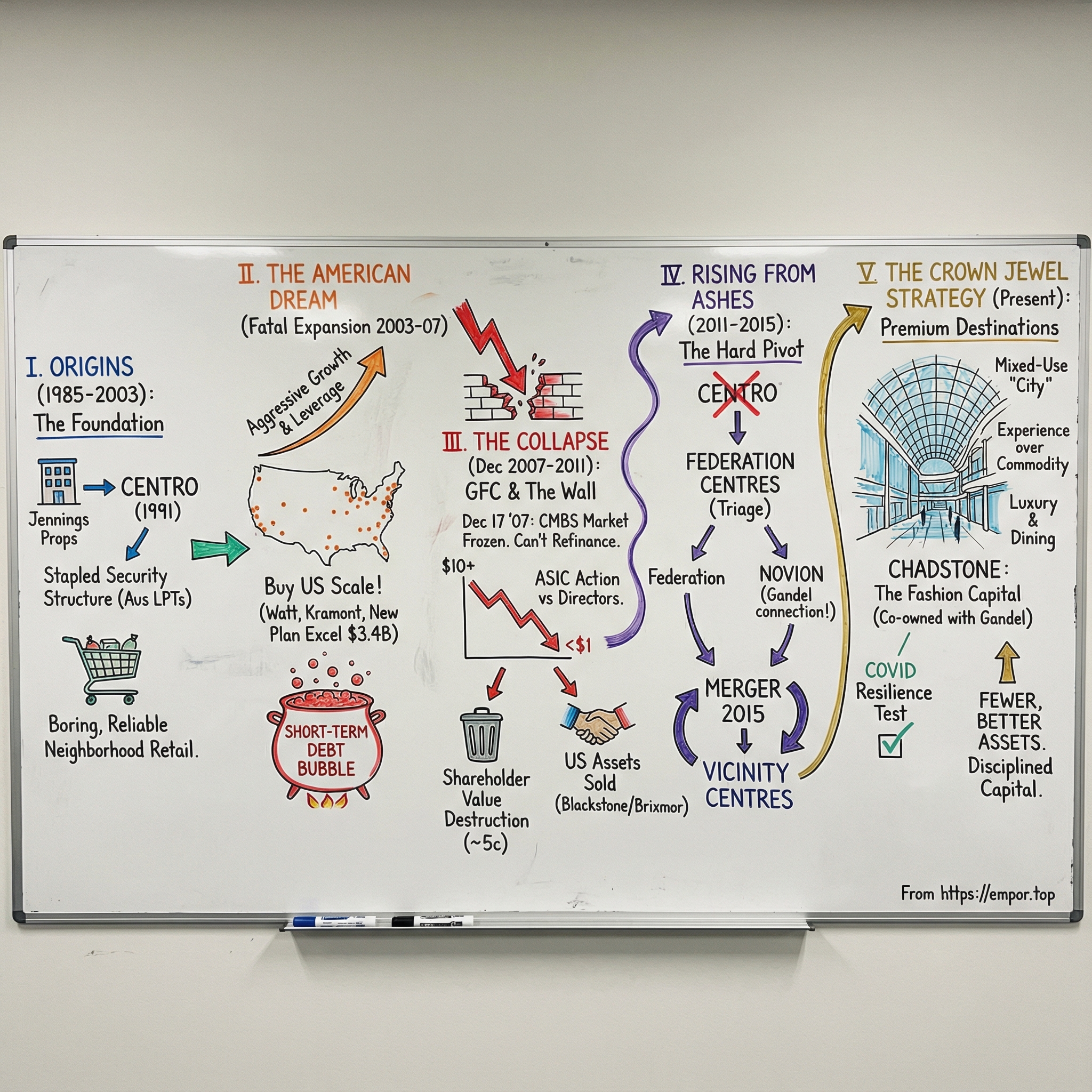

Vicinity Centres: Australia's Shopping Mall Empire—From Near-Death to Reinvention

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

December 17, 2007. In Centro Properties Group’s glossy headquarters, the mood flipped from confidence to crisis in a single announcement. Centro—one of Australia’s market darlings—admitted it couldn’t refinance short-term debt. And the market didn’t debate it. It voted.

In the space of days, the share price that had traded above ten dollars just months earlier collapsed toward a dollar. This was a company that controlled more than 800 shopping centres across Australia, the United States, and New Zealand—an empire once valued around ten billion dollars. Now it was staring down the very real possibility of failure.

“We never expected the sources of funding that historically have been available to us and many other companies would shut for business,” chairman Brian Healey said, pointing directly at the U.S. CMBS market.

That single line became the public start of one of the most dramatic corporate unravellings in modern Australian business. Because Centro didn’t just stumble. It revealed, in real time, what happens when a highly leveraged property machine runs out of oxygen.

And yet this isn’t only a disaster story. Centro would survive, restructure, change its name, merge, and eventually re-emerge as Vicinity Centres.

Today, Vicinity is one of Australia’s leading retail property groups. It manages about $24 billion in retail real estate across 52 shopping centres, making it the country’s second-largest listed manager of Australian retail property. It holds direct interests in 51 shopping centres (including the DFO Brisbane business) and manages a further 26 assets on behalf of strategic partners.

That’s the paradox at the heart of this episode: a business that nearly destroyed itself chasing scale in the United States, then fought through one of Australia’s most complex reorganisations, and came out the other side holding Chadstone—Australia’s most iconic, highest-profile shopping centre—as its crown jewel.

