Sigma Healthcare: From Pharmacist Cooperative to Australia's $34 Billion Pharmacy Powerhouse

I. Introduction: A Century in the Making

Picture this: February 2025, the floor of the Australian Securities Exchange. Mario Verrocchi, a 67-year-old pharmacist who began as an intern in a suburban Melbourne chemist 45 years earlier, rings the opening bell. Beside him stand Jack and Sam Gance, sons of Polish refugees who fled World War II, now among Australia’s wealthiest citizens.

“Two minutes ago, it all changed, and it’s changed forever. So after 50 years of toil, 50 years of grind, we’ve established ourselves as the leaders of this industry.”

What they were celebrating was extraordinary. On February 13, 2025, more than $27 billion of new Sigma shares began trading—one of the largest share issues ever by an ASX-listed company. The deal merged two of Australia’s most recognised healthcare brands into a single wholesaler, distributor, and retail pharmacy franchisor, with a market capitalisation of A$34 billion.

But this wasn’t some overnight success. This moment was forged in crisis.

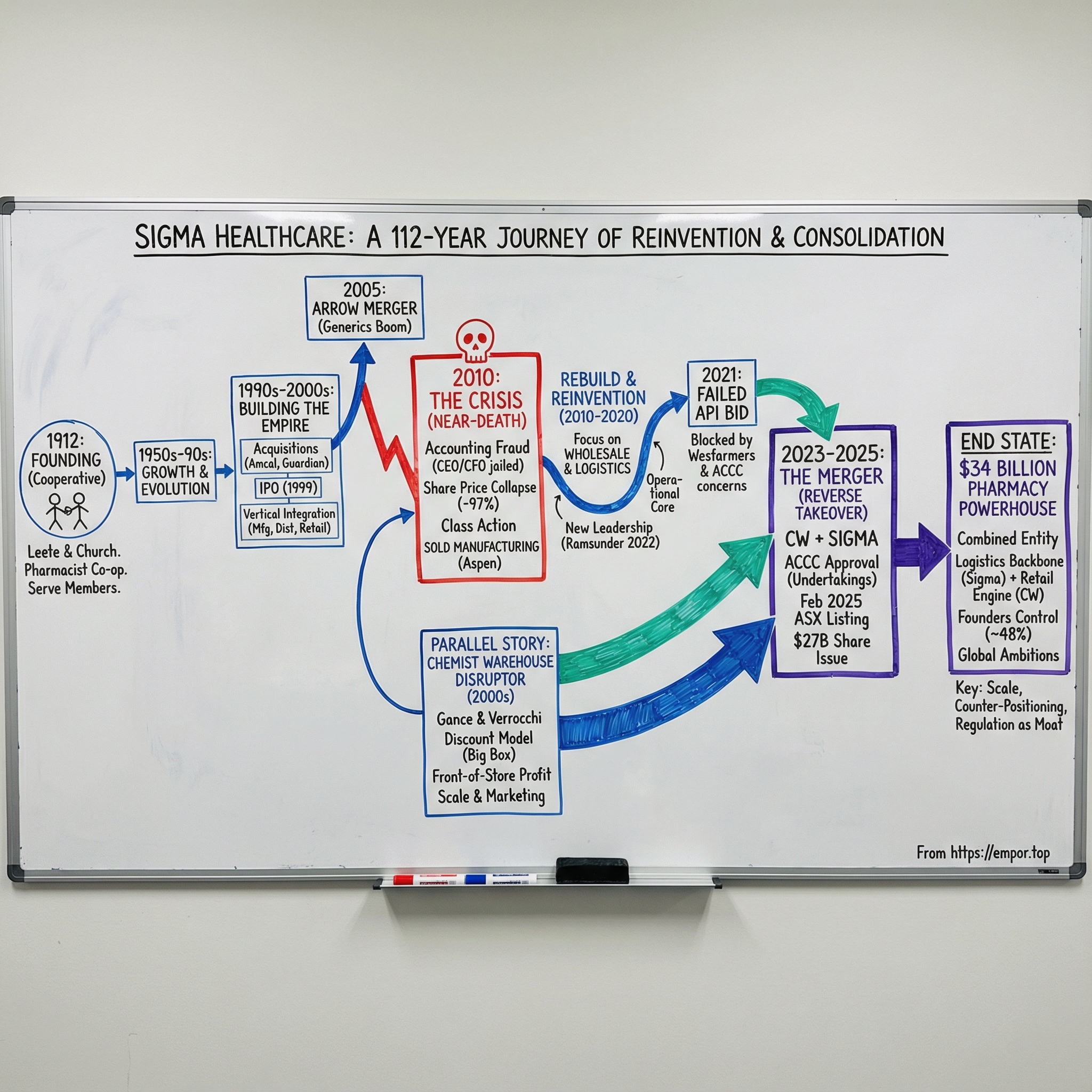

To understand how a 112-year-old pharmacist cooperative became the public-market vehicle for the country’s most disruptive pharmacy chain, you have to follow a story shaped by three forces: Australia’s unusually protective pharmacy rules, a near-death corporate collapse, and a decades-long build by immigrant entrepreneurs who understood how to win on price, scale, and marketing.

The central question is deceptively simple: how did a wholesale distributor survive a catastrophic 2010 implosion that wiped out 97% of shareholder value, then re-emerge 15 years later at the centre of Australia’s biggest pharmacy merger?

The answer starts with the landscape it operated in. Australia’s pharmacy system is heavily regulated in ways that are hard to imagine elsewhere: supermarkets can’t sell prescription medicines; new pharmacies are constrained by location rules; and in most cases, pharmacies are owned by qualified pharmacists. It’s a setup designed to protect community access and pharmacist-owners—and it creates a market where distribution muscle and retail execution matter enormously.

