NEXTDC: Australia's Digital Infrastructure Titan

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

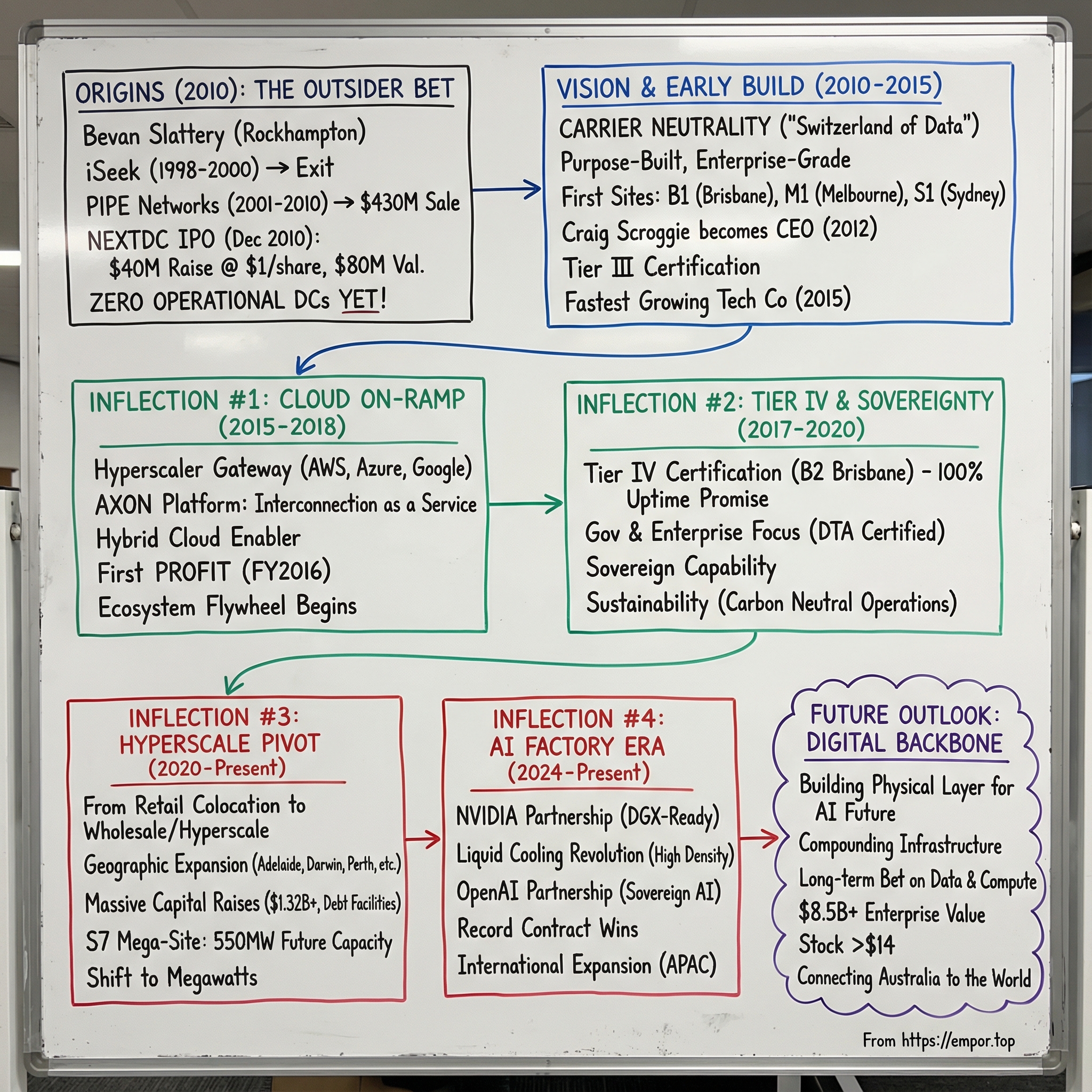

Picture this: December 2010, the Australian Securities Exchange. A Brisbane-headquartered startup most people have never heard of starts trading under the ticker NXT. It’s raised $40 million at $1 a share, valuing the company at about $80 million.

There’s just one catch: it doesn’t have a single operational data centre yet.

Its founder is 38 years old, from regional Queensland, and he’s fresh off selling his previous company only months earlier. He’s placing a big, capital-intensive bet on an idea that, at the time, sounds almost too unsexy to matter: Australia’s digital future is going to depend on purpose-built, enterprise-grade facilities where companies can store and move their most critical data. And crucially, those facilities need to be carrier-neutral—the Switzerland of connectivity—so everyone can plug in.

Fast forward to today, and that early IPO has become an $8.5+ billion enterprise. The stock that opened at $1 now trades above $14. Along the way, NEXTDC has grown into Australia’s largest listed developer and operator of data centres, still headquartered in Brisbane.

So the question at the heart of this episode is simple: how did a serial entrepreneur from Rockhampton—about 600 kilometres north of Brisbane—turn a vision for “boring” infrastructure into one of Australia’s standout tech growth stories? And why did NEXTDC end up as the ultimate picks-and-shovels play for two massive waves: first cloud computing, and now AI?

CEO Craig Scroggie captured the scale of the ambition recently on LinkedIn, talking about the company’s new S7 development: “This AUD$7b+ (US$4.64bn+) development will provide sovereign compute capability for government, finance, defence, research and enterprise.” That’s the kind of project that can redefine what “big” even means in this industry.

We’re going to explore four themes.

First: serial entrepreneurship. NEXTDC makes a lot more sense when you understand its founder’s pattern—and why he keeps building infrastructure businesses when plenty of people would have retired.

Second: the cloud megatrend. NEXTDC didn’t just ride cloud adoption; it positioned itself as the on-ramp—private, direct access into AWS, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud, and others as they expanded in Australia.

Third: carrier neutrality. The strategy wasn’t to be the biggest telco or the loudest brand. It was to be the most connected meeting place, even if that meant refusing tempting, short-term deals that compromised the “Switzerland” positioning.

And fourth: the physical layer of AI. Training and running modern models isn’t just “more servers.” It changes the demands of a data centre—power density, cooling, design—and NEXTDC is trying to build what the next decade of compute requires.

The investor lesson is one of those truths that sounds dull until it makes you rich: infrastructure, when it sits in the right spot in the value chain, can compound in ways that make a lot of flashy software stories look fragile. When NEXTDC listed, cloud was still early. ChatGPT didn’t exist. And the idea of “AI factories” needing hundreds of megawatts of power would’ve sounded like science fiction. NEXTDC built for each wave as it arrived—and the compounding did the rest.

II. The Founder: Bevan Slattery's Entrepreneurial DNA

The Regional Queensland Origin Story

To understand NEXTDC, you have to understand where Bevan Andrew Slattery came from—and why it mattered that he didn’t come from anywhere resembling a tech scene.

