JB Hi-Fi: Australia's Retail Disruptor

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

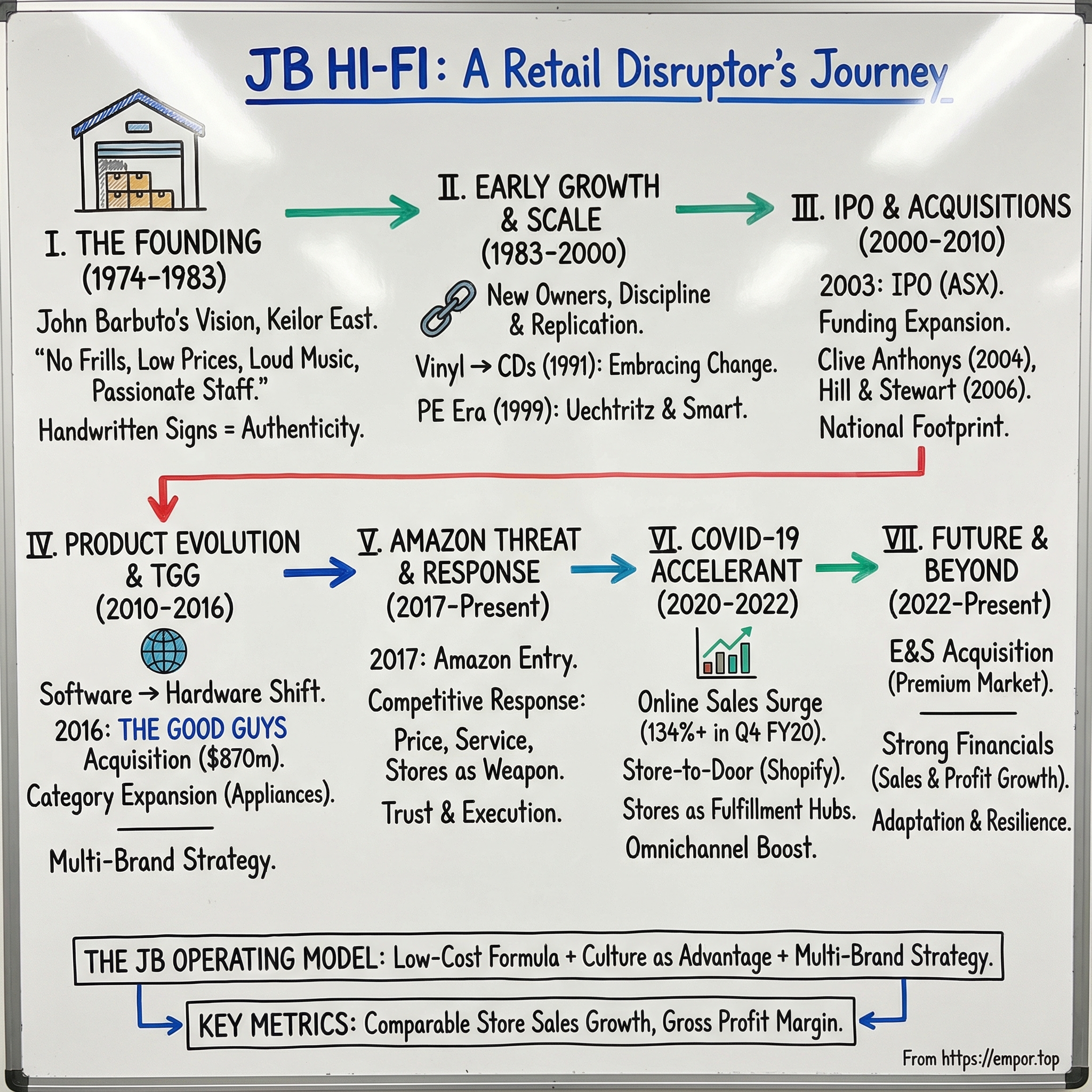

Picture the retail apocalypse that rolled through the US and Europe in the 2010s. Borders. RadioShack. Toys "R" Us. Sears. Household names that went from dominant to gone, leaving behind liquidation banners and empty parking lots. Now add one more ingredient: Amazon announcing it’s coming to your country—the most relentless retailer on earth, pointing straight at your categories, your customers, your margins. Cue the analysts and fund managers writing the obituary in advance.

That was the script for JB Hi-Fi.

Instead, JB Hi-Fi Limited became one of Australia’s defining retail success stories. It’s a consumer electronics retailer, publicly listed on the Australian Securities Exchange, and headquartered in Southbank, Melbourne, Victoria. As of June 2024, the group operated 330 stores across Australia and New Zealand: 205 JB Hi-Fi and JB Hi-Fi Home stores in Australia, 19 JB Hi-Fi stores in New Zealand, plus 106 The Good Guys stores in Australia.

So here’s the question that drives this deep dive: How did a single hi-fi shop in suburban Melbourne become Australia’s most feared retail execution machine—and then survive the Amazon onslaught? Because the answer isn’t just “they sold TVs cheaper.” It’s a lesson in what great retail actually is, and why culture—unfashionable, hard-to-measure culture—can be one of the strongest moats in business.

