Infratil: The Quiet Infrastructure Giant That Spotted the Future

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

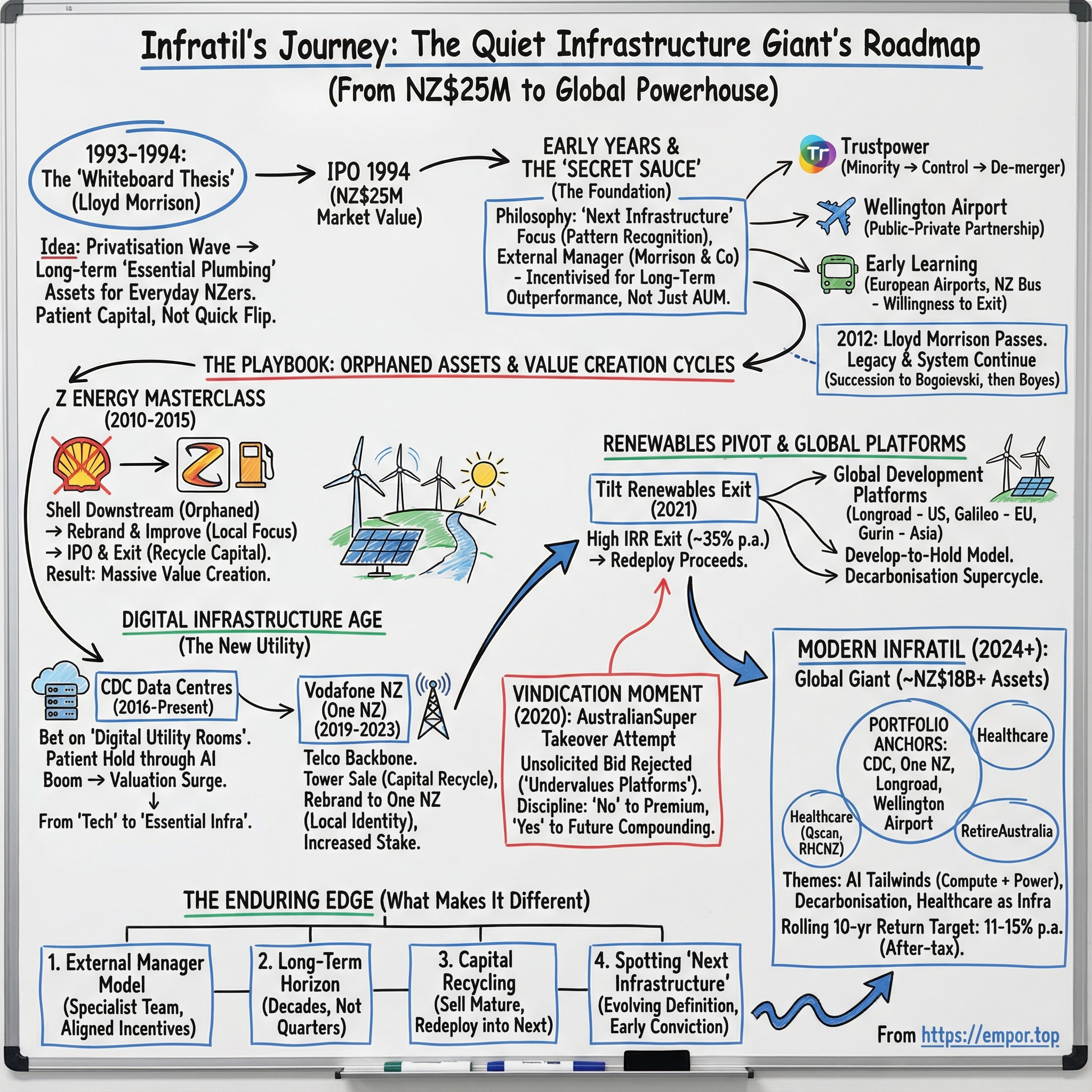

Picture a rain-slicked Wellington evening in late 1993. In a modest office overlooking the harbour, a 36-year-old merchant banker named Lloyd Morrison is at a whiteboard, mapping out an idea that feels almost too big for the room.

New Zealand is deep into a privatisation wave. The government is selling assets, markets are opening up, and pieces of the country’s infrastructure are coming loose—power generation, airports, telecom networks. Most people see a one-time sell-down. Morrison sees something else entirely: the essential plumbing of modern life changing hands. Whoever buys these assets won’t just own businesses. They’ll own the arteries of the economy for decades.

And Morrison has a provocative question: why should that future belong only to institutions and offshore capital? Why not everyday New Zealanders?

In 1994, he turns that whiteboard thesis into a company. Under Lloyd’s leadership, Morrison forms Infratil—one of the world’s earliest listed infrastructure investment vehicles. It’s built specifically to capture the opportunities created by New Zealand’s privatisation programme. In hindsight, the timing is almost unfair: New Zealand turns out to be an early mover in what becomes a global, decades-long shift toward private ownership and investment in infrastructure.

Fast-forward about three decades and the thing Morrison willed into existence has grown into a quiet giant. Infratil is now an infrastructure investor spanning renewables, digital infrastructure, healthcare, and airports. Its businesses operate across New Zealand, Australia, Asia, Europe, and the United States. With group assets now above NZ$18 billion, Infratil targets long-term after-tax shareholder returns of 11–15% a year.

The compounding is the kind that stops you mid-sentence. A $10,000 investment at the IPO would have grown to $202,620 by September 2025—an 18.4% annualised after-tax return over 31.5 years. Over the same period, the NZX50 delivered about 6.4% a year.

This is the story of how a small New Zealand fund—launched in the privatisation era with just NZ$25 million of market value—became a global infrastructure powerhouse. More importantly, it’s a story about pattern recognition: how Infratil kept identifying tomorrow’s “must-have” assets before the rest of the market even agreed they counted as infrastructure.