Slattery grew up in Rockhampton, Queensland. He went to Frenchville State School, graduated from North Rockhampton State High School in 1988, then attended Central Queensland University, which later awarded him an honorary MBA. Rockhampton sits on the edge of the outback. It’s a beef-cattle town of roughly 80,000 people. It is not, by any definition, a launchpad for internet infrastructure empires.

His first job wasn’t in a startup or a lab. He worked as a trainee local government clerk for Rockhampton City Council. Sit with that for a second: the guy who would go on to build and list multiple major infrastructure companies started out processing the machinery of a regional council—forms, departments, the day-to-day grind of public administration.

He left Rockhampton to broaden his career in government, then realised the system wasn’t for him. He moved to Brisbane, started an accounting degree, and got pulled—hard—toward technology and entrepreneurship.

“I worked in different local government departments for three years and really liked certain aspects of it,” Slattery has said. “But the whole time, and during my studies, I knew I needed to be in IT. Throughout those experiences, I also realised I just couldn’t work for someone else.”

Those Rockhampton roots show up later as a kind of operating philosophy. He wasn’t building for Silicon Valley status. He was building because he saw practical bottlenecks—and because when you grow up far from the centres of power, you learn to be resourceful and make things work.

The iSeek Warm-Up (1998-2000)

In 1998, Slattery co-founded iSeek, a cloud, data centre, and connectivity provider that was sold to US firm N2H2 for US$16 million in 2000. This was his first real swing—and, more importantly, his first exit. In the pre–dot-com-crash era, he built a business around internet content filtering for schools and families, then found an American buyer willing to pay up for it.

He’s described just how thin the margin was in those early days.

“I invested everything I had into iSeek and had literally no money left afterwards. I was living between friends, jumping trains and eating two-minute noodles for about a year,” Slattery recalled. “Although it was difficult at times, I knew I was where I was meant to be.”

iSeek taught him something that would become a theme: you could build serious infrastructure-adjacent technology businesses in Australia, sell to global buyers, and create real outcomes—if you picked the right part of the stack.

PIPE Networks: The First Major Score (2001-2010)

If iSeek was the warm-up, PIPE Networks was the breakout. And it started with a goal so small it sounds like a joke—until you see what it became.

“It was Slattery’s least ambitious project, Pipe Networks, that took him places he had never imagined. ‘I started Pipe with Steve Baxter,’ says Slattery. ‘Our goal was to make enough money to go fishing every Friday.’ They fished once. Meanwhile, the pair designed a submarine cable from Sydney to Guam and grew the company into the largest independent fibre network in Australia.”

That’s the story in miniature: aim for lifestyle, stumble into nation-scale infrastructure.

Slattery and Baxter—who later became widely known through Shark Tank—built a roughly 7,000-kilometre submarine cable from Australia to Guam. Slattery has said it cut the cost of international internet capacity by about 75 per cent at the time. In an isolated market like Australia, that kind of link isn’t just “telecom.” It’s leverage.

This is where the picks-and-shovels approach fully clicked. They weren’t trying to win consumer mindshare. They were building the underlying pipes that every internet business depended on—and in doing so, they sat in the path of everyone else’s growth.

Then came the payday. PIPE Networks sold to TPG Telecom in May 2010 for an enterprise value of $430 million. Slattery could’ve taken the win, disappeared, and fished every Friday for the rest of his life. He didn’t.

“Sometimes I don’t know why I keep chasing it, but I just can’t help myself.”

And the timing is the key plot point: May 2010. Seven months later—December 2010—NEXTDC would list on the ASX. He didn’t take a victory lap. He started the next build almost immediately.

The Serial Founder Pattern

Slattery is credited with launching two of the most successful ASX-listed tech stocks of the last decade—NEXTDC and Megaport—with a third, Superloop, catching fire in 2023.

More broadly, he’s been credited with founding a record five ASX-listed companies, including PIPE Networks, NEXTDC, Megaport, and Superloop—businesses that, collectively, helped shape Australia’s digital infrastructure.

And the common thread is unmistakable. Slattery doesn’t build apps. He builds the parts nobody sees until they fail: submarine cables, fibre networks, data centres, interconnection platforms. He finds the chokepoints—the places where data, traffic, and reliability bottleneck—and he builds businesses that relieve them.

He debuted on the Financial Review 2020 Rich List with a net worth of A$564 million. But the more important asset wasn’t money. It was accumulated know-how: how to finance capital-heavy projects, negotiate with carriers and cloud providers, and design infrastructure that enterprises trust. That’s the real precursor to NEXTDC.

III. Founding NEXTDC: The 2010 Vision

Post-GFC, Pre-Cloud: The Perfect Timing

NEXTDC didn’t come out of a victory lap. It came out of a near-death experience.

In the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis—what Slattery has called his greatest professional challenges—PIPE Networks’ submarine cable project nearly collapsed. A bank that was meant to provide half the financing walked away, and Slattery suddenly had a $100 million hole to fill.

That moment hardwired a lesson that would define NEXTDC from day one: if you’re going to build critical infrastructure, you need patient, flexible capital—and you need more of it than you think.

NEXTDC was founded in May 2010. It listed on the ASX in December 2010. Put the sequence together and you see the pace: PIPE Networks sold in May; NEXTDC was founded in May; NEXTDC was public by December. Slattery wasn’t slowing down. He was redeploying.

And the timing wasn’t just personal—it was technological. Cloud computing was starting to feel inevitable, even if it wasn’t yet fully visible in Australia. Big enterprises were beginning to rethink what “a data centre strategy” even meant. Global platforms were gearing up for local expansion. Slattery’s bet was that Australia was about to need a new kind of digital real estate: highly connected, enterprise-grade facilities that didn’t force customers to pick sides.

In other words, Switzerland—but for data.

The Carrier-Neutral Insight

One of the strangest details in the origin story is that NEXTDC didn’t begin as “let’s build data centres.” In interviews, Slattery has said the original idea was an iPhone app.

Then the thought process snapped into place: he didn’t want to build a data centre business unless it could change the industry. So the vision quickly evolved into something far more ambitious—becoming the most trusted, connected, and recognised data centre provider across Australia and New Zealand.

“The data centre market was quite heated at the time, so once again for us it was all about taking the oxygen out of the market,” Slattery said.

That line sounds aggressive, but the strategy was precise. Don’t compete on marginal differences. Build the obvious meeting point—so connected, so reliable, and so neutral that the market consolidates around you.

Carrier neutrality was the unlock. Telstra, the dominant telco, had data centres—but many customers worried about lock-in. Enterprises wanted optionality. Cloud providers needed a place to land that didn’t advantage a rival network. Banks and government agencies needed resilience, redundancy, and control. NEXTDC positioned itself as the place all of these players could interconnect without compromise—no favourites, no hidden toll roads, no “you can only use our network.”

If PIPE Networks was about building the pipes, NEXTDC was about building the exchange where everyone meets.

