Atlanta Electricals: Powering the Indian Grid

I. Introduction: The "Hidden Plumbing" of the Energy Transition

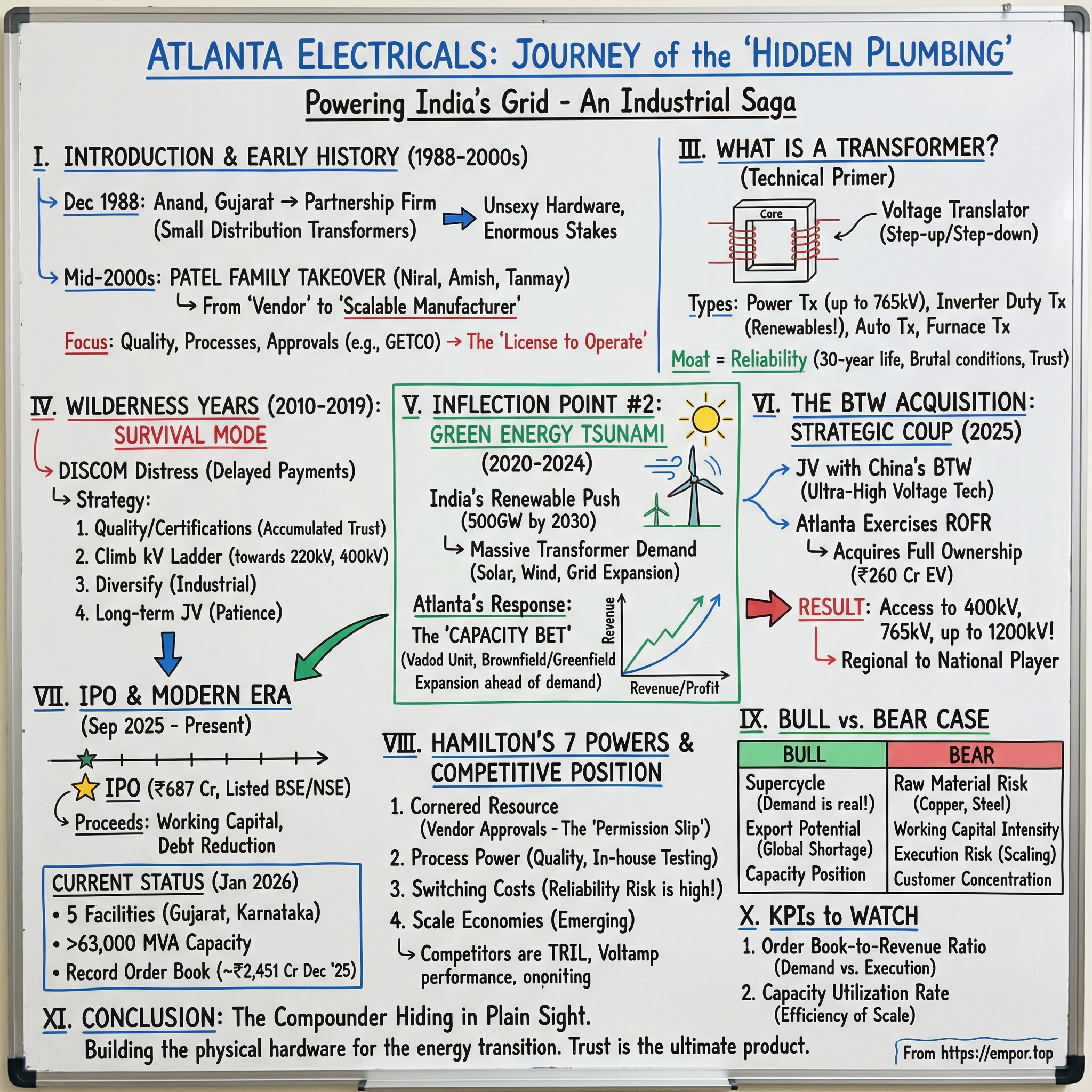

Picture a sprawling solar farm in Rajasthan: hundreds of acres of panels drinking in desert sun, pushing megawatts of clean power toward millions of homes. Now zoom out to the moment that electricity tries to leave the site. Before a single watt can travel hundreds of kilometers to a flat in Delhi or a factory floor in Mumbai, it has to pass through a hulking, oil-filled metal box sitting quietly at the edge of a substation. That box is a transformer. Without it, the solar revolution doesn’t leave the desert.

We love to talk about the sexy parts of the energy transition. Solar panels. Wind turbines. EVs. Battery pack prices and module efficiency charts. But the Indian transformer market—worth roughly $5 billion—mostly runs in the shadows. It’s the hidden plumbing of electrification. And it’s the ultimate derivative bet: for every megawatt of renewable capacity India adds, every data center that comes online, every kilometer of transmission line strung across the country, the grid needs more transformers to step power up, move it, and step it back down safely.

That’s where Atlanta Electricals enters the story.

