QBE Insurance Group: The Relentless Acquirer from the Queensland Frontier

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

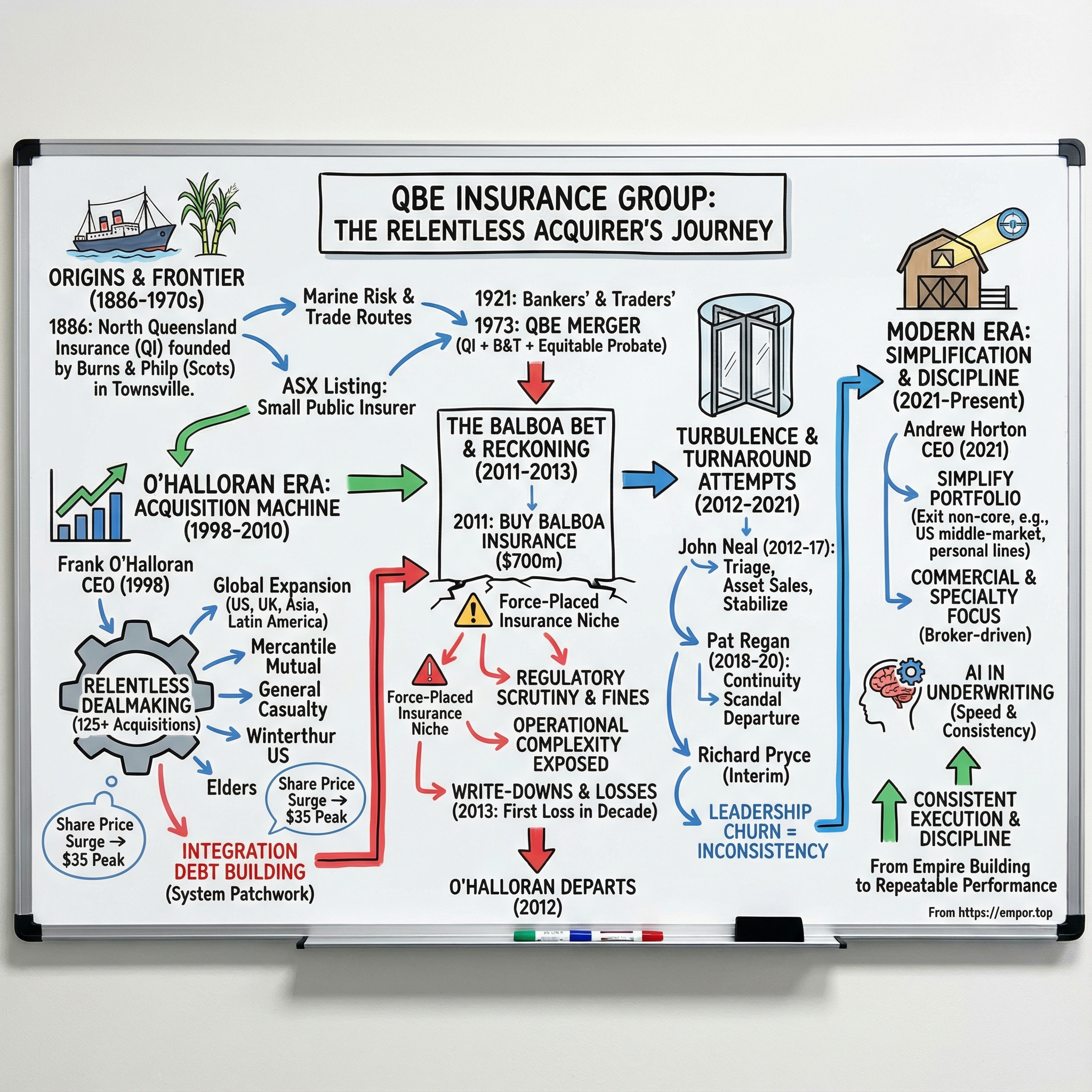

Picture a boardroom high above Sydney in early 2011. QBE Insurance Group—Australia’s biggest general insurer—announces its most ambitious deal yet: the purchase of Balboa Insurance from Bank of America. The market loves it. QBE’s shares jump nearly 8% in a day. Frank O’Halloran, the CEO who turned a once-provincial insurer into a global player through relentless dealmaking, looks untouchable.

Two years later, he’s gone. And QBE is deep in the hangover—writing down value, nursing painful surprises in its portfolio, and posting its first annual loss in more than a decade.

Zoom out and the scale is striking. QBE Insurance Group Limited is an Australian multinational general insurance and reinsurance company headquartered in Sydney. In the year ended December 31, 2024, it reported gross written premiums of $22.4 billion, up 3% from 2023. Roughly a quarter of its premiums come from Australia and New Zealand, and more than 30% from North America. It operates across 26 countries and, as of 2024, employs about 13,275 people.

The question at the heart of this story sounds simple: how did a small marine insurer—founded by two Scottish immigrants in remote Queensland in 1886—grow into one of the world’s top 20 insurers… and then nearly wreck itself through acquisition addiction, before clawing its way back?

Because QBE wasn’t built by one breakthrough product or one perfect market cycle. It was built by accumulation—hundreds of acquisitions over decades. O’Halloran alone was directly responsible for more than 125 deals across 27 years. The strategy created a sprawling global empire at incredible speed. It also left behind a mess of systems, cultures, and risks that didn’t automatically fit together—and that would eventually demand a reckoning.

So this is a story about the power and peril of growth by acquisition. It’s about the weird, underappreciated economics of insurance—where catastrophe risk, reserving, and investment returns can make geniuses look foolish, and vice versa. And it’s about integration: the hard, unglamorous work of turning a patchwork of bought businesses into one coherent company. QBE’s journey is a case study in how to scale, how to stumble, and how—if you’re disciplined enough—how to come back.

II. The Frontier Origins: Scottish Immigrants, Ships & Sugar

The year is 1886. Queensland is Australia’s wild north: sugar plantations carved out of subtropical scrub, small-town merchants supplying scattered settlements, and coastal shipping routes that thread through reefs and cyclone-prone waters. In a place where a single storm could wipe out a season’s profits, risk wasn’t an abstraction. It was daily life.

