ST Engineering: Singapore's Defence-to-Tech Powerhouse

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

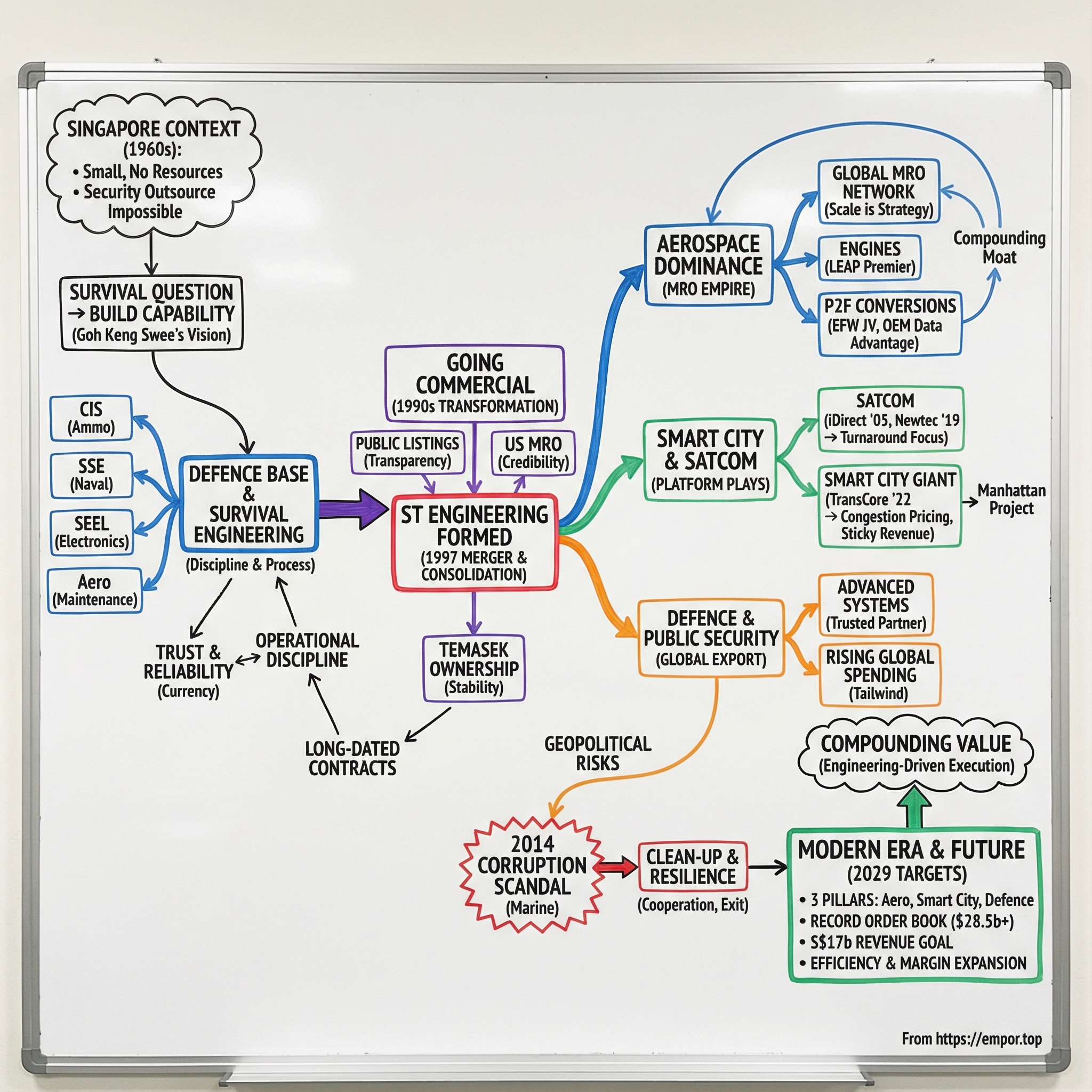

Picture a nation the size of a large city—surrounded by bigger neighbors, freshly separated from a federation, and starting with almost nothing: no natural resources, no military tradition, and no industrial base worth talking about.

Now fast-forward to today. That same city-state is home to a company that helps keep the world’s aircraft flying, builds and exports advanced weapons systems to more than a hundred countries, and sits behind major smart-mobility infrastructure—including the tolling system for Manhattan’s first-ever congestion pricing program. That company is ST Engineering, and its arc is one of the most surprising industrial transformations in modern Asian history—one that most Western investors barely register.

On paper, ST Engineering is a Singapore-based multinational technology, defence, and engineering group spanning aerospace, smart city, defence, and public security. As of 2024, it was the eighth largest company by market capitalization on the Singapore Exchange. But the label doesn’t capture the reality: this is a platform business built out of national necessity, then scaled globally through engineering execution and unusually disciplined expansion.

The core question is straightforward: how does a tiny city-state produce a global engineering powerhouse?

A big part of the answer is what you might call survival engineering—the idea that Singapore’s early existential anxiety wasn’t just political; it became industrial. When your security can’t be outsourced, you don’t just buy equipment. You build capability. You train talent. You set standards. And over time, those habits—precision, reliability, systems thinking—become exportable.

The company’s revenue mix shows how far that evolution has gone. Commercial Aerospace, Defence & Public Security, and Urban Solutions & Satcom accounted for 39%, 44%, and 17% of group revenue respectively. Commercial sales were $7.8b versus $3.5b in defence sales. The takeaway isn’t the exact split—it’s what the split represents: ST Engineering is no longer mainly a defence contractor with side businesses. Most of its revenue now comes from commercial customers, making it one of the clearest defence-to-commercial transformations anywhere in Asia.

Three themes define the story.

First: the defence-to-commercial pivot. Plenty of government-linked defence groups try to diversify; very few pull it off at scale without losing their edge in the core.

Second: the acquisition playbook. From iDirect in 2005 to Newtec in 2019 to the transformational TransCore deal in 2022, ST Engineering hasn’t bought “growth.” It has assembled global platforms—each one expanding the company’s reach in aerospace, satcom, and smart mobility.

Third: the culture underneath it all. Survival engineering isn’t just a founding myth. It’s a management system—one that keeps showing up in how the company executes, modernizes, and competes in heavily regulated, mission-critical industries.

And the timing is good. The group ended the year with revenue of $11.28b, up 12% from $10.1b. EBIT hit a new high of $1.08b, up 18% from $915m. Those are record results, and management has set ambitious targets for 2029 that would make ST Engineering meaningfully larger. At the same time, global defence spending is rising, infrastructure is back in focus, and “smart city” is shifting from buzzword to budget line item—tailwinds for both sides of the portfolio.

