Origin Energy: Australia's Energy Transition at the Crossroads

Introduction and Episode Roadmap

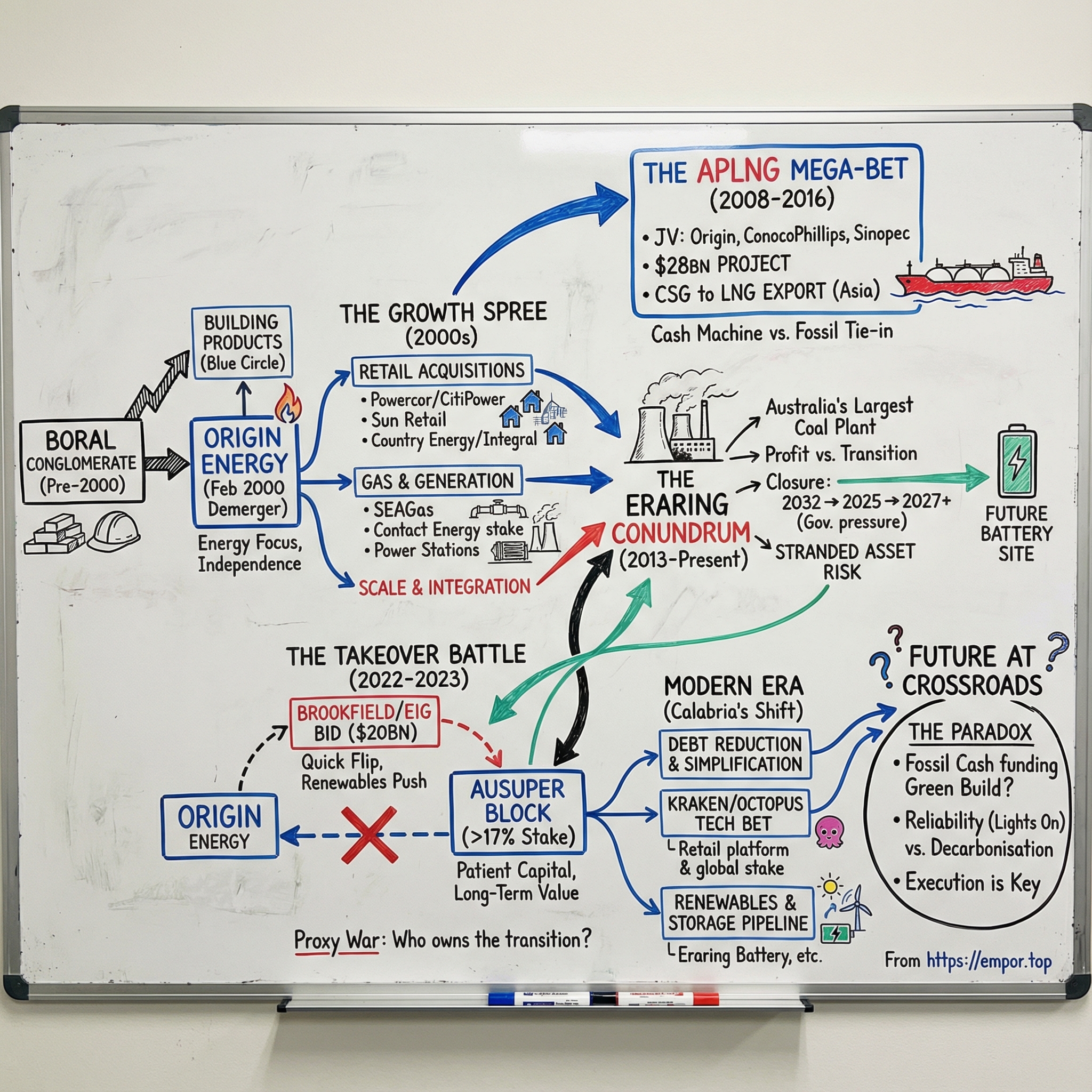

Picture this: a sweltering Australian summer afternoon in February 2022. Origin Energy CEO Frank Calabria steps up to deliver the company’s half-year results from Barangaroo in Sydney. And then he drops the bomb that ripples through the entire sector: Origin will close Eraring, Australia’s largest coal-fired power station, seven years earlier than planned. The economics, he says, have become “increasingly unsustainable.”

“Origin's proposed exit from coal-fired generation reflects the continuing, rapid transition of the NEM as we move to cleaner sources of energy,” Calabria said. “Australia's energy market today is very different to the one when Eraring was brought online in the early 1980s, and the reality is the economics of coal-fired power stations are being put under increasing, unsustainable pressure by cleaner and lower-cost generation, including solar, wind and batteries.”

In one announcement, Calabria crystallized the impossible tension at the heart of Origin’s story—and Australia’s broader energy dilemma. How does a company that started life inside a building materials conglomerate become one of the country’s most powerful energy businesses, make a giant bet on LNG exports to Asia, buy the nation’s biggest coal plant, and then try to decarbonize… without blackouts, political backlash, or stranded assets?

Zoom out and Origin is enormous. It’s a vertically integrated Australian energy company with the largest energy retailing business in the country—about 4 million customers and roughly a third of the market. Through its Australia Pacific LNG joint venture, it supplies around 30% of east coast domestic gas demand and exports LNG across Asia. In 2025, Origin generated $17.3 billion in revenue and employed 5,420 people.

But this isn’t a story about size for its own sake. It’s a story about timing—and about a handful of strategic moves that locked Origin onto a path where every decision has second-order consequences. Three threads drive the plot: the Boral demerger that created Origin, the APLNG mega-bet that reshaped it, and the Eraring coal plant conundrum that now defines its transition challenge. Woven through all of it is the failed Brookfield takeover—one of the most dramatic corporate battles in recent Australian history—and the bigger, messier question underneath: what does “leading the energy transition” actually look like when you still have to keep the lights on?

