Suncorp Group: From Queensland's Government Insurer to Australia's Insurance Powerhouse

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

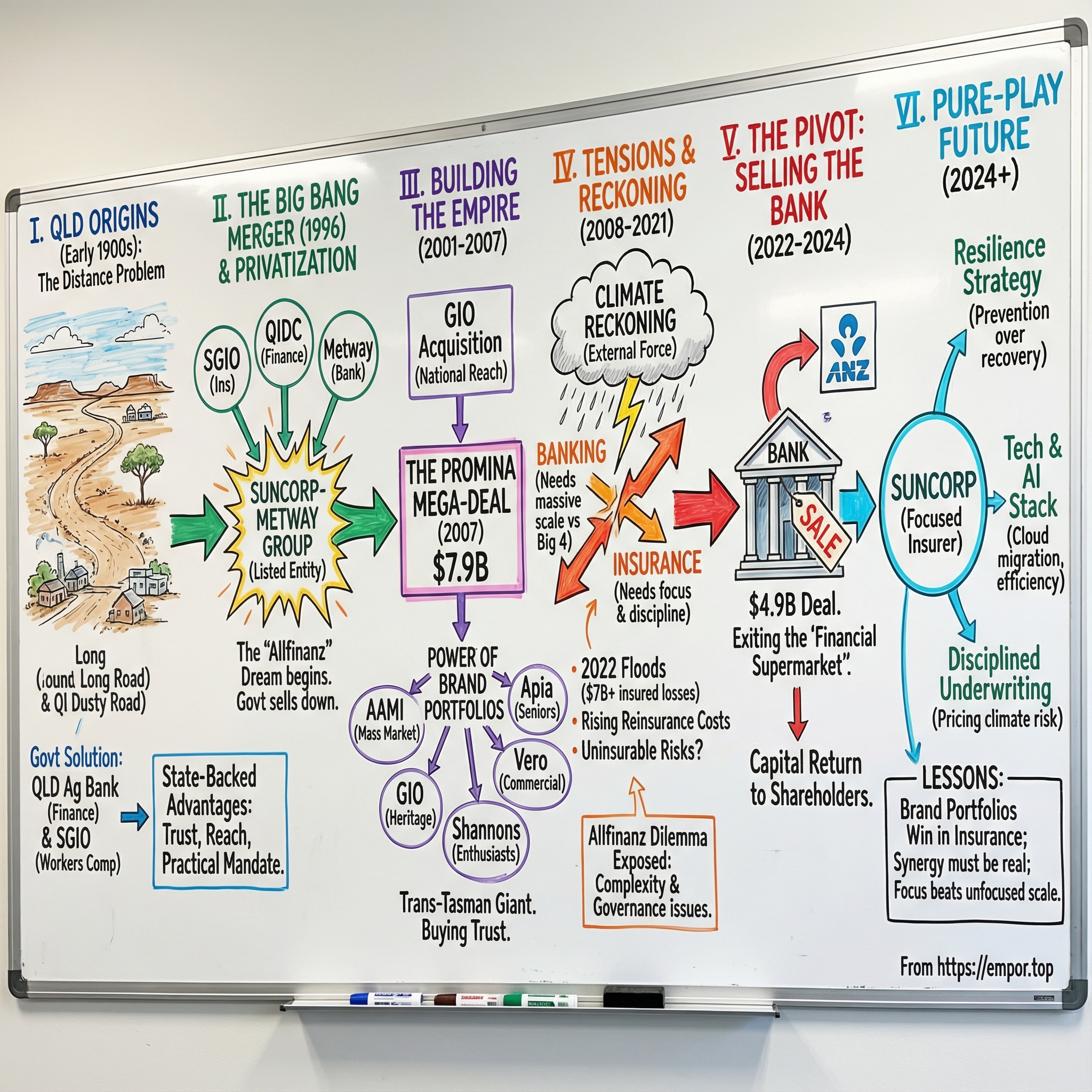

Picture the Queensland outback in the early 1900s. Vast cattle stations. Small towns separated by punishing distances. And a basic, very practical problem facing the government in Brisbane: if your citizens live days away from Sydney and Melbourne’s financial centres, how do they save, borrow, and protect what they’re building?

The institutions Queensland created to solve that problem didn’t just fill a gap. Over time, they compounded into something far bigger than anyone would’ve predicted: a Brisbane-headquartered group that today sits at the centre of Australian insurance.

That arc is what this story is about. How a state-linked set of financial and insurance entities—some of them, frankly, pretty unglamorous—turned into a Trans-Tasman insurance powerhouse with roots stretching back more than 120 years. And why, after spending decades trying to be both a bank and an insurer, Suncorp ultimately chose to pick a side.

That decision became official in July 2024, when Suncorp completed the sale of its banking business to ANZ. The handover didn’t end with the closing date: transitional business and technology services were set to unwind over the following years—most within two years, with the remainder no later than five. But strategically, the message was immediate. Suncorp was exiting the “all-in-one” financial supermarket model and recommitting to one job: insurance.

So this episode is driven by two questions—one historical, one urgent.

First: how did Suncorp’s state-backed origins create advantages that private competitors couldn’t easily replicate—distribution, trust, mandate, and time to build capability?

Second: why sell the bank at all? Why walk away from the “allfinanz” dream—the 1990s conviction that banking and insurance belonged together under one roof—especially when that model once seemed like the future?

Along the way, we’ll hit four themes that make Suncorp more than just an Australian corporate biography.

One is the classic transformation from government institution to privatised national champion—an arc that’s played out around the world, but rarely as cleanly as it did here.

Two is the allfinanz experiment itself: what looked like synergy on a PowerPoint slide, what it became in practice, and why Suncorp’s version ultimately didn’t deliver.

Three is climate risk—the defining external force bearing down on insurers everywhere, but especially in Australia, where catastrophe losses aren’t a tail event anymore. They’re starting to look like the baseline.

And four is brand architecture: the underappreciated superpower in consumer insurance, where trust is slow to earn, easy to lose, and often easiest to scale by owning multiple brands that each mean something specific to a specific customer.

Suncorp’s 2024 annual report put it this way: “While it is a new era for Suncorp as a pureplay insurer, our purpose to build futures and protect what matters for our people, customers and communities remains unchanged.” It’s a neat line—and also a tell. Because when you sell a bank, you don’t just change the P&L. You change the company’s identity.