So why does a company this large still feel invisible outside Singapore?

Partly it’s structural: it’s listed in Singapore, majority-owned by Temasek, and operates in sectors that don’t naturally create consumer brand awareness. But there’s a deeper reason, too. To understand ST Engineering is to understand how Singapore thinks—about national security, economic development, and the deliberate overlap between government priorities and commercial execution.

That’s what we’re going to unpack. And by the end, ST Engineering won’t feel like a collection of business units. It’ll feel like a single idea, built over decades: take the capabilities required for survival, and turn them into a global export.

II. The Singapore Context: Building a Nation, Building Weapons

To understand ST Engineering, you have to start with the mood in Singapore in the late 1960s. In August 1965, the island was expelled from the Malaysian federation. Overnight, it was on its own—small, exposed, and surrounded by much larger neighbors. There was no meaningful military to speak of, no natural resources to lean on, and plenty of outsiders willing to bet the new country wouldn’t make it.

That insecurity didn’t just shape foreign policy. It shaped industrial policy. If Singapore couldn’t rely on others for its defence, it had to build the capability itself—and build it in a way that could stand on its own two feet.

The clearest expression of that idea came from Goh Keng Swee, Singapore’s first Minister for Defence and one of the architects of the modern state. Goh’s philosophy was brutally practical: defence industries were necessary for national security, but they couldn’t become complacent government workshops. They had to be commercially run, focused on profit, and forced to compete—even for contracts from the Singapore Armed Forces. The government could provide the initial push, but performance had to sustain the machine.

The first tangible step was Chartered Industries of Singapore (CIS), incorporated on 27 January 1967, barely eighteen months after independence. Its job was unglamorous but foundational: manufacture 5.56mm ammunition for the M-16 rifles the Singapore Armed Forces would use. The factory opened on 27 April 1968 at Boon Lay. This was the start of Singapore’s indigenous defence industry—and, in a very real sense, the earliest root of what would become ST Engineering.

Around CIS, Singapore began building an ecosystem of specialised, defence-adjacent companies that could absorb know-how, create skilled jobs, and steadily widen the country’s industrial base. In 1968, Singapore Shipbuilding and Engineering (SSE) was formed to develop local expertise in building and repairing naval vessels, starting with projects such as a 25m ferry boat completed in 1970. Singapore Electronic & Engineering Limited (SEEL) followed in 1969, providing electronic and electrical services for SAF equipment, including work on designing four missile gunboats in collaboration with Germany’s Fr Lurssen Werft. In 1971 came Singapore Automotive Engineering to maintain and refurbish heavy military vehicles. And in 1975, Singapore Aerospace Maintenance Company was set up to take over aircraft maintenance services for the Republic of Singapore Air Force that had previously been provided by Lockheed.

That last piece—the aerospace foothold—turned out to be the seed of a future giant. ST Engineering Aerospace began in 1975 as a military maintenance organisation. But the discipline required to keep complex aircraft flying reliably, under strict safety and operational constraints, is exactly the kind of capability that transfers well to commercial aviation. Singapore was learning to maintain advanced fighter jets and helicopters from scratch, absorbing technology and processes from foreign partners while building its own institutional muscle.

The bigger point is that the model started to work—and not just inside the defence perimeter. In 1984, the company won its first rail electronics contract, supporting the supervisory control and communication system for Singapore’s first MRT line. That was a proof point for Goh’s thesis: the same engineering discipline built for defence could be redeployed into civilian infrastructure.

Meanwhile, the defence side kept advancing too. In 1988, the FH-88 155mm howitzer—Singapore’s first indigenous howitzer—entered service. It wasn’t only a new weapon. It was a statement of capability: Singapore could design, develop, and manufacture sophisticated military hardware domestically.

To make all of this manageable—and scalable—Goh’s vision took institutional form in January 1974, when eight defence-related companies were brought under Sheng-Li Holding Company Private Limited. The name was a phonic adaptation of “胜利,” meaning “victory.” The structure would evolve over time, but the governing logic stayed consistent: commercial discipline applied to defence necessities, always scanning for technologies that could travel into export markets and civilian industries.

Even the end of empire fed the flywheel. The British withdrawal from Singapore in the early 1970s created both disruption and opportunity. SEEL, established in 1969, took over assets and electronics workshops previously operated by the Royal Navy, inheriting staff that included weapons maintenance personnel and seconded civilians. Singapore was, quite literally, building its defence industry using the infrastructure left behind by the departing colonial power.

What set Singapore apart from many countries that tried to build defence industries was this insistence on commercial viability. These companies weren’t meant to exist just to spend a budget. They were built to perform—then to compete—then, eventually, to export. That DNA is what made the next phase possible, when Singapore’s defence industrial base stopped being just a national insurance policy and started becoming a global business.

III. Going Commercial: The 1990s Transformation

By the late 1980s, Singapore’s defence-industrial experiment had worked—almost too well. The companies had real technical depth, they were keeping the Singapore Armed Forces running, and they were producing products that could travel beyond the island.

But the ceiling was obvious. Singapore’s domestic defence market would always be small. If these businesses were going to keep compounding, they needed customers who didn’t wear the same uniform. And Singapore’s reputation for competence and clean governance hinted at something valuable: trust at scale. In industries where safety and reliability are everything, that trust can be turned into contracts.

That’s the backdrop for what came next. 1990 effectively marked the start of the Singapore Technologies era, when the group’s businesses carried the Singapore Technologies family name and adopted the sunburst logo. More importantly, in 1990 and 1991, defence-related subsidiaries of Singapore Technologies were publicly listed—beginning the process of shedding the image of a purely government-owned complex.

Going public wasn’t just about raising money. It was about declaring, in the clearest possible way, that these companies would compete on commercial terms, with the scrutiny and accountability that public markets impose.

That same year, the group took a step that now looks inevitable, but at the time was a leap: it diversified into commercial aviation. In 1990, it set up its first commercial airframe maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) facilities—one in Singapore, and one in Alabama in the United States. The message was simple: this wasn’t going to be a defence-only capability. It was going to be an exportable service business.

The Alabama facility, in particular, was a credibility play. Operating an MRO shop in the United States meant meeting the expectations of the world’s most demanding aviation market. If airlines there were willing to trust you with their aircraft, that stamp of approval traveled.

