All Time Plastics: The "Invisible" Giant in Your Kitchen

I. Introduction: The "Hidden Factory" Paradox

Picture yourself wandering through an IKEA in Brooklyn. Or a Tesco in London. Or a Kmart in Sydney.

You reach for a food storage container—BPA-free, with that satisfyingly snappy lid and a kind of premium heft that signals “this isn’t the cheap stuff.” You flip it over to check the label.

Made in India.

There’s a decent chance that container started life on a factory floor in western India—designed, tested, and mass-produced by a family most shoppers have never heard of: the Shahs of Mumbai.

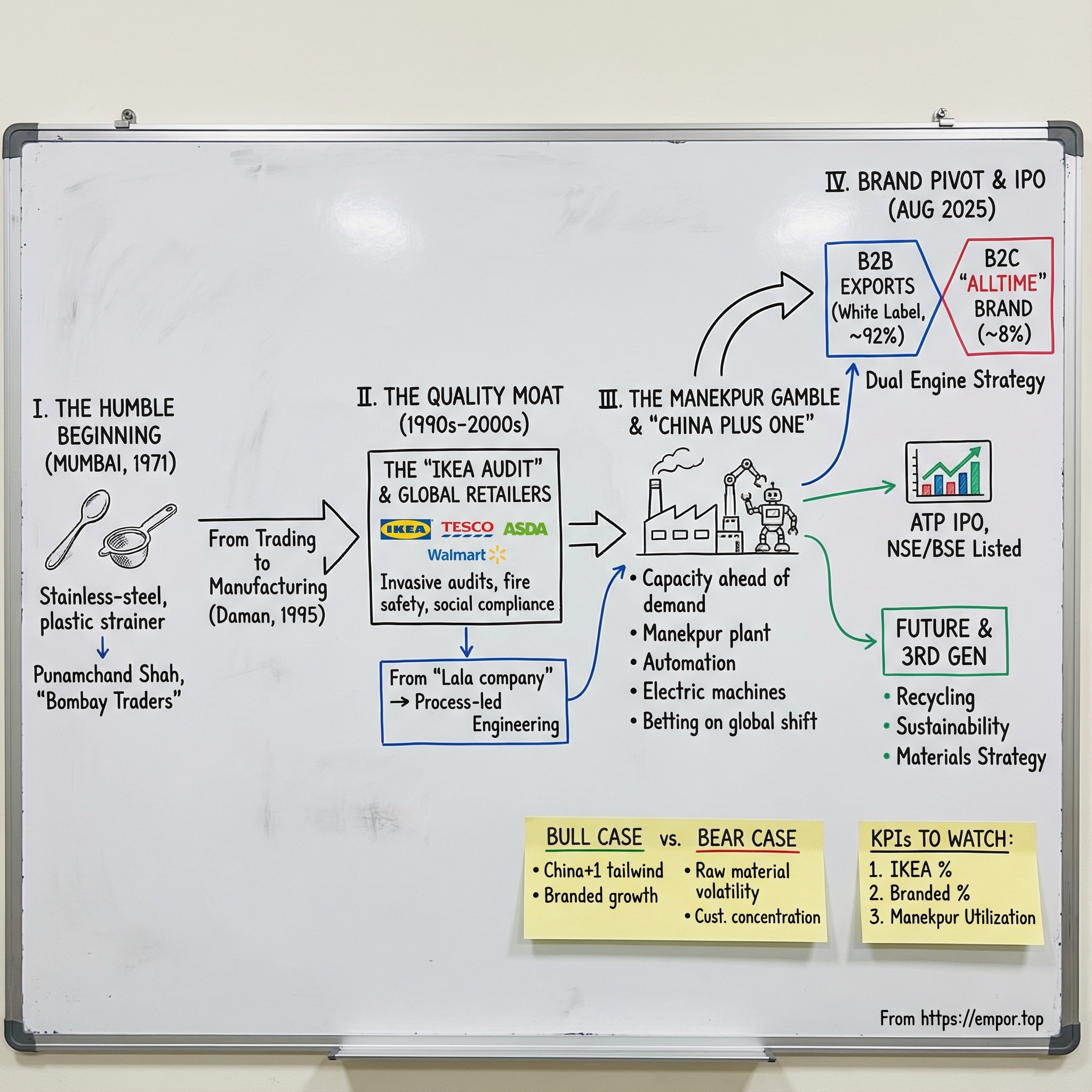

All Time Plastics Limited, founded in 1971, makes plastic houseware products—but mostly not under its own name. Its core business has been B2B, manufacturing for global retailers who sell the products under their own labels. That’s the hidden-factory paradox: millions of households use these products every day, and almost none of those people could tell you who actually made them.

And that’s what makes All Time so interesting. This is a “gradually, then suddenly” story.

