Orica: From Gold Rush Dynamite to Digital Blasting Dominance

I. Introduction: When Explosives Became Software

In a dusty control room somewhere in Western Australia’s Pilbara, a blast engineer watches a screen, not a fuse. There’s geology data. Timing models. A wireless status panel that reads more like an air-traffic dashboard than a mining site. A few clicks later, the shot goes. No crews stringing wires through the bench. No one standing nearby. Just a controlled, choreographed detonation designed to break rock the way the plan intended, so the mill downstream runs faster and wastes less.

That’s the modern version of “making things go boom.” And it’s Orica’s bet on the future: turning blasting from an art and a logistics grind into a data-driven, software-enabled discipline.

By fiscal 2024, Orica was a multi-billion-dollar business again in full stride. Revenue came in at $7.66 billion. Earnings jumped sharply, and the company posted its strongest EBIT in a decade, with underlying earnings rising and net profit up year-on-year.

Those figures are the scoreboard. The game is the transformation behind them.

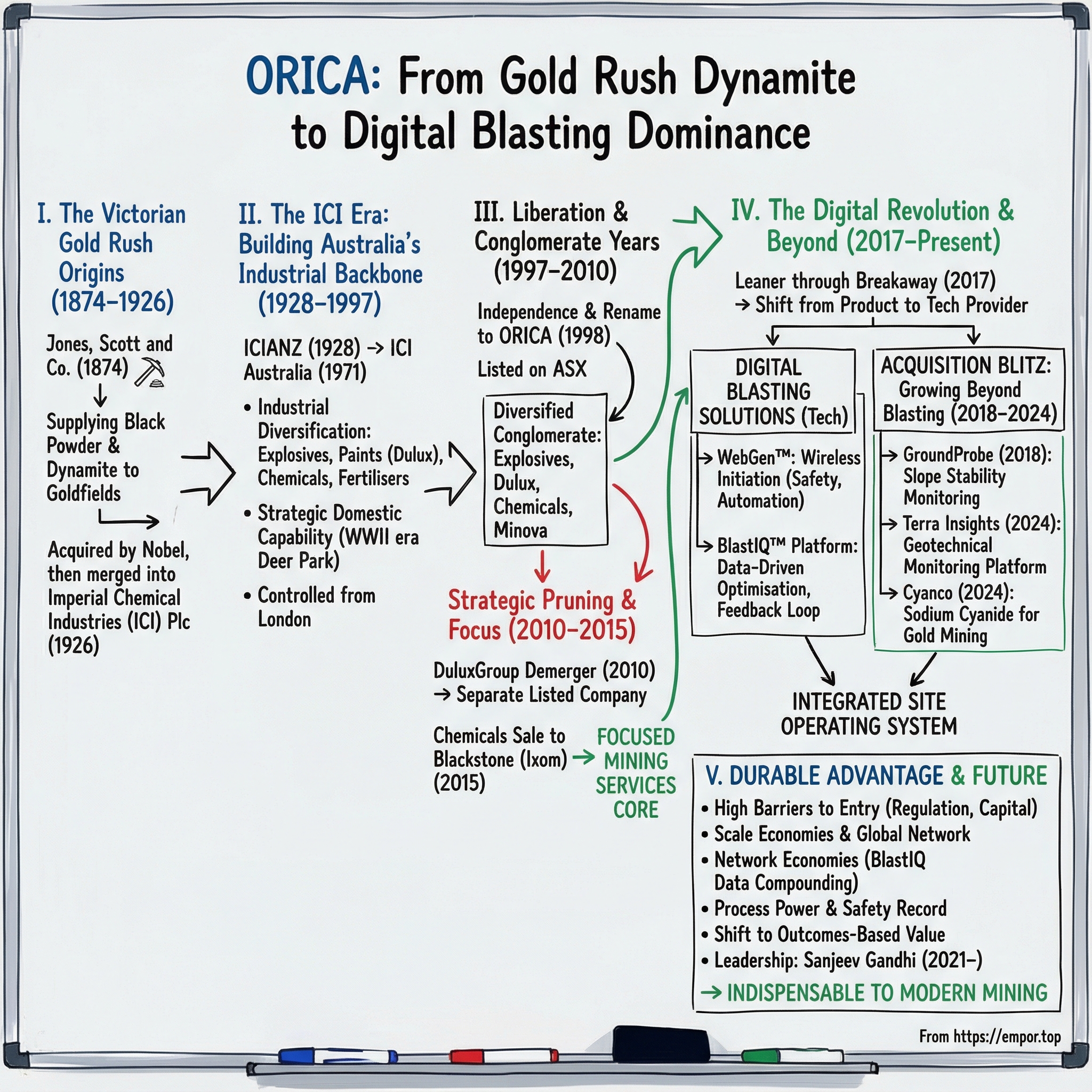

Because Orica didn’t start as a technology company. It started in the Victorian Gold Rush, when “innovation” meant better black powder and a steadier supply chain to the diggings. Over 150 years, through acquisitions, demergers, and multiple identity resets, it grew into one of the most important companies in modern mining—then made the more surprising move: it began trying to look less like a manufacturer and more like a platform.

So here’s the question that frames everything that follows: how does a century-and-a-half-old explosives maker become indispensable to the digital mining revolution? And why does that matter to anyone watching a ten-billion-plus company fight on the fault line between commodity cycles and genuine technology differentiation?

To answer it, we’ll trace Orica’s arc from colonial Australia to British industrial consolidation, from independence to hard strategic pruning, through environmental baggage and leadership turbulence, and into a digital renaissance. Along the way, we’ll see how it came to command roughly 28% of the global commercial explosives market—and why its ambitions now reach well beyond blasting.

II. The Victorian Gold Rush Origins (1874–1926): Dynamite Dreams in the Goldfields

Picture Victoria in the 1870s. Gold fever had been raging since Ballarat and Bendigo, but the easy pickings were largely gone. The next chapter of the rush wasn’t panning in creeks; it was industrial. Gold was still there, but now it was locked in hard rock and buried deeper underground. To get to it, miners needed something more powerful than muscle, picks, and unreliable black powder.

That’s the opening Orica was born into.

In 1874, a small business called Jones, Scott and Co. set up shop supplying explosives to the Victorian goldfields. Over time, that early foothold would grow into Orica—now one of Australia’s leading publicly listed companies, and eventually one of the biggest players in commercial blasting anywhere in the world.

Even in those early days, the demand signal was obvious: Australia was becoming a mining country, and mining at scale runs on dependable blasting. Jones, Scott and Co. wasn’t chasing a novelty product. It was feeding a necessity.