From a public float valued at just AUD 18.2 million in 2003, JB Hi-Fi’s rise is a masterclass in scale. It’s aggressive store growth. It’s smart acquisitions. It’s an uncompromising discount promise. And it’s reinvention: the company lived through the collapse of the very thing it was built on—physical media—and came out the other side with a business centered on hardware and electronics that now generates over $10 billion in annual revenue.

Along the way we’ll hit a few big themes that show up again and again in the best companies: culture as a competitive advantage, the death of software and the rebirth through hardware, expansion through acquisition, and—most surprisingly—how JB didn’t just “withstand” Amazon in Australia, but learned how to compete in a way that kept it thriving.

What makes JB Hi-Fi so fascinating is the consistency. Retail has spent the last decade getting whiplash from e-commerce, supply chain shocks, and changing consumer behavior. JB’s model has looked almost stubbornly familiar through it all. Walk into a store today and you still get the warehouse vibe, the hand-drawn signs, the staff who actually know the products. It feels simple. But that simplicity hides an operational intensity—relentless execution on price, range, and service—that competitors have found incredibly hard to copy.

II. The Founding: John Barbuto's Warehouse Vision (1974-1983)

To understand JB Hi-Fi, you have to start with John Barbuto—and the quiet rebellion he staged against what “proper” retail looked like in 1974.

Walk into a department store of the era—David Jones, Myer, Grace Brothers—and you’d get the full ceremony: polished floors, uniformed staff, product kept tidy and distant, like it belonged behind glass. The subtext was simple: shopping was formal. The store was in control. You were the visitor.

Barbuto opened JB Hi-Fi in Keilor East, a suburb of Melbourne, selling recorded music and specialist hi-fi equipment. The name was as straightforward as the concept: his initials. And the store he built was the anti-department store.

This first JB Hi-Fi wasn’t about presentation. It was about access and price. Barbuto pioneered a warehouse-style model—bootstrapped, no-frills, product stacked up, music loud, and a clear promise that mattered more than any fancy fit-out: the lowest prices. His philosophy was equally direct: deliver a specialist range of hi-fi and recorded music at Australia’s lowest prices.

In the context of 1970s Australian retail, that was genuinely disruptive. Instead of treating hi-fi like a luxury purchase mediated by gatekeepers, JB treated it like a passion you could walk into, touch, compare, and take home—without the markup that paid for the theater.

And the “bare bones” look wasn’t just an aesthetic choice; it was the business model. Strip out the overhead of premium retail and you can undercut competitors while still making money. Hire enthusiasts—people who actually care about sound—rather than detached counter staff, and you can give customers better advice with less pretense. Even the loud music served a purpose: it was ambiance, yes, but it was also a live demo and a signal that this place was run by people who loved the product.

Out of that same practicality came the detail JB would eventually become famous for: hand-drawn signage. It started as necessity, not branding. Employees drew signs and wrote product reviews in their own words, and decades later some of those signs would go viral online. Commentators have noted that the bespoke, homemade look gives customers the impression JB keeps prices low by not spending on professional printing.

But the signs did more than save money. They turned each shelf into a human recommendation. Long before star ratings and unboxing videos, JB effectively created in-store social proof: real staff, real opinions, right next to the product. A handwritten note that reads like it was scribbled by someone who actually bought the thing carries a kind of trust that glossy marketing can’t manufacture.

What Barbuto built in Keilor East was a template: warehouse energy, aggressive pricing, staff who know the gear, and a sense of authenticity you could feel the second you walked in. It was simple, repeatable, and—crucially—durable.

Then, in 1983, after nearly a decade of building the business, Barbuto made the decision that would set JB on a much faster path. He sold.

III. New Ownership & The Foundation for Scale (1983-2000)

In 1983, Barbuto sold JB Hi-Fi to Richard Bouris, David Rodd, and Peter Caserta. They didn’t buy it to preserve a quirky suburban record-and-hi-fi shop. They bought it because they could see the blueprint.

What Barbuto had built in Keilor East wasn’t a one-off. The warehouse layout, the relentless discounting, the staff who actually knew the gear, the handmade signs—those were systems. And systems can be copied, store after store, without losing the thing that made the first one work.

So that’s what they did. Through the 1980s and into the 1990s, the new owners expanded steadily—first across Melbourne, then into Sydney—building JB Hi-Fi into a chain of ten stores. The trick wasn’t reinvention; it was discipline. Every new location kept the same core formula: no frills, sharp pricing, and a store experience that felt more like a club for enthusiasts than a polished retail showroom.

By 2000, the business was turning over $150 million. But the more important milestone happened earlier, in 1991, when JB Hi-Fi made a decision that could’ve easily alienated its base: it cleared out its vinyl stock and went all-in on CDs—one of the first Australian music retailers to do it.

That wasn’t just a merchandising change. It was a statement about how JB Hi-Fi thought. Vinyl wasn’t some peripheral category; it was part of the company’s identity. Walking away from it meant choosing the customer’s future over the company’s nostalgia. And that choice revealed a DNA that would matter again and again: JB Hi-Fi would protect its operating principles—low costs, low prices, knowledgeable staff—but it would never get sentimental about the product format.