The listing strategy rolled out in sequence. ST Aero and ST Shipbuilding listed first in August 1990. They were followed by ST Capital, ST Electronic & Engineering, ST Auto, and ST Computer Systems & Services. Each listing was another step away from being seen as a set of sheltered state-linked workshops—and another step toward being valued as a competitive set of engineering businesses.

Then came the defining corporate move of the decade. On 28 August 1997, Singapore Technologies Engineering Ltd—ST Engineering—was formed as a public-listed holding company through the merger of four listed entities: Singapore Technologies Aerospace Ltd, Singapore Technologies Automotive Ltd, Singapore Technologies Shipbuilding & Engineering Ltd, and Singapore Technologies Electronics & Engineering Ltd. The merger was executed via an exchange of existing shares in the four companies for shares in ST Engineering, under Section 210 of Singapore’s 1967 Companies Act.

In tandem, the limit on foreign ownership of ST Engineering shares was lifted. Singapore Technologies Pte Ltd—representing the broader Singapore Technologies group—held 65.9 per cent of the issued share capital of the new ST Engineering. The company debuted on the Stock Exchange of Singapore on 8 December 1997, and at the time became the largest industrial company listed on the main board.

This consolidation did a few important things all at once. It created scale: a single listed platform with capabilities spanning aerospace, electronics, marine, and land systems. It simplified the story for investors and customers. And lifting the foreign ownership limit was an unusually direct statement of confidence—Singapore was willing to open the doors and let global capital judge the business on performance.

A few years later, the ownership structure was simplified again. In October 2004, ST Engineering’s assets were transferred under Temasek Holdings, along with all companies under the parent holding company Singapore Technologies Pte Ltd, as part of a restructuring that dissolved the Singapore Technologies Group. The move was expected to deliver S$20 million of cost savings to Temasek by lowering the cost of debt, and it gave Temasek direct visibility over the listed companies that had previously sat under Singapore Technologies Pte Ltd as an intermediate holding company.

That restructuring essentially completed the modern setup. Temasek Holdings is ST Engineering’s largest shareholder, holding about 50.9% of total issued shares as at 31 December 2024. The remainder is widely held by institutions, funds, and retail investors. In practice, it’s a hybrid that’s shaped the company ever since: the stability of a committed anchor shareholder, paired with the discipline of being a real public company.

And the pivot turned out to be not just ambitious, but durable. Over the years—through the Asian financial crisis, the dot-com bust, SARS, the global financial crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic—the mix of defence and commercial work became a built-in shock absorber. When commercial aviation collapsed during COVID, defence work continued. When defence budgets tightened, commercial growth could carry momentum.

IV. Building Aerospace Dominance: The MRO Empire

If there’s one business that best explains ST Engineering’s commercial breakout, it’s aircraft maintenance, repair, and overhaul—MRO. What started in 1975 as a mission to keep the Republic of Singapore Air Force flying quietly turned into something much bigger: the world’s largest independent, third-party airframe MRO operation. That’s a startling outcome for a country with no homegrown aircraft manufacturing base and no natural advantage in aviation—just discipline, process, and a willingness to build the hard stuff.

By 2018, Aviation Week ranked ST Engineering Aerospace as the world’s largest independent third-party airframe MRO provider, with annual capacity of more than 13 million commercial airframe man-hours. That capacity isn’t a vanity metric. It’s what allows the company, at any moment, to have dozens of widebody and narrowbody aircraft in various stages of teardown, inspection, repair, and return-to-service—spread across hangars in Asia-Pacific, the U.S., and Europe.

In MRO, scale is strategy. The work comes with heavy fixed costs: hangars, tooling, inventories, certifications, and a workforce that has to meet relentless regulatory and safety standards. Once you’ve built that machine, every additional aircraft you can run through it improves economics and deepens the moat. Fewer competitors can justify the investment, and fewer still can keep quality and turnaround times consistent across a global network.

It also helps to understand why airlines buy this service in the first place. An airline can maintain aircraft in-house, pay the OEM, or outsource to a specialist. Over the last two decades, the industry has steadily leaned toward outsourcing—not because maintenance is optional, but because it’s expensive, operationally complex, and not what airlines want to be world-class at. They want aircraft in the air. MRO providers want to be world-class at getting them safely back there.

ST Engineering Aerospace built the kind of workforce that makes this model work. In 2021, it reportedly employed more than 8,500 certified engineers and administrative specialists worldwide, serving major airlines and freight carriers. That number matters less than what it represents: accumulated certifications, institutional knowledge, and a safety culture that compounds over decades—and is painfully slow for competitors to recreate.

The footprint kept expanding, including back at home. With the addition of the Changi Creek new facility, ST Engineering will have four airframe facilities in Singapore. The planned 84,000 square metre site is estimated to cost about S$170 million including construction and equipment. The first hangar bay is expected to be ready in mid-2025, with the remaining three by end-2026. When fully operational, it’s expected to add around 1.3 million man-hours of annual capacity—roughly a tenth of the group’s current global airframe MRO capacity. It’s a clear signal: even as the network goes global, Singapore remains the anchor.

Airframes are only part of the aerospace engine. The other half is, literally, engines—where the barriers to entry are even higher because OEM ecosystems are tightly controlled. ST Engineering became a LEAP MRO provider in 2020, offering quick-turn services for LEAP-1B and LEAP-1A engines in Singapore. In early 2023, it became the first independent provider in Asia to join CFM’s authorised MRO network for LEAP engines as a Premier MRO provider. That status opens the door to full-scope LEAP solutions—overhauls, proprietary parts repair technology, engine pooling and leasing—so operators can lower cost of ownership without sacrificing reliability.

But the most underappreciated aerospace business might be the one that looks the least like “maintenance”: passenger-to-freighter conversions.

This is where ST Engineering turns aging passenger jets into cargo aircraft—the kind of workhorse freighters that feed global logistics networks. Since 1996, the group has redelivered over 400 aircraft through its Passenger-to-Freighter, or P2F, programmes, making it one of the world’s largest and most experienced conversion houses. A big reason it can do this at scale is its joint venture with Airbus, Elbe Flugzeugwerke, which holds the Supplemental Type Certificates for key Airbus narrowbody and widebody conversion programmes, including A320/A321 and A330P2F.

Here’s the crucial distinction: many conversion providers rely on reverse engineering. ST Engineering and EFW’s Airbus P2F programmes are developed using OEM technical data. That’s not just “nice to have.” It means designs that are better optimised, easier to certify, and more reliable in service—because you’re not guessing what the original aircraft structure will tolerate. You’re building the conversion with the manufacturer’s own data.

