitive landscape, the key things to watch, and the bull and bear cases for this 150-year-old startup.

II. History: The Telegraph to the Turbine (1867 – 2000)

The year is 1867. The American Civil War has just ended. Queen Victoria rules an empire that spans continents. And in Berlin, a former Prussian artillery officer named Werner von Siemens is doing something that, in hindsight, looks like the first move in a 150-year-long play to become inseparable from modern infrastructure.

Ernst Werner Siemens was an engineer, inventor, and industrialist—the kind of mind that didn’t just build products, but built categories. His name would end up as the SI unit of electrical conductance. He founded Siemens, and across his career he worked on breakthroughs that helped electrify cities: electric trams, locomotives, elevators, and more.

But the story in India begins with communication, not electricity.

Two decades earlier, Siemens had co-founded Telegraphen-Bauanstalt von Siemens & Halske with master mechanic Johann Georg Halske. One of the key early inventions was a telegraph that used a needle to point to letters—no Morse code required. With that device as the wedge, Siemens & Halske was founded on October 1, 1847, and opened its first workshop days later.

By 1867, Siemens had landed an audacious contract: build a telegraph line stretching roughly 11,000 kilometers from London to Calcutta. Siemens Brothers completed it in 1870. This wasn’t just a long cable. It was an early infrastructure version of the internet: a physical network that collapsed distance and changed what “connected” meant.

When a message from London first reached Calcutta in only 28 minutes, it caused a sensation. Before that, communication traveled by ship—measured in weeks, sometimes months. Siemens had shrunk an empire.

That 1867-to-1870 arc is the true beginning of Siemens’ presence in India. The company didn’t arrive by opening a storefront or hiring a sales team. It arrived by wiring the subcontinent into the modern world. Formal incorporation in India would come much later, in 1922—but the relationship started with the kind of project governments remember.

And the DNA was set early: take on massive capital projects, build deep relationships with public institutions, and sell reliability over price. Siemens wasn’t trying to win hearts in the consumer market. It was trying to become the default choice for infrastructure that had to work, year after year, under real-world conditions.

When Siemens’ India unit was incorporated in 1922, the country was in motion. The independence movement was accelerating, while the British Raj still directed industrial policy. Siemens positioned itself as a technology partner for electrification projects across the subcontinent, bringing German engineering into a system where government would remain the dominant buyer.

The real expansion came after independence. With policies that encouraged industrial development, Siemens set up its first manufacturing operation in Mumbai in 1955. It started small—two dozen workers in a cramped workshop under the Mahalaxmi bridge. A year later, it had a proper factory nearby in Worli, producing switchboards using imported components and basic machines: a drill, a power saw, the essentials.

That damp little workshop under the bridge mattered. It was the seed of something much larger: manufacturing capability, local execution, and a growing footprint in the systems that keep a country running. From switchboards, Siemens expanded into medical equipment, railway signaling, and ultimately the full spectrum of power generation and transmission equipment.

In 1966, Siemens opened a factory at Kalwa in Thane to make motors. Over the following decades, the map filled in. By the 1990s, Siemens had manufacturing facilities across Maharashtra, producing everything from low-voltage switchgear to massive power transformers.

Then came 1991—and with it, liberalization. India opened up. Competition flooded in. European engineering giants like ABB and Schneider arrived with global scale and aggressive pricing. Siemens suddenly had to fight for its position, not just inherit it.

And it stumbled.

In 1996/97—its diamond jubilee year in India—Siemens posted a loss of Rs 84.5 crore. Seven of its eight divisions were in the red. Management later summed it up plainly: “We were going overboard on growth and were not able to manage costs.”

The recovery was harsh, but it worked. Siemens cut employee strength from 8,500 to 4,000, and the turnaround came in 18 months. The crisis produced a leaner Siemens India—one that could compete not only with the multinationals now crowding the market, but also with domestic incumbents like Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited (BHEL).

For investors, and for anyone trying to understand Siemens Energy India today, this early history isn’t trivia. Siemens didn’t show up in India as a startup hunting for a market. It embedded itself over decades—through infrastructure projects, manufacturing, and hard-earned credibility with government buyers. Relationships with state electricity boards, installed equipment that stays in place for generations, and a reputation built in the procurement offices that matter—those are assets that don’t appear on a balance sheet.

They are the foundation of the moat Siemens Energy India inherited when it became a standalone company.

III. The Conglomerate Discount & The "One Siemens" Peak (2000 – 2019)

For roughly two decades around the turn of the millennium, Siemens’ bet was simple: integration wins.

If you were building a factory, a city, or a metro system in India, Siemens Ltd could show up as the one-stop shop. They could sell you the power equipment, the trains, the factory automation, and the systems that made the whole thing run. One relationship. One brand. Many contracts.