As the decade closed, the business was proven but still largely regional. Then came the next gear change. In 1999, private equity firm Next Capital acquired a controlling stake, setting up JB Hi-Fi for a more aggressive national push—with new capital, and soon, professional leadership built for scale.

By the end of the 1990s, all the ingredients were in place: a repeatable model, a culture that survived expansion, and evidence that the company could pivot fast when the market moved. What JB Hi-Fi needed next was the engine to go national.

IV. The Private Equity Era & Richard Uechtritz's Transformation (2000-2010)

If the 1990s proved JB Hi-Fi’s model could work, July 2000 is when the company found the leadership to scale it. Senior management, backed by private equity, bought the business with a clear goal: take this scrappy, repeatable formula and roll it out across Australia.

To lead that charge, JB brought in Richard Uechtritz. He wasn’t the classic big-chain executive groomed inside a department store. Before JB, he built businesses like Rabbit Photo and Smiths Kodak Express, and spent more than two decades in retail with a reputation as an entrepreneur and turnaround operator. What he brought was a rare mix: the instincts of a founder, paired with the discipline to build a national machine.

He didn’t do it alone. Terry Smart arrived at the same time, ultimately becoming the long-term operational counterweight to Uechtritz’s growth agenda. Smart served as CFO in those early years, while Scott Browning, as Marketing Director, helped lock in the brand language JB still uses today—especially the “handwritten” look and feel that signals authenticity and thrift the moment you walk in.

Over the next decade, the Uechtritz team executed a transformation that reads almost obvious in hindsight, but was anything but at the time: they evolved the product mix. JB Hi-Fi moved beyond specialist hi-fi and leaned harder into computers and consumer electronics. One particularly consequential shift was getting premium hi-fi speakers off the showroom floor and replacing them with computers, including Apple products, PCs, and accessories. The impact on cash flow was immediate, and the business shifted into a faster growth gear—sales climbed, and the store count followed.

This wasn’t JB abandoning what made it JB. It was the opposite: applying the original playbook to a bigger, faster-growing set of categories. Same low-frills environment. Same sharp pricing. Same staff who actually used the gear and could explain it. The products changed; the operating model didn’t.

Then came the catalytic event that made national expansion far easier to finance: the IPO. In October 2003, JB Hi-Fi listed on the Australian Securities Exchange, raising capital that helped fund a rapid rollout of larger stores in high-traffic locations. For early shareholders, the results would be exceptional: the stock went on to deliver returns that massively outpaced the broader market, powered by year-after-year execution on the expansion plan.

With the public-market funding in place, Uechtritz moved quickly to plug geographic gaps through acquisitions. In July 2004, JB bought 70% of the Clive Anthonys chain in Queensland. Those stores were integrated and rebranded as JB Hi-Fi Home, and they brought something strategically important: a broader product range, including whitegoods and cooking appliances.

Next was New Zealand. In December 2006, JB acquired the Hill and Stewart chain for NZ$17.5 million (A$15.3 million). By 2007, JB began opening its own branded stores in the market, and by 2010 it had phased out the Hill and Stewart name entirely.

By the time Uechtritz announced his retirement in 2010, the before-and-after was stark. JB had gone from a regional chain to a publicly listed national retailer with more than 130 stores across Australia and New Zealand.

When he stepped aside, Uechtritz framed it simply: “Ten years is a good innings as a CEO.” He said the company was in great shape, with a strong balance sheet and good growth prospects. Chairman Patrick Elliott echoed the sentiment, praising Uechtritz’s decade of leadership and noting the succession to Terry Smart had been the board’s plan for some time: Smart was “a very talented retail executive,” and the board was “delighted” he would take the role.

It mattered that the handover was clean. It signaled that JB’s biggest achievement in the 2000s wasn’t just store growth—it was building a leadership bench and an operating rhythm strong enough to keep running, even as the person at the top changed.

V. The Leadership Succession & Product Evolution (2010-2016)

Terry Smart took over as CEO in 2010, and his four-year run through to 2014 is best understood as JB Hi-Fi tightening the screws on a model that was already working: keep expanding, keep executing, keep the culture intact. But underneath that steady surface, the company was moving through a change that would end up being existential.

Because the thing JB was famous for—software, physical media, the wall of CDs and DVDs—was dying.

You can see it most clearly in what happened over the following decade. By 2020, most of JB Hi-Fi’s sales had shifted away from software like music CDs, DVDs, and video games, and toward hardware like televisions, mobile phones, and computers. Software, which had been more than a quarter of sales in 2010, had shrunk to a single-digit slice by 2020.

That’s not just a category mix tweak. That’s a company changing its center of gravity.

In the space of ten years, JB Hi-Fi effectively went from being a media retailer that also sold electronics to an electronics retailer that still carried some media. The forces driving that shift weren’t optional—streaming, digital downloads, and rapidly changing consumer behavior were going to happen whether JB liked it or not. The remarkable part is that JB didn’t get caught clinging to the old world. It adapted, and kept growing.

As the mix evolved, the range broadened with it. JB Hi-Fi expanded across computers, tablets, TVs, cameras, hi-fi and speakers, car sound, home theatre, games, recorded music, movies and TV shows, plus whitegoods and small appliances.

