Lynas Rare Earths: The West's Rare Earth Champion

I. Introduction: A Monopoly-Breaker in the Outback

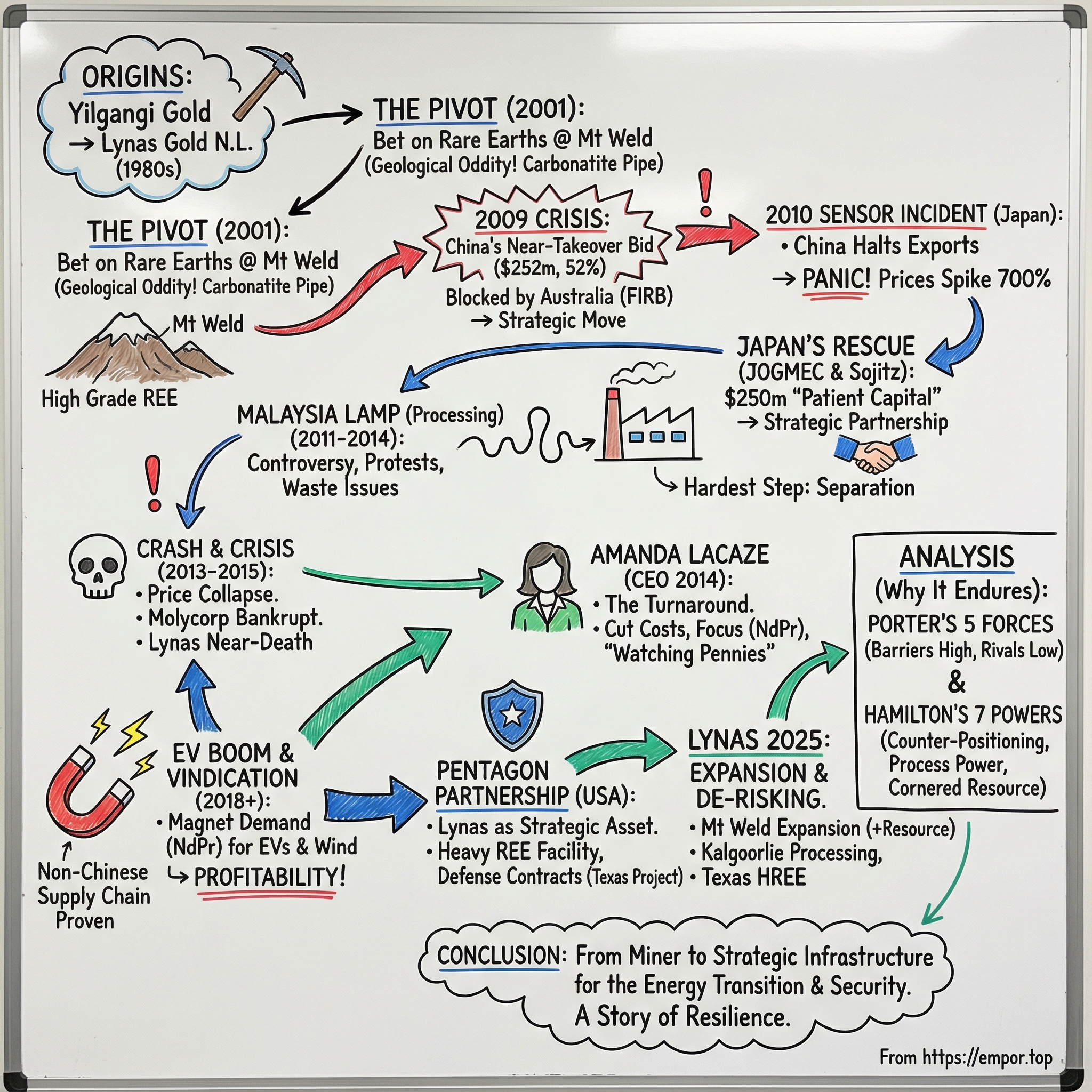

Picture a patch of rust-red earth in Western Australia’s Goldfields, where spinifex clings to the heat and the horizon feels endless. Under that scrub sits Mt Weld: a two-billion-year-old volcanic plug that, by a quirk of geology, concentrates rare earths at a level that makes mining people lean in and lower their voices. And sitting on top of it is Lynas Rare Earths—an unlikely company that’s become central to Western supply chain security in an era when economics and national security are starting to rhyme.

In a market dominated by China, Lynas is the outlier that matters. It’s the largest rare earth miner outside China, and one of the only scaled producers of separated rare earth materials beyond Beijing’s reach. That distinction isn’t a branding line—it’s the whole point. China controls roughly 70% of global production and more than 85% of refining capacity, which is where the real leverage lives. Lynas is one of the few companies that runs the whole chain end-to-end: it mines at Mt Weld, sends material through processing in Western Australia, and feeds downstream facilities in Kalgoorlie and Gebeng, Malaysia.

None of this was inevitable. Lynas came frighteningly close to disappearing—twice. Once during the global financial crisis, when a Chinese state-owned group nearly took a controlling stake. And again in the mid-2010s, when rare earth prices collapsed and debt started to look like an anchor. The fact that Lynas survived at all—while America’s would-be counterpart, Molycorp, went bankrupt—turned out to be one of the most consequential “near misses” in critical minerals.

The stakes are high because rare earths are the quiet enablers of modern hardware. They show up in permanent magnets for electric vehicle motors and wind turbines, in guidance systems for precision weapons, in smartphone components, and in industrial catalysts. And while rare earths have many uses, the growth engine is magnets—especially the neodymium-praseodymium family that enables compact, high-performance motors.

That’s why this story matters now. The world is in the early innings of two transitions happening at once: electrification and renewable energy on one hand, and supply chains being reorganized away from China on the other. Electric vehicles and wind turbines don’t just need more metals—they need specific ones, in specific forms, processed to high purity. In that context, Lynas isn’t simply a miner. It’s infrastructure.

