Singapore Exchange: Asia's Gateway and the Art of Exchange Reinvention

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

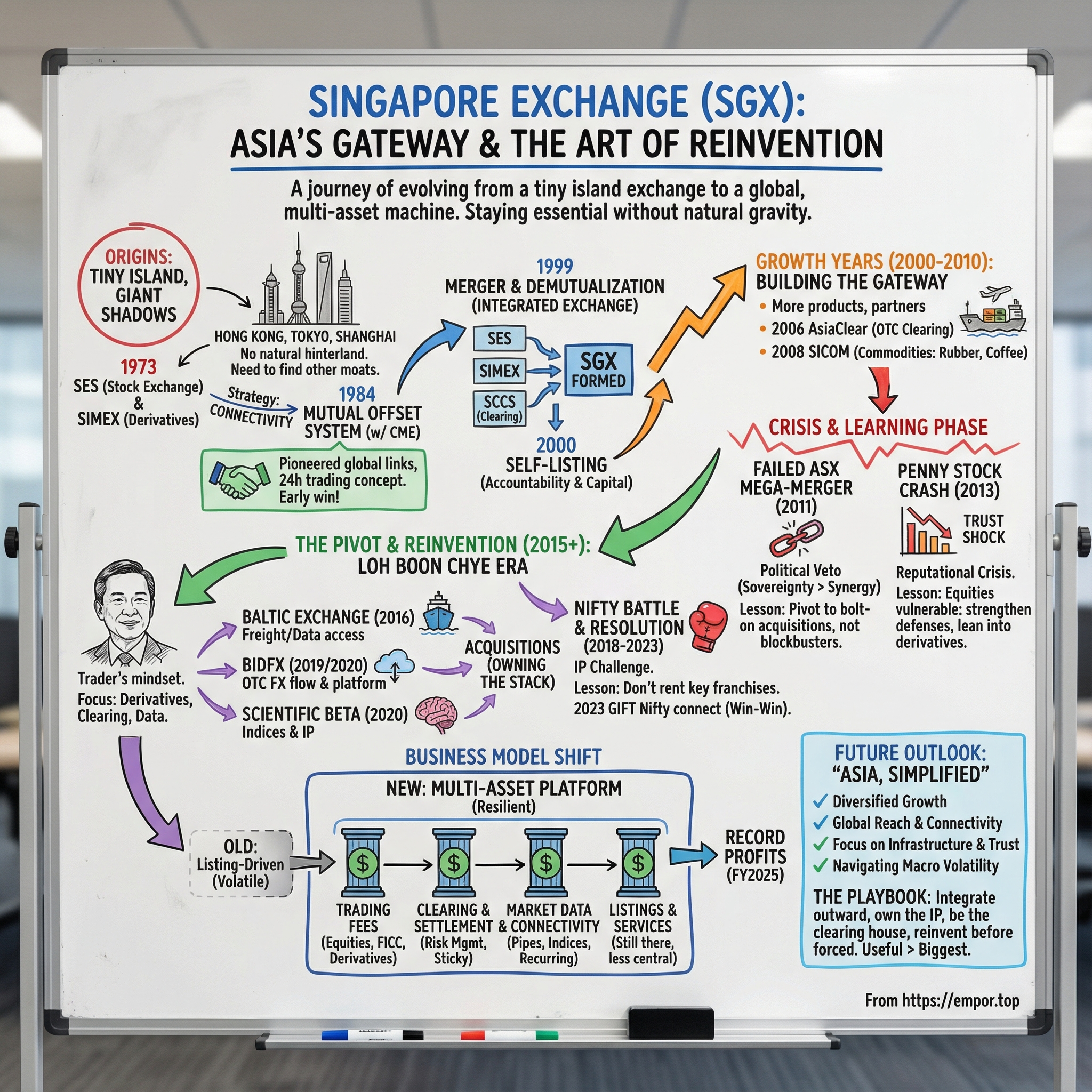

Picture a tiny island at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula—barely larger than New York City—deciding it won’t just be a stopover on global trade routes. It’s going to be a command center for Asian capital.

Singapore has no natural resources, no sprawling domestic economy to feed its own stock market, and it sits in the shadow of much larger neighbors. And yet its exchange has not only survived for decades, it has repeatedly found ways to matter—by evolving from a traditional stock market into a modern, multi-asset machine.

This is the story of Singapore Exchange Ltd—SGX—and the operating principle it learned early: if you can’t be the biggest exchange in the room, you’d better be the sharpest.

SGX is a Singapore-based exchange group that runs markets across equities, fixed income, currencies, and commodities. It does the whole stack: listings, trading, clearing, settlement, depository services, and the data pipes that keep markets running. It’s part of the World Federation of Exchanges, and as of September 2023 it was ASEAN’s second-largest exchange by market capitalization, behind Indonesia.

The question that frames everything is simple, and brutal: how does a tiny city-state’s exchange compete with Hong Kong, Tokyo, and Shanghai—and survive the existential threats that come from being small?

One comparison makes the problem painfully clear. Singapore and Hong Kong are both heavyweight financial centers, and Singapore’s economy is larger. But their stock markets live in different universes. In 2022, Singapore’s GDP was about $467 billion versus Hong Kong’s roughly $360 billion. Yet Hong Kong’s listed market was around $4.7 trillion in value, compared to about $404 billion for Singapore.

That gap is the whole story. SGX couldn’t win by being the obvious default destination for the region’s biggest IPOs. So it had to find other moats—places where liquidity, infrastructure, and trust could outweigh sheer size.

Those are the themes we’ll follow: demutualization and the hard shift from club to company; a decisive pivot from equities toward derivatives when listings became a losing battle; the heartbreak of a would-be mega-merger and the discipline of sticking to bolt-on acquisitions instead; the risk of building blockbuster products on intellectual property you don’t control; and the constant reinvention required to stay relevant in Asia’s crowded exchange landscape.

For anyone who watches exchanges as businesses, SGX is a rare case study: a small player that kept re-architecting itself, navigated crisis after crisis, and by 2025 was posting record profits. Let’s rewind and see how it pulled that off.

II. Singapore's Financial Origins: From Colonial Entrepôt to Trading Hub

Long before there were stock tickers or matching engines, Singapore was already doing what it still does best: connecting worlds. Sitting on one of the most important shipping corridors on the planet, the island grew up as an entrepôt—a place where cargo, capital, and information from China, India, Europe, and the wider Malay Archipelago met, got priced, and moved on.