You’ll see that playbook repeat again and again: Wellington Airport, Canberra data centres, Shell’s service stations reborn as Z Energy, Vodafone’s towers. And the most interesting part is what isn’t in the recipe. This wasn’t a leverage-fuelled roll-up or a clever financial arbitrage. The edge was harder to copy: patient capital, deep operating focus, and the conviction to buy “next infrastructure” early—then hold long enough to let the world catch up.

II. Lloyd Morrison & The Origin Story

If Infratil has a “secret sauce,” it starts with the person who designed the kitchen.

Hugh Richmond Lloyd Morrison CNZM (18 September 1957 – 10 February 2012) was a Wellington-based investment banker and entrepreneur who mixed hard-nosed analysis with unusually broad curiosity. In 1988, he founded H.R.L. Morrison & Co. Six years later, Morrison & Co launched Infratil—one of the earliest listed infrastructure investment vehicles anywhere.

Morrison grew up in Palmerston North, went to Wanganui Collegiate, then studied law at the University of Canterbury, graduating with an LL.B (Hons). He didn’t become an infrastructure investor by following a straight line. He became one by collecting the right experiences early—and then connecting them faster than everyone else.

His career began in the early 1980s as an investment analyst with Jarden & Co (now Jarden). He later became a partner at O’Connor Grieve & Co. By 1985, he was in London as executive chairman of OmniCorp, a New Zealand-listed investment company based there. OmniCorp was sold in 1988, and Morrison returned home with something more valuable than a résumé line: a view of how long-lived, essential assets could behave when they were treated like businesses, not public utilities.

That London chapter mattered. Morrison saw that infrastructure—especially utility-like assets—could throw off dependable cash flows and offer protection against inflation. In Australasia, at the time, that wasn’t a widely held mental model. Back in Wellington, it became one of his.

He founded Morrison & Co in 1988 as an investment advisory firm serving both private and public sector clients in New Zealand and Australia. But as the early 1990s arrived, the firm narrowed its focus. Privatisations were accelerating across New Zealand and Australia, and Morrison wasn’t interested in being a generalist when a once-in-a-generation asset shuffle was underway.

The timing couldn’t have been better. New Zealand in the late 1980s and early 1990s ran one of the most aggressive privatisation programmes in the developed world. Governments sold off telecommunications, electricity generation, ports, and airports. To many, it looked like a wave of one-off transactions. Morrison saw something more enduring: the chance to buy critical, often monopoly or near-monopoly assets at prices that wouldn’t be available again.

“Infratil predated everything,” said longtime Morrison senior executive Tim Brown. “In 1994, the only [company like Infratil] Lloyd was able to find was Foreign & Colonial Special Utilities Trust,” run by Duncan Saville—a shareholder of Infratil and a mentor to Morrison.

But the real innovation wasn’t only what Infratil would buy. It was how Morrison structured the vehicle so it could wait for the right moments. From the beginning, Infratil took a patient approach to investing, backed by a fee structure that didn’t push the firm to buy assets “at any cost.” That’s not a minor detail—it’s the difference between an investor and a collector. Rather than leaning on the typical incentives of assets-under-management fees that reward growth for growth’s sake, Morrison set up a model designed to align manager and shareholder outcomes around long-term performance.

And Morrison wasn’t just a finance mind. He was energetic, intellectual, and a compassionate entrepreneur with deep cultural interests. He supported the arts in New Zealand and founded the HRL Morrison Music Trust in 1995 to promote New Zealand musicians and composers, including through its record label, Trust Records. He also served as a trustee of the Chamber Music NZ Foundation and as a director of the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra.

He brought that same civic impulse into public life. In 2003, he launched a campaign to change the New Zealand flag. In 2008, he published a discussion document titled “A Measurable Goal for New Zealand,” aiming to define a shared national ambition people could rally around.

The recognition followed. Morrison was named New Zealand Executive of the Year by Deloitte/Management magazine in 2007, and “Business Leader of the Year” by the New Zealand Herald in 2006. In 2007, he ranked 12th on the New Zealand Listener Power List. In the 2010 New Year Honours, he was appointed a Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to business.

What ultimately set him apart, though, was a simple belief that most investors only learn much later: infrastructure isn’t a fixed category. The assets society relies on change over time. The infrastructure that mattered in 1994 wouldn’t be the same set that mattered decades later. That instinct—treating infrastructure as “what the world can’t function without next,” not “what the world couldn’t function without last”—became Infratil’s enduring edge.

III. The Pioneering Years: First to Market (1994–2005)

Infratil arrived early. When it listed on the New Zealand Exchange in 1994, the idea of a publicly traded infrastructure investor was still exotic. Its first move was modest on paper: a minority stake in Trustpower. But the way it went about that investment was the tell.

Instead of reaching for control on day one, Infratil built its position over time. It studied the business, learned the regulatory rhythms, and waited. Trustpower would become its biggest investment, but it took a decade to move from a small holding to control. That wasn’t hesitation. It was a philosophy: infrastructure rewards patience, and forced buying usually means overpaying.

The incentives were designed to make that patience rational. Morrison & Co’s management fee sat in a relatively narrow band—about 0.80% to 1.125%, based on company value. The incentive fee was 20% of outperformance above a 12% hurdle rate, and it applied only to non-New Zealand assets. A November report by Fidato Advisory found the base fees were broadly in line with comparable funds, and that the hurdle rate was actually higher. In plain terms: Morrison & Co didn’t get paid just for getting bigger. They got paid for being right.

Then came the first truly signature deal. In 1998, Infratil bought into Wellington Airport—66% sold by the Crown, with Wellington City Council taking the remaining 34%. It was a smart structure for a politically sensitive asset: keep the city as a partner, not an opponent.

Wellington Airport was exactly the kind of infrastructure Morrison loved: essential, hard to replicate, and woven into daily life. It serves Wellington and central New Zealand, with around 5.5 million passengers a year. The airport sits on 110 hectares of freehold land just 8km from the CBD—close enough that “the airport” and “the city” feel like one system.

And Infratil didn’t treat it like a trade. Wellington Airport stayed in the portfolio, a long-running proof point that Infratil was building something different from the five-to-seven-year hold mindset that often comes with private equity-style infrastructure funds.

