WiseTech Global: The Operating System for Global Trade

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

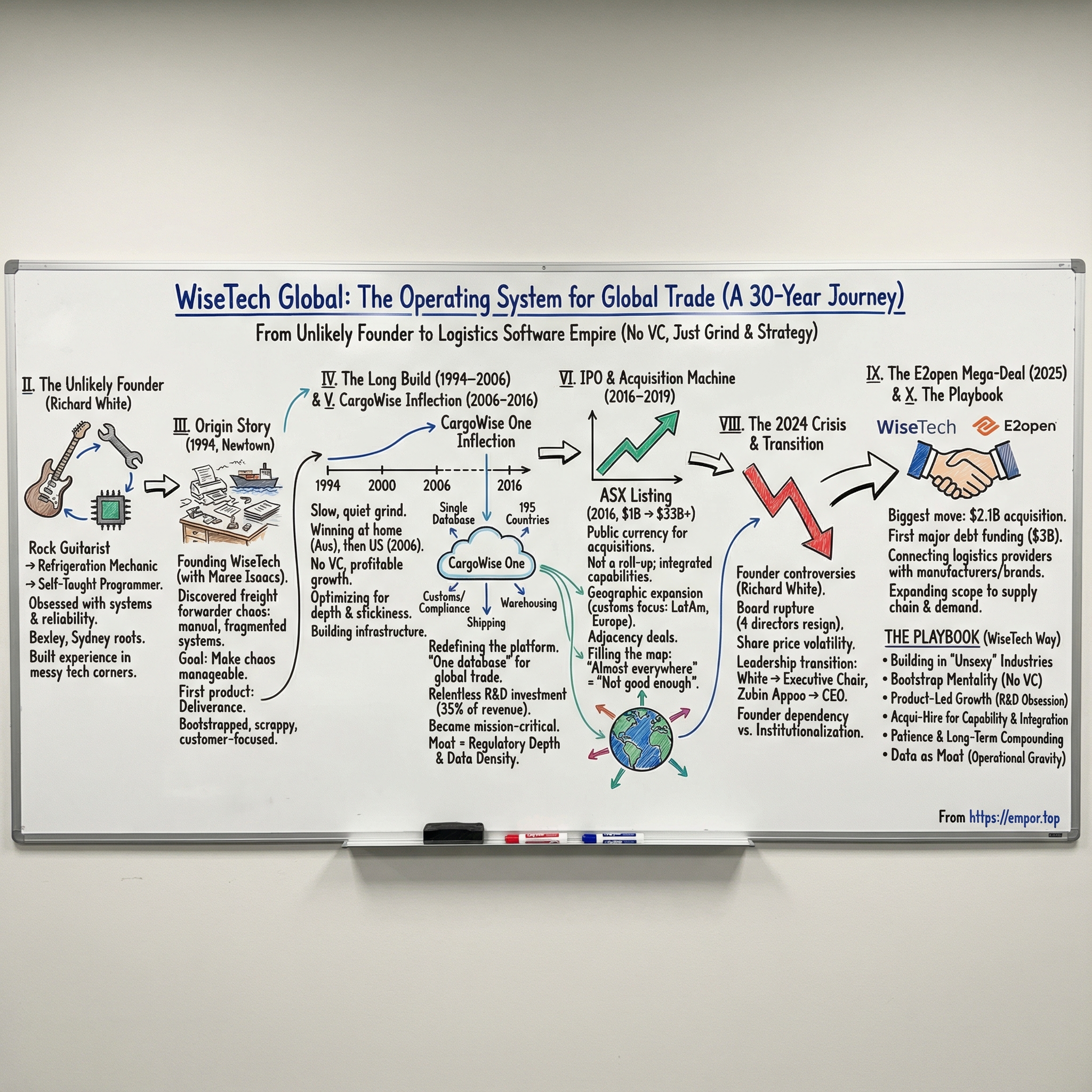

Picture this: somewhere in the world right now, a container ship is threading the Strait of Malacca. Another is being unloaded at the Port of Rotterdam. A freight forwarder in São Paulo is lining up customs clearance for auto parts headed to Detroit. In Singapore, a logistics manager is booking air cargo space to Hong Kong. And underneath all of it—the paperwork, the compliance, the tracking, the billing—there’s a single piece of Australian software most people have never heard of.

That’s WiseTech Global. Quite possibly the most important technology company you’ll never hear mentioned at a dinner party.

WiseTech listed on the ASX on 11 April 2016 at roughly a $1 billion valuation. By 2024, it had become the largest information technology company by market capitalization on the Australian Stock Exchange, valued at over $33 billion. Its core product, CargoWise, is so deeply embedded across global freight forwarding that it operates like a quasi-monopoly in mission-critical logistics execution.

So here’s the deceptively simple question at the heart of this story: how did a self-taught programmer from Sydney’s suburbs build a logistics software empire—without venture capital, without Silicon Valley’s blessing, and without much attention outside freight forwarding for almost two decades?

The answer takes us through an unlikely founder’s path from rock band guitarist to refrigeration mechanic to billionaire; an aggressively unsexy industry that turned out to be a goldmine; a 22-year grind before going public; and then, just when the company looked unstoppable, a corporate governance crisis that rocked WiseTech in 2024 and 2025. At its core, this is a story about patience, product obsession, and the strategic advantage of building infrastructure that becomes nearly impossible to replace once it’s installed.

WiseTech didn’t ride startup culture. It didn’t raise venture capital. It won by signing big, long-term enterprise contracts—and then reinvesting relentlessly into the product.

The themes we’ll follow cut against almost every modern tech cliché: the anti-VC path to a multi-billion-dollar outcome; “land and expand” executed over decades, not quarters; and the counterintuitive brilliance of building in a market so overlooked that, for years, nobody with a pitch deck even bothered to show up. And for investors, it’s also a reminder that the most defensible software businesses can still have a single point of failure—when founder risk becomes real.

II. The Unlikely Founder: Richard White's Journey

Every great company has a founder. WiseTech has one of the strangest—and most instructive—founder paths in modern business.

Richard White (born 1954 or 1955) grew up in Bexley, a working-class suburb in Sydney’s south. Long before anyone talked about incubators or venture capital in Australia, White was learning how real-world systems worked: his father ran an engineering business, his mother sold cookware through house parties, and as a kid he washed dishes for his grandparents’ wedding reception business. Not glamorous. But it’s where you absorb the basics of operations: customers, deadlines, cashflow, things breaking at the worst possible time—and the expectation that you just fix them.