And like every serious trading center in history, it developed its own version of the “coffee house” economy. Merchants gathered, rumors traveled, deals got done, and informal markets slowly started behaving like formal ones. The leap from handshake commerce to organized exchange trading wasn’t a reinvention so much as an inevitable upgrade.

That upgrade became official in 1973, when the Stock Exchange of Singapore (SES) was formed. The catalyst was geopolitical and monetary: Malaysia and Singapore ended currency interchangeability, which forced the Stock Exchange of Malaysia and Singapore (SEMS) to split into two separate entities—the SES in Singapore and Kuala Lumpur Stock Exchange Bhd (KLSEB) in Malaysia.

That split wasn’t just paperwork. When the currency link snapped, the capital markets effectively declared independence too. Singapore was signaling a distinct strategy—an open, international posture aimed at becoming a financial hub, not just a domestic market. A functioning, credible stock exchange wasn’t optional; it was core infrastructure.

Back then, former Finance Minister Hon Sui Sen voiced an audacious ambition: that the Stock Exchange of Singapore could become one of the leading exchanges in the world. Decades later, Singapore’s exchange did become one of Asia’s major bourses—but the way it got there wasn’t by simply out-IPO’ing the giants. It was by finding a different game to win.

That game was derivatives.

In 1984, Singapore launched SIMEX, the Singapore International Monetary Exchange—a commodities futures exchange and one of the earliest serious bets on futures and options in Asia. At the time, derivatives still carried a whiff of suspicion in many corners of finance. Singapore leaned in anyway.

What made SIMEX truly consequential wasn’t just that it existed. It was the way it reached outward. Under CME chairman Leo Melamed, CME Group and SIMEX jointly pioneered the Mutual Offset System in 1984—one of the earliest and most successful exchange linkages in the history of the derivatives industry.

Ng Kok Song, now managing director and group chief investment officer of the Government of Singapore Investment Corporation, helped pioneer the establishment of the first financial futures exchange in Asia through SIMEX. Working with Melamed, he helped create that mutual offset arrangement and served as SIMEX’s first chairman from 1984 to 1987.

The Mutual Offset System was conceptually simple, but operationally powerful: a futures position opened on one exchange could be liquidated on the other. In practice, that stitched together two time zones into something that looked and felt like a single, near-continuous market. Open in Singapore, close in Chicago—or the other way around.

That’s the key strategic insight SGX would come back to again and again: if you’re a small market, you don’t survive by staying local. You survive by plugging into global flows. Melamed put it plainly at the time: “I knew that if MOS proved to work, we would have revolutionized the trading of futures by connecting two time zones and bringing business and respect to Singapore shores.”

The SGX–CME partnership also helped internationalize Japanese equity futures. Today, Nikkei 225 Index futures trade actively around the world, and turnover of the Nikkei 225 Index futures listed at CME Group and SGX grew more than four times in the last decade compared to the decade before it.

The foundation was set: Singapore had proved it could build serious market infrastructure, attract heavyweight partners, and use connectivity as a force multiplier. The next question was how to turn that early advantage into a modern exchange built for scale.

III. The 1999 Merger: Creating Asia's First Integrated Exchange

By the late 1990s, stock exchanges everywhere were hitting the same wall. The old model—member-owned clubs that behaved like utilities—was starting to look less like stability and more like a constraint. Technology was changing trading, global competitors were scaling up, and capital markets were moving too fast for consensus-driven governance.

Singapore didn’t want to be dragged forward. It wanted to jump.

On 1 December 1999, SGX was formed as a holding company. The share capital of the Stock Exchange of Singapore (SES), the Singapore International Monetary Exchange (SIMEX), and Securities Clearing and Computer Services Pte Ltd (SCCS) was cancelled, and SGX issued new shares to take them over. In the process, the assets previously owned by those three organizations were transferred into SGX.

The result was bigger than a corporate reshuffle. Singapore had effectively stitched together the full market stack—equities, derivatives, and clearing—into one integrated exchange group. And it demutualized at the same time, converting from a member-owned entity into a for-profit corporation built to attract capital and compete like a modern company.

The strategic logic was clean: if you put listings and trading alongside derivatives and clearing, you create a one-stop shop. You can run a tighter operation, cross-sell products to the same customers, and—most importantly—make Singapore easier to plug into for global investors who don’t care about local history, only friction.

Then SGX did the ultimate credibility move. On 23 November 2000, it listed its own shares—becoming the third exchange in Asia-Pacific to do so, after the Australian Securities Exchange in 1998 and the Hong Kong Stock Exchange earlier in 2000.

An exchange listing on itself isn’t just symbolism. It’s accountability. It’s “these rules apply to us too,” with real money and real scrutiny attached. That kind of pressure tends to professionalize everything: governance, disclosure, performance expectations, and the internal culture of decision-making.

The SGX stock went on to become a component of benchmark indices such as the MSCI Singapore Free Index and the Straits Times Index.

From here on, SGX wasn’t just running a market. It was competing as a public company—with a mandate to grow, broaden beyond equities, and find the products and partnerships that could make a small exchange matter on a big stage.

IV. The Growth Years: Building the Asian Gateway (2000-2010)

With the demutualization done and the IPO behind it, SGX spent the 2000s doing what small exchanges have to do to survive: widen the map. More products, more partners, more reasons for global money to route through Singapore.

The biggest move of the decade was a quiet one, at least to the public. In May 2006, SGX launched Asia’s first over-the-counter clearing platform, SGX AsiaClear. The pitch was simple and powerful: if you’re going to trade OTC derivatives, you need someone in the middle making sure everyone gets paid. AsiaClear started with OTC trade registration and clearing for forward freight agreements (FFAs) and oil swaps. Shortly after, SGX launched the world’s first clearing and settlement of iron ore swaps—and over time it became the world’s largest clearer of iron swaps.

This turned out to be perfectly timed. As China’s infrastructure boom supercharged commodity demand, iron ore became one of the most heavily traded raw materials on earth. SGX had found a way to sit at the crossroads—not by owning mines or ships, but by owning the plumbing that made the market safer and easier to scale.

