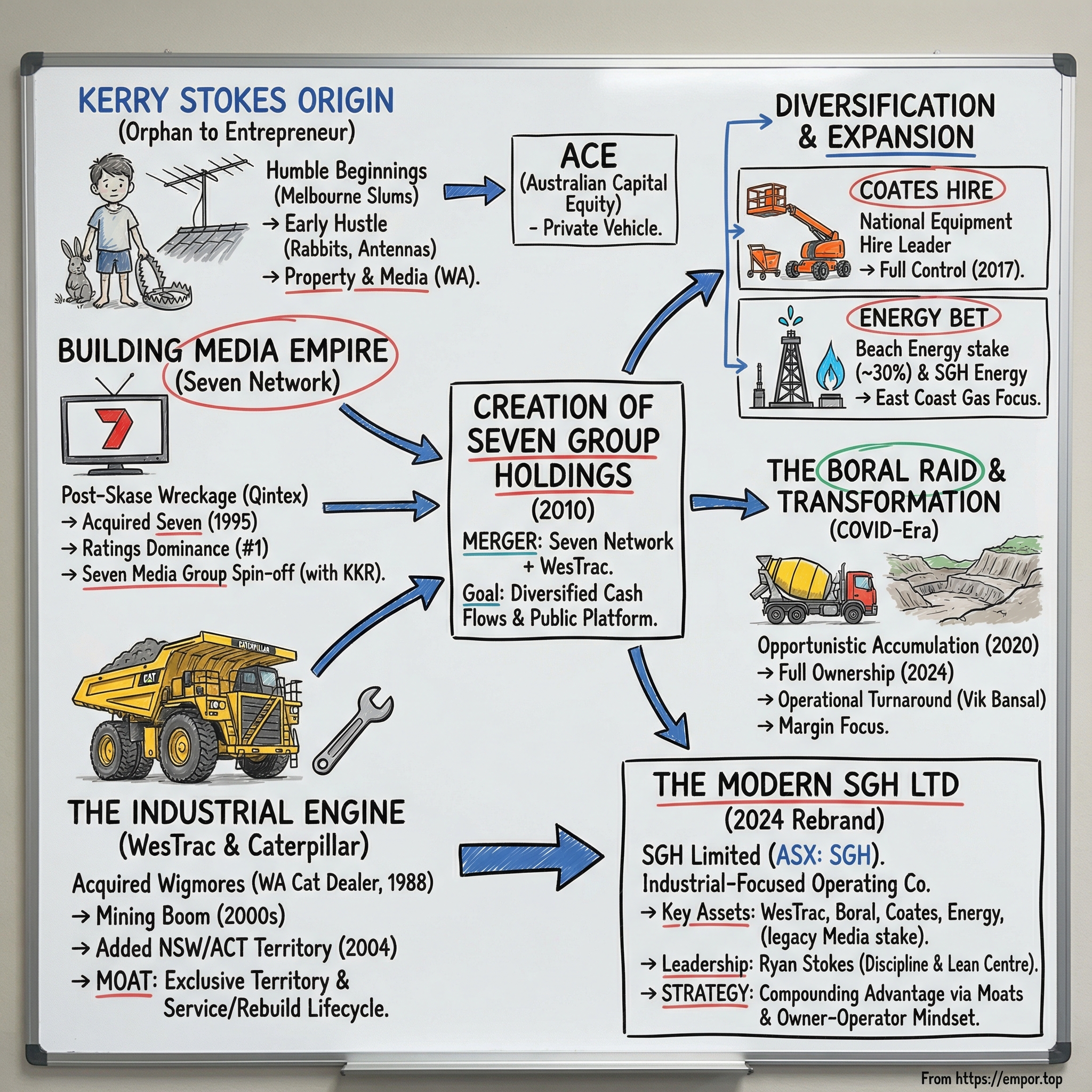

SGH Ltd: The Kerry Stokes Empire - From TV to Caterpillar to Concrete

I. Introduction: Australia's Last Corporate Raider

Picture this: May 2020. Global markets are in freefall. COVID has punched a hole in confidence, and the ASX is sliding hard. Boral, one of Australia’s oldest construction materials companies, has been crushed—down to A$1.79 a share, from A$5.20 just three months earlier.

Most investors see a falling knife.

One buyer sees a doorway.

While everyone else is de-risking, Kerry Stokes is quietly building a position. Then, on May 29, 2020, he makes it unmistakable: Seven Group Holdings buys about 95 million Boral shares in a single day.

That move wasn’t a one-off trade. Stokes is the last surviving entrepreneur from Australia’s roaring ’80s takeover era still willing to do things the old way: on-market raids, relentless accumulation, and an instinct for when fear has created a bargain. Over the following twelve months, Seven Group Holdings poured more than a billion dollars into Boral stock.

