TechnologyOne: Australia's Quiet Software Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

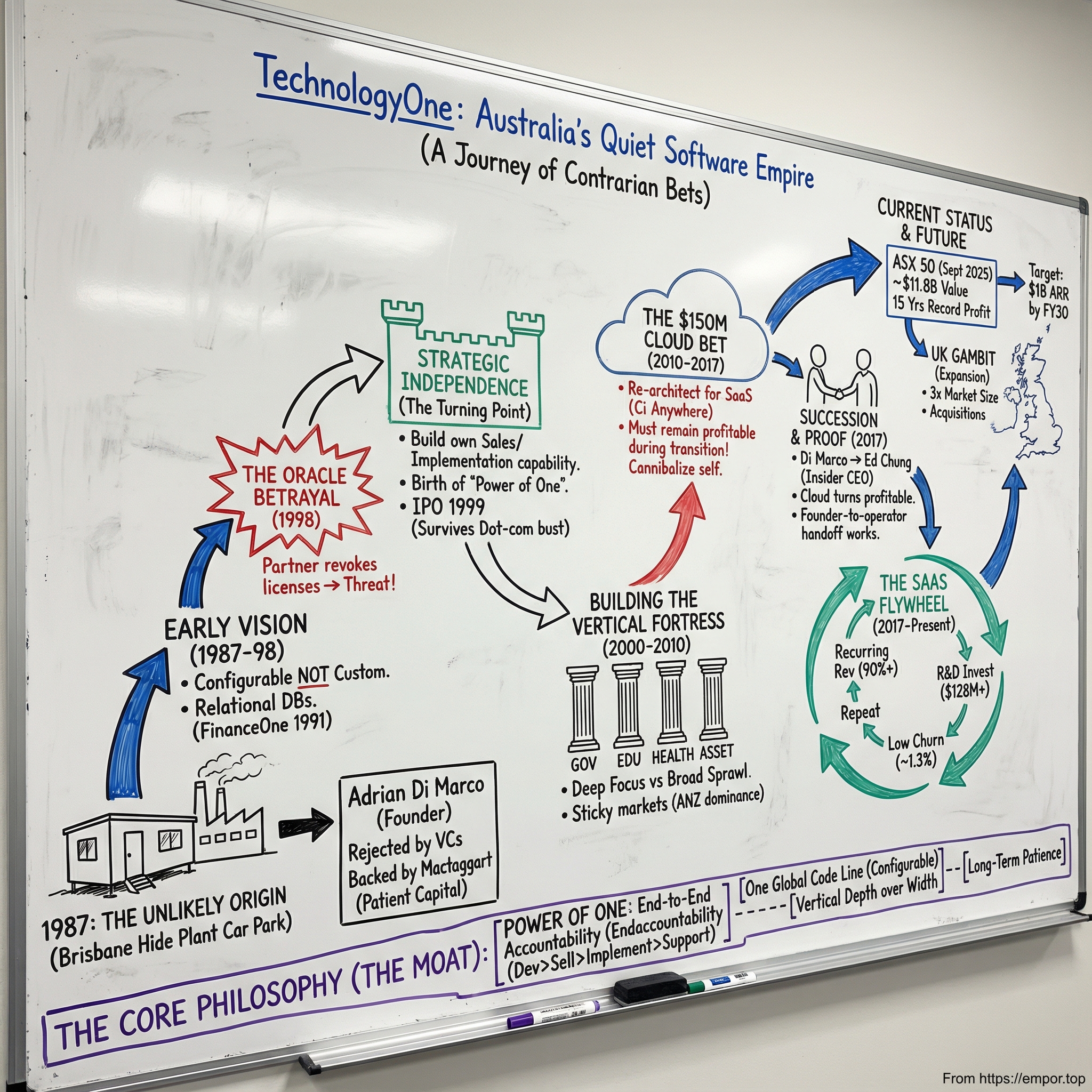

Picture this: suburban Brisbane, 1987. Out in the car park of a hide processing plant, there’s a demountable office—thin walls, fluorescent lights, the faint sting of tanning in the air. Inside, a 29-year-old son of Italian immigrants is hunched over a computer, building what most people around him think is an impossible product: Australian-made enterprise software that can stand up to the global titans. He’s already been turned down by venture capital. The pitch sounds naïve on paper. Compete with Oracle? With SAP? From Brisbane?

And yet, that’s exactly what happened.

Nearly four decades later, that scrappy operation became TechnologyOne (ASX: TNE). For the year ended 30 September 2024, the company’s results cemented what’s easy to miss if you only pay attention to Silicon Valley: TechnologyOne is Australia’s largest ERP SaaS company. It has delivered 15 consecutive years of record profit, alongside record revenue and record SaaS fees. By November 2025, the market had priced it like the rare compounding machine it is—worth around A$11.8 billion—and in September 2025 it entered the ASX 50.

So here’s the question that makes this story worth telling: how did a company born in a demountable office beside a hide factory become one of the world’s most successful vertical SaaS ERP businesses, in a category where SAP and Oracle have dominated for decades?

The answer isn’t a single breakthrough. It’s a sequence of decisions—contrarian ones—stacked on top of each other. A belief in building configurable products rather than custom one-off projects. A refusal to sprawl across every industry, choosing instead to go deep in a handful of verticals. A company structure that insisted on owning the whole customer experience, end to end. And a willingness to cannibalize its own business before someone else did.

TechnologyOne’s track record is almost unnerving in its consistency. From 1999 to 2019, it doubled in size every five years. Its “Power of One” model—develop, sell, implement, and support everything yourself—created a moat in its core markets that the multinationals have struggled to cross. And then there’s the cloud transition: one of the hardest moves a profitable enterprise software company can attempt, and one TechnologyOne executed while staying profitable.

This is the story of Adrian Di Marco’s stubborn vision; the Oracle betrayal that forced TechnologyOne to become truly independent; the $150 million cloud bet that reshaped the company; and the rare founder-to-operator handoff that set up its next era of growth.

II. The Founder's Origin: Adrian Di Marco & The Hide Factory

TechnologyOne’s story doesn’t start in a gleaming office tower or a university lab. It starts in Brisbane, in an industry that couldn’t feel further from enterprise software: hides.

Adrian Di Marco was born in Brisbane in 1958, the child of Italian immigrants, and attended St James College. His first real brush with computing came early and a little sideways—by helping his older brother, who was studying engineering at university, program one of the first digital computers. That experience didn’t just teach him how machines worked. It hooked him on the idea that software could make complicated systems behave.