SGX kept pushing outward. On 25 September 2006, it and the Chicago Board of Trade launched the Joint Asian Derivatives Exchange, or JADE. But the partnership didn’t last. In November 2007, CME Group sold its 50% stake in JADE to SGX, the joint venture was cancelled, and the contracts migrated onto SGX’s QUEST trading platform.

It was an early reminder that exchange alliances can disappear the moment the corporate logic changes. When CME acquired CBOT, JADE stopped being a priority—and SGX had to absorb the business and move on.

At the same time, SGX was taking small but symbolic stakes around the region. In March 2007, it bought a 5% stake in the Bombay Stock Exchange for $42.7 million. India’s markets were accelerating, and SGX wanted proximity—relationships, insight, and optionality.

Then came an alliance in the other direction. On 15 June 2007, the Tokyo Stock Exchange announced it had acquired a 4.99% stake in SGX. It was the kind of cross-shareholding that signaled cooperation and mutual interest. But it also meant that when SGX made bold moves later, it would be doing so with a major exchange sitting on its cap table, watching closely.

In 2008, SGX moved deeper into commodities at home. Early that year it agreed to buy at least 95% of Singapore Commodity Exchange, and on 30 June 2008 it completed the acquisition of Singapore Commodity Exchange Ltd (SICOM), making it a wholly owned subsidiary.

SICOM brought rubber and coffee futures into the fold. And for Singapore, there was a nice narrative loop: rubber was one of the commodities that helped make the island a global trading hub in the first place. SGX wasn’t just adding contracts—it was reconnecting to an older identity, modernized.

The final marker of the era was a bet on market structure itself. In August 2009, SGX formed a joint venture with Chi-X Global called Chi-East. In early October 2010, the joint venture received approval from the Monetary Authority of Singapore to operate a dark pool trading platform.

This was SGX acknowledging a trend that was reshaping global markets: trading volume was fragmenting, and alternative venues were siphoning flow away from traditional exchanges. Instead of pretending it wasn’t happening, SGX tried to participate.

By 2010, SGX had built a broader platform across equities, derivatives, commodities, and even alternative trading venues. The next step, almost inevitably, was scale—and SGX was about to make its most audacious attempt to buy it.

V. Inflection Point #1: The Failed ASX Mega-Merger (2010-2011)

In October 2010, SGX took its biggest swing yet—and it stunned the exchange world. SGX and the Australian Securities Exchange announced they’d signed a merger agreement that would create Asia’s second-largest exchange group, behind only Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing. The price tag was enormous: SGX offered the equivalent of about US$8.8 billion for ASX.

On paper, the logic was hard to argue with. This was the era of exchange consolidation. NYSE and Euronext had already joined forces, and other giants were openly exploring tie-ups. In a world where scale was becoming a weapon, a mid-sized exchange that tried to stay independent risked becoming irrelevant.

SGX’s pitch was straightforward: combine complementary strengths, leap into the top tier, and become the world’s fifth-largest exchange group. Australia brought deep pools of capital and commodities expertise. Singapore brought derivatives muscle and the kind of Asian connectivity it had been building since SIMEX. Put them together, and you’d get a two-time-zone platform with real global heft.

Then reality hit. Fast.

Opposition surfaced almost immediately, starting with an uneasy response from Tokyo. The Tokyo Stock Exchange—SGX’s second-largest shareholder at the time—criticized the plan. A TSE representative warned the deal “would flag off a race to consolidate,” and TSE chief Atsushi Saito feared the move could leave Tokyo increasingly isolated.

But Tokyo’s discomfort was nothing compared to Australia’s reaction.

On 8 April 2011, Australian Treasurer Wayne Swan blocked the takeover on national interest grounds. The concern wasn’t just economic—it was sovereignty. Swan argued the merger would diminish Australia’s position as a financial center and create material regulatory and supervisory issues, especially given ASX’s dominance over clearing and settlement. The deal also faced opposition from both the Australian Securities and Investments Commission and the Reserve Bank of Australia.

Politics layered on top of regulation. A key flashpoint was Temasek, Singapore’s government-owned investment agency, which held a 23.5% stake in SGX. For many Australian politicians, the idea that their national exchange could fall under the indirect influence of a foreign government-linked shareholder was simply too much.

There were also structural barriers. Australia’s rules typically limited a single owner’s stake in a financial institution to 15%, and changing that would have required special legislation. And hovering in the background was a more human fear: that high-quality finance jobs would migrate from Australia to Singapore.

SGX tried to defuse the situation. It revised the proposal, including changes that would reduce the number of Singaporean citizens on the combined company’s board and add more seats for Australians. But the core objections didn’t move.

When the government made its decision, SGX withdrew. With the merger blocked, SGX pulled back its bid for ASX shares and turned to growth opportunities elsewhere.

The failed ASX deal became a strategic scar—and a strategic lesson. For exchanges, mega-mergers don’t just live or die on spreadsheets. They live or die on national interest. Sovereignty beats synergy, especially when market infrastructure like clearing and settlement is involved. And for SGX, the message was clear: if it wanted to grow, it would need a different playbook than blockbuster M&A.

VI. Inflection Point #2: The 2013 Penny Stock Crash—A Reputational Crisis

Two years after the ASX deal fell apart, SGX ran into a very different kind of threat. Not a political veto, not a failed acquisition—something far worse for a market operator: a credibility shock.

In October 2013, three mainboard names—Blumont Group, Asiasons Capital, and LionGold—collapsed after a frenzy of speculation. In a matter of days, more than S$8 billion of market value evaporated. Prosecutors would later describe what sat behind it as “the most audacious, extensive and injurious market manipulation scheme ever in Singapore.”

SGX moved fast. On Oct. 4, it suspended trading in the three counters after their prices plunged. Soon after, it designated the stocks as “designated securities,” a status that effectively slammed on the brakes: no short-selling, and purchases had to be paid for upfront in cash. It was the first time in five years SGX had used that designation—reserved for moments when the exchange believes there may be market manipulation, excessive speculation, or when it’s simply in the market’s interest to impose tighter conditions.

But the market’s attention quickly shifted from the three stocks to SGX itself. SGX sits in an unusually exposed position: it is both the market operator and, in key ways, the market regulator. That dual role has long raised an uncomfortable question—can an exchange be tough on listed companies that are also its customers? The penny stock crash dragged that tension into the open, as the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) confirmed authorities had begun investigating trading in the three names.