This is a story about essential infrastructure, and about the friction between regulation and disruption. It’s what happens when the country’s most aggressive discount pharmacy retailer links arms with one of its most established wholesalers. For investors, it’s a case study in reinvention and consolidation in a regulated industry—and a live test of whether the combined group can deliver on its promise to reshape Australian pharmacy.

II. The Founding Vision: Birth of a Pharmacist Cooperative (1912-1950s)

In 1912, Melbourne ran on dusty trams, corner chemists, and a supply chain that didn’t feel remotely fair. Retail pharmacists were stuck buying medicines at prices set by wholesalers with all the leverage. Two Melbourne pharmacists, Ernest Holloway Leete and Edwin Thomas Church, looked at the economics and decided there had to be another way.

Leete wasn’t new to the idea. He’d opened his own pharmacy back in 1897, and in 1904 he’d joined a group of commercially minded chemists who tried to sell proprietary preparations under a shared label. That early attempt fizzled. But the lesson stuck: if pharmacists could coordinate, they could take some power back.

So Leete and Church tried again, this time with a plan that was simple and, for its moment, quietly radical. Pharmacists would band together, manufacture their own products, and sell them exclusively through members. The whole point was to bypass what they saw as exploitative middlemen and reduce the cost of wholesale drugs and medicines.

They built it the hard way: one pharmacist at a time. They went looking for “subscribers” among roughly 420 pharmacists across Victoria. Leete and Church mailed a circular—postage paid out of their own £2—asking each recipient to contribute £20. In return, they’d receive £40 of goods, and later, if a company was formed, a £1 share without further payment.

The pitch was bold enough to make people nervous. Only around 80 pharmacists responded. Many of the rest were suspicious, and the muted response rattled some supporters inside the association, who even argued the money should be returned. Leete and Church refused to blink.

Even the name carried intent. They landed on Greek letters, and after debate, chose “Sigma.” By the end of the first year, momentum finally caught: the venture drew more than two hundred subscribers, enough to formalise the whole thing. Sigma Company Limited was registered on 13 October 1913.

That origin story mattered. Sigma didn’t begin as a typical profit-maximising enterprise. It began as a cooperative effort—built to serve pharmacist-members first, and only later shaped by the expectations of shareholders. That tension, between serving the network and serving the market, would keep resurfacing as Sigma grew.

Over the decades, the company broadened its footprint and pushed into new markets, including exports across the Asia-Pacific and the Middle East. It also expanded across Australia, with a particularly active period between 1977 and 1986 as it extended into South Australia, Tasmania, Darwin, and Western Australia. By 1992, on its 80th anniversary, Sigma reported assets of $180 million and group sales turnover of $600 million.

The early Sigma story sets the pattern for everything that follows: pharmacists organising against entrenched power, collective action in a fragmented industry, and the strategic value of controlling the supply chain. What Leete and Church couldn’t have foreseen was just how much Australia’s evolving pharmacy regulation would end up shaping Sigma’s destiny.

III. The Rise of the PBS: Australia's Unique Regulatory Environment

To understand Sigma’s moat—and why the Chemist Warehouse merger was such a tectonic event—you have to understand the strange, uniquely Australian way medicines get paid for, and pharmacies get protected.

At the centre sits the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, or PBS: a federal program that subsidises prescription medicines for Australian citizens and permanent residents, and for some international visitors covered by reciprocal health agreements. It’s related to Medicare, but it isn’t Medicare. Medicare largely deals with services; the PBS is about the drugs themselves, and how Australians get them at a price that doesn’t feel like a second mortgage.

The PBS started small. In 1948 it was a limited scheme: free medicines for pensioners, and a short list—just 139 “life-saving and disease preventing” medicines—for everyone else. Over time, it expanded into something far bigger: the backbone that makes prescription access in Australia feel predictable, reliable, and broadly affordable.

But the PBS doesn’t explain why pharmacies in Australia look the way they do. That comes from a second layer of policy: the Community Pharmacy Agreements.

Since 1990, the federal government has negotiated a series of these agreements with the Pharmacy Guild of Australia, the peak body representing pharmacy owners. In practice, CPAs set the rules of the game for dispensing PBS medicines: how pharmacies are paid, and how the network is shaped. The first agreement, starting in 1991, was aimed at a real problem—too many pharmacies in metro areas, not enough in regional and rural Australia. It introduced a new remuneration framework for PBS dispensing and created incentives to push pharmacy services into underserved communities.

Then there are the rules everyone feels, even if they’ve never heard of a CPA: the location and ownership restrictions.

Australia’s location rules are designed to prevent pharmacies clustering together and to spread access across communities. In general, a new pharmacy must be at least 1.5 kilometres from an existing one. And if a pharmacy relocates, it usually has to stay close—within 10 kilometres of its current site. The effect is subtle but powerful: you rarely see pharmacies stacked door-to-door the way you might in other countries, and many local pharmacies end up with something close to a geographic micro-monopoly.

Layer on ownership restrictions and it becomes even more distinctive. Pharmacies must be operated by a registered pharmacist. And any one person or corporation is capped—no more than five pharmacies.

Supporters argue these rules serve clear public health goals: a more even spread of PBS-approved pharmacies, and therefore access to medicines, across the country. Australia has roughly 6,000 PBS-approved community pharmacies. The Guild has pointed to geospatial research suggesting that in capital cities, about 97% of people live within 2.5 kilometres of at least one pharmacy.

Critics see it differently. The Australian Medical Association has repeatedly called for reform, arguing the ownership and location rules are anti-competitive, push up costs for consumers and government, and can be especially punishing in rural and remote areas where restrictive geography can mean less choice.