The company was incorporated in December 1988 in Anand, Gujarat, and has spent more than three decades designing and producing transformers—power transformers, auto transformers, and inverter duty transformers. It started as a modest partnership firm making small distribution transformers. Over time, it quietly grew into one of the more meaningful players in Indian power equipment: the kind of business that isn’t famous, but is absolutely there—inside substations, behind industrial gates, and at the heart of the grid.

Then came the moment the market finally noticed.

Atlanta Electricals launched its ₹687.85 crore IPO from September 22 to 24, 2025, and listed on the BSE and NSE on September 29, 2025. It was a coming-of-age moment: a move from the small-scale vendor world into the mainboard arena, where institutional capital meets industrial ambition. As of January 2026, the company sat at roughly a ₹5,600 crore market cap—around $700 million—looking every bit like a classic mid-cap industrial compounder.

What does Atlanta actually make? Big, high-stakes hardware. It’s among the few Indian companies that can manufacture transformers up to 200 MVA and 220 kV. This isn’t “just manufacturing.” It’s the hardware layer the energy transition runs on—the physical interface between generation, transmission, and everything downstream that depends on electricity behaving perfectly.

And the timing of that IPO wasn’t random.

By the mid-2020s, the transformer shortage had become one of the defining supply chain stories in power infrastructure—showing up in utility capex plans, renewable timelines, and policy debates about grid resilience. What began as a squeeze started to feel like a crisis, driven by years of underinvestment in manufacturing capacity, a post-pandemic surge in construction and electrification, and volatility in key inputs like copper and grain-oriented electrical steel. Atlanta listed right as this narrative hit peak global consciousness.

The transformer—boring, century-old, easily ignored—had become the bottleneck for the entire energy transition.

II. History Part 1: The Technocrats & The Takeover

Atlanta Electricals starts in Anand, Gujarat — a city the world associates with India’s dairy cooperative revolution, not heavy electrical manufacturing. But just outside town, in the GIDC estate at Vithal Udyognagar, there’s a dense little ecosystem of electrical equipment makers that has quietly helped build the backbone of India’s grid. Atlanta was born in that cluster.

In its earliest form, Atlanta was a partnership firm doing something profoundly unsexy: building small distribution transformers, the workhorses that local utilities rely on to step power down safely for towns, neighborhoods, and industrial areas. The founders had a clear read on how Indian infrastructure actually gets built. State electricity boards didn’t just need equipment; they needed equipment that survived Indian conditions — brutal heat, dust, humidity, and voltage that could swing in ways a textbook never warns you about. And they needed vendors who could deliver consistently, not just cheaply.

Gujarat was a particularly fertile place to play this game. GETCO, the state’s transmission corporation, ran a structured vendor registration and qualification system. If you could clear it, you earned something more valuable than a one-time order: you earned permission to compete. That process was tough by design, but it created a clear ladder for manufacturers willing to invest in quality, documentation, testing, and track record.

Atlanta leaned into that. The company built out its base at Vithal Udyognagar, developing the infrastructure and manufacturing setup needed to move beyond “job work” and into serious transformer capability — power, distribution, and specialty units. In this industry, quality isn’t a brand attribute; it’s existential. When a transformer fails, it’s not a warranty claim. It can be a blackout, damaged upstream equipment, and a customer who never comes back.

Formally, Atlanta Electricals was incorporated as a private limited company on December 15, 1988, with the Registrar of Companies in Gujarat at Ahmedabad. In 1996, it converted into a public limited company, changing its name to Atlanta Electricals Limited, with a fresh certificate dated April 10, 1996.

Then came the moment that changed the company’s DNA.

In the mid-2000s, the Patel family — Krupeshbhai Narharibhai Patel and his sons — took control of the enterprise. This wasn’t just capital coming in. It was closer to forward integration: industrial operators stepping into the supply chain with customer context, manufacturing ambition, and a plan to scale.

Niral Krupeshbhai Patel became Chairman and Managing Director. He brought an unusual mix for an Indian transformer promoter: formal engineering training, business education, and deep on-the-ground familiarity with how the transformer world actually works. Over time, he also became associated with other companies in the broader Atlanta ecosystem, including Amod Stampings Private Limited and Venus Laminations Private Limited. His focus sat where it mattered most: customers, suppliers, strategy, and the budget discipline required to turn a manufacturing shop into a scalable organization. He had spent more than two decades in the transformer sector.

Under the Patel leadership, Atlanta’s posture changed. The company stopped behaving like a small vendor waiting for the next purchase order and started acting like a manufacturer building long-term capability. The strategy was simple, but not easy: expand the product range, tighten processes, and methodically secure approvals from utilities across India — the kind of credentials that take years to earn and minutes to lose.

The business also took on a distinctly “family enterprise, professionally run” structure. Amish Krupeshbhai Patel brought experience across real estate and investments, focusing on land acquisition and collaborations — the unglamorous groundwork required for expanding facilities. Tanmay Surendrabhai Patel brought deep operating experience, taking responsibility for procurement and supply chain. With Niral focused on the market and the company’s direction, and Amish and Tanmay anchoring the physical expansion and operational engine, Atlanta could grow without the internal friction that derails so many family-led industrial companies.