Into that landscape stepped two young Scotsmen who weren’t just building a business—they were building infrastructure for a frontier economy.

QBE’s story begins in October 1886, when James Burns and Robert Philp—already partners in a shipping venture—founded The North Queensland Insurance Company Limited, known simply as QI. Burns had arrived in Townsville in 1872 and built a retail and wholesale operation. Two years later he hired Philp, another Scot, and the partnership stuck. In 1883, they formalized the broader enterprise as Burns Philp & Company Ltd., capitalized at £150,000.

Then came the move that was both obvious and quietly brilliant: if you own the ships, why pay someone else to insure them? Burns and Philp understood marine risk from the inside. By creating an insurer, they could cover their own fleet and also sell policies to other shippers moving goods up and down the coast. It was self-insurance, yes—but also a distribution play. They already had the relationships, the routes, and the commercial touchpoints. The product was a natural extension of the network.

QI’s early focus was marine insurance, built for the practical realities of maritime trade. And it didn’t stay local for long. By 1890—just four years in—QI had more than 35 agencies, not only across Queensland but in places that mattered to global commerce: London, Hong Kong, and Singapore. For a company born in a tropical outpost, this was a statement. They weren’t thinking like provincial merchants. They were thinking like empire traders.

Over the next two decades, that footprint widened further, with operations established across Asia, including Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, India, China, Sri Lanka, and Burma. This wasn’t accidental international expansion; it followed the trade routes and relationships of Burns Philp & Company. The parent’s merchant connections opened doors. The insurance arm followed, creating a tight, mutually reinforcing ecosystem: the trading business moved goods and built relationships, and the insurer wrapped those relationships in protection.

The context makes the ambition even more impressive. Australia was still a collection of colonies—Federation wouldn’t arrive until 1901—and communication with London could take weeks. Yet Burns and Philp built an internationally networked insurance operation from Townsville, thousands of miles from global finance. That combination of geography and reach—frontier grit paired with global intent—shows up again and again in QBE’s DNA.

And that Burns Philp connection? It would remain QBE’s umbilical cord for more than a century—fueling expansion, supplying capital, and shaping the company’s worldview. It was a powerful advantage. It was also a dependency. One day, QBE would need to stand on its own.

III. Building the Insurance Dynasty: Early Consolidation (1900s-1970s)

As Queensland Insurance matured, Burns and Philp did what they’d done from the start: they looked at the map of risk around their trading empire and asked where else the business could stretch. By the early 1920s, Queensland Insurance was a major force in Australian commercial insurance. The next move wasn’t a single expansion office or a new product line. It was a second insurer.

On March 3, 1921, they founded the Bankers’ and Traders’ Insurance Company, or B&T, with Queensland Insurance as its largest shareholder. The prospectus spelled out the mandate in plain language: fire, marine, accident, and pretty much every type of insurance except life.

The name wasn’t just branding. “Bankers” came via the Royal Bank of Canada-owned Montreal Trust Company, which also held a stake. That Canadian connection mattered. It gave the Burns-Philp orbit credibility and relationships outside Australia, and it helped explain why a Queensland-based insurer was already thinking in North Atlantic terms.

Structurally, the two-company setup was handy. It let the group bring influential local directors into the fold when needed, and it provided flexibility to shift business and arrange financing between Queensland Insurance and B&T. It was an early version of a playbook QBE would later perfect: use corporate structure as a tool, not just a legal formality.

Then the founders were gone. In 1923, after the deaths of James Burns and Robert Philp, Burns’ son—also James—took the reins of both Queensland Insurance and B&T. He didn’t just preserve what they’d built; he extended it. Through the interwar years, the business pushed deeper into Asia and established new outposts in New York, Montreal, and Cairo—signals that this was no longer just an Australian insurer with a few overseas agencies. It was becoming a network.

A major piece clicked into place in 1959. Queensland Insurance and B&T each bought 40% of The Equitable Probate and General Insurance Company, with Burns Philp taking the remaining 20%. It wasn’t just another investment; it was a setup for consolidation—the kind of tidy corporate logic that looks obvious in hindsight and takes decades to actually pull off.

That pull-off arrived in 1973. Queensland Insurance and B&T merged and adopted a new name built from their component parts: QBE. Q for Queensland Insurance, B for Bankers’ and Traders’, and E for Equitable Probate and General.

And with that merger came a shift in identity. QBE debuted on the Australian Securities Exchange as the year’s largest listing, with a market capitalization of $41.5 million. It was meaningful money, but not global power. More importantly, the listing turned QBE from a long-running family-linked enterprise into something else: a publicly traded platform that could raise capital, issue shares, and pursue growth at a new scale.

To understand why the next era would be so extreme—why QBE would become one of the most relentless acquirers in insurance—you have to understand the industry’s strange economics.

Insurance runs on an inverted timeline. You get paid first. Premiums come in today, while claims might not be paid for months, years, sometimes longer. That gap creates float: a pool of cash the insurer holds between collecting premiums and paying claims. Invest float well, and you can make real money before you’ve paid out a dime.

Then comes the discipline: underwriting. The simplest scoreboard is the combined ratio—claims plus expenses divided by premiums. Below 100% means you made an underwriting profit; above 100% means you lost money on the insurance itself and are hoping investments bail you out.

The catch is that insurance punishes complacency. One catastrophic year can erase years of steady gains. That’s why diversification—by geography, by product, by risk exposure—isn’t just a nice-to-have. It’s survival. And those dynamics would drive nearly every major choice QBE made from here on out.

IV. The Frank O'Halloran Era Begins: The Architect of Acquisition

Frank O’Halloran arrived at QBE in June 1976 as Group Financial Controller. He was 30 years old, and he was walking into a company that was still very much in its “small public insurer” phase—writing roughly $85 million in premiums, worth only about $6 million in market value, and coming off an operating loss the year before. He knew QBE already: he’d trained as a chartered accountant at Coopers & Lybrand, and QBE had been one of his clients.