And the timing couldn’t be more stark. Climate-driven disasters have been accelerating across Australia, and 2022 was a brutal proof point: more than 302,000 disaster-related claims from four declared insurance events, with insured losses totalling $7.26 billion. Roughly $6 billion of that came from the northern New South Wales and south-east Queensland floods—an event that became the costliest insured disaster in Australian history.

So the real question isn’t simply whether Suncorp made the right portfolio decision by focusing on insurance.

It’s whether the insurance business model itself can keep working as the climate reckoning intensifies—especially in the very communities Suncorp was originally built to serve.

II. The Queensland Origins: Government Insurance & Nation-Building (1902–1985)

To understand Suncorp, you have to start with Queensland itself: a state of huge distances, sprawling agricultural communities, and towns that could be hundreds of kilometres from the nearest serious financial institution. In the early 1900s, that created a very practical problem for the government in Brisbane. If private banks weren’t going to serve the bush at scale, who would?

Queensland’s answer was to build its own.

In 1902 it established the Queensland Agricultural Bank to support rural communities. Then, in 1916, it created the State Accident Insurance Office—later known as SGIO—to run workers’ compensation. Over time, SGIO expanded well beyond that original remit into broader life and general insurance.

Those two starting points—agricultural finance and workers’ comp—did more than create a pair of agencies. They shaped a culture. The Queensland Agricultural Bank (later renamed Agbank) wasn’t built as a profit-maximising enterprise; it was designed to keep the rural economy functioning when private capital either couldn’t or wouldn’t take the risk. SGIO, meanwhile, began as a government monopoly provider of workers’ compensation services. It stayed Queensland’s workers’ compensation authority until those functions moved to the Workers Compensation Board in 1978. Along the way, SGIO used the scale and stability of that core book to build a wider insurance portfolio—and generated surpluses that could be invested in commercial projects and government-selected initiatives.

That state-backed heritage matters because it created advantages that were hard for private competitors to copy: reach into regional Queensland, trust with communities that saw these institutions as part of the civic fabric, and decades of underwriting experience anchored in the real risks of Australian work and rural life.

The structure gradually became more corporate. In 1960, new legislation established SGIO as a separate corporation under state regulatory oversight. In 1971 it took another step toward corporate form by creating its own board of directors, and the workers’ compensation operations were put under a separate board. By the mid-1970s, as the insurance business tilted more commercial, SGIO shut down its building society operations.

The big identity shift came in 1985. Under new legislation, the organisation dropped the SGIO name in favour of Suncorp. Employees stopped being civil servants. Suncorp became an independent corporation—still government controlled, but no longer run as a conventional government department. By the mid-1990s, it had grown into an allfinanz-style group with assets of nearly $10 billion.

At the same time, another Queensland financial story was gathering momentum—this one in retail banking. Metway began life as the Metropolitan Permanent Building Society, founded in 1959. In the late 1980s, as building societies across Australia pushed into full banking, Metropolitan converted to bank status in 1988.

Metway listed publicly, then grew by acquiring rival banks and building societies. By the mid-1990s, it was the largest Queensland-based bank.

So by the time Australia’s financial deregulation really began reshaping the landscape, Queensland had quietly built a set of serious players: Suncorp with its expanding insurance portfolio, QIDC with commercial lending capability, and Metway with a retail banking footprint. But as banking and insurance started converging globally, the question for Queensland’s policymakers wasn’t whether these institutions were valuable. It was whether they could survive—and compete—separately.

The stage was set for a merger that would redefine Australian financial services.

III. The Big Bang: The 1996 Merger & Privatization

The merger that created modern Suncorp didn’t come from a slow-baked strategic plan. It came from a jolt of self-preservation.

A takeover attempt on Queensland’s Metway Bank set off alarms in Brisbane. The state government moved quickly, pushing through a three-way combination of Suncorp, QIDC, and Metway. Then, having created something big enough to stand on its own, the government began stepping away. What emerged was a much larger, consolidated Suncorp—now on a path to private ownership.

The mechanics tell you a lot about the ambition. On 1 December 1996, Suncorp Group was formally founded by combining the state-owned Suncorp and QIDC with the publicly listed Metway Bank. At launch, the Queensland Government was the dominant shareholder, holding about 68% of the new entity via shares and capital notes—effectively the “payment” for transferring Suncorp and QIDC into the merged group. The remaining 32% stayed with Metway’s existing shareholders. And crucially, the government made it clear from the start that this wasn’t meant to be a permanent holding.

The rationale was both economic and political. Officially, the merger was pitched as creating a more competitive institution “geared to meet the needs of the future.” Just as importantly, it created Australia’s fifth-largest listed financial services group—and kept the headquarters in Queensland, with the jobs, influence, and gravity that come with it.

Because this wasn’t only about scale. It was about sovereignty. Brisbane has long operated in Sydney’s financial shadow, and the Suncorp merger was a deliberate attempt to ensure Queensland had a credible, locally anchored champion instead of watching its major institutions get absorbed by southern rivals.

On paper, the combination also made sense. At the time, Suncorp and QIDC were wholly owned by the Queensland Government. Suncorp, already positioned as an all-finance group, had close to $10 billion in assets. QIDC managed about $3 billion. Metway was Queensland’s largest locally based bank, with operations reaching into New South Wales and Victoria, and roughly $7.1 billion in assets. Together, they created a group with real breadth: insurance, commercial lending, and retail banking under one roof.

But what happened next is what made this “big bang” feel like a true break from the past: the speed of privatisation.

In September 1997, the state announced a public issue of 100 million Exchanging Instalment Notes, with preference given to existing customers and shareholders of Suncorp, Metway, and QIDC. After the offer, the government’s effective interest fell to around 4%. The public paid $6.10 for the notes in two instalments, and they later exchanged for ordinary shares on 1 November 1999. Along the way, the shareholder base exploded—from about 36,000 to roughly 111,000.

In just over a year, Queensland went from owning roughly two-thirds of the business to holding a residual stake. That pace reflected both confidence in the merged entity and a strong appetite among Queenslanders to own a piece of what now looked like the state’s flagship financial institution.

The new company—Suncorp-Metway—quickly became one of the biggest insurance and finance groups in the country, ranked fifth nationally. By 1998, combined assets were over $22 billion. The government had started at 68%, and then rapidly did what it said it would: sell down.

