Ferrari: The Eternal Paradox of Exclusivity and Growth

I. Introduction: The Puzzle of the Prancing Horse

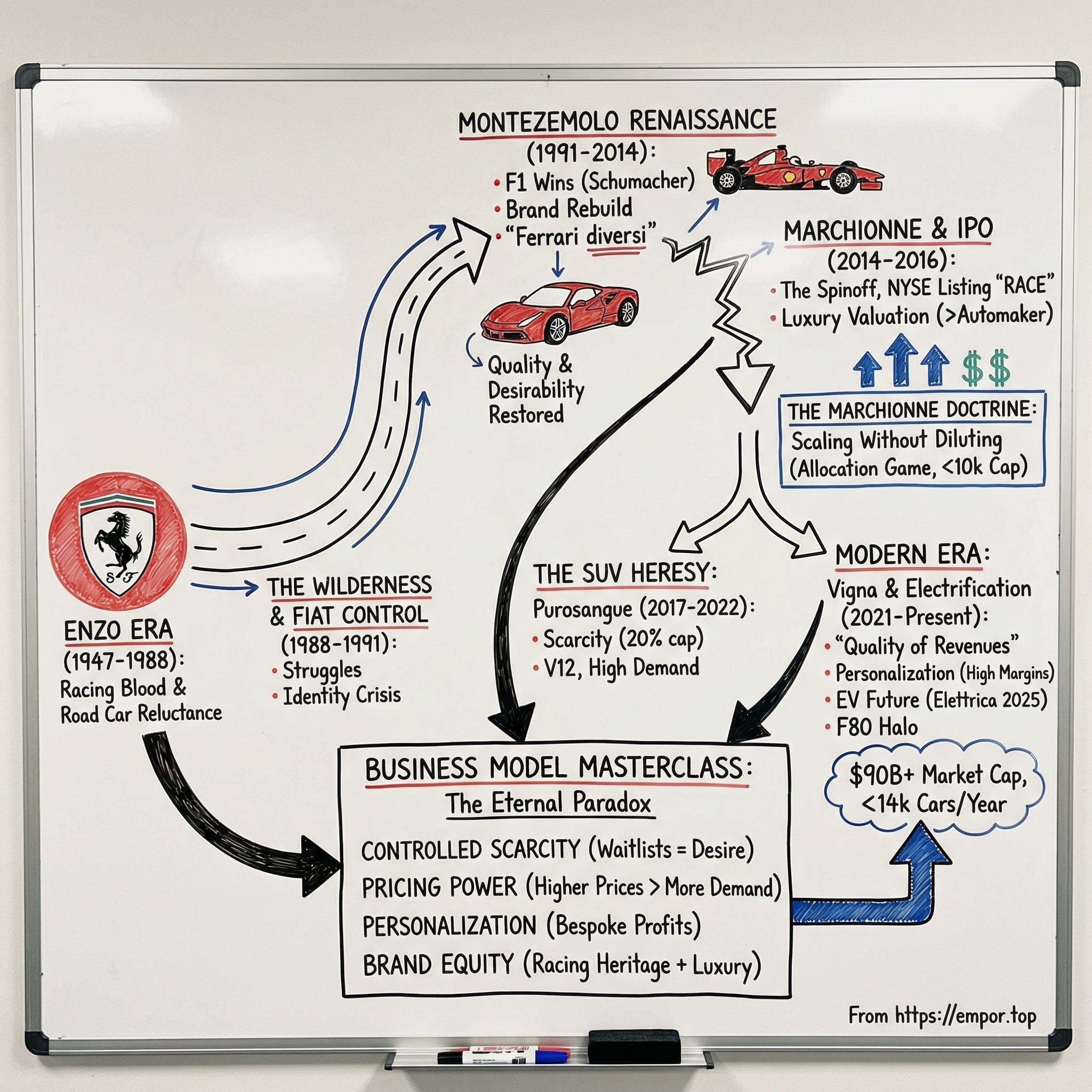

Picture this: a company that sells fewer than 14,000 cars a year—about what Toyota can build in a single day—yet commands a market capitalization brushing $90 billion. As of January 2026, Ferrari’s market cap sat around $91 billion, making it worth more than Ford and General Motors combined. The ticker symbol says it all: RACE.

That’s the Ferrari paradox. How does a business that intentionally holds back supply, keeps waiting lists long, and turns away plenty of willing buyers still produce double-digit revenue growth? How does a company founded to pay for racing become the most valuable automotive brand on Earth? And the question that hangs over everything: can you scale exclusivity without shattering it?

Ferrari is one of the most recognizable luxury brands on the planet. A Ferrari isn’t just a car. It’s a shorthand for rarity, Formula One-bred performance, and Italian flair—three pillars the company protects with almost religious discipline.

And the economics are just as strange as the mythology. In 2024, Ferrari shipped 13,752 cars, barely more than the year before. But the business grew anyway, powered not by volume, but by a luxury playbook: richer model mix, relentless personalization, and careful geographic allocation. That year, the average selling price topped EUR 480,000, and more than 70% of cars went to existing Ferrari clients.

This is the story of how a stubborn racing man from Modena built an automotive religion—and how the people who followed have tried to keep it holy while the world demanded it become bigger: scarcity and growth, heritage and change, Italian soul and Wall Street expectations.

II. The Enzo Era: Racing Blood and Road Car Reluctance (1947–1988)

Ferrari’s origin story reads less like a business biography and more like an opera—big emotions, bigger ambition, and a soundtrack of engines at full song.

Enzo Anselmo Giuseppe Maria Ferrari was born in Modena, Italy, on February 18, 1898. Officially, though, his birth certificate says February 20. A heavy snow kept his father, Alfredo, from registering the birth for two days. The family lived next to the mechanical workshop Alfredo ran while working for the nearby railways. Enzo didn’t follow a polished, academic path. He gravitated to the workshop—hands, tools, machines. For a while, his dreams weren’t even strictly automotive. He flirted with the idea of becoming an operetta tenor, a sports journalist, or a racing driver.

