Sonic Healthcare: The Doctor's Diagnostics Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

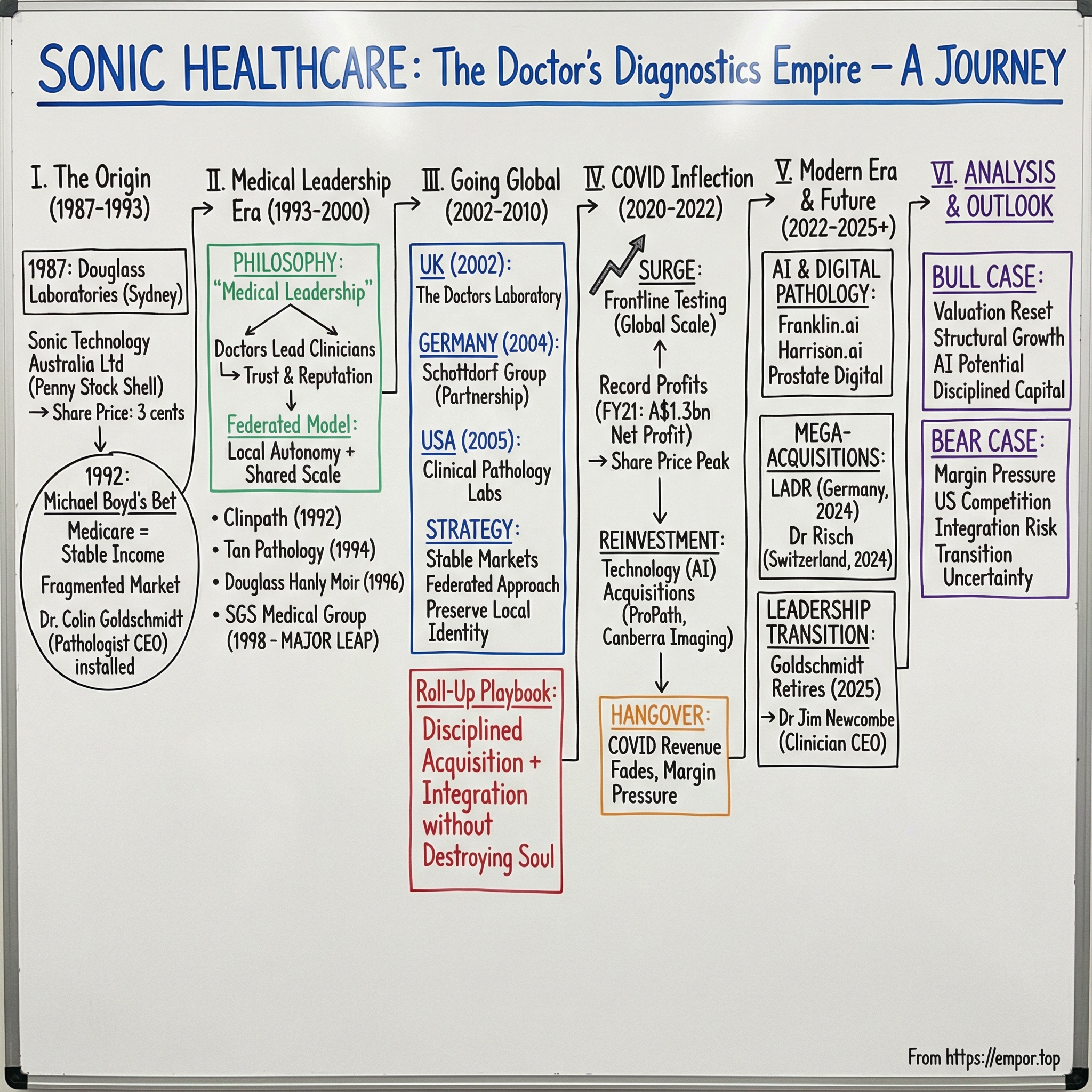

Picture a pathology lab in Sydney’s northern suburbs in 1987. While markets around the world were convulsing and Australia was still maturing into a modern capital market, a small, unremarkable company called Sonic Technology Australia Ltd quietly listed on the Australian Stock Exchange. Within a few years, its share price sank to three cents. The kind of stock most investors don’t even bother to look up twice.

Now jump ahead almost four decades. That same entity, re-made and renamed Sonic Healthcare, sits in the S&P/ASX 50 and has become the largest medical laboratory provider in Australasia and Europe, and the third largest in the United States. In other words: from suburban obscurity to the top table of global diagnostics.

That’s the question we’re here to answer: how did a struggling penny stock in Sydney’s suburbs turn into a global diagnostics powerhouse?

The official arc is straightforward. Since its 1987 listing, Sonic grew from a single laboratory, Douglass Laboratories, into a market leader through a mix of steady organic expansion and relentless acquisition of high-quality practices. But the real story is why those acquisitions worked, over and over again, in an industry where roll-ups often fall apart.

Sonic didn’t win by treating healthcare like a spreadsheet. It built a culture around Medical Leadership, a simple but unusually powerful idea in modern corporate medicine: doctors and experienced clinicians should lead, and medical standards should set the tempo for the business, not the other way around. That philosophy became a magnet for great practitioners and, over time, a moat competitors struggled to copy.

So this is where we’re going. We’ll unpack the roll-up playbook and the discipline it takes to integrate deal after deal without losing the soul of the organization. We’ll follow Sonic through the COVID surge, the windfall it created, and the hangover that followed. And we’ll end in the present, with the next big shift already arriving: AI, digital pathology, and what happens when diagnostics starts to look like software.