The timing couldn’t have been better. Only a few years earlier, Alfred Nobel had patented dynamite, changing the economics of digging into rock. It was more powerful than what came before, and, critically, more practical to handle. As dynamite spread globally, the race was on to supply it to mines that were going deeper and getting bigger.

Jones, Scott and Co. was eventually bought by Nobel. And Nobel didn’t stop there. Through a wave of mergers with Brunner Mond and Co, the United Alkali Company, and British Dyestuffs Corporation, that lineage ultimately rolled up into Imperial Chemical Industries Plc—ICI.

That purchase plugged the Australian operation into one of the great industrial networks of the era. Yes, that Nobel: the dynamite inventor whose fortune later funded the Nobel Prizes. It’s one of those historical contrasts that sticks—a business rooted in controlled destruction tied, at the top, to global awards celebrating the best of human progress.

Back in Australia, the company evolved quickly. It changed its name to the Australian Explosives and Chemical Company in 1888, and by 1892 it had stopped making powders—moving with the industry away from older formulations toward modern explosives. In 1897, the Nobel Dynamite Trust acquired the Deer Park works near Melbourne.

Deer Park would become a cornerstone site for explosives and chemical manufacturing for decades. It anchored the company’s physical footprint, and it anchored its identity: this wasn’t just trading explosives anymore. It was becoming an industrial producer.

Then, in 1926, the consolidation went supernova. In Britain, Nobel Industries merged with Brunner, Mond & Co., United Alkali Company, and British Dyestuffs Corporation to form Imperial Chemical Industries—ICI.

One merger, and the Australian explosives business found itself inside a global chemical empire. From that moment, the center of gravity shifted. For the next long stretch, the company’s future would be shaped as much by decisions made in London as by demand coming out of Australian mines.

And it’s worth pausing on why this early history matters. It sets patterns that keep repeating across Orica’s life: the business rises and falls with mining activity, it survives by staying close to the technology frontier in explosives and chemistry, and it repeatedly gets pulled into bigger corporate structures—only to later redefine itself again when the structure no longer fits.

III. The ICI Era: Building Australia's Industrial Backbone (1928–1997)

In 1928, Imperial Chemical Industries of Australia and New Zealand, ICIANZ, was incorporated to acquire and coordinate the group’s activities across Australia and New Zealand.

This wasn’t just a tidy corporate reshuffle. It was ICI placing a long-term wager that Australia wouldn’t stay a resource outpost—it would industrialise. And for the next few decades, ICIANZ became one of the companies that made that transformation real.

By the late 1960s, contemporary accounts described ICIANZ as the country’s largest chemical enterprise. It wasn’t a single plant or a single product line. It was a nationwide footprint: manufacturing sites, research laboratories, and an expanding portfolio that touched everything from mining to agriculture to consumer goods.

Then the world lurched toward war, and the stakes changed overnight.

On the eve of the Second World War, ICIANZ installed a high-pressure synthetic ammonia plant at Deer Park. Construction began in January 1939, and by April 1940 it was producing. On site, ammonia was oxidised into nitric acid, and together those feeds enabled the manufacture of ammonium nitrate—critical for munitions, and just as importantly, for fertiliser.

That build-out mattered because Australia’s geographic isolation was both a shield and a vulnerability. Supply chains could be cut. Imports could be delayed or disappear entirely. Domestic capability wasn’t a nice-to-have; it was strategic. In those years, ICIANZ shifted from being a far-flung subsidiary to being infrastructure—something the country depended on.

After the war, the company broadened again. ICIANZ diversified beyond explosives into synthetic fibres, resins, paints, and plastics. Dulux, in particular, grew into a major national manufacturer in consumer coatings, eventually becoming a household name across Australia and New Zealand.

There’s a delicious irony in that: a business with deep roots in explosives ends up helping paint the country’s homes. But it also captures the prevailing corporate logic of the mid-twentieth century. This was the age of the diversified industrial giant—build a portfolio of businesses, share central functions, and try to smooth out the cycles by not betting everything on any one market.

By the end of the 1960s, ICIANZ looked like a miniature industrial empire: R&D labs feeding manufacturing, manufacturing feeding national demand, and thousands of employees building careers inside a company that felt permanent.

In 1971, it changed its name from Imperial Chemical Industries of Australia and New Zealand to ICI Australia.

That rename signalled something bigger than branding. Australian identity was rising, and the local business was increasingly running on local judgment. But the ownership reality didn’t change: ICI Plc still held the majority of shares, and the biggest strategic calls still ultimately flowed from London.

That created a tension that sat quietly for years. ICI Australia served Australian customers and employed Australian workers, but capital allocation and portfolio priorities had to compete with everything else inside the global ICI empire. When the parent came under pressure in the 1990s, that balancing act would stop being sustainable—and the relationship would finally break.

For anyone trying to understand Orica’s later reinventions, the ICI era is the foundation. The manufacturing muscle, the research orientation, and the operating discipline weren’t built from scratch after independence. They were inherited—decades of industrial capability, ready to be pointed in a new direction.

IV. Liberation: Independence and The Birth of Orica (1997–1998)

By the mid-1990s, the global chemicals industry was in one of its periodic identity crises. Investors wanted steadier earnings. Boards wanted higher margins. And ICI Plc in London decided it was done riding the rollercoaster of commodity chemicals. The plan was to pivot “up the value chain” into specialty chemicals—less cyclical, more defensible, more Wall Street-friendly.

That strategic turn created an immediate problem: ICI Australia, with its explosives and bulk chemicals roots, was basically a museum exhibit of the exact businesses the parent wanted to leave behind.

So the break didn’t happen because a rebellious Australian management team demanded freedom. It happened because London needed to sell.

In July 1997, ICI Australia became an independent Australasian company after Imperial Chemical Industries divested its 62.4 per cent shareholding. But independence came with strings: the newly freed company couldn’t keep the ICI name. On 2 February 1998, it reintroduced itself to the market as Orica—and in 1998, it listed on the Australian Securities Exchange.

The name “Orica” didn’t carry heritage or hidden meaning. That was the point. It was designed to be memorable, easy to say in multiple languages, and completely detached from the brand the company had just been forced to abandon. Less a nostalgic rename, more a clean break.

And it arrived at an unusually good moment. Australian mining was recovering from the early-1990s recession. The explosives franchise had solid fundamentals. But now the business had to do what it hadn’t truly had to do in decades: stand on its own. New identity. New capital structure. New strategy—without the gravitational pull of a British parent deciding what deserved investment.

