Clean Science & Technology: The Story of India's Catalytic Chemistry Innovator

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Somewhere in the industrial sprawl of Kurkumbh, Maharashtra, sits a chemical plant that does something, at commercial scale, nobody else in the world does: it makes anisole using vapor phase catalytic hydroxylation. The company behind it is Clean Science & Technology. And it’s the kind of business that feels invisible—until you realize it quietly controls more than half of global capacity in a molecule most people have never heard of: MEHQ, short for monomethyl ether of hydroquinone.

MEHQ sounds obscure, but it plays a very unglamorous, very essential role. It keeps acrylic acid from polymerizing uncontrollably during storage and transport. Take that stability away and you don’t get reliable acrylic acid. Without reliable acrylic acid, you don’t get superabsorbent polymers. And without superabsorbent polymers, modern diapers, industrial coatings, and a long list of everyday adhesives start to look a lot less “everyday.” This is the specialty chemicals business in a nutshell: tiny ingredients, huge consequences.

Clean Science trades on India’s National Stock Exchange under the ticker CLEAN. By early 2026, it carried a market capitalization north of ₹3,000 crore, ran with zero debt, and posted EBITDA margins that, in many years, cleared 40%—the kind of profitability people associate with software, not reactors and distillation columns.

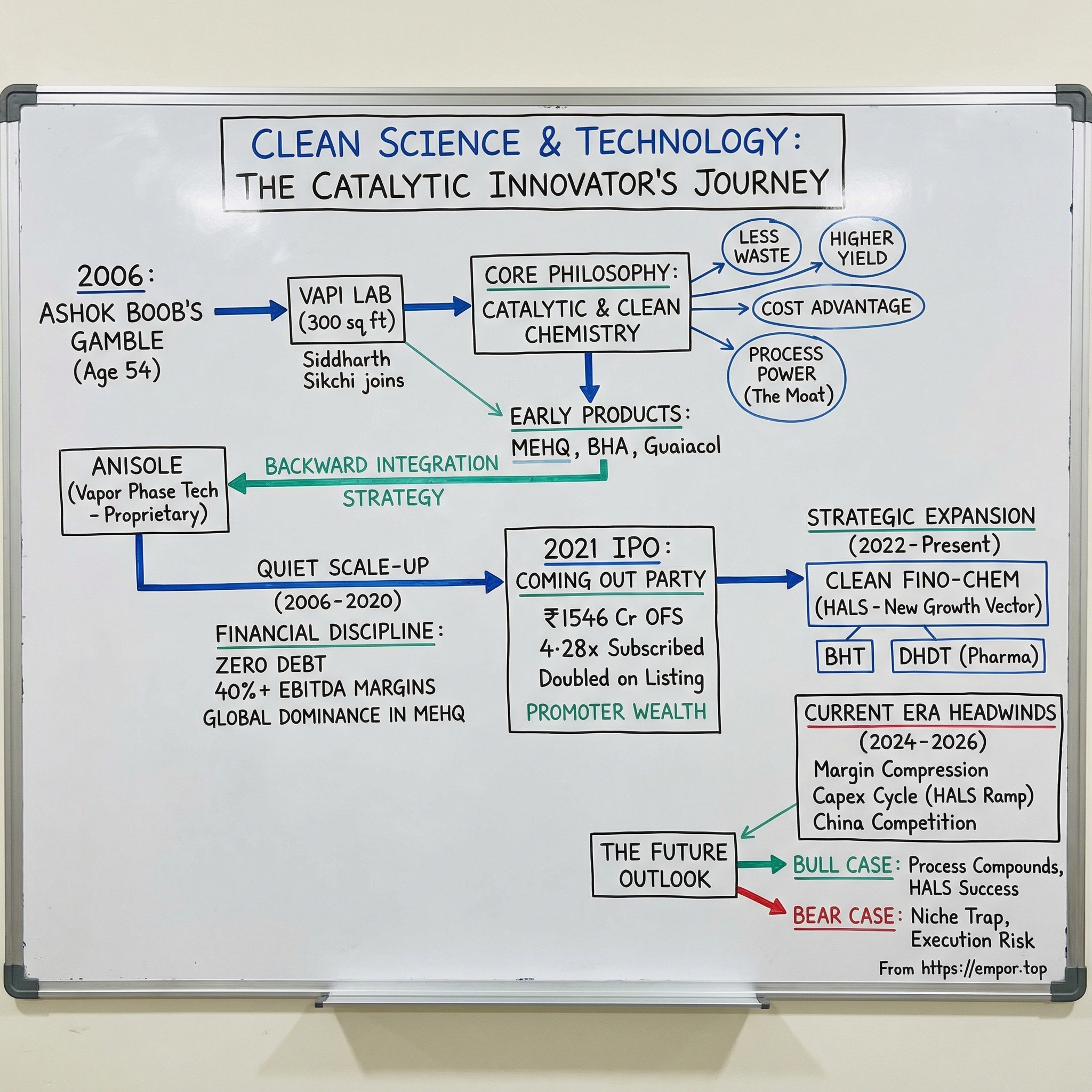

The business was incorporated in 2003, but the real story begins in 2006. That’s when Ashok Boob—a chemical engineer with a three-decade career behind him—walked away at age 54 to build something of his own. He wasn’t chasing scale for scale’s sake. He was chasing a different way of making chemicals.

So here’s the question that drives this deep dive: how did two alumni of the Institute of Chemical Technology in Mumbai—India’s most storied chemical engineering pipeline—turn a 300-square-foot lab in Vapi, Gujarat into what’s often described as India’s most profitable specialty chemicals company?

The answer is part chemistry, part culture, and part capital allocation. Clean Science built its edge around catalytic processes—cleaner, more efficient, and notoriously difficult to replicate. In an industry where traditional stoichiometric reactions can mean higher input costs and a lot of waste, “how” becomes the moat. If your process is meaningfully better, you can win on cost, quality, sustainability—or all three at once.

That bet worked. Spectacularly. But the company’s next chapter is harder: margin compression, the challenge of ramping new product lines, and the ever-present pressure of global competition.

In this story, we’ll follow the full arc—from Boob’s late-career leap, to the quiet years of building in obscurity, to the 2021 IPO that doubled on day one, and into the current era of expansion and headwinds. Along the way, we’ll translate the chemistry into plain English, pull apart the decisions that created a zero-debt, high-margin machine, and ask the big question investors care about now: is Clean Science a compounder that can keep compounding, or a niche champion approaching the limits of its niche?

II. The Founder Story: A Fifty-Four-Year-Old's Gamble

The Pre-History

For three decades, Ashok Ramnarayan Boob was a company man. He built his career at Mangalam Drugs and Organics the way a lot of Indian chemical engineers of his era did: patiently, technically, and with an almost craftsmanlike devotion to the details of organic synthesis.

He came out of the Institute of Chemical Technology in Mumbai—known back then as UDCT—arguably the country’s most influential training ground for process chemistry. ICT’s alumni network runs like a hidden spine through India’s chemicals and pharma industries, because the school doesn’t just teach reactions. It teaches scale: how to turn something that works in glassware into something that works in steel, day after day, batch after batch.

