REA Group: Australia's Digital Property Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

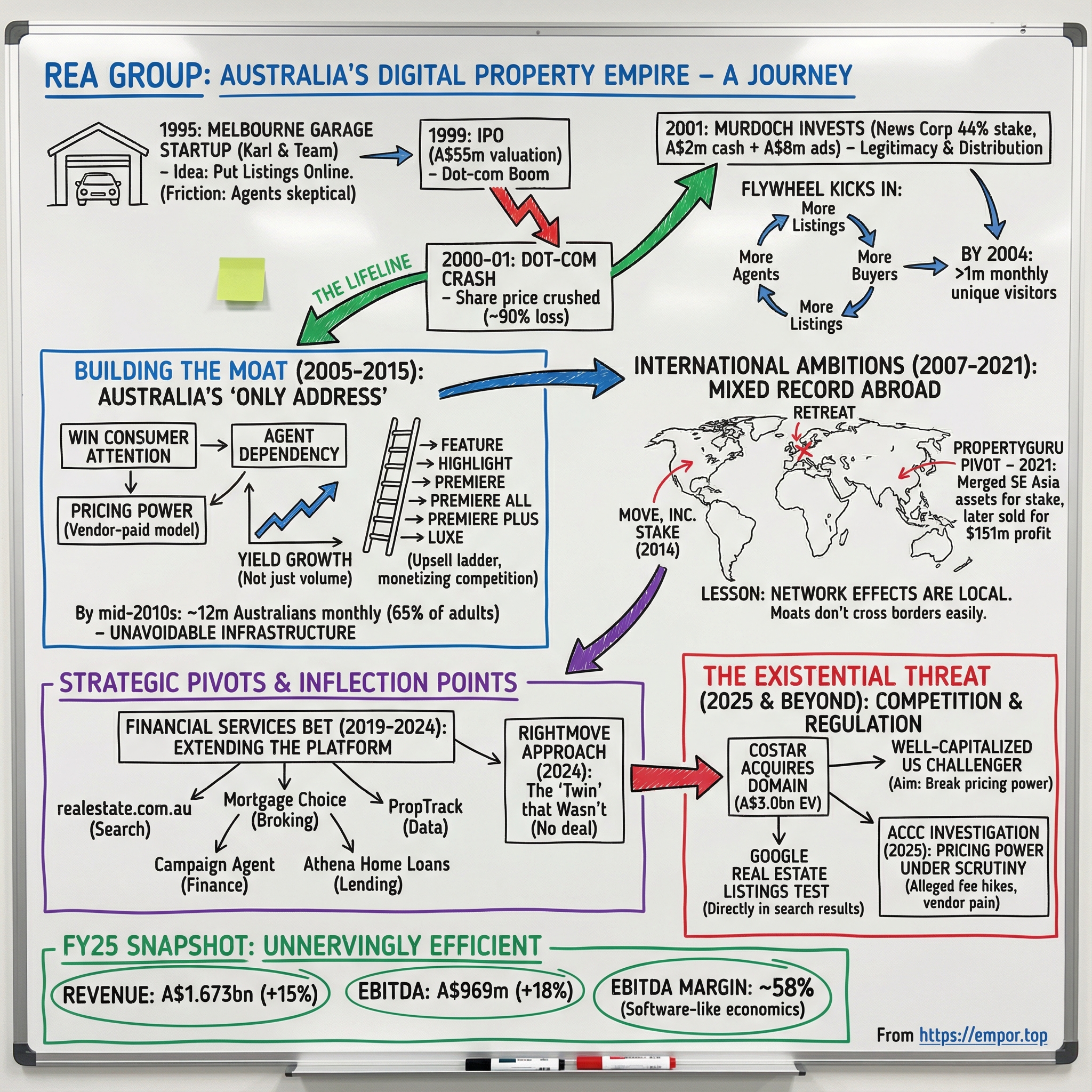

Picture this: Melbourne, 1995. In a modest suburban garage, four entrepreneurs huddle around a computer with a simple, slightly crazy conviction: Australians should be able to search for homes on the internet.

At the time, the internet was barely a commercial thing. Real estate agents lived in the printed classifieds. Buyers did the weekend circuit—open homes, local papers, and long drives spent scanning “For Sale” signs. “Search online” sounded less like a product idea and more like a line from a sci-fi movie.

Now jump forward almost three decades. That garage experiment has become REA Group: a company worth tens of billions of Australian dollars, with a site that draws around twelve million Australians each month—something like two-thirds of the adult population. For agents, it’s not just important. It’s infrastructure. Many simply can’t operate without it.

And the wild part is, REA didn’t glide here on a straight line. It went public right before the dot-com bust, then got absolutely crushed—losing about ninety percent of its value. It survived anyway. It found a lifeline in Rupert Murdoch’s media empire. And from there, it built one of the most dominant, most profitable digital marketplaces anywhere.

This is the story of REA Group. And the arc shows up in the numbers. As of December 2025, REA’s market capitalization sat around A$25.6 billion. When it listed on December 1, 1999, it was valued at about A$55 million. That’s a rise of more than 45,000%—the kind of compounding that sounds fake until you see it on the chart. Put another way: one dollar invested at the IPO would be worth well over four hundred dollars today.

