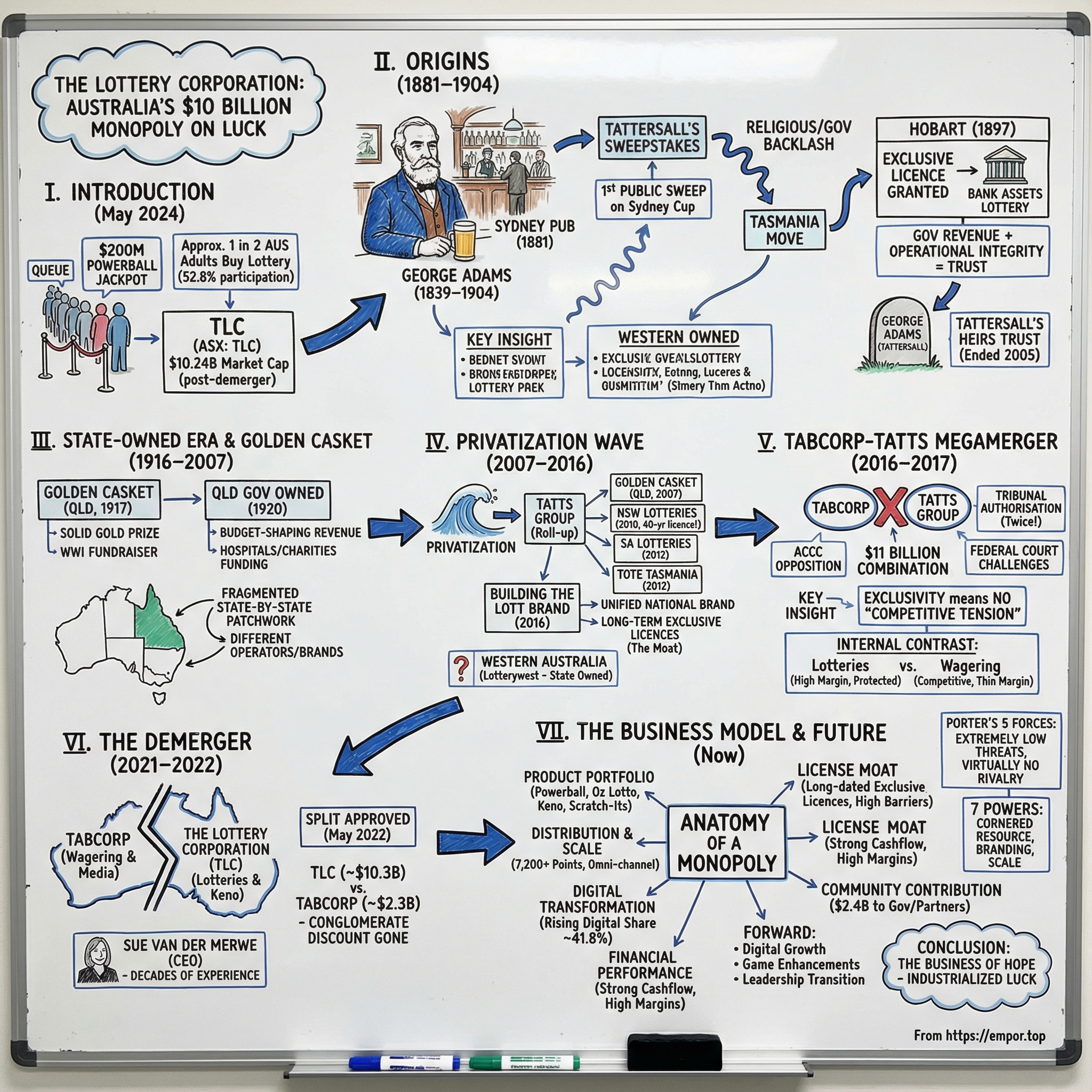

The Lottery Corporation: Australia's $10 Billion Monopoly on Luck

I. Introduction: The Business of Dreams

Picture May 2024. A line snakes out the door of a suburban Melbourne newsagency and down the block. Office workers on lunch break. Retirees with carefully folded entry forms. Couples whispering over number choices like they’re planning a heist. They’re all here for the same reason: Powerball has climbed to $200 million, the largest jackpot in Australian history.

When the draw closes, roughly one in every two Australian adults has bought a lottery ticket in the last year. There are very few products on Earth that can make that claim. In Australia, only one company can.

The Lottery Corporation (TLC) runs the country’s official lotteries and Keno. It owns the household-name games—Powerball, Oz Lotto, TattsLotto, and more—and it controls virtually every official lottery market in Australia outside Western Australia. Across its retail outlets, websites, and app, participation adds up to the equivalent of 52.8% of Australian adults buying a lottery product in the past 12 months—about 10 million people.

And here’s the twist: until recently, this was all tucked inside Tabcorp.

The Lottery Corporation began trading on the ASX in May 2022, born from a demerger that instantly clarified what had been hiding in plain sight. Split the lottery machine from the rest of Tabcorp, and the market could finally price it like what it was: a near-monopoly with unusually attractive economics. The result was stark—TLC worth about $10.24 billion, while the remaining Tabcorp sat around $2.2 billion.

So how did a 19th-century bookie’s side hustle turn into one of the world’s most profitable lottery monopolies?

The answer runs through 144 years of Australian history: colonial-era sweepstakes, governments hungry for reliable funding, a privatization wave that sold off state assets, and a company that patiently collected exclusive, long-dated licences—one jurisdiction at a time—until it owned “official” luck.

This is a story about a monopoly granted by law, the delicate dance of regulation and public trust, a business that sells dreams at scale, and what happens when that business goes digital.

Let’s dive in.

II. Origins: George Adams & The Birth of Australian Gambling (1881–1904)

The story begins not in a corporate boardroom, but in a Sydney pub in 1881.