Today, Sonic’s footprint stretches across Australasia, Europe, and North America. It’s not just big; it’s embedded. The business is built on deep ties with over 100,000 referring doctors, on the work of more than 2,200 pathologists, radiologists, and other clinicians, and on a federated culture that holds together labs and practices that, on paper, shouldn’t feel like one company—from Texas to Hamburg.

And if you’re trying to figure out what Sonic is in the post-COVID world—a durable compounder at the right price, or a great business facing structural margin pressure—there’s only one place to start.

Back at the beginning, with a young accountant, a pathologist who had just qualified, and a failing listed company that almost everyone else had already written off.

II. The Origin Story: From Penny Stock to Purpose (1987–1993)

The Shell Company Era

Sonic’s story begins with a listing on the Australian Stock Exchange in April 1987, under a name that now feels like a misdirect: Sonic Technology Australia Ltd. Underneath, its real roots were in Douglass Laboratories, a pathology practice in Sydney’s northern suburbs.

And that mismatch mattered. This wasn’t a purpose-built healthcare company marching confidently into a growing market. It was, in reality, a struggling listed mining outfit looking for a new way to make money—one that had bought Douglass Laboratories in 1987 as part of that search. That same year, a young pathologist named Colin Goldschmidt joined the firm.

The early years were rough. By 1990, the share price had sunk to three cents. A stock so cheap it was effectively a write-off—especially compared to where Sonic shares would trade decades later, in the tens of dollars. The gap between those two realities is so large it almost sounds like myth.

But the inflection point wasn’t a new machine, a breakthrough test, or a lucky contract.

It was a decision by a 27-year-old accountant.

Michael Boyd's Vision

In 1992, Michael Boyd looked at Australian pathology and saw what the market hadn’t priced in: Medicare funding turned diagnostic testing into a remarkably dependable business. So he made a move that, at the time, looked wildly out of proportion to the company’s circumstances.

Boyd put in $1 million to buy 14% himself, and raised a total of $4 million—much of it from his father-in-law, Barry Patterson. Together, that gave them control of 23% of the company.

The logic was straightforward, almost obvious in hindsight. Medicare created a stable, predictable stream of payment for pathology services. Australia’s population was aging, which meant demand would keep rising. And the industry was fragmented, full of independent practices with strong local reputations but limited scale—exactly the kind of landscape where a disciplined consolidator could thrive.

Boyd’s bet was also a statement about how this roll-up would have to be built. He understood something essential about medicine: doctors don’t want to be managed like factory supervisors. Pathology isn’t a widget business. The product is judgment, delivered by highly trained professionals operating under a deeply rooted ethical code. If Sonic wanted to consolidate, it needed medical authority at the center of the company, not just financial control.

So Boyd installed Colin Goldschmidt as CEO—and Sonic’s trajectory changed. The business shifted from being a listed shell with a side hustle in healthcare into a pathology company with a clear mission, growing more profitable and steadily earning the market’s respect.

Boyd’s ownership position, anchored by that early capital and control group, gave Sonic the freedom to pursue a long-term strategy without being jerked around by short-term market pressure. Over time, that original $4 million stake would become famously valuable—often cited as having grown into the hundreds of millions within little more than a decade.

But the deeper takeaway isn’t the headline return.

It’s that Sonic’s foundation wasn’t financial engineering or a slash-and-burn integration play. It was a clear-eyed view of the economics of Medicare-funded pathology—and the humility to put a medical professional in charge, and let medical principles set the standard for how the company would grow.

III. The Goldschmidt Era & Medical Leadership Culture (1993–2000)

Birth of the "Medical Leadership" Philosophy

By 1993, Colin Goldschmidt was no longer just the young pathologist inside Douglass Laboratories—he became Managing Director of the group. Two years later, in 1995, the company formally reintroduced itself to the market as Sonic Healthcare Limited.

Goldschmidt’s biography matters because it explains his instinct. He was a histo-pathologist who had qualified shortly before joining Douglass, and he’d seen how quickly “corporate management” could collide with medical professionalism. He had studied medicine at Wits before migrating to Sydney, where he qualified as a pathologist. And as Sonic grew into a listed company with international pathology operations and tens of thousands of employees, he was determined the business wouldn’t lose the plot.

So he put words around a principle that would become Sonic’s operating system: Medical Leadership. Not as a slogan, but as a statement about who gets to make decisions and what the company is for. In Sonic’s framing, it wasn’t just a nice-to-have; it was the unifying component across divisions and geographies, rooted in the “special complexities, obligations and privileges” of medical practice.

And Sonic tried to make that real in structure, not just speeches. The commitment showed up at the top: the global CEO was a pathologist, and several Board members were doctors too. That sent a clear signal to every practice Sonic acquired: this was a consolidator, yes—but one that would be led by clinicians.

Medical Leadership also shaped how Sonic competed day-to-day. Goldschmidt argued that beyond the science, pathology is a service business: referring doctors—and the patients behind them—care about responsiveness, relationships, and trust. That meant Sonic couldn’t behave like a typical roll-up that centralizes everything and strips out “redundant” local decision-making. Instead, Sonic leaned into a federated model. Practices kept meaningful autonomy, local identity stayed intact, and medical leaders remained embedded in their communities.