For decades, All Time moved steadily—quietly building capabilities, getting better at quality, learning what global customers demanded, and becoming the kind of supplier big retailers can’t afford to take risks without. Then the world’s supply chains cracked open. The US–China trade war and COVID didn’t just disrupt logistics; they rewired procurement strategy. “China Plus One” went from PowerPoint to purchase orders, as multinationals pushed production out of China and into alternative hubs. India, with its manufacturing base, labor pool, and policy tailwinds, became one of the most talked-about destinations for that shift.

Today, the company’s business is still overwhelmingly B2B: nearly 92% of its income comes from contracts with customers like IKEA, Walmart, Asda, Tesco, Michaels, and others. Exports are the backbone—about 85% of revenue comes from selling into 29 countries, with the EU, the UK, and the US driving most of it. All Time isn’t just making containers and houseware; it’s supplying the shelf inventory of some of the biggest retailers on Earth.

Then came the moment that made the “invisible giant” visible—at least to public markets. All Time Plastics’ IPO bidding ran from August 7 to August 11, 2025, with allotment finalized on August 12. The shares listed on the BSE and NSE on August 14, 2025. The debut was strong: the stock opened around a 14% premium on the BSE at ₹314.30, signaling real investor appetite for a scaled, export-oriented Indian manufacturer.

But the reason to study All Time isn’t just a clean listing pop. It’s what the company represents: a business that’s lived through three chapters of Indian manufacturing evolution—starting in the messy, unorganized era; then grinding through the brutal qualification process required to become a trusted global supplier; and now stepping into the hardest chapter of all—trying to build a consumer brand while riding India’s rising domestic consumption.

II. History: From Stainless Steel to "The Plastic Age"

All Time’s story doesn’t start with plastic. It starts with steel—and with a founder who had to earn everything the hard way.

Punamchand Shah’s family had lived in Burma and returned to Gujarat after Independence. Like a lot of families rebuilding from scratch, the next chapter was migration and hustle. Punamchand and his brothers left Gujarat looking for work, and by 1964—after bouncing through odd jobs in Mumbai, Chennai, and Sangli—he made his way back to Mumbai and took a job as a salesman for a cutlery trader.

This wasn’t a silver-spoon origin story. With help from his boss and his own savings, Punamchand raised ₹10,000 and started a small stainless-steel cutlery trading business called Bombay Traders. He bought products from manufacturers and sold them to wholesalers and retailers. In other words: before he ever became a factory owner, he learned the market from the street level—what customers asked for, what moved, what didn’t, and where the margins really were.

That “trader’s eye” mattered when plastics began creeping into Indian households in the 1970s. Bombay Traders didn’t jump overnight from steel to injection molding; it was a gradual pivot—first trading plastic items, then making them. Punamchand could see what was coming. Plastic was lighter than steel, didn’t shatter like glass, and could be shaped into almost anything. It was the future, even if it didn’t look premium yet.

He set up a small unit in 1974, making early products like tea strainers and trays, and sold them himself—commuting from Dadar to Dahanu by local train every day to push goods into the market. That detail tells you something important about this company’s DNA: it was built from the demand side backward. Make something simple, sell it yourself, learn fast, repeat.

The company’s own telling of these early years is heavy on values—honesty, hard work, customer-first thinking, and taking care of the people who worked with them. It also paints Punamchand as a vivid personality: witty, jovial, fearless, someone who built relationships easily and carried that energy into the business. Whether you call it culture or just the way a family operates, those traits became part of the operating system All Time ran on.

Then the second generation arrived.

As the 1980s began, Kailesh Shah joined while still in college at Lala Lajpatrai College of Commerce and Economics. The “office” was a small plastic cutlery workshop in Mumbai. He’d go to college in the morning and head to the unit in the afternoon. Punamchand taught him the fundamentals—then, crucially, gave him room to experiment, make mistakes, and learn.

That style—space to try things, permission to fail small—would become a recurring theme. For a manufacturing business, it’s a surprisingly powerful edge. It creates a culture that’s willing to change processes, test new markets, and invest ahead of certainty.

In the 1990s, as more manufacturers moved to the Union Territory of Daman for its business-friendly environment, the Shah family followed. In 1995, they set up their first factory there. At the time, turnover was around ₹20 lakh—numbers that feel almost quaint next to what the company would later become. But strategically, the Daman move was huge. It was the moment Bombay Traders fully crossed the line from trading to manufacturing at scale.

Around the same period, Kailesh’s brothers—Nilesh and Bhupesh—joined too, and the company started looking beyond India. They began showing up at international trade fairs and exhibitions, including Arabplast in Dubai. Not long after the Daman factory was established, turnover reached about ₹1 crore.

