Washington H. Soul Pattinson: Australia's 122-Year Investing Dynasty

I. Introduction: A Pharmacy That Became a $14 Billion Investment House

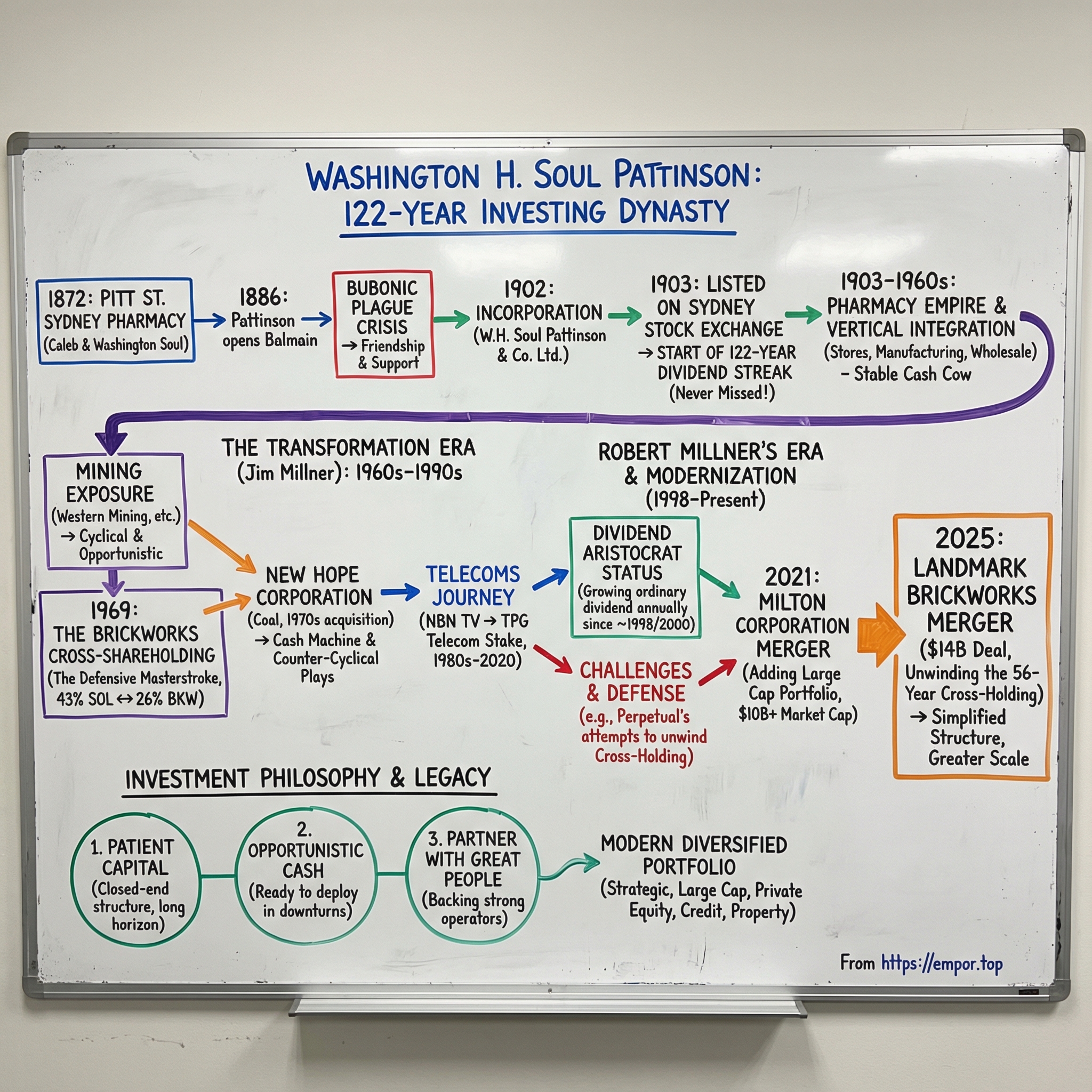

Picture colonial Sydney in 1872. Pitt Street is loud with hooves and wagon wheels. Nights are lit by gas lamps. And at 177 Pitt Street, a father and son—Caleb Soul and Washington Soul—open a modest pharmacy, selling tonics and remedies to a young city still figuring out what it wants to become.

That single storefront was the seed of Washington H. Soul Pattinson. Not just an old Australian company, but one that would go on to list on the Sydney Stock Exchange, live through wars and recessions, repel takeover attempts, and eventually emerge as a diversified investment house worth around $14 billion.

Longevity alone isn’t the headline. The headline is the discipline that came with it.

Since listing in 1903, Soul Patts has never missed a dividend payment. And it has increased that dividend every year for the past 27 years. In other words: a century-plus of showing up for shareholders, and nearly three decades of steadily raising the bar. On the ASX, no one else has a record quite like it.

By that definition, Soul Patts became Australia’s first true “dividend aristocrat”—a company that has raised its dividend annually for 25 years or more. Then, in August 2025, as the company prepared for its 125-year listing anniversary, a corporate historian uncovered an even longer streak: Soul Patts had actually been increasing its ordinary dividend every year since 1998, pushing the run further back than anyone had been crediting it for.

There’s another ingredient you almost never see in public markets anymore: continuity. Soul Patts remains one of the few listed companies managed by the same family from the start. Across five generations, the Pattinson/Millner lineage has kept its hands on the wheel while the rest of corporate Australia cycled through CEOs, strategies, and shareholder fashions.

And then, in September 2025, the company did something that felt almost impossible given its history: it agreed to unwind the structure that had defined it for more than half a century. Soul Patts and Brickworks announced an A$14 billion merger, and the market loved it—shares in both jumped. The deal finally dismantled their 56-year cross-shareholding arrangement: a strange, elegant, and deeply controversial pact that had served as both a takeover shield and a perpetual source of complexity.

People often call Soul Patts “Australia’s Berkshire Hathaway.” The comparison is useful, but it doesn’t quite capture what makes this story unique. Like Berkshire, Soul Patts is built on patient capital and long-term ownership. Unlike Berkshire, it has stayed under family stewardship for more than a century—through booms, busts, and entire eras of Australian capitalism.

