Medibank Private Limited: From Government Experiment to Australia's Healthcare Giant

I. Introduction: A Half-Century Journey Through Australian Healthcare Politics

Picture Melbourne in late 2022. Australia’s largest private health insurer, covering roughly one in six Australians, realizes intruders are already inside its systems. Nearly 10 million current and former customer records have been stolen. Then comes the message: pay $10 million, or the data goes public. The criminals even do the math for them—about a dollar per person.

And this wasn’t just names and emails. The material tied to people’s most private moments: abortion-related records, mental health treatment, HIV status, addiction care. Within days, files would start appearing on the dark web. Medibank’s share price slid, the public panic surged, and CEO David Koczkar was forced into a decision with no clean outcome.

That’s the modern Medibank: a Melbourne-headquartered private health insurer, and the biggest in the country. In 2024, it covered around 4.2 million customers. A huge, familiar brand—until you rewind and realize how strange its origin story is for a public company.

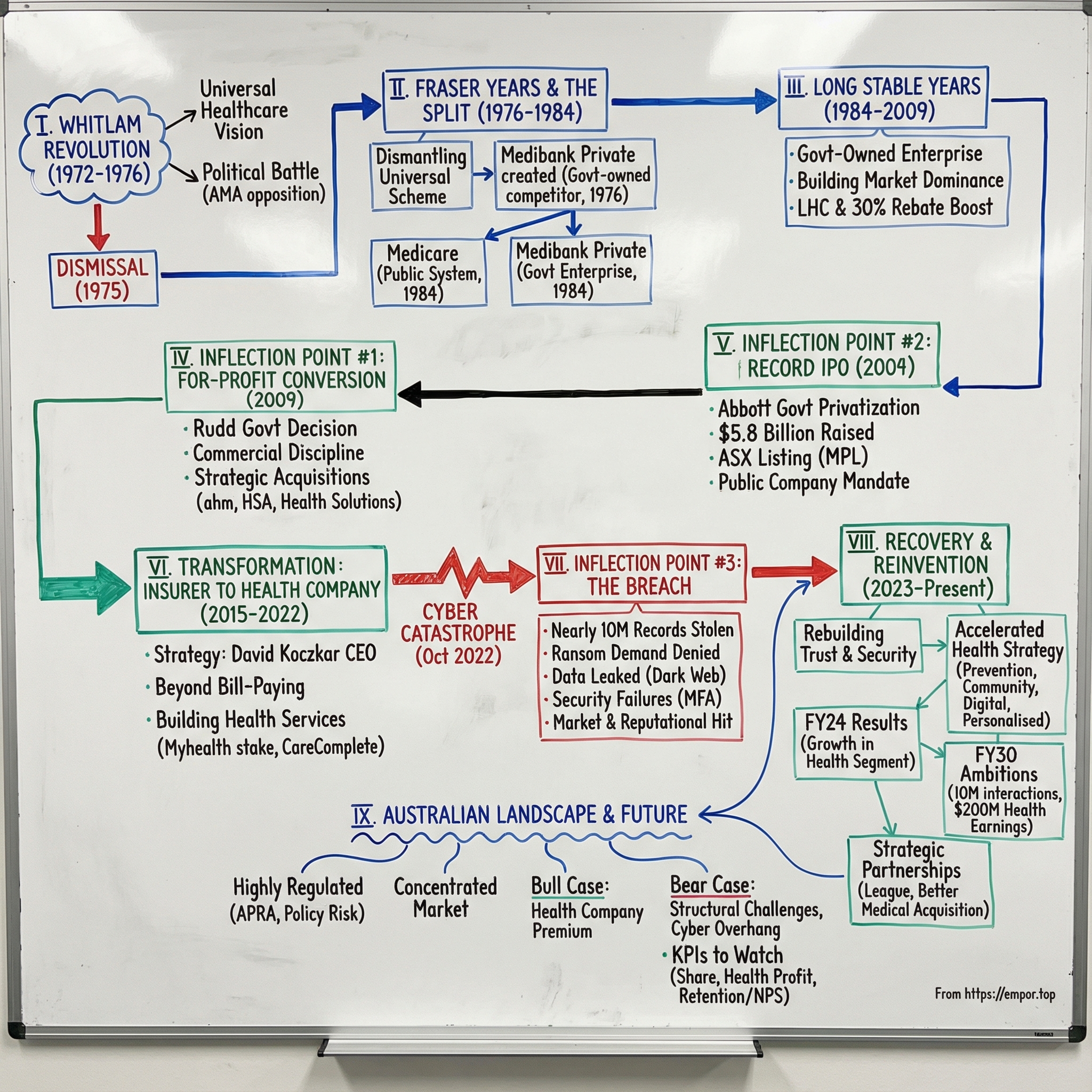

Medibank didn’t begin as an entrepreneurial upstart. It began as a political project. In 1976 it launched as an Australian Government not-for-profit insurer. In 2009, the Rudd Government shifted it into a for-profit footing. And in 2014, the Abbott Government privatized it through a blockbuster IPO.

So here’s the question that makes this story worth telling: how did a government-created insurer—born from one of Australia’s most bitter political fights—turn into a roughly $9 billion public company, survive a catastrophic cyber attack, and still try to reinvent itself into something bigger than insurance?

Along the way, four themes keep showing up.

First: the politics of healthcare. Medibank’s founding sits right on top of a national argument about what healthcare should be, and who should pay for it.

Second: the government-to-market transition. Turning a state-backed institution into a competitive, dividend-paying public company—and doing it via one of Australia’s biggest IPOs ever—offers a rare look at how “public” becomes “commercial.”