This isn’t the familiar “prestige university dropout builds a startup” narrative. It’s a story about someone who got comfortable inside messy systems early, then built a career out of turning messy systems into working ones.

White graduated from Sydney Technical High School in 1972. Much later—remarkably—he completed a master’s degree in IT management in 2002. That timing matters. He didn’t spend his twenties collecting credentials. For most of his life, he was self-taught, learning by building.

And before he ever wrote software for global trade, he lived a completely different life: he played in a band called Jade, worked as a refrigeration mechanic, and even ran a guitar repair business called Rock Repairs. The connective tissue wasn’t music or appliances. It was an obsession with how things fit together—and how to make them run reliably. He taught himself electronics and programming while building lighting systems for bands, where failure is immediate and public: if the rig goes down, the show stops.

That mindset—systems have to work, in the real world, under pressure—would become a defining trait of WiseTech.

Before founding WiseTech Global, White built experience in the unsexy but vital corners of technology: computer consulting, systems integration, and distribution. He was CEO of Clear Group and a founder and managing director of Real Tech Systems Integration. These weren’t household names, but they were exactly the kinds of environments where you learn what businesses actually need from software: integration, reliability, and the ability to survive contact with reality.

Decades later, the institutions caught up to the work. In May 2023, the University of Technology Sydney awarded White a Doctor of Technology (Honoris Causa) for his contributions to information technology. He also became a Fellow of the university, a Luminarie, and an Adjunct Professor in the Faculty of Engineering & Information Technology.

But by the time the academic recognition arrived, the point was already proven: the self-taught mechanic and musician had built Australia’s most valuable listed tech company.

White has more than 35 years of experience in software development, embedded systems, and business management, and over 30 years of experience in freight and logistics. That combination—hands-on engineering instincts plus a deep feel for operational complexity—helps explain what comes next.

Because the through-line in his whole life is simple: find the chaos, build the system, make it unbreakable. And in 1994, he was about to stumble into one of the most chaotic industries on earth.

III. The Origin Story: Discovering the Chaos of Global Freight (1994)

WiseTech’s founding story starts in Newtown, Sydney, in 1994—before the dot-com boom, before “cloud” meant anything other than weather, and before software-as-a-service became a business model. In logistics offices, the infrastructure of global trade was still powered by paper, faxes, phone calls, and patched-together systems that barely spoke to each other.

Richard White founded WiseTech Global on 1 October 1994. And from the beginning, it wasn’t a solo act. Maree Isaacs co-founded the company with him in 1994 and became an Executive Director in 1996.

The spark came from an unlikely customer set: freight forwarders. If you’ve never dealt with one, think of them as travel agents for cargo. They buy capacity on ships and planes from carriers, consolidate shipments from many customers, and then sell that bundled movement as a door-to-door service. That sounds straightforward until you remember what’s hiding underneath: quotes, bookings, handoffs, warehousing, insurance, customs declarations, compliance, billing, and constant exceptions. It’s relationships and paperwork layered on top of relentless complexity.

White encountered this world through his technology consulting work—and what he found was the kind of mess that creates a very specific kind of opportunity. Forwarders weren’t short on software. They were drowning in it. Tiny tools that did one job each: one for customs, another for tracking, another for accounts. Nothing integrated. No single source of truth. No “system” at all—just a pile of workarounds that everyone tolerated because there wasn’t a better option.

To understand why this was such a big deal, you have to understand the stakes. Forwarders sit between shippers who need goods moved and carriers who have capacity. They earn their margin by being the efficient counterparty—by getting it right, every time, across borders, across time zones, across rulebooks that don’t match. In 1994, much of that work was still manual. People flipped through binders of codes, typed declarations, sent faxes, and chased shipment status by phone. And when something went wrong, it didn’t just create annoyance—it created delays, storage costs, penalties, and stranded cargo.

So WiseTech built software to make that chaos manageable.

The first product was called Deliverance. It was the seed that would eventually grow into CargoWise—the platform that became WiseTech’s core. The ambition was simple and quietly radical: take an industry running on fragments and stitch it into something integrated enough to run a real operation.

And just as important as what WiseTech built was how it got built.

No venture capital. No hype cycle. No “growth at all costs.” The early days were famously scrappy—White has described founding the business from a basement in Newtown, with colleagues and a credit card. That constraint shaped the culture. When you’re building on customer money and personal risk, you don’t get to ship features for vanity. Every improvement has to earn its place. Every hire has to matter. Survival forces clarity.

Isaacs’ role matters here. White brought the technical vision and the instinct for systems. Isaacs brought operational discipline and deep experience across business operations, account management, customer service, and quality assurance—exactly the muscles you need if your product is going to be used by logistics professionals who don’t have time for software that’s theoretically elegant but practically painful. She helped ensure the company wasn’t just building software that worked, but software that worked in the trenches.

And from the start, WiseTech made a focus decision that would become one of its most powerful strategic advantages: go deep on logistics, not wide across “enterprise software.” Where others built general-purpose platforms and bolted on logistics as a module, WiseTech committed to mastering the nuances—customs authorities, compliance rules, languages, currencies, the whole messy reality of global freight. It was a bet that depth would beat breadth.

In 1994, that might have sounded limiting. In hindsight, it was the wedge. Because if you could become the system that freight forwarders trusted to run their day—accurately, globally, and at scale—you wouldn’t just have a product.

You’d have infrastructure.

IV. The Long Build: From Australian Freight to Global Ambition (1994–2006)

What came after the founding was the part most startup stories skip: the long, quiet stretch where nothing looks inevitable. For more than a decade, WiseTech just kept shipping, selling, and fixing real customer problems—one freight forwarder at a time.

By 2000, the company had become established in the Australian logistics industry. In 2006, it made the jump into the US market, taking the CargoWise name with it.

That timeline is the point. Six years to truly win at home. Another six to be ready to go abroad. While most tech companies are trained to chase acceleration, WiseTech was building something that couldn’t afford to break. Freight doesn’t pause because your software has a bad day.

Those years in the trenches explain almost everything about what came later. WiseTech wasn’t optimizing for headlines or valuation. It was optimizing for depth—features that actually worked in operations—and for stickiness. Every new customer didn’t just add revenue; it added learning. Every workflow they automated made the system harder to replace. Switching costs weren’t a strategy deck bullet point. They were the natural outcome of years of becoming the system of record.