And that’s the hook for this story: SGH Ltd, the company that today looks far less like a media group and far more like an industrial machine—Caterpillar mining trucks, concrete and asphalt, Australia’s biggest equipment hire fleet, oil and gas exposure, and, hanging off the side, what’s left of a once-mighty media stake. By May 2025, the Australian Financial Review put Kerry Stokes’ net worth at A$12.69 billion—tenth-richest in the country, and one of the very few people who have appeared on every Financial Review Rich List since it began in 1984.

Even the name tells you where the business has gone. In November 2024, Seven Group Holdings changed its name and ticker—Seven Group Holdings Limited (SVW) became SGH Limited (SGH), effective November 18, 2024. This wasn’t cosmetic. It was a statement: the “Seven” brand no longer described the centre of gravity. Media assets had shrunk to less than 1 percent of group assets. What remained was an industrial-focused, diversified operating company.

The recent results underline that pivot. In FY25, SGH grew revenue 1% to $10.7 billion and lifted EBIT 8% to $1.5 billion. It reported a 10-year EBIT CAGR of 20%, declared a fully franked final dividend of 32 cents per share—62 cents for the year, up 17%—and delivered a 46% total shareholder return, well ahead of the ASX100’s 15%.

But if you want to understand how a television empire became a concrete-and-Caterpillar powerhouse, you have to start with the person behind it.

And that story begins in post-Depression Melbourne, in the slums, with a boy who trapped rabbits to survive.

II. The Kerry Stokes Origin Story: From Orphan to Oligarch

It’s the kind of beginning that reads like fiction. One biographer put it this way: it’s “a story worthy of Dickens but with a dash of Henry Lawson… Oliver with an Australian twist.” A foundling story, an Australian one, that starts in slums and orphanages and ends—somehow—in boardrooms.

Kerry Matthew Stokes was born John Patrick Alford on September 13, 1940, in Melbourne. His unmarried mother was Marie Jean Alford. As an infant he was adopted by Matthew and Irene Stokes, and he grew up in Camp Pell, a slum housing area.

Camp Pell was no ordinary address. Set in Royal Park, it was emergency housing thrown together after World War II: corrugated iron shacks, originally built to house refugees. Stokes was raised there by his itinerant adoptive parents, in the hard edges of post-Depression Melbourne. As a boy, he trapped, skinned, and sold rabbits to help make ends meet—work that teaches you, early, what things are worth and how quickly circumstances can turn.

The circumstances of his adoption stayed murky, and for a long time he barely spoke about it. Biographers have argued that silence mattered—that it left him with a complicated sense of identity, and an engine of ambition that never really switched off. Whatever the psychology, the habit it produced was practical: a constant scanning for what comes next, and an instinct to learn from the past.

Money pressures pushed him out of school at fourteen. He bounced through jobs, then at nineteen made the move that would shape everything: he left Melbourne for Perth, Western Australia, and found his first steady work installing television antennas.

There’s an almost perfect symmetry there. The future media king started by climbing onto rooftops so other people could pull in the signal.

What also shows up early is his fascination with technology. When computers arrived, Stokes was among the first people in Perth to own an Apple II—the early mass-market home computer released in 1977. He wanted to know what the next wave looked like before it hit.

From antennas, he moved into property development in the 1960s and 1970s. Alongside partners Jack Bendat and Kevin Merifield, he developed shopping centres in Perth and regional Western Australia. And as the deals grew, he built the vehicle that would quietly underpin the next several decades: Australian Capital Equity, the private holding company for his expanding interests across property, construction, mining, and petroleum exploration.

Australian Capital Equity—ACE—wasn’t just a corporate shell. It was the structure that let Stokes play a different game: patient, aggressive when needed, and largely out of public view. It gave him control, flexibility, and the ability to take positions that would be uncomfortable—sometimes impossible—for a conventional public-company CEO.

Even as his wealth grew, his intellectual curiosity didn’t fade. In 1994, Stokes—dyslexic, self-made, and still carrying the stamp of his childhood—was invited to deliver the prestigious Boyer Lectures. He had always been drawn to stories about class and struggle. As a teenager, he once noticed a young woman on a tram reading Mikhail Sholokhov’s Quiet Flows the Don, and later said it pulled him toward Russian literature because it dealt with the “real life” of poverty, wealth, and power.

His competitive streak became legend. In the late 1990s, Stokes and Kerry Packer fought bitterly as Seven and Nine battled for dominance, including over the Sydney Olympic Games in 2000. Packer once growled, “I should have crushed you when I had the chance.” Stokes’ reply captured the man: “But I never gave you the chance.”

Official recognition followed. In 1995, Stokes was appointed an Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for service to business and commerce, to the arts, and to the community. In 2008, he was appointed a Companion of the Order of Australia (AC) for service through strategic leadership and promotion of corporate social responsibility, to the arts through executive roles and philanthropy, and to the community.

Philanthropy—particularly art—wasn’t an afterthought. He developed a long association with the National Gallery of Australia, serving as chairman for several years and making multimillion-dollar donations. He also received Rotary International’s Paul Harris Fellow Award and holds a life membership of the Returned and Services League of Australia.

