South32: From BHP's "Second-Tier" Spinoff to Energy Transition Pioneer

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

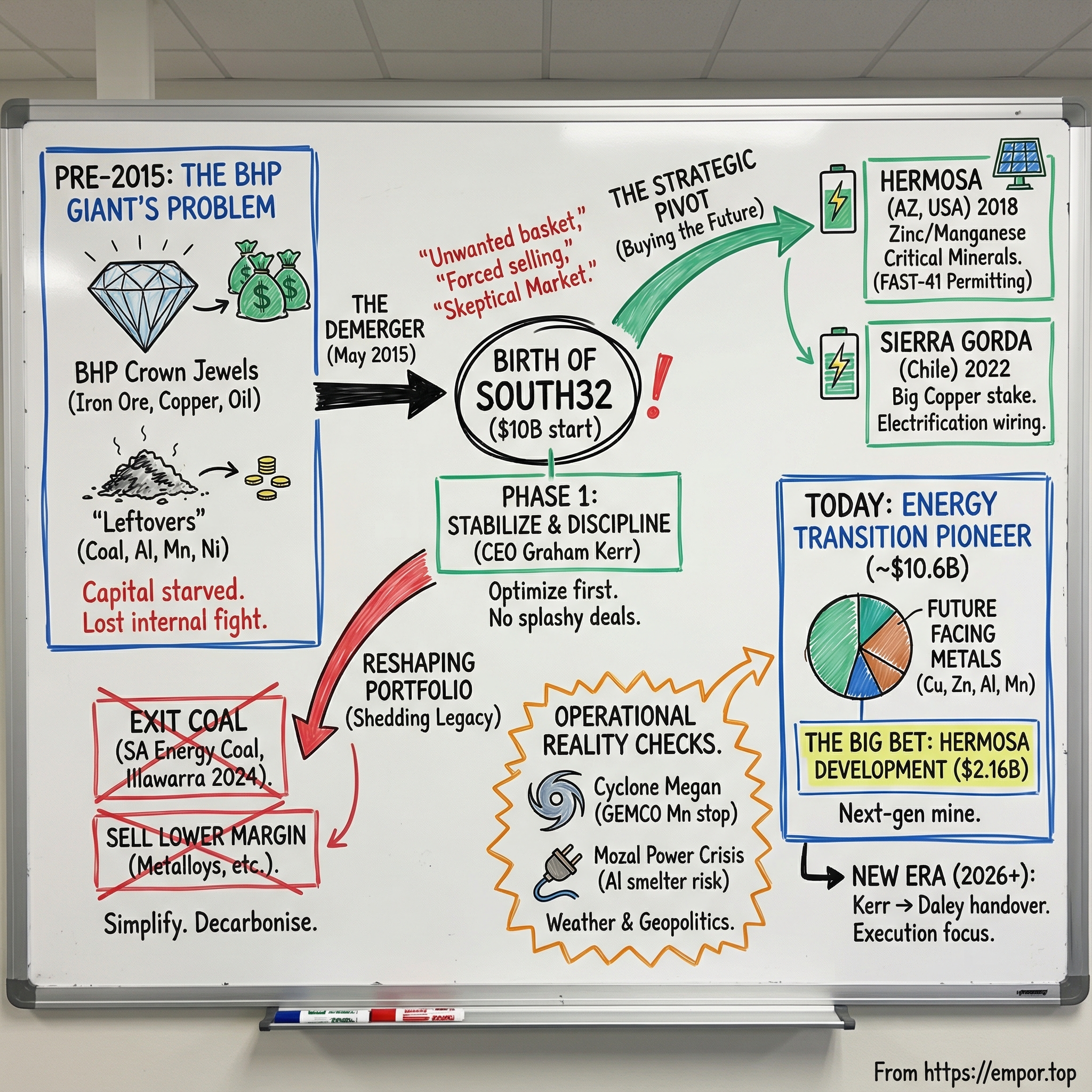

Picture May 2015 on the Australian Securities Exchange. BHP, the world’s largest miner, has just pulled off a rare move at massive scale: it spun out twenty-two assets into a brand-new company and, in effect, handed shareholders a second stock certificate and said, you deal with it.

The market’s reaction was… polite, at best. CMC Markets chief strategist Michael McCarthy looked at the combined value of BHP plus the newco and said, “it’s pretty clear the market’s ascribed a small premium to the spinoff.” And he captured the mood in one line: “Some are viewing this as the unloved part of BHP’s portfolio… (and) it’s also the part where valuations are at multi-year lows.”

The skeptics weren’t wrong about what was inside the box. This wasn’t iron ore in the Pilbara or a world-class copper franchise. It was the miscellaneous drawer: thermal coal, aluminium, manganese, zinc. Assets that, inside a giant like BHP, rarely won the internal fight for attention and capital. Overnight, shareholders owned the same underlying mines and smelters as before, just split across two tickers. BHP kept the crown jewels. South32 got the rest.

South32 listed at $2.13 a share, the low end of expectations. Even so, the scale was undeniable: it instantly became Australia’s third-largest listed miner, worth more than $10 billion on day one. But that price also broadcasted a message. Plenty of BHP investors didn’t want exposure to this mix of commodities at all. They sold their South32 shares as soon as they could, and that wave of selling hung over the stock for months.

Now jump forward a decade. The “basket of unwanted assets” didn’t stay unwanted. By December 2025, South32’s market cap stood around $10.61 billion USD. The market cap is a datapoint, not the plot. The plot is what the company did with the hand it was dealt: returning billions to shareholders through dividends and buybacks, exiting coal, and steadily repositioning itself toward the metals that matter in a lower-carbon economy.