The moment that locked in the last one came in 1908. At ten years old, Enzo watched Felice Nazzaro win at the Circuito di Bologna. The sight of cars charging through dust and noise didn’t just entertain him—it set his life’s direction. He would spend the next eight decades trying to recreate that feeling.

Then reality hit. Enzo served in World War I, but in 1918 he was discharged after becoming gravely ill during the flu pandemic. The war ended; the losses didn’t. His father and older brother, Alfredo Jr., had already died from the flu in 1916. By twenty, Enzo was essentially alone—armed with mechanical instinct and an obsession with speed.

After the war, he found work as a test driver for a small automobile company in Milan. In 1920, he began driving for Alfa Romeo. And in 1929, back in Modena, he founded Scuderia Ferrari—a racing team that prepared Alfa Romeo race cars. Scuderia literally means “stable” in Italian, a fitting word for what would become the world’s most famous automotive “thoroughbred.”

Enzo won his first Grand Prix in 1923 in Ravenna on the Savio Circuit. The following year was his best season, with three wins. But the sport he loved kept taking people from him. The deaths of close friends Ugo Sivocci in 1923 and Antonio Ascari in 1925 shook him deeply. Racing continued, but his heart wasn’t in it the same way.

That 1923 win also delivered one of the central props in the Ferrari myth. After the race, Enzo met Count Baracca, father of World War I flying ace Francesco Baracca. According to Enzo’s own account, Baracca’s mother, Paolina, suggested he paint Francesco’s emblem—a prancing horse—on his cars. “It will bring you good fortune,” she said. The horse would become one of the most valuable symbols in global business.

In 1932, Enzo’s son Alfredo—nicknamed Dino—was born. Around that time, Enzo stepped away from driving and focused on building teams. Scuderia Ferrari became a high-performing racing operation, including superstar drivers like Giuseppe Campari and Tazio Nuvolari, effectively acting as Alfa Romeo’s racing division.

But success didn’t make the relationship easier. By 1937, Alfa Romeo bought out most of Scuderia Ferrari to pull racing fully in-house, keeping Enzo on as an adviser. Two years later, in 1939, they split. Alfa called it a “mutual agreement.” Enzo later said he’d been pushed out.

That break became the crucible. A non-compete clause prevented him from racing under his own name for four years, so he founded Auto Avio Costruzioni in 1939. When the restrictions lifted, he went to Maranello—and in 1947 he founded the company that would carry his name: Ferrari.

To understand Ferrari as a business, you have to understand Enzo’s worldview. He wasn’t a car-company man who happened to race. He was a racing man who tolerated road cars because they paid for racing. He viewed production cars as necessary evils, a way to fund the thing that mattered. He insisted on making “one car less than the market demands.” It wasn’t a clever positioning statement. It was genuine indifference to commercial glory. And weirdly, that authenticity became the brand’s moat.

The 1950s and 1960s cemented Ferrari’s motorsport stature, but financially the company lived on a knife edge. Trophies didn’t automatically translate into cash. In 1963, Ford made a serious attempt to buy Ferrari. Enzo rejected an $18 million offer because Ford wouldn’t let him retain full, independent control of the racing division. The rejection triggered one of the most famous corporate grudges in history: Ford built the GT40 to beat Ferrari at Le Mans—and succeeded, winning four straight from 1966 to 1969.

Ferrari still needed stability. In 1969, Enzo sold 50 percent of the company to Fiat. He stepped down as director of the production-car division, but the agreement preserved what he cared about most: Enzo remained fully in charge of Ferrari’s racing programs. Fiat also paid royalties for the use of Ferrari’s facilities.

While the business battled cycles and cash flow, Enzo’s personal life carried its own weight. Dino died of muscular dystrophy in 1956 at 24 years old. Enzo was devastated. His marriage unraveled. He withdrew into the factory, living in a small apartment there and working constantly—no vacations, no real separation between life and the company. He wore sunglasses as a ritual of mourning for his son.

There was also a family secret. Enzo had a second son, Piero, born in 1945 to Lina Lardi. Because divorce was illegal in Italy until 1970, Enzo could not formally recognize Piero while his wife, Laura, was alive. Piero’s existence was kept to a small circle of confidants. After Laura’s death in 1978, Enzo adopted him. Piero took the name Piero Lardi Ferrari. He would later become vice chairman and own 10% of the company.

On track, the results matched the legend. During Enzo’s lifetime, Ferrari won nine World Drivers’ Championships and eight World Constructors’ Championships in Formula One. From 1948 to 1988, Ferrari cars won over 5,000 races and earned 25 world titles.

Enzo lived long enough to see the launch of the Ferrari F40, created as a symbol of the company’s achievements over forty years. He died on August 14, 1988, at age 90. Weeks later, at the Italian Grand Prix, Ferrari finished 1–2—the only race McLaren didn’t win that season. It felt like a final curtain call: the old man gone, the red cars still standing on top.

III. The Wilderness Years and FIAT Control (1988–1991)

When Enzo Ferrari died in August 1988, he didn’t just leave behind a racing legacy. He left behind a vacuum—and Ferrari wasn’t built for life without him.

That same year, Fiat raised its stake to 90%, taking near-total control. The remaining 10% stayed with Enzo’s son, Piero Ferrari. But ownership is not the same thing as direction. Fiat could hold the keys and still not know how to drive the machine.

And almost immediately, the jewel in Fiat’s crown started to look less like a jewel. On track, Ferrari had not won a Formula One drivers’ championship since 1979. Williams and McLaren were setting the pace; the Scuderia was reduced to chasing. Off track, the road-car business was even shakier—unprofitable, inefficient, and sliding toward the edge of bankruptcy by the end of the 1980s.

The crisis wasn’t just financial. It was existential. What is Ferrari without Enzo?

For sixty years, the company had been inseparable from its founder’s personality—his feuds, his preferences, his iron will. He made the big calls. He hired and fired on instinct. He held the whole place together through sheer force of obsession. Without him, Ferrari wasn’t a modern organization. It was a collection of fiefdoms that had relied on one man as the operating system.

