Vinamilk: The "White Gold" of Vietnam

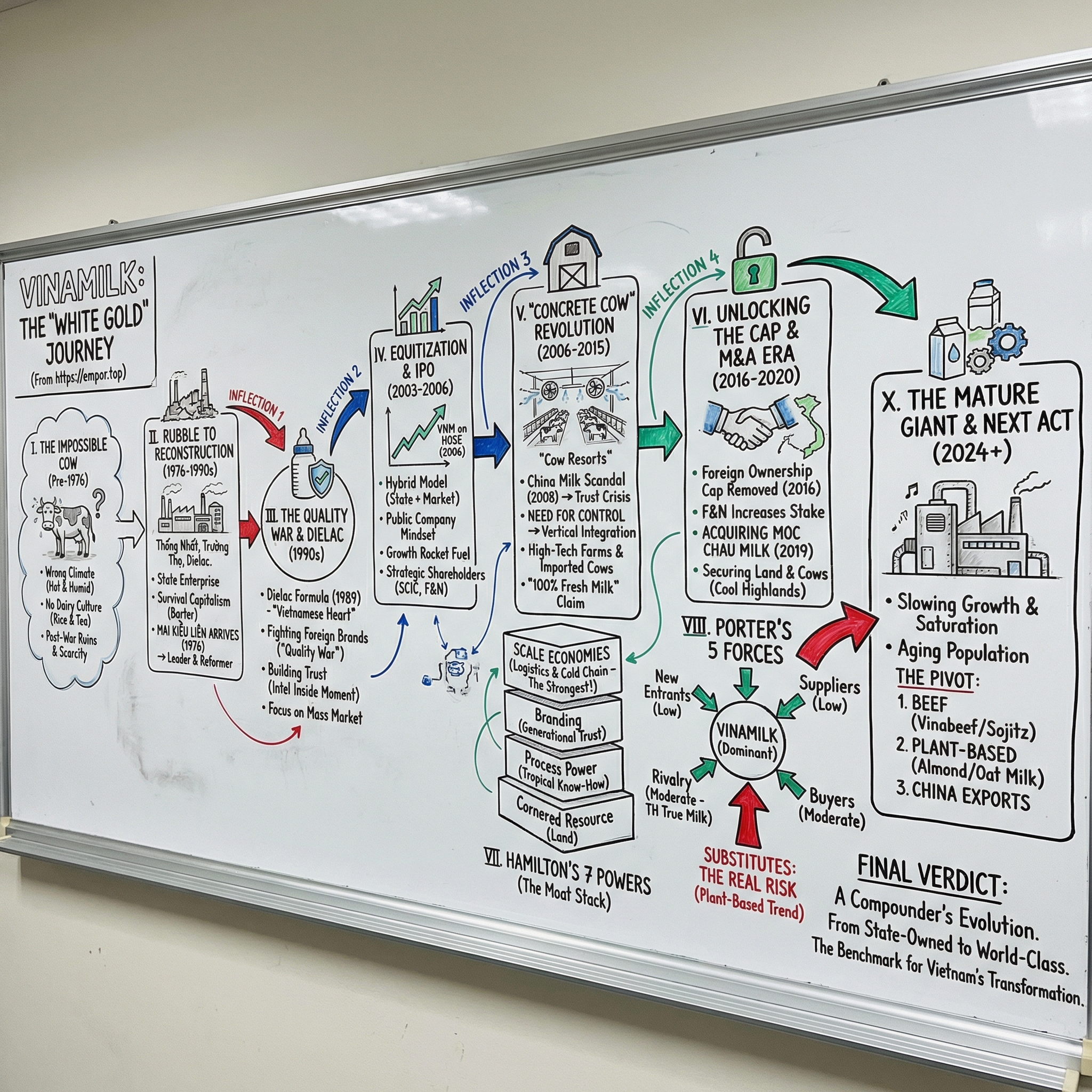

I. Introduction: The Impossible Cow

Vietnam is not supposed to be a dairy country.

It’s hot enough to make the air feel heavy. Humidity hangs like a wet blanket. And for most of Vietnamese history, the idea of drinking cow’s milk was about as culturally native as eating a grilled cheese. Yet today, a multi-billion-dollar dairy empire sits right in the middle of it all—selling milk to a nation that, not long ago, barely consumed it at all.

That company is Vinamilk. By any conventional rulebook of agriculture, it shouldn’t exist. And yet it does. It grew into a category-defining giant, commanding nearly half of Vietnam’s dairy market and becoming one of the most valuable consumer brands in Southeast Asia.