Third: pivots under duress. The 2022 breach wasn’t a bad headline—it was a stress test of leadership, governance, and trust.

And fourth: the biggest strategic bet of all. Can a health insurer become a health company? Medibank is wagering that the future isn’t just paying claims—it’s shaping care, earlier and differently.

Let’s go deep.

II. The Whitlam Revolution: Birth of Universal Healthcare in Australia (1972-1976)

Setting the Stage: Australia Before Universal Healthcare

To understand Medibank, you have to start with the system it was built to replace. In the early 1970s, Australia was one of the few wealthy Western countries without universal healthcare. The Coalition parties and much of the medical profession supported a patchwork model: private health insurance, publicly subsidized by government, in a way that still left a huge slice of the population out.

Medibank was designed to cover the people that system didn’t reach. Around 17% of Australians had no health insurance at all, often because they simply couldn’t afford it. The government tried to boost coverage with tax concessions that encouraged people to buy private insurance—but the outcome was hard to defend. The structure was deeply inequitable: higher-income earners could end up paying less than lower-income earners for the same coverage, thanks to how the concessions worked.

This was the core absurdity Gough Whitlam, then Labor leader, wanted to blow up. In the same suburbs, you could find families delaying a doctor’s visit because they couldn’t pay, while better-off neighbors were effectively being helped by the government to insure themselves privately. The people who needed the most support were getting the least.

Whitlam's Vision and the Political Battle

Whitlam’s 1972 election win opened the door to a reform agenda that would remake Australian society, and Medibank sat near the center of it. The mission was simple and confrontational: adequate healthcare for all citizens, regardless of their financial means.

The intellectual blueprint came from two health economists, Scotton and Deeble, who later described how Medibank almost stumbled into becoming Labor policy. They weren’t initially activists; they were doctoral students treating health insurance as a hard policy problem. But their research kept circling the same conclusion: Australia’s private health insurance model was expensive, complex, and riddled with inefficiencies—creating high costs, administrative waste, and a misallocation of resources across the whole system.

And then the fight began.

Opposition was ferocious. Many in the medical profession—along with the General Practitioners’ Society, the Australian Medical Association, and the private health funds—framed Medibank as nothing less than a socialist takeover. They warned that government would control doctors, and that personal freedom was on the line. The AMA ran campaigns sounding the alarm. Private funds saw an existential threat. The rhetoric wasn’t cautious; it was apocalyptic.

The Historic Joint Sitting

Whitlam formed government after the 1972 election. But turning the idea into law became a parliamentary siege. The bills behind Labor’s compulsory health insurance scheme were repeatedly blocked by the Senate. After years of resistance from the Liberal–Country Party opposition, the voluntary health insurance sector, and the AMA, the conflict escalated into a double dissolution election in May 1974.

The deadlock-breaking mechanism that followed was unprecedented: a joint sitting of Parliament—the first in Australian history—used to force the legislation through. Healthcare reform wasn’t just controversial; it pushed the constitution to its pressure limits.

Medibank finally came into operation on 1 July 1975. And then came an execution challenge as big as the politics. In just nine months, the newly established Health Insurance Commission scaled from 22 staff to 3,500, opened 81 offices, installed dozens of minicomputers and hundreds of terminals, linked them back to a central system by landlines, and issued health insurance cards to about 90% of the population.

Demand arrived immediately. In the first months, the HIC was processing well beyond the expected 90,000 claims a day.

It’s hard to overstate what happened here: a brand-new national program, a brand-new agency, a brand-new operational machine—built at breakneck speed, and adopted by nearly everyone. This wasn’t just legislation. It was one of the largest peacetime administrative buildouts Australia had ever attempted.

But the political victory didn’t last. Only five months after Medibank launched, Whitlam was dismissed by Governor-General John Kerr in one of the most controversial episodes in Australian history. And what came next would shape Medibank’s identity for decades.

III. The Fraser Years and the Split: Medibank Becomes Private (1976-1984)

Dismantling and Reinventing Medibank

Malcolm Fraser’s Coalition government won office after Whitlam’s dismissal. Medibank was popular, and the Coalition had promised to preserve it. But once in power, Fraser began pulling it apart.

Over the next few years, Medibank was repeatedly reworked. By 1981, the original scheme had been abolished. The Coalition’s attempt to replace it with a model built around private health funds didn’t land cleanly—it devolved into policy churn, with four major changes in five years.

For ordinary Australians, the result wasn’t an elegant redesign. It was confusion. Coverage fell. The equity gains that had come with Whitlam’s universal vision faded fast. And once again, big parts of the population found themselves shut out of affordable care.

But out of that dismantling came a twist that still shapes the market today. Fraser didn’t just tear down universal Medibank—he also created a new Medibank: a government-owned private insurer designed to compete with the existing funds.

Medibank Private commenced operations on 1 October 1976, after the Fraser government announced on 8 June 1976 that the Health Insurance Commission would be authorised to offer private medical and hospital insurance nationwide, in direct competition with registered health funds.

One of the key reasons for creating Medibank Private was straightforward: the government believed a state-owned competitor could put pressure on other funds to keep premiums more reasonable.

It was a politically neat compromise. Fraser could step away from universal coverage without abandoning the powerful Medibank brand—and he could still claim he was protecting households by using a government-backed insurer to keep the private funds honest.

Medicare's Birth and Medibank Private's New Role

The Fraser years proved brutal for healthcare access. So when Bob Hawke’s Labor government swept into power in 1983, restoring universal coverage was a priority—and this time the ground had shifted.