That detail matters, because O’Halloran didn’t come in as a swashbuckling operator. He came in as a numbers-and-systems person. But QBE was the kind of business where the numbers were the business. If you truly understood reserving, claims patterns, reinsurance, and investment risk—and you were willing to act on that understanding—you could outmaneuver much larger competitors.

In 1981, the board appointed John Cloney as CEO. Cloney was the insurance technician; O’Halloran was the finance mind. Together, they formed the kind of partnership that shows up again and again in great insurance companies: underwriting discipline paired with capital discipline. Over the next 17 years, that duo oversaw a dramatic transformation, growing QBE’s net worth from around a $20 million market capitalization in 1981 to $2.1 billion by the end of 1998.

O’Halloran’s climb was steady and deliberate. As he rose through finance, he built a deep, practical feel for insurance economics and a reputation for spotting opportunities others missed. In 1994, before becoming Director of Operations, he spent three months at Harvard. When he returned, he pushed through major management changes aimed at developing talent across the group and strengthening what became known internally as the QBE culture. His style was notably optimistic—focused on finding the positive solution rather than relitigating the past—and it fit a company that was about to ask itself a much bigger question: could it stop being “an Australian insurer with overseas outposts” and become something genuinely international?

By the mid-1980s, QBE was already taking concrete steps toward that future. In 1985, its Hong Kong operations became domesticated, and it opened a new branch in Macau. It was positioning itself in a region on the verge of enormous economic growth—and, just as importantly, building the muscle memory of operating outside Australia as a normal part of the business.

Then came a quieter but pivotal break. In 1991, QBE and Burns Philp ended their 105-year partnership and unwound their cross-shareholdings. It was the end of an era: the insurance business that had once been an extension of a trading-and-shipping empire was now fully on its own. The separation was symbolic, but it was also practical. QBE needed the freedom to pursue acquisitions without being tethered to a parent company with different priorities.

With that independence came acceleration. QBE’s growth increasingly came through acquisitions, including the purchase of Australian Eagle Insurance Company Limited in 1992, and its entry into lenders mortgage insurance with PMI Australia.

By the time O’Halloran became CEO in 1998, the platform was ready. QBE had experience buying and absorbing businesses, it had freed itself from Burns Philp, and it had leaders who believed scale could be engineered—deal by deal—into a global insurer. What followed wasn’t a new chapter so much as a new operating system: QBE as an acquisition machine.

V. The Golden Years: Acquisition Machine on Overdrive (1998-2010)

As the new millennium arrived, QBE leaned into the strategy it understood best—and trusted most: buy growth. It wasn’t shy about using its balance sheet to pick up businesses it believed it could run better, at scale, under a tighter underwriting hand.

The timing couldn’t have been better. Insurance was fragmented, with plenty of mid-sized players that didn’t have the reach or efficiency to compete. Capital was accessible. And O’Halloran had a playbook that, for a while, looked almost unbeatable: find an insurer that’s underperforming, buy it at a reasonable price, cut duplication, apply QBE’s discipline, and let the combined book start throwing off better returns.

A clean example came early. In 1999, QBE bought a 50% stake in Mercantile Mutual. It didn’t rush straight to total control. QBE used the joint venture structure to learn the business and test the fit, then moved methodically to full ownership in 2004. That “stake first, then buy the rest” approach became a hallmark of how O’Halloran managed risk even while moving fast.

Then the world changed overnight. The September 11 attacks hit every global insurer, but QBE came through with one of the smallest net losses among major competitors—despite having worldwide exposure and more than 7% of the total insurance capacity at Lloyd’s. For QBE, it was more than a financial result. It was a proof point. Diversification—by product, geography, and channel—wasn’t just theory. It worked when you actually needed it.

The next test was nature, not terrorism. The hurricanes that hammered the U.S. and the Gulf of Mexico in 2004 and 2005 produced the worst catastrophe losses the industry had ever seen. Katrina, Rita, and Wilma devastated the Gulf Coast. Yet QBE still delivered record underwriting profits. Its geographic spread and reinsurance protections held. While regional players were overwhelmed, QBE’s reputation as a “built for volatility” insurer hardened into something close to legend.

And so the expansion continued. In February 2007, QBE bought Mexican insurer Seguros Cumbre SA de CV and also acquired U.S. insurer General Casualty Insurance. The accumulation in North America was so substantial that QBE’s U.S. businesses grew into a major pillar of the group, contributing a large share of its annualized premium income.

There were other notable deals along the way. In the U.S., acquisitions including Winterthur US, Praetorian, and ZC Sterling built meaningful scale. In the UK, QBE bought Iron Trades Insurance Company Limited and Limit plc in 1999–2000, carving out a strong position in commercial lines and becoming the largest liability underwriter in that market.

Back home, QBE kept adding pieces that deepened its footprint. It entered lenders mortgage insurance by acquiring PMI Australia in 2008—rebranding it as QBE Lenders’ Mortgage Insurance, or QBE LMI. In 2009, it acquired 100% of regional and rural insurer Elders Insurance Limited, along with 75% of Elders Insurance Agency, later taking full ownership of the agency business in 2014.

Through the global financial crisis, the narrative only intensified. O’Halloran was praised for navigating one of the most turbulent stretches the insurance industry had seen, leaning on diversification and conservative investing. In the market’s eyes, the strategy had turned into something close to a formula.

From 2001 through the crisis years, O’Halloran was treated as a corporate mastermind. QBE’s share price surged from around $6 when he became CEO in 1998 to above $35 at its 2007 peak. The company’s growth story felt unstoppable: premiums expanding dramatically, global reach widening year after year, and QBE regularly cited among the top performers on return on equity and operating discipline. Later, Chairman Belinda Hutchinson would describe him as “the architect of QBE’s international expansion.”

Inside QBE, dealmaking became a point of pride. Over his long run, O’Halloran was directly responsible for more than 125 acquisitions, and the internal standard was clear: each deal needed to be earnings-per-share positive in the first year, with only a handful falling short of longer-term goals.

But this is where the golden years start to cast a shadow.

