Amagi Media Labs: The Cloud That Ate Television

I. Introduction: The "AWS of Broadcast"

Picture a Friday evening in 2024. Somewhere in the U.S., someone turns on a Samsung smart TV. No cable subscription. No satellite dish. Just a grid of channels—free, 24/7—and within seconds they’ve landed on a live news feed.

The commercials feel… eerily relevant. Like the TV somehow knows they’ve been shopping for running shoes.

To the viewer, it’s frictionless. To the media industry, it’s a minor miracle. And behind it—quietly doing the unglamorous, mission-critical work of getting channels on air, keeping them on air, and making sure ads show up where they should—is a company most people have never heard of: Amagi Media Labs.

Amagi was founded in 2008 and now sells something that sounds almost impossible if you grew up with broadcast engineering: cloud-native, software-as-a-service tooling that replaces the traditional TV “control room.” Instead of racks of hardware and satellite uplinks, broadcasters and streaming platforms can run channels over the internet—across smart TVs, mobile devices, and apps—then monetize those channels with targeted advertising.

This is not small-stakes streaming, either. Amagi’s technology has been used to power coverage of marquee events, including the 2024 Paris Olympics, UEFA football tournaments, the Academy Awards (the Oscars), and the 2024 U.S. Presidential debates.

Industry reports describe Amagi as the media and entertainment industry’s only end-to-end, AI-enabled cloud platform in the video category—an “industry cloud” for modern TV.

And the footprint is enormous. Amagi operates across the major Connected TV and FAST ecosystems, including The Roku Channel, Samsung TV Plus, XUMO, PLEX, VIZIO, Redbox, and Pluto TV. Its customer list reads like a global media map: ABS-CBN, A+E Networks UK, beIN Sports, CuriosityStream, Discovery Networks, Fox Networks, Fremantle, NBCUniversal, Tastemade, Tegna, USA Today, Vice Media, and Warner Media.

But the part that makes Amagi worth a deep dive isn’t just the roster—it’s the bet.

While the world obsessed over Netflix and the subscription streaming wars, three engineers in Bangalore made a contrarian call: “linear TV”—the old-school idea of channels that run 24/7—wasn’t dying. It was migrating. From satellites and cable headends to software and cloud infrastructure.

That thesis has aged remarkably well. Amagi was recognized with a 75th Annual Technology & Engineering Emmy Award for its pioneering role in manifest-based playout technology—one of the key innovations that helped FAST explode. The company is trusted by two-thirds of the top 100 global media brands.

So here’s the question that drives this story: how did three friends who once built a Bluetooth stack end up building what looks like the cloud backbone of modern television?

They co-founded Amagi after their previous venture, Impulsesoft, was acquired by NASDAQ-listed SiRF. And now, with Amagi preparing to list on BSE and NSE—tentatively on January 21, 2026, with a price band of ₹343 to ₹361 per share—the company is stepping into a new spotlight.

Is this the next Infosys: an Indian company that rewires a global industry? Or is it a niche SaaS player that will struggle to defend premium pricing as competition catches up?

To answer that, we have to go back—before “cloud playout” was even a phrase—to the first time these founders proved they could build world-class infrastructure from India.