This is a story about the American dream turning into a balance-sheet nightmare. About financial engineering: how it can manufacture growth, and how it can quietly plant the explosives. And about physical retail—an industry declared dead more than once—that instead evolved into something closer to an entertainment district, a dining precinct, and a civic hub all rolled into one.

Along the way, you’ll meet visionary retailers who imported the suburban mall idea from postwar America, executives and directors who signed off on accounts that hid urgent debt, and the low-profile billionaire family that helped turn a shopping centre into Australia’s fashion capital.

So let’s go back to the beginning. Before the U.S. expansion. Before the crisis. Before the reinvention.

It starts in 1985, with a modest property offshoot of a construction company taking its first steps onto the Australian Securities Exchange.

II. Origins: Jennings Properties and the Birth of Centro (1985–2003)

To understand Vicinity Centres, you first have to understand the oddly Australian world of property trusts in the late twentieth century. The U.S. had REITs. Australia built its own version: listed property trusts, or LPTs. For local investors—especially superannuation funds—they were a perfect product: steady distributions, a whiff of inflation protection, and the comforting idea that your money was backed by real buildings on real land.

That’s the backdrop for what came next.

On 18 February 1985, diversified construction and property group Jennings Industries established Vicinity Limited as Jennings Properties and listed it on the Australian Securities Exchange. Jennings was a builder and developer; carving out a listed property vehicle was a clean way to recycle capital from completed projects while continuing to earn management income.

In January 1991, the business took a new name: Centro Properties. The rebrand wasn’t cosmetic. It signaled ambition. Centro focused on neighbourhood and convenience retail—the places where daily life happens. Groceries. Pharmacies. Quick errands. These weren’t glamorous trophy malls. They were practical assets with tenants who needed to be physically close to customers, in good times and bad. Boring, predictable… and, for a property trust, beautifully bankable.

Then, in 1997, Centro made the move that defined an era of Australian real estate finance. In September 1997, it was restructured into a stapled security structure called Centro Properties Group. A Centro stapled security comprised one unit in Centro Property Trust (CPT) stapled to one share in Centro Properties Limited (CPL). CPT owned Centro’s interests in the properties, and CPL, along with its subsidiaries, provided management services to CPT.

It sounds like legal fine print, but it mattered. The stapled structure was an elegant workaround: the trust held the real estate, while the company did the active work—leasing, development, acquisitions, and strategy—without upsetting the tax and regulatory logic that made trusts attractive in the first place. It also created a powerful growth engine. More properties didn’t just mean more rent; it meant more management activity and more fees.

And in the early 2000s, with cheap capital sloshing around global markets, that engine didn’t have to work very hard. Centro’s playbook was simple: buy more centres, run them efficiently, and pay out reliable income. By the early 2000s, it was seen as a solid operator with a growing Australian portfolio, supportive investors, and plenty of financing options.

Which is usually the exact moment a successful company starts looking over the horizon for something bigger.

For Centro, that horizon was America—home of the modern shopping centre, and soon, the setting for the bet that nearly wiped the whole thing out.

III. The American Dream: Centro's Fatal Expansion (2003–2007)

On paper, the U.S. made perfect sense.

America’s convenience retail landscape was wildly fragmented—thousands of strip centres owned by local developers, family trusts, and small-time operators. Compared with Australia’s already-hot property market, cap rates looked tempting. And back home, Australian property trusts were awash with investor capital, hungry for growth.

Centro’s leadership believed they had a repeatable playbook: buy under-managed centres, lift performance through better leasing and upgrades, and scale fast.

After entering the United States market in late 2003, Centro acquired, redeveloped, and renovated a number of mall properties. The push started with a joint venture. In late 2003, Centro Properties Group and U.S.-based Watt Commercial Realty formed Centro Watt and bought 14 California shopping centres for $488 million. In 2005, Centro went bigger again, acquiring Kramont Reality Trust for $1.2 billion.

Then came the deal that signaled Centro wasn’t dabbling anymore—it was trying to become a major American landlord. On 9 May 2006, Westfield announced it would sell seven U.S. shopping centres that no longer fit its strategy. Centro bought them. By then, Centro was the fifth-largest retail property owner and manager in the United States, with 682 properties.

That’s the dizzying part: an Australian business that had built its reputation on steady, unglamorous neighbourhood retail was now, in just a few years, one of the biggest strip-centre players in America.

But the true peak of Centro’s U.S. ambition was still ahead.

In 2007, Centro announced the acquisition of New Plan Excel Realty Trust, a massive U.S. retail property owner. Analysts later pointed to one specific fault line: Centro’s inability to refinance the bridging loan that funded the $3.4 billion New Plan Excel acquisition, struck at exactly the moment credit markets began to turn.

The structure mattered. The New Plan deal leaned on short-term bridging finance and joint venture arrangements, with the assumption that Centro could later refinance in the commercial mortgage-backed securities market—the same CMBS market that was about to seize up as the subprime crisis spread beyond housing.

Internally, the company was still writing the triumph narrative. Centro’s 2007 annual report, titled "Resilience for growth", declared that its business model provided “a reliant basis” to “operate, grow and drive investor returns”. And in August, it did manage to secure $300 million through CMBS financing.

But the questions were getting louder, because the debt load had become enormous: about $18 billion, nearly 70 percent of asset value. That’s not just aggressive. In property, it’s suffocating—especially when a meaningful chunk of that borrowing has to be constantly rolled over.