So how does a chain of pharmacies turn into one of the country’s great investing institutions? How did a family business built on prescriptions become a multi-asset portfolio built on judgement? And what does that 2025 Brickworks merger unlock for the next chapter?

Let’s start at the beginning.

II. The Founding Era: Pharmacies, Friendship, and Incorporation (1872–1903)

Soul Patts begins as two separate pharmacy businesses that eventually became one—not through a hostile takeover or a boardroom ambush, but through a friendship that held up under pressure.

In 1872, Caleb Soul and his son, Washington Handley Soul, opened a pharmacy at 177 Pitt Street in Sydney. Fourteen years later, in 1886, Lewy Pattinson opened his own pharmacy in Balmain.

This was a booming, chaotic moment for Sydney. The gold rush era had pulled people into the city and money through it. Streets were filling, suburbs were spreading, and everyday life still came with real risk. In a world without universal healthcare, the local chemist wasn’t a convenience. It was the frontline—where working families went for advice, remedies, and whatever relief could be offered before things got serious.

The Souls were positioned right in the commercial heart of the city. Pattinson built his business in a working-class suburb. Different neighborhoods, same essential role. And importantly: they didn’t go to war over turf. They became friends, and they stayed out of each other’s way.

Then came the moment that turned a friendly relationship into something much more durable.

One day in the 1890s, Pattinson arrived at his head office after his usual morning rounds—he’d ride shop to shop, then tether his horse outside when he got in around lunchtime. But this time, he found the whole block boarded up. Sydney had been hit by a bubonic plague outbreak, and authorities were quarantining sections of the city.

For a business built on a physical location, that kind of shutdown wasn’t an inconvenience. It was an existential threat. And waiting for him was Washington Soul. He told Pattinson: “Mr. Pattinson, I have taken the liberty of moving your head office to our head office at 160 Pitt Street, Sydney. Please continue to use it until you are allowed back into your own premises.”

No contracts. No negotiations. Just a practical act of generosity in the middle of a crisis.

That gesture stayed with Pattinson. And years later, when Washington Soul decided he wanted out of the pharmacy business, he didn’t go looking for the highest bidder. He went to the person he trusted.

Pattinson agreed to buy him out. The deal took effect from 1 April 1902, and the business was incorporated as Washington H. Soul Pattinson & Company Limited.

The next decision is the tell. Pattinson could have dropped the Soul name entirely. He had bought the business outright. But out of respect for his old friends, he kept it—and in doing so, he created one of the most enduring names in Australian corporate history.

The first public offering of shares followed in December 1902. And on 21 January 1903, Washington H. Soul Pattinson and Company Limited listed on the Sydney Stock Exchange.

Australia itself was only just getting started—the colonies had federated into the Commonwealth in 1901. Soul Patts, in other words, was there near the beginning of the modern nation’s economic life. And it has outlasted almost everyone from that era. It’s the second-oldest company on the ASX still operating today, behind only BHP, which listed in 1885.

Listing was a sharp move. Most family businesses at the time stayed private and insular. Pattinson chose something harder: public markets, outside shareholders, and broader access to capital—while still keeping family influence at the center. It’s a balancing act Soul Patts would go on to refine for more than a century.

III. The Pharmacy Empire and Early Dominance (1903–1960s)

As a newly listed company, Soul Patts did what great young public companies are supposed to do: it got bigger, steadily, year after year, by getting very good at one thing.

In 1903, it had 21 pharmacy stores. Over the following decades, it expanded across the country until, by the 1950s, it was a dominant force in Australian retail pharmacy. The store count grew to 42 company-operated locations by that point, and the model kept spreading. By the 1980s, it would extend its reach even further through about 300 agency stores—Soul Patts’ brand on the door, but not always Soul Patts’ staff behind the counter.

But the real edge wasn’t just the number of storefronts. It was what sat behind them.

By World War Two, Soul Patts wasn’t simply selling medicines. It had built manufacturing and warehouse facilities too, pushing into wholesale distribution and production. In modern terms, it had vertically integrated. That meant more control over supply, more resilience when conditions tightened, and more protection for margins when competitors showed up.

Then came the Great Depression. Plenty of businesses didn’t make it through the 1930s. Soul Patts did—and when the economy began to recover, it leaned back into expansion. Those pharmacy earnings didn’t just keep the lights on. They became the capital base that would later fund a much bigger ambition.

All of this was anchored—literally—by an address that became part of the company’s identity.

The Soul Pattinson Building at 158–160 Pitt Street evolved into a Sydney landmark. In 1887, the original premises were replaced by a new store called Phoenix Chambers. For more than a century after that, the same site served as both the company’s head office and its flagship store, right up until the store finally closed in 2018. In a city that reinvents itself every few decades, Soul Patts stayed put.

Inside, the flagship location wasn’t just functional—it was unusually thoughtful for its era. There was an American-style soda fountain that lasted until 1948. There was a Ladies Department run by a nurse. Long before “customer experience” became a management cliché, Soul Patts was building loyalty the old-fashioned way: by making the place feel modern, reassuring, and worth returning to.

That long-term orientation showed up in the people, too. Leadership passed down through the family in a tight line: from Lewy Pattinson to his eldest son, William Frederick Pattinson; then to William’s nephew, Jim Millner; and later to Robert Millner. The transition from Pattinson to Millner wasn’t a break—it was family continuity through marriage, with Jim Millner’s mother, Mary, being Lewy Pattinson’s daughter.

And it wasn’t only the family at the top that stayed. More than 40 employees worked at Soul Patts for over 50 years, and multiple generations from families like the Dixsons, Spences, Rowes, and Letters built careers there.

This wasn’t nepotism as a quirk. It was loyalty as a system—one that compounded institutional knowledge, reinforced patience, and made long-term planning feel natural rather than heroic.

The pharmacy empire threw off steady cash and dependable profits. But by the 1960s, the ground under retail pharmacy started to shift. Competition intensified, and the business began to look less like a protected niche and more like a battleground.

The family faced a decision: fight harder to defend what they had, or use what the pharmacies had built to become something else.

They chose transformation.