By the early 1990s, the problems were everywhere at once. The road cars of the period—especially the 348—were widely criticized for mediocre quality and uninspiring performance. In Formula 1, Ferrari had become an also-ran, consistently outmanaged and outpaced by the better-funded, better-drilled British teams.

Even the season results told the story. Jean Alesi finished seventh with just 21 points. Ivan Capelli dropped out of almost all the races. Meanwhile, on the road-car side, production drifted beyond demand, the organization carried redundancy, and quality complaints piled up—exactly the kind of slippage Ferrari could not afford, because the brand’s entire power came from being wanted more than it could be had.

Fiat’s control raised a question that would keep coming back in Ferrari’s story: can a company built on racing purity and scarcity survive inside a mass-market conglomerate? Fiat understood Ferrari’s symbolic value. But its instincts—volume, efficiency, scale—ran against the grain of everything Enzo had engineered into the brand.

Ferrari didn’t need another caretaker. It needed someone who could restore sporting credibility, fix the business, and still preserve the hard-to-define essence that made a Ferrari feel like a Ferrari.

IV. The Montezemolo Renaissance (1991–2014)

In November 1991, Fiat chairman Gianni Agnelli made his move. He appointed Luca di Montezemolo president of Ferrari—a company that, since Enzo’s death, had been drifting: messy on the inside, losing on the track, and increasingly unworthy of the badge on the hood.

The pick felt both surprising and obvious. Montezemolo came from an aristocratic Piedmontese family with deep connections to the Agnellis. His father, Massimo, was close with Gianni Agnelli. But Montezemolo wasn’t being handed a ceremonial title. He was being sent to rescue the family’s crown jewel.

And unlike most turnaround CEOs, Montezemolo already knew Ferrari’s bloodstream.

Back in 1973, Enzo Ferrari personally invited him to Maranello as an assistant. A year later he became sporting director of the Scuderia, and during his watch Ferrari won Formula One world championships with Niki Lauda in 1975 and 1977. He then rose inside Fiat—first running its racing activities, then taking senior management roles through the late 1970s and 1980s, including stints at Cinzano and the publishing group Itedi. In 1985, he took on a different kind of race: running the organizing committee for the 1990 World Cup in Italy, a massive logistical undertaking that tested his ability to execute at scale.

Now Agnelli called him back. Montezemolo arrived with a simple personal mission: make Ferrari win again.

He started in Formula One by reshaping the operation—bringing in Lauda as a consultant and elevating Claudio Lombardi to team manager. But the bigger challenge was that Ferrari didn’t just need better results. It needed to feel like Ferrari again.

Because when Montezemolo got to Maranello, the road cars had slipped. The 348 in particular had become a symbol of the malaise: quality issues, dynamics that didn’t inspire, and a sense that the magic had dulled. Montezemolo didn’t need market research to see it—he owned one, and he hated it. He ordered a major rethink that eventually produced the F355 in 1994, a car that landed as a clear statement: Ferrari was back to building machines people lusted after for the right reasons.

What he understood—maybe more clearly than anyone inside Fiat—was that Ferrari wasn’t merely a manufacturer. It was a brand with mythology. A lifestyle. For some customers, basically a faith. His guiding idea became “Ferrari diversi per Ferraristi diversi”: different Ferraris for different Ferrari people. Not more Ferraris for more people—different, better Ferraris for the right people. It would take years to fully realize, but it set the direction.

On track, the rebuild required something close to a talent raid. Montezemolo hired Jean Todt from Peugeot Sport in 1993. In 1995, he landed the biggest prize: double world champion Michael Schumacher from Benetton. Then, in 1997, two more pillars arrived from that same Benetton orbit—Ross Brawn and Rory Byrne.

The payoff came in 2000. Ferrari and Schumacher won both the Drivers’ and Constructors’ Championships, and then they kept winning—stacking titles from 2001 through 2004 and turning the Scuderia into the defining team of the era.

Meanwhile, the road-car business recovered too. Ferrari more than doubled global sales from the early 1990s—starting from a base of 3,377 units in 1992—but Montezemolo insisted the growth didn’t come from flooding the market. As he put it, the company expanded by widening the market it played in, not by turning the volume knob in places where Ferrari was already established.

He also cleaned up the economics. Over the 1990s he pulled the road-car business out of heavy debt and back into profit. When Ferrari acquired Maserati in 1997, Montezemolo took on the presidency there too, holding the role until 2005.

But the most important part of his playbook wasn’t a single hire or a single model. It was discipline.

Fiat pushed, more than once, for higher production. Montezemolo refused. He believed scarcity wasn’t a marketing tactic; it was the product. “I resisted because it would have been a huge mistake,” he said. At the time, he even described Sergio Marchionne—then rising inside the Fiat group—as someone who shared the instinct to protect Ferrari’s exclusivity.

That alignment wouldn’t last.

V. The Power Struggle: Marchionne vs. Montezemolo (2010–2014)

By 2010, Ferrari had been remade. Under Montezemolo, the team had returned to the top of Formula One, the road cars were desirable again, and the brand had evolved from “great Italian sports-car maker” into something closer to a global luxury house. It looked like the turnaround was complete.

But inside the Fiat orbit, a new problem emerged: Ferrari’s success made it too valuable to leave alone.

Montezemolo’s own responsibilities had expanded long before the break became public. On 27 May 2004, he became president of Confindustria, Italy’s main business lobby. Days later, after Umberto Agnelli’s death, he was elected chairman of Fiat S.p.A.—Ferrari’s parent company. Now he wasn’t just the guardian of Maranello’s mystique. He was also expected to help maximize value for Fiat’s shareholders.

Those two jobs don’t naturally coexist. Ferrari’s power comes from restraint. Conglomerates, especially in a turnaround, tend to want leverage.

That’s where Sergio Marchionne entered the story. The Canadian-Italian executive had engineered Fiat’s revival and spearheaded the Chrysler deal. Marchionne saw businesses as portfolios of assets—and Ferrari, sitting inside a mass-market car company, looked like the most mispriced asset of them all.

The clash wasn’t personal at first. It was philosophical.