Because buying businesses is one skill. Turning them into one company is another. The empire was getting wider faster than it was getting tighter. QBE ended up running a patchwork of systems—down to basics like multiple payroll platforms—alongside duplicated processes and operational silos that never really merged. Integration often stopped at the financial statements.

The machine kept hunting for the next target. Post-merger clean-up could wait.

And that backlog—quiet, boring, and operational—was about to matter a lot.

VI. The Balboa Bet: The Acquisition That Broke QBE

In early 2011, QBE announced a deal that would fundamentally alter its trajectory: it would buy Balboa Insurance, a California-based insurer, from Bank of America.

On paper, it looked like classic QBE. Bank of America agreed to offload Balboa for more than $700 million. QBE would assume Balboa’s roughly $1.2 billion in insurance liabilities. Bank of America—still in cleanup mode after the financial crisis, having sold stakes in companies like BlackRock and China Construction Bank to help repay bailout-related support—was clearly motivated to simplify. QBE, meanwhile, saw a chance to bulk up in the United States. The market cheered: QBE’s shares jumped 7.7% on the announcement, their biggest one-day gain in three years.

Fund managers framed the purchase as a straightforward boost to QBE’s U.S. operations. Investors also seemed relieved that QBE wasn’t announcing the big capital raise many had feared would be needed to fund yet another deal. For O’Halloran—by then 13 years into the CEO job and already famous for his appetite for acquisitions—it was a familiar message delivered with confidence: this was what QBE did. It would keep growing by buying.

But Balboa wasn’t just another bolt-on insurer. The key to the deal sat inside a niche that most people don’t realize exists until it’s in the headlines: force-placed insurance.

Here’s how it works. Most mortgages require borrowers to keep property insurance in place. If a borrower lets that policy lapse, the lender can step in and buy insurance on the borrower’s behalf—then charge the borrower for it. This is force-placed insurance, also known as lender-placed insurance or collateral protection insurance. In theory, it prevents gaps in coverage and protects the lender’s collateral. In practice, it’s expensive, and in the wake of the financial crisis it became far more common—drawing criticism that it could worsen financial stress for homeowners and, in some cases, contribute to foreclosures. The financial industry’s defense was simple: borrowers who aren’t maintaining their own insurance are higher risk, so the premiums are higher.

Balboa was deeply embedded in that world. It had been acquired by Countrywide Financial in 1999, and when Bank of America bought Countrywide in 2008—one of the most infamous names of the mortgage boom and bust—Balboa came along for the ride. Now Bank of America wanted out. QBE saw a business with distribution, scale, and—at least at the time—attractive economics.

The structure mattered. Alongside the purchase, QBE entered into an initial 10-year distribution agreement with Bank of America covering Balboa’s portfolio: insurance on foreclosed homes and force-placed homeowners coverage, plus related consumer lines like contents and motor, and associated services. Notably, Balboa’s lender’s mortgage insurance business was not part of the transaction.

In the moment, none of that nuance tempered the excitement. The share price pop said it all.

Then the scrutiny arrived.

Force-placed insurance drew the attention of regulators, including the New York State Department of Financial Services, which launched an investigation into the lender-placed insurance industry. That probe ultimately led to settlements involving QBE and Assurant—and it put the Balboa model under a harsh light.

Analysts warned that any political or regulatory response could squeeze profitability. One concern was structural: even if the insurer itself wasn’t the primary wrongdoer, a crackdown could still reshape the market in ways that made the whole product less lucrative. As Merrill Lynch analyst Andrew Kearnan put it at the time, the issue appeared “more one for banks than insurers,” but any resulting changes could pose real risks to insurer margins.

Investigators focused on the money flows around the product. The evidence suggested affiliated agencies and brokers did little or no work to justify the commissions they received. Regulators also highlighted apparent conflicts of interest. The concern was straightforward: when a bank owns—or benefits from—an insurer providing force-placed coverage, the bank’s bottom line can improve as more policies are force-placed. New York officials argued that this created a potential conflict, because the incentives could tilt toward placing more coverage rather than helping borrowers maintain their own.

QBE ultimately settled with New York regulators for $10 million and agreed to compensate homeowners harmed by its force-placed insurance practices. Two years after the Balboa purchase, the company was fined $10 million by New York’s financial services regulator following the probe into the kickbacks and other payments insurers made to banks in exchange for business.

But the regulatory penalties, while painful, weren’t the whole story—and arguably not even the main story.

The deeper problem was execution. Years of acquisition-driven growth had built a sprawling organization that never truly became one company. The Financial Times’ Lex column captured it with a brutal, almost comical detail: a group of roughly 17,000 employees running eight payroll systems. That wasn’t just inefficiency. It was a sign of accumulated integration debt—basic, fixable synergies left untouched for years, until complexity started compounding on itself.

Balboa didn’t just introduce a controversial product line into the portfolio. It collided with an organization already stretched thin by its own patchwork.

And then, finally, the numbers caught up to the narrative. The rise—powered by deal after deal, and a share price that seemed to reward acquisition more than operational improvement—started to look less like durable value creation and more like a mirage. In 2011, QBE announced a 45% fall in profit.

The emperor’s clothes had ripped. And the unraveling had begun.

VII. Crisis & Reckoning: The O'Halloran Departure (2011-2013)

By late 2011, the story investors had been telling themselves about QBE had flipped. The company that had seemed to “diversify its way” through anything was now buckling under the weight of what it had bought—and what it hadn’t integrated.

The cracks became impossible to ignore over the next two years. QBE issued profit warnings and booked painful write-downs in the U.S., alongside additional provisions in Latin America. In 2013, it posted its first annual loss in more than a decade.

For the year, QBE reported a loss after tax of $254 million, compared with a $761 million profit in 2012, driven largely by the already-flagged impairments in North America. Operationally, the business was still underwriting profitably in aggregate, but not nearly to the standard it had promised. Its combined operating ratio deteriorated modestly to 97.8% from 97.1%—a small move on paper, but one that left it “well short” of QBE’s original 92% target.