And they didn’t rely on family alone. Atlanta brought in professional leadership as well, appointing Akshaykumar Mathur as CEO. With more than two decades in transformer leadership and prior experience at Voltamp Transformers, he took charge of day-to-day execution. The result was a blend that’s rare when it works and powerful when it does: promoter-led vision paired with professional operational control.

That takeover wasn’t a footnote. It was the point where Atlanta stopped being just another local supplier — and started becoming a company built to last.

III. What is a Transformer? A Technical Primer

To understand why Atlanta Electricals matters, you first have to understand what a transformer actually does — and why “making a box of copper and steel” is a lot harder than it sounds.

At its core, a power transformer is a static device that transfers electrical energy between circuits through electromagnetic induction, without changing frequency. Its job is deceptively simple: change voltage so electricity can move efficiently and safely through the system. Think of it as a translator between voltage languages. Power plants and transmission lines “speak” high voltage. Your home, your office, and most factory equipment “speak” much lower voltage. Without the translator, the conversation breaks down.

The physics is elegant. Alternating current flows through a coil of wire — the primary winding — and creates a magnetic field. That magnetic field induces current in a second coil — the secondary winding. Change the ratio of turns between the two coils, and you change the voltage. Step voltage up to move power long distances — higher voltage means lower current, which means less energy lost as heat in the wires. Step voltage down near the point of use, where safety and compatibility matter.

This is the world Atlanta builds for. Historically, it manufactured transformers up to 200 MVA and 220 kV. After its recent acquisitions and facility expansions, Atlanta’s capabilities extended much higher — up to 500 MVA and 765 kV. In transformer-land, those aren’t incremental steps. They’re the difference between being a regional supplier and being able to play in the highest tiers of the grid.

Atlanta’s product mix also tells you where the company is positioned.

Power transformers are the heavy hitters of the transmission network — the huge units in substations that step voltage up from generation sources and step it down again for regional distribution. They’re precision machines expected to run for decades in harsh outdoor conditions. As of December 2025, power transformers made up the bulk of Atlanta’s order book.

Inverter duty transformers (IDTs) are where the modern story gets interesting. Solar and wind farms don’t connect to the grid directly; they push power through inverters, and that introduces technical issues like harmonics that need to be managed. IDTs help make that grid integration stable. Every solar park and wind project needs this category of transformer somewhere in the chain, which makes IDT demand tightly linked to renewable buildout. Even though IDTs were a small portion of Atlanta’s order book as of December 2025, they carry strategic weight well beyond their current share.

Auto transformers are another key category — used for voltage regulation, particularly across transmission networks — and they also represented a meaningful slice of the order book.

Then there are the specialists: furnace transformers for heavy industry like steel, and generator transformers for power generation setups and captive plants. They’re not the volume products, but they reinforce a manufacturer’s breadth and technical credibility.

Here’s the critical industry dynamic: a well-designed transformer is expected to last roughly 30 years. That longevity creates stability — once you’re in, you can stay in for decades — but it also creates brutal conservatism on the customer side. Utilities and industrial buyers do not like switching to unproven vendors for equipment that has to run faultlessly for a generation.

And this is why the “why not just buy the cheapest one?” question misses the point. Transformer failures aren’t like a server going down. A failure at a critical substation can cascade into wider grid issues, damage upstream equipment, and in the worst cases, trigger fires or explosions in oil-filled units. Utilities track reliability obsessively; even small improvements in failure rates become meaningful when the consequence of failure is so high.

This is a moat built from atoms, not software. Copper windings have to be wound and insulated with extreme precision. The core needs specialized grain-oriented electrical steel. Tanks have to survive decades of thermal cycling and weather. The oil has to stay clean, dry, and able to cool the unit properly. And then all of it has to be tested, documented, and certified — not once, but repeatedly — because in this business, your real product isn’t just a transformer. It’s trust that it won’t fail.

IV. The "Wilderness Years" & The Survival (2010-2019)

The 2010s should have been a straightforward growth decade for Indian transformer makers. Instead, it turned into a grind—one where survival mattered more than ambition. And the way Atlanta made it through these wilderness years is exactly what set it up for the surge that followed.

The core problem wasn’t engineering. It was money.

India’s power distribution companies—the DISCOMs—were bleeding. Losses piled up, debt ballooned, and payments to suppliers became unpredictable. In 2015, the Government of India rolled out the Ujwal DISCOM Assurance Yojana, or UDAY, a turnaround package that allowed state governments to take over 75 percent of DISCOM debt outstanding as of September 30, 2015.

UDAY was just the latest response to a problem that wouldn’t stay solved. Even after bailouts in 2002, 2012, and 2015, the sector still struggled. Populist politics didn’t help: many states promised free or subsidized electricity to farmers and lower-income households, leaving DISCOMs with structurally weak cash flows. By 2024, DISCOM losses and debt were still staggering—measured in the trillions of rupees.

