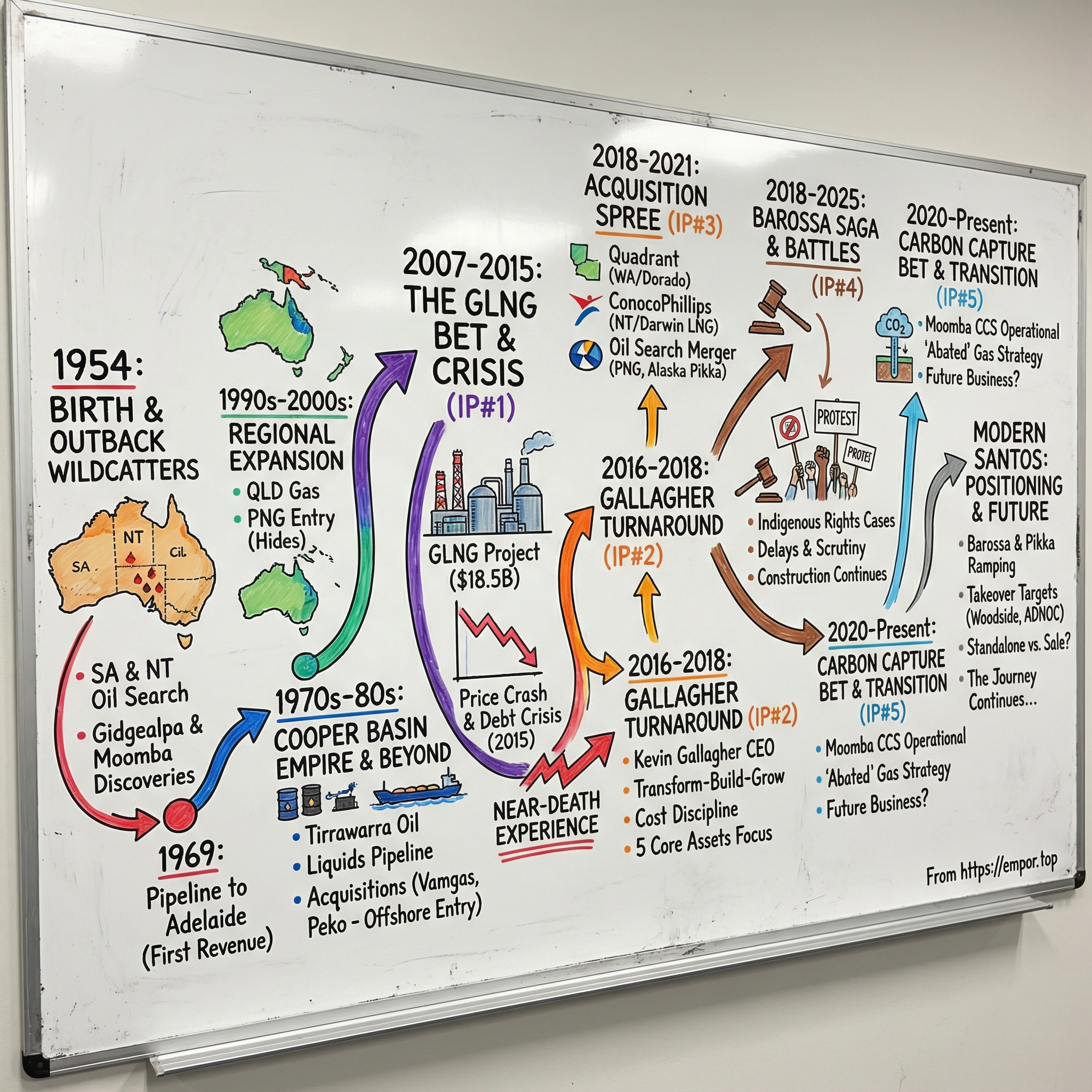

Santos Ltd: From Outback Wildcatters to Asia-Pacific Energy Champion

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture the red dust of the South Australian outback in 1954. A handful of geologists and Adelaide business figures lean over a map of Australia’s interior, tracing lines across blank-looking desert that most people wrote off as worthless scrub. They saw something else: the chance that, under the sand dunes and spinifex, there might be oil and gas.

They gave their venture a name that sounded almost mythic, but was really an acronym: Santos, short for South Australia Northern Territory Oil Search. It captured both the geography and the attitude. This was a wildcat bet.

Santos was incorporated on 18 March 1954. It grew out of the vision of geologist Robert F. Loxton and prominent Adelaide businessman John Bonython, who believed Australia’s interior, especially the Cooper Basin, could hold serious reserves. At the time, that belief was closer to conviction than consensus.

Jump ahead seven decades and the company that began with maps, hunches, and optimism had become the country’s biggest supplier of natural gas. Santos’s footprint now stretches from the Cooper Basin’s sunbaked plains to Papua New Guinea, from the Timor Sea to the North Slope of Alaska. Along the way it built and bought its way into LNG plants, offshore platforms, and, more recently, carbon capture infrastructure.

A major chapter in that modern story is Kevin Gallagher, who joined as Managing Director and CEO in 2016 and led a transformation that repositioned the company for a very different era. Under his leadership, Santos became Australia’s second-largest independent producer of natural gas and liquids, built around a focused strategy: five core, long-life producing gas assets across Australia, Papua New Guinea, and Timor-Leste.

So here’s the question that powers this deep dive: how did a 1954 oil-search venture named after two Australian territories turn into a regional energy champion—one that has battled climate activists, fought high-profile Indigenous rights cases, competed with global supermajors, and still tried to sell itself as part of the transition to lower-carbon energy?