The underlying business has become almost unnervingly efficient. In FY25, REA delivered revenue of A$1.673 billion, EBITDA of A$969 million, and net profit after tax of A$564 million. The EBITDA margin: about 58%. These are software-like economics layered onto one of the most fundamental markets on earth: housing.

In Australia, REA and Domain make up the core of a listings duopoly—but it’s not a balanced one. REA’s flagship, realestate.com.au, is roughly four times the size of Domain in the core business. And in a very Australian twist, the battle lines mirror the media landscape: REA is majority-owned by News Corp, while Domain is majority-owned by Nine Entertainment.

Over this episode, we’ll follow the forces that made that dominance possible—and the tensions it created. Network effects so strong they’ve proven nearly impossible to break. Pricing power so extreme it’s attracted regulators. A global expansion story that exposed the limits of moats crossing borders. And, right now, the biggest competitive threat REA has faced: a well-capitalized American challenger preparing to spend billions to unseat the incumbent.

This is how a Melbourne garage startup became one of the world’s most valuable marketplace businesses—and why the next chapter may be its hardest yet.

II. Founding Story: The Melbourne Garage (1995–1999)

Melbourne, 1995. The internet was still more curiosity than utility. Real estate, meanwhile, was resolutely offline. If you wanted to buy a home, you bought the paper, spread the classifieds across the kitchen table, circled a few hopeful listings, then spent your weekend driving suburb to suburb collecting brochures and squinting through windows.

Karl Sabljak saw all that friction and couldn’t unsee it. Together with his wife Carmel, his brother Steve, and colleague Martin Howell, he set up shop in Karl’s garage and started building a simple idea that sounded borderline ridiculous at the time: put Australian property listings on the internet. The team had firsthand exposure to the early web through MIT, and they believed the internet wasn’t just a new channel. It was a better way to search.

Their insight was straightforward: property search was expensive in time and effort. Buyers were forced to sift through limited information and chase agents for details. Agents had the opposite problem: they had inventory, but no scalable digital way to reach motivated buyers. Put both sides in one place, make it easier for each to find the other, and you don’t just build a website—you start a marketplace. The kind where every new listing attracts more buyers, and every new buyer makes the next agent more willing to list.

In the beginning, there was no grand war chest. It was personal savings, long nights, and whatever they could build with the tools at hand. One early move mattered more than most people realized at the time: securing the realestate.com domain. It was the online equivalent of owning the best storefront on the busiest street—an address people would type before they even knew what they were looking for.

The harder part wasn’t the product. It was the people.

Convincing agents to participate was a grind. Real estate ran on relationships and information advantage, and many agents saw the internet as a threat. Why help put listings online where anyone could browse, compare, and ask better questions? The founders went agent to agent, demo to demo, making the case that the internet could amplify an agent’s reach rather than replace it.

And crucially, the timing was starting to work in their favor. Through the mid-to-late 1990s, internet adoption in Australia accelerated. Dial-up arrived in more homes. Early users discovered that searching online beat flipping through newsprint—every single time. REA planted its flag while habits were still forming.

Then, as the decade closed, dot-com mania arrived. Markets were rewarding “internet” anything, and capital was flowing to companies with audiences, not profits. REA took its shot. On December 1, 1999, the garage startup listed on the Australian Securities Exchange, stepping into the legitimacy—and scrutiny—of the public markets.

It was a milestone. It was also, in hindsight, brutal timing.

Because just as REA rang the bell, the tech bubble was about to burst.

III. The Dot-Com Crash & The Murdoch Lifeline (1999–2005)

The new millennium arrived with champagne toasts and Y2K paranoia. For REA, it arrived with something far worse: the dot-com crash.

Across 2000 and 2001, “internet” stopped being a magic word in markets and started being a punchline. REA’s share price didn’t just wobble—it collapsed. At the bottom, the company had lost roughly ninety percent of its value from the IPO.

This is the moment where most garage-born dot-coms quietly disappear. Capital gets scarce. Customers hesitate. Confidence evaporates. REA’s core idea still made sense—of course people would rather search for homes online than flip through newsprint—but “eventually” is a dangerous word when you’re running out of runway.

Then the lifeline showed up, and it had a Murdoch logo on it.

In 2001, News Corporation bought 44% of REA Group for A$2 million in cash plus A$8 million worth of advertising. The deal valued the whole company at just A$23 million. Not only was that a fraction of where REA had traded at the peak—it was the kind of valuation that screamed, “this is a rescue.”

But this rescue came with something more powerful than money.

First, it kept the lights on at the worst possible moment. The investment landed in the middle of the crash, when other funding sources had effectively vanished.

Second, it gave REA instant legitimacy. Real estate agents didn’t need another pitch from a scrappy startup founder—they needed proof that the internet wasn’t a fad. Murdoch’s backing sent that signal loudly.

Third, and maybe most importantly, it brought distribution. That A$8 million in advertising wasn’t a nice-to-have; it was a growth engine. In the pre-social era, you couldn’t hack your way to nationwide awareness. You bought it. News Corp could put REA in newspapers, on TV, and across its Australian media footprint—turning a niche website into a household name.

News Corp doubled down over time. After a failed attempt to buy the company outright, it lifted its stake to 62% in 2005.

And as the market calmed, the product started to do what marketplaces do when they find fit. By 2004, realestate.com.au was drawing more than one million monthly unique visitors. That mattered because it kicked the flywheel into motion: more listings brought more buyers, more buyers brought more agents, and more agents brought more listings. The loop was finally self-reinforcing.

