Mirvac Group: Australia's Urban Reimaginer

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

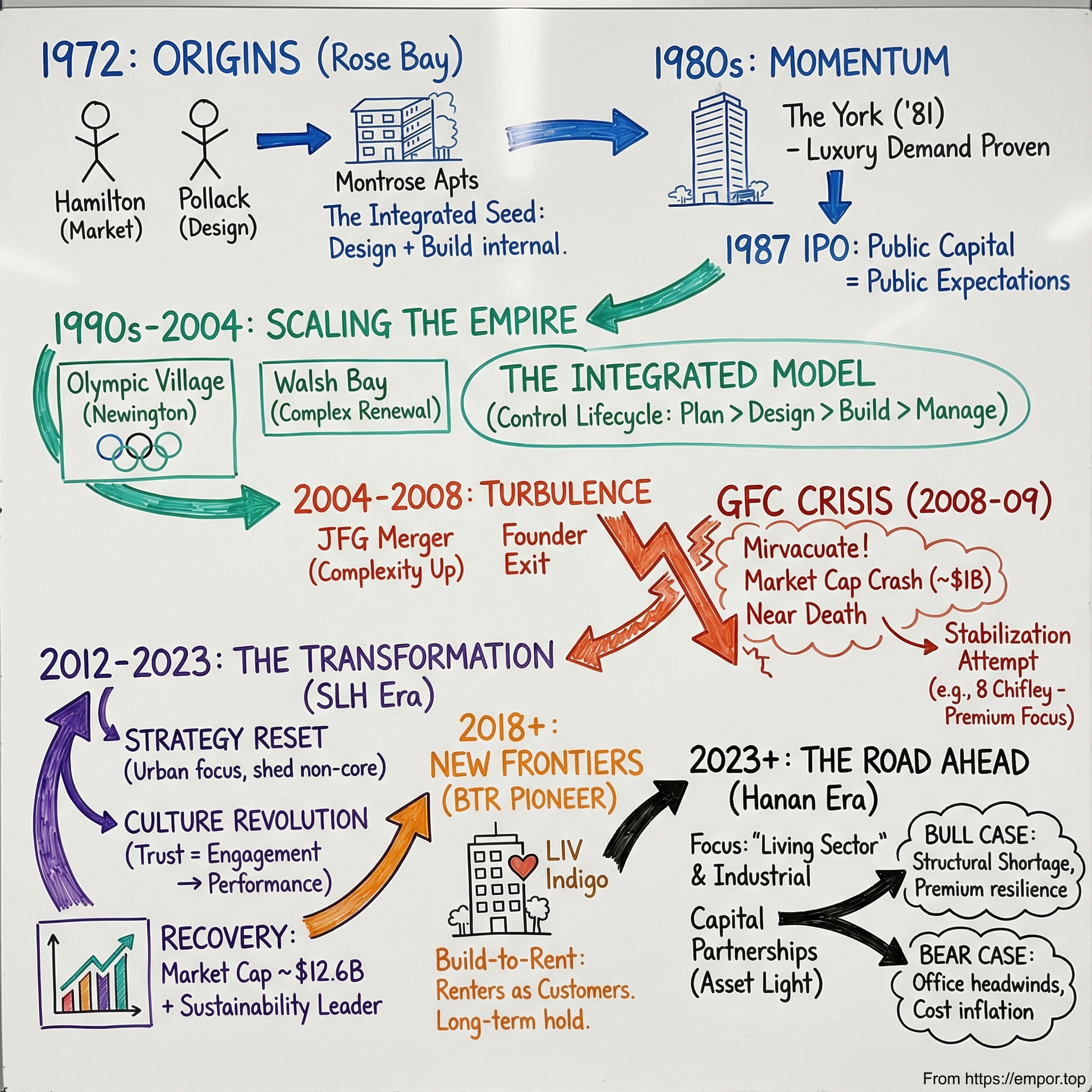

Picture Sydney’s eastern suburbs in 1972: weatherboard homes baking in the sun, corner milk bars still doing a roaring trade, and a city straining to house a growing population as post-war immigration reshaped Australia’s urban map. On a quiet street in Rose Bay, a new block of just twelve apartments went up. It was called Montrose—small, unglamorous, and easy to miss.

And yet, in hindsight, Montrose is the opening scene of something much bigger: the origin point of Mirvac.

Mirvac was founded that year by Henry Pollack and Robert Hamilton. Together they blended two complementary instincts: Pollack’s feel for the market and what people would pay for, and Hamilton’s eye for design and how buildings should actually work. That combination—taste plus execution—would become a recurring theme in Mirvac’s rise.

Even the name “Mirvac” has the kind of half-explained, passed-down quality that attaches itself to companies that grow beyond their beginnings. Whatever its precise origin, it quickly came to stand for a certain standard: thoughtful design, high build quality, and, eventually, something rarer in property than it sounds—control. Not just of a single project, but of the whole lifecycle: planning, development, construction, marketing, and long-term ownership.

Today, Mirvac is an ASX-listed property group with an integrated asset creation and curation capability. It owns and manages assets across office, retail, industrial, and living, with around $22 billion of assets under management. Alongside that investment portfolio, it runs an active development business spanning commercial and mixed-use and residential, with a pipeline of roughly $29 billion.

But the real story isn’t the scale—it’s the path. Between a modest Rose Bay apartment block and a modern, diversified property platform sits a sequence of hard pivots and high-stakes moments: a founder exit that reshaped the company, a Global Financial Crisis that nearly capsized it (with analysts circulating reports titled “Mirvacuate!”), and then a transformation under a CEO who arrived to a company with staff engagement in the basement and left it not only thriving financially, but also celebrated globally for culture and gender equity.

Along the way, Mirvac also helped create a new category in Australian real estate—build-to-rent—changing what “home” can look like when the landlord is also the developer and long-term operator.

That’s our roadmap. We’ll dig into why the founder went looking for a merger partner, how Mirvac’s integrated model became a real competitive edge in an industry often dismissed as “just real estate,” and why culture—done properly—can be a moat, not a poster on a wall. And we’ll ask the question that matters for any first mover: when you invent an asset class, can you keep the advantage once everyone else arrives?