The legal process took years, but the picture that emerged was stark. Investigations began in 2014 and eventually narrowed from roughly 140 people questioned down to two central figures: Mr Soh Chee Wen (also known as John Soh) and Ms Quah Su-Ling. They were charged on 25 November 2016 under the Securities and Futures Act and the Penal Code over an alleged scheme to manipulate Blumont, Asiasons, and LionGold shares between August 2012 and October 2013.

The case was described as Singapore’s largest-ever share manipulation scandal, involving 189 securities trading accounts spread across 20 financial institutions and dozens of individuals and companies. On 5 May 2022, the High Court convicted Soh and Quah of market manipulation and cheating offences—180 charges for Soh and 169 for Quah. The sentences matched the scale of the damage: Soh received 36 years in jail, and Quah was sentenced to 20.

For SGX, the immediate job was to reassure investors that the market’s defenses were real—and getting stronger. SGX and MAS launched a review of the activity around the three stocks, and in February 2014 they jointly issued a consultation paper proposing enhancements to strengthen the securities market and better protect investors from speculative and manipulative behavior.

SGX also added new, more visible warning mechanisms. In 2015, it introduced “Trade with Caution” alerts—signals that typically came with details drawn from SGX’s surveillance, including, in some cases, that a small handful of individuals accounted for the bulk of daily trading volume.

The deeper impact, though, was strategic. After 2013, SGX invested to reestablish itself as a fundamentally robust platform, and it increasingly built strength in equity and FX derivatives.

Because the penny stock crash forced a hard reckoning: if the cash equities business was going to be vulnerable—to manipulation scandals, to listing droughts, and to relentless competition from Hong Kong—then SGX needed to lean even harder into the parts of the exchange where it could build a more durable moat.

VII. The Derivatives Pivot: Finding a Sustainable Moat

By the time Loh Boon Chye arrived in 2015, SGX’s direction was no longer a debate. The exchange had learned—through a failed mega-merger and a bruising credibility crisis—that equity listings weren’t a reliable moat for a small market. Derivatives, clearing, and the data businesses wrapped around them were.

Loh was appointed CEO effective 14 July 2015, and he came in with a career built inside the machinery of global markets. He had started at the Monetary Authority of Singapore in 1989, moved to Morgan Guaranty Trust in 1992 to run Southeast Asia fixed income and derivatives, spent 17 years at Deutsche Bank in senior leadership roles across corporate and investment banking and global markets, and most recently served as Deputy President and Head of Asia Pacific Global Markets at Bank of America Merrill Lynch from December 2012 to March 2015, where he was also the country executive for Singapore and Southeast Asia.

That background mattered. SGX didn’t need a ceremonial CEO. It needed someone who understood, at a trader’s level, what keeps flow coming back day after day. Derivatives generate recurring activity whether or not there’s an IPO boom. And clearing—where SGX steps in between buyer and seller to manage risk—isn’t just a service; it’s a relationship that becomes hard to replace.

So one of Loh’s first jobs was to sharpen SGX’s identity: not “Singapore’s stock market,” but a gateway into Asia and across asset classes. Coming out of years of weak confidence and soft volumes, SGX leaned further into being a multi-asset platform—equities, fixed income, currencies, commodities—and pushed harder into foreign exchange.

The signature move of this era was the Baltic Exchange acquisition.

The Baltic Exchange, incorporated as a private limited company on 17 January 1900 with shares owned by its members, is a British financial services company and membership organisation for the maritime industry. It’s also a freight market information provider—deeply embedded in the trading and settlement of chartering and freight derivative contracts. Its roots go back even further, to 1744, at the Virginia and Baltick Coffee House on Threadneedle Street near the Royal Exchange in London.

In 2016, SGX acquired the Baltic Exchange in a deal that valued it at about £87 million (around $108 million). The goal wasn’t to collect a trophy asset. It was to pull more of the freight derivatives ecosystem toward Asia. SGX said the Baltic handled about 40% of the global dry bulk freight derivatives market—a meaningful slice of a market where information and trust are everything.

The deal cleared the UK Financial Conduct Authority in October and gained formal court approval in London in early November 2016. Shortly after, SGX completed the acquisition. Loh summed up the intent simply: “We recognise the integral role the Exchange plays within the global shipping community, which we hope to develop for the benefit of the industry as a whole.”

Strategically, the Baltic acquisition did a few things at once. It gave SGX a prestigious European brand with deep relationships that SGX itself didn’t have. It expanded SGX’s international presence in a way that felt organic to its commodities and derivatives strategy. And it proved a critical point after the ASX disappointment: SGX could still do ambitious M&A—it just had to be bolt-on, targeted, and politically clean.

In SGX’s own words, the broader multi-asset push started showing up in the numbers: since it embarked on priorities of building a multi-asset exchange, growing its international presence, and deepening partnerships and networks in FY2018, a quarter of its clients increased the number of asset classes they traded with SGX. Over that same period, overnight trading grew from 10% of total derivatives volumes to 18% in the quarter being referenced.

For a small exchange, that overnight figure is telling. It’s not just growth—it’s proof that SGX was increasingly being used as a global venue, not a local one.

VIII. Inflection Point #3: The SGX Nifty Battle (2018-2023)

For nearly two decades, SGX hosted one of the world’s most actively traded emerging-market derivatives: futures tied to India’s Nifty 50 index. The contract—known globally as SGX Nifty—gave international investors a clean way to take a view on Indian equities without navigating India’s more complex onshore access rules.

And then, in 2018, India decided it wanted that business back.

In February 2018, India’s major exchanges signaled they would stop providing data and licensing their indices to overseas venues. For SGX, that wasn’t a minor commercial disagreement; it threatened the foundation of a marquee product. Around the same time, SGX announced it would introduce new India-linked derivatives, including single-stock futures on Nifty 50 components—moves that further inflamed tensions.

The National Stock Exchange of India (NSE) ended its licensing agreement with SGX in 2018. SGX responded by pressing ahead with new derivative products that NSE argued infringed its intellectual property rights. The dispute spilled into the courts: according to a Business Standard report, NSE filed a case in the Bombay High Court without giving notice to SGX.

As the legal and regulatory pressure mounted, an Indian court referred the dispute to arbitration and told SGX it could continue listing and trading SGX Nifty contracts beyond the initial cutoff—while barring it from launching the proposed new products until a final decision.