Then Orica pulled off the move that makes this chapter memorable.

The same year it became Orica Limited, the newly independent company bought ICI Plc’s global explosives businesses in Europe and the Americas for £223 million (about A$460 million at the time). In one transaction, Orica went from being a regional Australasian operator to having real international scale.

It’s hard to overstate the irony: ICI Plc pushed ICI Australia out the door… and Orica immediately turned around and bought back the very kind of business the parent no longer wanted.

ICI Plc was exiting commodities and was willing to sell at an attractive price. Orica, no longer constrained by ICI’s portfolio logic, saw the opening to become a global explosives player—fast.

That deal set the pattern for what came next. Orica would use the stability and cash generation of its Australian base as a platform, then expand outward through acquisitions where its technical expertise and customer relationships could travel. Independence wasn’t just a corporate milestone. It was permission to play offense.

V. The Diversified Conglomerate Years (1998–2010)

Independence gave Orica strategic freedom. It also forced an immediate identity question: what, exactly, was this newly liberated company supposed to be?

At first, Orica’s answer was expansive. The business that emerged from ICI Australia looked like a classic diversified industrial: explosives, paints under the Dulux banner, chemicals, and fertilisers. Together, those businesses supplied everything from blasting products for mines, to inputs for water treatment and industrial customers, to household paint and lawn-and-garden offerings. It was a portfolio designed to touch a lot of end markets, in a lot of different ways.

And in theory, it wasn’t crazy. Explosives rise and fall with mining cycles and commodity prices. Consumer paint, by contrast, can throw off steadier cash as people renovate and build. Chemicals and fertilisers widen the base even further. Put them under one roof, and you can imagine smoothing the peaks and troughs—using cash from one division to fund growth in another.

But this is where the spreadsheet story runs into the operating reality.

Selling explosives to a mine is a technical, safety-critical, long-relationship, on-site service business. Selling paint is brand, retail distribution, and consumer marketing. Even if both involve “chemicals,” the muscles you build to win in one are not the muscles you need to win in the other. Inside a conglomerate, that mismatch shows up fast: leadership attention gets split, priorities compete, and capital allocation turns into an internal argument about whose growth matters most.

Public markets tend to be unforgiving here. Investors started to apply the classic conglomerate discount—essentially saying: we’d rather own focused businesses and create our own diversification than pay one company to do it for us.

Orica still pushed to grow where it felt strongest. It bought parts of Dyno Nobel’s commercial explosives business, reinforcing its position in blasting. It also acquired Minova, a specialist in ground support products for underground mining and civil engineering—an adjacency that made intuitive sense if you’re already embedded inside underground operations.

But the central tension didn’t go away. The more Orica tried to be both a consumer brand house and a mining services operator, the more the market questioned whether the whole was actually worth more than the pieces.

By the late 2000s, the board had effectively accepted the verdict: these businesses didn’t belong together. The next chapter would be about focus—not by adding something new, but by letting go of something big.

VI. The DuluxGroup Demerger: Sharpening the Focus (2010)

The global financial crisis was a forcing function for companies everywhere. Balance sheets mattered again. Cycles mattered again. And for Orica, it triggered a blunt strategic realization: if the future was going to be built around mining services, then the portfolio had to start looking like a mining services company.

Dulux was the clearest mismatch. It was a terrific business—market-leading paints and coatings across Australia and New Zealand, powered by trusted brands and steadier, consumer-driven cash flows. But strategically, it lived in a different universe from explosives, blasting systems, and on-site mining services.

So Orica did what conglomerates often resist until they can’t anymore: it separated.

On 9 July 2010, the Supreme Court of Victoria approved the scheme of arrangement to demerge DuluxGroup from Orica Limited. DuluxGroup Limited began trading on the ASX just days later, on 12 July 2010.

The mechanics were straightforward and shareholder-friendly. On 19 July 2010, Orica distributed 100% of its DuluxGroup shares to Orica shareholders. For every Orica share held, shareholders received one DuluxGroup share—meaning investors could keep exposure to both businesses, but now in two cleaner, more focused companies.

The demerger distribution was set at $936,482,384, calculated by reference to the volume weighted average price of DuluxGroup shares of $2.59 as traded on the ASX.

More important than the paperwork was what it signaled. This was the first major step in Orica’s transformation from a broad industrial portfolio into a more focused mining services provider. After the split, Orica kept three core businesses: Mining Services (explosives and blasting systems), Chemicals (industrial chemicals and water treatment), and Minova (ground support for underground mining). Unlike paint, these businesses at least shared customers, operating environments, and technical DNA.

The logic was the one Orica would keep coming back to over the next decade: separation creates freedom. DuluxGroup could chase consumer and construction opportunities without competing for capital against mining projects. Orica could concentrate management attention and investment on the parts of the business where it had the deepest right to win.

For shareholders, this is the classic demerger promise: when two genuinely unrelated businesses stop living under the same roof, the value of focus often outweighs the friction of separation.

And in Orica’s case, Dulux was only the beginning.

VII. Doubling Down: The Chemicals Divestiture (2014–2015)

If the DuluxGroup demerger was Orica admitting that a consumer paint champion didn’t belong inside a mining services company, the chemicals divestiture four years later took the same idea to its logical endpoint: even industrial chemicals—even with some overlap in customers and infrastructure—weren’t part of Orica’s future.

In November 2014, Orica entered an agreement to sell its Chemicals business to funds advised by Blackstone for A$750 million. The package included the Chemicals trading operations in Australia, New Zealand, and Latin America, plus the Australian chloralkali manufacturing business. The sale completed on 2 March 2015, and the business later took on a new name: Ixom.

Strategically, this was Orica choosing to stop straddling two worlds. The chemicals division had real heritage and strong positions, with roots reaching back to nineteenth-century industrial Australia. But it wasn’t where Orica wanted to spend its capital, its leadership bandwidth, or its risk budget.

The decision-making trail matters here. In August 2014, Orica told the market it had finished a strategic review of the Chemicals business and would pursue a separation—either a sale or a demerger. After multiple third parties expressed interest, the board concluded that a sale would deliver higher, more certain value for shareholders than trying to spin it out as a standalone listed company.

That choice also reflected the practical reality: this wasn’t Dulux. The chemicals unit was smaller, and the leap from division to viable public company would have been harder. A private equity buyer like Blackstone could underwrite the transition, drive operational changes, and aim for an eventual exit—without the friction and cost of building a new public-company machine from scratch.