By 2006, Boob had more than experience. He had pattern recognition. He knew which chemistries behaved at industrial scale and which ones fell apart the moment you tried to push them beyond a lab. And he kept coming back to one frustration that was everywhere in specialty chemicals: most manufacturing still relied on stoichiometric processes.

Here’s the difference in plain English. In a stoichiometric reaction, the inputs get consumed in fixed proportions. You make your product—and you also make a lot of byproducts and waste that can be toxic, costly, and painful to handle. In catalytic chemistry, a catalyst helps the reaction happen without being consumed. Done right, you use less raw material, generate less waste, and get better yields.

The problem is that “done right” is the whole game. Finding a workable catalyst, then engineering a process around it that runs safely and consistently at commercial scale, is brutally hard. It’s years of R&D, trial and error, and hard-earned know-how. It’s not something you download from a paper and replicate in a weekend.

Sometime around 2006, that conviction stopped being theoretical. The specifics of Boob’s departure from Mangalam aren’t fully spelled out in public documents, but the broad contours are clear: there were disagreements about direction, and Boob increasingly believed catalytic, cleaner processes weren’t just better—they were the future. And then, at exactly the right moment, a key collaborator came back home.

Leaving a 30-year career at 54 isn’t a cute entrepreneurial plot twist. In India, that’s an age when most executives are planning stability, not uncertainty. In the chemicals industry especially, there isn’t much of a safety net, and failure doesn’t come with a comforting mythology. If this didn’t work, there likely wasn’t a neat second act. For Boob, the risk wasn’t abstract. It was personal.

The Founding Moment

That returning collaborator was Siddharth Sikchi—Boob’s nephew—who came back to India in May 2006 with a master’s degree in Organic Chemistry from the University of Manitoba in Canada.

His return wasn’t random. It fit into a larger family conversation about what could be built if Boob’s decades of industrial judgment met a younger chemist’s current academic training and ambition. Boob brought a deep feel for markets, customers, and manufacturability. Sikchi brought modern research habits, fresh technical grounding, and the energy to build from scratch. Together, they weren’t just starting a company. They were trying to institutionalize a philosophy: build specialty chemicals around catalytic and clean technologies from day one.

Clean Science & Technology had been incorporated back in 2003, but the real work began in 2006—in a three-hundred-square-foot lab in Vapi, Gujarat. Vapi was a practical choice. It sits inside one of India’s densest chemical manufacturing corridors, with access to suppliers, talent, and logistics. But the lab size matters because it tells you what this wasn’t. There was no venture backing, no grand unveiling, no safety cushion. It was family capital, family reputation, and an idea that had to work.

Their early product choices were both narrow and telling: MEHQ, BHA (Butylated Hydroxy Anisole), and Guaiacol.

All three shared the same traits. They were functionally critical—customers couldn’t just swap them out for something cheaper without risking performance or compliance. They plugged into large, global end markets like polymers, food preservation, and pharmaceuticals. And importantly, existing manufacturing routes were often waste-heavy, leaving room for a competitor with a cleaner, more efficient process to step in and win.

This was the founding insight: don’t compete by picking “big” chemicals. Compete by picking the right ones—molecules where a catalytic route could be meaningfully superior to the incumbent stoichiometric approach. If you could crack the catalyst and the process conditions, the know-how itself became defensible. The process became the moat. And because better catalysis often means less waste and lower input costs, you could get the rare double win: better economics and better environmental outcomes, pointing in the same direction.

The Family Affair

Clean Science wasn’t just a two-person story. It was a family enterprise from the start.

Ashok’s brother, Krishnakumar Ramnarayan Boob, joined as a co-promoter, adding both technical depth and financial support. And Parth Ashok Maheshwari—who later earned an MBA from Babson College in the U.S.—represented the next generation, someone positioned to translate between chemistry-driven decision-making and modern business execution.

Collectively, the promoter group brought more than six decades of experience in the chemicals industry. These weren’t professional managers parachuted in with frameworks and polished presentations. They were technocrats—people trained to think in reaction pathways, yields, impurities, and reliability. In a business where customers buy consistency and trust as much as they buy molecules, that background mattered.

That structure created real strength: ownership and management were aligned because they were the same people, and the family’s wealth rose and fell with the company. But it also planted a question that would follow Clean Science as it grew: when the company’s destiny is tightly bound to one family’s vision, the upside is focus—and the risk is concentration.

III. The Business Model: Chemistry as Code

What is Specialty Chemicals?

Before we go any further, it helps to define “specialty chemicals,” because the phrase gets used as a catch-all.

Picture the chemicals industry as a pyramid. At the bottom are commodity chemicals—huge-volume building blocks like ethylene and chlorine. One producer’s molecule is indistinguishable from another’s. The game is scale, cycles, and cost. Pricing power is thin.

At the top are specialty chemicals: smaller volumes, tighter specs, and far higher consequences if something’s off. A pharmaceutical intermediate that’s slightly under spec might be unusable. A polymerization inhibitor that’s inconsistent can turn into a production nightmare. In specialty chemicals, the “product” isn’t just the molecule. It’s the molecule plus purity, consistency, documentation, regulatory qualification, and the confidence that the next shipment will behave exactly like the last one.

That’s why switching suppliers is hard. You’re not swapping out one generic input for another. You’re asking a customer to re-qualify a critical ingredient while their own plant keeps running.

Clean Science plays in this world across three buckets: performance chemicals, pharmaceutical intermediates, and FMCG chemicals. Different end markets, same underlying requirement: these inputs are functionally critical, and customers need them on spec, on time, every time.

The Product Portfolio

Performance chemicals are the engine room—the biggest contributor and where Clean Science built its global edge.

Start with MEHQ. You can think of it as a stabilizer that keeps acrylic acid from doing what it naturally wants to do: polymerize. Acrylic acid is incredibly useful, but it’s also reactive and temperamental during storage and transport. MEHQ keeps it from “running away” and turning into a mess before it ever reaches the customer. If you make, ship, or process acrylic acid, you don’t treat MEHQ as optional. You treat it as insurance.

Clean Science doesn’t just participate here—it controls more than half of global MEHQ capacity.

Then there’s BHA, Butylated Hydroxy Anisole. It’s an antioxidant used in food, animal feed, and cosmetics to stop fats and oils from going rancid. That sounds mundane until you remember shelf life is the foundation of packaged food economics. Ascorbyl Palmitate plays a similar antioxidant role in infant food and cosmetics, and TBHQ is another stabilizer used in food oils.

On the pharma side, Clean Science makes Guaiacol, along with intermediates like 4-Cyanophenol and 4-Aminophenol. And it expanded into the antiretroviral supply chain with DHDT, a pharmaceutical intermediate commercialized in fiscal year 2025.

In FMCG chemicals, you’ll find 4-MAP, used as a UV blocker in sunscreens, and Anisole, a precursor that shows up in perfumes, pharma synthesis, and agri-chemicals. Anisole matters for a second reason too—because it’s the connective tissue in Clean Science’s strategy. We’ll come back to it.