II. The Pre-History: The "Impulsesoft" Bond

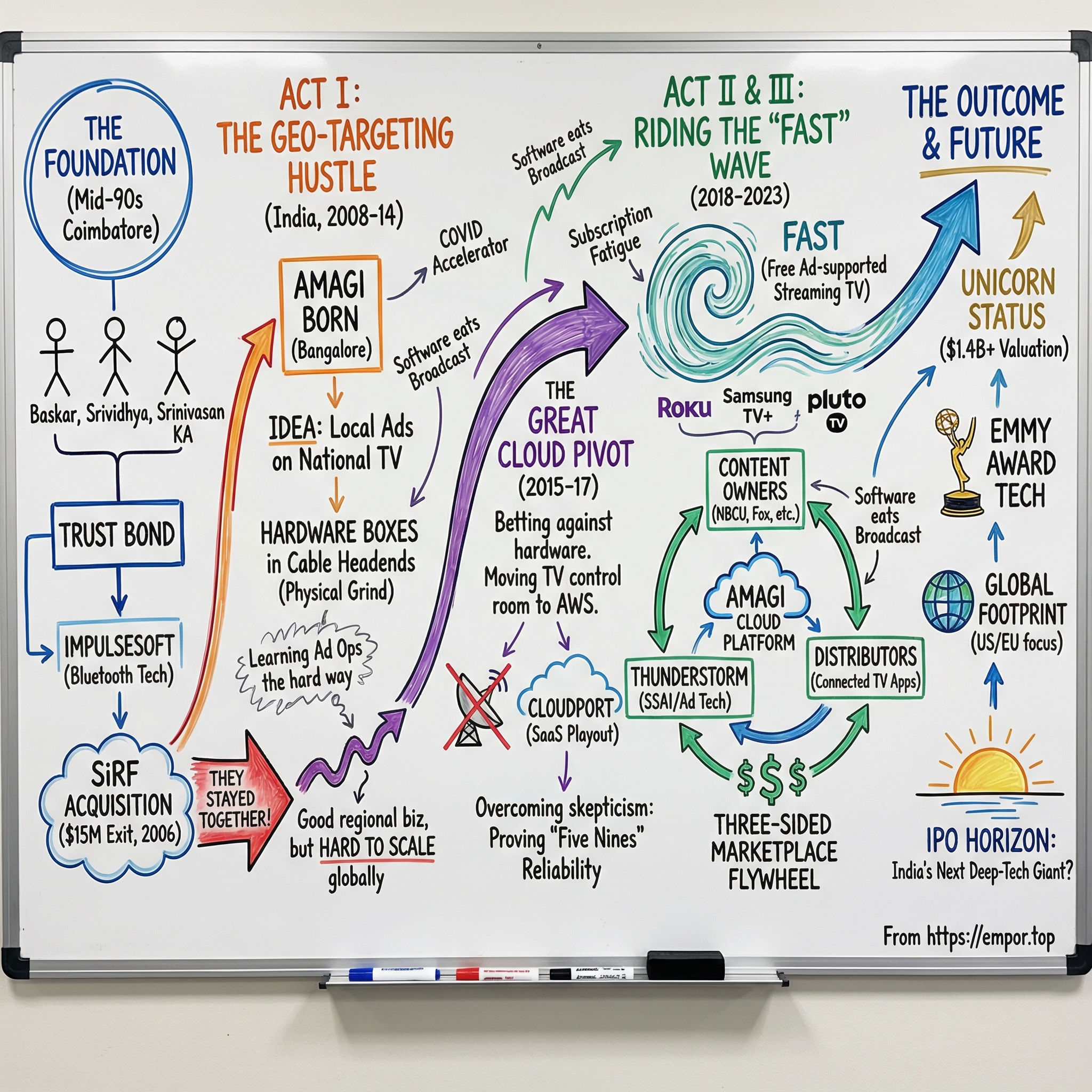

To understand Amagi, you have to start with its founders—and a friendship that formed in the computer labs of Government College of Technology in Coimbatore in the mid-1990s.

Baskar Subramanian, Srividhya Srinivasan, and Srinivasan KA met there as students. Long before “cloud playout” or FAST was on anyone’s radar, the three of them were already building the thing that matters most in infrastructure businesses: trust in each other’s judgment under pressure.

That bond turned into a company.

In 1998, when Srividhya was just 24, she co-founded her first startup, Impulsesoft, with Baskar and Srinivasan. Starting a tech company in India in the late 1990s was hard for anyone. For a woman founder, it came with a particular kind of friction. Srividhya has spoken about one early experience from college: as a computer science student, she lived in a hostel with a strict 6:30 p.m. curfew for girls. She was learning computers for the first time, and the restriction made it painful to keep up—especially when late hours were often when lab time and real learning happened. She once returned late and described being questioned in an embarrassing way by the warden. Her father ultimately moved to Coimbatore so she could stay with him and continue her studies without the curfew limiting her.

Baskar’s origin story, meanwhile, reads like pure middle-class ambition colliding with a technical obsession. In the 1990s, inspired by the rise of companies like Microsoft, he wanted to build software long before his family could afford a computer. So he improvised—writing and testing code wherever he could, including school computer labs. He began selling software while still in school, in 11th standard, and carried that entrepreneurial momentum into engineering at GCT Coimbatore.

After college, Baskar even secured admission to the MTech program at IIT Bombay—but chose to drop out. He later worked at Texas Instruments, building the kind of deep engineering chops that would show up again and again in the companies he helped create.

Impulsesoft itself was early to a wave that hadn’t fully arrived yet. Based in Bangalore with a branch office in California, the company became known for Bluetooth audio solutions for original equipment manufacturers. It helped customers ship products across categories like digital media players, mobile phones, and automotive. Along the way, the team built audio headsets in 2002 and a pioneering Bluetooth watch in 2004—products that were pointing toward a wireless, always-connected consumer world before smartphones made it mainstream.

Then came the first big validation.