After high school, Di Marco studied science at the University of Queensland, majoring in computer science. He then joined Arthur Andersen (now Accenture), where he got a front-row seat to how big organizations bought and deployed software. He saw the pattern: huge implementations, lots of customization, and systems that became brittle over time because every “special request” turned into permanent complexity.

Then came the moment that’s become company legend: Di Marco cut his honeymoon short to chase down a contract to computerise a hide factory in Brisbane.

He got the job. And it turned out to be far tougher than he expected. So he did what he would later demand of TechnologyOne: he stayed with it. He worked weekends to finish the project, grinding through the messy reality of making software work in the real world, not in a demo.

That effort didn’t go unnoticed. The factory’s owner had been watching quietly. His name was John Mactaggart of JL Mactaggart Industries, and what he saw wasn’t just a young developer writing code. He saw someone willing to do whatever it took to deliver. For Di Marco, it became an early, permanent lesson: reputation compounds, and in business it’s everything.

In 1987, Di Marco founded TechnologyOne from a demountable office in the car park of JL Mactaggart Industries’ hide processing plant in Hemmant, Brisbane. It’s hard to imagine a more unlikely birthplace for an enterprise software company: cutting-edge development happening beside one of Australia’s most traditional industrial operations. But that odd pairing mattered. It gave Di Marco something far rarer than a flashy launch—room to build.

Because before Mactaggart stepped in, the fundraising story was mostly rejection. Di Marco did the usual rounds for venture capital, but Australian investors weren’t interested in backing a local company taking on global giants like Oracle and SAP. The assumption was simple: you can’t beat multinationals from Brisbane. Not in software. Not ever.

The Mactaggart family made the bet anyway. They backed TechnologyOne at the beginning, and they stayed partners for decades. And the support wasn’t just financial. It was patient capital, credibility, and the kind of steady belief that lets a founder focus on product instead of survival.

Even in those early years, Di Marco’s instincts didn’t line up with conventional corporate playbooks. He argued against companies being run by “professional managers,” and later he would say that an obsession with corporate governance can weaken businesses—that deep subject-matter expertise on a board matters more than independence for its own sake. Those views put him out of step with mainstream thinking, and they would create tension at times. But they also shaped a culture that valued conviction, craft, and long-term building.

The hide factory origin story isn’t just a quirky anecdote. It’s the blueprint for TechnologyOne’s DNA: start wherever you have to, earn trust by delivering, partner with people who will back the long game, and don’t let conventional wisdom talk you out of what you know is true.

III. The Early Vision: Relational Databases & Configurable Software (1987–1999)

When Adrian Di Marco founded TechnologyOne in 1987, enterprise software was still built on a painful assumption: every customer was unique, so every customer’s system had to be unique too. The technology underneath was often rigid, built on hierarchical databases, and the way you “won” deals was by promising customization. Lots of it. It worked, sort of—until it didn’t. Each new customer became another one-off codebase to maintain, another upgrade that broke, another implementation that ran long.

Di Marco looked at that mess and saw an opening.

Relational databases were starting to become practical for serious enterprise applications, and Di Marco believed they could support something far more ambitious than just better accounting. He wanted a new generation of software for businesses and government departments—software that could adapt to customers without being rewritten for them.

The real breakthrough wasn’t just the database choice. It was the architecture.

Instead of modifying source code for every client, TechnologyOne pioneered a concept that sounds obvious now but wasn’t then: configurable software. One global code line for everyone, with each customer’s setup handled through configuration that lived outside the code. That separation mattered. It meant customers could get what they needed without turning the product into a tangled, bespoke project. It meant upgrades could happen without dread. And it meant TechnologyOne could build and improve one product, instead of babysitting hundreds of slightly different versions.

From the demountable office back at Mactaggart’s hide processing plant in Hemmant, the team began building on Oracle’s relational database—a decision that helped them move fast early, and would later come back in a way they couldn’t yet imagine.

By 1990, TechnologyOne had already pushed further: it achieved database independence, supporting multiple RDBMS platforms like Ingres, Sybase, and Informix. On the surface, it was about flexibility and customer choice. Underneath, it was a statement about control. TechnologyOne was building a product that wouldn’t be hostage to anyone else’s platform.

In 1991, the philosophy became real in a shipping product: FinanceOne. It paired global code with customer-specific configurations stored in the database, and it became the foundation of TechnologyOne’s enterprise suite—still central to the business today.

The early 1990s also delivered proof that this approach could win serious, high-stakes customers. TechnologyOne built the Automated Titling System (ATS) for the Queensland Department of Natural Resource & Mines, an important government contract that helped set the company on a path toward the public sector.

Then, in 1992, it built a student administration system for TAFE Queensland: the College Administration System. That work became the seed for StudentOne (now TechnologyOne Student Management), which would go on to be used by Australian universities. Long before “vertical SaaS” became a phrase, TechnologyOne was quietly doing it—solving hard, specific problems for industries that had real complexity and long time horizons.

The big credibility moment arrived in 1995, from a place that mattered to buyers: CFO magazine’s customer satisfaction survey. TechnologyOne ranked first, ahead of Oracle and SAP. For a Brisbane company competing with global giants, that wasn’t just flattering—it was ammunition. The result went straight into the marketing, growth accelerated, international orders started coming in, and TechnologyOne opened offices around Australia.

A pattern was forming. TechnologyOne wasn’t going to outspend Oracle or SAP. It wasn’t going to win by being everywhere. It would win by being better for the customers it chose, and by making software that didn’t collapse under the weight of customization.

By the late 1990s, TechnologyOne had become a real contender in Australian enterprise software. And just as it was finding its footing, the defining test of its independence was about to arrive—not as a market opportunity, but as a betrayal.

IV. The Oracle Betrayal & Strategic Independence (1998–1999)

Every enduring company has a moment where the ground shifts under its feet—when a comfortable dependency turns into an existential threat. For TechnologyOne, that moment came in 1998. And the threat came from Oracle.

For years, TechnologyOne had built on Oracle’s database technology. It was a logical foundation at the time: powerful, trusted, and widely adopted. Then Oracle did what giants do when they smell an attractive niche. It launched a competitor product—and revoked TechnologyOne’s licences.

It was the kind of move that could have ended the story right there. But instead of folding, Adrian Di Marco treated it like a forced upgrade of the entire company. TechnologyOne pushed hard into database independence, ensuring its products could run without being tied to Oracle. At the same time, Di Marco doubled down on something even more consequential: building TechnologyOne’s own sales, marketing, and implementation capability in-house.