IV. Jim Millner's Transformation: From Pharmacist to Investment Powerhouse (1960s–1970s)

The man who would remake Soul Patts didn’t arrive as a glossy, modern CEO. He arrived shaped by war, scarcity, and a very clear-eyed sense of what matters when everything else gets stripped away.

James Sinclair Millner was born in Sydney in 1919. His father, Thomas George Millner, was a Colonel in the Australian Army. His mother, Mary, was Lewy Pattinson’s daughter, tying him directly into the family line that had guided Soul Patts since incorporation. He grew up in Cheltenham, attended Newington College, and studied pharmacy at the University of Sydney—the traditional training ground for the next generation in a pharmacy-led business.

Then history interrupted.

In 1940, Millner signed up for officer training, and by 21 he’d been promoted to Captain. He was posted to Malaya. When Singapore fell, he was captured by the Japanese and spent the rest of the war as a prisoner, held first at Changi Prison in Singapore and later at Sandakan in Borneo.

Those names carry weight for a reason. Changi and Sandakan were among the most brutal POW camps in the Pacific. Thousands of Allied prisoners died from disease, malnutrition, and execution. The Sandakan Death Marches alone killed roughly 2,400 prisoners. Millner survived and was released in 1945.

When he came home, he did something telling: he went back and finished his studies, completing a Materia Medica (Pharmacy) course in 1947, and then joined Washington H. Soul Pattinson. He rose steadily—director by 1957—and in 1969 he became Chairman, a role he would hold until 1998.

That era is the hinge point in this entire story. Because Millner didn’t just expand the pharmacy chain. He changed what the company was.

The shift began with a simple exposure: mining. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Millner was invited onto the board of Australian Oil and Gas. At the time, it was described as the biggest mining company in Australia—bigger than BHP. Another director was Professor Eric Rudd, a geologist with deep conviction about what was coming next. Millner and Rudd travelled widely—around Australia, and also to places like New Guinea and Fiji—looking at geology, projects, and prospects.

And they reached the same conclusion: a mining boom was coming.

So Soul Patts started buying stakes. Western Mining. Cleveland Tin. Emperor Mines. Peko-Wallsend. This wasn’t a side bet. It was the beginning of Soul Patts treating capital allocation as the core craft—not just running stores, but building an investment engine.

Millner understood the asymmetry. Pharmacies produced dependable cash flow, year after year. Mining was volatile, cyclical, and occasionally spectacular. Put them together and you get a machine: a stable base that keeps generating capital, and a portfolio that can take advantage of big, long-cycle opportunities—especially when markets panic and assets go on sale.

That combination—steady cash plus opportunistic investing—became the Soul Patts template.

The 1960s and 1970s also marked a deliberate expansion into building materials and resources. That included investments in Brickworks and the purchase of what is now New Hope Corporation—moves that would come to define Soul Patts for decades.

And crucially, Millner had the time horizon to let these bets work. His chairmanship ran nearly three decades. In modern corporate life, that’s almost an entire era. It meant strategies didn’t have to “prove themselves” in twelve months. They could compound over ten or twenty years.

People who knew the company often traced its signature frugality back to Millner’s wartime experience. He wasn’t a corporate showman. He had lived through the extreme version of making do. When he took over, Soul Patts was a chain of profitable pharmacies. When he was done, the foundations were in place for the diversified investment house it would become.

V. The Brickworks Cross-Shareholding: A Defensive Masterstroke (1969)

In 1969, Jim Millner put in place a corporate move that would shape Soul Patts for the next half-century. It was elegant, defensive, and—depending on who you ask—either brilliantly shareholder-friendly or hopelessly entrenching.

Soul Patts and Brickworks entered a cross-shareholding arrangement that bound the two companies together. Soul Patts held roughly 43% of Brickworks, and Brickworks held roughly 26% of Soul Patts. The stated intent was straightforward: bring stability to both share registers, create room to invest for growth, and make it far harder for an outsider to muscle either company into a takeover.

The context matters. Late-1960s Australia was an era when corporate raiders were very real. Hugh Dive, chief investment officer of Atlas Funds, described it plainly: “The structure [was] odd, set up in 1969 as a share swap between two companies with similar market caps to protect against each other being taken over.”

This wasn’t paranoia. This was the age of Industrial Equity Limited, led by Ron Brierley, and the broader takeover culture that produced names like John Elliott and Robert Holmes a Court. Robert Millner later recalled how quickly he learned what kind of world Soul Patts operated in: “I had a great education about three or four months after I had taken over as chairman. I got a phone call from Sir Ron Brierley. I nearly died, of course. Just been in the job for a couple of months.” In Millner’s telling, Brierley was blunt: “We’re going to come and take Brickworks over.”

Soul Patts, he said, was fortunate to have David Fairfull on the board at the time—an investment banker who understood exactly what those words could mean.

The genius of the cross-shareholding was that it didn’t rely on a poison pill or a scramble for white knights. It just sat there, permanently. To take over Soul Patts, a bidder would effectively need to deal with Brickworks’ 26% stake. But Brickworks was intertwined with Soul Patts, and Soul Patts’ 43% holding in Brickworks gave it enormous influence over anything that threatened the arrangement. The logic loop made a clean takeover almost impossible without cooperation from the very people the raider was trying to displace.

Over time, that same self-reinforcing design became one of the company’s two defining controversies. Soul Patts had to defend the Brickworks cross-shareholding repeatedly, including against pressure from high-profile opponents like Ron Brierley and, later, Perpetual.

The fight peaked in the 2010s. From 2011 onward, Perpetual Investment Management made multiple proposals aimed at unwinding the structure. In 2014, it escalated to the Federal Court, arguing that maintaining the cross-shareholding was oppressive to minority shareholders. Perpetual’s case was ultimately dismissed in 2017. Justice Jayne Jagot found that keeping the structure in place was neither oppressive nor unfair in the circumstances, and the claim was dismissed with costs.

Supporters saw that outcome as a validation of what the structure enabled: insulation from market fashion, the ability to take a genuinely long-term view, and protection from opportunistic takeover tactics. It was also a relic of its time. The cross-shareholding predated the current Corporations Act and wouldn’t be permitted if two companies tried to create it from scratch today. And it was unusual—something analysts struggled to match elsewhere in the ASX 200.