The Capital-Intensive Gamble

The catch, of course, was that data centres are brutally capital intensive. NEXTDC listed early because raising that kind of money privately in Australia at the time was difficult. Slattery had proceeds from the PIPE Networks sale—$373 million in 2010—but a national build-out would require far more capital than any one founder could sensibly self-fund.

So NEXTDC went public. In its IPO, it raised $40 million at $1 per share, valuing the company at about $80 million.

That’s the part that still feels almost absurd in hindsight: NEXTDC was asking public-market investors to back a company with zero operational data centres. It wasn’t selling a proven annuity stream. It was selling a plan—and a team’s ability to execute it.

The board leaned into the positioning. Chairman Roger Clarke called it Australia’s first ASX-listed dedicated data centre provider, committing to design, develop, and operate “a network of secure, efficient and stable enterprise class data centres.”

The IPO money became the first set of keys: properties in Brisbane and Melbourne. And it established the pattern that would power everything that followed. NEXTDC would keep coming back to the capital markets—but each time with more proof, more operating history, and more confidence from customers that this wasn’t a concept.

It was the beginning of a very expensive flywheel. And once it started turning, it got harder and harder to stop.

IV. The Build-Out Years: From Zero to National Footprint (2010-2015)

Rapid Property Acquisition

After the IPO, NEXTDC did what a lot of newly public companies say they’ll do, but rarely manage at speed: it started locking up real estate.

Because in data centres, the address is strategy. You need the right power, the right fibre routes, the right zoning, the right proximity to customers—and the best sites don’t wait around for you to get comfortable.

Even before everything was switched on, momentum was building. NEXTDC secured its first customer, Harbour MSP, which committed to 1,000 square metres at the Melbourne facility. The company was already talking in “online dates”: Brisbane targeted for March, Melbourne for November the following year, with a Sydney site expected to be announced by March.

Then the first proof point arrived. By October 2011, B1 Brisbane went live. NEXTDC positioned it as Queensland’s most fibre-connected data centre, and more importantly, it was the template for what came next: premium location, carrier-neutral connectivity, and a facility built to enterprise expectations from day one.

From there, the footprint snapped into place. In 2012, NEXTDC opened M1 in Melbourne, C1 in Canberra, and S1 in Sydney—giving the company presence across the major capital cities that mattered most for enterprise and government workloads. Melbourne anchored the southern market, Sydney covered enterprise demand and international connectivity, Canberra gave credibility with government, and Brisbane remained both the starting point and the operating hub.

The CEO Transition: Craig Scroggie Takes the Helm

In June 2012, NEXTDC made a move that signalled it was shifting from “founder build” to “operator scale.” Craig Scroggie became Chief Executive Officer, and Bevan Slattery stepped back into a non-executive Deputy Chairman role.

That handoff is classic Slattery. He’s the architect and the starter motor—design the product, set the strategy, get it into motion—then bring in a seasoned operator to run the long, grinding, execution-heavy phase.

Scroggie wasn’t a startup gamble. He’d been on the board since the IPO, including as Chair of the Audit and Risk Management Committee, and he brought more than 30 years of ICT experience across Symantec, Veritas Software, Computer Associates, EMC, and Fujitsu. Immediately prior, he was Symantec’s Vice President and Managing Director for the Pacific Region.

That mattered because NEXTDC wasn’t selling racks and floor space. It was selling trust to big organisations with slow procurement cycles, high compliance standards, and CIOs who needed a credible counterparty. Scroggie’s background gave NEXTDC what it needed to win those rooms.

When the leadership change was announced, Slattery said attracting Scroggie was a significant coup. And it fit the broader playbook: Slattery retains meaningful ownership and board involvement, but the day-to-day shifts to someone built for scale—freeing him up to go invent the next chokepoint business while NEXTDC compounds.

Building Credibility Through Certification

NEXTDC also did something that, in the early 2010s Australian market, was both expensive and unusually disciplined: it pursued independent certification as a core part of the product.

Enterprise customers and government agencies don’t bet critical workloads on promises. They bet on standards. NEXTDC’s first-generation facilities achieved Tier III certification from the Uptime Institute, the widely recognised benchmark for data centre reliability. Tier III means concurrent maintainability—the site can undergo planned maintenance without taking customer systems down.

It’s the kind of detail that sounds technical, until you’re the person responsible for keeping a bank, airline, or government department running 24/7. Then it becomes the difference between “nice pitch” and “approved vendor.”

The Fastest-Growing Tech Company in Australia

By that point, the company wasn’t just building facilities—it was building legitimacy.

In three years, NEXTDC had become an ASX 300 company with a market capitalisation of almost half a billion dollars. And in 2015, Deloitte named NEXTDC Australia’s fastest-growing technology company.

That arc is the whole story of the era: December 2010, a $40 million IPO and zero operational sites. Five years later, a national footprint of enterprise-grade data centres and a growth profile that put it at the top of the country’s tech leaderboard.

Execution mattered. But so did timing. NEXTDC was laying down the physical layer Australia needed right as enterprise IT started shifting from “closets full of servers” to “mission-critical infrastructure, outsourced to specialists.” The wave was coming. NEXTDC made sure it owned the on-ramp.

V. Inflection Point #1: The Cloud On-Ramp Strategy (2015-2018)

Becoming the Hyperscaler Gateway

By 2015, NEXTDC had proved it could build and run serious facilities. The next question was: what would make those buildings indispensable?

The answer wasn’t just more racks. It was interconnection—becoming the meeting point between enterprises and the hyperscalers.

In December 2015, NEXTDC announced an IBM Direct Link hosting location at M1 in Melbourne. A month later came AWS Direct Connect at the same site. These weren’t ordinary “new customer” press releases. They were a land grab for the most valuable spot in the ecosystem: the place where Australian companies could plug into the cloud privately, reliably, and with low latency.

That’s the promise NEXTDC started selling: scalable, on-demand connections into the major cloud platforms—Microsoft Azure, AWS, Google Cloud, IBM Cloud, Oracle Cloud—alongside dedicated, point-to-point cross connects for performance and control.

The timing was perfect. Enterprises weren’t ready to forklift everything into the cloud. What they wanted was hybrid: keep critical systems close, move what made sense, and connect the two like they were on the same network. NEXTDC positioned itself as the physical layer that made hybrid practical—the place where corporate networks met cloud networks without detours.

And once those cloud on-ramps started clustering inside the same facility, the flywheel kicked in. If customers wanted optionality, then cloud providers wanted to be where customers already were. One hyperscaler landing at M1 made it more valuable for the next one. The more clouds present, the more partners showed up. The more partners showed up, the more customers had to be there. Connectivity became the product.

The AXON Platform: Interconnection as a Service

NEXTDC pushed that idea even further with AXON: its software-defined interconnection platform.