George Adams (14 March 1839 – 23 September 1904) wasn’t born into Australian commerce. He was born in Redhill, in the parish of Sandon, Hertfordshire, England—the fourth son of William Adams, a farm labourer, and Martha (née Gilbey). His family emigrated to Australia, arriving on 28 May 1855.

What followed was reinvention, the hard way. Adams tried his hand as a gold miner in Kanoona, Queensland. He worked on sheep stations in New South Wales. He became a stock dealer and butcher in Goulburn. Then, in 1875, he traded meat for hospitality, buying the licence to run the Steam Packet Hotel in Kiama on the New South Wales south coast.

Adams also spent time at the Tattersall’s Club in Sydney, where he built a reputation as a good mixer—“a man with friends.” And he had a very specific ambition: he liked to say he’d love to own a hotel like Tattersall’s.

In 1878, three Sydney friends—George Hill, Bill Archer, and George Loseby—made that ambition real. They bought O’Brien’s Hotel for him because, as the story goes, “George Adams liked O’Brien’s and they liked George Adams.” The deal terms were almost absurdly simple: “pay when you can.”

That handshake understanding became the start of something much bigger. Within six years, Adams had paid them back and bought the freehold for another £40,000. Not long after, he was wealthy, with interests spanning coal (the Bulli colliery), electricity plants at Broken Hill, Newcastle, and Sydney, the collier Governor Blackall, and even the Palace Theatre in Sydney.

But none of that would make him famous.

The real engine was sitting in plain sight inside the Tattersall’s Club itself: sweepstakes run on race meetings. Club members subscribed. Bets were placed. Winners were paid. Adams ran them with a reputation for scrupulous honesty and efficiency—and the popularity spread. Then he made the move that mattered: he widened the circle.

He began including his hotel regulars. And in 1881, he ran the first public Tattersall’s sweep on the Sydney Cup.

That shift—taking a club pastime and turning it into something ordinary Australians could participate in—was the spark. It wasn’t just gambling; it was gambling with an audience, and a distribution model.

It also drew backlash fast. Religious groups opposed the sweeps, and in 1892 they persuaded the New South Wales government to pass laws prohibiting the delivery of letters containing sweepstakes. Adams moved to Queensland, which soon introduced similar legislation. So in 1895, he moved again—this time to Tasmania.

Six months later, Tasmania passed the Suppression of Public Betting and Gaming Act. Betting shops were prohibited. But certain lotteries were legalised.

What could’ve looked like defeat became the opening Adams needed. Tasmania was struggling through the depression of the 1890s, and the government needed cash. Adams was invited to help dispose of the property assets of the Bank of Van Diemen’s Land, then in liquidation. He did it by running a “grand lottery” to the value of 300,000 pounds, with the first prize being bank real estate valued at 26,000 pounds.

In return, Adams asked for what he really wanted: a licence to operate Tattersall’s sweeps legally in Tasmania.

On 1 June 1897, the Tasmanian Government granted Tattersall’s Consultations an exclusive licence to conduct lotteries under the Suppression of Public Betting and Gaming Act, 1896. The licence cost Adams £10,000—and, as one account puts it, it “permanently wedded the fortunes of the Government with the financial success of Tattersall’s Consultations.” In that first year in Hobart, the business employed 50 people and paid total wages of £4,400.

There was still politics to get through. After heated public and parliamentary debate, legislation was passed in October 1897, and in early 1898 Tattersall’s finally received the licence it had been chasing. It now had a home base that would last: Hobart for the next fifty-eight years. And it flourished—becoming, quickly, a meaningful source of government revenue.

Right here, the template clicks into place. Governments get dependable funding. Operators get exclusivity. And once a government gets used to that revenue stream, it becomes very hard to walk away.

Adams died in Hobart on 23 September 1904 and was buried at Cornelian Bay cemetery under a headstone engraved “George Adams (Tattersall).” But even in death, he left behind a structure that would shape the business for decades: when Tattersall’s was founded, he arranged it so the families of the original workers would inherit the profits. Those families became known as the “Tattersall’s heirs,” with subsequent generations receiving a share.

That unusual ownership model—a private trust benefiting the heirs of early employees—lasted for more than a century. It only ended in 2005, when the company decided to list on the Australian Securities Exchange, finally allowing the “Tattersall’s heirs” to sell and the public to buy in.

Adams didn’t just leave a company behind. He left a playbook: earn trust through operational integrity, build something ordinary people actually want to participate in, and—most importantly—align yourself with government incentives. The industry he helped create would spend the next century perfecting that formula.

III. The Era of State-Owned Lotteries & Golden Casket's Rise (1916–2007)

While Tattersall’s was entrenching itself in Tasmania and later pushing into Victoria, Queensland was building its own lottery institution—one that would become a household name long before anyone talked about “privatization.”

The Golden Casket Lottery was first held in Queensland in 1916. Today it’s recognised as one of the largest lottery organisations in the world. But it didn’t begin as a business move. It began as a war-effort fundraiser.

The idea came from the Entertainment Committee of the Queensland Patriotic Fund: run a lottery to raise money for World War I veterans. The first Golden Casket draw was held in 1917, with proceeds aimed at supporting returning soldiers. First prize was £5,000—often described as roughly $500,000 in 2019 terms.

There was one legal problem: cash prizes were prohibited. So the jackpot was paid in solid gold. The prize was presented in a small jewellery box—a casket—and the name stuck. The first draw took place in June 1917 at Brisbane Festival Hall (now the Brisbane Stadium), in front of an excited crowd that included Queensland dignitaries, like the Lord Mayor.

The inaugural draw also produced a very human little twist. A young man, John Zimmerle from Kingston, won first prize—but because he was underage, he couldn’t claim it until he turned 21.

What mattered, though, was the scale. The Golden Casket’s popularity was so immediate that, after it came to be owned by the Queensland Government in 1920, it reportedly lifted the Government’s budget by 2% within a year.

That is not “nice-to-have” money. That is budget-shaping money.