Not every early bet was that clean. In the 2000s, Infratil pushed offshore into European airports—Glasgow Prestwick Airport and Manston Airport (both sold in November 2013), and Lübeck Airport, where Infratil exercised its put option and transferred its 90% shareholding to the City of Lübeck on 30 October 2009. These were mixed outcomes at best, and that mattered too. The lesson wasn’t “airports are bad.” It was that secondary airports in competitive markets, under unfamiliar regulation, can turn into a grind fast. Crucially, Infratil was willing to exit when the facts changed.

In 2005, it added something very different: NZ Bus, acquired outright from Stagecoach. This wasn’t a passive asset with a tidy concession agreement. It was an operating business—messier, more exposed to politics and public sentiment, and much harder to “set and forget.” Infratil ultimately sold NZ Bus to Australian equity firm Next Capital, with the sale announced on 24 December 2018 and completed in June 2019 following a consenting process.

Looked at in isolation, these early investments can seem eclectic: a power company, an airport, European aviation adventures, a bus operator. But together they built the muscle that mattered. Infratil learned how to price long-lived assets, navigate regulators, partner with government stakeholders, improve operations, and—just as important—recognise when an asset no longer fit. Those capabilities would become the foundation for the much bigger inflection points still to come.

IV. The Z Energy Masterclass: Creating a National Champion (2010–2015)

In late 2009, as the global financial crisis began to loosen its grip, a strange kind of deal appeared on the market. Shell—the Anglo-Dutch oil major—was doing what big multinationals do after a shock: pruning the tree. Around the world, it reviewed its downstream businesses. And down in New Zealand, the network of service stations, trucks, terminals, and distribution contracts didn’t make the cut. It was “non-core” compared to Shell’s higher-priority upstream ambitions.

For most buyers, that label is a warning sign. For Morrison & Co and Infratil, it was the opportunity.

They had a simple, contrarian view: an orphaned asset isn’t the same thing as a bad asset. Shell’s New Zealand downstream business wasn’t broken. It was just overlooked—run by a global parent that had bigger ponds to fish in. Under local ownership, with management attention and the right capital structure, it could become something much more valuable than a subsidiary at the edge of a global empire.

On 29 March 2010, a consortium owned 50% by Infratil and 50% by the Guardians of New Zealand Superannuation executed a sale and purchase agreement to acquire Shell New Zealand’s distribution and retail businesses, plus a 17.1% interest in the New Zealand Refining Company. The deal completed on 1 April 2010. The business was initially named Greenstone Energy, and in May 2011 it began rebranding the service stations as Z.

That partnership with the NZ Super Fund mattered. It let Infratil pursue a larger transaction without stretching its own balance sheet, while keeping the discipline that had defined the firm from the start. It also gave the deal instant credibility: this wasn’t a quick flip artist buying petrol stations. This was long-term domestic capital taking stewardship of a national network. The co-investment model would become a recurring pattern later on.

As Mark Flesher, corporate development executive at Infratil manager Morrison & Co, put it to BusinessDesk: “It has been a fantastic investment.” Infratil’s 2010 annual report described the Shell acquisition as one of the “positives from the turmoil”—a counter-cyclical transaction that allowed it to “invest in a market-leading business at a price which reflected a low level of competition amongst prospective buyers.”

The timing helped. In the wake of the crisis, not many buyers wanted something capital-intensive and operationally complex. Infratil’s habit of staying financially flexible—rather than squeezing every last drop of leverage in the good years—meant it could move when others couldn’t.

Then came the boldest move: stripping off the Shell identity.

Chief executive Mike Bennetts said the cost of using the Shell brand—believed to be about NZ$10 million a year—was a factor. But the switch from Shell to Z wasn’t just about saving a licensing fee. It was a statement. This wasn’t going to be a distant outpost of a multinational anymore. It was going to be a New Zealand company, with local ownership, local accountability, and a brand built for the communities it served.

Under the hood, the capital structure changed too. The net outlay by Infratil and the New Zealand Superannuation Fund for 100% of Z Energy in 2010 was effectively $320 million. By March 2013, Z Energy had $430 million of retail bonds outstanding—up from zero debt at acquisition.

That combination—active operational work and a more deliberate balance sheet—meant the investors were able to pull significant value forward while still building the business.

And then they did what Infratil does when an asset is ready for the next chapter: they opened it up to the public markets.

In July 2013, Z Energy floated in an IPO priced at $3.50 per share. With 400 million shares on issue, the listing implied a market capitalisation of $1.4 billion—almost four and a half times the consortium’s effective net cash outlay just three years earlier.

Infratil ultimately sold its remaining 20% stake in Z Energy in September 2015, booking a profit of $392 million on that final sell-down.

Zoom out, and you can see why this deal became legendary inside the Infratil story. It wasn’t just “buy infrastructure and hold.” It was a full value-creation cycle: spot an orphaned asset inside a multinational, partner with aligned long-term capital to acquire it, rebuild the business with local identity and sharper execution, monetise through an IPO, and recycle the proceeds into the next wave.

In other words: a playbook. And Infratil was about to run it again—this time in sectors the market hadn’t yet learned to call “infrastructure.”

V. Loss of the Founder & Leadership Transition (2012)

In early 2009, at the peak of his powers, Lloyd Morrison got the news every driven, future-focused builder dreads. He had leukaemia.

After feeling flat and rundown, Morrison underwent tests that confirmed acute myeloid leukaemia. The disease had adverse cytogenetics—DNA abnormalities that meant standard treatment options in New Zealand weren’t likely to be enough. In February 2009, he moved to Seattle to be treated with experimental drugs at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Centre.

He kept showing up anyway. Even while battling the disease, Morrison stayed close to the business and continued mentoring the next generation of leadership. When he died of leukaemia on 10 February 2012 in Seattle, aged 54, he left behind his wife and five children—and a country that had lost one of its most original business minds.

But the institution he built didn’t collapse with him.