The Santos story is one of audacity, near-death experiences, and reinvention. It starts with post-war wildcatting and the discovery of Australia’s most important onshore gas province. It swings through the ambitious, debt-heavy GLNG mega-project and into the 2015 crisis that nearly broke the company. Then comes the Gallagher turnaround—from survival mode back to growth—followed by a run of deals that remade Santos’s portfolio.

Today, Santos is bringing major developments like Barossa LNG and Pikka in Alaska closer to reality, while also operating one of the world’s largest carbon capture projects at Moomba. It’s a company at a critical juncture.

This is the Santos story.

II. Australia's Oil Search Dream & The Birth of Santos (1954–1969)

Post-war Australia had a problem that felt uncomfortably strategic. For all its land and minerals, it still relied heavily on imported petroleum. Anyone who remembered World War II understood the risk: supply lines can be cut, and when they are, everything else gets harder fast. So across the country, a new kind of optimism took hold. If Australia wanted energy security, it would have to find it at home.

That belief pulled explorers toward the interior, and eventually toward a stretch of country that looked like the worst possible place to build anything: the Cooper Basin.

Exploration in the Cooper Basin began in 1962. The basin would go on to become Australia’s most important onshore oil and gas province, with the key hydrocarbon-bearing layers more than a kilometre below the surface—out of sight, and for a long time, out of reach.

And above ground, it was brutal. The Cooper is deep outback: punishing heat, sudden floods that could turn dirt tracks into rivers, and distances so vast the nearest “town” could be hundreds of kilometres away. Crews lived rough in canvas camps. Equipment had to be hauled in across country that barely qualified as roads. Every well was an expedition.

By the early 1960s, Santos and Delhi had enough geological evidence to focus their efforts in the basin. Then, in 1963, came the first real validation: Gidgealpa 2, a commercially viable natural gas discovery, flowing at about 3.2 million cubic feet per day. It wasn’t just a find. It was proof that the theory under the sand was real.

But the discovery that truly changed Santos’s trajectory was Moomba. Moomba was identified in the mid-1960s, and its scale gave Santos something even more valuable than gas: confidence. Confidence to do the unthinkable for a company that was still more promise than profit—build a pipeline to market.

This is where Santos stopped being only an explorer and started becoming an infrastructure company. To turn a desert discovery into a business, it needed steel in the ground: a pipeline running roughly 800 kilometres from Moomba to Adelaide, cutting across some of the toughest terrain on the continent. It was an enormous commitment of capital and credibility. For Santos, it was a bet-the-company moment.

In 1966, Santos signed a supply contract with the South Australian Gas Company, and construction began. Three years later, in 1969, the pipeline was complete and Santos started selling gas—finally, a first customer and real revenue.

By November 1969, natural gas from Moomba was flowing into Adelaide homes. In just fifteen years, Santos had gone from a speculative oil-search venture to a critical piece of South Australia’s energy system. It had taken a blank patch of map, found something valuable underneath it, and then built the expensive, unglamorous link that mattered most: the route to market.

That combination—patience through failure, conviction in the geology, and the willingness to place huge bets when the moment arrived—became Santos’s signature. It would need all of it again in the decades to come.

III. Building the Cooper Basin Empire (1970s–1980s)

With gas finally flowing to Adelaide, Santos shifted from frontier explorer to something much rarer in Australia: a company that could find hydrocarbons, produce them, and reliably deliver them to customers. But there was a bigger prize still sitting on the table.

Was the Cooper Basin only a gas story? Or was there oil too?

For years, the prevailing view was simple: the Cooper was a gas province. The geology, people said, just didn’t stack up for oil. Santos’s explorers kept pushing anyway, and Tirrawarra-1 proved them right. Gas and crude oil were discovered at Tirrawarra-1, and for the first time, oil flowed to the surface from a well in South Australia. In one moment, Santos had broken out of the “pipeline gas utility” box and into the world of oil—bigger markets, different pricing dynamics, and a whole new growth path.

And the discoveries didn’t stop at the Cooper’s edge. In 1977, Santos and partners drilled Poolowanna in the Ergomanga Basin, out in the Simpson Desert, producing the first oil in that area. It was quickly followed by Strzelecki 3, the first significant oil discovery in Ergomanga, producing more than 2,400 barrels a day. The message was getting louder: this wasn’t a one-field company anymore.

Then came the move that turned those barrels into a business. In the 1980s, Santos began construction of a liquids pipeline from Moomba to Stony Point near Whyalla in South Australia. This wasn’t just an engineering project—it was a strategic unlock. The pipeline gave Santos a way to move and market its liquids, expanded its footprint, and helped kick-start what would become a meaningful export industry through port facilities at what would later be known as Port Bonython.

The Cooper Basin Liquids Project, launched in 1981, was another major swing. Santos committed to building a condensate production facility, a fractionation plant, and port infrastructure—an investment of more than A$1.5 billion. The logic was straightforward: don’t just sell gas. Extract the higher-value liquids, process them, and ship them to where the margins are.

While it was building steel-and-concrete capabilities, Santos was also buying its way into new basins. Through the 1980s it acquired a majority stake in Vamgas, active in the Cooper since the 1960s. It took a majority of Latec Investments, with assets in the Amadeus Basin in the Northern Territory. In 1987, it acquired the holdings of Total and Western Mining Corporation in the Cooper and Ergomanga Basin areas.

Then, in 1988, Santos bought Peko Oil—bringing holdings in the Timor Sea, and interests in the United Kingdom and the United States. It also brought something even more important than acreage: Santos’s first offshore operations. Up to that point, Santos was an outback specialist. Peko forced the company to broaden its technical toolkit and its ambitions, taking it from deserts and pipelines into the offshore world.