So why didn’t the collapse of CDs and DVDs kill JB Hi-Fi the way it crushed so many retail brands? Because JB never let itself become “a CD store” or “a DVD store” in the first place. It positioned itself as the place where you could get entertainment technology, expert advice, and sharp prices. The products could change dramatically—as long as the promise stayed the same.

That distinction sounds subtle, but it’s the whole game. Plenty of retailers anchor their identity to a specific format and then act surprised when the world moves on. JB anchored its identity to a customer outcome: helping people buy the gear they want, for less, with staff who actually know what they’re talking about. When the format shifted, JB shifted its shelves.

By the early 2010s, the store had become an increasingly broad consumer electronics destination—TVs, audio/visual, digital cameras, portable audio, in-car entertainment, gaming consoles and accessories, white goods, and DVD and Blu-ray movies. And in some stores, JB pushed into even more niche categories: CB radios, IP and fixed surveillance camera systems, musical instruments like guitars, electronic keyboards and ukuleles, and even professional DJ equipment.

In 2014, Smart retired and was succeeded by Richard Murray. And with that handoff, JB Hi-Fi was about to enter its next chapter—the one defined by a massive acquisition, and the looming arrival of Amazon in Australia.

VI. The Good Guys Acquisition: Category Expansion (2016)

If JB Hi-Fi’s first decade as a public company was about proving it could scale, September 2016 was about changing what “JB” could be.

On 13 September 2016, JB Hi-Fi announced it would acquire The Good Guys for $870 million. Overnight, the group didn’t just get bigger—it got broader. The deal lifted JB Hi-Fi’s share of the Australian home appliance retail market to 29%, and its share of the consumer electronics retail market to 24%.

Two years later, in August 2018, JB Hi-Fi was ranked as the equal 7th largest consumer electronics and home appliance retailer in the world.

But to understand why this acquisition mattered, you have to understand The Good Guys on its own terms—because it wasn’t some distressed chain being scooped up. It was a family-built powerhouse.

The business began in 1952, when Ian Muir started retailing electrical goods in Essendon, in Melbourne’s north. The first store was called Ian Muir's Radio and Electrical Centre, and the founding philosophy was simple: delight customers and “do good.” Over time, careful small acquisitions helped build a foundation strong enough to expand. In 1998, the brand was renamed The Good Guys—paired with the now-famous “Pay Less Pay Cash” proposition and the iconic TV commercial that helped carry it into the national consciousness. After Ian Muir’s death in 2009, ownership remained with the Muir family.

By the time JB came knocking, The Good Guys had built a dominant position in whitegoods and home appliances—exactly the categories where JB Hi-Fi was comparatively light. Put the two together and you suddenly had one retail group that could credibly cover consumer electronics, entertainment, and the big-ticket “whole home” purchases that happen when people move, renovate, or build.

Importantly, regulators agreed the logic wasn’t about swallowing a direct competitor. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission announced it would not oppose the acquisition, concluding that JB Hi-Fi and The Good Guys generally focused on different product categories and customers. JB Hi-Fi was traditionally about consumer electronics, with stores mostly in shopping centres or CBDs. The Good Guys, by contrast, mostly focused on whitegoods and home appliances, with stores generally located in home centres or similar locations. In other words: different missions, different baskets, different real estate.

That complementarity also showed up in how the sale happened. According to the commentary around the deal, The Good Guys had been running a dual-track process—exploring both a possible IPO and an ASX listing while also pursuing a trade sale—before landing with JB. The transaction closed as a major milestone for the Muir family and The Good Guys management team.

JB Hi-Fi CEO Richard Murray said JB acquired The Good Guys because it was the market leader in the Australian consumer electronics space. But the real payoff wasn’t just the headline of “category expansion.” The Good Guys brought installation capability and deeper appliance expertise, lifting the group’s ability to sell and service larger, more complex purchases. At the group level, JB could apply its scale in logistics and sourcing to drive cost advantages. And crucially, JB didn’t try to mash the two brands together. The dual-brand approach helped avoid cannibalisation, letting each chain keep its identity while benefiting from shared scale behind the scenes.

By November 2016, the acquisition was complete. JB Hi-Fi and The Good Guys were now under the same roof—a new force in Australian retail, set up not just to sell more boxes, but to sell across more of the home. And as it turned out, that breadth was about to matter a lot when the next threat arrived.

VII. The Amazon Threat & Competitive Response (2017-Present)

Amazon finally landed in Australia in December 2017. And it wasn’t arriving into a vacuum. Global online players kept coming—Shein in November 2021, Temu in March 2023—each one reinforcing the same fear: that local retailers were about to get squeezed from every side.

For JB Hi-Fi, the anxiety wasn’t abstract. It was loud, public, and financial. The Australian Financial Review reported that Phil King of Regal jolted the market when he revealed a bet against JB Hi-Fi right as Amazon was preparing its Australian assault. His estimate was brutal: as much as 60 per cent of JB Hi-Fi’s profits could vanish over the next few years, especially if Amazon rolled out Prime locally.

And to be fair, that fear had precedent. In the United States, Amazon’s rise had coincided with the collapse of major electronics retailers. Circuit City disappeared. RadioShack imploded. Even Best Buy had, at points, looked like it might not make it. So when Amazon announced Amazon.com.au, the assumption was simple: Australia would follow the same script, and retailers like JB Hi-Fi and Harvey Norman would wear the damage.