Infratil was, in many ways, an extension of Morrison himself: inspirational leadership, vision, charisma, and relentless energy. He was also a deeply passionate New Zealander who made a lasting contribution not just to business, but to the arts community as a friend, colleague, patron, and mentor. In 2015, the New Zealand Business Hall of Fame posthumously inducted Lloyd as a Laureate.

The most important proof of Morrison’s legacy wasn’t in the tributes, though. It was in the handover.

The succession to Marko Bogoievski had been planned carefully. A former Telecom CFO, Bogoievski joined Morrison & Co with deep experience in exactly the kinds of industries Infratil would lean into next—telecommunications and energy. He replaced Infratil founder Lloyd Morrison as head of Infratil and its manager, Morrison & Co, in 2009, and continued as chief executive of Morrison & Co. It was under Bogoievski that Infratil embarked on the Shell New Zealand downstream investment that became Z Energy—and began moving into data centres and international renewable energy platforms.

Over the years that followed, the scale of the moves got bigger, not smaller. Under Bogoievski’s leadership, Infratil executed some of its most transformational deals, including the CDC Data Centres investment and the Vodafone NZ acquisition. The transition was smooth because it wasn’t just a change in CEO—it was a system Morrison had designed to keep working. The external manager structure, with Morrison & Co as a separately owned entity managing Infratil’s investments, helped ensure continuity even as individuals came and went.

In 2021, another chapter turn arrived. The Infratil Board announced that Jason Boyes would succeed Marko Bogoievski as Infratil Chief Executive Officer and a Director, effective from 1 April 2021, with Bogoievski stepping down after 12 years as CEO and a Director.

Boyes had joined Morrison & Co in 2011 after a 15-year legal career in corporate finance and M&A in New Zealand and London. He represented the next generation of leadership: steeped in the culture that Morrison built, but taking the helm in a world where “infrastructure” was rapidly being redefined.

VI. First Inflection Point: The Data Centre Bet (2016–Present)

By the mid-2010s, Infratil had already proven it could take “old infrastructure” and make it better. The next leap was recognising that the world was quietly building a new kind of essential asset—one that didn’t look like an airport or a power station, but was becoming just as fundamental.

In 2016, while many infrastructure investors still gravitated to toll roads, regulated utilities, and transport hubs, Infratil moved into data centres. It backed Canberra Data Centres, or CDC, a business founded in 2007 that had built a reputation for high-security, high-reliability facilities. Infratil first invested in CDC in 2016 alongside the Commonwealth Superannuation Corporation.

Infratil has today completed its acquisition of a 48% interest in Canberra Data Centres (CDC).

At the time, that didn’t read like a classic infrastructure deal. Data centres were often treated as “tech”: fast-moving, at risk of obsolescence, and hard to value with the familiar infrastructure toolkit. Infratil’s view was simpler, and more structural. Data centres weren’t tech toys—they were the utility rooms of the internet. If commerce, government, and daily life were moving online, then the buildings that kept the digital world running were going to become mission-critical.

CDC’s customer base validated the thesis. Hyperscale cloud providers—like Microsoft’s Azure—needed secure, resilient capacity to serve enterprise and government workloads. Australia’s data sovereignty requirements strengthened the moat further, because CDC’s security credentials positioned it to host sensitive systems that couldn’t easily be shifted offshore or into just any facility.

And then the numbers started catching up to the narrative.

By late 2023, independent valuations were already marking the step-change. The 30 September 2023 valuation of Infratil’s stake in CDC increased by A$448 million over the prior six months. Infratil’s 47.99% investment was valued at between A$3,641 million and A$4,186 million (midpoint A$3,884 million), up from a midpoint of A$3,436 million at 31 March 2023.

As generative AI moved from curiosity to economic force, the tailwind strengthened again. Infratil chief executive Jason Boyes said CDC was well positioned to benefit from growing demand for AI services because of its “data centre design, operating model, and customer base,” adding: “These market dynamics have seen a significant uptick in inbound customer interest.”

By September 2024, the valuations had moved higher once more. Infratil’s 48.17% investment in CDC was valued at between A$4,485 million and A$5,385 million (midpoint A$4,924 million), up from a midpoint of A$4,811 million at the end of September 2024.

Canberra-based CDC Data Centres was worth $17 billion last year and is continuing to grow.

Operationally, CDC kept expanding into a platform, not a collection of buildings. It had 14 Australian sites in operation and seven in development across Sydney, Canberra, Melbourne, and Auckland. It was also in advanced negotiations with customers for more than 400MW of capacity expected to come online over the next four to five years. To meet that demand, CDC began developing a new Sydney campus at Marsden Park, lifting future build capacity by 661MW to 1,197MW and bringing total planned capacity to 1,887MW.

And the build didn’t slow. Construction officially began on CDC’s $2.7 billion Laverton data campus in Melbourne, with a groundbreaking in February 2025.

What makes CDC such a clean example of the Infratil approach isn’t just that it worked—it’s that it required a kind of patience many investors don’t have. From the initial 2016 investment through the AI-fuelled surge of 2023 to 2025, nearly a decade passed. You could have sold earlier and still looked smart. But holding through multiple valuation cycles is how you capture the full compounding: not only the organic growth, but the market’s eventual realisation that this wasn’t “tech” at all.

It was infrastructure—just the next generation of it.

VII. Second Inflection Point: Vodafone NZ Acquisition (2019–2023)

If CDC was Infratil betting on the physical backbone of the internet, Vodafone New Zealand was the next logical move: the network that actually reaches people’s pockets.

In 2019, Vodafone sold its New Zealand arm for the cash equivalent of $3.4 billion to a 50:50 consortium made up of Infratil and Canadian investment firm Brookfield Asset Management. It was Infratil’s biggest deal to date, and its most ambitious push into digital connectivity.

The strategic logic was straightforward. Buying New Zealand’s leading mobile telecommunications company would be transformational for Infratil: it strengthened the cash-generative core of the portfolio, increased exposure to long-term data and connectivity growth, and complemented the CDC investment. In other words, Infratil wasn’t just buying a telco. It was buying a key utility of modern life—one with growing demand and a direct line into the country’s digital future.