His personal life was complicated, too. Stokes has been married four times. His first marriage to Dorothy “Dot” Ebert produced two children, Russell and Raelene. His second marriage to Denise Bryant produced two sons, Ryan and Bryant. After a brief third marriage to actress Peta Toppano, he married Christine Simpson in 1996. He is a father of four and has three grandchildren.

One prominent private equity executive told Crikey, “He likes to fight and he doesn’t lose many.” That reputation isn’t just colour. It’s a clue—because the next chapters of SGH only make sense if you understand the person driving it: a man built for contests, who learned early that security isn’t given, it’s taken.

III. Building the Media Empire: Seven Network Origins

To understand SGH—still known for “Seven” long after it stopped being primarily a media company—you have to start with the wreckage that created Kerry Stokes’ opening.

In the late 1980s, Australian media was a leverage-fuelled arms race, and no one embodied it more than Christopher Skase. His vehicle was Qintex Limited, a Brisbane-based group that began life in 1975 as Takeovers, Equities & Management Securities (TEAM), before rebranding to Qintex and surging into the big leagues in 1986.

At its peak, Qintex was a trophy cabinet: interests in Channel 7, Mirage Resorts, Hardy Brothers, and other high-profile assets. The whole thing was built on debt—huge borrowings used to buy prestige, scale, and influence. But when conditions turned, the maths turned brutal. High acquisition costs, big operating bills, and a softer advertising market during the 1989–1990 recession squeezed cash flow, while interest expenses kept climbing. By the time the walls started closing in, Skase’s group had piled up more than A$700 million in debt.

Then came the kind of deal that looks bold right up until it becomes fatal. A failed $1.5 billion bid for MGM Studios in 1991 helped tip Qintex into receivership. Skase had already fled Australia in 1990 to avoid extradition, and the remnants of the empire were left for others to salvage.

Out of that receivership, a new company was assembled: Seven Network Limited. In 1991, receivers bundled Qintex’s broadcast assets into a clean structure and effectively reset the network’s corporate life. (The network also began formally using the “Seven Network” name in 1991, after having used it informally for some time.)

This was the kind of moment Kerry Stokes lived for: chaos, mispricing, and a valuable asset that needed a steady hand.

But he didn’t arrive from nowhere. Stokes had been building media experience in Western Australia for years. His interests began with the Golden West Network, a regional television network based in Bunbury, developed in partnership with Jack Bendat. In 1979 he bought Seven Canberra, later acquired Seven Adelaide from Rupert Murdoch, won the third commercial station licence in Perth, and also accumulated radio stations across Victoria, South Australia, and Western Australia.

Then, in 1987, he sold those early media assets—sold to Frank Lowy in 1987—banking both capital and hard-earned know-how. He could afford to wait for a bigger prize.

That prize came in the mid-1990s. Seven was re-listed on the stock exchange in 1993, with News Limited holding 14.9% and Telstra holding 10%. In 1995, Stokes bought 19.9% of the company and became chairman. In 1996, he increased his strategic stake—backed by Alan Jackson of Nylex, whom Stokes installed to lead the company. Jackson served as a non-executive director of Seven from 1995 to April 2001, after being asked by Stokes to take the role.

With the control position secured, the deal-making started. In 2002, Seven Media Group acquired Pacific Magazines. In January 2006, it partnered with Yahoo! to create Yahoo!7, an early attempt to fuse broadcast reach with internet distribution.

And then came the move that, at the time, looked like a private equity flex applied to a public broadcaster. In December 2006, Seven Network Limited shareholders voted to spin off the company’s “old media” assets into a 50/50 joint venture with KKR, forming Seven Media Group. It brought in deep-pocketed capital and financial sophistication—while Stokes kept his hands on the wheel.

On screen, Seven was thriving. It held the Australian broadcasting rights for the 2008 Beijing Olympics and even provided the broadcast feeds for swimming and diving to the rest of the world. The International Olympic Committee awarded Seven a gold medal for its Athens 2004 coverage.

The ratings told the same story. Since 2007, Seven has been Australia’s highest-rating television network, ahead of Nine, Ten, the ABC, and SBS. In 2011, it won every single week of the ratings season—40 out of 40—something no network had achieved since the introduction of the OZtam system in 2001.

But here’s the twist: even while Seven was winning on the scoreboard, Stokes was preparing for a world where television wouldn’t be enough. The economics were getting tougher—digital disruption, pressured advertising, and ever-rising content costs. If he wanted to build an empire that could compound for decades, the next foundation wouldn’t be made of programming.

It would be made of machines.

IV. The WesTrac Masterstroke: Caterpillar & the Mining Boom

If you want to understand how Kerry Stokes made his real fortune, forget television. The real engine of wealth was painted Caterpillar yellow—and, even more importantly, came with an exclusive right to sell and service it across some of Australia’s richest mining and construction territory.

Stokes’ entry point was Western Australia’s Caterpillar dealer, Wigmores Ltd. He invested in the franchise in 1988. Over time, that business became WesTrac: the Cat dealer spanning Western Australia and, later, New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory. It grew into a major employer too, with close to 4,000 staff and about 500 apprentices across Australia.