In the early commentary, the message was basically: electronics, fashion, sporting goods, toys—these categories are about to get hit first and hardest.

Then Amazon launched, and the first surprise showed up immediately: price.

Yes, Amazon.com.au was competitive on plenty of items. But when analysts and journalists started doing the obvious thing—spot-checking popular products—some of the results were not what anyone expected. In one widely reported example, an iPhone 7 Plus was listed at A$1,345 on Amazon versus A$1,199 at JB Hi-Fi. More broadly, there were complaints about limited range and prices that weren’t consistently sharper than the incumbents.

The market reaction flipped. Retail stocks that had been sold off ahead of launch—JB Hi-Fi, Harvey Norman, Myer, Super Retail Group—bounced as consensus started forming that Amazon might not have the immediate impact so many expected. And that bounce came even as Amazon talked up its early momentum, saying first-day orders were higher than any prior Amazon launch day.

The next surprise came when analysts kept checking. One set of research found Amazon beat JB Hi-Fi on price in only three of twelve products surveyed, and was more expensive overall. Nearly a year in, Morgan Stanley analysts argued Amazon Australia was still pricier than local retailers like JB Hi-Fi for most branded tech goods.

So what happened? JB didn’t “survive Amazon” by discovering some secret trick in 2018. It survived because it had spent decades building advantages that an online-only entrant couldn’t simply copy and paste.

JB Hi-Fi’s response wasn’t panic. It was execution. Compete hard on price, because JB’s buying power and low-cost model gave it room to move. Win on service, because stores staffed by product nerds can do something a checkout page can’t. And lean into the physical network as a weapon: immediate availability, fast pickup, and the ability to turn stores into fulfillment points through click-and-collect and delivery options.

Underneath it all was something harder to quantify but obvious to customers: trust. In consumer electronics and appliances—categories where people want the right product, today, with someone accountable if it goes wrong—the JB Hi-Fi and The Good Guys brands carried weight.

Amazon, of course, still grew. Amazon Australia became the company’s fastest-growing marketplace; it launched with thousands of third-party sellers and added more quickly. Revenue rose sharply from 2017 to 2018.

But the apocalypse scenario never arrived. Amazon became a major force in Australian e-commerce, yes—but the catastrophic impact predicted for JB Hi-Fi didn’t materialize. Instead, JB kept thriving, and in the process proved a point that gets lost in the “everything goes online” narrative: when physical retail is run with ruthless efficiency, strong culture, and a real omnichannel playbook, it can compete—credibly—even with the most formidable online retailer in the world.

VIII. COVID-19: The Accelerant (2020-2022)

When COVID-19 hit, JB Hi-Fi Group’s operations were heavily affected by the pandemic and the government actions that came with it. The company said it stayed committed to supporting efforts to limit the spread of the virus. But from a business standpoint, the bigger story was this: the pandemic should have been a disaster for a retailer built around hundreds of physical stores.

Instead, it poured gasoline on the model.

Across JB Hi-Fi Australia and The Good Guys, performance stayed strong. Sales growth was elevated, driven by homemaker and free-standing stores and, most importantly, a sharp acceleration in online as both businesses continued providing retail and commercial services.

The numbers told the same story in different ways. Over twelve months, online sales rose by nearly 50 per cent. In the fourth quarter of FY20, JB Hi-Fi’s online sales jumped 134 per cent. Between January 1 and May 31, 2020, JB Hi-Fi Australia reported a 20 per cent rise in sales, while The Good Guys reported a 23.5 per cent increase over the same period.

The “why” was painfully obvious in real time. Australians were suddenly working, learning, and entertaining themselves from home. That meant an urgent, nationwide shopping list: computers, monitors, webcams, office equipment. Laptops and tablets for remote schooling. Bigger TVs, gaming consoles, and home entertainment for families stuck inside. JB didn’t need to invent demand—it just needed to meet it.

Of course, meeting it wasn’t simple. In 2020, JB Hi-Fi faced major disruption, including temporary store closures in Victoria under stage 4 restrictions. But those closures also accelerated the shift that had been building for years. For the full year, online sales rose 48.8 per cent to $597.5 million, helping offset lost in-store trade and capturing the surge in demand for home electronics.

Then came the operational scramble: how do you keep delivering at speed when customers can’t—or won’t—come to you?

JB leaned into its digital stack. Using real-time APIs with the Shopify platform, the business built and launched a 90-minute delivery offering called Store-to-Door. Early on, while stores were closed to the public, it was literally store team members doing deliveries. Demand was strong enough that the service became ongoing even after stores reopened, shifting to Uber drivers and their vehicles to deliver orders within 90 minutes of purchase.

That convenience hid a hard truth: with more than 80 per cent of JB Hi-Fi’s online fulfillment handled by physical stores, the whole system was complex. Stores weren’t just shops anymore—they were mini-warehouses, dispatch points, and customer service hubs, all at once.