And the political cover was built into the model. The proceeds flowed into community and charity causes—supporting things like the Australian Soldiers Repatriation Fund, Anzac Cottages for war widows and their families, and the Motherhood, Child Welfare and Hospital Fund. Funds went to hospitals, baby clinics, bush nursing, kindergartens, and more. Golden Casket profits also supported organisations like the Red Cross, Queensland University, and the Surf Life Saving Association.

By 1938, Golden Casket profits had helped fund the construction of the new Royal Brisbane Women’s Hospital, backed by £238,000. Hospital treatment was also free for Queenslanders. Other states watched this play out and, through the 1930s, began introducing their own lotteries too.

This is where lotteries in Australia took on their lasting shape: not just gambling, but gambling with a moral argument attached. Religious groups, including the Council of Churches in Queensland, opposed government support for gambling on principle—arguing it legitimised something immoral. Governments, meanwhile, had a very practical question: how do you say no when the same revenue stream is paying for hospitals and veterans?

The tension never truly went away. It was simply outweighed by what the money could do.

Meanwhile, Tattersall’s kept expanding. In 1954, it acquired the Victorian public lottery licence. Over the next decade, public lotteries in other jurisdictions were state government-owned too, and Australia settled into a fragmented, state-by-state patchwork: different operators, different brands, different systems, each tied tightly to its own government and its own local identity.

That fragmentation would later matter a lot. Because when privatization finally arrived, “buying Australian lotteries” wouldn’t be one deal. It would be many—negotiated with different state governments, on different timelines, with different politics.

But before anyone could roll anything up, the states first had to build something worth selling. And by the end of this era, they had: lotteries treated like public infrastructure, woven into community funding and public trust—an arrangement that would prove both powerful and incredibly hard to unwind.

IV. Privatization Wave: Building the Monopoly (2007–2016)

By the mid-2000s, the states had spent nearly a century turning lotteries into something like public infrastructure: trusted brands, familiar retail networks, and a steady stream of money for governments and communities.

Then the question changed.

Instead of “Should we run this ourselves?” it became “What’s it worth if we sell it?”

For Tatts—by now evolving into the modern Tatts Group—this was the opening. What followed was one of the cleanest roll-ups in Australian business: not through price wars or product battles, but through the patient purchase of exclusive state licences, one after another.

From 2007, a wave of privatisations began. Tatts acquired Golden Casket, then NSW Lotteries in 2010, then SA Lotteries in 2012.

Golden Casket (2007): Queensland made the first big move. In 2007, the Queensland Government sold Golden Casket to Tatts for $530 million, ending 87 years of state ownership. For Tatts, this wasn’t just another asset—it was a deeply embedded institution with community legitimacy and proven demand. Golden Casket became a fully owned subsidiary of the Tatts Group.

NSW Lotteries (2010): Then came the biggest prize on the board: New South Wales. From 2 March 2010, NSW Lotteries has been operated by Tatts Group Limited under a 40-year exclusive licence. It ran through a network of agents—mostly newsagencies—under the Public Lotteries Act 1996 and within the government portfolio of Gaming and Racing.

The detail that mattered was the duration. Forty years is a lifetime in corporate strategy. It meant that whoever won this licence wasn’t just buying a business—they were buying decades of certainty. The NSW government also extended the newsagent monopoly on retail ticket sales from three to five years, and the privatisation was expected to deliver up to around $600 million to the state.

SA Lotteries (2012): South Australia followed, adding another exclusive state licence into the portfolio.

Tote Tasmania (2012): Not a lottery, but still part of Tatts’ broader consolidation story. Tote Tasmania was a Tasmanian Government-owned company, with shares held by the Treasurer and Minister for Racing. It held the exclusive right to conduct parimutuel (totalisator) wagering in Tasmania. Tatts bought it for AU$103 million and merged it into operations in 2012.

The Tatts-UniTAB merger (2007): Underneath all of this sat an important structural piece. Many of these assets had previously been owned by UniTAB, before UniTAB merged with Tattersalls Limited in 2007 to form the modern Tatts Group—bigger, better resourced, and ready to go shopping.

By the mid-2010s, the picture was clear. Tatts Group had stitched together a near-monopoly across the country. Tatts Lotteries—its lotteries operating unit—owned or leased the key operators: Tatts Lottery in Victoria, Tasmania, and the Northern Territory; Golden Casket in Queensland; NSW Lotteries in New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory; and SA Lotteries in South Australia.

Building The Lott brand (2016): Once you own the map, the next step is to make it feel like one country. On 1 June 2016, Tatts created a national brand called The Lott, bringing the jurisdictional lottery brands under one umbrella. It was a simple idea with big implications: unify the customer experience, standardise trust, and make “official lotteries” feel seamless—no matter which state you were in.

This is the core pattern that made the whole machine so powerful. Each deal wasn’t about beating a competitor; it was about acquiring exclusivity by contract. Multi-decade terms. State-based regulation. Governments reliant on the ongoing revenue stream. Once Tatts secured a licence, the barriers to entry weren’t merely high—they were written into law.

All of the licences entitle the company to the exclusive operation of physical betting shops which offer totaliser, fixed odds and sports wagering in their respective jurisdictions.

One state didn’t follow the script: Western Australia. While Tatts, and later The Lottery Corporation via The Lott, took over the operation of official lotteries across the country (with states still retaining legal ownership), Western Australia kept its lottery in-house. Lotterywest remained the only state-owned and operated lottery in Australia.

Lotterywest has supported the WA community since 1933, and it operates on a different premise: profits go back to the community through Lotterywest grants. It generates around AU$1.3 billion in annual sales across retail and digital, returning more than AU$1.1 billion each year through prizes and grants.

In other words, WA is the counterfactual—the reminder that lotteries can stay public forever.

It’s also the one major market the now–Lottery Corporation doesn’t dominate.

V. The Tabcorp-Tatts Megamerger (2016–2017)

If Tatts’ decade-long roll-up was impressive, the next move was outright audacious: fuse Tatts with the other giant of Australian gambling.