On paper, the “Integrated Technology” model was elegant. Cross-selling created real pull-through. A customer who trusted Siemens for rail signaling might also buy switchgear, drives, and automation. And the Siemens name—synonymous with German engineering—helped justify premium pricing across categories.

By the mid-2010s, Siemens India had become a full-spectrum industrial conglomerate, and it mattered inside the global group. In FY24, Siemens India generated about ₹20,500 crore in revenue, making it the fifth-largest revenue contributor to Siemens AG—around 4% of group topline—and among the fastest-growing.

Its biggest segment was Smart Infrastructure, contributing about 32% of revenue, spanning energy efficiency, smart meters, and grid-related solutions. The Energy segment was close behind at roughly 30%, supplying transmission and power-related systems for customers across industries including oil and gas, railways, and construction.

But even at the peak of “One Siemens,” the foundation was starting to crack. Not because the strategy was wrong for the time—but because the world around it was changing faster than any conglomerate could pivot.

The first crack was the global shift against fossil fuels. Siemens’ energy portfolio, in India and globally, was still anchored in the workhorses of the 20th century: gas and coal turbines. As ESG investing went mainstream, those assets didn’t just become controversial—they became a valuation problem. It wasn’t that the energy business couldn’t make money. It was that its very presence began to weigh on the multiple of everything else sitting in the same listed entity.

This is the conglomerate discount in its most painful form. Markets happily pay up for software and high-margin automation. They pay much less for businesses tied to carbon-intensive generation equipment. Blend them together, and investors often refuse to give the “clean” side full credit, because the “dirty” side is attached.

By the late 2010s, that discount had become especially acute in anything energy-adjacent. Climate-conscious investors were divesting. Index providers were tightening screens. And “integrated industrial” started to look less like a virtue and more like an unforced error.

The second crack was even more brutal: the collapse of the global market for large gas turbines. The energy transition didn’t arrive as a smooth glide path. Cheap renewables—especially solar in sun-rich regions—hit faster than expected and crushed demand for new thermal plants. Global orders for large turbines dropped sharply, leaving manufacturers like GE, Mitsubishi, and Siemens staring at overcapacity.

This wasn’t a normal cycle. It was a structural shift. The world was building solar and wind, not ordering fleets of new combined-cycle gas plants. Siemens’ energy portfolio had been built for the 1990s, and suddenly the 1990s were over.

Inside Siemens AG, the response was Vision 2020+, a strategy that included spinning off its Gas & Power business into a new company: Siemens Energy. The logic was straightforward—give the energy division independence to pursue its own strategy, and let the rest of Siemens be valued like the “new” industrial-tech company it wanted to become.

The third crack was capital allocation. Digital businesses—automation, building software, industrial platforms—were growing and needed sustained investment. The energy business needed capital too, but for different reasons: restructuring, technology development, and capacity rationalization. Trying to fund both under one roof meant constant trade-offs and internal tension.

Joe Kaeser, Siemens’ CEO since 2013, could see where this was heading. He’d already begun dismantling the old European conglomerate model—most notably with the Siemens Healthineers IPO in 2018. That playbook was hard to ignore: focus can unlock value.

By 2019, the plan was set. Siemens would spin off Gas and Power and combine it with its majority stake in Siemens Gamesa Renewable Energy to form Siemens Energy AG—a pure-play energy technology company. ESG-focused investors could stay with “New Siemens” (Digital Industries, Smart Infrastructure, Mobility) while choosing, separately, whether they wanted exposure to turbines, grids, and the messy reality of the transition.

What Kaeser and his team didn’t fully anticipate—what almost nobody anticipated—was how complicated this clean global break would become in India.

IV. The Great Global Divorce (2020 – 2023)

On July 9, 2020, Siemens AG shareholders logged into an extraordinary general meeting—virtual, because the world was locked down. On the agenda was one of Joe Kaeser’s last big acts as CEO: cut the energy business loose.

Kaeser’s pitch was simple. A focused Siemens could trade like a focused company. Spinning off energy, he argued, was the cleanest way to refocus the group and lift the share price.

The mechanics were almost frictionless. Siemens AG shareholders would automatically receive one share of Siemens Energy AG for every two shares of Siemens AG. Siemens AG would keep a large minority stake—roughly 35% to 45%—to support the new company at launch, with a plan to step back over time.

“This listing means that we’ve successfully reached a key milestone in Siemens’ structural realignment,” Kaeser said at the time. “With three powerful, focused and independent companies, we have an outstanding setup for the future… the separately listed companies will be in a significantly better position to tap the individual businesses’ value-creating potential than would be possible in a conglomerate.”

On September 28, 2020, Siemens Energy AG began trading on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange.