Infratil chairman Mark Tume framed it in a way that made the pattern explicit: “Infratil has already successfully demonstrated its ability to reinvigorate a standalone New Zealand entity that was formerly owned by a multinational corporation and create value for our shareholders in the process. Our 2010 acquisition of Shell's New Zealand downstream assets (now Z Energy) is an example of our ability to enhance a significant New Zealand infrastructure business.”

That was the thesis: the Z Energy playbook, deployed again. Acquire an orphaned asset from a multinational, partner with a capable co-investor, back local management, and create value through operational improvement.

The funding structure matched the scale. The NZ$3.4 billion purchase price was to be funded through a NZ$1,029 million equity contribution from each of Infratil and Brookfield, with the balance funded from Vodafone NZ-level debt and a portion of equity reserved for the Vodafone NZ executive team.

Brookfield’s involvement brought deep infrastructure experience, capital, and credibility. But Infratil also understood the trade-off: Brookfield’s fund structure has finite investment periods. An eventual exit wasn’t a risk—it was part of the likely roadmap.

One value-creation lever showed up quickly: the towers.

Vodafone New Zealand, owned by Brookfield and Infratil, sold its 1,484 towers, via Aotearoa Towers, for NZ$1.7 billion to InfraRed Capital (HICL) and Northleaf. It was a classic infrastructure move: separate the passive, long-life assets from the operating business, sell those passive assets to buyers who prize stability, and use the proceeds to strengthen the remaining company. Infratil also noted, with reference to a recent independent valuation, that it expected to have generated a 26.7% IRR on its investment in Vodafone NZ following completion of the transaction.

As expected, Brookfield later sought an exit as its fund approached maturity. Infratil agreed to pay $1.8 billion to lift its stake in One NZ (formerly Vodafone NZ) from 49.95% to 99.90% by buying out Brookfield. Infratil said it would fund the deal through a mix of $850 million of new shares, cash, and $950 million of debt facilities. The transaction valued the telco at an enterprise value of $5.9 billion.

One NZ chief executive Jason Paris called Infratil’s increased investment a “huge vote of confidence,” adding: “[The investment] means this important New Zealand company will be 100 percent locally owned and managed for the first time.”

And then came the branding moment that made the Z Energy parallels impossible to miss. Vodafone became One NZ—dropping the multinational identity in favour of a distinctly local one. By the end of the journey, One NZ had become the largest telecommunications investment in Infratil’s history, and a central pillar in its digital infrastructure portfolio.

VIII. Third Inflection Point: Tilt Renewables & Global Renewables Pivot

Even as Infratil was building out its digital infrastructure stack, it was also reshaping a second pillar of the portfolio: renewables. The turning point was Tilt Renewables—and what Infratil did next with the money.

In 2021, Infratil completed the sale of its 65.15% stake in Tilt Renewables Limited for gross proceeds of $1,984 million (after adjusting for the dividend paid by Tilt Renewables on 30 July 2021).

The deal landed exactly the kind of outcome infrastructure investors dream about, and almost never get. Infratil estimated an accounting gain on the disposal (after estimated incentive fees) of $965 million. More strikingly, it said the Tilt investment generated an internal rate of return of approximately 35.2% per annum (after incentive fees) since Tilt was demerged from Trustpower in 2016.

A roughly 35% annual return over five years is extraordinary. But the real story wasn’t just the exit—it was the pivot. Infratil didn’t simply recycle the proceeds into another familiar Australasian generator. It used Tilt to scale up into something bigger: a diversified, global renewables platform built around development capability.

Longroad Energy became a key expression of that strategy. Boston-headquartered Longroad is a renewable energy developer focused on developing, owning, operating, and managing wind and solar projects across the United States. Since 2016, it developed and acquired 3.2GW of wind and solar projects, retaining 2.4GW. It also built a 28GW development pipeline spanning wind, solar, solar plus storage, and standalone storage assets across 13 states.

In one major step forward, Longroad Energy Holdings, LLC announced a $500 million equity investment by MEAG, acting as the asset management arm for entities of Munich Re, alongside two existing investors: the NZ Super Fund and Infratil. The investment was intended to support Longroad’s shift from a primarily “develop to sell” model toward greater long-term ownership, and to accelerate the expansion of its owned portfolio—from 1.5GW to 8.5GW of wind, solar, and storage projects over the next five years.

For Infratil, it was another example of getting in early and compounding alongside the platform. At completion of the transaction, Infratil had invested a net US$112 million in Longroad since 2016 and achieved an IRR of 59% p.a., based on the US$800 million pre-money valuation of its stake implied by the transaction.

This is a subtly different game from buying “finished” assets. Instead of paying full price for operating wind farms and solar parks, Infratil backed development platforms—teams that can originate projects, navigate permitting, secure offtake, build, and then decide whether to hold or sell. It can create more value, but only if you have the operational depth and the patience to live through multi-year development cycles.

The bet also rides a massive structural wave. Representing 22% of Infratil’s total investments, renewable energy development is framed by the company as one of the largest investment opportunities in history, with over US$4 trillion of investment in wind and solar assets forecast over the next decade.

And Longroad wasn’t meant to be a one-off. Infratil built renewables platforms across multiple continents. Galileo Energy is a pan-European, multi-technology renewable energy developer, owner and operator headquartered in Zurich, Switzerland. Galileo had a 12.5GW development pipeline as at 31 March 2024, and Infratil owns 38% of the business.

In Asia, it backed Gurin Energy, a Singapore-headquartered renewable energy developer focused on developing, owning, and operating wind and solar projects, as well as storage. Infratil owns 95% of Gurin Energy.

The through-line is diversification with intent: multiple markets, multiple power systems, and multiple regulatory regimes—so Infratil isn’t forced to make every renewables decision inside the constraints of any single geography. It can push capital toward the best risk-adjusted opportunities, while building repeatable operating expertise across the portfolio.

IX. The AustralianSuper Takeover Attempt: Vindication (2020)

In December 2020, right as Infratil was reshaping its portfolio and leaning harder into “next infrastructure,” an uninvited bidder showed up with a very old-school move: a straight-up takeover attempt.