So this episode is about three things. First, the art—and the hidden mechanics—of the corporate spinoff. Second, the patience and discipline it takes to reshape a portfolio for big, slow macro trends. And third, mining’s constant identity crisis: how do you fund and run legacy assets while trying to become “future-facing” at the same time?

South32 matters because it offers a possible template for how a modern miner navigates the energy transition in real life, not in a slide deck. It has sold down carbon-intensive and lower-margin operations, and leaned harder into commodities like copper, zinc, aluminium, and manganese—materials that sit underneath electrification, grids, and industrial decarbonisation. Whether that bet pays off will hinge on the unglamorous realities of mining: permitting, power, weather, geopolitics, and the fact that the best deposits are always harder to find than the last.

And to understand why South32 even existed in the first place, we have to rewind past 2015 to 2001—when an Australian icon and a British miner merged into a diversified supermajor, and unknowingly set the stage for the breakup that would come fourteen years later.

II. The Parent Company: BHP Billiton's Giant Problem

To understand South32, you first have to understand the giant that created it—and the specific kind of problem only giants get.

BHP Billiton was born in June 2001, when Australia’s Broken Hill Proprietary Company Limited—BHP, “the Big Australian”—merged with Billiton plc in a dual-listed structure spanning the ASX and the LSE. On paper, it was the perfect mining marriage: two diversified resource companies combining into one diversified supermajor, big enough and broad enough to ride out the inevitable boom-and-bust cycles of commodities.

Both lineages ran deep. BHP dated back to 1885, when it was incorporated to operate the silver and lead mine at Broken Hill in western New South Wales. Billiton had its own long arc, and by 1997 it was a constituent of the FTSE 100. When the merger closed, the new group was billed as the world’s leading diversified resources company, with a low-cost, long-life asset base spread across commodities and countries—and, based on closing prices at the time, an enterprise value around US$38 billion.

For a while, that pitch looked prophetic. The 2000s commodity boom—supercharged by China’s industrial appetite—made “diversified” feel like “unstoppable.”

But as the cycle matured, the portfolio started to reveal its hierarchy. In reality, BHP Billiton’s identity—and its economics—were dominated by a core quartet: iron ore, copper, metallurgical coal, and oil. Everything else mattered less to the group’s results, and that imbalance created the classic diversified-company trap. Investors who wanted a clean bet on BHP’s crown jewels had to take the whole bundle: aluminium smelters, manganese, nickel, thermal coal—businesses with different cost structures, different cycles, and in some cases, growing ESG pressure.

That tension showed up in two ways.

First, valuation. The market increasingly treated the company as less than the sum of its parts—the conglomerate discount—because the story was harder to underwrite and the “other” divisions diluted the appeal of the best ones.

Second, and more importantly, capital allocation. Inside a mega-miner, every project competes for attention, talent, and dollars. And when the choice is between expanding a top-tier iron ore operation and spending on a lower-return, less strategic asset, the internal answer tends to repeat itself year after year. The second-tier businesses don’t usually get dramatic cuts. They get something quieter: deferred upgrades, postponed growth, and the slow realization that the best people gravitate toward the divisions the company actually talks about.

By 2014, management faced a fork in the road. They could sell these assets one by one—messy, slow, and unlikely to produce clean outcomes—or they could separate them into their own company and let them stand on their own, with their own balance sheet and priorities. They chose the clean break.

When the proposal finally landed, it was presented as a win-win. In March 2015, the BHP Billiton board urged shareholders to back the demerger, arguing it would sharpen BHP’s focus on its core and give the carved-out assets the attention they couldn’t get inside the mothership.

The subtext was obvious, though. These weren’t the businesses BHP saw as its future. They were the ones it wanted off the stage.

And that’s the bet South32 was born from: not that the assets were secretly perfect, but that independent management and independent capital allocation could make them better than they’d ever been as supporting characters inside the world’s biggest miner.

III. The Demerger: Birth of South32

The Strategic Logic

On August 19, 2014, BHP Billiton made it official: it would carve out a new company in what was set to become one of the biggest mining demergers in years. The stated logic was clean and familiar. Simplify the parent, unlock value, and give the “other” assets a fresh start as a globally diversified metals and mining company.

But the real story was capital allocation.

Inside BHP, these operations were always competing with the heavyweights. Every budgeting cycle, aluminium, manganese, nickel, and thermal coal were up against expanding iron ore or funding petroleum. And in that internal fight, the outcome was predictable. Management argued that the assets weren’t inherently bad businesses—they were just businesses that couldn’t win attention inside a supermajor. As a standalone company, they could finally be run on their own terms, with their own strategy and their own priorities.

BHP’s board also leaned hard on one detail that mattered a lot more than it sounded: South32 would start with a strong balance sheet. Many spinoffs get “born” with debt shoved onto them. South32, by contrast, would begin life with minimal leverage. That would give it breathing room—flexibility to invest, to weather a downturn, and, if the right opportunity showed up, to play offense instead of just surviving.

The Name and Identity

Then came the part every corporate carve-out has to get right: the name.

BHP went geographic and a little abstract with South32, a reference to the latitude linking the company’s core footprint across Australia and South Africa. The 32nd parallel south runs through both, and the name quietly communicated what the asset mix actually was: a Southern Hemisphere miner with regional centers in Perth and South Africa, built to manage far-flung operations without pretending to be another BHP.

It was also meant to place the company in a very specific slot in the market: big enough to matter, but not a behemoth. A mid-tier diversified miner sitting just below the giants and far above the juniors.