Underneath all of this sat the strategic bet of the era. Put banking and insurance together, and you could cross-sell, share distribution, and smooth earnings across cycles. It was the “allfinanz” model that had caught on globally through the 1990s, popularised by big European financial conglomerates. Suncorp-Metway was Australia’s most ambitious swing at making it work.

Whether those synergies would show up in practice was still an open question. What wasn’t in doubt was that a major new force had arrived in Australian financial services—built from Queensland institutions, but now aiming well beyond Queensland.

IV. Building an Insurance Empire: GIO & Early Acquisitions (2001–2006)

For Suncorp-Metway, the late 1990s were a grind of integration. Three different organisations—public-sector insurance, state development finance, and a listed retail bank—had to be stitched into something that could actually run as one company. By the time the dust settled, Suncorp had finished its transformation from a Queensland government-controlled institution into a publicly listed financial services group.

Then came the harder question: what now?

By 1999, with the operational heavy lifting largely done, management had to decide where real growth would come from. Banking was competitive and scale-driven, and Suncorp’s footprint outside Queensland was still limited. Insurance, on the other hand, offered better economics—and a clearer path to expanding nationally if Suncorp could get distribution and brand power beyond its home state.

That set up the first big move. In 2001, Suncorp bought the general insurance operations of AMP, known as GIO General Ltd.

It was a step-change. The GIO deal turned Suncorp into the second-largest general insurer in Australia by annual premiums. But the more important impact wasn’t a league-table position—it was geography. GIO gave Suncorp meaningful presence in New South Wales and Victoria, markets it couldn’t credibly penetrate with a Queensland-centric brand alone.

What followed was one of the earliest signs that Suncorp’s leadership understood a core truth of consumer insurance: you don’t win by forcing one name onto everyone. You win by earning trust, and trust is slow.

So in 2002, Suncorp-Metway streamlined its branding in a way that looked simple, but was strategically sharp. It used “Suncorp” for Queensland-based insurance and national banking—where the name meant something—and kept “GIO” for insurance elsewhere—where that name already had history. Not one brand to rule them all, but the right brand in the right place.

At the same time, Suncorp kept building distribution through an especially powerful channel: motoring clubs. It acquired AMP’s 50% stake in the RACQ Insurance joint venture in 2002. Also in 2002, it purchased half of RAA Insurance from the RAA. And in 2004, it acquired Tasmania’s RACT Insurance.

These weren’t just bolt-ons. The motoring clubs had huge member bases and decades of built-in goodwill—exactly the kind of customer access that’s painfully expensive to replicate from scratch. Partnering with them let Suncorp scale faster than organic brand-building ever could.

But even as the portfolio grew, the limits of the strategy started to show. GIO wasn’t delivering the returns Suncorp wanted, and it was losing market share in New South Wales to more aggressive competitors—especially AAMI and IAG. The implication was uncomfortable: if Suncorp wanted to keep growing in national insurance, it likely wouldn’t be able to do it with GIO alone. It would need more brands, more reach, and more momentum—and that meant looking to acquisition again.

And when you looked around the market, one target stood out.

Promina—owner of AAMI—was sitting right there.

The stage was set for one of the biggest deals Australian insurance had ever seen.

V. The Promina Mega-Merger: Creating a Trans-Tasman Giant (2007)

The Promina deal changed everything.

After the GIO acquisition, Suncorp started gearing up for something much bigger: a takeover of Promina Group. By early 2007, the two companies had agreed to merge in a deal valued at A$7.9 billion—one of the largest transactions in Australia’s financial sector since the start of the new century. Promina itself was a relatively new listed company, spun out in 2003 from the UK insurer Royal and Sun Alliance. But what it owned in Australia and New Zealand was anything but new.

For Suncorp, the point wasn’t just getting larger. It was getting better—by buying the most valuable asset in consumer insurance: brands that already meant something to customers. The merger doubled Suncorp’s assets to nearly A$85 billion and instantly reshaped its competitive position.

To see why Suncorp paid up, you have to look at Promina’s portfolio. This wasn’t one brand. It was a set of distinct businesses wearing different uniforms, each built to win a specific kind of customer.

AAMI was the mass-market value brand—the one that had been taking share from GIO with sharper marketing and a clearer promise. Vero was the commercial insurer, distributed through brokers and aimed at businesses rather than households. Shannons served enthusiasts—classic car owners and motorcycle riders—people who wanted specialist coverage and community credibility, not just the cheapest premium. And Apia, originally the “Over 55 Pensioners Insurance Agency,” targeted seniors with products and messaging designed specifically for them.

Put together, it wasn’t just scale. It was segmentation. Instead of forcing one brand to stretch across every demographic and every price point, Suncorp could now run a multi-brand system where each name stayed true to its audience.

The combined group was expected to become the tenth-largest company in the ASX-100 by assets, with assets totalling $63 billion, and it would rank as the second-largest general insurer in Australia and New Zealand. Suncorp CEO John Mulcahy would lead the merged entity, with Promina CEO Mike Wilkins moving into a consultative role for six months.

Shareholder support was emphatic. Promina shareholders who voted approved the merger by an overwhelming margin. And with that, Suncorp inherited a lineage that stretched back much further than Promina’s 2003 listing—operations dating to 1833 in Australia and 1878 in New Zealand.

After the dust settled, Suncorp’s insurance stable now included AAMI, Bingle, Apia, Shannons, GIO, Terri Scheer, CIL, Vero, Asteron Life and Resilium in Australia, plus Vero, AA Insurance, and Asteron Life in New Zealand.

That New Zealand footprint mattered. Promina gave Suncorp real scale across the Tasman for the first time—true geographic diversification, different competitive dynamics, and a second market that could help smooth results over time.

On paper, the post-merger group looked enormous. In 2007, Suncorp reported assets of more than A$95 billion, more than 9 million customers, and more than 16,000 staff. It operated 232 retail and business banking outlets, mostly in Queensland. GIO had 34 agencies in New South Wales and Victoria. And Promina added another 157 branches and service centres into the mix.

But the deeper story was the architecture. With Promina, Suncorp could aim different brands at different needs: price-sensitive buyers (Bingle), mass-market value customers (AAMI), quality- and heritage-driven customers (GIO and Suncorp), seniors (Apia), enthusiasts (Shannons), landlords (Terri Scheer), and commercial clients (Vero). The group could sharpen each brand’s positioning without blurring the others.