The "Clean Chemistry" Difference

The real story isn’t the list of products. It’s how Clean Science makes them.

Clean Science’s advantage is process—manufacturing specialty chemicals using catalytic routes where many competitors rely on traditional stoichiometric methods.

A quick way to feel the difference: stoichiometric chemistry consumes reagents in fixed proportions and often generates a lot of unwanted byproducts and waste. Catalytic chemistry uses a catalyst to drive the reaction without consuming it. When it works, you get better yields, less waste, and a more efficient use of raw materials.

But the catch is brutal: getting catalysis to work reliably at industrial scale is hard. It’s not just “have a catalyst.” It’s years spent dialing in conditions, designing reactors, controlling impurities, and making the whole thing run safely day after day.

The most distinctive example is Clean Science’s vapor phase technology for anisole hydroxylation. The company has said this is a closely guarded process, and based on public information, it’s the only one to have commercialized this specific vapor phase catalytic approach. That’s a meaningful claim, because it implies a capability that isn’t easily copied by competitors who can buy your product, test it, and try to replicate it. In process businesses, the finished molecule rarely reveals the manufacturing recipe.

And once you have a better recipe, the benefits stack up fast: lower raw material consumption, lower waste handling, higher yields, and fewer environmental liabilities. Even if a competitor understands the broad chemistry, they still have to solve the invisible part—temperature, pressure, flow rates, catalyst life, impurity control, and dozens of other parameters that determine whether a process is commercially viable or just academically interesting.

That’s also why Clean Science leans heavily on trade secrets rather than patents. Patents require disclosure and they expire. Trade secrets, if protected well, can be durable. In this kind of manufacturing, the moat is often less “what molecule do you make?” and more “what does your plant know how to do?”

The Backward Integration Masterclass

Clean Science didn’t just build better processes. It used them to reshape its position in the value chain.

Most companies start with a finished product and talk about moving forward toward customers. Clean Science’s defining move was to go backward—starting with specialty chemicals like MEHQ and BHA, then investing to make a critical input itself: Anisole.

Anisole is a key feedstock across multiple products. By developing its own efficient anisole process—anchored by that vapor phase catalytic capability—Clean Science reduced dependence on suppliers for one of its most important inputs. And in the process, it became the world’s largest anisole producer, turning an input it once had to buy into something it could control and monetize.

Then it did the other half too: forward integration. With MEHQ in hand, it moved into BHA. Step by step, it assembled a tighter chain where it could capture more margin, control quality end-to-end, and reduce exposure to outside bottlenecks.

This is vertical integration with teeth. If you’re a competitor trying to challenge Clean Science in MEHQ, you either buy anisole in the open market—starting with a built-in cost disadvantage—or you build anisole capacity yourself. But to do that and win on economics, you’d need the kind of catalytic process expertise Clean Science spent years accumulating.

That’s the compounding effect of doing integration the hard way. It doesn’t just make you cheaper. It makes the path to catching you longer, riskier, and more expensive.

IV. The Scale-Up Journey (2006-2020): Building Quietly

Early Years: Proof of Concept

From 2006 up to its 2021 IPO, Clean Science spent most of its life doing the opposite of what you’d expect from a future market darling. There were no big announcements, no splashy branding, no founder-as-celebrity arc. It largely stayed out of the spotlight while it did the only thing that matters in specialty chemicals: it proved, patiently and repeatedly, that its catalytic processes didn’t just work in a lab—they worked in a plant, at scale, with the reliability global customers demand.

Because in this world, “winning a customer” isn’t a handshake and a purchase order. It’s an obstacle course.

A prospective customer has to qualify your product with months of testing. Then they have to get comfortable that your manufacturing is consistent—batch after batch, impurity profile after impurity profile. If the end use is pharmaceutical or food-related, layer on regulatory checks and documentation. The timeline can easily stretch from first conversation to real revenue over two or three years.

So those early customers weren’t just sales. They were bets—companies willing to take a chance on an unproven Indian producer because the promise of a cleaner, more efficient process was too attractive to ignore. And once Clean Science delivered, those first wins turned into the only marketing that really counts in B2B: references. One successful qualification becomes the credibility to start the next one. Slow at first, then surprisingly hard to stop.

By the time the company was approaching its IPO, it had built three manufacturing facilities in Kurkumbh, Maharashtra, with total installed capacity of forty-four thousand metric tons per annum. Kurkumbh wasn’t a romantic choice. It was a practical one: an established industrial zone in Pune district with solid infrastructure, a workable regulatory environment, and export access.

The Global Dominance Strategy

Clean Science getting to roughly half of global market share in MEHQ is a masterclass in niche dominance.

MEHQ is important, but it’s not a trillion-dollar market that attracts endless capital. It’s the kind of category where, if one company becomes the clear lowest-cost, highest-quality supplier, the economics start to bend in its favor. New entrants look at the market size, the technical difficulty, and the incumbent’s cost position—and decide it’s not worth the pain.

Clean Science built a customer base across India, China, the Americas, and Europe by doing the unsexy things exceptionally well: shipping on time, hitting spec, and being dependable when customers can’t afford surprises. Its buyers weren’t casual shoppers. They were industrial operators—plants that run continuously and treat polymerization inhibitors and antioxidants like critical infrastructure.

A production manager at an acrylic acid facility doesn’t want to “try a new supplier” the way a consumer might try a new snack brand. The input cost is small; the downside of an off-spec batch is enormous. That’s why, once a supplier is qualified and embedded into the supply chain, switching becomes a real decision with real friction: requalification work, potential regulatory re-approval, supply chain changes, and the operational risk of something going wrong. In specialty chemicals, that friction is a moat.

Financial Profile Pre-IPO

Out of those quiet years came a financial profile that looked almost implausible for manufacturing.

Clean Science ran with zero debt from the beginning and carried that discipline through the IPO and beyond. In chemicals, where capex is unavoidable and expansion comes in chunky steps, funding growth entirely through internal cash requires two things: strong profitability and an almost stubborn willingness to stay within what the business itself can support.

The result was rare. EBITDA margins were often north of forty percent. Return on equity routinely exceeded twenty-five percent. Clean Science became, by the standards of heavy industry, a cash machine—helped by efficient processes, tight execution, and the absence of interest costs.

And this wasn’t an accident of timing. It was a philosophy. No debt meant no covenants, no lenders peering over management’s shoulder, and no forced decisions when credit cycles turned. Every expansion came out of profits. Every new product effort was funded by operating cash flow. The trade-off was obvious: growth would be steadier, not explosive. But the payoff was just as obvious too: the growth that did happen was self-funded—and therefore durable.

Why the Long Quiet Period Matters

It’s tempting to treat the pre-IPO period as a warm-up act. It wasn’t. It was the entire competitive advantage being built.

The venture-backed playbook is speed: grow fast, raise money, grow faster, then go public to give investors liquidity. Clean Science did the inverse. It grew methodically, raised no external growth capital, and only went public after about fifteen years—when the founders chose to create liquidity.