CEO John Neal, who had taken over after O’Halloran, tried to project steadiness. “That’s pretty much exactly in line with the numbers we communicated on the ninth of December,” he said, pointing back to QBE’s December 2013 market update that had guided to an overall loss of around $250 million.

And the market rendered its verdict. Earnings were squeezed by natural disasters and poor investment returns, and the share price slid back to around $10—barely above where it had been when O’Halloran became CEO in 1998. In a brutal reset, more than a decade of gains effectively disappeared.

O’Halloran announced his retirement in 2012, ending a 35-year run at the organization. He stepped down as Group CEO on August 17, handing the reins to John Neal. Even the Sydney Swans paid tribute—an emblem of how prominent he’d become in Australian business and public life.

He didn’t leave quietly, or cheaply. In August, O’Halloran departed with shares and benefits worth up to $37 million. And QBE made an unusual choice for a company licking its wounds: it granted him an early release from his non-compete.

Within weeks, he was chairing a competitor. By the end of the month, O’Halloran had joined Steadfast Group as chairman as the insurance broker network prepared for an ASX listing.

Steadfast’s executive chairman, Robert Kelly, made the rationale explicit: “We do $760 million worth of business with QBE annually, we’ve had a long-standing relationship with them for many years. We’ve worked very closely with [Frank] over that time,” he said. O’Halloran, in other words, wasn’t just an executive. He was a relationship engine.

Back at QBE, the takeaway was becoming unavoidable. The company had built a collection of businesses more than it had built a single enterprise. Regional fiefdoms ran different systems, different processes, and sometimes seemingly different playbooks. Costs crept up. Complexity piled on. And the “diversification advantage” that looked so powerful on slides didn’t automatically turn into resilience when pressure hit.

For shareholders, it was a hard lesson in how acquisition-driven stories can end: when the share price is powered by deals more than operations, it can unwind fast. The real test doesn’t happen on announcement day. It happens in the unglamorous years after—when the spreadsheets have to become one set of systems, one culture, one underwriting standard.

And QBE, at the worst possible moment, was discovering how much of that work had been deferred.

VIII. The John Neal Turnaround: Cleaning Up the Mess (2012-2017)

The job in front of John Neal was painfully clear: stop the bleeding, simplify the sprawl, and rebuild trust in the numbers.

Neal had taken over as CEO in August 2012, inheriting a company weighed down by North American write-downs and rising claims in Latin America. Instead of chasing the next deal, he ran the opposite playbook: tighten underwriting, strengthen reserving, raise capital, and sell what didn’t fit. He reshaped the management team and elevated people who could execute a clean-up, including Pat Regan, who came in as CFO and later ran the Australian and New Zealand operations.

The plan was explicit. Neal aimed to raise $1.5 billion over two years through a mix of share sales and asset disposals, and he flagged a partial float of QBE’s mortgage insurance business as one option. This wasn’t glamorous strategy. It was balance-sheet triage.

And it came with real costs. QBE agreed to sell its North American mortgage and lender services business to National General Holdings Corp. for $90 million—an exit that crystallized the pain. The transaction produced a pre-tax loss of about $120 million in that year, driven by non-cash charges and write-offs. This was the force-placed insurance-adjacent world: mandatory coverage for borrowers who had lapsed on their original insurance. It had once looked like a high-return niche. Under Neal, it became something QBE needed to get out of, even if doing so meant admitting value had evaporated.

Then came the harder part: taking complexity out of the cost base. Neal announced plans to cut 700 jobs worldwide, part of a broader push to save $250 million a year. QBE narrowed its geographic footprint and reduced its workforce—less empire, more coherence.

After the 2013 loss, Neal kept selling shares and trimming businesses, repositioning QBE around what it wanted to be when the dust settled. The focus, he said, would be commercial lines, with a significant build-out of specialty underwriting capability in North America.

Slowly, the turnaround showed up where it mattered most: the underwriting results. QBE’s U.S. operations—long a source of nasty surprises—moved back into profit after years of losses. By 2016, the group reported net profit after tax of A$844 million, up from A$807 million in 2015. Neal pointed to underwriting discipline across the company, and especially in North America, where the combined operating ratio improved to 97.7% from 99.8% a year earlier. The goal, he said, was a steady march toward the mid-90s over the medium term.

Inside the company, Pat Regan’s profile rose with the results. Chairman Becker credited him with leading a strong turnaround in the Australian and New Zealand operations, and noted that as CFO he had been pivotal in stabilising the balance sheet and improving capital management.

But even as the business steadied, Neal’s leadership ended in noise. In the months before his departure, he became embroiled in controversy over an undisclosed personal relationship with his secretary—something QBE’s code of conduct required him to report. During a media briefing, he faced intense questions about why the board had docked his 2016 bonus by 20%, or A$550,000, tied to that failure to disclose.

The market, meanwhile, wasn’t rushing to forgive the earlier collapse. During Neal’s tenure, QBE shares delivered investors an annualized total return of about 1%, compared with about 21% from peers, according to Bloomberg data at the time.

In 2017, QBE announced Neal would step down after five years as Group CEO. The board appointed Patrick Regan—then CEO of the Australian and New Zealand division and previously Group CFO—as his successor.

Neal left having stabilized QBE and brought it back to profitability. But he didn’t restore the old momentum—and by the end, he hadn’t restored his own standing either.

IX. Leadership Turbulence & The Quest for Stability (2017-2021)

Patrick Regan took over from John Neal on January 1, 2018. He also stayed on the board as an executive director—a signal that QBE wanted continuity at the very moment it was trying to prove the turnaround was real.

Regan looked like the kind of CEO a post-crisis QBE would choose. He’d joined in 2014 as Group CFO, then moved into the CEO role for Australia and New Zealand in August 2016. Before that, he’d built a career in big-company finance and operations: CFO at Aviva in London from 2010 to 2014, Group chief operating officer and CFO at Willis Group Holdings from 2006 to 2010, Group financial controller at Royal & Sun Alliance from 2004 to 2006, and Finance and Claims director for AXA SA’s UK general insurance business from 2001 to 2004.