By the end of the 1980s, Santos had evolved from a single-basin wildcatter into a diversified oil and gas producer: multiple Australian basins, new infrastructure, and a first taste of offshore and international exposure. It had become central to the east coast’s energy supply. But embedded in that success was a looming reality—no basin produces forever. Even the Cooper, for all its scale, would eventually decline. And that meant Santos would need its next growth engine.

IV. Expansion & International Ambitions (1990s–2000s)

The 1990s were Santos’s next reinvention. The company could see what every resource business eventually learns: even a great basin declines. If Santos wanted to be more than the Cooper Basin’s best operator, it had to get out of the Cooper Basin.

So it went shopping and it went exploring.

Through the decade, Santos kept up an active acquisition strategy, widening its footprint across Australia and into the region. In Queensland, it pushed deeper into the gas province by completing a new raw gas pipeline between Moomba and Ballera in 1992. In 1996, it added Parket and Parsley Australasia and MIM Petroleum, picking up exploration and production positions across the Surat, Cooper, and Ergomanga basins, plus interests offshore in places like Papua New Guinea, Indonesia, and Western Australia. By 1999, it had also expanded into Victoria.

Queensland, in particular, turned out to be a quiet masterstroke. The Ballera gas plant, established in 1991 and upgraded in 1997, anchored Santos in the Bowen and Surat basins—areas that would later sit at the center of Australia’s coal seam gas boom, and eventually the GLNG project.

But the biggest swing outside Australia was Papua New Guinea.

Santos had been involved in PNG since the 1980s, and in 1998 it became a producer there through the SE Gobe oil project in the Gulf Province. That same year it acquired a 24 per cent interest in PDL-1, a stake that gave it access to a significant part of the giant Hides gas field and made Santos a foundation partner in what would become the PNG LNG project.

At the time, Hides looked like stranded value: huge gas volumes, far from customers, with no obvious way to turn molecules in the ground into cash. But Santos was betting on a different future—one where Asian demand for LNG kept rising, and PNG’s proximity to Japan, Korea, and China turned “remote” into “advantaged.”

Still, the 2000s exposed the uncomfortable gap between ambition and reality. Cooper kept declining, putting pressure on volumes and cash flow from the company’s home base. Meanwhile, the growth options Santos had assembled—Queensland gas, PNG gas—were big, complex, and capital-intensive. They promised a new Santos, but not quickly.

Investors noticed. The share price drifted, and the company started to look caught in the middle: strong assets and real options, but not enough scale or balance sheet strength to pursue everything at once.

What Santos needed was a single, transformational project—something that could soak up Queensland gas, connect to booming Asian demand, and move Santos into the LNG export league.

That project was GLNG.

V. The GLNG Bet & The LNG Revolution (2007–2015)

The decision to build GLNG—Gladstone Liquefied Natural Gas—was one of the biggest calls Santos ever made. It was bold, politically fraught, and, in the end, transformative. But it also loaded the company with risk in almost every direction at once: technical, financial, and social.

Santos launched GLNG in 2007 to do something Australia hadn’t really done before at scale: turn Queensland gas—especially coal seam gas from the Bowen and Surat basins—into LNG and ship it to Asia. The structure of the project told you how big it was. GLNG was a joint venture between Santos and three global heavyweights: PETRONAS, Total, and KOGAS. And the build was massive: develop the upstream gas fields, run a 420-kilometre underground pipeline down to Gladstone, and construct a two-train liquefaction and storage facility on Curtis Island.

The engineering was only half the challenge. Coal seam gas as LNG feedstock was still a frontier. The method—extracting methane by pumping out large volumes of groundwater—triggered immediate concerns about aquifers, water quality, and the long-term impact on the land. On the surface, it meant industrialising huge swathes of working countryside, drilling thousands of wells, negotiating access with farmers, and facing intense local opposition.

As scoped, GLNG paired those coal seam gas resources with the Curtis Island plant: two LNG trains with a combined nameplate capacity of 7.8 million tonnes per annum. The plan was for first exports in 2015, backed by binding LNG sales agreements with PETRONAS and KOGAS totaling 7 mtpa. From final investment decision through the end of 2015, the gross capital cost was estimated at US$16 billion.

For Santos, the financial exposure was enormous. Its 30% share implied US$4.8 billion of capital expenditure—an amount that would push the balance sheet right to the edge. And unlike conventional gas, coal seam gas demanded relentless activity just to keep volumes steady. The drilling didn’t stop when construction finished; it became the operating model.

Then came the familiar LNG story: costs moved. Across Queensland, budgets expanded, and GLNG was no exception. Its price tag ultimately grew to US$18.5 billion.

Construction of the LNG plant on Curtis Island began in 2011. In October 2015, the first cargo finally left Gladstone, headed for South Korea. After decades as an outback producer, Santos had pulled off the leap: it was now an LNG exporter, competing in Asia’s premium gas markets.

But the timing couldn’t have been harsher. Just as GLNG came online, commodity prices collapsed. Oil—still a key reference point for LNG pricing—fell from above US$100 per barrel to below US$50. And Santos, after years of construction spending, was carrying heavy debt into that downturn.

GLNG had worked. But it had also set the stage for Santos’s darkest chapter.

VI. INFLECTION POINT #1: The 2015 Crisis & Near-Death Experience

In 2015, Santos ran straight into the cruelest timing in the LNG business. After years of effort and billions spent, GLNG finally came online. But instead of a victory lap, the company hit a wall: oil prices slumped, sentiment turned, and the debt taken on to build GLNG suddenly looked far more dangerous.

The board moved quickly. Managing Director and CEO David Knox agreed to step down once a successor was appointed. Chairman Peter Coates framed it in blunt terms: the company needed to confront “the fall in global oil prices” and what it was doing to Santos’s share price “relative to other oil and gas companies.” A “thorough strategic review of all options” was underway, he said, aimed at restoring and maximising shareholder value.