For Sigma, and for every wholesaler built around the community pharmacy model, this framework created a peculiar mix of certainty and limitation. The PBS ensured prescriptions flowed through approved pharmacies. The location rules dampened competitive chaos. But growth was capped, and the structure made it hard for large non-pharmacist corporations to vertically integrate and steamroll the sector.

And that’s the irony. The system helped protect the descendants of that 1912 pharmacist cooperative from disruption for decades—right up until a new kind of operator figured out how to play within the rules, and still flip the board.

IV. Building the Empire: Acquisitions, Retail Brands & Going Public (1990s-2000s)

By the 1990s, Sigma had outgrown its cooperative roots. Manufacturing and wholesale distribution were no longer enough. If you wanted real staying power in Australian pharmacy, you didn’t just move boxes for pharmacists—you needed to own the brands that customers actually walked into.

So Sigma went shopping. It picked up Guardian in 1996, then Amcal in 1998. A year later, Sigma Pharmaceuticals Limited listed on the Australian Stock Exchange, stepping into a new era where it wasn’t just accountable to its member network and customers, but also to public-market investors.

The playbook was straightforward: vertical integration. Manufacturing, distribution, and retail banners all under one roof, with margin to be made at every layer. The market loved it. Sigma came to be seen as the premier integrated pharmaceutical company in Australia, and the share price surged—peaking in 2004 as investors bet that consolidation would keep compounding.

Then came the deal that seemed to make Sigma unstoppable: the 2005 merger with Arrow Pharmaceuticals, then Australia’s fastest-growing generics manufacturer. Generics were having a moment. Consumers were getting comfortable with them, government policy was nudging the system in that direction, and Arrow had ridden the wave hard—growing sales from nothing to more than $280 million in just four years. When Sigma moved, it wasn’t subtle. The merger announcement lit up the market, and investors piled into the story.

On paper, it looked like the perfect match. Sigma gained scale in generics, a major position in a fast-growing category, and what appeared to be a manufacturing and supply machine no one could touch. The combined business had around a quarter of the generics market, and Sigma’s pharmaceutical division became the country’s largest manufacturer.

But the seeds of the next chapter were already in the ground. The Arrow merger loaded Sigma with more than $1 billion of goodwill, a byproduct of an all-scrip deal struck at a time when both companies’ share prices had already run up sharply. As their combined value inflated before shareholder approval, Sigma effectively crystallised that premium into goodwill on the balance sheet—an accounting asset that only stays an asset as long as the business performs.

During the boom years, most people didn’t care. But the structure mattered. When conditions turned, that goodwill would become a fuse. And once it started burning, Sigma’s “unassailable” empire wouldn’t just wobble—it would collapse.

V. The 2010 Crisis: Near-Death Experience

The five weeks that began on February 25, 2010 became the darkest stretch in Sigma’s history. It wasn’t just a bad year, or a missed forecast. It was a breakdown in governance that would end in criminal convictions for the CEO and CFO, a shareholder class action, and a share price collapse that permanently reset what the market believed Sigma was worth.

On February 25, Sigma requested a trading halt. It lasted five weeks. When the company finally reappeared on March 31, it did so with its full-year results for the period ending January 31, 2010—and the numbers landed like a car crash.

Sigma reported a net loss of $389 million. It took $424.4 million of goodwill impairments, and posted an underlying net loss of $67.7 million. The market responded instantly: the share price fell from about 90 cents to 47 cents in a single day. The company—then Australia’s biggest drug distributor by market share—also had to renegotiate its loans, a public signal that the balance sheet was under real stress.

And then the story got worse, because this wasn’t simply about tough trading conditions or an overoptimistic acquisition. Allegations emerged of accounting irregularities and preferential deals negotiated with certain pharmacy chains—arrangements that appeared to benefit a few large customers at the expense of smaller independent chemists. The accusations went to the heart of Sigma’s identity: a business built on supplying community pharmacies, now seemingly accused of tilting the playing field, even as it operated its own Amcal and Guardian banners and strained its cash flow.

What prosecutors later alleged was blunt: Elmo De Alwis and Mark Smith arranged for Sigma to buy wholesale drugs at inflated prices, then have the inflated portion returned and booked as revenue. The effect was to falsify Sigma’s books, mislead directors and auditors about how transactions were being accounted for, and overstate income, profits, and inventory. For the full year ended January 31, 2010, Sigma’s publicly reported income was overstated by $15,500,616, inventory by $11,313,224, and profit after tax by $9,599,000.

At the same time, Sigma was also accused of misleading or deceptive conduct in relation to profit guidance issued on September 7 and 14, 2009—guidance that was allegedly provided without a reasonable basis. It was also accused of overstating its first-half result of $32.2 million by between 20 and 35 per cent, and of breaching its continuous disclosure obligations.

The shareholder class action that followed ran for years. It ultimately settled in 2012, with Sigma paying $57.5 million to be distributed among group members. After court-ordered mediation, the parties agreed to settle on October 24, 2012, and on December 19, 2012, the Federal Court of Australia approved the settlement.

Then came the criminal outcome. De Alwis, Sigma’s former managing director and CEO, and Smith, its former CFO, were sentenced in the Melbourne County Court for charges relating to falsifying Sigma’s books and giving false or misleading information to directors and auditors. Both received 12 months’ imprisonment.

For the company itself, survival required radical surgery. In 2010, Sigma restructured and sold its generic drug manufacturing business to South Africa’s Aspen Pharmacare for AUD$804 million—ending an almost 100-year manufacturing legacy. The divested pharmaceuticals division included generic brands, over-the-counter medications, the Herron brand, ethical products, medical products, and the manufacturing operations.