The Listing

The shareholder vote was decisive. BHP said 98.05 percent voted in favor of splitting out the twenty-two assets into the new business—mining’s biggest such deal in almost a decade.

On May 18, 2015, South32 debuted on the ASX, with secondary listings in London and Johannesburg, exactly as planned. The Johannesburg listing mattered because South Africa wasn’t a side note in this portfolio—it was foundational, with major assets including the Hillside aluminium smelter and multiple manganese operations.

Overnight, South32 went from a concept on a slide to a Perth-headquartered, locally owned public company—new ticker, new board, new mandate, and the same set of assets that, until that morning, had been living in BHP’s shadow.

The Skepticism

But the market didn’t greet South32 like a fresh growth story. It greeted it like an inconvenient distribution.

Most BHP shareholders hadn’t asked for this. If you owned BHP for iron ore and copper, you probably weren’t excited to suddenly hold thermal coal, manganese, and aluminium by default. And that dynamic created an immediate technical problem: forced selling.

UK institutions that couldn’t hold a stock outside key FTSE indexes had to sell. Others dumped it simply because it didn’t fit their mandate. That overhang weighed on the shares for months after listing, and it made early trading choppy.

As Argonaut Securities analyst Matthew Keane put it at the time: “There is appetite for that real good size, mid-tier, just below the BHP’s and Rio’s. For that reason it’ll attract interest.” But he also warned volatility was likely in the first few days as institutions sold simply because they had no choice.

For the investors who could look past the mechanics, the setup was intriguing. The thesis wasn’t that South32 had been spun out because it was perfect. It was that these were assets with real underlying potential that had been managed as second priority for years. The new company now had the one thing they’d never had inside BHP: a management team whose entire job was to make them matter.

The only question was whether South32 could actually execute on that promise.

IV. The Inaugural CEO: Graham Kerr's Vision

Every corporate spinoff needs a leader who can do two jobs at once: build a company from scratch, and squeeze real performance out of the assets it inherits. South32 found that person in Graham Kerr—a long-time BHP Billiton executive with the rare mix of finance discipline and operational scar tissue.

Kerr had most recently been BHP’s acting Chief Financial Officer, which mattered for a newborn miner. South32 didn’t just need someone who could “run mines.” It needed someone who understood why these mines and smelters had been second priority inside the mothership—and how to allocate capital differently now that they finally had their own balance sheet.

He joined BHP in 1994 and cycled through a broad set of commercial and finance roles, including Chief Financial Officer for Stainless Steel Materials, Vice President Finance for Diamonds, and Finance Director for BHP’s Canadian diamonds business. In 2004, he stepped out of BHP to Iluka Resources as General Manager Commercial, then returned in 2006. His path back up ran through BHP’s Diamonds and Specialty Products division, where he was accountable for assets like the Ekati Diamond Mine in Canada and the Richards Bay Minerals joint venture in South Africa, alongside exploration and development work across Angola, Mozambique, and Canada.

In other words: this wasn’t a pure spreadsheet operator. Kerr had spent years in exactly the kind of complex, multi-jurisdiction, mid-tier portfolio that South32 was about to become. He knew what it took to keep operations stable, manage labor and community expectations, and navigate the permitting timelines that can quietly dominate mining economics.

Kerr became South32’s Chief Executive Officer in October 2014, months before the company even existed as a listed entity. When South32 finally rang the bell in May 2015—with listings in Australia, London, and Johannesburg—he was the one turning a carve-out into an actual company: leadership team, operating rhythm, culture, and a strategy that could survive the cycle.

South32 Chair Karen Wood summed up what the board wanted from him: “As inaugural CEO, Graham has been instrumental in establishing South32's values-based culture, building a quality leadership team, and implementing our strategy, underpinned by a disciplined approach to capital allocation and cost management.”

Early Strategy: Discipline Over Deals

Given South32 started life with balance sheet flexibility, many expected the classic spinoff move: go buy something big, quickly, to prove you’re independent and ambitious.

Kerr went the other way.

Instead of swinging at transformative M&A, his early plan was deliberately conservative: optimize first, expand later. The reasoning was straightforward. South32’s assets hadn’t been “bad”—they’d been neglected, capital-starved, and constantly losing the internal budget fight at BHP. Before adding anything new, Kerr wanted to show what this portfolio could do with management attention, refreshed operating plans, and sensible investment. And he was operating in the reality of 2015–2016: commodity prices were weak, which made deals tempting, but also made mistakes expensive.

So the early work was unglamorous by design. Teams were reset. Deferred capital decisions were reopened. Cost structures were pushed harder. The goal wasn’t to manufacture excitement—it was to establish credibility: that South32 could run its inherited businesses better as a standalone than it ever could as a division inside BHP.

For investors, this was the tell. Kerr kept coming back to the same principle: capital allocation matters more than activity. Sometimes the best move is not doing a deal—because the first value to unlock is sitting right in front of you, inside the “orphan” assets everyone else wrote off.

V. Key Inflection Point #1: The Arizona Mining Acquisition (2018)

By 2018, Graham Kerr was ready to make South32’s first true statement move. Three years of tightening operations had started to pay off. The balance sheet had room to breathe. Commodity markets had climbed off the 2015–2016 lows. South32 could finally stop proving it could survive and start proving it could shape its own future.

The opportunity sat in southern Arizona.

Arizona Mining Inc. was a Canadian-listed junior explorer with a standout asset: the Hermosa project in the Patagonia Mountains. South32 wasn’t coming in cold, either. It had taken a minority stake in May 2017 and was already deeply involved in the project’s governance.