And the warning signs weren’t subtle. In September, the Australian Stock Exchange discovered Centro had understated by $1.1 billion in debt due within 12 months. Around the same time, eyebrows rose when management paid itself a 2007 bonus before the year was even over.

Zoom out and the backdrop was getting darker by the week. In September 2007, the U.S. Federal Reserve began cutting rates—an early acknowledgment that the credit system was under strain. What started as a subprime mortgage problem was metastasizing into a full-blown global crisis. The GFC would come to define the period of extreme stress in global financial markets from mid-2007 into early 2009.

Centro’s timing, in other words, was catastrophic. It had made its biggest-ever acquisition at the top of a credit bubble, funded with short-term debt, in a world that was rapidly losing its appetite for refinancing anything.

The American dream was about to become an Australian nightmare.

IV. The Collapse: When the Music Stopped (December 2007–2011)

December 17, 2007 started like a normal Monday on the ASX. By the end of it, Centro wasn’t just wobbling. It was in free fall.

That morning, Centro told the market two things that, in a credit panic, are basically the same thing: profits were going to be lower, and refinancing was going to be harder. The company admitted it had failed to renegotiate $1.3 billion of debt. It cut its dividend forecast. And then investors did what investors do when a highly leveraged property trust says “we can’t roll the debt.”

Centro’s shares collapsed 76 percent in a single day, down to $1.36.

The company’s language was careful, almost understated—corporate-speak trying to mask a run on confidence. “Tightened credit conditions have had the effect that negotiation of a comprehensive refinancing package of short term facilities has not yet been finalised,” Centro told the exchange.

But everyone understood what that meant. Centro had built its growth model on short-term borrowing and the assumption that refinancing would always be available. Now the refinancing window was closing. Fast. And Centro, with its huge U.S. exposure, became one of Australia’s most visible casualties of the subprime panic rippling through global markets.

The numbers behind the story were as big as the problem. Through its various funds, Centro had investments in hundreds of U.S. shopping centres, and it managed tens of billions of dollars of property overall. But what the market cared about wasn’t the scale. It was the fragility. Since May—when the stock had traded around $10—most of Centro’s equity value had already evaporated.

By midweek, the mood around Centro had turned from “this is ugly” to “this might not survive.” One analyst, Rich, put Centro’s chance of survival at 10 percent. The company’s market value had shrunk dramatically in days.

And hanging over everything was a simple, brutal calendar.

Centro and its affiliates faced a wall of debt maturities—billions coming due in a matter of months. It had already needed extensions from banks. Key agreements with U.S. bankers were due to expire on September 30, and with Australian bankers on December 15. Meanwhile, one of the largest owners of shopping centres in the United States—Australia-based Centro Properties Trust—was suddenly on the verge of collapse unless it could pay down or refinance $3.4 billion by February 15, 2008.

This is what leverage looks like when the music stops. The assets don’t disappear. The rents don’t instantly go to zero. The problem is that the refinancing machine—the thing that quietly kept the whole structure standing—does.

And by then, that machine was broken. In the months leading up to the collapse, the U.S. CMBS market—one of the key sources of commercial property funding—had cratered. The cost of capital rose. Liquidity vanished. Centro had effectively bet its future on a market that, almost overnight, stopped existing.

What followed wasn’t a clean bankruptcy and restart. It was years of grinding negotiations: restructurings, asset sales, and balance-sheet triage. The financial pain showed up quickly. Centro reported a multi-billion-dollar full-year loss, including more than a billion dollars in property revaluations, after having posted a substantial profit the year before. As the crisis deepened, the story shifted from “temporary funding issue” to “systemic collapse.”

Then came the legal reckoning.

In June 2011, the Federal Court of Australia found that eight Centro executives and directors breached the Corporations Act by signing off on financial reports that failed to disclose billions of dollars of short-term debt. The action was brought by ASIC, and it targeted senior leadership and board members including ex-CEO Andrew Scott, former chairman Brian Healey, then-chairman Paul Cooper, ex-CFO Romano Nenna, and several non-executive directors.

The case became a landmark in Australian corporate governance because it drilled into a question directors everywhere would rather not face: are you allowed to treat the financial statements as someone else’s problem?

The court’s answer, in effect, was no. Directors are expected to apply their own minds, review the statements carefully, and ensure they’re consistent with what they know about the company’s affairs—and that they don’t omit matters that are material, whether known or reasonably knowable. The higher the office, the greater the responsibility.

Meanwhile, the U.S. chapter of the Centro story ended the way these stories often do: with a sale to deep-pocketed capital.

In 2011, Centro Retail Trust sold its entire U.S. assets and operating platform to BRE Retail Holdings, an affiliate of Blackstone Real Estate Partners VI. The platform ultimately became Brixmor Property Group.

And here’s the bitter irony: the U.S. portfolio that nearly destroyed Centro didn’t turn out to be junk. Brixmor went on to become a thriving, publicly traded REIT owning hundreds of shopping centres across the United States. The assets were never the core problem.

The leverage was.

Back in Australia, the shareholder outcome was brutal. When Centro’s senior debt matured in December 2011, it was cancelled in return for transferring all of Centro’s Australian assets and interests. Securityholders received a distribution measured in cents, not dollars—about five cents per security in total.

Five cents.

For anyone who’d held Centro on the way up—watching it trade around ten dollars—this was wealth destruction on an almost total scale.

And yet, the corporate entity itself didn’t vanish. The operating platform, the people, and the surviving Australian assets still existed. Centro’s name was now radioactive, but the business could still be rebuilt.

Out of that wreckage, something new would emerge.