A key choice during this era was architectural, and it was defining: WiseTech wanted a platform, not a pile of parts. In logistics software, plenty of competitors grew by buying point solutions—a customs tool here, a tracking module there—then trying to stitch them together. Users got a patchwork. The vendor got technical debt.

WiseTech took the slower path. Build from the ground up, on a single database, with one underlying architecture—so freight forwarding, customs, warehousing, accounting, and compliance could all live inside the same system, sharing the same data. It’s harder. It takes longer. But when it works, it produces something competitors struggle to copy: a product where every piece naturally connects to every other piece.

The company also lived through the kinds of moments that wipe out fragile businesses. The dot-com crash hit in 2000–2001. The global financial crisis followed in 2008. Periods like that are when venture-backed startups often get cornered—funding dries up, boards demand pivots, and the runway vanishes.

WiseTech’s model was different. It was bootstrapped and profitable. It didn’t need to convince investors to keep believing; it needed to keep customers getting value. If the software saved time, reduced errors, and kept freight moving, customers paid. If customers paid, WiseTech kept building.

So by the time 2006 arrived, WiseTech didn’t just have ambitions for global expansion—it had earned the right to try. It had a product hardened by years of operational reality, and a culture built around sustainable growth instead of sprinting for the next round.

And there’s a broader lesson hiding in that slow timeline. WiseTech’s moat wasn’t created by a flashy launch or a clever growth hack. It compounded—quietly—through years of product development, customer feedback, and accumulated domain knowledge. That’s what real defensibility often looks like: not a moment, but a decade.

V. The CargoWise One Inflection: Redefining the Platform (2006–2016)

The decade after WiseTech’s U.S. push was the stretch where the company stopped looking like “good Australian logistics software” and started looking like a global platform. The big shift was the evolution from ediEnterprise into CargoWise One—a redefinition of what a freight forwarder’s core system could be.

At the heart of CargoWise One is a deceptively simple promise: logistics service providers can run freight forwarding, customs clearance, warehousing, shipping, land transport, and cross-border compliance in one system, on one database—across countries, languages, currencies, users, and functions.

That “one database” line is doing a lot of work. In logistics, different countries don’t just have different preferences. They have different legal requirements, different data formats, different customs processes, different tax rules, and different ways of changing those rules with very little notice. Building a unified platform that can handle all of that isn’t just hard engineering—it’s a never-ending race against real-world complexity.

The product vision, though, was clean: instead of forcing logistics companies to stitch together separate systems for different regions and functions, CargoWise would become the single source of truth. Enter a shipment once, and the system could drive the downstream steps: documentation, compliance checks, handoffs, billing—everywhere that shipment needed to go.

As CargoWise One matured, it became less a piece of software you installed and more a critical link in the global supply chain. WiseTech has said the platform executes over 44 billion data transactions annually. And the company’s identity became inseparable from the idea of relentless iteration: not shipping a “version” and maintaining it, but continuously expanding and refining it.

That pace matters competitively. In enterprise software, rivals can copy features. What’s harder to copy is momentum. WiseTech turned product development into a moving conveyor belt. By the time a competitor matched one set of capabilities, CargoWise had already pushed forward—more compliance coverage, more automation, more edge cases handled.

That approach required real spending, and WiseTech leaned into it. In FY24, the company reinvested 35% of revenue back into R&D, and said 62% of its global workforce was focused on product development. In that same year, it delivered 1,135 new product enhancements, bringing the five-year total to more than 5,600—off the back of more than $1.1 billion of R&D investment over that period.

The payoff of that grind wasn’t just “more features.” It was a moat built out of accumulated regulatory depth. CargoWise operates across 195 countries, and staying useful means staying current as customs authorities update requirements. In this world, accuracy is the product. A single mistake in a customs filing can delay cargo, trigger fines, and damage a forwarder’s relationship with its customer. So once a system proves it can be trusted—at scale, across borders—customers become extremely reluctant to rip it out.

This is also where WiseTech’s network effects start to look different from the usual tech story. CargoWise doesn’t become more valuable because your friends use it. It becomes more valuable because it processes more real transactions, encounters more real exceptions, and learns more real-world edge cases than any single customer ever could on their own. Data density turns into operational advantage.

WiseTech has claimed that its software touches 55% of global manufactured trade flows. If that’s even close to right, it implies a level of visibility that few companies on earth possess. Patterns emerge. Bottlenecks repeat. Compliance risks show up before they explode into problems. And the platform can keep getting smarter, not in theory, but in the very specific ways that matter when you’re trying to move physical goods through an imperfect world.

By the time WiseTech reached 2016, CargoWise was no longer just a product line. It looked like infrastructure—something global trade quietly depended on, and something that would be brutally painful to replace.

VI. The IPO and the Acquisition Machine (2016–2019)

By the time WiseTech hit the public markets, it had already done the hard part: it had survived, it had won real customers, and it had built a product that was starting to look like infrastructure.

The company converted from WiseTech Global Pty Limited into a public company on 4 September 2015. Then, on 11 April 2016—twenty-two years after Richard White and Maree Isaacs started the business in Newtown—it listed on the ASX.

That 22-year run-up matters. In venture-backed tech, founders are often pushed toward an exit in seven to ten years. WiseTech took the opposite path: slow, profitable, compounding—then public.

In the IPO, WiseTech priced at A$3.35 per share, raised about $168 million, and debuted with a market value just under A$1 billion. When trading began around midday local time, the stock opened at A$3.41—up from the IPO price—and climbed as much as 14% on the day, even as the broader ASX 200 finished slightly down.

Investors had reasons to be cautious. Plenty of tech IPOs had a familiar pattern: go public too early, lose money loudly, disappoint predictably. WiseTech looked different for a simple reason: it wasn’t a story about potential. It was already a functioning business—large, global, and profitable. In the six months ended 31 December 2015, it reported revenue of A$48.59 million and net profit of A$3.12 million.

But the IPO wasn’t about keeping the lights on. It was about adding a new weapon.

Public stock gave WiseTech a liquid currency for acquisitions. And once it had that currency, it started buying—fast.