In January 2006, NASDAQ-listed SiRF Technology Holdings acquired Impulsesoft for $15 million in cash and stock. SiRF described Impulsesoft’s software platforms as enabling a richer wireless audio experience over Bluetooth and helping customers differentiate in the market. Impulsesoft became a wholly owned subsidiary, and all 55 employees joined SiRF, with the Bangalore team working alongside SiRF teams around the world.

A $15 million exit in 2006 in India was a meaningful outcome—this was well before the unicorn era reshaped expectations. And it’s also the point where most startup stories splinter. Acquisitions tend to send founders in different directions: new jobs, new cities, new priorities.

But Baskar, Srividhya, and Srinivasan KA did something unusual. They stayed together. After the SiRF acquisition, they started looking for the next hard problem where technology could create real disruption and value.

For investors and for this story, that continuity is the tell. These three co-founders have now spent nearly three decades working together—across two companies, multiple reinventions, and whatever it takes to survive long enough to find product-market fit twice. That kind of durable founder chemistry is rare. It’s what Hamilton Helmer would call a cornered resource: a team that has already proven it can rebuild itself without breaking apart.

III. Act I: The "Geo-Targeting" Hustle (2008–2014)

Amagi’s founding story starts with a small moment that the team still tells like folklore.

It’s a Monday morning in early 2008. The three founders are sitting in a park, between ventures, doing what founders do after an exit: brainstorming what to build next. A young palmist walks up and offers to predict their future. He’d read the room correctly—three people with time on their hands are great customers for destiny-on-demand.

That tiny act of “targeting” sparked the idea.

If a palmist could pick the most likely buyers in a park, why couldn’t television do the same—at scale? The founders landed on a problem hiding in plain sight: TV advertising in India was powerful, but blunt. It reached everyone, everywhere, whether that made sense or not.

Amagi was founded in 2008 in Bengaluru, and its first business wasn’t “cloud broadcasting.” It was targeted TV advertising—trying to make the biggest advertising medium in the country accessible to the kinds of businesses that could never afford it.

The pain was obvious. In India at the time, TV ads were essentially national by default. If you were a car dealer in Mumbai and wanted to run an ad on Star Plus, you couldn’t just buy Mumbai. You had to buy India. You’d pay to reach viewers in Chennai who would never step into your showroom. It was inefficient, expensive, and it shut out thousands of small and medium advertisers.

The founders believed there was a better way: localize the same channel feed so different geographies could see different ads.

By 2010, Amagi had a service that enabled state-wise and language-wise local advertising on Indian TV channels in the cable-and-satellite era. The first pitch to the TV channels went well—at least on paper. The channels liked the technology. But there was a catch. As Baskar later put it: “All the TV channels said, we love the technology, but we’ve never done local advertising. So, we cannot really use the technology.” So Amagi did the only thing that would make the market real: they decided to build the business model themselves. “At that moment, we decided that we will build our own advertising sales… We then built a sales company, Ad Sales.”

Under the hood, the system was elegantly simple in concept and brutal in execution. Amagi built a hardware box that sat at the local cable operator’s headend—the place where signals are processed before they get pushed out to homes. The box would watermark the satellite feed, detect the exact ad break, and splice in a local commercial over the national one with frame-level precision.

The first geo-targeted ad using Amagi’s tech aired in 2009. Within two years, the company had expanded to more than 100 cities.

And then came the classic infrastructure startup trap: chicken and egg.

To sell real advertising, they needed scale—thousands of boxes deployed across a wildly fragmented cable-operator landscape. But to afford the rollout, they needed advertising revenue. The founders had to learn advertising from scratch while building a nationwide deployment engine. Baskar described that learning curve bluntly: “We have no tech background in advertising and started learning new things.” Over a few years, he said, they built infrastructure across roughly 20,000 locations, buying large amounts of ad inventory from major networks like Colors and Zee TV, and working with big advertisers like Unilever and Pepsi.

None of that happened from behind a laptop. This phase meant the founders traveling—often to remote towns and villages—cutting deals with local cable operators, and getting boxes installed in dusty, cramped server rooms. It was operationally intense and hardware-heavy. Not glamorous. Not scalable in the way SaaS investors like to hear. But it forced Amagi to understand how television advertising actually works end to end: inventory, placement, measurement, and monetization.

That experience became the hidden asset.

Because while Amagi would eventually become a global software company, it earned its early scars in the real world of broadcast—an industry built on legacy infrastructure and conservative instincts. The founders didn’t just build tech. They became operators who knew how to ship a system that had to work every day, in messy conditions, with real money on the line.

