Mowi: The "Blue Revolution" and The King of Salmon

I. Introduction: The "Sushi Economy"

Picture a poke bowl on a lunch desk in Manhattan. A perfectly trimmed salmon fillet under bright lights at a Carrefour in Paris. Salmon nigiri sliding across the counter at an izakaya in Tokyo.

Behind all of them is the same quiet force: a Norwegian company most people have never heard of, even as its fish shows up on their plates again and again.

That company is Mowi. It’s one of the largest seafood businesses on Earth, and the world’s largest producer of farmed Atlantic salmon, with roughly 20% global market share. In 2024, Mowi posted its highest-ever revenue and harvest volumes: EUR 5.62 billion in revenue and 502,000 tonnes of salmon harvested.

That’s an almost hard-to-grasp amount of fish. Roughly the weight of about 84 fully loaded Boeing 747s—every month. In meal terms, it works out to around 8 million servings a day, a meaningful source of high-quality protein in places where access to diverse seafood is limited.

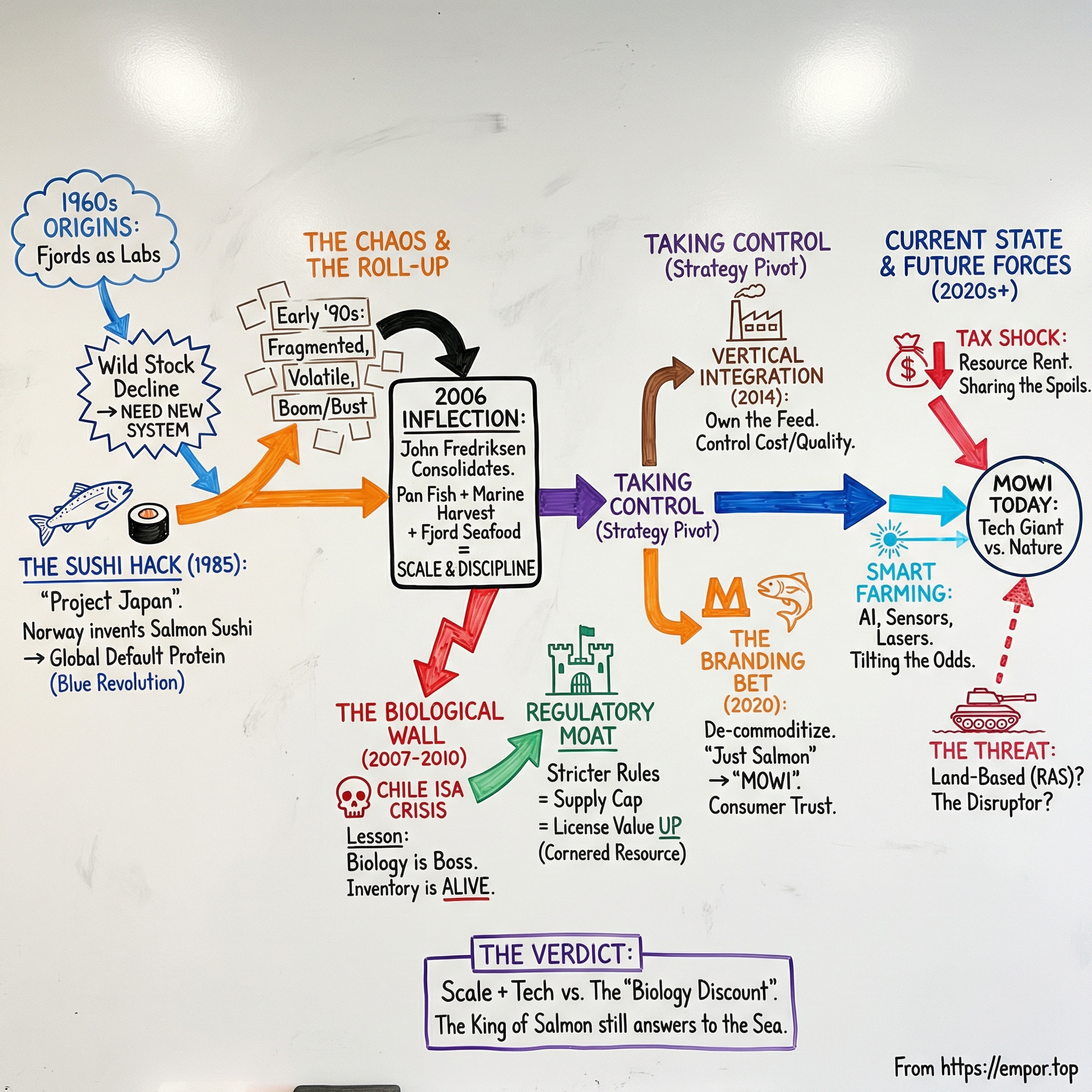

So how did salmon become the default “healthy, global, goes-with-everything” protein it is today?

Part of the answer is one of the most audacious cultural hacks in modern food history: Norway helped invent salmon sushi.

Eating salmon raw on sushi is surprisingly new. In the 1980s, Norway set out to convince Japan—home of sushi—that raw salmon wasn’t just acceptable. It was premium.

