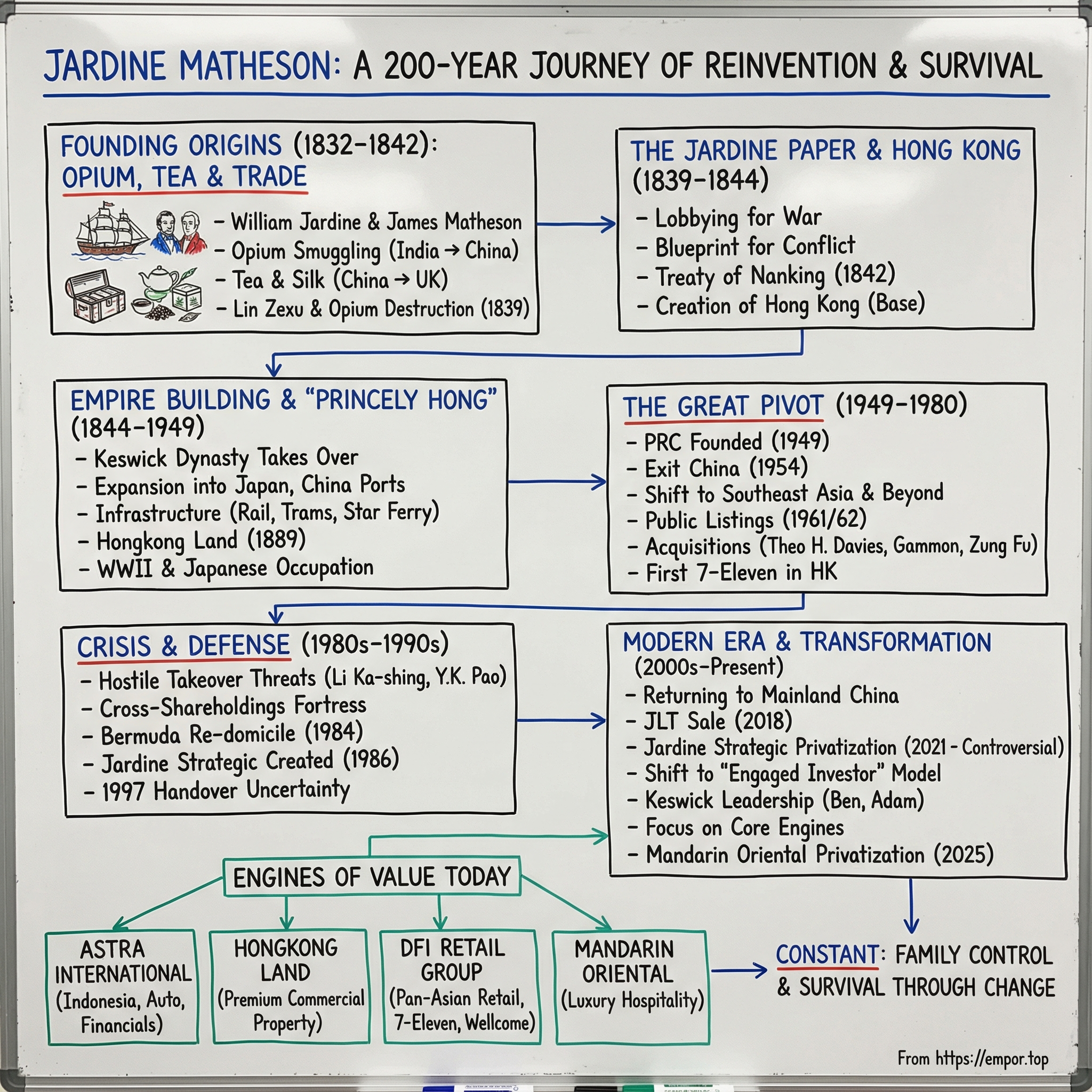

Jardine Matheson: The Hong That Built Hong Kong

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: September 1839. A Scottish merchant named William Jardine walks into the British Foreign Office on Downing Street, not to plead for compensation, but to pitch a war.

In his leather satchel isn’t just a bundle of angry letters about seized cargo. It’s something far more audacious: a playbook. Maps of the Chinese coastline. Notes on naval positioning. Ideas for troop deployments. A set of political demands to force on the Qing government. And, almost as an aside, a suggestion for where Britain should plant its flag if it needed a permanent base near Guangzhou.

His pick was a small, rocky island with a deep, protected harbor.

Hong Kong.

That moment is the hook for everything that follows. This is the story of a company so influential it helped steer British policy into conflict, and so consequential that the world it helped create—Hong Kong as a global trading and financial hub—still shapes Asia’s economy today. It’s also a story with a long shadow: empire and colonialism, moral ambiguity, and a relentless ability to reinvent.

Today Jardine Matheson Holdings Limited is a Hong Kong–based, Bermuda–domiciled, British-founded multinational conglomerate. It has a primary listing on the London Stock Exchange and secondary listings on the Singapore Exchange and Bermuda Stock Exchange. As of December 2025, its Singapore-listed shares trade around US$68.6, for a market capitalization of roughly US$20.2 billion. In 2024, the group reported US$35.8 billion in revenue.

And what does it actually own? A slice of modern Asia. Jardine’s major holdings include Hongkong Land, DFI Retail Group, Mandarin Oriental Hotel Group, Jardine Motors, Jardine Pacific, Jardine Cycle & Carriage, and Astra International. So you’ll find it in the glass-and-steel skyline of Central, in 7-Eleven stores across the region, in luxury hotels, and in the industrial guts of Southeast Asia—from dealerships to heavy equipment and natural resources.

Underneath all that sprawl is the question that makes Jardine Matheson worth a three-hour episode: how does a company born in the chaos of 19th-century China trade—built in part on opium—survive for nearly two centuries through wars, revolutions, the end of empire, the 1997 handover, and modern capital-market combat… while staying under the control of one family?

That family is the Keswicks—descendants of co-founder William Jardine’s older sister—who still control the group today with a roughly 33% stake, now in its fifth generation.

We’re going to trace the arc from Canton’s opium-and-tea economy to a very modern boardroom fight: the controversial 2021 privatization of Jardine Strategic. Along the way we’ll see a new generation try to reshape what “Jardines” even is. Ben Keswick has described the shift plainly: “We have been on an ongoing transition away from our historical owner-operator model, towards becoming an engaged investor.”

Empire and colonialism. Reinvention as a survival strategy. Dynasty governance. And the ever-present reality of geopolitical risk. The themes that defined Jardine at the beginning are, in a different form, the same themes that define it now.

II. Founding Origins: Opium, Tea, and the Birth of a Trading Empire (1832–1842)

To understand Jardine Matheson, you first have to understand the weird, lopsided economics of early 19th-century trade with China.

