Insurance Australia Group: Australia's General Insurance Giant

I. Introduction: The Hidden Insurance Empire

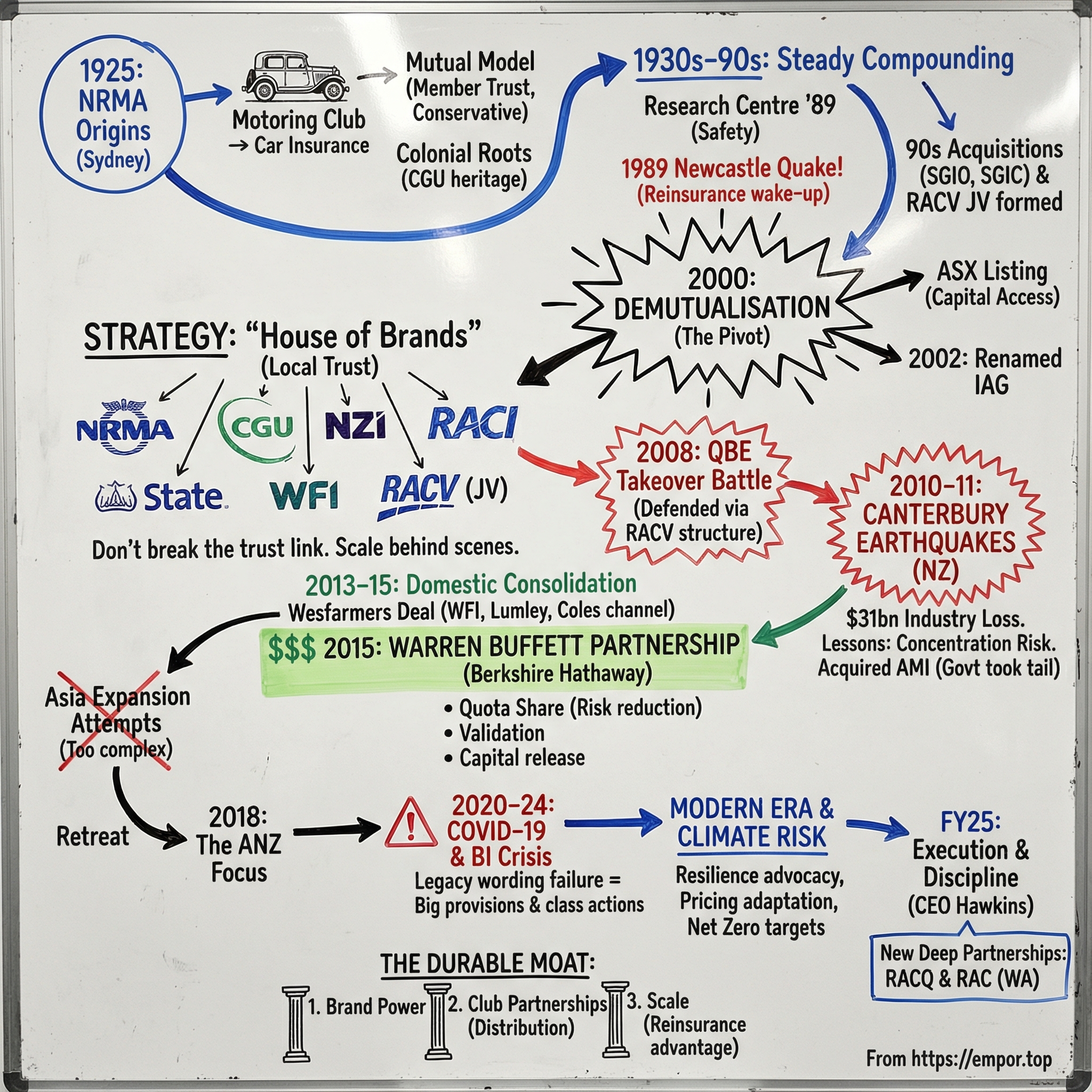

Picture Sydney in 1925. The streets are dusty and chaotic, and cars are suddenly everywhere. Motoring is freedom—but it’s also a brand-new kind of financial risk. If you crash, if your car is stolen, if something goes wrong on the road, you don’t just lose a machine. You can lose your livelihood.

That’s the gap the National Roads and Motorists’ Association stepped into when it began offering insurance to its members. It was a practical add-on for a motoring club. It also turned out to be the seed of one of the most important financial institutions in Australia and New Zealand.

Fast forward a century and that early insurance offering has grown into Insurance Australia Group Limited, or IAG: a multinational insurer, the largest general insurer in Australia, and the largest in New Zealand through its subsidiary, IAG New Zealand. Across the group, IAG underwrites more than $14 billion of premium a year, selling policies through a lineup of household names—NRMA Insurance, CGU, Swann Insurance, WFI, and ROLLiN in Australia; and NZI, State, and AMI in New Zealand.