That patience bought them options. Without the pressure of quarterly narratives, they could invest in R&D that wouldn’t pay off quickly. Without outside capital demanding a particular growth curve, they could prioritize process refinement, quality systems, and customer qualification—the slow work that actually builds defensibility in chemicals.

So when Clean Science finally appeared on public markets, it arrived looking “too good”: dominant niches, pristine balance sheet, proprietary processes, and a management team that had been running the same playbook long enough to know exactly what it could and couldn’t do.

There’s a bigger point here about how moats form in manufacturing. Software can build advantage fast—sometimes in a single product cycle. Process industries build advantage by accumulation. Every campaign run, every yield improved, every impurity solved, every catalyst life extended adds to an internal knowledge base that competitors can’t easily see, let alone copy. Clean Science’s quiet years weren’t dead time. They were compound interest—paid in know-how.

And for India’s specialty chemicals industry, the signal was even louder: this wasn’t a story of winning on cheap labor or loopholes. It was proof that an Indian company could reach global cost and quality leadership in specialty chemicals through technology and process innovation.

V. The 2021 IPO: Coming Out Party

The Decision to Go Public

By July 2021, Indian capital markets were on a tear. The post-COVID rally was in full swing, retail participation was surging, and specialty chemicals had become one of the market’s favorite stories—supercharged by the “China Plus One” narrative that promised global supply chains would diversify away from China and toward India.

Clean Science stepped into that moment with an IPO that, structurally, said more than any roadshow ever could.

This was a pure offer for sale. The company raised no primary capital. Instead, the roughly ₹1,546 crore that changed hands went to existing shareholders—primarily the promoter family. That’s a very specific signal. This wasn’t a business coming to market because it needed money to survive or even money to grow. It was a business that had already proven it could fund itself, and the founders were simply creating liquidity after about fifteen years of building in near-total obscurity.

The price band was set at ₹880 to ₹900 per share. The market responded with confidence: the issue was subscribed about 4.28 times. Then came listing day—when the stock opened at roughly double the issue price. A 100% premium on day one doesn’t happen because investors read the prospectus carefully. It happens because a story catches fire, and everyone wants in at once.

What the IPO Revealed

The prospectus also revealed just how tightly held Clean Science had been. Promoters owned 94.66% before the IPO—an unusually high stake for a business of this size, and a sign that this had been a family-built, self-funded machine. After the sale, promoter holding came down to 78.55%.

The payouts were significant. Ashok Boob received around ₹244 crore from his portion. Krishnakumar Boob received about ₹193 crore. Siddharth Sikchi sold roughly ₹40 crore worth, and Parth Maheshwari about ₹75 crore.

Yes, those are life-changing numbers. But the deeper reveal wasn’t what the family took out—it was what the business had quietly become. Public investors could finally see the full shape of it: years of 40%+ EBITDA margins, zero debt, global leadership in narrow but essential molecules, and process know-how built around catalytic chemistry that competitors hadn’t matched.

Siddharth Sikchi’s message to the market was almost understated: Clean Science had enough cash to fund three to four years of planned expansion without needing external capital. In a market used to equity dilution and debt-funded capex cycles, that kind of self-sufficiency read like a flex—without ever sounding like one.

Market Reception

The market didn’t just like the story. It fell for it.

Ashok Boob and Siddharth Sikchi were named finalists for EY Entrepreneur of the Year 2022. Media profiles multiplied around the simplest, most compelling arc imaginable: a man who started at 54 and became a billionaire by 70. At peak valuations, Boob’s net worth rose from roughly ₹10,000 crore to nearly ₹17,000 crore.

The stock chart looked like a victory lap. From an IPO price of ₹900, the shares eventually climbed above ₹3,000 at the high. Mutual funds rushed to build positions. Analysts initiated coverage and reached for superlatives: software-like margins in a manufacturing business, a pristine balance sheet, and a niche-dominance playbook that seemed almost unfair.

And the narrative started to reinforce itself, the way bull-market narratives always do. “Zero debt” became a mantra. “Catalytic processes” became shorthand for an unbreakable moat. “China Plus One” became the macro tailwind that could justify almost any multiple. For a stretch, Clean Science was treated as the rare Indian compounder that simply could not disappoint.

But that’s also the moment when investing gets dangerous. The question was no longer whether Clean Science was a great business—it clearly was. The question was whether the stock price was already pricing in all of that greatness… and then adding an extra layer of perfection on top.

VI. The Hidden Gem: HALS and Clean Fino-Chem (2022-Present)

The Strategic Expansion Decision

In 2022, while public markets were still enjoying Clean Science’s IPO afterglow, the company made a move that mattered far more than the day-to-day stock chart. It incorporated Clean Fino-Chem Limited, a wholly owned subsidiary, and gave it a mandate that looked like the boldest bet since the Vapi lab days: build India’s first manufacturing facility for Hindered Amine Light Stabilizers—HALS.

This wasn’t a small add-on. The company committed ₹335 crore, a big step up for a business that had historically scaled in measured increments. And, in true Clean Science fashion, it did it the hard way: funded entirely through internal accruals. No debt. No new equity. By March 2024, the plant was funded, and commercialization began.

Most importantly, this wasn’t just “more of the same.” HALS was a brand-new product category, with different end markets, different customers, and a different competitive set. It signaled that Clean Science wasn’t only defending its existing niches—it was trying to create the next one.

What is HALS and Why Does It Matter?

HALS are the chemicals that keep plastics from breaking down in sunlight. Any polymer product that lives outdoors—automotive parts, agricultural films, garden furniture, water-treatment pipes—has a simple enemy: UV radiation. Without stabilization, plastics discolor, turn brittle, and fail far sooner than they’re supposed to. HALS are the invisible shield that buys those products years of usable life.

If MEHQ is the safety catch that keeps acrylic acid from running away and polymerizing, HALS is the sunscreen for polymers. And that’s why it fits Clean Science’s instincts so well: functionally critical, low-volume, high-value, and difficult to substitute once customers qualify a grade and lock it into their formulations.

The global HALS market was about $1 billion in 2022, projected to grow to roughly $1.3 billion by 2026—steady, mid-single-digit growth. It’s also a market long dominated by giants like BASF, Clariant, Solvay, and Japan’s Adeka. And despite India being a major consumer of polymers, the country had been dependent on imports for HALS. That’s the opening Clean Science saw: a real import-substitution opportunity in a category where consistency and process know-how matter more than marketing.

The Growth Vector

The strategic importance of HALS goes beyond the revenue line it might add. It’s a test of whether Clean Science’s real advantage—catalytic process development and manufacturing discipline—travels well.

The first nine months of fiscal year 2026 saw capex of around ₹165 crore, with a large share directed toward Clean Fino-Chem’s HALS buildout. This is the uncomfortable part of the cycle: fixed costs are real, volumes are still ramping, and the P&L can look worse before it looks better. Management has framed HALS as a multi-year effort, not something you judge quarter by quarter.