But the deal came with a telltale line in the fine print. Orica would retain responsibility for legacy environmental remediation obligations connected to the Chemicals business.

In other words: Orica could sell the operations, but it couldn’t sell the past. Obligations—particularly associated with the Botany site in Sydney—stayed with Orica. We’ll come back to that, because it becomes a persistent undercurrent in the company’s modern story.

After the chemicals exit, Orica barely resembled the diversified portfolio it had inherited from ICI Australia. What remained was a far more concentrated company: Mining Services at the core—explosives and blasting systems—plus Minova as a close adjacency in underground ground support.

And with that, the strategic question stopped being “what should we own?” and became much sharper: “how do we win, globally, in the businesses we’ve chosen?”

VIII. Leadership Turbulence and The Calderon Era (2015–2020)

Once Orica finished pruning itself into a tighter, mining-focused company, the next challenge was simpler to describe and harder to execute: run it well. And in 2015, that basic job suddenly got a lot harder.

In March 2015, CEO Ian Smith was ousted after allegations of bullying a female employee. Several senior leaders had already departed during his tenure, and his exit triggered more change at the top. Alberto Calderon stepped in, first as interim CEO and then as the permanent appointment, leading the company through to 2020.

The circumstances were striking for a major Australian public company. Instead of the usual vague language about “pursuing other opportunities,” Orica stated the reason directly: bullying of a female employee. Whether that reflected a strong stance on workplace conduct or a pragmatic recognition that the story would surface regardless, the result was the same: a very public leadership rupture at exactly the moment the company needed stability.

The business side didn’t make it easier. After Smith’s departure, Orica’s earnings declined and the company recorded multiple extraordinary charges, alongside significant turnover across the executive team. At the same time, mining markets were deteriorating. Commodity prices had fallen hard from the 2011–2012 highs, and miners were in cost-cutting mode. Explosives demand is tied tightly to mining activity, so when customers slowed down and squeezed budgets, Orica felt it immediately.

Against that backdrop, the board moved quickly. Calderon had been appointed interim Managing Director and CEO on 23 March 2015 while the board ran an international search, and then was confirmed in the role effective immediately.

He wasn’t a typical explosives-industry lifer. Calderon brought more than two decades of senior leadership experience in global mining, including time at BHP Billiton in aluminium, nickel, and corporate development. That background mattered because it gave him something Orica desperately needed: an operator’s view of the customer. He understood how mining companies think about productivity, safety, and cost—because he’d sat on the other side of the table.

Orica later credited him with leading a “much needed operational and cultural transformation,” assembling a stronger and more diverse management team, and putting in place a more customer-focused global operating model. A core piece of that transformation was the push toward a single, global SAP platform.

It’s the kind of project that never sounds inspiring. But for a company operating across dozens of countries, moving hazardous product on tight schedules, and trying to deliver consistent service at mine sites around the world, it’s foundational. Standardised processes, unified data, and one view of the business are the difference between managing globally and merely operating internationally.

Calderon’s tenure also overlapped with the acceleration of Orica’s digital push—the early moves that would later define its competitive positioning. Whether he personally sparked the shift or simply created the conditions for it, the company’s technology investments gathered momentum during these years.

And hovering over all of it was a legacy problem that refused to go away: Botany.

Remediation had begun in 2005 after decades of chlorinated solvent production under ICI led to significant contamination of the Botany aquifer. Orica built a A$167 million Groundwater Treatment Plant to contain that contamination.

It was the clearest reminder of what Orica had inherited along with its industrial capability: not just plants and expertise, but long-tail environmental obligations that demanded real capital and constant management attention—year after year, even as the company tried to reinvent itself for the future.

IX. The Digital Revolution: From Commodity Supplier to Tech Company (2017–Present)

Walk into Orica’s Melbourne headquarters today and the vibe can feel… unexpectedly modern. Yes, this is still a company that makes explosives. But alongside the chemistry and engineering, you’ll find conversations about data pipelines, machine learning, and user experience—because Orica’s most important strategic shift since independence has been getting out of the mindset of “we sell a commodity,” and into the mindset of “we run a technology-enabled system.”

That shift started in earnest in 2017, when Orica kicked off a program called “Leaner through Breakaway.” The goal wasn’t subtle: reposition Orica from being a supplier of mining products to being an indispensable technology provider to the mining industry.

The timing mattered. By then, the mining sector was climbing out of a punishing downturn. Customers had spent years slashing budgets, and now they were looking for a different kind of advantage: tools that could lift productivity and deliver measurable improvements. If Orica could prove it could do that, it wouldn’t just win volume—it could win relevance.

WebGen: The Game-Changer

WebGen™ is Orica’s clearest proof-point that this wasn’t just a slide deck. In early 2017, Orica launched WebGen™, a fully wireless initiating system—one of the key building blocks toward fully automating drill and blast. Since then, it’s been fired in more than 650 blasts across surface and underground mines worldwide.

To understand why customers care, you have to understand the old workflow. Traditional blasting relies on physical wires connecting detonators to the firing system. That means people, in the blast zone, spending time making connections. It adds steps. It adds constraints. And in an industry where safety and uptime are everything, it adds risk and delay.

WebGen changes that by removing the wiring requirement altogether. Orica framed it bluntly:

"The WebGen™ 100 wireless blasting system not only improves safety by removing people from harm's way, it improves productivity by removing the constraints imposed by wired connections and importantly is a critical pre-cursor to automating the charging process. The entire industry is moving rapidly towards an automated future and the introduction of WebGen™ signifies that we, Orica, are serious about being a big part of this automated future."

In explosives, it’s not enough to be clever. You also have to be trusted. WebGen obtained Safety Integrity Level 3 (SIL3) certification through TÜV Rheinland, a global leader in inspection and safety certification. SIL3 is as high as is practically achievable for a commercial blasting product, and it signals the kind of reliability mining operators insist on before they’ll put new initiation technology into production.

And adoption kept building. In the April 2025 issue of Mining & Quarry World, Orica announced WebGen™ had reached 10,000 blasts globally—a milestone that speaks to how quickly “wireless initiation” moved from novelty to normal. The basic promise remained the same: eliminate down-lines and surface connecting wires, improve safety, and simplify operations.

BlastIQ: The Platform Play

If WebGen is the headline hardware innovation, BlastIQ is the software layer that turns blasting into a feedback loop.

The next generation BlastIQ™ Platform is a cloud-based digital platform built to continuously improve blasting outcomes by integrating data and insights from digitally connected tools across the drill-and-blast process. Orica is explicit that each component can create value on its own—but the real payoff comes when customers run it as an integrated system.

