Light & Wonder: The Billion-Dollar Bet on the Future of Gaming

I. Introduction: A Company Reborn

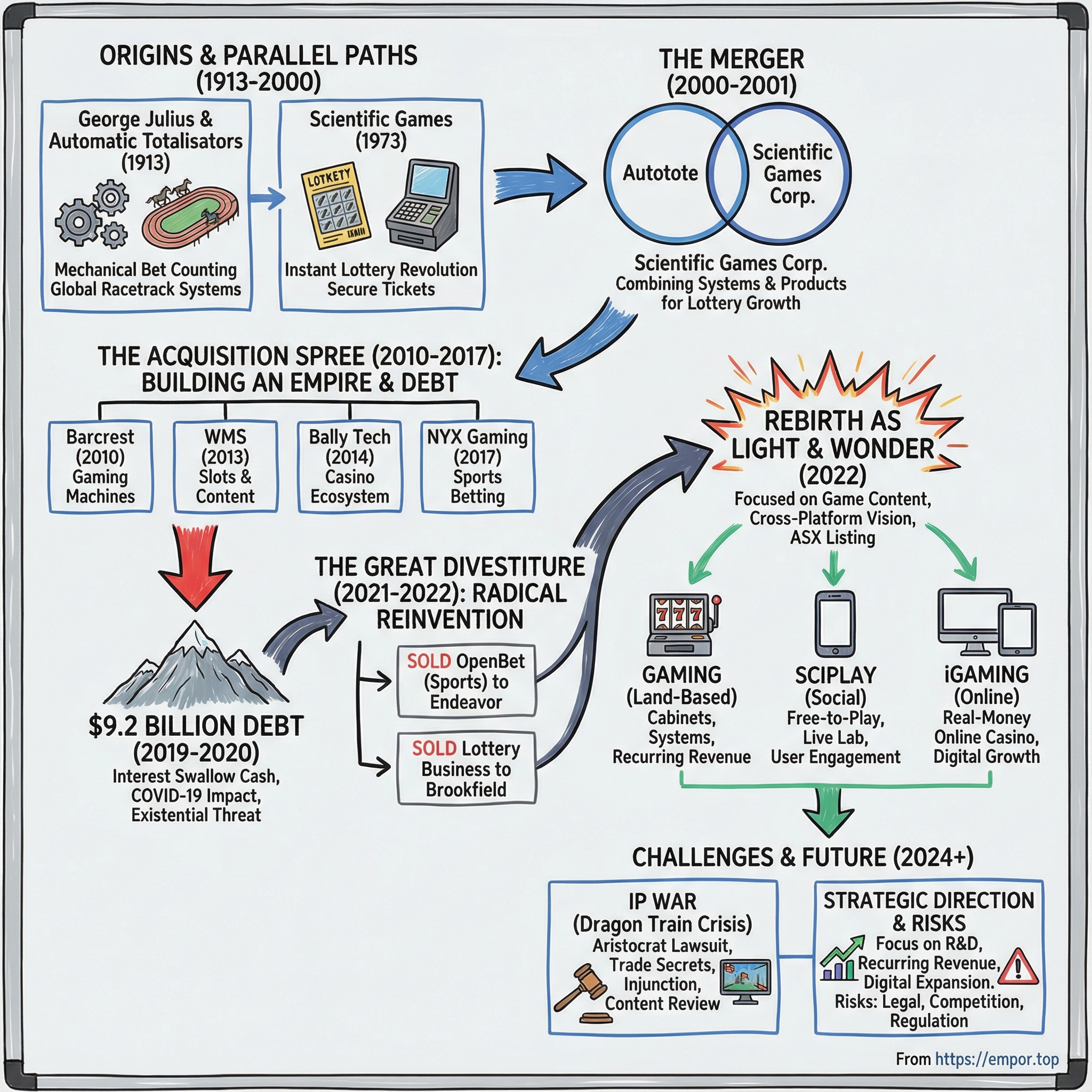

Picture a casino floor in Las Vegas: rows of slot machines, synchronized light shows, that unmistakable soundtrack of near-misses and small victories. Now zoom out one level. Behind all that spectacle sits a supplier most players have never heard of—one that, not long ago, was fighting to survive under nearly $10 billion of debt. To stay alive, it did something almost unthinkable: it sold off the businesses that made it famous.

This is the story of Light & Wonder—the company that chose radical reinvention over a slow, leveraged fade.

Light & Wonder, Inc. (formerly Scientific Games Corporation) is a Las Vegas-based gambling products and services company. On the casino side, it builds and supplies the core machinery of modern gaming: slot machines, table games, shuffling machines, and casino management systems. And it does it under some of the most recognizable legacy brands in the industry—Bally, WMS, and Shuffle Master.

The question at the heart of this story is simple, and kind of wild: how did a company that started by tracking horse racing bets evolve over more than a century—from totalizators, to lottery tickets, to slot machines—and then pull off one of the most dramatic corporate reinventions in gaming?

The breaking point came in 2020. Scientific Games launched a strategic review to deleverage a balance sheet weighed down by $9.2 billion of debt. What followed wasn’t a minor restructuring—it was a corporate metamorphosis. The lottery division, the sports betting platform, the pieces that didn’t fit the future vision: sold. What remained was reshaped into Light & Wonder, a company focused tightly on game content—built to travel across the casino floor, the phone screen, and everywhere in between.

Today, Light & Wonder is one of the three largest players in gaming equipment, squaring off most directly with Aristocrat, the Australian powerhouse with a huge footprint in North American slots. As of Q1 2024, Aristocrat held about 28% of that market, compared to Light & Wonder’s 21%. The third major competitor, International Game Technology, has been undergoing its own shake-up following an acquisition by Apollo Global Management.