Australia’s largest pension fund, AustralianSuper, made an unsolicited offer that valued Infratil at about $5.37 billion—roughly a 28% premium to the prior closing share price. It was pitched as a compelling, take-the-money-now moment for shareholders.

AustralianSuper’s rationale was simple. Infratil owned a collection of high-quality, long-life assets across New Zealand and Australia, and AustralianSuper wanted them. Its Head of Infrastructure, Nik Kemp, framed it as a natural extension of AustralianSuper’s infrastructure ambitions and pointed to the fund’s existing investment footprint in New Zealand as evidence of long-term commitment.

Infratil’s response was just as simple. No.

The board rejected the bid, saying it materially undervalued the company. Marko Bogoievski was blunt about what the offer missed: “Both proposals were unsolicited and materially undervalue our significant renewable energy and digital infrastructure platforms. We expect some of the additional value to be demonstrated in the near term with the recently announced strategic review of Tilt Renewables, which will continue, and ongoing appreciation of the value of CDC Data Centres.”

It wasn’t a costless decision. A premium like that is hard to wave away, and the debate quickly shifted to the institutions. ACC, with a 6.9% stake, appeared open to a deal. Fisher Funds, holding about 5%, signaled the offer wasn’t enough—though it wanted to hear more.

But Infratil’s board wasn’t valuing the company as a bundle of mature assets. It was valuing it as a set of platforms with embedded upside—especially CDC, which was positioned to ride the accelerating shift toward digitalisation and cloud adoption, a theme that only intensified through 2020 and beyond. The offer also reflected what AustralianSuper did and didn’t want: it reportedly had little interest in Trustpower, and the proposal was structured to give Infratil shareholders a direct holding of Trustpower shares as part of the payment.

With hindsight, the “no” looks less like stubbornness and more like discipline. By 24 December 2025, Infratil’s market capitalisation was about NZ$11.084 billion—more than double the level implied by AustralianSuper’s approach.

That’s the real lesson of the AustralianSuper episode: the difference between a price and a value. A board with less conviction could have treated a big premium as the finish line. Infratil treated it as an anchor—one that would have locked shareholders out of the compounding that was still ahead.

X. The Modern Portfolio: Digital Infrastructure Age (2024–Today)

By 2024, the company Lloyd Morrison sketched on a Wellington whiteboard had become something far bigger than a New Zealand utility investor. Infratil Limited is now a New Zealand-headquartered, global infrastructure investment company listed on both the NZX and ASX (NZX: IFT, ASX: IFT). Its purpose is simple and distinctive: invest wisely in ideas that matter, and turn that into long-term value for shareholders. The portfolio spans renewables, digital infrastructure, healthcare, and airports, with operations across New Zealand, Australia, Europe, Asia, and the United States.

What’s striking is how clearly the portfolio tells the story of Infratil’s evolution. Four anchor investments now make up about three-quarters of portfolio value: CDC Data Centres, One NZ, Longroad Energy, and Wellington Airport. Around that core sits the next layer of platforms and operators—healthcare (Qscan and RHCNZ Medical Imaging), additional renewables platforms (Galileo, Gurīn Energy, Mint Renewables), and RetireAustralia.

If there was a single lens through which markets looked at Infratil through most of 2024, it was AI. Investors weren’t just excited about software models; they were trying to price the physical knock-on effects. For Infratil, that meant accelerating demand for data centre space—and the electricity required to run it. As the year went on, the focus sharpened further: not just “is AI big,” but “how fast is the acceleration, and who is positioned to supply the picks and shovels?”

That’s where the portfolio starts to click together. Data centres don’t just need power; increasingly, their customers want renewable power. Owning exposure to both data centres and renewable development creates real potential for portfolio-level synergies: the ability to pair digital infrastructure growth with cleaner generation and a more compelling proposition for the largest, most demanding customers.

Operationally, the year wasn’t frictionless. Infratil summed it up like this: “Overall, the operating results were pleasing, particularly given inflationary pressures heading into the year, significant change programmes at One NZ and Qscan, airline fleet shortages affecting Wellington Airport, regulatory uncertainty for Longroad Energy and RHCNZ Medical Imaging, and global market volatility. One NZ's above target performance stands out, given the difficulties the New Zealand economy has faced, and demonstrates the differentiated position of our business. CDC and Longroad's strong growth continued.”

Healthcare is the other big “new infrastructure” signal in today’s portfolio. Qscan—one of Australia’s largest radiology providers—operates over 70 clinics and delivers diagnostic imaging services like x-rays, ultrasound, CT scans, and MRI scans. Infratil owns 58% of Qscan.

In New Zealand, the RHCNZ Medical Imaging Group is the country’s largest diagnostic imaging provider. The combined group operates over 70 clinics nationwide, with 31 clinics in the South Island and 39 in the North Island. Infratil owns 50.3% of RHCNZ Medical Imaging Group.

This isn’t healthcare as a venture bet. It’s healthcare as infrastructure: essential services, hard to replicate, with real barriers to entry—expensive machines, regulatory requirements, and scarce trained staff—plus demand that tends to be resilient thanks to demographics. And, true to form, there’s also room for what Infratil likes best: operational improvement through scale and technology.

Still, public markets don’t grade on operational nuance. Shareholder returns were -2.6% for the full year, after being up 18.2% in the first nine months. That reversal is a useful reminder of the environment infrastructure investors live in now: even when the underlying businesses are performing, mark-to-market movements and accounting revaluations can dominate the headline result.

That tension showed up clearly in the latest fiscal year. The reported loss was influenced by accounting adjustments—particularly revaluation effects from consolidating One NZ—while the operating businesses continued to perform and, in key cases, grow. In other words: the score on the screen moved around, but the engines kept running.

XI. Playbook: What Makes Infratil Different

After all the dealmaking and reinvention, the interesting question isn’t “what did Infratil buy?” It’s “how did they keep doing it?” Because across airports, petrol stations, data centres, telcos, and renewables platforms, the same set of habits shows up again and again.

