Telstra Group Ltd: Australia's Telecom Titan – From Government Monopoly to Digital Disruptor

I. Introduction: The Company That Connected a Continent

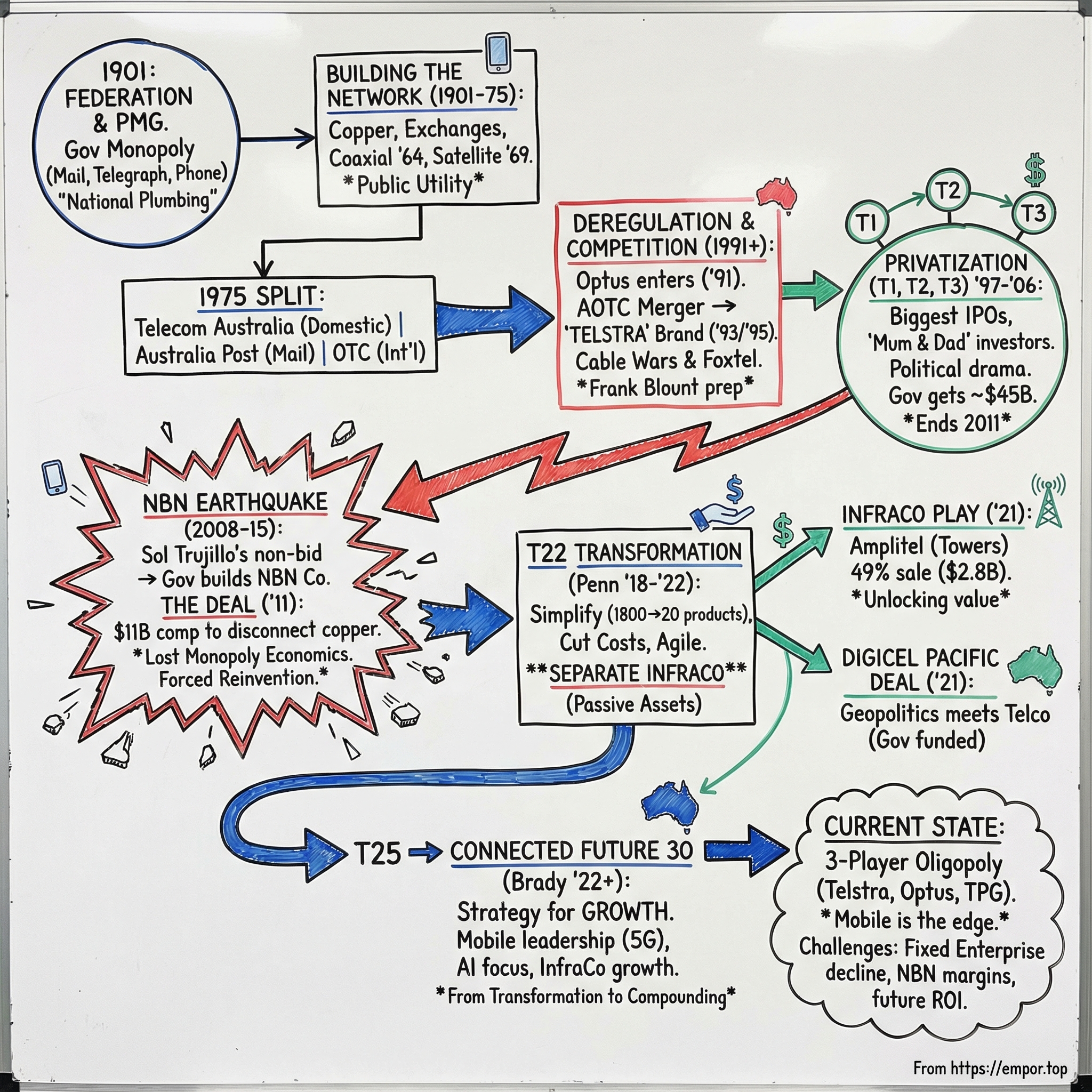

Picture Australia in 1901: a brand-new federation stitched together from six former colonies, spread across a landmass the size of the contiguous United States. Fewer than four million people lived there, clustered in coastal cities and scattered across enormous distances inland. If you’re trying to turn that into one country, you don’t start with slogans. You start with wires.

That same year, the Commonwealth created the Postmaster-General’s Department. Alongside what would become Australia Post, it was responsible for the essentials of national connection: mail, telegraph, and the early telephone network. It didn’t look like the beginning of a corporate giant. It looked like a public utility doing the unglamorous work of nation-building.

Over the next century, that utility would evolve into Telstra Group Limited: Australia’s largest telecommunications company by market share, a builder and operator of the networks the country runs on, and a mainstay of the S&P/ASX 20.

Today, the scale is hard to miss. In FY 2024, Telstra generated AU$23.5 billion in revenue, up 3.4% year over year. It served about 26 million retail mobile services, employed roughly 26,000 people, and had more than 11 billion shares outstanding on the ASX. With more than one million shareholders, it’s also the most widely held listed company in Australia.

But Telstra’s story isn’t remarkable because it got big. It’s remarkable because it kept surviving events that should have broken it.

This is a company that went from total state ownership to full privatization—three separate sell-downs, each wrapped in politics and controversy. It endured deregulation designed to erode its dominance. And then came the National Broadband Network: a government policy decision that didn’t just introduce competition, but fundamentally rewired Telstra’s economics by dismantling the most lucrative part of its traditional fixed-line world.

And yet, Telstra adapted. It rebuilt its operating model, simplified its product mess, separated infrastructure assets, and doubled down on the one advantage it could still own: network leadership.

That’s how Telstra ended up with the country’s strongest position in mobile. In 2023, Australia’s three major mobile operators were Telstra, Optus, and TPG Telecom, with subscription shares of 56.5%, 23.9%, and 13.1% respectively. That lead wasn’t an accident. It was earned over a century of infrastructure decisions, competitive battles, privatization drama, and reinvention.