This is where Orica’s strategy becomes more than “we have a cool product.” The company’s view is that the difference-maker is what you can learn from the rock—before the shot and after it. With more data, Orica says blasting becomes less guesswork and more controllable: you can model, design, and refine fragmentation outcomes so the entire downstream chain performs better. Orica calls it “digitally enabled blasting,” and the logic is simple: better fragmentation means smoother loading and hauling, more efficient crushing, and fewer surprises in processing.

It’s also where a moat starts to form. Every blast generates data. Data improves models. Better models improve outcomes. Better outcomes win more blasts. Over time, that creates a compounding advantage: the platform gets smarter as it’s used.

Orica’s Chief Commercial Officer, Angus Melbourne, put the customer value in context:

"The downstream impact of variable and poorly controlled blast outcomes today can impact as much as 80% of the Total Mine Processing Costs. The new BlastIQ™ Platform enhances blast performance and outcomes for customers by seamlessly connecting data under a single platform."

The point isn’t that blasting is the biggest line item in a mine’s cost structure. It’s that blasting sets the terms for almost everything that follows. When the blast is right, the whole operation gets easier. When it’s wrong, the entire mine pays for it.

The SAP Transformation

All of this customer-facing technology only works if the company behind it can execute consistently, globally. And that required a less glamorous—but absolutely foundational—investment inside Orica itself.

During this era, Orica also moved toward a single, global SAP platform. The largest and final phase of the SAP program was implemented in July 2020. Branded internally as 4S—“Simple, Standard, Single SAP”—the project consolidated Orica’s operations onto an S/4HANA core, covering eight end-to-end business processes.

It’s the kind of transformation customers never see directly. But it’s what makes the digital story real: standardised processes, shared data, and the operational backbone to deliver the same level of service at mine sites across dozens of countries—safely, reliably, and at scale.

X. The Acquisition Blitz: Building the Moat (2018–2024)

Orica’s digital transformation wasn’t just an internal R&D story. In parallel, the company went shopping—using acquisitions to accelerate what it could offer on a mine site, and to widen its reach into the parts of mining where data, monitoring, and specialty chemicals can become as “mission critical” as the blast itself.

GroundProbe (2018): Slope Stability Monitoring

In 2018, Orica entered into an agreement to acquire GP Holdco Pty Ltd (GroundProbe) from Crescent Capital Partners for A$205 million. GroundProbe was already a global market leader in monitoring and measurement technologies for mining. Its radar- and laser-based systems, paired with processing and analytics software, help mines track geotechnical slope stability—an essential input for both safety and productivity in open pits.

Orica framed the rationale in a way that fits perfectly with the BlastIQ thesis:

"We believe the potential for data-driven improvement in the drill and blast component of the mining value chain is significant. By integrating GroundProbe's capabilities alongside Blast IQ™ and Nitro Consult, we are able to expand the digital solutions we can offer to help customers improve safety, productivity and environmental outcomes."

On the ground, the linkage is intuitive. Slope stability determines when and where people and equipment can safely work near pit walls. And while slope failure is a geotechnical problem, blasting practices can influence it. Orica was already embedded with customers at the exact point where those worlds meet—designing blasts, executing them, and now potentially monitoring how the rock mass responds.

Terra Insights (2024): Geotechnical Monitoring Platform

Fast-forward to 2024, and Orica doubled down. The company acquired 100 per cent of Terra Insights (Terra), an end-to-end sensors, software, and data delivery platform for geotechnical, structural, and geospatial monitoring across mining and infrastructure, for an enterprise value of CAD$505 million.

"The Terra Insights acquisition was completed on 29 February 2024. This acquisition has established Orica as the global leader in geotechnical and structural monitoring in mining and civil infrastructure with a unique portfolio of six industry-leading brands."

Terra brought a bundle of specialised monitoring businesses under one roof, including RST Instruments (inclinometers and piezometers for geotechnical and structural monitoring), Measurand (ShapeArray inclinometers for deformation monitoring), 3vGeomatics (InSAR-based monitoring for subsidence and geohazards), Syscom Instruments (vibration and seismic monitoring), and NavStar Geomatics (GPS/GNSS-based vibration and seismic monitoring).

The strategic effect was clear: alongside GroundProbe, Terra expanded Orica’s digital solutions footprint beyond blasting into a broader “rock and risk” monitoring stack—positioning Orica as a global leader in monitoring technologies for mining and civil infrastructure.

Cyanco (2024): Sodium Cyanide for Gold Mining

Then came an acquisition that looks, at first glance, like it belongs to a different playbook.

"On 30 April 2024, we finalised the completion of our Cyanco acquisition. With the addition of Cyanco, Orica has now become the leading integrated global sodium cyanide producer and supplier, with access to the attractive and high margin North American gold market."

Cyanco brought two sodium cyanide manufacturing plants in Nevada and Texas. Orica said the deal more than doubled its sodium cyanide production capacity from Yarwun, Australia to approximately 240,000 t/y, and significantly expanded its footprint in North American gold mining, with manufacturing assets strategically located around cost-competitive U.S. natural gas.

The enterprise value was US$640 million on a cash-free, debt-free basis (equivalent to A$985 million).

Unlike GroundProbe and Terra, Cyanco wasn’t about sensors and software. It was about moving further downstream into what happens after the rock is blasted and hauled. Sodium cyanide is essential for gold extraction: miners use cyanide solutions to dissolve gold from ore. With Cyanco, Orica could offer gold miners more of the critical consumables they depend on—not only explosives to break the ore free, but also a core input to process it.

Put together, these moves made the strategy explicit. Orica was still committed to profitably growing its core blasting franchise. But the ambition was bigger:

This follows completion of the recent Cyanco acquisition in the Specialty Mining Chemicals segment, and the Terra Insights acquisition in the Digital Solutions segment. Both acquisitions are in line with Orica's strategy to 'grow beyond blasting' while continuing to profitably grow its core blasting business.

“Grow beyond blasting” is the tell. Orica doesn’t want to be the company that shows up for the boom and leaves. It wants to be integrated into the full operating system of a mine—measuring the ground, shaping the blast, and supplying the chemicals that pull value out of the ore afterward.

XI. Porter's Five Forces: Anatomy of a Defensible Position

To see why Orica has held its ground—and why it’s been able to expand “beyond blasting”—it helps to step back and look at the industry structure itself. Porter's Five Forces is a useful lens here, because commercial explosives is one of those markets where the rules are set less by marketing flair and more by physics, regulation, and logistics.