In hindsight, this is where REA’s trajectory really changes. The crash should have been the end. Instead, it became the crucible that forged the partnership—and the momentum—that would eventually make REA the default “address” for Australian property.

IV. Building the Moat: Becoming Australia's "Only Address" (2005–2015)

By the mid-2000s, REA had done the hard part: it survived the crash and secured a deep-pocketed backer. Now it had to do the harder part: turn momentum into permanence. Plenty of sites can get popular. Very few become unavoidable.

REA’s play was classic marketplace strategy, executed with unusual discipline. Win the consumer first. Own attention so completely that agents, whether they loved you or hated you, couldn’t afford not to show up.

And it worked. Realestate.com.au became Australia’s largest residential listings platform, pulling ahead of Domain and staying there—eventually growing to roughly four times the size of its closest rival in the core business. That gap wasn’t just a vanity metric. It was leverage.

The business model REA honed in this era turned that leverage into money. Rather than charging based on the value of the home, REA charged for what sellers really wanted: visibility. Pay more, get more prominence and features. In other words, REA monetized the competition between sellers for buyer attention.

Once you see it, it’s obvious. Every seller believes their home is special, and every seller wants to be the one you click first.

So REA built an upsell ladder and kept extending it. Over time, it introduced progressively higher tiers—Feature, Highlight, Premiere, Premiere All, Premiere Plus, and eventually Luxe. Each new tier didn’t just add revenue at the top. It siphoned attention from the tiers below, creating a quiet pressure that pushed more vendors to upgrade. Premium listings attracted more eyeballs, which made “premium” feel less like a luxury and more like table stakes.

What made this especially powerful in Australia was the market structure. Australia is largely vendor-paid: the seller typically pays the marketing costs tied to a listing. Agents act as the conduit, but it isn’t their money. That changes the incentives. Agents have less reason to fight price increases, and vendors—staring down the biggest financial transaction of their lives—rarely want to gamble over a few thousand dollars in advertising when the sale price could swing by far more.

This is why REA became a price story more than a volume story. The key metric wasn’t just how many listings were on the site, or even what housing prices were doing. It was yield: how much revenue REA generated per residential buy listing. And year after year, REA found ways to lift it.

Meanwhile, the product expanded and habits deepened. In 2007, REA launched realcommercial.com.au to move into commercial property. In 2010, it shipped its first iOS app and rode the smartphone wave at exactly the right moment. By 2009, realestate.com.au was attracting around five million unique visitors a month—a stunning jump from the early-2000s base and a clear sign that property search behavior was moving online for good.

The revenue mix shifted too. What started as a more traditional subscription-style business increasingly became a “depth products” machine—pay to be seen, pay to stand out, pay to sit at the top of search. Over time, subscription revenue shrank as a share of the whole (from 40% of revenue in FY12 to 6% by FY20), replaced by far more scalable, high-margin listing upgrades.

By the mid-2010s, the flywheel had become self-reinforcing at national scale. Around twelve million Australians—roughly 65% of the adult population—were checking the site each month. At that point, realestate.com.au wasn’t just the biggest destination. It was the destination. And once you reach that level, it becomes brutally simple: if you’re an agent in Australia and you want to win listings and sell homes, you don’t really get to opt out.

V. International Ambitions: The Mixed Record Abroad (2007–2021)

Success at home has a way of rewriting your internal narrative. By the mid-2000s, REA had become the default address for Australian property. The next question was almost inevitable: if this works here, why wouldn’t it work everywhere?

REA’s answer was to buy its way onto the map.

In February 2007, it acquired atHome, a group of real estate websites spanning Luxembourg, France, Germany, and Belgium. That same year, it took a 59% stake in Italy’s casa.it, lifted it to 70% the following year, and then moved to full ownership in 2011. A few months after the atHome deal, REA made its first move into Asia too, announcing on 11 September 2007 that it would acquire Hong Kong’s largest English-language property magazine, SquareFoot.

On paper, the strategy was coherent: acquire established local brands, plug in REA’s product and monetization know-how, and let the marketplace flywheel do its thing.

In practice, Europe was where the limits showed up fast.

REA acquired UK Property Shop in July 2008. But by August 2009, Zoopla had acquired the PropertyFinder Group from REA Group and News International for an undisclosed sum. The broader point landed with a thud: the European push was already turning into a retreat. Just a couple years after expanding, REA was selling assets and stepping back—an early, humbling sign that the advantages it enjoyed in Australia didn’t automatically cross borders.

Because outside Australia, REA wasn’t the inevitable destination. It was the new entrant.

In Australia, REA benefited from early momentum, relatively limited competition, and News Corp’s distribution muscle. In Europe, it ran into entrenched local players and market structures that didn’t reward the same playbook. And critically, the vendor-paid dynamic that made pricing power so potent in Australia often wasn’t there. In many markets, agents controlled the ad budget and could bargain harder, shop around, and play platforms off against each other.

Asia remained on the agenda, but it wasn’t simple either. In 2016, REA Group Asia purchased iProperty Group and Brickz.my in Malaysia, along with Thailand’s thinkofliving and Prakard.com. It built a regional footprint with three offices—Bangkok, Hong Kong, and Kuala Lumpur—and kept investing into the thesis that scale and product could win.