For investors and business builders, Mirvac is a particularly rich case study: a company that tries to balance two different engines at once—the steady, compounding income of a property portfolio, and the riskier, higher-upside work of development—while sustainability expectations from tenants, regulators, and capital partners keep rising.

II. Origins: The Hamilton-Pollack Vision (1972–1987)

Bob Hamilton didn’t set out to build cities. He grew up in Chatswood, finished high school, and did what ambitious young Australians did: he went to university—initially to study medicine. But the fit was wrong from the start, and he later explained why with disarming honesty.

“I’m actually dyslexic and had trouble learning at school,” he said. “But as I got older, I seemed to overcome that… And I thought I’d have a shot at doing medicine. Unfortunately, I didn’t do chemistry or physics at high school and first year medicine was all about chemistry, physics, botany and zoology. So, I got the distinction in zoology and a credit in botany and failed in both physics and chemistry.”

So Hamilton pivoted. He went into real estate—and found something that suited him far better than textbooks ever had: people, preferences, and the messy reality of what buyers actually wanted.

That’s where Henry Pollack enters. If Hamilton’s gift was the market—positioning, pricing, and demand—Pollack’s was the product: concept, design, and building. The combination was unusually complete for a young development partnership, and it didn’t begin in 1972. The two had already been working together through the 1960s, proving—project by project—that when you pair sales instinct with design and delivery, you can build something that feels inevitable in hindsight.

In 1972, they made it official and launched Mirvac.

From day one, design wasn’t something Mirvac “cared about.” It was embedded in the structure of the company. Mirvac Design—originally Henry Pollack & Associates—operated as an in-house architectural practice from the start. Instead of outsourcing the most important part of the product, Mirvac pulled it inside. That decision would become a cornerstone of what it later described as its integrated model: keeping the critical capabilities under one roof so quality didn’t get value-engineered away halfway through the process.

The early projects were shaped by the place they knew best: Sydney’s eastern suburbs. Harbour air, expensive land, and buyers who cared about light, views, and layouts that felt intentional. Mirvac built apartments that tried to elevate the category—because Hamilton understood a subtle truth about Australia at the time: plenty of people wanted apartment living, but only if the apartments were good enough to compete with the dream of a detached house.

That thesis hit its breakout moment in 1981 with The York: a 150-apartment tower that became the first new luxury residential high-rise in Sydney since The Astor more than fifty-five years earlier. The response was electric. Potential buyers queued for hours for their shot at one of those 150 apartments. Then it sold out—in four hours.

That four-hour sell-out did more than create headlines. It proved there was real, unmet demand for high-quality urban living, and that “quality” wasn’t just a slogan—it was a way to expand the market. Hamilton’s bet was that Australian buyers could be converted to apartments, but only if the product earned the premium. Mirvac wasn’t simply competing for share; it was trying to change minds.

Over the decades that followed, Hamilton would remain a defining force. Robert Hamilton AM was Mirvac’s joint founder and served as Managing Director for more than 30 years, until 2005. Under his leadership and with an unwavering focus on design and quality, Mirvac developed around 30,000 homes, including major, era-defining projects like Sydney’s Olympic Village, Walsh Bay, and Melbourne’s Beacon Cove.

In 1987, Mirvac took another leap: it listed on the ASX, floating with $120 million in shares. Around the same period, Raleigh Park became a statement of what Mirvac increasingly wanted to do—build not just buildings, but communities. Built around a central green space with inward-facing dwellings and strong visibility from the street, it was designed with community at its core. It became the first major community title development in New South Wales, and Mirvac even helped draft the legislation. That blueprint would go on to shape Mirvac’s masterplanned communities for years—projects like Waverley Park, Newington, and Beacon Cove.

The IPO changed Mirvac’s operating reality overnight. Capital became more available, but so did scrutiny. Mirvac was no longer just answering to its founders’ instincts; it was answering to shareholders who wanted both a reputation for quality and consistent returns. That tension—between long-term placemaking and short-term earnings expectations—would keep resurfacing in different forms throughout the company’s history.

Still, Hamilton’s core edge remained remarkably simple, and surprisingly rare: patience. Property rewards it, but it also tempts you to abandon it. Development cycles take years, and the real verdict arrives decades later, when a project either becomes a beloved part of the city—or a regret everyone has to live with. Hamilton’s willingness to prioritise design over speed helped create what people later called “The Mirvac Difference”: a brand premium that, once earned, stayed earned long after the cranes disappeared.

III. Building an Integrated Empire (1987–2004)

The IPO was a line in the sand. Mirvac had started as a Sydney apartment developer with a reputation for taste and build quality. Now it had public capital behind it—and public expectations riding on top.

Over the years that followed, Mirvac stretched out beyond the eastern suburbs and began assembling what it would later call its integrated platform. The corporate structure evolved too. In 1999, Mirvac Limited merged with a stapled collection of trusts to form the modern Mirvac Group. In plain English, it linked the development company and the property trusts together so investors could own a single “stapled” security that captured both sides of the machine: the lumpy, high-upside development profits and the steadier investment returns from owning and managing finished assets. It was a common Australian property structure—but for Mirvac, it was also an organisational commitment to do more than just build and sell.

The projects of this era are what really made that real.

The signature assignment wasn’t an office tower or a balance-sheet manoeuvre. It was the Sydney Olympic Village.

In the mid-1990s, Mirvac—alongside joint venture partner Lendlease—took on the job of designing and constructing the residential development that would house about 16,600 people for the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games. But the brief wasn’t “build a village.” The real brief was: build a suburb that happens to host the world for a few weeks, and then has to work for decades after the closing ceremony. That meant long-term planning, real infrastructure, and the kind of decision-making that rewards builders who think like owners.

Newington, the community that emerged from the Olympic Village, went on to become known as Australia’s first “solar suburb.” It also became an awards magnet, collecting an unprecedented thirty-six major building, architectural, and design awards—and turning into a reference point for urban developments well beyond Australia.