Montezemolo’s view was simple: cap production at roughly 7,000 cars a year and protect exclusivity at all costs. Ferrari should remain slightly out of reach, always. Marchionne saw something else: a company deliberately refusing demand, leaving growth—and therefore value—on the table.

At the same time, Ferrari’s on-track aura was fading, which made the internal debate harder to contain. The Schumacher era was over. The Scuderia hadn’t won a Drivers’ Championship since Kimi Räikkönen in 2007, and each season without a title weakened Montezemolo’s position as the man who “made Ferrari win again.”

By September 2014, the tension finally snapped into the open. On 10 September 2014, Montezemolo resigned as president and chairman of Ferrari. Marchionne, already CEO of Fiat Chrysler, took his place.

Montezemolo had led Ferrari for 23 years—an entire generation in automotive time. His departure didn’t just close a chapter. It ended an era: the longest, most consequential stretch of leadership Ferrari had seen since Enzo himself.

And it set up the next, far riskier question. If Montezemolo’s discipline had turned Ferrari into a modern luxury icon, could Marchionne push for more without breaking the spell?

VI. The IPO Gambit and Spin-off Strategy (2014–2016)

Sergio Marchionne wasted no time. Within weeks of taking control, he announced what many people inside the industry considered unthinkable: Ferrari would be cut loose from Fiat and turned into an independent, publicly traded company.

By October 20, 2015—the day before Ferrari’s first day of trading—Marchionne had spent a year preparing the market for what was coming. Ferrari N.V. would list on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker RACE, with an eventual listing in Milan. It was a clean, symbolic break: Maranello, but with a Wall Street price tag.

On paper, the rationale was straightforward. Fiat Chrysler Automobiles needed cash. The IPO and spin-off were designed to help reduce FCA’s debt and help fund a massive investment program aimed at expanding Jeep, Alfa Romeo, and Maserati around the world.

But Marchionne wasn’t just doing corporate finance. He was doing something more ambitious: trying to change what Ferrari was, in investors’ minds.

His argument was simple and radical. Ferrari shouldn’t be valued like an automaker. It should be valued like a luxury-goods house—closer to brands like Hermès or Prada than Ford, GM, or BMW. That wasn’t just semantics; it was a bid for a completely different valuation framework. Automakers tended to trade at low single-digit EV/EBITDA multiples. Luxury groups routinely earned far higher multiples. If the market accepted Ferrari as luxury, the value unlocked wouldn’t come from building more cars—it would come from being seen differently.

The IPO’s reception suggested he was right. When Ferrari debuted on the NYSE, shares jumped about 13% in early trading. Ferrari raised $893 million by selling 9% of the company at $52 a share. Demand swamped supply; investors wanted far more stock than was available.

And the deal mechanics were as deliberate as the story. FCA sold 17 million shares in the IPO, keeping the proceeds. Then, a few months later, FCA distributed most of its remaining Ferrari stake to FCA shareholders as a stock dividend. After the spin-off, about 90% of Ferrari shares were publicly traded, with the remaining 10% retained by the Ferrari family.

The spin-off was completed on January 3, 2016, and Ferrari began trading on the Milan Stock Exchange soon after.

Marchionne had pulled off the trick: Ferrari wasn’t being priced like a car company anymore. It was being priced like a luxury house that happened to build cars.

VII. The Marchionne Doctrine: Scaling Without Diluting (2016–2018)

With Ferrari now independent, Sergio Marchionne finally had the freedom to run his playbook. The headline was growth—but with a hard ceiling: push production up to 10,000 cars a year, and not a single unit more.

That limit wasn’t just a vibe. It was a line in the sand drawn with U.S. regulation in mind. Under American EPA rules, manufacturers producing fewer than 10,000 vehicles annually can qualify for significant exemptions, sidestepping fuel-economy and emissions requirements that might otherwise force expensive engineering trade-offs. Marchionne saw the opening immediately: Montezemolo’s informal cap of around 7,000 units left a wide gap before Ferrari hit that regulatory tripwire.

To Marchionne, that gap meant something very specific: room to sell thousands more cars a year—without crossing the point where Ferrari would start looking, operating, and being regulated like a normal automaker.

But the real trick wasn’t the number. It was the method.

Ferrari’s most important growth lever wasn’t a factory line. It was allocation. By keeping production below demand, Ferrari protects the very things that make the cars feel inevitable rather than optional: scarcity, long waiting lists, and strong resale values. Those elements reinforce each other in a loop—rarity drives desire, desire sustains pricing power, and pricing power strengthens the mythology.

The company didn’t just watch volumes; it watched wait times and the mix of where cars were delivered. In recent years, Ferrari increased the proportion of shipments to the Middle East and Greater China as part of its broader effort to manage waiting lists and preserve the sense that supply would never catch up to demand.

Inside that system, access became the product.

Ferrari doesn’t simply sell to whoever can write the check. It curates. Existing owners get priority. Loyalty matters. And for the most exclusive special-series cars—the kind of halo machines exemplified by the LaFerrari—being rich isn’t enough. You have to be chosen, typically after years of ownership and relationship-building. Customers don’t just buy Ferraris; they build a history that earns them the right to buy the next one.

At the same time, Marchionne kept pushing Ferrari to behave less like a car company and more like a luxury brand with multiple revenue streams. Sponsorship, commercial, and brand revenues reached Euro 670 million in 2024, up 17.1%. Formula 1, once seen as a costly obligation, increasingly functioned as a global marketing engine and a business in its own right, powered by sponsorship and prize money.

Then, in July 2018, the story took a hard turn. On July 25, Sergio Marchionne died at age 66 following complications from shoulder surgery. By then, one of his defining moves—the Ferrari IPO—had already been vindicated by the market: Ferrari’s stock was up 148% since going public.

Louis C. Camilleri, a longtime Philip Morris executive and Ferrari board member, stepped in as CEO.

Marchionne left Ferrari fundamentally changed—independent, publicly traded, and widely valued as a luxury business rather than an automaker. But he also left an open question hanging over the future, one that would test the brand’s identity more than any production target ever could: could Ferrari enter the SUV market without breaking the spell?