If the ramp works, HALS could become “the next MEHQ”: a niche where Clean Science earns a globally competitive position in a market historically controlled by multinational incumbents. More than anything, it would validate the company’s core thesis that process power isn’t a one-product trick—it’s a repeatable engine.

BHT and DHDT: More New Products

HALS is the headline, but it isn’t the only new thread. In December 2024, Clean Science commercialized Butylated Hydroxy Toluene—BHT—an antioxidant cousin of BHA with its own end markets. And in fiscal year 2025, it entered another pharmaceutical intermediate with DHDT, used in manufacturing antiretroviral drugs for HIV treatment.

The pattern is the point. Clean Science has been expanding by stepping into adjacencies where its strengths still apply: catalytic process development, tight control over impurities, and the patience required to clear customer qualification and regulatory expectations.

That naturally changes the shape of the business. The old Clean Science was essentially a three-to-four-product company. The new Clean Science has been building toward seven or more meaningful product lines, each with its own customer base and cycle. That diversification matters because it changes the risk profile: when one product slows, the whole company doesn’t have to slow with it. The “hidden businesses within the business” start to show up.

At the same time, Clean Science hasn’t stopped feeding the core. It has been planning capacity increases of about 30–40% in existing lines like MEHQ and Guaiacol. It’s the balanced approach you’d expect from this management team: keep scaling what already works, while patiently constructing the next leg of growth.

VII. Current Era: Navigating Headwinds (2024-2026)

The Margin Compression Story

By late 2025, any conversation about Clean Science seemed to end up in the same place: margins.

In the second quarter of fiscal year 2026, EBITDA margin slid to about 35.6%, down from roughly 41.1% in the prior quarter. By the third quarter, the discomfort got louder—revenue was down around 20% year-on-year, and profit after tax fell close to 30%. The stock that had once been a must-own in smallcap portfolios was suddenly the one everyone had to explain in quarterly review meetings.

The mood changed fast. Analysts who had praised the company’s “quality premium” during the run-up were now talking about downgrades and cut price targets. In bull markets, premium valuations feel like a reward. In tougher markets, they feel like a weight. That’s just how public market psychology works.

What matters is why this happened. And the answer is less “the moat disappeared” and more “the cycle turned—right when the company started spending big.”

First, pricing across specialty chemicals softened. After the post-COVID period, when supply chains were chaotic and prices were elevated, the industry moved back toward something closer to normal. Customers stopped over-ordering, ran down inventories, and went back to hard negotiations and just-in-time buying.

Second, capacity came online faster than revenues could absorb it—especially with HALS. A new plant brings real fixed costs from day one: depreciation, overhead, people, utilities, maintenance. If utilization is still ramping, those costs don’t wait patiently for sales to catch up.

Third is the China factor—always lurking in chemicals. Chinese manufacturers have historically competed on scale and cost, helped by a system that can be more forgiving on subsidies and environmental constraints. Clean Science’s edge—process efficiency, quality consistency, and sustainability—still matters. But when a buyer is offered a lower price for a similar spec product, Clean Science has to earn the premium every time.

Volume vs. Margin Dynamics

This is the tension at the heart of Clean Science’s current chapter: volume growth versus margin preservation.

The company is in the middle of its biggest investment cycle yet—HALS, expansions in core lines like MEHQ and Guaiacol, and the early commercialization curve for products like BHT and DHDT. None of those ramp instantly. Customers need to qualify. Volumes need to build. Utilization needs to climb before returns start to look like the model investors got used to.

In this phase, the reported numbers can look worse than the underlying business. Costs show up upfront; revenues arrive gradually. That gap creates an “optics problem” for anyone living quarter to quarter. Management has talked in three-to-four-year horizons. The market, as usual, has a shorter attention span.

The Balance Sheet as Buffer

The reason this period is uncomfortable—but not existential—is the balance sheet.

Clean Science has stayed in a net cash position, with net debt-to-equity around negative 0.26. Shareholder funds were over ₹1,400 crore as of March 2025. Operating cash flow for FY25 was about ₹213 crore.

Translate that into plain language: they can take the hit. There are no debt covenants to trip, no refinancing cliffs, no lenders forcing the company to slow down at exactly the wrong time. They can keep funding the HALS ramp, keep investing in R&D, and keep pushing the product pipeline—all from internal resources.

This is what fifteen years of financial discipline buys you: the ability to keep playing offense when a weaker balance sheet would force you into defense.

The Bear Case Acknowledged

None of this makes the concerns go away. It just frames them properly.

Return on equity has come down. A three-year average around 25% has drifted toward roughly 18–19% more recently. That’s still strong in absolute terms, but direction matters. If ROE is lower because pricing power is structurally weaker, or because new capital is earning lower returns, that changes the long-term story.

Execution risk is also real. HALS is not just “another line extension.” It’s a new category with different competitors and customer expectations. BHT and DHDT are earlier-stage efforts that still need to prove themselves at scale. Clean Science’s history suggests it can execute—but a track record in one chemistry doesn’t automatically transfer to every adjacent market.

And then there’s valuation. Clean Science has often traded at a premium because the business earned it—high margins, zero debt, niche dominance. But premium multiples don’t tolerate stumbles. When expectations are set at “near perfect,” every margin miss and every delay gets punished more than it would for an average company.

That’s the trade the market is forcing today: do you judge Clean Science by the last few quarters, or by whether this investment cycle produces the next decade of compounding?

VIII. Management Deep Dive: The Current Leadership

The Promoter Dynamic

One of the biggest under-the-surface changes in Clean Science’s post-IPO life has been the steady dilution of promoter ownership. From 78.55% immediately after listing, the promoter stake has fallen to about 51% in recent filings—a drop of roughly twenty-seven percentage points over about three years.

On one level, this is normal. Newly listed promoter families often sell gradually once restrictions lift, and more free float can improve liquidity. But the pace and magnitude still matter. At 51%, the Boob family retains majority control, which keeps the classic founder-led alignment intact. At the same time, repeated selling becomes something investors naturally track—not because promoters “shouldn’t” take money off the table, but because the market will always ask what it implies about confidence in the next few years.

Key Leaders

Ashok Ramnarayan Boob, now in his early seventies, remains Chairman and the company’s north star. Between three decades at Mangalam Drugs and the years building Clean Science, he brings a level of process and industry intuition that’s hard to replicate. But the question gets more practical with time: how long will he stay deeply involved in day-to-day strategic calls, and what does leadership look like when he steps back?

That’s where Siddharth Ashok Sikchi comes in. He has become the operating leader and the public face of the company—an ICT Mumbai pedigree paired with a master’s in organic chemistry from Canada. He’s also the primary interface with analysts and investors, and his style tends to be measured and technical: less showmanship, more process-and-data.

Then there’s Parth Ashok Maheshwari, representing the next generation. With an MBA from Babson College, his profile reads like intentional preparation for leadership that goes beyond chemistry—building systems, talent, and execution. How his responsibilities grow over time will be one of the clearest signals of how Clean Science thinks about succession and how much it intends to professionalize the organization while staying family-controlled.