For investors, that’s the paradox. Eraring can throw off huge profits today while carrying an uncertain tomorrow. LNG can be a steady source of cash—while tying the company to fossil fuels for decades. And the transition investments that everyone agrees are necessary may not earn returns that feel adequate for the capital they consume. It’s this calculus that sat behind AustralianSuper’s stance as Origin’s biggest shareholder when it helped torpedo the Brookfield takeover: a bet that patient ownership could be worth more than a private equity consortium’s “quick flip.”

The Unusual Birth: From Boral Demerger to Energy Independence

Origin Energy doesn’t start with a lone founder, a garage, or a breakthrough invention. It starts with something far more common in late-1990s Australia: a big, messy conglomerate deciding it would be worth more as two focused companies than one diversified one.

The roots run deep. Pieces of what would become Origin stretch back into the 19th century. Boral itself began in 1946 as Bitumen and Oil Refineries (Australia) Ltd. And by the time the split happened, a large chunk of the energy business traced to SAGASCO Holdings Limited—an Adelaide-based petroleum exploration, production, and gas retailing company whose gas retailing lineage dated back to the 1850s. That made it one of Australia’s oldest continuously trading businesses, and it also meant Origin wasn’t being invented from scratch. It was being assembled.

That heritage matters because it explains Origin’s DNA. This wasn’t a clean-sheet company designed around a single product. It was a collection of real operating assets—gas distribution networks, exploration acreage, and retail customer relationships—each with its own history and way of doing things. Origin began life less like a startup and more like a carefully selected set of industrial building blocks, bolted together and pointed at a clearer future.

In February 2000, Boral executed the demerger. The mechanics were tidy, even if the corporate choreography was complex: the existing listed Boral kept the energy businesses and stayed on the ASX, but changed its name from Boral Limited to Origin Energy Limited. Meanwhile, the building products and construction materials businesses were transferred into Blue Circle Southern Cement Limited, a wholly owned subsidiary. Boral shareholders received shares in that entity via a return of capital, and Blue Circle was then renamed Boral Limited on February 18, 2000—before listing separately on the ASX on February 21.

Strategically, the logic was almost inevitable. Investors were falling out of love with conglomerates and asking for “pure-play” exposure. And energy and building materials couldn’t have been more different businesses: different capital cycles, different regulation, different risks, different growth paths. As a standalone energy company, Origin could pursue acquisitions and invest for the long term in ways that would have been awkward—or even impossible—inside a diversified industrial group. Management focus sharpened. Capital allocation got cleaner. And the market could value the energy story on its own terms.

Importantly, this wasn’t an overnight pivot. Boral’s energy interests had been growing through acquisitions for years and were consolidated into a subsidiary, Boral Energy, in 1995. More acquisitions followed before the demerger finally separated the energy business from the rest.

There may not have been “founders” in the Silicon Valley sense, but there was a defining early leader. Grant King became Origin’s first CEO and Managing Director and would hold the role for sixteen years. He was the steady hand through Origin’s formative period—building around existing gas assets, power generation, and a growing customer base—and he would later be central to the coal seam gas push and the APLNG bet that came to define the modern company.

King retired in October 2016 after those sixteen years in charge. He remained involved as a Director of the Origin Foundation from its inception, and his post-Origin roles—Chairman of HSBC Australia, Sydney Water, and Transgrid, plus other clean energy and advisory positions—underscore the reputation he built as an operator in energy markets and infrastructure.

And here’s the key takeaway: the “demerger playbook” Origin ran is one of the cleanest examples of why these moves can be so powerful. Separate two businesses with fundamentally different strategic needs, and you often unlock value through sharper focus, better-aligned investment decisions, and clearer investor understanding. Origin’s trajectory after the split—growing from a roughly $1 billion revenue business into a company generating more than $17 billion by 2025—became the proof point. Not because demergers guarantee success, but because they give a company permission to become what it actually is.

Building the Retail Empire: The 2000s Acquisition Spree

If the demerger was Origin’s birth certificate, the decade that followed was its growth spurt. The newly independent company didn’t waste time finding its identity. It went looking for scale—fast—because in a deregulating energy market, size isn’t vanity. It’s leverage. It’s cost advantage. And it’s the right to matter.

The first big move was to push beyond gas and become a true dual-fuel retailer. Between 2001 and 2002, Origin acquired a Victorian electricity retailer licence from distributors Powercor and CitiPower. On paper, that sounds like a regulatory footnote. In reality, it was an entry ticket into the future. Customers didn’t want separate companies for gas and electricity forever. Convenience was becoming a differentiator, and Origin wanted to be the one-stop shop.

Then came the kind of investment that rarely gets celebrated but quietly changes the chessboard. In 2004, the SEAGas pipeline was completed, linking the Victorian and South Australian gas markets. That connection mattered because it gave Origin flexibility: the ability to move gas to where it was needed, smooth out constraints between states, and serve a growing footprint with a more efficient portfolio.

Origin didn’t just expand across Australia—it also reached across the Tasman. During this period it obtained a 50% interest in the Kupe Gas Field and Edison Mission Energy’s 51.4% interest in New Zealand’s Contact Energy. The Contact stake, in particular, gave Origin exposure to a hydro-dominated market and operating experience in a different regulatory environment—useful perspective for a company learning how political and technical electricity systems can be.

But the deals that truly made Origin a national powerhouse were in Queensland and New South Wales.