Behind the scenes, both sides were also searching for a face-saving way out. Discussions around what would become the NSE IFSC–SGX Connect began in 2019, after the brief but consequential feud. By September 2020, the issue was settled when both parties agreed to a tie-up.

After years of negotiation, the resolution finally took a clear form. In July 2022, SGX and NSE signed a connectivity agreement designed to transition trading activity from SGX Nifty to NSE’s international venue, NSE International Exchange (NSE IX), located in India’s new financial hub: GIFT City in Gujarat. The migration would be facilitated through the NSE IX–SGX connect mechanism—keeping overseas participants connected, but shifting the center of gravity back onto Indian soil.

On 3 July 2023, SGX Nifty was effectively reborn as GIFT Nifty: a USD-denominated index futures contract traded on NSE IX in GIFT City. The product itself had started life in September 2000 as SGX Nifty—an offshore gateway to the Nifty 50. Now the gateway had moved.

That first day made the symbolism feel real. GIFT Nifty recorded cumulative turnover exceeding US$1.2 billion, and market participants framed the shift as part of India’s push to consolidate liquidity and strengthen its position as a global financial hub. The migration also came with a revenue-sharing structure: SGX would initially receive 75% of the revenue from GIFT Nifty, with 25% going to NSE, until a “threshold volume” was reached, after which the split would move to 50:50.

For SGX, the Nifty saga delivered a lesson that was as painful as it was clarifying: if your biggest derivative franchise sits on intellectual property you don’t control—and a jurisdiction you don’t regulate—then it can be taken away.

The next chapter of SGX’s strategy would lean harder into owning the building blocks, not just renting them.

IX. The Multi-Asset Transformation (2019-Present)

From 2019 onward, SGX started making a different kind of bet. Instead of building the next franchise on someone else’s index or someone else’s market access, it went shopping for the pieces it could own: platforms, data pipes, and intellectual property that would still matter no matter where the next wave of volume showed up.

The clearest example was FX. SGX was already strong in listed FX derivatives, but the real global battlefield was the over-the-counter market—where the biggest institutions actually trade. To bridge that gap, SGX first bought a 20% stake in BidFX in March 2019, with a simple thesis: combine the scale and risk management of listed futures with the day-to-day reality of OTC FX.

Then, on 29 June 2020, SGX announced it would buy the remaining 80% of BidFX for about US$128 million in cash, expanding beyond FX futures into global FX OTC. BidFX—founded in January 2017—is a cloud-based FX trading platform built for institutional investors, and it had been putting up record volumes in the quarters leading into the deal. By May 2020, its average daily volumes had reached about US$31 billion, after compounding rapidly since launch. SGX expected the full acquisition to complete in July 2020.

If BidFX was about flow, Scientific Beta was about the building blocks underneath it: indices. SGX moved to scale up its Data, Connectivity and Indices (DCI) business by acquiring a 93% stake in Scientific Beta for EUR186 million in cash (about S$280 million), subject to closing adjustments. Scientific Beta—established by EDHEC-Risk Institute (ERI Asia), an affiliate of EDHEC Business School—was an independent index provider specializing in smart beta strategies, with deep expertise in factor-based and risk-managed solutions.

“The acquisition of Scientific Beta marks an important step in the evolution of our index business. Scientific Beta brings a highly regarded research pedigree in the rapidly growing smart beta space, along with a strong suite of high-profile clients in the US and Europe,” said Loh Boon Chye, CEO of SGX.

Together, BidFX and Scientific Beta weren’t random bolt-ons. They were a statement about where exchange economics were going. As pure trading fees got commoditized, the gravity shifted toward clearinghouses, indexation, and market data—the parts of the stack that are sticky, defensible, and harder to displace. SGX was building more of that stack inside its own walls.

And the shift showed up in the results. SGX’s multi-asset strategy both grew and diversified the business: between FY2016 and FY2024, revenue rose from S$818 million to S$1,232 million, while adjusted net profit increased from S$349 million to S$526 million. In its FY2024 full-year results, SGX also said its fixed income, currencies and commodities (FICC) segment had delivered a compound annual growth rate of more than 20% over the previous three financial years.

Then, in November 2025, SGX made its most ambitious equity-market push in years—by partnering with Nasdaq. The two exchanges announced a tie-up to simplify dual listings in the U.S. and Singapore, including a “Global Listing Board” for companies with market capitalizations above S$2 billion (about US$1.5 billion). SGX framed it as a way for companies to tap U.S. liquidity while keeping an Asian home base, through a more harmonized cross-border listing framework.

Loh Boon Chye put it this way: “The whole-of-ecosystem support has been a key driver in turning this vision into reality. For issuers, the proposition is clear: access to U.S. market depth and Asian growth in a streamlined pathway. We hope to attract quality growth-oriented companies with an Asian nexus seeking to expand their investor base, while staying true to their roots, without having to navigate the complexity of dual regulatory regimes.”

That same month, SGX pushed into another asset class that had been circling the edges of institutional finance for years: crypto. SGX Derivatives announced Bitcoin and Ethereum perpetual futures for institutional and accredited investors, with contracts launched on 24 November 2025. The pitch was pointed—regulated access, positioned as an alternative to offshore “bucket shop” venues—with the contracts tied to indices co-developed with CoinDesk and SGX’s iEdge brand.

Taken together—BidFX, Scientific Beta, the Nasdaq partnership, and regulated crypto derivatives—this is SGX’s post-Nifty playbook in action. Own more of what you sell, expand the definition of “Asia risk,” and make SGX the place institutions go to manage it.

As SGX Group marked its 25th anniversary in FY2025, it said it delivered its strongest performance to date, posting its highest revenue and net profit since listing. SGX attributed that to choices made over many years: diversifying across asset classes, expanding global reach, and building a platform meant to earn trust in every market condition. It described navigating a volatile backdrop—shifting trade dynamics, persistent inflation risks, and diverging monetary policy—while investors turned to SGX to manage risk and deploy capital efficiently. Growth, SGX said, was broad-based across its major business lines.

X. Business Model Deep Dive: How an Exchange Actually Makes Money

If you want to understand SGX as a business, you have to stop thinking of it as “a place where people buy and sell stocks.” An exchange group is really a bundle of toll roads—some obvious, some almost invisible—that sit underneath modern finance.