That combination—technical independence plus commercial independence—became the company’s core identity. The lesson was simple and permanent: never again let the business depend on a partner, distributor, or platform provider who can wake up one morning and decide they’re your competitor.

Out of that crisis came what TechnologyOne would later call the “Power of One” philosophy: one company owning the whole customer journey—developing the product, marketing it, selling it, implementing it, and supporting it.

That was not the standard playbook. The prevailing model in enterprise software was to scale through resellers, system integrators, and implementation partners. It was faster. It was less capital intensive. And it let the software vendor focus on product while other people did the messy work of delivery.

But it also meant giving up control of the customer experience. It meant customers could love—or hate—the implementation partner and blame the software. And it meant your growth engine depended on third parties whose incentives didn’t always match yours.

TechnologyOne went the other way. It was counterintuitive and expensive. It likely meant slower scaling in the short term. But it also meant TechnologyOne owned the relationship, owned the outcomes, and built a reputation it could actually defend.

And then, almost immediately after being forced to reinvent itself, TechnologyOne stepped onto an even bigger stage.

In December 1999, Di Marco led the company onto the Australian Securities Exchange. Technology One Limited listed on 8 December 1999 at $1.00 a share—right at the height of the dot-com era, when “technology” stocks were being priced on hope as much as fundamentals.

TechnologyOne was different. This wasn’t a concept slide deck or a traffic story. It was a profitable, growing enterprise software business with real customers, real implementations, and a product philosophy that had already been stress-tested by Oracle’s betrayal.

The timing cut both ways. Riding the wave of public-market enthusiasm helped, but surviving what came next mattered more. In October 2000, the company raised $18 million from institutional investors including Hyperion Asset Management, Selector Funds Management, Pendal Group, and others—capital that would help provide resilience as the dot-com bubble burst.

When the market turned in 2000 and 2001, plenty of newly listed tech companies didn’t make it. TechnologyOne did, largely because it wasn’t built on hype. It was built on customers and cash flow.

By the end of this chapter—Oracle turning from partner to threat, TechnologyOne forcing itself into independence, and then stepping into the scrutiny of the public markets—the company had quietly locked in principles that would shape the next few decades: control your own destiny, stay relentlessly accountable for customer outcomes, and build defensibility through focus rather than sprawl.

Those principles would become the scaffolding for TechnologyOne’s next move: going deep into a few verticals and building a fortress there.

V. Building the Vertical Fortress: Focus on Government & Education (2000–2010)

After surviving the dot-com bust, TechnologyOne could have done what most ambitious software companies do next: broaden the product, chase bigger logos, and try to be everything to everyone.

Instead, it made a decision that would define its competitive position for decades. TechnologyOne went deep rather than wide.

While global ERP vendors like Oracle and SAP built broad platforms aimed at every industry, TechnologyOne focused on six vertical markets: Education, Local Government, Government, Health & Community Services, Asset & Project Intensive industries, and Corporate/Financial Services. The point wasn’t to narrow the company’s ambition. It was to concentrate it—so the software could come “out of the box” with the workflows, compliance needs, and reporting reality these sectors actually lived with.

That was a bet against the prevailing playbook in enterprise software. The industry’s default model was to sell a general-purpose system, then rely on customization and partners to make it fit. In theory, that approach meant unlimited addressable market. In practice, it often meant costly implementations, messy upgrades, and customers stuck with systems that never quite felt like they were built for them.

TechnologyOne aimed for the opposite: become the definitive system of record in specific markets, where once you’re embedded, you tend to stay embedded.

This strategy wasn’t dreamed up in a vacuum. It emerged from where the company was already winning, and from Australia’s economic reality. Local government, education, and state and federal departments were stable, recurring markets with very specific requirements—requirements global vendors frequently treated as edge cases. They weren’t flashy sectors. But they were large, underserved, and incredibly sticky once a vendor earned trust.

By 2005, that focus sharpened further. TechnologyOne shifted from functionality-centric software to people-centric software—building around how users in these industries actually worked, rather than around what looked impressive in a product checklist.

The company also used acquisitions as a way to deepen, not distract. In 2000, it acquired Proclaim, strengthening its local government footprint. In 2007, it acquired Avand, adding enterprise content management and document capabilities that mattered in government and education environments. The pattern was consistent: tuck in products that made the vertical offering more complete, not random expansion into new categories.

TechnologyOne was also starting to look beyond Australia, but in its own style: cautiously. In 2006, it opened its first UK office in Maidenhead. There was no blitzscaling land grab here. Enterprise software doesn’t work that way. Winning in a new country takes local credibility, relationships, and a deep understanding of how institutions actually operate.

By the end of the decade, the vertical strategy was showing up in market penetration that’s hard to achieve anywhere, let alone against global incumbents. More than 73% of people in Australia and New Zealand lived in a council powered by TechnologyOne software. It supported over 6.5 million students globally, and its systems were used across a majority of higher education in Australia, New Zealand, and the UK. It was also trusted by more than 230 government departments and agencies.

Those aren’t the results of being “good enough.” They’re what happens when you build a product that fits the customer better than the generic alternative—and then you control the end-to-end experience through implementation and support.

In 2010, TechnologyOne put a physical marker down on what it believed about the future. It moved into a new $12 million headquarters in Brisbane, including what was then the largest Australian-owned R&D facility. It was a statement: this company wasn’t going to relocate its brain to Silicon Valley to be taken seriously. It was going to build world-class enterprise software from Brisbane, on its own terms.

Not everything about this period was smooth. Di Marco’s contrarian views on governance and “professional managers” created friction, particularly in the early 2000s, and the tension between founder conviction and public-company expectations never fully went away. But the operating results kept reinforcing the same message: focus was working. The company was compounding, profitability was consistent, and its grip on chosen verticals kept tightening.

By 2010, TechnologyOne had built something rare: a fortress of deep vertical positions in enterprise markets that don’t churn. But the ground under enterprise software was about to shift again. And TechnologyOne faced the next great question: defend the on-premise castle that made it successful—or spend heavily to rebuild the whole thing in the cloud.

VI. Inflection Point #1: The $150 Million Cloud Bet (2010–2017)

The years between 2010 and 2017 were the most strategically consequential stretch in TechnologyOne’s history. The company ran straight at a transition that has wrecked countless software incumbents: moving from high-margin on‑premise licences to cloud-delivered SaaS—without blowing up profits along the way.