In 1985, a group of determined Norwegians flew to Tokyo with a simple mission: introduce the Japanese market to Norwegian salmon. What followed helped create salmon nigiri as we know it today—and put Norwegian farmed salmon at the center of it.

This wasn’t a happy accident. Thor Listau, a member of Norway’s fisheries committee, saw something the market wasn’t pricing correctly. In Japan, tuna was king—revered, expensive, fought over at auction. Salmon, by contrast, was treated as second-tier: often cooked, dried, and sold cheap. Meanwhile, Norway’s rapidly improving salmon-farming industry was producing more fish than it knew how to sell.

There was just one major problem: Japan didn’t want raw salmon. The salmon Japanese consumers were familiar with often carried parasites, so they cooked it. Raw salmon sounded, to put it politely, unappetizing.

Norwegian salmon was different. It was farmed in cold fjords, under controlled conditions, and marketed as parasite-free. But “different” isn’t enough to change a country’s eating habits.

It took Listau and his “Project Japan” team nearly fifteen years to make raw salmon mainstream. First, they had to educate the market on the difference between Pacific salmon and Norwegian Atlantic salmon. Then they had to win over chefs, distributors, and consumers—one skeptical bite at a time. The numbers tell the story: in 1980, Norway sold two tonnes of salmon to Japan. Twenty years later, it was more than 45,000 tonnes.

Japan’s adoption didn’t just boost Norwegian exports. It created a global default. Today, across 17 of the 20 countries surveyed, salmon is the most preferred sushi topping. And Mowi is a major engine behind that demand—whether salmon shows up as a $40 omakase course or a $12 weeknight dinner.

Now comes the real question: how did an industry that started as a patchwork of small, backyard fish farmers turn into a global powerhouse worth about €130 billion in market cap today?

The answer runs through biological innovation, brutal consolidation, regulatory constraints that accidentally became a moat, and one timeless strategy: control supply just as demand begins to compound. Let’s dive in.

II. Ancient History and The Pioneers

To understand Mowi’s dominance, you have to rewind to western Norway in the 1960s, when a small group of pioneers tried something that sounded borderline absurd: domesticate the ocean.

Mowi’s story began in 1964, at a time when the old way of getting salmon—catching it—was starting to break. Wild stocks were declining around the world. Commercial fishing had pushed Atlantic salmon to worrying levels. If salmon was going to become a reliable, global food, the world needed a new supply. Not more boats. A new system.

Norway had the perfect natural lab for it. A vast, jagged coastline carved into deep, sheltered fjords. Cold, clean seawater. Strong currents. And thanks to the Gulf Stream, conditions that stayed remarkably stable. These weren’t just scenic inlets; they were ready-made, high-quality growing environments—nature’s fish tanks.

The name “Mowi” comes from one of those early builders: Thor Mowinckel. In the late 1960s, Mowinckel—backed by expertise from a Bergen aquarium and funding from Norsk Hydro—helped establish modern salmon farming in a closed cage at Flogøy on Sotra, about 20 kilometers from Bergen. It wasn’t a romantic tale of fishermen with nets. It was engineering, experimentation, and capital applied to biology.

That’s a theme that shows up again and again in salmon farming’s early history. This wasn’t just a fishing story—it was an industrial story. Big companies, including Norsk Hydro and Unilever, were there from the beginning. Norway’s hydropower know-how—its other great natural resource—fed directly into early breakthroughs like water circulation and temperature control.

And this wasn’t only happening in Norway. Across the North Sea, in Scotland, Unilever founded a company in Lochailort in 1965 that would become the first to use the name Marine Harvest, developing farming methods at a dedicated research facility right as Atlantic salmon aquaculture was taking shape.

But if the 1960s were the “can this even work?” era, the 1980s and 1990s were the “Wild West.” The business exploded—too fast, too fragmented, and with too little coordination. The industry was made up of thousands of small family operations, often holding a single license, each making independent decisions about how many fish to stock and when to harvest. That meant no discipline on supply, which meant violent price swings. When salmon prices rose, everyone expanded. When prices fell, bankruptcies followed.

Pan Fish became a symbol of both the ambition and the chaos. Pan Fish Holding AS was founded in 1992 to roll up fish farms in Norway and abroad. By 1997, after a spree of acquisitions, it listed on the Oslo Stock Exchange as Pan Fish ASA. But the growth was fueled by debt. By the end of 2001, Pan Fish had over NOK 4.7 billion in debt. When salmon prices collapsed in 2001, the balance sheet snapped. The company posted a heavy loss in 2002 and began selling assets to repay creditors.

That same year, a major refinancing arrived—and with it, a purge. In late 2002, the entire board was dismissed, including founder and CEO Arne Nore.

By the early 2000s, the lesson was becoming unavoidable: salmon farming couldn’t stay a cottage industry. It needed consolidation. It needed discipline. It needed someone willing to think at industrial scale.

That someone was about to arrive.

III. The John Fredriksen Roll-Up: The 2006 Inflection

Enter John Fredriksen—one of the most polarizing, and undeniably effective, industrialists of his era.