Globally, the divorce papers were signed.

Except in India.

When the global spin-off happened, Siemens and Siemens Energy did not separate their Indian businesses. It wasn’t feasible then. And that one exception created the “orphan” problem that would eat up executive time across three continents for years.

Here’s the core issue: Siemens Energy AG was now the standalone global energy company. But in India, the energy business—turbines, transformers, grid systems, services—was still sitting inside Siemens Ltd, the Indian listed entity.

And the ownership structure made it even stranger. Until March 2020, Siemens Ltd’s promoter holding was split between Siemens AG, Germany (71.70%) and Siemens Metals Technologies Vermögensverwaltungs GmbH (3.30%). After an internal realignment in June 2020 tied to the global demerger, Siemens AG held 51% of Siemens Ltd, and Siemens Energy AG held 24%.

So Siemens Energy AG owned 24% of Siemens Ltd India—but Siemens Ltd India contained the energy assets Siemens Energy was supposed to run. Meanwhile Siemens AG, which had just spun out energy globally, still controlled the Indian company that housed those energy operations.

It was a corporate governance headache. Siemens Energy had economic exposure without operational control. Siemens AG had operational control over a business it was trying to step away from. And public shareholders—about a quarter of the register—were stuck owning a hybrid, even as the rest of the world’s Siemens structure was being cleaned up.

So why not just repeat the global move in India in 2020?

Because India doesn’t do “just.” A demerger here isn’t a quick board vote and a press release. SEBI regulations, NCLT processes, tax considerations, and minority shareholder protections turn it into a long, documentation-heavy, court-supervised exercise. The global separation was already a major lift. Doing the Indian split in parallel would have been a regulatory and timing minefield.

Then came the crisis that changed the timetable.

In 2023, Siemens Energy’s wind subsidiary, Siemens Gamesa, began hemorrhaging cash. In late June, Siemens Energy scrapped its profit guidance, citing a “substantial increase in failure rates of wind turbine components” at Gamesa.

“The quality problems really result from the past, but I think we have too fast rolled out platforms into the market,” Siemens Energy CEO Christian Bruch told CNBC. Siemens Energy flagged a €2.2 billion hit, pushing its expected net loss for the year to around €4.5 billion.

Bruch said too much had been “swept under the carpet.” Gamesa CEO Jochen Eickholt spoke publicly about issues tied to rotor blades and bearings, calling it a “disappointing” and “bitter setback.”

The market’s response was brutal. Siemens Energy stock plunged by around 37% on June 23, 2023, and sentiment rippled across the wind sector as investors worried the problem wasn’t isolated.

By the end of 2023, Siemens Energy had posted net losses of roughly €4.6 billion—even as its traditional grid and power plant divisions were growing—because the wind unit’s quality problems were that severe.

And when you’re bleeding cash, you look for assets you can sell.

Sitting on Siemens Energy’s balance sheet was that 24% stake in Siemens Ltd India: valuable, liquid, and non-core to the urgent task of plugging a balance-sheet hole. So Siemens Energy monetized it.

In December 2023, Siemens Energy AG sold an 18% stake in Siemens Ltd to Siemens AG for cash consideration of about ₹19,000 crore—roughly €2.1 billion. The explicit reason: support Siemens Energy’s stability.

This was the “promoter swap,” and it was the transaction that finally unblocked everything that followed.

Siemens AG described it plainly: it planned to acquire an 18% stake in Siemens Ltd India from Siemens Energy for a purchase price of €2.1 billion in cash. That would raise Siemens AG’s stake from 51% to 69%, and reduce Siemens Energy’s stake from 24% to 6%.

The consequences landed immediately.

Siemens Energy got €2.1 billion when it needed it most. Siemens AG consolidated control of Siemens Ltd India, which meant it could push through a demerger without complex negotiations between two promoter groups. And suddenly, the stuck Indian structure had a clean path forward.

The companies framed it as the next logical step: since India hadn’t been separated during the 2020 spin-off, Siemens and Siemens Energy would propose to the Siemens Ltd India board a demerger of the energy business, with Siemens Energy ultimately acquiring a controlling stake in the demerged entity. The stated aim was to complete it in 2025—significantly earlier than previously planned.

For investors, the 2020–2023 chapter is the reminder that restructurings don’t move in straight lines. The 2020 global split was supposed to simplify the story, but in India it created years of limbo. The Siemens Gamesa crisis was disastrous for Siemens Energy shareholders—but it also forced the monetization that accelerated the Indian separation. In complex corporate structures, unintended consequences are guaranteed. Every so often, they become catalysts.