India was the biggest bet. In 2018, REA invested in Elara Technologies, the parent company of Housing.com, Makaan.com, and PropTiger, and then acquired a controlling stake in Elara in 2020. Results were mixed: revenue grew, but core housing revenue stayed flat as competition intensified and pricing came under pressure. It was a clear reminder that even with capital and effort, recreating “Australia-level” dominance is a different game.

North America came via a different route. In 2014, REA bought a 20% stake in Move, Inc., the operator of Realtor.com—its first step into the U.S., and one that leaned on News Corp’s broader relationship with the American portal rather than trying to brute-force a standalone expansion.

By the end of this era, the pattern was hard to ignore. REA’s international portfolio taught the company what its home market had obscured: its moat was real, but it wasn’t universal. In Australia, REA hit escape velocity before serious competition could take hold. In other countries, legitimate competition already existed—not just from other classifieds portals, but from full-stack brokerages, strong local incumbents, and adjacent products competing for the same consumer intent.

The simplest way to say it is this: real estate portals are intensely local businesses that happen to run on software. The network effects that make REA unshakeable in Melbourne don’t automatically mean anything in Mumbai. Every new market demands the same grind all over again—brand, supply, demand, and trust—built against opponents who already understand the local terrain.

VI. Inflection Point #1: The PropertyGuru Pivot (2021)

By 2021, REA’s leadership had to face an uncomfortable truth about Southeast Asia: years of investment across Malaysia and Thailand hadn’t produced anything close to the “default destination” status it enjoyed in Australia. Instead, it was stuck in a grinding fight with PropertyGuru, a Singapore-based rival backed by private equity and built for the region.

So REA changed the game by leaving it.

In May 2021, REA merged its Southeast Asian assets with PropertyGuru. The Malaysian and Thai property sites were transferred into PropertyGuru in exchange for an 18% stake in the combined company and a seat on the board.

This wasn’t a victory lap. It was a strategic pivot—one that looked like partnership language but amounted to a clear admission: REA wasn’t going to win these markets outright. Rather than keep spending to chase a leadership position, it chose to own a slice of the winner.

It was the kind of decision that signals maturity. Instead of continuing a war of attrition from thousands of miles away, REA opted for financial exposure without the operational drag of managing businesses in markets where its Australian moat didn’t apply.

And it worked out.

In December 2024, REA finalised the sale of its 17.2% stake in PropertyGuru, booking a gain of $151 million. A messy competitive battle turned into a profitable exit.

The flow-on effects mattered too. With the divestment, REA paid off all external debt and strengthened its balance sheet. Over the same period, Financial Services revenue rose 13% to $41 million. And in India, REA’s business—driven by Housing.com, the portal and traffic leader, led by Dhruv Agarwala—delivered strong revenue growth, up 46% to A$64 million.

The broader lesson is simple, and it shows up again and again in marketplaces: network effects are brutally local. The moat that protects REA in Australia doesn’t magically extend to Bangkok or Kuala Lumpur. The real win here was discipline—knowing when to stop trying to force dominance, and when to take equity, take learnings, and move on.

Sometimes the best strategic move is the one you don’t keep making.

VII. Inflection Point #2: The Financial Services Bet (2019–2024)

By the late 2010s, REA’s dominance in listings had created an obvious question: why stop at the search?

A home sale isn’t a single event. It’s a chain—discover a property, make an offer, line up a mortgage, sometimes arrange insurance, and coordinate the move. REA already owned the top of that funnel. The strategic leap was to follow the customer down it, and capture more of the transaction—not just the advertising budget.

That push became real in 2021, when REA acquired Mortgage Choice, one of Australia’s best-known mortgage broking franchises. The deal also folded REA’s lesser-known Smartline broker franchise into the Mortgage Choice brand, creating a combined network of more than 940 brokers and 720 franchises across the country.

Once Mortgage Choice sat inside the REA family, the flywheel started to look different. Instead of ending at “contact agent,” the journey could continue: buyers searching on realestate.com.au could be handed off to a broker at the moment financing became urgent. Mortgage Choice brokers began receiving qualified leads from a site with more than ten million visitors each month—turning REA’s massive audience into something closer to a distribution engine for home loans.

This wasn’t a one-off purchase. It fit into a broader build-out of the transaction stack. Alongside Mortgage Choice, REA owned PropTrack, its property data business; Campaign Agent, focused on vendor-paid advertising finance solutions; and Realtair, providing end-to-end technology for the real estate transaction process.

Data was the other pillar. REA’s acquisition of Hometrack Australia, later rebranded as PropTrack, strengthened its ability to package insights for consumers and professionals. Products like realEstimate—automated property valuations—made the platform stickier and more useful, while also improving the quality of the leads flowing into broking.

Then, in October 2024, REA pushed one step further. It bought a 19.9% stake in Athena Home Loans, a digital non-bank lender. The message was hard to miss: REA wasn’t just aiming to refer mortgages anymore. It wanted exposure to the lending economics too—moving from advertising, to brokerage, and now closer to the loan itself.

Financially, the core business was still doing the heavy lifting: in FY25, REA’s revenue grew 15% to A$1.67 billion, and EBITDA rose 18% to A$969 million. Mortgage Choice contributed to that momentum, with strong submissions and settlement growth lifting earnings at the group level.