We have been a major shareholder in Arizona Mining since May 2017 and an active participant in the Hermosa Project with representation on the operations committee and a nominee on the board of directors. Our deep understanding of this high grade resource and surrounding tenement package, and extensive experience at Cannington, makes us the natural owner of this project.

This wasn’t a splashy, hostile takeover designed to grab headlines. It was the kind of deal Kerr preferred: patient, deliberate, and built on conviction. South32 struck a friendly agreement that offered Arizona Mining shareholders a meaningful premium, and it moved to full control of an asset it believed could anchor the next chapter of the company.

South32 has acquired all of the issued and outstanding common shares of Arizona Mining not already owned by South32 for C$6.20 per common share. With the Arrangement now complete, Arizona Mining's common shares will be de-listed from the Toronto Stock Exchange at the close of trading on August 10, 2018.

South32 Chief Executive Officer, Graham Kerr said: "The acquisition of Arizona Mining adds to our portfolio one of the most exciting base metal projects in the industry. Our deep understanding of the high-grade Hermosa project and surrounding land package, together with our extensive experience at Cannington, positions us well to bring the project to development and deliver significant value to our shareholders."

Why Hermosa Matters

Hermosa wasn’t just “more zinc.” It was South32 buying its way into a different strategic lane.

The project sits in Santa Cruz County, about 50 miles southeast of Tucson and roughly eight miles north of the U.S.–Mexico border. On location alone, it had something many mining projects can’t manufacture: proximity to U.S. infrastructure, U.S. customers, and a U.S. political tailwind around supply-chain security.

Then there’s what’s in the ground. Hermosa is positioned as the only advanced mining project in the United States capable of producing two federally designated critical minerals: zinc and manganese. South32 later received board approval of $2.16 billion in funding to develop the zinc-lead-silver deposit at the site.

In an era when governments started treating minerals like strategy, not just raw materials, that combination mattered. Zinc underpins industrial infrastructure, especially galvanised steel. Manganese is a key battery input, and the U.S. has been acutely aware of how dependent it is on imports for it. Hermosa offered a shot at domestic production of both, alongside silver and lead.

The heart of the complex is the Taylor deposit, described as a carbonate replacement style zinc-lead-silver massive sulphide deposit. The scale is what made it compelling: a Mineral Resource estimate of 153Mt, averaging 3.53% zinc, 3.83% lead and 77 g/t silver.

And Hermosa wasn’t a one-deposit story. Beyond Taylor, the project includes the Clark battery-grade manganese deposit, aimed at supplying the emerging North American EV supply chain. South32’s plan was to integrate Clark with Taylor’s underground mine to capture operating and capital efficiencies, while producing high-purity manganese sulphate monohydrate (HPMSM). In FY23, South32 completed a PFS-S for Clark that outlined the potential for an underground operation integrated with Taylor, plus a separate processing plant.

Put simply: Arizona Mining was South32’s first big bet that it could become more than BHP’s spinoff. Hermosa gave it an asset that fit the world that was coming, not the one it had been carved out of. And for the first time, South32 had a project that didn’t feel inherited—it felt chosen.

VI. Key Inflection Point #2: Sierra Gorda Copper Acquisition (2022)

Hermosa was South32 planting a flag in zinc and manganese. Sierra Gorda was the company making its copper call—loudly.

In late 2021, South32 announced it would buy a 45% stake in Sierra Gorda, one of Chile’s major copper operations. It closed in February 2022: a US$1.4 billion all-cash purchase from Japan’s Sumitomo Metal Mining and Sumitomo Corp.

Graham Kerr didn’t dress up the logic. This was portfolio engineering for the world South32 believed was arriving. “We are actively reshaping our portfolio for a low carbon world and the acquisition of an interest in Sierra Gorda will increase our exposure to the commodities important to that transition,” he said.

Sierra Gorda itself is big, conventional, and built for scale: a large open-pit copper mine in the Antofagasta region of northern Chile, about 1,700 meters above sea level. Construction started in 2011 and it commissioned in 2014. After South32’s entry, the ownership structure was straightforward: South32 held 45%, and the remaining 55% stayed with joint venture partner KGHM Polska Miedz, the Poland-listed global miner.

What wasn’t straightforward was the mine’s reputation.

Under KGHM’s stewardship, Sierra Gorda had attracted criticism for the sheer amount of capital sunk into it—about US$5.2 billion and rising—and for not consistently delivering what investors expected. The reasons were the kinds that haunt large-scale mining: challenging metallurgy, and complications tied to using seawater in processing.

South32’s bet was that those problems were not fatal, just fixable. The asset had what miners crave but can’t manufacture: a massive reserve base—more than a billion tonnes of copper-molybdenum-gold sulphide mineral reserves—and more than 20 years of mine life. Much of the painful, early-stage capital was already behind it. In South32’s framing, the remaining upside would come from operational improvement—exactly the muscle Kerr had been building since the demerger.

Kerr summed up the intended payoff: “Sierra Gorda will immediately contribute to earnings, improve Group operating margins and give South32 long-term exposure to a metal that is increasingly hard to discover, develop and produce. We believe copper will play a key role in the world's decarbonisation and energy transition.”

It also came with infrastructure that would be brutally expensive to replicate: renewable power, a seawater pipeline, and logistics links via freight rail and a national highway to the ports of Antofagasta and Angamos.

In pure corporate terms, it was South32’s second-largest deal since listing—after the Arizona Mining acquisition. In strategic terms, it was the clearest signal yet that South32 wasn’t just optimizing what it inherited. It was buying its way into the commodity that sits at the center of electrification.