This wasn’t a tidy portfolio optimisation. It was an emergency sale. Sigma effectively sold its heritage—the manufacturing capability that had traced back to the cooperative’s earliest days—to pay down debt and stay alive. The old “vertically integrated Australian pharma champion” was gone. What remained was a wholesaler and distributor.

The share price tells the rest of the story. From highs above $12 in 2004, Sigma fell to 32 cents by 2011—a 97% collapse that erased billions in shareholder value. For shareholders who had bought into the 2009 rights issue at around $1.02, it was brutal.

And yet, buried inside the wreckage was a strange kind of clarity. Stripped of manufacturing complexity and financial engineering, Sigma was forced back to its most fundamental role: moving medicine reliably through Australia’s pharmacy network. The question was no longer whether Sigma could dominate every layer of the value chain. It was whether new leadership could rebuild trust—and turn “just distribution” into the kind of essential infrastructure the system couldn’t function without.

VI. The Chemist Warehouse Disruptor: A Parallel Story

While Sigma was fighting for survival, a very different kind of pharmacy business was taking shape in Melbourne’s suburbs—one built not on tradition, but on speed, scale, and unapologetic discounting.

Jack and Sam Gance were the sons of Polish parents who fled to Russia during World War II, then moved to Paris, and eventually Australia. They both studied pharmacy at university, and in 1972—newly graduated—they pooled their savings to buy their first pharmacy in Reservoir, in Melbourne’s north.

But pharmacy wasn’t the only arena where they proved they could build a brand. In the 1970s and 80s, the brothers launched consumer names that became fixtures in Australian retail: Le Specs, Le Tan, and Australis. In 1976, they established a sunglasses, perfume, and suntan lotion business—Le Specs and Le Tan—and in 1991 they sold those brands to focus fully on what would become their real empire.

The third cornerstone arrived in 1980. Mario Verrocchi had just finished his pharmacy degree when the Gances hired him as a trainee. They’d opened a store in a neighbourhood full of Italian migrants and needed someone who spoke the language—an early sign of the practical, opportunistic way they approached growth.

By the late 1990s, the team had expanded to three locations. Then they made a pivotal break: they left the Amcal chain in 1997 and launched their own banner, My Chemist. It was a step away from the established order of Australian pharmacy—and toward something much more disruptive.

That disruption hit full force in 2000. Jack Gance and Verrocchi founded Chemist Warehouse and opened the first store in Melbourne. They were joined by Sam’s son, Damien Gance, also a qualified pharmacist. Together they ran a simple, almost reckless thought experiment: what happens if we drop the price on everything by 25%?

It only worked if the stores became monsters.

The logic went like this: if a pharmacy could do the kind of turnover usually reserved for major retailers, the efficiencies would compound—rent, labour, buying power, marketing. Discounting wouldn’t kill the business; it would feed it. But the risk was existential. If the volume didn’t show up, the maths wouldn’t just look bad. They’d go broke.

This was the key shift: Chemist Warehouse was designed to make its money where traditional pharmacies didn’t. Around 70% of its profit came from front-of-shop items—sunscreen, toothbrushes, make-up, vitamins—products you could also buy in Coles or Woolworths. The average community pharmacy leaned much more heavily on prescriptions. Chemist Warehouse flipped that ratio on purpose.

It was strategic genius. Prescription margins were regulated and relatively thin. Front-of-store products offered far more room to manoeuvre—on pricing, promotion, and scale. So Chemist Warehouse competed ferociously in categories like cosmetics, fragrances, and baby formula, pulling customers in with discounts and using prescriptions as repeat, anchor traffic.

To grow within Australia’s tight pharmacy ownership and location rules, Chemist Warehouse also leaned on a complex franchise structure—one that allowed it to effectively “control” hundreds of pharmacies while staying inside the formal limits on how many stores a single owner can operate. The model was widely thought to require minimal equity investment from individual pharmacists, who then agreed to group-wide trading terms.

Then came international expansion. Chemist Warehouse opened its first New Zealand store in 2017, entered Ireland in 2020, China in 2021, and the United Arab Emirates in 2024.

And through all of this—the discounting, the scaling, the rule-bending sophistication—Chemist Warehouse maintained a long commercial relationship with Sigma. The two had been intertwined for decades. In hindsight, that matters as much as any store opening: the disruptor and the establishment weren’t strangers. They were long-time partners, and that relationship would become the foundation for the merger that finally remade Australian pharmacy.

VII. The Wilderness Years & Reinvention (2010-2020)

After the 2010 collapse, Sigma entered a long stretch of corporate wilderness. There was no single fix, no quick win, no triumphant comeback quarter. Just a stripped-down company trying to earn back trust—pharmacy by pharmacy, investor by investor—while the industry around it kept getting tougher.

New management inherited something far simpler than the old Sigma empire, and far more fragile. Manufacturing was gone. What remained was wholesale distribution, a set of retail franchise brands, and the one asset that still mattered no matter what happened to the share price: the ability to move medicines and healthcare products across Australia, reliably and at scale.

The rebuild had to be practical, and it showed up in targeted deals. In March 2014, Sigma acquired the healthcare product wholesaler and distributor Central Healthcare Services for $24.5 million. Six months later, it bought the Queensland-based Discount Drug Store banner for $26.7 million, adding another growth engine to its network—around 120 pharmacies under the DDS brand.

By 2017, Sigma was also looking beyond the traditional community-pharmacy model. With changes to how pharmacists were paid under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme putting pressure on the sector, Sigma diversified into services that were becoming increasingly essential—especially in aged care. That year it acquired Medication Packaging Systems (MPS), described as Australia’s largest provider of dose administration services to the aged care sector and community pharmacy patients.