And the reinvention hasn’t been subtle. Light & Wonder closed 2024 with record financial and operational performance, delivering record consolidated revenue of $3.2 billion, up 10%, with growth driven by strong results across the business.

But this isn’t just a comeback story. It’s what happens when a century-old company decides the only way forward is to tear itself apart—then rebuild into something sharper, simpler, and more modern. From an Australian inventor’s mechanical breakthrough in the early 1900s to a billion-dollar intellectual property fight with Aristocrat in 2024, Light & Wonder’s journey is both a masterclass in transformation and a reminder of the price of growth-by-acquisition.

II. Origins: George Julius and the Mechanical Marvel (1913-1970s)

Before there were slot machines. Before scratch-offs. Before the casino floor became a software business with lights attached. There was horse racing—and a very analog problem: how do you take, count, and display thousands of bets fast enough that the race can actually start?

Sir George Alfred Julius (1873–1946) was an English-born New Zealand inventor and entrepreneur, and the founder of Automatic Totalisators Ltd. He’s credited with inventing the world’s first automatic totalisator: a machine that could tally wagers and update odds as money flowed in.

To understand why that mattered, you have to picture what came before. Early tracks did this work by hand—totals marked on chalkboards and later on big numerical displays. At small courses, a well-run manual operation could limp along, and some did well into the 1960s. But it was slow, it was error-prone, and it was vulnerable to fraud unless tightly controlled.

And regulators added pressure. One key rule was that the totalisator had to be closed with final, complete totals before any race was run. At major tracks with tens of thousands of gamblers, that requirement could cause maddening delays. The system was begging for automation.

Julius didn’t start out trying to reinvent gambling. His early concept was a mechanical vote-counting machine. When the government rejected it, he repurposed the idea for the racetrack—taking the logic of counting votes and applying it to counting bets.

In whatever spare time he could find, Julius worked on the design for an automatic totalisator. With help from two of his sons, he built a prototype. What they created was revolutionary for its time: effectively a mechanical computer for gambling, able to calculate and display updated totals in real time.

The first machine went live in 1913 at the Auckland Racing Club’s grounds in Ellerslie, a suburb of Auckland. It was designed by Julius and connected to the company that would soon be formalized as Automatic Totalisators Limited.

A detail that captures just how early this was: the machine was entirely driven by clockwork—no electricity at all. It was late-19th-century engineering solving a 20th-century scale problem.

Automatic Totalisators Limited (ATL) was incorporated on 21 April 1917 to manufacture, install, and operate totalisator systems worldwide. Julius served as a director and major shareholder, and as consulting engineer.

From there, the footprint spread. The first UK installation arrived in 1928 for greyhound racing. In 1932 came the first American installation at Hialeah Park in Florida. And orders kept coming—enough to keep Julius’s broader firm, Julius, Poole & Gibson, solvent through the Great Depression.

After World War II, demand surged. Between 1948 and 1955, ATL carried out installations at 99 racetracks around the world, spanning places like Thailand, Scotland, the Philippines, South Africa, Pakistan, Iraq, Argentina, Chile, and Venezuela.

Over time, the U.S. arm evolved into what became known as Autotote. In 1978, it was renamed Autotote Ltd., reflecting that it was no longer just a totalisator company—it was diversifying into lottery systems, off-track betting, and slot machine accounting. In 1979, Autotote Ltd. was acquired for $17 million by a group led by Thomas H. Lee Co.

The theme that will keep repeating for the next hundred years starts right here: this was never just gambling. It was technology applied to gambling—automation as legitimacy, speed as a competitive advantage, and systems as the product.

Julius was knighted in 1929 and later became the first chairman of Australia’s Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (now CSIRO). But his most enduring legacy may be this: he helped turn wagering from a chaotic, manual operation into an engineered system—laying the first brick in the path that eventually leads to Light & Wonder.

III. The Scientific Games Parallel Story (1973-2000)

While Autotote was busy automating horse racing—turning chaos into a clean, auditable system—a different kind of gambling was about to get its own technology upgrade. Not at the track, but at the corner store.

Scientific Games was founded in 1973. A year later, it introduced the first secure instant lottery ticket.

That single idea—instant results, right in your hand—changed the lottery business. In 1974, Scientific Games and the Massachusetts Lottery launched the world’s first secure instant “scratch-off” game. Up until then, most lotteries were built around scheduled drawings. You bought a ticket, you waited, and you hoped.

Scratch-offs collapsed that waiting time to seconds. And in gambling, speed is oxygen.

The company’s origin story was almost comically scrappy. The concept was developed by American computer scientists John Koza and Daniel Bower in 1974. Koza had been working for a company that printed bingo cards for U.S. grocery stores, and he could see the next step: a lottery product that delivered immediate gratification—something even illegal operators couldn’t reliably replicate at scale.

After Koza was laid off, he and fellow out-of-work colleague Dan Bower started Scientific Games themselves. Two guys. An apartment in Ann Arbor, Michigan. A kitchen table in Chicago. And a pitch: give state lotteries a product people could buy on impulse and resolve on the spot.

They took that pitch to state lottery associations. Massachusetts became the first to say yes in 1974, and it kicked off what became the instant-win revolution.

But there was a catch, and it was existential: security. The big fear wasn’t just fraud—it was counterfeiting. If a scratch-off ticket could be duplicated or faked, the whole concept would collapse under scandal and lost trust. So Koza pulled in additional creative minds to develop a secret coating designed to make tickets extremely difficult to forge.

When the tickets hit stores, the response wasn’t mild curiosity—it was a stampede. On May 29, 1974, people walked into convenience stores and gas stations across Massachusetts and saw that first scratch-off. One liquor store owner called it “instant insanity.”

And it wasn’t a one-off novelty. Demand for these colorful, algorithm-driven games surged. By 1981, Scientific Games supplied 85% of the U.S. lottery market.