But here’s what makes IAG so easy to miss: almost no customer thinks they’re “with IAG.”

IAG is the parent company—a quiet holding company sitting above a deliberately assembled collection of local brands. Walk through Melbourne, Brisbane, or Auckland and you’ll spot NRMA, CGU, State, AMI, and others. You won’t see “IAG” on a shopfront or a billboard. That’s not an accident. It’s the strategy: keep the brands people already trust, and build scale behind the scenes.

So the real question isn’t just how IAG got big. It’s how it stayed standing while the world kept testing it. How did a motoring association’s insurance arm become the dominant general insurer across Australasia—surviving demutualisation, takeover attempts, earthquakes, pandemics, and regulatory battles?

Along the way, a few themes keep resurfacing: the compounding advantage of trusted local brands; the hidden machinery of reinsurance that decides whether insurers live or die after catastrophes; the rising shadow of climate risk; and, eventually, why Warren Buffett—at 84—made his first-ever Australian investment by backing this company.

II. Origins: The Motoring Association and the Birth of Australian Insurance

Australia in the 1920s was reinventing itself around the automobile. Federation was still young, distances were enormous, and the car promised a new kind of freedom—weekends away, faster commerce, a bigger world. It also brought a new kind of anxiety. Roads were rough. Driving was dangerous. And if you smashed up your car or injured someone, there wasn’t much of a financial backstop.

That’s the problem the National Roads and Motorists’ Association stepped into. On 25 May 1925, the NRMA began offering insurance to its members—simple, practical protection for Australia’s early motorists. It took off quickly, and by 1926 NRMA Insurance had expanded into home insurance too. The product line was growing in the most natural way possible: once people trusted you with their car, trusting you with their house wasn’t a huge leap.

NRMA’s secret weapon wasn’t clever advertising or financial engineering. It was the mutual model. In a mutual, the policyholders are the owners. There are no outside shareholders to satisfy, no constant pressure to squeeze out quarterly growth at any cost. The goal is service and stability, and any surplus can be ploughed back into better coverage, better claims handling, or better pricing. Over time, that structure built something insurers can’t buy: trust. NRMA wasn’t a distant institution. It was the organisation that helped members on the road and showed up when things went wrong. It felt local. It felt like it belonged to you.

And while the NRMA story is the direct root of what becomes IAG, the company’s ancestry reaches further back. Through its CGU business, IAG inherited a second lineage—one that stretches back around 160 years to colonial-era insurers that arrived with British settlers and started underwriting Australian risk long before modern Australia took shape.

The NRMA itself had been providing insurance to motorists in NSW and the ACT from the 1920s and grew steadily from there, expanding across the country and becoming one of the largest general insurers in the market.

For most of the 20th century, the mutual model was a perfect fit. NRMA Insurance could play the long game: patient capital, conservative management, deep relationships, and a focus on looking after members when they needed it most.

But that same structure came with a ceiling. Mutuals don’t raise equity capital quickly. They can’t issue shares to fund big acquisitions. And as the insurance industry began consolidating in the late 20th century, the pressure started to build: could a member-owned insurer keep pace in a world increasingly dominated by capital-rich giants?

III. Building the NRMA Insurance Powerhouse (1930s–1990s)

For most of the 20th century, NRMA Insurance didn’t grow through splashy reinventions. It grew the old-fashioned way: member loyalty, careful underwriting, and decades of showing up when people needed it. No dramatic pivots. Just steady compounding—trust turning into premiums, premiums turning into capital, and capital reinforcing the trust.

In 1989, NRMA Insurance did something no other insurer in Australasia had attempted: it opened its own Research Centre. Instead of only pricing risk, it started studying it—vehicle safety, security, and repair technologies. The Centre went on to play a major role in improving car safety and reducing theft, including developing Australia’s first car security rating system and helping spark national theft-reduction and road-safety initiatives.

It was classic NRMA thinking. If you can understand what causes losses—and help prevent them—you don’t just become a payer of claims. You become part of the system that lowers the odds those claims happen in the first place. That’s good for customers, and it’s very good for the insurer.

Then, in December 1989, nature delivered a reminder that not all risk comes with warning labels. Newcastle, on the east coast of New South Wales, was hit by a significant earthquake that damaged homes and infrastructure across the city. For NRMA Insurance, it triggered a rethink of earthquake exposure in Australia—and a review of its approach to reinsurance and catastrophe modelling.

The Newcastle quake punctured a comfortable assumption: that Australia was largely insulated from seismic catastrophe compared with its Pacific neighbours. The event killed 13 people and caused more than $4 billion in damage. NRMA Insurance responded by advocating for stricter building codes and reassessing how it protected itself with reinsurance. The lesson was simple: even “safe” markets can produce extreme losses, and insurers survive by preparing before the ground starts shaking.