When the Hawke government revived the original Medibank model in 1984, it did so under a new name: Medicare. There was very little resistance from the medical profession. The Coalition remained opposed, but it no longer had the same ability to block the policy.

On 1 February 1984, universal coverage returned as Medicare—while Medibank Private continued alongside it.

That’s the split that defines modern Australian healthcare. Medicare became the public universal system. Medibank became the private insurer. Same linguistic root, totally different roles.

And over time, Medibank Private’s role inside government began to change too. In 1997, it was separated from the Health Insurance Commission and established as its own government-owned enterprise.

That move mattered. It meant Medibank Private was no longer just an arm inside a larger agency—it could build its own management, its own systems, and its own identity. Still government-owned, yes. But increasingly able to operate like a commercial business.

Looking ahead, this is one of the quiet prerequisites to everything that follows. By the time Medibank finally reached the share market, it wasn’t being yanked overnight from “public service” to “public company.” It had spent years building the operational habits—and the corporate muscles—that privatization demands.

IV. The Long Stable Years: Building Market Dominance (1984-2009)

Government-Owned Enterprise Takes Shape

For more than two decades, Medibank Private lived in a strange middle ground: it was owned by the government, but it fought every day like a private business—competing with other health funds for members, premiums, and trust. That hybrid identity came with real advantages, like a familiar brand and the implied stability of the Commonwealth behind it. But it also came with constraints: politics was never far away, and every major move sat under a public spotlight.

In the late 1990s, policy shifts in Canberra reshaped the whole industry—and Medibank was perfectly positioned to benefit. Between late 1999 and mid-2000, two big initiatives kicked in: Lifetime Health Cover, which penalized people who waited too long to take out private hospital cover, and the 30% private health insurance rebate. Together, they didn’t just tweak demand. They pushed a wave of Australians into private health insurance.

Medibank rode that wave hard. By the mid-2000s, it covered about 3 million Australians, up from roughly 2 million before those changes. Around 100,000 members had been with the fund since the beginning. It had become the biggest health insurer in the country—and it wasn’t giving that crown back.

The First Privatization Attempts

Then, in 2006, the Howard Coalition government made the next step explicit: if it won the 2007 election, Medibank would be sold via a public float. It didn’t win. Kevin Rudd’s Labor Party had pledged to keep Medibank in government hands, turned that pledge into a campaign issue, and took office.

That episode is the cleanest snapshot of the problem: privatizing a health insurer isn’t like privatizing an airport. Health cover is personal. Millions of people feel like they’re not just customers, but stakeholders—and the idea of selling “their” insurer to investors is a lightning rod.

But even with Labor’s victory, the underlying question didn’t disappear. Inside Medibank, and among policy analysts, it kept coming back: what, exactly, was the government doing owning a private health insurer? The original justification—using a state-owned player to keep the rest of the market honest—looked less convincing as the industry matured. Medibank was already regulated like everyone else. And it wasn’t obvious that public ownership was delivering a distinct benefit to consumers.

The intellectual case for privatization kept building. The politics, though, needed more time.

V. Inflection Point #1: The For-Profit Conversion (2009)

The Rudd Government's Pivotal Decision

In May 2009, Medibank’s story took a sharp turn. The same Labor government that had defended public ownership in 2007 now made a move that permanently changed what Medibank was.

The Rudd government announced that Medibank would become a for-profit business and start paying tax on its earnings. The conversion was completed on 1 October 2009 after approval from the then regulator, the Private Health Insurance Administration Council (PHIAC).

This wasn’t just a legal tweak. For decades, Medibank had lived in that ambiguous space where it competed like a private fund but carried the “not-for-profit” logic of a public institution. Once it went for-profit, the rules of the game became unmistakable: commercial discipline, tax like everyone else, and dividends to its shareholder—still the government, for now.

From this point on, Medibank operated as a government business enterprise under the same regulatory regime as other registered private health funds, but with a new identity. It was no longer primarily a policy tool. It was a business being run, quite deliberately, like one.

And the subtext was hard to miss: this is what you do when you’re getting something ready to be sold.

Strategic Acquisitions: Building Beyond Insurance

With that shift underway, Medibank moved to broaden what it could offer—beyond collecting premiums and paying claims.

In January 2009, Medibank acquired the Wollongong-based insurer ahm (Australian Health Management). In April 2009, it merged with the HSA Group.

The ahm deal was especially telling. Instead of folding it into the main brand, Medibank kept ahm as a distinct, lower-cost option. That gave Medibank a way to compete for price-sensitive customers without dragging down the positioning of the flagship product—an approach that sounds obvious, but signals a company starting to think like a modern consumer business.

Then, in July 2010, Medibank acquired health services provider McKesson Asia-Pacific, bringing it into Medibank Health Solutions. The telephone and online health management programs—healthdirect Australia, Nurse-on-Call, and Healthline—would continue under Medibank.

That acquisition did more than add revenue. It added capability. Telehealth, triage lines, and health management programs were early building blocks for what Medibank would later describe as its “health company” ambition: not just financing care, but delivering and shaping it.

Seen together, the years from 2009 to 2014 were Medibank’s runway to privatization. The corporate structure was being tightened, the commercial mindset made explicit, and the strategy broadened into something investors could underwrite. Medibank wasn’t just a government legacy insurer anymore. It was becoming an integrated healthcare player—on purpose, and on a timeline.

VI. Inflection Point #2: The Record-Breaking IPO (2014)

The Political Path to Privatization

Before the 2010 election, Liberal leader Tony Abbott made a familiar pledge: if the Coalition won, Medibank would be privatized. Labor won instead, and Medibank stayed put. Abbott took the promise back to voters again in 2013—this time, the Coalition won.