And when they later walked into meetings with global broadcasters who were skeptical of a startup from India, they weren’t pitching theory. They were pitching something they’d already done the hard way.

IV. Act II: The Great Cloud Pivot (2015–2017)

By 2015, Amagi had built a respectable business in Indian geo-targeted TV advertising. But the founders were staring at an uncomfortable truth: the model was never going to travel well.

It was hardware-heavy. It was operationally intense. And every new geography would mean replaying the same grind—deploy boxes, negotiate with cable operators, stand up local sales. That’s not a product you scale. That’s a machine you keep feeding.

At the same time, the rest of enterprise computing was undergoing a once-in-a-generation shift. AWS had proven that serious, mission-critical workloads could live on the public cloud. Companies were moving everything—storage, databases, compute—to AWS and Azure.

Broadcasting, though, was the holdout.

The prevailing belief was simple: television is different. You can’t run a 24/7 channel over the internet. The reliability isn’t there. Because in broadcast, failure isn’t a bad user experience—it’s dead air. A dropped frame during a marquee live event can become a headline.

That’s exactly why the pivot was so audacious.

Amagi’s flagship product, CLOUDPORT, was first conceptualized in 2012. Back then, the company had just one customer for cloud-based media management and was catering only to non-live content formats. But over the next few years, that idea kept growing teeth. By 2016, Amagi had transitioned to a full cloud playout solution—software capable of running the thing broadcasters fear messing with most: the output feed.

And this wasn’t a side project. It was a reorientation of the company. Amagi, which had started as an advertising solution provider for local businesses and TV channels, eventually dropped that model and began building around a SaaS approach, starting afresh with cloud broadcasting as the core.

This was the bet that would define Amagi’s future: move the entire TV control room—playout, graphics, scheduling—into the cloud. “We saw a need for more agility and control in broadcast advertising—and that’s where Amagi’s journey began,” Baskar says.

To appreciate how radical that sounded in the mid-2010s, it helps to understand what playout actually is. Playout is the final system that pushes video out to viewers. If it fails, the screen goes black. Traditional broadcasters spend heavily on redundant hardware, backup power, and round-the-clock monitoring because the tolerance for downtime is basically zero.

So the team wasn’t just shipping software. They were asking an industry built on physical infrastructure and conservative instincts to trust the public cloud. That meant educating clients, absorbing skepticism, and iterating relentlessly until the platform could prove—under real conditions—that it belonged in broadcast.

CLOUDPORT became the foundation for media companies to move from fragmented, hardware-intensive stacks to cloud operations designed for speed and scale. With linear and live playout through CLOUDPORT, media companies could run FAST linear channels across OTT apps and FAST platforms without building a traditional broadcast facility.

The technical bar here was brutal, and Amagi aimed for broadcast-grade reliability. The company says it can support a playout SLA of up to 99.999 percent—“five nines.” In plain English, that’s less than five minutes of downtime a year, a benchmark typically associated with the old world of dedicated broadcast infrastructure.

Underneath, the platform was engineered for resiliency on AWS, with different levels of service based on business requirements. Amagi’s distributed architecture supports rapid recovery of the control plane, with sub-one-minute recovery time objectives using a multi-AZ option, and a 10-minute recovery time objective for regional failover across multiple regions. The point wasn’t just theoretical uptime. It was continuity through real outages, without the channel falling off air.

Of course, none of this mattered unless traditional broadcasters believed it.

Convincing them was a grind. But Amagi’s approach was pragmatic: build what the industry actually needed, not what sounded futuristic in a pitch deck. They focused on the unsexy problems—resilience, workflow, reliability—and that’s what gradually earned trust in an industry famous for resisting change.

For an investor, this pivot reveals the most important trait in the Amagi story so far: the willingness to kill a cash cow to chase something bigger.

The India advertising business worked. Revenue was growing. But the founders recognized it for what it was—a regional business with hard ceilings. The cloud pivot was risky. It meant rebuilding technology, changing how they sold, and walking into global markets where nobody was waiting for a startup from Bangalore to reinvent broadcast.

But it also put them in position for the wave that was about to hit.

V. Act III: Riding the "FAST" Wave (2018–2023)

By 2018, a new acronym started showing up at every media conference: FAST—Free Ad-supported Streaming TV.

The pitch was almost embarrassingly simple. Take the old-school TV experience—scheduled programming on channels—and deliver it over the internet. Make it free for viewers. Pay for it with ads.