Behind the scenes, JB also moved to increase capacity in its supply chain. During the pandemic, it deployed Microsoft Dynamics 365 Supply Chain Management to transform warehouse operations and handle the surge in volume. With Microsoft Fast Track’s assistance, the implementation was completed in roughly four months—an unusually fast timeline for a project of that scale, and a sign of how urgently the business was executing.

JB also shared some of the upside. In June, the group paid a $1,000 bonus to full-time, customer-facing staff. The market liked what it saw too: after strong results, JB Hi-Fi’s share price rose by nearly five per cent in Monday trading. The company also announced its 2019–20 dividend would rise 33 per cent to $1.89 per share.

The lasting impact wasn’t just a hot streak of sales. The pandemic permanently raised JB Hi-Fi’s online and omnichannel ceiling. What might have taken years of incremental change was compressed into months—because suddenly, it wasn’t an initiative. It was the only way to operate.

IX. The Omnichannel Evolution & E&S Acquisition (2022-Present)

Coming out of the pandemic, JB Hi-Fi leaned into a simple idea that a lot of retailers talk about but few execute well: don’t treat online and stores as separate businesses. Let customers do what they naturally want to do—research on their phone, buy when they’re ready, and pick up fast from a local store. Across more than 300 locations in Australia and New Zealand, that “research online, collect in-store” loop turned JB’s footprint into an advantage, not a liability. Stores weren’t just places to browse anymore; they became essential hubs for fulfillment and service.

To make that work, JB invested heavily in its digital sales platform so it could go toe-to-toe with global online giants. The direct-to-consumer channel became a core pillar of the modern JB model—an engine for growth rather than a defensive side project.

A big piece of that engine has been an enduring partnership with Shopify. With Shopify, JB was able to move quickly and innovate at scale without disrupting day-to-day trade. Over time, the payoff showed up in the numbers: online revenue grew to more than $1 billion annually, up from about $200 million. Online went from roughly 5% of sales to about 15%. The story here isn’t the exact percentages—it’s the direction. JB turned e-commerce from “nice to have” into a material part of the business, while still using stores as the delivery mechanism.

Then, in September 2024, JB made its next strategic leap: upmarket.

That month, JB Hi-Fi acquired a 75% stake in premium kitchen and bathroom retailer E&S Trading for $47.8 million. ChannelNews reported JB had been looking to enter this segment for years. E&S Trading generated annual revenue of $230 million and earnings of $7 million, and it came with a very specific kind of retail credibility: founded in 1962 by Bob Sinclair and his two brothers, and built around relationships and expertise in the high-end appliance market.

JB’s CEO Terry Smart framed the fit clearly. “e&s’ established reputation as an industry leader in the high-end appliance market will complement JB Hi-Fi Group’s existing businesses and bring a new premium offering to the JB Hi-Fi Group,” he said. Smart described e&s as a business built on leading global brands, great prices, expert advice, and exceptional customer service—and, importantly, one that could reach both a new premium customer base and the commercial construction market.

The structure mattered as much as the purchase. E&S already had a proven formula in Victoria and the ACT, plus relationships with top premium appliance brands. That gave JB a model it could potentially scale into other states. But the key was separation: e&s would be run as its own entity, distinct from both JB Hi-Fi and The Good Guys.

And it really is a different customer. The E&S acquisition exposed JB to buyers who’ll spend $50,000 on a stove or $60,000 on a refrigerator—shoppers who would likely never walk into a traditional JB Hi-Fi or Good Guys store. It also opened the door to the commercial construction channel, where developers might purchase hundreds of appliances for a single apartment project.

Not long after, JB Hi-Fi Limited reported its half-year results for HY25, with sales up 9.8% to $5.67 billion—growth that was driven in part by the acquisition of the 75% stake in E. & S. Trading Co. Earnings before interest and tax increased 8.6% to $419.9 million, and net profit after tax rose 8.0% to $285.4 million.

Across the group, the momentum was broad. In Australia, sales increased 7.2% to $3.88 billion, helped by strong demand for technology and consumer electronics. Online sales grew 16.4% to $682.7 million. New Zealand sales rose 20.0% to NZ$202.5 million, with online sales up 58.4%. The Good Guys reported sales up 9.2% to $1.52 billion.

X. Playbook: The JB Hi-Fi Operating Model

JB Hi-Fi’s edge isn’t one magic trick. It’s a set of advantages that lock together—each one making the others stronger. If you pull them apart, they look simple. Put them together, and you get a retail machine that’s been remarkably hard to disrupt.

The Low-Cost Formula

The foundation is a relentlessly low-cost operating model. JB’s store formats are built to keep overhead down. The warehouse look isn’t just a vibe—it’s capital efficiency. Less spent on fit-out means more room to compete on price.

That discipline extends to how the stores run day to day. The labour model is tight, but it’s not “thin.” Staff are expected to be productive, and they’re empowered to make decisions that move product and solve customer problems quickly.

Then there’s buying power. National purchasing with major global brands creates real scale advantages, and JB leans heavily on vendor-funded promotions and co-marketing, which helps keep marketing costs down while still staying loud in the market when it matters.

Put that together and you get the core promise JB has always been built on: sharp pricing, consistently, without needing to compromise on range. And because it pairs well-branded physical stores with a serious online platform, JB can win both kinds of purchases—the impulse buy when you’re already in-store, and the researched purchase after weeks of comparing options online.