The External Manager Model

Infratil is externally managed by Morrison & Co. That structure is unusual, and it cuts both ways.

On the upside, Infratil gets access to a specialist team with deep investment and operating capability without carrying the full overhead of a large, fully integrated internal organisation. Morrison & Co also manages multiple funds and mandates, which helps spread fixed costs and makes it easier to attract and retain talent than a single-vehicle platform might.

But it’s also a real business in its own right. The management contract is a valuable asset for Morrison & Co, which has collected annual fees in excess of $100m in recent years. In practice, that means the contract can’t simply be wished away—Morrison & Co would reasonably expect meaningful compensation to give it up.

The obvious worry with any external manager is misalignment: what if the manager’s incentives drift away from shareholders’? Infratil’s answer is that the fee structure leans heavily toward performance, and the culture has been built around long-term alignment. Morrison & Co is primarily owned by its staff and the estate of the founder, which keeps the people making decisions economically tied to the outcomes.

The Long-Term Holding Strategy

Infratil targets annual after-tax shareholder returns of 11–15% over rolling 10-year horizons, delivered through a mix of share price appreciation and dividends. That wording matters. It’s explicitly built for decades, not quarters—an acknowledgement that infrastructure is cyclical, that timing matters, and that the best outcomes often come from waiting rather than constantly trading.

This sits in sharp contrast to private equity-style infrastructure funds that typically work to 3–7 year hold periods. Infratil’s listed, permanent attaching capital allows it to think in longer arcs: buy early, improve the asset, fund growth, and stay long enough for the compounding to show up.

The Co-Investment Model

Infratil repeatedly partners with long-duration institutions like the NZ Super Fund, Australia’s Future Fund, and Commonwealth Superannuation Corporation. These partnerships do three things.

They allow Infratil to do larger deals than it could comfortably do alone. They add governance and expertise around the table. And they act as a kind of external proof point: if a sophisticated sovereign or pension partner is underwriting the same thesis, it sends a signal to the market that this isn’t a lonely conviction.

Capital Recycling

Infratil is happy to hold assets for a long time—but it’s not sentimental. When an investment matures, re-rates, or reaches a point where the next dollar earns less than it could elsewhere, Infratil has shown a willingness to sell and redeploy.

The Z Energy exit at roughly four times cost, the Tilt Renewables sale at a 35% IRR, and the Vodafone tower transaction all fit the same pattern: crystallise value when it’s there, then recycle capital into the next platform with a longer runway. The discipline is in not holding “forever” just because something is working, if the opportunity cost has changed.

Spotting "Next Infrastructure"

The most distinctive element might be the simplest to state and the hardest to replicate: Infratil has repeatedly treated “infrastructure” as a moving target.

Data centres in 2016 are the cleanest example. While much of the infrastructure world was still anchored on toll roads and traditional utilities, Infratil leaned into the idea that the physical backbone of the digital economy would become just as essential—and eventually valued that way too.

That kind of pattern recognition requires sector depth, comfort being early, and the willingness to tolerate periods where the thesis hasn’t become consensus yet. But when it works, it’s not just a good investment. It resets what the market thinks the company is.

XII. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

It’s hard to “start a new Infratil.” The advantage isn’t just capital; it’s credibility, relationships, and a compounding track record built over decades. The kinds of assets Infratil now targets also come with built-in gates. Data centres require enormous upfront investment and long development timelines. Telecom networks depend on spectrum licences that governments release sparingly. Airports are natural monopolies, and when they do change hands, it’s rare—and political.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Some of Infratil’s most important inputs are increasingly scarce. CDC needs reliable power and the right land in the right places, both of which can be constrained in key markets. Renewables development relies on global supply chains for turbines, panels, and specialist components, and those have seen disruption. Scale helps, and long-term power purchase agreements can reduce volatility, but supplier pressure doesn’t disappear.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: LOW-MODERATE

CDC sells to customers like Microsoft and AWS running workloads that can’t go down—and can’t simply be lifted and shifted on a whim. Data sovereignty and security requirements further entrench those relationships, raising switching costs. One NZ serves consumers who can technically change carriers, but real-world frictions matter: contracts, device financing, and the hassle factor. Wellington Airport sits in the cleanest position of all: it’s the capital’s primary gateway, and there isn’t a substitute across town.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW

Infratil sits under services people can’t easily do without. Cloud computing still needs physical data centres. Getting to and from Wellington by air still runs through the airport. Mobile connectivity remains an essential utility. If there’s a substitution trend here, it’s one working in Infratil’s favour: the shift away from fossil fuels toward renewables, which expands the opportunity set for its renewable platforms.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

Competition varies by segment. Data centres are competitive globally, but CDC’s positioning in Australia and New Zealand, combined with government security credentials, makes parts of its market more defensible than they look from the outside. New Zealand telecommunications is a mature three-player market, which tends to be competitive but also relatively stable. Renewables development remains fragmented, though the direction of travel is toward consolidation around platforms with real origination and execution capability.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies

CDC operates the largest privately owned data centre business in Australia and New Zealand, and scale matters: it drives procurement leverage, operational repeatability, and the ability to serve hyperscale customers who need meaningful capacity. One NZ’s network reaches more than 98% of New Zealanders; matching that footprint would require enormous investment, and it would still take years.

Network Effects

These aren’t social networks, but network effects still show up. CDC benefits from ecosystem effects as customers cluster for interconnection and lower latency. One NZ benefits more directly: as the subscriber base grows, the network becomes more valuable to users through reach and reliability perceptions.

Counter-Positioning

Infratil’s listed, long-duration structure is a genuine competitive weapon. Traditional private equity infrastructure funds face the gravity of a fund lifecycle: at some point, they must sell. Infratil doesn’t. That freedom changes behaviour. It can buy earlier, invest through volatility, and hold when the best move is simply to keep compounding.

Switching Costs

In data centres, switching can be painful and risky—migrating workloads takes time, engineering effort, and careful change management. In telecom, switching costs are more moderate but still real, shaped by contracts, bundled services, and customer inertia. For airlines and airport ecosystems, switching costs are high: routes, slots, and operational logistics create stickiness.