Leadership Philosophy and Incentives

The company’s operating philosophy still looks like it did in the early days: think long term, stay financially conservative, and treat technical excellence as the core asset. Even the incentive structure reflects that. Clean Science’s Employee Stock Option Scheme is modest by public-market standards—6,532 equity shares were allotted as recently as August 2025. This is not a stock-option-driven culture. It’s still overwhelmingly a promoter-family-led business.

That has real upside. When the founding family’s wealth is tied primarily to long-term equity value—not annual compensation—it reinforces patient capital allocation and a willingness to invest through cycles.

But it also brings the classic founder-led question into sharper focus: can the institution outlive the founder? Indian corporate history offers both outcomes—companies that stumbled in transition, and companies that used transition as a moment to strengthen governance, deepen leadership benches, and become genuinely multi-generational.

In Clean Science’s case, there’s an additional twist: in a process-driven chemicals company, the moat lives in people as much as plants. The know-how sits with senior chemists, process engineers, and operators who understand all the invisible variables that make catalytic manufacturing work reliably. A modest ESOP program avoids dilution, but it also raises a quiet, long-term question: is the current incentive toolkit strong enough to retain the talent that actually protects the process moat? It’s not the kind of risk that shows up cleanly in a quarterly earnings call, but it’s one that can compound—either positively or negatively—over time.

IX. Strategic Frameworks: Powers, Forces, and Moats

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

If you want to get rigorous about what actually protects Clean Science, Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers is a good place to start. It forces a simple question: what, specifically, lets this company stay ahead year after year?

Scale Economies are limited in specialty chemicals. This isn’t a commodity game where the biggest plant automatically wins. Volumes are smaller, products are more specialized, and the cost advantage comes less from sheer throughput and more from process efficiency. Clean Science doesn’t win by being bigger. It wins by being better at making the same molecule.

Network Effects are basically nonexistent. There’s no platform here, no marketplace dynamics—just molecules, specs, and supply reliability.

Counter-Positioning is one of the real powers. Clean Science has built its manufacturing around catalytic routes, while many incumbents are still tied to traditional stoichiometric setups. For a large incumbent, switching isn’t just “let’s adopt a cleaner method.” It can mean writing off existing assets, rebuilding plants, retraining teams, and requalifying processes—essentially disrupting their own economics. Even if catalytic processes are superior, incumbents often have very rational reasons to move slowly. That hesitation is where Clean Science can keep widening the gap.

Switching Costs are moderate, but they matter. In food, pharma, and tightly specified industrial applications, qualification can take a long time. Once Clean Science is approved and embedded, changing suppliers isn’t a casual decision—it brings testing, documentation, and operational risk. These switching costs don’t eliminate competition, but they create real inertia.

Branding is weak in the consumer sense. Buyers don’t pay extra because the drum has a recognizable logo. But there is a form of B2B brand that counts: a reputation for consistent quality, dependable deliveries, and the ability to troubleshoot when something goes wrong. In specialty chemicals, that kind of trust is a selling point.

Cornered Resource is another genuine power. Clean Science’s proprietary catalytic know-how—especially the vapor phase anisole hydroxylation process it has said no one else has commercialized—isn’t a patent you can wait out. It’s process knowledge embedded in the organization and protected as trade secrets. In chemicals, that can be more durable than formal IP, because the “recipe” doesn’t reveal itself in the finished product.

Process Power is where the story really concentrates. Clean Science’s advantage isn’t a single breakthrough; it’s a capability. Over years, it built the muscle to develop catalysts, engineer reactions, scale them safely, control impurities, and run plants with repeatable consistency. That kind of know-how isn’t something a competitor can copy by hiring a couple of scientists. It lives across teams, equipment choices, operating discipline, and thousands of small refinements that add up.

The verdict is pretty clean: Clean Science’s defensibility comes from the combination of Counter-Positioning, Cornered Resource, and Process Power. In other words, it has a technology moat—just expressed through reactors instead of code.

Porter's Five Forces

The threat of new entrants is low. This isn’t just about money. A serious entrant needs years of R&D, process scale-up experience, safety systems, customer qualification, and regulatory readiness before meaningful revenue shows up. In many niches, it can take five to ten years to get truly established. Clean Science’s process advantage only stretches that timeline further.

Supplier bargaining power is low to moderate, mainly because of backward integration into anisole. By making a key feedstock internally using its own process, Clean Science reduces a dependency that often squeezes other manufacturers.

Buyer bargaining power is moderate. Customers are large and professional, and procurement teams will negotiate hard. But these products are functionally critical. Most buyers won’t gamble with supply continuity or product performance to win a small price concession—especially when the downside is plant disruption, customer claims, or compliance risk.

The threat of substitutes is low. In many of these applications, the chemical is chosen because it does a very specific job under very specific conditions. MEHQ, for example, is used because its chemistry matches the need. Over the very long term, alternative chemistries can emerge, but the installed base of industrial processes designed around existing inputs creates enormous inertia.

Competitive rivalry is moderate to high. Clean Science competes with global majors like BASF, Lanxess, and Clariant, and it also faces Chinese producers who can be aggressive on price. The niche nature of these markets makes coexistence possible—but only if Clean Science keeps earning its premium through quality, reliability, and cost efficiency.

Competitive Benchmarking

Against global giants like BASF, Clean Science’s edge is surprisingly straightforward: higher margins, simpler focus, and a zero-debt balance sheet compared with sprawling, diversified portfolios that often run at much lower profitability. The trade-off is resilience. BASF’s breadth—thousands of products across many end markets—absorbs shocks in a way a focused company can’t.

Against Indian peers like Atul and SRF, Clean Science stands out for the same reason it stood out pre-IPO: its moat is rooted in process technology, not just competitive execution. Many specialty chemical businesses compete on scale, customer relationships, and cost discipline. Clean Science adds an extra layer: process innovation that can translate into structural cost and quality advantages.

Against Chinese competitors, it gets nuanced. China benefits from scale, often cheaper energy, and state support. Clean Science’s defense is process efficiency, consistency, sustainability positioning, IP protection through trade secrets, and relationships built on dependable supply. Those matter—but they matter most when customers are optimizing for risk, not only price.

Which brings us to “China Plus One.” The slogan makes it sound like a flood of orders is destined to move from China to India. The reality has been more incremental. Some customers have genuinely diversified and shifted volumes. Many others have simply added an Indian supplier as insurance while keeping China as the primary source on price. The demand shift is real, but it’s often backup capacity rather than a full rerouting of supply chains.

Clean Science can benefit from that trend—especially because it’s exactly the kind of supplier you keep in your “reliable alternative” slot. But if your entire investment case depends on a dramatic China-to-India migration, that usually requires a more disruptive catalyst than gradual diversification: sanctions, a major geopolitical escalation, or a serious step-change in enforcement and operating costs inside China.

X. Capital Allocation Scorecard

What They've Done Well

Clean Science’s capital allocation over the past two decades reads like a case study in restraint—and in chemicals, restraint is a superpower.