The market was already delivering its verdict. Over the year, Santos’s share price fell to roughly a third of where it had been, sinking to a 12-year low. The balance sheet, swollen by GLNG construction spending, no longer had the comfort of high commodity prices to lean on. And the financial results reflected it: half-year net profit dropped sharply, down 82%, dragged by much lower oil prices and higher exploration costs.

The strategic review wasn’t a formality. It put the unthinkable on the table: partial asset sales, potential mergers, even the possibility of a takeover. Santos chairman Peter Coates stepped in as executive chairman in the interim, running the process with the help of Deutsche Bank and Lazard. The company had a newly commissioned export project, but it was fighting for breathing room.

It also meant looking hard at the Knox era—because it contained both the reason Santos had become an LNG exporter and the reason it was now in trouble.

Knox, an Edinburgh-born oil and gas executive who joined Santos in 2007 and became CEO and Managing Director in July 2008, brought deep international experience. Before Santos, he’d been managing director for BP Developments in Australasia, and earlier worked for BP in the UK and Pakistan, and held management and engineering roles at ARCO and Shell.

Under Knox, Santos made the leap from a domestic gas producer into the Asian LNG game. In strategic terms, the call wasn’t crazy. Asian demand for gas was rising, and gas was increasingly positioned as a cleaner alternative to coal. But GLNG’s construction bill left Santos heavily leveraged. When prices fell, that leverage turned from “efficient” to “existential” almost overnight. And, alongside the financial strain, there were lingering investor questions about whether the company had enough gas reserves to consistently fill the project’s capacity.

The lesson of 2015 was painfully clear: Santos had assembled serious assets, but it had done it on a foundation that couldn’t absorb a commodity shock. To survive—let alone grow again—it needed a reset: tighter capital discipline, sharper operations, and leadership built for a turnaround.

That leader arrived the next year. His name was Kevin Gallagher.

VII. INFLECTION POINT #2: The Kevin Gallagher Turnaround (2016–2018)

When Kevin Gallagher walked into Santos’s Adelaide headquarters in February 2016, he didn’t inherit a growth story. He inherited a company that had just survived the first wave of a crisis and wasn’t sure it could withstand the second. The share price was battered, confidence was thin, and the balance sheet still carried the weight of GLNG—built for boom-time pricing, now living in a world that had moved on.

Most outside observers had the same read: Santos would have to shrink to survive. Maybe sell assets. Maybe merge. Maybe get bought.

Gallagher’s view was different. Santos didn’t need a grand new vision. It needed control—of costs, of execution, and of what it would and wouldn’t spend money on.

Gallagher was a drilling engineer by training, the kind of leader who’d come up through the mechanics of getting wells drilled and projects delivered. He first came to Australia to work with Woodside after a stint in the North Sea, and before joining Santos he ran Clough Ltd., an engineering and construction contractor. He arrived at Santos with a reputation for operational discipline—and Santos, at that moment, desperately needed discipline more than it needed charisma.

The early moves were blunt and practical: slash drilling costs, strip out inefficiency, and make the aging asset base perform like it was still hungry. Under Gallagher, Santos focused on lifting profitability from the assets it already had, so the company could better ride commodity cycles and stop feeling like every price move was a threat to its existence.

His blueprint became known internally as the “five core assets” strategy. Instead of trying to be everywhere, Santos would be excellent in a few places—its highest-quality, longest-life gas positions: Western Australia, the Cooper Basin, Queensland/NSW, Northern Australia/Timor-Leste, and Papua New Guinea. Everything else was secondary. Non-core assets could be sold, and the proceeds would do something Santos badly needed in 2016: pull debt down and restore flexibility.

The operating model followed the strategy. Costs came down hard as the company pushed efficiencies and renegotiated with suppliers. Production became cheaper. Execution tightened. And the Cooper Basin—often spoken about like a legacy asset in managed decline—started throwing off cash again. In a turnaround, that matters more than headlines. Cash buys time, and time buys options.

This period also set the logic for what came next. With a more disciplined, low-cost base and a strengthened balance sheet, Santos started to look less like a company trying not to drown and more like one that could choose its next moves. The company’s own framing of the approach was “Transform-Build-Grow”—stabilise first, then expand from a position of strength.

By 2018, the conversation around Santos had changed. The question wasn’t whether the company would make it. It was whether Gallagher would use the new stability to go on offense.

He did. And the next chapter was an acquisition spree that would remake Santos’s portfolio.

VIII. INFLECTION POINT #3: The Acquisition Spree (2018–2021)

Once Gallagher had stabilized Santos—cutting costs, rebuilding cash flow, and restoring balance-sheet credibility—he shifted from defense to offense. Between 2018 and 2021, Santos executed three major transactions that didn’t just add assets. They rewired the company’s geography, capabilities, and future options, and pushed it toward “regional champion” territory.

The Quadrant Energy Acquisition (2018)

The first big move came in August 2018, with a deal that neatly matched Gallagher’s playbook: buy high-quality, already-producing assets, plugged into infrastructure, in a basin where Santos wanted to be bigger.

Santos agreed to acquire 100% of Quadrant Energy for US$2.15 billion, plus potential contingent payments tied to resources from the recently struck Dorado offshore oil discovery. Quadrant brought exactly what Santos liked: producing oil and gas, development and appraisal opportunities, and a large inventory of discovered resources that could backfill existing infrastructure. It also came with a commanding position in the highly prospective Bedout Basin, where Dorado offered near-term development potential and significant exploration upside.