Because if the energy transition is a buildout—EVs, renewables, transmission, storage—copper is the wiring. South32 wanted long-duration exposure to that reality, and Sierra Gorda gave it a producing asset with decades of runway.

VII. The Great Portfolio Transformation: Divesting Legacy Assets

South32’s story isn’t just the assets it bought. It’s also the assets it was willing to let go.

While the company was adding exposure to future-facing commodities like copper and zinc, it was quietly running the other half of the playbook: selling businesses that no longer fit where management wanted the company to go. Over the decade after the demerger, South32 systematically unwound parts of the portfolio it was born with—exiting coal and shedding operations that were lower-margin, more capital-hungry, or simply strategically misaligned.

In South32’s own words: it completed the sale of South Africa Energy Coal and the Tasmanian Electro Metallurgical Company in 2021, Illawarra Metallurgical Coal in 2024, and the Metalloys manganese smelter in 2025.

The Exit from Coal

The defining divestment was Illawarra Metallurgical Coal. For a company that started life with meaningful coal exposure, selling Illawarra marked a line in the sand—and South32’s complete exit from Australian coal production.

South32 agreed to sell the Illawarra Metallurgical Coal operation in New South Wales to an entity owned by Golden Energy and Resources (GEAR) and M Resources in a deal worth up to US$1.65 billion. The structure mattered: US$1.05 billion in upfront cash at completion, US$250 million deferred and payable in 2030, plus contingent, price-linked payments of up to US$350 million.

The sale completed on 29 August 2024. South32 reported receiving upfront cash proceeds of US$964 million, net of transaction costs and cash disposed as part of the sale.

Strategically, this wasn’t framed as a pure ESG move—though the emissions angle was clearly part of the backdrop. South32 positioned it as a simplification exercise: reduce capital intensity, lower transition risk, and reallocate attention and capital toward the parts of the portfolio with longer runways. The company noted that Illawarra had represented a meaningful share of group capital expenditure—about 35%—so selling it wasn’t just symbolic. It changed what South32 could fund next.

The Strategic Logic

Step back and you can see the pattern. South32 kept repeating the same idea: make the portfolio simpler, tilt it toward higher-margin, longer-life assets, and create balance sheet flexibility to fund growth options that actually match the “energy transition” direction of travel.

That discipline showed up again in nickel.

South32 agreed to sell its Cerro Matoso ferronickel operation in Colombia in a deal worth up to US$100 million, signing a binding agreement to sell the asset to a subsidiary of CoreX Holding B.V. The decision followed a strategic review prompted by structural changes in the nickel market. And that phrasing—structural changes—was doing a lot of work. With supply growth, particularly out of Indonesia, reshaping global nickel economics, South32 chose not to wait around and hope for a friendlier market.

South32 later confirmed the divestment was successfully completed.

Put together, these exits tell you what kind of miner South32 decided it wanted to be. Since inception, management said it had transformed the portfolio toward minerals and metals critical to the world’s energy transition, pointing to the Illawarra sale, the reduction in transition risk and Scope 3 emissions, and the continued advancement of Hermosa.

The endpoint is a company that looks very different from the one that listed in 2015. Coal was a meaningful contributor in the early days—about 23% of group EBITDA in FY2015. By FY2024, the mix had shifted sharply, leaving South32 with the vast majority of revenue coming from commodities it classified as exposed to the energy transition.

VIII. The Hermosa Bet: Building America's Critical Minerals Future

If there’s one project that captures South32’s shift from “BHP’s leftovers” to a company with a forward-looking identity, it’s Hermosa. About seven years after buying Arizona Mining, South32 made its biggest, clearest commitment yet: it approved $2.16 billion to develop the zinc-lead-silver deposit at its Southern Arizona site—an approval it described as the largest private investment in Southern Arizona’s history, and a step-change for the Santa Cruz County economy.

Hermosa also sits at the intersection of mining and geopolitics. South32 has described it as the only advanced mining project in the United States capable of producing two federally designated critical minerals: zinc and manganese. In 2023, under the Biden administration, Hermosa became the first mining project added to the United States’ FAST-41 permitting program—an attempt to make major infrastructure approvals faster and more predictable. In a business where timelines can quietly kill returns, that kind of permitting tailwind is an advantage you can’t easily replicate.

The scale is what makes the bet real. Hermosa has the potential to become one of the world’s largest zinc producers, with the feasibility work pointing to an initial mine life of roughly 28 years and room for exploration upside beyond that. South32 has also tied the project to local economic outcomes, positioning it as job creation in a community where unemployment is double the state average and roughly a quarter of residents live below the poverty line.

Just as importantly, Hermosa is meant to be a proof point for how South32 wants to build mines going forward. The company has called it its first “next-generation mine”: an underground operation designed around automation and advanced technology, with a relatively compact surface footprint and a plan to use substantially less water than other mines in the region. South32’s pitch is straightforward—higher efficiency, lower operational emissions, and a smaller environmental footprint than the old-school model of mining development.

And the work is no longer theoretical. At Taylor—the deposit expected to anchor production—South32 began sinking the main shaft, commissioned the hoisting system, continued sinking the ventilation shaft, and started construction of the process plant. On the permitting front, the U.S. Forest Service released a Draft Environmental Impact Statement for Hermosa, with the final EIS still expected in the second half of FY26.

Hermosa also isn’t a single-deposit story. South32 has continued progressing the Clark deposit, which could produce battery-grade manganese, and drilling at the Peake deposit has supported the idea of a continuous copper system connecting Peake with Taylor—extra upside if it holds together.