Then came a symbolic line in the sand. On 3 May 2017, Sigma’s board and shareholders voted to change the company’s name to Sigma Healthcare Limited, and the ASX ticker shifted from SIP to SIG. The message was clear: this was no longer a manufacturer trying to look like a consumer pharma champion. It was positioning itself as healthcare infrastructure—distribution, support, and services that sit underneath the system.

That positioning only worked if the infrastructure was real. Sigma leaned hard into logistics, investing heavily in distribution centres and warehousing technology, including automated picking systems. By this stage, it was running a national network of 14 distribution centres, managing the end-to-end flow of more than 15,500 products and delivering over 360 million units a year to pharmacies around the country. It was the unglamorous work that patients never see—but the kind of capability the entire pharmacy network depends on.

COVID tested that foundation, and it forced Sigma into another trade-off: stability versus liquidity. In 2020, the company announced it had sold the land and buildings for its distribution centres in Queensland and New South Wales, then leased the facilities back for an initial term of 15 years. The move raised capital while keeping the wheels turning—an option that made sense in a crisis, and also a reminder that Sigma was still operating with balance sheet constraints. The properties were valued at approximately $172 million.

By the end of the decade, Sigma had become something very different from the company that blew up in 2010. It was no longer a scandal-plagued manufacturer with an overextended strategy. It was a focused wholesaler, franchisor, and logistics business with a rebuilt operational core. The stock was still weighed down by history—but the platform was in place.

What Sigma didn’t have yet was a catalyst. And in 2021, it went looking for one.

VIII. The Failed API Bid & Wesfarmers Enters the Scene (2021-2022)

By 2021, Sigma’s options were narrowing. The turnaround had rebuilt the engine, but not the scale. If Sigma wanted to meaningfully change its trajectory, it needed a step-change—something bigger than incremental franchise wins and operational tightening.

So Sigma went hunting for a deal.

The target was Australian Pharmaceutical Industries, or API: another heavyweight in the pharmacy ecosystem, and the owner of retail brands like Priceline, Pharmacist Advice, and Soul Pattinson Chemists. Sigma proposed a merger valued at AUD$773.5 million, a move that would have stitched together two major distributors and two rival stable of banners into a single, much larger platform.

On paper, it was the kind of consolidation play that made strategic sense. In practice, it ran straight into two immovable forces: the regulator, and a far bigger competitor with its own plan.

From the start, analysts warned the ACCC would have a hard look at the deal. Morningstar pointed out that a combined Sigma/API would control an enormous share of pharmacy distribution—large enough to trigger déjà vu. The ACCC had blocked a Sigma–API merger back in 2002 on competition grounds, and the concern was that history was about to repeat. Sigma’s network included brands like Amcal, Guardian, and PharmaSave; API brought Priceline and Priceline Pharmacy franchises, plus the Clear Skincare network. Put together, it was a lot of market power concentrated in one set of hands.

Then Wesfarmers walked onto the field.

Wesfarmers—the Australian retail conglomerate behind some of the country’s best-known chains—bought a 19.3% stake in API. And it wasn’t subtle about why. It said it wouldn’t support Sigma’s proposal or vote its API shares in favour of it, because Wesfarmers intended to pursue its own acquisition. Sigma’s bid was structured as a scheme of arrangement, which meant it needed at least 75% of votes at a shareholder meeting. With Wesfarmers holding nearly a fifth of the register, Sigma’s path narrowed fast.

In October, Wesfarmers strengthened its hand by buying the stake held by API’s largest shareholder—making Sigma’s job even harder. Sigma called it a “competitive bid process,” but the meaning was plain: it was getting outmuscled. On 5 October 2021, Sigma withdrew its proposal. Chairman Ray Gunston framed it as a rational decision in a shifting economic and transaction environment. Translation: the maths and the politics no longer worked.

The endgame came quickly. On 11 February 2022, the ACCC announced it would not oppose Wesfarmers’ acquisition of API.

For Sigma, losing API was a strategic setback, but it wasn’t existential. The company responded by narrowing its focus. In September 2022, Sigma said it would consolidate its retail brands and put franchise growth weight behind Amcal and Discount Drug Store—fewer banners, clearer priorities, and a tighter story for pharmacy owners.

But the more important move came in leadership.

At the start of 2022, Sigma recruited Vikesh Ramsunder as CEO. Before moving to Australia, Ramsunder had spent 28 years with South Africa’s Clicks Group, including time as Group CEO from January 2019 to December 2021. He wasn’t just a retail executive; he had run pharmacy wholesale, too, serving as Managing Director of UPD—the pharmaceutical wholesaler within the Clicks ecosystem—from 2010 to 2015, where he helped drive an integrated wholesale and distribution strategy.

That experience was exactly what Sigma needed: someone who understood how to make retail and distribution reinforce each other, especially in a regulated market where scale and execution are everything. Under his leadership at Clicks, the group expanded to more than 800 stores and 600 in-store pharmacies, and its market capitalisation grew from R48 billion to R75 billion—even through the disruption of COVID.

Sigma didn’t know it yet, but the failed API bid had cleared the runway. With Ramsunder in the CEO seat, the company was about to enter conversations that would make the API attempt look like a warm-up.

Within months of his arrival, discussions with Chemist Warehouse began—and they would reshape Australian pharmacy.

IX. The Chemist Warehouse Merger: Anatomy of a Reverse Takeover (2023-2025)

In December 2023, Chemist Warehouse announced its intention to merge with Sigma Healthcare via a reverse takeover. It was a structure that caught plenty of people off guard, but it fit the incentives on both sides.