Britain couldn’t get enough Chinese tea. But China didn’t want what Britain was selling. Chinese workshops produced the finest manufactured goods in the world, and Western exports barely moved the needle. So the trade balanced the old-fashioned way: with silver. By the 1830s, that silver drain was becoming a national problem in London.

Merchants found an answer that worked commercially and wreaked havoc socially: opium.

William Jardine was built for that era. Born on February 24, 1784, near Lochmaben in Dumfriesshire, he didn’t start as a pirate-capitalist archetype. He trained as a physician, earning a diploma from the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh in 1802, and sailed as a surgeon’s mate on East India Company ships. Then in 1817, he walked away from medicine for trade. By the 1820s, he was in Canton, and from 1820 to 1839 he became a fixture of the China coast. His early success as a commercial agent for opium merchants in India got him admitted as a partner in Magniac & Co. in 1825. By 1826, he was effectively running Magniac’s Canton operation.

James Matheson arrived by a different route, but the destination was the same. Opium was where the margins were. Matheson joined Jardine, and in 1832 Magniac & Co. was reconstituted as Jardine, Matheson & Co.

On July 1, 1832, the partnership formally began. In Chinese, the firm took the name “Ewo,” pronounced “Yee-Wo,” meaning “Happy Harmony.” It wasn’t a random bit of branding. “Ewo” had belonged to a former hong run by the famous Chinese merchant Howqua, and it carried a reputation that was valuable in a world where trust was currency.

The business itself was broader than people tend to remember, even if one product powered the whole engine. Jardine Matheson smuggled opium into China from Malwa in India. It traded spices and sugar with the Philippines. It exported Chinese tea and silk to England. It financed trade, insured cargo, rented out warehouse space and dock facilities, and acted as a general merchant across whatever lines could turn a profit.

But “smuggled” is the key word. Opium was banned. Demand wasn’t. And that gap—between what the Qing government outlawed and what millions of people would still buy—created a market so lucrative it effectively funded the firm’s expansion into everything else. Jardine Matheson built a system to make the trade work: fast ships, coastal receiving stations, and logistics designed to outrun enforcement.

William Jardine’s reputation matched the model. Among the Chinese he picked up a nickname: the “Iron-Headed Old Rat,” a nod to how hard and unyielding he could be in a negotiation. One story says a mandarin once struck him on the head with a cudgel, and Jardine didn’t even acknowledge it—just kept talking business.

Inside the firm, the culture was just as distinctive: insular, loyal, and intensely Scottish. Jardines recruited almost entirely from Dumfriesshire, the same small county that had produced the founders. That tight social web would matter later, because it created a pipeline of “their people”—and it set the stage for the Keswicks, also from Dumfriesshire, to marry into the enterprise and eventually come to dominate it.

By the late 1830s, Jardine Matheson had become the biggest British trading house in East Asia, known as the “Princely Hong.” But the very trade that made it so powerful was also turning into a political crisis. Opium was draining China’s silver and tearing through its society. The Daoguang Emperor had had enough. He appointed a new commissioner with extraordinary powers and a clear mandate: shut the trade down.

His name was Lin Zexu.

And Jardine Matheson was about to collide with him in a way that would reshape the region—because the firm wasn’t just participating in history now. It was about to start steering it.

III. The Jardine Paper: Lobbying for War and the Creation of Hong Kong (1839–1844)

Commissioner Lin Zexu arrived in Canton in March 1839 with an unusually blunt mandate: end the opium trade, whatever it took.

He moved fast. Lin surrounded the foreign factories in Canton, effectively trapping the foreign merchant community, and demanded that all opium stocks be surrendered. Under intense pressure, the British Superintendent of Trade, Charles Elliot, ordered the merchants to comply.

Then Lin did something designed to make a point to the world. After seizing roughly 20,000 cases of opium from British traders, he had it destroyed publicly. For three weeks, workers mixed the drug with salt and lime and flushed it into the sea. It was a moral spectacle and an economic shock—an enormous fortune, deliberately erased.

William Jardine didn’t mourn. He mobilized.

That September, he was in London, pressing Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston not for compensation alone, but for a forceful response. Jardine came with something more potent than outrage: a plan. He laid out what to demand from China, which ports to open, how much compensation to require, and even what kind of force would be needed to get it. He supplied maps and strategy. This was the document that became known as the Jardine Paper.

The audacity is hard to overstate. A private merchant wasn’t merely lobbying the British Empire—he was, in effect, drafting its war aims. In the Jardine Paper, he pushed for full compensation for the confiscated opium, a workable commercial treaty, and the opening of additional ports for trade, including places like Fuzhou, Ningbo, and Shanghai. And he added one more suggestion that would echo for centuries: if Britain needed to occupy an island or harbor near Guangzhou, Hong Kong was ideal, with a deep, sheltered anchorage.

Jardine wasn’t just arguing for war. He was handing over a blueprint for how to win it.

By June 1840, a fleet of 16 Royal Navy warships and British merchantmen—many of those merchant vessels leased from Jardine Matheson—arrived off the China coast. The First Opium War was underway.

It was brutally one-sided. British steam-powered ships and modern artillery met defenses that were outmatched, and within two years the Qing government was forced to negotiate.

The result was the Treaty of Nanking in 1842: five ports opened to British trade, indemnities paid, and—most fatefully—Hong Kong ceded to Britain. The chain of events had begun with the seizure of opium in Canton and ran straight through Downing Street, where Jardine had pushed for action that made the surrender of Hong Kong not just possible, but likely.

What’s striking is how enduring the memory has been. While these events are absent from Jardine Matheson’s history page on its website, they still resonate in Chinese society. “It is never far from the front of public memory in China today.”

Jardines moved quickly to turn the new colony into an operating base. In June 1841, even before the war was officially over, the first land lots were sold in Hong Kong. At James Matheson’s instigation, Jardines bought three plots at East Point—about 57,150 square feet—for 565 pounds. In 1844, Jardine Matheson & Company became the first trading firm to buy land in Hong Kong and relocate its head office there.

William Jardine himself didn’t live long enough to see what that foothold would become. He served as MP for Ashburton in Devon from 1841 to 1843, and died on 27 February 1843, just days after his 59th birthday—one of the richest and most influential men in Britain, leaving his fortune to siblings and nephews.

But the thing he helped set in motion—the Princely Hong, and the city it helped create—was only getting started.

IV. Empire Building: The "Princely Hong" and the Keswick Dynasty (1844–1949)

With William Jardine dead and James Matheson preparing to retire—back to Scotland, to the Isle of Lewis estate he’d bought with opium profits—the firm faced a problem that hits every founder-led empire eventually: succession.