With AXON, customers could connect securely across locations, link AXON-enabled data centres, and reach cloud on-ramps through point-to-point Ethernet—without treating every new connection like a bespoke cabling project. AXON virtual connections tied together organisations, networks, and cloud providers, giving direct access to public and private clouds and to a partner ecosystem of more than 750 networks and ICT service providers operating inside NEXTDC’s facilities.

This mattered because it changed the operating model. Instead of waiting weeks for physical work, customers could provision connections quickly, scale bandwidth up or down, and spin up new links as needs changed. One AXON port could support many virtual connections through Elastic Cross Connects (EXCs): fast, secure virtual circuits delivered on demand. In plain terms, AXON turned connectivity into something closer to an API than a construction job.

Strategically, AXON also changed NEXTDC’s economics. Colocation can be sticky, but it still looks like real estate: contracts renew periodically, and customers can move if they really want to. Interconnection is different. Once a customer has built their architecture around dozens of virtual links—cloud to cloud, cloud to partner, partner to partner—leaving isn’t just moving racks. It’s unpicking the nervous system of their IT environment. AXON made NEXTDC harder to replace.

That’s why later expansions of AXON’s capabilities, like the March 24, 2025 announcement of 100Gbps ports, mattered. It wasn’t just “faster networking.” It was NEXTDC scaling the interconnection layer to match the next wave of demand—especially AI-driven workloads that need far more bandwidth and far more predictability.

Breaking Even and Proving the Model

All of this was happening inside a business model that takes a long time to validate. Data centres demand huge upfront spend, and you only earn your returns as the building fills.

NEXTDC spent six years in build-and-fill mode before reporting its first-ever profit in FY2016. That milestone mattered because it proved the machine worked: build capacity, attract an ecosystem, fill it, repeat.

The growth curve told the same story. Annual data centre services revenue rose from $1.2 million in FY12 to more than $205.5 million by 1H21. For an infrastructure business, that kind of expansion is rare—and it was supported by improving unit economics as facilities matured.

By the end of this period, NEXTDC wasn’t simply a landlord for servers. It had become the on-ramp to the cloud for Australian enterprises—and it was building a connectivity platform that made the entire ecosystem compound.

VI. Inflection Point #2: The Tier IV Differentiation (2017-2020)

The Only Tier IV Network in the Southern Hemisphere

By the late 2010s, NEXTDC had already won the first battle: build a national footprint, then turn those buildings into the place where cloud and enterprise met.

Now it went after something harder to copy than square metres of white space: being the reliability benchmark.

In 2017, NEXTDC pulled off what no other data centre operator in the Southern Hemisphere had done. Its B2 Brisbane facility, the first of its second-generation sites, received Tier IV certification from the Uptime Institute. It was also the first Australian data centre, and the first Asia-Pacific colocation data centre, to receive Tier IV Certification of Constructed Facility.

This wasn’t a minor badge. Tier IV is a different class of facility. Where Tier III is designed so you can maintain systems without bringing customers down, Tier IV is built so a single equipment failure won’t impact operations at all. That fault tolerance is what the most demanding customers actually pay for: financial systems that can’t pause, healthcare data that can’t disappear, and government operations that can’t afford a bad day.

Tier IV is often described as the pinnacle: fault-tolerant design that targets 99.995% availability—about 26 minutes of potential downtime in a year.

NEXTDC then went a step further on operations, becoming the first data centre operator in the Southern Hemisphere to achieve Tier IV Gold Certification of Operational Sustainability from the Uptime Institute. That certification wasn’t about the building’s blueprints; it recognised the company’s operating discipline over time—how it manages long-term risks, processes, and behaviours. In other words: not just “we built it right,” but “we run it right.”

Why Tier IV Matters: The 100% Uptime Promise

NEXTDC sells critical power, security, and connectivity to hyperscalers, enterprises, and government. At Tier IV, reliability stops being a hopeful talking point and becomes an engineering-backed promise.

That “100% uptime” language isn’t meant as hype. In Tier IV facilities, the architecture is designed for fault tolerance, and the expectation from customers is simple: failure of a component should not equal failure of service. For organisations running truly mission-critical systems, that changes the risk calculus. It’s not just about avoiding inconvenience; it’s about preventing existential events.

Uptime Institute’s John Duffin put a fine point on what made B2 unusual:

“Enhancing the strategies used in their Tier III data centres, in B2, NEXTDC have achieved Australia's first Uptime Institute Tier IV Constructed Facility Certification and globally, the first Tier-Certified data centre with a Fault Tolerant N+1 redundant IP-DRUPS electrical system.”

What’s striking here is that NEXTDC didn’t position Tier IV as “we spent infinitely more than everyone else.” The company emphasised that the outcome came from engineering and design choices, not just brute-force redundancy. B2, for example, achieved Tier IV fault tolerance in its electrical system with an N+1 approach that required adding one extra RUPS unit (+1) beyond what was needed to support the facility (N). The point wasn’t the component list; it was the message to the market: NEXTDC could deliver Tier IV-grade reliability without pricing itself into an uneconomic corner.

And that’s where Tier IV became a competitive weapon. If NEXTDC could deliver premium reliability without a massive cost penalty, competitors faced an unpleasant choice: match the capability and accept the execution risk, or keep selling “good enough” and watch the highest-value customers concentrate elsewhere.

The Government and Enterprise Play

Reliability is one half of the enterprise equation. The other half is compliance, sovereignty, and procurement reality—especially in government.

NEXTDC is certified by Australia’s Digital Transformation Agency (DTA), positioning it as a compliant, sovereign critical infrastructure option for government at all levels. That matters because government buyers don’t just want uptime. They want the assurance that the facility and operator meet specific security and compliance standards, and that the infrastructure sits under Australian jurisdiction.

For agencies that needed secure, Australian-based infrastructure with serious connectivity and operational maturity, NEXTDC increasingly looked like the obvious shortlist candidate.

And as the company expanded its Tier IV footprint into new markets, it used that same language to frame what these facilities enabled. CEO Craig Scroggie said of the A1 facility: “The A1 facility is Adelaide's first Uptime Institute Tier IV-certified data centre which will play a pivotal role in accelerating digital innovation and preparing South Australia to take advantage of the” fourth industrial revolution powered by AI.

The strategic upside of government and enterprise customers is simple: they’re cautious to win, but once you win them, they tend to stay. When an agency or a major enterprise anchors critical systems in a facility built and operated to Tier IV standards, moving isn’t a quick vendor switch. It’s a long-haul commitment—exactly the kind of demand that makes a capital-intensive business model start to look like an annuity.

VII. Inflection Point #3: The Hyperscale Pivot (2020-Present)

From Retail Colocation to Wholesale/Hyperscale

NEXTDC’s first act was “retail” colocation: enterprises renting racks, cages, or private suites to run their own gear. That was the right product for the early 2010s, when cloud was still a migration plan and most companies were keeping a lot on-prem.

But by 2020, demand was changing shape. Cloud providers and hyperscale customers weren’t shopping for rack counts. They were shopping for raw power and large, contiguous footprints: entire halls, entire buildings, whole campuses—capacity measured in megawatts.