V. The Demerger: A "Mirror" Transaction (2024 - Listing)

On May 14, 2024, Siemens Limited’s Board met in Mumbai to approve what had effectively become the inevitable endgame: the energy business would be carved out into a separate legal entity, Siemens Energy India Limited, incorporated as a wholly owned subsidiary of Siemens Limited. In time, that new company would be listed—and crucially, it would mirror Siemens Limited’s shareholding.

The mechanics were almost disarmingly clean. Under the scheme of arrangement, every shareholder of Siemens Limited would receive 1 share of Siemens Energy India Limited for every 1 share of Siemens Limited. After that, Siemens Energy India would list on both BSE and NSE.

This is why it was called a “mirror” deal. The shareholder base stayed perfectly intact. If you held 100 shares of Siemens Ltd, you’d end up holding 100 shares of Siemens Ltd plus 100 shares of Siemens Energy India—no fractional entitlements, no elections, no swap math.

Sunil Mathur, Managing Director and CEO of Siemens Limited, framed it as a focus-and-funding story: “Siemens Energy India Limited and Siemens Limited will script new paths as two independent, publicly-listed companies. The underlying market drivers and capital allocation requirements are fundamentally different in the energy business compared to the industrial business. The demerger will enable both companies to pursue their specific strategies, focus on their core portfolios and take decisions on capital allocation.”

Then came the long march through the Indian regulatory stack. On December 2, 2024, Siemens Limited shareholders approved the transaction. On March 25, 2025, the NCLT sanctioned the scheme. Siemens Limited set April 7, 2025 as the record date to determine which shareholders would receive equity shares of Siemens Energy India Limited.

Finally, the finish line: on June 18, 2025, Siemens Energy India announced it had received BSE and NSE approval for listing and trading effective June 19, 2025. Siemens Energy India Limited then listed on BSE and NSE in June 2025.

So what, exactly, did ENRIN receive in the split?

It received the physical backbone of high-voltage power infrastructure: air-insulated switchgear up to 800 kV; gas-insulated switchgear up to 420 kV; bushings; instrument transformers and coils; power transformers up to 765 kV; reactors up to 765 kV; and traction transformers. It also brought with it the capability to deliver EPC and turnkey projects for high and extra-high voltage AIS and GIS substations.

But the real crown jewels were the grid technologies—especially the ability to build HVDC substations and the control systems that govern power flow at scale. This is the part of the business designed for the world India is entering: a grid that has to expand fast, carry power over long distances, and stay stable even as intermittent renewables get layered in.

On top of that, Siemens Energy India received exclusive business rights across South Asia—India, Bhutan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives—for the Siemens Energy portfolio. In other words, it didn’t just inherit assets; it inherited the right to sell, engineer, manufacture, install, commission, and service Siemens Energy’s products and solutions across the region. It also continued to export products and solutions to Siemens Energy Group customers globally through Siemens Energy’s sales channels.

The post-demerger ownership structure reflected the “unfinished business” left behind by the promoter swap. Siemens AG and its subsidiaries held 69% of Siemens Energy India Limited. Subsidiaries of Siemens Energy AG held 6%. The rest sat with public shareholders.

And the market debut was emphatic. On June 19, 2025, the newly demerged Siemens Energy India began trading on both the BSE and the NSE.

Zooming out, the demerger did what it was supposed to do: it created two independent companies—Siemens Limited, India and Siemens Energy India Limited—each able to run its own strategy and capital allocation without being dragged into the other’s story. It also delivered on the acceleration pact announced in November 2023 between Siemens AG and Siemens Energy AG to speed up the unbundling of Siemens’ Indian operations.

But the strategic rationale went beyond “unlocking value.” Siemens Energy AG stated it intended to ultimately acquire a controlling stake in Siemens Energy India Limited, subject to regulatory approvals. That implied there could be more corporate choreography ahead—potentially Siemens AG transferring its stake to Siemens Energy AG to bring India fully in line with the global energy parent.

For shareholders, though, the immediate result was simple: clarity. If you wanted exposure to digital transformation, automation, and the “new Siemens,” you could own the streamlined Siemens Ltd. If you wanted the grid buildout and the messy, hardware-heavy energy transition, you could own Siemens Energy India. Or you could hold both—keeping the same economic exposure as before, but with two clean scorecards instead of one blended conglomerate.

VI. The Business Today: Electrifying the Elephant

By 2025, India wasn’t just adding electricity. It was rewiring the country for a very different future.

As of June 2025, India’s installed power capacity had reached 476 GW—still anchored by about 240 GW of thermal, but now increasingly shaped by renewables, including roughly 110.9 GW of solar and 51.3 GW of wind. Non-fossil capacity had climbed to 235.7 GW, made up of 226.9 GW of renewables plus 8.8 GW of nuclear. In other words, India was approaching a 50/50 split on installed capacity.

That split is the headline. The grid is the plot twist.