After a decade where the industry narrative was “everything becomes on-demand,” FAST was a reminder that people still like to turn something on and let it run. And it arrived at exactly the right moment. Subscription fatigue was real. Amagi’s industry reports point to millions of consumers canceling paid streaming subscriptions in 2021, even as demand for lean-back, channel-style viewing kept climbing. Hub Entertainment Research found that a majority of viewers were tuning into FAST regularly, and FAST services had been steadily growing.

For Amagi, this wasn’t just a trend. It was the market they’d re-architected the company to serve.

Their own platform metrics captured the shape of the wave: channel counts rising fast, ad impressions surging even faster, and viewership hours following right behind. The takeaway mattered more than any single percentage point—FAST wasn’t creeping forward. It was compounding.

Then COVID hit, and the industry’s timeline snapped forward.

Broadcasters who would’ve taken years to modernize suddenly needed to run operations from living rooms, not control rooms. Distributed workflows went from “nice to have” to existential. Cloud adoption jumped, and Amagi benefited directly—posting dramatic year-over-year quarterly growth in 2020. During that period, the company scaled to support hundreds of channels across its platform, along with a sprawling set of delivery endpoints across services like channel creation, distribution, and monetization. As Amagi put it at the time, 2020 became a pivotal year in establishing leadership in cloud-based video distribution and monetization.

FAST also pulled Amagi deeper into the part of the stack where the money is: ads.

Its THUNDERSTORM SSAI platform handled more than a billion ad opportunities each month, as streaming TV became a larger and larger part of the business—growing roughly twenty-fold and reaching nearly half of overall revenues at one point. This was the new flywheel: more channels meant more ad inventory; more ad inventory meant more monetization; better monetization pulled in more channels.

This is where the “shovel seller” framing becomes real.

If you were a content owner—say, Bon Appétit or USA Today—and you wanted a 24/7 channel on The Roku Channel or Samsung TV Plus, the hard part wasn’t the content. It was everything around it: playout, scheduling, distribution, ad insertion, reporting, the constant operational vigilance of keeping a channel on air. Amagi offered an end-to-end path that could move at internet speed—days, not months. The company highlighted meaningful operating cost savings versus traditional delivery models, and it built a widening web of partnerships across FAST platforms and the broader streaming ecosystem while continuing to add channels at a rapid pace.

Once the flywheel was visible, the capital showed up.

In September 2021, Amagi raised $100 million from Accel and other investors. In March 2022, it raised another $95 million from Accel, Norwest Venture Partners, and Avataar Ventures—pushing the company into unicorn territory. Later that year, in November 2022, General Atlantic led an investment of over $100 million, including $80 million in primary capital, valuing Amagi at $1.4 billion—up from the $1 billion valuation reached earlier in 2022. Around this time, the company also crossed the $100 million ARR mark after a strong quarter.

General Atlantic’s Shantanu Rastogi summed up the thesis: Amagi had repeatedly anticipated key trends—moving early on FAST, and using cloud tech to improve outcomes for broadcast and streaming partners globally.

And the broader market kept validating the direction. Industry forecasts projected global FAST revenue rising to roughly $11.68 billion in 2025. Viewing kept climbing too: U.S. audiences streamed materially more FAST hours through August 2025 than the same period in 2024. Reports also showed growing household engagement, with weekly FAST usage rising and total viewing time across platforms increasing sharply year over year.

The investor takeaway is straightforward: Amagi didn’t just ride the FAST wave. It positioned itself as the infrastructure that made the wave scalable. Cloud playout got channels on air. SSAI and monetization tooling helped those channels make money. And deep integrations with platforms made Amagi hard to replace once you were up and running.

VI. The Business Model & Financial Profile

To understand how Amagi makes money, you have to understand where it sits in the media value chain. Amagi has grown into what it calls a “three-sided marketplace,” linking three groups that normally struggle to coordinate at scale: content providers, distributors, and advertisers.

For content providers, Amagi is the operating system for running live, linear, and on-demand channels in the cloud—and then monetizing them through ad-supported streaming. For distributors, it’s a way to plug into a broad library of channels and manage distribution and engagement efficiently. And for advertisers, it offers a pipeline into connected TV inventory with targeting that’s more like the internet than old-school television, plus real-time performance analytics.

The important part is what this structure creates: momentum. As more content providers come onto the platform, distributors get more reason to show up. More distribution drives more viewership. More viewership attracts more advertisers. More advertising revenue flows back into the ecosystem, encouraging more content investment. It’s a loop that, once it’s working, reinforces itself.

Amagi’s revenue model comes in two main streams:

SaaS Fees: At the core, Amagi sells cloud-based software—cloud playout, live events production, monetization, and OTT video delivery. Customers pay subscription fees to use the platform. It’s essentially rent for the tooling and infrastructure that keep channels running: playout, content management, and distribution.