This is the story of how a small Australian gold miner became a strategic asset for three allied nations—Japan, Australia, and the United States—and what that journey reveals about the messy intersection of mining, geopolitics, and the energy transition.

II. Origins: From Gold Miner to Rare Earth Bet (1983–2001)

Lynas didn’t start life as a “critical minerals champion.” It started the way a lot of Australian mining stories start: as a small, ambitious bet on gold.

The company was incorporated in 1983 and is headquartered in East Perth. Back then, though, it wasn’t Lynas Rare Earths. It was Yilgangi Gold NL—one more junior miner chasing the kind of discovery that turns a speck on the map into a name on the stock exchange. In 1985, it rebranded as Lynas Gold N.L., and in 1986 it listed on the ASX, stepping onto the public markets treadmill where capital is oxygen and results are everything.

The founding force was the Sumich family of Perth, and in 1986 they brought in Les Emery as the first CEO and Managing Director. Emery would run the company until 2001, guiding it through the hard, unglamorous work of being a small-cap explorer: raising money, drilling holes, proving up assets, and trying to graduate from “maybe” to “real.”

That graduation came in 1994. After an exploration discovery, Lynas opened its first gold mine at Lynas Find, about 130 kilometers south of Port Hedland in Western Australia. For a junior miner, that’s the moment you’re supposed to build from—when you finally have production, revenue, and a story investors can understand.

But gold in Australia is a brutal arena. The country has deep expertise, big incumbents, and a constant pipeline of new juniors. Lynas could keep fighting for attention and deposits in a crowded game… or it could try to play a different one entirely.

In 2001, it chose the second path. Lynas sold off its gold division and pivoted to rare earths—at a time when rare earth prices were low, China already dominated the market, and most of the West barely knew what these elements were, let alone why they mattered. The thesis centered on Mt Weld, a deposit that others had examined over the years but no one had turned into a commercial success.

It was a clean break: walking away from a working, if modest, gold business to chase a resource most investors weren’t paying attention to. The kind of decision that looks reckless in the moment—and inevitable only in hindsight.

III. The Crown Jewel: Mt Weld and Why It Matters

To understand why Lynas matters—and why governments keep treating it less like a company and more like infrastructure—you have to start with Mt Weld. This isn’t just “a rare earth deposit.” It’s one of those geological oddities where everything lined up: the right kind of rock, the right kind of chemistry, and enough time for nature to do what engineers wish it could do.

Mt Weld sits on a two-billion-year-old volcanic plug in Western Australia. Long ago, a volcano punched up through the Yilgarn Craton and formed a carbonatite, a type of intrusion that’s unusually rich in rare earth-bearing minerals. Then came the part that turned “interesting” into “exceptional”: weathering. Over immense spans of time, water moved through the rock, stripping away more common material and leaving the rare earths behind in a concentrated layer near the top. Geologists call it a carbonatite-derived laterite, and in Mt Weld’s case roughly 1.8 kilometers of the plug was weathered into a high-grade supergene rare earth oxide deposit.

The practical outcome is simple: unusually high grades, and a deposit built for longevity. The most important zone is the Central Lanthanide Deposit (CLD), discovered in 1988, sitting right in the middle of the pipe. By 2005, it was considered one of the largest rare earth deposits in the world.

Grade sounds like a mining technicality until you remember what rare earths actually demand. Mining them is one thing; separating them is the hard part. The chemistry is complex, the processing is intensive, and the waste streams can include naturally occurring radioactive materials. In that world, higher grade is oxygen. It means less rock to move, crush, and treat for every tonne of usable product—and that can be the difference between a project that works and a project that never escapes the PowerPoint stage.

Mt Weld’s mix matters too. It contains both light and heavy rare earth elements. The light rare earths—lanthanum, cerium, praseodymium, and neodymium—are the workhorses, especially for catalysts and permanent magnets. And the heavy rare earths, like dysprosium and terbium, attract outsized attention because they’re critical for performance in high-temperature environments, including electric vehicle motors and wind turbines.

Plenty of companies looked at Mt Weld over the years. But it wasn’t until Lynas took full control in 2002 that the deposit stopped being “promising” and started becoming real. Development accelerated, and mining began in earnest in 2007. The plan wasn’t just to dig ore—it was to build a non-Chinese rare earth supply chain end-to-end, from mine to separated product, at a time when that idea was closer to heresy than strategy.

That decision is what turned Mt Weld from a world-class deposit into something rarer still: a strategic asset. Lynas went on to build a vertically integrated operation serving customers across Asia, Europe, and the United States—and it remains the world’s largest producer of separated rare earth materials outside of China.

IV. The First Existential Crisis: China's Near-Takeover (2009)

Lynas had the deposit. It had the plan. What it didn’t have, in 2009, was money.

The global financial crisis hit at exactly the wrong moment. Credit markets seized up, investors fled anything that looked long-dated or technically complex, and Lynas found itself in the classic junior-miner trap: a world-class asset stranded without funding.

Then a lifeline appeared—wrapped in a flag.

In May 2009, China Non-Ferrous Metal Mining (Group) Co., a Chinese state-owned enterprise, offered a deal that would have transformed Lynas overnight. The proposal was straightforward and sweeping: the Chinese group would buy a controlling stake—about 52%—for $252 million, provide guarantees for a further US$184 million debt package to be sourced from China, take four of eight board seats, and secure access to a share of Lynas’s output.

From Lynas’s perspective, it looked like survival. From Beijing’s perspective, it looked like insurance: keep the most credible non-Chinese rare earth project from ever becoming a true competitor.

What happened next turned a corporate financing story into a geopolitical one. Treasurer Wayne Swan initially carried paperwork from the Foreign Investment Review Board recommending approval with him to an IMF meeting in Washington. He had previously signed off on an FIRB recommendation to approve Chinese investors taking a 25% stake in another rare-earths prospect, Arafura—so the Lynas deal didn’t look, at first, like a hard stop.