The ripple effects went beyond consumer behavior. In 2007, The New York Times credited Scientific Games and GTECH with helping transform lotteries from something “historically [as] an underground operation run by mobsters” into “a lucrative, state-sponsored corporate enterprise.”

By the late 1990s, the trajectories were clear. Autotote had the systems backbone and decades of operational credibility. Scientific Games had the product that made lotteries explode. Two companies—one born at the racetrack, the other at a kitchen table—were heading toward the same conclusion: together, they could become something much bigger.

And, as we’ll see, they would. But that merger wouldn’t just build a gaming infrastructure powerhouse. It would also set the stage for the leveraged growth strategy that nearly broke the company later on.

IV. The Merger That Changed Everything (2000-2001)

By the time the calendar flipped to 2000, Autotote and Scientific Games were solving two halves of the same problem.

Autotote owned the plumbing—the systems that tracked wagers and moved money reliably. Scientific Games owned the product people actually touched: secure instant tickets, the scratch-offs that had turned lottery into a high-frequency habit. Put the two together and you didn’t just sell equipment. You could sell an end-to-end infrastructure stack—from printing the ticket to validating the win.

So in 2000, Autotote bought Scientific Games Holdings Corp. for $308 million.

A year later, the combined company made the symbolism official: Autotote renamed itself Scientific Games Corporation.

That name change did more than freshen the letterhead. It was a declaration of where management thought the world was going. The company’s heritage had been racetracks and totalizators—mechanical roots, systems-first, built for an era of parimutuel wagering. But the growth was increasingly elsewhere: state lotteries scaling across the U.S., casinos proliferating, and gambling becoming more regulated, more digitized, and more standardized.

And yet, the old business was still massive. By 2002, Autotote computers tracked about two-thirds of the roughly $20 billion wagered annually on racing in North America. The difference was that racing was mature. Lottery was still expanding—and Scientific Games was quickly becoming the default technology provider.

More importantly, this merger set the company’s next operating rhythm: buy capabilities, stitch them together, repeat. For a long time, it worked. And it also quietly laid the foundation for the leverage-heavy acquisition strategy that, years later, would bring the whole enterprise to the edge.

V. The Acquisition Spree: Building a Gaming Empire (2010-2017)

After the Autotote–Scientific Games merger, the company found a playbook that seemed unstoppable: buy its way into the next adjacent piece of gambling technology. It wasn’t enough to supply lotteries. The ambition was to become a one-stop shop for the entire casino ecosystem—machines, content, systems, and eventually digital.

The Barcrest Acquisition (2010)

The first big step came in 2010, when Scientific Games acquired the UK-based gaming company Barcrest from IGT. Barcrest owned Deal Games and produced betting and gambling terminals. More importantly, it was a clear signal: Scientific Games was pushing into gaming machines, a world ruled by giants like IGT and Aristocrat.

The WMS Industries Deal (2013)

In October 2013, Scientific Games bought WMS Industries—at the time the third-largest slot machine manufacturer—for $1.5 billion.

This one changed the company’s identity. WMS brought proven slot franchises, a deep bench of game designers, and entrenched relationships with casino operators. Overnight, Scientific Games wasn’t just selling lottery products and back-end systems. It had a real seat at the slot-machine table.

But there was a human side to the integration too. Lottery is a government-contract business: long sales cycles, compliance-heavy, relationship-driven. Slot machines are the opposite: ruthless competition for floor space, constant content refreshes, and performance measured in player engagement. Folding WMS into a lottery-first company wasn’t just an operational challenge—it was a cultural one.

The Bally Technologies Mega-Deal (2014)

Then came the mega-deal. In 2014, Scientific Games announced it had completed its merger with Bally Technologies. The aggregate transaction value was approximately $5.1 billion, including the refinancing of roughly $1.8 billion of Bally net debt. In the company’s words, it was about bringing together “two exceptional organizations” with a shared culture of innovation and customer focus.

Strategically, the deal was a land grab. Bally nearly doubled the company’s size and dramatically expanded its footprint in gaming equipment.

Bally’s own history reads like a corporate shapeshift: founded in 1968 as Advanced Patent Technology, later renamed Alliance Gaming, then in 1996 it acquired Bally Gaming International (a former division of Bally Manufacturing). By 2006, the company fully adopted the Bally name.

And Bally didn’t show up alone. In November 2013, it had acquired SHFL entertainment, bringing in a lineup of casino “utility” products—Deck Mate card shufflers and roulette chip sorters—plus proprietary table games, electronic table systems, electronic gaming machines, and iGaming capabilities.

The pitch for all of this was synergy: a portfolio broad enough to cross-utilize content and technology across lottery, gaming, and interactive markets, and to expand Scientific Games’ range of social and real-money iGaming and iLottery products and services.

With the deal closed, Las Vegas-based Bally became a wholly owned subsidiary of New York-based Scientific Games. CEO Gavin Isaacs rolled out a new executive management structure for what was now one of the industry’s most diversified global gaming suppliers.

The NYX Gaming Acquisition (2017)

In September 2017, Scientific Games kept going, announcing a $631 million acquisition of NYX Gaming Group Limited. With NYX came OpenBet, a sports-betting platform that, as of 2018, handled about 80% of all sports betting in the UK.

It was a huge strategic foothold in sports betting—especially with the U.S. market on the verge of opening up after the Supreme Court’s 2018 decision striking down the federal ban.

The Hidden Cost: Debt Accumulation

There was one constant across all these deals: they were financed primarily with debt.

At the time, the logic felt clean. Buy valuable assets, stitch them together, realize synergies, and let the bigger cash flows gradually pay down what you borrowed. The problem was pace. Scientific Games kept acquiring faster than it could de-risk.