Now zoom back to 1976. Vietnam had just emerged from decades of devastating conflict. The economy was in ruins. Infrastructure was battered. Money was scarce. And dairy wasn’t just unpopular—it was largely absent. There was no deep tradition of producing or consuming dairy products. For centuries, cattle in Vietnam were mainly for draught power, manure, and meat. The first dairy cows arrived with colonial influence in the late eighteenth century, and even then, it was scattered and small—imports from various sources, never enough to build a national habit.

Then there’s the biology. The world’s most productive dairy cow—Holsteins—does best in cool weather, around 50°F. Vietnam’s climate is basically the opposite. Tropical heat and high humidity are, in cow terms, a hostile environment. And still, Vinamilk found a way to turn “cow hell” into an industry.

That’s why you’ll hear people describe Vinamilk as the “Coca-Cola of Vietnam”—not because it’s flashy, but because it’s everywhere. In many rural households, the brand name has become almost synonymous with milk itself.

The numbers underline the point. Vinamilk sits at number one domestically and has also made itself visible internationally, ranking 36th among the world’s top dairy companies by revenue. Its brand has been valued at USD 3 billion, and its products are sold across 65 countries and territories.

But the real superpower is distribution. Vinamilk operates 12 production factories. Its products reach roughly 224,000 retail points nationwide, show up in essentially every supermarket and convenience store in the country, and stretch into the hinterland with a reach that can feel deeper than many government services.

Recognition followed. In 2010, Vinamilk became the first Vietnamese company included in Forbes Asia’s 200 Best Under A Billion list. And by 2017, it was the first Vietnamese fast-moving consumer goods company to land on Forbes’ Global 2000.

Still, the most interesting part of Vinamilk isn’t its scale—it’s its transformation.

This started as a creaking state-owned enterprise built to satisfy production quotas, not investors. Over time, it turned into a ruthlessly efficient modern corporation, constantly balancing two forces that don’t naturally coexist: “food security,” the mandate to help nourish a recovering nation, and “shareholder value,” the pressure to deliver returns—even to foreign giants like Fraser & Neave.

That shift didn’t happen by accident. It happened because of one person: Mai Kiều Liên. She joined the same year the company was born, first as a factory engineer, and went on to lead it for decades as CEO.

But before we meet her, we have to go back to the beginning—to the rubble Vinamilk was built from.

II. History: From Rubble to Reconstruction (1976 – 1990s)

On August 20, 1976—just over a year after the fall of Saigon—the newly unified Vietnamese government had a blunt, urgent problem: how do you feed a country coming out of war?

One part of the answer was to take control of what industry still existed in the South. That same year, the state created what was first called the Southern Coffee-Dairy Company, built from three inherited dairy factories: Thống Nhất (owned by a Chinese company), Trường Thọ (previously tied to Friesland Foods and known for condensed milk distributed across the South), and Dielac (formerly Nestlé).

“Inherited” is a generous word. These weren’t modern plants ready to scale. They were old facilities with outdated equipment—described at the time as “good for nothing”—that needed to be repaired, rebuilt, and reassembled just to run. Vietnam also didn’t have a real dairy sector behind them: no dependable supply chain, no domestic herd to speak of, and no easy way to import inputs. So from day one, the company had to do what would become a Vinamilk habit: build capabilities in-house because there was no one else to rely on.

There were no consultants and no capital. What they did have was a mission that was more social than commercial: get nutrition into Vietnamese households, especially for children.

And the early years were defined by scarcity. Powdered milk was the base ingredient for most dairy products, but Vietnam didn’t have the foreign currency to import it at scale. So the company improvised—using barter arrangements with socialist allies, trading Vietnamese agricultural products for dairy ingredients. It was survival capitalism before Vietnam even had a vocabulary for capitalism.

Into that mess walked the person who would eventually define the company.

In 1976, Mai Kiều Liên returned to Vietnam after studying in the Soviet Union. She was born on September 1, 1953, in Paris, and her family—Vietnamese patriotic intellectuals living in France—moved back to Vietnam in 1957 to contribute to the homeland. Her hometown was in Hậu Giang Province, but her education took her far: she graduated from university in Moscow in 1976 with a degree in meat and milk processing.

She joined Vinamilk the same year, starting on the factory floor at Trường Thọ, responsible for condensed milk and yogurt. From there, she moved up in a way that felt both methodical and unstoppable: promotions in 1980 and 1982, then assistant to the director of Thống Nhất. In September 1983, she left again for a one-year management program in Leningrad, returned in June 1984, became vice director in July, and by 1992 she was director—a role she continued to hold.

Her reputation came with that trajectory. Over a 46-year career at Vinamilk, including three decades as CEO, she became known as a reform-minded leader with an appetite for change and the stamina to outlast it.

She also had a second kind of leverage: politics. From 1996 to 2001, she served on the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Vietnam. It wasn’t symbolic. It meant she had access to power at exactly the moment Vietnam was pushing through Doi Moi—its economic renovation policies—and deciding what “modern business” would look like inside a still-socialist system.