For transformer manufacturers, this translated into a brutal operating reality: delayed payments, cancelled orders, and relentless working-capital pressure. Plenty of smaller players didn’t make it. The ones that survived had staying power—stronger balance sheets, patient capital, and the discipline to keep investing when it felt irrational.

Atlanta chose a survival strategy that didn’t look flashy in the moment, but compounded over time. Three pillars defined the decade: quality, certifications, and relationship-building.

The real weapon was approvals. In this industry, you don’t win because you show up with a brochure. You win because you’re allowed to bid.

GETCO’s vendor registration process is a good example of how high the bar can be: manufacturers apply through the Chief Engineer with extensive documentation, pay non-refundable registration fees (ranging from about ₹15,000–25,000 plus GST for Gujarat-based micro and small industries, up to roughly ₹50,000–75,000 for out-of-state manufacturers), and then survive a rigorous qualification process. And that’s just one utility. Getting approved by organizations like NTPC and PGCIL can take years of demonstrated performance.

Atlanta spent the 2010s doing the slow, difficult work of getting on as many approved vendor lists as possible—systematically accumulating the credentials that become a company’s true “license to operate.”

At the same time, it kept climbing the voltage ladder. The journey took a meaningful step in 2010 when Atlanta entered the 66 kV class, but the intent was always to move upward—toward 132 kV, 220 kV, 400 kV, and ultimately 765 kV. Building that capability during a down market wasn’t comfortable. But it meant Atlanta would be ready when demand returned.

The company also made sure it wasn’t totally hostage to the DISCOM cycle. Back in 2006–07, Atlanta developed its first 15 MVA arc-furnace transformer for the steel industry and won an innovation award. Products like these weren’t just technical achievements—they were diversification, a way to sell into industrial customers even when utility capex froze.

And then there was the long game: in 2010, Atlanta initiated a joint venture that was formalized in 2011. The timing was rough—markets were weak—so progress moved slowly. Construction only began in 2016, after about five years of waiting, and was completed in 2018. The JV with Chinese partner Baoding Tianwei Baobian Electric would later become strategically important, but in this decade it was mostly a test of patience: nearly a ten-year commitment before meaningful returns.

This is the part of the Atlanta story that’s easy to skip and impossible to replace. In B2B industrial sales, your vendor registration ID is your permission slip. Atlanta treated approvals and certifications the way a collector treats rare stamps—each one earned slowly, backed by performance data, quality systems, and years of relationship capital.

V. Inflection Point #2: The Green Energy Tsunami (2020-2024)

COVID was supposed to be the kind of event that crushes industrial manufacturers. For Atlanta Electricals, it ended up being the starting gun for an entirely new phase of growth.

The backdrop was policy turning into momentum. India’s renewable push—formalized through the Ministry of New & Renewable Energy and reinforced by the Prime Minister’s COP26 commitment—set an ambitious destination: 500 GW of installed electricity capacity from non-fossil sources by 2030. Solar, wind, hydro, biomass, and nuclear were no longer “supplements” to the grid. They were becoming the grid.

By June 2025, India had already installed 242.8 GW of non-fossil capacity, including 233.99 GW of renewable energy and 8.8 GW of nuclear—just over half of the country’s total installed power capacity of 484.82 GW. Renewable energy alone had nearly tripled in a decade, rising from 76.37 GW in 2014 to 233.99 GW in 2025.

And here’s the part that matters for Atlanta: none of those gigawatts move without transformers.

Every solar park and wind farm needs inverter duty transformers to connect inverters to the grid. Every new renewable cluster needs step-up transformers to push power into transmission. And once power reaches load centers, the system needs more distribution transformers to actually deliver it to homes and factories. If India wanted to reach 500 GW—with solar expected to contribute close to 300 GW—the implied demand for transformers wasn’t a tailwind. It was a tidal wave.

The grid buildout showed up in the data. Central Electricity Authority numbers indicated that India added 86,433 MVA of transformation capacity in 2024–25, up 22.2% from 70,728 MVA in 2023–24. As of March 2025, AC transformation capacity across the 220 kV to 765 kV levels stood at around 1,304 GVA. In plain terms: the country was racing to expand the “muscle” of the transmission network.

Atlanta didn’t watch this from the sidelines. It pushed hard into renewables, building a presence across solar, wind, and hybrid projects in Gujarat, Rajasthan, Andhra Pradesh, and Karnataka. Its customer roster reflected the shift: Adani Green Energy, TATA Power, and GETCO. It also exported to the US, Kuwait, and Oman. These weren’t small wins—they were relationships with some of the biggest developers and most capable buyers in the market.

Financially, the change was visible fast. Between the financial years ending March 31, 2024 and March 31, 2025, Atlanta’s revenue grew 43%, while profit after tax rose 87%. For the twelve months ended March 31, 2025, the company reported consolidated net profit of ₹119.97 crore on sales of ₹1,244.18 crore. After decades of grinding through approvals and capability-building, Atlanta had become exactly the kind of supplier the market suddenly couldn’t get enough of.

But the real story of this era wasn’t just demand. It was what Atlanta chose to do about it.