But while in the U.S., Swan read a New York Times report laying out just how dominant China already was in the rare earth market. That was the jolt. He asked the FIRB to take another look. The revised view came back with conditions that effectively broke the logic of the bid: cap Chinese ownership at no more than 49.9%, and limit board control to less than half. China Non-Ferrous withdrew.

Australia had blocked a Chinese state-owned group from buying a majority stake in Lynas, explicitly to preserve local control of a strategic resource.

The timing is what made it so striking. This was 2009—before “decoupling” became a common word in policy circles, before supply chain security became a staple of Western politics, before rare earths were front-page news. Conventional wisdom still leaned toward letting markets sort out ownership, and Chinese investment in Australian mining was widely viewed as beneficial.

In other words: Australia made the call early.

But that decision also left Lynas with the same immediate problem it had before the bid: it still needed funding, fast. Mt Weld couldn’t be developed on strategic significance alone.

So Lynas went back to the market and found an alternative. In 2009, the company raised A$450 million in equity from J.P. Morgan to fund the development of the Mt Weld mine—and the processing plant it planned to build in Kuantan, Malaysia. Western capital replaced Chinese capital at the moment it mattered most, and the integrated “mine-to-separated-product” vision stayed alive.

The counterfactual still looms over the entire industry. If that Chinese deal had gone through, Lynas would likely have become another component inside China’s rare earth system—its board influenced, its output directed, its strategic value to non-Chinese buyers largely neutralized. The world’s only scaled producer of separated rare earths outside China might never have existed at all.

V. The 2010 Rare Earth Crisis: The World Wakes Up

If Australia blocking the 2009 deal was the first tremor, September 2010 was the earthquake that made everyone look up and realize what rare earth dependence actually meant.

On September 7, 2010, near the disputed Senkaku Islands in the waters southwest of Japan, a Chinese fishing trawler collided with two Japanese coast guard vessels. Japan detained the captain. What could have stayed a tense maritime incident didn’t. It escalated—fast—into a diplomatic standoff, and then into something far more unsettling: economic pressure.

Beijing’s retaliation came in layers. Negotiations to expand air routes were halted. Chinese tourist group travel to Japan was curtailed. But the move that hit like a hammer was on the industrial supply chain: rare earth exports to Japan effectively stopped for roughly two months.

Japan’s reaction wasn’t abstract. It was panic—especially in the auto sector, where rare earths were indispensable for the permanent magnets that power modern motors. At the time, Japan relied on China for nearly 90% of its rare earth imports. When the shipments stopped, the vulnerability wasn’t theoretical anymore. It was production lines staring down the possibility of shutting.

Prices reacted the way markets do when they discover a choke point. In the wake of the 2010 export disruption, prices for some rare earth oxides surged more than 700%. Overnight, a set of obscure elements became a board-level issue across global manufacturing.

To this day, there’s debate about exactly what happened on China’s side. A spokesperson from China’s Ministry of Commerce told China Daily that “China has not issued any measures intended to restrict rare earth exports to Japan.” At the same time, Chinese industry newspapers reported that, two months earlier in July 2010, the Ministry of Commerce had announced a 40% reduction in China’s global rare earth exports for the second half of the year.

Targeted embargo or accelerated policy—Japan experienced it the same way: as a sudden loss of supply controlled by a single country. And the West saw, in real time, how quickly that leverage could be applied.

The policy response was immediate. Japan assembled a comprehensive set of measures to strengthen its rare earth supply chain resilience. In October 2010, it prepared a supplemental budget of JPY100 billion—about $1.2 billion at the time—an unusually fast, unusually large move that signaled just how urgent this suddenly felt.

For Lynas, the moment was brutal for the world—and perfectly timed for its strategy. Here was the most credible non-Chinese rare earth project, with a world-class deposit under development, just as customers and governments began treating “non-Chinese supply” as a strategic requirement, not a nice-to-have.

And in the strange boom-and-bust economics of rare earths, the aftermath mattered too. When China later relaxed export rules, prices fell again. The whiplash left companies with expensive new capacity exposed—Molycorp, for example, was left carrying the cost of its $1.25 billion processing facility into a collapsing price environment. That same spike-and-snapback, however, created the opening for Lynas to secure the partnership that would keep it alive: Japan stepping in, not because it was the cheapest option, but because it was the strategic one.

VI. Japan to the Rescue: The Strategic Partnership

Japan’s response to the 2010 shock didn’t stop at speeches and emergency stockpiles. It went looking for a structural fix—and that choice would end up being decisive for Lynas’s survival.

At the center of Japan’s playbook was JOGMEC: the Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation, a state-backed organization overseen by the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry. JOGMEC had been created in 2004 through the merger of older oil and metals entities, but the rare earth embargo was the moment it truly focused on rare earths. The mission was clear: reduce Japan’s exposure by diversifying supply, even if that meant stepping in where private capital was hesitant.

Lynas, with Mt Weld in Western Australia, was the obvious candidate. It had the resource. It had momentum. And it had a problem that every rare earth project eventually runs into: building separation capacity is expensive, slow, and hard to finance—especially when prices and politics can swing the market in a matter of months.

In 2011, JOGMEC and Japanese trading house Sojitz Corp put together a $250 million financing package for Lynas. In exchange, Sojitz secured rights to distribute Lynas’s rare earth output to Japanese customers. The deal wasn’t subtle. Japan wasn’t just buying product—it was helping build the supplier.

This was patient, strategic capital—deployed for supply security, not quick returns. At a time when industrial policy was unfashionable in much of the West, Japan effectively picked a winner. The rationale was blunt: without Lynas, there would be no meaningful non-Chinese rare earth supply chain to speak of. Japan had just watched what happens when a single supplier can turn the tap off. Paying to create an alternative was cheaper than living with that vulnerability.