Jardines’ answer wasn’t a professional CEO. It was marriage, and the tight-knit Scottish networks of Dumfriesshire that had always served as the firm’s informal talent pipeline.

Thomas Keswick, also from Dumfriesshire, married Jardine’s niece and was brought into the business. Their son, William Keswick, would become the hinge figure in the company’s next era. In 1859, he established a Jardine Matheson office in Yokohama, Japan—an early, aggressive move into a country just beginning to open to Western trade. Over time, William rose into top management, and the Keswicks’ influence grew until they largely displaced the Matheson side of the house.

This shift didn’t happen with a single board vote. It was gradual—then, suddenly, it was the new reality. William Keswick served as managing partner, or taipan, from 1874 to 1886. When he left Hong Kong in 1886 to join Matheson & Co. in London as a senior director, the center of gravity had already moved. From that point on, “Jardine Matheson” increasingly meant “Keswick.”

Strategically, the firm was changing just as dramatically. In 1870 it withdrew from the opium trade and pushed hard into other lines—especially shipping and property. Part of that was necessity. Opium’s economics were shifting, and the moral and political pressure wasn’t going away. But it was also a sign of something Jardines would get very good at: treating reinvention not as a rebrand, but as survival.

The expansion across Asia was relentless. Jardines built out trading offices in major Chinese ports and backed new enterprises ranging from brewing to cotton milling, while still moving huge volumes of tea and silk. It introduced steamboats to China and, in 1876, constructed what’s often cited as China’s first railroad, linking Shanghai with Jardine Matheson’s docks downriver at Woosung.

Japan was the other big bet. Jardine Matheson had become the first foreign trading house to establish a base there in 1859, with offices in Yokohama, Kobe, and Nagasaki. The timing was impeccable: Japan was opening, and Jardines was already on the ground.

Meanwhile, back in Hong Kong, the firm wasn’t just doing business in the colony—it was building the colony. Jardines helped establish Hong Kong’s tram system, which began as an electric tramway in 1904 and still runs today. In 1898, the Star Ferry Company—operator of the now-iconic route between Hong Kong Island and Kowloon—was bought by the Jardine- and Chater-controlled Hongkong and Kowloon Wharf and Godown Company Limited.

The property empire became formal corporate structure. In 1886 came The Hongkong and Kowloon Wharf and Godown Company Limited. In 1889 came The Hongkong Land Investment and Agency Company Limited, founded by James Johnstone Keswick together with the developer Sir Paul Chater—an alliance that would help shape Central into the financial district we recognize now.

By the early 20th century, Jardine Matheson had become so embedded in Hong Kong’s power structure that its taipan sat on the colony’s Executive Council as one of the “unofficial members” representing the business community—alongside the head of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation. Within Hong Kong it was often just called “the Firm” or the “Muckle House,” using the Scots word for “great.”

In 1906, Jardine, Matheson and Co. became a limited company. The diversification continued. In Shanghai, EWO Cotton Spinning and Weaving Co. had been founded in 1895—the first foreign-owned cotton mill in China. Two more mills followed, and in 1921 the three were combined as Ewo Cotton Mills, Ltd.

Then came World War II, and it tore through everything the firm had built on the China coast.

Jardines’ compradores were scattered. Its factories were looted. About 168,000 spindles were stripped from its textile mills. As Japan expanded across China, major ports were occupied, including Shanghai and Canton. Tony Keswick managed the company’s affairs in Shanghai until 1941, when he moved to Hong Kong after being shot by a Japanese national during a municipal election meeting—an incident that captured, in miniature, how violent the era had become.

Tony, a grandson of William Keswick, was one of the two men who carried the dynasty forward inside Jardines. He had gone to the Far East in 1936, and ran the Shanghai office until 1941, when he was shot in the arm. His brother John took over in Shanghai but later had to escape to Sri Lanka when the Japanese seized the city.

During the war, Tony Keswick served in British Intelligence as a Brigadier, heading the China branch of the Special Operations Executive. In Jardines’ world, taipans didn’t just negotiate with governments. Sometimes they worked for them.

The firm survived the war. But the biggest shock to its China-centered model was still ahead.

The Communist revolution was coming.

V. The Pivot: From China to Southeast Asia (1949–1980)

When Mao Zedong proclaimed the People’s Republic of China in October 1949, the Keswicks faced an existential question: could Jardine Matheson survive without the country that had made it?

After the war, John Keswick went back to Shanghai to rebuild—reopening the office, re-stitching trading links, trying to get the old machinery of the “Firm” moving again. But history wasn’t offering a reset. After the Communist takeover, Jardine shifted its head office to Hong Kong in 1949 and tried, at first, to work with the new regime.

It didn’t last. Conditions deteriorated, and by 1954 the company’s operations were shut as its interests were effectively nationalised. Jardines took a US$20 million loss and, more importantly, absorbed a brutal lesson: the mainland wasn’t just temporarily closed. The old model was gone.

That forced a strategic rewrite from the ground up. Everything Jardine had built across Shanghai, Canton, and the treaty ports—mills, wharves, offices, the entire China-centered operating system—was suddenly off limits. But they still had Hong Kong. And they still had capital, relationships, and a culture that had been trained for adaptation.

One of the key moves in the rebuild was to tap public markets. The company listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in 1961, creating a public record of the group’s financial position—and a platform to raise fresh capital. Around the same time, Jardine became publicly traded in 1962 and used additional shareholder funds to buy controlling interests in the Indo-China Steam Navigation Company and Henry Waugh Ltd., and to establish the Australia-based Dominion Far East Line shipping company.

The shift into Southeast Asia had already begun in 1954 with an investment in Henry Waugh and Co. But the real transformation arrived in the 1970s, when Jardines went from “trading house rebuilding after a loss” to “conglomerate on the hunt.”

In 1973, the Group doubled its net worth with two major acquisitions: Theo. H. Davies & Co., an established Hawaiian and Philippine trading company, and Reunion Properties in the United Kingdom. Two years later came another wave: Gammon (Hong Kong) in construction, a 75% stake in Zung Fu (motor vehicles), and 53% of Rennies Consolidated Holdings in South Africa. In parallel, Jardines expanded its insurance footprint through acquisitions in the UK and the US, laying the groundwork for what became Jardine Insurance Brokers.

Then, late in the decade, the door they’d been shut out of for a generation cracked open again.

After Deng Xiaoping’s reform and opening up, Jardines re-established a presence on the mainland in 1979. A year later it set up Beijing Air Catering—the first foreign joint venture in China since 1954. The company that had been pushed out wasn’t charging back in. It was returning carefully, testing what “China” would mean in a new era.