But even with factories running and leadership in place, there was a deeper obstacle than machinery or supply chains: culture.

Vietnamese consumers had not grown up with milk as an everyday food. Traditionally, milk was for babies and the sick. Changing that habit meant persuading families raised on rice water and tea that cow’s milk belonged on the table—and that it was worth paying for. Government policy began promoting milk consumption across all ages, but Vinamilk still had to make the idea real, product by product.

In its earliest phase, the company focused on essentials that matched the country’s needs and constraints. Condensed milk became a staple because it lasted, traveled, and fit a market without reliable refrigeration. And it developed Dielac as a domestic infant formula tailored to local nutritional requirements—an attempt not just to sell milk, but to fight malnutrition in a battered economy.

Even Vinamilk’s identity kept shifting as the state tried to define what it actually was. In 1978, it was renamed the United Enterprises of Milk Coffee Cookies and Candies, reflecting a broader food-production mandate beyond dairy. By 1993, it was restructured and formally established as the Vietnam Dairy Company—a signal that the enterprise was maturing, and dairy was no longer just one category among many. It was the category.

By the early 1990s, Vietnam itself was changing fast. Doi Moi reforms were opening the economy to private enterprise and foreign investment. And with that opening came a decision that would shape Vinamilk’s future: should it partner up with a foreign player—or protect its independence and build a Vietnamese champion?

In the late 1990s, many state-owned enterprises rushed into joint ventures. Vinamilk faced the same pressure. But inside the company, the debate dragged on for days. As Mai Kiều Liên later framed it, if a foreign partner held 70% of the shares and Vinamilk held 30%, the company would no longer have a real say in operations. In that scenario, could a Vietnamese milk brand truly survive?

They chose control over convenience. They chose the brand over the deal.

It was a pivotal call. But now came the hard part: proving that a Vietnamese-made product could compete on quality—against the foreign labels Vietnamese consumers already trusted more.

III. Inflection Point 1: The "Dielac" Gamble & The Quality War (1990s)

In Vietnam in the early 1990s, one belief shaped shopping baskets more than nutrition labels ever could: foreign equals quality.

As the middle class emerged, parents who wanted every advantage for their kids stretched their household budgets for imported milk powder from the Netherlands, the United States, or Australia. Dutch Lady, Abbott, Mead Johnson—these names weren’t just brands. They were reassurance, and they commanded premium prices and fierce loyalty.

For Vinamilk, that created an existential fork in the road. Would it stay a company that simply repackaged imported ingredients? Or could it make a formula that was truly Vietnamese—one parents would trust with the most sensitive decision they make: what to feed their children?

That bet became Dielac.

Vinamilk launched Dielac in 1989, positioning it as the first infant formula brand produced by a Vietnamese enterprise. That same year, Vinamilk restored Vietnam’s first infant formula factory using domestic technical expertise—an early signal that the company wasn’t satisfied being a distributor of someone else’s “quality.” It wanted to manufacture trust.

Dielac wasn’t just a label slapped onto powder. Vinamilk worked to formulate products tailored to Vietnamese children’s nutritional needs, and it cooperated with international organizations specializing in micronutrients and microbiology. The guiding idea was simple and emotionally potent: infant formula should be as close to breast milk as possible. In a country still fighting malnutrition, that wasn’t marketing. It was a mission.

But the market didn’t reward the mission at first.

Vietnamese parents were used to imported cans. A local formula—no matter how carefully made—still carried the stigma of being second-rate. Vinamilk had to fight a “quality war” on two fronts at once: limited equipment and limited belief.

This was Vinamilk’s “Intel Inside” moment: the decision to win with substance, not slogans. Over time, Dielac proved itself, can by can, child by child. A few years in, the skepticism started to crack. Eventually, Dielac grew to account for 30% of the domestic market.

The strategy underneath was as tough-minded as it was straightforward: Vinamilk would go where the multinationals weren’t looking. While global giants focused on premium urban customers, Vinamilk built for the low-to-mid income majority—and used its farms, factories, and nationwide supply chain to keep pricing within reach.

That’s how Dielac became more than a product line. It became a family habit.

The generational loop is the real moat. Babies fed Dielac in 1989 grew up and, years later, bought the same brand for their own children. That kind of trust doesn’t show up on a balance sheet, but it’s incredibly hard to dislodge.

Mai Kiều Liên later explained that the brand’s pull wasn’t manufactured—it was nurtured by the people behind it. In her framing, Dielac rested on three forces: a mother’s love, a Vietnamese heart committed to reducing malnutrition and improving children’s development, and an entrepreneur’s ambition to build a dairy industry on par with developed countries.