Dorado was the headline. It was widely viewed as Western Australia’s biggest oil discovery in years. Carnarvon Petroleum reported Dorado contained about 171 million barrels of oil on a 2C basis—putting it among the largest oil resources ever found on the North West Shelf.

But the real strategic win wasn’t just a discovery. It was control. The Quadrant deal gave Santos operatorship of the Varanus Island and Devil Creek gas processing facilities—key hubs in Western Australia’s gas system. That meant flexibility: optimize operations, pursue third-party gas opportunities, and, critically, secure a stronger position in a state where domestic gas mattered immensely. With that, Santos became the largest domestic gas supplier in Western Australia.

The ConocoPhillips Northern Australia Acquisition (2020)

The second deal landed in May 2020, at the peak of pandemic uncertainty—when markets were volatile and confidence was scarce. Santos closed the acquisition of ConocoPhillips’ northern Australia and Timor-Leste portfolio, picking up ageing offshore production at Bayu-Undan, subsea assets in the Timor Sea, and the onshore Darwin LNG (DLNG) plant, including the Bayu-Undan to Darwin Pipeline.

At completion, Santos increased its interest in Bayu-Undan and Darwin LNG to 68.4%, lifting production and cash flow. Just as important, it increased its interest in Barossa—the backfill project intended to keep Darwin LNG running—to 62.5%.

The final terms reflected the moment. Santos paid a reduced upfront purchase price of US$1.265 billion, plus a US$200 million contingent payment tied to a final investment decision on Barossa. The upfront amount was lower than the previously announced US$1.39 billion, with Santos and ConocoPhillips agreeing to the adjustment amid the market volatility and the deferral of Barossa FID.

Strategically, the logic was clear: Santos wasn’t just buying a set of assets. It was buying the keys to Darwin—operatorship of an LNG plant and the development pathway that could extend LNG production in northern Australia well into the future.

The Oil Search Merger (2021)

Then came the biggest swing. In December 2021, Santos completed its merger with Oil Search—an outcome that changed how the market could think about Santos at all.

On paper, it created a regional champion with a market capitalisation of about A$22 billion. On a pro-forma basis, the combined business had 2021 production of roughly 117 million barrels of oil equivalent and a 2P+2C resource base of 4,867 million barrels of oil equivalent. Santos also expected the merger to unlock pre-tax synergies of US$90–115 million per year. Oil Search shareholders received 0.6275 new Santos shares for each Oil Search share held on the 14 December 2021 record date.

But Oil Search wasn’t just “more barrels.” It brought a set of assets Santos couldn’t easily replicate: major exposure to PNG LNG, development rights for the Papua LNG expansion, and a new North American growth leg through Pikka on Alaska’s North Slope—one of the largest conventional oil discoveries in the United States in thirty years.

The combined company also had more financial firepower: an investment-grade balance sheet and more than US$5.5 billion of liquidity to self-fund development projects. And Santos leaned on a point it wanted investors to believe deeply by this stage: it knew how to integrate. After folding in Quadrant’s WA business and the ConocoPhillips NT unit, Santos said it had already delivered more than US$160 million in annual synergies.

Put together, the three moves did what Gallagher had been building toward since 2016. Santos emerged with operating interests across four LNG trains—GLNG, PNG LNG, and Darwin LNG—plus stakes in two major LNG growth projects, Papua LNG and Barossa. It added a material new oil development pathway in Alaska and deepened its grip on domestic gas infrastructure across Australia.

It was a bigger, more diversified Santos. And it was about to discover that being bigger doesn’t make the controversies go away—it just raises the stakes when they arrive.

IX. INFLECTION POINT #4: The Barossa Saga & Indigenous Rights Battles (2018–2025)

If the acquisition spree was Santos going on offense, Barossa was the reminder that modern energy projects don’t just get engineered. They get argued, litigated, and scrutinized from every angle.

Barossa became Santos’s biggest live development and, just as importantly, its most contested. It put almost every pressure point of the industry into one project: the economic case for new supply, the environmental case against it, and the question of who gets a real say when infrastructure crosses places of deep cultural importance.

On the business side, the rationale was straightforward. Barossa was positioned as a major new LNG supply source that would keep Darwin LNG running for decades. Santos described it as “world-class,” and at the time of final investment decision it was framed as the biggest investment in Australia’s oil and gas sector since 2012. In other words: Darwin needed gas, and Barossa was the backfill.

The build itself was enormous. Santos and its joint venture partners, SK E&S and JERA Co., Inc., had invested US$3.95 billion in the project to date. Five wells in a six-well program had been drilled, with the fifth being prepared for flow testing, and the final well expected to be completed in the third quarter. Santos said production from three wells could deliver full production rates at the Darwin LNG plant, if required.

But while the engineering advanced, the approvals didn’t move in a straight line.

In June 2022, traditional owners of the Tiwi Islands filed a lawsuit, supported by the Environmental Defenders Office, against Santos and the federal government. The core claim was that they had not been properly consulted. It was the first case in Australia to challenge an offshore project approval on the grounds of inadequate consultation with First Nations people. Munupi Senior Lawman and Tiwi Traditional Owner Dennis Tipakalippa argued that NOPSEMA, Australia’s offshore regulator, should not have approved Santos’s plans to drill the Barossa gas field because consultation had been insufficient.

In September 2022, Justice Mordecai Bromberg found NOPSEMA was “not lawfully satisfied that consultation had occurred,” and the court set aside Santos’s environment plan. Santos appealed and, in December, lost. NOPSEMA then ordered Santos to stop construction on the pipeline so a cultural heritage survey could be undertaken.

The delays were real, and so were the consequences. Barossa became a lightning rod, repeatedly described by critics as a “carbon bomb,” with claims that it would be the most carbon-intensive gas development in Australia once completed.