He was born in 1944 in a working-class suburb of Oslo, the son of a welder. He didn’t inherit a fleet; he worked his way into shipping as a courier for a local broker, then bounced through the global shipping circuit in the 1960s—New York, Singapore, Athens, Beirut—learning the business from the inside.

Early on, he learned the hard way that shipping can punish you fast. He reportedly lost close to $1 million on his first freighter purchase. But the loss didn’t scare him off. It taught him where the real edge was: volatility.

Fredriksen found opportunity in instability—especially wartime instability. During the Yom Kippur War in 1973, he locked in long-term tanker charter contracts, then watched the economics swing in his favor as prices rebounded in the years that followed. In the 1980s, during the Iran–Iraq War, he kept moving oil through a world of missile threats and naval risk. His biographer captured the reputation that followed with a line that stuck: “he was the lifeline to the Ayatollah.”

By the mid-2000s, Fredriksen was looking for the next arena where a ruthless operator could impose order. He was already a Norwegian-born, Cyprus-based shipping billionaire, best known for building the world’s largest oil tanker fleet, with major interests across energy and shipping. But he saw something familiar in salmon: a commodity business with brutal price cycles, massive capital requirements, and—most importantly—an industry so fragmented that nobody could control supply.

To him, salmon farming looked like oil tankers with fins.

The consolidation wave that reshaped modern aquaculture started with his moves. In the second quarter of 2005, Domstein sold its 24% stake in Fjord Seafood to Fredriksen’s investment vehicle, Geveran Trading. Around the same time, Pan Fish disclosed that two companies indirectly controlled by Fredriksen had accumulated a combined 48% of its shares.

This was classic Fredriksen: take big positions when the industry is hurting, then force the pieces together.

And the market quickly realized what he was aiming at. Word spread that he wanted to use Pan Fish as the platform to acquire Marine Harvest—already the largest player—for around $1.4 billion. If he could pull it off, it wouldn’t just be another acquisition. It would be the moment salmon farming stopped being a scattered collection of operators and started looking like an actual global industry.

The key domino fell when Nutreco agreed to sell its 75% stake in Marine Harvest to Geveran Trading for €881 million. Geveran would also acquire the remaining 25% held by Stolt-Nielsen. With meaningful stakes sitting across Pan Fish and Fjord Seafood as well, the chessboard was set.

In 2006, the industry’s “big bang” arrived: a three-way combination of Pan Fish ASA, Marine Harvest N.V., and Fjord Seafood ASA. The deal created the world’s largest farmed Atlantic salmon producer at the time—an entity estimated to control about a fifth of global farmed salmon.

Regulators noticed. In the UK, the Competition Commission scrutinized the transaction, warning that eliminating rivalry between major producers could push up prices and harm consumers—especially those with a strong preference for Scottish salmon. The remedy was painful but straightforward: to get the deal done, parts had to be sold. The former Pan Fish Scotland division was divested as part of the clearance process, and after hurdles in the UK and France were addressed, Pan Fish had control of the Marine Harvest group by the end of 2006.

This is the inflection point. Not because the fish suddenly grew faster—but because the industry’s structure changed.

For investors, it’s the Fredriksen playbook in full: buy when there’s blood in the water, consolidate hard, and use scale not only to run operations better, but to gain real market power in a commodity business. And he didn’t walk away afterward. Fredriksen went on to hold a significant stake in the combined company—about 15%—tying his name permanently to what would eventually become Mowi.

Of course, in salmon farming, there’s one force no billionaire can roll up, refinance, or intimidate:

biology.

And it was about to remind everyone who’s in charge.

IV. Crisis in Chile: The ISA Virus and The Biological Ceiling

The ink was barely dry on the mega-merger when disaster struck. And it would tattoo a permanent truth onto the business model: in salmon farming, biology is the boss.

In July 2007, Chile’s largest salmon company—Norwegian-owned Marine Harvest—announced an outbreak of Infectious Salmon Anemia, or ISA, in Chiloé. ISA is often compared to influenza: it doesn’t affect humans, but in fish it can spread quickly, wreck physiology, and drive high mortality.

The timing was brutal. Chile had become the world’s second-largest salmon producer, and Marine Harvest had invested heavily there. After the first cases, ISA spread fast. Reports documented a surge that peaked in late 2008, turning what began as a localized problem into the most significant disease and economic crisis in the country’s salmon industry history.

The damage was staggering. Chilean Atlantic salmon production collapsed—from nearly 400,000 tonnes in 2005 to an estimated 100,000 tonnes by 2010.

Marine Harvest’s Chilean business went into triage. In 2008, the company undertook a major restructuring as ISA kept spreading. It closed six freshwater sites, 21 sea sites, and two processing plants—Teupa and Chinquihue—two of the five plants it had been running at the start of the year. The human cost was immediate: 1,866 employees were made redundant.

Later, the company acknowledged it had contributed to the conditions that let the virus rip. A Marine Harvest spokesman recognized the company was using too many antibiotics in Chile, and that fish pens were too close together—factors that helped accelerate dissemination.

But ISA also forced the entire industry to internalize a lesson that would shape everything that came next. This isn’t a factory where you can quarantine a defective batch and keep the line moving. The inventory is alive. It eats. It grows. It gets stressed. It gets sick. You can patch a software bug in hours. A biological bug can erase a whole year of production.