By the time the new millennium arrived, Dielac had become a cash engine and a national staple. And the momentum it created set up Vinamilk’s next leap—out of the old state-owned model and into the spotlight as a publicly traded powerhouse.

IV. Inflection Point 2: Equitization & The IPO (2003 – 2006)

“Equitization” is one of those words that sounds like it was invented by a committee. In Vietnam, it basically was—and it mattered. It was the country’s own mechanism for turning a state-owned enterprise into a joint-stock company: not full privatization, not pure state control, but a new hybrid built for a market economy.

For Vinamilk, that shift became official on October 1, 2003, when the company was capitalized and renamed Vietnam Dairy Joint Stock Company. Around this period, it also adopted the legal name Vietnam Dairy Products Joint Stock Company, while keeping the trading name the whole country already knew: Vinamilk.

Then came the moment that made it more than a food company. On January 19, 2006, Vinamilk listed on the Ho Chi Minh City Stock Exchange, under the ticker VNM.

This wasn’t just another listing. It was one of the events that helped define what “the Vietnamese stock market” would look like in the modern era. From there, Vinamilk became the reference point: a perennial top-tier listed enterprise, a VN30 heavyweight, and the kind of stock that could move the mood of the market.

In other words: the anchor tenant.

And once Vinamilk stepped into public markets, the company’s entire operating mindset had to evolve. This was no longer just about fulfilling state production targets. Now it was about performance, disclosure, and the relentless cadence of quarterly expectations. The same organization that had been built to run factories under scarcity conditions now had to run a public-company playbook.

The result was a different Vinamilk—bigger, sharper, and suddenly legible to global capital. Over time, it grew into one of Vietnam’s most valuable listed brands, with a market capitalization measured in the billions of dollars.

The IPO also set up a governance puzzle that would shape the next decade. Ownership ended up split among major stakeholders, including foreign investors and the State Capital Investment Corporation (SCIC), the government’s sovereign investment arm. Another key shareholder was F&N Dairy Investment, controlled by Thai billionaire Charoen Sirivadhanabhakdi. It was a structure that captured Vietnam’s broader balancing act: welcoming outside money while still keeping strategic assets close.

For Vinamilk’s business, the post-IPO years were rocket fuel. From 2008 to 2015, revenues grew at a rapid pace, with double-digit average growth and some years approaching 40%. By 2015, Kantar World Panel data showed just how deeply the brand had embedded itself: Vinamilk was the number one dairy brand in the country, reaching 97% penetration in urban areas.

The stock followed the story. Vinamilk’s share value grew dramatically compared to its early trading days—one of those rare emerging-market compounds that can turn early conviction into life-changing returns.

And the face of that transformation was still Mai Kiều Liên. Forbes credited her as a dynamic leader who helped turn Vinamilk into one of Vietnam’s most profitable brands and a respected name across Asia.

But even as the market celebrated—and the stock chart climbed—a different kind of crisis was forming just outside Vietnam’s borders. It would force Vinamilk to rethink the most basic question in dairy: where does the milk actually come from?

V. Inflection Point 3: The "Concrete Cow" Revolution (2006 – 2015)

In September 2008, while the global financial crisis dominated the front pages, a different kind of crisis ripped through Asia’s food system.

China’s milk scandal wasn’t a minor quality lapse. It was a gut-punch to trust. Melamine had been deliberately added at milk-collecting stations to watered-down raw milk, essentially to fake higher protein readings. The World Health Organization called it “deplorable.” At least 11 countries halted imports of Chinese dairy products. Trials followed, with severe sentences—including two executions, multiple life sentences, and long prison terms.

The human cost was even worse. Roughly 300,000 infants and young children suffered kidney and urinary tract damage, including kidney stones, and six deaths were reported.

Vietnam reacted fast. On September 25, 2008, it banned milk imported from China. The Ministry of Health found melamine in 18 products and ordered importers to recall and destroy them.

And suddenly, the dairy business changed overnight. In a category that lives or dies on safety, confidence became the real currency. Some players stumbled—Hanoi Milk, for example, recalled several products after tests found melamine in input materials and products. But analysts noted that Vinamilk didn’t take the same hit in consumer confidence.

In fact, Vinamilk came out of the episode with its reputation strengthened. More importantly, the scandal forced a strategic realization into sharp focus: depending on imported milk powder was a risk, not a shortcut. If Vinamilk wanted to control quality end-to-end—and credibly charge for “100% Fresh Milk”—it needed to control the source.

It needed to own the cows.

That sounded almost absurd in Vietnam. The country’s heat and humidity are brutal on Holstein cows, which are built for temperate climates. The conventional wisdom was simple: large-scale dairying in the tropics is a losing game.

Vinamilk decided to play anyway.