Still, Santos kept pushing the process forward. After the 2022 rulings blocked drilling under the original approvals, the company returned with a new plan. In February 2024, Santos received another approval from NOPSEMA that allowed work to continue, with the new development drilling and completions environment plan valid for five years.

By 2025, the project had shifted from courtroom headline back to construction milestone. Santos announced that the BW Opal FPSO arrived at the Barossa gas field, about 285 kilometres north of Darwin, on Sunday 15 June 2025. The vessel was the production centerpiece of the development. Santos said it had since been successfully hooked up, with final commissioning progressing to plan. The project remained on track for first gas in the third quarter of 2025, within original cost guidance, and far from where it started when the Offshore Project Proposal was accepted in 2018.

For investors, Barossa underlined three things. First, “social license” and regulatory risk had become core risks—projects that might once have been routine could now be stopped midstream. Second, Santos showed it could absorb those shocks and keep a major project moving. And third, the carbon-intensity debate wasn’t going away, which made Santos’s bet on carbon capture less like an optional add-on and more like part of the company’s credibility in a tightening climate and approvals environment.

X. INFLECTION POINT #5: The Carbon Capture Bet & Energy Transition (2020–Present)

Barossa showed how hard it had become to win permission to build new gas supply. Santos’s answer to that reality—and to rising climate pressure more broadly—wasn’t to walk away from hydrocarbons. It was to argue that the future belonged to “abated” production: keep producing gas, but capture and permanently store the carbon that comes with it. And to make that argument credible, Santos placed a big, very public bet on carbon capture and storage.

That bet is Moomba.

In October 2024, Santos said the Moomba CCS project in the Cooper Basin was operational and had begun capturing, injecting, and storing CO2 after commissioning and ramp-up. It positioned Moomba as Australia’s first large-scale hub for capturing and geologically storing carbon dioxide—built on the same outback operating footprint Santos has been refining for decades.

The investment decision came earlier. In November 2021, Santos and joint venture partner Beach Energy reached final investment decision on phase one of Moomba CCS. The project was reported at about A$220 million (US$165 million), with startup expected in 2024. Santos also laid out an ambition that mattered as much as the engineering: make CCS cheap enough to scale. The target was a full lifecycle cost of less than US$24 per tonne of CO2, with operating cash costs in the US$6–8 per tonne range, and first injection targeted for 2024.

By CCS standards, that cost positioning is the whole point. Phase one is designed to store up to 1.7 million tonnes of CO2 per year—large enough to matter, and low-cost enough, Santos argues, to compete with other emissions-reduction options.

And early performance gave the company something it badly wanted: proof of execution. Santos said that since coming online in September 2024, Moomba CCS had safely stored 800,000 tonnes of CO2. In its 2024 Sustainability and Climate Report, Santos also highlighted a 26% reduction in Scope 1 and 2 emissions versus its 2019–20 baseline—putting it at 84% progress toward its 2030 target of a 30% reduction. It said the phase one startup contributed significantly, capturing and storing around 340,000 tonnes of CO2e.

But Santos isn’t treating CCS only as an internal decarbonisation tool. The bigger ambition is to turn storage into a business.

Santos points to scale potential in the Cooper/Eromanga system: a theoretical capacity to inject up to 20 Mt of CO2e per year for up to 50 years. Phase 2 of Moomba CCS is aimed at using depleted reservoirs not just for Santos’s emissions, but to store third-party CO2—potentially from domestic sources and even Asian customers—building what it describes as a carbon management services business. Industry researchers have pointed to the size of the prize if cross-border carbon transport becomes real at scale: Wood Mackenzie estimated the Asia-Pacific region could account for nearly half the global market, with total CCS investment in the region potentially reaching US$622 billion by 2050.

This is also where Gallagher’s broader strategy shows up. Santos has framed its decarbonisation plan as one built around existing infrastructure: backfill and extend gas operations, reduce operational emissions through CCS, and develop lower-carbon fuels like hydrogen. Under Gallagher, Santos also says it made the world’s first booking of carbon storage reserves, and it has positioned Moomba as one of the largest CCS projects in development anywhere.

None of this is risk-free. CCS remains controversial, with critics arguing it can become a license to keep producing fossil fuels. The economics lean heavily on policy settings and carbon pricing frameworks that can shift. And the “commercial” market for third-party storage still has to be proven—customers at meaningful scale aren’t yet a given.

But Santos is betting on two things at once: that natural gas remains essential through the transition, and that customers will increasingly pay for “abated” gas—gas whose associated carbon is captured and stored—to reduce their own emissions footprint. If that world arrives, Moomba isn’t just a compliance project. It’s a strategic advantage Santos started building early.

XI. The Modern Santos: Projects, Scale & Current Positioning

By the back half of 2025, Santos sat in a familiar place for a company that has spent seventy years making big bets: on the verge of major new production, with investors watching to see whether the next wave delivers what the last one promised. Barossa, after years of legal and regulatory turbulence, was heading toward first gas. Pikka, the Alaska oil project Santos picked up through Oil Search, was moving from “option” to “real project.” And in the background, Moomba CCS was ramping—Santos’s proof point for its claim that it could keep producing hydrocarbons in a carbon-constrained world.

Financially, 2024 showed a company that, at least on paper, had regained its footing. Santos reported annual production of 87.1 mmboe and sales volumes of 91.7 mmboe. It generated free cash flow from operations of US$1,891 million and an underlying profit of US$1,201 million. It declared a final dividend of US 10.3 cents per share, unfranked; combined with the interim dividend, Santos said it returned US$757 million to shareholders for the year, equal to 40 per cent of free cash flow from operations. It also reported EBITDAX of US$3.7 billion, gearing of 23.9%, and liquidity of US$4.4 billion.