In November 2010, TechnologyOne announced it would make its software available on the cloud. This was early. Years before many enterprise vendors stopped dismissing cloud computing as a fad, Di Marco and his team made the call that the cloud wasn’t just a new place to host software. It would change how software was bought, consumed, upgraded, and judged.

Then they did the hard part: they funded it.

TechnologyOne poured investment into R&D to move its suite to SaaS, ultimately spending $150 million building its cloud products. For a company of its size, this wasn’t a side project. It was a wager of multiple years of earnings on a future that wasn’t guaranteed.

In 2012, they made the commitment explicit and public: $150 million over five years to develop cloud products. From that point on, TechnologyOne set out to transition the business from an on‑premises provider into a SaaS company. It was a message to everyone who mattered—customers, employees, and investors—that this wasn’t “wait and see.” It was all-in.

Plenty of companies eventually made the same strategic decision. TechnologyOne’s difference was execution. It kept the business profitable through the transition while migrating existing customers and still winning new deals.

In 2014, the first iteration of TechnologyOne’s cloud software launched, giving customers access via the cloud. The company also released Ci Anywhere, a cloud-hosted version of its Connected Intelligence product that worked across desktop and mobile. This wasn’t “our old software, hosted somewhere else.” It was the product being rebuilt for a different era.

That same year, the market rewarded the direction of travel. TechnologyOne reached a $1 billion market capitalisation and entered the S&P/ASX 200—milestones that reflected growing confidence that the cloud bet wasn’t reckless. It was working.

Under the hood, the key choice was architectural. TechnologyOne re-architected its ERP for a multi-tenanted global SaaS model, with customers running on the same codebase. That mattered because it unlocked the economics SaaS is supposed to have: improvements roll out to everyone, security patches can be deployed fast, and the platform gets cheaper per customer as it scales. It also reinforced the company’s “Power of One” instinct—TechnologyOne could take full responsibility for building, implementing, and running the software because the model made that feasible.

Di Marco later summed up the philosophy behind the rewrite: “It has been an amazing journey as we have navigated successfully across four major technology paradigm shifts, starting first with the advent of Relational Database technology, then the PC, the internet and more recently the Cloud. At each stage we have had the conviction and courage to rebuild our products and our business to adapt to a new world.”

Mobile was part of that shift too. TechnologyOne rebuilt its ERP to enable any-device, anywhere access, with full functionality available across devices, including mobile phones. Ci Anywhere, released in 2014, was a visible expression of that.

None of this came out of nowhere. Regular product renewals had become a feature of how TechnologyOne operated: early adoption of relational databases, then client/server, then the web, and finally a full rewrite for the cloud. The company kept choosing to cannibalize its own past before competitors could do it for them—a discipline that separates survivors from legacy vendors who cling to yesterday’s margins until they’re forced into tomorrow at the worst possible time.

By 2017, the cloud investment was clearly starting to pay off—but the bigger payoff still lay ahead. The real achievement of this era wasn’t just technical. It was managerial and cultural: sustaining profitability while spending heavily to rebuild the future. Many enterprise software companies have torched shareholder value trying to make this leap. TechnologyOne showed that, with focus and execution, you could transform without burning down the house.

VII. Inflection Point #2: The CEO Succession & Cloud Profitability (2017)

In 2017, TechnologyOne faced a different kind of high-stakes transition. Not a new database. Not a new market. A new person in the top job.

After three decades with Adrian Di Marco as CEO, the company had to prove something every founder-led business eventually confronts: was TechnologyOne’s success locked inside one individual—or had it been baked into the culture, the systems, and the way the company ran?

In May 2017, Edward Chung was appointed Chief Executive Officer. He wasn’t an outsider brought in to “professionalize” the company. Chung had already spent more than 10 years in senior executive roles at TechnologyOne, including around a year and a half as Chief Operating Officer. This wasn’t a sudden handover; it was a deliberate succession plan. Di Marco had been grooming Chung to take the reins, aiming for continuity in strategy and standards, but with new energy at the helm.

For Di Marco, stepping down was its own milestone. When he moved out of the CEO seat in May 2017, he was one of the longest-serving chief executives of an ASX-listed company. His tenure had spanned the whole arc: the demountable office beginnings, the IPO, the Oracle rupture, the vertical push into government and education, and then the decision to rebuild for the cloud.

Chung’s advantage was that he’d been in the engine room for the most important transformation of them all. From 2014, he led TechnologyOne’s Products and Solutions division, including R&D, and helped drive the transition toward a SaaS-based organisation. He also led the Finance and Corporate Services division and developed commercial frameworks to support the company’s expansion. In other words: he understood both sides of the bet—the technical rewrite and the business model rewrite.

Then, almost on cue, came the proof point investors were waiting for.

At the company’s full-year results on 21 November 2017, TechnologyOne announced that its cloud business had turned profitable for the first time: a $2.5 million profit for the year to September, along with 112 new cloud customers signed. After years of heavy investment, the numbers finally signaled that the SaaS transition had crossed from “build” to “scale.”

Chung also leaned hard into the people side of the business—protecting the culture that had made TechnologyOne unusually execution-oriented, while keeping it inventive. He often pointed back to early career advice that stuck with him: “Surround yourself with the best.” Not just the most talented people, but the people with the passion and drive to deliver. As he told The CEO Magazine, the goal was a team that “love what they do” and “work hard to ensure we are delivering the best products and the best experience for our customers.” High standards, but with momentum.

That emphasis showed up in rituals meant to keep the company from calcifying. Twice a year, TechnologyOne ran an all-company “hack day,” where teams paused day-to-day work to focus on new ideas and better ways of doing things. It was a simple mechanism, but an important one: a reminder that innovation wasn’t confined to R&D, and that even a scaled enterprise software company could still behave like a builder.

Strategically, Chung intensified the SaaS push—continuing the work of re-architecting TechnologyOne’s ERP platform for cloud delivery and maintaining a customer-centric approach to implementation. The key outcome wasn’t just that the product moved to the cloud. It was that TechnologyOne stayed profitable while doing it, something many enterprise software companies fail to pull off.

TechnologyOne has said that no other ERP company in the world has transitioned to the cloud without impacting customers and/or profit growth. That’s hard to independently verify as an absolute claim. But what is clear is that TechnologyOne’s results through the transition helped make the statement feel plausible—because the usual pattern in ERP is ugly: cloud rewrites that drag on, customer disruption, and profitability cratering. TechnologyOne’s story looked different.