Because building renewable generation is the easy part. The hard part is moving that power—reliably—across a continent-sized country, at the exact moment it’s needed. In 2024, stakeholders finalized the National Electricity Plan (Transmission) with a target to expand the network to 6.48 lakh circuit kilometers by 2032. And to evacuate 280 GW of variable renewables, India needs 335 GW of Inter-State Transmission System capacity by 2030.

This is the environment Siemens Energy India was born into. And the company’s business today stacks neatly into three pillars.

Pillar One: Grid Technologies—The Crown Jewel

If you want to understand Siemens Energy India, start here. This is where it differentiates, where it wins sticky projects, and where it becomes almost impossible to displace.

The portfolio spans the heavy hardware—power transformers, AIS and GIS substations, HVDC systems—plus the automation and control layers that make the whole thing behave. On top of that comes the services engine: long-term maintenance, upgrades, and modernization that turn one-time projects into relationships that can last decades.

And HVDC is the best lens for why this matters. India’s HVDC transmission systems market was expected to reach USD 3.86 billion in 2025 and grow at an 8.65% CAGR to USD 5.84 billion by 2030.

HVDC matters because India’s best renewable resources are often nowhere near its biggest load centers. Solar in Rajasthan needs to reach factories and cities across the west and south. Wind in Gujarat needs to flow to demand in other regions. Over long distances, traditional AC transmission loses more power and offers less control. HVDC reduces those losses and gives grid operators far tighter command over power flow—exactly what you need when the supply itself is variable.

One example: the ±800 kilovolt, 6 GW bi-pole and bi-directional HVDC terminals that form part of India’s renewable evacuation and interstate transmission system. These terminals will help move power from the renewable energy zone in Bhadla, connecting large-scale clean generation to the national grid and making that renewable buildout actually usable.

Competition here is real—Siemens Energy, ABB, BHEL, Hitachi Energy, and Power Grid all matter. But the key investor takeaway is simpler than market share charts: grid technology isn’t commodity equipment.

A transformer in a substation can run for 30 to 40 years. The controls, monitoring, and software create deep operational integration. Once a utility commits to a vendor’s platform, switching isn’t just expensive—it’s risky. You don’t rip out the nervous system of the grid to save a few basis points.

Pillar Two: Gas Services—The Bridge Fuel

The energy transition in India is not a straight line from coal to solar. Intermittency is the permanent constraint: when the sun sets or the wind slows, the grid still has to deliver. That means dispatchable power—capacity that can ramp up quickly—still matters. Gas-fired plants play that role.

In the large steam and gas turbine domain, Siemens Energy India provides services and solutions for gas turbines, large steam turbines, large generators, and associated control technology. Its customers include power utilities, independent power producers, EPC firms, and industrial clients. The offering is broad: maintenance, operations support, digital services, modernization and upgradation, plant flexibilization, and control and digitalization solutions.

And conventional power remains a large part of the system. In FY2024, thermal capacity represented about 53.5% of total installed capacity.

The business profile here is mature, but valuable: the installed base drives recurring revenue through long-term service contracts, spare parts, and upgrades. As renewables rise, the role of thermal plants changes. Instead of steady baseload, they need to cycle—up and down more frequently—which creates demand for upgrades and controls optimization. In a grid getting more volatile, reliability becomes a product, and service becomes the annuity.

Pillar Three: Sustainable Energy Systems—The Future Bet

This is the option embedded in the story: the portfolio aimed at helping customers decarbonize beyond just adding renewables.

Siemens Energy India’s sustainable energy portfolio includes hydrogen-ready hybrid plants, energy storage integration, and industrial decarbonization solutions. These are earlier-stage compared to grid and services, but strategically important. If grid technologies are the “must have” and gas services are the “keep the lights on,” sustainable energy systems are the “what comes next.”

The India Premium

One reason the stock drew so much excitement at listing is that the Indian growth setup is fundamentally different from the global parent’s end markets.

India’s electricity demand was forecast to grow about 6.3% annually on average from 2025 to 2027. Europe is largely flat. The U.S. is growing, but in pockets. India is building across the board—generation, transmission, and consumption—at a pace developed markets simply aren’t.

Against that backdrop, Siemens Energy sees room to push India higher in importance within the broader group, with an ambition to make it the third or fourth largest revenue contributor to Siemens AG over the next three years.

Layer on “China Plus One.” As manufacturing diversifies away from China, India is absorbing new industrial investment—and every new factory, industrial park, and logistics hub pulls demand for substations, transformers, and grid connections. Electrification isn’t a theme here; it’s an input cost for GDP growth.

The Data Center Boom

One of the biggest demand accelerants is also the least intuitive: data centers.