In the 1990s, NRMA’s ambitions expanded beyond its original heartland. It acquired the SGIO Group, including SGIO Insurance—the largest fire and general insurer in Western Australia—and SGIC, the largest general insurer in South Australia. Just as importantly, it kept those brands intact. The strategy was becoming clear: buy trust where it already exists, then build scale behind it. If Western Australians trusted SGIO because it felt local, why risk breaking that connection?

Around the same time, NRMA formed a joint venture between its insurance businesses and the Royal Automobile Club of Victoria (RACV). It became one of the most durable partnerships in the group’s history—and later, one of the most strategically important relationships IAG would have.

By the late 1990s, NRMA Insurance had grown from a NSW-based mutual into a national force with meaningful presence across the country. But the mutual structure still imposed a constraint: limited ability to raise equity capital quickly, and limited flexibility to play the consolidation game at full speed. Globally, insurers were demutualising to access capital markets. That wave was now lapping at Australia’s shore.

NRMA Insurance wasn’t being asked whether it would change. It was being asked when—and what it would become on the other side.

IV. Demutualisation and the Creation of IAG (2000–2003)

In 2000, NRMA Insurance hit the biggest fork-in-the-road moment in its history: it stopped being a mutual owned by its members and became a public company owned by shareholders. It was a structural change that rewired incentives, governance, and the company’s capacity to expand—while trying to hold on to the trust it had spent decades building.

In July 2000, the NRMA Insurance business demutualised, separating from NRMA and issuing shares to NRMA members. Millions of Australians who’d only ever known the relationship as “I pay premiums, you’ve got my back” suddenly became shareholders, handed tradeable pieces of the business based on their connection to the organisation. The newly formed NRMA Insurance Group Limited listed on the Australian Securities Exchange, and for the first time, the insurer could tap public markets for capital.

That’s the real “why” behind demutualisation. The industry was consolidating, technology was getting more expensive, and scale was becoming a weapon. Mutuals can compound patiently, but they don’t raise equity quickly. In a market starting to be shaped by acquisition and investment, that began to look less like prudence and more like a handicap.

Then came the identity shift. NRMA Insurance Group Limited changed its name to Insurance Australia Group Limited on 15 January 2002. It wasn’t just cosmetic. “NRMA” anchored the company to a motoring association heritage and a particular geography. “Insurance Australia Group” signalled something bigger: a platform built to own multiple insurance businesses across Australia and New Zealand.

What followed was an acquisition sprint that rapidly broadened both scale and capability. IAG acquired CGU in Australia (including Swann Insurance), NZI in New Zealand, and Zurich Insurance’s NSW workers’ compensation business. It also acquired New Zealand’s largest general insurance company, State Insurance, and picked up the policies and renewal rights to HIH’s Australian workers’ compensation business.

The CGU deal in 2003 was especially pivotal. It didn’t just add volume—it changed what IAG was. CGU brought a major presence in commercial and intermediated insurance, areas where NRMA’s roots were thinner. And it brought history: through CGU, IAG inherited around 160 years of experience providing insurance services in Australia, a lineage reaching back to colonial-era underwriting.

The timing mattered, too, because the early 2000s were brutal for Australian insurance. HIH Insurance collapsed in 2001 with $5.3 billion in losses—Australia’s largest corporate failure. It left customers scrambling for coverage and the industry’s credibility badly damaged. In that environment, IAG’s relative stability became a competitive advantage. While others were disappearing, IAG could step in, absorb HIH’s workers’ compensation renewal rights, and look like what the market urgently needed: a safe pair of hands.

By the end of this period, the blueprint for modern IAG was set. Not one master consumer brand, but a holding company built around multiple trusted names—kept distinct because trust is local, and once you break it, you don’t easily get it back.

V. The Multi-Brand Strategy and Geographic Expansion (2003–2012)

The “house of brands” model IAG built through its acquisition spree wasn’t a quirk. It was the strategy—and it shaped how the company would win.

Because IAG absolutely could have gone the other way. It could have taken every brand it bought—CGU, SGIO, SGIC, NZI, State—and rolled them into one national banner, splashing a single logo across every policy and every billboard. Plenty of acquirers do exactly that. One brand. One message. One marketing budget.

IAG didn’t.

Instead, it leaned into the idea that in insurance, trust is intensely local. People don’t just buy a product; they buy a promise. And that promise only matters when life goes sideways—when your car is written off, when your roof is gone, when you’re filing a claim at the worst moment of your year. In that moment, customers reach for the name they already believe will pick up the phone and do the right thing. You can’t manufacture that belief overnight, and you definitely don’t want to accidentally break it by slapping a new name on the front.

The RACV partnership is the cleanest example. IAG has a 70% shareholding in Insurance Manufacturers of Australia Pty Limited, with the other 30% held by RACV. That entity issues insurance under the RACV Insurance name, sold by RACV in Victoria. To the customer, it’s RACV. It feels like RACV. But behind the scenes, IAG is underwriting the policies and managing the risk. Victorians aren’t being asked to “switch” to some interstate brand; they’re being offered insurance by the institution they already associate with membership, roadside help, and local service.