Advertising Revenue Share: Then there’s the upside layer. Through products like Amagi ADS PLUS, the company takes a cut of the advertising inventory it helps monetize. ADS PLUS is integrated directly with Amagi’s playout and SSAI stack, and it’s designed to connect advertisers with 100-plus premium CTV publishers. It also supports contextual targeting and newer ad formats, giving advertisers programmatic access to specific audiences.

Financially, the picture looks like what you’d expect from a company still leaning into growth: strong top-line expansion, with profitability improving but not yet consistent.

Revenue rose from ₹724 crore in FY2023 to ₹1,223 crore in FY2025, reflecting demand for cloud streaming and FAST and ad tech solutions. Consolidated sales increased 32.2% to ₹1,162.64 crore in FY2025, driven by new customer additions and higher spending from existing customers. Losses also narrowed—operating losses were ₹90.52 crore versus ₹278.39 crore earlier.

For the period ended September 30, 2025, Amagi reported net profit of ₹6.47 crore on revenue of ₹733.93 crore. For FY2024–25, it reported a net loss of ₹68.71 crore on revenue of ₹1,223.31 crore.

Customer breadth has expanded too, and concentration has shifted over time as Amagi built longer-term relationships with major global players. As of September 30, 2025, Amagi served more than 400 content providers, over 350 distributors, and more than 75 advertisers across over 40 countries.

Geographically, the business is still heavily international—especially the U.S. and Europe (including the UK). Those regions contributed over 70% and around 17% of total revenue, respectively, during H1FY26 and FY25. That concentration is a strength in terms of market size, but it also creates exposure: downturns, regulation, currency swings, or demand slowdowns in those regions can hit results.

The unit economics, though, are why this model can be so powerful. Software margins beat satellite leases, and scale compounds. Once Amagi has the integrations in place with a FAST platform like Roku or Samsung TV Plus, adding another channel is much closer to marginal cost—the heavy lifting has already been done. Over time, that can create meaningful operating leverage.

And the retention picture suggests customers don’t just adopt Amagi—they expand. Amagi reported a 127% net retention rate as of July 2021. Anything above 100% means the existing customer base is spending more year after year, which is one of the cleanest signals of real product-market fit—and, at least for a while, pricing power.

VII. Analysis: Powers & Forces

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework:

Switching Costs (High): This is arguably Amagi’s strongest moat. Once a broadcaster threads its workflow—scheduling, rights management, ad insertion, analytics—through Amagi, the platform stops being “a vendor” and starts being “how the channel runs.” Every playlist change, every ad break, every distribution endpoint is coordinated through the system. Swapping it out isn’t a simple re-platforming; it’s a high-stakes operational migration that involves retraining teams, rebuilding processes, and, worst of all in television, risking on-air disruption.

Scale Economies: As Amagi runs more channels, the economics get better in a few reinforcing ways. Compute and bandwidth costs can come down on a per-channel basis as volume grows, the ad inventory pool gets larger (which can improve fill rates and pricing), and R&D gets spread across a wider customer base. Amagi is also an AWS Specialization Partner and AWS Marketplace Seller, which reflects how deeply its offering is tied into hyperscale cloud infrastructure for broadcast and targeted advertising.

Network Effects (Emerging): Amagi’s “three-sided marketplace” hints at a classic flywheel. More content providers bring more distributors. More distribution brings more viewership. More viewership creates more ad opportunities, which draws more advertisers, which can generate more revenue for content providers—bringing in still more content. It’s not the kind of instant, winner-take-all network effect you see in social apps, but it is an ecosystem effect that can strengthen as the platform grows.

Cornered Resource: The founding team is a real differentiator. The same group that built deep wireless infrastructure, then an India-wide ad-tech deployment business, then bet early on cloud playout has shown a rare ability to pivot without breaking. Moving from hardware to cloud, from India-first to global, and from ad insertion as a product to broadcast infrastructure as a platform is not an easily copied capability.

Process Power: Manifest-based playout is a good example of accumulated know-how turning into advantage. It replaces traditional playout servers and automation systems with highly scalable standard web-server architecture, enabling a seamless 24/7 broadcast-style experience across distribution platforms. Amagi’s Emmy recognition for this work is a signal that they didn’t just ship software—they helped define a modern operating model for FAST.

Porter’s Five Forces:

Threat of New Entrants (Medium-High): The technology is hard—broadcast-grade reliability in the cloud is not a weekend project. But the more serious long-term threat is capital and distribution: hyperscalers like AWS, Google Cloud, and Microsoft Azure have the technical capability to push further up the stack. The open question is whether they want the complexity of broadcast as a vertical, or if they’d rather stay the neutral infrastructure layer underneath everyone else.