And importantly, Di Marco didn’t vanish. After stepping down as CEO, he remained Executive Chairman and Chief Innovation Officer, providing continuity without taking the wheel back. It became a two-phase handover: first, operational leadership; later, governance leadership.

By the end of 2017, the company had done two rare things at once: it made the cloud profitable, and it proved the business could run—well—without its founder as CEO. For long-term investors, that was a different kind of inflection point. It meant TechnologyOne wasn’t just a founder story anymore. It was a system that could keep compounding.

VIII. The SaaS Flywheel: Execution Excellence (2017–Present)

With cloud profitability proven and Edward Chung in the CEO seat, TechnologyOne entered the part of the story everyone wants—but few companies actually reach: the flywheel years. The SaaS model started doing what it’s supposed to do. Recurring revenue created room to keep investing. Investment improved the product and delivery. That, in turn, made it easier to win customers, keep customers, and repeat.

By December 2019, about half of TechnologyOne’s business was in the cloud. Zooming out, the broader compounding pattern was still intact too: from 1999 to 2019, the company doubled in size roughly every five years. In 2020, TechnologyOne said half of its customers had moved from on‑premise to SaaS, and about 86% of revenue was subscription-based—meaning the business was increasingly built on repeatable, predictable fees rather than one-time licence deals.

A big reason that transition didn’t turn into chaos was that TechnologyOne treated migration like a product in itself. After moving more than 500 customers onto its SaaS platform, the company had something many competitors couldn’t credibly claim: a proven legacy-to-cloud migration methodology. From the start, it was run as a two-way street—TechnologyOne and the customer working the plan together, not tossing requirements over a wall and hoping for the best. Over time, that playbook became a competitive advantage. If you’re a government department or a university, you don’t choose an ERP vendor because the demo looks nice. You choose the one you believe can actually get you there.

By the time support for on‑premise customers ended on 1 October 2024, the direction of travel was clear. TechnologyOne had pivoted the business to SaaS and transitioned roughly two thirds of its on‑premise base onto the platform. The deadline added urgency, but it also forced clarity: the future was cloud, and everyone was coming along.

One thing TechnologyOne didn’t do—despite having “made it”—was take its foot off product investment. The company continued reinvesting around 20% of revenue into R&D. In FY2024, it invested $128 million in R&D, up 14% on the prior year. For a mature enterprise software business, that level of reinvestment is a statement: product leadership isn’t a phase. It’s the strategy.

Financially, the results matched the narrative. In FY2024, TechnologyOne’s total ARR reached $470.2 million, up 20%, and ARR made up about 90% of total revenue—meaning most of the year’s revenue was effectively “already there” when the year began. That level of recurring revenue doesn’t just make forecasting easier; it makes the whole company calmer. You can plan, hire, invest, and commit without living quarter to quarter.

FY2024 also marked the company’s 15th consecutive year of record profit, record revenues, and record SaaS fees. Profit before tax grew 18%, exceeding the profit growth guidance set in May 2024. The company recorded $118 million in profit, up 15% from the prior year, while keeping profit margins above 25%.

And TechnologyOne didn’t use that momentum to get cautious. At its first Investor Day in July 2024, the company raised its ambition again, setting a new long-term target: more than $1 billion in ARR by FY30. In plain terms, it was aiming to roughly double again over about five years—consistent with the compounding rhythm it had maintained before.

Underneath those numbers was a balance sheet built for optionality. Net assets grew to $379.3 million, with cash and investments of $278.7 million. Cash flow generation was $119.0 million for the year, essentially matching net profit after tax of $118.0 million. That 100%+ cash conversion is what high-quality enterprise software earnings look like: profitable, real, and self-funding.

Customer economics were just as telling. Churn sat at 1.3%, and average ARR per customer exceeded $300,000. Low churn plus high value per customer is the combination that turns a SaaS business into a compounding machine—because you’re not constantly refilling a leaky bucket. You’re building on a base that stays.

By September 2025, the market’s recognition caught up with the operating reality: TechnologyOne entered the ASX 50 for the first time, joining the ranks of Australia’s largest listed companies.

The latest expression of the company’s “make it simpler, make it safer” philosophy is what it calls SaaS+. TechnologyOne says it is the world’s first SaaS+ ERP company, bundling its mission-critical global SaaS ERP product and implementation into a single fee. The point is straightforward: remove the traditional ERP nightmare—complex, long, risky, expensive consulting implementations—and replace it with faster go-lives and value that arrives sooner. In a category famous for cost overruns and blown timelines, that packaging isn’t a pricing tweak. It’s a direct attack on the biggest reason customers fear ERP in the first place.

IX. The UK Gambit: Expansion Beyond ANZ

TechnologyOne’s dominance in Australia and New Zealand came from going deep in markets that are stable, regulated, and operationally complex. But even the best home market eventually has a ceiling. If TechnologyOne wanted the next leg of compounding, it needed a bigger playing field.

That’s why the UK matters.

TechnologyOne has estimated the total addressable market in the UK is roughly three times the size of APAC for its products. And strategically, the fit is almost uncanny: UK local government and higher education look a lot like TechnologyOne’s Australian strongholds—public sector organizations with real compliance burden, specialized workflows, and very little patience for generic software that needs years of customization to behave.

Still, the UK wasn’t a “plant a flag and win” story. TechnologyOne opened its first UK office in Maidenhead back in 2006, but meaningful traction took time. Enterprise software doesn’t reward impatience, especially when you’re asking institutions to bet their core systems on an overseas vendor.

Progress started to show in the numbers. In 2020, TechnologyOne’s UK operations broke even, reversing an A$1.9 million loss the year before. By then, UK ARR had reached A$7.5 million, up 22% year over year. Not huge by group standards—but big enough to prove the model could travel.

The customer wins were exactly where you’d expect: the verticals TechnologyOne knows best. North Wales Fire & Rescue Services. Warwick District Council. And in Northern Ireland, four of the eleven councils, including Mid Ulster District Council and Mid & East Antrim Borough Council. In enterprise software, those early reference customers are everything. They turn a cold, skeptical market into one where the next buyer can call someone who has lived through the implementation and come out the other side.

Then came a move that signaled TechnologyOne wasn’t just “testing” the UK anymore. In September 2021, it announced its first international acquisition: Cambridge-based Scientia, a higher education timetabling and resource scheduling software vendor, founded in 1989 by Shaji C.K. TechnologyOne acquired Scientia for £12 million (A$22.4 million).