And the execution was brutally time-bound. Mirvac had around three years to deliver. Hamilton later recounted the scale with unmistakable pride: thousands of permanent dwellings, temporary accommodation, and the supporting facilities needed to make a small city function—delivered on a deadline that didn’t move.

If the Olympics proved Mirvac could build at scale, Walsh Bay proved it could do something harder: take a complicated, historically sensitive piece of waterfront infrastructure and turn it into a place people actually wanted to be.

Walsh Bay, completed in the early 2000s, was one of Australia’s largest urban renewal projects. It transformed deteriorating and under-used wharves, sheds, stores, and streets into a mixed precinct of homes, retail, commercial space, and culture—including a theatre. The development won a long list of industry recognition, including the Royal Australian Institute of Architects’ Walter Burley Griffin Urban Design Award.

Under the hood, it was engineering theatre. Hamilton loved the technical challenge of building over the water. The car park alone required extreme choreography—built and then pushed down into the water before the pier went on top. Layer in heritage constraints and historical overlays, and it became exactly the kind of project that punishes anyone who treats development as a simple commodity business.

But Mirvac didn’t just pull it off. It turned it into an event. Hamilton recalled selling about $400 million worth of real estate in a single day.

These weren’t isolated wins. They were expressions of the same philosophy Hamilton and Pollack had baked in from the beginning: control the whole lifecycle. Mirvac wasn’t just buying completed buildings like a traditional REIT. It was finding sites, planning precincts, designing the product, building it, leasing it, and then managing it. That vertical integration raised the stakes—if you get it wrong, you don’t just lose a margin, you inherit the problem—but it also gave Mirvac something most property companies could never truly claim: quality control end-to-end, and the ability to create assets that fit its own portfolio, not someone else’s leftovers.

By 2004, Hamilton had spent more than three decades building Mirvac into a national platform. But the pace had a cost, and the strain was starting to show. The next phase wouldn’t be a gentle handover. It would be a major merger, a new CEO, and—unbeknownst to almost everyone at the time—the oncoming storm of the global financial crisis.

IV. The James Fielding Merger & Founder Exit (2004–2008)

By 2004, Bob Hamilton was running into the dilemma that hits a lot of founders: the company keeps getting bigger, but the founder’s capacity doesn’t. Years of long hours and constant travel were catching up with him, and his health was deteriorating. Mirvac needed a succession plan that wasn’t just a name on an org chart.

So Hamilton went looking for a partner.

That year, he approached Greg Paramor, the chief executive of James Fielding Group (JFG), about a merger. JFG was a fast-growing real estate funds manager, and Mirvac’s board saw it as a strong fit: Mirvac had deep development and asset-creation capability; JFG knew how to raise capital and run investment vehicles.

In October 2004, JFG shareholders approved the merger. In January 2005, it closed. The $478 million deal lifted Mirvac’s investment development pipeline to $2.3 billion. Six months later, Hamilton officially retired.

Paramor, for his part, wasn’t some passive seller. He was a recognised operator in Australian property, and JFG’s growth story was the reason Mirvac came calling in the first place. Paramor and Leaver had set up the listed James Fielding Group in 2001, and in its first year they delivered a 447 per cent increase in net profit and grew funds under management to $1.5 billion. JFG wasn’t even three years old when Mirvac agreed to pay $478 million for it—and, crucially, bring Paramor and his team into the driver’s seat.

Paramor later described it bluntly: Mirvac came to them. The people who’d built Mirvac—especially Hamilton—wanted to retire, “plain and simple.” He said it wasn’t on his agenda. He’d even been thinking about stepping back himself, handing over to his number two, and taking things easier. And he was “ridiculously too young,” in his own words, to be the natural heir to a company like Mirvac.

But that’s exactly what happened.

The merger brought together two respected management teams—but it also created the kind of situation that can look neat on a slide and messy in real life. This wasn’t just an acquisition of assets; it was a blend of two different operating styles. JFG brought funds management expertise and a different culture. Mirvac had three decades of development DNA, and a quality-first ethos that traced right back to Hamilton and Pollack.

Mirvac’s leadership sold the strategic rationale clearly. When the deal was announced on 12 October, chairman Adrian Lane said in an ASX announcement that the JFG acquisition would give Mirvac access to JFG’s $1.5 billion investment development pipeline and lift Mirvac’s own pipeline to $2.3 billion. Hamilton added that Mirvac’s investment property portfolio would be complemented by JFG’s $565 million in assets.

On paper, the logic was compelling: pair Mirvac’s ability to create high-quality assets with JFG’s capital-raising and funds platform, and you get a more powerful integrated machine.

In practice, it also made Mirvac’s already-diversified structure even more complex. Paramor ran Mirvac for four years, then stepped down in 2008—just as storm clouds were gathering across global markets.

The U.S. housing market had already cracked. Credit was tightening. And in September 2008, Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, turning a downturn into a full-blown global financial crisis. Australian property—long viewed as safer, and far from American subprime—was about to learn how brutally interconnected capital markets had become.

Leadership timing matters in property because the business runs on long cycle times. Decisions made years earlier are hard to unwind quickly. Paramor’s era broadened Mirvac’s scope. The next CEO would inherit that complexity at exactly the moment the financial system started to convulse.

V. Crisis: The GFC Near-Death Experience (2008–2012)

Nicholas Collishaw, a former JFG executive, took over as CEO in August 2008 after Greg Paramor departed. He’d barely had time to settle into the chair before the floor gave way. A month later, Lehman Brothers collapsed, and what had been a tightening credit market turned into a full-blown global financial crisis.

Property companies were hit especially hard. Their assets were real, but they were also illiquid. Their balance sheets were often geared. And when tenants get nervous and lenders get strict at the same time, the whole machine seizes up.

For Mirvac, it was worse than just a cyclical downturn. The company had grown into a sprawling, highly diversified structure—meant to smooth risk, but now exposing it to multiple shocks at once. And the market reaction was brutal. By March 2009, Mirvac’s market capitalisation had fallen to around A$1 billion, wiping out billions in value.