For investors, the lesson is straightforward: in consumer insurance, trust compounds—and it compounds under a name. Building that kind of brand equity takes decades. Buying it is often faster, and sometimes it’s the only realistic path. The A$7.9 billion price tag was big, but the alternative—trying to manufacture AAMI-level brand power from scratch—may not have been achievable at any price.

By the end of 2007, Suncorp had become a fundamentally different company.

And yet the merger didn’t resolve the tension at the heart of the group. If anything, it amplified it: once you’re this large in insurance, does it still make sense to also try to win in banking?

VI. The Allfinanz Dilemma: Banking vs. Insurance Identity (2008–2020)

Suncorp barely had time to enjoy the Promina win before the world changed. The integration landed right on top of the Global Financial Crisis—exactly the moment when “financial supermarkets” everywhere got stress-tested. Suncorp made it through, but the period did what crises always do: it exposed the seams.

By 2009, the identity problem was no longer something you could paper over with org charts. On 19 April 2009, Suncorp announced it would rebrand its banking arm as Suncorp Bank. The intent was explicit: position Suncorp as a bank with an insurance arm, not an insurer with a banking division. And there was a practical reason, too. Outside Queensland—especially in Western Australia—Suncorp wasn’t known for banking. It was known for insurance. If the bank wanted to expand, it needed a banking-first identity.

But the rebrand was also a tell. It signalled that one logo couldn’t solve what was becoming a structural issue: banking and insurance look similar from far away—both are about risk, both are regulated—but they compete in fundamentally different ways.

Through the 2010s, that contrast became impossible to ignore. Australian banking was dominated by the Big Four—Commonwealth Bank, Westpac, NAB, and ANZ—who together controlled roughly 80% of the market. In that world, scale isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the product. It buys you cheaper funding, bigger technology budgets, broader distribution, and efficiency you can defend for decades. Suncorp Bank, as Australia’s sixth-largest bank, didn’t have that gravitational pull. It was big enough to matter, but not big enough to win the scale game on the same terms.

Insurance rewarded a different kind of advantage. The general insurance market was concentrated—four companies accounted for about three-quarters of it, led by IAG with 29% and Suncorp with 27%, followed by QBE at 10% and Allianz at 8%. In other words: Suncorp already sat inside the top tier. It didn’t need to be the biggest institution in the country to be efficient. It needed disciplined underwriting, sharp pricing, and brand management that kept each label clear in customers’ minds.

That mismatch—banking demanding ever-more scale, insurance rewarding focus and execution—pushed Suncorp into a slow, steady simplification.

Portfolio trimming started in the 2010s. Suncorp had built distribution through motoring-club joint ventures like RACQ and RAA, but in 2010 it chose to divest them. It had also entered a joint venture with RACT Insurance in Tasmania in 2007, and later sold its interest back to RACT in 2021. The direction was consistent: less sprawl, fewer moving parts.

The life insurance business moved the same way. Over time, the disposals started to read like an admission—quiet, incremental, but hard to misinterpret—that the allfinanz promise of seamless synergies wasn’t showing up in the real world.

Then came a different kind of problem: governance. In 2020, Suncorp admitted it had underpaid staff going back to 2014. In June 2023, Suncorp said remediation totalled $32 million affecting 15,800 staff.

The specifics were messy in the way payroll failures usually are—definitions, clauses, and processes that don’t line up across teams. Suncorp self-reported breaches to the Fair Work Ombudsman in 2020. It said more than 15,800 employees had been underpaid minimum wages between May 2014 and March 2022 because of inconsistent application of the term ‘Rostered Employee’ and the relevant clause in its Enterprise Agreements. The underpayments related to the insurance side of the business, and included entitlements like overtime, shift loadings, weekend penalties, annual leave loading, public holiday loadings, minimum rates of pay, long service leave, redundancy, payment in lieu of notice, and meal allowances.

CEO Steve Johnston put it plainly: “As a Suncorp employee of long standing I am incredibly disappointed that we have let our people down – there is no excuse and we need to get this right.”

Even with self-reporting and remediation, the episode highlighted what complexity can hide. Different enterprise agreements. Different systems. Different operating rhythms. In a conglomerate, those inconsistencies don’t always show up as dramatic failures—they show up as small errors that persist for years.

By 2020, the strategic logic that had justified keeping banking and insurance together had faded. The bank wasn’t achieving the national scale it needed, while the insurance business—larger, stronger, and increasingly exposed to climate-driven volatility—was demanding sharper focus. Suncorp had reached the point where “allfinanz” wasn’t a growth story anymore. It was a trade-off.

And that set up what came next: a fundamental strategic review of whether the group should stay together at all.

VII. The Climate Reckoning: Natural Disasters & the Insurance Business (2011–Present)

If the allfinanz tension was Suncorp’s internal strategic problem, climate change is the external force that’s rewriting the rules for every insurer in Australia. This isn’t a “bad year” problem. It’s a “different business” problem.

The price signal has been loud. Between 2022 and 2023, average home insurance premiums in Australia rose 14%, the biggest jump in a decade. And 2022 was the year that made the shift impossible to ignore: major floods across eastern Australia pushed insured losses to a record around $7 billion—almost double prior records. Even more unsettling, since 2013, each year’s insured losses have exceeded the combined losses of the five years from 2000 to 2004. The McKell Institute modelled where this heads if the trend persists: direct natural disaster costs potentially reaching $35 billion per year by mid-century—more than $2,500 per household per year on average.

The 2022 floods were the psychological turning point. They became the costliest insured event in Australian history and, according to global reinsurer Munich Re, the second-costliest insured event in the world in 2022.

Inside Suncorp, the new reality showed up in a way that’s easy to understand and hard to forget. Executive General Manager for Brand and Customer Experience Mim Haysom described what happened in Lismore, in northern New South Wales: a “one in 100 years” weather event—three times in the past five years. “So that is the severity and the frequency that we’re seeing coming through in weather events,” Haysom said.

As the physical risk has intensified, the regulatory system has started building tools to measure it. In July 2023, APRA commenced the Insurance Climate Vulnerability Assessment on behalf of the Council of Financial Regulators. The Insurance CVA looks at how the affordability of general insurance could change between now and 2050 under two future climate scenarios, testing both physical risk and transition risk. It followed APRA’s 2022 Banking Climate Vulnerability Assessment, which focused on climate impacts on bank credit risk.