The defining move was the “Capacity Bet.” Atlanta expanded from a much smaller base into something that could credibly serve large, high-voltage orders. Its scale and capacity reached 47,280 MVA of legacy capacity, plus 15,780 MVA from BTW—taking total capacity to more than 63,000 MVA, with the ability to fulfill large orders up to 500 MVA and 765 kV.

The step-change came with the commissioning of the Vadod unit in July 2025. Capacity jumped from 16,740 MVA to 47,280 MVA—nearly tripling. Importantly, this wasn’t a cautious expansion timed neatly to purchase orders. It was capital committed ahead of full certainty, based on management’s conviction that a transformer supercycle was arriving.

They’d already felt the constraint earlier. In 2023, Atlanta could see it was going to run out of capacity in 220 kV. So it executed a brownfield expansion at Unit-1 to push output higher. Then came the bigger swing: a new greenfield plant in Vadod—Unit-4—built for 220 kV and 400 kV transformers, coming online in 2025.

This is what separates a manufacturer that “benefits from a cycle” from one that compounds through it: the willingness to build the factory before the backlog becomes unbearable—and to do it when getting that timing wrong could hurt.

VI. The BTW Acquisition: A Strategic Coup

Atlanta’s acquisition of BTW-Atlanta Transformers was one of those moves that looks bold in the press release—but was actually years in the making. It was the payoff for a decade-long decision: if you want to play at the top end of the grid, you don’t improvise your way into ultra-high voltage manufacturing. You earn it.

BTW-Atlanta Transformers India Pvt Ltd was incorporated in March 2012 as a joint venture between Baoding Tianwei Baobian Electric Co. Ltd. (the majority shareholder) and Atlanta Electricals Pvt Ltd (the minority shareholder). In FY17, Atlanta Electricals transferred its holding to another group company, Atlanta UHV Transformers LLP. BTW India’s manufacturing plant sits in Bharuch, Gujarat, and commercial operations began in November 2017.

The Chinese partner, Baoding Tianwei Baobian Electric Co., Ltd.—often shortened to BTW—traces its roots back to Baoding Transformer Works, founded in 1958. It’s a heavyweight in power equipment, with products spanning transformers, CTs, and reactors used across generation, transmission, and distribution systems, from 10kV all the way up to 1200kV, with maximum capacity of 1500MVA. In other words: this was a doorway into the technical tier Atlanta ultimately wanted to reach.

That was the point of the JV. It gave Atlanta access to ultra-high voltage technology that would have taken years to build from scratch. But by 2024, the Chinese majority shareholder was looking to exit its Indian subsidiary—and that’s when the situation turned into a contest.

CG Power & Industrial Solutions publicly disclosed that it would be unable to consummate a transaction to purchase shares of BTW-Atlanta from the majority shareholder. The blocker was simple and decisive: the minority shareholder had a right of first refusal. On February 14, 2025, the China Beijing Stock Exchange ran an online bidding process where CG emerged as the highest bidder at around ₹165 crore. But the bid came with an asterisk—it remained subject to the minority shareholder exercising, or waiving, its ROFR.

Atlanta didn’t waive it. It exercised the ROFR and stepped in.

In August 2025, Atlanta Electricals acquired full ownership of BTW-Atlanta Transformers Pvt Ltd—originally structured as a 90:10 joint venture between BTW of China and Atlanta UHV Transformers LLP—at an enterprise value of around ₹260 crore, which included roughly ₹80 crore of borrowings. In the process, Atlanta beat out other interested contenders, including CG and TARIL.

This wasn’t a tactical purchase to juice growth for a quarter. It was the culmination of a long, patient execution cycle—exactly the kind of systematic capability-building Atlanta had been pursuing since it started climbing the kV ladder. The logic was straightforward: Atlanta had always been good at absorbing technology, then industrializing it.

The plant itself made the deal even more strategic. BTW-Atlanta’s facility at Jambusar, Gujarat is readily upgradable to produce transformers up to 1,200kV. As of the acquisition, it could produce transformers in the 400kV and 765kV voltage classes—right where India’s most consequential transmission projects live.

After the acquisition, BTW Atlanta Transformers Pvt Ltd was renamed Atlanta Trafo Pvt Ltd, and it became a wholly owned subsidiary of Atlanta Electricals Ltd.

With the BTW-Atlanta plant under its control, Atlanta moved into an even stronger position to pursue opportunities in the 765kV class. And it wasn’t stopping there: Atlanta was also aiming toward 1,200kV and HVDC as India’s grid evolved.

Strategically, this changed what Atlanta could credibly be. Before BTW, it was a strong player largely in the 66kV to 220kV world. After BTW, it could compete for the biggest, most complex transmission tenders in the country—the 400kV and 765kV backbone of the national grid.

VII. The IPO & The Modern Era (2025-Present)

By the time Atlanta came to market in September 2025, it wasn’t pitching a vision. It was selling momentum—capacity coming online, a transformed product portfolio, and a grid cycle that suddenly needed every credible transformer maker it could get.