The Financial Services segment was still small in the context of the whole company—revenue in the segment rose 13% to A$41 million in H1 FY25—but its importance wasn’t just the dollars. It was strategic gravity. Each additional service gave consumers another reason to stay inside the REA ecosystem, tightening the moat around the listings machine that started it all.

VIII. Inflection Point #3: The Rightmove That Wasn't (September 2024)

September 2024 briefly put REA’s international ambitions on full display—because instead of nibbling around the edges overseas, REA floated the idea of buying one of the few businesses in the world that looks like its twin.

That business was Rightmove, the dominant UK property portal. REA announced it was considering a cash-and-share takeover, and the market reacted instantly. Rightmove’s shares jumped about 25%, pushing its market value up to roughly £5.4 billion. The message was clear: investors believed this wasn’t idle chatter.

On paper, the logic was easy to understand. Rightmove’s position in the UK is broadly analogous to REA’s position in Australia: the category-defining destination with powerful network effects and the kind of pricing power competitors struggle to dent. Put them together and you’d have a single property-portal heavyweight spanning multiple major English-speaking markets. Analysts also pointed out that, beyond listings, a deal like this could have offered REA a bigger platform for adjacent businesses like mortgages and commercial property.

REA leaned into that framing, pointing to the “clear similarities” between the two companies and calling Rightmove a “transformational opportunity.” Under UK takeover rules, REA had until the end of September to either make a formal offer or walk away.

Rightmove later confirmed it had received a proposal valued at 698 pence per share—and that it had rejected it. The board said the approach fundamentally undervalued the business and its future prospects, and described it as opportunistic.

That response exposed the core problem with trying to buy a portal at the peak of its powers. Rightmove wasn’t distressed. It wasn’t subscale. It didn’t need a partner. And if the board wasn’t interested, the only path left was escalation—either a much higher price or a hostile attempt. REA did neither. It ultimately stepped back without making a formal offer.

The episode also highlighted the dynamic between REA and its majority owner, News Corp. A deal of this size and symbolism would have required News Corp’s support and potentially significant capital. The fact REA even made the approach suggests News Corp could see value in consolidating global property portal assets—an interesting clue about how seriously the Murdoch empire views digital real estate as a long-term pillar.

It also stood in sharp contrast to REA’s more recent international track record. REA had exited parts of Europe—selling its European online listings business to Oakley Capital Private Equity in 2016—and it had just taken chips off the table in Southeast Asia via its PropertyGuru stake, sold to Swedish investor EQT.

So the Rightmove moment reads less like a random swing and more like an evolution in strategy. After learning how hard it is to export Australia’s moat by force, REA flirted with the opposite approach: don’t build the fortress abroad—buy the one that’s already standing.

IX. The Existential Threat: Domain, CoStar & The Coming War (2025)

For two decades, REA’s position looked untouchable. Domain Holdings—the clear number two, backed by Nine Entertainment—was big enough to make the market look competitive, but not strong enough to change the outcome. Agents listed on Domain, sure. But the industry ran on realestate.com.au.

That comfortable equilibrium snapped in 2025.

In August 2025, CoStar Group announced it had completed its acquisition of Domain Holdings Australia Limited, valuing Domain at an implied enterprise value of A$3.0 billion. Overnight, the “distant second” stopped being a local media asset and became the Australian beachhead for a deep-pocketed American operator with a track record of spending its way into relevance.

Domain already reached around 7 million Australians each month and had built a well-known, trusted brand. What it didn’t have—until now—was the ability to invest at a scale that could genuinely pressure an incumbent like REA. CoStar brings that, along with product capabilities, marketing firepower, and the willingness to run a long, expensive campaign to shift consumer habit.

CoStar CEO Andy Florance didn’t bother with subtlety. “Agents and vendors are being squeezed by legacy models that raise prices without raising value,” he said. “That ends here.” He positioned CoStar’s entry as “pro-agent, pro-buyer and pro-vendor,” promising better tools, more traffic, and a better user experience—at lower cost. And he pointed to what he sees as the proof point: CoStar’s push in the U.S., where it transformed Homes.com into an “agent-friendly” platform and aimed it directly at entrenched incumbents.

This wasn’t an analyst note. It was a declaration.

And CoStar had already been signaling intent before the finish line. In February 2025, it bought roughly 17% of Domain’s ordinary shares at A$4.20 per share, for about A$452 million—planting a flag before the full acquisition was even done.

Then, as if one new challenger wasn’t enough, a second threat appeared from a completely different direction: Google.

This week, Google began quietly testing real estate listings directly inside its own product experience. U.S. tech journalists reported that Google was showing property details, a “request a tour” button, and links to contact agents—exactly the high-intent actions that portals are built to capture. The market reacted fast. REA shares dropped 5.47% within a few hours.

It’s still early. Citi analysts argued that Google’s “new homes for sale” test is unlikely to materially affect REA, despite fresh jitters in the sector after Zillow’s recent sell-off. But the significance isn’t the feature set in week one—it’s the category of competitor. CoStar is a well-funded portal operator trying to out-execute REA. Google is the default starting point for consumer intent across the internet, and it can change distribution rules without asking permission.

Layer on top the accelerating moves from AI platforms, and you get a picture of an industry entering a new phase. With OpenAI collaborating with market-leading portals like REA Group in Australia and Scout24 in Germany, it’s increasingly clear the AI giants are pushing deeper into real estate discovery. If the next portal war is fought over where consumers begin their search—and who owns the interface—AI may be the battlefield.