By the late 2010s, it had built something sprawling: lottery, gaming equipment, social gaming, and sports betting under one roof. It was an empire—and it was also a balance sheet waiting for the wrong shock.

VI. The Debt Crisis: $9.2 Billion in the Hole (2019-2020)

By 2020, the acquisition spree had left Scientific Games with a balance sheet that was starting to feel less like leverage and more like gravity. The company launched a strategic review with one clear objective: deleverage. At the center of the problem was $9.2 billion of debt.

That number wasn’t just big. It was debilitating. Interest payments were swallowing up cash that could have gone into new games, new platforms, and the people who build them. In good times, that kind of structure is stressful. In bad times, it can be deadly.

And then the bad times arrived.

COVID-19 hit, and the places where Scientific Games made its money went dark. Casinos around the world shut down. Lottery sales fell. Revenue tightened just as the company’s fixed obligations stayed stubbornly the same. The debt that had looked serviceable in a normal environment suddenly looked like an existential threat.

So the company ran into a question with no comfortable answer: how do you save a business that’s drowning in debt without cutting away the very growth engine you built?

The usual options weren’t enough. Cost-cutting can’t erase billions. Refinancing might buy time, but it doesn’t change the underlying math. And asset sales threatened to break the “integrated gaming” strategy that had justified the whole roll-up in the first place.

Scientific Games chose the option that sounded like heresy: sell everything that isn’t the future. Strip down to what it believed could win long-term—casino gaming content and platforms—and let the rest go.

The first step had actually come just before the crisis. In 2019, Scientific Games took its social gaming division, SciPlay, public—selling a minority stake in an IPO while keeping control of the business. It was a way to unlock value without giving up the asset.

But the bigger decision was still ahead. The company ultimately chose to sell its lottery and sports betting businesses to focus on its casino gaming business.

This wasn’t routine portfolio pruning. It was a full identity rewrite. Scientific Games was preparing to part with the lottery division that traced back to the company’s roots in 1973, and the sports betting platform it had bought only a few years earlier. The message was unmistakable: nothing was sacred, and everything was for sale—if it helped the company survive and reset.

VII. The Great Divestiture: Selling the Soul to Save the Company (2021-2022)

What followed was one of the most sweeping corporate pivots in modern gaming. Scientific Games didn’t just trim around the edges. It put entire pillars of the company on the market—raising more than $7 billion in proceeds and setting up a future that looked nothing like its past.

Selling OpenBet (Sports Betting)

In 2021, Scientific Games announced a definitive agreement to sell its sports betting business, OpenBet, to Endeavor Group Holdings, Inc. The deal was valued at $1.2 billion in a mix of cash and stock: $1 billion in cash and $200 million in Endeavor Class A common stock.

“This transaction represents the culmination of a thorough process to divest OpenBet in order to maximize value for our shareholders and rapidly advance our vision to become the leading cross-platform global game company,” said Barry Cottle, President and CEO of Scientific Games. He called it a milestone in “optimizing our portfolio and de-levering the balance sheet.”

The subtext was even clearer: OpenBet had only come in the door four years earlier, via the NYX deal. Selling it so soon was an admission that Scientific Games couldn’t be world-class across lottery, slots, social, and sports betting all at once—not with that debt load hanging over everything.

Selling the Lottery Business

Then came the deal that would have sounded impossible a few years earlier. Scientific Games entered into a definitive agreement to sell its Lottery business to Brookfield Business Partners L.P., together with institutional partners, for $6.05 billion—mostly cash, plus an earn-out tied to EBITDA targets in 2022 and 2023.

This wasn’t a small division. It was a global lottery partner with long-standing relationships with roughly 130 lottery entities across more than 50 countries.

And the irony landed with full weight: the company was selling the business whose name it carried. The lottery operation that traced back to the scratch-off breakthrough in 1974 would leave—and it would take the Scientific Games brand with it. Brookfield ultimately completed the acquisition, and the divested lottery company continued operating under the Scientific Games name, the one established in 1973.

The Deleveraging Impact

Together, these divestitures didn’t just generate headlines—they rewired the balance sheet. Scientific Games used the proceeds to retire major chunks of debt, including a $4.0 billion term loan and $3.0 billion in secured and unsecured notes. Outstanding debt fell from $8.8 billion to about $4.0 billion, and net leverage dropped from 6.2x to below 3.9x.

This wasn’t financial cosmetics. It was oxygen.

With the pressure of the debt finally easing, the company could stop trying to be everything to everyone—and instead commit to a simpler identity: a focused gaming business built around creating game content that could travel across platforms.

VIII. Rebirth: Light & Wonder Emerges (2022)

With the lottery business gone—and the Scientific Games name going with it—the remaining company faced an unusually literal problem: it needed a new identity for a new life. In March 2022, it announced it would rebrand as Light & Wonder.

And yes, the name wasn’t pulled from a hat. It came from a full-on naming process that CEO Matt Wilson later described as both foreign and exhaustive:

“I had never been through a rebranding before. We brought in all these professionals that do this for a living. We hired linguists to come up with names that sound great and conjure up the right experience. We went through 2,700 options that we could trademark and we decided on Light & Wonder.”

The symbolism was deliberate—meant to evoke innovation, creativity, and a forward-looking approach to digital entertainment. But the deeper point was more practical: this wasn’t a legacy lottery-and-everything-else conglomerate anymore. It needed a brand that matched what it had decided to become.

Wilson also framed the rebrand around who the name was really for:

“We went through and said there really are three stakeholders that we care about. We have our shareholders, they really care about whether the stock price is going up or down, they don't really care what you're called. You've got customers. They care about what you're called, but they really care about the quality of the product and whether you deliver on your commitments. So if you do those things, they don't really care what you're called. The third and most important cohort is employees—current employees and future employees.”