On 27 November 2006, the Queensland Government announced the sale of Sun Retail, the former retailing arm of Energex, to Origin for $1.202 billion. With it came around 800,000 new Queensland customer accounts—and instant credibility in the Sunshine State. It also made Origin a leading retailer of green energy, with around 500,000 green energy customer accounts in the mix.

Then came the scale-defining leap. Origin became Australia’s largest energy company by acquiring 1.6 million customer accounts from Country Energy and Integral Energy in New South Wales. This wasn’t just about bragging rights. It was about density: more customers concentrated in key markets meant lower servicing costs per account, more efficient marketing, and more opportunities to sell additional products over time. With that deal, Origin moved from being a big player to being the dominant retailer in Australia’s most important states.

As the customer book ballooned, Origin also built out the supply side. Its portfolio of natural gas-fired generators grew as it acquired Uranquinty Power Station and approved construction of Mortlake Power Station. Gas generation fit the strategy: it was more flexible than coal, lower emissions, and—crucially—it helped hedge the retail business against swings in wholesale electricity prices.

And in 2010, at its 10th anniversary, Origin did something that signaled it had started thinking like an institution, not a scrappy roll-up. It invested $50 million to establish the Origin Energy Foundation. Yes, it was philanthropy. But it was also relationship-building—an acknowledgment that when you serve millions of households and build big energy infrastructure, your social license matters. That would become even more important once coal seam gas and coal plant closures moved from boardroom topics to front-page fights.

Underneath all of this was a coherent strategic idea: vertical integration across the energy value chain—from exploration and production, through generation, all the way to retail and customer service. Control more links, capture more margin, and balance risks across the portfolio.

By the end of the 2000s, Origin had proven it could buy, integrate, and scale. It had also boxed itself into a different kind of responsibility. When you have millions of customers depending on you, energy stops being just a business strategy. It becomes political. And that reality would later collide head-on with Origin’s biggest legacy assets—and its biggest transition promises.

The APLNG Mega-Bet: Origin's $28 Billion Gamble on LNG

Every company has a moment where strategy stops being a slide deck and becomes destiny. For Origin, that moment arrived in October 2008, when it decided coal seam gas in Queensland could be turned into LNG and sold into Asia—and that it was worth building an export machine to do it.

Origin and ConocoPhillips formed Australia Pacific LNG as a 50:50 joint venture in October 2008. The timing was almost absurdly bold. Lehman Brothers had collapsed weeks earlier, credit markets were seizing up, and a global demand slump was setting in. But the partners were looking past the panic and toward the longer arc: fast-growing Asian demand, and Australia’s giant unconventional gas resource base.

The result was APLNG: a US$28 billion project backed by Origin, ConocoPhillips, and later China’s Sinopec. It would go on to be the largest coal seam gas-to-LNG project in Australia, and the largest project financing of its kind to close.

To grasp the scale, think end-to-end system, not just an LNG plant. APLNG meant developing gas fields in Queensland’s Surat and Bowen Basins, building a 530-kilometre transmission pipeline, and then constructing an LNG facility on Curtis Island. This wasn’t a single asset—it was an entire new export supply chain.

Then came the partner that made the economics click. In August 2011, Sinopec—China’s second-largest energy company—entered the project, described as a “natural consequence” given how much of the LNG was expected to head to China. Sinopec bought 15% initially, then lifted that to 25% the following January. That diluted ConocoPhillips and Origin down to 37.5% each, but it also helped de-risk the project by bringing both capital and a major customer relationship into the ownership group.

By mid-2011, the project moved from ambition to commitment. The sponsors made a final investment decision on the first phase in July 2011, and the project reached financial close on 23 May. APLNG wasn’t just an Origin story anymore; it was becoming a pillar of Australia’s export economy and a meaningful component of the energy import plans of major Asian buyers.

The financing mattered almost as much as the engineering. APLNG’s US$8.5 billion project financing was fully non-recourse and organised into multiple tranches, including export credit agency sub-facilities and a commercial lender sub-facility. The key point: non-recourse financing meant lenders could not go after the parent companies’ other assets if the project went sideways. Origin and its partners still had huge equity at risk, but the structure prevented an LNG mega-project from automatically becoming a company-killer.

The commercial backbone was equally deliberate: long-term offtake. APLNG signed two export agreements covering most of its output—7.6 MTPA to Sinopec and 1 MTPA to Kansai Electric—each for 20 years. With revenues effectively pre-sold under oil-linked pricing, the joint venture could justify the enormous up-front build.

Construction ran through the mid-2010s. In late 2015, APLNG hit first production, and on 9 January 2016 it shipped its first LNG cargo—nearly five years after the major investment decision.

From there, performance turned the project from “big bet” into “operating engine.” APLNG became the largest gas producer, domestic gas supplier, and LNG exporter on Australia’s east coast, producing coalbed methane from the Bowen and Surat basins. The Curtis Island liquefaction facility—operated by ConocoPhillips—uses ConocoPhillips Optimized Cascade Technology, which is cited as a contributor to APLNG’s low-intensity greenhouse gas profile and positions it among the lowest emissions intensity LNG plants globally.

The system scaled, and it stayed reliable. APLNG has shipped more than a thousand LNG cargoes since it began operations in 2016—proof, more than any press release, that this sprawling chain of wells, pipelines, and liquefaction trains became a repeatable industrial process.

Over time, ownership shifted again. In February 2022, ConocoPhillips strengthened its commitment by purchasing an additional 10% interest from Origin for $1.645 billion. After that transaction, Australia Pacific LNG became owned by ConocoPhillips (47.5%), Origin (27.5%) and Sinopec (25%).