SGX, created in 1999 from the merger of the Stock Exchange of Singapore (SES) and the Singapore International Monetary Exchange (SIMEX), and later expanded with the acquisition of Singapore Commodity Exchange (SICOM) in 2008, runs two main on-exchange businesses: SGX Securities Trading and SGX Derivatives Trading. Across those, it provides the full market stack—listing, trading, clearing, settlement, depository services, and market data—for a multi-asset lineup.

So where does the money come from?

Trading fees are the most intuitive. Every time a trade happens on SGX, the exchange earns a fee. But globally, trading has become a tougher place to build a moat. Technology drives fees down, competition pushes costs lower, and liquidity can move fast.

Clearing and settlement is where the exchange model starts to get really interesting. This is the “hidden goldmine” part of the industry: when SGX’s clearinghouse steps in as the counterparty to trades, it charges for that risk-management role. It’s not flashy, but it’s sticky—participants don’t casually switch their clearing relationships. One window into the scale of that machinery is the SGX-DC clearing fund: it stood at $557 million as of 31 December 2024, and from 15 January 2025 it was reduced by $50 million to $507 million. SGX’s own commitment to that fund fell from $144 million to $132 million.

Market data and connectivity is the other big, modern revenue stream. In markets dominated by algorithms, real-time data feeds and low-latency access aren’t “nice to have.” They’re the product. And institutions will pay for speed, reliability, and direct pipes into the exchange.

Listing fees and corporate services are still there too—especially in the public imagination—but for SGX they’ve become less central over time, particularly as the region’s blockbuster IPO gravity has concentrated elsewhere.

You can see this mix in how SGX’s growth has increasingly come from its multi-asset engine, not the classic “cash equities” story. Currencies and Commodities net revenue rose $24.7 million, or 8.6%, to $312.5 million, driven mainly by higher volumes in OTC FX, currency derivatives, and commodity derivatives. Within that, OTC FX net revenue increased 25.3% to $113.0 million, with headline average daily volume up 28.5% to US$143 billion. Currency derivatives volumes climbed 49.7% to 73.6 million contracts, led by higher activity in INR/USD and USD/CNH FX futures.

Zooming out, the Fixed Income, Currencies and Commodities (FICC) segment delivered net revenue of S$321.6 million, up 8.6%, and accounted for nearly a quarter of group net revenue. That’s not a side business anymore. It’s a core pillar.

And this is the strategic arc we’ve been tracking the whole episode: the shift from equities-heavy to derivatives-driven wasn’t an accident. It was adaptation. Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing rode the wave of China’s capital markets and the steady drumbeat of enormous Chinese IPOs. SGX didn’t get an equivalent tailwind—and trying to win the “mega-IPO destination” game head-on was never going to be Singapore’s advantage.

So SGX leaned into the places where a smaller exchange can still build leverage: risk management, cross-border flow, and the infrastructure products that keep working even when IPO calendars go quiet.

Rather than fight a losing battle for mega-IPOs, SGX pivoted to where it could win.

XI. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

The SGX story leaves behind a playbook that travels well—whether you’re running a market, a platform business, or any company trying to win without the home-field advantage of scale.

Lesson 1: Small markets must integrate outward. From SIMEX’s 1984 partnership with CME to the 2025 Nasdaq dual-listing arrangement, Singapore kept acting on the same belief: isolation means irrelevance. SGX positioned itself as an “Asian Gateway”—a venue for global investors to access Asian growth, and for Asian issuers to reach international capital. And it did that by building a broad menu across securities, derivatives, and commodities, designed to plug into global flows rather than depend on domestic gravity.

Lesson 2: When mega-M&A fails, pivot to bolt-on acquisitions. The ASX rejection could have frozen SGX’s ambitions. Instead, it sharpened them. SGX shifted from blockbuster deals that trigger national-interest alarms to smaller, targeted acquisitions—like the Baltic Exchange, BidFX, and Scientific Beta—that added real capabilities and global reach without lighting up political tripwires.

Lesson 3: Derivatives and data are better moats than listings. Equity listings rise and fall with IPO cycles—and they’re brutally competitive when you’re up against bigger venues. Derivatives, once they reach critical mass, tend to stick because liquidity compounds. And market data and indices create recurring revenue that scales cleanly once the infrastructure is built.

Lesson 4: Be the clearing house, not just the exchange. Trading is where the action is, but clearing is where the power is. If you’re the party managing counterparty risk, you’re embedded in the system. SGX’s clearing infrastructure—recognized as meeting international standards for financial market infrastructure—doesn’t just support its markets; it anchors them.

Lesson 5: Own your intellectual property. The Nifty saga made the risk painfully clear: if a flagship product depends on someone else’s index and someone else’s jurisdiction, it can be pulled out from under you. After that, SGX leaned harder into owning the building blocks—especially indices and data—so its franchises would be harder to unwind.

Lesson 6: Extended trading hours as competitive advantage. In a global market, time zone coverage is a feature. With the region’s longest trading hours, SGX positioned itself as a conduit for risk transfer and capital flows into and out of Asia—useful even when the local market is asleep.

XII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

1. Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MEDIUM

Stock exchanges tend to be natural monopolies inside their own jurisdictions. But technology has weakened the old assumptions. Alternative trading systems and dark pools can peel off volume—especially in the most liquid names—by offering different pricing, anonymity, or execution logic.

SGX saw that shift early. In August 2009, it formed a joint venture with Chi-X Global called Chi-East. By early October 2010, the Monetary Authority of Singapore approved the venture to operate a dark pool trading platform. The point wasn’t that SGX suddenly had a dangerous new rival at home. It was that the “exchange” was no longer the only place trading could happen—and SGX needed a seat at that table.

Even so, regulation keeps this force contained. You don’t just spin up a new exchange the way you launch a fintech app. Licensing, oversight, capital requirements, and the credibility needed to attract participants still form a moat that’s hard to cross.

2. Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM

SGX’s customers—global banks, asset managers, hedge funds, and high-frequency firms—have real leverage. If fees go up or liquidity thins, the biggest players can route flow elsewhere. And the fastest firms will always push for rebates, incentives, and tighter economics.

But buyer power has limits, because the deeper you integrate into an exchange’s ecosystem, the harder it is to casually walk away. Clearing relationships, margin models, collateral arrangements, and connectivity are all operational commitments. Once a venue becomes part of your daily risk-management routine, switching stops being a pricing decision and starts becoming a systems decision.

3. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW-MEDIUM

Suppliers come in a few forms. One is technology. Trading venues run on complex infrastructure, and vendors like NASDAQ OMX can matter—especially when you’re modernizing platforms and need reliability at scale.

Another supplier category is the issuers themselves. Public companies are effectively “supplying” listings, and they have options. If Singapore can’t offer the right liquidity, analyst attention, or valuation, a company can look to Hong Kong or the United States instead.

And then there’s the supplier SGX learned to fear the most: index owners. If a must-have contract is built on licensed intellectual property, the licensor can suddenly become the most powerful entity in the room—as the Nifty battle made painfully clear.

4. Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM-HIGH

A lot of financial activity can happen without touching a traditional exchange. OTC markets compete directly for derivatives flow. Private markets and direct listings bypass the classic IPO-and-secondary-trading pipeline. For some exposures, ADRs and GDRs let investors trade a company’s story somewhere else entirely. And crypto venues—especially offshore ones—offer substitutes for certain products, even if they come with very different risk profiles.

The broader point: SGX isn’t just competing with other exchanges. It’s competing with alternative ways of transferring risk and raising capital.

5. Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is where SGX’s core challenge shows up most clearly. Singapore may have the heft of a major financial center, but it sits in a region filled with exchange giants that are fighting for the same international capital—and, crucially, for the same marquee listings and benchmark liquidity.

You can see the intensity in the comparison with Hong Kong. Singapore’s economy has been larger than Hong Kong’s, but SGX’s listed market value has remained a fraction of HKEX’s. That gap isn’t a Singapore failure so much as a reflection of how brutal exchange competition is when one venue sits closer to the biggest issuers, the biggest narratives, and the deepest pools of liquidity.

As of December 2024, HKEX had a market capitalization of approximately US$35 trillion and 2,631 listed companies, making it the 8th largest stock exchange globally. In a neighborhood like that, SGX can’t win by trying to out-HKEX HKEX. It has to win by being different—by specializing, by owning infrastructure, and by staying indispensable in the parts of the market where size alone doesn’t decide everything.

XIII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE

Exchanges are classic high-fixed-cost, low-marginal-cost businesses. You spend heavily on technology, regulation, and surveillance, and then every additional trade is relatively cheap to process. In theory, that should reward the biggest venues: more liquidity attracts more participants, which attracts still more liquidity.

But SGX lives with a structural constraint. It’s ASEAN’s second-largest exchange, not the region’s gravitational center. That means it can’t rely on sheer size to win. It has to manufacture advantage through focus and specialization.

2. Network Effects: STRONG (Primary Power)

This is the core power of every great exchange: liquidity begets liquidity. More traders create tighter spreads and better execution, which pulls in even more traders. Once that flywheel spins up, it’s hard for rivals to dislodge.

SGX’s dominance in clearing iron ore swaps is a perfect example. When you become the world’s largest clearer in a niche like that, the market starts routing itself through you almost by default.

The Nifty episode also showed the fragility of network effects when the underlying inputs—like licensed indices or data—can be taken away. But in the products and infrastructure SGX controls, network effects remain its strongest and most durable advantage.

3. Counter-Positioning: MODERATE

SGX didn’t try to out-HKEX HKEX. It chose a different battlefield.

Over time, SGX positioned itself as derivatives-first, while Hong Kong leaned more heavily into equities and marquee IPOs. Instead of chasing the same prize, SGX emphasized what it could credibly own: a multi-asset platform, a neutral venue for global investors, and extended trading hours that make it useful even when the local cash market isn’t the main event.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE

Once a trading firm is set up with an exchange, leaving is rarely as simple as “routing orders elsewhere.” Clearing relationships, margin models, collateral arrangements, and connectivity are deeply embedded in a firm’s operations.

That creates a form of built-in retention for SGX. Even if a competitor offers cheaper headline fees, the real cost is the disruption and risk of switching the machinery underneath the trading.

5. Cornered Resource: MODERATE

SGX has accumulated differentiated assets that aren’t just “another set of contracts.” The Baltic Exchange brings a storied brand and trusted shipping-market benchmarks. Scientific Beta adds specialized factor and smart-beta index IP. And SGX’s position inside Singapore’s regulatory framework gives it credibility that many venues can’t easily replicate.

Still, this power has limits. Many financial products can be licensed, copied, or economically recreated—so the advantage is real, but not absolute.

6. Process Power: MODERATE

The least visible advantages are often the hardest to copy. SGX’s operational strength—risk management, clearing, and the day-to-day discipline of running market infrastructure—has been built over decades and is recognized globally.

These processes don’t come from a single innovation. They come from compounding competence: systems, governance, controls, and muscle memory developed through real market stress.

7. Branding: LOW-MODERATE

SGX benefits from something most exchanges would love to borrow: Singapore’s reputation for rule of law, institutional stability, and an AAA sovereign rating. That halo matters, especially for global institutions that care about enforceability and regulatory credibility.

But exchange brands, in general, don’t command consumer-style premiums. They matter most indirectly—through trust—and SGX’s brand strength largely rides on Singapore’s broader credibility rather than pure marketing power.

XIV. The Current State and Key Performance Indicators

By FY2025, SGX’s multi-year pivot was no longer a strategy deck. It was showing up in hard results.

SGX reported EBITDA of $827.8 million (up from $702.2 million the year before) and net profit after tax of $648.0 million (versus $597.9 million). Earnings per share came in at 60.6 cents (55.9 cents). On an adjusted basis, EBITDA was $832.0 million (from $711.6 million) and adjusted net profit was $609.5 million (from $525.9 million).

In August 2025, Reuters reported that SGX had posted record annual earnings since its 2000 listing. Management also pointed to IPO momentum returning: more than 30 companies were said to be actively preparing to list, described as the strongest pipeline in years.

Shareholders were set to see that confidence returned in cash, too. The board proposed a final quarterly dividend of 10.5 cents per share, payable on 27 October 2025. If approved, that would bring total FY2025 dividends to 37.5 cents (up from 34.5 cents), an increase of 8.7%.

Reuters also reported that SGX not only declared that final quarterly dividend of 10.5 Singapore cents, but planned to raise dividends by 0.25 Singapore cents each quarter from FY2026 to FY2028.

In practical terms, that 0.25-cent quarterly step-up plan bakes in steady, low-single-digit annual dividend growth—assuming earnings broadly track management’s medium-term net revenue growth guidance of 6–8% per year (excluding treasury income).