On 26 March 2014, Finance Minister Mathias Cormann made it official: Medibank would be sold via an initial public offering in the 2014–2015 financial year.

The decision to go with an IPO, rather than selling Medibank to another insurer, wasn’t just about maximizing price. It was about making the deal possible at all. Medibank was already one of the giants of Australian private health insurance. A trade sale to a major rival risked running straight into the ACCC, because it could have substantially reduced competition.

An IPO solved that problem neatly. Instead of concentrating power, it dispersed ownership across the market. It also gave everyday Australians a chance to buy shares in a brand many of them already paid every month.

The IPO Mechanics and Success

The Medibank IPO became a landmark: the second largest in Australian history, and one of the biggest globally in 2014. It raised about $5.8 billion.

The government set the institutional price at $2.15 a share—above the prospectus’ indicative range of $1.55 to $2.00—but retail investors only paid $2.00. That gap wasn’t an accident. It effectively handed individual buyers an immediate “win,” insulating the privatization from the backlash that can follow when a big public sale feels like it only benefits institutions.

When the dust settled, the government had sold 100% of the company in one shot. Medibank listed on the ASX as MPL on 25 November 2014, with about 440,000 individual shareholders and a market capitalization of A$5.921 billion. At the time, Medibank held roughly a 29% share of the private health insurance market.

It was a clean break—unlike Telstra, which was privatized in stages over years. Overnight, Medibank went from a government-owned enterprise to a public company with a simple mandate: perform for shareholders.

What the Market Was Buying

Investors weren’t just buying a brand. They were buying a dominant player in a tightly regulated market designed to be stable.

Australia’s private health insurance system has built-in guardrails to reduce classic insurance problems like adverse selection, where an insurer ends up with a disproportionately older, higher-claim membership base. Medibank did have an older membership than many competitors, but the industry’s Risk Equalisation Trust Fund helped smooth those differences by redistributing costs between funds.

Medibank also floated with a strong financial position: minimal non-current liabilities, and net assets of A$2.7 billion at the end of the prior financial year, including $0.9 billion in cash.

But the IPO prospectus came with an unspoken footnote: policy risk. Private health insurance in Australia is heavily shaped by government incentives and penalties that push people to participate. Future governments could dial down the rebate, change the Medicare Levy Surcharge settings, or redraw the boundary between public and private care. Even as a newly minted public company, Medibank’s fortunes were still tethered to Canberra—just in a different way.

VII. The Post-IPO Transformation: From Insurer to Health Company (2015-2022)

Leadership and Strategy Evolution

Once Medibank was in private hands, the pace changed. The company didn’t just have to operate like a business anymore—it had to grow like one. And the strategy it leaned into was clear: stop being “just” an insurer, and start becoming an integrated health company.

That shift took shape under CEO Craig Drummond (2016–2021), and then accelerated under David Koczkar, who was appointed Chief Executive Officer effective 17 May 2021.

Koczkar was a signal in human form. He wasn’t a career insurance executive. Before Medibank, he was Group Chief Commercial Officer at Jetstar, responsible for customer and commercial activities across Asia Pacific. He brought more than 25 years of leadership in customer-focused businesses, with earlier experience in strategy consulting and finance.

Putting an airline executive in charge of Australia’s largest health insurer sounded unconventional—and that was the point. It telegraphed how management saw the future: Medibank wasn’t trying to become a hospital. It was trying to become a great consumer company in healthcare, where trust, service, and product design would matter as much as actuarial math.

Chairman Mike Wilkins leaned into that framing, saying the Board was pleased to appoint an executive of Koczkar’s calibre and experience. He credited Koczkar—previously Medibank’s Chief Customer Officer—as a champion for customers who had helped drive major changes across the business, leading to better advocacy, improved retention and customer growth, stronger products and services, and enhanced performance for shareholders.

The Strategic Vision: Beyond Bill-Paying

Underneath the rebrand to “health company” was a simple strategic belief: the classic insurance model—collect premiums, then pay for treatment—only goes so far. If you want to build something bigger and more resilient, you have to move upstream, closer to prevention and ongoing care.

That’s why Medibank launched CareComplete, a program designed to support people living with chronic conditions. It has remained one of the largest chronic disease programs in Australia.

This was exactly the kind of bet insurers love on paper: help members manage conditions like diabetes or heart disease earlier and more consistently, and you can reduce expensive hospital admissions later. Done well, it’s one of the rare plays where the incentives line up—better outcomes for customers, lower costs for the system, and a stronger business for shareholders.

Building the Health Services Division

Medibank didn’t stop at programs and phone lines. It started building real care delivery capability, particularly in primary care—because if you believe prevention matters, you go where prevention actually happens: the GP.

A key step was taking a non-controlling 33.4% economic interest in Myhealth Medical Group (Myhealth), a leading operator of primary care clinics. Founded in 2007, Myhealth delivered more than 2.5 million patient consultations a year. The group had tripled its number of clinics over the previous five years, growing to a network of 86 clinics across New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland, with more than 1,300 health professionals practising within the network—doctors, nurses, and allied health practitioners.

Medibank then increased its investment further, citing the critical role GPs play in prevention, early detection, and community-based support—especially for people living with complex and chronic conditions. It planned to lift its shareholding from 49% to 90% for around $50.8 million.

That stepwise build—from 33.4% to 49% to 90%—captured how Medibank approached vertical integration: not a single dramatic leap, but a series of increasingly confident commitments as the strategic fit proved out.