Power of Suppliers (Low to Medium): Amagi relies heavily on hyperscale cloud infrastructure, including Amazon Web Services and Google Cloud. That dependency gives suppliers leverage in theory. In practice, Amagi is a large customer, and cloud infrastructure has been steadily commoditizing. The platform could also, at least conceptually, shift workloads if pricing or terms became unfavorable—though any such move would be non-trivial.

Power of Buyers (Medium): The biggest media companies have real negotiating power and, in some cases, the resources to build or buy alternatives. But the switching costs cut the other way, and many broadcasters would prefer to spend their attention on content and audience rather than running the plumbing of playout, ad insertion, and distribution.

Threat of Substitutes (Low): The main substitutes are the old world—traditional hardware-based broadcast systems that are expensive and inflexible—or building in-house, which is capital-intensive and pulls focus away from the media company’s core business. For most players, neither option is especially attractive in a market demanding speed, experimentation, and cost discipline.

Competitive Rivalry (Intense but Fragmented): Competition is real and spread across adjacent categories—ad-tech players, broadcast equipment incumbents, and streaming infrastructure specialists. Amagi’s top 12 competitors include VideoAmp, Simulmedia, Viamedia, GlobeCast France, Wurl, Evertz, Yospace, Grass Valley, OTTera, Arkena, INVISION, INC. and Transifex; collectively, they have raised over $1B and employ an estimated 5.4K people. Industry discussions often group Amagi and Wurl as leading providers in this space, and there are neighboring rivalries too—some lists even note that companies competing with Frequency in this market include Amagi and Wurl.

The important point is positioning: Amagi has established leadership in broadcast-grade cloud playout, and it’s become a cornerstone of the global FAST ecosystem. By pairing cloud operations with ad monetization tooling, it has enabled content owners, broadcasters, and platforms to launch and distribute channels globally without building capital-intensive broadcast facilities.

VIII. The Bull & Bear Case

The Bull Case:

The bull thesis starts with a premise that sounds almost too simple: linear TV isn’t dying; it’s being rewritten as software. And if that’s true, then Amagi isn’t just a vendor. It’s trying to become the operating system for how modern television gets made, delivered, and monetized.

The tailwinds are real. The U.S. over-the-top market is projected to keep expanding over the next five years, pushed along by more subscribers, new services, and—crucially—higher prices. When streaming gets more expensive, the industry’s pressure valve is the same place it’s always been: advertising.

That’s why the pivot of the major streamers matters so much. Netflix, Disney+, and HBO Max all launched ad-supported tiers—an about-face from the original “premium means ad-free” story. That shift structurally increases demand for the kind of broadcast-grade ad insertion Amagi sells through THUNDERSTORM: ads stitched into live and linear streams in a way that’s measurable, targetable, and scalable.

FAST strengthens the case even more. Recent industry reports show audience growth in ad-supported streaming and FAST continuing to accelerate, with total hours watched across major free ad-supported services jumping sharply year over year. Consumers like “free and easy.” Advertisers like “big reach with TV impact.” FAST sits right in the overlap—linear’s lean-back behavior, delivered with streaming’s distribution economics. And Amagi sits in the plumbing.

Zooming out, the broader streaming opportunity is still expanding globally, with video streaming projected to grow dramatically from its 2024 base over the rest of the decade. Bulls will argue that in a world where more video is delivered over IP, the value shifts toward the infrastructure layer that can run channels reliably and monetize them efficiently.

And then there’s the narrative advantage: Amagi as part of the “third wave” of Indian tech. The first wave was IT services like Infosys and TCS. The second was consumer internet scale stories like Flipkart. The third is global, product-led SaaS—Zoho, Postman, Freshworks—and, in this framing, Amagi: a company building differentiated infrastructure software in India and selling it to the world.

The Bear Case:

The bear case is just as straightforward: great category, real product, but the ground beneath it could shift.

Commoditization Risk: Cloud playout could become a feature, not a product. As hyperscalers like AWS and Google Cloud expand their media toolkits, the fear is that specialized providers get squeezed on price, and margins compress as the underlying infrastructure becomes more standardized.

Platform Risk: FAST and connected TV are crowded, and the gatekeepers have leverage. If Roku, Amazon, or Samsung decide playout and monetization are strategic enough to own—by building or acquiring—Amagi could lose its role as the neutral “middle layer.” Even without full vertical integration, a more competitive market can mean pricing pressure, higher customer acquisition costs, and harder renewals.