One analyst note captured the mood so perfectly it became legend: “Mirvacuate!” It wasn’t just a pun. It was the professional investor class openly asking whether Mirvac would make it through.

Inside the company, Collishaw was trying to do two things at once: keep the ship afloat, and quietly position it for what came after. Whatever the internal politics that later swirled around his tenure—Collishaw would argue his results didn’t justify how abruptly his time ended—what’s clear is that the business stabilised. And he made a bet that would help redefine Mirvac’s future: if you were going to own commercial property through cycles, it had to be the kind that tenants fought to stay in.

That conviction showed up in 2010, when Mirvac embarked on the redevelopment of 8 Chifley Square in Sydney. The building opened in 2013, designed by the late Lord Richard Rogers and Lippmann Partnership, and it went on to win a range of awards—cementing Mirvac’s reputation not just as a developer, but as a creator of premium commercial assets.

8 Chifley was meant to be more than an office tower. Mirvac and the design team framed it as a statement of environmental leadership—what architect Ed Lippmann described as a “flagship development for good corporate citizenship.” The premium-grade, 34-storey building in the heart of the CBD was owned jointly by Mirvac Property Trust and K-REIT Asia, with engineering services provided by Arup.

Making that kind of commitment in the shadow of a financial crisis can look like recklessness. For Mirvac, it was conviction: a belief that top-tier, sustainable assets would outperform when everything else was being repriced, and that Mirvac’s integrated model—designing, delivering, and owning the outcome—was exactly the advantage it needed.

8 Chifley later achieved a 6 Star Green Star Office Design v2 rating, representing “World Leadership” in environmentally sustainable design, and a 5 Star NABERS Energy rating. The point wasn’t just the plaques. It was the signal: Mirvac intended to compete at the top of the market, and to do it with sustainability and quality as non-negotiables.

The GFC left scars, but it also left clarity. Mirvac learned—painfully—that diversification without focus can be its own kind of fragility. That truly high-quality assets hold up when commoditised ones don’t. And that balance sheet strength buys you the right to make counter-cyclical moves when everyone else is retreating.

Those lessons would become the foundation for the next era—because the turnaround that followed wasn’t just financial. It was strategic, cultural, and, in many ways, existential.

VI. The Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz Transformation (2012–2023)

Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz’s arrival at Mirvac didn’t feel like the start of a clean new chapter. It felt like a rupture.

Two-and-a-half months after being abruptly removed as CEO, Nicholas Collishaw told the Australian Financial Review he was still waiting for a real explanation. He described the whole episode as “bizarre.” He said he was informed on the morning of 15 August—the same day Mirvac notified the ASX, and the same day it named Lloyd-Hurwitz as his successor. Collishaw’s last day was 31 October. Lloyd-Hurwitz stepped into the role immediately after, inheriting not only a fragile post-GFC business, but a leadership transition that had already spooked the market and rattled the organisation.

In 2012, she was appointed chief executive officer and managing director of Mirvac. And she brought a background unlike any previous Mirvac CEO: international funds management and institutional real estate, with experience at LaSalle Investment Management, MGPA, Macquarie Group, and Lend Lease, working across Australia, the US, and Europe.

At the time she was approached for the job, she was a Managing Director at LaSalle, based in London. Mirvac’s then chairman, James MacKenzie, offered her the top role—but it wasn’t an instant yes. It took six months before she decided to move her family back to Australia and take it on. By then, the context had only gotten louder: “Having all of this corporate noise, both internally, externally—the market—was really quite challenging,” she later said.

The company she inherited was wounded. Lloyd-Hurwitz was blunt about what she found: Mirvac “really was in not a great place” when she arrived in 2012. And the clearest signal wasn’t on the balance sheet—it was inside the building. Employee engagement sat at 37%.

That’s not a dip. That’s organisational distress.

Over the years that followed, that number would climb dramatically—reaching 88% by 2017, a level most companies only talk about in leadership offsites. But it didn’t happen by accident. It was the result of two transformations running in parallel: a strategic reset and a culture reset, each reinforcing the other.

Part A: Strategy Reimagined

Early in 2013, Mirvac did something that sounds simple but is surprisingly rare for large organisations: it forced itself to start from first principles.

As part of a strategy rethink, Gould and his team built what they called “value driver trees” to test the real economics of everything Mirvac did. They combed through a decade of project data—what performed, what disappointed, and, crucially, why.

“We trawled through 10 years of data relating to historical projects to paint a picture of projects that performed well, to understand what made them successful,” Gould explained. “Similarly, we also looked at the projects that didn’t perform to expectations… We pulled everything apart and then put it back together again, which allowed us to be very clear on what we would do in the future and, importantly, what we wouldn’t do.”

That clarity had consequences. Mirvac reshaped its retail portfolio, selling non-core retail properties that didn’t fit the new direction. The company tightened its focus on urban areas with high population density and growth, and above-average household wealth.

The bet was deliberate: urban, not suburban. Prime, not secondary. Major capitals, not regional. It meant letting go of assets that were perfectly fine in isolation—but wrong for the strategy.

Lloyd-Hurwitz pushed ahead, and Mirvac began to present as a more coherent company: focused on urban development in Sydney and Melbourne, with an explicit asset-creation strategy. Management also signalled a capital allocation philosophy they wanted investors to hear clearly: return on invested capital would take priority over earnings per share when those two goals collided.

That’s a different kind of discipline. It’s the company saying: we’re not here to win the next quarter—we’re here to make the next decade work.

Part B: Culture Revolution

Strategy can set direction. Culture determines whether anyone follows it.

Mirvac’s cultural shift under Lloyd-Hurwitz wasn’t framed as perks or slogans. It was built around a simple, almost countercultural idea in corporate life: treat people like adults.

Giving employees more control over how, when, and where they delivered their work, she argued, drove engagement because it signalled trust. And the downstream effects looked like what engaged organisations always get: higher discretionary effort and stronger retention.

At Mirvac, 95% of people said they were willing to go above and beyond their roles to help make the company successful. And the company noticed it in hiring, too. In monthly new-starter orientations, Mirvac asked a basic question: why did you join?