Over time, WiseTech has completed dozens of acquisitions across more than 20 countries, spanning multiple adjacent categories within logistics software and services. The busiest stretch came a couple of years after listing: 2017 and especially 2018, when it did a flurry of deals. This wasn’t random empire-building. It was a deliberate attempt to fill in the missing pieces of a single, global platform.

WiseTech’s acquisition thesis fell into two buckets.

The first bucket was geographic expansion—most often through customs and border compliance. This is one of the most important nuances in the whole WiseTech playbook: you can’t “platform” your way into customs from a desk in Sydney. Customs is local. It’s language, relationships, and the lived experience of how regulators actually behave. By acquiring established customs software providers in specific markets, WiseTech could plug real, proven capability into CargoWise far faster than building it from scratch.

The second bucket was adjacency: buying specialist capabilities that made CargoWise broader and stickier. A warehouse tool here, a dangerous goods compliance product there—tuck-ins that gave existing CargoWise customers more reasons to standardize on one system, and gave WiseTech more entry points into new workflows.

Just as important as what WiseTech bought was what it tried not to buy. The company has said it prefers businesses that have grown organically, and tends to avoid companies that have grown through acquisitions and aren’t fully integrated. That’s a quiet rejection of the classic roll-up model. Roll-ups often come with messy product suites, brittle integrations, cultural fragmentation, and customers who are already tired of “the next migration.” WiseTech wanted the opposite: clean capabilities it could absorb, unify, and scale.

And it didn’t run the private equity script. There was no “strip costs and harvest cash.” WiseTech’s line is closer to: we don’t buy companies and cut costs; we buy companies and grow costs—because the whole point is to invest, build, and integrate those capabilities into the platform.

In 2018, for example, WiseTech acquired the Swedish logistics solutions provider CargoIT, following deals including IFS Global Holdings, LSI Sigma Software, and Trinium Technologies. The names aren’t famous. That’s the point. These were the kinds of niche, domain-specific businesses that—once folded into CargoWise—made the overall system harder to replicate and harder to replace.

And that machine kept compounding. By FY24, WiseTech was reporting total revenue of AUD $1,041.7 million, up from AUD $816.8 million in FY23, including a 33% increase in revenue in its CargoWise segment. The bigger story wasn’t just acquired revenue showing up in the numbers. It was the flywheel: acquired capability made CargoWise more valuable, which deepened customer relationships, which helped win new customers, which funded more product and more acquisitions.

WiseTech went public with a product that already looked like infrastructure. Then it used the public markets to turn that infrastructure into a global operating system—one country, one compliance regime, one workflow at a time.

VII. The Global Expansion: Filling the Geographic Map

The logic behind WiseTech’s geographic expansion was simple, and quietly brutal: in global trade, “almost everywhere” is the same as “not good enough.” If goods cross borders, your software has to understand borders. A forwarder moving electronics from Shenzhen to São Paulo needs a system that can handle Chinese export documentation, Brazilian import requirements, and whatever customs steps sit in between. Any missing country coverage isn’t a feature gap. It’s a failure point.

So WiseTech started filling in the map the way you’d expect a platform company to do it: buy deep local capability, then plug it into the global system.

WiseTech Global acquired three leading logistics solution providers across Latin America and Europe: Forward, Softcargo, and EasyLog. Forward, based in Argentina, and Softcargo, based in Uruguay, together covered 16 countries across Latin America. EasyLog brought a major piece WiseTech needed in Europe: French customs solutions. Forward and Softcargo expanded the group’s Latin American footprint; EasyLog strengthened its customs position in France.

Latin America, in particular, was exactly the kind of region where WiseTech’s approach paid off. The complexity—different customs regimes, shifting regulatory requirements, currency controls—makes it hard for a generic platform to compete. By acquiring Bysoft in Brazil, Forward in Argentina, and Softcargo in Uruguay, WiseTech assembled coverage across 16 Latin American countries in a way that was hard to replicate quickly.

Europe followed the same playbook, just with different constraints. Even inside the EU’s common market framework, each country has its own quirks, processes, and expectations. And once you add non‑EU countries like Switzerland and the UK, the differences become even sharper. WiseTech’s acquisitions across Belgium, the Netherlands, Ireland, Germany, Italy, and France weren’t about headlines. They were about stitching local expertise into a single platform that could run a forwarder’s operation end-to-end.

That expansion shows up in who uses the product. WiseTech said its customers included more than 16,500 logistics companies across 195 countries—covering 46 of the top 50 global third-party logistics providers and 24 of the 25 largest global freight forwarders.

Those numbers matter because they create momentum that feeds itself. When nearly every major forwarder is on the same system, the rest of the market pays attention. Mid-sized players look up-market and see what the giants are using. And internal IT teams often reach the same conclusion: if it’s trusted at global scale, it’s safer than betting on something unproven.

WiseTech counts customers like DHL, FedEx, Kuehne+Nagel, and DB Schenker among the users of CargoWise.

And the common thread through all of this is customs. In most industries, compliance is a cost—something you endure. In logistics, compliance is the product. A freight forwarder that clears shipments faster, with fewer errors, has a real operational advantage. By building customs and border compliance capabilities market by market, WiseTech turned regulatory complexity into a moat.

CargoWise processes tens of millions of transactions annually and maintains millions of product classifications, compliance updates, and trade documents across jurisdictions.

None of that work is glamorous. But it’s compounding. Maintaining those classifications and updates doesn’t just improve the software—it builds institutional knowledge about how customs authorities actually work in practice: edge cases, enforcement patterns, and the messy reality that doesn’t show up in the rulebook. And that kind of knowledge, accumulated over years of real transactions, is one of the hardest things for a new competitor to catch up to.

VIII. The 2024 Crisis: Founder Controversies and Leadership Transition

Every great company story has its crisis. For WiseTech, that crisis arrived in late 2024—and it revolved around the same person who had shaped nearly every chapter before it: Richard White.

In October 2024, White stepped down as CEO amid allegations of sexual and corporate misconduct. He didn’t disappear, though. He remained as chair of the board, keeping a formal role at the very top of the company he’d led for three decades.

The allegations were messy, public, and serious. Media reports described claims about White’s relationships with several women, including allegations of quid pro quo arrangements involving promises of business investments and extravagant gifts, including a mansion reportedly worth around $13 million. Another report described White serving a bankruptcy claim for about $91,000 against wellness influencer Linda Rogan after their alleged relationship ended. Rogan said she had used the funds to furnish a mansion White had purchased for her in Sydney’s Vaucluse, before White’s partner, Zena Nasser, found out about the relationship.