You can see that shift just by looking at Melbourne. M1, in Port Melbourne, went live in 2012 with about 15MW across roughly 6,000 square metres. M2 followed in 2017 at around 60MW and 25,000 square metres. Then M3 launched in 2022, scaling again to about 150MW across roughly 40,000 square metres.

The point isn’t the exact spec sheet. It’s the pattern: each new generation wasn’t incremental. It was a step change. NEXTDC was moving from serving lots of mid-sized customers to being able to serve a few customers with truly massive requirements—without abandoning the ecosystem that made its original sites sticky in the first place.

At the same time, the footprint was spreading. NEXTDC now operates or is developing 20 data centres across Australia, including Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth, Port Hedland, Canberra, Adelaide, the Sunshine Coast, and Darwin. That geographic list tells you what the company was becoming: not just a Sydney-and-Melbourne operator, but a national piece of infrastructure—showing up where industry and government actually needed sovereign, local capacity.

The Geographic Expansion

In February 2022, NEXTDC announced it would invest more than $100 million to build a data centre on Pirie Street in Adelaide.

Later, the company officially opened A1—Adelaide’s first Tier IV certified data centre—positioning it as critical infrastructure for South Australia’s government and business sectors. Located within Adelaide’s city grid, A1 targeted 5MW of capacity and around 3,000 square metres of IT space. NEXTDC framed it as a next-generation facility built to support South Australia’s government, defence, space, health, mining, and resources industries.

That’s what changed in this era. A1 wasn’t marketed as “more racks.” It was marketed as a platform for sovereignty and regional capability—digital infrastructure as economic development.

The Massive Capital Raises

A hyperscale pivot isn’t just a product shift. It’s a balance-sheet shift.

In April 2024, NEXTDC announced a $1.32 billion capital raise to accelerate expansion in Sydney and Melbourne. Around the same time, it expanded its debt facilities by a further AU$1.3 billion, taking total senior debt facilities to AU$6.4 billion. The company said the strengthened position gave it flexibility to accelerate build-outs amid record demand for AI and cloud infrastructure.

For context, this is the same business that listed with a $40 million raise and no operational sites. Now it was assembling the kind of capital base you need to develop multiple hyperscale campuses in parallel.

NEXTDC has also said it secured a new $5 billion facility that had not been drawn down yet, and therefore wasn’t reflected on the balance sheet.

The S7 Mega-Site: 550MW of Future Capacity

Then came S7: a new Sydney site at Eastern Creek, about 45 kilometres west of Sydney’s CBD, in the Western Sydney availability zone.

S7 spans roughly 258,000 square metres of developable land and sits close to a major electricity substation, along with telecommunications and other supporting infrastructure. Subject to development approval, NEXTDC expects S7 to accommodate a data centre facility capable of around 550MW of capacity, with additional space for customers’ mission-critical operations centres, administrative offices, and collaboration areas. The purchase price was approximately A$353 million.

That 550MW figure is the tell. This wasn’t “the next building.” It was NEXTDC planning for a different scale of customer and a different scale of compute.

The company has pointed out that its existing portfolio represented about 228MW of contracted utilisation—meaning S7 alone, if built out, could dwarf what NEXTDC had already contracted across the country.

Across S4 and S7 together, NEXTDC flagged roughly A$15 billion of capital requirement over more than a decade to deliver about 850MW of new capacity. S7 on its own was expected to represent around A$7 to A$7.6 billion of total investment once fully built, depending on final design, power connection, and customer demand.

VIII. Inflection Point #4: The AI Factory Era (2024-Present)

NVIDIA Partnership and GPU-Ready Infrastructure

NEXTDC’s cloud era strategy made it the on-ramp for enterprises moving into AWS and Azure. The AI era is something else entirely. Now the question isn’t “where do we put our servers?” It’s “where can we run GPU infrastructure at industrial scale?”

That’s what NEXTDC signalled when it received NVIDIA DGX-Ready Data Centre certification. In practical terms, it meant NEXTDC could support Australian organisations with digital infrastructure architectures designed specifically for NVIDIA’s AI platforms.

And strategically, it changed the story NEXTDC could tell the market. This wasn’t just colocation anymore. It was purpose-built infrastructure for AI deployment.

As AI adoption accelerates, many organisations want the performance and control of running serious AI workloads, but don’t want to build and operate a new class of data centre themselves. Through the NVIDIA DGX-Ready Data Centre program, NEXTDC positioned itself as the middle path: state-of-the-art facilities and comprehensive services, designed to help enterprises scale AI initiatives quickly.

NEXTDC has pointed to S6 Sydney as the clearest example of that shift. The company describes it as Australia’s first purpose-built AI factory, certified from day one for deployment of NVIDIA DGX-ready reference architecture, built for high-density power and advanced liquid cooling. It says customers across multiple industries are already scoping and using the facility to train, run inference, and deploy AI models at production scale, with support for rack densities up to 130kW and nearby AXON access up to 100Gbps.

The Liquid Cooling Revolution

For most of the modern data centre era, air cooling was the default. Fans push cold air in, hot air comes out, and the building is designed around that airflow.

AI breaks that assumption. GPU-heavy workloads generate so much heat, so densely, that air cooling quickly becomes a constraint. Liquid cooling isn’t an upgrade; it’s a redesign of what a data centre is.

NEXTDC’s AI Factory concept is built around that reality: a hyper-dense, liquid-cooled facility engineered for sovereign AI, designed to support NVIDIA’s Blackwell and Rubin Ultra architectures. The facility is intended to deliver rack densities beyond 1,000kW, enabling large-scale model training, inference, and frontier AI workloads.

To grasp how different that is, compare it to the data centre world enterprises grew up with. Traditional enterprise racks might draw 5 to 10kW. High-density deployments might push into the 20 to 30kW range. NEXTDC is talking about environments that are orders of magnitude above what “normal” used to mean.

That’s also why the company has been leaning so hard into new campuses built around AI requirements. NEXTDC announced an A$2 billion commitment to develop M4 Melbourne, a next-generation digital campus at 127 Todd Road, Port Melbourne. M4 is slated to include an AI Factory, a Mission Critical Operations Centre, and a Technology Centre of Excellence. NEXTDC’s framing is explicit: purpose-built for sovereign AI, HPC, advanced manufacturing, and deep tech—positioning Victoria as a national digital infrastructure hub and strengthening Australia’s edge across the Five Eyes.

Record Contract Wins and the OpenAI Partnership

The market didn’t wait politely for all this to be finished. Demand showed up in signed contracts.

NEXTDC said that following recent customer wins, its pro forma contracted utilisation as at 31 March 2025 increased by 52MW, or 30%, to 228MW since 31 December 2024. It also noted that Victoria benefited most from the uplift, including the largest AI deployments recorded in the company’s portfolio to date.