For investors, Hermosa is the cleanest expression of South32’s strategy—and the clearest source of both promise and peril. The promise is enormous: long-life zinc in a stable jurisdiction, plus manganese—and potentially copper—optionality in a world that increasingly treats these materials as strategic. The peril is equally familiar: big mining projects are where schedules slip and budgets blow out. Hermosa’s value will ultimately come down to South32’s ability to execute.

IX. Operational Challenges: Cyclones, Power, and Jurisdictional Risk

Mining has a way of reminding management teams who’s really in charge. You can have the right portfolio, the right balance sheet, and the right strategy—and still get blindsided by weather, infrastructure, or the terms of doing business in a particular country.

For South32, two episodes made that painfully clear: Tropical Cyclone Megan tearing through its Australian manganese operations, and a power-supply standoff in Mozambique that pushed a major aluminium smelter toward shutdown.

The Australia Manganese Crisis

In March 2024, Tropical Cyclone Megan hit Groote Eylandt in Australia’s Northern Territory—home to GEMCO, one of the world’s largest and highest-grade manganese mines.

This wasn’t a routine storm. Megan dumped record rainfall—681 millimetres—and brought some of the strongest wind gusts recorded in two decades. The pits flooded. Critical infrastructure was damaged. Operations were suspended.

South32’s response was basically a rebuild. The company committed $125 million to repair and remediation work at GEMCO, where it owns 60% alongside Anglo American’s 40%. That money went into getting the site safely back online and restoring the logistics chain that makes the mine work in the first place.

The recovery took time, but it worked. By May 2025, GEMCO resumed export sales—an operational milestone that mattered because manganese isn’t useful until it can leave the island. The first shipment began loading from a newly reconstructed wharf, with export sales expected to ramp through the June 2025 quarter and return to normalised rates over FY26.

Mozambique Power Supply

The tougher situation has been Mozal Aluminium in Mozambique, where the issue wasn’t a storm—it was structural.

In late 2025, South32 said Mozal would be placed on care and maintenance by March 2026 after it failed to secure a new electricity supply deal before the current contract expires. Negotiations with the Mozambican government and power suppliers dragged on, but ultimately didn’t produce an affordable agreement that would keep the smelter competitive.

As Graham Kerr put it, “The parties remained deadlocked on an appropriate electricity price,” a dispute made worse by drought conditions that constrained supply from HCB, Mozambique’s flagship hydropower company, Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa.

The accounting followed the operational reality. South32 said it would take a $372 million impairment against its financial 2025 results, reducing Mozal’s carrying value to $68 million.

This was significant for the business: South32 owns 63.7% of Mozal, and the smelter accounted for just over 29% of the group’s aluminium production in fiscal 2025.

The broader lesson is simple and brutal. Aluminium smelting lives and dies on electricity costs. If power isn’t available, or isn’t available at a price that works, even a technically well-run asset can become uneconomic—regardless of how good your operators are.

For investors, these two events show the difference between a shock and a shift. GEMCO’s cyclone damage was severe but temporary: the orebody didn’t go anywhere, and the operation recovered. Mozal is different. It reflects jurisdiction and infrastructure risk that can permanently change the shape of a portfolio—especially when a single external input, like renewable power, is the entire business model.

And it’s why South32’s transformation has always had two tracks: build exposure to the right commodities, yes—but also build a portfolio resilient enough to absorb the moments when mining stops being a spreadsheet and becomes real life.

X. Leadership Transition: The Post-Kerr Era

After more than a decade at the helm, Graham Kerr signaled he would step down—setting up South32’s first CEO handover since it was carved out of BHP.

The company announced that Matthew Daley will join as Deputy Chief Executive Officer on 2 February 2026, with the plan for him to assume the top job when Kerr steps down later in 2026.

It’s hard to overstate how much of South32’s identity is tied to Kerr. He was there before the stock even listed, turning a demerger into a functioning company—building the leadership team, setting the operating rhythm, and then making the bigger calls that followed: reshaping the portfolio, exiting coal, and leaning into metals positioned for the energy transition.

In naming Daley, the board framed the decision as a confident passing of the baton. “Matthew is a highly accomplished executive with extensive operational and leadership experience, including in copper and in the Americas, and the Board is confident he is the right successor for Graham.”

Kerr, for his part, put a personal capstone on the first decade: “It has been an honour to be part of South32 and lead the business through its first ten years. From defining the company's purpose, strategy and values, to transforming its portfolio and setting it up for long term success, I'm proud of all we have achieved since 2015.”

Daley looks like a successor picked for continuity, but not stagnation. He has more than 20 years’ experience across underground and open cut mining, smelting, refining, projects, and commodity trading. He has held leadership roles across multiple commodities and regions, and at the time of the appointment he was Technical and Operations Director at Anglo American plc, and a member of its executive leadership team. He joined Anglo American in 2017 as group head of mining. Before that, he was executive general manager for Glencore PLC’s Canadian copper division.

That resume sends a fairly clear signal about where South32 expects to play. Daley’s depth in copper and base metals fits neatly with the company’s biggest strategic moves of the past few years—Sierra Gorda in Chile, and the long-dated bet at Hermosa in Arizona. To investors, the subtext is simple: the next CEO is being hired for the “future-facing” part of the portfolio, not the legacy part.

South32 also designed the timing to reduce drama. Kerr will remain in charge through a transition period, with the company noting: “Graham will continue to lead the company through the transition period which will give Matthew the opportunity to get to know our people, our stakeholders and our many operations around the world before taking the helm.”