The insurance version was developed with the five largest general insurers in Australia—IAG, Suncorp, Allianz, QBE, and Hollard—together covering about 80% of the market by gross written premium. In other words: this wasn’t a theoretical exercise. It was the core of the industry mapping the boundaries of what remains insurable.

Then there’s the second-order effect that hits insurers directly: reinsurance. As losses have risen, reinsurers have pushed back—raising prices, tightening terms, and in some cases reducing how much capacity they’re willing to offer. The result was global reinsurance costs reaching 20-year highs, with Australian insurers facing cost increases of up to 30%.

That cost pressure quickly turns into an affordability crisis—especially in the places most exposed to cyclones, floods, and storm surge. In northern Western Australia, home and contents insurance averages $4,395 per year—more than double the $1,779 average in the southern two-thirds of the country. It’s also higher than the $3,069 the average household spends on electricity in a year. Average premiums in the Northern Territory are $2,922, and in North Queensland $2,918—around 60% higher than the rest of the country.

And when premiums get that high, the risk isn’t just that customers grumble and churn. The risk is that the product stops working at all. The Australian Climate Council has estimated that by 2030, 1 in 25 homes and commercial buildings could become effectively uninsurable. Its report, Uninsurable Nation: Australia’s Most Climate-Vulnerable Places, projects 520,940 buildings will be deemed “high risk,” with annual damage costs equivalent to 1% or more of replacement cost. River flooding is identified as the biggest risk to homes.

Suncorp’s response has moved on two tracks at once: better pricing and better prevention.

On the pricing side, the company has invested in climate risk modelling. A Suncorp team developed a model that uses data, advanced analytics, and artificial intelligence to translate weather events into an insurance context—so Suncorp can adjust natural hazard pricing as climate risks evolve across Australia and New Zealand, and strengthen climate-informed underwriting and risk management.

But the bigger shift has been strategic: from only managing the aftermath to trying to change what happens before the next event. “We saw a really big opportunity to flip our strategy on its head and to go absolutely against the industry norm,” Haysom said. “We decided not to talk about what we do after an event and start focusing on what we could do before these events come.”

That posture shows up in Suncorp’s long-running advocacy for a four-point action plan to ease affordability pressure in high-risk regions, and its push for an industry-wide approach through the Hazard Insurance Partnership and direct engagement with government agencies.

And it shows up in the consumer-facing expression of the idea: the “Haven” platform. As Haysom framed it, “Suncorp Haven” is meant to take resilience learnings to every home in Australia—a digital platform that gives homeowners a tailored report on the threats their home faces, and the specific steps they can take to reduce risk.

For investors, this is where climate risk becomes both the defining threat and the defining opportunity. Insurers that can price risk accurately, secure reinsurance on workable terms, and help drive real resilience investment—while maintaining customer trust—can emerge stronger. The ones that can’t don’t just face a bad underwriting cycle. They face a shrinking map of insurable Australia.

VIII. The Strategic Pivot: Selling the Bank to ANZ (2022–2024)

By the time Suncorp got to 2022, the direction of travel was hard to deny. Years of internal debate about “what are we, really?” had turned into a more concrete question: should the bank and the insurer still live together at all?

On 18 July 2022—in the group’s 120th year—Suncorp answered it. It announced it had signed a share sale and purchase agreement with ANZ to sell Suncorp Bank.

The price tag made it a landmark: A$4.9 billion, the biggest Australian banking deal since Westpac bought St George in 2008. But closing a deal this large in a heavily regulated, politically sensitive sector was never going to be a clean sprint to the finish line.

The sticking point was competition. Australia’s banking market is already concentrated, and in August 2023 the ACCC decided not to authorise the acquisition. ANZ and Suncorp pushed back, applying to the Australian Competition Tribunal for a review.

On 20 February 2024, the Tribunal overturned the ACCC’s decision and authorised the deal. The reasoning mattered: the Tribunal effectively concluded that Suncorp Bank wasn’t a particularly strong competitive constraint on the Big Four, so the acquisition wouldn’t materially lessen competition.

Even then, it wasn’t just one regulator. Completion required a sequence of approvals and legislative changes, including Federal Treasurer approval on 28 June 2024 and Queensland legislation amending the Metway Merger Act. That last piece—the Queensland State Financial Institutions and Metway Merger Amendment Act—was the final box to tick. With it proclaimed, ANZ could proceed to completion.

The deal closed on 31 July 2024.

Queensland’s support came with strings attached. Part of the bargain was a set of commitments tied to jobs, presence, and capability in the state. As Suncorp CEO Steve Johnston put it: “As a pureplay insurer, Suncorp Group can now look forward to investing in our business and delivering greater value for our customers and communities as well as our shareholders. We are also pleased to be able to get on with the important job of delivering on the commitments agreed with the Queensland government as part of this transaction, including investment in a disaster response centre of excellence out of our Brisbane headquarters, and the establishment of a regional hub in Townsville set to employ around 120 people.”

For shareholders, the logic was simple: focus, plus cash. Suncorp said the transaction would generate A$4.1 billion in net proceeds, and it planned to return the bulk of that to shareholders—A$3.8 billion—through buybacks and a special dividend. In total, the return was framed as about $3.00 per share.

And the timing lined up with strong reported results. For the half-year to 31 December 2024, Suncorp reported NPAT of A$1.1 billion and gross written premium of A$7.5 billion, up nearly 9%. That profit number included a one-off gain of A$252 million from the sale.

But the real story wasn’t the accounting bump. It was what the sale allowed Suncorp to become.

Johnston described it as a reset into a dedicated Trans-Tasman insurance company at a moment when the value of insurance—and the need to keep investing in a healthy private insurance market—had “never been greater.” And, crucially, he tied it to the forces bearing down on the industry: “Our ability to meet the rapidly evolving needs of insurance customers and address increasingly complex challenges such as climate change and affordability will be significantly strengthened through dedicated investment as a pureplay insurance company.”

That was the end of the allfinanz experiment in practice, not just in theory. After nearly three decades of trying to make banking and insurance work under one roof, Suncorp was choosing one identity. Not the small, state-backed insurer Queensland created in 1916—but a much larger, more complex version of the same core idea: protect what matters, and get very, very good at it.