That was the differentiator. In healthcare, reputation travels by word of mouth between clinicians. The “customer” isn’t a retail shopper—it’s the doctor deciding where to send their patient’s specimen. If you break local trust, you don’t just lose volume. You lose the franchise.

The Australian Consolidation

With that philosophy set, Sonic moved quickly, but with a clear pattern: buy high-quality practices, keep what makes them great, then add scale behind the scenes.

The build started early. In 1991, Douglass Laboratories opened a pathology branch in Adelaide. In 1992, Sonic acquired and merged with Clinpath Laboratories. In 1994, it acquired and merged with Sydney’s Tan Pathology. In 1995, it acquired the Adelaide practice Pathlab and folded it into Clinpath.

Then came a burst of consolidation in New South Wales and beyond. In 1996, Sonic acquired Hanly Moir Pathology and Barratt and Smith Pathologists in NSW, plus Canberra-based Barratt Smith Moran Pathology. Douglass merged with Hanly Moir to form Douglass Hanly Moir Pathology. Around the same time, Sonic Clinical Trials began operating from the Douglass Hanly Moir site at North Ryde.

By 1996, Sonic Healthcare had become Australia’s largest pathology group. The roll-up wasn’t just working—it was compounding.

Over the decade, the numbers reflected what the strategy was doing on the ground. Between 1992 and 1999, sales grew from $12 million to $175 million. In a Medicare-funded, fragmented industry, Sonic had found a way to scale without destroying the very thing it was buying.

But the moment Sonic truly stepped into the big league came with SGS Medical Group. In 1998, Sonic acquired SGS, a collection of major pathology and radiology practices: Sullivan Nicolaides Pathology, Northern Pathology, Melbourne Pathology, operations in Tasmania, multiple labs across New Zealand, and the New Zealand Radiology Group. The deal created the largest diagnostic group in Australasia and marked Sonic’s serious entry into diagnostic imaging.

Goldschmidt later described the acquisition as a defining step: a group with combined revenue of about $300 million that more than doubled Sonic’s size—and, just as importantly, gave it geographic breadth it didn’t previously have.

The SGS acquisition also cemented Sonic’s template for growth. Buy practices with strong local reputations. Keep their identities and leadership. Plug them into a larger system with shared infrastructure and standards. And insist that the culture stays medical first.

That combination—philosophy, execution, and an unusually disciplined respect for how medicine actually works—didn’t just make Sonic the leader in Australia. It set the company up for the next phase: taking this model overseas, and seeing if it could survive contact with entirely different healthcare systems.

IV. Going Global: The International Expansion (2002–2010)

Breaking into Britain

By the early 2000s, Sonic had done the hard part in Australia. It had stitched together enough of the market that the next question wasn’t “can we keep acquiring?” It was “where do we go now?”

That’s the moment Dr. Goldschmidt faced the classic consolidator’s fork in the road: stay home and harvest, or take the playbook overseas and risk discovering it only works on your home turf.

He chose the riskier option. In 2002, Sonic acquired The Doctors Laboratory, Britain’s largest private pathology practice.

This wasn’t just “international expansion” as a line item. It was the first real test of whether Sonic’s model—Medical Leadership, local autonomy, federated management—could survive in a completely different system. The UK’s healthcare gravity is the National Health Service, with reimbursement dynamics that look nothing like Australia’s Medicare. The Doctors Laboratory operated in the private market alongside that public behemoth: a narrower lane, but one with real demand and room to grow.

And Sonic didn’t win by barging in and rearranging the furniture. It did what it had learned to do in Australia: keep what made the asset valuable. The Doctors Laboratory largely kept its identity, its leadership, and its relationships, while Sonic brought capital, operational support, and the credibility of a larger network behind it.

For Sonic, Britain wasn’t about dominating a new country overnight. It was about proving the company could export the culture and still get the economics to work.

The German Beachhead

Then came the bigger swing. In 2004, Sonic acquired a 56% stake in the Schottdorf Group in Germany.

Germany was a very different proposition from the UK: larger, more complex, and structured around a social insurance model with multiple payers. Quality requirements were stringent, local competition was entrenched, and the medical culture was its own world. If the UK was a pilot program, Germany was the real stress test.

Sonic’s entry strategy was telling. Instead of buying everything outright, it took a majority position and partnered with the existing owners and management. The Schottdorf family stayed involved and invested. Integration risk dropped, continuity stayed high, and Sonic signaled something important to the German market: this wasn’t a foreign buyer arriving to centralize and cut. It was a medical organization trying to earn trust.

As the footprint grew, Sonic added coordination without smothering the locals. In 2009, it established a German Sonic Executive Committee to align operations across the country.

Germany would go on to become one of Sonic’s most important markets. Over time, Sonic became the market leader in laboratory medicine and pathology across multiple geographies—including Australia, Germany, Switzerland, and the UK—while ranking as the third largest private lab company in the United States.

America Calling

In 2005, Sonic made its move into the biggest diagnostics market on Earth, acquiring an 82% interest in Clinical Pathology Laboratories, Inc., the largest privately owned regional pathology laboratory in the United States.

The US is where global lab companies go to either become giants or get humbled. It’s enormous, but it’s also brutally competitive—dominated by two national powerhouses, Quest Diagnostics and LabCorp, with plenty of other well-funded players in the mix.

Sonic’s answer was not to charge straight at the national incumbents. Instead, it leaned harder into what made it different: Medical Leadership and a federated structure, built around regional diagnostic laboratories that could stay close to local physicians and hospitals. The bet was that many American healthcare partners wouldn’t just choose a lab on price; they’d choose reliability, responsiveness, and clinical partnership.