The pitch from management was straightforward: the next phase would be driven by two projects that were already funded, already under construction, and close enough to touch. Santos described Barossa as a world class asset and said that, together with Pikka phase one, the two developments were expected to lift production by around 30 per cent over roughly the next eighteen months compared with 2024. The promise wasn’t just higher volumes. It was long-lived, more stable cash flows—and, in turn, “compelling shareholder returns.”

Pikka is the cleanest example of how the Oil Search merger changed Santos’s trajectory. It’s the company’s entry into U.S. upstream, on Alaska’s North Slope. In August 2022, Santos, as operator of the Pikka Unit joint venture, took final investment decision on the project. Santos described the Nanushuk play in the Pikka Unit as one of the largest conventional oil discoveries in the United States in the last 30 years, and said Pikka phase one was the biggest development on Alaska’s North Slope in more than 20 years. Santos also positioned Pikka as comparatively low emissions intensity, saying it sat in the top quartile globally for greenhouse gas emissions performance among oil and gas development projects.

In the first half of 2025, Santos pointed to momentum. It reported strong half-year results and said it was pulling forward its schedule: “I’m pleased to announce that we’re accelerating first oil guidance for our Pikka phase 1 project to the first quarter of 2026. With 21 wells drilled, the project is making strong progress.” Santos said the phase one seawater treatment plant and all production modules were on location, and it reported free cash flow from operations of US$1.1 billion for the first half.

At full stride, Santos has said Pikka will reach peak production of 80,000 barrels of oil per day. The project, on state land, is estimated to generate more than $200 million in revenues to Alaska in its first year, largely through royalties. The $3.1 billion development is located about 11 miles northeast of the village of Nuiqsut, near the Arctic Ocean, and Santos said the schedule was running months ahead of what had previously been anticipated.

But 2025 also underlined something else: Santos’s portfolio has become valuable enough that it keeps attracting would-be partners—and would-be buyers.

First came the failed Woodside talks. In early 2024, Woodside Energy said it ended discussions with Santos about a potential merger that would have created an enormous global oil and gas company. Woodside’s explanation was simple: it would only pursue a deal that added value for its shareholders.

Then came the takeover approach that made the strategic value feel even more concrete. Abu Dhabi National Oil Co. made a bid for Santos through its investment arm, XRG, in a move aimed at expanding its liquefied natural gas footprint. The Santos board recommended ADNOC’s cash offer of $5.76 per share, described as a 28% premium to the prior Friday close. The logic for ADNOC was clear: a stake in major LNG operations across Australia and Papua New Guinea—if regulatory approvals could be secured.

And then it fell apart. XRG withdrew its roughly $19 billion bid, walking away from a high-profile attempt to buy into Australia’s LNG market. ADNOC cited a “combination of factors” and said the decision was strictly commercial, reflecting disagreements on terms including valuation and tax.

The pattern is telling. Santos has spent the last decade rebuilding itself into a company with real scale—multiple LNG positions, major growth projects, and now a large CCS facility—yet it remains in an in-between zone in global terms: big enough to matter, but not so big that it’s out of reach. The repeated collapse of merger talks and takeover bids points to a tension that’s likely to define the next chapter: Santos believes its standalone plan will pay off as Barossa and Pikka come online, while potential partners and acquirers are still trying to put a price on the same future—and coming up short.

XII. Bull Case, Bear Case & Investment Considerations

The Bull Case

The optimistic view on Santos comes down to a few reinforcing ideas:

A real production step-up is close: With Barossa and Pikka moving toward start-up, Santos expects a meaningful lift in production through the second half of this decade—around 30% by 2027. And crucially, this isn’t a story built on hoping the next wildcat well hits. The growth is coming from projects that are already sanctioned, already being built, and already being managed against known cost and schedule constraints.

LNG demand has a long runway: Whatever you think about the long-term destination of the energy system, the near- and medium-term picture in Asia still features a lot of LNG. As countries electrify and try to reduce coal use, LNG remains one of the fastest ways to add reliable, lower-emissions energy. That’s the backdrop for Santos’s portfolio across GLNG, PNG LNG, and Darwin LNG—assets that are geographically close to the big demand centers in Japan, Korea, China, and Southeast Asia. Gallagher has leaned into the commercial strength of that book, saying, “Our agreements with tier one customers strengthen Santos' LNG portfolio which is around 90 per cent contracted over the next five years with strong pricing driven by the high heating value of our LNG, reliability of supply, and our proximity to growing markets in Asia.”

CCS could become more than a compliance tool: If carbon pricing strengthens, or if customers increasingly insist on “abated” molecules, Santos’s early work at Moomba has upside beyond emissions reduction. The bull case is that storage becomes a product: third parties pay Santos to sequester their emissions, turning a decarbonisation strategy into a new line of business.

The Gallagher record matters: The last decade is the résumé. Santos went from a near-death balance-sheet moment to a larger, more diversified company with multiple LNG positions—while also integrating major acquisitions like Quadrant, ConocoPhillips’ northern assets, and Oil Search. If you believe the same team can execute the next wave—Barossa, Pikka, and CCS scale-up—then the story keeps compounding.

The market may still be underpricing the turnaround: Even after everything that’s changed, Santos has often traded at a discount to global peers. A big part of that is investor skepticism: Australian regulatory risk, carbon intensity headlines, and the inherent uncertainty of LNG pricing. The bull view is simple: deliver the projects, prove the cash flow, and the discount narrows.