But the bigger story of the 1980s and 1990s wasn’t the growth rate. It was the environment they were growing through.

India’s plastics market was dominated by the unorganized sector—countless small players competing almost entirely on price, often using recycled materials with inconsistent quality and minimal attention to safety standards or design. Plastics weren’t a “brand” category. They were commodities in a race to the bottom.

The Shah brothers made a defining call: don’t fight that war.

Instead, they looked outward—toward export markets where customers cared about consistency, finish, and reliability. Europe, the Middle East, and later the United States weren’t just bigger opportunities. They were better teachers. Those markets would force All Time to upgrade quality, discipline, and processes—setting the stage for the audit-heavy, compliance-driven world that would later become their moat.

III. Inflection Point 1: The "IKEA Audit" & The Quality Moat

The leap from “another Indian plastic manufacturer” to “trusted global supplier” didn’t come from a single lucky break. It came from a long, grinding transformation—one that rewired how the company operated, what it measured, and what it would and wouldn’t compromise on.

All Time has been supplying IKEA for more than 26 years. Tesco International Sourcing for more than 16. Asda for more than 13. Michaels Global Sourcing for more than three. Relationships like that don’t happen because a factory can make a decent container. They happen because the factory can survive the kind of scrutiny that only global retailers can bring—and then keep surviving it, year after year.

Because here’s the part most people miss: an “IKEA audit” isn’t someone checking a few samples and nodding politely.

These audits are invasive by design. They don’t just ask whether the product meets a spec sheet. They look at the entire system that produces the product: fire safety and evacuation readiness, worker wages and conditions, traceability of raw materials, environmental compliance, the rigor of quality-control processes—down to details as mundane as factory lighting. The goal isn’t to catch a defect. It’s to prove the operation is stable, repeatable, and trustworthy.

Passing once is hard. Staying approved through recurring audit cycles—often every couple of years—forces something deeper: you can’t treat quality as a one-time event. You have to institutionalize it.

For the Shahs, that meant more than buying machines or creating binders of procedures. It meant changing the company’s identity—from what Indian business shorthand calls a “Lala company,” driven by instinct and relationships, into a process-led engineering organization where performance could be predicted, tracked, and replicated.

And that shift created their first real moat.

Once a customer like IKEA has spent years qualifying a supplier—auditing plants, testing products, validating systems, integrating that supplier into its supply chain—the cost of switching isn’t just the price per unit. Switching means operational disruption, quality risk, retraining, requalification, and the uncomfortable reality that if the new supplier fails, the retailer owns the consequences on store shelves. Those are switching costs, and they’re a powerful kind of lock-in.

Layered on top of that was a second force: sustainability, increasingly non-negotiable for global retail. All Time pushed recycled sourcing, with 27.21% of raw materials coming from recycled inputs in FY25, up from 18% in FY23. It backed those efforts with certifications like GRS and third-party audits such as Sedex—signals that matter because retailers don’t want promises; they want documentation. The company also began piloting bamboo-based products, with a commercial rollout expected by Q3 FY26. This wasn’t just ethical positioning. It was competitive differentiation in a world where procurement teams are judged on ESG as much as on cost.

The upgrade showed up in the tech stack too. All Time adopted tools like SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) and NX Mold Wizard to improve automation, mould design, and production efficiency. The point wasn’t flashy software. It was control—over design, over repeatability, and over quality at scale.

Of course, there’s a tension here. For investors, the IKEA relationship is both asset and exposure. In FY25, IKEA alone contributed 59% of revenue, and Asda, Michaels, and Tesco added another 19%. That concentration is real risk—losing IKEA would hurt badly. But it also tells you something about what All Time became: retailers don’t route that much volume to a supplier they don’t trust. The concentration is, in a strange way, evidence of how deep the relationship runs.

And it explains why this moat is so underappreciated. Anyone can buy injection molding machines and start making plastic products. All Time itself introduced hundreds of new SKUs every year—598 in FY25, 553 in FY24, and 609 in FY23—showing how fast product development can move once the engine is built. But the harder part isn’t making a container. The harder part is building the systems, certifications, and multi-year reliability that let Walmart or IKEA say: yes, we’ll put this on our shelves worldwide.

That’s what the audits really created. Not paperwork. Permission.

IV. Inflection Point 2: The Manekpur Gamble

If the IKEA qualification years were about laying the foundation, Manekpur was something else entirely: a bet on where the world was heading.

COVID didn’t invent “China Plus One.” But it took what had been a cautious procurement idea and turned it into a board-level mandate. Shipments got stuck. Factories went dark. Geopolitics stopped being background noise. And suddenly, retailers and brands that had relied on China for decades started building a second, and sometimes third, sourcing base.