What follows is the story of how a dusty government postal department became one of the most valuable companies in the Asia-Pacific region—and how it kept rewriting itself through privatization, the NBN earthquake, and transformations like T22, all the way to today’s next chapter under CEO Vicki Brady.

II. Origins: Building a Nation's Nervous System (1901–1975)

When Edmund Barton became Australia’s first Prime Minister on New Year’s Day 1901, one of his biggest problems wasn’t ideological. It was logistical: how do you run a country the size of a continent when your lines of communication are a patchwork of colonial systems?

Before federation, each colony ran its own telecommunications—its own telegraph network, its own rules, its own standards. After federation, those fragmented networks were pulled into a single new Commonwealth department: the Postmaster-General’s Department, formed in 1901. The PMG didn’t just deliver mail. It controlled the nation’s communications stack—post, telegraph, and the early telephone system—under one roof.

And it was built to be a monopoly, on purpose.

Australia didn’t take a “let private capital build it and the government regulate it” approach. Telecommunications were treated as public infrastructure. The PMG was funded by public revenue, had no shareholders, and didn’t pretend it was optimizing for profit. The priority was universal access: if you were trying to stitch together a sparsely populated country with vast distances, connectivity wasn’t a luxury product. It was national plumbing.

The rollout came fast by early-1900s standards. The first telephone exchange opened in Melbourne in 1902. By 1907, engineers had connected Sydney and Melbourne by phone line, making it possible for the two rival cities to speak directly—an early, symbolic win for a new federation trying to act like one nation.

From there, the network spread outward, mile by mile, decade by decade. Copper lines, exchanges, switching equipment—unsexy, capital-heavy work, quietly extending across the continent. Big technology leaps arrived in the post-war era. Coaxial cables in 1964 allowed thousands of calls and television transmissions to move at once. Then, in 1969, satellite broadcasting entered the mix, and Australia found itself part of a global moment: the moon landing. Australian viewers watched Neil Armstrong’s first steps with help from facilities like the Parkes radio telescope, which became a point of national pride and a reminder that communications infrastructure could place Australia on the world stage.

But by the 1970s, the PMG’s all-in-one structure was starting to strain. Postal delivery and telecommunications were becoming fundamentally different businesses—different technologies, different investment cycles, different management needs. So on 1 July 1975, the government split it.

Postal services moved to the Australian Postal Commission, later branded Australia Post. Domestic telecommunications moved to a new entity: the Australian Telecommunications Commission, trading as Telecom Australia.

This wasn’t privatization, not even close. Telecom Australia was still wholly owned by the Commonwealth. But it was the first real structural break from the old “one department runs everything” model. It also clarified a second division that had already existed for decades: international telecommunications sat with the Overseas Telecommunications Commission, created in 1946 to manage Australia’s links to the rest of the world. Domestic and international communications would remain separate bureaucratic worlds until 1992.

That early history matters because it explains what Telstra eventually became—and what it started with. The vast network of copper, exchanges, and infrastructure that later defined the company wasn’t built by private investors taking entrepreneurial risk. It was built by public expenditure over generations, creating exactly the kind of “natural monopoly” that is extremely difficult for competitors to replicate once it’s in place.

III. The Competition Arrives: Deregulation & The Optus Challenge (1991–1997)

By 1990, Australia was in the middle of a microeconomic reform wave under the Hawke-Keating Labor government. Banking was being deregulated. Trade barriers were coming down. Big, protected incumbents across the economy were being told to sharpen up.

Telecommunications was next.

But here’s the thing: you can’t really privatize a monopoly and call it a market. Before Telstra could be sold to the public, it first had to learn how to compete.

So in 1991, the government cracked the door open and issued a second carrier licence to Optus. This wasn’t a scrappy startup. Optus arrived as a heavyweight consortium backed by major global telecom players like Bell South and Cable & Wireless, plus Mayne Nickless and institutional investors. For the first time since federation, the national carrier had a real rival with capital, ambition, and permission to build.

Then came the internal reshuffle that set up the modern Telstra. Until this point, domestic telecoms and international telecoms lived in different bureaucratic worlds: Telecom Australia at home, the Overseas Telecommunications Commission abroad. On 1 February 1992, they were merged into a single organisation: the Australian and Overseas Telecommunications Corporation, or AOTC.

The logic was obvious. Customers didn’t think in terms of “domestic” versus “international.” They just wanted their calls to work.

But AOTC was a name only a government could love. And “Telecom Australia” suddenly sounded bland and indistinct—especially in a world where competition was arriving and privatization was already being whispered about. The answer was a new brand: Telstra. It appeared first for international business in 1993, then became the domestic trading name on 1 July 1995—short, modern, and unmistakably Australian.

To lead this transition, the company made a surprising choice: Frank Blount, a former AT&T executive. Blount brought an outsider’s mindset to what had long been a very Australian, very public-sector institution. He understood that preparing for a competitive, privatized future wasn’t about a rebrand alone. It meant changing how the company operated—its culture, its cost base, and the way it thought about growth.

Meanwhile, Optus went straight for the jugular. In 1992 it pushed into mobile, attacking Telstra where consumers actually felt the service. Then, in 1994, it expanded the fight again by building its own cable television network.

Telstra’s response was fast and expensive. It accelerated its own high-bandwidth cable build and teamed up with Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation to create Foxtel—a pay-TV joint venture that would become a staple in Australian households for years.

But the cable war also taught a brutal lesson: infrastructure competition can be economically irrational. Telstra and Optus laid overlapping networks through the same suburbs, duplicating massive fixed costs just to win market share. It was capital-intensive, messy, and ultimately a preview of the argument that would later power the National Broadband Network: maybe some parts of telecom infrastructure shouldn’t be duplicated at all.

Blount also looked beyond Australia. With a relatively small population and a limited domestic ceiling, he pushed for expansion into Asia, building on existing positions in places like Hong Kong, Thailand, and the Philippines. That international ambition would become a recurring Telstra debate in the decades that followed: should the company become a regional telecom player, or double down on defending—and monetizing—its home-market dominance?