Chemist Warehouse had wanted to list on the ASX for years, with ambitions to build something on the scale of Walgreens in the US. But equity markets had been bruised for a couple of years, and a traditional IPO suddenly looked like the harder path. Sigma, already public, offered a faster on-ramp.

The mechanics were simple, even if the paperwork wasn’t. When the deal completed, Chemist Warehouse shareholders ended up with 85.75% of the ASX-listed combined company, and existing Sigma shareholders kept 14.25%. The transaction was implemented as a scheme of arrangement and included A$700 million in cash for the former Chemist Warehouse shareholders, alongside new Sigma shares that delivered their majority ownership.

From day one, the regulator treated this as a big deal. “This is a major structural change for the pharmacy sector, involving the largest pharmacy chain by revenue merging with a key wholesaler to thousands of independent pharmacies that in turn compete against Chemist Warehouse,” ACCC Commissioner Stephen Ridgeway said.

The ACCC’s concerns were straightforward: Sigma supplied thousands of pharmacies that competed with Chemist Warehouse. In a combined world, would those pharmacies be disadvantaged? And could Chemist Warehouse gain access to sensitive customer and franchise data in ways that undermined competition?

The path through was a set of court-enforceable undertakings. Sigma offered contracted franchisees an exit path, and committed to ring-fencing the data of customers and franchisees from Chemist Warehouse.

On 7 November 2024, the ACCC approved the proposed A$8.8 billion merger. It said it had accepted a court-enforceable undertaking from Sigma under section 87B of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 in connection with the Merger Implementation Agreement. With those protections in place, ACCC chair Gina Cass-Gottlieb said the deal was “unlikely to substantially lessen competition,” and that “there is and will continue to be effective competition at all levels of the pharmacy supply chain, capable of constraining a combined Sigma Chemist Warehouse.”

Then came the final gates: shareholders and the court. Chemist Warehouse’s shareholders voted unanimously in favour on 29 January, and the Federal Court approved the merger on 3 February.

The deal completed days later. On 13 February 2025, the merged group began trading on the ASX. More than $27 billion of new Sigma shares hit the market that morning, making it one of the largest share issues ever by an ASX-listed company. Chemist Warehouse had effectively listed by reverse takeover of Sigma—owner of the Amcal and Discount Drug Store banners—after a 19-month grind through competition scrutiny in Australia’s tightly regulated pharmacy market.

The founders sounded like people who knew exactly how improbable the moment was. “I subscribe to the view that if you wish for something hard enough, it comes true,” Mario Verrocchi said. “We never thought we’d ever get here,” Sam Gance added. “It’s been a wonderful surprise and I think it’s an acknowledgement of the effort of all our team.”

X. The Combined Entity: What Does It Look Like?

Once the deal closed, the story stopped being about a merger and started being about a new shape of power in Australian pharmacy. Sigma and Chemist Warehouse, together, now span the full loop: wholesaling and distribution on one end, retail franchising and marketing on the other.

On the infrastructure side, Sigma remains what it rebuilt itself into after 2010: a full-line wholesaler and distributor. It supplies prescription products, including PBS medicines, plus OTC and front-of-shop items, to more than 3,500 pharmacy customers. It runs a national network of 14 distribution centres, moving a catalogue of more than 15,500 products and delivering over 360 million units each year to pharmacies around the country. And on the retail side, the combined group now supports Australia’s largest franchised pharmacy network: more than 880 franchised pharmacies across Amcal, Chemist Warehouse, and Discount Drug Stores.

If you want the deal logic in one quote, Mario Verrocchi delivered it. “I think the marriage between Sigma and Chemist Warehouse is a very simple one. We’re very good at something, which is retailing, they’re very good at logistics. You put those two things together, and it’s like tying skyrockets to the back of you.”

Management has pointed to around $60 million in synergies, with the expectation that efficiencies won’t stop there. Verrocchi also pointed to momentum already underway: “We have executed well on the commitments we made in September to deliver sustained growth through new franchise store openings and international expansion while implementing new supply agreements to drive efficiencies. Earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) increased by 35 per cent and margins expanded by 400 basis points.”

The governance is just as telling as the operating plan—and it reflects the reality that this was a reverse takeover. Chemist Warehouse co-founders Jack Gance, Damien Gance, and Mario Verrocchi were elected as directors of Sigma Healthcare, alongside Danielle Di Pilla, a veteran Chemist Warehouse pharmacist. Vikesh Ramsunder continued as CEO and managing director of Sigma Healthcare in the merged group.

Ownership underscored the same dynamic. The three founders collectively held roughly 48% of the combined entity. The Gance and Verrocchi families had long been deeply embedded in the store network; taken together, they owned or partly owned 180 of the chain’s Australian pharmacies at the end of last year.

And with the listing, that private-company value became public in a very visible way. The merger propelled the founders up the wealth rankings. In 2024, the AFR Rich List estimated Sam and Jack Gance at $3.92 billion, ranking them 32nd. Verrocchi, who had started as an intern and rose to CEO, was estimated to be worth at least $2.5 billion after the merger.

What they wanted to do next was even bigger than Australia. Jack Gance described ambitions to become a global pharmaceutical and retail giant, pointing to the existing footprint in New Zealand, Ireland, China, and Dubai—and said the company was looking at the United States. “With the strength of Sigma with their supply chain I think we can go pretty well anywhere. Obviously, the American market is one we are looking at. It is a very difficult market.” Verrocchi added that there were ambitions to double Chemist Warehouse’s existing Australian network of 600 stores.

XI. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

If you want to understand the Sigma–Chemist Warehouse juggernaut, you can’t just look at size. You have to look at the shape of the battlefield: what keeps competitors out, who holds leverage, and what advantages might actually endure.