VIII. The SUV Heresy: Purosangue Development (2017–2022)

For decades, Ferrari executives had a rehearsed answer whenever someone floated the idea of an SUV: never. The prancing horse meant low-slung sports cars, racing pedigree, and a direct, visceral bond between driver and machine. An SUV wasn’t just off-brand. It sounded like betrayal.

Then Porsche happened.

When the Cayenne launched in 2002, purists called it a desecration of the 911’s legacy. Instead, it became Porsche’s best-selling model—and the cash machine that helped fund the rest of the lineup. Lamborghini followed with the Urus, and it quickly turned into that brand’s volume leader.

Ferrari could see the same forces pulling at its own customer base. The luxury SUV segment was exploding, and many Ferrari buyers already had a Cayenne or an Urus in the garage. The question stopped being “should Ferrari do this?” and became “what happens if Ferrari doesn’t?”

Development of Ferrari’s answer—internally codenamed F175—began in 2017 and was hinted at by Sergio Marchionne. But the company treated the project like a tightrope walk: build something new without turning Ferrari into just another luxury automaker chasing trends.

When the Purosangue was unveiled on 13 September 2022, Ferrari made its position clear immediately. This was the brand’s first production four-door vehicle and its first sport utility vehicle—and yet Ferrari refused to call it an SUV. Internally and in marketing, it leaned on “Ferrari Utility Vehicle,” trying to frame the car as a Ferrari first, category second. In the real world, though, the competitive set was obvious: Aston Martin DBX, Lamborghini Urus, the top shelf of fast luxury SUVs.

Ferrari’s engineering choices were its argument. Instead of following competitors into turbocharged V8 territory, the Purosangue launched with a naturally aspirated 6.5L V12 paired with an 8-speed dual-clutch transmission—an unapologetically Ferrari configuration for a vehicle with four doors and usable rear seats. If you were going to commit heresy, Maranello’s view seemed to be: commit with conviction.

And then came the most Ferrari move of all: scarcity. Benedetto Vigna reiterated that Purosangue production would be limited to 20% of Ferrari’s overall sales, specifically to protect the brand’s exclusive image. In other words, Ferrari would enter the hottest segment in luxury cars—but would still make sure you couldn’t easily get one.

The market’s response was immediate. In 2023, Ferrari reported a 27% increase in first-quarter profits, helped by the Purosangue launch, with total sales up 10% from the same quarter. Demand quickly pushed delivery timelines far out: new Purosangue orders weren’t expected to be filled until 2026, while the broader Ferrari lineup was sold out into 2025.

By mid-2024, the Purosangue was already showing up as a meaningful part of the mix. JATO Dynamics data placed it as Ferrari’s third-best-selling model between January and August 2024, with nearly 1,500 units sold through August—behind the 296 (over 3,100) and the Roma (nearly 1,900).

Most important: the feared brand backlash never materialized. If anything, the Purosangue became proof of concept for the Marchionne-era thesis—Ferrari could expand into a new category without diluting the myth, as long as it refused to compromise on performance, engineering, and, above all, exclusivity.

IX. Modern Ferrari: The Vigna Era and Electrification (2021–Present)

On 9 June 2021, Ferrari announced its next CEO: Benedetto Vigna.

It wasn’t the kind of appointment the car world saw coming. Vigna wasn’t a lifelong auto executive or a charismatic racing boss. He was a physicist. An Italian who had been running a division at STMicroelectronics, the Geneva-based semiconductor company—deep in the world of sensors, chips, and miniaturized hardware.

And there’s a neat irony there. Vigna’s specialty was motion sensors—first critical to automotive airbags, then far more lucrative in consumer electronics. If you’ve ever used a Nintendo Wii controller, you’ve felt the impact of that work. The same sensor miniaturization also enabled features like automatic screen rotation on smartphones.

Vigna was born in Potenza, in the Basilicata region, and grew up in nearby Pietrapertosa. He graduated with honors in physics from the University of Pisa in 1993, and then did early research work across Europe—at CERN in Geneva, at the ESFR in Grenoble, and at the Max Planck Institute in Munich.

Over his career, he registered more than 200 patents. In 2010, he was shortlisted for the “European Inventor” award. In 2015, he received the IEEE Frederik Philips Award for leadership in MEMS technology.

So why would Ferrari hand the keys to Maranello to a semiconductor inventor?

Chairman John Elkann made the logic explicit: “His deep understanding of the technologies driving much of the change in our industry, and his proven innovation, business-building and leadership skills, will further strengthen Ferrari and its unique story of passion and performance, in the exciting era ahead.”

Vigna didn’t come in swinging a chainsaw. But he did come in with a technician’s eye for wasted motion—and he quickly decided Ferrari had accumulated too much organizational weight. He later said the company was being held back by its “bureaucratic mass index.”

One moment crystallized it. In a cybersecurity meeting, he counted nine levels of employees in the room—and noticed that only the lowest-ranking person had anything useful to add. So he started flattening. Restructuring groups. Removing layers.

Even Ferrari’s test drivers—people you’d think the CEO would want close—had been separated from him by six layers of management. Under Vigna, that dropped to three.

But his philosophy was incremental, not incendiary. “When you change the culture of a company, it’s never a revolution. It’s an evolution. If you have a revolution, you will have a lot of passive resistance and you will be inefficient.”

While the org chart slimmed down, the business kept doing what modern Ferrari does best: growing without “growing up” into a normal automaker.

Vigna framed it with a line that has become his signature: “Quality of revenues over volumes.” In 2024, he said, that focus—strong product mix and rising demand for personalization—explained Ferrari’s results and set the company up for further growth in 2025, reaching the high end of its 2026 profitability targets a year early.

In 2024, Ferrari’s EBITDA rose to Euro 2,555 million, up 12.1%, with an EBITDA margin of 38.3%. Operating profit (EBIT) climbed to Euro 1,888 million, up 16.7%, with an EBIT margin of 28.3%. For a company that still builds cars in relatively tiny numbers, those margins are the whole story.

And much of that story is customization.