Geographic Concentration: A large portion of Amagi’s revenue comes from the United States. That’s great when the market is growing. It’s a vulnerability if regulation shifts, macro conditions soften, or geopolitical and policy dynamics change in ways that impact advertising, data, or media distribution.

Profitability Path: The company’s profitability profile has been volatile. Profit after tax declined sharply from FY2023 to FY2025, with PAT margins turning negative and return on net worth also negative. Expenses also ran ahead of revenue in FY2025, consistent with a business investing heavily—but it raises the question public-market investors always ask: when does growth translate into durable margins?

Regulatory Complexity: This is global media infrastructure. Data localization rules, advertising standards, and content regulations vary widely and keep changing. Operating from India while serving dozens of markets adds execution risk, especially as regulation becomes more fragmented.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor:

For long-term investors tracking Amagi, three metrics are worth watching because they reveal whether the story is strengthening—or getting squeezed:

-

Net Revenue Retention (NRR): Last reported above 127%, this shows whether customers expand over time. If it trends down, that’s an early signal of churn risk or pricing pressure.

-

Gross Margin Trend: At scale, software businesses should widen margins as fixed costs get spread over more revenue. If gross margin declines, it can point to rising cloud costs or a market that’s turning into a price fight.

-

Customer Concentration in Top 10 Accounts: The more revenue depends on a small set of major broadcasters and platforms, the more negotiating leverage those customers have—and the more a single lost account can sting.

IX. Conclusion: The IPO and What It Represents

Amagi’s IPO was structured as a book-built issue of ₹1,788.62 crore, split between a fresh issue of ₹816 crore and an offer-for-sale of ₹972.62 crore. The company said it planned to use the net proceeds primarily for investment in technology and cloud infrastructure (₹550.06 crore), along with funding inorganic growth through unidentified acquisitions and general corporate purposes.

At these valuations, Amagi was commanding a market capitalization of more than ₹7,800 crore. And that’s what makes this listing stand out: it doesn’t read like a typical “India IPO” story. Amagi is technology-led, SaaS-oriented, and heavily global in where it sells and operates. It sits in a scalable part of the media stack—where cloud-based workflows and programmatic advertising are increasingly the default.

The anchor book signaled real institutional interest. It included domestic mutual funds and global institutions. SBI Mutual Fund, ICICI Prudential Mutual Fund, and HDFC Mutual Fund together took a significant portion of the anchor allocation. Other domestic participants included Birla Mutual Fund, Motilal Oswal Mutual Fund, Tata Mutual Fund, and Franklin Templeton Mutual Fund, among others. On the global side, names in the anchor round included Goldman Sachs, Société Générale, Fidelity, Susquehanna International Group (SIG), Isometry Capital, and New Vernon Capital.

So what does Amagi represent for the Indian technology ecosystem?

It sits at the intersection of a few powerful narratives. First, entrepreneurial persistence: three friends who didn’t split up after an acquisition, but instead took the harder path—through pivots, reinventions, and market cycles. Second, technical ambition: engineers in India building broadcast-grade cloud reliability that major media companies around the world trust with their most visible moments. And third, category creation: Amagi didn’t just benefit from FAST—it helped make FAST operationally possible at scale, at a time when the segment barely existed.

Subramanian frames the ambition plainly: “There is one-tenth or one-hundredth of the opportunity in front of us. We think we would be one the largest media tech companies in the world. We have a fairly good platform and foundation right now. Beyond FAANG, which is the Meta, Apple, Amazon, and Google, we are the largest today,” he said.

That arc—from a niche startup in Bengaluru to a globally recognized media infrastructure company—is the real story the IPO crystallizes.

Whether Amagi ultimately earns its valuation will come down to execution from here: scaling profitably, staying ahead technologically, and defending its position as competition intensifies. But even before the public markets render their verdict, Amagi has already proven something important—that Indian deep-tech companies can build global infrastructure products, not just services, and compete in the highest-stakes parts of the software economy.

X. Sources & Further Reading

Key sources for this analysis include:

- Amagi Media Labs Red Herring Prospectus and other public filings

- Company investor relations materials and annual reports

- Industry research from Comscore, PwC, and Statista on FAST, connected TV, and streaming

- Founder interviews and profiles in YourStory, Inc42, and other industry publications

- National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS) documentation for the Technology & Engineering Emmy Awards

- AWS Partner Network technical documentation on Amagi CLOUDPORT and related cloud architecture

- Analyst reports from JM Financial, Master Capital Services, and other brokerages

- Historical coverage from Variety, Protocol, and Broadcasting & Cable

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music