The timeline proved the point. The investment helped Lynas reach trial production about two years later, but profitability didn’t arrive until 2018. That long arc—years of technical ramp-up and financial strain before the model finally worked—is exactly why Lynas CEO Amanda Lacaze later emphasized the need for “patient capital” in rare earths.

And it worked, not just for Lynas, but for Japan’s resilience. Japan’s dependence on Chinese rare earths fell from roughly 90% at the time of the incident to around 60% today. Japan’s rare earth consumption is now about half what it was then. Those two shifts—more diversified supply and less material intensity—help explain why, despite further diplomatic friction since 2010, Japan hasn’t faced the same level of rare earth vulnerability again.

The policy lesson lands cleanly: if you want supply chain independence in critical minerals, you don’t get it by hoping the market wakes up in time. You get it by underwriting capacity—accepting long timelines, tolerating volatility, and backing partnerships that may look uneconomic on a spreadsheet but make perfect sense as national strategy. Japan spent hundreds of millions and waited nearly a decade. What it bought was the only scaled alternative to China.

VII. Building the Malaysian Plant: Controversy and Setbacks (2010–2013)

Japan’s capital and Australia’s approval kept Lynas alive. But turning Mt Weld into a real, end-to-end supply chain required the hardest step of all: processing. And the moment Lynas chose to do that processing in Malaysia—rather than in Australia—it stepped into a political fight that would follow the company for years.

The Lynas Advanced Materials Plant, or LAMP, was built in Gebeng, near Kuantan in the Malaysian state of Pahang. It was a massive bet: roughly an $800 million facility, and the largest rare earth extraction plant outside China. The model was straightforward on paper. Concentrate would be mined at Mt Weld in Western Australia, shipped to Malaysia, and processed there into separated rare earth products.

Then the story hit the public.

On 8 March 2011, the New York Times reported on the construction of the plant—describing it as the world’s largest rare earths processing facility—and local attention snapped into focus. For residents around Kuantan, rare earth processing didn’t sound like industrial chemistry. It sounded like radiation. Malaysia had lived through the Bukit Merah controversy years earlier, and the Fukushima Daiichi disaster in Japan had just reignited global anxiety about anything nuclear-adjacent. LAMP quickly became a symbol—fairly or not—of that fear.

The core issue was waste. Mt Weld’s ore contains thorium, and rare earth processing concentrates naturally occurring radioactive materials. Even if the levels are low, the material has to go somewhere. Opponents argued Lynas had no safe, long-term plan for disposal, and protests and campaigns formed around that single question: what happens to the waste, and who lives next to it?

The pressure organized fast. Himpunan Hijau—literally “Green Assembly” or “Green Rally”—emerged as a focal point for opposition to the plant, accusing it of endangering local livelihoods, the environment, and future generations through toxic and radioactive waste. In one of the most visible moments, nearly 10,000 people took to the streets in Kuala Lumpur to protest as LAMP prepared to begin operations and received its first shipments of concentrate.

Regulators were pulled into the spotlight. On 5 September 2012, Malaysia’s Atomic Energy Licensing Board granted Lynas a temporary two-year operating licence, even as concerns persisted about the lack of a long-term disposal plan. Legal challenges and public opposition created months of delays through 2011 and 2012, and the controversy spilled into Malaysian election politics, with opposition parties campaigning against the project.

Eventually, the plant did start producing. LAMP entered production in 2013. In the first quarter of 2014, it produced 1,089 tonnes of rare earth oxides, with a target of 11,000 tonnes per year. On 2 September 2014, Lynas was issued a two-year Full Operating Stage License by the Malaysian Atomic Energy Licensing Board.

But “operating” didn’t mean “resolved.” The controversy never fully went away. After a change in government, Malaysia conducted a review of Lynas’s operations and later told the company it would need to remove the radioactive waste accumulated over the previous six years if it wanted to continue operating.

LAMP exposed the central tension in rare earths: the processing is exactly what most countries say they want—until it’s proposed near real communities with real political power. Lynas ended up squeezed between tough expectations and public distrust, in a fight that would ultimately help push early-stage processing steps back onto Australian soil.

VIII. The Near-Death Experience: Crash and Crisis (2013–2015)

If the Malaysian controversy was a slow-burning fire, the rare earth price collapse was the tidal wave that hit while Lynas was still trying to get its feet under it. The boom that made Mt Weld and LAMP financeable in the first place didn’t last. When prices snapped back, Lynas didn’t just lose a tailwind—it lost the economic assumptions the whole build-out had been based on.

By the time Amanda Lacaze took the helm in June 2014, the company was in a fight for survival. Rare earth prices had fallen hard after the 2010–2011 spike, and Lynas was carrying heavy losses and debt that was starting to look unmanageable. At the same time, its brand-new refinery in Kuantan—the Lynas Advanced Materials Plant, opened in 2012 to process Mt Weld concentrate—was still fighting on two fronts: protests in the community and regulatory scrutiny over radioactive waste. The result was a company squeezed from every direction, drifting dangerously close to bankruptcy.

The broader market wasn’t offering any mercy. High prices in 2010 and 2011 had pulled supply in from outside China. Molycorp restarted its Mountain Pass mine in California after a decade of dormancy, and the industry started acting like a new non-Chinese rare earth era had arrived. But the supply response arrived just as demand softened—some manufacturers substituted where they could, and others simply moved production to China, closer to the materials. The panic premium evaporated, and prices collapsed.

For Lynas, the public markets delivered a brutally clear verdict. The stock fell from its April 2011 high of 26.63 AUD to 0.30 AUD by June 2015—an almost total wipeout in roughly four years. For anyone who bought the “rare earths are the next oil” story at the peak, it was catastrophic.