And out of that crisis came an unintended consequence: regulation that effectively capped supply.

Norway already had a licensing regime, but after the Chilean meltdown, the political appetite for unchecked expansion faded. Over time—particularly after 2012—regulation tightened further, shifting from irregular, discretionary allocations to more objective criteria based on indicators and environmental performance. The authorities became less focused on who got licenses and more focused on how operations were run, with sustainability and environmental impact moving to the center.

The result was a constraint on production growth right as global demand kept rising—an imbalance that helped drive unusually strong prices and profits. That “rent” later became part of the rationale for Norway’s proposed “rent tax” on aquaculture.

The government’s practical stance was clear: new licenses would be rare. And when something becomes scarce, it becomes valuable. Ordinary commercial licenses began trading in the range of USD 15–20 million for a standard license of 780 tons of maximum allowable biomass.

For Mowi, this created the great salmon-farming paradox. The Chilean crisis nearly wrecked its operations there. But it also helped lock in the value of the assets that mattered most: licenses in the best waters, in the best jurisdictions. And the incumbents who already held them—Mowi most of all—suddenly owned something far harder to compete with than a processing plant or a fleet of wellboats.

V. Taking Control: The Feed Strategy Pivot

By 2012, Mowi’s management faced a strategic question that would shape the next decade: in a business where biology can wipe out your inventory, what can you actually control?

Start with the biggest lever in the P&L. Feed is roughly half the cost of raising a salmon. For years, that spend flowed to a small circle of powerful suppliers—most notably Skretting (owned by Nutreco) and Cargill—who had spent decades perfecting formulations, sourcing, and logistics. If you were a salmon farmer, you could run world-class operations and still find your margins quietly siphoned away by the feed bill.

So Marine Harvest did something that made plenty of people uncomfortable: it decided to make its own feed.

In June 2014, the company launched in-house feed production, opening a 220,000-ton capacity feed factory at Valsneset, Norway. The goal was clear: cover more than half of its Norwegian feed demand internally.

It wasn’t an obvious move. Feed is not a side hustle—it’s heavy industry. And some veterans argued Marine Harvest would be walking straight into a scale game it couldn’t win.

“We conducted a comprehensive analysis when I was the head of Marine Harvest,” said Atle Eide, who led the company in 1995–96 and Pan Fish/Marine Harvest from 2003–2007. “We concluded that we should not enter into feed production. The reason was that we would find ourselves behind in new developments. We wouldn't have enough resources. Feed is truly large-scale process industry. And we would have issues with being self-sufficient in all regions, as some regions were too small, and we could be squeezed by other feed suppliers.”

But the new leadership saw the risk differently. Tor Olav Trøim, John Fredriksen’s long-time right-hand man, framed it as a strategic necessity. “Yes. We wanted to integrate backwards,” he said.

The bet wasn’t just about cost. It was about control. If you own the feed, you’re not simply buying a commodity input—you’re tuning a performance system. Vertical integration meant Marine Harvest could tailor nutrition to its own fish genetics, rather than accept a one-size-fits-all pellet designed for the whole industry.

Then the strategy expanded beyond Norway. In 2019, the same year the company rebranded from Marine Harvest to Mowi, it opened a second feed factory in Kyleakin on Scotland’s west coast—an investment designed to achieve self-sufficiency in Europe. Construction began in early 2019, and the mill reached full production by the end of the year.

At full capacity, the Kyleakin plant could produce 240,000 metric tons annually across feeds for Mowi’s freshwater, seawater, and organic farms. It employed around 70 people. And because feed is a logistics business as much as a formulation business, Mowi’s £100 million investment also extended and modernized the Kyleakin pier to reduce dependence on road transport and support future scale.

Together, the two “state-of-the-art” feed mills gave Mowi 460,000 tonnes of capacity in Norway and 240,000 tonnes in Scotland—about 700,000 tonnes in total. The company became self-sufficient for feed in Europe.

In other words, Mowi stopped being “just” a farmer. It started looking more like an end-to-end protein manufacturer—controlling genetics, feed, farming, processing, and distribution. Integrated production helped stabilize costs, tighten quality control, and improve efficiency. And, over time, it was expected to make earnings less whiplash-prone in a famously cyclical industry.

But even winning strategies get revisited. In March 2025, Mowi initiated a strategic review of its Feed division. In just a few years, it had grown from a roughly 400k GWT farmer to approaching a 600k GWT farmer, with production across seven countries and 11 farming regions—complexity that naturally raises the question: is the feed business best run inside the company, or alongside it in a different structure? The review was set to examine all options, including a sale.

Then, in December 2025, Mowi entered into a strategic and industrial partnership agreement with Skretting/Nutreco, where Mowi would produce feed based on Skretting’s feed formulation—an arrangement positioned to make Mowi an even better salmon farming company.

The feed pivot captures a core lesson for industrial businesses: vertical integration isn’t a philosophy. It’s a tool. Mowi integrated backward when it believed suppliers were extracting too much value—and it stayed pragmatic enough to consider new structures, and partnerships, when they could create more value than going it alone.