The broader history of Caterpillar dealerships in Australia is full of power plays, and it matters because it explains why this asset was so valuable. In the late 1980s, corporate raids were common—and so were messy takeovers. In 1987, Waugh & Josephson was taken over by Robert Holmes à Court. Soon after, Bond Corporation took control of W & J as it gained control of the Bell Group. But Caterpillar wouldn’t simply rubber-stamp a transfer of dealership rights. It refused to shift the NSW Caterpillar agency to Alan Bond or any of his companies, and instead the dealership was transferred to Gough and Gilmour, effective February 1989.

That’s the key detail: Caterpillar dealerships aren’t normal distribution contracts. They’re closer to long-term partnerships, where reputation and stewardship matter as much as capital.

In the middle of all this, Stokes kept building. In 1990, he used Australian Capital Equity to buy 30% of Morgan Equipment, and by 1991 ACE had purchased the remaining 70%.

Then came the moment where the story literally returns to its roots. John Court convinced Kerry Stokes to bring the Caterpillar agency back to its former home. Stokes agreed, the old site was extensively upgraded, and the dealership was renamed Westrac Equipment—returning to the historically important South Guildford premises.

And WesTrac didn’t stay local for long. In April 2004, the Caterpillar agency for NSW and ACT was transferred to WesTrac. The handover was marked on April 9, 2004, with Kerry and Ryan Stokes joined by senior Caterpillar executives including Chris Curfman, Doug Oberhelman (then Caterpillar’s CFO and later its CEO), and Peter Gammell.

So why is a Caterpillar dealership such a powerhouse business?

Start with the product. WesTrac supplies mission-critical machinery to the biggest operators in the country, supporting customers in Australia’s iron ore and thermal coal regions. It supplies Caterpillar mining trucks to companies like BHP and Rio Tinto, and Caterpillar engines for power generation and marine transport. Caterpillar itself had been operating in Western Australia since 1925, with a dealership opened at South Guildford in 1950—so by the time Stokes took control, he wasn’t buying a startup. He was buying an institution.

Then add the timing. The mining boom of the 2000s turned WesTrac into a cash machine. Between 2006 and 2013, WesTrac sold and delivered more than 500 machines to major miners, as greenfield projects and brownfield expansions effectively doubled the installed base of Caterpillar equipment out in the field. It was also during this period that WesTrac delivered its first 797F—then the largest mining truck in the world—and the 795F, Caterpillar’s largest electric drive truck at the time.

By 2025, the scale was staggering. Caterpillar’s own milestone year coincided with WesTrac celebrating 35 years delivering Cat equipment and technology across Western Australia. WesTrac CEO Jarvas Croome said the company had delivered more than 20,000 Cat machines and supported more than 47,000 customers in WA across mining, construction, agriculture, and forestry.

“WesTrac first started in 1990, serving customers from a facility in South Guildford and we have since expanded to more than 10 branches across the state, including within the Kimberley, Pilbara, Mid West, Goldfields and South West regions.”

But the real magic isn’t just the sales. It’s the lifecycle.

A mining truck doesn’t get bought and forgotten. These machines run hard, around the clock, in brutal conditions. That creates a river of high-margin, recurring work: parts, servicing, field support, and major rebuilds. As WesTrac itself puts it: “A rebuild will breathe new life into your old machine. Not only will it be back to like-new performance and productivity, it’ll have a new serial number and comprehensive warranty… for a cost that’s around 40% less than new.”

And finally, the moat: territory.

WesTrac is the sole authorised Caterpillar dealer in Western Australia and in NSW/ACT. That exclusivity means no rival can wake up tomorrow and decide to compete by selling Cat equipment next door. If you want Caterpillar in those regions, you go through WesTrac—full stop. It’s a structural advantage with the kind of durability most businesses can only dream of.

Coates is the largest industrial and general equipment hire company in Australia. The business services over 16,000 customers through a national footprint of approximately 145 branches, 1,900 employees, and over one million pieces of equipment across 22 product categories.

V. The 2010 Transformation: Creating Seven Group Holdings

The merger that created Seven Group Holdings in 2010 made Stokes’ real plan obvious: television could fund the journey, but industrial services would be the destination.

On 22 February 2010, Seven Network Limited announced it would merge with WesTrac—Kerry Stokes’ Caterpillar dealership, owned by Australian Capital Equity. Shareholders approved the deal in April, and the combined entity took a new name: Seven Group Holdings.

The structure did something simple, and powerful. It put a cyclical, ad-driven media business next to a mission-critical industrial franchise with deep recurring service revenue, and wrapped them in a single listed vehicle. That gave Stokes diversified cash flows, public-market currency, and a platform that could keep buying.

Then, almost immediately, the group began untangling the media side again. In April 2011, Seven Media Group was acquired by West Australian Newspapers to form Seven West Media. SGH stayed on as the biggest shareholder, holding 40.2%—exposure to media without needing to be a pure-play media company.