And Lynas wasn’t the only casualty. Molycorp—the U.S. producer often framed as America’s answer to Chinese dominance—filed for bankruptcy in June 2015, seeking Chapter 11 protection after prices plunged and profitability never materialized. Not long before, it had commanded a multibillion-dollar market value when China’s export restrictions made non-Chinese supply look like a guaranteed win. In the downturn, that confidence turned into a debt trap.

This is where the story gets interesting. Because Molycorp didn’t make it. Lynas did.

That contrast became one of the most dissected case studies in critical minerals: two flagship “outside China” projects, hit by the same price collapse, with two very different endings. Part of the explanation was geological—Mt Weld’s higher-grade ore supported better unit economics than Mountain Pass. Part of it was financial and strategic—Japan’s partnership brought patient capital and reliable offtake. And part of it came down to timing: right as Lynas was running out of runway, it was about to get a CEO willing to run the company like a turnaround, not a dream.

IX. Amanda Lacaze: The Turnaround CEO

Lynas’s survival story is inseparable from Amanda Lacaze—and the fact that, on paper, she looked like an odd fit was part of the point.

She joined the company as a Non-Executive Director on 1 January 2014. Then, as the crisis sharpened, she stepped into the job that mattered: Executive Director and Chief Executive Officer on 5 June 2014. Lynas was in no condition for a “steady hand.” It needed a turnaround operator.

Lacaze didn’t come up through pits and processing plants. She brought more than 25 years of senior operational experience from a very different world: Chief Executive Officer roles at Commander Communications and AOL7, Executive Chairman of Orion Telecommunications, earlier senior marketing leadership at Telstra, and business management roles at ICI Australia. She even started out in consumer goods at Nestle. None of that teaches you solvent extraction chemistry. But it does teach you how to run a business when the numbers don’t work, the clock is ticking, and customers are the only reason you exist.

That outside perspective shaped her approach. Instead of treating production volume as the scoreboard, she treated cash, costs, and customer revenue as the real operating metrics. She was also openly frugal—often describing herself as “watching the pennies,” a mindset that was reinforced by years on ING Bank’s board. In a company that had been built for a boom, that mentality mattered.

The playbook was straightforward and painful: cut complexity, strip out overhead, and focus. Lynas narrowed its product strategy toward the most valuable outputs, including neodymium and praseodymium (NdPr), the magnet metals that actually drive demand. At the same time, Lacaze pushed operational optimization and expense reduction across the business.

Even the corporate footprint got rebuilt. When she arrived, Lynas had corporate offices in Sydney, Kuala Lumpur, and Perth—on top of its operating sites at Mt Weld and Kuantan. The company decided staff should be co-located at production facilities, with only a small presence in Perth. The logic was as practical as it sounds: fewer disconnected teams, faster decisions, and lower costs. Closing offices delivered meaningful savings.

Alongside that came the financial work: renegotiating debt facilities, resizing the cost base, re-orienting the company toward customer revenue growth, and getting the whole organization aligned around performance.

It didn’t pay off overnight. Lynas didn’t return to profitability until 2018—about four years after Lacaze took over—which says as much about rare earth economics as it does about management. But the fact that it got there at all, while others fell away, is what cemented her reputation. Under her leadership, Lynas emerged as the only scaled producer of separated rare earth materials outside China.

Lacaze has now led Lynas since June 2014, a tenure of more than a decade—unusual continuity in an industry known for executive churn, and a key ingredient in executing a long, volatile strategy.

X. The EV Boom and Vindication (2018–2022)

By 2018, Lynas finally crossed the line from “surviving” to “working.” After years of volatility, delays, and bruising cost cuts, the world started moving in the direction Mt Weld had been built for. Electric vehicles went from forecast to reality. Wind builds accelerated. And the thing that ties both together—the permanent magnet supply chain—mattered more each year.

As demand recovered in the late 2010s, Lynas was in position. It had the mine, the processing capability, the hard-earned operational learning, and—crucially—the staying power to make it to the upswing. By 2021, that showed up in the numbers. Revenue climbed sharply year over year, and the company posted a meaningful profit after years of losses.

Just as important was what those results signaled. Lynas was no longer a fragile, boom-dependent story. It had moved decisively past its penny-stock era, strengthened its balance sheet, and emerged as the world’s second-largest rare earths producer overall—behind China’s state-backed giants—and the largest outside China.

The energy transition was the ultimate validation of the original thesis. Rare earths weren’t a quirky corner of the periodic table; they were core inputs for modern electrification. Magnets are where the value and the pull-through demand sit, and they’ve become the dominant application for rare earth consumption as EV and wind markets expanded.

Wind is a useful way to make the point tangible. In large direct-drive turbines, permanent magnets aren’t a rounding error—they’re a major material input. Multiply that across gigawatts of new capacity, and you get why policymakers and manufacturers started treating magnet materials like strategic infrastructure rather than just another commodity line item.

By the early 2020s, the vindication wasn’t merely financial. Lynas had demonstrated something the market had doubted for a decade: a non-Chinese rare earth supply chain could be built, scaled, and run as a real business. That “proof of possibility” mattered almost as much as the tonnes produced, because it arrived right as Western governments began shifting from awareness to action on supply chain resilience.

It also made one lesson impossible to ignore: nothing about rare earths moves on venture timelines. The capital is heavy, the learning curves are long, and the market can turn on policy decisions. That’s why Amanda Lacaze kept returning to the same phrase—patient capital. Lynas had needed it to get through the downcycle, and the West would need more of it if it wanted more than one champion.

XI. The Pentagon Partnership: Becoming a Strategic Asset

By the early 2020s, Lynas had gone from “the rare earth survivor” to something far more unusual: a company that Washington began treating as part of national security infrastructure.