In other words: controls, discipline, execution. If Neal’s job had been triage, Regan’s was supposed to be the next phase—locking in the habits of a healthier insurer. And for a time, that’s what the story looked like. Then, just as QBE seemed to be finding its footing, COVID-19 hit, and uncertainty returned to every insurer’s calendar and every board’s risk register.

And then QBE was hit by something else entirely.

The company announced that Regan would depart after an external investigation found his workplace communications did not meet the standards set out in QBE’s code of ethics and conduct. QBE said the investigation had been triggered by a complaint from a female employee in the United States.

Chairman Mike Wilkins said the board had completed the investigation and taken “decisive action” based on its findings. He struck a careful balance in public: acknowledging the disruption, thanking Regan for his contribution to strengthening QBE, but making the point that “all employees must be held to the same standards.” Wilkins also emphasized that the fundamentals of the business were strong and that the external pricing environment had improved.

The awkward truth was that this wasn’t even the first time QBE’s CEO story ended in scandal. Regan had replaced John Neal, who later became CEO of Lloyd’s of London—but Neal’s own tenure at QBE had ended with controversy after an undisclosed affair with a personal assistant contributed to a pay cut of A$550,000.

In the immediate aftermath, QBE turned to an internal veteran. The company announced Richard Pryce would step in as interim Group CEO while the search for a permanent replacement got underway. Wilkins, meanwhile, temporarily took on an executive chairman role until a new Group CEO was appointed, before returning to his non-executive chair position.

Pryce was a seasoned operator with deep London-market roots. He joined QBE in 2012, became CEO of European Operations in 2013, and then CEO of International in 2019. He started at Lloyd’s with the R.W. Sturge syndicate, rising to Claims Director, moved into underwriting at Ockham on Syndicate 204, ran ACE’s Financial Lines business in London, and later became President of ACE Global Markets in 2003 and ACE UK in 2007. By the time he took the interim job at QBE, he’d spent more than 35 years in the London insurance market.

By now, the pattern was impossible to miss. Three CEOs in four years. For a company still trying to knit together the legacy of decades of acquisitions, leadership churn wasn’t just a governance problem—it was an operating problem. Culture is hard to build even with steady leadership. With repeated turnover at the top, QBE’s quest for stability got harder, not easier.

X. The Andrew Horton Era: From Specialist to Generalist

Andrew Horton joined QBE as Group Chief Executive Officer in September 2021. After years in which QBE’s biggest problem wasn’t a lack of strategy but a lack of follow-through and consistency, Horton’s mandate was simple to describe and hard to execute: bring the enterprise together.

He arrived from Beazley Group in the UK, where he’d been CEO—and before that, Finance Director—at a specialist international insurer. Before Beazley, he’d held senior finance roles across ING, NatWest, and Lloyds Bank. By the time QBE hired him, he’d spent more than 30 years across insurance and banking, with deep experience in international markets.

Horton was born in Manchester and raised in Bedfordshire. He attended Bedford School, studied natural sciences at Cambridge, and qualified as a chartered accountant with Coopers and Lybrand in 1987. He later became UK chief financial officer at ING and went on to serve as deputy global chief financial officer and global head of finance for the equity markets division of ING Barings. In 2008, he was appointed chief executive of Beazley.

That Beazley chapter was particularly relevant to QBE’s needs. Horton had taken what had been a London-based business and, over more than a decade, helped expand it internationally while growing profitably at around 10% per year. Beazley’s model was specialist and tightly focused. QBE’s was broad, sprawling, and still carrying scars from the era when acquisition outran integration. Horton was moving from a business built around focus to one built around scale—and the job was to make that scale behave like a single company.

From the start, Horton was explicit about what he thought would be hardest. “I think that’s going to be the biggest challenge, because it sounds really easy,” he said, “but getting 11,500 people to think in terms of the enterprise and think about what the organization can do in total and how they can support everybody else.”

His word for the fix was consistency—said so often it became a theme. “I’d like to put consistency into the organization so we’re consistent in the lines of business we are in and do them very well,” he said. “And I’d like people to ensure that we look at the organization in terms of the enterprise in total, rather than the individual parts of it. Consistency is really important to me – and that’s consistency in how we treat our people, consistency in the service, consistency in product offering, consistency in claims payment, consistency in how we deal with regulators, consistency with capital management. It’s across the board and across the whole organization.”

Notably, Horton didn’t arrive with the classic “new CEO, new map” approach. He didn’t need a 100-day reset or a wholesale purge of leadership. QBE, by then, was performing reasonably well across most regions. What it needed was a unifying story and operational continuity. Horton introduced a new purpose around building a more resilient future for stakeholders, and a vision of QBE as “the most consistent and innovative risk partner,” supported by six focus areas—with people and culture described as foundational.

A big part of that, in Horton’s telling, was finishing what had already begun in the United States. QBE’s U.S. business had been through a long remediation cycle, and his priority was to keep simplifying, keep tightening, and then grow in a way that brokers and clients could actually rely on. “We’ve made the business a lot simpler than it was, and it’s having this consistency and continuity,” he said. “We’ve talked about adding cyber expertise in the US, and we’re adding healthcare expertise there and complementary things we can do. So, it’s coming out of a remediation cycle, then into more growth mode, and then ensure we show our broker partners and our clients more consistency than we have done historically.”

He kept coming back to the same point: the last decade had taught the market to expect unevenness from QBE, and that had to change. “So we’ve had a record of some inconsistent returns over the past decade,” he said. And he broadened “consistency” beyond financial metrics: it was also about being a dependable partner. “Consistent in terms of growth. So brokers can grow with us. We can grow with them. So I’d like to do that.”

Underneath that was a lesson Horton said he carried from Beazley: in insurance, the people agenda isn’t a nice-to-have—it’s the business. “I joined Beazley in 2003,” he recalled, “and I’d been going 17 years at that point in time. I’d been in large banks, and I joined this company with 120 people and realised how important the people agenda was and how important the relationships were, and that insurance is a long-term game. So, it’s important to have those relationships. You take the premium in now and you often pay the claim out five, 10 years down the track. So, this is a long-term game, and you need to try and maintain that relationship over that period of time.”