Coates was the next proof point that this wasn’t theory; it was a playbook.

Coates began life in 1885 as a small Melbourne engineering business, later shifting into equipment hire after World War II. It listed on the ASX in 1955, was bought by Australian National Industries in 1972, and re-listed in August 1996.

In 2007, Stokes’ National Hire Group—more than 50% owned by WesTrac—partnered with The Carlyle Group to acquire Coates Hire. SGH increased its involvement in 2008 through its WesTrac subsidiary, and then, on 25 October 2017, it bought the remaining 53% of Coates from Carlyle and other minority owners for $517 million.

The timeline matters. Stokes was willing to start with a minority position, let the business compound under someone else’s stewardship, and only take full control when the moment suited. That’s not the behaviour of a trader hunting the next pop. It’s the instinct of an owner assembling an industrial portfolio meant to last.

VI. Ryan Stokes Takes the Helm: The Next Generation

Succession is the stress test for any family-built empire. For Kerry Stokes, the handover wasn’t about disappearing—it was about putting the next generation in the operator’s seat, while keeping the family’s grip through Australian Capital Equity.

Ryan Stokes had been in the machine for years before he ever got the top job. He became an Executive Director of SGH in February 2010. From August 2012 to June 2015, he served as Chief Operating Officer. Then, from July 2015, he stepped up as Managing Director.

At the same time, Ryan held senior roles across the wider Stokes group. He was appointed an executive director of the family’s private investment company, Australian Capital Equity, in 2001, and became its chief executive in April 2010—placing him at the centre of both the listed company and the private control room behind it.

If Kerry’s reputation is built on combat and instinct, Ryan’s is built on discipline and operating leverage. His philosophy starts with something most conglomerates would never brag about: a tiny headquarters.

“The group’s head office has a small head count,” he says. “In total there are about 14 people that work in the SGH corporate office. In a direct context, we’re an overhead. It’s pretty hard to hold our businesses to account if there is corporate largesse at the top. What we do has to be lean. That drives a leaner culture in each of the businesses.”

Even the language matters. Ryan has been careful about how the market sees SGH. “We try not to use that word when describing the group. We are a diversified operating company,” he says—pushing back on the “conglomerate” label that can attract a valuation discount.

The market, so far, has rewarded the approach. Over the past decade, Seven Group’s total shareholder returns have stood out among ASX-listed peers, turning it into something close to a sharemarket favourite.

Ryan’s influence also extends beyond the balance sheet. In July 2018, he was appointed Chairman of the National Gallery of Australia. He has also served as Chairman of the National Library of Australia, sat on the Prime Ministerial Advisory Council on Veterans’ Mental Health, and been a member of the IOC Olympic Education Commission. In the Queen’s Birthday Honours on 8 June 2020, he was appointed an Officer in the General Division of the Order of Australia.

By the mid-2020s, the transition looked deliberate and largely complete. Kerry Stokes, in his mid-eighties, had stepped back from day-to-day operations, while maintaining strategic oversight. He remained Chief Executive Officer of Australian Capital Equity Pty Limited—ACE, the private company that holds the family’s major interest in SGH.

VII. The Boral Raid: Old-School Corporate Takeover

The Boral acquisition was SGH’s biggest move in years—and it read like a throwback to a style of deal-making most markets have long since tamed.

Back in the roaring ’80s, it was common for wealthy entrepreneurs to launch on-market share raids and battle for control of public companies. Dozens of venerable listed names—Woolworths, David Jones, Coles Myer, Elders IXL, even BHP—found themselves in the crosshairs of Alan Bond, Rupert Murdoch, Dick Pratt, Frank Lowy, Christopher Skase, Kerry Packer, Robert Holmes à Court, and Kerry Stokes.

Fast forward to COVID, and Stokes spotted the same pattern he’d always hunted: panic, mispricing, and an asset that could look very different under new ownership.

By 2021, Seven Group had moved from stake-building to outright pursuit. It made multiple takeover offers for Boral, which Boral repeatedly rejected on the grounds they undervalued the business. But the pressure didn’t let up. Over a matter of months, as record-low interest rates boosted Boral’s domestic outlook and lifted buyer interest, Seven Group amassed roughly a 71% stake.

In July 2021, Seven Group Holdings took 70% ownership of construction materials company Boral. It gained full ownership of Boral in July 2024.

The final mop-up took time, and persistence. On February 19, 2024, Seven Group Holdings Limited made an offer to acquire the remaining 28.4% of Boral for about A$2 billion. After months of pursuit—and mounting market pressure—Boral agreed to a revised takeover offer from Seven Group Holdings, bringing the long chase to a close.

Seven Group Holdings Limited completed the acquisition of the remaining 28.4% stake in Boral Limited on July 4, 2024. Seven Group Holdings Limited confirmed that Network Investment Holdings Pty Ltd had completed its compulsory acquisition of the outstanding ordinary shares in Boral.