That shift crystallized in its relationship with the U.S. Department of Defense. The DoD awarded a multi-year contract to Lynas USA, LLC to build an industrial-scale domestic separation and processing facility for Heavy Rare Earth Elements. The goal wasn’t just another plant. It was a commercially sustainable U.S.-based capability to separate rare earths for defense needs, essential commercial use, and clean energy products—an attempt to rebuild a link in the supply chain that had largely migrated offshore.

The Pentagon then doubled down. Lynas USA secured a follow-on DoD contract focused on the heavy rare earths component of the rare earth processing facility planned for the Gulf Coast of Texas. Under the updated arrangement, the U.S. government’s contribution increased to about $258 million, up from the roughly $120 million previously announced.

Amanda Lacaze framed the pitch in the language the moment demanded: Lynas was already a proven producer of separated rare earth materials, and this project would extend that operational know-how into a U.S. supply chain designed to be cost-efficient, environmentally responsible, and fit for the defense industrial base. In her words, it would improve U.S. access to heavy rare earth elements and provide critical industries with “sustainably produced and quality assured” products.

On a 149-acre site, Lynas ultimately secured more than $300 million in Pentagon contracts tied to the project. And if it reaches full operation, the Texas facility could represent around a quarter of global rare earth oxide supply—an astonishing number that explains why this stopped being merely a corporate expansion plan and started reading like a strategic deployment.

That strategic framing was explicit. The award was positioned as supporting the aims of the 2022 National Defense Strategy and Executive Order 14017, “Securing America’s Supply Chains.” It also fit the broader posture of the Biden-Harris Administration: investing with allied partners, including Australia, under the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework. Since 2020, the DoD has committed more than $439 million to strengthen domestic rare earth supply chains.

But building rare earth processing in the U.S. has proven to be as messy as everyone who’s lived through LAMP could predict. The Texas project has run into cost pressure, including wastewater management complexity. Lynas entered negotiations for federal support, even as shifting geopolitics threatened the economics from another direction: proposed Chinese export restrictions raised the stakes, but also highlighted a policy paradox where national security priorities can collide with trade and industrial policy realities.

The timeline captures the friction. From 2021 to 2023, the DoD allocated $288 million to support development. In 2024, negotiations around offtake agreements with the DoD began to bog down. Then, in February 2025, a Dow Chemical permit withdrawal created a new regulatory bottleneck.

In other words: government funding can lower capital risk, but it can’t make permitting, environmental constraints, and commercial agreements disappear. The Texas project is the clearest illustration yet of both the opportunity—and the execution difficulty—of building a non-Chinese rare earth supply chain at industrial scale.

XII. Lynas 2025: Expansion and De-Risking

By late 2025, Lynas was no longer just proving it could survive. It was trying to make itself harder to kill—by expanding capacity, widening what it could produce, and reducing how much of the system depended on any single country.

The most important foundation is still Mt Weld. On 5 August 2024, Lynas released a Mineral Resource and Ore Reserve update that materially strengthened the long-term story: Mineral Resources increased by 92% and Ore Reserves by 63%, including a meaningful increase in contained heavy rare earth mineralisation. In practical terms, the update supported a mine life of more than 35 years at current production rates, and more than 20 years at expanded rates—enough concentrate feedstock to underpin either the current NdPr oxide production level or a larger, expanded run-rate.

That resource update paired with a major physical build-out. Mt Weld was in the middle of an A$500 million expansion aimed at boosting ore output to meet rising demand. Lynas also updated its Mineral Resource estimate to 106.6 million tonnes at an average grade of 4.12% Total Rare Earth Oxide, containing 4.39 million tonnes of TREO—up sharply versus the August 2018 estimate.

If Mt Weld is the “why,” Kalgoorlie is the “how.” Lynas’s Rare Earths Processing Facility in Kalgoorlie is the first large-scale facility of its kind in Australia, designed to do value-added processing of Mt Weld concentrate. It also has the capability to take third-party feedstock from other projects as they come online—an important detail if Australia wants a broader rare earth industry rather than a single-company solution.

Lynas opened the Kalgoorlie facility as part of its Lynas 2025 growth plan. The roughly $800 million project was delivered in under two and a half years from receiving full construction approvals—a pace that’s rare in complex industrial builds. Strategically, it matters because it replaces processing steps that had previously been done at Lynas’s plant in Malaysia, a site that had spent years under political and environmental pressure.

The move wasn’t purely optional. Malaysian regulators had imposed conditions requiring Lynas to shift radioactive processing steps out of Malaysia. But it also fit a bigger de-risking logic: keep the system geographically diversified across Australia and Malaysia, with the longer-term possibility of meaningful capacity in the United States as well.

Product diversification was part of the same play. By the end of 2025, Lynas was targeting first-time production of heavy rare earths such as dysprosium and terbium, adding them to its established light rare earth output. New circuits were planned to enable separation of up to 1,500 tonnes of SEGH—a mixed heavy rare earth compound containing samarium, europium, gadolinium, holmium, dysprosium, and terbium.

All of this happened against a market backdrop that reminded everyone why rare earths are hard. Lynas’s results showed the push-and-pull between higher volumes and weaker pricing. For the full year 2025, revenue rose to AU$556.5 million, but net profit after tax fell to AU$8.0 million. In the half-year ended 31 December 2024, profit dropped sharply as lower rare earth prices outweighed increased production and sales volumes—even as NdPr production rose to 2,969 tonnes and revenue increased to AU$254.3 million. Over that same period, the China domestic NdPr price declined from $56/kg in December 2023 to $49/kg in December 2024.

Against that volatility, Amanda Lacaze and her team leaned hard into capital discipline. In August 2025, Lynas raised A$750 million in equity to support growth, while keeping net debt to EBITDA at zero.

XIII. Porter's 5 Forces and Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

To see why Lynas has endured when so many rare earth “challengers” have come and gone, it helps to zoom out. Rare earths aren’t a normal commodity business. The industry’s structure is shaped by brutal physics, slow-moving regulation, and a single dominant player that can change the rules overnight. That combination makes Lynas’s position easier to understand—and harder to replicate.