By 1995, Telstra had its name, its rival, and a clearer corporate structure. The monopoly era was over. And the groundwork was being laid for the next seismic shift: selling the company to the public in what would become Australia’s largest IPO.

IV. The Great Privatization: T1, T2, T3 & The Political Drama (1997–2011)

If deregulation ended Telstra’s monopoly in theory, privatization ended it in spirit. And in Australia, selling the national carrier wasn’t just a financial decision. It became one of the defining political fights of the Howard era, dragged out over almost fifteen years and argued on everything from rural service quality to national security to whether core infrastructure should ever leave government hands.

The sell-down came in three big acts, all initiated by the Howard government. First came “T1” in 1997, priced at $3.30 a share. Then “T2” in 1999 at $7.40 for retail investors (and $7.80 for institutions). And finally “T3” in 2006, priced around the mid-$3 range. In that first T1 float, the government sold roughly one third of Telstra for $14 billion and listed it on the Australian Securities Exchange.

T1 was the largest IPO Australia had ever seen, and the government treated it like a national event. The marketing blitz wasn’t an accident: the goal was to create a vast base of “mum and dad” shareholders—millions of voters who would now have a direct stake in Telstra’s fortunes, and in the broader logic of market reform. More than two million Australians bought T1 shares. Overnight, Telstra wasn’t just a utility. It was in everyone’s portfolio.

The timing couldn’t have been better. The late-1990s tech boom was lifting telecom valuations around the world, and Telstra rode that wave. Instalment receipts, issued at $1.95, climbed quickly through late 1997 and early 1998. The fully paid T1 shares soared too, topping $9 by early 1999. For early investors, it felt like a rare thing in public policy: a win that paid out immediately.

T2 landed right at the top of that frenzy. In October 1999, the government sold the second tranche at $7.80 per share to institutions and $7.40 to retail. The problem with selling at the peak is that it turns a lot of buyers into long-term bagholders. When the dotcom bubble burst and the sector’s mood turned, those investors who came in near $8 were in for a punishing decade as technology stocks fell and telecom economics began shifting under Telstra’s feet.

Then came the hardest part: getting T3 through at all.

The years between T2 and T3 were politically poisonous, especially inside the Coalition. The National Party—guardian of rural and regional electorates—had deep skepticism about privatizing the company that kept the bush connected. In communities where coverage was already patchy and service reliability was a constant complaint, the fear was straightforward: a privatized Telstra, judged by shareholders and margins, would logically invest less where returns were lowest.

But in the end, the government pushed it through. In November 2006, it sold the third tranche—more than 4.2 billion shares—at around $3.70 per share. Across T1, T2, and T3, the privatization generated roughly A$45 billion for the government.

Even then, it wasn’t fully over. The remaining 17% stake was transferred to Australia’s Future Fund, created to help meet future superannuation liabilities for federal public servants. In 2009, the Future Fund sold about $2.4 billion worth of shares, taking the government’s stake down to 10.9%. And in August 2011, under the Gillard Labor government, the Future Fund sold its remaining “above market weight” Telstra holding, effectively closing the book on privatization.

The sale delivered a huge windfall to Canberra. But it also left behind a structural problem that would haunt telecom policy for years: Telstra still controlled the critical fixed-line infrastructure—especially the copper local loop into homes—while also competing at retail on top of that same infrastructure. That vertically integrated setup became the central regulatory headache of the era, and it would eventually become the political rationale for the most disruptive intervention of all: the National Broadband Network.

V. The NBN Earthquake: The Deal That Changed Everything (2008–2015)

If there’s a single policy decision that reshaped Telstra’s modern existence, it’s the National Broadband Network. And the flashpoint came on 26 November 2008, when Telstra responded to the Rudd government’s NBN Request for Proposals with something that barely qualified as a bid.

Instead of submitting a full, compliant tender, Telstra sent a 12-page letter proposing a $5 billion broadband network focused on major cities and covering roughly 80 to 90 percent of Australians—well short of the 98 percent coverage the tender required. The government’s response was swift. On 15 December 2008, Telstra was removed from the NBN RFP process.

Under CEO Sol Trujillo, Telstra had been in a long, bruising regulatory fight with successive governments. From Telstra’s perspective, the NBN tender was asking it to spend heavily and then accept rules that would cap returns and erode shareholder value. So Telstra didn’t just push back. It effectively forced the issue: if the government wanted this network on those terms, it could build it itself.

Telstra’s exclusion triggered the biggest one-day percentage fall in its share price in the company’s history.

And the government did, in fact, build it itself. It set up NBN Co, a government-owned, wholesale-only network designed to replace large parts of Telstra’s fixed-line dominance. The intent wasn’t subtle. Over time, Telstra would be required to migrate customers off its copper and cable broadband networks. The most lucrative piece of the old Telstra—the monopoly “last mile” copper network into homes—was being removed as a source of long-term advantage.

What followed was one of the most complex commercial negotiations in Australian corporate history: Telstra, NBN Co, and the government trying to unwind a century of incumbent infrastructure and rebuild the industry around a structurally separated wholesale network.

After years of hostility, they landed a landmark deal. On 23 June 2011, NBN Co signed definitive agreements with Telstra, estimated to be worth about A$9 billion post-tax net present value, building on a financial heads of agreement reached roughly a year earlier. The headline number attached to the arrangement was about $11 billion: payments in exchange for Telstra migrating its broadband customers, granting access to key passive infrastructure like pits, ducts, and backhaul fibre, and stepping away as a fixed-line wholesale competitor.

In practical terms, the 2011 agreements meant Telstra would progressively disconnect customers from its copper and HFC networks in areas as NBN fibre was installed, and it would lease infrastructure—exchange space, ducts, and dark fibre—to the new national network operator. Telstra would be compensated, but its fixed-line economics would never look the same again.