TechnologyOne positioned the deal as a capability and credibility accelerator—buying not just product functionality, but relationships and presence that could take years to build organically. As the company put it at the time:

"This is our company's first international acquisition and it demonstrates our deep commitment to serving the higher education sector and the UK market. The unique IP and market-leading functionality of Scientia's product supports our vision of delivering enterprise software that is incredibly easy to use. We are excited about the opportunities this will bring to both our UK and Australian customers in the coming years."

The strategic logic was simple: Scientia gave TechnologyOne more surface area inside universities, creating faster cross-sell opportunities for its broader education suite. Over time, it also offered a potential bridge beyond the UK.

TechnologyOne kept pressing its advantage in education. In November 2024, it acquired curriculum management solution CourseLoop. With CourseLoop folded in, TechnologyOne said its OneEducation platform became the world’s first SaaS system spanning the entire student lifecycle—from course design through to graduation—inside a single unified ERP solution. In other words: deepen the vertical, make the suite harder to displace, and keep raising the bar on what “end-to-end” actually means.

The UK business began to accelerate, with TechnologyOne reporting a 50% increase in UK ARR—an encouraging sign that the long, patient setup phase was starting to convert into real momentum. But the competitive landscape is unforgiving. CEO Edward Chung has been clear-eyed about both sides of the bet: "We're confident the UK remains an exciting and large market for our products and will become a significant contributor of profit growth in future years." TechnologyOne is up against serious rivals, including Dutch-based Unit4, plus the global giants. The difference is that TechnologyOne has spent decades winning precisely this kind of fight: smaller player, tighter focus, better execution.

That’s what makes the UK gambit so pivotal. If it works, TechnologyOne effectively steps into a market that could triple its runway. If it doesn’t, it burns years of attention and capital that could have compounded elsewhere. The early signs are promising—but in the UK, as in all ERP, the story only counts when the implementations stick and the references keep stacking.

X. The Final Transition: Di Marco's Full Exit & Legacy (2022)

In February 2022, Adrian Di Marco announced he would step down as TechnologyOne’s executive chairman after 35 years with the company, effective 30 June. It wasn’t a dramatic breakup or a sudden resignation. It was the final handoff in a succession that had been years in the making—and it marked the end of an era for one of Australia’s most enduring founder-led technology stories.

Di Marco framed it exactly that way:

"Today's announcement is the final step of a carefully planned transition that started with the appointment of our long service COO, Edward Chung, to the role of CEO in 2017, the renewal of our board over the past five years and the recruitment of a very experienced deputy chair, Pat O'Sullivan."

And he didn’t pretend the road ahead would be smooth—only that the company had been built to handle it:

"There have been challenges over the years at TechnologyOne and there will be more ahead. I am confident that our DNA of adapting, changing and never giving in, will allow us to continue to be very successful under the strong leadership of our CEO, Edward Chung and his team."

Then he made sure the credit landed where he believed it belonged:

"In the end, TechnologyOne's success comes down to the amazing hardworking and passionate people that work at TechnologyOne, that I have had the honour to work with for so many years. To all of our people I say thank you."

The incoming chair, Pat O’Sullivan, brought deep corporate experience from PwC, Goodman Fielder, Optus, and Nine Entertainment, and also held board seats at SiteMinder and Carsales.com. His appointment signaled continuity in governance, but also a fresh set of eyes at the top of the board—exactly the kind of balance you want when a founder finally lets go.

By 2019, Di Marco’s 8.6 per cent stake in TechnologyOne was worth more than $240 million, and with other property investments his net worth was reportedly more than $300 million. Since the company’s value continued to rise after that, his remaining stake likely became more valuable as well.

What Di Marco did next is, in a way, the counterfactual version of his own origin story. Early on, he’d been rejected by Australian venture capital when he was trying to build TechnologyOne. After his exit, he leaned into the role he wished had existed back then: he became a supporter of venture capital and invested in more than 30 early-stage tech companies in Australia and overseas, pairing capital with the kind of hard-earned mentorship that only comes from shipping software and surviving decades of competition.

He also formalized TechnologyOne’s giving. The company established the TechnologyOne Foundation in 2015 to make charitable giving a long-term commitment and embed philanthropy into the culture. The Foundation set an ambitious goal: helping lift 500,000 children and their families out of poverty over 15 years. A 2019 donation was shared among eight organizations—Opportunity International Australia, The Salvation Army, The School of St Jude, SolarBuddy, The Fred Hollows Foundation, Princes Trust (UK), Smith Family and Big Issue—moving the Foundation closer to that target.

In 2025, Di Marco’s contributions were recognized nationally. He was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia in the 2025 Australia Day Honours for "service to information technology, and to the community".

If you ask Di Marco what the through-line was, he points to reinvention: four major technology paradigm shifts—relational databases, the PC, the internet, and then the cloud—and a willingness to rebuild rather than defend what worked yesterday.

The legacy is hard to overstate. TechnologyOne became Australia’s largest enterprise software company, built without the usual venture capital backing, thriving against global giants in one of the most unforgiving categories in tech. And maybe the bigger legacy is what it proved: you can build a world-class software company from Brisbane, not just Silicon Valley—if you’re willing to be patient, focused, and relentless.

XI. The Playbook: Business & Cultural Lessons

TechnologyOne’s four-decade run isn’t just a timeline of products and profits. It’s a case study in a handful of principles, applied with unusual discipline, for an unusually long time. The specifics matter, but the themes are surprisingly portable.

The "Power of One" Philosophy

“We do not use implementation partners or value added resellers. We take complete responsibility for building, marketing, selling, implementing and supporting our enterprise solution for each customer to guarantee long term success. The power of a single integrated enterprise solution, built on a single modern platform, with a consistent look and feel.”

That’s the core of TechnologyOne’s operating model: no hiding behind channel partners, no blaming a systems integrator when a rollout goes sideways, no “it’s not us, it’s them.” If you sell mission-critical ERP to councils, universities, and government agencies, the only real currency is trust. Owning the whole lifecycle is expensive and sometimes slower in the short term, but it buys something most vendors never fully earn: accountability that customers can actually feel.

And it removes the classic enterprise software fog. With the traditional model, when an implementation fails, you get a three-way argument: the vendor says it’s the integrator, the integrator says it’s the product, and the customer is stuck in the middle. TechnologyOne designed that ambiguity out of the system by owning everything end-to-end. Over time, that clarity compounds into customer satisfaction and retention that are extremely hard for competitors to replicate.