For a company that had spent decades building a reputation for operational rigor, the sudden shift into tabloid territory was jarring. The market reacted quickly. WiseTech’s share price fell more than 20% in the week after reports by Nine about relationships White reportedly had with female employees and other women outside the company.

But the headlines weren’t the whole story. What followed inside the company was even more destabilizing.

In January 2025, White came under further scrutiny after additional reports of inappropriate behaviour toward several women. Then, in February 2025, the situation escalated into a full-blown boardroom rupture. Most of the board—including chair Richard Dammery—resigned, citing “intractable differences” over White’s future. The share price fell nearly another 20% on the announcement, before recovering somewhat after WiseTech announced White would become Executive Chair.

The resignations were sweeping: Dammery, Lisa Brock, Fiona Pak-Poy, and Michael Malone all exited at once. That left just two directors: Charles Gibbon, who had previously chaired the board for 12 years, and WiseTech co-founder Maree Isaacs.

Four out of six directors leaving in a single stroke is the kind of event that forces a company into a different category. It wasn’t just a leadership reshuffle—it was a governance shock, especially because many of those departing directors were independent. Overnight, WiseTech looked less like a scaled public company and more like a founder-controlled business again.

And in practice, that’s what it was.

White’s roughly 37% stake—built through decades of patient ownership rather than dilutive fundraising—became the ultimate lever. He owned enough of WiseTech that even unified board opposition couldn’t truly sideline him. The same structure that had protected WiseTech from short-term market pressure now limited the ability of other stakeholders to impose accountability when the company was under stress.

WiseTech later cleared White of bullying and intimidation allegations. He stayed on as a consultant at his former salary, and in February 2025 he was appointed Executive Chair.

This is the founder-dependent company problem in its purest form. WiseTech’s product strategy, acquisition engine, and culture all carried White’s fingerprints. Investors had long believed that alignment was an advantage. In 2024 and 2025, the same dependency became a risk: what happens when the visionary becomes, in the eyes of customers, employees, directors, and major shareholders, a liability?

One consequence was high-profile institutional discomfort. The broader crisis—board resignations, governance concerns, and share volatility—was serious enough that AustralianSuper, Australia’s largest pension fund, sold its stake in WiseTech. When a shareholder like that walks away, it’s not about quarter-to-quarter performance. It’s a signal that governance has become too costly to underwrite, even if the business fundamentals remain strong.

Stabilization finally came with a permanent CEO appointment.

In July 2025, WiseTech named Zubin Appoo as Chief Executive Officer, effective immediately, after an internal and external search. He replaced Andrew Cartledge, who had served as interim CEO since October 2024. Cartledge—who had also been CFO since 2015—was set to retire at the end of calendar year 2025, and remained to support the transition.

Appoo wasn’t a stranger. He had spent 14 years at WiseTech from 2004 to 2018, serving as head of innovation and technology, and had been part of the team that developed CargoWise. His appointment was widely seen as an attempt to connect WiseTech’s founding DNA with a steadier, more durable operating structure. As eToro market analyst Josh Gilbert put it, Appoo’s elevation allowed WiseTech to “draw a line under recent boardroom drama” and gave the business a clearer leadership structure moving forward.

The arrangement that emerged was a compromise: White as Executive Chair focused on product and innovation; Appoo as CEO responsible for operations and execution. It was an effort to preserve what White uniquely brought to WiseTech while restoring clearer accountability after months of turmoil.

Whether that balance holds—whether it can satisfy customers, employees, regulators, and investors while keeping the product machine moving—would become one of the defining questions of the next era of WiseTech.

IX. The E2open Mega-Deal: Betting Big on the Future (2025)

Even as the governance drama was playing out in public, WiseTech wasn’t pausing on strategy. In May 2025, it announced the biggest move in its history—an acquisition so large it didn’t just add another module or another country. It pulled WiseTech into an adjacent universe.

The target was E2open Parent Holdings, Inc., a connected supply chain SaaS platform built around a large multi-enterprise network. The deal terms were straightforward: e2open shareholders would receive $3.30 per share in cash, valuing the business at an enterprise value of $2.1 billion.

How WiseTech planned to pay for it was the real headline.

The acquisition price, transaction costs, and working capital requirements were funded through a new, fully underwritten debt facility totalling $3.0 billion. The facility was structured as a syndicated package, split into multiple tranches with maturities stretching out to five years.

For a company that had spent three decades preaching discipline, profitability, and reinvestment, this was a genuine shift. WiseTech had always used the public markets as an acquisition currency through its equity. This was its first meaningful embrace of leverage. A $3 billion debt facility to fund a $2.1 billion deal is not “tuck-in M&A.” It’s a bet.

E2open, founded in 2000, is headquartered in Addison, Texas and operates in more than 20 countries. Its pitch is connecting the companies that make things with the companies that move them and sell them. In e2open’s network, more than 500,000 manufacturing, logistics, channel, and distribution partners are linked together, with the platform tracking over 18 billion transactions annually.

Strategically, the logic was clear. Until this point, WiseTech’s customer base skewed heavily toward logistics service providers—freight forwarders, customs brokers, and 3PLs. E2open brought something different: the “principals” of trade. Manufacturers. Brand owners. Importers and exporters. The companies that generate demand, plan production, and manage inventory—not just the ones who book and clear freight.

WiseTech framed it as an expansion of its scope into global and domestic trade: demand, planning, channel, supply, transportation, and logistics for buyers, shippers, manufacturers, and brand owners. In other words, it wasn’t just strengthening the freight-forwarding operating system. It was moving upstream and downstream to cover a much larger portion of the trade lifecycle.

This is the connective ambition in its most literal form: bring the logistics operators and the companies they serve onto a single, electronically connected network—turning a best-in-class execution system into something closer to a multi-sided marketplace.

The acquisition completed in August 2025. On 4 August 2025, WiseTech took 100% ownership of e2open.

WiseTech positioned the combination as additive to the network effects story: hundreds of thousands of additional enterprises brought into the broader ecosystem, pushing the “operating system for global trade and logistics” line from vision statement toward real platform gravity.

But the cost of that gravity showed up immediately in the numbers WiseTech guided to.