By 1980, Jardine had become something different from its pre-1949 self: an Asia-spanning group with operations reaching from Hong Kong and China to Southeast Asia, Australia, Great Britain, southern Africa, the Middle East, and the United States—employing about 37,000 people. It acquired a major insurance broking operation in San Francisco, and extended its motor business to the UK.

And if you want the most everyday symbol of where the firm was headed, it wasn’t a dockyard or a shipping line. It was a convenience store. Jardines opened the first 7-Eleven in Hong Kong, a move that would eventually help make the group—through Dairy Farm—one of the franchise’s biggest operators in Asia.

The pivot had worked: from China-first empire builder to pan-Asian operator. But success has a way of attracting predators. And in Hong Kong’s booming 1980s capital markets, a new class of tycoon was about to notice that the old British hongs looked… vulnerable.

VI. The 1980s Crisis: Hostile Takeovers, the Bermuda Flight, and the Fight for Survival

The 1980s handed Jardine Matheson its biggest corporate survival test since World War II. This time the threat didn’t arrive in uniform, and it didn’t come from Beijing. It came from the trading floor—from a new class of Hong Kong power broker the old colonial establishment hadn’t fully prepared for: Chinese tycoons with capital, ambition, and a feel for the stock market that often outpaced the British hongs.

Throughout the 1970s, old-line British names—Jardine Matheson, Swire, Hutchison, Wheelock Marden—were increasingly being outperformed by locally run, ethnically Chinese hongs. Many of these groups had gone public in the early part of the decade, then spent the long bull market buying assets and building scale inside Hong Kong’s fastest-growing industries. By the time the 1980s began, they weren’t up-and-comers anymore. They were predators.

Two names, in particular, concentrated minds inside Jardine House: Li Ka-shing and Y.K. Pao.

By 1980, Li Ka-shing’s Cheung Kong Holdings had become a dominant force in Hong Kong property—bad news for Hongkong Land, the crown jewel of Jardines’ portfolio. And when shipping magnate Sir Yue-Kong Pao decided in 1979 that his future wasn’t only on the sea, he made a statement with his very first property move: he outbid Jardines for control of Hongkong & Kowloon Wharf.

For Jardines, losing Wharf wasn’t just a deal gone wrong. It was symbolic. A company that had shaped Hong Kong’s waterfront for generations had just been beaten at its own game—by a local tycoon. Worse, it signaled something far more dangerous: if Wharf could be taken, what else could?

Li Ka-shing was already sniffing around both Jardine Matheson and Hongkong Land. The market sensed vulnerability, and in a public-market city like Hong Kong, vulnerability is an invitation.

Taipan David Newbigging’s response was to build defenses—fast. He pushed Jardine Matheson and Hongkong Land into deeper cross-shareholdings with each other, a structure meant to make it effectively impossible for an outsider to gain control of either company. On paper, it was clever. In practice, it was costly. The maneuver loaded both companies with significant debt. And the fight—against Li, against Pao, against the market—forced Jardines to sell its interests in Reunion Properties to raise cash.

From London, the Keswick family watched the situation deteriorate and decided the firm needed a firmer hand on the wheel. In 1983, Simon Keswick returned. He had joined Jardines in 1962, became a director in 1972, left in 1977 to join his brother at Matheson & Co., and then came back to Jardines as senior managing director—soon becoming chairman after his father succeeded in removing Newbigging.

Investors weren’t immediately reassured. A family retaking control can look like retreating into tradition. But Simon moved quickly and practically. He focused on debt reduction and on stabilizing Hongkong Land. To raise cash, he authorized the sale of Jardine Matheson’s majority stake in Rennies Consolidated Holdings for $180.1 million. He also introduced a more decentralized management model, splitting operations into a Hong Kong and China division and an international division—an internal rewire designed to make a sprawling group more controllable under pressure.

But balance sheets weren’t the only problem. Politics was moving under their feet.

In 1984, the Sino-British Joint Declaration confirmed what Hong Kong had feared and expected: the territory would return to Chinese control in 1997. For a company whose origin story ran straight through the Opium War—and whose name still carried that history in Chinese memory—the implications weren’t abstract. They were existential.

So Jardines made a move that looked, to many in Hong Kong, like an escape hatch. In 1984, Jardine Matheson Holdings Limited was formed as the Group’s new holding company, incorporated not in Hong Kong but in Bermuda, a British overseas territory. The point wasn’t sunshine or tax efficiency. It was jurisdiction: staying under British law, under a different takeover code—protection against raiders in the market, and a hedge against whatever 1997 might bring.

With Simon overseeing the rebuild, Jardines also doubled down on an ownership structure built to be extremely hard to crack. In 1986, it incorporated Jardine Strategic and put in place reciprocal share ownership that amplified family control.

The logic was simple even if the mechanics were not: Jardine Matheson owned most of Jardine Strategic, and Jardine Strategic owned a significant stake back in Jardine Matheson. That circular, cross-held stake acted like a corporate moat. A hostile bidder couldn’t just buy shares and win. They’d run into the loop—and the loop was effectively controlled by the Keswicks. Alongside that, Dairy Farm and Mandarin Oriental stayed listed in Hong Kong, with Jardine Strategic holding stakes across these and other group companies.

To critics, it was a fortress—one that entrenched the dynasty and potentially disadvantaged minority shareholders. To supporters, it was stability: long-term stewardship in a city entering an era of political uncertainty and financial aggression.

Either way, the structure would endure for decades. And it would eventually become the center of the modern Jardines story—because what protects you in one era can become a liability in the next.

VII. The 1997 Handover and the China Question (1990s–2010s)

In 1990, after the Bermuda re-domicile and with 1997 getting closer, Jardine Matheson Holdings and four other listed group companies set up primary listings on the London Stock Exchange, alongside their Hong Kong listings. The signal wasn’t subtle: Jardines was widening its footing beyond Hong Kong.

When the handover arrived on July 1, 1997—165 years after William Jardine and James Matheson founded their partnership—the feared corporate stampede didn’t materialize. Hong Kong carried on. And so did Jardines. The operating heart remained in Asia, even if the legal home was now thousands of miles away in Bermuda.

But “carried on” didn’t mean “uncomplicated,” especially when it came to China.

Jardine’s origin story isn’t a neutral one, and it’s not forgotten. As we said earlier, “while these events are absent from Jardine Matheson’s history page on its website, they still resonate in Chinese society. It is never far from the front of public memory in China today.” In Dongguan’s Opium War Museum, portraits of William Jardine and James Matheson hang on the walls—an awkward kind of permanence for a company trying to build trust on the mainland.

And yet, despite that baggage, Jardines’ economic exposure to China kept rising.