That same logic applied across the map. SGIO meant something specific in Western Australia. SGIC carried weight in South Australia. State Insurance had generations of history in New Zealand. Keeping those brands wasn’t sentimentality—it was a recognition that brand equity in insurance is hard-won, and easily destroyed.

There was also a distribution advantage baked into this approach. The automobile clubs—RACV in Victoria, RACQ in Queensland, RAC in Western Australia—had enormous member bases and physical networks. They weren’t just trusted brands; they were ready-made insurance storefronts. Partnering with them, rather than trying to out-market them, gave IAG access to customers through relationships that were already there.

While it was cementing this multi-brand machine at home, IAG also started looking offshore. It acquired UK insurer Equity Insurance Group. It increased its presence in Asia, building out its business in Thailand and moving into Malaysia. It also established a joint venture with the State Bank of India to offer general insurance products.

And it didn’t stop there. In April 2012, IAG acquired a 20% strategic interest in Bohai Property Insurance Company Ltd, headquartered in Tianjin in Northern China. In September 2012, IAG’s 49%-owned Malaysian associate, AmG, completed the acquisition of Kurnia Insurans (Malaysia) Berhad, which made AmG the largest general insurer in Malaysia.

This was IAG at its most expansive: a dominant Australasian insurer trying to become a broader regional player. The pitch was straightforward. Australia and New Zealand were mature markets. Asia looked like growth—rising middle classes, low insurance penetration, and huge populations still moving into the kinds of assets that people insure.

But the playbook that worked in Australia and New Zealand didn’t travel easily. In its home markets, IAG had deep brand trust, long-standing partnerships, and hard-earned institutional know-how. In unfamiliar markets, it had to build those advantages from scratch—while navigating different regulations, different competitive dynamics, and different distribution realities.

For a while, IAG pushed ahead anyway. But the cracks in that ambition would matter later.

VI. The QBE Takeover Battle (2008)

In the autumn of 2008, IAG ran into a different kind of catastrophe risk: not an earthquake or a storm, but a takeover bid from QBE Insurance, Australia’s largest global insurer. It was the closest IAG came to losing its independence—and the fight that followed would expose just how valuable IAG’s partnership-heavy model really was.

The idea wasn’t new. In 2004, speculation swirled that IAG would merge with QBE. IAG denied it. The rumours resurfaced in 2006. Denied again.

And on paper, the logic was obvious. QBE was a global specialist insurer, spread across roughly 40 countries. IAG was the domestic champion with deep franchises in Australia and New Zealand. Put them together and you’d have a combined group that could sit among the world’s top tier of general insurers.

Then QBE made it real.

On 10 April 2008, QBE proposed a takeover: each IAG share would be exchanged for 0.135 QBE shares plus 50 cents cash—an implied value of $3.75 per IAG share at the time. IAG’s board rejected it the next day.

QBE came back quickly with a revised proposal: 0.142 QBE shares plus 70 cents cash per IAG share. IAG rejected that one too, on 14 April.

By mid-May, QBE escalated again: 0.145 QBE shares plus 90 cents cash, implying $4.60 per IAG share at the time. IAG rejected it four days later. On 21 May 2008, QBE confirmed talks had collapsed and withdrew.

Publicly, the argument was blunt. IAG said it could not recommend the “inadequate and incomplete” proposal to shareholders. It argued the bid was priced opportunistically, taking advantage of short-term weakness in IAG’s share price, and didn’t reflect IAG’s underlying value—or the synergies QBE itself seemed to believe were there.

But price was only the headline.

Underneath was a strategic conviction: IAG believed its focus—dominating markets it understood deeply, through brands and distribution relationships it could defend—was better than QBE’s model of global diversification, with all the complexity and execution risk that comes with running across dozens of markets.

And there was another factor that made a hostile acquisition unusually hard: one of IAG’s crown-jewel distribution relationships carried a built-in tripwire.

In Victoria, IAG’s short-tail personal insurance products are distributed under the RACV brand through a joint venture structure. The policies are “manufactured” by Insurance Manufacturers of Australia Pty Limited (IMA), which is 70% owned by IAG and 30% by RACV. If one shareholder experiences a change of control, the other has a pre-emptive right to acquire that shareholder’s interest in IMA at market value.

In other words, if QBE bought IAG, RACV could respond by buying IAG’s stake in the Victorian joint venture—potentially stripping out a major part of what QBE thought it was acquiring. The same partnership model that helped IAG win customers also doubled as a defense against an unwanted buyer.

So QBE walked away. IAG stayed independent.

And while IAG’s board didn’t win the argument by predicting the future, it was making a bet: that the best insurance business isn’t necessarily the one spread across the most countries, but the one that owns the most trust, in the places it knows best.