For FY26, WiseTech expected EBITDA margin to land around 40% to 41%, and FY26 EBITDA of $550 million to $585 million—strong growth, but with profitability stepping down from WiseTech’s historically premium margins. The reason wasn’t mysterious: integration costs, debt servicing, and the simple reality that e2open ran at lower margins than CargoWise.

For long-time shareholders used to WiseTech’s high-50s margin profile, this looked like a deliberate decision to trade near-term elegance for long-term scope.

WiseTech could point to its integration track record—more than 50 acquisitions over time, including niche capabilities like Hazmatica for dangerous goods compliance and Neo for freight management. But e2open wasn’t another niche capability. It was a different kind of challenge: big, complex, and meaningful enough to change what WiseTech was.

That’s where the real investor question sits. Morningstar has highlighted switching costs as one of WiseTech’s most important advantages, pointing to annual retention rates above 99% for CargoWise since 2013, even as the company implemented significant price increases.

CargoWise is famously hard to rip out because it becomes the system of record for operations and compliance. The open question is whether WiseTech can create that same “mission-critical, can’t-live-without-it” dependency across e2open’s customer base—and whether it can do it while integrating a business of this scale.

If WiseTech can apply its playbook—deep product investment, long-term integration, and relentless focus on workflows—to e2open, the deal could cement its position as the operating system for global trade. If integration friction shows up as customer churn, or if the complexity dilutes execution, this purchase could become an expensive distraction at exactly the moment WiseTech needed steadiness most.

X. Playbook: The WiseTech Way

After three decades of building, WiseTech’s playbook comes into focus. And it’s almost the mirror image of what a lot of modern tech culture teaches: fewer shortcuts, more depth; less hype, more compounding. If you want to understand how an “overnight success” takes 30 years, it’s in these choices.

Building in "Unsexy" Industries

Logistics software is nobody’s idea of glamorous. There are no viral loops. No consumer fandom. No launch-day hype. It’s invoices, compliance codes, customs forms, and the operational reality of moving physical goods.

That “unsexy” nature was the opportunity. While venture capital mostly ignored freight forwarding, WiseTech had room to build patiently. It didn’t need to win a press cycle—it needed to win workflows. And by the time the market started paying attention, WiseTech had already dug in deep and established leadership.

WiseTech’s journey is unique for another reason: it was built without venture capital funding. It didn’t rely on startup culture. It focused on securing large, long-term enterprise software contracts—exactly the kind that don’t make great headlines, but do build durable businesses.

The Bootstrap Mentality

No VC funding. No “growth at all costs.” Just sticky enterprise contracts and, for long stretches, very high EBITDA margins.

The lack of venture capital wasn’t a handicap—it was freedom. There was no clock forcing a premature exit, no fundraising treadmill, no outside pressure to prioritize speed over correctness. WiseTech could take twelve years to build locally before pushing internationally, because it was optimizing for the long run: trust, depth, and mission-critical dependence.

Product-Led Growth

WiseTech’s stated ambition is to be “the operating system for global trade and logistics.” The way it pursues that ambition is simple: keep building.

WiseTech has described itself as product-led, investing around a third of revenue into product development year after year. The logic is straightforward: deepen value for existing customers, attract new ones in the markets it already serves, and expand what the platform can cover.

What makes this unusual is the consistency. Many software companies reduce R&D intensity as they mature. WiseTech leaned in, treating product investment as the growth engine, not a line item to be optimized away.

WiseTech has invested nearly $1.1 billion in R&D over five years, and around 62% of its employees have been focused on the product. That staffing mix tells you what the company believes: distribution matters, but the product is the strategy. And for competitors, it sets a daunting bar—catching up isn’t about copying a feature list. It’s about matching years of sustained investment and domain-specific execution.

The Acqui-Hire Philosophy

WiseTech’s acquisition approach also runs against the typical M&A stereotype. It hasn’t pitched itself as a cost-cutting roll-up. Instead, it buys to gain capabilities—then invests to grow and integrate them.

A recurring internal belief is that culture matters to whether integration works. WiseTech has said aligned businesses integrate more smoothly, and that strong culture shows up in committed senior leaders—especially in product—along with good tenure and low attrition.

That emphasis isn’t fluffy. In software, the real asset often walks out the door every evening: the engineers who understand the code, the product leaders who know what customers actually need, and the people with the relationships that make customers stay through change. WiseTech’s view is that the best acquisitions are the ones where those people stick around and keep building.

Patience and Long-Term Thinking

WiseTech took twenty-two years from founding to IPO. It spent years getting established in Australia before expanding internationally. And it has treated product development as an ongoing, multi-year compounding loop—not a sprint from release to release.

In logistics, that patience becomes a competitive weapon. Relationships take time. Trust takes time. Switching costs take time. WiseTech was willing to wait for all three to solidify.

Data as Moat

WiseTech has claimed its software touches 55% of global manufactured trade flows. If you process that much activity, you don’t just run workflows—you accumulate a map of how global trade actually behaves.

That data becomes advantage in the places that matter: better compliance automation, better handling of edge cases, better identification of risk patterns deep in the supply chain. A new entrant can hire engineers and build interfaces. What they can’t buy quickly is years of transaction history and the institutional knowledge embedded in it.

And that’s the core of the WiseTech way: pick the messy, overlooked problem; build the system that has to work; reinvest relentlessly; and let time do what time does best—compound.

XI. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

1. Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Yes, there are credible software companies in and around this space—names like Descartes Systems Group and Manhattan Associates come up often. But CargoWise sits in a different category: it’s the system many of the world’s biggest forwarders already run their businesses on.

To compete head-on, a new entrant would need to do far more than build a clean UI and a few useful modules. They’d need to replicate years of regulatory and operational coverage across roughly 195 countries, earn trust with freight operators who can’t afford outages or errors, and keep pace with constant rule changes in customs and compliance.

That’s why WiseTech’s moat isn’t just “good software.” It’s the compounding effect of sustained product investment at scale. Over the past five years, WiseTech invested around $1 billion in R&D, delivered more than 5,700 product enhancements, and kept expanding CargoWise’s functional and geographic reach. With roughly 62% of staff focused on product, it’s hard for smaller competitors to keep up—and hard for a brand-new player to even get to the starting line without spending billions over many years.

CargoWise also benefits from sheer real-world usage. It processes tens of millions of transactions annually and maintains millions of product classifications, compliance updates, and trade documents across jurisdictions. That operational breadth is incredibly difficult to recreate without already being embedded in the global freight system.