Critics, though, never stopped arguing the other side: that the arrangement entrenched control, complicated governance, and left both companies trading at a persistent discount. As Hugh Dive put it, “Historically, we have avoided both as the cross holdings/complicated structure saw both companies trade at a discount to their peers.” To many institutional investors and index funds, it made both stocks harder to own, harder to analyze, and harder to explain.

In the end, the structure lasted far longer than anyone could have predicted in 1969. And it didn’t get unwound by a raider, or by a court, or by activist pressure. It survived until 2025—when Soul Patts and Brickworks themselves finally decided it was time to end it, and chose to do it the one way no outsider could: by merging.

VI. New Hope Corporation: The Coal Cash Machine

Of all Soul Patts’ investments, none has been more consequential—or more contested—than New Hope Corporation.

New Hope is an Australian thermal coal miner headquartered in Brisbane. Its operations include the New Acland mine, the Bengalla mine, and Queensland Bulk Handling. The company was established in 1952 in Ipswich, Queensland, and in the 1970s it was acquired by Soul Patts. In 1970, Washington H. Soul Pattinson took a 60% controlling stake—just as New Hope hit a major milestone in output from underground mining.

The timing mattered. The 1970s energy crisis made coal newly strategic. Australia was beginning its rise as a major exporter to Asia. And Soul Patts, with steady cash flows from its legacy pharmacy business, had capital ready to deploy.

By 1980, New Hope was pushing into exports. It was among the first to secure trials of Ipswich coal into the Japanese market. Its first export shipment—Bundamba coal—left from the Maynegrain grain terminal at Pinkenba on 10 September 1980 aboard the MV Floret. As exports scaled, so did the logic for purpose-built infrastructure: increasing export volumes quickly made a dedicated coal terminal a necessity.

But New Hope’s real importance to the Soul Patts story isn’t just that it mined coal. It’s that it became a live demonstration of the group’s investing style: patient ownership, cyclical discipline, and a willingness to act when others can’t.

As New Hope itself put it: “WHSP holds 60% of our shares, we are controlled by them and they are patient investors and that is definitely a competitive advantage of the firm.”

You can see that advantage in the company’s history of buying and selling through the cycle. New Hope pioneered Australian investment in Indonesian coal through its acquisition of the Adarro project, then sold its interest for US$406 million in 2005.

Then came the defining trade. In July 2008, New Hope agreed to sell its New Saraji Coal Project to BHP Mitsubishi Alliance for $2.45 billion. New Hope had identified more than 690 million tonnes of coal at New Saraji.

Step back and appreciate what that meant in practice: Soul Patts backed New Hope in 1970, held and developed assets over decades, and then New Hope sold a crown-jewel project at the peak of the China-driven commodity boom—months before the Global Financial Crisis. It’s hard to time a cycle better than that.

The pattern repeated elsewhere. New Hope had picked up New Saraji—near BHP Billiton’s Saraji open-cut mine in central Queensland—for next to nothing, and sold out in 2008 for $2.45 billion. In 2006, it acquired an interest in Arrow Energy for $48 million, and in 2010 it received $650 million for that same stake.

That’s the New Hope playbook in one line: accumulate when the market is gloomy, and sell when the market is euphoric.

With cash in the bank, New Hope then reinvested into quality at the right moment—buying Rio Tinto’s 40% stake in the Bengalla thermal coal mine for $865 million. The timing of that move was the point: it reflected a board-led strategy of securing a low-cost asset at an attractive price when sentiment was weak.

When coal prices collapsed in 2015, New Hope had the balance sheet to move. It wasn’t forced to sell; it could shop. That’s counter-cyclical capital allocation, the Soul Patts way.

“We have been very patient in holding onto that capital during the downtown. In 2015 we came to a point where we believed the coal price reached unsustainable levels.” “We formed the view that this was the appropriate time to start looking for an asset. We had been looking continuously for coal assets for sale and what attracted us to Rio Tinto’s Bengalla stake was its position on the cost curve.”

Of course, New Hope is also controversial—because thermal coal is controversial. Climate concerns have put the asset under a different kind of spotlight, and critics have targeted Robert Millner for Soul Patts’ steadfast stance on the continued role of coal in meeting global electricity needs.

What’s undeniable is how central New Hope has been to the portfolio. Around 40% of Soul Patts’ net asset value sits in three listed companies: Brickworks, TPG Telecom, and New Hope. Soul Patts holds about 43% of Brickworks (which in turn owns about 26% of Soul Patts), around 13% of TPG, and around 39% of New Hope.

For decades, New Hope generated substantial cash flows that Soul Patts could redeploy across the rest of the group. Whether that exposure looks wise over the very long term is still debated—but as an example of disciplined, cycle-aware capital allocation, it has been one of the most powerful engines Soul Patts ever built.

VII. The TPG Telecom Journey: From TV Station to Telco Giant (1980s–2020)

Soul Patts’ path into telecoms started in the least Silicon Valley way imaginable: with a regional TV station.

In the 1980s, Soul Patts bought NBN Television Station, the broadcaster serving Newcastle and the Hunter Valley. (Not the National Broadband Network—different NBN.) As part of Jim Millner’s diversification push, the group suddenly owned a business built around transmission towers, spectrum, and communications infrastructure.

And once you own those kinds of assets, you start noticing opportunities that don’t look like “television” anymore.

Over time, Soul Patts used NBN’s infrastructure and spectrum position as a springboard into telecommunications services. That evolution eventually crystallized into a listed vehicle. SP Telecommunications Limited—incorporating Soul Pattinson Telecommunications Pty Limited—listed on the ASX on 10 May 2001 after an initial public offering. Before the listing, it had been wholly owned by Washington H. Soul Pattinson, which retained an approximate 56% stake.

The shift from broadcasting to telecoms wasn’t a quirky one-off. It was the story of the era: media and communications were converging, and the companies that already controlled networks and transmission assets were sitting on optionality.