Start with the zero-debt philosophy. This isn’t just conservatism for conservatism’s sake. It removes an entire failure mode. No bank has ever had a say in strategy. No refinancing window has ever dictated timing. No interest bill has ever siphoned off cash that could have gone into R&D or the next plant debottleneck.

Then there’s the way they’ve funded growth: almost stubbornly, the organic way. The ₹335 crore commitment into Clean Fino-Chem for HALS. Capacity expansions across MEHQ, Guaiacol, and other lines. New product development for BHT and DHDT. The point isn’t the checklist—it’s the pattern. They’ve kept building, and they’ve paid for it with their own cash flows.

The anisole backward integration is the clearest example of capital allocation as strategy. They took a major input cost, pulled it in-house, and turned it into a source of control and profit—all while tightening the moat around multiple products downstream.

And product diversification, even though it’s still early, shows the same long-term mindset. This isn’t management optimizing for the next quarter’s margin print. It’s management trying to increase the number of “shots on goal” the company has over the next decade.

What's Missing: The M&A Question

The most obvious blank spot on Clean Science’s scorecard is acquisitions. They’ve built everything organically. No deals. No roll-ups. No buying a competitor for capacity or a niche player for a process.

That comes with real benefits: no integration headaches, no culture mismatch, no paying up for “synergies” that only exist in a slide deck. In specialty chemicals, where processes are sensitive and customer relationships are built on consistency, those risks are not theoretical.

But it also creates a real question mark. This is an industry where consolidation is normal, and where acquisitions are often the fastest way to buy a new capability—whether that’s a complementary catalytic process, a customer base in a new geography, or a team with specialized technical talent. Clean Science hasn’t used that lever at all.

That doesn’t mean it should. Plenty of great chemical companies—especially the quiet, high-quality European operators—have compounded for decades without doing splashy deals. Still, as Clean Science’s cash pile grows and its ambitions expand beyond its original product set, the option of M&A becomes harder to ignore.

Shareholder Returns

On shareholder returns, Clean Science has leaned toward reinvestment. Dividends have been moderate. There haven’t been buybacks. The biggest cash-out event for shareholders, in practice, has been the promoter family’s selling—starting with the IPO and continuing through subsequent stake reductions.

And the stock has reminded everyone why valuation matters. It went from ₹900 at the IPO to above ₹3,000 at the peak, and by the current period it was trading around ₹1,100. IPO investors are still up, but anyone who bought into the “can’t miss” phase near the top learned a painful lesson: even a great business can be a bad investment when expectations get too far ahead of reality.

Looking forward, capital allocation becomes even more central to the story. With roughly ₹1,400 crore in shareholder funds and no debt, management has real flexibility. Do they keep compounding through organic expansion? Make their first acquisition? Build manufacturing outside India? Step up R&D spend? Each choice sends a signal about what Clean Science wants to become next.

Because there’s a flip side to optionality. A zero-debt, cash-rich balance sheet gives you freedom—but if cash sits idle for too long, it quietly turns into its own kind of misallocation, earning low returns while the core business has historically been capable of much more.

XI. The Road Ahead: Bull vs. Bear

The Bull Case: "Process Power Compounds"

The optimistic read on Clean Science is simple: the company’s real product isn’t MEHQ or BHA. It’s the ability to repeatedly invent a better way to make hard, high-spec molecules—and then scale that process reliably.

HALS is the clearest test of that idea. If Clean Science can run the same playbook it ran in MEHQ—use process innovation to get to a structurally better cost and waste profile, earn customer qualifications, and then scale—HALS could become a meaningful second engine. India’s dependence on imports creates a natural opening, and global buyers looking to diversify away from China add another layer of demand.

Beyond HALS, the bull case leans on repeatability. The commercialization of BHT and the entry into pharma intermediates like DHDT are signals that management is trying to build a broader portfolio, not just defend a few legacy winners. If that pattern holds, Clean Science starts to look less like a “three-product company with great margins” and more like a platform that can keep launching new specialty chemicals where process know-how matters.

The “China Plus One” story has cooled as a market slogan, but it hasn’t disappeared as an operating reality. Many global companies still want a second qualified supplier outside China, especially for functionally critical inputs. Clean Science is exactly the kind of supplier that can get slotted into that role: export-ready, quality-focused, and already embedded in global supply chains.

Then there’s a quieter advantage that could grow louder over time: sustainability. Catalytic routes tend to be cleaner and less wasteful than stoichiometric ones. As global customers face tighter scrutiny on the environmental footprint of their supply chains, “how it’s made” can become part of procurement—not just “how much it costs.” If that happens, Clean Science’s process choices become more than good engineering. They become a commercial edge.

Finally, the balance sheet is the shock absorber. With zero debt and roughly ₹1,400 crore in shareholder funds, Clean Science can keep investing through downturns instead of pausing at the worst possible moment. In a cyclical industry, that ability to play offense while others retrench is a real strategic asset.

The Bear Case: "Niche Trap"

The skeptical view starts with the uncomfortable possibility that the recent margin pressure isn’t a phase—it’s the new baseline. If pricing stays weak, or if competitors (especially in China) close the process gap, Clean Science’s historic premium could shrink. In a business that has been valued like a quality outlier, a structural step-down in margins would change the story.

There’s also a timing risk hiding inside the capex cycle. Capacity has been added, but volumes don’t ramp on a schedule management can fully control. Qualification takes time. Customer adoption can be slow. When utilization lags, fixed costs don’t. If HALS takes longer to scale than expected, the “investment phase” could stretch out, and the drag on profitability could persist longer than the market has patience for.

Customer concentration is another risk that doesn’t always show up cleanly in the headline numbers. Specialty chemicals often mean a smaller set of large, demanding customers. If a key account is lost, replacing that volume isn’t like swapping consumer shelf space—it can mean years of selling and requalification.

And then there’s the core strategic risk: niches have ceilings. MEHQ, BHA, HALS—these are valuable markets, but they’re not infinite. Even with dominant share, each molecule has an upper bound. That means long-term growth requires a steady cadence of new niches, and every new niche brings execution risk. The company doesn’t just have to be good once. It has to be good repeatedly.

Finally, succession matters. Ashok Boob is in his early seventies, and Clean Science’s edge is deeply tied to technical culture and process judgment that the founding team built over decades. Founder transitions are where many family-led Indian businesses stumble. Clean Science will be judged not only on chemistry, but on whether it can institutionalize that chemistry-driven advantage beyond the founder era.

The KPIs That Matter Most

If you want a practical dashboard for tracking whether the bull case or bear case is winning, two signals do most of the work.

First: the EBITDA margin trajectory. In a process-driven company, margins aren’t just a profitability metric—they’re the clearest output of whether process advantage and pricing power are holding. A return toward the historical forty-percent neighborhood would suggest the moat is reasserting itself as the investment cycle normalizes. A sustained step-down into the mid-thirties or lower would raise the tougher question: is this temporary absorption pain, or a structurally harsher competitive environment?