Over time, the top answer changed. It used to be about the work: great projects. Increasingly, it became about the environment: “because you guys work differently and I want to be a part of it.”

That shift matters. When people join you for how you operate, not just what you build, culture stops being internal—it becomes a competitive advantage.

Part C: Results

The external recognition eventually caught up to what was happening internally.

Mirvac was ranked number one in Equileap’s Global Report on Gender Equality, leading a field of 4,000 companies assessed across 19 criteria. Lloyd-Hurwitz credited the result to sustained effort and an ongoing commitment to building a diverse team and inclusive culture, noting that gender equality had been a focus for years.

Workplace outcomes followed as well. In her last full year as CEO, 92% of employees said they were happy to recommend Mirvac as a great place to work, and 88% agreed their manager genuinely cared about their wellbeing. That same year, Mirvac was awarded Best Place to Work in the Property, Construction and Transport category by AFR BOSS.

And, in the background, the numbers that had once looked existential began to look like a comeback story. From a GFC low of roughly A$1 billion in market capitalisation, Mirvac rebuilt to around A$12.6 billion by the time Lloyd-Hurwitz departed.

The point isn’t that culture created market cap in a straight line. It’s that Lloyd-Hurwitz took a company that had been through a near-death experience—and then through a bruising leadership transition—and helped turn it into something rare in property: strategically focused, operationally disciplined, and known not just for what it built, but for how it worked.

VII. The Build-to-Rent Pioneer (2018–Present)

By the late 2010s, Mirvac had stabilised, refocused, and rebuilt trust—internally and in the market. Then in 2018, it made a bet that would shape the next decade: build-to-rent.

In Australia, the default residential development playbook had always been build-to-sell. You develop the apartments, sell them down to individual owners, take your margin, recycle the capital, repeat. Build-to-rent flips that logic. You develop the building, keep it, and operate it as a long-term rental business. It’s more capital intensive—because you’re holding the asset instead of cashing out—but the payoff is a recurring income stream and an ongoing relationship with the customer.

For Mirvac, that “ongoing relationship” was the point. If you’re going to own and operate the homes, you can finally design them for the people who actually live there—not for a spreadsheet of investor inclusions.

The first big proof of concept was LIV Indigo. It opened in 2020 at Sydney Olympic Park, about 16 kilometres from the Sydney CBD, surrounded by parklands and next door to one of the city’s biggest sporting and entertainment precincts. Mirvac positioned it as the country’s first large-scale build-to-rent community—purpose-built for renters, not retrofitted from a build-to-sell product.

Mirvac described the category in plain terms: a way to bridge the gap between buying and renting, giving Australians who can’t—or simply don’t want to—own a home a more compelling option than the typical rental experience.

And Mirvac leaned into the idea that “rental experience” is a product you can actually design.

As the company put it, BTR would mean developing and managing residential communities in sought-after city locations. With Mirvac acting as both developer and manager, it believed it could deliver a different kind of offering—one designed to remove the usual downsides that come with renting.

After 18 months of operating LIV Indigo, Mirvac said the learning had been invaluable—and the early metrics were strong. LIV Indigo reached 98% leased, and 82% of residents said they would recommend LIV to family and friends. For a business model that depends on retention and reputation, those are exactly the leading indicators you want.

With Indigo up and running, Mirvac started scaling the platform. In Melbourne, the company marked the commencement of construction at LIV Aston with a very public ceremony: the City of Melbourne Lord Mayor, Sally Capp, joined Mirvac CEO Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz, Mirvac’s Head of Integrated Investment Portfolio Campbell Hanan, and General Manager Build to Rent Angela Buckley.

Lloyd-Hurwitz used the moment to put a clear stake in the ground: Mirvac’s goal was to broaden housing options and increase supply in high-demand urban locations, with a target of having 5,000 LIV apartments operational by 2030. She also pointed to what Mirvac believed was its edge—its integrated platform, operating track record, and “genuinely customer-centric approach.”

As additional buildings came online, Mirvac argued the momentum was real. Following the completion of LIV Anura in Brisbane and LIV Albert in Melbourne, it said LIV Mirvac had become the largest operational build-to-rent portfolio and platform in Australia, with around 2,200 apartments developed by Mirvac—and a clear strategy to grow that to at least 5,000 apartments in the medium term.

Sustainability was designed in from the start, too. Mirvac’s stated ambition in BTR wasn’t just high-quality rental housing, but housing that was environmentally responsible. The LIV platform targeted a 5 Star Green Star Buildings rating, with decisions spanning materials through to renewable energy supply, aiming to minimise environmental impact while maximising liveability for residents. Mirvac also pointed to something no one else in the country could claim at the time: LIV Mirvac was the first build-to-rent operator with properties across New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland.

This is where Mirvac’s integrated model shows up as more than a historical talking point. Because it develops, constructs, and manages its own assets, it can build specifically for long-term operations. It can make design decisions that reduce maintenance headaches later. It can embed operational technology from day one. And it can shape the resident experience—and community programming—in ways that reduce turnover and build loyalty.

If you’re only building to sell, those feedback loops don’t really matter. In build-to-rent, they’re the whole business.

VIII. The Campbell Hanan Era & Current Strategy (2023–Present)

On 1 March 2023, Mirvac handed the keys to Campbell Hanan, appointing him Group Chief Executive Officer and Managing Director, and naming him a Director of the Mirvac Board the same day.

It was a very Mirvac-style succession: internal, orderly, and clearly planned. Hanan had joined the company in March 2016 as Head of Commercial Property, then stepped into a broader mandate in October 2020 as Head of the Integrated Investment Portfolio—exactly the part of Mirvac that ties creation and ownership together.

Before Mirvac, Hanan was CEO of Investa Office from 2013. He brought roughly three decades across property and funds management, including 12 years at Investa in senior roles, plus time at UBS Warburg.