The early moves were already underway. In 2006—the same year it listed on HOSE—Vinamilk inaugurated its first dairy farm in Tuyên Quang. That was the opening shot of what would become one of the most ambitious agricultural modernization projects in Southeast Asia.

From there, Vinamilk began building a herd it could control. It imported higher-yielding dairy cattle, including Holsteins from countries like Australia, New Zealand, and later the United States, while many small farmers across Vietnam continued raising crossbreeds such as Sindhi (Zebu) x Friesian cows. Over time, Vinamilk’s own farming footprint expanded, including major sites in places like Lâm Đồng in the Central Highlands and Quảng Ngãi in central Vietnam.

These weren’t traditional farms. They were engineered environments—what observers started calling “resorts for cows.”

At Vinamilk’s high-tech farms, the pitch was comfort by design: controlled barn temperatures, mist-spraying systems to cool animals in the tropical heat, automated cooling fans, and closed waste treatment systems supported by biogas and renewable energy like solar. The stables used free-stall designs suited to each stage of a cow’s development, with soft imported mattresses, automatic water troughs, and robotic massage brushes designed to improve comfort and stimulate metabolism.

Behind the scenes, the farms ran on data. Cow health and productivity were tracked through electronic chips. Feeding systems were calibrated by age and development stage. Information could be monitored and updated in real time using cloud storage, turning what used to be “animal husbandry” into something closer to operations engineering.

This was the “concrete cow” revolution: industrial-scale, tech-enabled dairying, built for a climate that didn’t want it.

Vinamilk kept expanding the system—growing to a network of farms applying what it described as “4.0” technologies and pursuing international standards such as Global G.A.P. and European Organic. Alongside company-owned farms, it also collected fresh milk through a large network of associated farmer households. At this scale, Vinamilk was exploiting the largest dairy herd in the country, with about 130,000 cows at the time referenced.

And this is why it mattered.

Vertical integration didn’t just improve quality. It changed the competitive landscape. It squeezed out companies that were still largely assembling dairy products from imported powder and water. It gave Vinamilk something rare in consumer packaged goods: a premium claim—“100% Fresh Milk”—with real infrastructure behind it.

It also built a wall around the business. To compete head-on, a challenger would need to do all of the hard things at once: secure land, build high-tech farms, import premium cattle, develop tropical-dairy expertise, and then build a cold chain capable of moving fresh milk fast in a hot country. The cost would be massive, and the learning curve brutal.

Vinamilk’s farm investments reflected that ambition. One farm cited as costing VND 700 billion was designed to house about 4,000 milking cows, as part of the Vinamilk Thanh Hóa dairy farm complex—planned as four high-tech farms with a combined milk supply target of 110 million litres per year by 2020.

By 2015, Vinamilk was no longer just a dairy processor. It had turned itself into something far more defensible: a vertically integrated dairy machine, controlling the chain from cow to consumer.

VI. Inflection Point 4: Unlocking the Cap & The M&A Era (2016 – 2020)

For years, Vinamilk had a strange problem for a public company: investors wanted in, but the door was half-locked.

Vietnam’s “foreign ownership limit” capped foreign shareholding in most listed companies at 49%. Vinamilk had been pressed up against that ceiling for years. Overseas funds sat in a kind of permanent queue, waiting for someone—anyone—to sell.

That bottleneck annoyed everyone. Vinamilk’s stock couldn’t fully reflect demand, which helped keep the valuation artificially constrained. And for the Vietnamese government—still holding about 45% through the State Capital Investment Corporation (SCIC), and thinking about further privatization—it meant any eventual stake sale would bring in less money than it could have.

So in 2016, Vinamilk made a move that signaled just how far it had traveled from its state-enterprise origins. The company decided to remove the cap. On July 20, 2016, the State Securities Commission approved raising foreign ownership in Vinamilk to as much as 100%, up from 49%—reportedly the first major state-linked enterprise in Vietnam to fully lift the restriction.

VinaCapital’s CIO Andy Ho called it “a huge milestone” in privatization: Vinamilk was the country’s largest company by market capitalization, one of Vietnam’s most valuable brands, and a consistent performer. Opening it up completely wasn’t just a corporate governance tweak. It was a statement that Vietnam’s capital markets were growing up.

And of course, once the gate opened, a familiar name pushed forward.

Among the most aggressive buyers was Fraser & Neave (F&N), the Singapore-based beverage and consumer group controlled by Thai billionaire Charoen Sirivadhanabhakdi. F&N Dairy Investment became Vinamilk’s largest foreign shareholder, holding around 11% at the time referenced, and it had already secured two representatives on Vinamilk’s board.

The obvious question followed: was Vietnam’s milk company about to become someone else’s?