Then politics shifted again. After the Abbott Coalition government came to power in 2013 and moved the NBN toward a “multi-technology mix” that kept more copper in play, the deals were renegotiated. Telstra agreed to hand over ownership of its copper and hybrid fibre-coaxial networks while remaining committed to structural separation, under revised definitive agreements that retained the overall $11 billion value of the original arrangement.

The strategic consequence was brutal: Telstra’s fixed-line wholesale earnings were hollowed out. By 2017, Telstra was publicly confronting the financial reality of the NBN era—revenue and profit pressure, and dividend cuts that hit the share price hard. In broadband, Telstra ended up reselling NBN services in a fiercely competitive market where it effectively made zero margin.

That’s the NBN earthquake in one sentence: Telstra received compensation, but it lost the monopoly economics that had underwritten the old company.

And that forced the next chapter. Because once your biggest profit pool is being drained by design, you either reinvent the business—or you slowly become irrelevant.

VI. The Sol Trujillo Era & Network Leadership (2005–2009)

Telstra went looking for a CEO who could do two things at once: finish the march toward full privatization, and harden the company for a world where Optus and others were now credible threats. The board’s pick surprised a lot of people: Solomon Trujillo, an American telecom veteran who had led US West and worked at Orange in France.

He started on 1 July 2005, walking into what The Economist called “Australia’s toughest corporate job.” Telstra was no longer a protected arm of the state, but it still behaved like one—bureaucratic, slow, and not always built for speed. The share price had lagged, and competitors were chipping away at the fixed-line business just as mobile and broadband were becoming the center of gravity.

Trujillo’s answer was to spend money and move fast. Soon after arriving, he laid out a five-year turnaround plan meant to make Telstra more responsive to shareholders and less tangled internally—streamlining systems, cutting staff, and, most importantly, upgrading aging networks.

The flagship move was mobile. Telstra would phase out its CDMA network and replace it with a nationwide 3G network in the 850 MHz band—what Telstra branded “Next G.” Built from late 2005 through September 2006 and launched in October 2006, Next G became Trujillo’s defining accomplishment. At the time, it was positioned as the largest and fastest network of its kind in the world. It dramatically increased Telstra’s capacity for data traffic and gave the company a clear, defensible advantage customers could actually feel.

That network leadership wasn’t just marketing. Reports at the time cited peak download speeds above 14 megabits per second—multiples faster than what many users experienced on U.S. 3G networks. Next G helped push up mobile economics too, with average revenue per user rising and data revenue surging as Australians started using mobile internet at scale. After three years in the role, Trujillo was named “CEO of the Year” by Australian Telecom Magazine.

But Trujillo didn’t just fight competitors. He fought Canberra.

He developed a reputation as intensely combative with regulators and politicians, regularly clashing in public as telecom policy turned into a national obsession. That posture mattered, because it shaped how Telstra approached the early NBN era. The defiant, non-complying 12-page “bid” Telstra submitted in 2008 didn’t come from a CEO looking to meet government halfway. It came from a CEO who believed Telstra’s job was to protect shareholder value first—and dare the government to do the rest.

When Trujillo stepped down in 2009, he left behind a company that was leaner, more modern in mobile, and clearly capable of out-executing rivals on network performance. He also left behind scorched-earth relationships with policymakers—exactly the relationships Telstra would need as the NBN moved from concept to reality. Cleaning that up became a major part of the job for his successor, David Thodey.

The Trujillo era, in other words, delivered Telstra its most durable advantage for the next two decades—mobile network leadership—while setting the stage for some of its most painful political and regulatory battles.

VII. T22: The Strategy of Necessity (2018–2022)

When Andrew Penn became CEO in May 2015, he walked into a company that was running out of room to hide. The NBN was steadily draining the economics of Telstra’s fixed-line business. Customer experience was underwhelming. And a series of network outages had done the unthinkable: they put cracks in Telstra’s most trusted claim—network leadership.

Penn later described the moment with unusual candour:

When I first became CEO in 2015, we developed a vision to become a world-class technology company that empowers people to connect. And I still believe in that vision, but it did not land well in the market, not because people didn't understand it, but because we were so far from being there that I just don't think it was seen as plausible or realistic. Then, in early 2016, we had a couple of serious network outages. That was a real wake-up call because one of our greatest value propositions, network leadership, was shaken to the core.

The response was T22: a four-year transformation program announced in June 2018 that wasn’t framed as an ambitious reinvention so much as a necessity. Telstra’s old model had been broken by policy, competition, and complexity. T22 was the plan to build a new one—fast.

Penn and his team boiled it down to three big moves: simplify the business so digitisation could actually work, shift the organisation toward agile ways of working, and restructure the company by separating out physical infrastructure assets.

The simplification effort was almost absurd in scale. Telstra looked at its consumer and small-business catalogue and found 1,800 different products and plans. That wasn’t variety; it was operational debt. Under T22, those 1,800 offerings were cut back to 20 core plans. It was a ruthless reduction in complexity, and it cleared the path for something Telstra had struggled with for years: replacing legacy IT with modern digital platforms.

That kind of change doesn’t come free. The human cost was real. McKinsey, brought in during 2018, helped design a sweeping organisational restructure aimed at delivering $2.5 billion in core fixed-cost savings by 2022. That included around 8,000 job cuts—close to a quarter of the workforce at the time.

At the same time, Telstra reshaped what “workforce” even meant inside the company. Over the life of T22, Telstra reduced its direct and indirect workforce by more than a third, while hiring into the areas it believed would define the next era—software engineering, data analytics, cyber security, and artificial intelligence—adding more than 1,500 people in those fields.

T22 also pushed Telstra toward a structure that could better monetise what it still undeniably owned: infrastructure. Telstra InfraCo was established as a separate business unit, built around roughly $11 billion of passive assets—things like data centres, fibre, exchanges, ducts, and pipes.

By the end of the program in mid-2022, Telstra said it had returned to underlying growth, materially improved customer experience, cut costs by more than $2.5 billion, and shifted the way the company operated—with more than 17,000 people working in agile teams across the business.