VI. From "Marine Harvest" to "Mowi": The Branding Bet

For most of the modern salmon era, consumers bought “salmon.” Not “Mowi.” Not “Marine Harvest.” Just salmon—an anonymous, interchangeable fillet priced by the market that week.

That anonymity is comfortable for shoppers, but it’s brutal for producers. In a commodity business, you’re a price-taker. When supply spikes, prices drop, and the farmer eats the volatility. Meanwhile, the retailer owns the shelf, owns the label, and often captures the premium.

Mowi’s management wanted out of that trap. If they could build a brand that consumers recognized and actively chose, they could sell more than just raw fish into the spot market. They could sell trust, consistency, and a reason to pay up.

So they went for it. The company launched its Mowi brand in the U.S. on March 20, 2020, part of a broader push to de-commoditize salmon and make “Mowi” mean something to consumers.

And the name wasn’t an accident. “Mowi is an inspirational name that recalls our pioneering spirit that has developed over the past 50 years,” CEO Aarskog said. “Since the first salmon was farmed in 1964, we have grown into a global fully integrated company, including breeding, feed, farming, processing and sales.”

The ambition invited a bold comparison: Chiquita for bananas, or Intel Inside for chips—brands that took something generic and turned it into a product people asked for by name. The question was simple: could Mowi do that for salmon?

By 2025, they were pointing to signs that it was working. At the 2025 Seafood Expo North America, Mowi Senior Director of Marketing Diana Dumet told SeafoodSource that consumers were increasingly recognizing Mowi products as something distinct from “just salmon,” and seeking them out specifically. Across multiple KPIs and product reviews, she said, Mowi salmon was being called out for quality.

At that point, the company was selling roughly 32 SKUs across 27 U.S. states.

Brand, in Mowi’s view, wasn’t just a logo on a pack. It was a product strategy. Over the past five years, the company developed multiple product platforms aimed at how people actually cook and eat: Single-Meal Salmon Portions for convenience, Everyday Family-Size Portions for dinner and gatherings, Pre-Seasoned Portions that are ready-to-cook, Salmon Portions with a Butter Puck, and Lightly Smoked Portions for a subtler smoky flavor.

They also leaned into media. The company earned a YouTube Creator Award for reaching 100,000 subscribers on its YouTube channel. “Right now, we’re almost at 310,000 subscribers,” Dumet said. “We are owning the entertainment space as it relates to salmon.” Mowi also partnered with celebrity chefs to share cooking tips with consumers.

Inside the company, the claim was that branded MOWI products were reinforcing that flywheel—more awareness, more loyalty, more repeat purchase. MOWI had become a trusted name in 16 countries across Europe, the US and Asia, and the company planned to continue pushing the branding strategy through 2025 and beyond.

And there were financial signs that value-added was paying off. Consumer Products, Mowi’s consumer-facing, higher-processing business, delivered Operational EBIT of EUR 145.8 million, equivalent to ROCE of 19.0%, alongside record-high volumes of 247k tonnes product weight—strong results in a fiercely competitive category.

This is the branding bet in one line: stop selling an undifferentiated fish and start building a consumer company—one that captures margin across the value chain instead of handing it to the retailer at the last step. Whether Mowi can truly become the “Chiquita of salmon” is still an open question, but the direction of travel is clear.

VII. Current State: Taxes, Tech, and The Future of Food

By early 2026, Mowi is navigating a new operating reality shaped by three forces at once: a controversial tax regime in Norway, a fast-moving technology shift in how fish are farmed, and the looming question of whether land-based facilities can someday compete with the fjords.

The Salmon Tax Shock

On September 28, 2022, the Norwegian government set off a chain reaction across the entire salmon industry. It sent a proposal out for consultation that would introduce a “resource rent tax” on aquaculture, intended to take effect on January 1, 2023. The headline number was an effective 40 percent tax rate on resource rent.

The political logic was straightforward: salmon farmers, the government argued, were earning unusually high profits while operating in fjords and coastal waters that belong to the public. Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre framed it as a question of fairness: Norway has a tradition that value created from common natural resources should benefit society, and the time had come—he said—to apply that principle to aquaculture.

For listed salmon companies, it was a shock. A new layer of taxation, introduced with little warning, immediately changed how investors valued the entire sector.

After intense lobbying and negotiation, the final shape of the tax shifted. Multiple parties reached an agreement to reduce the rate to 25 percent from the originally proposed 40 percent. The Labour Party and Centre Party struck the deal with Venstre and Pasientfokus. The agreement also increased the valuation discount in Norway’s wealth tax from 50 percent to 75 percent, and promised municipalities and counties hosting aquaculture operations higher income through the Aquaculture Fund.

Even with the lower rate, the tax had second-order effects. Offshore aquaculture systems—still in the commercialization phase and reliant on heavy investment—were expected to face a tougher funding environment. Farming permit prices, according to reporting at the time, fell by around 30%.

And the politics didn’t settle. The debate continued to hang over the sector, with Norway’s Conservative Party, Høyre, floating changes in its draft platform. The party had previously pledged to eliminate the resource rent tax if it returned to power, but later language pointed toward reducing it instead. Høyre won local elections in 2023 and was favored in polling ahead of Norway’s national election scheduled for September 8, 2025.