“Boral has been fully consolidated since SGH took control in July 2021, and SGH acquiring 100 per cent will not impact its day-to-day operations. As a wholly owned entity, Boral now sits alongside WesTrac and Coates in SGH, forming what we believe to be the strongest group of industrial services businesses in Australia.”

Then came the part SGH cared about most: the operational reset.

Boral announced that Vik Bansal would commence as Chief Executive Officer and Managing Director on October 10, 2022. He succeeded then-CEO Zlatko Todorcevski, whose departure had been announced earlier that June.

As Boral’s CEO, Bansal later framed the story as a deliberate rebuild of the machine, not a quick financial engineering exercise.

“CEO of Boral, Vik Bansal said: ‘It is an honour to have led Boral through a pivotal phase in its transformation. Over the past three years, we have repositioned the business including unlocking value from our privileged asset base, national scale, and vertically integrated model—all while fostering a high-performance culture.’”

A cornerstone of that transformation was a push on leadership depth—bringing in high-calibre external leaders while developing internal talent. In SGH’s telling, it was consistent with the group’s emphasis on people, and designed to create a foundation that could sustain momentum, target mid-teen EBIT margins through the cycle, and capture long-term growth across Australia’s infrastructure and residential markets.

The financial performance SGH reported showed the direction of travel. Boral delivered 26% EBIT growth to $468 million, with revenue up 1% to $3.6 billion. SGH attributed the improvement to “pricing traction, higher concrete volumes, and resilient demand in the commercial and engineering sectors,” partially offset by weaker conditions in residential construction and roadworks, particularly in regional areas.

A further transition was expected at Boral in early 2026. After concluding his role as CEO of Boral, Bansal was expected to be appointed to the SGH board as a non-executive director.

VIII. The Energy Bet: Beach & SGH Energy

If WesTrac is SGH’s machinery muscle and Boral is its concrete backbone, energy is the portfolio’s more overt macro bet: that Australia’s east coast gas market will stay tight, politically sensitive, and valuable as legacy supply declines and energy security moves from boardrooms to headlines.

SGH holds about a 30% interest in Beach Energy (ASX:BPT). Founded in 1961, Beach operates and partners across onshore and offshore oil and natural gas production from five producing basins in Australia and New Zealand, and it has become a key supplier into the east coast market.

Beach Energy Limited is based in Adelaide, South Australia. Formerly known as Beach Petroleum, it changed its name to Beach Energy in December 2009. It’s part of the S&P/ASX 200, and in 2020 it was Australia’s second-largest oil producer after Woodside Petroleum.

With SGH owning 30.2% of Beach’s shares, governance follows ownership: two directors are nominees. Ryan Stokes became Chair on October 17, 2024.

Operationally, Beach matters because it sits right in the infrastructure of east coast gas. It operates the Otway Gas Plant and the Lang Lang Gas Plant in Victoria. It also runs a major onshore oil business on the Western Flank of the Cooper Basin, has grown into Australia’s largest onshore oil producer, and is a joint venture partner on the Moomba Gas Project.

In SGH’s Energy segment, Beach’s production rose 9% to 19.7 MMboe, and revenue increased 13% to $2 billion. Development work continued on the Crux and Longtom gas projects.

Alongside that listed stake, SGH also wholly owns SGH Energy. Margaret Hall was appointed Chief Executive Officer of SGH Energy in September 2015 and is also a Director. Her remit: extract value from SGH Energy’s oil and gas assets in Australia and the United States, and build the growth agenda for the energy segment. Hall brought more than 28 years in the industry, including senior roles at Nexus Energy from 2011 to 2014 spanning development, production operations, engineering, exploration, and HSE, and before that 19 years with ExxonMobil in Australia.

IX. The Modern SGH: Portfolio Overview & Strategy

The name change to SGH Ltd in November 2024 wasn’t a rebrand. It was the company putting a full stop at the end of a long sentence: Seven had stopped being the point years ago. The industrial portfolio was.

Just as important, SGH no longer ran like a classic “holding company” where the centre owns stakes and hopes it all adds up. It ran as a diversified industrial operating company. The distinction sounds subtle, but it’s the whole strategy. Each major business is run on its own merits, with its own management, and it’s expected to earn an acceptable return on equity without leaning on the rest of the group. That discipline—letting operators operate, and forcing every asset to clear the same capital-allocation bar—has been a core driver of SGH’s consistency over time.

So what is SGH now, in plain English?

It’s an Australian diversified operating company with market-leading businesses across industrial services, energy, and media. SGH owns WesTrac, Boral and Coates. WesTrac is the sole authorised Caterpillar dealer in WA and NSW/ACT. Boral is Australia’s leading integrated construction materials business. Coates is Australia’s largest equipment hire business. SGH also has about a 30% shareholding in Beach Energy, wholly owns SGH Energy, and retains about a 40% shareholding in Seven West Media.

The FY25 results showed why this mix works. SGH delivered revenue of $10.7 billion, up 1%, and EBIT of $1.54 billion, up 8%, in line with guidance. It reported NPAT of $924 million, up 9%. Cash conversion was strong at 95%, and margins expanded, supporting a 17% lift in dividends. For FY26, SGH guided to low-to-mid single-digit EBIT growth.