The division of labour followed what each party did best. Origin operates the upstream gas fields and the main transmission pipeline. ConocoPhillips is responsible for the two-train LNG facility on Curtis Island and the LNG export sales business.

For Origin, APLNG is the kind of asset Hamilton Helmer would call a “cornered resource”: scarce, hard to replicate, and protected by long-dated contracts. It has also been a major source of cash. In fiscal 2024, Origin received $1,384 million in cash distributions from APLNG, or $1,367 million net of Origin oil hedging.

But the same project that gave Origin a cash machine also tightened the company’s strategic constraints. APLNG tied Origin to fossil fuel production deep into the future, making its climate commitments harder to execute cleanly. And it concentrated a meaningful share of earnings in one enormous asset—leaving Origin more exposed to commodity price swings and the inevitable risks that come with running a complex, high-stakes piece of infrastructure.

The Eraring Conundrum: Australia's Largest Coal Plant and the Transition Dilemma

If APLNG is Origin’s long-duration bet on gas and exports, Eraring is the company’s day-to-day reality check: the single biggest coal plant in the country, essential to keeping New South Wales powered, and a symbol of the very thing the transition is trying to leave behind.

Origin bought Eraring in 2013, acquiring it from the NSW Government. At the time, it was a logical move. Eraring’s huge, steady baseload output complemented Origin’s gas-fired generation and acted as a hedge for the retail business when wholesale power prices moved around.

Eraring sits on the shores of Lake Macquarie. It was fully commissioned in 1984, with four black-coal units. At roughly 2.9 gigawatts of capacity, it’s Australia’s largest power station, supplying about a quarter of New South Wales’ power needs. It’s also among the country’s biggest sources of greenhouse gas emissions—an unavoidable fact that hangs over every conversation about its future.

For years, Eraring was a profit engine. Coal plants like this are built to run hard and run often, and when they do, they can capture the gap between low fuel costs and the wholesale electricity price. But as more solar and wind entered the system, that math started to change. Daytime solar pushed prices down right when coal plants are least able to ramp flexibly. Meanwhile, keeping an ageing station reliable grew more expensive.

Before Calabria’s 2022 “bomb,” Origin had already been signalling that early closure was on the table. In May the year before, Origin said it would start the process of closing Eraring in 2030, with full decommissioning by 2032. The message was clear: profitability was being squeezed by the rise of daytime solar generation, and the plant’s inflexibility made it harder to compete in a grid that was becoming more volatile and more renewable-heavy.

Then February 2022 turned the simmering debate into a hard deadline. Origin told the Australian Energy Market Operator it proposed to close Eraring in August 2025—seven years earlier than previously planned. The company framed it as an accelerated exit from coal, driven by economics and the rapid transformation of the National Electricity Market.

And the numbers in that period supported the story Origin was telling. Origin’s half-year results showed a sharp drop in gross profits in its electricity business: down to $222 million for the half-year ending December 2021, from $503 million a year earlier. Calabria pointed to the same twin forces reshaping every thermal generator’s business case: low-cost renewables compressing prices, and improving battery economics changing what “firming” could look like.

But Eraring isn’t just an Origin asset. It’s a system asset. And the NSW Government wasn’t prepared to take a major chunk of dispatchable capacity off the board before replacement supply was clearly in place. The result was a deal to keep Eraring running longer. Origin agreed, at the government’s request, to operate the site until August 2027.

NSW also offered to underwrite the extension, with support of up to $450 million. Origin has said the plant has been so profitable it hasn’t drawn on that support—one of the great ironies of the transition: the asset everyone agrees must close can, at the same time, be throwing off substantial cash.

Even with an “extended” date, the closure timeline has stayed murky. Comments from the company have fuelled speculation that Eraring may not actually close in August 2027 as currently advised to AEMO. The plant is generating profits, and Origin has not replaced its capacity with new wind and solar before then. Origin has also said there are “lots of scenarios” where Eraring could be required beyond its current closure date.

That gap—between the rhetoric of transition and the reality of grid operations—has given critics an opening. As one line puts it: “Whilst Origin Energy executives tout their climate action plan, the reality is that the company does not have a single operational solar or wind farm.”

Origin’s answer, at least on the Eraring site, is storage. To replace Eraring’s role in the system, Origin is developing one of the world’s largest battery projects at the power station location. All four stages of the Eraring BESS are now in construction or commissioning. When complete, the project is planned to reach 700 MW of power capacity and 3,160 MWh of storage, making it the largest battery development in the southern hemisphere. Stage one and stage three together provide 460 MW with a four-hour dispatch duration and are scheduled to come online in early 2026.

Origin has progressively expanded the project. It approved a third stage, adding 700 MWh to the first stage already underway, and with the second stage also under construction, the combined battery was described as reaching 700 MW / 2,800 MWh. Then came a fourth stage—an $80 million investment—designed to lift the second phase’s storage duration to nearly six hours, bringing the total project to 700 MW and 3,160 MWh.

This is what the stranded-asset problem looks like in real time. A plant can have years of technical life left and still be on borrowed economic time. Governments can step in to delay closures for reliability or price reasons. And the transition doesn’t arrive all at once—it arrives unevenly, with legacy assets like Eraring stuck in the middle, asked to be both profitable and temporary, indispensable and unwanted, all at the same time.

The Takeover Battle: AustralianSuper Versus Brookfield

The Brookfield takeover saga wasn’t just corporate theatre. It quickly turned into a proxy war over a much bigger question: who should own, fund, and control Australia’s energy transition—and on what time horizon. When it ended, it had become one of the country’s biggest and longest takeover battles, and it reset expectations for what private capital can, and can’t, force through in the power sector.