Mai Kiều Liên didn’t hedge. Foreigners, she argued, were investing because Vinamilk was Vinamilk. “So I don't think there is anyone who will buy into Vinamilk to get rid of the brand, especially when it is the number one dairy brand of Vietnam.”

With the ownership ceiling out of the way, Vinamilk shifted from defense to offense. If growth was slowing at home, the next lever was consolidation—and in late 2019, Vinamilk went after the biggest prize in the north: GTNFoods, and through it, Moc Chau Milk.

In early 2019, Vinamilk offered to buy shares of GTNFoods. By December 2019, it completed the takeover, increasing its ownership in GTNFoods from 43.17% to 75%. GTNFoods owned 51% of Moc Chau Milk, the largest dairy producer in northern Vietnam—so control of GTN effectively meant control of Moc Chau.

On paper, Moc Chau was already meaningful. It held about 9% of Vietnam’s dairy market overall, and as much as 35% in the northern region. It had roughly 80,000 retail points. And it came with a serious production base: as of December 2018, Moc Chau reported 25,000 cows, all thoroughbred dairy cows.

Analysts framed the deal as a shortcut through a slowing market—one estimate suggested that capturing Moc Chau’s share organically could have taken Vinamilk close to a decade at its prevailing pace.

But the real prize wasn’t just share. It was something far harder to manufacture: land.

“Moc Chau Milk has ample land banks and an extensive farm system,” one assessment noted, and those assets could be upgraded under Vinamilk’s management system and ERP. Moc Chau sits in cool highland terrain—dairy-friendly real estate that becomes more valuable every year as Vietnam industrializes and competition for land intensifies.

This was the “Disney buying Fox” moment of Vietnamese dairy: the category leader buying its oldest, sleepier rival not only for customers, but for the irreplaceable terrain beneath the cows.

After the deal, Vinamilk’s investment in GTNFoods positioned it to participate in the management of Moc Chau Milk, including a herd cited at 27,500 cows.

VII. The Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

If you run Vinamilk through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework—the question of what advantages actually endure—you don’t just find one moat. You find a stack of them, built over decades, in a market where most companies never get the chance to build even one.

Scale Economies (The Strongest Power):

Vinamilk’s biggest advantage isn’t a secret ingredient. It’s logistics.

In dairy, the cold chain isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the business. In Vietnam’s heat, milk can go bad fast if you don’t move it, chill it, and keep it chilled. Vinamilk built that system early and then kept widening it: a nationwide distribution network with more than 50 centers, supplying supermarkets, small retailers, and foodservice with everything from fresh milk to yogurt, cheese, and powdered products.

Underneath that reach is an industrial machine. Vinamilk works with 266 exclusive distributors to serve roughly 224,000 retail points, coordinated through an Oracle-built enterprise resource planning system. That’s what scale looks like in real life: not just “available everywhere,” but replenished everywhere, on time, at temperature.

And the compounding effect is brutal for anyone trying to catch up. More volume makes more routes economical. More routes increase coverage. More coverage lifts volume again. You don’t break into that loop without years of execution—and an enormous amount of capital.

Branding:

Vinamilk also has something you can’t buy with capex: generational trust.

The children who grew up on Dielac in the late 1980s became parents, and many of them kept buying the same brand for their own kids. In rural Vietnam, “Vinamilk” has drifted toward becoming a generic word for milk—the way “Xerox” once stood in for photocopying.

And the brand hasn’t stayed frozen in nostalgia. IPSOS brand health measurements showed Vinamilk’s innovation index rising from 76% in 2023 to 82% in the first half of 2024. Its brand value climbed from $2.8 billion in 2022 to $3.3 billion in 2023. The point isn’t the exact figures—it’s that the trust is still alive, and it’s still being refreshed.

Process Power:

Then there’s the know-how: what you learn when you try to run a world-class dairy operation in a place that cows were never meant to thrive.

Vinamilk has spent years accumulating “tropical dairy” process power—how to keep Holstein yields high in hot, humid conditions; what feeding regimens hold up; which cooling systems deliver the best results for the money; how to manage disease pressure in a climate that’s working against you. It’s not theoretical. It’s operational memory, built farm by farm, year by year. Vinamilk has even worked to improve yields alongside Japanese dairy experts.

That kind of institutional knowledge doesn’t transfer quickly, and it’s very hard to copy from the outside.

Cornered Resource:

Finally, the resource that keeps getting scarcer: land.

As Vietnam industrializes, the amount of suitable space for large-scale dairy farming shrinks, especially the kind of cooler highland terrain where cows actually perform well. Vinamilk locked up key sites early—and the Moc Chau acquisition only strengthened that position. As one assessment put it, “Moc Chau Milk has ample land banks and an extensive farm system that will benefit from Vinamilk's management system.”

The Moc Chau highlands and the Dalat plateau offer the temperatures dairy cows need. And there simply isn’t much more of that land to go around.