The transition from Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz to Hanan was notably smooth—an internal promotion rather than an external search, with the outgoing CEO openly backing her successor. Lloyd-Hurwitz pointed out that both she and John handing over to internal successors was a sign of the depth Mirvac had built, and the result of careful succession planning. She framed the handover as continuity, not reinvention: a 50-year commitment to quality, alongside a high-performing culture and a strong focus on sustainability and innovation. She said she was confident that Rob, Campbell, and the Executive Leadership Team would build on those commitments and drive Mirvac’s success into the future.

Hanan inherited a company with a clearer strategy than it had pre-GFC, but with a tougher macro environment: rising interest rates pressuring property valuations, construction cost inflation squeezing development margins, and ongoing questions about office demand in a post-pandemic world.

Where Mirvac has leaned hardest into optimism is housing—what it calls the living sector. As Mirvac has put it, the tailwinds here are powerful: chronic housing undersupply, one of the fastest-growing populations in the Western world, record-low rental vacancy rates, and a rental stock base that is aging and often obsolete. In that framing, the opportunity isn’t cyclical—it’s structural. Shelter is a fundamental need, not a luxury, and Mirvac believes it’s positioned to lean into that over time.

That same “living” thesis now spans more than one format. Mirvac’s expansion into land lease communities reinforced what it claims is a unique position in Australia: delivering across the spectrum of housing typologies, from rental housing and build to rent through to land lease, house and land, medium density, and high density living.

At the same time, Mirvac has pushed harder on a capital partnerships model that lets it grow without stretching its own balance sheet. A key example is its work with Australian Retirement Trust (ART). In the Mirvac Industrial Venture (MIV), ART will invest 49 per cent, with Mirvac retaining 51 per cent. The seed asset for MIV is Switchyard in Auburn, NSW, expected to complete in 1Q24. Announcing the venture, Hanan called it “an exciting milestone” as Mirvac expands capital partnering across sectors, builds industrial and logistics exposure, redeploys capital into other development opportunities, delivers its pipeline, and adds revenue streams.

That’s built on an existing relationship. ART has a 49 per cent interest in Switchyard, Aspect Industrial Estate, and Stage 1 of SEED in Western Sydney, as well as a 33 per cent interest in South Eveleigh, Sydney, and an investment in the Mirvac Wholesale Office Fund.

The strategic punchline is simple: these partnerships allow Mirvac to develop and own more than its balance sheet alone would support, while earning management fees and validating that institutional capital is willing to back Mirvac’s platform. In a traditionally asset-heavy business, it’s a more asset-light way to scale.

All of this is happening as build-to-rent moves from “new idea” to “crowded category” in Australia. The sector has been expanding rapidly, with an estimated 39,000 apartments in the pipeline valued at around $30 billion—an increase of roughly $9 billion over the past 12 months.

And even in the office market—where the narrative has been the noisiest—Mirvac has a concrete data point that helps explain its strategy of staying at the premium end. EY, anchor tenant at EY Centre 200 George Street in Sydney since 2016, re-committed to its roughly 25,850 square metre space through to December 2036. Co-owned by Mirvac and M&G Real Estate, the precinct was completed by Mirvac in 2016. A long, renewed commitment like that doesn’t happen by accident. It’s the argument Mirvac has been making for years: in a world of uncertainty, the best assets still get chosen—and they still get held onto.

IX. Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

1. Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-LOW

Property development looks simple from a distance—buy land, build, sell—but it’s guarded by a thick wall of barriers: huge capital needs, planning expertise, regulatory relationships, and construction capability.

The biggest barrier, though, may be the least tangible: trust. After a string of high-profile building quality failures across Australia, buyers and tenants have become far more skeptical about who they’re backing. Mirvac’s half-century reputation for quality becomes a real form of defense—because a new entrant can’t compress decades of track record into a slick brochure.

That said, the capital barrier isn’t what it used to be. Foreign money continues to look for a home in Australian property, and sovereign wealth funds and pension funds can jump the queue by partnering with local developers. New competition can arrive funded—fast.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Mirvac’s two biggest inputs are materials and labour—exactly where the industry has felt the most strain. Post-pandemic labour shortages, supply chain disruptions, and ongoing infrastructure spending have intensified competition for skilled trades, and construction cost inflation has squeezed margins across the sector.

Mirvac’s scale helps, but it doesn’t make it immune. Its integrated construction capability—Mirvac Construction—reduces dependence on third-party builders, but it doesn’t eliminate supplier power. Even with your own construction arm, you still need subcontractors, specialist trades, and materials, and those markets set their own prices.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

In residential, buyers have no shortage of alternatives—Stockland, Lendlease, private developers, and the enormous pool of existing homes. And with affordability constraints biting, especially for first-home buyers, price sensitivity is high.

In commercial property, tenants have gained leverage in a post-pandemic world. They’re demanding more than four walls and a lobby: top-tier sustainability credentials, premium amenities, flexible terms, and tech-enabled buildings that genuinely improve the workday.

Mirvac’s strategy has been to stay at the premium end, where standout assets can still command loyalty. One example: EY, anchor tenant at EY Centre 200 George Street in Sydney since 2016, re-committed to its roughly 25,850 square metres through to December 2036. The EY Centre set new benchmarks for sustainability, innovation, and heritage integration, and Mirvac has described it as one of its most outstanding achievements. But that’s the point: premium product can reduce buyer power. Commodity space can’t.

In build-to-rent, tenants do have options—but strong occupancy and resident satisfaction at LIV suggest professionally managed renting can differentiate in ways the traditional rental market rarely does.

4. Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE

Office has the clearest substitution risk. Remote work has permanently changed the baseline demand for many organisations, and “do we even need this much space?” is now a normal boardroom question. Mirvac’s response has been consistent: focus on premium, sustainable buildings that offer something remote work can’t—experience, amenity, and a reason to gather.

Residential development competes against Australia’s vast existing housing stock. And build-to-rent competes directly with traditional rentals and home ownership. The difference is that BTR isn’t just housing supply—it’s a service-led product, and that experience can shift substitution dynamics for renters who want stability without buying.