Culture as Competitive Advantage

The hand-drawn signs and employee reviews aren’t just quirky decoration. They’re the visible output of a culture that pushes expertise to the front line. Employees draw signs by hand. They write product reviews. And the message to the customer is: a real person who knows this stuff is standing behind this recommendation.

That “geeks selling to geeks” model is more than a slogan. It’s a sales engine. When a staff member can explain the tradeoffs between TV technologies, or steer you toward the right gaming headset for how you actually play, it creates trust—and trust converts. That’s something pure-play e-commerce struggles to replicate, especially in categories where the wrong choice is expensive and annoying.

Multi-Brand Strategy

JB’s growth strategy also relies on staying multi-brand, not one-size-fits-all. The group deliberately uses distinct brands to cover the market without forcing them to compete with each other.

Today, that means three different storefronts for three different missions: JB Hi-Fi for technology and entertainment, The Good Guys for home appliances, and e&s for premium kitchen and bathroom. Each keeps its own identity and customer relationship, while the group shares the unsexy but powerful stuff behind the scenes—sourcing scale, logistics capability, and corporate services.

That combination—low costs, real expertise, and smart brand coverage—is the JB Hi-Fi operating model. It’s not flashy. It’s just exceptionally well executed.

XI. Myths vs. Reality: What the Market Gets Wrong

Myth: JB Hi-Fi is a victim of structural decline in retail

Reality: For two decades, JB Hi-Fi has been the counterexample to the “retail is dead” narrative. It kept growing revenue, earnings, and market share through cycles that were supposed to wipe out businesses like it. And it did it the same way, over and over: by changing what it sells without changing what it is. Vinyl gave way to CDs. CDs gave way to consumer electronics. Stores became fulfillment nodes. The channel shifted, the categories shifted, but the engine stayed the same—low costs, sharp prices, and staff who can actually sell the product.

Myth: Amazon will eventually destroy JB Hi-Fi's business model

Reality: Amazon has been in Australia since 2017, and the “eventual destruction” hasn’t arrived. JB Hi-Fi has kept thriving because it doesn’t fight Amazon with slogans—it fights with execution. It matches hard on price where it matters, uses its store network as an advantage through an integrated omnichannel model, and differentiates with service in categories where people still want reassurance and accountability. Those are advantages you don’t get by shipping faster or optimizing a checkout page.

Myth: The COVID boom was unsustainable

Reality: The spike of 2020 and 2021 obviously wasn’t going to repeat forever. But the more important story is what stayed behind after the surge faded. JB Hi-Fi’s sales base stabilized at a structurally higher level than pre-pandemic, and the company didn’t just ride the wave—it used it to permanently improve its digital capabilities. In other words, COVID wasn’t only a temporary demand shock. It was an accelerant that pushed JB further into the omnichannel future it was already building.

XII. Bull Case vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

At its best, JB Hi-Fi looks like one of those rare retailers with multiple “structural” edges stacked on top of each other—advantages that don’t disappear just because the cycle turns ugly.

In Hamilton Helmer’s language, you can see real “power” here. There’s Counter-Positioning in the way JB blends physical stores with a serious online business. It’s not just “we have stores and a website.” It’s that the stores are part of the online system—pickup points, fulfillment nodes, places customers can get answers and walk out with the product today. That’s hard for a pure-play e-commerce player to replicate without changing their economics.

Then there’s Scale Economies. JB’s national buying power and long-standing vendor relationships let it compete on price in a way smaller chains and independents simply can’t match for long. And there’s Brand: JB Hi-Fi and The Good Guys have become default destinations for big, high-stakes purchases where customers want confidence and accountability, not just a checkout button.

If you look at it through Porter’s Five Forces, JB has built defenses across the board. Buyer power is blunted by range and availability at sharp prices. Supplier power is kept in check with scale, relationships, and options across brands. Rivalry has eased in some ways thanks to consolidation and shakeouts in the category—Dick Smith’s collapse being the obvious example, and JB’s acquisition of The Good Guys being the biggest strategic one. The threat of substitutes has been managed by broadening the mix into adjacent categories and, more recently, moving into premium. And while new entrants can always appear online, building a true national footprint—stores, distribution, service capability, and brand trust—is still a high bar.

On that point, E&S matters. It gives JB access to a higher-end customer and a commercial construction channel that the core JB Hi-Fi format was never designed to reach. Layer on continued online growth—evidence the omnichannel model is resonating—and the bull case is that JB keeps compounding: benefiting from population growth, ongoing housing turnover, and the steady churn of electronics and appliances that need replacing and upgrading.

The Bear Case

The bear case is simpler: retail is unforgiving, and the middle gets squeezed.

As Jarden analyst Ben Gilbert put it: “Retailers need scale or niche differentiation to survive. The market is bifurcating, with those caught in between – Kogan, Big W, Myer and JB Hi-Fi accessories – facing the greatest risk as competition squeezes from both ends.”

One risk is that e-commerce competition keeps intensifying, and JB’s store-led model becomes more of a cost burden than an advantage—especially if online execution doesn’t stay world-class. In that world, margins get pressured, price-matching gets more expensive, and market share gets harder to defend.