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

This is a hard industry to break into, and it gets harder every year.

Start with the basics: the commercial explosives market is already highly consolidated, with the top five players taking the majority of the revenue. That matters because scale isn’t a nice-to-have here; it’s the entry ticket.

Then there’s manufacturing reality. Ammonium nitrate is the essential ingredient in modern commercial explosives, and producing it at scale requires enormous capital, complex engineering, and the right location. Plants need access to the right inputs—especially natural gas, which underpins ammonia production—and they need to be built through a maze of approvals long before a single tonne of product is sold.

And even if you can fund the plant, you still have to win permission to operate. Explosives are among the most regulated products on earth. Government permits, security clearances, and safety certifications aren’t just paperwork—they’re ongoing obligations, with regulators watching closely and continually.

Finally, there’s a newer barrier that didn’t exist when Orica first went global: software lock-in. Once a customer integrates BlastIQ into day-to-day operations, switching isn’t just changing suppliers. It means giving up historical performance data, retraining teams, and risking disruption in an operation that measures downtime in millions.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Orica’s key inputs—ammonia, natural gas, and ammonium nitrate—are commodities. There are multiple suppliers, so no single vendor typically has the ability to dictate terms.

But commodity inputs come with commodity volatility. Energy markets swing, geopolitics matters, and inflation doesn’t politely stop at the mine gate. Natural gas prices in particular can move sharply, and when they do, they ripple through the cost base.

Orica leans on longer-term contracts and escalation clauses to reduce the whiplash. Still, margins remain exposed to movements in input costs, because you can’t fully financial-engineer your way out of physics.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

On the other side of the table are some of the most sophisticated buyers in the world: BHP, Rio Tinto, Glencore, and other mining giants with serious procurement muscle. They negotiate hard, and they’re large enough that losing one contract is not a rounding error.

But buyer power has limits. Explosives are rarely the biggest cost line in a mine. And the true cost of blasting isn’t the invoice—it’s what happens downstream when fragmentation is wrong: poorer ore recovery, inefficient crushing, more variability, and higher safety risk. Those consequences can overwhelm any savings won through price pressure.

That’s why the smartest mining customers increasingly buy on total cost of ownership, not unit price. It’s also why Orica’s pitch has shifted from “we’ll deliver product” to “we’ll deliver outcomes.” Multi-year service contracts help, too: once you’re embedded on-site and operating as part of the mine’s system, negotiations don’t reset every month. Add BlastIQ into the workflow, and switching becomes even less appealing.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW

In hard rock mining at scale, there’s no real substitute for explosives. Mechanical breaking and other alternatives are typically too slow, too expensive, or both. As long as the world wants copper, iron ore, gold, and the rest, mines will need controlled blasting.

What is changing is the operating environment around the blast. Electrification and autonomy are reshaping fleets—but that tends to increase the value of precision, not reduce it. Autonomous haulage works best when the rock size distribution is consistent, and consistent rock fragmentation starts with the blast. In that world, blasting becomes even more foundational.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

This is an oligopoly, not a free-for-all. Globally, Orica, Dyno Nobel, MAXAM, and Enaex account for a large share of commercial explosives sales. In Australia, Orica and Dyno Nobel are the dominant forces. Markets like this usually produce steady, moderate rivalry: competitors fight hard for contracts, but they typically compete on reliability, service, and technology rather than lighting the industry on fire with price wars.

That said, rivalry is real—and it’s increasingly multi-dimensional. These companies aren’t just selling bulk explosives anymore. They’re selling systems: manufacturing footprint, site service teams, initiation technology like WebGen, and software layers that promise measurable operating improvements.

Orica’s acquisition of Cyanco added another angle to that competition. By expanding its sodium cyanide position in gold, Orica gained the ability to pitch a broader package to certain customers—linking drill-and-blast more closely to downstream processing.

Competitors are moving too. MAXAM’s investment into additional Chilean capacity shows how regional depth can shift share in a meaningful way, even in a consolidated market. And Dyno Nobel has been sharpening its identity as well: after shareholder approval at the 2024 AGM on 19 December 2024, Incitec Pivot Limited changed its name to Dyno Nobel Limited, with its ASX ticker scheduled to move from IPL to DNL from the start of trading on 2 April 2025.

The takeaway is simple: Orica operates in an industry where the barriers are high, substitutes are few, and rivalry is contained—but the basis of competition is evolving fast. The fight is moving from who can supply explosives, to who can run the most valuable operating system around the blast.

XII. Hamilton's 7 Powers: The Sources of Durable Advantage

Hamilton Helmer’s framework lays out seven “powers” that let a company earn above-average returns for a long time. Orica is a great test case, because it competes in a business where scale and safety matter, but it’s also trying to build something that looks more like a data-driven platform.

Here’s how Orica stacks up.

Scale Economies: STRONG

Orica’s roots go back to supplying explosives to Australia’s goldfields, and over more than a century of expansion and reinvention, it grew into a global business serving mining, construction, and oil and gas.

That history shows up in the thing that matters most in explosives: physical scale. Orica operates the world’s largest ammonium nitrate production network. That scale drives advantage in a few compounding ways: manufacturing costs fall as fixed plant and compliance costs are spread over more output; procurement gets cheaper with volume; and R&D becomes easier to justify when innovation can be deployed across a massive customer base.

But the hardest piece to replicate isn’t just production. It’s distribution. Explosives aren’t shipped like normal industrial products. Moving them safely and legally across borders requires specialised logistics, deep regulatory capability, and infrastructure that’s expensive to build and slow to permission. That global network is a durable moat, because the cost and time to replicate it are punishing.

Network Economies: EMERGING

BlastIQ is where Orica starts to look less like a manufacturer and more like a learning system.

The next generation BlastIQ Platform is cloud-based software designed to continuously improve blasting outcomes by integrating data from digitally connected tools across the drill-and-blast workflow. The more blasts it sees, the more its models can learn. Each shot adds training data, which improves predictions and recommendations for the next one.

That’s an emerging network economy: more usage makes the product better, and a better product attracts more usage. It’s not a consumer-social-network flywheel, but in industrial software, the bar isn’t “viral growth.” The bar is “can your system get meaningfully smarter over time in a way competitors can’t easily copy?” Orica is building toward that.

Counter-Positioning: STRONG

Orica calls its approach “digitally enabled blasting,” and the concept is simple: wireless initiation and data-driven design help optimise fragmentation, which can reduce downstream processing pain.