And then, the quiet warning embedded in his philosophy—one that reads like a critique of QBE’s past. Some insurers, he said, behave as though insurance isn’t a long-term game, “chopping and changing” for short-term wins. “And that generally doesn’t work well for the medium to long term.”

XI. Modern QBE: Portfolio Optimization & The AI Pivot

Under Horton, QBE started making choices that would have been almost unthinkable in the O’Halloran years: fewer things, done better. Less “global conglomerate by acquisition,” more “commercial insurer with a clear point of view.”

In 2024, QBE drew one of its sharper lines in the sand. After a strategic review, it announced plans to shut down its North American middle-market segment—a business that wrote about $500 million of gross written premium in 2023 but had struggled for years. Exiting it came with a real price tag: a restructuring charge of about $100 million before tax. But that was the point. QBE was signaling it would rather take pain now than keep carrying underperforming complexity forward.

That same simplification shows up in what QBE chooses to be, and what it chooses not to be. Commercial insurance remains the core. Consumer lines—home and auto—make up less than 5% of global revenue. Horton put it even more starkly in an interview with Insurance Business: personal lines were under 3% of the premium base. In other words, QBE is overwhelmingly a broker-driven business, with brokers bringing in the vast majority of its premiums.

That framing also explains QBE’s next move in North America: a clean exit from “non-core” lines it believes dilute returns. The company has planned to leave the U.S. home insurance market entirely. As of April 2025, QBE covered 37,774 California homes—just 0.36% of the state’s home insurance market in 2024. Not a growth engine; more like a distraction.

The results, at least recently, have supported the strategy. For the quarter ending April 2025, QBE reported an 8% increase in gross written premiums on a constant currency basis, driven by both rate increases and underlying volume growth. In its update for the nine months to September 30, QBE pointed to steady premium expansion and strong investment gains. Underwriting performance was broadly in line with expectations, and catastrophe losses landed well below the company’s budgeted allowance. The group had previously reported a 27% jump in profits in the first half of 2025.

Cat losses are where insurers’ stories usually get rewritten, so QBE’s recent experience mattered. For the first 10 months of 2025, catastrophe costs were estimated at around $700 million—well below the allowance set for the equivalent period. QBE also set aside an additional $200 million for catastrophe losses expected in November and December, and said it expected full-year catastrophe costs to remain comfortably within budget for the third consecutive year.

With that backdrop, QBE reaffirmed its full-year 2025 guidance: mid-single-digit constant-currency premium growth and a group combined operating ratio of about 92.5%. It also announced an on-market share buyback of A$450 million, set to begin in December and run through 2026, funded from surplus capital.

But Horton’s “modern QBE” story isn’t only about pruning the portfolio. It’s also about changing how the work gets done—especially in underwriting, where speed and consistency can become a competitive advantage.

QBE has been integrating artificial intelligence into operations in a tangible way. As the company described it, “QBE launched its first Generative AI solution in December 2023, the Cyber Underwriting AI Assistant, for underwriters in North America which assists cyber underwriters in reviewing broker submissions more quickly.”

Cyber underwriting is a submission-heavy business, and QBE said its team spent about 40% of its time on manual administrative tasks. Using large language models and generative AI, the team built a tool to support initial risk assessment for cyber liability submissions. QBE reported the assistant could perform those initial assessments more than 60% faster—freeing underwriters to focus on higher-priority submissions and improving the submission-to-quote-to-bind funnel.

In 2024, QBE’s AI solution won recognition at the 2024 Insurance Technology Impact Awards. It was a small but telling marker: not AI as a buzzword, AI as throughput—moving work through the pipe faster without lowering standards.

And QBE has been pushing the product edge, too. In July 2025, QBE North America announced AI-focused cyber coverages aimed at emerging risks like AI regulatory compliance and “LLMjacking.” The regulatory coverage was positioned around the EU AI Act coming into force and the rise of state-level AI regulation in the U.S., offering coverage for fines, penalties, and defense costs. The LLMjacking protection addressed the costs that can come with threat actors accessing AI resources—higher service fees and the expense of retraining compromised models.

On the distribution and workflow side, QBE also moved closer to a more digital London market. Ki Insurance partnered with QBE to add it as a capacity partner on Ki’s Lloyd’s-based digital follow platform. QBE capacity became available on the platform from February 3, 2025, for policies incepting from March 1, 2025, spanning 11 open market business classes, including cargo, contingency, cyber, directors & officers (D&O), energy midstream, energy upstream, financial institutions (FI), hull, US professional indemnity (PI), property North America, and property worldwide.

Jason Harris, CEO of QBE International, framed it as part of a broader market evolution: “Digital follow is driving positive outcomes for the market, brokers and insureds by providing faster access to high quality capacity and more certainty of placement and complements traditional underwriting. We anticipate significant growth taking place over the next decade in this space.”

Put it all together and the contrast with QBE’s earlier decades is stark. The old playbook was scale through acquisition. The new one is something more disciplined: simplify the portfolio, stay anchored in commercial lines, and use technology to deliver the kind of consistency Horton keeps talking about—faster decisions, clearer appetite, and fewer surprises.

XII. Investment Thesis: Bull Case, Bear Case, and Key Metrics

Bull Case

The optimistic view on QBE is that Andrew Horton’s era isn’t just a bounce off a low base—it’s a real reset. After decades of buying businesses faster than it could unify them, QBE has been paying down that integration debt: simplifying the portfolio, tightening underwriting standards, and walking away from segments that don’t earn their keep.

The strategic focus is also coherent. QBE is leaning into commercial and specialty insurance, where advantages come less from splashy consumer marketing and more from broker relationships, underwriting judgment, and the ability to offer reliable capacity year after year. On top of that, its early AI work in underwriting is already producing tangible productivity gains, which matters in an industry where speed and consistency can decide whether you win the best risks or get the leftovers.

From a Hamilton Helmer 7 Powers perspective, QBE shows signs of scale economies: global reinsurance purchasing power, shared services, and the ability to spread fixed underwriting and technology investments across a large premium base. It also benefits from switching costs in a practical, relationship-driven sense—brokers don’t lightly abandon underwriters they trust for marginal differences in price. And its Lloyd’s presence, plus specialty capability built over years, gives it a form of counter-positioning that’s hard for more purely domestic, generalist insurers to replicate.