A jump like that in a single quarter is the tell. The AI buildout isn’t a slow trend line. It’s a step change.

Then came the headline that made the shift impossible to ignore: OpenAI for Australia. OpenAI launched it as a nationwide initiative to expand AI adoption and build sovereign digital infrastructure. For NEXTDC, the key development was a new partnership to plan and develop a hyperscale AI campus in Sydney—one of Australia’s biggest moves yet toward dedicated sovereign compute for advanced AI workloads.

The centrepiece is a Memorandum of Understanding between OpenAI and NEXTDC, described as the basis for a long-term strategy to deploy sovereign AI infrastructure inside Australia. The announcement sent NEXTDC’s stock up nearly 11%.

Why does that matter so much? Because partnerships like this don’t just add prestige. They change financing math. NEXTDC’s biggest projects—especially S7—are massive, multi-year capital commitments. Having the world’s most visible AI company involved early helps validate the bet while the concrete is still being poured. It makes the idea of S7 as a future anchor site for sovereign GPU capacity feel less like a speculative build and more like an emerging plan with real gravity behind it.

OpenAI for Australia is OpenAI’s first national program in the Asia Pacific region. And at its core sits that collaboration with NEXTDC—positioning the company’s Sydney expansion as infrastructure built not just for cloud, but for the next generation of AI systems.

International Expansion Plans

Even as NEXTDC pushes deeper into hyperscale and AI at home, it’s also looking outward.

The company has said it has sites under planning or evaluation in Tokyo, Bangkok, Johor, Kuala Lumpur, and Singapore—an explicit signal that it wants to become a regional leader in data centre infrastructure, supporting cloud and AI platform expansion across APAC.

CEO Craig Scroggie framed the ambition this way: “We are thrilled to announce our expansion into Malaysia and New Zealand, which marks an important milestone in our growth strategy. Building upon the success we have achieved in Australia over the past decade, we aim to replicate our proven business model in these new markets. As always, our focus remains on creating a highly diversified ecosystem of enterprise, connectivity, cloud, and managed service provider customers. New Zealand and Malaysia are just the first greenfield geographic expansion opportunities outside of Australia, and we are excited about the possibilities ahead.”

And the company has laid out the financial intent to match the geographic intent. It said a syndicated loan, together with an A$750 million capital raising, would provide more than A$3 billion to fund a rollout of nine sites across the region, including Malaysia, Japan, New Zealand, and Thailand.

IX. The Business Model Deep Dive

Revenue Model: The Annuity Engine

At its core, NEXTDC gets paid for three things: space, power, and connectivity. Enterprises, government agencies, and cloud providers lease capacity inside its facilities, typically under long-term contracts.

What makes the model so attractive is how annuity-like it becomes after the initial move-in. Once a customer has deployed their infrastructure—servers, storage, networking, security controls—it’s not just a line item they can casually swap out at renewal time. Moving data centre environments is disruptive and expensive. It can involve downtime, revalidation, compliance work, and a lot of risk. So customers tend to stay put unless there’s a compelling reason to leave.

That stickiness shows up in the numbers. Total revenue increased A$42.0 million (12%) to A$404.3 million (FY24 Guidance: A$400 – A$415 million). Underlying EBITDA increased A$10.6 million (5%) to A$204.3 million. Strong ecosystem growth with interconnection revenues increasing A$3.0 million (12%) to A$28.3 million.

The key nuance is that interconnection grew right alongside the core colocation business. And interconnection dollars are particularly valuable: they tend to expand over time as customers add more links—into clouds, into partners, into other sites—turning a “we rent space” relationship into “we run your digital nervous system.”

Between FY2019 and FY2024, NEXTDC’s revenue rose steadily, reaching more than A$404 million in FY2024.

The Partner Ecosystem Flywheel

NEXTDC doesn’t just sell a secure building with power. It sells proximity to an ecosystem.

Across its facilities, customers can connect into a national community of more than 750 public and private cloud providers, carrier networks, and managed service providers. That density creates the flywheel: every new partner makes the location more useful to customers, and every new customer makes the location more attractive to partners.

It’s why the company leans so hard on the pitch that you can get direct interconnection access from day one from your rack to all points of presence within NEXTDC’s AXON ecosystem. In practice, it means faster deployments, better optionality, and less dependence on any single network or vendor—exactly what enterprise and government buyers want.

Sustainability as a Moat

NEXTDC also competes on something that used to be “nice to have,” and is now increasingly table stakes: sustainability.

It is certified carbon neutral under the Australian Government’s Climate Active Carbon Neutral Standard. That matters because large enterprises are under pressure to report and reduce emissions across their supply chains. If your colocation provider can credibly offer carbon-neutral operations, that can help customers meet ESG commitments, including Scope 3 emissions targets.

Operational efficiency is part of that story, too. NEXTDC’s M1 and S1 are certified to NABERS 5-Star, and P1 holds a 4.5-Star energy efficiency rating.

These ratings aren’t just a PR badge. Energy efficiency affects the economics of the entire business. More efficient facilities reduce the overhead needed to deliver each megawatt of IT load, which helps operating costs and, over time, margins.

The Non-Dividend Reinvestment Strategy

Then there’s the piece that can confuse people looking at NEXTDC through a traditional “profits and dividends” lens.

The company made a post-tax loss of $60m, $16m higher than the $44.1m in FY24, which was double the year prior. The reason is straightforward: it has been building data centre capacity.

So even while it generated over $200 million in EBITDA, it remained loss-making on a statutory basis and did not pay dividends. That’s not a sign the model is broken. It’s a sign the company is still in build mode—reinvesting heavily to get new capacity online ahead of demand.

Consensus estimates expect similar losses for the next two years, with profitability expected in FY29.

For investors, the implication is clear: NEXTDC is a growth story, not an income story. You’re underwriting the long game—future utilisation of capacity it’s building now—rather than collecting current cash distributions.

X. Competitive Landscape: The Australian Data Centre Wars

The Major Players

By the mid-2020s, Australia didn’t have “a” data centre industry so much as a full-on arena.

The list of serious operators is long: AirTrunk, NEXTDC, Canberra Data Centres (CDC), Equinix, Global Switch, DCI Data Centers, Keppel Data Centres, Digital Realty, STACK Infrastructure, and more.

AirTrunk is the biggest, with NEXTDC and CDC next in line. But size alone doesn’t tell you who wins what.

AirTrunk has owned the hyperscale identity: giant, purpose-built campuses designed first and foremost for cloud providers. That focus drove its rapid rise and culminated in a headline deal in late 2024, when US private equity firm Blackstone acquired a majority stake valuing AirTrunk at $24 billion.

NEXTDC sits in a different lane. It plays across the spectrum—from enterprise colocation all the way up to hyperscale—while leaning hard into the things it’s always sold: carrier neutrality and dense interconnection.

CDC’s lane is even more specific. It’s built a reputation around government and defence, using security accreditations that many competitors can’t easily replicate.