The deal had been in motion since October 2016, when Tabcorp Holdings Ltd and Tatts Group entered into a Merger Implementation Deed. The structure was a Tatts scheme of arrangement; the headline was even bigger. On 13 December 2017, after Supreme Court approval, the merger became effective—an approximately $11 billion combination that had dragged through one of the longest and most contested transaction timelines in recent Australian corporate history.

What happened in between was the real story.

Tabcorp initially went down the conventional path, seeking informal clearance from the ACCC. On 9 March 2017, the ACCC issued a Statement of Issues, and the message was clear: two dominant players in Australian gambling trying to become one was not going to be waved through.

So Tabcorp changed the game mid-play. In March 2017, it took the merger directly to the Australian Competition Tribunal, effectively bypassing the informal ACCC process that had been running since October 2016 and had already reached a “phase 2” level of scrutiny.

This wasn’t a routine move. It was only the third time a merger authorisation had gone straight to the Tribunal since direct applications were allowed.

The Tribunal hearings ran from 16 May to 2 June 2017, before a panel comprising Justice Middleton (President), Mr Grant Latta AM, and Dr Darryn Abraham. On the final day, the ACCC argued the public benefits Tabcorp claimed didn’t justify the merger. But later that month, the Tribunal authorised it anyway.

Then the fight escalated.

On 10 July 2017, the ACCC applied to the Federal Court for judicial review. Crownbet Limited filed a separate application. The Full Court heard both in late August, and in September 2017 it sided with the ACCC—setting aside the Tribunal’s authorisation and sending the matter back for reconsideration.

For a moment, it looked like the regulator had landed the decisive blow. But the saga wasn’t over.

The case returned to the Tribunal in October. On 17 November 2017, the Tribunal authorised the merger again. And on 1 December, the ACCC said it would not seek judicial review of this second decision—clearing the way for the deal to close.

What made this entire battle so fascinating wasn’t just the procedural drama. It was what it revealed about how competition works in a world of state-granted exclusivity.

A central thread in the reasoning was that Tabcorp and Tatts weren’t simply competing head-to-head like two normal consumer businesses. They each held exclusive licences in different jurisdictions, awarded by governments. That exclusivity meant there often wasn’t “competitive tension” to eliminate in the first place—at least not in the core retail channels inside their licensed territories. The Tribunal wrestled with the definition of the wagering market, noting that if you define the market to include all wagering products, it becomes hard to call restrictions in a segment of that market a “substantial” lessening of competition.

In other words: if you already have legal monopolies carved up by state borders, what exactly is a merger taking away?

The scheme’s final approval came after those two successive Tribunal authorisations, the Federal Court reversal of the first, and the eventual green light on the second. Along the way, Tabcorp also completed the sale of its Queensland gaming business Odyssey to Australian National Hotels—a condition it had accepted early in the Tribunal process.

And Tatts shareholders? They were emphatic. More than 98% of votes cast at the 12 December meeting supported the scheme.

For investors, the merger also put a spotlight on an internal contrast that would only sharpen with time. Inside the combined group, the lotteries and Keno assets sat on one side: predictable, high-margin, and structurally protected by long-term exclusive licences. On the other side was wagering: a business exposed to online bookmakers, tougher competition, and thinner margins.

The merger created the largest gambling company in Australian history. But it also made something else obvious: lotteries behaved like a very different kind of business.

And that difference would soon force the next move—the demerger.

VI. The Demerger: Birth of The Lottery Corporation (2021–2022)

By 2021, the logic inside Tabcorp had become hard to ignore: it was housing two fundamentally different businesses under one roof. One was a structurally protected lotteries-and-Keno machine, built on long-term exclusive licences and mass-market habit. The other was wagering and media—more exposed, more competitive, and far less predictable.

On 5 July 2021, Tabcorp’s board moved to resolve that tension. Directors unanimously recommended shareholders vote in favour of demerging the Lotteries and Keno operations from the rest of Tabcorp.

In its Demerger of The Lottery Corporation – Briefing Presentation, Tabcorp pitched the split as the “next phase” of the company’s evolution: two standalone ASX-listed entities—The Lottery Corporation and what it referred to as “New Tabcorp.” The argument was simple: separate leadership teams, clearer strategies, and financial policies that fit the realities of each business. Put a different way: stop forcing a steady, cash-generative monopoly to be valued alongside a wagering business fighting for share.

There was also an unspoken truth behind the corporate language. For years, lotteries had been the dependable performer. Wagering and media—home to brands like TAB and SKY Racing—had struggled to match it, returning to growth for the first time in four financial years in 2020–21, before coming under pressure again in the first half of 2021–22. Over that same period, the lotteries business delivered a record result.

Then came the mechanics. On 12 May 2022, Tabcorp shareholders overwhelmingly approved the demerger. Tabcorp then sought court approval, and on 20 May 2022 the Supreme Court of New South Wales approved the scheme. The transaction became effective on 23 May 2022, and The Lottery Corporation’s shares were expected to begin trading on the ASX on 24 May, initially on a deferred settlement basis. The demerger was implemented on 1 June 2022.

The market’s verdict arrived immediately. On debut, investors piled into the lotteries and Keno business, and The Lottery Corporation effectively landed on the boards as a roughly $10 billion company.

The contrast with what was left behind at Tabcorp was stark. With Tabcorp trading around $1.03, it was valued at roughly $2.3 billion. With TLC trading around $4.63, it was valued around $10.3 billion. In other words, the newly independent lotteries division was worth about five times the remaining Tabcorp business.

That wasn’t just a pop. It was the market repricing what had been hiding in plain sight: lotteries behaved like the crown jewel, and the conglomerate structure had been masking it.

The new company didn’t waste time framing its identity. CEO and Managing Director Sue van der Merwe emphasised the “defensive qualities” of the business and its tendency to perform well through downturns. In FY22, The Lottery Corporation reported revenue of AUD $3.5 billion, up 9.4% from the prior year when it still sat inside Tabcorp’s divisional reporting.