Cornered Resource

Over time, Infratil has built relationships with long-duration co-investors, including sovereign wealth and pension partners. Those partnerships can function like a cornered resource: they provide repeat access to capital, alignment for large deals, and credibility that’s difficult to replicate quickly.

Process Power

Morrison & Co’s advantage is also procedural. The ability to consistently spot “next infrastructure,” execute complex transactions, and then operate and improve businesses isn’t a single insight—it’s an institutional capability, refined over decades.

Branding

“Infrastructure” is political. Being known as a responsible, long-term owner can matter as much as price when assets are sensitive and stakeholders are watching. Infratil’s reputation helps it win trust with governments, regulators, and sellers—and that trust can translate into access to deal flow others never see.

Key Metrics for Investors

If you’re following Infratil as a long-term owner, there are three indicators that tend to matter more than the quarter-to-quarter noise.

1. CDC Contracted Capacity and Development Pipeline

CDC is the portfolio’s biggest near-term growth engine, and the cleanest way to track that engine is capacity: what’s already contracted, what’s under construction, and what’s realistically coming through the pipeline. The shift from hundreds of megawatts operating to a pipeline measured in the high thousands is the tangible footprint of the AI-and-cloud demand surge. Watch the pace of new contracted capacity, whether builds stay on track, and how concentrated the customer base becomes as CDC scales.

2. Proportionate EBITDAF Growth

Infratil’s preferred operating measure, Proportionate EBITDAF, is meant to show what the businesses are actually earning for shareholders—across both investments it consolidates and investments it doesn’t. That matters because reported earnings can swing around with revaluations and accounting treatment changes, especially in a portfolio that includes big stakes in privately valued assets. Over time, steady growth in Proportionate EBITDAF is one of the simplest signals that the underlying operations are doing what the story says they’re doing.

3. Capital Recycling Activity and Returns

Infratil’s compounding has never been just about holding assets; it’s been about knowing when to crystallise value and move on. When management sells something mature at an attractive valuation and redeploys into the next platform with a longer runway, it resets the portfolio’s growth curve. So it’s worth tracking both sides of the equation: the quality of exits—like the Tilt Renewables sale at an approximately 35% IRR, and the value created through Z Energy—and what the company does with that capital next. That’s where the capital allocation skill shows up most clearly.

Risks and Considerations

Regulatory Risk

Infrastructure is never “set and forget,” because the rules of the game can change mid-play. Data centres are increasingly in the spotlight for their power needs. Telecoms lives under ongoing oversight. And renewables economics can swing with policy support—things like tax credits and renewable standards. A shift in any of these regulatory regimes can change timelines, costs, and ultimately returns.

Concentration Risk

Infratil is geographically diverse, but it isn’t evenly spread. A relatively small number of big positions drive a lot of the outcome—especially CDC, which makes up a substantial share of portfolio value. That’s great when the flywheel is spinning. It’s painful if something material goes wrong at a core holding, because it flows straight through to overall performance.

Management Fee Structure

The external manager model is part of what makes Infratil work—but it also introduces a real tension. Morrison & Co is a separate business earning management and incentive fees, and whenever a manager gets paid, the question becomes: paid for what, and when? The structure is designed to align interests, but shareholders still need to keep an eye on incentive fee calculations and how capital is deployed across the portfolio.

Execution Risk on Development Platforms

There’s a big difference between buying a mature asset and building one. Infratil’s renewables push leans heavily into development platforms like Longroad, Galileo, and Gurīn—businesses that have to originate projects, secure approvals, manage construction, and then operate what they build. Delays, cost blowouts, grid connection issues, or permitting failures don’t just slow growth; they can permanently reshape returns.

Currency Risk

With a portfolio spanning New Zealand dollars, Australian dollars, US dollars, and euros, currency moves matter. Even when the underlying businesses perform, exchange rates can amplify results or mute them—creating real volatility in reported returns that has nothing to do with operating performance.

Conclusion

Infratil’s journey—from a NZ$25 million IPO in 1994 to roughly an NZ$11 billion market capitalisation today—is one of the standout infrastructure investing stories anywhere. More than three decades of 18%+ compounding doesn’t happen by accident. It’s what you get when patient capital meets sector knowledge, disciplined incentives, and the willingness to look a little strange at the moment you place the bet.

What makes the story feel unfinished, not wrapped up, is where Infratil now sits. The portfolio is concentrated around two supercycles that are still early: the digitisation of everything, and the decarbonisation of energy. The AI boom has poured fuel on CDC’s growth, while simultaneously putting a brighter spotlight on the power question—how you generate it, where it comes from, and how reliably you can deliver it. Infratil’s unusual advantage is that it isn’t only exposed to demand for compute; it’s also building platforms that can help meet the demand for clean electricity that compute requires.

But the questions that matter now aren’t about whether the company can find good assets. They’re about whether it can keep its edge as the world catches on. Can Infratil continue to identify “next infrastructure” in a market where everyone is hunting the same themes? Does the external manager model that was so distinctive in 1994 stay the right structure as the company grows larger and more complex? And how does Infratil operate through a world of higher interest rates, where the valuation math for long-duration assets can change quickly?

Even with those open questions, the through-line is clear. Lloyd Morrison’s core idea—give everyday investors access to the essential assets that make society run, and manage those assets with a long-term, owner’s mindset—has held up. The institution survived the founder’s passing because it was built to: a culture of alignment, a repeatable approach to value creation, and a comfort with holding through cycles rather than trading through headlines.

From Wellington to Canberra, from Boston to Singapore, Infratil now owns stakes in the systems modern life depends on: the airport that connects a capital city, the networks that carry our voices and data, the buildings that host the cloud, and the renewables platforms trying to power what comes next. Which brings the story right back to that Wellington whiteboard in 1993. Morrison’s insight wasn’t just that infrastructure is valuable.

It was that the definition of “infrastructure” keeps moving—and the real money gets made by the investors who move with it.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music