IX. The Pure-Play Insurer: Digital Transformation & Future Strategy (2024–2027)

With the bank gone, Suncorp’s next chapter isn’t being written in branch networks or credit growth. It’s being written in technology—because if insurance is going to stay profitable in a world of rising volatility, it has to get faster, smarter, and simpler to run.

The biggest foundational move is infrastructure. Suncorp has migrated 90 per cent of its technology workloads out of data centres and into public cloud environments—one of the first financial services organisations in Australia to hit that mark. Executive General Manager of Technology Infrastructure Charles Pizzato said the target was set in mid-2022 with a clear intention: leaning heavily on public cloud would “materially simplify” Suncorp’s adoption of next-generation capabilities, including AI. He described finishing the shift from on-premises data centres to a secure, scalable hybrid multi-cloud environment as a major undertaking—one that took just over 18 months.

That cloud migration wasn’t a vanity milestone. It was meant to clear the path for a much larger rebuild. Suncorp recently completed a five-year overhaul of its legacy data platforms, consolidating into a cohesive cloud-based ecosystem built to support advanced AI use cases—and to enable more consistent, data-driven decision-making across the business.

From there, the strategy starts to sound like a company trying to industrialise AI, not just experiment with it.

A central pillar is its five-year partnership with Microsoft, aimed at accelerating the use of artificial intelligence and public cloud across the insurer’s operations. The idea is straightforward: extend an existing relationship, integrate AI at scale faster, and improve the experience Suncorp delivers not only to customers, but also to employees doing the work day to day. And because Suncorp already did the heavy lift of getting most workloads into public cloud, it positioned itself to take advantage of Microsoft’s latest AI capabilities as they arrive.

The pace of experimentation reflects that ambition. Suncorp is exploring 120 internal genAI use cases, with 20 targeted for deployment by June 2025. “Having established the right foundations through cloud migration, engineering excellence, digitisation and automation, we are now working together to safely deploy genAI at scale and transform our end-to-end operations,” Bennett said.

Some of these projects are designed to be invisible to customers but hugely meaningful operationally. One example is Smart Knowledge, which analyses thousands of internal articles and surfaces the right information to contact centre teams—so customer support can be faster and more accurate without relying purely on institutional memory.

This isn’t being treated as a side project. Suncorp is investing $560 million in technology by FY27 to improve operational efficiency, including AI tools it expects could reduce claims handling costs by an estimated 15% over two years.

Underneath the AI story, there’s also the less flashy but more fundamental work: rebuilding the core insurance systems. As part of its “digital insurer” policy transformation program, Suncorp has partnered with Duck Creek Technologies. Duck Creek will deliver cloud-native, low-code core insurance delivery solutions, replacing multiple on-premises legacy systems. The multi-year agreement covering Duck Creek policy, billing, and Clarity solutions is intended to underpin Suncorp’s next era of technology modernisation and process simplification—and to support its customer-outcome and value-focused strategies.

Financially, Suncorp has pointed to early momentum in the insurance book. It reported consumer insurance gross written premium growth of 10.2%. In motor, units rose 1.4% and average written premium increased 8.9%. Home gross written premium grew 10.2%, driven by average written premium growth—reflecting price rises tied to higher natural hazard allowances and ongoing claims inflation. Net incurred claims in consumer insurance rose 4.2% to $2.55 billion, reflecting a larger portfolio and claims inflation in home. Consumer insurance profit after tax more than doubled to $423 million.

Across the Tasman, the New Zealand business has also been part of the “pure-play, simpler portfolio” direction. For the six months ending 31 December 2024, Suncorp New Zealand reported profit after tax of $248 million and general insurance gross written premium of $1,495 million, up 6% on the prior comparable period. CEO Jimmy Higgins said the result was supported by a benign natural hazard claims environment, easing claims inflation pressures, and solid investment income returns. “Over the last six months we’ve grown our customer base and paid out $700 million in claims,” he said.

And in line with the simplification theme, on 31 January 2025 the company completed the sale of its New Zealand life business to Resolution Life NOHC for NZ$410 million, plus excess capital—further narrowing the group’s focus to general insurance.

That focus has been overseen by CEO Steve Johnston, who was appointed Suncorp Group Chief Executive Officer and Managing Director in September 2019. Johnston joined Suncorp in 2006 and held a range of executive roles; immediately prior to becoming CEO, he served as Group CFO, responsible for financial reporting and management, legal and company secretariat, taxation, investor relations, corporate affairs, and sustainability. Before Suncorp, he also worked as a journalist and held senior roles in the Queensland Government—a career path that mirrors Suncorp’s own blend of public-sector roots and private-sector complexity.

Looking forward, Suncorp’s three-year strategic plan puts technology at the centre: continued platform modernisation and “AI-enabled operational transformation” as key deliverables. Technology received top billing at the FY24 annual results briefing, and Johnston framed it as the second half of a story many observers missed. “The completion of the bank’s sale brings to an end a program of portfolio simplification,” he said. “Suncorp has emerged as a far simpler, easier to understand pure-play trans-Tasman general insurance company.” But, he added, “What’s less well understood is the program of platform modernisation that we had been executing alongside the sale of the bank.”

In other words: the separation wasn’t just a transaction. It was an operating redesign—meant to leave Suncorp not only more focused, but structurally better equipped for what modern insurance is becoming.

X. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

Suncorp’s 120-year arc isn’t just a Queensland story, or even an insurance story. It’s a case study in how financial institutions actually build advantage—and what happens when the logic of one business collides with the logic of another.

The Power of Brand Portfolios in Insurance

In banking, most customers pick one primary institution and live with it. In insurance, people shop differently. They respond to a brand that feels like it was built for them—price-led, service-led, specialist, mainstream, senior-focused, whatever the identity is.

That’s why Promina mattered so much. The acquisition wasn’t mainly a land grab for scale. It was a brand grab: AAMI, Apia, Shannons, and Vero—each with its own positioning, distribution muscle, and earned trust—assets that take decades to build from scratch.

The bigger point: in insurance, trust compounds slowly and breaks quickly. A single ugly claims experience can damage a brand far faster than marketing can repair it. So paying up to buy established brands can be rational value creation, not empire-building. Done well, a portfolio of distinct brands lets you cover the market in a way no single “one-size-fits-all” label ever could.

The Allfinanz Experiment and Its Limits

The 1990s allfinanz idea sounded irresistible: combine banking and insurance, cross-sell across the same customer base, share distribution, and smooth earnings across cycles.