And then there’s Equinix. It isn’t headquartered in Australia, but it’s impossible to talk about Australian interconnection without it. As the world’s largest data centre operator, Equinix has expanded across Sydney, Melbourne, Perth, Brisbane, and other hubs, positioning its sites as high-density, highly connected environments that can support AI-era requirements—low-latency connectivity, interconnection services, and increasingly GPU-ready setups.

The Hyperscaler Frenemies

Here’s the twist: the biggest drivers of demand are also the biggest strategic threat.

Microsoft, Amazon Web Services (AWS), Google Cloud, Oracle Cloud, IBM Cloud, and Alibaba Cloud have all been expanding their presence in Australia. AWS has continued to grow its footprint as the country’s digital economy expands, while Microsoft has pushed deeper in both Sydney and Melbourne.

But hyperscalers don’t just buy capacity. They build it, too.

That creates the “frenemy” dynamic at the heart of the sector: cloud giants can be NEXTDC’s largest customers, while still operating their own facilities. They’ll lease space from colocation providers when it’s faster, more connected, or better positioned for enterprise interconnection. At the same time, every new self-built campus is one less unit of demand up for grabs.

The result is an arms race across the operators. It’s not just about adding more megawatts. It’s about becoming AI-ready: higher-density deployments, liquid cooling capability, stronger power infrastructure, and deeper partnerships with the cloud and chip ecosystem so customers can deploy the next wave of compute without waiting for the industry to catch up.

The Cost Structure Challenge

All of that ambition collides with an inconvenient fact: Australia is a hard place to build.

The Australian data centre market is expected to reach USD 7.32 billion by 2030, growing at a 3.93% CAGR from 2025 to 2030, driven by cloud adoption and cybersecurity needs. But operators face unusually sharp constraints: high electricity costs, expensive land in the best-connected locations, lengthy planning and regulatory processes for major developments, and a tight labour market for the specialised construction and engineering work these sites require.

Those shared constraints are part of what pushed competitors to start acting, at least occasionally, like a coordinated industry.

After a two-year informal pilot involving AirTrunk, Amazon Web Services, CDC Data Centres, Microsoft and NEXTDC, a broader group formed Data Centres Australia, with additional members including Equinix, Goodman Group, Schneider Electric, STACK Infrastructure and TikTok.

The organisation was formalised on 28 November 2025. The message was clear: the sector had reached a level of scale where issues like power supply, water use, workforce development, and planning approvals weren’t just company problems anymore—they were national coordination problems.

XI. Porter's Five Forces and Competitive Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Trying to build a NEXTDC-style data centre network from scratch is less like launching a startup and more like launching a utility. It takes extraordinary capital, and it takes time. Across S4 and S7 together, NEXTDC has flagged roughly A$15 billion of capital investment over more than a decade to deliver around 850MW of new capacity. To compete head-to-head, a new entrant would need to fund projects of similar scale just to get into the conversation on cost and capability.

And the cheque is only the beginning. The real gatekeepers are scarce land, scarce power, and scarce trust. Prime sites are limited. High-voltage grid connections can take years to secure. And enterprise and government customers don’t gamble critical workloads on an operator without a proven track record. NEXTDC’s Tier IV certifications, approvals, and deeply established partner ecosystem all compound into a barrier that’s hard to shortcut.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

NEXTDC’s inputs are the same bottlenecks the whole industry is fighting over: electrical equipment for power systems, mechanical equipment for cooling, and the construction specialists who can actually build these facilities. The global data centre boom has strained supply chains, pushing costs up and stretching lead times out.

But scale helps. NEXTDC’s pipeline and purchasing volume give it leverage, and it has diversified supplier relationships to reduce the risk of being held hostage by any single vendor or contractor.

Bargaining Power of Customers: VARIES

The customer story splits in two.

For enterprise colocation customers, switching is painful. You’re not just moving racks; you’re moving architectures, security controls, compliance documentation, and connectivity. That tends to give NEXTDC meaningful pricing power, especially when its sites are the most connected place to be.

For hyperscale customers, the balance shifts. These customers buy capacity in huge blocks, their contracts matter disproportionately, and they have credible alternatives—including building and operating their own facilities. Hyperscalers can, and do, negotiate hard.

Even so, the market’s current shape favours operators with ready capacity. As of 31 March 2025, NEXTDC reported Victorian pro forma contracted utilisation of 114MW, versus built capacity of 70.5MW at 31 December 2024. It also reported that its pro forma forward order book increased by 45MW since 31 December 2024 to 127MW, a record for the company.

The important takeaway isn’t the accounting nuance. It’s what the imbalance implies: customers have committed to more capacity than is currently built, which is a strong signal that demand is running ahead of supply—and that’s generally a good place to be if you’re selling scarce, mission-critical infrastructure.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW

There isn’t a clean substitute for a modern, carrier-neutral, enterprise-grade data centre.

Running servers in an office is cheaper until it isn’t—security, reliability, and compliance expectations have moved far beyond what most organisations can realistically manage on-prem. Going “all in” on public cloud can work for many use cases, but not for everything: latency-sensitive applications, regulatory requirements, and data sovereignty constraints still push large organisations toward a hybrid approach.

For the foreseeable future, the most common answer remains: keep some infrastructure in colocation, connect it directly to the cloud, and operate across both.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH but DIFFERENTIATED

Rivalry in Australian data centres is intense. But it’s not a commodity knife fight, because the major players have carved out different identities.

NEXTDC leans on its interconnection ecosystem, Tier IV reliability, and the ability to serve a wide spectrum of customer sizes. AirTrunk is built around pure hyperscale. CDC has positioned around government and defence credentials. Equinix brings a global footprint and a deep interconnection heritage.

They all compete, but they’re not all selling the same “product,” even when the buildings look similar from the outside.

Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers Analysis

Process Power: NEXTDC’s engineering and operating playbook—particularly its ability to deliver Tier IV outcomes efficiently—reflects know-how accumulated over years that isn’t easily copied.

Network Effects: AXON gets more valuable as more clouds, networks, and service providers join. That partner density—more than 750 participants—creates a defensible ecosystem dynamic.

Scale Economies: Data centre unit economics improve with scale. Larger builds can drive lower per-megawatt costs across power infrastructure, cooling, and physical security.

Switching Costs: Once customers are deployed and interconnected through AXON, leaving isn’t just a move. It’s a redesign, with meaningful time, cost, and risk.

Cornered Resource: The best sites are constrained by land, fibre, and power access. NEXTDC’s land bank and development pipeline represent resources that are difficult to replicate quickly.

Counter-Positioning: NEXTDC’s carrier-neutral stance is hard for telco-owned data centres to match without undermining their core carrier economics.

Brand: In an industry where “reliable” is the product, NEXTDC’s Tier IV Gold certification and its uptime positioning reinforce trust and support premium pricing.