“The Lottery Corporation’s games have been adding excitement to the lives of Australians for decades,” van der Merwe said. In FY22, the company sold more than 660 million lottery entries and rolled out changes and initiatives aimed at improving the customer experience, including an Oz Lotto game change implemented in May designed to deliver bigger prizes and more winners, alongside enhancements to responsible play programs. The business also highlighted its role as a major funding engine: FY22 operations generated $1.7 billion in lottery and Keno taxes for governments, and more than $500 million in commissions for newsagents, licensed venues, and other retail partners.

Van der Merwe was also a signal of continuity. She became The Lottery Corporation’s CEO at the demerger in 2022, but she had already been running the Lotteries & Keno division inside Tabcorp since the 2017 combination with Tatts. Before that, she was Chief Operating Officer of Lotteries at Tatts Group. Across a 33-year career in lotteries, she played a central role in the industry’s development, including the acquisition of multiple licences and the integration of those businesses.

She also held prominent industry roles: Chair of the Asia Pacific Lottery Association, a seat on the World Lottery Association Executive Committee, and induction into the Public Gaming Research Institute’s Lottery Industry Hall of Fame in 2016.

For investors, the lesson was classic—and brutally clear in the numbers. Conglomerate discounts are real. When you split a defensive, state-licensed monopoly from a fiercely competitive wagering operation, you don’t just create two tickers. You let the market finally value each business on its own terms.

And once The Lottery Corporation stood alone, it became easier to see what it really was: not just a division, but one of the most structurally advantaged businesses in the country.

VII. The Business Model: Anatomy of a Lottery Monopoly

Now that The Lottery Corporation is a standalone company, you can see the machine for what it is. This isn’t “gambling” in the sports-betting sense. It’s a very specific business: a regulated, mass-market habit built on trust, distribution, and exclusivity—and those ingredients produce unusually strong economics.

The Product Portfolio:

TLC doesn’t sell one game. It sells a menu of dreams, tuned to different moods and motivations: Powerball, Oz Lotto, TattsLotto and Saturday Lotto, Set for Life, Weekday Windfall, Lucky Lotteries, Lotto Strike, Super 66, Instant Scratch-Its, and Keno.

The mix matters. Powerball and Oz Lotto are the headline acts—the mega-jackpot, “what if?” moments that take over the national conversation. Set for Life is a different promise: security and stability, paid out over time. Scratch-Its are about immediacy—tiny stakes, instant outcome. And Keno is its own category entirely: a social, venue-based game in pubs, clubs, hotels, casinos, and TABs, running every few minutes and designed to be played in the background of a night out.

Different products, same core behavior: the purchase of possibility.

Distribution & Scale:

TLC’s other superpower is where it shows up. It operates through more than 7,200 points of retail distribution, alongside a mature online channel across web and mobile. As at 30 June 2024, that footprint included 3,858 lotteries outlets and 3,354 Keno venues.

It’s hard to overstate what that means operationally. Every newsagent counter, every convenience store terminal, every venue with a Keno screen becomes part of the same ecosystem. Management calls it omni-channel: the same trusted brands sold everywhere Australians already go.

Market Penetration:

That distribution turns into something rare: genuine mass participation. In the last 12 months, the equivalent of 52.8% of Australian adults purchased a lottery product—about 10 million players.

And the company increasingly knows who those players are. As at 30 June 2024, TLC had 4.75 million active registered customers in its Lotteries database, and that cohort accounted for about 59.1% of FY24 turnover.

This is not a niche entertainment category. It’s one of the broadest consumer franchises in the country.

The Digital Transformation:

The biggest shift inside the business is the steady migration from counter to click. In FY24, digital turnover grew and the digital share of lotteries turnover rose to 40.9%, supported by increased digital investment and growth in products like Store Syndicates Online.

This isn’t just a convenience upgrade; it’s economically meaningful. Digital sales tend to be margin-accretive because they reduce reliance on retail commissions. Each step of customer behavior that moves from a physical terminal to the app reshapes the cost structure in TLC’s favour.

The License Moat:

Underneath the products and the channels is the real asset: long-dated, exclusive licences under a complex state-based regulatory framework.

Those licences are why TLC can look so “defensive” as a business. They protect the core markets, they underpin the trust of “official lotteries,” and they let the company invest in marketing, product changes, and digital infrastructure without worrying that a competitor can show up next door offering the same thing.

The company describes itself in a way that reads like a checklist of monopoly advantages: exclusive and long-dated licences, a diversified portfolio of high-profile games, a vast distribution network, low capital intensity, strong cashflow generation, and further upside from digital growth. It also notes an average remaining licence length of 22 years, including the Victorian lotteries licence that is currently due to expire in June 2028.

Financial Performance:

When you sell hope at scale, results can swing with jackpot cycles, but the underlying engine is powerful.

In FY24, TLC reported strong growth: revenue rose to $4 billion and EBITDA increased to $827 million. It also delivered a record $2.6 billion in stakeholder benefits, made up of $1.9 billion in lotteries and Keno taxes to state and territory governments and $725 million in commissions to retail businesses.

That year was also helped by blockbuster jackpot activity, including the May $200 million Powerball draw. TLC said around one out of every two Australian adults bought a ticket for that jackpot, and it drove a surge in turnover for the period.

Then FY25 showed the flip side: fewer extraordinary jackpots meant softer top-line results. Revenue fell to $3.75 billion and EBITDA (before significant items) to $749.3 million, with NPAT (before significant items) at $365.5 million. But digital kept edging up, with digital lotteries turnover share rising to 41.8%. And the company still increased its ordinary dividend to 16.5 cents per share, fully franked.

The takeaway isn’t that jackpots “make” the business. It’s that jackpots create spikes on top of a model that’s already built to throw off cash.

The Community Contribution:

Finally, there’s the part that makes the whole structure socially and politically sustainable: the money doesn’t just stay with the company.