VII. The Canterbury Earthquakes: A Stress Test for the Industry (2010–2012)

On 4 September 2010, a magnitude 7.1 earthquake hit near Christchurch, New Zealand. It was frightening and disruptive—buildings cracked, roads buckled, utilities failed—but remarkably, no one was killed. The insurance industry did what it always does after a major event: it triaged, mobilised assessors, started processing claims, and began the long work of rebuilding.

And, quietly, many assumed the worst had passed.

It hadn’t.

Over the next months, Canterbury kept shaking. And in February 2011, the sequence delivered the blow that would define the disaster: a 6.3-magnitude intraplate quake that struck close to Christchurch. It was smaller than the September quake on paper, but it was nearer, shallower, and far more destructive. The human toll was devastating. One hundred and eighty-five people died.

In economic terms, it was a once-in-a-generation rupture. Adjusted for inflation, the 2010–2011 Canterbury earthquakes caused over $52.2 billion in damage, making it New Zealand’s costliest natural disaster and one of the most expensive disasters in history.

The insured bill was staggering, too. The combined events cost private insurers more than NZ$21 billion. Toka Tū Ake EQC paid a further $10 billion. In total, insured costs ran to more than $31 billion.

But beyond the headline numbers, Canterbury revealed something more uncomfortable: the structure of the insurance market itself could be a source of fragility. And no company embodied that more clearly than AMI Insurance.

AMI was New Zealand-owned, a mutual with deep roots in Canterbury—and a huge footprint there. It was the country’s second-biggest residential insurer, with 485,000 policyholders and about 1.2 million policies, including 51,000 in Christchurch alone. In Canterbury, it had more than 30% market share in fire and general insurance.

That local strength became a trap.

When the epicentre of the country’s insurance catastrophe overlapped with the epicentre of AMI’s customer base, the losses didn’t just rise—they concentrated. AMI’s exposure outstripped what its reserves and reinsurance could handle. The company faced a $76 million shortfall against its $198.6 million regulatory capital requirement, and the pressure forced a controversial outcome: AMI would be sold.

In December 2011, IAG New Zealand agreed to buy AMI Insurance. The deal was framed as a stabiliser for the Canterbury insurance market and a way to reduce the Crown’s liability. And it came with a crucial design choice: the Crown took over ownership of AMI’s Canterbury earthquake-related claims.

IAG paid NZD 380 million for what AMI could still offer going forward—the brand, the branch network, and the nationwide insurance business of almost 500,000 customers holding about 1.2 million policies. IAG also agreed to continue offering insurance to AMI customers, alongside its existing customers, on renewal and transfers in Canterbury and throughout New Zealand.

That split was the whole point. IAG got the living business. The government kept the earthquake tail.

Those pre-5 April 2012 Canterbury claims moved into Southern Response, a government-owned company created to settle AMI policyholders’ earthquake damage. It was an elegant structure: it allowed IAG to expand in New Zealand without inheriting a decade’s worth of unpredictable catastrophe claims.

By this point, IAG New Zealand already owned major names like NZI and State. Adding AMI pushed IAG to an even more dominant position—covering about 60% of the domestic insurance market.

Canterbury left the industry with hard-earned lessons. Geographic concentration can be existential. Reinsurance programs need to withstand scenarios that feel, in advance, almost unthinkable. And catastrophe claims don’t end when the ground stops moving—they can run on for years, sometimes longer, keeping uncertainty alive in reserves and financial results.

Even well after the event, the earthquakes continued to shape IAG’s outcomes. The company’s underlying profit margin rose from 14.2% to 15.9% during a period with few natural disasters, but the shadow of the 2011 Canterbury earthquakes still lingered—proof that in insurance, the past doesn’t stay in the past.

VIII. The Wesfarmers Acquisition and Domestic Consolidation (2013–2015)

If Canterbury was a brutal lesson in how quickly concentrated risk can break an insurer, IAG’s next big move wasn’t to chase growth in more countries. It was to deepen its grip on Australia and New Zealand—by widening what it sold, and how it reached customers.

In December 2013, IAG announced it would buy the insurance underwriting businesses of Wesfarmers Limited for $1.845 billion. The package included the underwriting companies behind the WFI and Lumley brands, plus something just as valuable: a ten-year distribution agreement with Coles.

This was IAG’s biggest acquisition to date, and it wasn’t about adding another logo to the portfolio. It was about rounding out the machine.

Wesfarmers Federation Insurance, or WFI, brought something IAG didn’t fully have: a premier rural insurer with deep relationships in agricultural communities across the country, built through decades of local presence. Lumley brought strength in intermediated commercial insurance—business written through brokers, where relationships and service matter as much as price. Together, they filled meaningful gaps and pushed IAG into an even more commanding position in the broker-distributed market across Australasia.