The macro backdrop can help, too. A hardening commercial market can support premium growth for multiple years. And climate change, while dangerous to underwriting results, also increases demand for sophisticated risk transfer—an area where QBE’s diversification and catastrophe modeling capabilities should, in theory, be assets. A multinational book can also provide a kind of built-in hedge, reducing reliance on any single regional cycle.

Bear Case

The skeptical view starts with a familiar problem: North America. QBE has spent years trying to fix this business, and it has historically struggled to deliver consistent, through-the-cycle returns in the world’s most competitive insurance market. There’s a risk the recent improvement reflects pricing conditions more than a durable change in underlying execution.

Governance and culture are another overhang. QBE cycled through multiple CEOs in quick succession, and two consecutive departures came with ethical controversy before Horton arrived. That kind of turbulence doesn’t just create headlines—it can slow decision-making, fracture accountability, and reinforce the “collection of regions” dynamic the company has been trying to escape since the acquisition era.

And structurally, this is a tough industry. A Porter’s Five Forces lens highlights why: competitive rivalry is intense, with large, well-capitalized global insurers fighting hard for the same commercial accounts. Buyer power has risen as brokers consolidate and negotiate more aggressively. New entrants, enabled by InsurTech funding, are a growing factor (even if mostly concentrated in personal lines). Supplier power—reinsurance capacity—ebbs and flows with catastrophe cycles, sometimes compressing margins for primary carriers at exactly the wrong time.

Climate risk is the biggest double-edged sword of all. Yes, it drives demand. But it can also make losses more correlated and harder to diversify away. QBE’s exposure to Australian property—where floods and bushfires have become more frequent—and to North American weather volatility means catastrophe discipline has to stay front-and-center.

Finally, distribution concentration cuts both ways. QBE’s heavy reliance on brokers, while strategic, creates real counterparty dependence. If major brokers shift meaningful placements to competitors, the effect would be immediate and material.

Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you want to know whether “modern QBE” is working, two metrics tell most of the story:

1. Combined Operating Ratio (COR): This is the clearest scoreboard for underwriting. Below 100% means QBE is making money on insurance operations before investment income. The company’s 2025 target of around 92.5% signals solid underwriting, but the bigger question is durability: can QBE hold a mid-90s COR while still growing premiums? If yes, that points to genuine operational improvement. If not—if results only look good when markets are unusually favorable—that’s a warning.

2. North American Combined Operating Ratio specifically: This has been QBE’s long-running trouble spot. The move from 103.7% in 2023 to 98.9% in 2024 is real progress, but it’s still roughly breakeven underwriting. Sustained improvement into the mid-90s would be the strongest evidence that restructuring has truly worked—and it would likely change how the market values the whole group.

One additional check is worth watching alongside these: how much premium growth comes from rate versus new business. Growth that’s mostly price-driven can fade quickly when the cycle turns. Growth that includes real volume, at disciplined terms, tends to be the kind you can build on.

XIII. Conclusion: The Transformation of a Relentless Acquirer

QBE’s 139-year journey—from a marine insurer protecting ships off the Queensland frontier to a global commercial insurance group—reads like a masterclass in what scale can do for you… and what it can do to you.

James Burns and Robert Philp started with a deceptively simple insight in 1886: if you already run the ships, you might as well insure them. From that starting point, they built something far bigger than a local policy book. QI spread quickly along the trade routes of the era, and the Burns Philp relationship provided capital, connections, and a global mindset long before “global” was an Australian corporate default. But it also kept QBE tethered to a parent with its own priorities—until the 1991 separation finally gave QBE the freedom to chart its own course.

That freedom collided with Frank O’Halloran’s defining idea: acquisitions as a growth engine. Over decades, he oversaw more than 125 deals and helped expand QBE from a relatively small insurer into a global player. For years, the strategy looked bulletproof. QBE came through shocks that crushed others—September 11, the brutal U.S. hurricane seasons, and the global financial crisis—seemingly proving that diversification and conservative investing could turn volatility into advantage.

Then came Balboa, and with it the moment the story changed. Force-placed insurance pulled QBE into regulatory scrutiny and reputational risk. But the bigger exposure wasn’t a fine or a headline. It was operational. Balboa didn’t create QBE’s underlying fragility so much as reveal it: years of dealmaking had left behind a company that could report as one group while operating like a patchwork. When the pressure rose, the seams didn’t hold.

What followed was the unromantic part of the movie: write-downs, restructurings, simplification, and leadership turnover at exactly the time the organization needed steadiness. John Neal began the cleanup and returned the company to profitability. Pat Regan continued the effort. Richard Pryce held the wheel in the interim. And Andrew Horton arrived with a mandate that’s harder than any acquisition: make the enterprise behave like one company.

That’s what “modern QBE” has been trying to become. Fewer distractions. Less consumer exposure. A sharper focus on commercial and specialty lines where underwriting judgment and broker relationships matter. Technology not as theater, but as throughput—AI tools that help underwriters move faster without loosening standards. It’s a different posture from the 2007-era QBE: less empire-building, more repeatable execution.

For investors, that creates a familiar kind of tension. QBE offers a diversified platform in global commercial insurance, and the recent results suggest the discipline is real. But the skepticism remains, especially around whether North America can deliver consistent, through-the-cycle profitability.

The core lesson isn’t that acquisitions are inherently good or bad. They built QBE’s global franchise; they also left it with integration debt that eventually came due. The glamorous work is buying companies. The enduring work is making them operate as one.

Frank O’Halloran became a legend by acquiring businesses. Andrew Horton’s opportunity is different: to make a sprawling collection finally move with consistency. And in a world of rising catastrophe risk, evolving cyber threats, and rapid technological change, that ability—worldwide reach, coordinated by a coherent operating model—may be the modern version of Burns and Philp’s original insight.

Whether QBE can turn that into steady returns that match its ambition will determine how this story ultimately ends.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music