And with that foundation laid, Penn signalled a change in posture. “If T22 was a strategy of necessity, T25 is a strategy for growth,” he said. “Today's announcement of T25 marks our transition from transformation to growth, from a strategy we had to do, to a strategy we want to do to focus on growth.”

He handed over to his successor having done the hard part: making Telstra smaller, simpler, and more digitally capable. The next chapter would test something different—whether Telstra could turn that overhaul into durable growth, not just survival.

VIII. The Infrastructure Play: InfraCo, Amplitel & Corporate Restructure (2021–2023)

One of T22’s most consequential outcomes was a simple realization: Telstra wasn’t just a telco. It was also an infrastructure owner on a national scale. Towers, ducts, fibre, exchanges, data centres—assets that looked less like a retail communications business and more like the kind of long-life, essential infrastructure that super funds love.

So Telstra started treating that infrastructure like its own business.

In 2021, it carved out its towers into a dedicated unit and sold a 49 per cent non-controlling stake for $2.8 billion. The buyers were a consortium including the Future Fund, Commonwealth Superannuation Corporation and Sunsuper, managed by Morrison & Co. The deal, announced on 30 June 2021, valued the towers business—then called Telstra InfraCo Towers—at $5.9 billion, a valuation multiple that looked far richer than what investors typically assign to a traditional telecom operator.

That was the point.

The towers transaction did three things at once. First, it put a clear price tag on assets that had been buried inside Telstra’s broader conglomerate valuation. Second, it proved there was deep institutional demand—especially from long-term capital like pension funds—for predictable, essential telecom infrastructure. And third, it gave Telstra real financial flexibility: cash that could go back to shareholders and toward reducing debt.

The new towers vehicle was branded Amplitel. With more than 8,000 tower, mast, pole, and antenna-mount structures—around 8,200 tower assets in total, including over 5,500 mobile towers—it became the largest mobile tower infrastructure provider in Australia. Telstra kept majority control, retaining 51 per cent ownership, while still holding what mattered most strategically: the active network, including the radio access network and spectrum. In other words, Telstra could unlock value from the steel in the ground without handing over the levers of mobile performance.

When Telstra announced the transaction, it also said it planned to return about half of the net proceeds—up to $1.35 billion—to shareholders in FY22 via an on-market share buy-back, with the remainder used to reduce debt.

This wasn’t just a towers deal. It was also a corporate reshuffle that made Telstra easier to understand. The company moved to a holding company structure with four main operating entities: Telstra Limited (the retail business and active network operations), Telstra InfraCo Fixed (passive fixed infrastructure, excluding towers), Amplitel (towers), and Telstra International (including the Digicel Pacific operations).

But there was an immediate follow-up question from investors: if towers can be partially monetised at a premium, what about InfraCo Fixed—the unit holding an even bigger set of infrastructure assets?

For the moment, Telstra said no. After reviewing the options, it concluded the best path for shareholders was to keep InfraCo Fixed in the current ownership structure, at least for the medium term.

Management argued the demand signals were strong: growing interest in fixed infrastructure, including from hyperscalers, and a long-term trajectory shaped by cloud migration and rapid AI adoption—trends that drive new requirements for data centres, edge computing, domestic fibre, and undersea cable.

The bigger takeaway is optionality. By separating infrastructure into cleaner buckets, Telstra made future choices easier. If the right moment comes, InfraCo Fixed could be monetised. If not, it can stay inside the group and still be run like an infrastructure business—supporting Telstra’s competitive position while making the company’s value and strategic options far more visible than they were before.

IX. The Digicel Pacific Acquisition: Geopolitics Meets Telecommunications

In late 2021, Telstra announced a deal that didn’t fit the usual telco playbook. This wasn’t about squeezing a few more points of margin out of a mature market. It was about geopolitics—specifically, the new great-power competition playing out across the Pacific.

The target was Digicel Pacific. The price: US$1.6 billion (about A$2.4 billion). But the real headline was who paid.

Telstra put in US$270 million of equity. The Australian Government—through Export Finance Australia—provided the remaining US$1.33 billion, using low-cost financing and “equity-like” instruments. And despite funding only a small slice of the purchase price, Telstra ended up owning 100% of Digicel Pacific.

That structure was as unusual as it sounds: the government took the bulk of the financial exposure while Telstra took operational control.

Why would Canberra do that? Because the strategic risk wasn’t hypothetical. Reports earlier that year of interest from China Mobile in acquiring Digicel Pacific sharpened concerns in Australia about who might control critical communications infrastructure in the region. Australia has long viewed Pacific Island nations as close partners with shared interests. But in recent years, several governments in the region have been broadening their options—moving from an “aid-donor” relationship with Australia toward deeper economic development ties with China.

Digicel Pacific matters because it is the connective tissue for much of the region. It held more than a 60% market share across the Pacific Islands and was the number one telco in Papua New Guinea, Nauru, Samoa, Tonga, and Vanuatu, and number two in Fiji. It had about 1,700 employees and roughly 2.5 million subscribers, spanning retail customers through to large enterprises. Financially, it generated EBITDA of US$233 million for the year ended 31 March 2021, with an EBITDA margin of 54%.

And its importance wasn’t just Telstra’s view. In a joint media release at the G20 summit in November 2022, the leaders of Japan, the United States, and Australia explicitly recognized the importance of reliable, high-quality communications networks—an unusually direct statement of how central telecom infrastructure has become to national strategy.

For Telstra, the deal offered modest earnings upside with limited capital at risk, because the government bore most of the funding burden. But the bigger benefit may have been relational: it bound Telstra and Canberra together in a high-trust, strategically sensitive transaction—exactly the kind of cooperation that can echo in future regulatory and policy negotiations.

For Australia, the logic was simple: keeping Pacific telecommunications infrastructure out of Chinese hands was worth US$1.33 billion in support. The Digicel acquisition looked like a new template for government-backed private ownership of strategic infrastructure—one that could become more common as geopolitical competition keeps spilling into corporate dealmaking.