V. Rising from the Ashes: Federation Centres and the Path to Vicinity (2011–2015)

When you’ve just vaporised billions of dollars of equity and ended up in court, you don’t get to keep trading on the same name like nothing happened.

On 22 June 2013, shareholders of Centro Retail Trust voted to change the company’s name to Federation Centres. It wasn’t a fresh coat of paint. It was triage. “Centro” had become shorthand for reckless leverage, near-collapse, and regulatory prosecution. Tenants didn’t want the association. Capital markets didn’t want the risk. Employees didn’t want the stigma.

But the real reinvention wasn’t in the branding. It was in the strategy that emerged from the wreckage.

Since 2009, the group had been steadily narrowing its portfolio—moving away from convenience retail and toward regional shopping centres, and using the proceeds to fund redevelopments of its core assets. In other words: fewer properties, better properties, and more investment per site.

That pivot mattered because Centro’s original model—owning hundreds of small strip centres—had a built-in weakness. It was operationally messy, easy to replicate, and hard to defend. Small convenience centres couldn’t differentiate in the way big destinations could. They struggled to command premium rents, and they didn’t give shoppers a reason to choose them over the next centre, the next big-box cluster, or increasingly, the internet.

The emerging thesis was simpler and sharper: if retail was going to survive the online era, it would do it by becoming a place people actually wanted to go. Dining. Entertainment. Fashion. Services. Social time. Things that don’t ship in a cardboard box.

The culmination came in 2015, with the merger that created Vicinity Centres.

Vicinity Centres—“the Group”—was formed by the merger of Federation Centres and Novion Property Group on 11 June 2015. The combined entity initially traded post-merger as Federation Centres, then was rebranded Vicinity Centres in November 2015.

The deal had been set in motion earlier that year. On 3 February 2015, Novion entered into a merger implementation agreement to acquire Federation Centres in stock for AUD 7.8 billion.

Novion brought its own history—and a crucial set of relationships. It was an Australian real estate investment trust focused on shopping centres, listed on the ASX in October 1994 by John Gandel as Gandel Retail Trust, starting with six retail assets. For years it was managed by Colonial First State in Sydney under the name CFS Retail Property Trust, until the platform separated in 2013.

That name—John Gandel—turns out to be one of the most important threads in this whole story. Because the merger didn’t just combine portfolios and management teams. It effectively pulled Federation into a world anchored by one of Australia’s most successful retail property developers—and, with it, the crown jewel of Australian shopping centres: Chadstone.

By late 2015, the new identity was formalised. The decision to rebrand was first flagged in June, and the resolution to change names was approved at the group’s AGM on 28 October. Chairman Peter Hay said it was recognised early that the merged group’s name needed to signal a new start. “Vicinity by definition is a ‘place’ name – the place to shop, meet, socialise and experience a great environment – a key destination to bring people together.”

Compared to Centro’s debt-fuelled U.S. sprint, the philosophy couldn’t have been more different. Not maximum leverage and maximum asset count—just to say you were bigger. Instead: concentrate on Australia’s best centres, manage them intensively, and keep investing until they became destinations that went beyond retail.

And at the centre of that plan—literally and strategically—stood Chadstone, the asset that would come to define what Vicinity could be.

VI. The Crown Jewel: Chadstone—Australia's Fashion Capital

Chadstone’s story starts well before Vicinity existed, and even before suburban Melbourne looked anything like it does today. The spark came from overseas.

In 1949, Ken Myer looked to the United States, where decentralised shopping centres were taking off—built for suburbs, built for cars, built for a new kind of family life. After a 1953 visit, where he met architects shaping the modern mall, Myer came back convinced Australia was heading the same way.

Postwar Australia was changing fast, and the Myer family wanted to meet that change head-on. Kenneth and Baillieu Myer poured roughly £6 million into what they saw as an extension of the Myer Emporium: a drive-to, park-once shopping destination. Chadstone was positioned about 13 kilometres south-east of Melbourne’s CBD, with a large and increasingly car-owning population nearby. The centre was aimed at an emerging suburban consumer—especially the “motoring housewife,” as the era’s advertising put it. Even the parking design became part of the pitch: 45-degree angled spaces that made it easier to pull in without reverse parking.

The site, too, was a deliberate choice. Myer initially bought land out at Burwood East, but advice from the American Larry Smith Organisation pointed them further into the south-eastern growth corridor. They ultimately built on a greenfields site at the Convent of the Good Shepherd, surrounded by a middle-class catchment with a strong propensity for family shopping.

Chadstone Shopping Centre opened on 3 October 1960, officially opened by Victorian Premier Henry Bolte. It was the nation’s first self-contained regional shopping centre—and the largest in Australia at the time: about 30 acres, 72 shops, a three-level Myer department store, a supermarket, and parking for 2,500 cars, all built for that same headline cost of roughly £6 million.

The launch wasn’t quiet. The opening drew thousands of prospective shoppers, with many more watching on television. Chadstone wasn’t just a new shopping centre. It was a new model of retail life.

But Chadstone’s leap from a highly successful regional centre to Australia’s undisputed fashion capital came from a single transaction in 1983—one that, in hindsight, looks like one of the great Australian property buys.

In March 1983, the Myer Emporium sold Chadstone to the Gandel Group for $37 million. The Gandel Group has managed and developed the complex ever since.