Configurable, Not Customizable

TechnologyOne’s original architectural bet still looks like one of its biggest advantages: build software that can be configured, not customized. One global codebase that every customer runs, with configuration on top, means upgrades can be rolled out broadly, support doesn’t explode into a thousand edge cases, and R&D investment lifts the entire customer base at once.

Today, that’s the SaaS playbook. In the late 1980s, it was a contrarian stance—especially in ERP, where “customize anything” was often how deals were won. But it set TechnologyOne up with foundations that were clean enough to evolve through multiple technology shifts, while competitors that grew up on customization often had to drag decades of complexity with them into the cloud era.

Vertical Depth Over Horizontal Breadth

Instead of trying to serve everyone the way global ERP vendors like Oracle and SAP do, TechnologyOne committed to a small set of vertical markets and went deep. That focus let the company deliver real “out of the box” depth—workflows, compliance, reporting, and operational realities that actually match how those organisations run.

Just as important as the choice of verticals was the discipline to stay inside them. Every enterprise sales team feels the temptation to chase adjacent opportunities. TechnologyOne’s leadership kept reinforcing the same message: focus isn’t a constraint, it’s a moat. The product gets better faster for the customers you actually serve, and the implementation muscle gets sharper in the environments you know best.

Long-Term Founder Leadership

When Adrian Di Marco stepped down as CEO in May 2017, he was one of the longest-serving chief executives of an ASX-listed company. That kind of longevity matters because it changes what a company is willing to attempt. A long-horizon leader can justify big, uncomfortable bets—like spending $150 million to rebuild for the cloud—because they expect to be around long enough to see the payoff.

But TechnologyOne also shows the healthier second half of the founder story: founder-led doesn’t have to mean founder-dependent. The transition to Ed Chung was planned, internal, and timed to preserve momentum. Di Marco stayed involved, but the operating centre of gravity moved. That’s rare, and it’s part of why the cloud era became a compounding chapter instead of a disruption chapter.

Strategic Patience in International Expansion

The UK expansion is a reminder that TechnologyOne doesn’t really do “blitz.” It built dominance in Australia and New Zealand first, then pushed internationally with measured expectations and a willingness to absorb losses while credibility and references accumulated. Even the acquisitions were consistent with the broader playbook: buy capabilities that deepen the vertical position and accelerate trust, not random growth for its own sake.

In a category like ERP, patience isn’t just a virtue. It’s a requirement. The winners aren’t the ones who arrive first with a press release; they’re the ones who stick long enough for the implementations to succeed, the renewals to roll in, and the customer references to become a flywheel.

XII. Investment Thesis: Bull & Bear Cases

The Bull Case

If you’re looking for the ingredients of a long-term compounder, TechnologyOne has a lot of them:

Market Position and Switching Costs: In several Australian verticals, TechnologyOne isn’t just a vendor, it’s infrastructure. And in ERP, “installed” is a powerful state to be in. Implementations take years, processes get rebuilt around the system, and whole teams learn new ways of working. That’s why customers rarely switch on a whim—and why retention north of 99% matters. It’s not a brag line; it’s evidence of real switching costs.

Recurring Revenue Model: With roughly 90% of revenue recurring and largely locked in at the start of the fiscal year, TechnologyOne runs with unusually high visibility. That predictability lowers risk, supports consistent reinvestment in R&D, and avoids the feast-or-famine dynamics that plague project-heavy software businesses.

Addressable Market Expansion: The UK is the clearest path to a bigger runway. TechnologyOne has estimated it’s about three times the size of APAC for its products. The early signs—ARR momentum and acquisitions that deepen the education footprint—suggest the company is past the “toe in the water” phase and is building real presence.

SaaS+ Differentiation: Bundling software and implementation into a single fee is a direct answer to ERP’s biggest fear factor: the messy, expensive, unpredictable rollout. If TechnologyOne can consistently deliver faster go-lives and better outcomes with SaaS+, it can turn implementation risk from a sales objection into a selling point.

Financial Strength: A strong balance sheet, steady profitability, and solid cash generation give TechnologyOne options. It can keep funding R&D, absorb the cost of international expansion, and pursue acquisitions without being forced to tap capital markets at the wrong time.

The Bear Case

There are also real reasons the story could disappoint:

Valuation: At around 60–70 times earnings, the market is paying for a lot of future success upfront. If growth slows—especially ARR growth—TechnologyOne could see meaningful multiple compression even if the business remains healthy.

Geographic Concentration: For all the UK ambition, the company still depends heavily on Australia and New Zealand. They’re stable markets, but not large ones, and they don’t offer the same long runway as the US or broader Europe.

Technology Disruption: AI and other emerging shifts could reshape enterprise software in ways that are hard to model. TechnologyOne has navigated major platform transitions before, but future disruptions could change buyer expectations, product architectures, and competitive dynamics faster than past cycles.

Competition: Oracle, SAP, Microsoft, and Workday have far deeper pockets and enormous customer bases. If any of them decide to press hard into TechnologyOne’s strongest verticals, that could pressure both growth and margins.

Key Person Risk: The founder-to-operator transition worked. But the company’s culture and long-term strategy are still closely tied to a small senior leadership group. Unexpected departures could create uncertainty, internally and in the market.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Supplier Power: Low. TechnologyOne controls its stack and engineered database independence to avoid being trapped by a major vendor.

Buyer Power: Moderate. No single customer dominates the revenue base, but government and institutional procurement can be formal, competitive, and slow-moving.

Threat of New Entrants: Low to moderate. ERP takes years of product investment, implementation credibility, and reference customers. TechnologyOne’s vertical depth raises the bar for newcomers.

Threat of Substitutes: Moderate. Best-of-breed point solutions can peel off parts of the ERP value proposition, even if they don’t replace it entirely. TechnologyOne’s counter is integration and the switching costs that come with it.

Competitive Rivalry: Moderate. The giants have scale; TechnologyOne has focus. The fight is less about who has more resources and more about who fits the customer better—and who can deliver reliably.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Moderate. Multi-tenant SaaS creates real operating leverage, and R&D spend can benefit the entire customer base.

Network Effects: Limited. ERP generally doesn’t get meaningfully better because other customers use it.

Counter-Positioning: Strong. The Power of One model—owning implementation and support—would be difficult for many competitors to copy without blowing up their partner ecosystems.

Switching Costs: Very strong. Once ERP is embedded, replacing it is painful, risky, and expensive.

Branding: Moderate. Strong brand recognition in its target verticals, with less visibility outside them.