2. Bargaining Power of Buyers: LOW to MODERATE

On paper, the buyers are large and sophisticated: major freight forwarders and logistics providers with procurement teams and real negotiating power. In practice, CargoWise flips the dynamic because it becomes mission-critical infrastructure.

WiseTech has pointed to annual gross retention of over 99% since 2013—even while pushing through steep price increases. When customers stick around at that level despite higher pricing, it’s a signal that the software isn’t “nice to have.” It’s deeply wired into daily operations.

And the alternatives aren’t as simple as “pick another vendor.” In many cases, the real competition is in-house systems and manual or semi-manual processes—tools that might work locally, but struggle at global scale. Switching away from CargoWise means retraining teams, rebuilding integrations, migrating data, and risking compliance errors mid-transition. For forwarders, that risk profile usually dwarfs any potential savings.

So buyers have some leverage at the negotiating table, but far less leverage in the ultimate decision of whether to leave.

3. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

WiseTech largely builds its software in-house and controls its core intellectual property. It doesn’t rely on a small set of critical component suppliers that can dictate pricing or terms. Its key “inputs” are people—engineers and product talent—and the company has historically invested heavily in building that internal capability.

4. Threat of Substitutes: LOW to MODERATE

Substitutes exist, but they tend to come in two imperfect forms.

One is the mega-suite: ERP and supply chain modules from vendors like SAP and Oracle. These can cover pieces of logistics, especially for companies where logistics is just one department among many.

The other is niche software: strong point solutions that do one job well, like a specific customs workflow or a warehouse capability.

WiseTech’s advantage is that it stays focused on logistics execution end-to-end—customs, compliance, freight forwarding, warehousing, transport, visibility—built to work together. For organizations where cross-border movement is the business, not a supporting function, a general-purpose module typically lacks the depth and specificity that day-to-day operations demand.

5. Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

Competition is real, but it’s fragmented. Descartes has strength in areas like customs and compliance. Manhattan Associates is known for warehouse and inventory management. SAP and Oracle cover logistics as part of broader enterprise platforms.

What’s harder to find is a single rival offering the same globally integrated, one-platform approach that CargoWise provides across freight forwarding and compliance. So while there are plenty of competitors around the edges, CargoWise remains the market leader in the category it has defined.

XII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: STRONG

Over the past five years, WiseTech invested roughly $1 billion in R&D, shipped more than 5,700 product enhancements, and kept expanding CargoWise’s functional and geographic coverage. That’s what scale looks like in enterprise software: the ability to out-build smaller competitors, then spread the cost of that build across a global customer base.

The expensive part isn’t just writing code. It’s maintaining accurate, always-current compliance content across roughly 195 countries, and doing it in a way that doesn’t break customers’ operations. Those are massive fixed costs. WiseTech can amortize them over thousands of customers; most rivals can’t, which caps how fast they can innovate and how broad they can go.

2. Network Effects: STRONG

WiseTech’s network effects don’t look like social media. They look like operational gravity.

As more logistics providers run more real shipments through CargoWise, the platform sees more exceptions, more edge cases, more documentation patterns, more compliance changes in the wild. That growing volume of real-world operational data helps improve automation, accuracy, and workflow efficiency. And when you’re dealing with customs and cross-border complexity, those improvements compound: better data makes the system more reliable, which makes it more trusted, which keeps customers anchored, which feeds even more data back into the platform.

3. Counter-Positioning: STRONG

WiseTech made a choice that looks obvious only in hindsight: it went all-in on logistics.

That focus created a position that generalist competitors struggled to attack. Companies like SAP and Oracle could have built truly deep logistics execution and compliance tooling, but doing so would have pulled attention and investment away from their core ERP platforms—and required a level of logistics-specific domain depth that doesn’t naturally fit their business model. WiseTech, meanwhile, didn’t have to balance priorities. Logistics was the whole game.

4. Switching Costs: VERY STRONG

WiseTech’s retention rate—above 99%—isn’t just a nice metric. It’s the clearest proof that CargoWise becomes infrastructure.

Once CargoWise is implemented, it doesn’t sit on the edge of the business. It becomes the system of record for shipments, compliance processes, customer and carrier integrations, and often the connections into finance and billing. Switching isn’t “changing vendors.” It’s rewiring the operational nervous system of a freight business while freight is still moving.

That’s why low churn is such a powerful barrier here. Even customers with legitimate complaints usually conclude that ripping it out is riskier than working through the issues.

5. Branding: MODERATE

Inside logistics, CargoWise is widely recognized and respected. But this is enterprise software, not consumer tech. Brand matters, just not as much as trust earned through uptime, accuracy, and references from other operators.

CargoWise’s “brand” is less a logo and more a reputation: it works, it’s comprehensive, and the biggest players rely on it.

6. Cornered Resource: MODERATE to STRONG

WiseTech’s cornered resource is accumulated know-how—especially around customs and compliance.

Over three decades of processing transactions, WiseTech has built up an institutional understanding that’s hard to duplicate quickly: the edge cases that break naive systems, the practical realities of how different jurisdictions operate, and the deep compliance content that has to stay correct as rules change. Competitors can spend money to build software, but they can’t easily buy decades of lived operational learning.

7. Process Power: STRONG

WiseTech’s advantage isn’t only what it builds. It’s how reliably it builds.

Over years, the company developed product and engineering processes that let it ship thousands of enhancements annually without sacrificing stability in a mission-critical environment. That ability—continuous improvement at high volume, with high reliability—is its own moat. New entrants don’t just need a good product idea; they need the operational machinery to deliver and maintain it, year after year, across a global customer base.

XIII. Key Performance Indicators to Watch

If you’re trying to follow WiseTech from here, there are three metrics that tell you, quickly, whether the story is still compounding—or starting to wobble:

1. CargoWise Revenue Growth and Large Global Freight Forwarder (LGFF) Rollouts

CargoWise is still the engine. In FY2024 (year ended 30 June 2024), WiseTech reported total revenue of A$1.04 billion, up 28%, driven by a 33% increase in CargoWise revenue to about A$880 million.

But revenue alone doesn’t tell you where that growth is coming from. The more revealing signal is Large Global Freight Forwarder rollouts—deployments inside the biggest, most complex customers in the industry. WiseTech reported total LGFF rollouts of 52, covering over half of the top 25 global freight forwarders.