The A320/A321P2F conversions sit at the heart of this advantage. These aircraft feature digital fly-by-wire technology and offer loading flexibility—including the ability to accommodate bulk cargo or containerised freight in the belly holds. And in a market where operators obsess over utilisation and loading efficiency, ST Engineering’s claim is straightforward: the Airbus P2F design uses OEM technical data, something competitors can’t replicate with reverse engineering alone.

Jeffrey Lam, President of ST Engineering’s Aerospace sector, put it in practical terms when discussing the A321P2F programme: working with Airbus enabled the team to develop a high-performance product and obtain the original EASA STC within a week of completing flight tests, while staying on schedule and maintaining safety and quality standards. He also framed the customer value plainly—helping airlines “breathe new life into underutilised aircraft” that would otherwise take a harsher hit in residual value.

And the demand backdrop has been supportive. The e-commerce boom has pushed more volume into air cargo networks, and freighter conversions offer a way to add capacity without waiting years for new-build aircraft. It’s a rare win-win in aviation: extend the useful life of an airframe while meeting growing cargo demand.

In other words, ST Engineering didn’t just build an MRO business. It built a global aviation lifecycle platform—airframes, engines, conversions—where each capability reinforces the next, and where scale and certification turn execution into durable advantage.

V. Inflection Point #1: The Satcom Play—iDirect & Newtec

ST Engineering’s satellite communications push is a great example of how the company tries to build global platforms: pick a mission-critical niche, buy real capability, then scale it with Singapore-style operational discipline. And the interesting part is that this bet started way earlier than most people remember—back in 2005, before “always-on connectivity” became a default expectation.

That year, ST Engineering acquired iDirect Technologies, a U.S. satellite communications network equipment provider, through its U.S. holding company Vision Technologies Electronics, Inc. (VTEE), for US$165 million. iDirect wasn’t a satellite operator; it was the company behind the ground infrastructure that makes satellite networks usable in the real world—modems, hubs, and the software layer that ties it all together. In other words: not the satellites, but the plumbing.

At the time, it looked like a relatively modest adjacency. In hindsight, it gave ST Engineering a foothold in a category with long runways: connectivity for places where terrestrial networks don’t reach, and for customers who can’t afford downtime—military, government, broadcast, maritime, and mobility.

Fourteen years later, ST Engineering decided it didn’t just want a foothold. It wanted a global position.

In 2019, ST Engineering announced that its subsidiary, Singapore Technologies Engineering (Europe) Ltd, had entered into an agreement to acquire 100% of Belgium-based Newtec Group NV for €250 million (about S$383 million), on a cash-free and debt-free basis, subject to closing adjustments. After the relevant approvals and conditions were met, ST Engineering completed the acquisition.

The strategic logic was about complementarity. Newtec brought a strong European presence and a reputation for bandwidth efficiency—technology that helps customers squeeze more usable throughput from expensive satellite capacity. It also had a proven range of cost-effective consumer satellite terminals, and it was among the first companies to successfully test over-the-air communication via Low Earth Orbit satellites. The company was positioned to benefit from the industry’s shift toward IP-based satellite broadcast, which matters for real-time content distribution.

The combined pitch was straightforward: iDirect plus Newtec could become a more complete satellite ground solutions provider. iDirect brought strength in networking and mobility; Newtec added efficiency innovations and broadcast capability. Together, the business could serve the full spectrum of satcom needs—from government and military, to commercial aviation, to maritime connectivity.

ST Engineering framed the merger as uniting decades of innovation focused on satellite’s hardest economic and technical constraints. The combined product portfolio continued under the iDirect and Newtec brands, and ST Engineering iDirect positioned itself as the world’s largest TDMA enterprise VSAT manufacturer, with leadership positions across broadcast, mobility, and military/government.

To raise brand visibility, Newtec was renamed as ST Engineering iDirect (Europe) NV. ST Engineering also stated at the time that the acquisition was not expected to have a material impact on earnings per share for the current financial year.

Then reality hit—because satcom didn’t stay still.

The market was disrupted by the emergence of LEO constellations like Starlink, which reshaped competitive dynamics in ways that weren’t fully anticipated. Against the backdrop of ST Engineering’s larger and steadily growing defence and aerospace engines, satcom became a laggard. The Urban Solutions & Satcom segment reported FY2024 revenue of $2.0 billion, up just 1% year-on-year. Within that, Satcom revenue fell 14% year-on-year to $300 million for the year—though in 4QFY2024, Satcom revenue rose 12% year-on-year.

Management has been direct about the work still to be done, while signaling it sees a path forward. CEO Vincent Chong said he was confident the business was recovering organically and didn’t need another bolt-on acquisition, nor did he suggest putting the unit up for sale—pointing to his track record of 16 divestments since 2016. “I don’t think anything is off the table,” he said, “but for satcom, we are really focused on turning around, transforming the business… our focus really is to turn the business around.”

That message started to show up in the numbers at the margin. ST Engineering noted early signs of improvement as the satcom transformation continued, including a 12% year-on-year revenue improvement in 4Q2024 and a marginally positive operating EBIT in the quarter, despite weaker full-year performance.

The satcom chapter captures both sides of ST Engineering’s M&A playbook. The company is willing to buy its way into global platforms—and not every bet plays out cleanly. But it also shows a different kind of discipline: acknowledging when the market has moved, resisting the urge to panic, and focusing on operational turnaround rather than either doubling down blindly or walking away too early.

VI. Inflection Point #2: The TransCore Bet—Becoming a Smart City Giant

If Newtec was a measured bet on satellite communications, TransCore was ST Engineering swinging for the fences in smart city infrastructure. In 2022, ST Engineering agreed to acquire TransCore from an indirect wholly-owned subsidiary of Roper Technologies for US$2.68 billion (about S$3.62 billion) in cash, on a cash-free and debt-free basis, subject to certain purchase price adjustments. It was, by far, the biggest deal in the company’s history—and a statement that “smart city” wasn’t a side business anymore. It was a platform.

TransCore is a North American transportation technology company with more than 80 years of history. Its bread and butter is the unglamorous, mission-critical plumbing of modern mobility: electronic toll collection, congestion pricing, Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS), the back-office systems that reconcile billions of charges, and RFID products that identify vehicles at speed. If aviation MRO is about keeping aircraft safely in the air, this is about keeping cities moving—reliably, securely, and at scale.