By the end of 2021, the Medibank that had listed in 2014 looked meaningfully different. Alongside insurance, it was operating telehealth services, chronic disease management programs, GP clinics, and home healthcare services. “Health company” wasn’t just a slogan—it reflected a real broadening of what Medibank did, and how it made money.

But just as that transformation was gaining momentum, Medibank was about to be tested in a way no strategy deck can prepare you for.

VIII. Inflection Point #3: The Cyber Catastrophe (October 2022)

The Attack Unfolds

The breach that would eventually hit nearly 10 million Australians didn’t start with a genius hack. It started with something painfully ordinary.

Before 7 August 2022, an employee of a third-party IT provider contracted by Medibank saved their Medibank credentials to their internet browser profile on a work computer. Those saved credentials then synced to the employee’s personal device. That device was infected with malware. Around 7 August 2022, the malware stole the credentials. And this wasn’t just any login—this person had a Medibank admin account.

Read that again: a password saved in a browser, synced to a personal device, stolen by malware. Small lapse, gigantic blast radius.

On 12 October 2022, Medibank’s administrators detected suspicious activity inside the company’s network. Because of its disclosure obligations, Medibank went public the very next day, on 13 October, saying it had detected “unusual activity consistent with the precursors to a ransomware event”—but also reassuring customers that no sensitive customer data had been accessed.

Medibank took its ahm and international student policy management systems offline and requested a trading halt on the ASX.

With hindsight, that reassurance reads like a tragedy in slow motion. Medibank believed it had contained the incident. But the attackers were already well past the perimeter—and the data was already leaving the building.

The Scale of Devastation

The attacker behind the breach ultimately affected 9.7 million current and former Medibank customers. The stolen information covered the basics—names, dates of birth, addresses, phone numbers, email addresses, Medicare numbers—but the real damage was what sat behind the identity layer: health information tied to medical treatments and claims.

Then came the pressure campaign.

After Medibank refused to pay, the criminals began uploading compressed files to a dark web forum on 9 November, including a dataset with about 800,000 rows from Medibank’s production database. Alongside general treatment information, the attackers curated a separate “naughty list” identifying patients receiving drug and alcohol treatments.

And they didn’t stop there. More dumps followed, designed to maximize shame and fear. A second release identified patients alongside abortion records, non-viable pregnancies, ectopic pregnancies, and miscarriages.

This wasn’t just data theft. It was data-as-weapon. By labeling and segmenting the most stigmatized categories of care, the attackers were trying to turn public exposure into leverage—painful enough that Medibank would have to pay.

The Ransom Decision

By November 2022, the criminals demanded a $10 million ransom, threatening to publish the stolen data within 24 hours if Medibank didn’t comply.

The hacker even posted about the price, claiming it was $10 million, then “discounted” to $9.7 million—framed as about $1 per customer.

Medibank refused to pay. The company said it had taken advice from cyber security experts, including that there was only a limited chance that paying would result in the return of the stolen data. And in the cold logic of incident response, the reasoning is familiar: payment can fund criminal networks, invite follow-on attacks, and still fail to stop publication.

But the human reality was brutal. For millions of customers, the decision not to pay didn’t just mean “no deal.” It meant watching their most private information become a bargaining chip—then a public artifact.

The Security Failures

What made the breach even harder to swallow was that it didn’t expose an impossibly advanced adversary. It exposed fundamentals.

Among the most glaring issues: Medibank did not enforce multi-factor authentication (MFA) on remote access systems, despite the sensitivity of the data involved. Credential management failed—saving credentials in a browser that synced to a personal device made compromise far easier. And detection and response fell short: attackers were able to remain in the environment long enough to exfiltrate 520 GB of data.

Regulators later sharpened the indictment. According to the OAIC, Medibank was aware of serious deficiencies in its cyber security and information security framework for at least 18 months before the breach—particularly the absence of MFA.

And the warnings weren’t vague. A Datacom report in mid-2020 identified the lack of MFA as a “critical defect,” noting it wasn’t activated for privileged and non-privileged users. A KPMG report in August 2021 also found MFA was not in place for privileged users accessing particular systems.

Two separate external reviews. Two separate alarms. Same unresolved vulnerability. In that light, the breach didn’t feel like bad luck. It felt preventable.

Market and Regulatory Fallout

The market response was immediate and punishing. Medibank’s share price fell sharply after news of the breach, dropping from AUD 3.51 to AUD 2.87—an 18% fall since 19 October.

That decline erased billions in market value in a matter of weeks. And for a company positioning itself as a trusted “health company,” the reputational hit may have been even more damaging than the financial one.

The government response escalated too. Australia imposed cyber sanctions connected to the breach—the first time the country had done so, and the first time it sanctioned not just individuals but those providing the infrastructure that makes these attacks possible. Sanctions were imposed on the Russian entity ZServers and five Russian cybercriminals: ZServers owner Aleksandr Bolshakov, and employees Aleksandr Mishin, Ilya Sidorov, Dmitriy Bolshakov, and Igor Odintsov.

Those sanctions followed earlier action in January 2024, when the government sanctioned Aleksandr Ermakov for his role in the Medibank Private data breach.

It was an unusually forceful response, reflecting how severe the attack was—and how seriously Australia was beginning to treat cybercrime as something closer to international threat than mere fraud. But for affected customers, sanctions didn’t rewind the internet. The data was out. And Medibank now had to rebuild trust in a world where trust, once lost, is almost impossible to fully buy back.

IX. Recovery and Reinvention: The Path Forward (2023-Present)

Rebuilding Trust and Security

After the breach, Medibank had to do two things at once: rebuild its defences and keep the business running.