Sonic kept building through the decade. In 2007 alone, it added a wave of businesses, including American Esoteric Laboratories, the remaining 18% of Clinical Pathology Laboratories, Mullins Pathology & Cytology Laboratory in Georgia, Sunrise Medical Laboratories in the New York metro area, and Woodbury Clinical Laboratory in Tennessee. That same year in Europe, it also expanded with acquisitions including the Medica Laboratory Group in Zurich, the Bioscientia Healthcare Group in Germany, and the remaining equity in the Schottdorf Group.

By the end of the 2000s, Sonic had transformed from an Australian consolidator into a multi-continent operator—with enough scale to matter, but still intentionally not run like a single monolithic lab.

The Federated Model

Out of all this expansion came the clearest articulation of Sonic’s real competitive edge: the Federated Model.

In practice, it meant Sonic would offer global resources, a common culture, and shared standards—but it would preserve local autonomy and identity. The people running each lab and practice were expected to stay embedded in their communities, close to referring doctors, and accountable for service quality on the ground.

The company’s logic was simple: no distant corporate headquarters can possibly understand the daily needs of every clinician in every city. Pathology is personal. Trust is local. So Sonic organized itself to keep decision-making as close as possible to the doctors it served.

This is also why high-quality acquisition targets were willing to sell to Sonic when they had other options. They could join a global group without feeling like they were being absorbed into a faceless machine. Since the early 2000s, Sonic replicated this model internationally and grew into the third-largest medical diagnostics company in the world, with leadership teams that remained rooted in their local markets.

Of course, there’s a built-in tension here. Autonomy is great for culture, retention, and service. It can be harder for standardization and synergy. Sonic’s long record of post-acquisition improvement suggests it generally threaded that needle—but the trade-off never disappears. It’s the price of preserving the very thing that makes the roll-up work in the first place.

V. The Roll-Up Playbook: A Masterclass in Serial Acquisition

The Strategy Explained

By the time Sonic had stitched together labs across Australia, Europe, and the US, “acquisitive” stopped being a phase and became a capability. After nearly a hundred deals, the company had effectively turned consolidation into a repeatable craft—one that tries to keep two things in balance: financial discipline on the way in, and cultural respect on the way through.

You can see the pattern in the map. Sonic expanded beyond Australia first into the United Kingdom in 2002, then into Germany in 2004, and then the United States in 2005. That sequence wasn’t random. It was a bet that diagnostics is a long-duration demand curve, and that the best places to compound are the ones where the economics don’t get rewritten every election cycle.

The underlying logic is simple. Diagnostic testing demand grows as populations age and as medicine shifts toward earlier detection and more specialized testing. And when reimbursement is anchored by government systems or mature insurance markets, the revenue line is more predictable. Combine that with an industry that’s still fragmented—lots of independent laboratories with strong local relationships—and you get the ideal hunting ground for a consolidator that knows how to buy without breaking what it buys.

Target Market Selection

Sonic has always been selective about where it plays. The company looks for political and financial stability to protect long-term investment, healthcare funding systems that are reliable enough to underwrite planning, and markets where its Medical Leadership model can actually take root. Then it layers on the obvious tailwinds: aging demographics and a steady expansion in what modern labs can test for.

That filter goes a long way toward explaining Sonic’s footprint. The company concentrated on developed healthcare systems—Australia and New Zealand, the UK, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, Ireland, and the US—rather than chasing faster-growing but higher-risk markets where reimbursement can be volatile and collections can be uncertain.

Integration Philosophy

Picking targets is only half the game. Sonic’s edge has been what it does after the deal closes.

At the center is decentralised management. Local laboratories keep meaningful autonomy, and local leaders stay responsible for the relationships that matter: referring doctors, hospitals, and the community. That’s the part that protects loyalty and preserves quality.

Meanwhile, Sonic works the “behind the scenes” levers that make scale real: shared services, procurement leverage, standardized IT, and best-practice sharing across the network. In other words, keep the front end local and trusted, while building a bigger, more efficient machine underneath.

Sonic Healthcare USA is a clear example of this approach. Rather than trying to run everything as one national lab, it operates as a federated network of community-based laboratories, built around medical leadership and professional pathology services—designed to win on quality and service, not just price.

The LADR acquisition announced in December 2024 is the modern version of the same playbook. Sonic pointed to strong cultural and operational alignment between Sonic Healthcare Germany and LADR, and highlighted synergy opportunities across procurement, overlapping laboratories, specialised testing, logistics, equipment maintenance, and the supply and distribution of medical consumables.

Just as important: Sonic said the integration would be overseen by the senior leadership teams of both organizations, with LADR’s leaders—including CEO and medical director professor Jan Kramer, CFO Thomas Wolff, and infection prevention and control medical director Dr Tobias Kramer—committing to long-term roles within Sonic after the acquisition.

This is the pattern, repeated across decades: acquire a practice that already meets the bar, keep its leadership, and integrate deliberately. It’s less a checklist than a learned organizational muscle—what Hamilton Helmer would call process power: something competitors can see from the outside, but struggle to copy, because it lives in people, incentives, and habit.

For investors, the question is whether Sonic can keep running this playbook as the company gets bigger and the pool of obvious targets shrinks. The LADR deal, at an enterprise value of €423 million, signals that Sonic is now willing to swing at larger acquisitions—higher impact when they work, and higher execution risk when they don’t.