That last point matters, because the strategic focus was now straightforward and ambitious: build game franchises once, and let them travel everywhere—onto casino floors, onto phones, into online casinos, and into free-to-play social gaming.

A couple months later, in May 2022, Light & Wonder listed on the Australian Securities Exchange. The logic was that Australia—home to rival Aristocrat—had deep institutional familiarity with gaming companies.

Even as the corporate name changed, the product brands didn’t. Bally remained one of Light & Wonder’s three core legacy brands, alongside WMS and Shuffle Master—names that still carry real weight with casino operators who’ve been buying, leasing, and servicing that equipment for decades.

And the company kept tightening the story around where it wanted investors to find it. Light & Wonder confirmed that its delisting from Nasdaq was expected to take effect prior to the open of trading on November 13, 2025 (EST). The transition to a sole ASX primary listing was positioned as aligning its capital markets footprint with its long-term growth plans and shareholder base.

“Since we launched the secondary ASX listing back in May 2023, equity traded on the ASX now accounts for approximately 37% of our total equity,” said Light & Wonder chairman Jamie Odell.

IX. The Current Business Model: Three Pillars of Gaming

After selling off lottery and sports betting, Light & Wonder reorganized around a simple idea: build great game content once, then let it move wherever players are. Today the company runs three segments—Gaming, SciPlay, and iGaming. They serve different markets, but they’re designed to feed one another, so successful franchises can travel across platforms.

Gaming (Land-Based)

The Gaming segment is still the physical foundation: game content and slot machines, video gaming terminals and video lottery terminals, plus conversion kits, spare parts, and the table-game workhorses that casinos quietly rely on—automatic card shufflers, deck checkers, roulette chip sorters, and more.

In 2024, Light & Wonder shipped 43,600 gaming units worldwide.

It also runs a meaningful leasing business. Instead of selling a machine once and walking away, Light & Wonder can place machines on casino floors and collect recurring fees. That creates steadier revenue and keeps the relationship alive long after the initial install.

SciPlay (Social Gaming)

SciPlay is the company’s free-to-play social casino engine—mobile games that look and feel like casino experiences, but where players aren’t wagering real money. Instead, they buy virtual currency and in-game items.

In 2024, SciPlay revenue reached $821 million, up 6%.

The strategic value is bigger than the dollars. Social games can act like a live laboratory: new mechanics, new themes, new math models—tested at scale, refined quickly, and then, when something hits, ported to other channels. A winning idea can prove itself on a phone screen before it ever earns a spot on a real casino floor.

iGaming (Online Real-Money)

Then there’s iGaming: real-money online casino content. As online gambling expands, Light & Wonder has positioned itself as a major supplier through its OpenGaming platform, which connects operators, players, and third-party game developers to deliver digital casino experiences.

In 2024, iGaming revenue grew 9% to $299 million.

Conceptually, iGaming sits right between the other two segments. It’s the bridge between land-based casino content and the fast-iterating world of social. And as more U.S. states legalize online gambling, it becomes an increasingly important growth lane for the company.

Light & Wonder describes itself as the leading cross-platform global games company, built on three complementary businesses and a team of more than 6,500 people—focused on creating content that players recognize and want to engage with, wherever they choose to play.

X. The Dragon Train Crisis: An IP War with Aristocrat (2024-2025)

For years, the slot-machine business lived with a kind of unspoken rule: you can chase what works, you can echo a theme, you can borrow a vibe. But you can’t take the secret sauce—the proprietary math and mechanics that make a game perform. In 2024, that line became the center of a very public fight when Aristocrat sued Light & Wonder over Dragon Train.

Aristocrat’s complaint, filed February 26, 2024, targeted two Light & Wonder titles. It alleged trade secret misappropriation tied to Dragon Train, and trade dress and copyright infringement, plus related claims, tied to Jewel of the Dragon.

The case quickly turned from “industry dispute” to “existential threat,” because the early read from the court went Aristocrat’s way. Judge Gloria Navarro agreed that Aristocrat had sufficiently established the existence of trade secrets and showed a likelihood of success on its argument that Light & Wonder violated those trade secrets while developing Dragon Train—specifically around Aristocrat’s Dragon Link game. A key detail in the background: Light & Wonder had hired former Aristocrat engineer Emma Charles, who worked on the Dragon Train development team.

In explaining the decision, the court’s language was blunt. It said that by misappropriating trade secrets relating to Dragon Link and Lightning Link, Light & Wonder was able to develop Dragon Train “without investing the equivalent time and money.” And in granting a preliminary injunction, the court emphasized the public interest in “protecting trade secrets and preventing competitors from receiving an unfair advantage.”

The facts that surfaced were ugly. Emma Charles had done under-the-hood work on Dragon Link at Aristocrat. She left and joined Light & Wonder in mid-2021. During the case, she was found to possess a spreadsheet that matched Aristocrat’s exactly—down to a 2013 creation date, years before she ever worked at Light & Wonder.

That was enough for Judge Navarro to issue the preliminary injunction, forcing Light & Wonder to pull Dragon Train. And because courts typically reserve preliminary injunctions for cases where the evidence points strongly toward the plaintiff, the market read it as more than a temporary setback. Charles’ employment with Light & Wonder ended a few days later.

Operationally, Light & Wonder moved fast. Its North American Gaming installed base included about 2,200 Dragon Train-themed units. Within the required window, the company replaced and/or converted roughly 95% of them with other games from its portfolio.

Financially, Light & Wonder stressed that Dragon Train wasn’t the whole story: its pre-ruling estimate of 2025 consolidated AEBITDA attributable to Dragon Train was less than 5% of its $1.4 billion target. But investors weren’t in the mood to split hairs. Light & Wonder shares dropped more than 17.5% on the news.