Personalization has become one of Ferrari’s most powerful profit engines. By Q3 2025, personalizations accounted for about 20% of total revenues from cars and spare parts. Customers weren’t just choosing a spec—they were commissioning it: special paint, bespoke interiors, unique trim and materials, the kind of options that can add staggering amounts to the bill, at margins that make the base car look almost ordinary.

Ferrari expected its Sports Cars activities to generate around 2 billion euros in revenue over the plan period, helped by richer mix and bigger contributions from personalizations. To feed that demand, it planned two new Tailor Made centers in Tokyo and Los Angeles.

On the product side, Ferrari also kept its tradition of periodic, myth-making flagships alive. In October 2024, it unveiled the F80—its new halo supercar, positioned in the lineage from the 1984 GTO through the 2016 LaFerrari Aperta. The F80 paired a V-6 with three electric motors for a combined 1,184 horsepower, and it would be built in a limited run of 799 examples, with U.S. deliveries beginning in early 2026.

Demand did what Ferrari demand always does: it overwhelmed supply. Ferrari’s Chief Marketing Officer even expressed regret about having to turn people away—interest ran more than three times the planned output. And despite a $3.9 million price tag, it sold out.

But the biggest change under Vigna wasn’t a single limited-run car. It was the next phase of Ferrari’s powertrain future.

At Capital Markets Day 2025, Ferrari showed the production-ready chassis and components of its first full-electric car—an historic milestone for the Prancing Horse. It was presented not as a rupture, but as the next step in a “multi-energy strategy”: internal combustion, HEV and PHEV powertrains, and now fully electric.

Ferrari framed the moment as the payoff from a long technical journey that began with hybrid work rooted in Formula 1. It ran from the 599 HY-KERS prototype in 2010, to the 2013 LaFerrari, and then into modern hybrid road cars like the SF90 Stradale and the 296 GTB. The company’s stated rule was simple: it would only launch a fully electric Ferrari once the technology could deliver superlative performance and a driving experience that still felt authentically Ferrari.

Ferrari revealed its first EV on October 9, 2025. The car was expected to go on sale in early 2026, with a starting price above $500,000.

Looking out toward the end of the decade, Ferrari reiterated its target mix: by 2030, EVs would make up 40% of annual sales, hybrids another 40%, and internal combustion engines the remaining 20%. And even as it prepared for electrification, Ferrari continued to champion the V-12—committing to support it for as long as regulations allow.

X. The Business Model Masterclass

Ferrari’s business model is controlled scarcity, executed with the kind of discipline most companies can’t tolerate—and competitors can’t copy.

The ingredients sound straightforward: keep production tightly limited, keep demand higher than supply, and use personalization to lift the value of every car that leaves Maranello. Add a covered order book stretching through 2026, and you get the modern Ferrari engine: high margins, strong resale values, and a customer base that stays in line even when the economy doesn’t.

Start with the allocation game. Ferrari doesn’t just sell to whoever has the money. It decides who gets the cars. The company tracks customer behavior and rewards loyalty, creating a ladder of access where ownership history matters. The result is a self-reinforcing loop: cap production, preserve rarity, lengthen waiting lists, and protect residual values. Ferrari’s advantage isn’t that everyone recognizes the badge. It’s that not everyone gets permission.

That dynamic flips normal commerce on its head. Ferrari can raise prices, restrict access, and still see demand expand. That’s luxury economics at its purest: higher prices can increase desire, because the price itself becomes proof that the product is special. And those multi-year waiting lists act like shock absorbers. When a downturn hits, Ferrari has a pipeline of pre-sold demand that many automakers can’t even imagine.

At the very top of the pyramid, it gets even stricter. For Ferrari’s most exclusive cars—like the F80—wealth is table stakes. Customers typically need a long ownership history, deep participation in the Ferrari world, and a track record of being the “right” kind of client. Even then, there’s no guarantee. Ferrari picks you.

That’s the defining signal of true luxury: the seller holds the power, and the buyer competes for the privilege.

And Ferrari isn’t just selling cars. Roughly 15% of its revenue comes from activities like Scuderia Ferrari’s Formula 1 partnerships, lifestyle licensing, and financial services. This “brand” segment carries exceptional margins, and it turns the prancing horse into a business that earns even when no car changes hands.

Formula 1, in particular, does triple duty. It’s constant global exposure—every race weekend is essentially a Ferrari broadcast. It gives Ferrari credibility when it talks about performance and technology transfer. And it produces the emotion and narrative that keep customers loyal, year after year.

In 2024, that narrative strengthened. The season was one of the most competitive since F1 entered its hybrid era in 2014. Under Team Principal Frédéric Vasseur, Ferrari stayed in the fight for the Constructors’ Championship until the final race, finishing the year with five wins and 22 podiums—momentum that mattered far beyond the track.

Then there’s personalization: Ferrari’s quiet profit engine. The company’s margin expansion has been driven largely by richer product mix and rising demand for bespoke options—spec choices that can dramatically lift the price of a car, often at exceptional margins. Over time, Ferrari has made that shift deliberately, building a system where customers don’t just buy a model; they commission their version of it.

Finally, capital allocation under Vigna has stayed as disciplined as the production cap. Ferrari has generated over one billion euros in industrial free cash flow annually, and in 2024 that cash funded dividends, share buybacks, and R&D—without increasing debt.

XI. Playbook: Lessons in Luxury and Scarcity

Ferrari’s playbook is a masterclass in building long-term value through two forces most companies treat as opposites: growth and restraint.

The paradox is that Ferrari doesn’t grow the way manufacturers are supposed to. Most businesses chase scale. Ferrari chases value per car—while keeping production tight. In 2024, it delivered 13,752 cars, barely more than the year before. And yet revenue rose to EUR 6.677 billion. The point isn’t the extra handful of cars; it’s that Ferrari keeps getting better at monetizing each one through mix, pricing power, and personalization.

That only works because scarcity isn’t an accident at Ferrari. It’s the product. The waiting list isn’t a failure of operations—it’s proof the spell is still working. If you can’t easily buy one, owning one means more.