John Gandel AC—born Aaron Jonna Gandel in 1935—is a businessman, property developer, and philanthropist who built his fortune in retail and commercial real estate in Melbourne. His family were Polish immigrants and founders of the Sussan women’s clothing chain. In the 1950s, Gandel took control of Sussan and, with his brother-in-law Marc Besen, grew it into a chain of more than 200 stores. In 1983, he bought Chadstone, and in 1985 he sold Sussan to Besen to focus on real estate.

When Gandel acquired Chadstone for $37 million, annual sales were around $100 million. And he didn’t wait to get started. Expansion and improvement began almost immediately—and never really stopped.

Over the next decade-plus, Chadstone kept stretching. A cinema complex was added in 1985, and by 1996 the centre had grown to 94,000 square metres of floor space, with a department store, two discount department stores, and hundreds of specialty shops.

Then came the modern era of “Chadstone as city.” On 13 October 2016, the first stage of a $660 million redevelopment opened. The northern expansion was branded “The New Chadstone,” featuring a four-level glass-roofed atrium and a new retail and leisure precinct designed to pull the centre further beyond pure shopping.

By this point, Chadstone wasn’t just big—it was structurally embedded in Australia’s retail landscape. The Gandel Group owns 50 percent of Chadstone. Vicinity owns the other half. Gandel also holds a 17 percent stake in Vicinity Centres.

And the partnership has kept pushing the idea of Chadstone as more than a mall. Chadstone – The Fashion Capital announced a $485m project including a revitalised fresh food precinct, The Market Pavilion, and a new 20,000 sqm commercial office tower, One Middle Road, due for completion in mid-2024.

That’s not a typical mall upgrade. It’s mixed-use city building. One Middle Road includes new arrival, drop-off and pick-up areas, and is designed to plug directly into the centre’s services—like on-site childcare and wellness facilities—while giving office workers immediate access to retail and dining. Chadstone already serviced about 3,900 office workers, and expected to welcome more than 6,000 after completion.

The results speak for themselves. In 2018, Chadstone’s sales hit $2 billion, placing it among the top five best-performing shopping centres in the world. It now has more than 500 stores and more than 80 places to eat across four different food precincts.

From a $37 million purchase to a multi-billion-dollar destination, Chadstone has become one of the most successful retail property investments anywhere. And for Vicinity, it isn’t just a trophy asset—it’s the blueprint: build centres so compelling that people choose to visit, even when shopping online is only a click away.

VII. The Strategic Pivot: From Quantity to Quality (2018–Present)

By the time Grant Kelley became CEO in 2018, Vicinity had already started moving away from Centro’s old instinct to own as much as possible. Under Kelley, that shift stopped being a direction and became a program: fewer assets, higher quality, and a lot more focus on what each centre could become.

A big part of that meant thinking beyond retail-only footprints. Vicinity lined up a $2.9 billion development pipeline aimed at diversifying its centres with mixed-use real estate—major projects that included proposed office towers, and in some cases apartments.

But the clearest expression of the new strategy was what Vicinity chose to sell.

Instead of treating every shopping centre as a permanent holding, the company made divestments central to the plan—systematically exiting assets that didn’t fit its vision of premium, market-leading destinations. It divested non-strategic sub-regional malls, including 50% interests in Elizabeth City Centre, Roselands, and Carlingford Court, raising approximately A$457 million in FY25. That beat its A$250 million target and shifted premium assets to 66% of the portfolio.

Then came the next handoff at the top.

Grant Kelley, CEO from 2018 to 2022, announced his retirement on 31 October 2022. Peter Huddle stepped in as interim CEO and was officially appointed CEO on 31 January 2023.

Huddle had joined Vicinity in March 2019 as Chief Operating Officer before becoming Chief Executive Officer and Managing Director in February 2023. Before Vicinity, he’d built his career inside Westfield, across multiple global markets. Most recently he was COO of Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield, USA after the acquisition of Westfield. Before that, he served as Senior Executive Vice President and Co-Country Head of the USA, leading the U.S. development teams through a prolific expansion period.

It’s hard to find a cleaner résumé for the job Vicinity was now trying to do: operate fewer centres, but run them like destinations—and keep building, carefully, where the returns justify it.

Huddle put it plainly:

"I believe Vicinity has the right strategy in place to deliver long-term growth and, under my stewardship, we will have an even greater emphasis on driving a performance culture that is focused on property excellence, customer centricity, and disciplined capital management.

That last phrase—disciplined capital management—lands differently when you know Vicinity’s origin story. Centro nearly collapsed because it did the opposite: too much leverage, the wrong kind of debt, and acquisitions timed to the peak of a cycle. Huddle’s emphasis wasn’t just a leadership tagline. It was institutional scar tissue.

And it showed up in the actions Vicinity highlighted in FY25: continuing its investment strategy by acquiring 50% of Lakeside Joondalup in Western Australia for $420 million, divesting three non-strategic assets at a blended premium to June 2024 book value of more than 5%, and selectively investing in large-scale retail developments that fit the “premium destination” thesis.

The logic behind that thesis is worth sitting with. Vicinity’s view was that premium, fortress-style assets in strong trade areas—run by specialists, continuously upgraded—can deliver superior and sustained income and value growth. And it pointed to a structural tailwind: an emerging shortage of retail Gross Lettable Area per capita in Australia, driven by population growth, constraints in the construction sector, and limited major tenant expansion.

In other words, the easy story says malls are dying because e-commerce is rising. Vicinity’s bet is more nuanced: if the population is growing, new supply is hard to build, and the best centres keep getting better, then the right physical retail doesn’t just survive. It becomes more valuable.