In November 2022, Origin received a takeover offer from a consortium led by Brookfield Asset Management alongside EIG Global Energy Partners, valuing the company at A$18 billion. The pitch had a clean split-brain logic. Brookfield would take Origin’s energy markets business and pour money into renewables. EIG’s MidOcean Energy would take the integrated gas business, including Origin’s stake in APLNG.

The consortium said it would invest up to A$30 billion over a decade to accelerate Origin’s shift from fossil fuels to cleaner energy. The headline promise was simple and massive: build up to 14 gigawatts of new renewable generation and storage by 2033.

By March 2023, Origin’s board agreed to the deal. In October 2023, it cleared another major hurdle when it was approved by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. From the outside, it looked like momentum was building toward the kind of clean outcome markets like: a definitive owner, a big capital commitment, and a transition narrative you could write into a single sentence.

Then came the problem: Origin’s register.

AustralianSuper—Australia’s largest pension fund and Origin’s biggest shareholder, with a stake of more than 17%—was openly unconvinced. It argued the consortium’s offer materially undervalued Origin’s long-term prospects. As the bidding progressed, Brookfield and EIG put A$8.91 per share on the table, lifted it multiple times, and eventually landed at $9.53. AustralianSuper didn’t budge.

The showdown arrived at the scheme meeting in Sydney. The vote was decisive in the most frustrating way possible: strong support, but not enough. 68.92% of votes cast backed the takeover—well short of the 75% threshold required. A deal can feel “won” at two-thirds. Legally, it’s still a loss.

AustralianSuper’s statement made the philosophy plain: “AustralianSuper believes Origin has a highly strategic portfolio of assets to participate in, and for members to benefit from, the energy transition. We have never wavered in our belief that the value and future value of Origin is better in the hands of members and other shareholders rather than a private equity consortium seeking to make a quick return based on the proposed scheme terms.”

With that, the A$20 billion “best and final” bid was dead, ending a 13-month corporate drama. Origin Chairman Scott Perkins struck the reset tone: the utility would “focus on delivering on our strategic priorities, accelerating investment in cleaner energy and storage and pursuing our ambition to lead the energy transition.”

AustralianSuper also made a pointed follow-on promise: it reiterated that it was open to providing capital to support Origin’s transition. In other words, it wasn’t just saying no. It was saying: stay public, stay independent, and we’ll back you—on the longer timeline this job actually requires.

That’s what made the outcome so consequential. It showed how Australia’s superannuation giants, with decades-long horizons and enormous pools of capital, can exert real influence over strategic direction—not just by buying shares, but by blocking exits. It also exposed a mismatch in playbooks: the typical private equity model of acquiring, reshaping, and exiting within a handful of years is a tough fit for assets that need patient funding, regulatory stamina, and multi-decade buildouts.

After the vote, Perkins emphasized what the process had clarified: “While the scheme will not proceed, it was supported by many Origin shareholders. Importantly, this process has made clear the confidence all shareholders have in Origin’s business, assets and people, and its strategic positioning for the energy transition.”

And that became the new mandate. No buyout. No grand handoff. Origin would have to do the hard part itself.

Leadership, Strategy, and the Modern Era

When Grant King handed the CEO role to Frank Calabria in October 2016, it wasn’t just a leadership change. It was a shift in posture.

King’s era had been defined by building: scale in retail, big positions in generation, and the company-shaping APLNG bet. Calabria inherited the other side of that story: a business still absorbing APLNG’s enormous capital spend, carrying significant debt, and needing to prove it could translate giant assets into durable returns. The job now wasn’t expansion at any cost. It was simplification, discipline, and execution.

Calabria was an insider with a finance brain and a retailer’s instincts. He’d joined Origin in 2001 as CFO, and in 2009 he became CEO of the Energy Markets business—right as competition intensified and the grid began its uneven tilt toward a lower-carbon future. When he stepped up to the top role, he made his priorities plain: pay down roughly $9 billion of debt and be willing to sell assets that no longer fit.

The first moves were classic “clean up the balance sheet” decisions—but with real strategic intent. In 2017, Origin sold Lattice Energy and its conventional upstream oil and gas business to Beach Energy for $1,585 million. It wasn’t just a cash grab; it was a statement that Origin didn’t need every upstream asset to win. It needed the right ones, and it needed the flexibility that comes with a lower debt load.

Around the same period, Origin also divested its 53.09% shareholding in New Zealand’s Contact Energy. That sale continued the portfolio simplification theme: step back from non-core international exposure and focus capital and management attention on the Australian opportunity set.

But Calabria’s most distinctive strategic swing wasn’t a divestment. It was a technology bet.

In May 2020, Origin bought a 20% stake in UK-based Octopus Energy and licensed its Kraken customer platform—framing it as a way to transform retail operations, improve customer experience, and lower cost to serve. The partnership was widely reported as a roughly $500 million deal (about $507 million), aimed at streamlining and automating millions of customer interactions.

Origin said the shift to Kraken would deliver cost savings quickly, projecting immediate savings of $70–$80 million in 2022, growing to as much as $150 million annually within five years. That’s the kind of claim companies love to make—and then struggle to deliver. What made this one different is that Origin actually did the hardest part: it executed the migration.

In May 2023, Origin completed the move of its roughly 4.2 million retail customers to Kraken in just 2.5 years—one of the largest customer platform migrations in Australian history. In a sector where billing system problems can become front-page scandals, “it worked” is a meaningful achievement.

Origin later increased its stake in Octopus again, announcing a £280 million investment (about $530 million) to lift its interest by around 3 percentage points to roughly 23%, as Octopus continued to grow. Origin’s ownership has since been cited at about 22.7%.