And TransCore came with a marquee proving ground: Manhattan.

TransCore was contracted to deliver New York City’s congestion pricing project in Manhattan—the first such scheme in the United States. New York City’s Central Business District Tolling Program launched in January 2025, a watershed moment in American transportation policy. For ST Engineering, it meant something even more concrete: overnight, the company found itself at the center of a high-profile experiment that other U.S. cities would be watching closely.

The project also attracted political noise. TransCore faced backlash and accusations about ties to foreign entities. ST Engineering CEO Vincent Chong responded by emphasizing full compliance and robust security safeguards—an important point, because in this line of work, trust isn’t marketing. It’s the product.

Strategically, the fit was clean. TransCore’s tolling, congestion pricing, and ITS capabilities complemented ST Engineering’s existing smart, integrated mobility offerings, turning them into a fuller, end-to-end suite. ST Engineering was already active at global scale—over 700 smart city projects across more than 130 cities, including 60 intelligent road transportation projects in more than 20 cities. TransCore didn’t replace that footprint; it pulled it into North America in one move, with an incumbent that already had deep relationships with U.S. state transportation authorities.

TransCore also brought a business model ST Engineering likes: sticky, recurring revenue. More than half of TransCore’s business is recurring, with a contract renewal rate of 95%. That reflects the reality of tolling and traffic systems: once you’re embedded, you don’t get ripped out lightly. Switching vendors isn’t like changing software subscriptions; it’s a high-stakes, multi-year operational transition with public scrutiny and real-world consequences.

The numbers supported the thesis. TransCore generated US$565 million in revenue in 2020 and had a backlog of US$1.2 billion as of 31 July 2021. It was profitable too, reporting profit before tax and non-controlling interests of around US$54 million for the first half of fiscal 2021.

On 18 March 2022, ST Engineering announced it had completed the acquisition of TransCore. The company expected the deal to be cash flow positive from the first year and earnings accretive from the second year post-acquisition.

Then there’s the cross-sell, which runs in both directions. ST Engineering could bring ITS solutions—smart road junctions, transportation operation centres, and road traffic optimisation systems—into the North American market. TransCore, in turn, could take tolling and congestion pricing capabilities into Southeast Asia, where ST Engineering already has a strong presence with governments and infrastructure operators.

TransCore’s scale is what makes all of this hard to copy. The company has about 1,900 staff and processes roughly 10 billion transactions annually across nine million accounts. It serves 11 of the 15 largest toll agencies in the U.S. That installed base isn’t just revenue—it’s switching costs, operational know-how, and a decades-deep set of relationships. In smart mobility, that’s the moat.

VII. The 2014 Corruption Scandal—And What It Revealed

For all of ST Engineering’s reputation for process, discipline, and Singapore-style governance, 2014 delivered a hard reminder: even systems-built companies can develop blind spots. And when the work is contract-driven, relationship-heavy, and happening far from headquarters, small compromises can compound for years before anyone outside the room sees them.

In 2014, ST Engineering and two subsidiaries—ST Engineering Marine and ST Engineering Aerospace—were swept into one of Singapore’s largest corruption cases, following investigations by the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB). The allegations centered on bribery tied to ship-repair contracts, and they traced back across a long stretch of time: 2004 to 2010.

In December 2014, former ST Engineering Marine and ST Engineering Aerospace president Chang Cheow Teck was charged with conspiring with two subordinates to offer bribes in return for ship-repair contracts during that period. The case was part of a broader set of proceedings involving multiple former senior executives from the marine business.

The picture that emerged was messy, and it was not small. Beyond Chang, other former executives faced charges spanning alleged bribery, falsified petty-cash claims, and accounting falsification. Among those implicated was former group financial controller and senior vice president of finance Ong Teck Liam, who faced numerous counts related to false claims and later pleaded guilty to a subset of charges. Several other former ST Engineering Marine senior leaders also pleaded guilty to subsets of charges and received fines and jail sentences. The details varied, but the throughline was consistent: the misconduct wasn’t a one-off incident. It played out over years and touched multiple layers of seniority.

Another senior figure, See Leong Teck, a former CEO and president of ST Marine, was charged with corruption as well. He was accused of bribing agents connected to Hyundai Engineering and Construction Ltd and Myanma Five Star Line between 2004 and 2007 to secure ship repair contracts. In December 2016, See was sentenced to 10 months’ jail and a $100,000 fine.

Chang’s case took a different turn. The corruption charges against him were eventually withdrawn, and in January 2017 he pleaded guilty to “failing to use reasonable diligence in performing his duties,” receiving a 14-day detention order.

If you zoom out, a few things stand out.

First, the duration and breadth of the conduct suggested more than individual moral failure. When issues recur over many years and involve multiple senior leaders, that’s usually a control and culture problem—weak oversight, weak expense governance, weak escalation paths, or all of the above.

Second, ST Engineering’s posture was cooperation rather than combat. The company stated that ST Marine had been extending its fullest cooperation to CPIB from the beginning of the investigation, which had started years earlier.

Third, the episode reinforced something important about Singapore as a system: the CPIB pursued the case aggressively regardless of ST Engineering’s status as a government-linked enterprise. In a country where clean governance is part of the national brand, that matters—because the credibility of the rules depends on who they apply to when it’s uncomfortable.

The scandal’s center of gravity was the marine business. And later, that business would become an exit. ST Engineering sold its U.S. marine business, VT Halter Marine, in 2023—closing the chapter on a sector that had delivered real capability, but also significant reputational damage.

For investors, the lesson isn’t that ST Engineering is uniquely flawed. It’s that no amount of national reputation or engineering rigor immunizes a company from misconduct—especially in contract businesses where entertainment, intermediaries, and opaque expense categories can become a parallel currency. The differentiator is what happens after: whether the institution resists transparency, or absorbs the hit, cleans house, and changes direction. In ST Engineering’s case, the arc of cooperation, accountability for individuals, and an eventual strategic exit from the problem area pointed to an organization that treated the scandal as a failure to be corrected—not a story to be buried.

VIII. The Modern Business Model: Three Pillars

After everything we’ve covered—the defence roots, the commercial pivot, the MRO machine, the satcom bet, the TransCore swing—you can start to see ST Engineering less as a conglomerate and more as a repeatable system. Today, that system shows up in three operating segments that look different on the surface, but share the same underlying DNA: engineering-driven execution in mission-critical environments.