Mining investors tend to treat CEO changes as risk events—and for good reason. Capital allocation, project pacing, and appetite for deals can all shift quickly with a new leader. South32’s long handover and experience-matched successor should limit disruption. But the real tell, once Daley is in the seat, will be whether the discipline Kerr built into the company survives the one thing every new CEO faces: the temptation to put their own stamp on the story.

XI. Analysis: Competitive Position and Industry Dynamics

Porter's Five Forces Assessment

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Mining is one of the most hostile businesses on earth for newcomers. The upfront checks are enormous—Hermosa alone was approved at $2.16 billion—and the money is only the first gate.

After that comes time. Permitting can stretch for years, and Hermosa’s path to FAST-41 status is a reminder that even “supported” projects move slowly. Then there’s the expertise: underground mining, processing, logistics, and the ability to operate safely and reliably across jurisdictions. And finally, the ultimate constraint: quality ore bodies are scarce. You can raise capital; you can hire people. You can’t conjure a world-class deposit out of thin air.

Those barriers get even higher in critical minerals, where policy increasingly favors established, credible operators—especially in the U.S. In that context, Hermosa’s FAST-41 designation functions like a real advantage. It doesn’t guarantee success, but it creates a permitting pathway that would be difficult for a fresh entrant to replicate quickly.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

South32’s biggest supplier inputs are the classic mining list: energy, equipment, labor, explosives, and chemicals. In places where infrastructure is strong, supplier risk can be managed. Sierra Gorda, for example, benefits from established logistics and utilities—renewable power, a seawater pipeline, freight rail, and highway connections to the ports of Antofagasta and Angamos—which helps avoid being boxed in by any single vendor.

But mining has a way of exposing the one input you can’t substitute. Mozal showed how brutally power can dominate outcomes: when an operation depends on external electricity supply and the parties can’t agree on price, the supplier’s leverage can become existential.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE to HIGH

For most of South32’s output, buyers aren’t negotiating on branding or product differentiation—they’re buying into global commodity markets where price is set by supply and demand. That limits pricing power for standard-grade products.

The exception is when the product becomes strategic. If Clark delivers battery-grade manganese, that could command more leverage—not because customers suddenly love paying more, but because supply security starts to matter as much as cost.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW to MODERATE

Most of South32’s core metals don’t have easy substitutes, at least not at scale.

- Zinc is foundational for galvanising steel; alternatives tend to cost more.

- Copper remains the default for electrical conductivity in most real-world applications.

- Manganese is central to steelmaking and increasingly important in batteries.

- Aluminium does face substitution pressure from steel and plastics in certain uses, but the trade-offs aren’t frictionless.

In many ways, the energy transition reduces substitution risk. Electrification and grid buildouts don’t just “use metals”—they lock in demand for the specific properties these metals provide.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is still mining: rivalry is relentless, global, and largely decided by cost position. South32 competes across its commodities with giants like BHP, Rio Tinto, Glencore, and Anglo American, plus a long tail of specialists and regional players. When the product is a commodity, the lowest-cost producer has the most resilience—and everyone else fights for margin in the same cycle-driven arena.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis

South32’s advantages look real in places, but limited in others.

Scale Economies: Present, but not defining. South32 is meaningful in several commodities, yet it doesn’t have the overwhelming scale advantage BHP has in iron ore or Glencore has through its trading machine.

Network Effects: Not a mining thing.

Counter-Positioning: There’s a case here. South32 has pushed hard toward “energy transition” metals and away from coal, which can look like a deliberate contrast to incumbents with heavier legacy exposure. But the edge is narrow: most majors are making similar moves, even if at different speeds.

Switching Costs: Low. Commodity buyers can switch suppliers easily unless constrained by contract terms or qualification requirements.

Branding: Minimal. Mining brands matter to governments, communities, and employees, but they rarely change the price a buyer pays for zinc or copper.

Cornered Resource: This is where South32 looks most distinctive. Hermosa’s positioning as the only advanced U.S. mining project capable of producing zinc and manganese stands out—especially as the U.S. government puts more weight behind domestic critical mineral supply chains. FAST-41 doesn’t create the deposit, but it strengthens the advantage around it.

Process Power: South32 has shown it can improve and stabilize assets it inherited—arguably one of the quiet achievements of the Kerr era. But operational excellence is an advantage competitors can copy, at least in principle, if they have the talent and discipline.

Comparative Analysis

Against the diversified mining peer set, South32 sits in an interesting middle ground:

- BHP: vastly larger, heavily centered on iron ore, and it has exited petroleum.

- Rio Tinto: similarly global, with a stronger aluminium position.

- Glencore: differentiated by trading; its coal exit is less advanced.

- Anglo American: closer in “mid-tier” feel, and at the time has been under takeover pressure.

South32’s cleaner differentiation is what it doesn’t have: legacy petroleum exposure. And what it’s increasingly trying to become: a portfolio geared to electrification and industrial decarbonisation. By FY2024, it said about 83% of revenue came from commodities it classifies as exposed to the energy transition—meaning the company’s story is less “biggest and cheapest” and more “positioned for where demand is going.”

That positioning won’t make South32 immune to cycles. But it does explain why this former spinoff—born from the assets BHP didn’t want to prioritize—has ended up with a strategy that looks, in some ways, more aligned with the next decade of mining than the last.

XII. Key Performance Indicators and Investment Considerations

If you’re following South32 as an investment, the story can feel sprawling: a long-dated U.S. development project, a Chilean copper stake, a reshaped portfolio, and a CEO transition all happening at once. The way to stay grounded is to watch a small set of metrics that tell you whether the strategy is turning into results.