As Octopus scaled, so did the narrative value of that stake. The Octopus retail business now has around 14 million customers, and Kraken’s platform is used across a base reported at 74 million customers globally. Analysts have argued that if Kraken were ever demerged from Octopus, it could unlock significant valuation upside for Origin. On the most optimistic estimates, Origin’s roughly 23% stake in Octopus and a potential stand-alone Kraken could be worth as much as $6.6 billion.

Alongside the portfolio and platform changes, Origin positioned itself publicly as a transition leader. It joined the We Mean Business global climate action coalition—the first company in Australia and the first energy company in the world to commit to seven targets aimed at driving emissions reduction across the business.

And despite the push into software and storage, Origin never stopped caring about what built its dominance in the first place: retail scale. In November 2025, it entered into an agreement to acquire the retail energy business of Energy Locals, adding further customer accounts to an already massive base.

At the same time, Origin showed it could walk away from ideas that didn’t pencil out. It announced a strategic shift away from the hydrogen market, citing “uncertainty around the pace and timing of development of the hydrogen market,” and withdrew from the development of the Hunter Valley Hydrogen Hub. Calabria said the company would refocus on renewable generation and energy storage developments—areas closer to the grid’s immediate needs and, crucially, nearer-term economics.

By 2025, the business was putting up strong results. Origin reported statutory profit for the full year ended 30 June 2025 of $1,481 million, up from $1,397 million the year before. Underlying profit rose to $1,490 million, from $1,183 million, driven primarily by a lower income tax expense as dividends from APLNG switched from partially to fully franked. Customer accounts grew by 57,000 to 4.7 million, with growth primarily across electricity, Home Assist, and broadband.

If King’s era was about building the machine, Calabria’s has been about making it run cleaner—and making sure it can fund its next version without breaking under the weight of the last one.

Playbook: Business and Investing Lessons

If you zoom out from the headlines—LNG mega-projects, coal closures, takeover drama—Origin’s first 25 years boil down to a handful of repeatable patterns. The kind executives borrow, and investors try to spot early.

The Demerger Playbook: Origin’s emergence from Boral is the clean case study for why demergers happen. Energy and building materials looked like one company on a corporate chart, but they wanted different capital, different risk tolerance, and different timelines. Once separated, Origin could pursue acquisitions and long-cycle infrastructure investments that would have been awkward—if not impossible—inside a diversified industrial group. The broader lesson is simple: when a business’s capital needs and strategic direction stop matching the parent’s, separation often makes both businesses stronger and easier to value.

Vertical Integration in Utilities: Origin built an integrated model—upstream gas, generation, and a huge retail book—and it worked. Integration lets you hedge wholesale price swings, keep margins across multiple links in the chain, and build deep operating expertise. But it also creates a new kind of problem: parts of the machine can want opposite things at the same time. Eraring is the perfect example: it can be highly profitable, system-critical, and completely misaligned with the company’s decarbonisation story. Vertical integration can be a moat—but it can also be a management stress test.

The Mega-Project Risk: APLNG shows what “betting the company” looks like in infrastructure. What made the bet survivable wasn’t bravado; it was structure. Origin shared the load with partners that brought complementary capabilities, locked in long-term offtake before the final investment decision, and used non-recourse project financing to limit spillover risk to the rest of the company. Those 20-year contracts can dampen commodity price risk and stabilize cash flows, but they also extend exposure to fossil-fuel emissions intensity deep into the future. You can de-risk a project financially while still locking in strategic constraints.

Retail Scale Economics: The acquisition spree of the 2000s built Origin’s most durable advantage: scale at the customer level. With about 4.7 million customer accounts, the economics compound—lower servicing costs per customer, more efficient marketing, and a stronger ability to fund technology upgrades. Kraken adds another layer, shrinking cost-to-serve dramatically versus legacy retail systems. In energy retail, being big isn’t just being big. It’s being able to keep investing when smaller players can’t.

Activist Shareholders and Energy Transition: The Brookfield saga underlined a modern reality: when your largest shareholder has a decades-long time horizon, they can be willing to block a near-term premium in favor of long-term optionality. AustralianSuper didn’t just vote down a deal; it effectively argued that the transition itself is an asset—and that patient capital should own it. As super funds and sovereign wealth funds lean into the transition as a multi-decade buildout, the takeover playbook in utilities changes. “Just pay up and win” isn’t always enough.

Stranded Asset Management: Eraring is the stranded-asset problem in motion. Origin tried to bring the closure forward, then extended operations under government pressure, and has since left the door open to further delays. The bigger lesson is that “stranded” isn’t a yes-or-no label. It’s a spectrum shaped by regulation, reliability, commodity prices, and whether replacement capacity actually shows up on time. In the transition, the hardest assets aren’t the ones you want to close. They’re the ones the system can’t yet afford to lose.

Strategic Analysis: Porter's Five Forces and Hamilton's 7 Powers

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: Low-Medium

Energy retail has gotten easier to enter with deregulation, but it’s still hard to enter at scale. Building or buying generation takes real capital, and developing upstream gas is even more expensive and time-consuming. The real moat, though, is unit economics: winning a customer costs money whether you’re tiny or huge, but only a big retailer can spread fixed platform costs across millions of accounts. At the same time, rooftop solar and home batteries are lowering the barrier on the generation side, letting new players compete at the grid edge without ever building a traditional power station.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Medium

Origin’s upstream exposure through APLNG gives it a meaningful hedge against gas supplier leverage. Coal is a different story: the pool of suppliers that can meet a plant like Eraring’s needs has historically been limited, which gives those suppliers negotiating power. On the renewables side, equipment is moving in the opposite direction—solar panels, inverters, and batteries are increasingly commoditized, with fierce competition among global manufacturers pushing costs down and reducing supplier leverage.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Medium-High

Retail electricity and gas customers can shop around more easily than ever, with comparison sites making price transparency the default. Layer on government intervention—default offers, price caps—and retailers have less room to expand margins. Large industrial customers push even harder, using their scale to negotiate multi-year contracts with thin margins. The net effect is straightforward: power shifts to the buyer, and operational efficiency becomes a competitive weapon.