The company’s ₹687.34 crore IPO ran from September 22 to September 24, 2025, and listed on the BSE and NSE on September 29. The offering combined a ₹400 crore fresh issue with a ₹287.34 crore offer for sale. The price band was ₹718 to ₹754 per share, with a lot size of 19 shares.

Ahead of the listing, Atlanta brought in anchor capital—allocating 27.14 lakh shares at ₹754 each to 15 anchor investors, for ₹204.70 crore raised.

The use of proceeds reflected the unromantic mechanics of the transformer business. Part of the fresh capital went to debt reduction (₹79 crore). The biggest chunk went to working capital (₹210 crore). Because in this industry, you buy copper, steel, and oil up front, you build a custom piece of equipment to a customer’s specifications, you test it and ship it—and only then do you start the slow process of getting paid, often by large government-linked buyers with long payment cycles. Working capital isn’t a line item. It’s oxygen.

The mainboard listing also marked a psychological shift: Atlanta had clearly graduated from the SME world. It now sat in the public-market peer set alongside established players like Voltamp Transformers and Transformers & Rectifiers India. In FY25, Atlanta’s revenue of ₹1,244 crore made it smaller than Voltamp (₹1,934 crore) and TRIL (₹2,019 crore), but meaningfully larger than Danish Power (₹427 crore). Its return on equity stood out—33.9% versus roughly 17–20% for peers. Its order book was stronger than Voltamp and Danish Power, though still far smaller than TRIL. Profitability was solid but not best-in-class, with EBITDA margins around 16% versus peers typically in the high teens to low twenties.

Current Operations (January 2026)

Coming out of the IPO and the BTW acquisition, Atlanta looked less like a regional manufacturer and more like a scaled platform. The company operated five facilities across Gujarat and Karnataka. As of September 30, 2025, it had supplied 4,607 transformers totaling 101,700 MVA.

Nameplate manufacturing capacity stood at 63,063 MVA across those five locations—four in Gujarat and one in Karnataka. And the thing that matters most in a cycle like this—the backlog—kept climbing. Atlanta’s outstanding order book hit a record ₹2,451 crore as of December 31, 2025, the highest in its history.

The progression tells the story. The order book rose from ₹1,584 crore as of June 30, 2025, to ₹2,069 crore by September 30, and then to ₹2,451 crore by the end of December.

Q3 FY26 brought ₹796 crore of order inflows, including a major ₹298 crore order from GETCO for 25 high-capacity transformers—21 of them 220/66 kV, 160 MVA units. Atlanta also won a ₹134 crore order from Adani Green Energy for inverter duty transformers.

In Q2 FY26, it picked up roughly ₹100 crore of orders for large solar pooling substations across Rajasthan and Karnataka—another signal that renewables weren’t a side business anymore; they were a core demand engine. And on exports, Atlanta landed a ₹20 crore order for 132/33 kV and 33/11 kV transformers, marking its entry into key markets across Asia and the Middle East.

This is what Atlanta looked like post-IPO: more capacity, bigger voltage classes, and a backlog that suggested the transformer supercycle wasn’t a headline—it was flowing straight into the factory gates.

VIII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis & Competitive Positioning

Cornered Resource: The Primary Power

Atlanta’s biggest edge isn’t a secret process or a clever sales pitch. It’s something far more boring, and far more powerful: vendor approvals.

In India’s grid business, you don’t “go win” a government tender. First, you earn the right to even show up. Utilities want years of documented performance before they’ll let you bid, and that record can’t be manufactured overnight—especially for high-voltage equipment where failures become public, expensive, and politically painful.

Atlanta has been building that permission slip for more than 30 years. Over time, it expanded its footprint across 19 states and three union territories. That reach matters, but the real asset is the accumulated trust embedded in those registrations. For a new entrant—whether a domestic startup or a foreign manufacturer—the hurdle isn’t just building a factory. It’s building years of track record to get on the list. And that incumbent advantage compounds.

Process Power

Transformers are supposed to live for decades. Thirty years is the industry thumb rule. But “lasting” isn’t just about the copper and the core inside the tank—it’s about surviving Indian reality outside it: brutal heat, monsoon humidity, dust, and the kind of operating conditions that punish every shortcut.

A 220kV transformer that keeps doing its job for 25 years in the field is not a trivial engineering accomplishment. Utility buyers obsess over failure rates because the product isn’t judged at commissioning. It’s judged years later, when it either keeps running quietly or becomes a headline.

Atlanta reinforces this with in-house testing capability. Its test labs can perform all tests except short-circuit tests for transformers and reactors up to 765kV, for both domestic and export markets. That doesn’t just improve quality control—it shortens feedback loops and reduces dependence on external testing capacity that competitors would need time to secure.

Switching Costs

For a customer like Adani or Tata, a transformer might be a small slice of the capex of a solar park—maybe around 5%—but it carries essentially all of the failure risk. If it fails, generation stops. In the worst case, the failure damages interconnected equipment and creates broader grid issues. The downside is so asymmetric that “cheaper” is rarely the winning argument.

This is why switching costs in this market are real, even when purchase orders look transactional. Buyers may tender aggressively, but once a supplier proves reliable, the incentive to take a gamble on an unproven vendor drops sharply.