And the scale jump was immediate. Based on FY13 results, the deal lifted IAG’s gross written premium base by around 18%. This wasn’t incremental. It changed the size of the platform.

Wesfarmers had been underwriting policies sold under the WFI, Lumley, and Coles Insurance brands. WFI, in particular, mattered because it operated both directly with clients and via intermediaries—giving IAG a stronger foothold in the kinds of communities where insurance is as much relationship-driven as it is product-driven.

Then there was Coles. In 2014, IAG signed a ten-year agreement to distribute home and car policies for Coles Insurance. That meant IAG’s underwriting would sit behind one of Australia’s most powerful retail brands. Coles isn’t an insurance company, but it has something insurers crave: habitual, weekly customer traffic and a name millions of Australians already trust with everyday purchases.

Wesfarmers’ decision to sell wasn’t a verdict on insurance profitability so much as a classic conglomerate choice. Wesfarmers ran supermarkets, hardware, and industrial businesses. Insurance underwriting demands specialist capability, regulatory capital, and constant management attention—resources Wesfarmers preferred to concentrate elsewhere. For IAG, a focused insurer built to compound advantage in this exact business, it was a natural buyer.

The real magic in a deal like this, though, isn’t just in headcount savings or merged back offices. IAG expected net synergies of about $140 million per year pre-tax, with a significant portion coming from reinsurance. In insurance, size doesn’t just help you spread fixed costs—it can lower the price of catastrophe protection. A bigger pool of premiums can buy reinsurance more efficiently, which matters a lot when the disasters are getting larger and more frequent.

And strategically, the deal had another consequence: it pulled IAG’s attention back home even harder. With a huge integration to execute in Australia and New Zealand, there was less room to nurture smaller, more complex positions in Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia. The path toward an eventual Asia exit was becoming clearer.

IX. The Warren Buffett Partnership (2015)

In June 2015, IAG announced a partnership that did more than move the share price. It stamped the company with a rare kind of validation: Berkshire Hathaway was investing in IAG—Warren Buffett’s first-ever investment in an Australian company.

Formally, IAG entered a strategic relationship agreement with Berkshire Hathaway Inc. It was designed as a long-term partnership, and it came with two big pillars: a 10-year quota share arrangement across IAG’s consolidated insurance business, and an equity stake in IAG via a share placement of about 3.7%.

Berkshire would acquire 89,766,607 new fully paid IAG ordinary shares at $5.57 per share, for a total consideration of $500 million. The price was set at IAG’s closing share price on Monday 15 June 2015.

Buffett didn’t bury the lead. “I’m 84 years old and this is my first investment in an Australian company,” he said. He also pointed out that this wasn’t a cold start: “We have worked with IAG for more than 15 years and over that time we’ve developed a good understanding and respect for their people, what they offer and the way they do business.”

The natural question was: why IAG? Buffett has no shortage of insurance opportunities globally. But his insurance playbook is consistent—back underwriting discipline, durable competitive advantage, and management you trust. IAG’s dominance in Australia and New Zealand, plus its partnership-driven distribution model, looked like exactly the kind of entrenched franchise Berkshire likes to partner with.

The structure mattered as much as the headline investment. Effective 1 July 2015, IAG and Berkshire entered a 10-year whole of account quota share arrangement. Berkshire would receive 20% of IAG’s consolidated gross written premium, and pay 20% of claims.

That’s what a quota share is: a fixed slice of the book, taken proportionally on both sides of the equation. Berkshire participates in the upside when underwriting is strong, and it shares the downside when catastrophes hit.

For IAG, this was a way to blunt one of its biggest structural vulnerabilities: geographic concentration. Australia and New Zealand are great businesses—until they’re both hit by the same weather system, bushfire season, or earthquake risk cycle. The quota share reduced IAG’s exposure to that concentration, lowered its future catastrophe reinsurance needs, and reduced its sensitivity to swings in reinsurance pricing.

The commercial mechanics went further than just premiums and claims. Under the arrangement, Berkshire would reimburse IAG for a portion of operating costs and pay a percentage-based fee reflecting the value it received from accessing IAG’s franchise.

The impact on IAG’s financial flexibility was substantial. The deal reduced IAG’s capital requirements by about A$700 million through 2020, including about A$400 million in 2016, and it reduced IAG’s catastrophe requirement as well. It was also expected to lift the reported insurance margin by around 200 basis points. In other words: less volatility, less trapped capital, and better economics on the same underlying machine.

And this wasn’t only about sharing risk. The partnership also included portfolio swaps that made both companies cleaner. IAG would acquire Berkshire Hathaway’s local personal and SME business lines, while Berkshire would acquire the renewal rights to IAG’s large-corporate property and liability insurance business in Australia. Each side leaned into what it wanted to be best at.

The relationship proved durable. IAG later agreed terms to renew the agreement with Berkshire Hathaway’s NICO, which represents 20% of the total 32.5% WAQS program. The renewed agreement, effective 1 January 2023, runs until 31 December 2029. Berkshire eventually chose not to renew its equity investment, allowing it to compete directly in Australia while maintaining the quota share arrangement.