VIII. The COVID Crucible and the Case for Physical Retail (2020–2022)

If any event was designed to stress-test the idea that physical retail still matters, it was COVID-19. And nowhere did that test bite harder than Melbourne—home to Vicinity’s most valuable asset, Chadstone.

Melbourne became a kind of real-world experiment. In 2020 it endured the second-longest consecutive hard lockdown (after Buenos Aires), and by mid-2022 it held the unenviable record for the most cumulative time spent in lockdown anywhere in the world.

For Vicinity, the impact was immediate and brutal. Quarterly sales fell 32 percent year-on-year, dragged down by the devastation lockdowns inflicted across its portfolio.

When restrictions eased and doors reopened, Vicinity didn’t just turn the lights back on and hope for the best. Across 20 Melbourne centres—including Chadstone, Northland, The Glen, and Bayside—it rolled out wide-ranging COVID safety measures. Social distancing and security officers patrolled centres, working alongside Victoria Police and Protective Service Officers to help keep customers a “healthy distance” apart.

Behind the scenes, the response was even broader. Vicinity moved into emergency mode: rent relief for struggling tenants, enhanced cleaning, crowd-management tech, and even turning car parks into public health infrastructure. It introduced six new drive-thru COVID-19 testing sites across Melbourne as part of the Victorian Government’s push to test up to 100,000 people in two weeks.

At the same time, the e-commerce acceleration thesis hit full volume. If stores were closed, of course shopping moved online. Amazon surged. Mall landlords got lumped in with “stranded assets.” The narrative hardened into something that sounded inevitable: people had learned a new habit, and they weren’t coming back.

But then lockdowns lifted—and the supposedly dead thing did what it’s done for decades. It revived.

People didn’t just want packages on their doorstep. They wanted to leave the house. They wanted dinner out. They wanted to browse. They wanted movies, catch-ups, and a sense of normal life. Shopping centres, especially the good ones, were one of the fastest ways to get that back.

Vicinity later reported a 13 percent year-on-year increase in retail sales across its portfolio of 60 shopping centres in the three months to the end of March, crediting “sustained retail sector resilience and operational execution.”

Peter Huddle framed it as resilience in a tougher consumer environment: “The Australian retail sector has once again demonstrated its resilience in the face of rising household costs and heightening near-term macroeconomic uncertainty,” he said. He also pointed to returning city activity: “It was particularly encouraging to see the positive momentum in CBD visitations during the quarter, which underpinned a 37.2 per cent uplift in CBD sales and, in fact, our CBD portfolio was a key contributor to our overall portfolio sales performance.”

And the pattern inside the numbers was the whole point of Vicinity’s strategy. The premium centres did the heavy lifting. In that quarter, Vicinity’s premium destinations led growth, with sales up 20.3 percent versus the group’s 13 percent.

In other words: the malls that felt like places—luxury, dining, entertainment, “make a day of it” destinations like Chadstone—proved more resilient than centres built around pure convenience and commodity retail. They offered what Amazon never could: the experience of being somewhere special.

IX. The Portfolio Today: An Asset Tour

In Australian retail property, two names dominate the skyline: Scentre Group, the owner of Westfield, and Vicinity Centres. Vicinity’s business is simple to describe and hard to replicate: it collects rent from some of the country’s most valuable retail real estate, led by Chadstone—Australia’s largest shopping centre—which it co-owns with the Gandel Group.

But Vicinity isn’t just “the Chadstone company.” Its portfolio reaches deep into the places where Australians actually spend time and money, including some of the most recognisable retail addresses in the country. Vicinity’s 59 shopping centres include seven premium CBD assets across Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane, anchored by the heritage-listed Queen Victoria Building—part mall, part landmark, and a magnet for tourists. Vicinity co-owns the QVB, The Strand Arcade, and The Galeries with Hong Kong’s Link REIT, which bought a $538 million half-stake in 2021. Beyond Sydney, the portfolio includes standout CBD assets like Myer Bourke Street and Emporium in Melbourne, plus QueensPlaza and the Myer Centre in Brisbane.

Those heritage CBD centres are a very intentional bet. They were hit hard during COVID, when office workers stayed home and international tourism vanished. But unlike a typical suburban box of shops, these buildings can’t be duplicated. As city life and tourism return, they offer something close to the purest form of scarcity value in retail property.

Vicinity also has a different kind of “premium” exposure through its DFO (Direct Factory Outlet) portfolio. Outlet centres sell a simple promise—brands at discounted prices—and that proposition tends to get stronger when cost-of-living pressures rise and households become more value-conscious.

A key enabler across the portfolio is Vicinity’s strategic partners model. It allows the company to earn management fees while sharing the capital burden of ownership. In other words, it’s a structural answer to the lesson Centro learned the hard way: growth is great, but not if it forces you into over-leverage. With partners alongside it, Vicinity can participate in more opportunities without carrying all the financial risk on its own balance sheet.

And then there’s the next frontier: mixed-use.

Following the NSW Government’s approval of the Bankstown Rezoning Proposal in November 2024 under its Transport Oriented Development program, Vicinity was positioned to advance residential development next to Bankstown Central and the new Metro station, due to commence services in 2026. Chatswood Chase also emerged as a near-term mixed-use opportunity, with Vicinity owning two properties directly adjacent to the centre. At both Bankstown Central and Chatswood Chase, proposed high-density residential sites were endorsed for inclusion in the Housing Development Authority’s accelerated assessment pathway, creating an expedited planning process. Together, they stand out as strategically located assets with the potential to deliver new housing in high-demand urban precincts.