Porter's Five Forces:

1. Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Australia doesn’t make it easy to start a pharmacy from scratch. Ownership is restricted to registered pharmacists, a new pharmacy generally can’t open within 1.5 kilometres of an existing one, and a single person or corporation is capped at owning five pharmacies. There are also rules that limit direct physical connections between a pharmacy and a supermarket.

Those restrictions don’t just slow entrants—they protect incumbents.

Then there’s the other half of the moat: distribution. Sigma has spent heavily in recent years on distribution centres and warehousing technology to deliver market-leading logistics across the healthcare supply chain. Building a comparable national network would take years, deep operational know-how, and a massive capital commitment.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Drug manufacturers need wholesalers to reach a geographically spread population. And for many categories—especially generics—competition and PBS “price disclosure” have steadily squeezed pricing power.

The PBS itself also shapes the negotiating landscape by setting reimbursement benchmarks. In July 2007, the federal government introduced brand premiums for medicines where cheaper generic alternatives were available. Pharmacists can substitute generics when the Schedule of Pharmaceutical Benefits flags the brands as interchangeable. The system nudges volume toward lower-cost options, which in turn limits how much leverage suppliers can exert.

That said, large global manufacturers with exclusive products and scale—think names like CSL and Pfizer—still have some negotiating power.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

Pharmacies aren’t locked into a single wholesaler. The ACCC’s investigation highlighted active competition for pharmacy customers, and it found that retail pharmacies do switch wholesalers.

That point was central to the ACCC’s comfort with the merger. Its view was that the combined Sigma–Chemist Warehouse would still face meaningful constraints from other wholesalers and from rival retail models across the supply chain.

4. Threat of Substitutes: LOW (prescriptions) / HIGH (front-of-store)

For PBS prescriptions, there’s no real substitute channel. Government-subsidised medicines have to be dispensed through approved pharmacies.

But front-of-store is a different story. It’s open season: supermarkets and other non-pharmacy retailers sell many of the same health and wellness products, and they remain major sources of competition for categories Chemist Warehouse relies on.

5. Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a hard, competitive industry. The major wholesalers fight for accounts. Wesfarmers’ acquisition of API added another heavyweight to the landscape. And Chemist Warehouse’s discount playbook pushed pricing pressure deeper into the system, compressing margins and forcing everyone to respond.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis:

1. Scale Economies: STRONG

Sigma’s distribution footprint is the kind of advantage that’s invisible—until it isn’t there. Its network of 14 distribution centres moves a catalogue of more than 15,500 products and delivers over 360 million units each year. The bigger the flow, the cheaper each unit becomes to handle and ship. That is scale economies in their purest form.

2. Network Effects: MODERATE

There’s a modest flywheel in franchising: more stores build brand familiarity, expand promotional reach, and improve negotiating leverage with suppliers. But pharmacy retail is still fundamentally local. This isn’t a winner-take-all platform business.

3. Counter-Positioning: STRONG

Chemist Warehouse won by playing a game incumbents couldn’t easily copy.

Traditional community pharmacies typically rely more on prescriptions. Chemist Warehouse built a discount, big-box format that made front-of-store categories—everything from vitamins to cosmetics—feel cheaper and more compelling, and then used that traffic to build volume at scale.

For many incumbents, matching that approach isn’t just difficult; it risks breaking their economics. That inability to respond without self-harm is what counter-positioning looks like when it works.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE

Franchise agreements create stickiness, but not permanence—and that mattered during merger review. The ACCC undertaking directly addressed concerns about being “trapped,” with Sigma offering contracted franchisees an exit path.

5. Cornered Resource: STRONG

Regulation functions like a scarce resource. Location rules and ownership restrictions don’t just create friction for new entrants; they effectively protect the position of existing pharmacies that already have approved sites and compliant ownership structures.

6. Process Power: MODERATE

Sigma has spent the past few years tightening the unglamorous core of the business: warehouses, distribution centres, and the processes inside them. As the company put it, warehouse and logistics have been a major focus, and the goal was to optimise newer distribution centres to meet current and future demand.

Operational process advantages—automation, throughput, accuracy—rarely show up in a billboard slogan. But over time they can create service levels competitors struggle to match consistently.

7. Branding: STRONG

Chemist Warehouse is one of the most recognisable brands in Australian retail pharmacy, and Amcal carries decades of consumer trust. In a category where customers are buying personal, recurring health products, brand matters—and these are two of the biggest names in the country.

Key Investment Metrics to Monitor:

For long-term fundamental investors, three KPIs matter most:

- Same-store sales growth - the cleanest read on underlying retail health

- Wholesale availability rate - currently at 93%, a proxy for service reliability and supply chain execution

- Franchise network expansion - net new store openings as a signal of growth and franchisee confidence

XII. Myth vs. Reality: Fact-Checking the Consensus Narrative

Myth #1: The merger creates a monopoly in Australian pharmacy

Reality: The combined entity is big, but it isn’t the only game in town. The ACCC’s view was clear: “the proposed merger is unlikely to substantially lessen competition” at a national or local level, because other pharmacies and non-pharmacy retailers will keep competing much as they already do. EBOS (owner of TerryWhite Chemmart), Wesfarmers-owned API (including Priceline), and thousands of independent pharmacies all remain in the market, still fighting for the same customers.

Myth #2: Sigma was always destined for this merger

Reality: Nothing about Sigma’s path was inevitable. In 2010, it was staring at an existential crisis: a class action settlement, criminal convictions for senior executives, and a 97% share price collapse. This wasn’t a company “positioning” for a transformational partnership. It was a company trying to survive. The merger only became possible after years of restructuring, rebuilding credibility, and reinvesting in the operational backbone of the business.