REA management, for its part, has tried to project calm. It has reiterated that its dominant share of buyer leads and audience, plus ongoing product investment, should protect pricing power and retention. And there is precedent in mature markets: once a portal becomes the habit, dislodging it is extraordinarily difficult, and challengers often struggle to translate spend into real switching.

But there’s a catch in that precedent: it mostly comes from markets where the challenger didn’t have CoStar’s resources.

REA has faced competitors before. It has never faced one with a roughly US$27 billion market cap, global operational experience, and an openly stated mission to break the incumbent’s pricing power.

X. The Regulatory Reckoning: ACCC Investigation (2025)

REA Group’s extraordinary pricing power—the very thing that makes it such a remarkable business—finally drew the attention of regulators. In 2025, REA came under formal investigation by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) over allegations of market power abuse and excessive pricing tied to its subscriptions and property listings. The ACCC issued REA a formal Section 155 notice, compelling the company to provide detailed information about its subscription offerings.

And the complaints aren’t subtle. Listing fees on realestate.com.au vary by location and property value, but agents say the direction of travel has been relentlessly up. Some claim prices have risen more than 5,000% over the past 15 years, with premium listings in Sydney reportedly topping A$4,000. In some suburbs, listing a home on realestate.com.au can cost as much as A$5,000—nearly 50 times the roughly A$75 agents said it cost back in 2009.

Real Estate Institute of NSW CEO Tim McKibbin said his organization first approached the ACCC 18 months earlier with evidence of dramatic fee escalation. “Agents report annual REA price increases well above the CPI, often in the realm of 10 per cent, and in many instances, even more,” he said. The anger only sharpened when an agent claimed the fees charged by REA rose 30% in a single year.

The ACCC probe zeroed in on subscription increases too. Some agents reportedly faced monthly costs rising by as much as 110%, with top-tier listings cited at A$399 per month, effective from July 2025. In Casey, local agents told reporters their advertising costs on realestate.com.au had surged over the years, with one calling the pricing “ridiculous and out of control.”

What makes this politically combustible is the same structure that makes REA financially powerful: Australia’s vendor-paid model. When marketing costs are pushed through to sellers, it becomes easier for price increases to stick. But that also means the pain shows up in the most public, emotionally charged place possible—the cost of selling a home. Critics argued that in some cases listing fees had grown so large they could swallow a huge share of an agent’s commission, and that sellers were effectively paying thousands of dollars just to access the dominant platform.

Federal MP Dr. Sophie Scamps framed it in consumer terms: “There are already too many barriers to people selling and downsizing their homes, so it’s disturbing to hear Australians are, yet again, apparently paying inflated prices to have their house listed on real estate marketing platforms.”

Former ACCC chair Allan Fels observed that REA wasn’t investigated during his tenure, but said the company had since become “immensely powerful.” The investigation followed years of complaints that REA, as Australia’s leading property portal, could leverage its position in ways that harmed agents—and potentially consumers too.

The ACCC hasn’t set a public timeline for when the investigation will conclude. REA said it was cooperating fully and that it “remains committed to providing value and flexibility to its customers.”

It’s the most ironic consequence of REA’s success: the ability to raise prices year after year without losing volume is a dream for investors—until it starts to look like a public policy problem.

XI. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

REA Group’s three-decade run—from a Melbourne garage to a market leader worth around A$25 billion—reads like a guidebook for how to build a moat that’s both durable and wildly profitable. And the lessons aren’t just for real estate portals.

The First Mover + Media Muscle Formula

REA’s timing was excellent. Launching in 1995 put it early enough to shape consumer habits before “online property search” was even a category. But being first doesn’t guarantee you survive long enough to matter. When the dot-com crash hit, it wasn’t just the business model that needed proving—it was the company’s ability to stay alive.

That’s where News Corp changed everything. The 2001 deal didn’t only bring cash. It brought credibility and distribution, including A$8 million of print and TV advertising that helped turn a useful website into a household name at a moment when “brand” was the scarcest resource in the market.

The takeaway: in two-sided marketplaces, the race to critical mass often decides the winner. And anything that accelerates that race—capital, media reach, strategic partnerships—doesn’t just help in the moment. It compounds.

Network Effects in Classifieds

REA’s real advantage is simple to describe and brutal to compete with: network effects. More listings attract more buyers. More buyers attract more agents. More agents bring more listings. Once that loop becomes the default habit for a country, breaking it is extraordinarily difficult—arguably unprecedented in developed-market property portals.

And the reason isn’t just economics. It’s psychology. For most people, their home is their biggest asset by far. Saving on a listing fee feels trivial next to the possibility—real or imagined—that fewer eyeballs means a lower sale price. When the stakes are that high, sellers optimize for maximum exposure, not minimum cost.

REA itself distilled that advantage into a recent campaign line: “Millions More Buyers.” That’s the whole moat, in three words.

Vendor-Paid Models Create Pricing Power

Australia’s vendor-paid structure supercharges REA’s pricing power. Because sellers ultimately fund the marketing spend, agents often act as conduits rather than the truly price-sensitive customer. That dynamic makes it easier for REA to raise prices year after year without seeing the kind of volume impact you’d expect in other industries.

But there’s a trade-off. Vendor-paid markets aren’t universal. In many countries, agents control the ad budget directly, and that creates a more natural ceiling on pricing. Part of REA’s uneven international record is simply that one of its most powerful structural tailwinds at home doesn’t show up overseas.