Underneath those headline figures, the story was the operating businesses doing what they’re designed to do. SGH expanded its EBIT margin to 14.3% through disciplined execution across industrial services. Boral stood out again, delivering 26% EBIT growth and meaningful margin gains. WesTrac grew earnings too, despite currency headwinds, helped by strong demand from the Western Australian resources sector.

And the backdrop matters. SGH’s core businesses sit directly in the slipstream of Australia’s infrastructure and construction markets. A national pipeline estimated at around $1.8 trillion over the next seven years—and an ongoing push for roughly 240,000 new homes a year—creates the kind of long-duration demand that shows up as equipment hire, concrete and quarry volumes, and fleets of machines that need servicing. In other words: a steady drumbeat of work for WesTrac, Boral, and Coates.

X. Ownership Structure: Investing Alongside the Stokes Family

SGH’s ownership and governance setup is a big part of the story—and for minority shareholders, it cuts both ways. Buying SGH stock isn’t just buying WesTrac, Boral, Coates, and a set of energy and media positions. It’s choosing to invest alongside the Stokes family, in a structure designed to keep them in control.

That control has real upside. It’s hard to argue with decades of capital allocation that turned a media operator into an industrial heavyweight. And moments like the group’s $500 million placement have been held up as a kind of institutional stamp of approval: big investors were willing to back the Stokes judgement with real money.

But the same thing that can make the strategy coherent can also make governance feel different from a typical widely held public company. Kerry Stokes isn’t just a large shareholder. Through Australian Capital Equity and its associated entities, the family effectively operates SGH with a controlling-owner mindset. One disclosed holding is North Aston Pty Limited, with 33.87% of shares.

That’s why comparisons to private equity come up so often. Stokes is managing his own multi-billion-dollar stake alongside third-party minority equity, with the authority to act decisively. Public investors can participate in the ride—but they’re not in the driver’s seat.

The dual role of Ryan Stokes is another key feature. He runs SGH as CEO, and he also serves as Chief Executive Officer of Australian Capital Equity Pty Limited, the private company that holds a major interest in SGH. That kind of overlap can sharpen alignment—because the controlling family is heavily exposed to outcomes—but it also raises the obvious question: what happens when the interests of the controller and minority shareholders diverge?

SGH’s answer has been to lean on formal governance processes, including committees designed to handle related-party matters. For investors, that’s the trade: the benefits of owner-operator control and long-term thinking, balanced against the reality that this is a company where one family’s influence is central to how decisions get made.

XI. Analysis: Competitive Position & Investment Thesis

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

SGH’s best businesses are protected by the kind of barriers you can’t buy your way through.

WesTrac’s moat is explicit: it holds exclusive Caterpillar dealership territories. In Western Australia, and in New South Wales and the ACT, you can’t just decide to compete with WesTrac by selling Cat gear. Without Caterpillar’s permission, there is no dealership—and that permission isn’t on the table.

Boral’s equivalent advantage is physical. Quarries aren’t like warehouses; you can’t drop a new one on the edge of Sydney or Melbourne because demand is rising. Urban sprawl, planning rules, and environmental constraints make new approvals extraordinarily difficult. If you already have the rock close to the city, you’re sitting on a privileged asset base that gets more valuable over time.

Coates has the scale problem working in its favour. A genuine national hire fleet and footprint take years to build, cost enormous capital, and require a brand customers trust when a job is on the line. That makes “new entrant” more theory than reality.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

WesTrac’s relationship with Caterpillar is both the crown jewel and the dependency. Cat controls the product roadmap, pricing, and broader strategy. WesTrac, in turn, provides the local sales, service capability, and customer intimacy that make the brand work in-market. It’s a partnership—but not one where WesTrac gets to pretend it’s in charge.

Boral is less exposed here. A meaningful portion of its key inputs are internally sourced through vertically integrated quarry and cement assets, which dampens supplier leverage compared with a pure buyer of materials.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

On the WesTrac side, the buyers are world-class procurement machines. BHP, Rio Tinto, and other major miners negotiate hard and buy at scale. But there’s a catch: switching costs are real. When a site is standardized on Cat, you’re not just swapping a truck—you’re rewriting maintenance systems, retraining people, changing parts inventories, and risking uptime. And once the machine is in the ground, parts and service become a recurring relationship that’s less exposed to one-off price battles.

For Boral, buyer power varies by end market. Local logistics matter: concrete and aggregates have to show up on time, close to the job, and at the required spec. That gives well-positioned suppliers more leverage than it looks like on paper, especially in metro markets.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW TO MODERATE

The obvious long-term “substitute” in mining isn’t another dealer; it’s technology shifts—electrification and autonomy. But here SGH has an important hedge: if Caterpillar leads that transition, WesTrac is still the channel that sells, supports, and rebuilds it in its territories.