X. T25 and Connected Future 30: The Strategy for Growth

When Vicki Brady took over as CEO on 1 September 2022, Telstra made history: for the first time in its 121-year story, the top job went to a woman.

Brady had arrived at Telstra in 2016, and she hadn’t come up through a single, straight-line telecom track. She’d moved across finance, strategy, sales, marketing, product, and customer-facing roles—experience that mattered in a company trying to become simpler on the inside and sharper on the outside. Before the CEO role, she served as Chief Financial Officer and Strategy & Finance Group Executive. As Brady put it herself: “My pathway to becoming CEO wasn't linear. It was shaped by a series of diverse roles across finance, strategy, sales, marketing, product and customer facing functions. I made two pivotal decisions in my career.”

Brady inherited T25 from Andrew Penn: the “growth” phase after the T22 clean-up. The goal was straightforward but ambitious—take the transformed platform and make it compound. T25 targeted mid-single-digit underlying EBITDA growth and high-teens underlying EPS compound annual growth from FY21 to FY25, alongside $500 million in net cost reductions and 5G coverage expanded to 95% of the Australian population.

Then, in May 2025, Brady laid out what comes next: Connected Future 30.

“Today, we announced our strategy for the next five years – Connected Future 30 – which will see us double down on connectivity and radically innovate in the core of our business. Demand for data and connectivity keeps growing, and technology change means the world will look very different by 2030.”

Connected Future 30 kept the ambition focused on the core, but widened the lens. Telstra set targets of mid-single-digit compound annual growth in cash earnings through to FY30, alongside a sustainable and growing dividend. It also set a goal of lifting underlying return on invested capital to 10% by FY30, up from 8%.

A big part of the story was AI—not as a buzzword, but as an operating model upgrade. Connected Future 30 targeted Telstra being in the top quartile of global enterprises for AI maturity by FY30, with the promise of better customer service, higher efficiency, and stronger profitability. To help get there, Telstra announced a proposed seven-year joint venture with Accenture in January 2025, aimed at accelerating its data and AI roadmap.

And this is where the infrastructure thread comes roaring back. Under Connected Future 30, InfraCo wasn’t just a bucket of “assets we used to own quietly.” It was positioned as a growth engine—tasked with delivering “solutions supporting the new era of AI and connectivity” and pursuing “new growth opportunities with partners,” as Telstra put it in investor materials.

InfraCo’s toolkit included its own data centre footprint—two “large” and five “small” data centres—plus links to around 150 third-party data centre facilities. It also had more than 7,500 fixed network sites, including more than 100 “potential edge sites” with 160 MW of capacity.

Because the bet Telstra is making is simple to describe and hard to execute: data demand keeps climbing, and AI is about to change what “good connectivity” even means. Mobile data on Telstra’s network has more than tripled over the past five years. And as AI applications spread, so will the need for low-latency, high-bandwidth connections—pushing compute and connectivity closer together, and making infrastructure a competitive weapon again.

XI. Competitive Dynamics: The Three-Player Oligopoly

By the mid-2020s, Australian telecom had settled into something close to a steady-state. Not a free-for-all, not a monopoly—an oligopoly. Three companies controlled most of the economics, and every strategic move was made with the other two in mind.

On the fixed and broader telecom revenue picture, the market was dominated by Telstra, Optus, and TPG, together accounting for the vast majority of industry share. Telstra led, but not by the kind of margin that lets you relax. And in mobile—the part of the business Telstra still truly controls end-to-end—its advantage was clearer. In 2023, the three major mobile operators were Telstra, Optus, and TPG Telecom, with subscription shares of 56.5%, 23.9%, and 13.1% respectively.

For years, Telstra’s playbook was simple: spend more, build more, win on coverage and reliability, and charge a premium for it. That strategy helped it stay on top through the NBN era, because mobile was the one place Telstra could still own the network and the customer experience.

Then Optus and TPG changed the geometry of the game.

In April 2024, Optus and TPG announced regional network-sharing agreements. Optus would be able to use TPG Telecom’s spectrum to support its 5G rollout in more regional areas, while TPG customers would gain access to Optus’s network. In plain language: they found a way to close the coverage gap without each company paying the full bill on its own.

That matters because Telstra’s strongest card has always been network leadership—especially outside the major cities. If Optus and TPG can share infrastructure costs, they can chase Telstra’s footprint with lower capital intensity. And it doesn’t take perfect parity to hurt Telstra; it just takes “good enough” coverage for a meaningful number of customers to stop paying extra.

The shift also highlighted a tension in Australian telecom policy. The ACCC endorsed the Optus–TPG pact in 2024. But it had previously blocked a Telstra–TPG deal, citing concerns about Telstra’s market power. The practical outcome is that infrastructure sharing became strategic orthodoxy—just not always equally available to the incumbent.

Fixed broadband, though, is a different sport.

In the NBN world, everyone is largely reselling the same underlying wholesale network. That flattens the playing field: you can’t easily win by having a better last-mile network, because you don’t control it. You win on pricing, packaging, customer service, and how cleanly you run operations.

In that environment, Telstra remained the largest NBN retailer, but the category also kept leaking share to smaller, more aggressive providers. Vocus, Aussie Broadband, and Superloop were among the names taking ground—often by being sharper on service and more ruthless on price. Telstra’s “we have the best network” story works brilliantly in mobile. In NBN resale, it’s much harder to make that story land, because the network isn’t meaningfully differentiated between providers.