Another risk is cyclical. If inflation and cost-of-living pressure keep consumers cautious, discretionary categories can soften quickly. And electronics is particularly exposed: people can delay upgrades, stretch replacement cycles, and make do.

Then there’s Amazon, which keeps investing in Australian logistics and fulfillment. Prime creates a kind of lock-in that JB can’t replicate directly. At the low end, Chinese entrants like Temu and Shein continue to gain attention and share, which can drag expectations on price across the whole market—even for retailers that don’t compete directly in every SKU.

Finally, some of the category fundamentals may be shifting. As devices become more durable and incremental upgrades feel less compelling, replacement cycles can extend. If that happens at the same time as economic uncertainty rises, JB’s core engine—high-volume sales of consumer electronics and entertainment products—could face a tougher demand environment than the company has been used to managing.

XIII. Key Performance Indicators: What Matters Most

If you want the quickest read on whether JB Hi-Fi is still doing the JB Hi-Fi thing—winning customers, moving volume, and staying sharp on price—two metrics matter more than almost anything else:

1. Comparable Store Sales Growth (Same-Store Sales)

This is the reality check. It strips out the sugar hit from opening new stores and asks a simpler question: are the existing stores selling more than they did last year?

JB Hi-Fi has historically been able to post positive comparable sales growth even in tougher periods. That usually points to some combination of market share gains, strong execution, and expanding into the right categories at the right time. Keep seeing steady positive comps, and it’s a sign the core engine is healthy. Sustained negative comps, on the other hand, are the early warning signal—either demand is softening, competitors are taking share, or the offer isn’t landing like it used to.

2. Gross Profit Margin

JB lives in a low-margin, high-volume world. That means gross margin isn’t just an accounting line—it’s the oxygen level of the business. Small moves here can have an outsized effect on earnings.

Gross margin captures a lot of what makes JB hard to compete with: how effectively it buys, how well it manages promotions, what mix of products customers are buying, and how much pricing pressure it’s absorbing. If gross margin compresses, it typically means the fight is getting uglier—more discounting, more competition, or a mix shift toward lower-margin categories. If it holds up or expands, it’s usually a sign JB is managing the mix well and maintaining real pricing power through scale and execution.

Together, these two tell you what you really need to know: is demand holding up, and is JB still making enough on each dollar of sales to turn volume into profit?

XIV. Regulatory and Legal Considerations

Scale doesn’t just bring buying power and brand reach. It also brings scrutiny.

In December 2023, a class action lawsuit was lodged against JB Hi-Fi. The allegation: the retailer sold extended warranties that were worthless or of little value, because they “essentially offer Australian consumers the same thing as what they already get for free under the Australian Consumer Law.”

Even if a case like this is manageable financially, it shines a bright light on a sensitive part of the electronics retail model. Extended warranties are typically a high-margin add-on. If regulators or courts tighten the rules or reshape how these products can be sold, it can pressure profitability—especially for retailers operating at JB’s scale.

The scrutiny hasn’t been limited to the JB brand. The Good Guys has also faced ACCC proceedings, with a resolution announced in 2025. Taken together, these moments are a reminder that in a consumer-protection-heavy environment, execution isn’t only about price and service—it’s also about staying on the right side of what you can promise, how you sell it, and how it’s perceived.

XV. Conclusion: The JB Hi-Fi Model

JB Hi-Fi’s five-decade run—from a single hi-fi shop in suburban Melbourne to one of the world’s largest consumer electronics retailers—doesn’t just make for a great retail story. It offers a blueprint. Not because JB discovered one magic trick, but because it stacked a set of reinforcing advantages: culture, cost discipline, operational execution, and strategic clarity.

JB lived through the death of vinyl, then CDs, then DVDs—and then the arrival of Amazon. Any one of those shifts could have been fatal. JB kept going because its identity was never really about the format on the shelf. It was about the promise: knowledgeable staff, sharp pricing, and an authentic, no-theatre environment customers could trust.

And remarkably, it stayed consistent. It defended its sales base, protected its ultra-low cost structure, and kept the slightly edgy brand personality that Scott Browning helped cement. As The Australian noted, the continuity of key executives—and the fact that CEO successions were internal, with long handovers between people who’d worked together for years—was a major reason JB Hi-Fi’s strategy stayed so steady.

The results show up in the business fundamentals. Over the last five years, returns on capital rose sharply, and the company grew the amount of capital employed too—suggesting JB wasn’t just getting more efficient, it was also finding places to reinvest at attractive rates. That combination—high and rising returns, plus the ability to keep reinvesting—tends to be what separates compounding machines from one-cycle winners. Over that same period, shareholders were rewarded as the stock returned 259%, a sign that the market noticed.

Looking ahead, retail will keep changing. AI, shifting consumer habits, and new entrants will create fresh threats and opportunities. JB’s hand-drawn signs might someday be replaced with digital displays, and the categories on the floor will keep rotating. But the core model—expertise, value, and authenticity at scale—has already proven it can survive multiple “end of retail” moments.

What started as John Barbuto’s rebellion against department-store formality in 1974 became one of the most successful retail operations in the Southern Hemisphere. The takeaway is simple: in retail, as in life, the fundamentals matter more than the format.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music