The company operates through Commercial Aerospace, Urban Solutions & Satcom, and Defense & Public Security segments. Commercial Aerospace is the aviation lifecycle platform: maintenance, repair, and overhaul for airframes, engines, and components, plus OEM manufacturing for things like nacelles and composite floorboards, passenger-to-freighter conversions, and aviation asset management. Urban Solutions & Satcom is the city-and-connectivity stack: smart mobility, utilities, infrastructure, and urban environment solutions alongside satellite communications. Defense & Public Security covers defence, public safety and security, critical information infrastructure, and related solutions.

In 2024, the results showed what this structure is designed to do: compound through cycles. Full-year revenue grew 12% to more than $11 billion. EBITDA rose 11% to $1.6 billion, and EBIT climbed 18% to $1.1 billion. Profit before tax increased 23% to $863 million, while net profit grew 20% to $702 million.

Under the hood, the segments told slightly different stories.

Commercial Aerospace revenue grew 12% to $4.4 billion, and EBIT improved 19% to $400 million. The segment secured $4.7 billion of new contracts in 2024. The simple driver here is demand: aviation continued its recovery from COVID, and airlines and operators kept leaning on third-party MRO capacity to keep fleets flying.

Defense & Public Security grew even faster. Revenue rose 16% to $4.9 billion, with EBIT up 15% to $636 million. The segment secured $5.3 billion of new contracts in 2024. In a world of heightened geopolitical tension and rising defence budgets, this part of the portfolio has been a powerful engine—exactly the kind of stabilizer Singapore originally built these capabilities for, now operating at global scale.

What’s notable is that the company improved its financial footing while carrying the weight of large deals like TransCore. Borrowings fell 5% year-on-year, from $6.1 billion to $5.8 billion, and gross debt to EBITDA improved from 4.2 times to 3.6 times.

ST Engineering also benefits from very strong credit ratings—Aaa by Moody’s and AA+ by Standard & Poor’s—which give it ready access to additional borrowing when needed. Those ratings reflect a combination of operational stability and the institutional backing that comes with being a Temasek-linked national champion.

Cash generation strengthened materially too. For the year ended 31 December 2024, the group generated operating cash flow of $1.7 billion, up 46% year-on-year. And it got more efficient: unit operating expenses (per unit revenue) fell from 11.4% in 2023 to 10.6% in 2024, reflecting continual focus on cost management, productivity, and operational efficiency.

Then there’s the clearest “Acquired-style” metric for a business like this: backlog. With new contract wins and adjustments for revenue delivery, ST Engineering ended 2024 with an order book of $28.5 billion, and expected to deliver about $8.8 billion from that in 2025.

That order book has grown dramatically in a short time. It stood at S$14.4 billion in 2020, and nearly doubled to S$28.5 billion by end-2024. Through a pandemic, supply chain disruptions, and global uncertainty, ST Engineering kept winning long-dated work—an indicator not just of demand, but of trust.

Finally, the workforce tells you what kind of company this is. As of 2024, ST Engineering employed about 27,000 people, with around 19,000 in engineering and technical roles. When roughly seventy percent of your workforce is technical, it’s a reminder that the product here isn’t branding or distribution. It’s execution—done safely, repeatedly, and at scale.

IX. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

To understand why ST Engineering has held up across so many cycles—and why it keeps winning long-dated, high-trust work—you have to look at two things at once: the structure of the markets it plays in, and the specific advantages it has built over decades.

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

In ST Engineering’s core businesses, the “easy” part is deciding you want to compete. The hard part is surviving long enough to matter.

Start with aircraft MRO. You don’t just rent a warehouse and hire mechanics. You need purpose-built hangars, specialized tooling, deep inventories, and years of work to earn and maintain regulatory approvals from authorities like the FAA and EASA. More than that, you need the kind of reputation airlines only give after repeated performance—because the downside of getting maintenance wrong isn’t an unhappy customer. It’s a grounded fleet, or worse.

That’s why scale becomes its own barrier. With global airframe MRO capacity of around 13 million man-hours supported by 10 hangar facilities across Asia-Pacific, the U.S., and Europe, ST Engineering sits at the top of the independent market. Replicating that position would take enormous investment—and, just as importantly, time.

Defence is even more unforgiving. Trust with government customers is earned over decades, often wrapped in national security requirements and, at times, classified technology. New entrants don’t just need a better product; they need permission to be considered. ST Engineering’s position is reflected in its global standing—it was ranked number 58 on SIPRI’s list of the world’s top 100 defence manufacturers in 2023—but the real barrier is the long history behind that rank.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

In aerospace, the biggest supplier power often sits with the engine OEMs. Companies like CFM and Pratt & Whitney control critical parts of the ecosystem, from technical data to approved repair pathways. ST Engineering has worked to blunt that leverage by embedding itself in the supply chain through partnerships.

For example, Turbine Overhaul Services (TOS)—a joint venture in which ST Engineering holds a 49% share—specialises in repair of gas and steam-related components. Turbine Casting Services (TCS), where it holds 24.5%, specialises in the repair of PW4000 turbine airfoils using advanced coating technologies. These aren’t just vendor relationships. They create mutual dependence: the OEMs need capable, certified repair capacity, and ST Engineering needs access and legitimacy inside the engine ecosystem.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

ST Engineering’s customers know how to negotiate.

Airlines are famously cost-conscious, and governments buying defence systems have strong leverage by default. But the company’s protection comes from friction—real operational friction, not contractual fine print.

Switching an MRO provider isn’t like switching an IT vendor. It means shifting maintenance programmes, qualifying processes, ensuring compliance, retraining teams, and taking on execution risk with high-value assets. Those realities make customers price-sensitive, but not purely price-driven—especially under multi-year contracts where reliability and turnaround time matter as much as headline cost.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE

The main “substitute” in MRO is bringing the work in-house. In theory, an airline can do that. In practice, the industry has steadily moved toward outsourcing to specialists because maintenance is capital-intensive, heavily regulated, and hard to run at high utilization unless you have massive scale.

In smart city solutions, substitution risk looks different. Technology evolves—tolling methods change, sensor stacks improve, software architectures shift. But installed infrastructure, long procurement cycles, and operational complexity slow down replacement. That’s why an embedded position, like TransCore’s, is strategically valuable: even when technology changes, the system owner tends to evolve what’s installed rather than rip it out.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

These are competitive markets, but they’re not chaotic ones.

In MRO, ST Engineering goes up against credible peers like HAECO, SIA Engineering, and Lufthansa Technik. Rivalry is real, yet generally disciplined—because certifications, capacity, and safety culture aren’t things you can “blitzscale.” Competitors tend to carve out niches and defend them.