If you’re trying to understand what this all means for Telstra’s competitive position, the simplest framing is this: mobile is where Telstra can still create a defensible edge, while fixed broadband is where it has to fight like a retailer.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis: - Supplier Power: Moderate. Telstra buys from major equipment vendors like Ericsson and Nokia, but its scale gives it negotiating leverage. - Buyer Power: Increasing. Customers have more choice and fewer reasons to stay loyal, and churn reflects that. - Competitive Rivalry: Intensifying. Optus and TPG’s network-sharing deal puts more pressure on Telstra’s premium positioning. - Threat of New Entrants: Low. The economics of telecom infrastructure still create real barriers to entry. - Threat of Substitutes: Moderate. Over-the-top apps keep replacing traditional voice and messaging revenue.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Assessment: - Scale Economies: Telstra spreads fixed network and operating costs over the largest customer base. - Network Effects: Limited in the platform sense, but enterprise relationships and ecosystems can create stickiness. - Counter-Positioning: Telstra’s premium strategy forces rivals to either spend heavily to match quality or compete on price with thinner margins. - Switching Costs: Moderate for consumers, higher for enterprises with complex deployments. - Branding: A powerful, long-standing brand—though the legacy of “old Telstra” still shows up in perception. - Cornered Resource: Spectrum, infrastructure access, and assets that are difficult to replicate at scale. - Process Power: Decades of network operations expertise, built through constant upgrades and high service expectations.

XII. Myth vs. Reality: Fact-Checking the Consensus Narratives

Telstra is the kind of company that attracts simple stories. It used to be a monopoly. The government “broke it up.” The NBN “killed it.” Now it’s supposedly coasting on a dividend until the lights go out.

Those stories are tidy. They’re also incomplete.

Several common narratives about Telstra deserve scrutiny:

Myth: Telstra is a dying ex-monopoly unable to compete in a deregulated market.

Reality: Deregulation did what it was meant to do: it introduced real competition, and Telstra has absolutely lost share since the early 1990s. But “lost share” isn’t the same as “lost relevance.” Telstra is still the clear leader in mobile, with about 56% subscription share. And the company didn’t just sit still operationally. T22 materially reset its cost base and how it runs day to day. Under the current management team, Telstra has delivered four consecutive years of underlying earnings growth.

Myth: The NBN destroyed Telstra's business model.

Reality: The NBN destroyed Telstra’s fixed-line monopoly economics. That distinction matters. The old profit pool—owning the copper into homes and harvesting wholesale-like returns—was dismantled by policy. But Telstra wasn’t left with nothing. The $11 billion in compensation payments helped fund the transition: investment, restructuring, and the transformation work that kept the company from getting stuck as a high-cost reseller. And while fixed broadband became structurally tougher, today’s Telstra earns the bulk of its money from mobile, which continued to grow despite the NBN disruption.

Myth: Telstra can't innovate because of its legacy infrastructure and culture.

Reality: Telstra has plenty of legacy baggage, but the idea that it can’t execute big, modern network moves doesn’t hold up. Next G in 2006 was a genuinely world-leading 3G rollout. And in the current era, Telstra’s 5G rollout has reached 91% population coverage. It’s also investing in a 14,000-kilometer intercity fibre network aimed at supporting the next wave of demand, particularly data centre connectivity in an AI-driven world. You can argue about whether these bets are enough, or whether they’ll earn attractive returns. But “Telstra can’t build” is the wrong critique.

Myth: Telstra is just a yield stock for retirees with no growth prospects.

Reality: Telstra’s dividend has always been part of the appeal, and it still is. But management is explicitly pitching something more than yield. Connected Future 30 targets mid-single digit compound annual cash earnings growth through 2030, with the mobile business still adding subscribers and lifting revenue per user. Enterprise fixed remains a tougher battlefield, but Telstra’s infrastructure footprint—especially as InfraCo becomes more central to the story—creates more than one path to value creation.

XIII. Key Metrics for Investors to Track

If you want to follow Telstra like an owner, not a headline reader, there are three numbers that tell you most of what you need to know. They cut through the strategy decks and get straight to the question: is the company strengthening its core, fixing its weak spots, and earning a decent return on all that investment?

1. Mobile Average Revenue Per User (ARPU)

Mobile is Telstra’s earnings engine, and ARPU is the cleanest read on whether it still has pricing power. When ARPU rises, it usually means Telstra is successfully holding a premium position—either by charging more, moving customers onto higher-value plans, or getting them to pay for a better 5G experience.

It’s also a proxy for competitive pressure. If Optus and TPG narrow the perceived network gap, ARPU is one of the first places that pressure shows up. In recent periods, Telstra’s postpaid handheld ARPU has delivered mid-single-digit growth, running ahead of inflation—evidence that a meaningful chunk of customers are still willing to pay for network quality.

2. Fixed Enterprise EBITDA Trajectory

This is the problem child.

Fixed Enterprise has been weighed down by the structural decline of legacy services, especially in Telstra’s NAS (Network Applications & Services) portfolio, which includes a lot of legacy voice. And that matters, because even if mobile is humming, a collapsing enterprise fixed business can drag the whole group away from its T25 ambitions.

FY24 made the issue hard to ignore: Fixed Enterprise underlying EBITDA fell 67% year on year. The key thing to watch isn’t a heroic turnaround overnight. It’s whether management can stop the bleeding—through cost reductions, tighter execution, and portfolio rationalisation—or whether the decline keeps accelerating.

3. Return on Invested Capital (ROIC)

Telstra can always spend. The harder question is whether that spending actually pays off.

With Connected Future 30 targeting 10% underlying ROIC by FY30, up from around 8% today, this becomes the scoreboard for everything else: 5G expansion, fibre builds, and the push into data, AI, and new infrastructure-led growth. Telecom is relentlessly capital-intensive, and ROIC is where you find out whether those investments are building a better business—or just a bigger one.

XIV. Bull Case and Bear Case: The Investment Debate

The Bull Case:

If you want to be optimistic about Telstra, the starting point is simple: demand for connectivity keeps rising, and Telstra is still the best-positioned company in Australia to meet it.

Data usage on Telstra’s mobile network has tripled over the past five years. That’s been driven by the obvious forces—video, cloud, work-from-anywhere—and now there’s a new accelerant in the mix: AI, which pulls more data through networks and raises the bar for speed and reliability. Telstra’s 5G rollout, now covering 91% of the population, gives it the foundation to keep charging a premium if customers continue to feel a real difference in quality.