There’s a popular narrative that Jardines stayed away—leaning into Southeast Asia while treating mainland China like a risk best avoided. The reality is messier. Hongkong Land, one of the group’s crown jewels, spent US$4.4 billion on a plot of land in Shanghai. Bloomberg’s informal calculations suggest that by 2019, profits from mainland business ventures were the group’s third-largest source, at US$255.4 million.

By 2021, Jardine’s own reporting made the trajectory unmistakable: 55% of profits came from China, versus 42% from Southeast Asia and 3% from the rest of the world. The company that once helped force China open now depended on China for more than half of what it earned.

Through all of that change—wars, listings, restructurings, and a handover that rewrote the political map—the dynasty stayed intact.

Henry Keswick, born in 1938, joined Jardines in 1961 and rotated through Hong Kong, Singapore, and Malaysia. He became a director in 1967, senior managing director in 1970, and chairman in 1972. He retired from those roles in 1975, but later returned to London and served as chairman of Jardine Matheson Holdings until his death in November 2024.

His brother Simon—who had orchestrated the 1980s defenses—served as the company’s taipan from 1983 to 1988, the seventh Keswick to hold the role. Together, Henry and Simon represented the fourth generation of Keswicks in the business.

By then, the fifth generation was already running key parts of the machine. Ben Keswick, Simon’s son, joined the group in 1998 and moved through senior executive roles: finance director and then CEO of Jardine Pacific (2003–2007), group managing director of Jardine Cycle & Carriage (2007–2012), managing director of Jardine Matheson (2012–2020), and taipan from 2012 to 2021. In 2019, he became Executive Chairman of Jardine Matheson.

Another fifth-generation Keswick, Adam Keswick—son of Sir “Chips” Keswick—joined the group in 2001, was appointed to the Board in 2007, and served as Deputy Managing Director from 2012 to 2016. In 2016, he became chairman of Matheson & Co., and he has served as a director of Hongkong Land and Mandarin Oriental.

It’s an extraordinary continuity: the family that married into the firm in the 1830s still controlled it nearly two centuries later. But continuity doesn’t mean stasis. With a new generation in charge, the question became what to do with the fortress they’d inherited—and whether Jardines could modernize without losing the control that had helped it survive.

VIII. Inflection Point #1: The 2018 Jardine Lloyd Thompson Sale

In 2018, Jardines sold its 41% stake in Jardine Lloyd Thompson to Marsh & McLennan. It wasn’t the biggest deal the group had ever done, but it mattered more than the headline suggested—because it quietly marked a change in what Jardines wanted to be.

Marsh & McLennan completed its US$5.6 billion acquisition of Jardine Lloyd Thompson Group plc after announcing the deal in September 2018. For Marsh, the logic was straightforward: JLT strengthened its position across insurance and reinsurance brokerage, health and retirement, and expanded its reach to more than 130 countries.

For Jardines, the meaning ran deeper than simply cashing in an investment.

JLT itself had been born in 1997, when Jardine Insurance Brokers plc—an operation with roots stretching back decades—merged with Lloyd Thompson Group plc. And insurance broking wasn’t some side hobby for the group. Insurance had been part of Jardine’s operating toolkit since the very beginning, back in Canton, when insuring cargo was one of the core services wrapped around its trading business.

So selling wasn’t just a portfolio tidy-up. It was a signal.

By this point, a new generation of Keswick leadership was increasingly steering the group away from constant diversification and toward consolidation—putting more energy into strengthening and simplifying what it already owned, especially in Asia.

Ben Keswick’s approach was noticeably different from the old imperial instinct to expand into ever more geographies and categories. The proceeds from the JLT sale weren’t about building a new global outpost. They were about doubling down on the core Asian businesses—moving from “build the biggest empire possible” toward “own and improve the best assets in Asia.”

Jardines would later describe this direction as becoming an “engaged investor.” In 2018, that shift was still in its early stages. The most consequential—and most controversial—test of it was still ahead.

IX. Inflection Point #2: The Controversial Jardine Strategic Privatization (2021)

The corporate fortress Simon Keswick built in the 1980s—cross-shareholdings designed to make hostile takeovers practically impossible—had done its job. But by 2021, the same structure was starting to look less like a moat and more like a maze. Investors increasingly saw it as needlessly complex, and worse, as a drag on value.

At the center was Jardine Strategic. Jardine Matheson held, directly and indirectly, about 85% of it. And Jardine Strategic, in turn, held roughly 57% of Jardine Matheson. It was circular by design: control reinforcing control.

On March 8, 2021, Jardine Matheson announced it would buy the remaining 15% of Jardine Strategic that it didn’t already own. The mechanism was an amalgamation under the Bermuda Companies Act—Jardine Strategic would merge with a wholly owned subsidiary of Jardine Matheson. Once completed, Jardine Strategic would be taken private and its listings in London, Singapore, and Bermuda would be cancelled. The simplification itself wasn’t controversial. The terms were.

Jardine Matheson offered Jardine Strategic shareholders US$33 per share. But “offer” wasn’t really the right word, because the outcome was effectively predetermined. The deal required approval by at least 75% of the votes cast—and Jardine Matheson already controlled enough votes to guarantee that result.

Minority shareholders didn’t just complain. Some talked about going to court, arguing the buyout effectively captured value from them at a steep discount—figures in the market framed it as roughly a US$1 billion shortfall.

The flashpoint was valuation. On March 11, Jardine Strategic reported a net asset value on a market value basis of US$58.22 per share as of the end of December 2020—far above the US$33 being offered. Minority shareholders argued the offer implied a discount of about 43% to the company’s own stated net asset value.

Groups representing investors echoed the same frustration. They argued the vote offered little protection for minorities: there was no headcount test, no minority veto, and—crucially—under Bermuda law the controlling shareholder could vote its shares at the special general meeting. If you owned almost 85% and only needed 75%, the math wasn’t exactly suspenseful.

The Singapore investors’ association, SIAS, looked into organizing a legal challenge through the Bermuda courts. The path existed in theory: under section 106(6) of the Bermuda Companies Act, a shareholder who didn’t vote in favor could apply to the court to appraise the fair value of their shares. In practice, mounting that kind of challenge from Singapore against a Bermuda-domiciled company was costly, complex, and uncertain—exactly the sort of friction that makes a “right” feel more like a mirage.

In the end, the deal went through. Jardine Matheson paid about US$5.5 billion to acquire the remaining minority stake and, as part of the simplification, Jardine Strategic’s stake in Jardine Matheson was cancelled. The holding structure at the top of the group became dramatically cleaner.