XII. Key Investment Considerations

The Bull Case

The bull case for NEXTDC is straightforward: it’s sitting in the slipstream of three long-duration waves, and each one reinforces the next.

First, enterprise digital transformation keeps pushing demand toward colocation. Many organisations that once would have built their own server rooms and private facilities increasingly treat that as non-core work—something better handled by specialists with scale, compliance, and operational maturity.

Second, cloud adoption keeps expanding, and NEXTDC benefits as the interconnection layer that makes hybrid real. When enterprises want private, low-latency, high-control links into the big platforms, they need the on-ramps. When cloud providers want to be close to customers, they want to be in the places where networks, partners, and enterprise infrastructure already concentrate.

Third, and most importantly, AI is changing what “demand” even looks like. It’s not just more servers. It’s higher-density power, advanced cooling, and GPU-ready design—and it’s arriving faster than most grid, planning, and construction systems can comfortably support.

That’s the backdrop for NEXTDC’s push into AI-ready infrastructure—and why management believes it’s well positioned inside an Australian data centre market projected to grow quickly through 2027.

The OpenAI partnership is the clearest external validation of the strategy. A Memorandum of Understanding to plan and develop a hyperscale AI campus in Sydney—tied to NEXTDC’s S7 development—does two things at once. It gives the market a credible reason to believe the “AI factory” narrative isn’t just branding, and it improves the odds that the biggest projects in the pipeline get anchored by real demand.

Layer on top of that NEXTDC’s NVIDIA DGX-Ready Data Centre certification and the company’s ability to win large hyperscale AI contracts, and you start to see the shape of the upside: Australia doesn’t just import AI capability through cloud regions—it can host sovereign compute capacity at industrial scale.

Finally, international expansion broadens the opportunity set. NEXTDC has flagged growth into markets like Malaysia, New Zealand, Japan, and Thailand, extending its addressable market beyond Australia. The company has pointed to its Kuala Lumpur facility securing a 10MW hyperscale customer before opening as evidence that demand for high-performance, low-latency infrastructure is not uniquely Australian.

The Bear Case

The bear case is just as real, and it mostly comes down to valuation, execution, and capital intensity.

First, NEXTDC remains loss-making on a statutory basis and trades at demanding multiples. Investors aren’t paying for today’s earnings power; they’re paying for future utilisation of capacity that’s still being built, commissioned, and filled.

Second, execution risk is high. Hyperscale data centres are hard projects: permitting, supply chains, construction complexity, power delivery, and commissioning all create opportunities for delays and cost overruns. Power is the sharpest edge of this risk. Securing enough low-carbon electricity—and the transmission infrastructure to deliver it—can take years. There are currently no public details of signed renewable supply contracts for S7, and grid and planning approvals in Australia can stretch over long timelines.

Third, competition keeps getting better funded. AirTrunk’s backing from Blackstone changes the capital landscape. Global operators like Equinix and Digital Realty continue expanding in Australia. And the hyperscalers—Microsoft, AWS, and Google—can also self-build, making them both the biggest demand source and the most credible substitute.

Fourth, customer concentration is a real risk as the business shifts further into hyperscale. Large contracts can accelerate growth, but the loss or delay of a major customer can leave a meaningful hole in utilisation and forward earnings.

Fifth, the capital requirements are enormous, and that flows into balance-sheet risk. NEXTDC faces the usual operational risks—interruption or outages, contract renewals, and project delivery—but debt management is a central investor concern. Given the scale of the development pipeline, it’s also likely that additional capital raisings will be required unless the company eventually slows expansion and prioritises harvesting cash flows over building new sites.

Key Performance Indicators to Track

For investors following NEXTDC, two operating metrics matter more than most quarterly profit-and-loss headlines because they tell you whether the build is being pulled by real demand.

1. Contracted Utilization Growth (Megawatts)

This is the clearest read on signing momentum. It captures how quickly customers are committing to take capacity, and it provides a forward indicator of revenue as that capacity comes online. As of 31 March 2025, NEXTDC reported that pro forma contracted utilisation increased by 52MW, or 30%, to 228MW since 31 December 2024. The directional signal is what matters: accelerating contracted utilisation suggests demand is outrunning supply; slowing growth can be an early warning that the market is getting saturated or more price competitive.

2. Forward Order Book (Megawatts)

The forward order book is the bridge between “customers have signed” and “customers are paying.” It represents committed capacity that will convert into billing utilisation as new stages are completed and commissioned. NEXTDC reported a record forward order book of 86.6MW expected to ramp into billing across FY25 to FY29, which underpins future revenue and earnings growth if delivery stays on schedule.

Together, these two metrics answer the only question that really matters in a business like this: is NEXTDC building into a vacuum, or building into a queue?

XIII. Conclusion: Building the Physical Layer for the Digital Future

In 2010, Bevan Slattery made a bet that didn’t sound like a tech story at all. He believed Australia’s digital future would be won, or lost, in the physical layer: secure buildings, dense connectivity, and enough power and reliability to run the systems that everything else depends on. And he didn’t want to build a data centre business unless it could actually change the industry. So the vision sharpened quickly into something specific: become the most trusted, most connected, most recognised provider across Australia and New Zealand.

Fifteen years later, that idea looks less like a pitch and more like a blueprint that played out in real time. NEXTDC helped become the on-ramp to cloud computing in Australia. And now, just as that cloud wave matures, a bigger one is arriving behind it. AI doesn’t just mean “more servers.” It means fundamentally different infrastructure: far higher power density, new cooling requirements, and campus-scale capacity that makes the first generation of data centres feel small by comparison.

As Craig Scroggie put it: “This isn’t just a data centre — it’s critical infrastructure for Australia’s AI future.”

He’s also framed the shift in plain language: “Data centres aren’t just sheds full of servers anymore. They’re the beating heart of the digital economy. If you think about what’s happening with AI, sovereign capability, and the sheer scale of digital infrastructure Australia will need over the next decade, it becomes clear that we’re at an inflection point.”

That brings us to the investor question. Can NEXTDC execute on ambitions this large—about $15 billion in planned investment, expansion across Asia-Pacific, and deepening partnerships with the world’s leading AI players—while managing the very real risks of building capital-intensive infrastructure at hyperscale?

What seems clear is that demand has shifted in NEXTDC’s favour. The market is no longer asking for generic colocation. It’s asking for “AI factories”: purpose-built, liquid-cooled, power-dense facilities, connected into the ecosystems enterprises and governments already rely on. NEXTDC spent the last fifteen years building the footprint, credibility, and interconnection fabric that makes it a natural supplier for that next era.

And it’s hard not to come back to the symmetry of the whole story. From two-minute noodles and train-hopping in the 1990s to billion-dollar-scale projects and partnerships like OpenAI for Australia, Slattery’s arc—along with the company he started—has become one of the most consequential infrastructure stories in modern Australian business. The next chapter is being written at a new unit of measurement: not racks or rooms, but hundreds of megawatts at a time.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music