Atlanta’s customer concentration underscores both sides of that coin. In FY 2025, 74% of revenue came from its top 10 customers. That’s a genuine concentration risk—losing a large utility would hurt—but it also signals the depth of relationships that are hard for competitors to dislodge.

Scale Economies (Emerging)

With 63,063 MVA of manufacturing capacity across five locations, Atlanta is starting to unlock scale advantages that smaller regional players simply can’t match. Bigger volume improves procurement leverage for key inputs like copper and silicon steel, and scale also helps spread engineering, testing infrastructure, and overhead across more output.

This is one of those advantages that looks modest at first—and then becomes decisive as the cycle tightens and everyone is fighting for the same materials, the same skilled labor, and the same delivery slots.

Competitive Landscape

Atlanta isn’t alone in the Indian transformer market. It competes in a field with several credible, established manufacturers—especially in the high-voltage segment.

One major player is Transformers & Rectifiers India (T&R). TRIL manufactures power, furnace, and rectifier transformers, including high-voltage classes like 220kV, 400kV, 765kV, and 1,200kV. It has installed capacity of 37,200 MVA across India and is well equipped to scale with the market.

Another key competitor is Voltamp Transformers, originally incorporated in Gujarat in 1967. Voltamp designs, manufactures, and supplies transformers, with a long operating history and a large installation base in India and overseas. It is professionally managed, debt-free, and carries a CARE AA Stable rating—positioning it strongly with quality-conscious corporate and private utility customers. In FY 2023–24, Voltamp reported annual sales of ₹1,616.22 crore.

Against these peers, Atlanta’s positioning is distinct. It has been more tightly centered on power transformers than Voltamp’s broader industrial mix, and it has been more geographically concentrated than TRIL’s national footprint—at least historically. But post-IPO, with expanded capacity and the higher-voltage capability brought in through BTW, Atlanta’s competitive set has shifted. It’s no longer just trying to win locally. It’s stepping onto the same field as the national heavyweights.

IX. Bull & Bear Case

The Bull Case

The Supercycle Argument

The bull case for Atlanta is simple: India is only a few years into what could be a multi-decade electrification buildout, and transformers are a non-negotiable input.

Peak power demand has already surged from about 130 GW in 2014 to 243 GW in 2024, and it’s projected to cross 400 GW by 2030. That kind of step-up can’t be solved with tweaks and efficiency. It requires concrete and copper: new generation, new transmission, and a thicker distribution network to actually deliver the power.

Layer on top the government’s push to integrate 500 GW of renewables by 2030, including 280 GW of solar and 140 GW of wind. Renewables don’t just need more megawatts of generation; they need more grid to move that power from where it’s produced to where it’s consumed. Transmission stops being “infrastructure in the background” and becomes the critical path.

Then you get the modern load drivers: data centers, EV charging, and the manufacturing push under Make in India. Each one is electricity-hungry, and each one forces new substations, new lines, and more transformation capacity. If you believe those trends are durable, you’re implicitly betting on sustained transformer demand.

Export Potential

The transformer shortage isn’t only an Indian story. Globally, utilities have been caught with long lead times and not enough domestic manufacturing capacity—especially in the US.

Since 2019, US demand for power transformers and distribution transformers has jumped sharply. And despite that demand, only about one-fifth of US transformer needs can be met domestically. The North American Electric Reliability Corp. noted that lead times stretched to around 120 weeks in 2024, with large power transformers taking as long as 210 weeks.

That gap creates a rare opening: overseas manufacturers with the right quality systems, certifications, and available capacity can become emergency suppliers to Western utilities that simply need equipment, period. Atlanta has already started to step into this, with export orders across the Middle East and Asia Pacific.

The Capacity Position

Atlanta’s other bull-case advantage is very practical: it has meaningful capacity online right now. With more than 63,000 MVA of nameplate capacity and an order book at record levels, it can capture demand that more capacity-constrained competitors may be forced to delay or decline.

The Bear Case

Raw Material Risk

Transformers are commodity-sensitive products built from a brutal shopping list: copper, steel, and oil, plus specialized materials that don’t have many substitutes. Post-COVID, the sector has faced raw-material shortages, tight skilled labor, and shifting policies.

One pressure point is grain-oriented electrical steel (GOES), where prices have hit record highs. The US relies on a single domestic supplier of GOES, which shows how fragile that supply chain can be.

Atlanta can often pass higher input costs through to customers, but not instantly. That timing gap—costs rising now, pricing catching up later—can squeeze margins.

Working Capital Intensity

This is a working-capital business by design: you buy raw materials up front, build to spec, deliver, and then wait to get paid—often by government-linked entities with long payment cycles. If customers delay or default, cash flow can get stressed quickly.

There’s also balance-sheet and integration risk tied to the BTW acquisition. The acquired subsidiary carried a sizeable loan (₹804.6 million) and reported negative net working capital in FY 2025. Independent auditors flagged a going-concern issue for BTW because of that negative working capital. Atlanta may have gained capability, but it also inherited complexity.