This is the bigger evolution underneath Vicinity’s “destination” strategy. The best shopping centres sit on huge land parcels in places that have become increasingly valuable—well-served by transport, surrounded by established suburbs, and starved for new housing supply. If you can add apartments, offices, and community uses alongside retail, you don’t just build a better mall. You build a more complete precinct—one that generates foot traffic beyond shopping hours and creates value in more ways than rent alone.

X. Competitive Landscape and Strategic Analysis

To understand Vicinity’s position, you have to see the playing field it operates on: Australia’s retail REIT market is dominated by a few scaled landlords fighting over the same things—great sites, the best tenants, and affordable capital.

The biggest presence is Scentre Group, which owns and operates Westfield shopping centres in Australia and New Zealand after the 2014 demerger of Westfield Group. It’s the giant of the category, with a portfolio of 42 centres valued at $50.1 billion, home to more than 12,000 retailers.

In practical terms, that means Scentre brings the larger market capitalisation, the bigger asset base, and the gravitational pull of the Westfield brand. But Scentre and Vicinity don’t map perfectly onto each other. Westfield is heavily oriented toward large regional destinations. Vicinity competes there too, but it also leans into a broader mix: premium CBD assets, outlet centres, and more community-style shopping.

Then there’s GPT Group. With $34 billion in assets under management, it’s one of the largest REITs in Australia, and it’s especially known for prime office towers in markets like Sydney and Melbourne. It’s also notable for a 5.42% dividend yield, one of the highest on the list.

But GPT is a different proposition. It’s diversified—office, logistics, and retail—rather than a focused retail landlord. If you want a purer bet on Australian shopping centres, Vicinity is more concentrated exposure.

And of course, it isn’t just those two. ASX-listed property trusts like GPT Group (GPT), Mirvac (MRV), and Stockland (SGP) also own malls. Moody’s analysts covering Vicinity and Scentre have pointed out the near-term macro reality: retail sales, and therefore tenant earnings, are expected to moderate under higher interest rates and ongoing cost-of-living pressures. When households tighten, landlords feel it indirectly—through leasing negotiations, incentives, and tenant health.

One clean way to frame these dynamics is Porter's Five Forces:

Threat of New Entrants: LOW. Building a new regional shopping centre takes enormous capital, years of planning approvals, and the rarest ingredient of all: the right land in an established catchment. You can’t simply “build another Chadstone.” The transport links, the surrounding density, and the centre’s position in consumer habits were earned over decades. That scarcity protects incumbents.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Tenants): MODERATE-HIGH. The biggest anchors—Myer, David Jones, Coles, Woolworths, Kmart—pull foot traffic, and they know it. International luxury brands can also pick and choose between competing premium centres. But the leverage isn’t one-way: in the very best locations, space is limited. Premium assets like Chadstone reportedly have waiting lists, which flips the negotiating posture back toward the landlord.

Bargaining Power of Customers (Shoppers): MODERATE. Shoppers can always defect—to online, to a competing centre, to high-street retail. But the more a centre becomes a destination, the less it feels like a commodity. For dining, entertainment, and social “make a day of it” trips, physical centres still win on experience. Across Vicinity’s portfolio, that translates into scale: around 390 million customer visits annually.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH. E-commerce is the structural substitute for commodity retail, and it’s not going away. But the substitution threat drops in categories where experience matters—food, entertainment, services, and luxury, where touch, fit, and immediacy still count. Vicinity’s strategy is built around that distinction: tilt the portfolio toward the parts of retail that can’t be fully digitised.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH. Rivalry is intense—for tenants, for redevelopment opportunities, and for investor capital. The competitive pressure shows up in transactions and joint ventures that keep capital flowing into the best assets, which in turn keeps the bar high on pricing, cap rates, and returns.

If you instead look at Vicinity through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers lens, the company’s most defensible edges aren’t abstract—they’re physical.

Cornered Resource: Chadstone is the definition of a cornered resource. There is only one, and Vicinity owns half. The same is true, in a different way, for heritage CBD assets like the Queen Victoria Building and the Strand Arcade: iconic, scarce, and effectively impossible to replicate.

Scale Economies: Vicinity’s national platform creates real operating advantages—leasing capability, tenant relationships, development expertise, and the ability to spread corporate costs across a large base in a way smaller owners can’t match.

Switching Costs: Tenants that have spent heavily on fitouts, staffing, and local customer awareness don’t move lightly. Even when leases roll, relocation is expensive and risky, which creates a quiet but meaningful form of stickiness.

Where Vicinity is less naturally advantaged is in the “tech-style” powers. There’s no obvious network effect. There’s no clear counter-positioning. Brand power exists, but it lives mostly at the asset level—Chadstone, DFO, Emporium—rather than in the Vicinity corporate name itself.

Which, in a way, is the punchline of the whole story: in retail property, the moat is often the place.

XI. Key Risks and Considerations

For all of Vicinity’s progress—and for all the advantages of owning scarce, high-quality places—the business still lives at the intersection of retail, real estate, and capital markets. That’s a powerful combination when conditions cooperate, and a punishing one when they don’t.

Any assessment of Vicinity has to grapple with a few risks that never really go away:

E-commerce Disruption: Even after the post-COVID rebound, the long-term direction of online retail is still up. Entire categories—electronics, books, and a lot of commodity apparel—have already moved permanently toward e-commerce. Vicinity’s bet is that experience-heavy and service-oriented retail stays defensible. But that isn’t a “set and forget” moat. It has to be reinforced, year after year, through tenant mix, upgrades, and making each centre feel like a place people choose, not a place they default to.