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Starting a new rare earth producer is less about finding a deposit and more about surviving the long gauntlet that follows. Processing facilities alone can cost more than $800 million. Permitting and regulatory approvals can drag on for years. And the real bottleneck is human: separation chemistry is scarce expertise, and it doesn’t scale from textbooks. It takes years of trial, error, and optimization—under the microscope of environmental oversight and public scrutiny. Add in decade-long timelines and uncertain pricing, and most capital simply won’t stick around long enough to see a project through.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

Lynas’s advantage starts with a simple fact: it isn’t dependent on someone else’s ore. It owns Mt Weld, a high-grade deposit with a long runway ahead, and it has built processing capability outside China. That vertically integrated setup strips out a classic vulnerability in mining and processing businesses: getting squeezed by upstream suppliers when markets tighten. With its own feedstock and its own plants, Lynas controls the inputs that matter most.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

Lynas sells to sophisticated customers—Japanese manufacturers, defense-linked buyers, and EV supply chains—who care deeply about security of supply. That demand tailwind from EVs and wind helps. But the rare earth market has a structural trap: China can still move prices dramatically by expanding supply. In 2023 and 2024, China’s Ministry of Natural Resources, along with its industry ministry, raised rare earth mining quotas. The effect rippled globally, pushing prices down and putting pressure on non-Chinese projects. So even with strategic customers, pricing power is never absolute. Buyers know the market can turn.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE

The most valuable end-use for Lynas is permanent magnets, and for high-performance magnets there’s no clean substitute today. That’s why neodymium-iron-boron magnets remain so central to EV motors and wind turbine generators. Substitution does happen at the margins: when shortages looked possible, industries worked to use less. The lighting sector, for example, cut rare earth use as LEDs replaced compact fluorescent bulbs. But for magnets in EVs and wind, the material advantage is hard to replicate.

Competitive Rivalry: LOW-MODERATE

Outside China, there just aren’t many scaled rivals. Lynas remains the world’s largest producer of separated rare earth materials outside of China. China’s dominance creates geopolitical discomfort that, paradoxically, supports demand for suppliers like Lynas. And the industry’s recent history has been unforgiving to would-be competitors: Molycorp filed for bankruptcy in June 2015 after prices fell and a restructuring failed to stabilize the business. MP Materials operates Mountain Pass, but for years its model still relied on sending concentrate to China for processing. In other words, there’s competition—but not much in the way of truly independent, fully built-out rivals.

Hamilton's 7 Powers

Counter-Positioning: Lynas has a structural positioning that Chinese state-backed competitors can’t easily copy. It offers Western-aligned supply with transparent ESG expectations, which matters more when customers are governments, defense-linked buyers, or manufacturers trying to de-risk geopolitical exposure. A Chinese producer can cut prices. It can’t easily become a “trusted Western supplier” without changing the fundamentals of what it is and who controls it.

Cornered Resource: Mt Weld is the foundation. It’s one of the richest rare earth deposits in the world, high grade and long life—an advantage that competitors can’t engineer or purchase later. In mining, geology isn’t a feature; it’s the base layer of strategy. Lynas controls rare earth geology that very few companies on Earth can match.

Scale Economies: Separation chemistry rewards scale. Being the largest non-Chinese producer means Lynas can spread fixed costs across more production and serve multiple markets—Japan, the U.S., and Europe—more efficiently than smaller entrants. In rare earths, scale isn’t just about cost; it’s about operational stability.

Process Power: This is where Lynas has built its hardest-to-copy advantage. Over more than a decade of operating outside China, it has accumulated the kind of real-world learning that only comes from running plants, debugging circuits, improving recoveries, and getting product to spec for demanding customers. Rare earth separation is complex chemistry, and the learning curve is steep. Lynas has climbed it.

Switching Costs: Rare earth customers don’t like surprises. Long-term supply relationships—especially those tied to Japan’s strategy and U.S. defense-linked efforts—create stickiness that goes beyond price. After 2010, many buyers learned that dependency can cost far more than a slightly higher contract.

Network Effects: Limited. Rare earth supply chains are more linear than network-driven, so this power doesn’t meaningfully apply.

Branding: For a commodity company, Lynas has something close to brand equity: it has become shorthand for “non-Chinese rare earths.” That identity is reinforced by government backing and strategic relevance, and it matters in boardrooms where supplier choice is now as much about geopolitics and assurance as it is about dollars per kilogram.

XIV. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case

The bull thesis is that Lynas sits in a rare sweet spot: the only proven, scaled non-Chinese operator in an industry that’s becoming more strategic every year.

Only scaled Western rare earth producer with proven operations. Lynas is the world’s largest rare earth miner outside China, and one of the very few players that can point to a working, end-to-end system: mining, processing, and advanced materials.

EV and wind energy demand set to compound for decades. Permanent magnets are the pull-through demand that matters, and EVs and wind are the engines. The concern for the market isn’t whether demand grows—it’s whether supply can keep up. Some forecasts suggest that without major new capacity or large-scale recycling, neodymium and praseodymium supply could struggle to meet demand over the next decade-plus. Industry projections also point to a fast-growing rare earth market through the 2030s.

Government backing from multiple allied nations. Lynas isn’t doing this alone. Japan, Australia, and the United States have all supported Lynas through financing, regulatory pathways, or strategic partnerships. That support doesn’t guarantee success, but it can lower the cost of capital, reduce certain execution risks, and provide a backstop when private markets get skittish.

Expanding production capacity and resource base. Mt Weld keeps getting better with age. The resource and reserve updates underpin a long runway, with decades of potential production even at expanded rates—exactly the kind of durability customers and governments want in a critical-minerals supplier.