Retail faces the ongoing substitute of e-commerce, which helps explain Mirvac’s reduced retail exposure and its focus on the kinds of retail that can’t be shipped in a box—more experiential, more place-based.

5. Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a fiercely competitive market. Australia’s listed property players—Stockland, Lendlease, Dexus, GPT Group, Charter Hall—are all battling for the same scarce things: prime sites, premium tenants, and institutional capital.

In Sydney and Melbourne especially, competition for top-tier development sites is intense, and land costs can be the make-or-break variable in project economics. In that environment, differentiation stops being marketing. It becomes survival. Mirvac’s long-running emphasis on quality, sustainability, and integrated capabilities is not a nice-to-have—it’s a rational response to high rivalry.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE

Mirvac owns and manages assets across office, retail, industrial, and the living sectors in its investment portfolio, with around $22 billion of assets under management. Alongside that, it has development activities across commercial and mixed-use and residential, with a pipeline of roughly $29 billion.

That scale brings advantages: more efficient deployment of development capability, better access to financing, and credibility with capital partners that often have minimum cheque sizes. The integrated platform also allows Mirvac to reuse expertise across projects—planning, design, delivery, leasing, operations.

But scale has limits in property. Development is site-specific: every parcel of land has its own constraints, approvals, and market dynamics. So scale helps—just not in the way it does in pure software or manufacturing.

2. Network Economies: LOW

Property isn’t naturally a network-effects business. More tenants in one building don’t automatically make the next tenant more valuable.

There is one place Mirvac could build a modest network effect: LIV. If the brand becomes shorthand for “high-quality renting,” then reputation, referral, and familiarity can compound across buildings. It’s not Facebook, but it’s not nothing.

3. Counter-Positioning: STRONG (Historically)

Mirvac helped pioneer build-to-rent at scale in Australia, launching LIV Indigo at Sydney Olympic Park in September 2020.

For competitors, copying BTR wasn’t just a new strategy—it threatened the old one. Traditional build-to-sell lets you sell apartments, recycle capital quickly, and book development profits sooner. Build-to-rent requires you to hold, operate, and accept a different return profile. Mirvac’s willingness to take that trade-off created a counter-positioned move that many peers couldn’t imitate quickly without disrupting their existing model.

The edge is narrowing as more players enter, but first-mover advantages still matter here: operational learning, an early brand foothold, and established capital relationships suited to the model.

4. Switching Costs: LOW-MODERATE

Most switching costs in property are limited. Office tenants can move when leases end, and residential buyers typically transact once.

But there are exceptions. Premium office tenants face real friction: fit-out investment, relocation costs, and the disruption of moving a workforce. And in build-to-rent, switching costs can become emotional and experiential—if the service is excellent and the community works, residents may choose not to leave. That’s not contractual lock-in, but it is a form of retention power.

5. Branding: MODERATE-STRONG

Mirvac’s brand has been built over fifty years, and in residential that matters because the decision is deeply personal and financially massive. A trusted developer name signals quality and reduces perceived risk. LIV is now adding a second layer of branding—specifically around renting—where consistency of experience is the product.

These kinds of brand assets can’t be bought off the shelf. They’re earned over time.

6. Cornered Resource: LOW

Mirvac doesn’t control a unique input like a rare mineral deposit, nor does it own irreplaceable land positions that nobody else can access. Most of what it has—development expertise, construction capability, capital partnerships—can theoretically be matched.

What’s harder to replicate is the combination: a true integrated platform operating at scale, with a long history of premium delivery.

7. Process Power: MODERATE

This is where Mirvac’s integrated model shows up as a real advantage. Designing, developing, constructing, leasing, and managing under one roof isn’t just a structure—it’s a learning system. Over decades, Mirvac has refined how those handoffs work, where mistakes usually happen, and how to standardise quality without standardising the product.

Competitors can build similar process capability, but the learning curve is long. In property, the feedback loop is measured in years—not weeks.

X. Bull and Bear Cases

The Bull Case

Housing Undersupply Creates Structural Demand

Australia’s housing shortage is no longer a short-term story. It’s structural. Governments have targets, but the gap persists, and population growth—driven heavily by immigration—keeps pushing demand higher across both ownership and rental markets.

That’s where Mirvac’s positioning matters. It isn’t making a single bet on a single housing product. It’s spread across the spectrum: build-to-rent, land lease communities, and more traditional residential development. If the country needs more housing in multiple forms, Mirvac has multiple lanes to run in.

The long-range upside case for build-to-rent is especially big. From a base of roughly $30 billion today, some forecasts argue the sector could expand dramatically over the next decade or so—into the hundreds of billions in value—delivering hundreds of thousands of new homes. As the argument goes: it’s not just housing supply, it’s a major new source of construction and operations jobs, and the emergence of a true institutional residential asset class in Australia.

If Australia’s market shifts closer to international norms, Mirvac’s early move into BTR could look less like a side bet and more like a category-defining head start.

Premium Office Resilient Despite Remote Work

The headline narrative says “offices are dead.” The more precise story is: mediocre offices are struggling, and premium offices are still competing.

Mirvac’s investment portfolio, by book value, is still heavily weighted to office—about half—followed by retail, then industrial, with the remainder in build-to-rent and land lease assets. Over the longer term, Mirvac has said it wants to tilt further toward industrial and living, and away from owning as many offices and retail centres.

But in the meantime, if flight to quality continues, Mirvac’s best buildings can keep winning. Tenants are consolidating. They’re choosing fewer locations, but better ones—and they’re willing to sign long leases when the building delivers the sustainability credentials, amenities, and experience they need.

If that dynamic holds, the market’s broad fear about offices may turn out to be too blunt.

Capital Partnerships Model Amplifies Returns

Mirvac’s capital partnerships strategy—through Australian Retirement Trust and others—could be a quiet engine of outperformance.

The logic is straightforward: partnerships let Mirvac do more development and hold more assets than its balance sheet could support alone. In return, it can earn recurring management fees, scale faster, and keep proving itself to sophisticated institutional capital. In a business that is usually defined by how much capital you can tie up, this is a path to becoming more capital-efficient—and potentially lifting returns on equity over time.