In defence, rivalry varies by domain and geography. Some segments are fiercely contested, while others are shaped by long relationships and platform continuity. In either case, incumbency and credibility are hard currency.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: STRONG

This is the most obvious power. Large fixed costs—hangars, tooling, certifications, workforce training—get spread across huge volumes. Scale also improves procurement economics in parts and materials. The result is not just lower unit cost, but the ability to offer capacity and turnaround reliability that smaller competitors struggle to match.

Network Effects: MODERATE

There aren’t classic consumer-style network effects here, but the global footprint creates an operational version of one. Airlines with multi-continent operations can use ST Engineering facilities across regions, reducing logistical headaches and creating a practical “follow-the-sun” advantage that regional MRO providers can’t replicate.

Counter-Positioning: STRONG

ST Engineering’s aerospace platform—airframe MRO at global scale plus Premier MRO status for CFM LEAP engines—sits in a spot incumbents struggle to attack. For airlines, building independent MRO capability at this scale would mean taking capital and focus away from the core airline business. For OEMs, enabling an independent player too aggressively can cannibalize their own aftermarket economics. That structural tension gives ST Engineering room to operate and grow.

Switching Costs: STRONG

These businesses are built on integration. MRO contracts embed workflows, documentation, quality systems, and people trained on specific fleets. Defence programmes embed training, sustainment infrastructure, and systems integration around particular platforms. Smart city infrastructure typically runs on long lifecycles measured in decades. Once ST Engineering is in, replacement is expensive, slow, and risky.

Branding: MODERATE

This isn’t a consumer brand, but in regulated, mission-critical markets, reputation is a form of brand. “Singapore” carries associations of quality and reliability, and ST Engineering’s track record matters deeply with governments and enterprise buyers. It’s not the kind of brand that drives impulse purchasing—it’s the kind that wins trust-based contracts.

Cornered Resource: STRONG

One of ST Engineering’s most defensible advantages is in passenger-to-freighter conversion. Through its Airbus joint venture, EFW, its Airbus P2F programmes are developed using OEM technical data rather than reverse engineering. That access is not something a competitor can recreate by spending more; it’s structurally exclusive. Add decades of certifications and accumulated know-how, and you get a resource advantage that’s both rare and hard to dislodge.

Process Power: STRONG

This is the quiet superpower behind everything else. ST Engineering has been steadily modernising its MRO operations through digitisation and automation, pushing safety, quality, and efficiency benchmarks higher over time. That kind of continuous improvement culture—built across fifty-plus years—doesn’t show up in a single product launch. It shows up in throughput, reliability, and cost discipline that compound year after year.

X. Growth Strategy & Future Vectors

After building moats in aerospace and defence, and then buying its way into smart mobility, ST Engineering’s next act is essentially the same playbook—just written larger. At an investor day on March 18, management laid out five-year targets through 2029 that aim to push the group into a new weight class.

The headline goal: reach S$17 billion in revenue by 2029, growing more than 2.5 times the pace of global GDP. The logic is familiar, and it tracks the portfolio. Geopolitical tension remains a tailwind for defence. Aviation continues normalizing post-COVID, with more aircraft and engines entering fleets and needing maintenance. And across sectors, customers are spending more on digitalisation—exactly the kind of “mission-critical systems” work ST Engineering likes.

Sell-side analysts largely bought into the plan. They highlighted the implied revenue CAGR of about 9%, and an ambition for net profit to grow even faster—by as much as five percentage points above revenue growth. In plain English: management is saying it won’t just get bigger; it expects to get more efficient as it scales.

The segment targets show how they think they’ll get there.

Commercial Aerospace is targeting S$6 billion of revenue by 2029, roughly a 7% CAGR. The drivers aren’t exotic: continued traffic recovery, more MRO capacity coming online, and sustained demand for passenger-to-freighter conversions.

Defence & Public Security is where the plan raised eyebrows—in a good way. The FY2029 defence revenue target is S$7.5 billion, which analysts called a “positive surprise,” reading it as a signal of management’s confidence that elevated global defence spending won’t be a short cycle.

Urban Solutions & Satcom is expected to be the faster international growth engine, with management targeting double-digit revenue CAGR outside Singapore. Within that, smart city revenue is projected to reach S$4.5 billion by 2029, up from S$2.7 billion in 2024. The growth priorities here include the digital business, smart mobility—where TransCore is the centerpiece—and continued expansion of the “platform” approach in major cities.

If revenue is the top line of the story, cost is the hidden lever. ST Engineering is targeting around $1 billion of additional cost savings by 2029. Analysts have pointed to this as a key support for margin expansion assumptions—one estimate calls for operating margin to rise gradually to 9.8% in FY2029 from 8.9% in FY2024.

For shareholders who care less about long-term targets and more about near-term cash, management also added clarity on dividends. The company announced a progressive dividend plan after raising total dividends for 2024 to S$0.17 from S$0.16 the year before. For 2025, it plans to increase the annual dividend to S$0.18, made up of three interim payments of S$0.04 and a final dividend of S$0.06. Management also signaled that if net profit rises steadily, it intends to return about one-third of the year-on-year increase as incremental dividends.

Early 2025 execution gave the plan some credibility. In the first half of 2025, the group delivered revenue of $5.92 billion, up 7% year-on-year, with growth across all three segments. EBITDA rose 11% year-on-year to $871 million.

Contract momentum stayed strong, too. ST Engineering secured $9.1 billion of new contracts in 1H2025. In 2Q2025 alone, it won $4.7 billion—split across Commercial Aerospace, Defence & Public Security, and Urban Solutions & Satcom. After revenue delivery, the order book grew to $31.2 billion as at 30 June 2025, and the group expected to deliver about $5.0 billion from that backlog in the second half of 2025.

The market noticed. ST Engineering became the top-performing Straits Times Index component stock in early 2025, benefiting from the global re-rating of defence-exposed names amid rising geopolitical uncertainty. The share price surged through early May before easing as broader market sentiment shifted.

The takeaway isn’t that every target will land perfectly on schedule. It’s that ST Engineering is now mature enough—and diversified enough—to make a credible case for compounding: growth powered by defence demand, aviation throughput, and smart city infrastructure, with cost discipline designed to turn scale into profit.

XI. Bull Case vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

The bull case for ST Engineering is a simple story with three big tailwinds: more flying means more aircraft maintenance, a more dangerous world means more defence spending, and more crowded cities mean more demand for smart mobility infrastructure.