For investors tracking SGX, three KPIs matter most:

-

Derivatives Average Daily Volume (ADV): This is the core growth engine. In October, derivatives ADV jumped 48% year-on-year to a record 1.58 million contracts, and total traded derivatives volume rose 52% to 31.3 million contracts.

-

Securities Daily Average Traded Value (SDAV): This is the pulse of the equities franchise. SDAV increased 26.5% to $1.34 billion, while total securities traded value rose 27.5% to $336.4 billion.

-

OTC FX Average Daily Volume: This is the clearest read on whether the BidFX bet is working. OTC FX headline ADV increased 28.5% to US$143 billion.

XV. Competitive Dynamics and Future Outlook

When Loh Boon Chye took over as CEO in July 2015, SGX wasn’t looking for a caretaker. It was looking for an operator—someone who could turn a small, exposed equities franchise into a resilient, global, multi-asset business. That’s been the through-line of his tenure: push SGX beyond “Singapore’s stock market” and into the category of infrastructure—risk management, clearing, data, and products that institutions use regardless of whether IPO markets are booming.

The industry has noticed. Loh was named CEO of the Year at Markets Media Group’s 2025 Global Markets Choice Awards. And in 2023, he was elected chairman of the World Federation of Exchanges—a role that signals something more important than prestige: peer-level credibility.

That credibility matters because SGX competes in markets where trust and legitimacy are the product.

You can see SGX’s strategic north star in the franchises it keeps emphasizing. Iron ore derivatives, for example, have become one of its most globally relevant contracts. SGX described its iron ore derivatives franchise as “Asia’s first global commodity,” and noted that its SGX Iron Ore 62% contract joined the Dow Jones Commodity Index in January—reflecting its role as a widely watched barometer of industrial demand. The long-term goal is clear: give clients one capital-efficient place to manage bulk cargo and freight risks, end-to-end, on a single platform.

FX is the other pillar. SGX has been leaning into the idea that, in a world where capital efficiency and liquidity matter as much as price, its flagship Asian FX contracts can keep pulling in new participants. The message is simple: if you want to manage Asia FX risk at scale, SGX wants to be the default venue.

But zoom out, and there’s a second storyline running alongside derivatives and FX: Singapore is trying to bring its equities market back to life—and SGX sits at the center of that push.

For much of the last decade, the optics were rough. Delistings outpaced IPOs. Some of the region’s best-known “Singapore stories,” like Grab and Sea, chose to list in the U.S. instead. By 2024, the number of listed companies on SGX had fallen to a two-decade low.

That’s why the recent talk of an IPO pipeline is more than PR. SGX has pointed to over 30 companies actively preparing to list—defining “pipeline” as firms working with advisers and doing the real work required for an IPO. In that context, management framed the setup as the strongest they’d seen in roughly six years.

Regulators have been signaling similar momentum. MAS said it had seen “increasing” activity and interest in Singapore’s equity market. Average daily turnover in the third quarter of 2025 rose 16% year on year to about SG$1.53 billion—the highest since the first quarter of 2021—with particular pickup in small- and mid-cap trading. IPO fundraising also accelerated, topping SG$2 billion for the year to date.

None of this means the road ahead is risk-free.

Valuation risk is real. After a mid-30s percentage rally in 2025, SGX’s shares traded at a high-20s earnings multiple and roughly 8 times book. If growth disappoints—if that IPO pipeline cools, or if derivatives volumes normalize—there’s room for the multiple to compress.

Competition also doesn’t pause. In FX and commodities, SGX is strong, but it’s operating in the shadow of global giants like CME and ICE, regional powerhouses like HKEX, and a sprawling universe of OTC platforms. Product innovation is a permanent arms race, and liquidity is never fully “won.”

And, like every exchange, SGX is sensitive to macro cycles. It’s a leveraged bet on trading activity and risk appetite. A sharp global risk-off shock can hit both sides of the business at once: lower volumes and weaker issuance.

The bet SGX is making is that a diversified, multi-asset platform—with clearing, data, and global connectivity wrapped around it—can absorb those cycles better than a traditional listing-driven exchange ever could.

XVI. Conclusion: The Art of Exchange Reinvention

The SGX story, in the end, is a story about adapting under constraint. A small city-state isn’t going to outmuscle China on IPO volume or outscale Japan on domestic depth. But it can be faster to change, more outward-looking, and more willing to specialize in the parts of the value chain that compound.

The exchange that began in 1973 as the Stock Exchange of Singapore—a spinoff triggered by a currency divorce—didn’t stay a local marketplace for long. It helped pioneer cross-border exchange linkages in 1984. It demutualized and stitched equities, derivatives, and clearing into one integrated group in 1999. It had the confidence to list itself in 2000. It swung for scale with ASX and got a hard lesson in national-interest politics. It took a reputational hit in the 2013 penny stock crash. And then it rebuilt—leaning into derivatives, clearing, and data—until it emerged in 2025 posting record earnings.

That arc is also visible in how CEO Loh Boon Chye talks about culture. “Personally, I strive for transparency, honesty and integrity, and these are the values and the behavior that we expect from our colleagues at SGX Group. I try to inculcate a mindset of making a difference, making an impact.”

And the ambition is explicit: “We want to be even more globally relevant, with a more active and meaningful influence in the market ecosystem.”

That’s what sits behind SGX’s tagline, “Asia, Simplified.” The goal isn’t just to run an exchange in Asia. It’s to make Asia tradable—to help global institutions navigate the region’s complexity and idiosyncratic risks through products, clearing infrastructure, and data they can trust.

For investors looking at SGX now, the real question isn’t whether it’s a “good” exchange. It’s whether the transformation—toward derivatives, indices, and connectivity—has created durable advantages, or simply swapped one set of cyclicality for another. SGX has earned a place among Asia’s most sophisticated market operators. Whether that translates into compelling long-term returns will depend on continued execution and on how Asian capital markets evolve from here.

What’s already clear is the bigger takeaway. Even in an industry ruled by network effects and scale, SGX has shown another path: pick the battles you can win, build the infrastructure that makes you hard to replace, and keep reinventing before the market forces you to. The tiny exchange from a tiny city-state found its role in global finance—not by being the biggest, but by making itself useful in ways that scale alone can’t buy.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music