TLC returned $2.4 billion to governments, and to retail and venue partners. This isn’t an add-on. It’s the compact. Governments tolerate—and often actively support—lotteries because they deliver substantial tax revenue, and because the ecosystem pays commissions into thousands of small businesses and venues. That flow of benefits is what keeps the licences legitimate, the brands trusted, and the monopoly intact.

VIII. Competitive Analysis: Porter's Five Forces

To really understand why The Lottery Corporation is so valuable, you have to stop thinking about it like a normal consumer company and start treating it like an industry structure. Porter's Five Forces is a useful lens here, because it makes the point plain: TLC doesn’t just compete well. In most of its core markets, it barely competes at all.

1. Threat of New Entrants: EXTREMELY LOW

This is where the whole story snaps into focus. State-granted exclusive licences create legal barriers that are effectively impossible to cross. You can’t wake up one morning and decide to launch a competing “official” lottery in New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, or South Australia. Those rights have already been granted, and they run for decades.

All of the licences entitle the company to the exclusive operation of physical betting shops which offer totaliser, fixed odds and sports wagering in their respective jurisdictions.

In New South Wales, that exclusivity runs all the way to 2050. And even if the law allowed entry, you’d still face the harder moat: trust. TLC’s brands have been built over more than 140 years, under heavy regulation, alongside government oversight. Compliance requirements are intense, relationships with state governments take a long time to earn, and the “official” status can’t be bought with capital. Without a licence, you simply don’t have a business.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

If TLC has suppliers with real leverage, it’s the state governments—because they grant the licences. But here’s the catch: once those licences are in place, switching becomes extremely difficult.

Governments rely on lottery taxes as a dependable funding source. Pulling a licence isn’t like changing a vendor; it creates political and financial pain, and it disrupts a revenue stream that’s baked into budgets.

Most other suppliers have even less power. Technology vendors—terminal manufacturers, software providers—are largely interchangeable, and TLC’s scale makes it an attractive customer. Retail partners matter, but the balance of power leans toward TLC: newsagencies and venues value lottery commissions and the foot traffic lotteries generate, and TLC has a huge network of distribution points.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: VERY LOW

On the customer side, there’s essentially no negotiating power at all. Individual players can choose to participate or not, but they can’t bargain over pricing, odds, game design, or draw rules.

When the $200 million Powerball jackpot landed, about half the adult population showed up. And they all did it on TLC’s terms.

Even the scale of participation—52.8% of Australian adults buying a lottery product in the last 12 months—doesn’t translate into buyer power, because it isn’t coordinated. It’s millions of small decisions, not one organised customer group.

And the “official” status matters here too. For many players, the product isn’t just a ticket—it’s confidence that the draw is regulated, legitimate, and backed by government oversight. That trust isn’t easily replaced.

4. Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE (and evolving)

The main competitive pressure isn’t another official lottery operator. It’s alternative ways to spend gambling dollars.

Online gambling and sports betting compete for discretionary spend, and that market has been far more aggressive and dynamic than lotteries. There are also lottery-related substitutes and workarounds. The Lottery Office (operating under Global Players Network Pty Ltd) sells entries tied to government-approved Australian lotteries and matches them with tickets in corresponding overseas lottery draws. Intralot operates in Tasmania. Jumbo Interactive and Netlotto operate as online re-sellers of lotteries.

Synthetic lottery products also exist—bets on lottery outcomes rather than the purchase of an official ticket—but they lack the same legitimacy for many consumers. And Western Australia remains outside TLC’s monopoly entirely, with Lotterywest staying government-owned.

Still, lotteries sit in a psychologically different place. Sports betting is about entertainment and adrenaline. Lotteries are aspirational. They sell the idea of a life reset. That’s not a perfect shield, but it is a real differentiator.

5. Industry Rivalry: VIRTUALLY NON-EXISTENT

This is the unusual part, and it’s the one most businesses would kill for: in TLC’s core lottery markets, there is no direct rivalry. Exclusive licences remove the normal day-to-day competitive fight.

The only true competitive moments come when licences are up for renewal—events measured in decades, not quarters—and in the broader battle for share-of-wallet against other forms of gambling. In the meantime, the absence of direct competition means far less pressure to discount, to over-spend on marketing just to defend share, or to engage in the kind of price wars that destroy margins in other consumer categories.

Porter's Verdict: Near-perfect competitive positioning. TLC is a regulated monopoly protected by long-dated licences, reinforced by brand trust, and supported by government reliance on lottery tax revenue. In most industries, moats erode. Here, the moat is written into law—at least for the duration of the licences.

IX. Strategic Analysis: Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework

Porter tells you what the battlefield looks like. Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers tells you why one player gets to keep winning on that battlefield, year after year.

1. Scale Economies: STRONG

Lotteries are a scale business in disguise. The big costs—technology platforms, regulatory compliance, security, marketing—don’t rise neatly with every extra ticket sold. Once the engine is built, every additional player is mostly gravy.

TLC also has a distribution advantage that’s hard to replicate: more than 7,200 points of sale across the country. That footprint doesn’t just sell tickets; it keeps the brands constantly visible, embedded in daily routines.

And then there’s jackpot pooling. A Powerball draw that’s pooled across New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, and the Northern Territory can climb to prize levels that a single-state operator simply couldn’t generate. Bigger jackpots create bigger moments, and bigger moments create more play. TLC is the leader in Australia’s lotteries and Keno market, and one of the highest-performing lotteries businesses globally, because it can manufacture national scale from a patchwork of state licences.

Digital strengthens the scale story further. Building and improving the online platform is largely a fixed-cost exercise. Serving millions of registered customers doesn’t require a platform that’s “millions of times bigger” than serving a smaller base. As digital penetration rises, unit economics improve.

2. Network Effects: MODERATE

Lotteries have an indirect network effect: the more people who play, the bigger jackpots can get; the bigger the jackpot, the more people pay attention; and the more attention, the more people play.

The $200 million Powerball draw is the cleanest example. It became a national event—earned media, social conversation, office syndicates, last-minute queues—all feeding the loop.