VI. The COVID Inflection Point (2020–2022)

The Surge

When COVID-19 hit in early 2020, diagnostics stopped being a background utility and became frontline infrastructure. Sonic, with laboratories spread across Australia, Europe, and the US, suddenly found itself in the middle of the global response.

In the United States, Sonic Healthcare USA’s network moved quickly to begin molecular testing for SARS‑CoV‑2. It wasn’t a slow ramp. Sonic’s labs became part of the country’s testing backbone, scaling capacity to meet demand as waves rose and fell.

Then came a major accelerant: Sonic was awarded a contract through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics Advanced Technology Platforms (RADx‑ATP) initiative. The goal was simple and enormous—fund a rapid scale-up of COVID testing capacity to 166,000 tests per day across nine high-throughput testing locations, with coverage broad enough to serve geographies across the United States.

And it wasn’t just America. Across Sonic’s global network, its laboratories processed millions of PCR tests that shaped public health decisions and helped countries reopen. For a company built to run high-throughput, high-trust medical operations, this was the ultimate stress test—and Sonic was built for it.

Peak and Plateau

The financial impact was exactly what you’d expect when a diagnostics giant becomes essential infrastructure.

Sonic produced record results for the 2021 financial year, including net profit of A$1.3 billion, up 149%, on revenues of A$8.8 billion. That profit was more than double what Sonic earned before the pandemic—a surge powered by extraordinary testing volumes running through infrastructure Sonic already had in place, with reimbursement dynamics that were unusually favorable.

The market followed the earnings. Sonic’s share price, once three cents back in 1990, climbed to nearly A$47 at the end of 2021. It was an astonishing arc—and it also baked in a hard truth: COVID testing was never going to be a permanent revenue stream.

Sonic didn’t treat the windfall like a one-off lottery ticket. It kept investing. Net debt rose as the company spent $585 million in the first half of FY2022 on acquisitions and investments. That included buying US-based ProPath for US$110 million, Australia’s Canberra Imaging Group for $60 million, and investing in Sydney-based Harrison.ai.

In other words: rather than handing all of the boom-time cash back to shareholders and pretending the party would last, management pushed capital into future growth, capability, and technology—choices that would matter most once the pandemic revenues faded.

The Hangover

Then the comedown arrived, as it always does when a temporary demand spike normalizes.

For the 2024 financial year, Sonic delivered revenue of A$9.0 billion and net profit of A$511 million. Profit fell versus the prior year as COVID-related revenue declined sharply—down 87%. Sonic also noted that revenue from COVID-19 services dropped by 80% to A$478.2 million once currency swings were stripped out.

The stock repriced accordingly. Sonic’s share price fell more than 40% from its late-2021 peak as investors reset expectations from “pandemic-era earnings power” back toward the base business.

And the base business came back into focus—with all its real-world pressures. During COVID, labs benefited from massive operating leverage and, in many cases, delayed normal cost increases. Post-COVID, the challenges were harder to ignore: labour cost inflation, reimbursement rates that were frozen or drifting down in several markets, and the operational work of right-sizing staffing and capacity for lower testing volumes.

But the core franchise didn’t break. Sonic reported base business (non‑COVID) revenue growth of 16%, including 6% organic growth on a like‑for‑like basis, supported by targeted acquisitions.

The lesson from COVID isn’t just that Sonic got a windfall. It’s that the company proved it could execute at scale under extreme pressure—and then reinvested the upside instead of letting the organization calcify around a temporary boom.

Now the story shifts again. The question isn’t whether COVID testing will come back. It’s whether Sonic can keep growing the underlying business while rebuilding and defending margins in a world where costs rise faster than reimbursements—and where the next efficiency leap likely comes from technology, not volume.

VII. The Modern Era: AI, Digital Pathology & The Next Chapter (2022–2025)

Technology Investments

Even as COVID revenue faded back toward normal, Sonic started leaning into what it believes is the next step-change in diagnostics: AI, and the digitisation of pathology workflows.

The headline moves were strategic stakes. Sonic took an 18% stake in Harrison.ai, and helped set up Franklin.ai, a joint venture focused on AI diagnostic tools for pathology. Sonic owns 49% of Franklin.ai directly, plus another 9% indirectly through its Harrison.ai stake.

The promise here is concrete: Franklin.ai is designed to act like a digital assistant for pathologists, using AI tools to improve accuracy, efficiency, and consistency. It pairs Harrison.ai’s AI development capability with Sonic’s global clinical scale and real-world diagnostic data.

Goldschmidt framed it as a natural extension of Sonic’s role in medicine: laboratory diagnostics sits under almost everything else clinicians do, especially in cancer diagnosis. In his words, the partnership would strengthen Sonic’s digital pathology efforts “on a global scale,” and position the company to play “a leadership role in this important new area of modern medicine.”

This wasn’t just talk. Sonic’s first completed AI product, Prostate Digital, was deployed for clinical evaluation in its Sydney laboratory, beginning in the second quarter of FY25.

The bet is straightforward: if AI can augment pathologists rather than replace them, it can lift throughput and quality at the same time. And in a world of wage inflation and tight labour markets, that kind of productivity unlock is exactly what diagnostics companies need.

Recent Mega-Acquisitions

If AI is Sonic’s look forward, acquisitions remain the engine in the present. Post-COVID, the company continued consolidating—but at a larger scale than before.