Culture as Competitive Moat

Property looks asset-heavy, but it’s still a people business. The best projects are won, designed, delivered, leased, and managed by teams—and those teams have choices.

Mirvac’s transformation in employee engagement and its employer reputation can translate into real advantages: recruiting, retention, and execution quality. And the same sustainability and inclusion credentials that attract talent can also attract premium tenants and institutional partners who increasingly want alignment with ESG expectations.

The Bear Case

Office Exposure Remains a Headwind

Even if premium assets outperform, half the investment portfolio is still office by book value. That’s a lot of exposure to a category facing genuine structural questions.

A weaker economy can hit employment and tenant demand. Remote work can keep pulling the baseline down. And office valuations that held up through the pandemic could still be vulnerable if weak conditions persist long enough. Mirvac may own strong buildings, but it can’t fully opt out of the category’s broader repricing risk.

Development Margins Under Pressure

Development is where property companies earn upside—and where they absorb pain first.

Construction cost inflation, labour shortages, and higher interest rates can squeeze margins quickly. If apartment prices can’t rise enough to offset costs, returns compress. And because development earnings can be meaningful in the mix—around a quarter of fiscal 2025 earnings, per the text here—a margin squeeze isn’t just a project issue. It becomes a group earnings issue.

Build-to-Rent Competition Intensifying

Mirvac may have helped bring build-to-rent to scale in Australia, but it won’t have the field to itself.

The pipeline has grown quickly. In the year to 30 June 2025, the sector expanded from about 29,100 apartments and $21.4 billion in value to roughly 39,000 apartments and around $30 billion—meaningfully more supply, very fast. That’s what happens when a model starts to look real: capital floods in.

More competitors means Mirvac’s first-mover edge can erode. Global operators arrive with capital and operating expertise. If the market fragments, Mirvac’s early investments may not earn the returns that originally made the risk worth taking.

Interest Rate Sensitivity

Real estate and interest rates have an unforgiving relationship: higher rates pressure valuations.

If rates stay elevated longer than expected, asset values can face ongoing headwinds. And even if Mirvac’s gearing is manageable, higher interest costs still create earnings sensitivity—especially in a period when both development and valuations can be under pressure at the same time.

Regulatory and Tax Risk

Build-to-rent is still young enough in Australia that policy can meaningfully change the economics.

Tax treatment remains subject to shifting rules, and state-based taxes vary, adding complexity and uncertainty. Changes to managed investment trust settings or foreign investment rules could also alter feasibility—right when the sector is trying to scale.

XI. Key Performance Indicators for Ongoing Monitoring

If you want to track whether Mirvac’s strategy is actually working—not just sounding good in presentations—there are three metrics that tend to tell the truth early.

1. Net Tangible Assets (NTA) Per Security

NTA per security is the market value of Mirvac’s property portfolio, net of debt, expressed per security. Because property valuations involve assumptions and judgment calls, the signal isn’t any single number—it’s the direction over time. Is NTA rising, flat, or sliding? And just as importantly: how does Mirvac’s NTA performance compare with the broader listed property market through the same cycle?

2. Residential Pre-Sales Balance

Residential pre-sales are future revenue Mirvac has effectively “banked” through exchanged contracts. When pre-sales are building, it usually means demand is healthy and upcoming settlements are more predictable. When they’re shrinking, it can point to softer buyer demand, delays in launching new projects, or a gap in the development pipeline. As a forward-looking indicator, pre-sales often matter more than last period’s settlements.

3. Office Occupancy and Lease Expiry Profile

Office is still a meaningful part of Mirvac’s investment portfolio, so occupancy and lease expiries are critical. High occupancy is the obvious one. The subtler one is lease expiry concentration: how many leases roll over at once, and how soon.

A longer weighted average lease expiry (WALE) generally signals tenant commitment and income visibility. A cluster of expiries can create a “re-lease risk moment” where vacancies rise, incentives increase, and earnings get pressured. In a flight-to-quality world, Mirvac’s premium buildings should hold occupancy and secure longer lease terms more consistently than secondary stock—and this is where you’ll see that advantage (or lack of it) show up.

XII. Conclusion: Fifty Years of Urban Reimagining

Those twelve apartments at Montrose in Rose Bay set something in motion that neither Bob Hamilton nor Henry Pollack could have fully mapped out. More than five decades later, Mirvac has helped shape how Australians live, work, and spend time in their cities—building the Olympic Village at Newington, turning Walsh Bay from decaying wharves into a waterfront neighbourhood, delivering premium commercial buildings like 8 Chifley, and pioneering a new, service-led way to rent through LIV.

Look at the arc and you can see the repeating motifs that show up in so many enduring companies. Founders with complementary strengths. An obsession with quality that hardens into a brand premium. The willingness to make big calls when the world feels unstable. And leadership transitions that, at their best, preserve what matters while giving the business room to evolve. The GFC was close to existential for Mirvac. The recovery wasn’t just a rebound—it was a hard-earned lesson in focus, discipline, and resilience.

What distinguishes Mirvac today is less any single asset than the system it’s built: design, development, construction, leasing, and long-term management under one roof. That integrated model gives Mirvac more control over outcomes, faster feedback loops, and a clearer ability to build for the long term. Pair that with a culture that can attract and retain talent in a brutally competitive industry, and you get advantages that compound—so long as they’re protected and renewed.

For long-term investors, Mirvac is a lever on Australia’s urban future, with sustainability credentials that increasingly influence tenants, partners, and capital. Build-to-rent, in particular, offers a chance to shift more of the business from cyclical development profits toward steadier, recurring income. But the risks don’t disappear: development margins remain tight, competition—especially in BTR—is accelerating, and the office market’s structural questions still hang over the sector.

Mirvac started in Rose Bay with a simple, demanding premise: build better. It grew into one of Australia’s largest property groups by turning that premise into a platform. The next chapter—whether it’s defined by leadership in build-to-rent, a successful rotation toward living and industrial, or a new set of shocks that force another reinvention—will decide whether Mirvac’s trajectory keeps bending upward.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music