That cleanup had visible accounting consequences. During 2021, the group’s total equity fell by US$4.4 billion to US$58.4 billion, reflecting the simplification and the acquisition of the 15% minority interest in Jardine Strategic completed in April 2021.

So what was it: modernization, or expropriation?

For minority shareholders of Jardine Strategic, the answer felt obvious. The process left a bitter taste, with many feeling they’d been forced out at a price that didn’t reflect the underlying value they owned.

But zoom out, and the event also marked something real: a pivot from the old, defensive, takeover-era architecture toward a more straightforward Jardine Matheson—less of a self-referential web, more like an investment holding company.

The irony is that Jardines built a fortress to survive one era of threats. In 2021, it tore down part of that fortress to survive the next.

X. The 2024-2025 Transformation: From Operator to Engaged Investor

What started in 2021 as a one-time clean-up of an old takeover-defense structure turned into something much bigger. Over 2024 and 2025, Jardine Matheson moved through one of its most concentrated bursts of strategic change in decades—reshaping how it’s structured, who runs it, and, most importantly, what kind of owner it wants to be.

Operationally, 2024 showed why Jardines has always liked being diversified. The group held up well overall, but the performance split cleanly by geography and sector. Challenging conditions on the Chinese mainland weighed on Zhongsheng and Hongkong Land, while DFI Retail bounced back meaningfully. In Southeast Asia, Astra once again did the heavy lifting.

That balance has been shifting. In 2024, about 70% of underlying net profit came from Southeast Asia, with a large share flowing from Indonesia through Astra International. Not long ago, Jardines was reporting that 55% of profits came from China. Now, Southeast Asia—especially Indonesia—looked like the profit engine.

Astra itself remained resilient in 2024, helped by the fact that it isn’t a one-trick pony. Under IFRS, Astra reported consolidated revenue of US$20.7 billion and underlying net profit of US$2.1 billion—revenue marginally higher than the year before, and profit down 4%. In local currency, it reported record earnings, driven by improved performances across much of the portfolio, particularly motorcycle sales, financial services, and infrastructure and logistics.

The operating details underline the same point: Astra kept share even as the market moved against it. Indonesia’s wholesale motorcycle market grew 2% in 2024, while Astra Honda Motor’s sales rose 1%, maintaining a 78% market share. In cars, Astra held a 56% market share even though the wholesale car market fell 14%.

Hongkong Land, meanwhile, began narrowing its focus in a way that would have been hard to imagine during the “own everything” conglomerate years. In October 2024, it announced a new strategy centered on ultra-premium integrated commercial properties in Asia’s gateway cities. The key line was what it would stop doing: it would no longer invest in the build-to-sell segment across Asia, meaning residential and medium-term lease assets.

The strategy was framed as a return to core capabilities—more recurring income, better returns—and it followed the appointment of Michael Smith as Chief Executive on 1 April 2024, after a six-month review. Hongkong Land said it planned to recycle up to US$10 billion of capital by 2035, and that the plan was expected to double profit before interest and tax and double dividends per share. In other words: less breadth, more focus, and a promise of higher-quality earnings.

The first visible step arrived in June 2024, with the launch of the redevelopment of Hongkong Land’s Landmark portfolio in Central. It was pitched as part of a broader effort to transform Central into a world-class destination for luxury retail, lifestyle, and business. The redevelopment involved a US$1 billion strategic investment, with US$400 million funded by the group and US$600 million invested by luxury retail tenants.

Then came the move that made the strategy feel unmistakably directional: taking Mandarin Oriental private.

Jardine Matheson announced it would acquire the remaining 11.96% of Mandarin Oriental Hotel Group that it didn’t already own, in a transaction valuing the brand at $4.2 billion. Through its wholly owned subsidiary Bidco, Jardines offered independent shareholders US$3.35 in cash per share—about a 52.3% premium to the closing price of US$2.20 on 29 September 2025, the “Unaffected Day.”

The group’s rationale was direct. “The Jardine Matheson Board considers full private ownership as beneficial for both Mandarin Oriental and Jardine Matheson. Privatization of Mandarin Oriental would simplify Jardine Matheson’s existing corporate structure, while better supporting Mandarin Oriental in achieving its growth objectives.”

On 8 December 2025, Mandarin Oriental shareholders approved the scheme and related meeting resolutions, with published tallies showing overwhelming support—99.76% of votes cast at the Court Meeting in favor.

For Mandarin Oriental, the timing mattered. Under CEO Laurent Kleitman, who joined in late 2023 from Dior and Coty, the hotel group had been pushing an ambitious growth plan, aiming to double its footprint to between 80 and 100 properties over the next decade. Going private under its controlling shareholder was framed as a way to execute that plan with fewer public-market constraints.

Alongside the portfolio moves came a notable changing of the guard.

In December 2025, Lincoln Pan was appointed Chief Executive Officer of Jardine Matheson. He joined from PAG, where he had been a partner and co-head of Private Equity and a member of the Group Executive Committee. At the same time, Jardine Matheson’s board increasingly featured private equity professionals. Symbolically and practically, the center of gravity was shifting toward a capital-allocation mindset.

There was also a quieter but meaningful dynastic transition. Sir Henry Keswick—Chairman of the group from 1972 to 2018 and, later, Chairman Emeritus—died in November 2024. Jardines announced: “It is with profound sadness that Jardine Matheson announces that Sir Henry Keswick, Chairman Emeritus of Jardine Matheson, has passed away peacefully at age 86 on 5 November 2024.” The following month, Ben Keswick’s cousin Percy Weatherall stepped down from the board. Weatherall, 68, had worked in the group since 1976 and served as CEO for much of the 2000s. Max Planck is paraphrased as saying that science progresses one funeral at a time, and sometimes reform of family companies is similar.

Seen together, these events mattered because Sir Henry had represented continuity with the defensive, fortress-building era of the 1980s. His passing removed a visible anchor to the old order and, with it, a constraint on how far and how fast the group could be reshaped.

Capital allocation started to reflect that shift, too. In early November, Jardine Matheson announced plans to repurchase up to US$250 million of its own shares, with repurchased shares to be cancelled. The buyback was expected to be executed over the course of 2026, and described as consistent with the group’s capital-allocation policy.

Stack it all up—subsidiaries narrowing strategy, simplification through privatizations, buybacks, and a CEO drawn from private equity—and the direction becomes hard to miss. Jardine Matheson itself put the framing on it. As Blennerhassett notes, the group says it is “evolving to align with the changing markets in which our companies operate, and we are transitioning from being an owner-operator of our portfolio assets to being a long-term, engaged investor in our portfolio companies.”

XI. Portfolio Deep Dive: The Engines of Value

To understand Jardine Matheson today, you have to understand the businesses underneath it. Jardines isn’t one company so much as a set of very different engines—each tied to a different corner of Asian growth, and each carrying its own cycle, risks, and upside.