Around the same time, another piece of the puzzle was forming elsewhere. Total Peripherals Group was founded in 1986 by Malaysian-born Australian businessman David Teoh. It started as an IT business selling OEM computers, then moved into internet and mobile services as those markets opened up.

In April 2008, SPT merged with Total Peripherals Group in a deal valued at $150 million in cash and $230 million in shares. David Teoh became the largest shareholder and Executive Chairman of the combined group.

This became one of the cleanest examples of the Soul Patts formula in action: find a relentless operator, back them with patient capital, and stay influential without needing to run the business day-to-day. Teoh was aggressive, cost-conscious, and willing to take on much larger incumbents. Soul Patts brought durability—capital and a shareholder base that could think in decades, not quarters.

TPG’s ambitions didn’t stay small for long. On 13 March 2015, TPG announced its intention to acquire iiNet, then Australia’s third-largest ISP, at $8.60 per share—valuing the deal at $1.4 billion. Shareholders approved it on 27 July, and the ACCC cleared it on 20 August 2015. The result was a step-change in scale: TPG became Australia’s second-largest ISP by customer volume, behind Telstra.

Then came the move that reshaped the entire industry. On 13 July 2020, Vodafone Hutchison merged with TPG via a scheme of arrangements. In the process, TPG was renamed TPG Corporation Limited and delisted from the ASX, while Vodafone Hutchison adopted the TPG Telecom name.

Through all of these reinventions—TV station to telecom platform to major industry consolidator—Soul Patts stayed in the story. It holds a 13% equity interest in TPG Telecom, a position that traces all the way back to that NBN Television purchase in the 1980s. As of January 31, the investment comprised around 11% of Soul Patts’ net asset value.

From a regional broadcaster to a meaningful stake in one of Australia’s telecom heavyweights: it took decades, multiple restructures, and the right partner. But it’s pure Soul Patts—quiet entry, patient ownership, and a willingness to let compounding do the work.

VIII. Robert Millner's Era: Fourth Generation Stewardship (1998–Present)

When Jim Millner stepped down in 1998, Soul Patts faced the hard part that breaks most dynasties: the handover. Public markets don’t care about family history. They care whether the next person can protect what works, adapt what doesn’t, and keep compounding.

Robert Millner did exactly that.

As Lewy Pattinson’s great-grandson, Millner became the fourth generation of the family to lead the company, taking the chair in 1998. He wasn’t a lifer groomed in a corporate pipeline. Born on 4 September 1950, he went to Newington College, spent a couple of years as a stockbroker, then disappeared from the city for more than a decade to farm in Cowra, a rural town in New South Wales built on wool and grain.

That detour mattered. Farming forces a particular mindset: you don’t control the weather, you don’t control prices, and if you overextend, the cycle will find you. It’s patient capital with consequences. When Millner came back into the family business in 1984 as a director, he brought that temperament with him.

He’d already been around long enough to know the culture from the inside—on the board since 1984, deputy chairman in 1997, then chairman from 1998 (and from 1999 in formal appointment terms). In 2011, his son Tom joined the board too, another signal that the family wasn’t treating stewardship as a symbolic tradition. They were treating it as the job.

Over Millner’s tenure, Soul Patts’ share price rose dramatically, and the dividend kept climbing year after year. That dividend record became the company’s public fingerprint, but the more revealing part is how he describes the philosophy behind it: “Good people, common sense and patience.”

To Millner, the investment edge isn’t a secret algorithm. It’s personnel and temperament. In 2023, as the company marked its 120th year, he put it plainly: “We have been very fortunate that we have had very good people.” He described a business that stayed conservative, low-key, and unusually close to its employees. “Every morning, when I’m in the office, I walk around to the senior staff,” he said. “We’re common people and we look after and support our employees. It has always been a good place to come to work.”

The outside world, meanwhile, kept trying to put a label on Soul Patts. The one that stuck was inevitable: Australia’s Berkshire Hathaway. Millner doesn’t reject it. “We are very honoured to be spoken about in the same breath as Buffett… We are long-term investors,” he said. Tom adds that Soul Patts, like Berkshire, is a closed-end investment company—no redemptions, no forced selling in downturns, no need to meet withdrawals at the worst possible time.

That structure gives you something priceless in a panic: the ability to wait. “So you can genuinely wait, be patient and, as Buffett would say, be greedy when others are fearful,” Millner said. “Sometimes, we’ve sat on $1 billion worth of cash.”

And through it all—the dot-com crash, the Global Financial Crisis, COVID-19, and the brutal swings of commodity markets—Millner’s core goal stayed remarkably unglamorous.

“I’ve always had it at the back of my mind that I don’t want to be the one that blows the place up,” he said.

That’s not false modesty. It’s the Soul Patts strategy in one sentence: survive, protect the base, and let time do the heavy lifting.

IX. Key Inflection Point #1: The Milton Corporation Merger (2021)

If the Brickworks structure was Soul Patts’ great defensive invention, the Milton merger was its great modern scaling move.

In 2021, Soul Patts absorbed Milton Corporation, one of the ASX’s oldest listed investment companies. Milton brought a multi-billion-dollar portfolio of shares and cash, and suddenly Soul Patts wasn’t just the patient owner of a handful of big strategic stakes. It was also the owner of a broad, blue-chip equity portfolio—an instant widening of the base.

On paper, it looked almost too neat. Two Sydney investment houses, with more than 230 years of operating history between them, lining up a scrip-based deal that would create a group with a market capitalisation a little over $10 billion, based on share prices at the time.

And the overlap ran deeper than geography. Both companies were chaired by Robert D. Millner. Soul Patts already owned around 3% of Milton. Milton, in turn, already held a meaningful position in Soul Patts—SOL shares represented 7.6% of Milton’s assets, according to its portfolio report. In other words: these weren’t strangers coming together. They were already in each other’s orbit.

The real reason it worked, though, was cultural. Milton’s CEO and CIO, Brendan O’Dea, described himself as a dyed-in-the-wool value investor, with a career that included two decades at Citi before joining Milton in 2018. When the merger talks became real, he framed the process as unusually straightforward—because the DNA was so similar, and because both firms were already anchored by the same chairman.