1. Hermosa Development Progress

Hermosa is the centerpiece. The $2.16 billion Taylor investment is the largest capital commitment South32 has ever made, and it will do more than anything else to define the next phase of the company. The practical things to track are straightforward:

- Build progress: shaft sinking and process plant construction

- Permitting: whether the final Environmental Impact Statement stays on track for the second half of FY26

- Spend discipline: capital expenditure versus budget

- Schedule: the timeline to first production, targeted for fiscal 2027

This is the risk-reward fulcrum. If Hermosa stays on time and on budget, the whole “future-facing metals” thesis gets much easier to believe. If it slips meaningfully, the thesis gets stress-tested fast.

2. Copper Equivalent Production Growth

South32’s portfolio shift is ultimately a bet that energy-transition metals will matter more, for longer. One way to see whether that bet is compounding is to watch copper equivalent production, which gives you a single lens across Sierra Gorda, Cannington, and—eventually—Hermosa.

Recent operating performance pointed in the right direction: South32 reported copper production rising 20% in FY2025, with aluminium output up 6%. The details will always move around year to year, but the direction matters: is the portfolio becoming more “electrification-heavy” in reality, not just in narrative?

3. Return on Invested Capital (ROIC)

As South32 deploys more capital into growth projects, ROIC is the scoreboard. It’s the metric that tells you whether capital allocation discipline is surviving the move from optimization into big-project execution.

South32 said its portfolio reshaping helped deliver Underlying EBITDA of US$1.9 billion in FY25 and enabled it to return US$350 million to shareholders during the year. The question going forward is whether that translates into improving returns as Hermosa moves from spending money to producing metal.

Bull Case

The bull case is a clean continuation of the strategy South32 has been executing for the past decade: - The energy transition drives sustained demand for copper, zinc, aluminium, and manganese - Hermosa delivers on its potential as a top-10 global zinc producer, with battery-grade manganese upside - Sierra Gorda continues to improve operationally, lifting copper exposure and earnings contribution - Incoming CEO Matthew Daley leans further into copper growth without abandoning capital discipline - U.S. critical-minerals policy supports Hermosa’s development pathway - Portfolio simplification improves margins and reduces operational complexity

Bear Case

The bear case is less about strategy and more about execution and timing: - Hermosa is a classic megaproject risk: delays and cost overruns are common in mining, and they can erase value quickly - Commodity price volatility works both ways; a down-cycle can compress cash flow just as capital spending peaks - Mozal’s impairment is a reminder that jurisdiction and infrastructure constraints can overwhelm good operations - The energy-transition timeline could disappoint; slower EV adoption would be a headwind for manganese and copper demand - CEO transitions can change capital allocation; value-destructive M&A is a real risk in mining - Environmental and social license issues can disrupt operations across multiple jurisdictions

Regulatory and Accounting Considerations

A few non-negotiables to keep in view: - Hermosa still requires federal approvals, with the final EIS expected in the second half of FY26 - The $372 million Mozal impairment is a concrete example of jurisdiction and power-price risk - The Cerro Matoso sale included an impairment charge of $130 million - Legacy environmental liabilities remain part of the balance sheet reality

South32 also reports both statutory results and “underlying” measures that exclude certain items. To understand performance clearly, investors need to read across both IFRS and underlying numbers—and, more importantly, understand what’s being excluded and why.

Conclusion

Ten years ago, South32 stepped out of BHP as a bundle of “second-tier” operations that many investors never asked to own. The skepticism made sense. These weren’t the crown jewels; they were the businesses that had spent years losing the internal battle for capital and attention to iron ore, copper, and petroleum.

What Graham Kerr and his team proved, over the decade that followed, is that “leftovers” can look very different with a dedicated owner. South32 didn’t win by trying to out-BHP BHP. It won by doing the basics unusually well: disciplined capital allocation, steady operational improvement, and a willingness to reshape the portfolio rather than defend its inheritance.

That reshaping is the headline. South32 exited coal, bought long-duration copper exposure through Sierra Gorda, and turned Hermosa into the centerpiece of its “critical minerals” identity. It’s a decade-long pivot away from being a diversified grab bag and toward being a miner increasingly tied to electrification and industrial decarbonisation.

The numbers in FY2025 reflected that the business had regained its footing: revenue rose 7.1% to US$5.98 billion, and net income swung to US$318 million after a US$638 million loss in FY2024. But the deeper point is what those results represent: a company that’s moved from stabilization to setting up its next growth engine.

Because the transformation still isn’t finished. Hermosa is South32’s most important project—and its biggest source of execution risk. The $2.16 billion Taylor development has to deliver on its promise. The Clark battery-grade manganese deposit still has to prove it can work commercially. And Mozal’s move toward care and maintenance is a reminder that even “good” assets can be undone by the one input that matters most.

For investors, the appeal is clear: exposure to energy-transition metals without legacy petroleum, with coal largely out of the picture, and with growth options in jurisdictions that, relative to much of global mining, look more stable. Whether that deserves a premium valuation comes down to a familiar trio: the pace of the energy transition, commodity price cycles, and South32’s ability to execute—especially in Arizona.

What’s not in dispute is how far the company has travelled from that uncertain May morning in 2015, when forced selling and low expectations set the tone. The “basket of unwanted assets” turned out to be far more valuable than the market assumed—proof that in mining, ownership and capital allocation can matter almost as much as geology.

Now, as Matthew Daley prepares to take the helm, South32 enters its second decade with something it didn’t have at birth: a coherent identity. The next chapter will test whether that identity can compound into durable shareholder value—and whether the big bets in Arizona, Chile, and Australia can keep pace with the world South32 has positioned itself to serve.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music