India was one of the clearest beneficiaries of that shift. Consumerware exports were expected to grow steadily over the coming years, and for a company like All Time—already trained for global audits and already embedded with blue-chip buyers—the question wasn’t whether demand could show up. It was whether they could physically produce enough to keep up.

That’s the defining dilemma in manufacturing: do you build capacity ahead of orders, risking idle assets and heavy fixed costs, or do you wait for demand to become undeniable, risking that your customers move on without you?

All Time chose to build.

The Manekpur plant came online in December 2024 with about 4,000 tonnes per annum of capacity, with plans to scale it to roughly 16,500 tonnes per annum by FY26E and 22,500 tonnes per annum by FY27E as expansion phases kicked in.

Zooming out, the company operated three fully integrated manufacturing facilities—Daman, Silvassa, and Manekpur—with about 33,000 tonnes per annum of installed capacity. The Manekpur ramp would take that to about 55,500 tonnes per annum by FY27. In plain English: almost doubling the factory footprint in a very short window.

Location was a big part of the logic. All three sites sit inside western India’s industrial belt, close to critical logistics and supply infrastructure. Major ports like Nhava Sheva (around 200 km away) and Hazira (around 150 km away) make exports faster and more predictable. Facilities are near ICD Tumb in Vapi, which helps with container handling and cost. And nearby petrochemical plants mean easier access to the raw materials that matter—commodity plastics and recycled polymers. In an export-heavy business, manufacturing is ultimately a logistics game: move inputs in and finished goods out with as little friction as possible.

But the Manekpur story wasn’t just “more space.” It was an upgrade in how the space works.

The company planned to invest proceeds to repay a portion of outstanding borrowings, and also to purchase equipment for Manekpur—specifically including an automated storage and retrieval system. Along with that came the broader shift toward more automation: AS/RS, robotic handling, and modern electric injection molding machines. Across the business, All Time produces over 60 million units annually, and the company positioned its plants in Daman and Silvassa as increasingly automation-driven to improve output and energy efficiency.

Electric injection molding machines are worth pausing on, because they’re not a cosmetic improvement. Compared to older hydraulic machines, they offer higher precision, faster cycle times, lower energy use, and less maintenance. In a category where retailers push relentlessly on price, that kind of operational advantage doesn’t just help this quarter—it compounds.

Still, this was a real swing, and the risk showed up immediately on the balance sheet. Borrowings rose to ₹218.51 crore in FY25 from ₹142.35 crore in FY24. All Time was taking on leverage to build capacity before the orders were fully in hand—essentially wagering that “China Plus One” would persist long enough, and strongly enough, to fill the machines.

The utilization numbers explained why management felt the timing was right. Installed capacity stood at 33,000 tonnes per annum, and capacity utilization was 79.48% in FY25. When you’re already running close to 80%, you’re not building a vanity plant—you’re relieving a bottleneck.

The TSMC analogy (on a dramatically smaller scale, obviously) helps frame the move. TSMC built dominance by investing in capacity ahead of customer commitments, betting that once the capability existed, demand would consolidate around it. Plastic houseware isn’t semiconductors, but the strategic logic rhymes: in manufacturing, capacity often leads demand—because the customer can’t buy what you can’t ship.

For anyone tracking this chapter, the tell won’t be a press release. It’ll be Manekpur’s ramp. If utilization climbs quickly toward the 70–80% range, the gamble looks prescient. If it sits under 50% for long, it signals either demand didn’t arrive as expected—or execution didn’t match ambition.

V. Inflection Point 3: The Brand Pivot & IPO

There’s a tension baked into All Time Plastics’ model that every great OEM eventually runs into: if you’re making products for someone else’s brand, your margins will always have a ceiling—and your customers will always have leverage.

In FY25, IKEA alone contributed 59% of revenue. Add Asda, Michaels, and Tesco, and you’re looking at another 19%. There are no long-term contracts anchoring those relationships, which means concentration risk is real. When one customer is close to 60% of your top line, they don’t just influence pricing—they effectively set it. And in that world, margin expansion only comes from two places: becoming so operationally indispensable that you can negotiate, or building a second engine where you own the brand and the economics.

That’s what makes the next move so important. For most of its life, ATP has been a white-label factory for global retail giants. It does have its own Indian label, “Alltime,” but so far it’s been small—about 7.6% of revenue.

The branded push is an attempt to change that.

The pitch is simple, and it’s hard to argue with. All Time already makes “export quality” products—designed to meet global retailer standards on finish, safety, and repeatability. Meanwhile, Indian consumers have been steadily upgrading: moving away from cheap, inconsistent, unbranded plastic into products that feel more premium and last longer. So why not sell that same export-grade product directly, instead of letting all the consumer margin accrue to someone else?