And the fight didn’t stop with the injunction. On March 14, 2025, Aristocrat filed a second amended complaint in the District Court of Nevada, adding a trade secret misappropriation claim against Jewel of the Dragon.

Aristocrat also pushed a broader theory: that replacement and follow-on titles for Dragon Train—including Dragon Train Grand Central, and even a social game release—could still “reap the benefits” of the alleged trade secret misappropriation, even if none of the claimed trade secrets were used in those later games.

There’s an extra layer of tension here, and it’s personal. Light & Wonder CEO Matt Wilson is a former Aristocrat executive, as are several other senior leaders. Before joining Light & Wonder, Wilson served as President and Managing Director, Americas at Aristocrat, and previously held roles including Senior Vice President of Global Gaming Operations and Senior Vice President of Sales and Marketing, Americas. Light & Wonder’s chairman, Jamie Odell, and director Toni Korsanos also came from Aristocrat.

That kind of leadership lineage cuts both ways. It can be a competitive advantage—deep understanding of how the market leader operates. But it also raises the stakes in court, because the more talent that crosses over, the more scrutiny follows about what came with them.

XI. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

After the debt reset and the Dragon Train shock, the obvious question is: what kind of competitive position does Light & Wonder actually have now? One way to make sense of that is to zoom out and look at the structure of the industry, and then zoom back in on what, if anything, is truly durable about Light & Wonder’s advantage.

Porter's Five Forces:

1. Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MEDIUM

In land-based gaming, the front door is guarded by regulation. You need licenses, approvals, and a track record in every jurisdiction you want to operate in. On top of that, slot machines aren’t an “app store” business—you need manufacturing capability, distribution, field service, and deep R&D just to get a product onto a casino floor. And casinos tend to stick with incumbents they trust.

But digital changes the shape of the threat. In iGaming, content-only entrants can show up without building hardware, which lowers barriers and increases the number of credible competitors. The fight shifts from manufacturing scale to speed, creativity, and distribution.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

Light & Wonder is relatively insulated here because it builds much of what it sells. It manufactures hardware and develops content largely in-house, supported by manufacturing facilities in places including Las Vegas, Sydney, and Barcelona, plus studios accumulated through acquisitions. That vertical capability reduces dependency on any single external supplier.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM-HIGH

The buyers—casino operators—are sophisticated and increasingly consolidated, which gives them leverage. They also have real alternatives: Light & Wonder competes head-to-head with Aristocrat, IGT, and others for the same floor space.

That said, a hit game is a negotiating chip. If a franchise is pulling players in, operators are reluctant to remove it, because swapping out a popular machine isn’t just a vendor change—it’s a revenue risk. This is where content quality can partially offset buyer power.

4. Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM-HIGH

Casinos aren’t competing only with other casinos. They’re competing with every other place a person can spend their gambling budget and attention: online gambling, sports betting, daily fantasy sports, and social casino games (including Light & Wonder’s own SciPlay). In some markets, cryptocurrency casinos add another substitute option.

In the U.S., iGaming is still limited—licensed in only six states—but it’s growing quickly, nearly as fast as sports betting. Even without nationwide legality, the direction of travel is clear: more digital, more convenient, more competition for time and spend.

5. Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a knife fight. As of Q1 2024, Aristocrat held about 28% of the North American slots market, versus Light & Wonder at about 21%, and those share points are fought for title by title.

And the competitive landscape is getting more crowded at the top. International Game Technology PLC and Everi Holdings Inc. agreed to be acquired in a set of transactions by a newly formed holding company owned by funds managed by affiliates of Apollo Global Management, an all-cash deal valuing the acquired businesses at approximately $6.3 billion on a combined basis. Apollo has completed that acquisition and said the two businesses will be integrated into a combined enterprise in the coming months.

The result is a newly formidable competitor with roughly $2.6 billion in combined revenue and meaningful scale across gaming systems, fintech, iGaming, and payments. In an industry where game content has a limited shelf life and players constantly demand novelty, rivalry stays high by default—and any player that slows down gets punished.

Hamilton's 7 Powers:

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE

Scale helps—especially in manufacturing and in spreading game development costs across land-based, social, and iGaming channels. But scale isn’t rare in this market. Aristocrat and other major competitors have it too, which makes this more of a requirement to compete than a lasting moat.

2. Network Effects: WEAK

Most casino gaming isn’t networked in a way that naturally compounds. The strongest network-like dynamic is progressive jackpots: bigger networks can offer bigger jackpots, which can attract more play. SciPlay’s social products can have mild social network effects as well. But overall, this isn’t a business where network effects reliably lock in long-term dominance.

3. Counter-Positioning: STRONG (historically)

Light & Wonder’s 2020–2022 transformation was classic counter-positioning: it sold off lottery and sports betting to become singularly focused on game content across platforms. That focus created a clearer identity and a cleaner capital structure than the old conglomerate model.

Meanwhile, competitors took different paths. The new IGT remains diversified, and Aristocrat has pursued digital opportunities as part of a broader strategy. With iGaming growing quickly—even while only legal in six U.S. states—Light & Wonder’s more established iGaming posture stands out as a meaningful point of differentiation, especially relative to Aristocrat’s later push into the segment.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE

Switching costs vary by what’s being sold. Casino management systems can be sticky and expensive to replace. Individual game content is easier to swap out—operators can replace machines or themes if performance drops. Still, there are operational frictions: training, integrations, and the real-world hassle of changing out equipment. Those frictions create some stickiness, but they aren’t absolute.

5. Brand: MODERATE-STRONG

In casino supply, brand matters in a very specific way: credibility with operators and recognition with players. Legacy names like Bally and WMS still carry weight on the operator side. And on the player side, recognizable franchises and themes can influence where people sit and how long they play. Brand isn’t everything, but it helps turn good games into repeatable demand.