Cornered Resource: Limited. No exclusive access to scarce inputs, but it does have accumulated domain expertise.

Process Power: Moderate. Migration, implementation, and delivery methodology—built over hundreds of transitions—can become a hard-to-replicate advantage.

Key Performance Indicators

For anyone tracking TechnologyOne from here, three KPIs are especially telling:

-

Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR) Growth: ARR is the heartbeat. The company’s $1B+ ARR target by FY30 implies sustained mid-teens annual growth. If ARR growth materially slows, that’s the clearest early warning sign.

-

UK ARR Growth Rate: The UK is the primary growth lever outside mature ANZ markets. Recent growth (reported as running above 50%) is encouraging, but what matters is whether that pace holds as the base gets larger.

-

Net Revenue Retention: TechnologyOne doesn’t disclose NRR directly, but you can infer directionally through retention, ARR per customer, and customer expansion. Net retention above 100% is what turns a stable installed base into an internal growth engine.

Regulatory and Legal Considerations

TechnologyOne carries the usual exposure that comes with selling into government and public-sector institutions: compliance requirements, procurement rules, and shifting regulatory standards. Its IRAP assessment for PROTECTED-level data shows the capability to meet high bars, but maintaining that posture requires ongoing investment.

There are also people and culture risks that investors tend to overlook until they’re forced to care. In 2020, a bullying case resulted in the Federal Court ordering TechnologyOne to pay $5.2 million to a former employee. The company denied the allegations and appealed. The key question isn’t just the outcome of a single case; it’s whether any broader pattern emerges over time.

XIII. What Investors Are Missing: Myth vs. Reality

For all of TechnologyOne’s consistency, the market still carries a handful of lazy assumptions about what this company is—and isn’t. It’s worth clearing those up, because the gap between perception and reality is where both opportunity and risk tend to hide.

Myth: TechnologyOne is too small to compete with global giants

Reality: TechnologyOne is not trying to out-muscle Oracle or SAP across every industry on earth. That’s the wrong frame. In its chosen verticals, focus beats scale. When you’ve built deep, preconfigured solutions for councils, universities, and government agencies—and you control the full implementation and support experience—you don’t need to be the biggest vendor in the world. You need to be the best fit, with the lowest delivery risk.

The company’s penetration of ANZ local government is the proof point: vertical specialization can defeat horizontal scale. The real question isn’t whether TechnologyOne can win “ERP” everywhere. It can’t, and it shouldn’t try. The question is whether it can take the same playbook—vertical depth plus end-to-end accountability—and replicate it in markets that look structurally similar, especially internationally.

Myth: The Australian market is saturated

Reality: TechnologyOne is heavily penetrated in parts of its core, but that doesn’t mean the growth engine shuts off. In ERP, growth doesn’t only come from new logos. It comes from expanding the footprint inside customers, winning the remaining competitive deals that still exist in the verticals, and pushing further into larger and more complex agencies—especially at state and federal levels.

The SaaS shift also creates its own tailwind. Moving customers off legacy on-premise setups and onto the modern SaaS platform isn’t just a technical migration; it’s often when customers adopt more modules, modernize processes, and standardize on more of the suite.

Myth: Premium valuation reflects growth that can’t continue

Reality: TechnologyOne isn’t cheap. But the reason it trades at a premium isn’t mysterious: highly recurring revenue, unusually strong retention, consistent profitability through a brutal industry transition, and strong cash conversion. Those are exactly the traits public markets tend to reward with higher multiples.

The real debate isn’t whether the business is high quality—it is. The debate is whether the growth rate that investors are paying for is sustainable, particularly as the company leans harder into international expansion. The multiple ultimately lives or dies on that question.

Myth: The founder departure creates uncertainty

Reality: Most founder transitions introduce chaos because the business was built around one person. TechnologyOne did the rare thing: it treated succession as a multi-year project, not an event. Adrian Di Marco handed the CEO role to Ed Chung in 2017, stayed involved in a supporting role, and then fully stepped away from the chair later.

Chung has now led the company for eight years. Over that period, the cloud transition moved from bet to baseline, and growth continued. That doesn’t remove all key-person risk—no company ever does—but it’s hard to argue the business is rudderless without the founder. The cultural DNA appears intact, and the governance structure is mature enough to outlast any one individual.

Myth: Technology risk is high

Reality: Any enterprise software company carries technology risk. What matters is whether it has proven it can evolve without breaking customers—or breaking the business. TechnologyOne has already navigated four major platform shifts: relational databases, client-server, the web, and the cloud. That’s a real track record of organizational adaptation.

Of course, past success doesn’t guarantee future performance. But it does suggest this isn’t a company that freezes when the ground shifts.

Conclusion

TechnologyOne’s arc—from a demountable office in a hide factory car park to an ASX 50 company—is one of the quiet great stories in Australian business. It’s proof that you can build world-class enterprise software far from the usual tech capitals, without the typical venture-capital rocket fuel, if you have patient backing and the nerve to think in decades instead of quarters.

The ingredients of that success are easy to list but hard to execute for 40 years: go deep in a handful of verticals instead of spreading thin, keep one global codebase that customers configure rather than customize, and live the Power of One idea—own development, sales, implementation, and support so there’s nowhere to hide when outcomes matter. Plenty of companies have tried to copy parts of this. Far fewer have shown the discipline to keep saying “no” to tempting detours, or the willingness to own the full customer experience end to end.

For investors, that creates the classic quality-at-a-price question. Exceptional businesses usually trade at exceptional valuations. TechnologyOne’s record—steady execution, extremely high retention, and repeated successful technology transitions—earns confidence. But in software, confidence is not certainty.

The UK will likely decide what TechnologyOne becomes from here: a dominant ANZ champion, or a global vertical software leader. The early signs have been encouraging—momentum in recurring revenue, smart acquisitions, and growing customer wins—but the UK is fiercely competitive, and enterprise credibility is earned slowly.

Adrian Di Marco’s legacy is bigger than shareholder returns. He showed that Australia could produce world-class ERP, then turned around and helped fund and mentor the next generation of founders. His Medal of the Order of Australia in 2025 recognized exactly that: service to information technology, and to the community.

And the story isn’t finished. TechnologyOne’s goal of more than $1 billion in ARR by FY30, its push in the UK, and product initiatives like SaaS+ all point in the same direction: keep simplifying what customers fear most about ERP, and keep compounding. If you’re drawn to disciplined execution, vertical focus, and businesses that get stronger as they scale, TechnologyOne is still one of the most compelling stories in Australian business.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music