X. The Asia Retreat (2018)

After the Buffett deal, IAG had a clearer answer to the question every insurer eventually has to face: where, exactly, do we have an edge?

For most of the 2010s, IAG tried to build a second growth engine outside Australasia. Asia, in particular, looked like the obvious bet: big populations, rising wealth, and insurance markets that still had plenty of room to grow. But by 2018, IAG made a defining call for its next era as a public company. It stopped trying to be a regional empire—and chose to be the dominant specialist in Australia and New Zealand.

That decision showed up not as one dramatic announcement, but as a string of exits that, together, told a very clear story.

Thailand: IAG held a 98.6% beneficial interest in Safety Insurance, based in Thailand, which traded under the Safety and NZI brands, until 2018 when it sold its holding to Tokio Marine. Vietnam: IAG owned 63.17% of AAA Assurance Corporation until 2018, when it sold its holding to Tokio Marine. Indonesia: IAG owned 80% of PT Asuransi Parolamas until 2018, when it sold its holding to Tokio Marine.

It wasn’t subtle. Position after position went to Tokio Marine—a Japanese insurer with deeper roots in Asia and a longer-term commitment to building there. IAG wasn’t “rebalancing.” It was retreating.

The UK exit followed the same logic. IAG had acquired UK insurer Equity Insurance Group years earlier, but the business never reached the scale or profitability that justified the ongoing investment. International operations were taking management time and attention, without paying back in results.

So what went wrong in Asia?

First, IAG’s advantages were intensely local. At home, it won with trusted brands, embedded distribution relationships, and hard-earned knowledge of Australian and New Zealand risk. In Asian markets, those advantages didn’t translate. IAG was just another foreign entrant, trying to buy its way into markets where incumbents already owned the relationships.

Second, the regulatory and operational complexity was heavier than expected. Each country meant a different set of rules—capital requirements, distribution structures, and local market constraints. The playbook that worked under Australian prudential regulation didn’t neatly transfer.

Third, it was simply hard to compete against local champions. Insurers in Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Indonesia understood their customers, had established channels, and often operated with cost structures IAG couldn’t match.

And then there was the cleanest argument of all: opportunity cost. Every dollar of capital and every hour of executive attention spent trying to make Asia work was a dollar and hour not spent deepening IAG’s strongest franchises—Australia and New Zealand.

In the end, the Asia retreat was less a defeat than a decision to stop forcing a strategy that didn’t fit. IAG came out of it leaner and more focused: a company designed to compound where it had true competitive advantage, not chase growth where it didn’t.

XI. COVID-19 and the Business Interruption Crisis (2020–2024)

COVID-19 broke a lot of systems at once. Supply chains snapped. City centres emptied. Entire industries went dark overnight. And for insurers, the crisis arrived with a twist that was both painfully mundane and wildly expensive: words on a page.

For IAG and other Australian insurers, the flashpoint was business interruption insurance—cover that’s meant to keep a company alive when it can’t trade. In theory, pandemic losses were typically excluded. In practice, many policies leaned on exclusion wording that referenced the Quarantine Act of 1908.

That was a problem, because the Quarantine Act had been replaced by the Biosecurity Act in 2015. Suddenly, insurers were facing the argument that an exclusion tied to an Act that no longer existed might not exclude anything at all.

Quinn Emanuel later alleged that IAG failed to adequately disclose the potential consequences of this outdated business interruption policy wording. And regardless of how the legal strategy played out, the underlying reality was brutal: what looked like a technicality had the potential to turn into massive, unexpected liability.

As court decisions clarified the risk, IAG was forced to start putting real money behind that possibility. In July 2021, it set aside $100 million. By November 2021, that provision had jumped to $865 million. The company also raised $750 million in capital to manage anticipated claims.

The speed of that change is what made it so jarring. This wasn’t an insurer waking up late to the idea that pandemics are bad. It was an insurer discovering that the lock on the door—the exclusion clause it believed was there—might not actually latch, because no one had updated a reference when the law changed.

The legal aftershocks dragged on for years. On 20 September 2024, the Federal Court delivered a judgment stating an intention to declass the representative proceeding filed against Insurance Australia Limited (IAL). At a subsequent case management hearing on 5 December 2024, the Court made orders confirming the wind-down: the class action would cease on 26 March 2025, and policyholders involved would be bound by earlier Federal Court business interruption test case rulings unless they opted out by 24 March 2025.

By late 2024, the financial picture started to shift as well. Based on actuarial assessment and subject to final board and audit review, IAG said it expected to release $200 million of the $380 million provision. The remainder reflected the risk that further valid business interruption claims could still emerge.