The acquisition completed on September 21, 2021. Along with Milton’s large-cap portfolio, Soul Patts gained an experienced investment team led by O’Dea, and about 30,000 new shareholders. O’Dea became Chief Investment Officer at Soul Patts, and argued the deal gave the group the platform it needed to build the next generation of investments—without compromising the long-term, dividend-first mindset that had defined Soul Patts for more than a century.

Strategically, it solved a real issue. Soul Patts had long been diversified, but relatively concentrated—its identity was tied to big, long-held positions. Milton, founded in 1938, leaned into Australia’s established large caps: the kinds of companies that sit in the core of many portfolios, like the major banks and household-name industrials.

That broader base helped change how the market could see Soul Patts. After the tie-up, Soul Patts’ market cap rose above $12 billion and it entered the S&P/ASX 50, sitting alongside modern Australian stalwarts.

And, crucially, it expanded what was possible next. With larger scale and a wider pool of assets across strategic holdings, large-cap equities, private equity, credit, and property, Soul Patts could go after opportunities that would have been out of reach pre-merger—especially in the private portfolio.

“There’s a real desire on our part to seed the strategic assets of the future, and a lot of that is going to come out of that private portfolio,” O’Dea said.

The Milton merger didn’t change Soul Patts’ personality. It changed its range.

X. Key Inflection Point #2: The $14 Billion Brickworks Merger (2025)

For 56 years, analysts and activists asked the same question: how does a cross-shareholding like this ever end?

In June 2025, they got the answer. Not with a court order. Not with an activist victory. And not with a raider finally forcing the issue. Soul Patts and Brickworks chose to unwind it themselves—by combining into one.

The market’s reaction was immediate. Washington H. Soul Pattinson and Brickworks announced a merger valued at about A$14 billion, and both stocks jumped.

Soul Patts CEO Todd Barlow didn’t dress it up. He said the deal “makes a lot of strategic and financial sense. It simplifies the structure, adds scale, and creates a more investable company.”

That phrasing matters, because it captures the quiet truth everyone had been circling for years: the cross-shareholding had delivered stability and protection, but it also came with baggage—complexity, confusion, and a persistent sense that both companies were harder to value than they needed to be. By 2025, the boards had formed the view that the structure no longer served their best interests, and that a merger was the cleanest way to unwind it.

The implementation wasn’t simple. The merger was structured through two inter-conditional schemes of arrangement—one for Soul Patts and one for Brickworks—under a newly created holding company, TopCo, which would become the merged parent. Under the schemes, a wholly owned subsidiary of TopCo would acquire 100% of the shares in both Brickworks and Soul Patts.

Ownership of the combined group was split roughly as follows: existing Soul Patts shareholders would hold about 72%, Brickworks shareholders about 19%, and new TopCo shareholders about 9%.

Even the funding reflected how much work it took to make the gears mesh. On Monday, 7 July 2025, the companies announced TopCo had secured the required equity funding—total commitments of around A$1.4 billion through the issue of about 34 million new shares. The proceeds were earmarked to repay a significant portion of Brickworks’ debt, settle other liabilities including Soul Patts’ convertible bond, and cover transaction costs. For Barlow, it was a critical checkpoint: “This is a key milestone that gives us maximum flexibility and certainty as we continue to advance the proposed merger,” he said.

By mid-September it was done. Soul Patts and Brickworks traded on the ASX for the last time on September 15, after shareholders voted overwhelmingly in favour of the merger. The deal became legally effective after the companies lodged copies of the Supreme Court orders with the Australian Securities and Investments Commission.

The merged company began trading as TopCo from Tuesday on a deferred settlement basis, then moved to normal settlement on 24 September. After settlement, the merged group was renamed Washington H. Soul Pattinson and Company, and it traded under the SOL ticker.

Barlow’s framing of the strategy was a nod to history, not a rejection of it. “In many ways Soul Patts and Brickworks have evolved together and shared in the capital stability provided by our cross-shareholding over the past 56 years,” he said. In his view, the structure had done its job: it diversified earnings, promoted long-term decision-making, and created significant long-term value. But now, the same objectives could be achieved without the structural knot.

For Soul Patts shareholders, the new shape meant greater exposure to Brickworks’ building products and industrial property assets, including Brickworks’ 50% stake in the Goodman Group joint venture—plus improved financial flexibility for future investments.

It also closed the book on one of the most distinctive corporate arrangements in Australian markets. The cross-ownership first cemented in 1969 was finally gone. The Millner family, long aligned with both businesses, emerged with around an 8% stake in the merged entity.

Soul Patts entered this new chapter with a long record behind it—annualised shareholder returns of around 13% over 20 years, ahead of the broader market—and a familiar playbook: patient capital, long-term partnerships, and a constant eye for value. What changed in 2025 wasn’t the philosophy. It was the structure.

XI. The Modern Portfolio: How Soul Patts Invests Today

After the Brickworks merger, Soul Patts sat atop one of the most diversified portfolios in Australian markets—less a single “business” than a set of engines designed to throw off cash, compound, and keep the dividend machine humming.

Today, the portfolio is organized into six segments: Strategic Portfolio, Large Caps Portfolio, Emerging Companies Portfolio, Private Equity Portfolio, Credit Portfolio, and Property Portfolio.

Brendan O’Dea, who came across with Milton and now runs the investment function, is clear about where the center of gravity has historically been. “We do skew large cap—it’s in this portfolio we hold New Hope, TPG and Brickworks and some others… that’s performed very well and has been the core of SOL’s cash generation and performance for a long time,” he says. The large-cap book—mostly the legacy Milton portfolio—sits at around $2.5 billion and is currently more concentrated than it has been, with roughly 35 positions.

But the more revealing shift is what sits outside listed shares. Beyond the long-term strategic holdings, Soul Patts has close to $3.2 billion spread across private equity, credit, and emerging companies. This is where the group looks least like a traditional listed investment company and most like an incubator—building positions over time in businesses that can become meaningful, not just marketable.

Some of the most distinctive private holdings tell you exactly what kind of investor Soul Patts is. It has been building luxury aged care accommodation in partnership with the Moran family. It’s also been attempting a national roll-up of swimming schools through Aquatic Achievers. In private equity, the holdings span agriculture, Ironbark, Aquatic Achievers, and Ampcontrol.