India’s data centre capacity was expected to expand from 1.4 gigawatts last year to 9 GW by 2030. By then, data centers could consume about 3% of India’s electricity, up from less than 1% currently. Local and global technology firms announced more than $32 billion in investments over the last two years to expand data center infrastructure in India, and over 95% of the capacity increase over the next five years was expected to come from leased facilities.

Data centers don’t just consume power—they require a different grade of it. They demand reliability with near-zero tolerance for outages. They need specialized substations, often with redundancy built in. And because they cluster in metros like Mumbai, Chennai, and Hyderabad, they create concentrated demand for grid infrastructure exactly where the network is already stressed.

To support rising requirements from consumption growth, public investment, industrial expansion, and data centers, Siemens Energy India has been expanding its transformer and switchgear manufacturing capacity and inaugurated a modern Industrial Steam Turbine Service Centre in Raipur.

Financial Performance Post-Listing

Siemens Energy India entered the public markets with visibility. As of March 2025, its total order book stood at ₹15,100 crore—more than twice the revenue it earned last year—giving a clear runway for execution.

In Q4 FY2025, the company reported a 27% rise in revenue to ₹2,646 crore and a 31% increase in profit after tax to ₹360 crore. The order backlog reached ₹16,205 crore, up 47% versus FY2024.

The other important detail is operational: current capacity utilization was under 60%. That matters because it suggests the company can grow into its fixed cost base, improving margins as volumes rise. It’s also investing ₹460 crore to double transformer-making capacity, a direct signal of management confidence in sustained demand.

This is the operating leverage story in plain terms: when you run heavy manufacturing and engineering at higher utilization, incremental revenue can translate into disproportionately higher profit. And in a grid buildout cycle, utilization is not just an internal metric—it’s a proxy for how hard the country is leaning on your factories.

VII. Analysis: Power & Forces

Porter’s framework is useful here, not because it gives you a neat score, but because it explains why this is such a brutal business to enter… and such a sticky one to win.

Porter’s Five Forces

Supplier Power: Moderate

This supply chain is full of specialized inputs: transformer cores, turbine components, control electronics, and proprietary software. Siemens Energy India depends on external suppliers for certain key materials and components, and it also relies on third-party vendors for technology and equipment—including the Siemens Energy Group itself.

That relationship is a double-edged sword. It’s a source of world-class technology access, but it also creates dependency. The mitigating factor is discipline: multi-sourcing where possible, long-term supply agreements, and procurement processes designed to avoid a single point of failure.

Buyer Power: High, but nuanced

The buyers here are not small customers. They’re NTPC, PowerGrid, and state electricity boards—large, sophisticated government-linked entities that buy through competitive tenders and negotiate hard. Price matters, timelines matter, and the contract language is unforgiving.

But this is where the nuance comes in: these customers also buy outcomes. A transformer failure doesn’t just trigger a warranty claim; it can mean outages, political heat, and cascading grid risk. That reality creates room for a reliability premium, and it’s where incumbents with a track record—like Siemens—can differentiate beyond the bid price.

Threat of Substitutes: Low for grid infrastructure

There’s no clever workaround for moving electrons at scale. You can’t transmit megawatts via satellite. The grid is physical by necessity: lines, substations, transformers, and control systems.

Technologies evolve—HVDC versus HVAC, different protection and control architectures—but the underlying requirement doesn’t. If the country electrifies, the grid has to be built.

Threat of New Entrants: Low

To build large turbines or deliver HVDC substations, you need decades of engineering know-how, deep project execution capability, heavy capital investment, and credibility with customers who are, by nature, risk-averse.

One structural barrier matters a lot: even globally, there are only a limited number of suppliers who can deliver HVDC-related equipment at the required scale and reliability. And as demand for HVDC rises worldwide—especially in developed markets pushing hard on clean energy—that capability becomes even harder to replicate quickly.

Competitive Rivalry: Intense, but structured

Competition is real and relentless. Global players like GE Vernova, Hitachi Energy, and ABB compete alongside domestic heavyweights like BHEL. In generation equipment, BHEL has historically been a dominant supplier—by 2017, equipment supplied by BHEL made up around 55% of India’s total installed power generation capacity.

Where rivalry gets “structured” is segmentation. In more commoditized categories, the fight is largely about price and delivery. In high-technology areas—advanced turbines, HVDC systems, complex grid controls—performance, efficiency, and reliability start to matter as much as the commercial bid. That’s where moats can actually form.

Hamilton’s Seven Powers

Switching Costs: High

This is the quiet superpower of the business. Once a utility installs a Siemens control system, or standardizes around Siemens equipment, it’s no longer buying a product—it’s buying an operating environment. Operator training, integration with other systems, spare-parts inventory, service tooling, maintenance routines, and long-term contracts all stack up into real lock-in.