Threat of Substitutes: High

This is the existential pressure on the classic utility model. Rooftop solar, home batteries, electric vehicles (especially as vehicle-to-grid capabilities mature), and community energy schemes all reduce a household’s dependence on grid-supplied electricity. As costs fall and performance improves, more energy is generated and stored “behind the meter,” which structurally reduces the volume that flows through a retailer’s customer base.

Industry Rivalry: High

Rivalry in Australian energy retail is relentless. AGL, EnergyAustralia, and a long tail of smaller retailers fight over a market that isn’t growing much, turning customer acquisition into a zero-sum contest. When switching is easy and pricing is visible, differentiation is hard—so marketing intensity rises, churn becomes expensive, and the battle often comes down to who can operate at the lowest cost-to-serve.

Hamilton's 7 Powers

Scale Economies: Strong

With around 4.7 million customer accounts, Origin’s scale is a real advantage. Big fixed costs—technology platforms, compliance, call centers, brand, and marketing—get amortized across a larger base than most competitors can match. Kraken strengthens this further: once the platform is in place, cost-to-serve improvements compound most effectively at high volume.

Network Effects: Weak but Evolving

The traditional utility model doesn’t naturally generate network effects. But programs like virtual power plants and community batteries can create modest “the more participants, the better the system works” dynamics. Kraken may also develop stronger network effects globally as more utilities adopt it—though Origin captures that upside indirectly through its equity stake rather than directly through its Australian retail base.

Counter-Positioning: Moderate

Origin’s combination of retail, generation, and upstream gas is a counter-position to pure-play retailers: it can hedge wholesale volatility and capture margin across the chain. But the same integration creates complexity in the transition. Pure-play renewables developers don’t have to manage coal closures, gas exposures, or legacy operating constraints. Whether integration keeps paying off depends on how quickly the transition accelerates—and how well Origin can keep the parts moving in the same direction.

Switching Costs: Low-Moderate

For most households, switching energy retailers is easy and fast, which keeps switching costs low. Origin can raise stickiness through bundling—electricity plus gas plus broadband plus solar—making the relationship harder to unwind. In the business segment, switching costs can be higher: large customers often lock into multi-year contracts and integrated service arrangements that are more painful to replace.

Branding: Moderate

Origin’s brand is widely recognized, and the Kraken migration has generally improved customer experience and satisfaction. Still, for many customers, energy is a commodity and price dominates. Branding matters more at the edges—solar, EV charging, and service-heavy products—where trust and execution influence buying decisions beyond cents per kilowatt-hour.

Cornered Resource: Strong

APLNG is a classic cornered resource: a scarce, hard-to-replicate position as the largest producer of natural gas in eastern Australia, supported by long-term LNG contracts into Asia. Eraring’s site and grid connection are also scarce resources—especially now that the site is being repurposed as the location for Australia’s largest battery development. Competitors can build projects, but they can’t easily recreate these specific assets.

Process Power: Moderate

Origin has demonstrated strong operational capability across complex assets and systems—running large-scale generation, operating upstream gas and pipelines, and migrating millions of retail customers onto Kraken. APLNG’s reliability and ability to operate above nameplate capacity reinforce that operational competence. The limitation is durability: these are hard-earned advantages, but they’re not trade secrets, and over time competitors can learn, invest, and close the gap.

Bull and Bear Case

Bull Case

Origin’s bull case is, essentially, that it already owns the hard parts of the transition: the customers, the grid access, and the cash flow to fund what comes next.

Energy Transition Leader with Positioning Advantages

Origin has a set of positioning advantages that are genuinely difficult to replicate. The Eraring site isn’t just a coal plant you eventually shut down; it’s a major piece of grid-connected industrial infrastructure with an experienced workforce, now being repurposed around a massive battery project. On the demand side, Origin’s roughly 4.7 million customer accounts give it recurring revenue and a built-in distribution channel for new products like rooftop solar, home batteries, and electric vehicle charging. And critically, management has shown it can execute complicated transformations at scale—most notably with the Kraken migration.

APLNG Cash Machine Funds the Transition

APLNG is the funding engine. Long-term LNG contracts can provide steady cash flows that let Origin invest in storage and renewables without leaning too hard on the balance sheet. Since inception, APLNG has shipped 3,700 petajoules to international customers and supplied another 2,100 petajoules to the domestic market. It has also built a reputation for high reliability and relatively low emissions intensity for an LNG operation. In the bull narrative, that combination—durable cash generation plus operational consistency—buys Origin the time and capital runway the transition demands.

Octopus Provides Hidden Value and Global Technology Access

Then there’s the optionality in Octopus Energy. Origin’s roughly 23% stake gives it exposure to a fast-growing global retailer and, more importantly, the Kraken platform—now reported as serving 74 million customers globally. Octopus’s retail business is at around 14 million customers. If Kraken were ever separated in a de-merger, that could unlock significant value for Origin shareholders. Even without any corporate event, the partnership gives Origin ongoing access to leading retail technology—an edge in a market where cost-to-serve and customer experience often decide who wins.