Ampcontrol, in particular, is emblematic of how Soul Patts thinks about the next era. The company is pushing to develop and supply technology, products, and services for resources, infrastructure, and energy—positioning itself to help customers compete in a net-zero carbon environment.

All up, around 28% of Soul Patts’ assets are now in private markets—useful not just for diversification, but because it’s a part of the world where patient capital faces less competition than it does in crowded public markets. And some of these private businesses have been growing quickly in recent years, including Ironbark and Aquatic Achievers, both of which have delivered strong operating profit growth over the past three years.

This is where O’Dea draws the contrast with traditional fund management. “We’re a team of generalists, and the ability to work across all asset classes and market cap spectrums to find the best ideas… is unique. I think it’s a big driver of our returns,” he says. And, crucially, he points to the structural advantage that underpins the entire model: “We invest shareholders capital, we’re not a fund manager, so we don’t tend to get pressure to put money to work. We’re very happy to wait for what Warren Buffett would describe as ‘fat pitches.’”

XII. The Dividend Legacy: 122 Years Without a Miss

Soul Patts’ dividend record deserves special attention, because it isn’t a marketing line. It’s the clearest expression of what this company is built to do.

Since listing in 1903, Soul Patts has never missed a dividend payment. And over the past 27 years, it has increased its ordinary dividend every single year.

Last Friday, the company announced a final dividend of 59 cents per share. That took the total ordinary dividend for FY25 to 103 cents per share, up 8.4% year-on-year.

In the US, there are well-known labels for streaks like this. A dividend aristocrat is a company that has increased its dividend for at least 25 consecutive years. A dividend king has done it for at least 50. Only a small number of companies have pulled that off in the US—and none in Australia, largely because the ASX’s biggest names tend to be miners and financials, where earnings can swing hard with the cycle.

Soul Patts is the rare exception. It sits right on the doorstep of true “dividend aristocrat” status in an Australian context, and it has grown ordinary dividends strongly since 2000.

So how do you keep that promise through world wars, depressions, financial crises, and pandemics?

First: diversification across cycles. Early on, pharmacy cash flows helped steady the ship. Later, coal earnings powered the portfolio through commodity booms. Telecom rode the digital wave. Building materials benefited from construction cycles. When one engine slowed, another was usually doing the heavy lifting.

Second: conservatism. Soul Patts has never missed a dividend payment, and it has historically avoided the kind of leverage that forces companies into bad decisions at the worst possible time. No looming debt wall means no moment where a board has to choose between keeping creditors happy and keeping its dividend record intact.

Third: cash—kept on hand, intentionally. As Robert Millner put it: “Sometimes, we’ve sat on $1 billion worth of cash.” That cash is defense, because it helps protect the dividend when markets turn. But it’s also offense, because it gives the company the freedom to buy assets when other people are forced to sell.

Even the Brickworks merger was framed through that same lens. The combined group was designed not to dilute the culture, but to preserve it—continuing the dividend-focused approach and the long run of annual increases in ordinary dividends.

XIII. Playbook: The Soul Patts Investment Philosophy

By this point in the story, the pattern is hard to miss. Different decades, different industries, different market cycles—but the same few ideas keep showing up.

At Soul Patts, three principles come through again and again.

Principle 1: Patient Capital

New Hope once summed up the relationship like this: “WHSP holds 60% of our shares, we are controlled by them and they are patient investors and that is definitely a competitive advantage of the firm.”

That patience is structural, not just cultural. As Tom Millner explains: “It is not like a fund where there are redemptions during a downturn. So you can genuinely wait, be patient and, as Buffett would say, be greedy when others are fearful.”

In practice, that means Soul Patts isn’t forced to sell just because the mood changes. When markets crashed in March 2020, plenty of fund managers faced redemption requests and had to raise cash at the worst possible moment. Soul Patts didn’t. Its closed-end structure meant the capital stayed put, which meant the decision-making could stay rational.

Principle 2: Opportunism with Cash on Hand

If you had to boil Soul Patts down to a single word, “opportunistic” would be a strong candidate.

The New Saraji sale in 2008. The Arrow Energy stake that turned into a far larger exit. The Bengalla acquisition when coal sentiment was broken in 2015. These weren’t random wins—they were the result of being willing to act when the window opened.

But there’s a catch: opportunism only works if you have ammunition. You can’t buy distressed assets, or back the right deal at the right moment, if you’re fully invested or over-levered.

Soul Patts tends to keep flexibility—cash, balance sheet capacity, and credibility. And that credibility matters more than most people realize. It’s one thing to go hunting for deals. It’s another when opportunities come to you, because counterparties trust you’ll move, you’ll close, and you’ll be there long after the headlines fade.

Principle 3: Partner with Great People

The third rule is as old as the company: pick great people, and back them for the long haul.

Soul Patts has never pretended it’s the world’s expert in every sector it touches. Instead, it looks for operators it trusts—then supports them with stable capital and a long time horizon. The partnership with David Teoh at TPG is the cleanest modern example, and it’s been immensely profitable for both sides.

Robert Millner, the fourth generation chairman, boils much of it down to management. And internally, the advice gets even simpler. One long-time Soul Patts executive put it this way:

“I've been working at Soul Patts for 20 years, so I've been lucky enough to have the greatest mentor from an investment perspective in Rob Millner. I guess it's pretty hard to distil all of that advice he's given me over the years into one simple thing. But if I was going to summarise it, I'd put it simply as 'don't worry about what everyone else is doing, be calm and patient, and if you make thoughtful decisions for the right reasons they'll prove themselves over time.'”

XIV. Bull Case and Bear Case

The Bull Case

Soul Patts is a genuinely differentiated investment vehicle. The mix of multi-generational family stewardship, a closed-end pool of patient capital, a deliberately diversified portfolio, and a 122-year record of paying dividends creates a set of advantages that’s hard to copy—and even harder to scale quickly.

The 2025 Brickworks merger also fixed the single biggest overhang that had followed the company for decades: structure. When the deal was announced, Soul Patts’ shares jumped 16.4% on the day. Part of that reaction likely reflected the market re-rating a simpler, more “ownable” company—one with better liquidity and fewer structural reasons to apply a discount.