VIII. Porter's 5 Forces: The Castle Under Siege?

Threat of New Entrants: Low

If you want to take Vinamilk head-on, you don’t just need a good product. You need farms, refrigeration, trucks, retail relationships, and enough scale to keep fresh milk cold all the way through a tropical country. Vinamilk spent decades building that machine. Replicating it would take hundreds of millions—possibly billions—of dollars, with no guarantee you ever reach escape velocity.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low

Vinamilk doesn’t negotiate from the position of a buyer. It is the buyer.

It supports farmers with financing, training, and inputs like fertilization and fodder to help them move from rice cropping into cattle farming. It signs supply contracts, but typically keeps flexibility on how much it will purchase. That structure gives Vinamilk the upside: a flexible milk supply without loading its balance sheet with excessive farm assets.

For small farmers, that dynamic is hard to resist—selling to Vinamilk is often the only truly viable route. And on imported milk powder, the story is similar: Vinamilk’s scale gives it meaningful leverage with suppliers.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Moderate

On paper, consumers can switch brands. In reality, dairy—especially infant formula and children’s nutrition—doesn’t behave like a normal packaged-goods aisle. Once parents believe a product works for their child, they don’t like to experiment. That loyalty blunts buyer power, even when alternatives are everywhere.

Threat of Substitutes: The Real Risk

This is the pressure point.

Vinamilk spent decades convincing Vietnamese consumers that milk should be part of everyday life, even in a region where lactose intolerance is common. Now, as people pay more attention to how their bodies feel—and as plant-based becomes a global default trend—the substitution threat is getting louder.

Vinamilk is not ignoring it. In March 2024, it launched a new line of almond and oat milk products, marking its third expansion in plant-based in two years. The company invested VND 500 billion in R&D to improve taste and nutritional value, and the products were reportedly well received in urban markets, with sales projected to grow by 15% by the end of 2024.

And it’s not a one-company race. The Vietnam milk alternatives market includes players like Vinamilk, Nutifood, TH True Milk, Alpro, and Oatly, competing through distribution strength and brand positioning—the same weapons that defined the dairy wars.

Rivalry: Moderate

Vietnamese dairy is competitive, but it isn’t fragmented chaos. It’s more like a league with a dominant incumbent and a few serious challengers.

In 2021, Vinamilk held 43.7% of the market, followed by TH Food at 14.1% and Friesland at 9.4%. The most visible challenger is TH True Milk—the “noisy neighbor” that picked a very specific fight: “clean milk.”

TH Milk JSC, based in Nghệ An, made its move with a large-scale project and launched TH True Milk on 26.12.2010, stepping directly into competition with established players. Founded in 2009, TH True Milk quickly built a reputation around advanced technology, sustainable practices, and high-quality, organic positioning.

But Vinamilk is still the Goliath. It remains the giant across nearly every segment—and as of the end of 2024, it still held close to half the market, according to Data Factory VIRAC. In Vietnam, you can challenge Vinamilk on a message. You can even win pockets of the market. But displacing it everywhere at once is a very different kind of battle.

IX. The Playbook & Lessons

The "Developing Market" Paradox

In rich countries, a consumer-goods company can take the basics for granted: roads that work, electricity that stays on, refrigerators in every home, and a cold chain that already exists.

Vietnam in the 1970s and 1980s wasn’t that. For Vinamilk, you couldn’t just make milk and hope the market would do the rest. You had to help build the conditions for the product to even be usable. That’s the developing-market paradox: product development and infrastructure development are inseparable.

State-Owned to State-of-the-Art

Mai Kiều Liên didn’t just run a dairy company. She ran a dairy company while Vietnam itself was changing underneath her—moving from a quota-driven state economy toward something that increasingly looked like a market.

That meant learning how to manage government stakeholders while still operating with the discipline of a modern corporation. It required political instincts and commercial rigor at the same time. Liên had to navigate downturns, shifting policies, and intensifying competition—and keep the machine moving anyway.

The "Iron Lady" Leadership

Liên brought something that’s rare anywhere, and especially rare in an emerging market: continuity.

She has held the top job for decades, leading Vinamilk through multiple eras and multiple definitions of what the company was supposed to be. That kind of stability compounds. It enables long-term investment, durable relationships, and the slow accumulation of institutional knowledge—advantages that don’t show up in a single quarter, but can define an entire generation.

Vertical Integration as Survival

In developed markets, the standard advice is to outsource anything that isn’t core.

Vinamilk learned the opposite lesson. In an emerging market, where external systems can be inconsistent, owning the stack becomes a form of quality control. If you want safety, reliability, and the right to charge a premium, you can’t just buy it from the outside. You have to build it—cows, trucks, factories, and the cold chain that keeps the whole promise from collapsing in Vietnam’s heat.