Switching vendors isn’t just expensive. It’s operationally risky. And in grid infrastructure, “risky” is often unacceptable.

Scale Economies: Significant

Advanced turbine and grid R&D is expensive, and it only pays off when you can spread it across a global installed base. Siemens Energy India benefits from technology developed within the global Siemens Energy ecosystem, then manufactured and executed with Indian cost structures.

Domestic competitors like BHEL have major manufacturing capability, but they don’t have access to the same global R&D engine on the same terms—and in frontier categories, that gap matters.

Process Power: Present

This is the “German engineering, Indian execution” idea made real. Products are designed to global standards, but built, installed, and serviced locally—using India’s talent pool and cost advantages.

That hybrid model is harder to copy than it looks. It takes manufacturing depth, field service capability, project management muscle, and the kind of quality systems that only get built over decades.

Network Effects: Moderate

Not the Silicon Valley kind. But an installed base creates its own momentum: reference sites, operating data, institutional familiarity, and a service network that gets better as it gets larger. The more Siemens equipment runs in Indian conditions, the more the company learns—and the more confidence customers have in repeat deployments.

Counter-positioning: Limited

This isn’t a category where a startup can “move fast and break things.” The grid can’t be A/B tested. Physics is physics, and utilities don’t experiment with their core infrastructure. Disruption happens here, but it tends to come from incumbents evolving technology, not from outsiders reinventing the business model.

The Competitive Landscape

BHEL is the anchor domestic competitor, and its scale is enormous: 16 manufacturing units, two repair units, four regional offices, eight service centres, and eight overseas offices. It’s also built the capability to deliver 20,000 MW per year of power equipment.

But the rivalry isn’t symmetrical across the stack. In advanced gas turbines, BHEL relies on licensing arrangements with GE, and it has supplied about 230 GE-design gas turbines to refineries, process industries, and utilities. Aftermarket support is handled through BHEL GE Gas Turbine Services, a 50:50 joint venture between BHEL and GE.

So the market splits into two games running in parallel. In commodity equipment—standard transformers, conventional switchgear—pricing pressure is intense and execution is everything. In advanced systems—HVDC terminals, hydrogen-ready turbines, digital grid controls—Siemens Energy India is fighting primarily against other global technology leaders, where differentiation can win deals and the “cheapest” bid isn’t always the winning bid.

VIII. Playbook: Lessons for Builders & Investors

The Conglomerate Discount is Real

The Siemens split is corporate finance in the real world. When everything lives inside one giant listed entity, investors struggle to value it cleanly. High-margin, “new economy” businesses get dragged down by heavy, cyclical ones. And management ends up forced to make trade-offs that don’t make sense for either side.

The demerger solved that in one move: two businesses, two strategies, two scorecards. Siemens Ltd can be valued like an industrial-tech and automation company. Siemens Energy India can be valued like what it is: a grid-and-power infrastructure company riding India’s buildout. The broader lesson is straightforward: whenever you see a conglomerate with businesses that want different capital, different timelines, and different investors, a split can unlock clarity—and sometimes value.

Infrastructure is the Pick-and-Shovel Strategy for GDP Growth

The California Gold Rush lesson still holds: don’t bet only on which miner strikes it rich—sell the picks and shovels to everyone who’s digging.

That’s the cleanest way to understand Siemens Energy India’s role in India’s growth story. It doesn’t matter which automaker wins EV share, which hyperscaler dominates cloud, or which city becomes the next manufacturing hub. All roads lead back to the same dependency: reliable electricity. And reliable electricity, at India-scale, requires transformers, substations, grid automation, and long-distance transmission. Siemens Energy India sits right in that flow of spending.

The Transition is Non-Linear

A lot of Western energy-transition storytelling implies a neat, linear march away from fossil fuels. India doesn’t get to live in that script.

Even as renewables have surged—solar capacity has multiplied dramatically since 2014—thermal power still anchors the system. As of June 2025, thermal capacity was still around half of India’s installed base, totaling roughly 240 GW, and coal makes up the overwhelming majority of that thermal stack.

So the reality is a long, messy middle. Renewables keep growing, but the grid still needs dispatchable power when generation drops. That’s where gas plays its role as a bridge: not the end state, but the stabilizer. The companies best positioned aren’t the ones that only sell a “green” dream. They’re the ones that can do the hard work of the transition—integrating renewables while keeping the legacy fleet reliable and flexible.

Key KPIs for Monitoring

If you’re tracking Siemens Energy India, three operating signals tend to tell the story before the headlines do:

-

Order Book / Revenue Ratio: This is the visibility meter. A backlog that’s comfortably above annual revenue usually means the company has runway; a falling ratio can be an early warning. As of March 2025, Siemens Energy India was sitting at roughly 2.4x.