6. Cornered Resource: WEAK-MODERATE

The most defensible resource in this business is intellectual property—especially the math models and mechanics that drive game performance. The Dragon Train case is a stark illustration of both sides of that coin: IP is valuable enough to trigger major litigation, and any hint of compromised IP can become a strategic and reputational crisis.

7. Process Power: EMERGING

One advantage Light & Wonder is clearly trying to systematize is cross-platform game development: build a franchise and deploy it across land-based cabinets, social casino apps, and real-money iGaming. If the company can make that repeatable—faster iteration, smoother porting, better testing loops between SciPlay and casino content—that becomes process power: an internal machine for producing hits more reliably than peers.

XII. Leadership and Strategic Direction

To understand Light & Wonder’s reinvention, you have to understand who’s steering it—and what they’re optimizing for.

The Board named Matt Wilson President and CEO, and added him to the Board, effective immediately. Wilson had been serving as interim CEO since August 2022, and before that he ran the company’s Gaming business.

He came into the job with nearly two decades in the gaming industry and a reputation for driving growth. As Light & Wonder’s Executive Vice President and Group Chief Executive of Gaming, he owned the engine room: product development, manufacturing, supply chain, and sales across the company’s gaming products, systems, and services.

And, like we saw in the Dragon Train saga, Wilson’s resume also explains the intensity of the rivalry. He spent almost 16 years at Aristocrat, including as President and Managing Director, Americas, responsible for commercial operations across the region. He also served as Senior Vice President of Global Gaming Operations, where he focused on building and scaling recurring-revenue strategies—the exact kind of playbook that matters in a slots market dominated by leased fleets, long-term installs, and content that has to earn its keep every day.

Wilson has been explicit about what the new Light & Wonder is trying to be:

"What we are today is a pure play content and platforms business. We make games and platforms, the research-and-development engine, the center of our universe and the reason we exist."

He’s also been clear about what had to change—and why the divestitures weren’t just financial triage, but strategic focus:

"As Scientific Games was trying to be world class at lottery, world class at sports platforms and world class at content was really hard. The way I like to say it, in the old Scientific Games, a dollar of investment in our R&D engine would go to building a great lottery experience, a portion of that would go to building a great sports experience and a portion of that would go to content. Now, in the new Light & Wonder, every dollar of investment that we make in games can go across all of these three businesses."

XIII. Recent Financial Performance and Acquisitions

By the end of 2024, Light & Wonder wasn’t just telling a cleaner, more focused story—it was starting to put real momentum behind it. CEO Matt Wilson summed up the year like this: “We ended a strong 2024 with continued double-digit revenue and earnings growth for the year. The Gaming machine sales share gains in North America and Australia this year are a testament to our R&D investment, commercial strategy and robust product roadmap.”

That momentum carried through the year. In the third quarter, the company reported its ninth consecutive quarter of double-digit consolidated revenue growth year-over-year, alongside continued cash flow generation. It also returned capital to shareholders, buying back $44 million of stock.

The balance sheet—once the thing that nearly sank the entire enterprise—kept improving too. As of September 30, 2024, Light & Wonder reported $3.9 billion in principal face value of debt outstanding, with net debt leverage at 2.9x. That was down from the end of 2023 and remained within the company’s targeted leverage range of 2.5x to 3.5x.

At the same time, management made it clear the reinvention didn’t mean standing still. Light & Wonder continued to pursue strategic acquisitions, and on February 18, 2025, it announced an agreement to acquire Grover Gaming’s charitable business for an upfront $850 million, subject to customary purchase price adjustments. The deal was expected to be funded through a combination of existing cash and incremental debt financing.

Grover Gaming is a leading provider of electronic pull-tabs, distributed across five fast-growing U.S. states: North Dakota, Ohio, Virginia, Kentucky, and New Hampshire. For Light & Wonder, the move further diversified the business into a cash-flow-rich niche with cross-selling potential.

The company also closed the book on a long-running legal issue. On February 23, 2025, it entered into an agreement to pay $72.5 million to resolve antitrust claims related to its automatic card shuffler business, stemming from the 2019 case TCS John Huxley America, Inc., et al. v. Scientific Games Corporation, et al.

XIV. Myth vs. Reality: Separating Narrative from Fundamentals

Myth: Light & Wonder emerged from the Scientific Games transformation as a stronger company.

Reality: It depends on what you mean by stronger. The deleveraging was both necessary and effective. Light & Wonder cut the weight that was crushing the business and bought itself real financial flexibility. But the trade was real too: the transformation meant walking away from businesses that generated billions in revenue and held defensible positions in their own markets. The lottery operation has continued to thrive under Brookfield’s ownership, and OpenBet has been folded into Endeavor’s sports betting strategy. Light & Wonder swapped diversification for focus—and that bet will look brilliant or constraining depending on how the gaming industry evolves.

Myth: The Dragon Train litigation is a minor setback.

Reality: The dollars may be small, but the implications could be big. Management has emphasized that Dragon Train itself was expected to represent less than 5% of targeted AEBITDA. But the case spotlights a more uncomfortable risk: not just one game, but a category. “Hold and spin” has been one of the hottest mechanics in slots, and if the court ultimately sides with Aristocrat, a meaningful portion of Light & Wonder’s output over the last several years could come under scrutiny.

That’s why the company said, “Given our identification of these historical Aristocrat PAR sheets, we are expanding the scope of the review we conducted following the preliminary injunction to include all hold and spin games released before mid-2021.”

In other words: this isn’t only about pulling a title. It’s about making sure the engine that produced it isn’t compromised.

Myth: Light & Wonder’s cross-platform strategy is unique.