In December 2024, Sonic signed binding agreements to acquire LADR – Laboratory Group Dr. Kramer & Colleagues, one of the “Top 5” medical laboratory groups in Germany. LADR is a long-standing, family-owned business founded in 1945 and still owned by the Kramer family, now in its third generation. Its central laboratory is in Geesthacht near Hamburg, and it employs more than 2,800 full-time equivalent staff.

Sonic agreed an enterprise value of €423 million, and pointed to the familiar logic: cultural fit, operational alignment, and meaningful synergies. Financially, Sonic expected the deal to be immediately earnings-per-share accretive, with return on invested capital projected to exceed 11% per annum within three years—comfortably above its cost of capital.

Switzerland was the other major step. In March 2024, Sonic completed the acquisition of the Dr Risch Group, a move that significantly increased Sonic’s Swiss revenue—estimated at about 55% on an annualised basis. Dr Risch employs around 650 staff across 14 laboratories in Switzerland and Liechtenstein, and in calendar 2023 the Swiss laboratories generated 94 million Swiss francs in revenue, with a further 8 million Swiss francs from Liechtenstein.

The takeaway isn’t just that Sonic is still buying. It’s that even at its current size, it can still find large, high-quality targets—and, crucially, those owners still choose Sonic. For a roll-up model, that willingness is oxygen.

Leadership Transition

Then came the biggest change of all: leadership.

After 32 years running Sonic, Colin Goldschmidt decided it was time to retire. The Board announced he would step down at the company’s Annual General Meeting on 20 November 2025. By then, he will have led Sonic from a single Sydney laboratory to the global stage, becoming the third-largest pathology player in the world—and, more importantly, embedding Medical Leadership as the company’s defining philosophy.

His successor is Dr Jim Newcombe, who is set to become Managing Director and CEO from that same date. The choice is a statement: this isn’t a pivot away from Medical Leadership, it’s a reinforcement of it. Newcombe is a pathologist specialised in clinical microbiology, an infectious diseases physician, and a senior medical leader. He joined Sonic eight years ago and currently runs Douglass Hanly Moir Pathology in Sydney—Sonic’s founding practice and one of its largest laboratories globally—where he led a significant uplift in earnings and margins through strategic initiatives across operations, marketing, and people.

Alongside that, Sonic elevated Evangelos Kotsopoulos into the global COO role, a move that also signals where the company’s centre of gravity has been shifting. Kotsopoulos is currently CEO of Sonic Healthcare Europe and Sonic Healthcare Germany, overseeing Germany, Switzerland, and Belgium. A Hamburg native, he studied business and economics in Hamburg and at Sydney University, worked in investment banking, joined Sonic in 2007 as Business Development Director, then relocated to Berlin in 2011 to establish Sonic’s German head office and drive European growth. Under his watch, Sonic reached market leadership positions in both Germany and Switzerland.

For investors, CEO transitions always raise the same question: is the culture truly institutional, or was it held together by the founder-figure at the top? Sonic’s answer is embedded in the succession plan itself. A clinician is replacing a clinician, from inside the system, with the Medical Leadership philosophy intact—while operational responsibility is concentrated in an executive who has been central to Sonic’s most important growth theatre in recent years.

VIII. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

To understand Sonic’s competitive position, it helps to switch lenses: first, look at the industry structure it competes in, and then look at the specific advantages Sonic has built over decades. Porter’s Five Forces tells you what the game looks like. Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers tells you who’s best equipped to win it.

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Laboratory medicine looks deceptively simple from the outside. In reality, it’s a hard business to enter at scale.

You need expensive, sophisticated equipment. You need regulatory approvals and ongoing accreditation. And most importantly, you need trust—years of relationships with referring doctors and hospitals who will only change labs if they’re confident the new provider can deliver consistently.

Sonic’s own footprint shows the gap a newcomer would have to cross. Its diagnostic and clinical services are delivered by more than 2,200 pathologists, radiologists, and other clinicians, alongside roughly 18,000 employees in science-based roles. Recreating that kind of medical and scientific depth from scratch is not a startup project; it’s a decades-long build.

In highly consolidated markets like Australia, there’s another barrier: regulators. The scrutiny Sonic faces over further acquisitions is a signal that market concentration is already high—which often makes it even harder for a new entrant to break in meaningfully.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

On the equipment side, suppliers like Roche, Abbott, and Siemens are specialized, but not monopolies. Sonic’s global scale helps it negotiate, but switching major platforms is still a big decision with real cost and operational friction.

The more important constraint isn’t machines. It’s people.

Pathologists, medical scientists, and skilled lab technicians are scarce across healthcare systems worldwide. In the US, the number of pathologists fell 18% from 2007 to 2017 even as workloads increased. That’s a structural supply problem, and it gives talent real leverage.

Sonic’s Medical Leadership culture helps it compete for that talent—clinicians generally prefer working in organizations where clinical standards have real authority—but it doesn’t eliminate the reality of tight labor markets.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

Sonic engages directly with over 100,000 referring doctors globally, and those relationships matter. Individual physicians can switch labs, but it’s inconvenient and carries risk. That limits their power one-by-one.

The real pricing power sits with payers: governments and major insurers that set or negotiate reimbursement rates. That’s where the pressure comes from, and it’s persistent. In the US, for example, potential PAMA fee cuts were estimated to reduce revenue by around A$15 million in FY2025.

So while Sonic can win share and volume through service quality, it still has to run the business assuming pricing won’t bail it out. Margin defense has to come from efficiency, scale, and operational execution.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE

There are substitutes creeping in at the edges.