For investors, two indicators cut through the noise when tracking how the story evolves from here: 1. Domestic market share — the clearest read on whether Vinamilk is holding off challengers like TH True Milk and others 2. Gross margin — the quick test of input-cost pressure (especially imported milk powder) versus Vinamilk’s ability to keep pricing power

X. Conclusion: The Mature Giant

At some point, every great compounding story runs into gravity. For Vinamilk, the 2024 results look less like a rocket ship and more like a very large, very efficient machine doing what mature machines do: grinding forward.

In its 2024 annual report, Vinamilk posted consolidated revenue of 61,824 billion VND, up 2.2% year over year, and profit after tax of 9,453 billion VND, up 4.8%. Another report framed the same year as its highest profit in three years, with net profit around VND 9.45 trillion, up 6.5%.

The broader context matters more than the exact figures. Revenue growth has been flattening for a while. Between 2017 and 2024, Vietnam’s milk market moved steadily toward saturation, with growth slowing to about 5.4% per year. Population growth sat around 0.7% annually as the birth rate kept declining, and per-capita spending on milk began to hit a ceiling. Over that same stretch, Vinamilk’s domestic revenue growth trailed the market at roughly 2.2% per year—evidence that competition intensified and the easy wins were gone.

And then there’s the most structural headwind of all: Vietnam is aging faster than expected. That’s a problem for a company that built its franchise on children’s nutrition and household staples.

The Pivot

Vinamilk isn’t pretending this is still the 2000s. It’s pushing for a second act, with three big moves: beef, plant-based, and exports—especially China.

First: beef. Vinamilk has moved into the category through Vinabeef, a joint venture with Japan’s Sojitz Corporation. The operating vehicle is Japan Vietnam Livestock Co., Ltd. (JVL), a joint venture established in September 2021 by Sojitz and Vietnam Livestock Corporation JSC (VILICO), which is affiliated with Vinamilk. JVL broke ground on what was described as one of Vietnam’s largest cattle farm and beef processing complexes in Vĩnh Phúc province, with operations scheduled to begin in June 2024.

The investment for the project was set at VND 3 trillion (about US$131 million), and it sits inside a broader Vietnam–Japan collaboration plan in high-tech agriculture, cattle breeding, and beef processing, with cooperative agreements signed at the end of 2021 totaling up to $500 million.

By December 17, 2024, Sojitz said it had begun operations at a major beef processing plant in Tam Dao, Vĩnh Phúc, via JVL. The plant is positioned as the first in Vietnam to process refrigerated beef, with processing in a controlled, highly sanitized environment. Longer term, Sojitz aims for the plant to process and ship about 10,000 tons of beef per year.

Second: plant-based. Vinamilk is expanding into alternatives because it has to. In March 2024, it launched a new line of almond and oat milk products—its third plant-based expansion in two years—and invested VND 500 billion in R&D with a focus on taste and nutritional value.

Third: China. Vinamilk has been pushing into the world’s largest dairy import market with organic fresh milk positioned to meet Chinese organic standards as well as EU Organic standards. It also introduced skimmed and pasteurized fresh milk at the Shanghai show—products that marked its first export of fresh milk, including organic milk, to China. Vinamilk has since received approval to access what it described as China’s US$60 billion milk market.

Final Verdict

So is Vinamilk a value trap—or a compounder getting ready for its next leg?

The “value” part is easy to see. It is still Vietnam’s cash cow, literally: a mature business that throws off substantial cash and keeps a strong balance sheet. Vinamilk reported total assets of VND 54.2 trillion against liabilities of VND 15.8 trillion, and it maintained high liquidity.

The harder question is growth. The beef venture with Sojitz is ambitious and strategically logical, but it’s still early. China offers a massive market, but it’s fiercely competitive and notoriously protective. Plant-based is a necessary hedge, but it’s also a sign that the center of gravity in consumer preferences is shifting.

What doesn’t change is the core achievement. Vinamilk’s journey—from rusting nationalized factories to one of Asia’s most valuable food brands—is one of the most remarkable corporate transformations in emerging-market history. Under Mai Kiều Liên’s leadership, it proved three things that weren’t supposed to be true: that a Vietnamese enterprise could out-execute global multinationals at home, that a tropical country could run world-class dairy operations, and that a communist-era state-owned enterprise could evolve into a modern public company with real governance and capital-market credibility.

The next chapter is still being written. But for anyone trying to understand Vietnam—economically, socially, and as an investable story—Vinamilk isn’t optional. It’s the benchmark. Its wins and stumbles track the country itself: from war-torn scarcity to middle-income ambition, from closed borders to global integration, from survival to whatever comes next.

Chat with

this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with

this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music