Second: how fast new products become real. Track the revenue contribution from newer lines—especially HALS, BHT, and DHDT—as a share of the whole. If new products start to meaningfully move the mix within a few years, it validates the idea that Clean Science can reproduce its playbook beyond its original core. If the contribution stays small, the company risks becoming what the bear case fears: a brilliant niche player that needs a new niche before the last one has finished paying for the next plant.

Together, those two measures—margins and new-product mix—tell you whether Clean Science is still compounding its process power, or whether the limits of its niches are starting to bite.

XII. Lessons for Founders & Investors

For Founders

Clean Science’s story is a quiet rebuttal to a lot of modern startup mythology. The most obvious lesson is the simplest one: entrepreneurship doesn’t have an age limit. Ashok Boob was fifty-four when he walked away from a stable, three-decade career to start Clean Science. There was no venture capital safety net, no celebrity advisors, no growth-at-all-costs playbook. What he did have was deep domain expertise, a specific technical conviction, and the patience to build the hard way.

That points to the deeper takeaway: in manufacturing, competitive advantage often lives in process, not in slogans. In a world that loves software moats and platform buzzwords, Clean Science shows how durable “how you make it” can be. A catalytic route that others can’t replicate isn’t just a clever reaction scheme. It’s years of experimentation, plant design choices, operating discipline, and accumulated know-how. And unlike many forms of IP, it doesn’t naturally decay on a timer. It compounds—every campaign run and every refinement made quietly strengthens the lead.

Then there’s financial discipline, treated as a founding principle rather than a finance-team aspiration. The zero-debt approach wasn’t something Clean Science stumbled into. It was a deliberate constraint that preserved strategic freedom, reduced existential risk, and forced growth to track what the business could actually fund. In an industry where leverage and capex cycles routinely destroy value—build too much, too early, then spend years digging out—this looks less like conservatism and more like an edge.

Finally, there’s the niche strategy: it can be better to own half of a small, critical market than to be a rounding error in a massive one. Smaller markets often attract fewer determined competitors, reward technical excellence over brute scale, and let a focused company serve customers with a level of consistency and attention that conglomerates struggle to match.

For Investors

Clean Science is a great case study in the difference between a great business and a great investment. By most operating measures, it’s exceptional: strong positions in niche products, technology-led manufacturing, conservative balance sheet management, and promoter ownership that remains meaningfully aligned. But the stock has only been a great investment at certain prices. Investors who bought early did well. Investors who bought near the peak learned the hard truth: quality doesn’t immunize you from valuation.

That’s especially true for companies with strong narratives. “Catalytic chemistry,” “zero debt,” “global dominance,” and the late-career founder arc are powerful ingredients for market enthusiasm. But when a story gets too widely loved, the valuation can rise to a level where even flawless execution is already priced in. This is where fundamentals meet psychology, and why valuation discipline—the margin of safety—matters as much as admiration for the business.

Clean Science also reinforces an evergreen point: cash flow matters. Operating cash flow of about ₹213 crore in FY25 alongside a zero-debt posture is a sign of real earnings power, not just accounting performance. In capital-intensive industries, that distinction is everything.

And the final investor lesson is the one people most often skip: understand the true source of the moat. Clean Science’s advantage is process power—the organizational capability to develop and commercialize catalytic routes and run them reliably at scale. That kind of moat is real, but it isn’t automatic. It has to be maintained through continued R&D, disciplined execution, and retention of technical talent. If the institution stops investing in that capability, yesterday’s edge becomes tomorrow’s catch-up opportunity for competitors.

XIII. Epilogue: The Next Chapter

Recent Developments

By early 2026, Clean Science sat at a real inflection point. Clean Fino-Chem’s HALS facility had moved into commercialization, with production ramping and customer qualifications working their way through the usual, slow B2B gauntlet. BHT and DHDT were also starting to contribute revenue, adding new branches to what used to be a tightly concentrated portfolio.

But the financial statements reflected the cost of building the next act in real time. Margins had compressed, growth had cooled, and the stock had been repriced from the euphoric highs that followed the IPO.

This is the uncomfortable middle passage—the stretch between a first chapter defined by patient building and niche dominance, and a second chapter that has to be earned. Management was spending with conviction, betting that the process playbook that made MEHQ a global stronghold could travel into HALS and beyond. The market, meanwhile, was doing what markets do: withholding faith until the results show up in volumes and margins, not in intent.

What Could Change the Trajectory

On the upside, a clean HALS ramp would change the narrative quickly. If Clean Science can demonstrate the same kind of process advantage in a new category—and scale it into a meaningful revenue engine, potentially as high as ₹500 crore by fiscal 2028—it would validate the diversification strategy and could prompt a re-rating. A sharper shift in global supply chains away from China, triggered by geopolitics, regulatory tightening, or economic disruption, could also accelerate demand for non-China supply. Clean Science is exactly the kind of qualified, export-ready producer that benefits when customers move from “nice to have” diversification to “must have” diversification.

On the downside, the threats are equally concrete. If a Chinese competitor closes the gap—matching catalytic efficiency while also competing aggressively on price—Clean Science’s margin premium could shrink fast. A major customer loss would hurt because replacing specialty chemical volumes isn’t quick; it’s months and years of requalification. Regulatory issues at manufacturing facilities, or a poorly executed founder-to-next-generation transition, could also undermine confidence at precisely the wrong time.

Then there are the slower, less dramatic risks that still matter: tighter environmental norms in India, shifts in import tariffs in key export markets, or end-market demand changes that reduce the need for the company’s specific molecules.

One thing working in Clean Science’s favor is governance optics. By Indian mid-cap standards, the company’s financial reporting has looked clean: audited accounts, no material qualifications, and transparent disclosure of related-party transactions. That’s not something you can take for granted in family-controlled businesses. Still, it’s not a “set and forget” advantage. Promoter transactions, related-party dealings, and any change in auditor relationships are the kinds of signals investors have to keep tracking, cycle after cycle.

The Bigger Picture

Clean Science is ultimately a story bigger than one ticker symbol. It’s a proof point for India’s ambition to become a global specialty chemicals hub. India is already the second-largest chemicals producer in Asia-Pacific, and specialty chemicals are a strategic target for export-led growth. Clean Science looks like the template: deep technical expertise, cleaner processes, global competitiveness, and unusually disciplined finance.

So the real question for 2026 and beyond isn’t whether Clean Science is a good company. The evidence for that is already on the table. The question is whether its catalytic chemistry playbook can keep compounding as it pushes into new products and new customer sets—or whether the natural ceiling of niche strategies shows up before the next engine is fully built.

Clean Science has already proven that innovation in “boring” industries—manufacturing, process engineering, chemical production—can create extraordinary value. The combination of technical excellence, financial discipline, and patient capital is rare. Ashok Boob’s decision to bet on that combination at fifty-four remains one of modern Indian business’s more remarkable founder stories.

What’s unwritten is whether the institution can carry that standard forward beyond the founding generation.

And the answer won’t come from a single analyst note or one quarterly print. It will come from the quiet work in Kurkumbh—where catalysts are refined, yields are nudged higher, impurities are hunted down, and the next set of “small molecules with huge consequences” is made real, one reaction at a time.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music