But it’s not infinite. Eventually you hit saturation: there’s only so much participation you can unlock from a country, even when the prize gets absurdly large.

3. Counter-Positioning: LIMITED

Counter-positioning is when a newcomer uses a business model the incumbent can’t copy without hurting itself.

TLC doesn’t really have this power because it is the incumbent. If anything, the attempted counter-positioning has come from outside: offshore lottery betting and lottery-adjacent operators offering “bets” on international lottery outcomes.

But in Australia, the “official” nature of government-backed lotteries matters. Regulation and legitimacy both lean heavily toward TLC, and the alternatives don’t carry the same trust.

4. Switching Costs: LOW for individuals, HIGH systemically

For an individual customer, switching costs are basically zero. You can stop playing tomorrow.

But zoom out to the ecosystem, and switching costs become massive. Retailers rely on commissions. Venues rely on Keno to drive dwell time. Governments rely on the tax stream. And the brands themselves—built over more than a century—aren’t something a competitor can recreate by spending on advertising for a few years.

So while customers can leave easily, the system is built to keep TLC in place.

5. Branding: VERY STRONG

This is a trust business. People hand over money for a chance at a prize they may never see, and they do it because they believe the game is legitimate and the operator is reliable.

TLC’s brands—Tattersall’s, Golden Casket, NSW Lotteries, and the national umbrella The Lott—carry emotional weight in Australia. They’re tied to a cultural ritual: “I’ll grab a ticket,” “join the syndicate,” “imagine if.” That kind of trust is slow to build and fast to lose, which is exactly why it becomes a moat once earned.

That brand strength is also a defence against synthetic or offshore alternatives that can mimic the idea of a lottery but can’t replicate the same legitimacy.

6. Cornered Resource: EXTREMELY STRONG

This is the real power—the one all the others orbit around.

TLC’s exclusive licences are cornered resources: finite, legally protected rights that competitors cannot access. The New South Wales licence runs until 2050. Victoria’s licence is due to expire in 2028 and will require renewal, making it a key date to watch. Other jurisdictions—Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, the Northern Territory, and the ACT—also grant multi-decade exclusivity.

These aren’t normal advantages like “we’re better at marketing.” They are government-granted monopolies. TLC holds the right to operate the official lotteries across most of Australia.

7. Process Power: DEVELOPING

Process power is what happens when an organisation gets so good at operating its system that execution itself becomes a moat.

TLC has decades of embedded capability: designing games and prize structures, managing regulatory relationships across multiple state governments, operating a vast retail network, and building digital platforms and customer analytics.

Leadership is part of that institutional memory. Sue van der Merwe’s long career in lotteries, and her role in acquiring licences and integrating operations, is a signal that this company has deep operational expertise, not just contracts.

Still, it’s important to be clear-eyed: TLC’s process power is real, but it’s reinforced by the cornered resource of exclusive licences. The licence moat comes first; great execution makes the moat pay out even more.

7 Powers Verdict: The Lottery Corporation’s defensibility is anchored in Cornered Resources—exclusive, long-dated licences—then strengthened by Scale Economies and Branding, with Process Power compounding the advantage over time.

X. Key Investment Considerations

The Bull Case:

The Lottery Corporation is, in many ways, the cleanest kind of gambling asset investors ever get offered: a regulated monopoly with long-dated licences, predictable cash generation, and a built-in growth lever as more play shifts online.

It has also shown an ability to hold up through tough cycles. Management has pointed to the historical record: sustained revenue growth through downturns, including the GFC, and even increased interest through COVID.

The digital story is the other big pillar. Over the last six years, digital’s share of turnover rose from about a quarter to the low-40s. That matters because digital sales are typically margin-accretive: fewer intermediaries, less reliance on retail commissions, and more direct customer relationships.

Then there’s diversification. TLC isn’t a single-game business. The portfolio spreads demand across jackpot-driven games like Powerball and Oz Lotto, “steady promise” games like Set for Life, instant products like Scratch-Its, and venue-based Keno. And with participation equivalent to 52.8% of Australian adults buying a lottery product in the past year, this isn’t a niche habit. It’s embedded in Australian life.

Finally, the licences themselves tend to become more valuable over time. As governments grow used to the tax stream lotteries generate, walking away becomes politically difficult. That dependence, paradoxically, can strengthen the franchise—because the path of least resistance is usually renewal.

The Bear Case:

The same licence structure that creates the moat also creates the biggest risk: concentration. One renewal matters a lot. The key date investors watch is Victoria, where the licence is due to expire in June 2028. A renewal failure would be material, even if it’s viewed as unlikely.

Regulation is the other ever-present variable. Governments can change the economics by shifting taxes, tightening advertising rules, or adding compliance requirements that raise costs or reduce turnover.

Competition also doesn’t have to be “another official lottery” to matter. Digital wagering and online gambling fight for the same discretionary entertainment dollar. And there’s a generational question: younger customers may be more drawn to interactive, skill-based products than a passive weekly ticket.

Then there’s jackpot volatility. Big jackpots create big spikes, and FY24 had unusual strength, including the $200 million Powerball draw. That kind of year is hard to repeat on command. The risk for investors is confusing a lucky cycle with underlying business momentum.

And unlike many consumer businesses, international expansion is limited. Lottery licences are jurisdiction-specific, and most attractive markets already have established operators.

Key Metrics to Monitor:

For investors tracking The Lottery Corporation, three KPIs matter most:

-

Digital Share of Turnover - About 41.8% and rising. Every step from retail to digital tends to improve margins. This is the clearest read on whether the digital strategy is working and whether unit economics should keep improving.

-

Active Registered Customers - About 4.75 million. Growing the registered base means TLC is building direct relationships, enabling more targeted marketing, and reducing reliance on retail partners. Over time, that customer database becomes a strategic asset.

-

EBITDA Margin - Around 19.5%. Revenue will move around with jackpot activity, but sustained margin improvement is what signals mix shift, operating leverage, and underlying business strength.