Astra International (via Jardine Cycle & Carriage)

If Jardines has a cash-flow anchor, it’s Astra.

Astra is one of Indonesia’s largest public companies, with a vast ecosystem of some 300 subsidiaries, joint ventures, and associate companies—and more than 190,000 employees. In a market as volatile as Indonesia can be, Astra has built a reputation as one of the country’s best-run corporate machines.

The headline story is still vehicles. Astra held a 56% share of Indonesia’s car market even as the overall wholesale car market fell 14% in 2024. In motorcycles, its position is even more dominant: Astra Honda Motor held a 78% market share.

But the deeper reason Astra matters to Jardines is that it isn’t just an auto company. It’s a diversified platform built around how Indonesians live, move, borrow, and build.

In 2024, net income from Astra’s financial services division rose 6% to IDR8.4 trillion, driven mainly by stronger contributions from consumer finance as loan portfolios grew. Across the consumer finance businesses, new amounts financed increased 9%.

Infrastructure and logistics added another leg. That division reported a 37% increase in net income to IDR1.3 trillion. Astra has interests in 396km of operational toll roads along the Trans-Java network and in the Jakarta Outer Ring Road, and toll road concessions saw 5% higher daily toll revenue during the year.

Even agribusiness moved in the right direction, with net income up 9% to IDR914 billion.

Astra also broadened into healthcare, acquiring a 95.8% stake in Heartology Cardiovascular Hospital in Jakarta, one of Indonesia’s largest private cardiac specialist hospitals. And it continued to push its transition narrative—raising its effective interest to 32.7% in SERD, which owns a large geothermal project in South Sumatra, and reiterating a target of net-zero by 2050 for scope 1 and 2 emissions.

Hongkong Land

Hongkong Land is the old heart of Jardines: founded in 1889, and still synonymous with some of the most prestigious commercial property in Hong Kong’s Central district.

But the last few years have been a reminder that even “trophy assets” don’t get a free pass from cycles—especially when mainland China is involved. For the year ended 31 December 2024, Hongkong Land reported a 44% decrease in underlying profit to US$410 million, attributing the decline to non-cash provisions from its Chinese mainland build-to-sell business.

At the same time, this is the subsidiary where the group’s strategic tightening has become most explicit. The company said that in 2024 it affirmed a new direction: to become the leader in Asia’s gateway cities, focused on ultra-premium integrated commercial properties—and that achieving this ambition means leaning into four long-standing strengths within the business.

It’s also pressing ahead with Shanghai West Bund Central, described as an $8 billion development—one of its biggest and most consequential bets on Shanghai’s future.

DFI Retail Group

If Hongkong Land is about city centers and balance sheets, DFI is about everyday life—groceries, convenience, health and beauty, and the relentless operational grind of retail across Asia.

DFI Retail Group Holdings Limited, headquartered in Hong Kong, is a major East and Southeast Asian retailer involved in the processing and wholesaling of food and health and beauty products.

As of 31 December 2024, the group, its associates, and joint ventures operated more than 10,700 outlets, with over 5,000 stores operated by subsidiaries. Across the broader group structure, it employed more than 190,000 people, including over 45,000 employed by its subsidiaries.

Its brands are household names in the region: Wellcome supermarkets, 7-Eleven convenience stores, Mannings and Guardian health and beauty stores, and IKEA franchises in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Indonesia.

Mandarin Oriental

Mandarin Oriental is the group’s luxury flag: a global brand with Asian roots, built around service, pricing power, and patience.

It manages 43 hotels and 12 branded residences across 27 countries, with openings ahead in Vienna, Rome, Seoul, and Dubai’s Jumeirah Golf Estates.

The privatization move was framed as a way to make faster decisions and align more tightly with long-term goals, as Mandarin Oriental pursues expansion under CEO Laurent Kleitman. At the same time, the hotel group has been refreshing its brand and digital offerings, shifting toward an asset-light business model, and returning to profitability in 2024.

XII. Bull Case, Bear Case, and Strategic Analysis

The Bull Case

The transformation underway at Jardine Matheson has been real, not cosmetic. A CEO with private equity training. A simpler top-level structure. Subsidiaries narrowing their strategies. Capital coming back through buybacks and privatizations. It all points the same way: an old-school conglomerate finally trying to do the one thing investors have asked of it for decades—close the gap between what it owns and what the market is willing to pay for it.

By December 2025, Jardine Matheson’s Singapore-listed shares traded around US$68.6, for a market capitalization of roughly US$20.2 billion. The stock had risen sharply over the prior 12 months and sat just below its 52-week high. That price action matters less as a victory lap than as evidence that the market is, at least for now, willing to believe the “engaged investor” story.

The best supporting argument is diversification away from China through Astra. With dominant positions in Indonesian cars and motorcycles, Astra functions less like a single business and more like a toll booth on Indonesian consumer activity. And Indonesia’s scale and demographics give that exposure a long runway.

Then there’s Hongkong Land. Its pivot toward ultra-premium integrated commercial properties is, strategically, a bet on a very specific reality: in soft office markets, the best buildings don’t behave like the average building. Flight-to-quality is real. Hongkong Land’s Central portfolio has held up better than key benchmarks in the Central Grade A office market, and the new strategy is essentially to lean into that advantage—own fewer things, but own the most defensible things.

The Bear Case

China exposure still matters, even with Southeast Asia doing more of the profit work. And Jardines’ relationship with mainland China is never just commercial. The group’s origin story carries political baggage that is real and remembered, and that makes “geopolitical risk” more than a line item in a slide deck.

The structure is also still complicated. Even after simplification, Jardines remains a multi-layered holding company owning stakes in very different businesses across multiple markets. That makes it hard to value cleanly, and it helps explain why analysts often talk about a persistent discount to net asset value. The group has tried for years to narrow that discount. It has rarely stayed narrowed.

And then there’s governance. The Keswick family’s roughly 33% stake means the controlling shareholders can drive major outcomes without meaningful minority influence. The Jardine Strategic episode made that dynamic impossible to ignore. Even if the group is modernizing operationally, the power structure at the top hasn’t changed much.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants (Low): Most of Jardine’s major businesses have moats built from time and entrenchment—prime property portfolios, long-held distribution relationships, and retail footprints that take decades to assemble.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Moderate): In auto distribution, the manufacturers have leverage, and relationships matter. In retail, supplier power swings widely depending on the category and brand strength.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Moderate to High): Consumers can switch in supermarkets, convenience, and autos. In premium commercial property, the buyers are the world’s most sophisticated tenants—global banks, law firms, and luxury houses—who negotiate hard and have options.