That meant higher ongoing operating costs as security became a permanent line item, not a one-off project. On top of that, the company booked $39.8 million in non-recurring costs tied to IT security uplift, plus legal and other expenses related to regulatory investigations and litigation arising from the 2022 cybercrime event.

And the legal and regulatory shadow didn’t just disappear with the headlines. Medibank continued to face litigation and investigation. In its own words: “The group was subject to a cyber crime in the prior financial year, which resulted in a data breach.” It flagged that “specific contingent liabilities” might flow from that event, and that they could impact the group.

The biggest formal process was the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) investigation, launched on 1 December 2022. The question at the heart of it was simple and brutal: whether Medibank took reasonable steps to protect personal information from unauthorised access and misuse.

Together, the OAIC process and associated class actions created a category of risk no one could neatly price. Medibank said it was defending all proceedings, but also acknowledged the reality: the outcomes, and any potential financial impacts, were unknown.

The Health Company Strategy Accelerates

A lot of companies, after a breach like this, go into a crouch. Medibank didn’t. Instead of shrinking its ambitions to “just get back to normal,” it leaned harder into the idea that it wasn’t only an insurer.

Medibank’s thesis was that Australia’s healthcare system is world-class, but under real strain—and that the next era requires a shift in how care is delivered. In the company’s own framing: it’s time to move from treatment to prevention, from hospital to community, from analogue to digital, and from generic to personalised care. Technology, and “connecting health,” would be the accelerant.

Those “four big shifts” became the story Medibank told itself—and investors—about what comes next:

- Treatment to prevention: Don’t just fund sickness. Invest in keeping people well.

- Hospital to community: Push care into homes, clinics, and local settings to avoid expensive admissions.

- Analogue to digital: Build digital experiences that enable new models of care and engagement.

- Generic to personalised: Use data to tailor health support to individual needs.

In other words: the breach didn’t end the transformation narrative. It forced Medibank to prove it could pursue it while under pressure.

2024 Results and Future Ambitions

By the year ending 30 June 2024, Medibank was showing it could absorb the shock and still perform. Group revenue from external customers rose 4.7% to $8.18 billion. Health insurance operating profit increased 6.3% to $692.3 million.

Group operating profit—excluding COVID-19 impacts—was up 7.9% to $699.8 million. Under the hood, the split mattered: the core Health Insurance business grew steadily, while the Medibank Health segment profit jumped 36.7%, including the contribution from Medibank’s increased investment in Myhealth.

In FY24, Medibank described itself as supporting around 4.2 million customers and delivering more than 4 million health interactions. The identity it was selling—internally and externally—wasn’t “we pay claims.” It was “we help people live better, healthier lives,” through more choice, better access, and more value from the health system.

And that growth gap between the two engines told you where management believed the future was. Insurance was the foundation. Health services was the upside.

FY30 Strategic Ambitions

In late 2025, Medibank set targets that turned the “health company” idea into hard numbers.

It said it was targeting at least $200 million in annual earnings from its health segment by FY30, up from $76.7 million reported in FY25. It also set a goal to grow policyholder market share each year—moving from 26.5% to at least 26.8% by FY30.

And then there was the biggest ambition in plain language: double the number of people it engages with on health and wellbeing, to around 10 million Australians by the end of the decade.

CEO David Koczkar positioned this as the continuation of a long build: “Over the last decade, we have invested more than $300 million to grow as a health company.” The message was that the company wasn’t experimenting anymore—it was committing, with milestones.

Strategic Partnerships and Technology Investment

If Medibank’s strategy required becoming a better digital health business, it also required humility about how to get there. Building everything in-house is slow and expensive, especially in healthcare tech.

That’s why Medibank announced a three-year strategic partnership with League, a healthcare consumer experience platform. The goal: a more personalised, more engaging experience for Medibank’s 4.2 million customers, aligned to its vision for Australia’s health and wellbeing by 2030.

League’s data- and AI-driven platform would be embedded into Medibank’s digital capabilities, serving up integrated “next-best actions” and content for customers. It was also League’s first customer outside North America.

Alongside the software partnerships, Medibank kept building real-world delivery capacity—especially in primary care. Myhealth, where Medibank bought a 33% stake in 2021 for $63 million and later moved to 90% ownership, had grown into a network of 105 clinics across eastern Australia.

Then in November 2025 came another major step: the $159 million acquisition of Better Medical, a network of 61 GP and medical clinics across Victoria, Queensland, South Australia and Tasmania. Better Medical had operated since 2015 and included around 800 doctors, nurses, and allied health practitioners.

Add that to Myhealth, and the direction of travel was clear: Medibank wasn’t just trying to influence healthcare from the outside as a payer. It was assembling the scale to participate in delivering it.

X. The Australian Private Health Insurance Landscape

The Regulatory Environment

To understand why Medibank looks and behaves the way it does today, you have to understand the world it operates in. Australian private health insurance isn’t a free-for-all marketplace. It’s one of the most regulated consumer industries in the country—built to protect customers and keep the system stable.

At the center is APRA, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority. APRA’s job is to make sure health funds stay solvent, and it publishes deep, regular reporting on the industry, including financial statements for individual funds. At the same time, the Department of Health regulates the pricing and features of health insurance products.

The result is a very particular kind of competition. Insurers can’t just cut prices to win share the way airlines or telcos might—premium increases require government approval. Risk-pooling mechanisms are designed to stop insurers from “cherry-picking” only healthier customers. And the government itself shapes demand through policy settings that nudge, and sometimes shove, people into holding cover.

In other words: Medibank competes hard, but it’s playing on a field with a lot of lines painted on it.