The bigger point for Mowi investors is that, in Norway, the “license moat” comes with a trade-off: if your assets are scarce and profitable because you’re operating in a privileged public resource, the state will eventually want a larger cut.

The Smart Farming Revolution

While the tax fight has played out in public, Mowi has been building something quieter and potentially more durable: a technology stack for farming fish better.

The company’s vision is “smart farming” built on advanced imaging, sensors, and data systems that allow real-time monitoring of biomass, digital lice counting, autonomous feeding, and continuous tracking of fish welfare.

Across the organization, SMART Farming is framed around three pillars. First are Remote Operations Centres—centralized teams that help optimize feeding, improve biological performance, and respond to what the fish need at any moment. Second are Seawater Technologies: next-generation underwater cameras, sensors, and AI designed to tell farmers what’s actually happening below the surface, including real-time biomass monitoring, welfare tracking, autonomous feeding with pellet detection, and automated, stress-free lice counts. Third is MOWInsight, Mowi’s business intelligence platform, which pulls real-time data from internal and external sources so decisions can be made quickly when fish need extra care.

Then there’s the tech that sounds like a joke until you realize it’s deployed at scale: lasers that shoot parasites off fish. Stingray, founded in 2012, has built systems used by more than 30 producers across over 70 locations, spanning up to 900 pens, monitoring and protecting around 60 million salmon and trout globally. Stingray’s General Manager, John Arne Breivik, summed up what it meant for the supplier when Mowi increased its commitment: they were “happy and proud” that the world’s largest salmon farmer planned to use more lasers going forward, as part of a shared effort to improve fish welfare for millions of fish.

Mowi’s CEO Vindheim put the strategic thesis plainly: these “4.0 technologies” should create far clearer scale advantages in the seawater phase than the industry has seen so far. Even after decades of modern aquaculture, he noted, feeding still involved humans watching a camera and clicking a mouse. In his view, feeding is the most important component in the value chain—and it’s headed toward being fully autonomous. Machine learning, he argued, will outcompete craftsmanship, and that shift naturally favors large players with the volume to justify the systems and the data to make them better.

In an industry where biology sets the rules, Mowi’s bet is that software, sensors, and automation can tilt the odds.

The Land-Based Threat

The long-term question hanging over all ocean-based salmon farming is simple: what if technology makes the ocean optional?

Rabobank has argued that recirculating aquaculture systems, or RAS, could change the game over the next decade. The bank identified more than 50 proposed land-based RAS projects for salmon. The combined announced production through 2030 was estimated at roughly a quarter of current global salmon production. Rabobank’s broader claim wasn’t just about new volume; it was about the possibility of reshaping trade flows, supply chains, and the way salmon is marketed.

But the execution has been brutal. Many large RAS farms have struggled to make money. Farming a slow-growing commodity like Atlantic salmon is hard enough in a global market dominated by low-cost sea-cage producers. Layer on relatively unproven technology and the need for more than $100 million in infrastructure, and the hill gets steeper.

Early projects launched around 2010 to 2012—Langsand, Danish Salmon, Jurassic Salmon, and Swiss Alpine—never truly broke through to industrial scale. Atlantic Sapphire, founded in 2017, became the sector’s most famous attempt at doing it big: a Florida-based, land-based salmon farm that raised hundreds of millions and marketed itself as the world’s largest. But it ran into a series of technological and biological setbacks, including mass fish mortalities, system malfunctions, and rising operating costs—delays and disruptions that repeatedly pushed back production targets and rattled investor confidence. Across the space, none of these efforts reached more than about half to three-fifths of design capacity.

There’s also the physics problem. Total energy demands for fully land-based RAS production of Atlantic salmon are currently more than three times those of traditional sea pens.

So, for now, the fjords still look like Mowi’s advantage—hard to replicate, hard to permit, and hard to beat on cost. But land-based is the kind of threat you don’t get to ignore. If RAS gets its breakthrough—on reliability, cost, or energy—the competitive map could change fast.

VIII. Hamilton's 7 Powers and Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Now let’s sanity-check Mowi’s position with two lenses that work well together: Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers and Porter’s 5 Forces.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers

Cornered Resource (Strong): If Mowi has a true “you can’t copy this” advantage, it’s geography plus regulation. Norway has some of the best natural conditions for farming Atlantic salmon on the planet. The industry relies on fjords and coastal sea areas that belong to society, and aquaculture licences are issued by the state. Those licences grant a protected right to operate indefinitely—and because the state controls the supply of licences, it also controls who gets to scale.

Statistics Norway has identified substantial resource rent in aquaculture over several years, and it has risen strongly since 2012. That matters, because it’s essentially the definition of a cornered resource: something scarce that throws off persistent excess returns.

And the coastline itself is the ultimate non-replicable asset. Deep fjords, sheltered waters, and stable temperatures influenced by the Gulf Stream aren’t things a competitor can buy or build. Salmon farming has become one of modern Norway’s signature industrial success stories—starting in the late 1960s and, within 50 years, becoming the most important export industry next to oil and gas. Norway now produces around 1.3 million tons per year of salmon and trout, making it the world’s largest salmon producer.