Counter-positioning power against Chinese state enterprises. Lynas benefits from a form of demand that isn’t purely price-driven. For many Western-aligned buyers, “non-Chinese supply” is now a requirement tied to ESG expectations, security concerns, and supply chain resilience. That’s a value proposition Chinese state-backed competitors can’t easily copy without changing what they are.

Bear Case

The bear thesis is that rare earths are still a game played on China’s field—and that makes it brutally hard for anyone else to earn stable returns.

China can flood markets and crush prices at will. China’s Ministry of Natural Resources increased mining quotas in 2023 and 2024, adding supply and pushing down global prices. In practice, that kind of move can compress margins across the industry and leave many non-Chinese projects struggling to break even.

Current profitability is thin. Even with annual revenue rising to AU$556.5 million on higher NdPr production, net profit after tax fell to AU$8.0 million. Returns have been modest—ROE of 0.35% and ROIC of 0.25%—dragged down largely by heavy upfront spending and depreciation.

Texas project faces uncertainty. The U.S. expansion is not a straight line. In August 2025, Amanda Lacaze signalled uncertainty around the project in earnings communications. By November 2025, the project’s status was still described as unlikely to proceed under current conditions. Regulatory complexity and unresolved commercial issues could delay the facility, reshape it, or pause it entirely.

Geopolitical tensions create both opportunity and risk. Policy support is real, but execution can lag rhetoric. And government-backed competitors can reshape local dynamics: MP Materials has received substantial U.S. government support, creating a tougher competitive environment for Lynas in the American market.

Commodity price volatility. Rare earth prices can swing sharply, driven by Chinese policy shifts, supply disruptions, and changes in EV and defense demand. If pricing stays weak for an extended period, Lynas’s revenue and margins can come under pressure—regardless of how strategically important the business looks on paper.

XV. Key KPIs to Watch

If you’re trying to understand where Lynas goes next, don’t get lost in the noise. Three signals tell you most of what you need to know:

1. NdPr Production Volume and Realized Pricing

Everything in this business ultimately rolls up to NdPr—neodymium and praseodymium—the magnet metals that drive the economics. Lynas lifted NdPr production by 22% to 2,969 tonnes, and that output number is the cleanest snapshot of how much “engine” the company is actually running at.

But tonnes alone don’t tell the story. The second half is price: what Lynas actually realizes per kilogram, quarter by quarter. The most revealing comparison is the gap between Lynas’s realized prices and China’s domestic NdPr pricing. If Lynas can consistently sell at a premium for non-Chinese supply, that’s pricing power. If it can’t, it’s back to being judged like any other commodity producer.

2. Operating Cash Cost per Kilogram of NdPr

Rare earths have a nasty habit of turning quickly: prices spike, projects rush in, and then the floor drops out. In that kind of market, cost position is survival.

That’s why the operating cash cost per kilogram of NdPr matters so much. It’s the metric that tells you whether Lynas can stay profitable when prices soften. The key context is the cost gap the market is implying: break-even economics require NdPr prices above $60/kg, versus current Chinese production costs around $48/kg. The wider that gap stays, the thinner the margin for error.

3. Capital Deployment Progress: Mt Weld Expansion, Kalgoorlie Ramp, Texas Development

Lynas is building on multiple fronts at once, and that’s where execution risk lives. During the year, it invested $579.3m in capital and mine development projects. The question isn’t whether Lynas has plans—it’s whether those plans land on time and on budget.

So the KPI here is progress: how smoothly the Mt Weld expansion moves, how quickly Kalgoorlie ramps, and whether the Texas development advances in a way that matches the company’s stated timelines and expectations. In rare earths, capital projects don’t just shape growth—they often determine whether the whole strategy holds together.

XVI. Conclusion: A Strategic Asset in an Uncertain World

The story of Lynas Rare Earths is, at its core, a story about resilience—corporate, geological, and geopolitical all tangled together.

It began as a small Australian gold miner and, through a series of high-stakes pivots and near-misses, became something the West doesn’t have enough of: a scaled producer of separated rare earth materials outside China. Along the way, Lynas survived a blocked Chinese bid for control, a brutal commodity price collapse, years of controversy and legal pressure around its Malaysian plant, and debt loads that threatened to finish the company off. It came out the other side not just alive, but operating—backed, at different moments, by Australia, Japan, and the United States.

Markets noticed. From 31 December 2024 through 28 October 2025, Lynas’s share price rose by roughly 150%, far outpacing the S&P 500’s gain over the same period.

That optimism showed up in its valuation too. As of November 2025, Lynas had a market capitalization of about $9.55 billion. Whether the company grows into that number will hinge on a familiar trio: executing its expansion plans, where rare earth prices go next, and how durable Western policy support proves to be.

Amanda Lacaze has been blunt about the structural reality underneath all of this. “When in the history of the global economy has a monopolist willingly given up their position in the market?” she asked, pointing to China’s rational incentive to preserve dominance.

That one line captures the real challenge. Building an alternative rare earth supply chain is possible—Lynas proved that. But sustaining it against a determined monopolist takes the kind of ingredients that markets rarely provide on their own: patient capital, consistent government commitment, and operational excellence over timelines that don’t fit neatly into quarterly expectations.

For long-term investors, Lynas is still a uniquely positioned asset: direct exposure to the electrification and defense supply chain reshoring trends through the only scaled Western-aligned producer of the magnet materials that make EV motors and wind turbines work. The risks remain real—China can pressure prices, projects can stall, and commodity cycles can turn vicious. But the strategic value of non-Chinese supply is real too, and it’s becoming more valuable as supply chain resilience shifts from a talking point to a policy priority.

Since taking over as Managing Director and CEO in 2014, Lacaze’s pragmatic, survival-first strategy turned Lynas into a cornerstone of the modern rare earth industry—steady enough to be relied on, and rare enough to matter.

In an age of great-power competition and an accelerating energy transition, Lynas has become more than a mining company. It’s become infrastructure: critical infrastructure for the technologies that will define the coming decades.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music