The company’s strategy has been to position All Time-branded products in the gap between the unorganized sector at the bottom and established brands like Cello—or the legacy positioning that Tupperware once held—at the top. It’s not trying to be the cheapest container on the shelf. It’s trying to be the best value: “global quality,” at a price that feels attainable.

To make that work, distribution matters as much as product. All Time has pushed into modern trade, super distributors, and e-commerce, supplying Indian channels like Vishal MegaMart, Lifestyle, and Zepto. And that last one is telling: quick commerce isn’t just another outlet, it’s a signal that the company understands how fast household buying habits are changing—and how much shelf space is now digital.

Against that backdrop, the IPO in August 2025 wasn’t just a financing event. It was the next step in the company’s transformation.

All Time Plastics’ IPO was a book-built issue totaling ₹400.60 crores, comprising a fresh issue of 1.02 crore shares (₹280.03 crores) and an offer for sale of 0.44 crore shares (₹120.57 crores).

Strategically, it did three things.

First, it gave the company room to breathe after the Manekpur expansion. At the upper band of ₹275, ATP was valued at around ₹1,800 crore, and the fresh proceeds were earmarked primarily for deleveraging and continuing the buildout—about ₹143 crore toward debt reduction, ₹114 crore toward equipment, plus general corporate purposes.

Second, it provided liquidity. The offer-for-sale portion let the Shah brothers monetize a slice of their holdings while still retaining majority control—classic “take a little money off the table, keep the steering wheel” behavior.

Third, it brought visibility and discipline. Public markets don’t just hand you capital; they force reporting cadence, governance structure, and financial transparency. And for global retailers—who are already obsessed with compliance—having a publicly listed supplier can be a trust accelerant.

The listing day suggested investors liked the story. Shares debuted on the NSE at ₹311.30 and on the BSE at ₹314.30—roughly a low-teens premium over the issue price. Not a meme-stock blowoff. A clean signal of demand.

That demand showed up even before the opening bell. All Time raised ₹120 crore from anchor investors ahead of the IPO, allotting more than 43.6 lakh shares at ₹275 each to 12 funds, including Ashoka India Equity Investment Trust and Canara Robeco MF. The presence of established institutional investors—rather than purely speculative hot money—helped reinforce that the market was underwriting fundamentals: a scaled export manufacturer with a credible shot at building a domestic brand on top.

And then there’s the longer arc: the third generation has arrived.

Kailesh’s son, Dhvanit, 24, and Nilesh’s son, Akshay, 26, have joined the business. Dhvanit, as Head of Strategic Business, has talked publicly about where he wants to push next—especially recycling and materials strategy. “There are many aspects that we want to work on, but I am particularly keen on focusing on the recycling space. With the ban on one-time use plastics, it is essential to look for alternatives for the longer-use plastic items as well. Currently, we are using recycled plastic for 15-20 per cent of our production, which we aim to increase in the coming years.”

This is what a healthy generational transition looks like: continuity in manufacturing discipline, with an added sensitivity to the sustainability pressures that will shape who wins the next decade of consumerware.

VI. Competitive Analysis: Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework

To understand how All Time Plastics competes—and why it’s been able to keep winning business in what looks, from the outside, like a commodity category—it helps to run the company through Hamilton Helmer’s “7 Powers” lens. Not “what are they good at,” but what advantages actually endure.

Switching Costs: The Stickiest Moat

This is the big one, and it’s the foundation of the B2B engine.

When a retailer like IKEA or Tesco qualifies a supplier, they’re not just approving a product. They’re approving an entire system: the factory, the process controls, the compliance stack, the audit history, the ability to repeat quality at scale. That qualification isn’t a checkbox—it’s a project.

And the switching costs don’t end there. The molds for specific products are often designed and held by All Time. If a buyer wants to move a product line to a new supplier, they’re looking at re-tooling molds, re-validating output, re-auditing the new plant’s social and environmental compliance, and redoing the internal approvals that keep procurement teams out of trouble. In practice, that can take roughly 18 to 24 months—and it introduces the one thing global retailers hate most: downside risk on store shelves.

That’s why relationship length matters here. All Time has supplied IKEA for 27+ years, Tesco for about 17+, Asda for about 14+, and Michaels for about 4+. You don’t get multi-decade continuity in a “plastic box” category unless you’re doing something that’s painful to replace.

Cornered Resource: Trust as an Asset

In household products—especially anything that touches food—trust isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the admission ticket.

All Time has built a track record that can’t be shortcut: delivering consistent quality over decades, meeting ESG expectations, and behaving like a partner that won’t create reputational landmines. That includes the kind of trust that’s rarely written down but always priced in—things like respecting customer designs and not playing games with materials.