Point-of-care testing and home testing kits are getting better and more common. But the bulk of complex diagnostics still requires centralized lab infrastructure, specialist oversight, and quality systems that are hard to replicate outside a professional laboratory.

Sonic’s model is also different from some competitors in how it reaches patients. It doesn’t have a patient service center network as extensive as Quest Diagnostics, and unlike Quest, Sonic primarily processes tests ordered through healthcare providers, hospitals, and clinics rather than leaning into direct-to-consumer testing.

The upside is that Sonic’s investments in AI and digital pathology aim to keep it on the front foot—using technology to make the core lab workflow faster and better, so it’s positioned to shape the next wave rather than get caught by it.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Diagnostics is a scale business with intense rivalry, especially in the US.

Quest Diagnostics and LabCorp dominate national outreach and continue to do bolt-on deals. Sonic competes against them without the same national footprint or direct-to-consumer scale, which raises the bar on service quality, specialization, and local relationships.

Even where the overall market isn’t perfectly consolidated, the fight is constant: labs compete for hospital contracts, physician loyalty, specialized testing niches, and the operational efficiency to survive reimbursement pressure. The rivalry doesn’t have to be “price war” to be brutal—it can just be relentless.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: STRONG

Labs have big fixed costs: equipment, facilities, IT systems, and compliance. The more volume you run through that base, the better the economics get.

Sonic has shown how scale can translate into operating leverage. In FY2024, it delivered EBITDA margin expansion of 150 basis points in the second half versus the first half, alongside a reduction in labour cost as a percentage of revenue from 49.6% to 48.0%.

That’s the scale advantage in action: not just being big, but using that size to run more efficiently than smaller competitors can.

Network Effects: WEAK

Diagnostics doesn’t have classic network effects. One doctor doesn’t get more value simply because other doctors use the same lab.

But there are indirect “stickiness” effects: IT integrations with physician practice management systems and hospital information systems, along with established workflows, make labs harder to swap out than they appear on paper.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE

Goldschmidt put Sonic’s positioning plainly: “We call ourselves a medical diagnostic company, which means that we practice in pathology and radiology only. There have been temptations to go beyond that… We took the decision a few years ago that we wanted to stay narrowly focused on diagnostics only.”

That focus matters because some competitors have pursued vertically integrated healthcare models. For them to mirror Sonic’s narrow diagnostics focus would require unwinding strategy, structure, and incentives—often an unattractive move even if Sonic’s approach works well.

Switching Costs: MODERATE-STRONG

Sonic’s federated model is designed to keep labs responsive to local medical communities, tailoring service to what community physicians and hospitals actually need.

Over time, that creates real switching costs: familiarity with local pathologists, established service expectations, and embedded IT connections. In hospital outreach, switching is especially painful because lab services are woven into hospital systems and clinical workflows. Changing providers isn’t just picking a new vendor—it’s changing part of the operating fabric.

Branding: MODERATE

Patients usually don’t choose the lab. Referring doctors do.

That makes Sonic’s reputation for quality, reliability, and Medical Leadership a real differentiator in the only place it needs to matter: among clinicians deciding where to send work, and among high-quality practices deciding who they’re willing to sell to.

Cornered Resource: STRONG

Goldschmidt’s most enduring contribution wasn’t a single acquisition or market entry. It was committing Sonic to a Medical Leadership model that shaped how the company treats staff and how it prioritizes service quality for doctors and patients.

That culture—plus the organizational capability to run a federated network without it turning into chaos—is hard to copy. It’s not a policy manual. It’s history, people, and norms built through years of repetition.

Process Power: STRONG

Sonic’s federated management structure keeps leadership teams embedded in their local communities, and that commitment to Medical Leadership has been central to how the company operates and performs.

After more than 100 acquisitions, Sonic has built real process power: the ability to source the right targets, assess cultural fit, pay rational prices, integrate operations, and capture synergies without destroying the relationships and medical standards that made the acquired practice valuable. Many competitors can do deals. Fewer can do them repeatedly, across countries, without breaking the machine.

IX. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

Valuation Normalization Creates Opportunity

Sonic’s share price fell more than 40% from its COVID-era peak as pandemic testing revenue evaporated. That repricing is the market admitting what everyone knew in their bones: the boom wasn’t permanent.

But underneath the noise, the base business kept moving. In FY2024, Sonic still delivered 6% organic growth, and it used the post-COVID period to deepen its position with meaningful acquisitions rather than retreat into defensive mode.

Management has guided to FY2025 EBITDA of A$1.70 billion to A$1.75 billion on a constant-currency basis. It also expects recent acquisitions to add roughly A$700 million of annual revenue from FY2025. If margins continue to heal toward more normal levels and the integration synergies arrive as planned, today’s valuation can look less like a trap and more like an entry point.

Structural Growth Tailwinds

Diagnostics has a quiet advantage: it rides multiple long-term waves at once. Populations are aging. Medicine keeps getting more precise, which means more tests, not fewer. Preventive care keeps pushing detection earlier. And test menus keep expanding, including more genetic and specialized work.

None of that depends on a single blockbuster product cycle. It’s a steady, durable backdrop for volume growth—even in a world where pricing is constrained.

AI Investment Positions for Future

Sonic is also trying to create its next efficiency lever rather than waiting for one to arrive. Management has said these technology bets have “very material future earnings potential,” because AI and digital workflows could deliver step-change improvements in productivity and quality.