Threat of Substitutes (Moderate): E-commerce pressures physical retail. Work-from-home challenges office demand. Electrification and shifting mobility models pressure traditional auto businesses. The threats vary by subsidiary, but disruption is a constant.

Competitive Rivalry (High in most segments): Jardines competes in crowded arenas—against other Hong Kong and regional conglomerates, including Li Ka-shing’s CK Group and Swire, plus deep local competitors in each market.

Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers Framework

Jardine’s most durable competitive advantages appear to be:

Scale Economies: Astra’s market leadership creates scale benefits in sourcing, dealer networks, service, and financing. DFI’s retail footprint provides purchasing and distribution leverage.

Network Effects: Limited. These are mostly asset-heavy businesses rather than winner-take-most platforms.

Counter-Positioning: The “engaged investor” shift is an attempt to differentiate from the traditional conglomerate model—more autonomy at the operating companies, with the holding company acting as a disciplined allocator of capital.

Switching Costs: High in ultra-premium commercial property where location and prestige matter, and leases are sticky. More moderate in autos, where service relationships can create inertia but not lock-in.

Branding: Strong where it counts—Mandarin Oriental in luxury hospitality, Hongkong Land in prestige property, and Astra as a market leader in Indonesia.

Cornered Resource: Hongkong Land’s Central portfolio is the cleanest example. You can refurbish buildings, but you can’t manufacture more land in Central.

Process Power: If there’s one advantage Jardines has proven over 193 years, it’s organizational survival—an ability to navigate political shocks, market cycles, and structural reinventions that most companies simply don’t live long enough to attempt.

XIII. Key Metrics to Watch

If you want a simple way to track whether Jardine Matheson’s “engaged investor” story is actually working, there are three numbers that do a lot of the heavy lifting:

1. Free Cash Flow at Parent Company: In 2024, free cash flow at the parent company rose 12% to US$875 million (from US$778 million in 2023). That was enough to cover the group’s external dividend payments by about two times. This matters because it’s the cleanest read on the holding company’s real flexibility: the cash it actually receives from subsidiaries after corporate costs—cash it can use for dividends, buybacks, debt reduction, or new investments.

2. Discount to Net Asset Value: Jardines is still, at its core, a holding company. So the key question is whether the market is valuing it anywhere close to what its underlying stakes are worth. The gap between Jardine Matheson’s market value and the combined value of its positions in listed subsidiaries (plus a reasonable estimate for the unlisted pieces) is the scoreboard for whether simplification and better capital allocation are translating into investor confidence.

3. Astra Contribution Growth: Astra has become the group’s most important profit engine. So one of the best single indicators to watch is Astra’s underlying profit growth in local currency terms. When Astra is compounding, the whole Jardines machine tends to look healthier—and when it isn’t, diversification only cushions the story so much.

XIV. Risks and Regulatory Considerations

China has always been the biggest opportunity and the biggest risk in the Jardines story. For all the effort to diversify, the group still depends on the mainland for a meaningful share of profits—and it carries historical baggage there that few multinationals can match. A worsening geopolitical climate, a shift in how foreign-controlled groups are treated, or heightened scrutiny of companies associated with the colonial era could all translate into real commercial headwinds.

If China is the legacy risk, Indonesia is the new concentration risk. With roughly 70% of profits now coming from Southeast Asia, and a large portion of that tied to Astra and the Indonesian economy, the group is more exposed than it’s been in decades to what happens in Jakarta—elections, regulation, currency swings, and policy decisions that can change the rules of the game quickly.

Then there’s Hong Kong itself. Hongkong Land’s Central portfolio is about as close to “irreplaceable” as assets get—but the city around it is changing. Hong Kong’s role as a financial center is evolving, and deeper integration with mainland China creates upside in some scenarios and uncertainty in others. For a business built on premium tenants and confidence, sentiment matters.

Governance is another risk that investors can’t unsee once they’ve seen it. The Jardine Strategic privatization left many minority shareholders feeling that family control—and the ability to execute a predetermined outcome—came ahead of minority economics. Even if the holding structure has been simplified since, future privatizations or related-party transactions will be judged through the lens of that episode.

Finally, there’s the risk that shows up not in headlines, but in footnotes. Non-cash provisions tied to Hongkong Land’s mainland build-to-sell business weighed heavily on 2024 results. Property valuations, impairment assumptions, and the timing of recognizing losses can all swing reported performance. These are accounting judgments, but for a group with as much property exposure as Jardines, they can materially shape how the market perceives the underlying business.

XV. Conclusion: A Company in Transformation

Nearly two centuries after William Jardine walked into Lord Palmerston’s office with a war plan, the company he founded faced another inflection point. The question was no longer whether Jardine Matheson could survive—it had already proved that through Japanese occupation, communist revolution, hostile takeovers, and decolonization. The question was whether it could thrive in a world where the old advantages of a colonial-era hong had been overtaken by faster-moving, more transparent, and often more focused competitors.

Ben Keswick used the appointment of a new CEO to reinforce the direction of travel. In Jardine’s own framing, the group had been moving away from its historical owner-operator model and toward being an engaged investor—less about personally running every operating company, more about allocating capital, simplifying, and driving long-term returns.

The evidence was hard to miss: leadership drawn from private equity, fewer holding-company knots, sharper strategies inside major subsidiaries, and capital coming back to shareholders through buybacks and privatizations. The open question—and the one public investors keep circling—is whether this time the changes actually shrink the long-running conglomerate discount, or whether the market keeps treating Jardines as a complicated structure you can admire but not fully trust.

What makes the story so compelling is that the group isn’t just associated with Hong Kong. It helped build the place. From the trams along the streets to the towers that define Central’s skyline, from the Star Ferry to the Mandarin Oriental, Jardines’ fingerprints are embedded in the city’s daily life.

And yet the legacy is not a clean one. Not far away on the mainland, portraits of William Jardine and James Matheson still hang in Dongguan’s Opium War Museum—an unblinking reminder that the company’s origin story is inseparable from a national trauma China has never forgotten.

In the near term, there was no shortage of things for investors to watch: insider-buying disclosures, an ongoing buyback program, and the Mandarin Oriental privatization working its way through formal approvals. But the larger setup stayed the same. Jardines is a multi-business holding company: the upside often comes from better capital allocation and a narrowing gap between share price and underlying assets, while the downside tends to arrive when macro conditions hit several portfolio companies at once.

The hong that built Hong Kong was reinventing itself again. History suggests that underestimating the Keswicks’ capacity to adapt is usually a mistake. But history also offers a sharper warning: even the most durable commercial empires don’t get immortality for free. The next chapter of this 193-year-old story was being written in real time.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music