Start with commercial aerospace. Over long stretches of time, air travel has grown steadily, and that growth pulls MRO along with it—aircraft still need checks, repairs, and overhauls regardless of which airline logo is on the tail. ST Engineering’s advantage is position and scale: as the world’s largest independent third-party airframe MRO provider, it’s set up to capture an outsized share of that demand. On top of that, its passenger-to-freighter conversion business has its own supportive backdrop: e-commerce has increased the need for air cargo capacity, while many cargo fleets are aging and need replacement or conversion options.

Then there’s defence. The security environment has shifted in a way that looks less like a cycle and more like a reset. ST Engineering expects the addressable international defence market—where it sees potential for its solutions—to be above US$11 billion (about $14.7 billion) over the next five years. European rearmament following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, ongoing Middle East security pressures, and rising Indo-Pacific tensions all point to sustained demand for the kinds of systems, platforms, and support work that defence customers buy from a company like ST Engineering.

Finally, smart cities—where TransCore is the centerpiece. The acquisition puts ST Engineering in the middle of congestion pricing, electronic tolling, and intelligent transportation systems, especially in North America. Manhattan’s congestion pricing program is the highest-profile proof point: if it works and becomes a template, other cities could follow. And because tolling and traffic systems tend to run for decades once installed, a first-mover position can translate into long-lived contracts and recurring revenue.

All of this is supported by something investors love: visibility. By the end of 2024, ST Engineering had a record order book of $28.5 billion—roughly double pre-COVID levels—providing a clearer runway for near-term revenue than most industrial businesses ever get.

The Bear Case

The bear case is that this is a complex, government-linked company operating in cyclical industries, with real geopolitical and execution risk—and the stock price has already started to reflect a lot of optimism.

First, governance. Temasek’s majority stake is a feature for stability, but a bug for some investors. The concern isn’t day-to-day management; it’s that major decisions could, in theory, tilt toward national objectives rather than maximizing minority shareholder returns. On top of that, the Special Share held by Singapore’s Minister for Finance gives the government additional veto rights over certain ownership-related changes.

Second, geographic and political exposure. About 30% of group revenue comes from the U.S., and management has been watching for knock-on effects from geopolitical events and trade tariffs under Trump’s presidency. In practice, that means risks like shifting export controls, tariff regimes, and “buy American” procurement preferences that could change competitive dynamics.

Third, not every platform bet has worked cleanly. The satcom business has underperformed, and the numbers make that visible: satcom revenue fell 14% year-on-year to $300 million for the year. If the turnaround doesn’t stick, it raises uncomfortable questions about integration and capital allocation—not because satcom is the whole company, but because it’s a reminder that M&A is only as good as what you can operationalize afterward.

Then there’s the macro reality. Aviation is cyclical: recessions cut flying, which pressures MRO demand. Defence spending can rise quickly—and it can also change with elections, fiscal constraints, or shifting priorities. Smart city budgets depend on government balance sheets and political will, both of which can be fragile when public sentiment turns.

Lastly, valuation. ST Engineering’s share price surged sharply in early 2025—at one point gaining as much as 64.6% to $7.67 on May 9. After that kind of move, expectations get baked in. The market has less patience for stumbles, and the margin for error narrows right when execution risk is most visible.

XII. Key Metrics to Watch

If you want a simple dashboard for whether ST Engineering is executing, you don’t need to track dozens of line items. Three signals will tell you most of what matters.

Order Book Growth and Book-to-Bill Ratio

The order book is the closest thing ST Engineering has to a forward-looking revenue guide. After new contract wins and revenue delivery, the company ended 1H2025 with an order book of $31.2b as at 30 June 2025. The key is direction, not just size: are new wins coming in faster than work is being delivered? When book-to-bill stays above 1.0x, it suggests the backlog is growing and momentum is building. When it slips below, it can mean demand is softening, execution is pulling forward revenue, or both.

Segment EBIT Margins

Growth is only half the story. The other half is whether ST Engineering can turn scale into better economics. Management’s plan implies EBIT margin expansion over time—toward 9.8% by 2029 from 8.9% in 2024. If margins rise steadily, it supports the thesis that cost savings and operational leverage are real. If margins stall or compress, it’s usually a sign of pricing pressure, integration drag (especially from acquisitions), or execution issues inside the segments.

Commercial Aerospace MRO Capacity Utilization

Aviation MRO is a fixed-cost machine: hangars, certifications, tooling, and trained labor don’t get cheaper just because demand dips. That makes utilization a quiet but decisive metric. As ST Engineering expands capacity, what matters is how much of that capacity is actually filled with paying work—and at what pricing. Strong utilization typically signals healthy demand and decent pricing power; weak utilization can be an early warning that the aerospace engine is running below its potential.

XIII. Final Observations

ST Engineering is a rare kind of outcome: a government-linked company from a small nation that still managed to build truly world-class capabilities across multiple engineering domains. Its arc—from manufacturing ammunition in 1967 to helping power Manhattan’s congestion pricing system in 2025—mirrors Singapore’s own transformation, and shows what deliberate industrial policy can produce when it’s paired with commercial discipline.

For investors, the appeal is straightforward. ST Engineering offers exposure to three big currents that are likely to stay in the global budget: aircraft flying again and staying in the air longer, defence spending rising in a more unstable world, and cities investing in infrastructure that makes mobility smarter and more efficient. Temasek’s majority ownership adds stability and an element of institutional backing, while the public listing forces the organization to operate in the open—reporting results, explaining capital allocation, and living with market scrutiny.

“We delivered a very strong set of results in 2024 despite an uncertain and challenging environment. We are confident that our strong fundamentals will continue to position us well, even as we confront a fast-changing landscape. We have a robust order book and a competitive market position which will underpin our continuing revenue growth and performance.”

The real question isn’t whether ST Engineering is a good business. The question is whether today’s expectations line up with what the company can actually deliver—whether management can execute on its 2029 ambitions, and whether the tailwinds it’s riding hold up long enough to matter. Those calls come down to each investor’s framework and tolerance for risk.

But zooming out, the broader point is hard to ignore: ST Engineering deserves to be on the radar of investors who rarely look at Singapore-listed companies. Its story—how a country’s survival mindset turned into exportable, compounding industrial capability—has lessons well beyond any single stock. And as a company, it’s proof that engineering excellence, disciplined capital allocation, and patient long-term thinking can create durable value over decades, regardless of where the headquarters happens to be.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music