The strategic stakes and partnerships—Franklin.ai, Harrison.ai, and PathologyWatch—are Sonic’s attempt to be a leader in digital pathology rather than a late adopter. If those tools meaningfully augment pathologists and streamline workflows, they don’t just improve service; they can expand capacity and protect margins in an inflationary cost environment.

Disciplined Capital Allocation Track Record

One of the most underrated signals in Sonic’s story is consistency. Since first paying a dividend in 1994, Sonic has never cut its full-year dividend in 30 years—through recessions, reimbursement pressure, and even the post-COVID earnings snapback. That doesn’t happen by accident. It suggests a culture that thinks in cycles, not quarters, and allocates capital with unusual restraint for an acquisitive company.

Looking forward, the bullish setup is straightforward: solid underlying demand, additional contribution from recent European deals, and the potential for earnings growth in FY2026 as synergies in Switzerland and Germany build and LADR is integrated. Sonic has pointed to the prospect of strong FY2026 earnings growth, with guidance implying EPS growth of up to around 19% using current exchange rates.

The Bear Case

Structural Margin Pressure

Sonic can be operationally excellent and still be squeezed. That’s the reality of diagnostics in mature healthcare systems: payers are under constant pressure, and they rarely respond by raising reimbursement for lab work. Meanwhile, costs—especially labor—keep moving up.

That mismatch creates a structural margin headwind. Sonic highlighted that inflationary pressure, particularly in labor, impacted FY2024 and was expected to continue into the early part of FY2025. The risk is that “recovery” becomes a treadmill: efficiency gains arrive, but pricing and costs keep offsetting them.

US Market Challenges

Sonic is the third-largest lab company in the United States, but that still means it’s looking up at two giants. Quest Diagnostics and LabCorp have national reach and scale advantages in a market where those advantages can matter—especially as healthcare becomes more consumerized.

Sonic’s federated, regional model is a strength in service and local relationships. But it may be a disadvantage if the market shifts further toward national contracting power and direct-to-consumer convenience. There’s also competitive complexity abroad: LabCorp’s purchase of a 15% minority stake in SYNLAB for €140 million gave it a window into European regulatory and market dynamics, adding another well-capitalized player with growing insight.

Integration Execution Risk

Sonic’s recent European acquisitions are not small, tuck-in deals. LADR and Dr. Risch are among the largest transactions in the company’s history, which raises the execution stakes.

Sonic has pointed to LADR’s projected 2024 revenue of around €370 million and EBITDA of around €50 million, implying an EV/EBITDA multiple of about 8.5x on those figures. Big deals can be transformative when they go right. But if integration stumbles, the earnings impact doesn’t stay local—it flows straight through the group.

Leadership Transition Uncertainty

Colin Goldschmidt’s 32-year run is inseparable from Sonic’s identity. The succession plan—Dr. Jim Newcombe stepping in—signals continuity. Still, leadership transitions introduce uncertainty even when they’re well designed. The open question is whether Medical Leadership is truly institutionalized, or whether some part of it was uniquely tied to Goldschmidt’s presence at the top.

Pathology EBITDA Concentration

Sonic is diversified geographically, but the earnings engine is concentrated by modality. Pathology contributes about 84% of total EBITDA. That concentration cuts both ways: it provides focus, but it also means any negative shock specific to pathology—regulatory, technological, or competitive—hits disproportionately hard.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

For investors tracking Sonic Healthcare’s ongoing performance, three KPIs matter most:

-

Organic Revenue Growth Rate: This isolates the health of the underlying business from acquisitions and currency. Pre-pandemic, Sonic’s organic growth was reliably mid-single digits; a sustained return to that range post-COVID is a signal the franchise is still compounding.

-

EBITDA Margin: This is the scoreboard for whether Sonic can offset reimbursement pressure with scale and operational execution. The key isn’t whether margins drift down from pandemic highs—it’s whether they stabilize at an attractive level or continue to compress.

-

Return on Invested Capital on Acquisitions: Sonic’s model depends on turning deals into durable returns. Management’s target for LADR—11%+ ROIC within three years—sets a clear benchmark. If Sonic consistently hits numbers like that, the roll-up remains a compounding machine. If not, the model gets harder to defend.

Conclusion

Sonic Healthcare is, at its core, a story about a rare combination: disciplined capital allocation paired with genuine respect for medical professionalism. It went from a three-cent listed also-ran to a global diagnostics leader by building an acquisition engine that didn’t destroy the clinical trust it was buying.

Medical Leadership—doctors leading organizations that serve doctors—became more than a cultural preference. It was a strategic advantage, shaping Sonic’s federated model and making high-quality practices willing to join the group. COVID then proved Sonic could operate as critical infrastructure under extreme pressure, and the company used that moment not just to harvest profits, but to invest—into technology, into acquisitions, and into the next era of diagnostics.

The risks are real and not going away: reimbursement-driven margin pressure, intense competition in the US, the larger integration burden of recent mega-deals, and a once-in-a-generation CEO transition.

But the counterweight is also real: diagnostics demand continues to rise with demography and medical progress; Sonic holds leading positions in stable, developed markets; and the company has built repeatable capabilities—cultural and operational—that are hard for competitors to replicate.

Whether the current share price properly reflects that mix of headwinds and compounding potential is ultimately a call each investor has to make. But the foundation Sonic built—over decades, across countries, and through cycles—has proven durable before.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music