In practice, Suncorp ran into something more basic: these are different games with different rules. Banking is brutally scale-driven and dominated by giants. Insurance, especially consumer insurance, is more about underwriting discipline, pricing, claims performance, and managing a set of brands that customers actually choose.

The lesson isn’t that conglomerates never work. It’s that synergy has to be real and repeatable—not just plausible on a slide. In Suncorp’s case, decades of effort ultimately pointed to a simpler conclusion: focused excellence beat unfocused scale.

State-Backed Origins as Competitive Advantage

Suncorp’s government roots weren’t just historical trivia. They created compounding advantages private competitors couldn’t easily reproduce: reach into regional Queensland, deep trust with communities, and decades of experience underwriting the very specific risks of Australian work and rural life.

Privatisation didn’t erase that. It embedded it. Over time, the state-backed beginnings turned into brand equity, customer relationships, and institutional know-how—exactly the intangible assets that matter most in a product built on promises.

Climate Risk as Strategic Imperative

For Australian insurers, climate change isn’t a future scenario. It’s already reshaping the unit economics of the business—through higher claims volatility, tougher reinsurance, and an affordability squeeze that can shrink the customer base.

One of the most important strategic shifts in the story is the pivot from a “recovery” posture—what insurers do after disaster—to a “resilience” posture—what they can influence before the next one hits. That’s not a CSR initiative. It’s a redefinition of the value proposition.

The insurers that win will be the ones that can price risk credibly, secure reinsurance on workable terms, push for real mitigation investment, and still keep customers onside as premiums rise. The ones that can’t won’t just have weaker years. They risk finding parts of the map where the product stops working.

Regional Champions vs. National Scale

Suncorp’s Queensland identity was both fuel and friction. It helped build a loyal base and a powerful home-market franchise. But in banking, it left Suncorp in a hard place: too small to match Big Four efficiency, too big to ignore, and always fighting gravity outside its core stronghold.

Insurance was different. A multi-brand strategy made national expansion more achievable from a regional base. Instead of forcing one Queensland-centric brand to stretch across the country, Suncorp could meet customers where they already were.

The broader lesson is to be honest about what kind of advantage an industry rewards. Some businesses reward sheer scale. Others reward differentiated positioning and focus. The danger zone is the middle—big enough to be complex, not big enough to dominate.

XI. Analysis: Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-LOW

Australian general insurance is not an easy market to crash. Regulation alone is a moat: APRA licensing, ongoing supervision, and meaningful capital requirements make “move fast and break things” a non-starter. Then there’s the slower, stickier barrier—trust. In insurance, the product is a promise that only gets tested on the worst day of someone’s life. It takes decades to build a reputation that people are willing to bet their house on.

Scale also matters because of reinsurance. Bigger books generally mean better diversification and better negotiating leverage.

And yet: the walls aren’t unscalable. Digital distribution has lowered the cost of acquiring customers, and insurtechs and digital-first brands have proven they can get traction, especially at the price-sensitive end of the market. Suncorp’s own Bingle—a stripped-back, online-only insurer—exists because the industry saw this coming. As one Macquarie report put it, “the original challenger brands of Youi, Hollard, and Auto + General have grown from no footprint 15 years ago to about 10% of market share.”

The takeaway is that entry is still hard—but it’s no longer impossible. The new playbook isn’t building a branch network or an agent force; it’s buying attention online, competing on price and simplicity, and trying to earn trust one claim at a time.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Reinsurers): HIGH

Reinsurance is the insurance that insurers buy so a single catastrophe doesn’t blow a hole in the balance sheet. In a country like Australia—where flood, cyclone, bushfire, and hail can all hit hard—reinsurance isn’t optional. It’s fundamental to capital management and regulatory compliance.

That gives reinsurers real leverage, especially because the global reinsurance market is concentrated in a relatively small group of players like Munich Re and Swiss Re. And as climate losses have increased, the negotiating dynamic has shifted further in their favour. Reinsurance costs have climbed to 20-year highs, with Australian insurers facing increases of up to 30%. It’s not the kind of input cost you can politely decline; the insurer either pays it, restructures its program, or takes on more risk itself.

Australia’s cyclone reinsurance pool is one attempt to reduce that supplier power for cyclone-exposed regions. But outside that slice of the risk map, commercial reinsurers still hold the whip hand—particularly as their models adjust to events that keep exceeding “once in a century” expectations.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

Insurance buyers have more power than they used to. Comparison sites and online quotes make switching easier, and rising premiums push people to shop around. But this isn’t like switching phone plans. People worry about claims outcomes, service quality, and whether an insurer will actually come through when it counts. That kind of anxiety creates stickiness—especially for established brands.

Some products also reduce buyer power structurally. Compulsory third party (CTP) motor insurance is a good example: the customer has to buy something, even if they can choose the provider.

The sharper pressure point is affordability. In 2023, more than one million Australian households experienced insurance affordability stress—defined as paying more than four weeks of gross household income on annual home insurance premiums. When insurance crosses that threshold, customers don’t always “switch.” Often they reduce cover, raise excesses, or drop it entirely. That’s not buyer power in the traditional sense—it’s demand destruction.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE

For most households, there isn’t a clean substitute for home and motor insurance. Mortgages typically require home insurance. Motor vehicles require CTP. Businesses need cover to operate.

Government schemes exist in adjacent areas—like Medicare and workers’ compensation—but they don’t replace property and motor coverage for individuals.

The real substitute threat isn’t another product. It’s opting out. When premiums rise far enough, the “substitute” becomes no insurance at all. That’s less a competitive dynamic than a social and political one, because widespread underinsurance turns private risk into public cost after disasters.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a concentrated market with constant jostling. Four players account for roughly three-quarters of Australian general insurance: IAG at 29%, Suncorp at 27%, QBE at 10%, and Allianz at 8%.

The structure creates duopoly-style tension at the top. IAG and Suncorp run large brand portfolios that often compete in the same categories and channels, and both fight to retain customers as premiums rise and claims experiences get scrutinised harder.

At the same time, the edges are getting more contested. Research cited in the Macquarie commentary shows the top five insurers’ combined share has fallen from about 85% fifteen years ago to around 72% today. And IAG and Suncorp’s combined share in home and motor has slipped from about 61% in 2009 to 57%.