The Bear Case

The skeptical view is equally straightforward—and hard to dismiss:

Regulatory and climate risk isn’t theoretical: Barossa demonstrated how quickly a project can be stopped, re-approved, then contested again. Australia’s environment for new fossil fuel developments has become tougher, and the international pressure on emissions-intensive projects isn’t easing. Barossa has been labelled a “carbon bomb” by critics, and has been described as likely to be the most carbon-intensive gas development in Australia once completed. Even if Santos executes well, the rules and the politics can still change underneath it.

Santos lives and dies by commodity prices: The company’s cash flow is still tied to oil and LNG. Hedging can smooth some volatility, but not eliminate it. A sustained downturn would squeeze free cash flow and could force tough choices—slower growth, reduced returns to shareholders, or both.

CCS is a big bet with real execution risk: Moomba’s phase one is operating, but the larger vision—scaling storage materially and building a third-party carbon storage market—hasn’t yet been proven at the levels Santos is aiming for. The customer side is the question mark: commitments for third-party storage are still limited, and the economics depend heavily on policy settings.

Leadership succession could become a storyline: Gallagher has been central to the turnaround narrative. With his A$6 million “golden handcuff” agreement set to expire, and no obvious successor clearly established, investors have to at least consider the risk that leadership transition becomes disruptive at exactly the wrong time—right as Barossa and Pikka ramp.

Being “in play” cuts both ways: Santos has drawn serious interest from potential partners and buyers. That can be validating—but it can also highlight a gap between what management believes the company is worth and what outsiders are willing to pay. If Santos remains independent, the burden of proof is on delivery. Rejecting suitors only works if the standalone plan shows up in results.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Supplier Power (Moderate): Santos controls its own production base, which limits dependence on any one supplier in day-to-day operations. But for offshore developments, LNG shipping, and CCS, there are still bottlenecks—specialised equipment and services that are concentrated among a relatively small number of global vendors.

Buyer Power (Moderate-High): Long-term LNG contracts with large, creditworthy counterparties help. But LNG markets have become more liquid, and that liquidity gives buyers more alternatives over time—more ability to negotiate, and more ability to switch supply.

Threat of Substitutes (Growing): Over the long arc, renewables, batteries, and eventually hydrogen can displace gas in some use cases. The counterpoint is that intermittency and industrial demand keep gas relevant—particularly through the 2030s, and potentially beyond—depending on policy and technology trajectories.

Competitive Rivalry (High): Santos competes in a global LNG market where new supply keeps arriving, including major volumes from the US and the Middle East. Australia, in many cases, sits higher on the cost curve than those regions, which puts constant pressure on discipline and execution.

Barriers to Entry (Very High): LNG is brutally capital-intensive and technically complex, and approvals have only become harder. Santos’s advantage is that it already owns critical infrastructure. New entrants can’t replicate that quickly, cheaply, or easily.

Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers

Through Helmer’s lens, Santos has a few real advantages—though their durability varies:

Counter-Positioning: The integrated CCS strategy is a form of counter-positioning. Santos is leaning into carbon storage as a core capability while parts of the industry hesitate, betting that “abated” production becomes commercially valuable. If carbon markets and customer demand develop the way Santos expects, that head start could matter.

Cornered Resource: Few assets are harder to replicate than decades of Cooper Basin infrastructure and operating experience. Likewise, positions in PNG LNG and Barossa provide access to resources and projects that competitors can’t simply copy-and-paste into their portfolios.

Scale Economies: As a major domestic gas producer, Santos can spread overhead, procurement, and operating capability across a large base—advantages smaller competitors don’t have.

Process Power: Gallagher’s operating model—cost discipline, drilling efficiency, and sharper execution—has been a clear differentiator. The open question is whether that process edge holds as the company grows and takes on more complex developments.

Key KPIs to Monitor

If you’re tracking Santos as an investment, three measures tell you quickly whether the story is working:

-

Unit Production Cost ($/boe): This is the clearest read on operational discipline. Santos has targeted unit production costs below US$7 per boe once Barossa and Pikka Phase 1 are online. If costs drift above that, the whole “low-cost operator” positioning weakens.

-

Free Cash Flow Yield: Santos’s framework targets returning 40% of free cash flow to shareholders through dividends. Watch whether free cash flow holds up through the ramp of Barossa and Pikka, and whether shareholder returns remain consistent with that promise.

-

Production Growth (mmboe): The company has signaled production rising from roughly 87 mmboe in 2024 to over 110 mmboe by 2027 as new projects ramp. If volumes miss, it likely means execution issues. If they beat, it strengthens the case that the operating model is working.

Regulatory and Legal Considerations

A few uncertainties remain central to the Santos outlook:

-

Indigenous consultation requirements: The Barossa litigation created a sharper standard and a clearer precedent for First Nations consultation on offshore projects. Future developments could face similar challenges, with real schedule and cost implications.

-

Carbon policy volatility: Australia’s Safeguard Mechanism and broader climate policy continue to evolve. That creates uncertainty around compliance costs, offsets, and the economics of emissions-intensive projects.

-

Foreign investment review: The XRG process showed how much scrutiny can attach to foreign interest in strategic Australian energy assets. Even if another bidder emerges, approvals and politics may shape what’s possible.

Conclusion

Santos’s seventy-year journey—from outback wildcatters to an Asia-Pacific LNG player—has been defined by reinvention under pressure. The company survived the GLNG hangover, scaled through acquisitions, and is now trying to prove a modern version of the same core idea: build long-life energy assets, run them cheaply, and keep them relevant in a carbon-constrained world.

What happens next hinges on execution. Barossa and Pikka need to arrive on time and perform. Moomba CCS needs to keep operating reliably, and the broader carbon storage market needs to mature if Santos wants CCS to become a meaningful business line, not just a talking point.

But the through-line is the same one that started in 1954: Santos has repeatedly been willing to bet that value exists where others see empty land—or, now, an industry that many assume must simply shrink.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music