Execution Risk

Atlanta made a huge capacity bet. The question now is whether it can actually fill it—without quality slipping.

Scaling transformer production is not like adding shifts at a packaging plant. It’s engineering-heavy, testing-heavy, and failure-intolerant. The risk set is broad: intense competition, heavy dependence on raw-material prices, sensitivity to government policy and capex cycles, customer concentration, and the possibility that capacity ends up underutilized.

There’s also profitability headroom to defend. Atlanta’s EBITDA margin of around 16% trails the best listed peer, Voltamp, at roughly 23%. If pricing turns competitive or inputs spike, margins could compress further.

And while Atlanta now has capability up to 765 kV, its historical depth has been strongest below 220 kV. Winning mega-projects consistently means going up against more established players, and the learning curve at the top end of the grid is steep.

Customer Concentration

Finally, concentration risk is real. In FY 2025, FY 2024, and FY 2023, about 74.21%, 64.82%, and 79.87% of revenue, respectively, came from the top 10 customers. If even one major customer relationship weakens, the impact on revenue and profitability would be meaningful.

X. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you’re trying to track Atlanta Electricals as a long-term business—not just a stock—two signals do most of the heavy lifting. They tell you whether the demand wave is real, and whether Atlanta is actually converting that wave into output.

1. Order Book-to-Revenue Ratio

In this industry, the order book is the closest thing you get to a forward-looking revenue map. Atlanta’s backlog has climbed steadily, from ₹1,584 crore as of June 30, 2025, to ₹2,069 crore by September 30, 2025, and then to ₹2,451 crore by December 31, 2025. Against trailing revenue of roughly ₹1,250 crore, that’s about two years of revenue visibility sitting on the books.

What this ratio really measures is the balance between demand and execution. When it rises, demand is outpacing deliveries—great for confidence and sometimes pricing power, but it can also signal strain on capacity and working capital. When it falls, either demand is cooling or the company is shipping faster than new orders arrive—which can be good for cash flow, but might be an early warning on growth if it persists.

2. Capacity Utilization Rate

The second metric is whether Atlanta’s capacity expansion is actually earning its keep.

Atlanta now has 63,000+ MVA of capacity, and it didn’t get there gradually. The biggest step-change came when the Vadodara unit was commissioned, taking capacity from 16,740 MVA to 47,280 MVA. That kind of jump can be a compounding machine—if the company can fill it at good economics—or a drag, if the added capacity sits underutilized.

A practical way to watch this over time is to track how effectively Atlanta converts capacity into revenue—essentially, whether revenue per MVA is holding up as capacity scales. If revenue grows in line with the new footprint, the bet is working. If it lags, returns can dilute even in a “good market.”

XI. Conclusion

Atlanta Electricals is the kind of company markets often overlook until they can’t. It’s not flashy. It doesn’t sell an app. It builds the heavy, oil-filled equipment that makes the rest of the energy transition possible—and that’s exactly why it can be such a quiet compounding machine.

Atlanta isn’t a “tech” company in the conventional sense, but it manufactures the hardware layer the software layer depends on. Every solar park announcement, every data center buildout, every EV charging network expansion eventually has to touch the grid. And when it touches the grid, it needs transformers. The real question isn’t whether demand will exist—it’s which manufacturers will reliably deliver.

This is where Atlanta’s recent chapter matters. With expanded capacity, entry into the 400 kV and 765 kV classes, and growing traction in renewable transmission and export markets, the company has moved into a higher league. Now the job is straightforward to state and hard to execute: keep quality high, deliver on time, manage working capital, and keep earning trust—because in transformers, trust is the product that lasts the full 30-year life cycle.

There’s also a geographic sub-plot to the whole story. Gujarat has produced a generation of transformer manufacturers—Voltamp, TRIL, and now Atlanta—that helped build the backbone of India’s electrification. That multiple winners emerged from the same region isn’t an accident. Industrial clusters create their own gravity: shared suppliers, skilled talent, and hard-won know-how that spreads through the ecosystem and strengthens everyone who can keep up.

As Chairman and Managing Director Niral Patel put it: “Our order book remains healthy at Rs.2,069 crore as of September 30, 2025, providing clear visibility for the next few quarters. From a business perspective, we are witnessing sustained traction across our product segments, particularly in power transformers catering to utilities, renewable projects, and industrial applications.”

The IPO timing, in hindsight, looks almost perfect. Atlanta listed just as the global transformer shortage hit peak awareness and India’s renewable buildout accelerated under climate commitments. Maybe that was foresight, maybe it was luck—but the bigger point is that the underlying demand doesn’t depend on market mood. Electrification is still happening, and the grid still needs steel-and-copper reality to match the ambition.

Atlanta Electricals is a reminder that the energy transition isn’t only built with software and semiconductors. It’s built with copper, steel, oil, and the kind of precision manufacturing that has to work quietly, outdoors, for decades. In the race to electrify India, someone has to make the transformers—and Atlanta has worked for years to make sure it’s one of the companies that can.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music