This is counter-positioning because it asks competitors to change what made them successful. Traditional explosives companies are built to win on high-volume commodity supply: sell tonnes, optimise plants, keep unit costs down. Orica is trying to shift the basis of competition toward technology-enabled outcomes.

For rivals, matching that isn’t just “spend more on software.” It risks cannibalising parts of their current business model while demanding new capabilities in data, product design, and field implementation. And it runs into organisational inertia: sales teams trained to sell volume, incentives built around tonnes shipped, and operating rhythms designed for commodity efficiency, not platform adoption.

Competitors are responding, but counter-positioning works precisely because response is difficult, slow, and internally contentious.

Switching Costs: BUILDING

Once Orica is embedded, it becomes hard to dislodge.

BlastIQ Underground is positioned as an end-to-end digital workflow: planning, approvals, execution, and analysis, connected in real time and built to reduce manual processes. When a mining operation integrates a system like that—training teams, connecting it to fleet management systems, and building up historical performance data—the cost of switching stops being “price per tonne” and becomes “operational disruption.”

And the software is only part of the stickiness. Orica also places people on site. Those technicians learn the specific conditions of a mine and build day-to-day working relationships with customer teams. That combination—tools plus humans plus process—is a classic source of switching costs in industrial services.

Branding: MODERATE

Brand matters differently in B2B than it does in consumer markets, but in explosives it still matters. Mines are making high-stakes decisions where safety and reliability are non-negotiable. Orica’s long operating history and reputation help when customers are committing to multi-year relationships and trusting a supplier inside mission-critical operations.

In this industry, “brand” is less about awareness and more about credibility: will this company perform safely, consistently, and with the maturity to handle what can go wrong?

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

WebGen has won industry recognition, including the Austmine METS Innovation Award, and Orica holds patents around its wireless initiation technology. That’s real protection—but patents expire, and competitors can often engineer alternative routes to similar outcomes.

The more durable cornered resource may be less about patents and more about learning. Orica’s accumulated data from thousands of blasts across different rock types and conditions feeds the models behind BlastIQ. That dataset can’t be bought off the shelf or recreated quickly; it has to be earned through execution at scale.

Process Power: STRONG

Explosives manufacturing and blasting services reward something that doesn’t show up well in glossy product demos: institutional process.

Handling explosives safely, repeatedly, across many sites and jurisdictions requires operational discipline that takes decades to build. A competitor can copy visible features, but it’s much harder to copy the tacit knowledge embedded in how a company trains people, runs compliance, manages risk, and executes under real-world constraints.

This is where Orica’s age actually helps. In a business where mistakes are catastrophic, the advantage often belongs to the company that has learned, over generations, how not to make them.

XIII. The Bear Case vs. Bull Case

The Bear Case

Commodity Exposure Remains

For all the progress on digital, Orica is still tied to the mining cycle. When commodity prices fall, miners pull back on production and projects. That usually means fewer tonnes moved, fewer benches blasted, and less demand for explosives and on-site services. In that environment, even “premium” offerings can get dragged into procurement-driven cost cutting.

Digital Premiums May Not Persist

Orica can command higher prices when it’s selling outcomes instead of tonnes. But those premiums only last if the outcomes stay differentiated. Competitors are investing in their own digital capabilities, and if the market starts to view wireless initiation, data platforms, and analytics as table stakes, Orica’s pricing power could narrow. In industrial technology, advantage often comes in waves—today’s lead can become tomorrow’s expectation.

Environmental Liabilities

Orica’s history comes with long-tail obligations, and Botany is the clearest example. The company built an A$167 million Groundwater Treatment Plant to contain contamination and supply high quality industrial water to Botany Industrial Park. Orica says the water produced by the plant saves Sydney’s potable water supply around 5 megalitres per day.

Even with that progress, the underlying remediation commitments stretch decades into the future. They’re a persistent claim on cash flow—and environmental liabilities have a way of getting more expensive, not less, especially if regulations tighten or new issues surface.

Integration Risk

Orica has been active on the acquisition front, including Terra Insights and Cyanco. Deals can look perfect on paper and still fail in practice: cultures clash, systems don’t integrate cleanly, key people leave, and expected synergies arrive late or not at all. The more deals you do, the more you ask management to run two businesses at once: today’s operation, and tomorrow’s integration.

Competitive Response

Orica isn’t playing alone. In 2008, Australian agrochemical maker Incitec Pivot Limited bought Dyno Nobel for A$3.3 billion, keeping a powerful rival in the mix with deep customer relationships and its own technology agenda. And as Dyno Nobel’s structure has sharpened, its explosives business could become even more focused and aggressive. If rivalry intensifies, it will show up where it always does: contract pricing, renewal terms, and margin pressure.

The Bull Case

Technology Moat Is Widening

Orica’s best argument is compounding learning. Every blast adds data into BlastIQ, and more data improves the models and recommendations. Network effects here don’t look like social media—they look like better fragmentation, more predictable outcomes, and customers who don’t want to give up a system that’s getting smarter in their specific rock. Competitors can build software, but they’re starting later, with less operational data and fewer feedback loops already in motion.

"Beyond Blasting" Expands the Addressable Market

Both acquisitions are in line with Orica's strategy to 'grow beyond blasting' while continuing to profitably grow its core blasting business.

This is the strategic unlock: Orica doesn’t have to live and die purely by explosives volume. With GroundProbe and Terra Insights, it stretches into monitoring, risk, and site intelligence. With Cyanco, it steps into a key processing chemical for gold. The combined offering moves Orica closer to being a strategic partner across the mining value chain—from understanding ground movement, to optimizing the blast, to supporting extraction chemistry—rather than a supplier chosen mostly on price.

Critical Minerals Demand Provides Secular Tailwind

The energy transition is a multi-decade mining buildout. Copper, lithium, nickel, and other critical minerals still have to come out of the ground, and hard-rock mining still runs on blasting. Even if some commodity categories stagnate or decline over time, the long-term demand for “digging, breaking, and processing rock” is difficult to escape.

Margin Expansion Potential

We have delivered another strong performance in the 2024 financial year with a 15 per cent growth in EBIT.

The bullish read is that Orica is changing its mix. More technology-enabled services—WebGen, BlastIQ, and broader digital solutions—should mean better margins than commodity explosives alone. If Orica can keep proving measurable customer outcomes, it can keep shifting the conversation away from unit price and toward value delivered. Recent performance suggests that trajectory has already started.

Balance Sheet Strength Supports Continued Investment

Gearing excluding lease liabilities at 26.2 per cent at 30 September 2024 is below our target range of 30 to 40 per cent.