Scale Economies (Strong): Mowi’s size shows up everywhere. As the world’s largest producer of Atlantic salmon, it accounted for about 20% of the global harvested salmon market share in 2024. That kind of volume lets Mowi spread the cost of R&D, breeding programs, feed innovation, and smart-farming technology across an output level few competitors can match.

Process Power (Medium): Mowi has put decades into genetics—selective breeding to create fish that grow faster and hold up better against disease than wild counterparts. The “Mowi Strain” is real process power, but it’s not invincible. Competitors can access similar genetic tools and breeding approaches, which limits how defensible this advantage is over the long run.

Branding (Emerging): The Mowi consumer brand is moving in the right direction, but it’s not yet an iconic household name. If it gets there, it changes the business: less commodity exposure, more pricing power, and a better margin profile. But for now, it’s still an advantage in progress.

Porter's 5 Forces

Supplier Power (Neutralized): Mowi’s feed move was a direct strike at supplier leverage. By building its own feed factories, it reduced what had been a major source of margin pressure. More broadly, Mowi is vertically integrated—from broodstock and genetic selection to farming, processing, and sales—which lowers dependence on any single upstream bottleneck.

Buyer Power (Medium): Retail giants like Walmart and Costco have real negotiating power, and salmon still sits in a category where shelf space and promotions matter. Mowi’s counter is scale plus brand: if it can be the supplier that reliably delivers volume, quality, and a consumer-recognized product, the balance shifts. And as salmon increasingly gets positioned as a premium protein, producers tend to have more leverage than they would selling a truly undifferentiated commodity.

Threat of New Entrants (Low): In Norway, you can’t just show up, raise capital, and start producing at scale. You need a licence. Beyond ordinary licences, there are various special purpose licences that make up about 21% of the total number of licences and 17% of total production capacity. The regime is designed to ensure orderly industry development—rights paired with obligations—and in practice, it blocks new large-scale entrants from building a meaningful position in Norway.

Threat of Substitutes (The Key Risk): This is the long-term pressure point. Land-based RAS systems, in theory, let you grow salmon anywhere with enough electricity and water. They’ve struggled so far, but if reliability and costs improve, the economics could shift. Beyond that, plant-based and lab-grown seafood alternatives continue to attract investment, even if they’re still far from being commercially competitive at scale.

Industry Rivalry (Moderate): The industry is competitive, but it’s no longer a free-for-all. Norwegian salmon has consolidated significantly, with Mowi, SalMar, Lerøy, and Cermaq controlling the majority of production. Licences issued from 1994 to 2020 increasingly went to larger enterprises—those holding more than six official licences—and the small-producer base has steadily been thinned out. That consolidation reduces chaos, but it doesn’t eliminate rivalry; it just concentrates it among a handful of very capable operators.

IX. The Playbook: Lessons for Builders and Investors

Mowi’s sixty-year arc is a reminder that “simple” industries can hide brutally complex strategy. A fish is not software. But the business forces around it—cycles, scale, regulation, supply chains, branding—are as real as anywhere else.

Consolidation in Fragmented Markets

The Fredriksen playbook travels well: find a cyclical market with too many subscale players, buy when the cycle is ugly, and consolidate until discipline becomes possible.

Salmon farming in the 80s and 90s was the textbook setup. Thousands of small operators, many sitting on a single license, all expanding at the same time when prices rose and all cutting at the same time when prices fell. No coordination, no supply discipline, and constant boom-bust economics. Fredriksen didn’t “discover” salmon. He recognized that structure, and he understood that if you could roll enough of the industry into one platform, the surviving scale players could earn real economic rents—especially once biology and regulation put a hard cap on growth.

The "Biology Discount"

Biological businesses trade at a discount for a reason: you can’t refactor nature.

The ISA crisis in Chile was the clearest demonstration. Years of buildup and investment can be wiped out in months when disease hits. That risk never goes away; it just gets managed. For investors, it’s the cost of admission. For operators like Mowi, it’s why so much effort goes into biosecurity, genetics, and spreading production across regions so a single outbreak doesn’t become an existential event.

Vertical Integration as Defense

Mowi’s move into feed is a case study in using vertical integration as a lever, not an identity.

Feed is the biggest cost line in salmon farming, and buying it from an oligopoly of suppliers meant living with someone else’s pricing power. Building its own capacity let Mowi lock down supply, tailor nutrition to its own fish, and keep more margin inside the system. But the December 2025 partnership with Skretting makes the point even sharper: integration isn’t a religion. If partnering produces better outcomes than owning, you partner. The goal is control over performance and economics, not ideological purity.

Regulatory Moats

Here’s the irony at the heart of modern salmon: stricter regulation has often made the incumbents stronger.

Researchers comparing salmon lice regulation across countries with wild salmon populations concluded that Norway runs the strictest regime. And that strictness has consequences. By limiting new licenses and constraining production growth, regulators effectively created a supply ceiling—one that made existing licenses more valuable and tilted economics toward the producers already inside the fence.

It’s a pattern you see in other resource industries too: regulation designed to protect the commons can, over time, harden the competitive moat around the companies operating in it.