This isn’t a race to the bottom on price—climate-driven costs make that unsustainable. It’s a contest over distribution, customer experience, claims handling, and brand credibility. When prices are rising everywhere, “who do you trust?” becomes the battleground.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Framework

Scale Economies: MODERATE

Scale helps in insurance: it spreads fixed costs, improves purchasing power, and can strengthen reinsurance negotiations. With more than a quarter of the general insurance market, Suncorp has meaningful scale benefits.

But unlike banking, scale doesn’t automatically create an unassailable fortress. Beyond a point, the gains diminish. Suncorp is big enough to be efficient—and big enough to matter—but not so big that competitors can’t match its economics.

Network Effects: LIMITED

There aren’t classic network effects here; my home policy doesn’t get better because you also buy one.

Where insurance can behave a little like a network is distribution. Partnerships with mortgage brokers, car dealers, and other intermediaries can create repeatable channels that are hard to dislodge once embedded. It’s not a product network effect—but it can be a distribution flywheel.

Counter-Positioning: PRESENT

Suncorp’s emphasis on resilience and prevention is a form of counter-positioning against the traditional “we’ll be there after the disaster” posture. As Mim Haysom put it: “We decided not to talk about what we do after an event and start focusing on what we could do before these events come.”

If executed well, that stance can be hard for others to copy quickly, because it requires investment, different messaging, and in some cases different economics. A pure claims-and-premiums competitor may find it difficult to justify spending on prevention that reduces claims volume.

Switching Costs: MODERATE

Switching insurance isn’t as painful as switching banks, but it isn’t frictionless either. Customers worry about coverage differences, claims treatment, and the uncertainty of how a new insurer behaves under stress. Policy history and relationships also matter, and multi-policy bundling increases the cost—psychological and practical—of moving.

Brand Power: HIGH

This is Suncorp’s clearest power. AAMI, Apia, Shannons, GIO, Suncorp—each carries a specific meaning to a specific customer group. That brand portfolio is hard to replicate because it’s built over decades, not quarters.

As one blunt observation puts it: “Australians love their brands. We are the land of the oligopoly, so to get another brand in the psyche of the Australian mindset is very expensive from a marketing point of view.” In other words, buying trust is slow and costly. Suncorp already owns a lot of it.

Cornered Resource: LIMITED

There’s no obvious cornered resource like a patent or a unique natural asset. But Suncorp’s Queensland heritage, and longstanding distribution relationships in certain markets, function like soft cornered resources—advantages that aren’t exclusive by law, but are hard to reproduce in practice.

Process Power: DEVELOPING

Suncorp is trying to build process power through technology: cloud migration, AI-enabled operations, and claims automation. The company has earmarked $560 million in technology investment by FY27, and it expects AI initiatives could reduce claims handling costs by an estimated 15% over two years.

This is still “developing” because the hard part isn’t announcing the tools—it’s converting them into durable operating advantages that persist after competitors adopt similar platforms.

Key Performance Indicators to Track

For investors watching Suncorp’s next chapter as a pure-play insurer, three indicators matter most:

1. Underlying Insurance Trading Ratio (UITR)

UITR is the clearest read on the quality of the insurance business itself—profitability from underwriting, not from market returns or one-off items. A UITR in the 10–12% range signals disciplined pricing and claims management. Sustained compression below 10% is a warning sign: either competition is biting, costs are rising faster than expected, or risk is being underpriced.

2. Natural Hazard Experience vs. Allowance

Every year, Suncorp sets a natural hazard allowance—its internal “budget” for weather-related claims. Actual experience above or below that allowance can swing profitability.

The trend matters more than the single year. If allowances keep rising and losses keep beating them anyway, that’s a signal climate risk is outrunning pricing and modelling. If allowances rise and experience stabilises, it suggests the company is catching up to the new baseline.

3. Gross Written Premium (GWP) Growth by Segment

GWP growth is the scoreboard for both pricing power and share. Growth driven mostly by price increases can be good—but it also raises the risk of customers dropping cover. Growth driven by unit growth implies competitive strength and distribution momentum. Segment-level performance—consumer vs commercial, Australia vs New Zealand—shows where Suncorp’s positioning is strongest and where it’s most exposed.

The Investment Case

Bull Case:

The pure-play structure lets management allocate capital and attention to one job: insurance execution. Suncorp’s brand portfolio is a real moat that digital challengers struggle to recreate. The technology program improves claims efficiency and service quality, turning cost pressure into operational advantage. Climate change increases the value of insurance and supports pricing power for disciplined underwriters. And the bank-sale capital return creates near-term shareholder value while leaving a simpler story behind.

Bear Case:

Climate risk in Australia and New Zealand concentrates catastrophic exposure in a way that can’t be fully diversified away—and in extreme scenarios, not fully reinsured. Premium increases in high-risk regions could trigger political intervention: price caps, mandated cover terms, or expansion of public insurance alternatives. Challenger brands keep picking off price-sensitive customers. And the technology spend fails to translate into meaningful efficiency gains, consuming capital without changing the competitive equation.

The Balanced View:

Suncorp looks well-positioned—but not invulnerable—in an industry that is attractive structurally and brutal cyclically, with climate acting less like a cycle and more like a regime shift. The pivot to pure-play insurance is coherent capital allocation. The brand portfolio is genuine differentiation. The technology program is essential—though more like table stakes than an automatic moat.

The central uncertainty is climate risk: not whether it matters—it already does—but whether it stays manageable or becomes existential.

Suncorp’s capital position remains a key anchor. Regulatory ratios have stayed above internal targets, giving it the balance sheet strength to absorb heavier claims periods without immediately threatening dividends or strategic flexibility. But investors are also asking the next, harder question: if hazard events keep repeating, do guidance ranges and return expectations need a structural reset?

That’s the tension at the heart of the modern Suncorp story. A Queensland government workers’ compensation office became a Trans-Tasman insurance powerhouse through trust, scale, and smart brand building. It experimented with allfinanz, then walked it back. Now it’s placing a focused bet on being excellent at insurance—right as the map of insurable risk is shifting beneath the industry.

What happens next depends on forces that no management team fully controls: the trajectory of climate change, the political response to affordability stress, and how quickly digital competition reshapes customer acquisition.

Suncorp enters that future with strong brands, solid capital, and a clearer identity than it’s had in decades. Whether that’s enough is the question that will define the next era.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music