Reality: It’s a real differentiator—just not a permanent one. Light & Wonder has built a coherent thesis around creating franchises that can travel from land-based casinos to iGaming to social casino. That matters, and it’s helped define the post-divestiture company. But rivals aren’t standing still. Aristocrat has been investing heavily in digital, and the newly combined IGT entity brings gaming and digital under one roof as well. Cross-platform is an advantage today, not a monopoly on the future.

XV. Key Performance Indicators and Investor Considerations

If you’re trying to understand whether Light & Wonder’s post-reinvention story is really working, there are three numbers worth keeping an eye on—because they map directly to the company’s strategy: build recurring revenue, win floor space, and keep expanding digitally.

1. Gaming Operations Installed Base Growth

Light & Wonder doesn’t just sell machines. It also leases them—and that leased footprint is the closest thing the company has to an annuity. More units on casino floors means more recurring revenue, more operator dependence, and more staying power for the underlying game franchises.

Recently, the company grew that base meaningfully, adding more than 850 North American Gaming Operations units sequentially and more than 2,700 year-over-year. The exact quarterly fluctuations matter less than the direction: if the installed base keeps rising, it’s a sign casinos are choosing Light & Wonder content often enough to give it long-term real estate.

2. Ship Share in North America and Australia

Ship share is the scoreboard for the slot-machine arms race. It’s the percentage of new machine shipments that go to Light & Wonder instead of rivals—and because casinos constantly refresh floors, share here is a live indicator of who’s winning right now.

In Australia, Light & Wonder likely pushed past 20% ship share, helped by the newly launched Dragon family of slots. That stands out because Australia is Aristocrat’s home turf, and Aristocrat controls about half the slot machine market there. Any meaningful share gain in that environment is hard-earned.

3. iGaming Revenue Growth

Then there’s iGaming—where the company’s “cross-platform” ambition either turns into a flywheel, or it doesn’t.

As online gambling expands in the U.S., iGaming is Light & Wonder’s clearest long-term growth lane. The OpenGaming platform gives it a strong place in the ecosystem, connecting operators and game content. But in digital, position is only the starting point. What matters is execution: consistent content output, reliable platform performance, and the ability to turn land-based hits into online winners fast enough to stay ahead.

XVI. Material Risks and Regulatory Considerations

Legal Overhang

The Aristocrat litigation is the most immediate, most visible risk hanging over Light & Wonder. Even if Dragon Train itself was a small slice of earnings, a worse-than-expected outcome could force the company to pull more games, strain relationships with casino customers who hate disruption, and invite copycat claims from other IP holders watching closely.

Competitive Intensity

In this market, the real weapons aren’t just cabinets and distribution—they’re ideas encoded into software. Intellectual property fights have been heating up, and Light & Wonder and Aristocrat remain in U.S. litigation over source-code ownership, a reminder that proprietary math libraries and codebases are strategic assets worth going to war over.

At the same time, the competitive field is getting tougher at the top. The Apollo-backed IGT–Everi combination creates a well-capitalized competitor with meaningful scale—and private equity resources behind it.

Regulatory Concentration

There’s also a geography risk baked into the numbers. About 70% of Light & Wonder’s revenue comes from North America. That concentration is great when the market is growing, but it also means changes in regulation, taxation, or even regional economic conditions could hit results harder than they would for a more globally balanced competitor.

Listing Transition Risk

Then there’s the company’s own capital-markets transition. Light & Wonder has warned that actual results could differ materially due to risks and uncertainties, including the risks of transitioning—or failing to transition—to a sole primary listing on the ASX. Delisting the company’s common stock from Nasdaq could reduce liquidity, pressure trading prices, affect access to capital markets, and lead to less or different disclosure about the company.

XVII. Conclusion: A Century in the Making

Light & Wonder’s story stretches across more than a century—from George Julius’s clockwork totalizator in 1913 to a Las Vegas courtroom fight over Dragon Train in 2024. And running through it is a pattern: reinvention. Sometimes strategic. Sometimes forced.

The company that exists today barely resembles Automatic Totalisators Limited, incorporated in 1917. The lottery business that defined Scientific Games for decades now operates under Brookfield’s ownership, carrying the Scientific Games name with it. The sports betting platform that came in through NYX now sits with Endeavor. What’s left is the core that management decided was the future: a pure-play games and platforms company, obsessed with making content that performs.

And at least in the numbers, the post-reset company has kept moving. In the third quarter of 2025, revenue reached $841 million, reflecting continued top-line strength, while net income rose 78% to $114 million.

But the real test isn’t whether Light & Wonder can post a good quarter after deleveraging. It’s whether the new version of the company can keep producing hits—across cabinets, apps, and online casinos—while staying clean on IP in an industry where the line between inspiration and infringement is both blurry and heavily litigated.

The company’s own framing says it plainly: constant innovation is the job. Create content players come back to. Keep the experience at the center. Relentlessly chase both the now and the next.

For investors, Light & Wonder is a focused bet on gaming content. The company has shown it can execute: nine consecutive quarters of double-digit revenue growth is hard to dismiss. The balance sheet went from existential threat to something closer to a competitive weapon. And the three-part structure—Gaming, SciPlay, and iGaming—gives it exposure to both the physical casino floor and the fastest-growing digital channels.

But the risks are real, and they’re not small. The Aristocrat litigation could widen beyond Dragon Train. Competition is intensifying as the Apollo-backed IGT combination ramps up. And at the end of the day, this is a creative business with a manufacturing and distribution wrapper—success still depends on making games people actually want to play, over and over again.

Light & Wonder has already remade itself once in dramatic fashion. The gaming industry has a way of demanding reinvention on a schedule you don’t control. For now, Light & Wonder sits in a rare position: carrying forward legacy brands that helped define modern casino gaming, while trying to prove that its future—cross-platform, digital-first, and content-led—can be even bigger than its past.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music