Certifications like GRS, along with third-party assessments like Sedex audits, aren’t just badges. They’re portable proof. They tell a global buyer, “this supplier has been through the process, repeatedly, and held up.” For a new competitor, replicating that trust takes years, not months.

Process Power: Automation as Differentiation

All Time’s operational edge isn’t just that it has machines. It’s that it’s been building a manufacturing system designed for repeatability: robotics, automation, integrated ERP, and modern all-electric injection moulding machines imported from Japan.

That matters because most competition in Indian houseware historically came from the unorganized sector—small operators who can be nimble on price, but can’t reliably hit tight tolerances, run consistent batches, or document quality the way global retailers require.

A plant with 115+ modern injection molding machines, automated warehousing, and digitized process control is playing a different game than a traditional shop-floor setup. That’s process power: not a single innovation, but a way of operating that compounds over time.

Scale Economies: Bulk Purchasing Advantage

Scale shows up most clearly in raw materials. About 65% of All Time’s inputs are sourced domestically, with the rest imported. The company is also meaningfully concentrated with its largest suppliers—top suppliers account for 73% of raw material purchases—which is something to watch.

But scale cuts the other way too. With installed capacity of about 33,000 tonnes per annum—and plans that take it to roughly 55,500+ tonnes per annum—All Time can buy polypropylene, polyethylene, and recycled polymers at volumes that smaller manufacturers simply can’t. In a world where polymer prices swing with crude oil, purchasing power doesn’t eliminate volatility, but it can soften the blows and improve competitiveness at the margin.

What They Don’t Have: Brand Power (Yet)

Here’s the missing power—and it’s the hardest one to manufacture.

All Time is a trusted name to procurement teams, but not yet to consumers. Its in-house “Alltime” brand exists and has distribution in India, but it contributes only about 7.6% of revenue. Turning an OEM reputation into consumer mindshare takes time, marketing investment, and distribution muscle—and it means competing with brands like Cello that have spent decades earning shelf space and recognition.

So, as of this chapter in the story, All Time’s advantages are overwhelmingly industrial: switching costs, trust, process, and scale. The open question is whether it can add the fifth one that changes the whole margin structure: true brand power.

VII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Medium-Low

If you define the business as “making plastic products with injection molding,” the door looks wide open. Machines can be bought, supervisors can be hired, and a factory can start shipping basic output surprisingly quickly.

But if you define the real business as “being trusted to supply IKEA or Walmart at global scale,” the door narrows fast.

Becoming an approved supplier to those retailers is less like winning a one-time order and more like clearing a multi-year obstacle course: audits, material traceability, social compliance, repeatable quality, and the boring-but-decisive proof that you can run the same play every day without surprises. That qualification process functions like a regulatory barrier, and it’s why experience matters here. All Time has spent decades building that operating system, and by FY23 it was the second-largest B2B plastic consumerware manufacturer in India by revenue.

On the domestic branded side, entry barriers are lower—any manufacturer can print a logo and list online. The real walls there are distribution and marketing: getting shelf space, staying in stock, and earning consumer trust.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: High (but mitigated)

This is the structural tension at the heart of All Time’s model. In FY25, IKEA contributed 59% of revenue. When one customer is that dominant, pricing conversations don’t happen on equal footing.

All Time’s response is straightforward: reduce dependency by widening the customer base and, more importantly, by growing the part of the business where it can set its own prices. In FY25, white-label products were about 91.66% of revenue, while branded products were 7.56%. If that mix shifts meaningfully over time, buyer power comes down—not because IKEA gets nicer, but because All Time gains alternatives.

Threat of Substitutes: Medium

For food storage and houseware, plastic isn’t the only option. Glass and steel are long-standing substitutes, and bamboo-based products are increasingly positioned as the “planet-friendlier” alternative.

All Time has clearly seen this coming. In FY25, it acquired All Time Bamboo Private Limited as a subsidiary—an explicit hedge against tightening regulation and rising anti-plastic sentiment.

Market data points in the same direction. An IMARC study estimated India’s bamboo products market at INR 2,319.1 million in 2024, with mid-single-digit growth expected over the coming years.

Still, plastic keeps winning a lot of real-world use cases because it’s light, durable, affordable, and incredibly flexible in design. The bigger substitution threat isn’t that consumers suddenly stop liking plastic. It’s that regulators change the rules—single-use bans, recycled-content requirements, and compliance standards that reshape what’s viable to sell.

Supplier Power: Low

All Time’s key inputs—plastic polymers—are global commodities. Prices can swing with crude oil, but supply is broad, and no single supplier holds a chokehold on the market.

In FY25, around 65% of raw materials were procured domestically, with the rest imported. That split gives them sourcing flexibility and helps avoid over-reliance on any single geography.

Competitive Rivalry: High

This is a crowded battlefield with multiple kinds of competitors.