Government Incentives

Private health insurance in Australia isn’t only a product purchase. For many households, it’s also a tax decision.

Most Australians with private health insurance receive a government rebate that reduces the cost of their premiums. The rebate varies depending on age and income. Then there’s Lifetime Health Cover: if you buy hospital cover after the 1 July following your 31st birthday, you pay an additional loading on your premium, and it increases the longer you wait. And if you earn above certain income thresholds and don’t hold private hospital cover, you may be hit with the Medicare Levy Surcharge at tax time.

Put together, these settings create a simple behavioral funnel. The rebate is the carrot. The surcharge is the stick. And Lifetime Health Cover is the “you’ll regret it later” penalty. For millions of people—especially higher earners—the rational move is to maintain cover, even if they don’t love the product.

The government’s reasoning is also explicit: people with private cover contribute to their own healthcare costs and reduce pressure on the public system, particularly public hospitals.

For insurers, that’s structural support. But it comes with a catch: it’s also political risk. If a future government meaningfully changes the rebate, the surcharge, or the Lifetime Health Cover rules, participation can move quickly—and so can the economics of the entire industry.

The Competitive Landscape

This is a big industry, but it’s not a fragmented one. Australia’s private health insurance market is highly concentrated, with the top five insurers—Medibank, BUPA, NIB, and the not-for-profits HCF and HBF—accounting for 79% of all premium income.

And within that, it’s even more top-heavy. Medibank is the largest player at 27.1% market share, followed by Bupa at 24.9%. Between the two of them, they control more than half the market.

The profit picture mirrors that concentration. Medibank, Bupa and NIB made a combined $1.7 billion in profits, while the remaining 27 private health insurers made a combined $545 million.

That creates a set of trade-offs that defines Medibank’s strategy. As the leader, it benefits from scale—brand recognition, operating leverage, and bargaining power. But it’s also a mature market, which limits easy growth. And when you’re already the biggest, every competitive move attracts more scrutiny.

There’s also a structural split in the biggest players. HBF and HCF are the only large not-for-profit funds. Medibank and NIB are listed, dividend-paying companies. In a concentrated industry, that for-profit versus not-for-profit divide matters. The for-profit players took the lion’s share of profit, with the top three accounting for 59% of pre-tax profit.

So this is the playing field Medibank is trying to win on: heavily regulated, politically sensitive, concentrated at the top, and shaped as much by Canberra’s incentives as by any advertising campaign.

XI. Bull Case, Bear Case, and Competitive Analysis

Bull Case: The Health Company Premium

Medibank’s bull case is simple: the market stops valuing it like “just” an insurer.

If Medibank can prove that its health services and preventative programs actually improve outcomes and, crucially, reduce claims over time, then it earns the right to trade at a premium to pure-play insurers. It’s the classic move from payer to platform: you’re not only paying for care after the fact, you’re helping shape care before it gets expensive.

One useful lens here is Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework:

- Scale Economies: As the largest player, Medibank can spread technology spend and administrative overhead across a huge member base, and it has meaningful leverage when negotiating with hospitals and providers.

- Network Effects: The more GPs, clinics, and services Medibank connects into its ecosystem, the more valuable that ecosystem becomes to customers who want coordinated, end-to-end care.

- Switching Costs: If your insurer is also tied into your GP network, your chronic disease program, and your health history, leaving becomes more than a price decision. It becomes friction.

- Cornered Resource: The Medibank brand is unusual in Australia: a legacy name with government roots, now operating at scale. Pair that with its position in telehealth and primary care, and it’s not something competitors can quickly copy.

- Counter-Positioning: Insurers built around a pure claims model may struggle to match Medibank’s investment in care delivery without disrupting their own economics and operating model.

The League partnership, the expansion of Myhealth, and the acquisition of Better Medical all reinforce the same idea: Medibank is trying to build capabilities that aren’t easily replicated by companies that only underwrite risk and process claims.

And if the health services segment really does grow to $200 million in earnings by FY30, as Medibank has targeted, it stops being a side business. It becomes a meaningful contributor to the company’s value, and the transformation story starts to look real.

Bear Case: Structural Challenges and Execution Risk

The bear case is that this is still a health insurer in a political, highly regulated market—and it’s trying to transform itself while carrying a heavy trust deficit from the breach.

There are three big risks.

1. Policy Risk: Private health insurance in Australia is partially policy-engineered demand. Rebates and tax penalties help keep people insured. If a future government reduces that support—especially under budget pressure—membership could fall across the industry. As the largest player, Medibank would wear more than its share of that downside.

2. Competition and Margin Pressure: Premiums are rising at a time when households are sensitive to every bill. As of 1 April 2025, premiums increased by an industry average of 3.73%, and Medibank, Bupa, HCF and nib all raised premiums by more than the average. In a cost-of-living squeeze, that’s an invitation for members to downgrade, switch to cheaper policies, or leave private cover entirely.

At the same time, Medibank is squeezed from the other direction. Private hospitals are under pressure, and there are calls for insurers—especially larger, profitable ones—to contribute more to the healthcare system. That’s a potentially lose-lose dynamic: if Medibank holds firm on costs, hospitals push back; if it pays more, margins compress, and premiums may rise further.

3. Cyber and Legal Overhang: The 2022 breach didn’t end when the data was published. It created a long tail of legal, regulatory, and reputational risk. Medibank is defending the proceedings it faces, but adverse outcomes from the OAIC investigation or class actions could still mean significant penalties and costs. And even without a catastrophic legal result, the erosion of trust could weigh on retention for years.

Another lens: Porter’s 5 Forces.