Myth #3: Chemist Warehouse succeeds by “undercutting” prescription prices

Reality: PBS prescription pricing is tightly regulated, which limits how much anyone can discount the script itself. Chemist Warehouse’s advantage comes from a different playbook: winning customers with aggressive pricing and marketing on front-of-store products. Around 70% of its money comes from items like sunscreen, toothbrushes, and make-up—categories where price competition is real, repeatable, and visible. By contrast, the average community pharmacy earns a greater share of its profit from prescriptions.

Myth #4: Regulatory deregulation threatens the investment thesis

Reality: Calls for reform aren’t new. For almost 25 years, there have been reviews, reports, and recommendations arguing that Australia’s pharmacy rules are outdated and anti-competitive, limiting competition and affecting access to medicines. But the political reality has been remarkably consistent: meaningful deregulation hasn’t happened. The Pharmacy Guild’s lobbying power remains formidable, and no government has been willing to take on the status quo in a way that truly rewrites the rules of the industry.

XIII. Bull and Bear Cases

The Bull Case:

At its best, this merger is the kind of move that only comes along once in a generation: a major consolidation in a heavily regulated industry where the barriers to entry are real, and where scale can compound for decades.

The core logic is clean. Chemist Warehouse brings the retail engine—merchandising, marketing, store execution. Sigma brings the pipes—distribution centres, systems, and a national logistics backbone. Put together, you get a business that can win at the shelf and deliver at the back dock.

There’s also genuine optionality. Chemist Warehouse already has a footprint outside Australia—New Zealand, Ireland, China, and Dubai—and the merged group now has public-market currency and a larger platform to keep pushing.

And the ambition, at least, isn’t hidden. “If you look at Coles and Woolies they have 900 to 1000 retail spots, we would probably follow a similar projection,” Verrocchi said.

Finally, the same regulation that frustrates reformers is a stabiliser for incumbents. The PBS and the broader pharmacy framework make demand feel more predictable than in many retail categories. With an ageing population, prescription volumes should continue to rise over time, and the PBS safety net makes it hard for the system to be completely disintermediated.

The Bear Case:

The downside case starts with governance—because the merger didn’t just combine two businesses, it brought a very particular ownership culture onto the public market.

As Helen Bird, a senior lecturer at Swinburne Law School in Melbourne who specialises in corporate governance, put it: “It was a family-and-friends business model.” In her view, that structure helped Chemist Warehouse navigate laws restricting how many pharmacies a single person can operate.

Post-merger, the founders control roughly 48% of the combined entity. That’s not a detail; it’s the control structure. And it raises a hard question for minority shareholders: in practice, how much authority can the CEO really have if the Verrocchi and Gance families can effectively dictate the outcome of major decisions? The risk isn’t just whether the company follows the rules of public-company governance on paper, but whether it embraces them in substance.

Then there’s regulation—usually a moat, but not guaranteed forever. Reform has been slow historically, but it can’t be ruled out, and global examples show what happens when digital players are allowed to take a real run at pharmacy. Amazon’s pharmaceutical ambitions in the US are the reminder here: if regulations change, disruption can arrive faster than incumbents expect.

And finally, there’s execution. Integrating two very different cultures—a 112-year-old cooperative-turned-wholesaler and a hard-charging discount retailer—creates real operational and organisational risk. The synergy story may be credible, but it still has to be delivered.

XIV. Conclusion: Essential Infrastructure for a Regulated Future

The Sigma–Chemist Warehouse story is, at its core, a study in how regulated markets really work—and what it takes to win in them.

First: a near-death experience can turn into an advantage. Sigma’s 2010 crisis forced it to amputate the parts of the business that had made it feel like an “integrated pharma champion,” and double down on the unglamorous core: distribution. Selling manufacturing was painful and symbolic, but it left Sigma with the thing Chemist Warehouse ultimately needed most: a national logistics platform built to keep pharmacies stocked.

Second: regulatory moats protect you, and they trap you. Australia’s pharmacy rules gave Sigma breathing room during its most vulnerable years, because the system still needed wholesalers and still channelled prescriptions through approved pharmacies. But the same framework also capped growth, shaped incentives, and made the industry’s power structure unusually resistant to change.

Third: patience is a strategy in industries like this. The Gance family and Mario Verrocchi spent decades compounding Chemist Warehouse inside the constraints—long before they ever touched public markets. They’ve talked about building for the long run, even a hundred-year horizon. That mindset is the opposite of quarterly optimisation, and it’s part of why this merger is so fascinating: a private, founder-driven machine now living under public-market rules.

Fourth: the most valuable assets are often the ones investors ignore. For years, Sigma traded like a damaged company with an ugly past. What the market struggled to price was the thing Sigma had quietly built back up: a logistics network that’s hard to replicate and easy to take for granted—right up until it fails.

Now the combined company is the largest pharmacy network in Australia by market capitalisation, sitting inside a regulatory environment that has been remarkably durable for decades. Demographics help too: an ageing population is a steady tailwind for prescription volumes.

So the real questions from here aren’t philosophical—they’re operational. Can the group actually deliver the synergies it’s promised? Do governance concerns become real constraints, or just noise? And can a founder-led retail culture adapt to the disciplines—and scrutiny—of life as a public company?

Those answers will decide whether this 112-year-old pharmacist cooperative, now fused with Australia’s most aggressive pharmacy retailer, becomes a Southern Hemisphere analogue of Walgreens—or whether control dynamics and execution risk cap the upside.

What’s already undeniable is the arc. Sigma began with two pharmacists in 1912 trying to escape the grip of powerful wholesalers. More than a century later, it ended up as the listed backbone of a $34 billion pharmacy powerhouse. The next chapter is now being written in real time.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music