In construction materials, recycled aggregates and other alternatives are growing, but they’re constrained by quality, specification, and regulation. Substitutes exist, but they don’t eliminate the need for the incumbent supply chain—especially at scale.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

These are tough industries, and none of them are monopolies.

WesTrac competes for customer spend with other OEM ecosystems like Komatsu, particularly where fleets aren’t fully committed to Cat. Boral competes with major players like Adelaide Brighton (Adbri), Holcim, and a long tail of regional operators. Rivalry is real—but SGH tends to play where assets, scale, and service capability tilt the battlefield.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework

Scale Economies: Boral’s national footprint and vertically integrated network, and Coates’ fleet scale, create cost and service advantages that smaller competitors struggle to match.

Network Effects: There aren’t classic social-media-style network effects here, but there is a compounding dynamic: the more Cat machines operating in the field, the more valuable WesTrac’s parts availability, service coverage, and technical know-how become.

Counter-Positioning: SGH’s lean corporate centre is a strategic choice. With a small head office, the group can move faster and avoid the overhead creep that often drags diversified operators.

Switching Costs: Once a mine standardizes on Cat, the switching costs go far beyond the sticker price: training, parts inventory, maintenance routines, and operational workflows all anchor the relationship.

Branding: Caterpillar is one of the most valuable brands in industrial markets, and the customer sentiment is simple: Cat is the safe choice when downtime is expensive.

Cornered Resource: The exclusive Caterpillar territories are a true cornered resource—scarce, hard to replicate, and unavailable to competitors regardless of capital.

Process Power: SGH’s operating model—decentralized businesses, tight accountability, and an owner’s mindset—shows up in returns and consistency across very different operating units.

Key Performance Indicators

For investors watching SGH, three metrics do most of the explanatory work:

-

WesTrac parts and service momentum: This is the earnings-quality engine. It’s more recurring, typically higher margin, and less cyclical than new equipment sales.

-

Boral EBIT margin: The transformation story ultimately has to show up in margins. Management has talked about mid-teen EBIT margins through the cycle. Progress matters, but so does durability.

-

Adjusted net debt to EBITDA: With leverage now below 2x, SGH has room to maneuver. This ratio captures balance-sheet resilience and how much optionality the group has for the next opportunistic move.

Bull Case

Australia’s infrastructure pipeline remains enormous, and the housing undersupply implies years of demand for materials and equipment. Mining—especially in iron ore and gold—continues to require replacement machines, rebuilds, and relentless service support.

In that environment, SGH sits in advantaged positions: exclusive distribution where uptime matters, irreplaceable quarry assets near population centres, and scale in equipment hire. Add the owner-operator structure and aligned incentives, and the argument is that SGH can keep compounding without the typical “conglomerate” drag.

There’s also a portfolio-wide angle on the energy transition: electrification and autonomy in mining equipment through WesTrac, lower-carbon materials and recycling through Boral, and domestic gas relevance through Beach Energy.

Bear Case

Cycles still exist, no matter how good the business is. A sharp downturn in iron ore or coal would hit WesTrac’s capital equipment sales, and could soften demand that flows into construction and roadworks.

Seven West Media is now small in group terms, but it can still weigh on sentiment—and if advertising markets worsen materially, it could demand attention and capital that SGH would rather deploy elsewhere.

Boral’s margin gains also have to survive reality: energy, cement, fuel, and labour costs can rise faster than pricing, especially in competitive tender environments.

And then there’s governance. Control concentrated around the Stokes family creates key-person risk and the ever-present possibility of misalignment between controlling and minority shareholders.

Regulatory and Legal Considerations

No material regulatory proceedings are currently affecting SGH’s core operations. Construction materials is, by nature, an industry with ongoing environmental compliance and permitting complexity. Against that backdrop, Boral’s investments in recycled materials and lower-carbon concrete help position it for tightening requirements.

Myth vs. Reality

Myth: SGH is a media company.

Reality: Media is now less than 1 percent of group assets. SGH is, in substance, an industrial-focused diversified operating company.

Myth: Conglomerate discounts always apply.

Reality: Over the past decade, SGH has delivered exceptional returns while the ASX merely doubled. The market has treated its structure as an advantage, not a penalty.

Myth: Kerry Stokes mainly got lucky with the mining boom.

Reality: The Caterpillar position was built well before the boom, and the Boral raid during COVID showed the same counter-cyclical instinct decades later. The track record spans multiple cycles and industries.

The story of SGH is ultimately a story about compounding advantage.

Exclusive Caterpillar territories. Quarries you can’t recreate. Scale that takes decades to assemble. None of these were overnight wins, and none are easily copied. They’re positions built patiently—and then pressed hard when the moment is right.

Kerry Stokes built the empire with a mix of long-term ownership, crisis-time aggression, and a deep belief in operational discipline. He has now put Ryan Stokes in the operator’s seat, while the family remains firmly in control through its stake.

For investors, the forward-looking question is straightforward: can these moats keep doing what they’ve done so well—turning large, unglamorous industrial businesses into a machine that compounds? The structure suggests yes. But the next chapter, as always, gets written in the cycle.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music