Material Risks:

Regulatory: State governments ultimately control the rules of the game. Even if licence renewal has not been denied in modern Australian history, future governments could tighten terms, raise taxes, or—in an extreme shift—move back toward government-operated models.

License Renewal: The Victorian lotteries licence is due to expire in June 2028. TLC notes an average remaining licence length of 22 years, but Victoria is the near-term exception, and any signals around that renewal will matter.

Competition from Offshore Operators: Synthetic lottery products and offshore betting on lottery outcomes remain an ongoing pressure point. Regulation has contained this to date, but that balance could change.

Responsible Gambling: Expectations are moving. New responsible play measures can raise costs or reduce turnover, particularly online. TLC has noted that digital Keno turnover declined after mandatory online spend limits were introduced as part of a broader sustainability push.

XI. Looking Forward: Sustainability and Evolution

After all the history, all the licences, and all the structure, the day-to-day reality of running this business is surprisingly simple: keep the franchise trusted, keep the portfolio fresh, and keep the channel mix moving in your favour.

That’s exactly how The Lottery Corporation framed its FY25 result. Management described a year of “resilient performance,” helped by portfolio diversification and active management—especially important because FY25 came straight after FY24’s record jackpot cycle.

The numbers told that story. Revenue came in at $3.7 billion and EBITDA at $749.3 million. Not a collapse—more like gravity returning after an unusually strong year. The company pointed to continued growth in lotteries’ digital share, supported by an improved customer experience. It also highlighted product tweaks designed to keep the portfolio humming even when jackpots aren’t setting records: an extra Weekday Windfall draw on Fridays that delivered around $90 million in incremental turnover, and early signs that customers stuck around after a Saturday Lotto price increase. Another change is queued up too: a Powerball entry price increase is planned for November 2025.

Under the hood, TLC is also upgrading the plumbing. A new terminal rollout has begun—Queensland lotteries is complete—positioning the business for further digitalisation. And on the Keno side, TLC pointed to retail growth driven by local marketing initiatives and increased venue visitation.

Importantly, the “compact” remained intact. TLC highlighted a strong community contribution, with $2.4 billion returned to governments and to retail and venue partners. That’s not just a nice line in a press release; it’s a big part of what keeps the monopoly politically sustainable.

“The Lottery Corporation’s portfolio diversification and active management helped to deliver a resilient performance this year, as we continued to build strong foundations for a sustainable future,” CEO Sue van der Merwe said.

Looking into FY26, TLC’s priorities read like the next logical chapter: push digital share higher, roll out game enhancements, and keep squeezing productivity improvements. The company also said shareholders should see the full benefit of the recent Saturday Lotto price adjustment, and from November, the planned Powerball entry price increase—subject to regulatory approval.

And then there’s the big internal bet: investment. TLC is stepping up spending on digital transformation and core infrastructure as part of a three-year program to modernise its systems. The goal is straightforward: faster product launches and a smoother omni-channel experience, so the customer can move between retail and digital without friction.

But FY26 won’t just be about systems and price points. It will also mark a leadership handover.

The Lottery Corporation has confirmed that Managing Director and CEO Sue van der Merwe will retire at the end of this year. She has served as MD and CEO since June 2022, appointed following the demerger from Tabcorp. Before that, she led Tabcorp’s Lotteries & Keno division from the 2017 combination of Tabcorp and Tatts. And before that, she was Chief Operating Officer of Lotteries at Tatts.

Chairman Doug McTaggart put it plainly: “Sue has played an instrumental role in the success of the lottery industry in Australia over more than three decades. Her deep experience and expertise have helped TLC to become the leading operator of lottery and Keno games in Australia and one of the best performing lottery businesses in the world.”

It really is the end of an era. Van der Merwe’s 33-plus years in lotteries stretch across the entire modern arc of the industry: the shift from state-owned fragmentation to privatisation, consolidation, the Tabcorp merger, and finally the demerger that created the standalone company she went on to lead.

Her successor inherits an unusually enviable seat: Australia’s largest lottery operator, one of the highest-performing lottery businesses in the world, and a company now standing on its own on the ASX as TLC.

XII. Conclusion: The Business of Hope

The Lottery Corporation’s 144-year journey—from George Adams running a public sweep on the Sydney Cup to a $10+ billion, ASX-listed giant—tells a distinctly Australian story.

It’s a story about governments discovering a revenue stream they couldn’t quit. About moral objections that never disappeared, but kept losing to budgets, hospitals, and community funding. About a privatisation wave that turned state assets into once-in-a-generation paydays, and then quietly handed a national habit to a private operator. And above all, it’s about the patient accumulation of something far more valuable than brand names: long-dated, exclusive licences, collected one jurisdiction at a time until “official lotteries” across most of Australia effectively meant one company.

Today, The Lottery Corporation Limited provides gaming services in Australia, operating lottery and Keno games under The Lott and Keno brand names.

For investors, TLC is a rare creature in modern markets: a moat built not just on scale and trust, but on legal exclusivity and government co-dependence. The product is simple—hope, sold cheaply, at mass participation scale—and it has proved resilient across economic cycles, pandemics, and shifting consumer habits.

“FY24 was another successful year for The Lottery Corporation, showcasing the resilience and long-term attractiveness of our balanced and diversified game portfolio,” CEO Sue van der Merwe said. “Lotteries continue to be very popular among Australian adults, underpinned by a low-spend, mass participation model. This was evident in the second half with the record $200 million Powerball jackpot generating queues in retail outlets and sparking conversations in homes and workplaces.”

And that’s the real point. Millions of Australians buy tickets each week not because they’re doing the maths and liking the odds, but because the possibility makes the week feel different. That’s what Adams understood all those years ago, and it’s what The Lottery Corporation has industrialised ever since. The odds didn’t improve. The dream didn’t change. The distribution did. The licences did. The scale did.

From a farm labourer’s son taking bets in a Sydney pub to one of the highest-performing lottery businesses globally, this is the story of Australia’s monopoly on luck.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music