Key Performance Indicators

If you’re watching Mowi going forward, two signals do most of the work:

-

Cost per kilogram (farming cost): This is the health-and-efficiency metric rolled into one. Mortality, feed conversion, growth rates, treatments, and operational execution all show up here. Mowi’s stated ambition is to be the best or second-best cost performer in every region it operates.

-

Harvest volume growth vs. the industry: The cleanest sign of whether Mowi is outperforming the biological and regulatory constraints is whether it grows faster than everyone else. In 2024, Mowi’s volume growth was 5.7% versus industry supply growth of 1.3%. For 2025, Mowi guided to 530k tonnes—another year of solid growth, again around 5.7%. Sustained outperformance here usually means the strategy is working and the biology is cooperating.

X. Conclusion: Bull vs. Bear

The Bull Case

Mowi finished 2024 on a heater: record quarter, record year, record harvest. Revenue hit EUR 5.62 billion, on 502,000 tonnes of salmon harvested. Even the seasonally strong fourth quarter set a new high, with 134,000 tonnes harvested.

Management’s pitch is that this isn’t a one-off spike; it’s the new baseline—especially as the company adds Nova Sea. CEO Vindheim put it like this:

"With Nova Sea on board, we expect our volumes to reach 600,000 tonnes next year, and we will be well on our way to harvesting 400,000 tonnes in Norway alone. Mowi was harvesting 375,000 tonnes globally as recently as 2018, so our volumes will have grown by 225,000 tonnes in just a few years. This corresponds to annual growth of 6.1% compared with 3.1% for the wider industry," said CEO Vindheim.

Then there’s the macro tailwind: the world needs more protein, and salmon sits in a sweet spot. It’s widely seen as one of the lowest-carbon animal proteins, and Mowi leans into that hard. The company says its salmon production saves the world 2 million tonnes of CO2e emissions annually by replacing the equivalent amount of land animal protein production.

On credibility, Mowi points to third-party rankings too. For the sixth year in a row, it topped the Coller FAIRR Protein Producer Index, which assesses major listed animal protein producers on environmental, social, and governance issues. In the bull case, Mowi isn’t just the biggest—it's one of the best-run operators in a category that’s only getting more important.

And finally, there’s the investor-friendly wrapper. Mowi pays a dividend—6.70 NOK per share annually, yielding 2.74%—and it pays it quarterly. For shareholders, that’s a tangible return while the company compounds volume, improves farming performance, and pushes further into branded products.

The Bear Case

The bear case starts with a truth we’ve circled all episode: biology does not care about your strategy deck.

Sea lice, algae blooms, and novel diseases are always in the background, and sometimes they’re in the foreground. On February 11, 2025, 27,000 farmed salmon escaped from a Mowi net-pen off Norway’s coast, triggering criticism from groups concerned about sea lice transmission and genetic dilution of wild populations. Incidents like that don’t just create operational headaches; they invite tougher regulation and reputational damage.

Then there’s politics. The resource rent tax may have been reduced to 25%, but it also introduced a new kind of uncertainty: if the state can take a bigger cut once, it can do it again. After the tax was introduced, several of Norway’s largest salmon companies responded by cutting planned investments. For an industry that needs constant reinvestment—in fish health, equipment, and technology—policy swings matter.

Land-based salmon remains the long-term wildcard. If RAS systems get dramatically more reliable and cheaper, the fjords lose some of their magic. Today, the economics still favor sea-cage farming, but the risk is that the cost curve bends unexpectedly.

And looming over everything is climate change. Even if some Norwegian regions see short-term benefits from gradual warming, the real risk is volatility: shifting currents, temperature swings, and acidification that change the rules of the water Mowi depends on.

Final Verdict

So which is it: a tech company disguised as a fish farm, or a commodity producer at the mercy of nature?

It’s both.

Mowi has built real, durable advantages—scale, vertical integration, scarce licenses in world-class waters, and a serious push into smart farming. It’s trying to do the hard thing in commodities: apply technology, discipline, and brand to pull itself out of pure price-taking.

But the business is still the business. It’s raising living animals in an open environment. Disease, parasites, storms, and ecosystem shifts can still blow holes in the plan. The “biology discount” exists because, sooner or later, biology collects.

For long-term fundamental investors, Mowi is a way to own a dominant player in a growing, sustainability-aligned protein category, with a dividend that pays you to wait. Just don’t confuse dominance with control. Even the King of Salmon still answers to the sea.

XI. Resources and Further Reading

If you want to go deeper on Mowi and the machinery behind modern salmon, here are three great places to start:

-

"Goldfinger – The History of Mowi" by Aslak Berge (available in English as of 2024) is the definitive corporate history—the closest thing to an origin story for how Mowi became Mowi.

-

The Mowi Salmon Farming Industry Handbook is written for analysts, investors, and anyone who wants a clear, grounded view of how the salmon market actually works. It’s published annually, packed with data on supply, pricing, and industry dynamics, and it’s widely treated as the sector’s reference guide.

-

Mowi’s integrated annual reports (on its investor relations website) are where the company lays out the details: operations by region, biological performance, strategy, and the financials that tie it all together.

Chat with

this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with

this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music