The pace of new rollouts, alongside organic CargoWise revenue growth, is a practical proxy for whether the core platform is still winning the accounts that matter most—and expanding inside them.

2. Customer Retention Rate

CargoWise’s moat shows up most clearly in retention. WiseTech has reported annual gross retention above 99% per year since 2013—even while implementing significant price increases.

That’s the metric that underwrites everything else: the recurring revenue base, the ability to upsell additional modules, and the confidence to keep investing heavily in the product. If retention slips meaningfully below that 99%+ level, it’s a warning sign that something fundamental—product quality, customer satisfaction, competitive pressure, or implementation pain—may be changing.

3. EBITDA Margin and R&D Investment Rate

For years, WiseTech’s EBITDA margins above 50% were proof of the model’s operating leverage. With the e2open acquisition, margins were expected to compress into the 40–41% range in FY26. What matters now isn’t the dip—it’s the path back. Watching whether margins recover over time is one of the clearest readouts on integration execution and whether the combined business can return to WiseTech’s historical efficiency.

At the same time, keep an eye on the R&D investment rate—around one-third of revenue. That spending is not a nice-to-have; it’s how WiseTech maintains regulatory coverage, ships continuous enhancements, and keeps the platform ahead. If integration or debt costs force sustained cuts to product investment, that would be a real departure from the strategy that built the moat in the first place.

XIV. Investment Considerations

Material Legal and Regulatory Concerns

By late 2025, WiseTech wasn’t just dealing with headlines and board drama. It was dealing with regulators.

In October 2025, ASIC and federal police raided WiseTech’s Sydney office over alleged share trading violations. Earlier in late 2025, the AFP also raided WiseTech headquarters in connection with an insider trading investigation involving White and other employees. The market didn’t wait for outcomes: the stock dropped more than 15%.

All of this landed on top of a governance structure that had already been tested. White had stepped down as CEO in October 2024 amid conduct and transaction concerns, then returned as Executive Chairman in February 2025 after four directors resigned over his role. And through it all, White’s roughly 37% stake meant he remained the central figure.

The result is a real, ongoing overhang. Even if the underlying business keeps performing, regulatory scrutiny creates uncertainty, volatility, and reputational risk that can be hard to quantify—until it suddenly isn’t.

Founder Dependency

WiseTech’s rise has been inseparable from Richard White’s vision and leadership. The post-crisis structure—White as Executive Chair, Zubin Appoo as CEO—was designed to preserve White’s product and innovation impact while putting day-to-day execution and accountability in different hands.

But this is still a live experiment. The question isn’t whether WiseTech has talented operators. It’s whether the company can truly institutionalize what was, for decades, a founder-led system—without creating confusion about who ultimately decides.

Integration Risk

e2open is not a tuck-in. It’s a transformation.

That scale brings obvious challenges: systems, product roadmaps, go-to-market motions, and culture. And there are reasons to be cautious. e2open’s recent history included flat revenue growth and leadership instability, with its CEO dismissed in 2023—signals that integration may not be as clean as WiseTech’s prior, smaller deals.

If integration takes longer, costs more, or creates customer disruption—and if e2open’s retention is materially lower than CargoWise’s unusually strong retention levels—the deal could end up diluting returns instead of compounding them.

The Bull Case

The bull case starts with a simple observation: the governance crisis didn’t obviously break the product.

WiseTech still has the attributes that made it such a rare enterprise software business in the first place: mission-critical workflows, recurring revenue, and retention above 99%. Those fundamentals have remained surprisingly resilient through a period that would have destabilized many companies.

There’s also plenty of runway. Morgan Stanley has estimated the addressable market for global logistics software could reach around $40 billion by 2030. Against that, WiseTech’s FY2026 revenue guidance of $1.4 billion suggests it can keep growing for a long time if it continues to expand coverage, win rollouts, and deepen its platform.

If WiseTech executes the e2open integration, keeps its product development cadence, and navigates the governance and regulatory issues without a major operational hit, it has a plausible path to becoming even closer to what it claims to be: the operating system for global trade.

The Bear Case

The bear case is that the risks aren’t theoretical—they’re structural.

Control is concentrated in a founder who remains under heavy scrutiny, creating governance risk that some institutional investors simply won’t underwrite. The e2open deal adds meaningful execution risk and pushes margins down in the near term. And when a stock carries a premium valuation, the company doesn’t need to collapse to disappoint—anything less than excellent execution can be enough.

XV. Conclusion

WiseTech Global is a bundle of contradictions. It’s Australia’s most successful listed technology company and, at the same time, a governance warning label. It’s a patient, moat-building machine—and also a company in the middle of the biggest strategic swing of its life. It’s a proven compounder with unusually attractive economics, yet its stock has been whipped around by forces that have nothing to do with freight volumes or software quality.

More than anything, the WiseTech story is what happens when extreme long-term thinking collides with the realities of public markets—and with human fallibility. Richard White spent three decades building something rare: a mission-critical platform that WiseTech says touches more than half of global manufactured trade flows, with retention rates that most enterprise software companies would kill for. The bootstrap mentality, the product obsession, the decision to go deep in an unsexy industry—those weren’t quirks. They were strategic choices that compounded into real, durable advantage.

But founder-led companies come with founder risk. The same ownership structure that let WiseTech ignore short-term pressure also concentrated power in ways that exposed the business to governance shocks. And the same founder who drove the product vision became, in 2024 and 2025, a source of reputational and institutional instability.

For investors, WiseTech has become a live test of whether you can cleanly separate business fundamentals from governance concerns. Many analysts maintaining buy ratings are effectively betting that you can: that CargoWise’s moat—built over decades of workflow integration, compliance depth, and customer dependency—hasn’t been meaningfully damaged by the controversy.

Whether that’s clear-eyed or complacent will be answered over the next few years. What does seem clear is this: global trade doesn’t get simpler, and the infrastructure that moves goods across borders isn’t going away. CargoWise is already embedded in how a huge portion of the world ships. The question now is whether WiseTech can steady itself—governance, leadership, integration, and all—while still compounding on the foundation it spent 30 years laying.

And there’s a final irony worth sitting with. The freight forwarding world Richard White stumbled into in 1994—the one defined by customs codes, manifests, exceptions, and paperwork—was so unglamorous that almost nobody in tech bothered to chase it. That turned out to be the point. Sometimes the biggest empires get built in the corners everyone else ignores.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music