On the branded domestic side, Cello World is the obvious heavyweight: scale, distribution, and consumer recognition. On the export and engineering end, players like Shaily Engineering compete for global business and technical credibility—Shaily’s own story is a reminder of how far a focused injection-molding player can scale, from a tiny start to becoming a major exporter and a listed company.

Then there’s the constant pressure from below: the unorganized sector fighting on price in value segments. And from outside India, Chinese manufacturers still loom large, with scale and cost advantages—even if “China Plus One” has shifted some incremental orders elsewhere.

The takeaway is that rivalry is intense, but it isn’t a single rivalry. It’s a multi-front fight: brand versus brand in India, supplier versus supplier in exports, and organized manufacturing versus unorganized pricing pressure at the bottom end.

VIII. The Playbook: Lessons for Builders

Lesson 1: Quality as a Moat

In commodity businesses, the default play is to get cheaper until you can’t breathe. All Time took a different route: it got more dependable until customers stopped wanting to risk anyone else.

That distinction sounds small, but it’s the whole game. Building quality systems, earning certifications, and surviving relentless audits is slow, expensive, and often thankless work. Plenty of competitors chose the easier-looking option: win orders on price and figure out the rest later.

But “cheapest” resets every quarter. Reliability, proven over years, turns into something much rarer: trust you can’t quickly copy. And once a global retailer has built its supply chain around you—your processes, your audit history, your tooling, your consistency—that trust becomes switching costs. That’s how a plastic container stops being a commodity and starts being a relationship.

Lesson 2: The White Label to Brand Bridge

The hardest jump in manufacturing isn’t scaling a factory. It’s crossing the invisible line from “we make it for them” to “we sell it as us.”

All Time is trying to do exactly that, using the cash flow from its steady, unglamorous B2B engine to bankroll the uncertain, high-upside B2C bet. It’s a familiar pattern in other industries: Foxconn building for Apple while flirting with its own branded products; Taiwanese contract manufacturers in textiles launching labels; Anker going from anonymous Amazon listings to a real consumer name.

The ingredients are straightforward, but the execution is brutal. You need product quality that matches or beats incumbents (All Time has that). You need pricing that makes the trade-up feel obvious (they’re aiming for that). And then you hit the wall that stops most OEMs: distribution. Manufacturing excellence doesn’t automatically buy you shelf space, mindshare, or repeat purchases. That part has to be built almost from scratch.

Lesson 3: Manufacturing is Sexy Again

For a long time, “manufacturing” carried the wrong image—dirty, low-tech, and stuck in the past. Manekpur points to a newer story: factories that look less like workshops and more like engineered systems.

All Time has leaned hard into that vision, emphasizing robotics, automation, and modern all-electric injection moulding machines imported from Japan. This isn’t just about speed or precision—though it helps with both. It affects who wants to work there, how global customers perceive the operation, and how credible the company looks as ESG scrutiny tightens.

The broader narrative is changing. Manufacturing is becoming modern again, and the companies that invest early in cleaner, more automated, more auditable production are the ones most likely to win as the world reshuffles supply chains.

IX. Bull Case vs. Bear Case: The Investor Perspective

The Bear Case

All Time’s story is compelling. But it isn’t bulletproof. A few very real risks could break the thesis:

Raw Material Volatility: This business runs on polymers, and polymers run on crude. If oil stays high for a long stretch, margins get squeezed fast. And because All Time sells into powerful global buyers, it can’t always pass those cost increases through—especially on existing arrangements where pricing is effectively set.

Regulatory Risk: The world’s tolerance for plastic—especially in Europe—keeps shrinking. The EU has already restricted certain categories, and the direction of travel is clear. If regulation tightens faster than All Time can shift volume into recycled-content products or alternatives like bamboo, it could lose entire pockets of demand.

Customer Concentration: In FY25, IKEA was 59% of revenue. That’s not just “a big customer,” that’s the business’s center of gravity. If IKEA decides to diversify suppliers, or if nearshoring pulls volume closer to Europe, or if a quality slip damages trust, the impact wouldn’t be subtle.

Brand Failure: The branded India business is still early. Turning an OEM into a consumer name takes time and money, and marketing spend doesn’t come with guaranteed payoff. Meanwhile, incumbents like Cello and Milton aren’t standing still—they have years of distribution muscle and consumer habit on their side.

Execution Risk: Manekpur is a huge operational step-up. More capacity is only an advantage if you can ramp it smoothly. If utilization stays low for too long, or if the facility hits quality issues during scale-up, the debt taken to build it stops looking like a growth lever and starts looking like a weight.

The Bull Case

The upside scenario is that All Time becomes exactly what its best customers already treat it as: the default factory behind global homeware shelves—while also building a meaningful consumer brand in India.