There’s also an argument that the Optus–TPG network-sharing deal is an unintended compliment. Telstra’s historical playbook has been to spend more, build more, and win on coverage—especially outside the big cities. If rivals need to combine resources to narrow the gap, the bull case says that doesn’t weaken Telstra’s strategy; it validates it.

Then there’s the “infrastructure inside the telco” story. The partial sell-down of Amplitel put a market price on assets that used to be buried inside the group, and the valuation multiple implied there may be significant value in Telstra’s other infrastructure holdings as well. If AI-era computing pushes more demand into data centre connectivity and edge-style infrastructure, the bull view is that Telstra’s fibre, ducts, exchanges, and related assets become more valuable, not less.

Finally, the bull case leans heavily on execution. T22 wasn’t just a PowerPoint transformation—it delivered cost-out and simplification at real scale, leaving Vicki Brady with a cleaner, more operationally capable organisation than the one Andrew Penn inherited. If that operating discipline holds, the dividend story looks more resilient: supported by ongoing cash generation rather than nostalgia for the old monopoly-era economics.

Put it together, and the optimistic conclusion is that Telstra offers a rare mix: leading market position in mobile, tangible infrastructure leverage, and a credible management playbook—yet it still trades like a mature telco with limited upside.

The Bear Case:

The skeptical view starts from the same facts and flips the sign.

Optus and TPG’s network-sharing arrangement isn’t just “competition as usual.” It’s a deliberate attempt to change the economics of the game by closing Telstra’s coverage advantage without paying Telstra’s bill to get there. If “good enough” network quality spreads further into regional Australia, Telstra’s premium pricing becomes harder to defend—and in telecom, small changes in pricing power can hit earnings fast.

Meanwhile, Fixed Enterprise remains a real weak point. The NAS portfolio is in structural decline, and Telstra hasn’t yet found a clean way to offset that with faster-growing enterprise services. At the same time, the enterprise customer relationship itself is under pressure from multiple directions—more aggressive local competitors on connectivity, and hyperscalers and IT service providers moving up the stack into the kinds of solutions that used to anchor telco enterprise accounts.

The bear case also argues there just isn’t much “easy growth” left in Australia. The market is mature. Mobile penetration is already above 100%, and broadband is close to saturated. That leaves two levers: steal share, which tends to be expensive, or lift prices and revenue per customer, which is harder in an environment where households are sensitive to cost-of-living pressures.

And then there’s the biggest strategic worry embedded in the AI narrative: that AI could make connectivity more necessary but not more profitable. In that world, the winners are the companies that control applications and compute platforms, while telcos get stuck as the “dumb pipe”—essential, but structurally limited in the value they capture.

Over all of it hangs the most Australian risk of all: policy. Telstra’s last two decades have been shaped by government intervention, from deregulation to the NBN to strategic deals like Digicel Pacific. The bear case is that this never really goes away—and there’s no guarantee the next intervention helps the incumbent.

XV. What Investors Should Watch Going Forward

Connected Future 30 is where Telstra stops talking about reinvention and starts proving it. And as the plan moves from slide deck to execution, a handful of signals will tell you whether Telstra is building a stronger business—or just spending money with a good story.

5G Monetization: Telstra has long relied on network leadership to justify charging more. The question now is whether it can keep doing that as 5G becomes the baseline, not the differentiator. The simplest scoreboard is the gap between Telstra’s ARPU and its competitors’—if that spread holds, the premium brand is still earning its keep.

Enterprise Fixed Turnaround: Management has flagged “immediate and significant actions” to address underperformance in Enterprise fixed. The market doesn’t need a miracle overnight. It needs evidence that the decline is slowing and that execution is tightening, rather than the same problems repeating under a new label.

InfraCo Fixed Strategy: Brady has ruled out selling InfraCo Fixed “at least for the medium term.” That may be the right call—but this is also the kind of decision that can change quickly if valuations, capital needs, or strategic priorities shift. Any hint of renewed monetisation interest would be a major moment for value realisation.

Competitive Response to Optus-TPG: The Optus–TPG network-sharing deal changes the tempo of competition, especially in regional coverage and price-sensitive segments. Watch how aggressively they go after Telstra’s base—and whether Telstra responds by defending price, defending share, or some combination that squeezes margins.

AI Investment Returns: Telstra is placing real bets on AI, including the proposed Accenture joint venture and broader AI-focused investment. The only thing that matters is whether it shows up in outcomes: lower operating costs, faster customer service, better network operations, and measurable productivity gains—not just a bigger technology bill.

Dividend Policy: Telstra’s shareholder base still cares deeply about income. Connected Future 30 contemplates the possibility of partially franked dividends if growing fully franked dividends becomes impossible. Any shift here won’t be a footnote—it would land as a material change in the company’s promise to its most loyal investors.

XVI. Conclusion: A New Chapter for an Old Company

Telstra has survived what few companies ever face, let alone endure: a century of technological change, the shift from government monopoly to private competition, the blunt-force shock of the NBN, and now the start of an AI-driven rewiring of what “connectivity” even means.

The same organisation that once connected a newly federated nation by running copper lines across the outback now operates one of the world’s most advanced 5G networks. The bureaucracy that employed around 90,000 people in 1980 has been rebuilt into a roughly 26,000-person company running modern digital platforms and increasingly agile ways of working. The former government department that answered to ministers now answers to more than one million shareholders.

The open question isn’t whether Telstra can tell a compelling strategy story. It’s whether it can execute the next one. Connected Future 30 will test whether the operating discipline of T22 can hold in “growth mode,” whether InfraCo becomes a durable advantage and a source of optionality, and whether AI-era demand turns into real value—or simply pushes more traffic through networks without expanding margins.

One thing, at least, is not in doubt: telecommunications remains essential to Australian life and commerce. Someone will build, run, and keep upgrading the networks that connect homes, businesses, and communities across a continent.

Telstra’s 121-year track record suggests it plans to be that company—whatever the next era demands, and however many times the rules get rewritten. For investors, that makes Telstra more than a dividend stock or an ex-monopoly. It’s an ongoing case study in reinvention under pressure. And the story isn’t finished.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music