Through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers lens, Soul Patts shows flashes of several durable advantages:

Process Power: The compounding benefit of institutional memory. After more than a century of operating through booms, busts, and regime changes, Soul Patts has developed an investing muscle—how it evaluates people, assets, cycles, and risk—that newer organizations can’t replicate quickly.

Network Economies: Reputation creates its own flywheel. Soul Patts’ standing as a long-term, supportive, credible partner can attract opportunities that don’t run through formal auctions. Having cash, relationships, and a history of closing deals means more deals come to you—then that deal flow reinforces the reputation.

Cornered Resource: The Millner family’s continuity is a real asset. You can hire talent, you can buy a portfolio, but you can’t purchase a century of aligned incentives, accumulated trust, and cultural consistency.

The Bear Case

Coal concentration remains the obvious pressure point. New Hope has been a powerful cash generator, but thermal coal carries long-term carbon risk that isn’t going away. Brickworks’ industrial business is also exposed to cyclical headwinds: weaker demand for bricks, rising costs, and the broader volatility of housing construction.

There’s also a capital markets reality that has nothing to do with operating performance: ESG screens. Many investors simply won’t own coal exposure under any circumstances, which can cap the potential shareholder base even if returns are strong.

Then there’s succession. Robert Millner is 73, so the question of “what comes after” is no longer theoretical. Tom Millner, who has more than 20 years’ experience in investment markets and portfolio management, was a non-executive director of Soul Patts and BKI for over 13 years before leaving the Soul Patts board in December 2023. He was appointed a non-executive director of New Hope on 16 December 2015. Whether leadership transitions from the fourth to the fifth generation—or shifts toward non-family professional stewardship—will test how durable Soul Patts’ culture really is once the current custodians step back.

From a Porter’s Five Forces perspective:

Threat of New Entrants: Low, in the sense that “patient capital with a century-long reputation” can’t be spun up overnight. The model takes time and trust to build.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers/Buyers: Less relevant for a holding company, given it doesn’t sell a single product into a single market.

Threat of Substitutes: High. For many investors, ETFs and low-cost index funds are a compelling alternative: instant diversification, high liquidity, and minimal fees—raising the question of why to choose active capital allocation at all.

Industry Rivalry: Increasing. Competition for deals and attractive assets has intensified, with private equity, sovereign wealth funds, and other long-duration capital providers all chasing the same opportunities.

XV. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you’re a long-term shareholder trying to judge whether Soul Patts is doing its job, you can get lost in portfolio line-items and market noise. But the company’s whole model really boils down to two scoreboards.

1. Pre-Tax Net Asset Value (NAV) Growth

NAV is the simplest way to track whether the underlying portfolio is getting more valuable over time. The share price can move around it—sometimes above, sometimes below—but NAV growth tells you what the investment engine is actually producing.

Soul Patts reported that, at the end of the first half of FY25, its pre-tax NAV was up 4.7% to $12.1 billion.

2. Ordinary Dividend Per Share Growth

The dividend isn’t a nice-to-have at Soul Patts. It’s the contract. The streak of annual increases is central to the company’s identity, and a break would be a loud signal that something fundamental had changed—either in portfolio earnings power or in the board’s priorities.

Since 2000, the ordinary dividend has grown at a compound annual growth rate of 9.8%. That figure excludes $1.05 per share of special dividends paid over the period.

Put together, these two measures tell you almost everything that matters: NAV growth shows whether value is compounding inside the vehicle, and dividend growth shows whether shareholders are actually getting to share in it—year after year.

XVI. Looking Forward: The Fifth Generation and Beyond

As Soul Patts enters its post–Brickworks merger era, the questions get bigger—and more interesting.

The combined group now sits on a portfolio of more than $13 billion. The structure is simpler. Liquidity is better. And the company that spent 56 years wrapped in a mutual ownership knot is, at last, easier to understand and easier to own—without giving up the long-term identity that made it special in the first place.

Even before the merger, Washington H. Soul Pattinson had grown into a diversified investment house with a market cap north of $14 billion and a track record that ranks with some of the world’s most respected capital allocators. The difference now is that the old structural friction is gone, and management has more freedom to shape the next decade.

The current leadership—CEO Todd Barlow, CIO Brendan O’Dea, and Chairman Robert Millner—has been explicit about where they want to take the portfolio: further into private markets, and deeper into the kind of patient, flexible capital deployment that has always defined Soul Patts.

“If we can generate double-digit returns across multi-assets, protecting our capital, protecting our downside, getting some contracted returns and staying liquid, that’s the right portfolio setting.”

Barlow also framed the Brickworks combination as a bet on timing as much as structure. The building products business is cyclical, and he believes the merger landed when that cycle was scraping along the bottom. “We looked at the building products part of Brickworks and thought that we’re bottom of the cycle. We could help them realise some of the uplift from a change in the cycle,” he says.

Meanwhile, the private equity portfolio keeps expanding into the kinds of businesses Soul Patts hopes will become tomorrow’s long-held core positions: electrification through Ampcontrol, financial services through Ironbark, and consumer roll-ups like Aquatic Achievers’ swimming schools. This is the “strategic assets of the future” idea in action—not just buying what’s already big, but patiently building what could become meaningful over time.

That’s the through-line of this entire story. Soul Patts began with two pharmacists who became friends during a bubonic plague outbreak in colonial Sydney. It lived through world wars, depressions, commodity cycles, technological revolutions, and takeover battles. It survived not through constant reinvention, but through patient adaptation—holding tight to a few core beliefs: think long term, avoid leverage that can force your hand, and partner with capable operators.

Now the test is whether that philosophy holds as the company gets larger, as new generations move closer to stewardship, and as markets keep speeding up. History suggests it can—but only if the culture that produced 122 years of uninterrupted dividends stays intact.

In a financial world trained to obsess over quarters, Soul Patts remains proof that patience can be a competitive advantage. The chemist shop Caleb and Washington Soul opened in 1872 is gone. The institution they helped set in motion is still here—compounding, year after year, one considered decision at a time.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music