Geographic Moats Don’t Travel

REA learned the hard way that network effects are local. Being dominant in Australia didn’t give it an automatic edge in Italy, Malaysia, or elsewhere. It had to build supply, demand, and trust from scratch—while competing with incumbents who already owned consumer habits and knew the market’s quirks.

For investors, the implication is straightforward: be cautious when a dominant local marketplace pitches international expansion as a repeatable play. The moat that looks unassailable at home can be close to irrelevant abroad.

Platform Extension Strategy

Finally, REA’s move into financial services—Mortgage Choice, PropTrack, Athena Home Loans—shows the platform extension playbook in action. Once you own the search moment, the next step is to follow the customer into adjacent transactions: financing, data, agent tools, and anything else that keeps the relationship inside your ecosystem.

The risk is focus. Extensions can be powerful, but they can also pull attention away from the core fortress. And in a world where CoStar is gearing up to attack that fortress directly, REA has to do both: expand the platform, while relentlessly defending the engine that made everything possible.

XII. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

To understand why REA has been so hard to dislodge—and why the pressure is starting to rise—you can run it through two classic strategy lenses: Porter’s Five Forces and Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers.

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW (but rising)

Building a competing property portal isn’t just a matter of writing code and buying ads. The real barrier is psychological and behavioral: getting buyers and agents to change a habit. In Australia, REA and Domain form a duopoly in residential listings, and REA is the clear heavyweight.

A useful comparison is Sweden’s Hemnet. Hemnet draws more than 40 million visits a month and generates 16 times more clicks per listing than its nearest competitor. That’s what entrenched network effects look like: more listings pull in more buyers, which attracts more agents, which brings even more listings. Once that loop locks in, breaking it is brutally difficult.

That said, there’s a new category of potential entrant that doesn’t play by the usual rules. Google doesn’t need to “become a portal” first. It can capture intent before a user ever reaches one—and it has essentially unlimited distribution and capital.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Real Estate Agents): LOW

REA doesn’t price listings based on the value of the home. It prices based on the visibility and features vendors want. In other words, it sells prominence, not space. That’s why REA can perform well regardless of what housing prices are doing: if listings keep flowing, the machine keeps turning.

Agents may grumble, but their leverage is limited. They depend on REA to reach buyers at scale, and REA continues to carry the most listings even while charging the highest prices—and regularly raising them. Australia’s vendor-paid model lowers resistance further, because agents typically pass marketing costs through to the seller.

And there’s a practical constraint too: to operate effectively in Australia, most agents have very few viable options beyond subscribing to REA’s tools and being present on the platform buyers already use.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Property Seekers): LOW

For consumers, realestate.com.au is free. That alone removes direct pricing pressure. And the audience scale reinforces the habit: the site averaged about 11.9 million monthly visitors. When roughly 65% of Australian adults are showing up each month, buyers go where the listings are—and sellers and agents follow.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE (rising)

The substitute risk isn’t Facebook groups or “for sale” signs. It’s the possibility that discovery moves upstream.

Google is the clearest example. This week, it began quietly testing real estate listings inside its own experience, and the market reaction was immediate—shares in REA and CoStar moved sharply. The reason is simple: if Google owns the first click, portals risk getting pushed from destination to downstream commodity.

Direct agent-to-consumer models remain limited, and social media has minimal impact. But AI-driven interfaces add another wildcard: a new way for consumers to search, shortlist, and transact without ever developing loyalty to a portal.

Competitive Rivalry: LOW-MODERATE (rising)

REA’s core business—realestate.com.au—is the largest residential listings platform in Australia, at around four times the scale of number two, domain.com.au. For years, that gap mattered because it kept Domain in “credible alternative” territory without truly threatening REA’s pricing power.

CoStar’s completed acquisition of Domain changes the tone. Domain is no longer just a local challenger; it now has a global parent that’s promising tech leadership, a pro-agent stance, and the willingness to invest heavily. Rivalry was contained for a long time. In 2025, it started to look like a fight.

Hamilton's 7 Powers

Network Effects: VERY STRONG

This is the core power. Buyers attract sellers, sellers attract agents, agents bring listings, listings attract buyers. With REA’s scale, the flywheel spins faster—and gets harder to interrupt. As REA put it: “More people turned to our platform in the half than ever before, with 5.1 million more Australians visiting realestate.com.au every month on average compared to our nearest competitor.”

Scale Economies: STRONG

Marketplaces have a beautiful cost structure once they reach dominance: the platform costs don’t rise nearly as fast as revenue. Incremental dollars fall disproportionately to profit. REA’s FY25 operating EBITDA margin of about 58% doesn’t happen without that scale advantage.

Switching Costs: MODERATE-HIGH

Switching costs aren’t about software contracts; they’re about business risk. Agents can’t credibly tell a seller, “We’ll skip the biggest portal,” because the seller’s fear is simple: fewer eyeballs means a lower sale price. And once agents have built their process around REA’s tools, presence, and lead flow, walking away gets even harder.

This is why investors tend to focus less on listing volumes and more on yield—how much REA makes per residential buy listing.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE

For years, newspapers couldn’t respond effectively because doing so meant accelerating their own decline. Print classifieds funded the old model; moving online cannibalized it. By the time traditional media fully embraced digital property listings, REA had already built the consumer habit and the agent dependency.