- Threat of New Entrants: Low. Regulation, capital requirements, and the need for scale and brand make it hard for new players to enter meaningfully.

- Supplier Power: Moderate to high. Hospitals and specialists have real leverage, and consolidation can amplify it.

- Buyer Power: Moderate. Individual customers don’t negotiate pricing, but government-regulated products make comparison shopping easy, and switching is always an option.

- Threat of Substitutes: Moderate. Medicare is a real substitute for many services, and some customers may decide to self-insure, especially for extras.

- Competitive Rivalry: High. A concentrated market with large incumbents fighting hard for share.

Key Performance Indicators to Watch

For long-term investors trying to judge whether the transformation is working, three KPIs matter most:

-

Policyholder Market Share: Medibank’s target of 26.8% by FY30, up from roughly 26.5%, looks modest. But holding or growing share in a mature, tightly contested market is difficult. Any sustained share loss would be a warning sign.

-

Medibank Health Segment Profit: This is the “proof” metric for the health company strategy. The target of $200 million by FY30, from $76.7 million in FY25, implies very strong growth. The question is whether that growth is steady and repeatable, or dependent on one-off steps like acquisitions.

-

Customer Retention Rate / Net Promoter Score: After the breach, trust is strategy. Retention and advocacy metrics, including the company’s reported Service NPS, are a real-time read on whether reputational damage is fading—or becoming permanent.

XII. Myth vs. Reality: Fact-Checking the Consensus Narrative

Myth 1: Medibank is just a health insurance company with modest growth prospects.

Reality: Insurance is still the engine that pays the bills. But Medibank has spent the past decade quietly building a second one. It now has real capability in telehealth, primary care through its positions in Myhealth and Better Medical, chronic disease management, and corporate health services. That Medibank Health segment has been growing much faster than the core insurance book, and management has put big FY30 targets behind it. The strategy isn’t to win by being the cheapest insurer. It’s to differentiate through vertical integration—owning more of the customer’s healthcare journey, not just the claim at the end of it.

Myth 2: The cyber breach was a one-time event that's now behind the company.

Reality: The headlines may have moved on, but the consequences haven’t. Legal and regulatory proceedings continue. Medibank says it’s defending all proceedings, while also acknowledging that the “outcome and any potential financial impacts… are currently unknown.” Security uplift is now a permanent operating reality, not a temporary project—adding ongoing cost and complexity. And the hardest part to model is trust: reputational damage doesn’t show up cleanly in a single year’s results, but it can linger in customer retention and brand perception for a long time.

Myth 3: Government ownership heritage means Medibank is less commercially sophisticated than competitors.

Reality: That’s an old picture of a very different company. Medibank has been operating as a for-profit enterprise since the 2009 conversion, and it has been publicly listed since late 2014. In that time, it has made acquisitions, built out new business lines, and run with the cadence and expectations of a modern listed company. Whatever advantages or constraints came with government ownership, that chapter is now history—not destiny.

Myth 4: Australian private health insurance is a structurally declining industry.

Reality: It’s under pressure, but it’s not collapsing. Roy Morgan’s data—drawn from in-depth personal interviews with more than 1,000 Australians each week—suggests that, despite cost-of-living strain, a majority of Australians still maintain private health insurance coverage (57.2%). And the system itself is built to support participation: the Medicare Levy Surcharge and Lifetime Health Cover penalties push many households toward keeping cover. Premium growth may ebb and flow, and value perceptions will keep getting tested—but the industry isn’t simply in structural decline.

XIII. Conclusion: A 50-Year Journey and the Road Ahead

Medibank’s story is really a story about Australia—about what the country expects from healthcare, what it’s willing to subsidize, and how politics can reshape an entire industry.

It started as Whitlam’s universal coverage experiment. It was then dismantled and reshaped under Fraser—yet spun out as Medibank Private, a government-owned competitor meant to keep the market honest. Over the following decades it was separated, professionalized, and commercialized, until the final pivot: a blockbuster privatization in 2014 that turned a public institution into a shareholder-owned company. And just as it was trying to reinvent itself again, the 2022 cyber attack dragged the brand through one of the most painful breaches Australia has ever seen.

What’s striking is not that Medibank changed. It’s that it kept surviving the change.

Today’s Medibank is not the same organization that once existed as a government instrument, or even the one that first arrived on the ASX. Under David Koczkar, it’s been explicit about where it wants to go: from “health insurer” to “health company.” That’s not just marketing. The moves—into primary care, telehealth, chronic disease programs, and digital health platforms—are real attempts to differentiate in a market where traditional insurance products are hard to make meaningfully different.

But the risks are just as real. The breach still casts a long legal, regulatory, and reputational shadow. Price-sensitive customers can always downshift to cheaper alternatives. And the entire private health system remains, by design, partly engineered by government policy—rebates, penalties, and rules that a future parliament can rewrite.

So for long-term investors, Medibank sits in an unusual place: a dominant player in a heavily regulated, high-barrier industry, trying to earn a new kind of growth by vertically integrating into care itself. The open question is the one that will define the next decade: does the health services strategy become big enough—and profitable enough—to change what Medibank fundamentally is? Or does the market keep valuing it like what it has always been at its core: a mature insurance business with a broader set of ambitions?

“Our 2030 Vision is to create the best health and wellbeing for Australia. We connect people to a better quality of life in every moment. We create access, choice and control for everyone, and together lead change for a stronger health system.”

The infrastructure is being built. The acquisitions are being made. The strategy is clear. Now comes the hard part: execution—under scrutiny, in a political industry, with trust as the main currency.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music