-

Order Inflow Growth Rate: Revenue is yesterday’s work being recognized. Order inflows are tomorrow’s work being won. Consistent growth here signals commercial momentum and, often, competitive strength.

-

EBIT Margin Trajectory: With capacity utilization still under 60%, margins should have room to expand as factories and project teams run hotter. Watching margins tells you whether operating leverage is actually showing up—or whether costs, execution, or pricing pressure are eating it away.

IX. Epilogue: The Bear Case, The Bull Case, and What Comes Next

The Bear Case

Start with the most obvious risk: execution.

Siemens Energy India lives in the world of mega-projects—multi-year timelines, unforgiving engineering, and contracts where a single delay can cascade into penalties, disputes, and margin damage. In grid and generation, you don’t get to “ship a patch” after the fact. If something goes wrong in commissioning, logistics, or quality, it shows up in cost overruns and customer friction, fast.

Then there’s the supply chain. Even now, global shocks can still hit the exact inputs that matter most: specialized components, constrained manufacturing slots, and vendors whose quality issues can become your delivery problem. And because Siemens Energy India draws on the broader Siemens Energy Group for technology and certain components, trouble elsewhere in the group can create real spillover—whether that’s operational disruption, customer hesitation, or reputational drag.

Valuation is the other elephant in the room. At roughly 114x estimated FY25 earnings, the stock is priced for a lot to go right. That doesn’t mean it can’t grow into the multiple—but it does mean the market is far less forgiving of a soft quarter, slower order intake, or margin expansion that takes longer than expected.

Finally, there’s who pays the bills. A meaningful share of demand comes from government-linked utilities, and in India that comes with payment-cycle risk. State distribution companies have a history of strained finances. The IEA noted that, as of March 2025, distribution companies in India owed more than USD 9 billion in unpaid dues, and had accumulated losses of USD 75 billion in 2023. Even if the project gets delivered perfectly, collections can still become a headache.

The Bull Case

The bull case is simpler, and it’s bigger: India isn’t choosing whether to electrify. It’s choosing how fast.

Over the next decade, the country needs to add enormous capacity to keep up with economic growth, industrial expansion, and rising per-capita consumption. The Central Electricity Authority projects India’s power requirement could reach 817 GW by 2030. In that kind of buildout, the winners aren’t just the companies that generate power—they’re the companies that make the system work: transmission, substations, transformers, grid control, and the software that keeps frequency and voltage stable.

And this is where the underinvestment story matters. Transmission and distribution is the connective tissue, and it has to be built ahead of demand, not after the blackouts start. With the government planning ₹1.5 lakh crore in T&D project awards this year, Siemens Energy India is positioned right where the spend is headed.

There’s also a mechanical advantage in the model: operating leverage. With capacity utilization still below 60%, growth doesn’t have to come with a proportional rise in fixed costs. If order conversion stays strong, the company has room to expand margins just by running its factories and project teams harder.

Then there’s the differentiation angle. As India’s grid gets more complex—more renewables, more distributed generation, more volatility—basic hardware isn’t enough. Control systems, grid automation, high-voltage technology, and long-distance transmission become higher-value decisions, not lowest-bid commodities. Siemens Energy India’s access to global R&D isn’t just a nice-to-have; it’s how you win the projects that matter most.

And one more tailwind is arriving faster than most planning models assumed: data centers and AI infrastructure. The electricity demand from digital infrastructure isn’t just large—it’s concentrated and reliability-obsessed. The expectation is that India’s data capacity will expand sharply between 2025 and 2030, rising from 1,668 MW to 8,120 MW. That kind of load growth doesn’t merely require more generation. It forces investment into the grid, the substations, the redundancy, and the equipment that keeps uptime sacred.

What Comes Next

The corporate story may not be over. Siemens Energy AG has stated it intends to ultimately acquire a controlling stake in Siemens Energy India Limited, subject to regulatory approvals. Today, Siemens AG holds 69% and Siemens Energy AG holds 6%. Fully aligning India under the global energy parent would simplify governance and could strengthen the strategic role India plays—potentially as a larger manufacturing and export hub within the Siemens Energy network.

But regardless of how the shareholding chessboard evolves, the operating reality is already here: the separation is done. The 150-year-old startup now lives on its own scorecard—raising capital on its own, allocating it on its own, and earning trust deal by deal, project by project.

The line that began as telegraph wire from London to Calcutta has become something far more consequential: the high-voltage arteries of a modern economy. Every transformation needs infrastructure. Every electron needs a path. And somewhere inside a humming substation, control systems watch the load, transformers steady the voltage, and the machinery that makes modern India possible runs—quietly, relentlessly—still carrying the name of the engineer who first set out to connect the world.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music