Cornered Resource: STRONG

REA’s assets aren’t just technical—they’re positional. The company was formerly known as realestate.com.au Ltd. and changed its name to REA Group Limited in December 2008, but the realestate.com.au domain remains the ultimate cornered resource: the most intuitive address in the category. Combine that with decades of brand building, and you get something close to unreplicable.

Process Power: MODERATE

REA has consistently improved the product: more personalization, better data, and increasing use of AI-driven tools and analytics. None of that is exclusive to REA, but execution matters—and REA has historically out-executed competitors in turning product into engagement and engagement into monetization.

Branding: VERY STRONG

In Australia, realestate.com.au isn’t just a well-known site. It’s the default. As REA has said: “Australians continually turn to realestate.com.au as the most trusted property platform, with more listings than anywhere else.” That trust—especially in a high-stakes category like housing—translates into habit, and habit is the ultimate defense.

XIII. Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bull Case

REA Group headed into 2026 looking like the kind of business investors dream about: essential, dominant, and wildly profitable. FY25 was a strong reminder of what happens when marketplace network effects meet software economics. Revenue rose 15% to A$1.673 billion, EBITDA climbed 18% to A$969 million, and net profit after tax increased 23% to A$564 million. An operating EBITDA margin of 58% is the punchline: this is a classifieds business with margins that look like enterprise software.

And the core moat still looked intact. REA said it attracted about 127 million average monthly visits, more than four times the monthly visits of its nearest competitor in the second half on average. It also reported 3.8 million unique properties being tracked by their owners on realestate.com.au, up 37% year over year. Those are the kinds of engagement metrics that reinforce the flywheel: more consumers watching, more agents listing, more vendors upgrading for prominence.

The adjacency story is also getting real. Commercial and Developer revenue grew 10% to A$110 million. Financial Services revenue rose 13% to A$41 million. Mortgage Choice and the stake in Athena Home Loans fit the same strategic logic: REA already owns the moment people start dreaming about a home. If it can also help finance that home, it captures more value per customer without needing to win an entirely new audience.

Finally, there’s the “history rhymes” argument. REA management has tried to lower the temperature around CoStar’s arrival, pointing to its dominant share of buyer leads, audience scale, and ongoing product investment as protections for pricing power and retention. In other mature portal markets, challengers have often struggled to turn aggressive spending into durable switching. If that pattern holds, CoStar’s campaign may end up loud, expensive, and less impactful than feared.

The Bear Case

The first problem is that CoStar doesn’t sound like a challenger looking for a respectable second place. It sounds like a company that has come to flip the table.

“Agents and vendors are being squeezed by legacy models that raise prices without raising value,” CoStar CEO Andy Florance said. “CoStar Group’s entry into Australia is about creating a sustainable, pro-agent marketplace—one that invests in better content, better tools, more traffic, and a superior user experience, while lowering costs. We dismantled market dominance in the U.S. by transforming Homes.com into a true agent-friendly platform, and we are ready to apply that same proven playbook in Australia.”

If CoStar is willing to spend heavily for years, the risk to REA isn’t that it loses overnight. It’s that the two things REA relies on most—traffic leadership and yield growth—start to bend in the wrong direction. Even modest share shifts can matter when your business is priced like a perpetual winner.

The second problem is that REA’s greatest strength—pricing power—has become a vulnerability in the public square. The ACCC investigation creates real regulatory risk. Agents have alleged listing fee hikes on the order of 5,000% over 15 years. Even if the outcome isn’t a dramatic penalty, sustained scrutiny can change behavior. A business built on steadily lifting yield doesn’t like being told, even informally, to keep increases “reasonable.”

Then there’s Google, which changes the category of competition entirely. Google has begun testing real estate listings inside search results, linking users to full property pages with agent contact details and the ability to organise tours. If Google owns the first click at scale, portals risk being pushed downstream—less destination, more supplier.

As Goldman Sachs analyst Michael Ng said in response to similar moves affecting Zillow: “While we don’t expect a direct near-term impact on Zillow’s business... we view this development as a long-term risk for real estate portals like Zillow.” The same logic applies to REA.

Finally, there’s leadership risk at exactly the wrong moment. REA also announced that Wilson would retire imminently, with plans to leave during the year after a decade at the company and six years as CEO. Even great businesses can stumble during transitions—especially when a well-funded competitor is gearing up for a fight and regulators are circling.

Key Performance Indicators

For investors tracking REA Group, two metrics matter most:

-

Residential Buy Yield: This is the cleanest way to see pricing power and the shift toward premium depth products. Yield matters more than listing volumes. It’s calculated as total revenue from Residential Buy Listings divided by the total number of Residential Buy Listings. If yield keeps growing comfortably above inflation, the moat is holding. If it starts to compress, competitive pressure is likely landing.

-

Audience Lead Over Competitors: REA’s traffic gap versus Domain (now owned by CoStar) is the visible scoreboard for network effects. REA said: “We further strengthened our audience position in FY25, increasing our lead over the nearest competitor by 17% on the prior year.” If that lead narrows, CoStar’s spending is working.

Watch yield resilience through the CoStar offensive, and watch whether the audience gap holds. Those two lines will tell you if REA remains the unavoidable infrastructure of Australian property—or if, for the first time in decades, the flywheel starts to slip.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music