Ferrari’s moat is brand equity so deep it looks unfair. Plenty of automakers can engineer fast cars. Very few can make a car feel like a cultural artifact. Ferrari has the traits of a luxury compounder: high margins, strong cash generation, and the ability to raise prices without killing demand. The market values that differently than it values volume-driven automaking, because it’s powered by scarcity and reputation, not scale.

And crucially, it’s not something a competitor can simply copy. You can’t replicate 75 years of mythology, racing heritage, and global symbolism on a product roadmap. Authenticity isn’t a marketing campaign—it’s accumulated history.

The hardest part of the Ferrari model might be the simplest to state: Ferrari says no. It turns away customers with money in hand. It keeps production below demand. It limits access to its most desirable cars to a select set of buyers. That restraint takes nerve, especially for a public company living under constant expectations of growth. Every “no” is revenue left on the table today, in service of pricing power and desirability tomorrow.

That discipline is why copycats struggle. Many brands have tried to mimic the formula—make fewer units, charge more, cultivate “exclusivity.” But Ferrari’s system is hard to fake for three reasons.

First, credibility has to be earned over decades. Ferrari didn’t become valuable because it decided to sell expensive cars; it became valuable because Enzo Ferrari built a racing machine that the world couldn’t look away from.

Second, luxury requires consistency. Ferrari has kept its identity intact through leadership changes, ownership shifts, and strategic pivots. Even the Purosangue—an SUV in the most literal sense—still reads unmistakably as a Ferrari.

Third, almost every luxury brand eventually gets tempted by volume. Expanding downmarket is the easy growth lever, and it’s usually the one that quietly erodes the brand. Ferrari has chosen the harder path again and again: fewer cars than demand, carefully allocated, at ever-higher value.

XII. Bear vs. Bull: The Investment Case

The Bull Case

Unassailable Brand Power and Pricing Leverage

“Our pricing power is not at an end. We are confident that with continuous innovation, we can maintain strong pricing power. We will offer cars with different positioning, enriched with innovative features, ensuring that our pricing reflects the added value and delight for our clients.”

Most automakers discount to move metal. Ferrari does the opposite. It can raise prices because customers don’t experience buying a Ferrari as a transaction—they experience it as admission. And in luxury, the price isn’t just a number; it’s part of the signal. When Ferrari pushes pricing, the brand can actually feel more desirable, not less.

Personalization as a Profit Engine

Personalization has become a real second business inside the first. It’s now close to one-fifth of revenue from cars and spare parts, allowing Ferrari to grow without relying on meaningfully higher unit shipments. That shows up in the numbers, but more importantly it shows up in behavior: customers aren’t just selecting options, they’re commissioning their car.

And there’s still runway. As Ferrari adds Tailor Made centers and keeps widening what “bespoke” can mean, the average Ferrari can keep getting more valuable—one buyer at a time.

SUV Success Without Brand Dilution

The Purosangue answered the question that used to make purists flinch: can Ferrari sell a four-door, high-riding vehicle and still feel like Ferrari? So far, the market’s verdict has been yes. It expanded the category Ferrari can play in—while Ferrari kept control of the only lever that truly matters here: limiting supply so the badge doesn’t become common.

Electrification as Opportunity

For most of the industry, EVs have been a margin and demand headache. For Ferrari, they’re a chance to reframe “the most advanced Ferrari” in the language of the next decade. If the first full-electric Ferrari starts above $500,000, the bet is clear: Ferrari’s customers are buying the Prancing Horse, not a drivetrain. Electrification becomes another way to sell performance—and to charge for it.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers Analysis

Ferrari shows several of Helmer’s durable advantages:

Brand – Not just recognition, but meaning. Decades of racing heritage and luxury positioning translate into pricing power that most manufacturers can’t touch.

Cornered Resource – The Ferrari brand, and the ecosystem around it, functions like a resource nobody else can buy or build on a timeline.

Counter-Positioning – Ferrari’s model depends on refusing volume. Mass-market competitors can’t credibly mimic that without blowing up their own economics.

The Bear Case

Valuation at Perfection

The flip side of being treated like luxury is being priced like luxury. Ferrari’s multiple leaves little room for a bad quarter, a softer order book, or a model cycle that doesn’t land. When expectations are this high, even small disappointments can hit the stock hard.

Regulatory Risks to ICE Engines

Emissions rules keep tightening, and some jurisdictions are moving toward outright bans on internal combustion engines. Ferrari is preparing for a multi-energy future, but regulation could force the transition faster than the brand—or its customers—would ideally choose.

China Luxury Slowdown

Mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan decreased by 328 units in 2024.

Luxury demand in China has been a powerful tailwind for years, but economic headwinds and shifting consumer sentiment can turn that tailwind into turbulence. Even for Ferrari, regional softness matters—especially when the rest of the model relies on demand staying comfortably above supply.

Brand Dilution Risk

Ferrari’s greatest asset is also its most fragile: exclusivity. If too many cars hit the road, if model lines blur, or if the lineup starts to feel overextended, the brand can lose the very scarcity that supports pricing power. Ferrari can grow, but it has to keep proving it can grow without becoming normal.

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis

Supplier Power – Moderate. Ferrari relies on specialized suppliers, but its scale, specifications, and brand pull help keep leverage in check.

Buyer Power – Very Low. Ferrari runs allocation. Waiting lists and customer ranking eliminate negotiation in the way it exists in normal car buying.

Competitive Rivalry – Low. There are plenty of fast, expensive cars, but Ferrari occupies a distinct emotional and historical category that narrows true competition.

Threat of New Entrants – Very Low. You can’t manufacture decades of heritage, racing credibility, and customer obsession.

Threat of Substitutes – Low to Moderate. Customers could spend their money on other luxury assets—watches, real estate, art—but Ferrari offers a specific kind of status and experience that doesn’t translate cleanly.

Key Performance Indicators to Track

For anyone trying to judge whether the Ferrari model is still working, two signals matter most:

1. Revenue Per Vehicle Delivered – This is the cleanest read on the strategy: can Ferrari keep extracting more value through pricing, mix, and personalization, even if shipments stay relatively flat?