China Plus One Tailwind: India’s consumerware exports are expected to grow steadily, with forecasts around a 5.2% CAGR. If global retailers keep shifting supply chains away from China and into India, All Time is one of the few scaled, audit-ready suppliers with the capacity plan to catch that wave.

Dual Engine Revenue Model: This is the dream mix. B2B exports provide stability and predictability; B2C branded products offer the potential for better margins and more control over pricing. If the branded share grows materially, the entire quality of the business changes.

Sustainability Leadership: All Time has already pushed recycled content, sourcing 27.21% of raw materials from recycled inputs in FY25. As large retailers get squeezed harder on ESG reporting, suppliers that can document sustainable sourcing and repeatable compliance become more valuable—not less.

Capacity Advantage: In FY25, the company had about 33,000 MTPA of installed capacity and ran at roughly 79% utilization. The plan is to expand aggressively, with the roadmap pointing to a much larger footprint by FY28. If All Time can scale capacity without losing utilization discipline, growth doesn’t have to come from “winning new logos.” It can come from simply shipping more to customers who already trust them.

Third Generation Innovation: Dhvanit and Akshay Shah’s involvement adds a forward-looking edge—especially around recycling and sustainability. If regulation and consumer preferences keep moving in that direction, having leadership focused on materials strategy could become a competitive advantage, not just a nice narrative.

X. Key Performance Indicators to Watch

If you want to follow All Time Plastics like an operator—not just read quarterly headlines—there are three numbers that will tell you whether the strategy is working, in real time.

1. Export Revenue Concentration (IKEA as % of Total Revenue)

In FY25, IKEA accounted for 59% of revenue. Over time, you want that share to come down—not because IKEA should get smaller, but because the rest of the customer roster should grow faster. If concentration declines while IKEA revenue stays steady or rises, that’s diversification done right. If it creeps up, it’s a warning sign: the business is becoming more dependent on a single buyer with enormous pricing power.

2. Branded Products as % of Total Revenue

Branded “Alltime” products were about 7.6% of revenue in FY25. This is the company’s margin upside and its path to owning more of the value chain. If that share starts climbing meaningfully while the export engine stays intact, it’s evidence the brand pivot is taking hold. If it stays stuck in single digits, it likely means the hardest part—winning distribution and repeat consumer purchase—isn’t breaking through.

3. Capacity Utilization at the Manekpur Facility

Manekpur is the physical expression of the bet: build ahead of demand and ride “China Plus One.” The cleanest way to judge whether that bet was sized correctly is utilization as the plant ramps. Healthy utilization as capacity comes online suggests the expansion is being absorbed by real orders. Weak utilization for an extended stretch suggests the opposite: either the market didn’t show up as expected, or execution didn’t convert demand into throughput.

XI. Conclusion

All Time Plastics is a certain kind of business story. Not the flashy unicorn that lives on headlines, but the patient builder that compounds—slowly, methodically, and then all at once.

The Shah family didn’t start with a grand plan to “disrupt” housewares. They started with a trader’s instinct: understand what the market wants, deliver it reliably, and keep raising the bar. That mindset—paired with a culture built around honesty, hard work, and putting the customer first—pushed the company from Punamchand Shah’s early ₹10,000 stainless-steel trading hustle to a publicly listed manufacturer with roughly ₹560 crore in revenue.

But the number isn’t the point. The point is what they built to earn it: a manufacturing platform that global retailers trust, quality systems that can survive relentless audits, and operating discipline strong enough to scale across decades and generations.

The hard part now is that the next chapter asks for different muscles. The risks are real and they’re not theoretical: customer concentration, the grind of building a consumer brand in India, the execution complexity of ramping Manekpur, and a global backdrop that’s increasingly skeptical of plastic as a category. The advantage All Time carries into that fight is also real: relationships that are painful to replace, process power that most competitors can’t replicate quickly, and a playbook that has already worked once—upgrade, comply, earn trust, and then scale.

So the verdict isn’t in yet. It’ll be written over the next decade. Does the branded business reach escape velocity, or does it stay a side project? Does “China Plus One” turn into sustained demand, or just a temporary rebalancing? Can the third generation push harder on recycling and materials strategy without giving up profitability?

Those are open questions. What isn’t open is what All Time has already proven: in a world that often undervalues “boring” manufacturing, this company has made durability a strategy.

And the next time you snap a lid shut on an IKEA or Tesco container, it’s worth pausing on the invisible journey behind it—out of western India’s industrial corridor, through compliance and quality systems designed for the world’s strictest buyers, across oceans into distribution networks that can’t tolerate failure. That journey exists because a family kept choosing reliability over expedience, quality over price, and long-term relationships over short-term wins.

In an age obsessed with reinvention, there’s something quietly powerful about that.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music