Interest Rate Sensitivity: REITs are, by design, exposed to interest rates in more than one way. Higher rates push up borrowing costs and make safer yield alternatives more attractive to investors, which can pressure property values. Vicinity’s balance sheet is far more conservative than Centro’s ever was—but it still has debt, and debt still has maturity dates. Refinancing happens at whatever the market is charging at the time.

Tenant Concentration: Big anchors matter. They drive meaningful rent, but just as importantly, they drive foot traffic. Department stores like Myer have faced structural pressure for years, and that fragility shows up as landlord risk. If a major anchor closes, downsizes, or renegotiates aggressively, the impact is rarely contained to one lease—it can ripple through specialty tenants who rely on that traffic.

Development Execution: The strategy relies on building. Major projects at Chadstone, Chatswood Chase, and other centres have to land on time and on budget, and then perform as expected. Construction cost inflation, contractor capacity, and planning and approval delays can turn a great-looking redevelopment spreadsheet into a headache.

Economic Sensitivity: Shopping centres ultimately ride on household confidence. When cost-of-living pressures rise, discretionary categories are usually the first to feel it. Even if occupancy holds up, leasing spreads, incentives, and tenant health can move in the wrong direction quickly in a weak consumer environment.

Melbourne Concentration: Chadstone is Vicinity’s crown jewel—and that’s both an advantage and a concentration risk. With meaningful exposure to Victoria, any Melbourne-specific shock, whether economic or demographic, would hit Vicinity harder than a more geographically balanced landlord.

XII. Financial Performance and Key Metrics

After the lockdown shock, Vicinity’s numbers started telling a familiar story for a property business that survived a crisis: stabilise the base, get occupancy back, and let the compounding do the rest.

In FY25, Vicinity reported statutory net profit after tax of $1,004.6 million, up from $547.1 million in FY24. Funds From Operations rose 1.4% to $673.8 million, and when you adjust for one-off items and the higher rent lost to development works, FFO was up 3.6%. At 14.8 cents per security, Vicinity landed at the top end of its guidance range.

Revenue also moved higher in 2025, rising to $1.38 billion from $1.31 billion the year before. Earnings jumped sharply to about $1.00 billion.

If you’re watching whether the strategy is working in the real world—not just on investor decks—there are three KPIs that matter most:

1. Occupancy Rate: At 99.4% across the portfolio, this is the simplest signal of demand for Vicinity’s space. When occupancy is high, it’s a sign tenants still want to be in these centres. If this starts sliding, it’s usually an early warning that leasing conditions are softening.

2. Comparable Sales Growth: This tracks sales performance at established centres, stripping out the distortion of new developments. It’s effectively a read on tenant health. Growing sales make rent increases more sustainable and reduce the risk of tenant failures.

3. Premium Asset Mix: This is the portfolio-shaping metric that tells you whether Vicinity is actually becoming the “fewer, better centres” company it says it is. Premium assets—Chadstone, the outlet portfolio, CBD centres, and Lakeside Joondalup—now make up about 66% of the portfolio, and management has signalled it wants that share to rise.

Put together, the message from FY25 was straightforward: a roughly $1 billion statutory profit, rising distributions, and momentum heading into the next year.

For FY26, Vicinity guided to 15.0 to 15.2 cents per security in funds from operations—modest growth, but in line with the idea that as developments complete and the portfolio keeps upgrading, the earnings base should keep inching upward.

XIII. What Investors Should Watch

The Vicinity Centres story is, at its core, a reinvention story. A business that once nearly destroyed itself with leverage and an ill-timed land grab has rebuilt into something far more deliberate: a focused owner and operator of premium Australian retail destinations.

If you want the bull case in plain English, it comes down to a few big ideas. First, some assets are simply irreplaceable—Chadstone being the obvious example. Second, Australia’s population keeps growing while it’s become harder to add meaningful new retail supply, which supports the best centres. Third, the kinds of retail that are hardest to digitise—food, entertainment, services, luxury, “make a day of it” shopping—tend to concentrate in exactly the sort of destination assets Vicinity is prioritising. And finally, there’s the upside option: mixed-use development. The land under these centres can be worth more when it supports offices, hotels, and potentially housing, not just shops.

The bear case is the mirror image. E-commerce can still take more share, especially in the more commoditised retail categories. Higher interest rates can pressure both funding costs and property values. Tenant health can deteriorate quickly in a weak consumer environment. And it’s possible that some of the post-COVID bounce was just a release valve—pent-up demand—rather than a durable shift back toward physical retail.

In the market today, neither view is a clear consensus. Morningstar has three-star ratings on both Vicinity and Scentre, implying they’re trading around fair value. As Morningstar’s Prineas put it: “We do view them as high quality, but we think a lot of that is priced in.”

For long-term fundamental investors, Vicinity is essentially a bet on premium places—backed by a management team that carries institutional scar tissue. The Centro collapse is still recent enough to function like a corporate immune system: a constant reminder of what happens when financial engineering replaces operational excellence.

And that leaves the real question, the one you can’t spreadsheet away. In a digital world, do people still want to go somewhere? If the answer is yes, Vicinity’s best assets can keep compounding. If the answer is no, even trophy centres can start to look like value traps. The next decade will settle it—and Chadstone, now entering its 65th year, will likely remain right at the centre of the verdict.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music