2. Order Book Visibility – Waiting lists are not a nuisance at Ferrari; they’re a metric. A multi-year order book is demand insurance, and it’s one of the biggest reasons Ferrari’s earnings profile looks so different from normal automakers.

XIII. Epilogue: The Eternal Balancing Act

What would Enzo Ferrari think of today’s company?

He’d almost certainly sneer at the idea of a Ferrari SUV—though he might quietly respect that it showed up with a V12. He’d likely wave off the stock market as noise, an annoying sideshow to the only scoreboard that ever really mattered to him. And he’d probably be baffled by the personalization machine, where clients commission paint and stitching the way patrons once commissioned art. In his day, you took what Maranello built. If you didn’t like the color, that was your problem.

And yet: he’d recognize the core immediately.

Ferrari still builds road cars to fund racing, and it still uses racing to give the road cars their meaning. The flywheel Enzo set in motion in 1947—performance, victory, mythology, demand—still spins. The scale is bigger, the finance is more sophisticated, the customer management is practically surgical. But the logic remains unmistakably Ferrari.

The electric transition is the biggest identity test the brand has faced. For decades, Ferrari’s sound—the high-revving wail—has been inseparable from its allure. With the Elettrica, Ferrari has said it developed a distinctive sound to accentuate the unique characteristics of the electric powertrain, aiming to preserve a recognizable Ferrari signature even as the engine disappears.

The deeper question is whether an electric Ferrari can still feel like “la macchina”—the machine its customers expect. Ferrari’s claim is clear: the Elettrica pairs state-of-the-art technology with superlative performance and the same driving pleasure that defines every Ferrari, with key components developed and manufactured in-house to deliver performance and uniqueness that only Ferrari can offer.

While the road-car business keeps compounding, the racing side reminds everyone how hard it is to stay on top. Ferrari ended 2025 fourth in the Formula 1 teams’ standings, two places lower than 2024. The gap to McLaren exploded—from 14 points in 2024 to 435 in 2025. Team boss Frédéric Vasseur was candid about the tradeoff: “McLaren was so dominating in the first four or five events that we realised it would be very difficult for 2025,” he said. “It meant that we decided very early in the season to switch to ’26.”

That’s the next reset. New 2026 regulations promise a reshuffle, and with Lewis Hamilton now driving for the Scuderia, the expectations are enormous.

But zoom out, and the most remarkable part of Ferrari’s story is how consistent it has been. Through Enzo’s personal dramas, Fiat’s control, the Montezemolo renaissance, Marchionne’s financial engineering, and Vigna’s organizational and technological overhaul, the essential Ferrari has endured.

It’s still a company that makes beautiful, fast, impractical cars for people who don’t need them but want them badly. It’s still a company where racing pride competes with profit margins for oxygen. And it’s still a company that treats heritage not as a museum piece, but as a constraint—a line it refuses to cross even as the world changes around it.

“The world needs brands that are both agile and consistent with their DNA and values. In a time when respect and consideration are increasingly rare, it is crucial to pay attention to all stakeholders. For Ferrari, this means engaging with the local community through educational projects. We believe in co-prosperity.”

In an era of disruption, commoditization, and relentless competitive pressure, Ferrari stands as proof that some things resist disruption. Authenticity built over generations. Emotional connection forged through triumph and tragedy. The indefinable mystique of a prancing horse on a yellow shield. Valuable precisely because they can’t be manufactured, replicated, or bought.

XIV. Recent News and Developments

Q3 2025 Financial Results

Ferrari’s Q3 2025 results looked exactly like modern Ferrari: modest unit growth, strong revenue growth, and margins that still read more like luxury than auto. Net revenues came in at Euro 1,766 million, up 7.4% versus the prior year, on total shipments of 3,401 cars. Operating profit (EBIT) was Euro 503 million, up 7.6%, for an EBIT margin of 28.4%. EBITDA reached Euro 670 million, up 5.0%, with a 37.9% margin.

CEO Benedetto Vigna framed it as execution plus clarity: “We continue to advance with conviction and strong visibility on our development path. At our Capital Markets Day, we have defined a clear trajectory in the long-term interests of our brand, setting the floor for sustainable growth toward 2030.”

Ferrari Elettrica Reveal

Ferrari says its Elettrica program is ready to move into production—and that it’s not just an “electric Ferrari” in name, but in intellectual property. The project includes more than 60 patented proprietary technological solutions.

The first all-electric Ferrari uses two electric axles developed and built entirely in-house. Each axle features a pair of synchronous permanent magnet engines with Halbach array rotors derived from F1 technology. Ferrari highlighted power density and efficiency figures for both axles, positioning the engineering as performance-first rather than compliance-driven.

Ferrari also emphasized the battery: nearly 195 Wh/kg energy density, with a cooling system designed to manage heat distribution and sustain performance.

F1 2025 Season and Hamilton's Move

On track, 2025 carried a very Ferrari kind of tension: huge expectations, flashes of brilliance, and a season that still felt like a work in progress.

Charles Leclerc finished the year with 242 points to Lewis Hamilton’s 156 in their first season as teammates. Leclerc had the stronger head-to-head record, but context matters: 2025 was Leclerc’s seventh year at the Scuderia, while Hamilton spent the season adapting to a completely new environment.

Hamilton’s high point—Ferrari’s standout moment of the year—came early. In only the second round of the season, he won the Sprint in Shanghai after taking Sprint pole on Friday.

New Model Launches

Ferrari kept the product drumbeat steady, rolling out six new models in 2025. Among them: the 296 Speciale, the 296 Speciale A, and the most closely watched launch of all—the Ferrari Elettrica.

XV. References and Sources

- Ferrari N.V. annual reports and SEC filings (Form 20-F)

- Ferrari quarterly earnings releases and investor presentations

- Ferrari Capital Markets Day 2025 materials

- Formula 1 official results and statistics

- Reporting and analysis from Bloomberg, Reuters, and the Financial Times

- Automotive industry analyst reports (including Morningstar and Goldman Sachs)

- Enzo Ferrari: The Man and the Machine by Brock Yates

- Ferrari corporate website and official press releases

Chat with

this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with

this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music