AustralianSuper Alignment Enables Patient Capital

Ownership matters in a transition that takes decades. With AustralianSuper as the largest shareholder, Origin has a major investor that is explicitly oriented toward long-term value creation and has indicated a willingness to support the capital needs of the transition. In the best case, that reduces pressure for short-term financial engineering and gives management more room to execute a multi-year strategy.

Battery and Storage Pipeline Delivers Transition Credibility

Finally, Origin can point to real projects, not just targets. It has committed to developing or contracting 1.7 GW in owned and tolled large-scale battery projects, including Eraring, Mortlake Power Station in Victoria, the Summerfield battery storage project in South Australia, and the Supernode battery in Queensland. The Eraring battery alone—planned at 700 MW / 3,160 MWh when complete—would be among the world’s largest. In the bull case, this pipeline is what turns “transition talk” into transition credibility.

Bear Case

The bear case is that Origin is trying to run two races at once: extracting value from legacy fossil assets while building a new portfolio fast enough to replace them—inside one of the world’s most politically charged power markets.

Stranded Asset Risk Remains Material

Eraring is profitable today, but the economics of coal can turn quickly. If renewables deployment accelerates and wholesale prices fall—especially during the hours coal plants are least flexible—the plant’s value could deteriorate faster than expected, bringing the risk of accelerated write-downs. And the company’s openness to scenarios where Eraring runs beyond 2027 cuts both ways: it may help system reliability, but it also extends emissions, invites political scrutiny, and can complicate the investment story for new renewables meant to replace it.

Transition Execution Risk in a Competitive Market

Execution is the entire ballgame, and it’s a crowded field. Origin is trying to build into renewables and storage while facing the criticism captured in the blunt line: “Whilst Origin Energy executives tout their climate action plan, the reality is that the company does not have a single operational solar or wind farm.” Competitors with cleaner portfolios start from an easier place, with fewer legacy constraints. Meanwhile, renewables development has become intensely competitive, with lots of capital chasing projects and compressing returns.

APLNG Concentration Creates Commodity Vulnerability

APLNG has been a strength, but concentration cuts both ways. Heavy dependence on one asset for earnings exposes Origin to LNG price swings—particularly over time as long-term contracts roll off and more volume becomes spot-exposed. Operational disruptions are unlikely but would be meaningful if they occurred. And as global decarbonisation policies tighten, LNG assets risk being re-rated by the market, even if they keep generating cash.

Retail Margin Pressure from Competition and Regulation

Retail is large, but it’s not a free lunch. Government default offers and price caps limit pricing power, while aggressive competition forces marketing spend just to hold share. Rooftop solar and behind-the-meter tech can reduce grid volumes, even as retailers still bear the cost of serving and supporting those customers. The concern is structural: the retail economics may be getting worse over time, not better.

Octopus Valuation Uncertainty

Octopus may be valuable, but it’s not liquid. Origin’s stake is in a private company, which limits easy monetisation. Octopus has faced competitive pressure and has incurred losses while investing for growth. And while a Kraken de-merger could unlock value, that outcome—and its timing—is speculative. In the bear case, investors can’t count on optionality to bail out the core transition risk.

Key Performance Indicators for Monitoring

If you’re tracking Origin from here, you don’t need a dozen dashboards. You need a few signals that tell you whether the machine is compounding—or quietly weakening.

Customer Account Growth and Churn

Origin’s customer accounts are the flywheel: they’re the recurring revenue base, and they’re the channel for selling more than just electricity and gas. In the first half of FY25, customer accounts increased by 57,000 to 4.7 million. If that number keeps climbing, it’s evidence Origin can still win in a brutally competitive retail market. If it starts slipping, it’s often the earliest warning that competitors are taking share, or that price and service are no longer landing.

Churn matters just as much. In a market where switching is easy, churn is the real-time read on whether customers think they can do better elsewhere—and whether Origin’s platform and product bundle are actually creating stickiness.

APLNG Distributions as a Percentage of Origin's Cash Flow

APLNG is not just a “good asset.” It’s the funding source that makes everything else possible: batteries, renewables, and returns to shareholders. Origin received $797 million in fully franked dividends from Australia Pacific LNG, plus a further $335 million dividend received on 3 July relating to cash generated in FY25.

The key isn’t the exact dollar amount in any one period—it’s the dependency. Track APLNG distributions as a share of Origin’s overall cash flow. If APLNG stays strong, Origin has room to invest and still pay. If those contributions fade without something else rising to replace them, the whole transition plan gets tighter, faster.

Renewable and Storage Capacity Under Development

Origin’s credibility on the transition is ultimately built in steel, concrete, and grid connections. The headline project is Eraring’s battery: across all four stages, it’s now planned at 700 MW / 3,160 MWh.

What matters for investors is whether projects move from “announced” to “commissioned.” Watch what’s actually under construction, what hits commissioning on schedule, and how capital deployment tracks against plans. Delays and cost blowouts are the classic failure mode in energy buildouts. Consistent delivery is how Origin turns a transition narrative into a transition track record.

Origin sits at the kind of crossroads that feels uniquely Australian, but is actually playing out across utilities worldwide. The company has real strengths: the country’s largest retail customer base, a globally significant LNG position through APLNG, the Eraring site as a piece of scarce grid-connected infrastructure, and a meaningful stake in Octopus and Kraken.

But those advantages come with built-in contradictions. Fossil cash flows funding decarbonisation. Scale that creates resilience, but can also slow movement. Long-term contracts that provide stability, in a market being reshaped by solar, batteries, and policy.

From here, the story tightens to one question: can Origin execute a transition that keeps reliability and shareholder returns intact, while building the next portfolio fast enough to matter? AustralianSuper has effectively said yes—and that the long game will be worth more than the private equity bid. The next decade is where that bet gets marked to reality.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music