Transformation is expensive when you don’t have the capacity to fund it. Orica’s balance sheet gives it room: to keep investing in R&D, to keep scaling digital products, and to pursue selective acquisitions without betting the company. That financial flexibility matters in a cyclical industry, because the winners are often the ones who can keep building through the downturns.

XIV. Leadership Today: The Gandhi Era

In April 2021, Orica handed the CEO role to Sanjeev Gandhi. It was an internal promotion—he’d been Group Executive and President for Australia Pacific & Asia—but it also marked a clear shift in what kind of leader Orica wanted for the next phase.

Gandhi wasn’t cut from the same cloth as Alberto Calderon. Calderon came from the customer side of the table, with a mining pedigree shaped at BHP. Gandhi came from the factory side—from chemicals—after a 26-year career at BASF SE, the German giant that’s as close as this industry gets to a global operating system.

At BASF, Gandhi moved through senior marketing, commercial, and business leadership roles, ultimately becoming Executive Director and Head of Asia Pacific, and Head of BASF’s Global Chemicals Segment (Intermediates & Petrochemicals). Based in Hong Kong, he led more than 18,500 people across 19 countries, spanning 125 production sites and 140 sales offices, with accountability for €13.3 billion in revenue and €1 billion in EBIT.

That context matters. Running a €13 billion operation is larger than Orica’s entire business. And while stepping from a corporate executive role at BASF into the top job at Orica may not be a jump in organisational scale, it is a jump in accountability. At Orica, the buck stops with him—strategy, capital allocation, culture, performance, and the credibility of the transformation.

Gandhi also carries a milestone of his own: he became the first Indian to serve as Head of Asia Pacific and as a member of BASF’s Global Board of Directors.

Since taking over, Orica has kept moving in the direction the last chapter set up—more technology, more adjacency expansion, and a broader definition of what the company is. Terra Insights and Cyanco both closed during Gandhi’s tenure, and Orica’s shift to new segment reporting followed too, aligning how the business tells its story with what it’s becoming.

XV. What Investors Should Watch

If you’re evaluating Orica as a long-term investment, the story now comes down to a few signals that tell you whether the transformation is real, durable, and compounding—or whether it’s mostly narrative.

Three are worth watching most closely:

1. Digital Solutions Revenue Growth and Margin

Orica now reports Digital Solutions as its own segment, which is a big tell in itself: management wants the market to judge it as more than an explosives supplier.

In FY2024, Digital Solutions EBIT came in at $70 million, up 29 per cent on the pcp, driven by continued adoption of digital products and helped by the ongoing integration of Terra Insights.

The reason this matters is simple. If Digital Solutions keeps growing and margins expand, Orica’s “beyond blasting” thesis starts to look like a real economic engine, not just a set of interesting products. If growth stalls or margins compress, it raises the harder question: are these truly differentiated software-and-data offerings, or are they features that will get competed down over time?

As Orica discloses them, pay attention to annual recurring revenue (ARR) and churn rate. Those are the closest thing to a lie detector for whether the platforms are becoming embedded in customer operations.

2. Premium Product Mix Within Blasting Solutions

Even if Digital Solutions shines, Orica still lives and dies by blasting. And inside Blasting Solutions, the key isn’t just volume—it’s mix.

The spread between commodity explosives and premium offerings like WebGen, 4D bulk systems, and broader technology-enabled services will do a lot of the work in determining margin quality. A rising premium mix, without sacrificing volumes, is what “digital blasting” looks like when it shows up in the income statement. A falling premium mix is often the earliest sign of competitive pressure, customer pushback, or a premium that’s proving harder to defend than expected.

3. Return on Net Assets (RONA)

RONA is the scoreboard for capital discipline.

It increased from 12.6 per cent in FY2023 to 12.8 per cent in FY2024. On its own, that’s a modest move. But direction matters here, because RONA captures both sides of the reinvention: improved margins from higher-value offerings, and the capital intensity required to deliver them.

Sustained improvement would suggest Orica is getting real economic leverage from its investments—earning better returns, not just growing bigger. If RONA stagnates or falls as the company keeps spending on digital and acquisitions, it’s a sign the strategy may be building complexity faster than it’s building value.

XVI. Conclusion: The Art and Science of Making Things Go Boom

Orica’s journey—from a colonial-era explosives supplier to a digitally enabled mining services provider—is a case study in how legacy industrial companies can reinvent themselves, but only when they’re willing to make hard choices and then execute relentlessly.

The business Alfred Nobel’s successors absorbed into the ICI orbit a century ago would barely recognize Orica today. This is still a company that moves molecules and manages extreme physical risk. But it’s also a company that runs cloud platforms, applies machine learning to blast performance, and increasingly sells a promise that sounds more like enterprise software than explosives: better outcomes, measured and repeated.

That shift—from shipping tonnes of product to delivering optimised blast designs—gets at the heart of what “durable advantage” looks like in an old-line industry. Orica isn’t trying to win by being the cheapest supplier in a commodity market. It’s trying to win by being the system its customers build around.

For investors, that creates a fascinating hybrid. You’re still exposed to the mining cycle. But you also get the possibility of technology-style economics: deeper customer lock-in, higher-value product mix, and a platform that improves as it’s used. The bull case is straightforward: WebGen and BlastIQ widen the moat, while acquisitions like GroundProbe, Terra Insights, and Cyanco expand the addressable market “beyond blasting.” The bear case is just as clear: the commodity cycle still sets the weather, and aggressive M&A always carries integration risk.

So the whole story collapses into one question: is Orica building a lasting edge, or just enjoying a temporary lead?

If BlastIQ’s models genuinely compound with data, and if WebGen’s wireless initiation becomes the default way mines operate, Orica could capture outsized value as mining becomes more automated and more measured. But if competitors close the gap and these tools become table stakes, the industry’s gravity will reassert itself—and margins will drift back toward commodity levels.

Either way, 150 years after Jones, Scott and Co. started supplying explosives to Victoria’s goldfields, the core truth hasn’t changed. Mining still needs rock broken safely, predictably, and at scale. The tools have evolved—from black powder to wireless detonators—but the job remains the same.

And that’s the final twist in Orica’s story: in a world obsessed with “picks and shovels” exposure to big secular trends, Orica sells something even more elemental. Not the picks. Not the shovels. The controlled force that makes modern mining possible in the first place. Whether that deserves a premium valuation comes down to belief—belief that the technology transformation is real, and belief that it’s durable enough to survive the next competitive response.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music