If there’s a single takeaway from the business interruption saga, it’s that insurance doesn’t just run on capital and actuarial models. It runs on language. A seemingly minor failure to maintain policy wording created close to a billion dollars of potential exposure, unearthed the risks lurking in legacy forms and systems, and triggered scrutiny not just from policyholders, but from investors too—through shareholder class actions alleging IAG failed to adequately disclose its BI exposure.

XII. Climate Risk and the Modern IAG (2020–Present)

If COVID exposed how expensive a few outdated words can be, climate change is exposing something even bigger: whether the basic bargain of insurance still works in a warming world.

IAG sits right at the centre of that challenge. General insurers are often the first to feel the impact of natural disasters, because they’re the ones paying the claims. That creates a paradox IAG can’t avoid: climate change is a growing threat to its profitability, but it’s also a chance to separate itself by managing risk better than anyone else.

On the “walk the talk” side, IAG has spent years tightening up its own footprint. For nearly two decades, IAG New Zealand has measured its emissions—since 2004—and it has been carbon neutral since 2012. It committed to a low-emissions future through science-based targets, and it reported it was on track to deliver a 40% reduction in emissions by 2025.

Zooming out, IAG has set the long-term goal of becoming a net zero insurer by 2050. The company says it’s working toward net zero emissions across its operations, while also strengthening climate resilience and looking for opportunities created by the broader transition.

More recently, IAG updated its interim targets: net zero scope 1 and 2 emissions by FY30 from an FY24 baseline, and a 50% reduction in limited upstream operational scope 3 emissions by FY30.

But operational emissions are the easy part of the story. The real question—the one that matters to customers, regulators, and shareholders—is whether IAG can keep insuring Australian and New Zealand homes and businesses at prices people can actually pay as weather events become more frequent and more severe.

As CEO Nick Hawkins put it, “Since 2015, the frequency of extreme weather events such as floods, storms, and bushfires in Australia has doubled.” And that trend doesn’t just damage properties. It strains communities physically and psychologically, and it threatens critical infrastructure that entire regions depend on.

So IAG has tried to push on two fronts at once: managing its own risk, and arguing that Australia can’t insure its way out of a resilience problem.

The company has been one of the loudest advocates for stronger disaster mitigation policies. After long-term lobbying by IAG and NRMA Insurance, the federal government launched the Disaster Ready Fund in 2021, committing $200 million a year to resilience projects.

That stance is central to IAG’s approach. Rather than treating high-risk areas as places to abandon—or simply slapping on massive premium increases—IAG has leaned into systemic solutions: better building codes, smarter land-use planning that keeps development out of flood plains, and community-level investment in mitigation infrastructure. It’s also enlightened self-interest. If communities get more resilient, IAG has a better chance of continuing to insure them profitably.

It’s also showing up on the ground. Since 2024, IAG reports that NRMA Insurance teams have answered more than 1.6 million calls for help, flown 43 helicopter missions to assist communities, and delivered hundreds of Red Cross EmergencyRedi workshops aimed at strengthening local resilience. And it’s starting to link resilience directly to pricing: customers who take steps to reduce risk—like bushfire-proofing their homes—can now qualify for premium benefits under new initiatives.

That last move is the most revealing. Instead of only pricing climate risk as a penalty, IAG is trying to price adaptation as a reward. It’s a subtle shift in incentives, and it hints at what the next era of insurance might look like: not just paying for disasters after they happen, but actively reshaping behaviour so fewer disasters become total losses in the first place.

XIII. The Modern IAG: FY25 Results and Strategic Outlook

By FY25, the story of IAG wasn’t just survival. It was execution.

When the company announced its full-year 2025 results, the headline was simple: profit jumped. Net profit after tax came in at $1,359 million, up from $898 million the year before. The drivers were the ones you’d expect from an insurer that had spent the last decade professionalising its machine: higher net earned premiums, stronger insurance profit, and solid investment income on shareholder funds.

On the underwriting side, IAG delivered an insurance profit of $1,743 million, up from $1,438 million, translating into a reported insurance margin of 17.5%—higher than the prior year’s 15.6%. Gross written premium rose to $17,106 million, up from $16,400 million, and net earned premium reached $9,984 million, up 8%.

A big part of what made FY25 pop was that the year’s natural peril costs came in below budget—$1,088 million, or $195 million under allowance—at a time when “below allowance” is never something you want to assume. Layer on disciplined pricing, and the result was IAG’s highest insurance margin to date.

Shareholders felt it too. IAG declared a final dividend of 19 cents per share with 40% franking, up from the prior year. For the full year, dividends totalled 31 cents per share, also higher than FY24.

IAG framed the result as the payoff from a multi-year transformation: millions of policies migrated onto a modern Enterprise Platform, tighter underwriting discipline, and a business that—at least in FY25—didn’t have to absorb the full force of what had become a harsher natural peril baseline.

That “transformation-first” posture is closely tied to the leader who took the wheel at the height of the pandemic. Nick Hawkins became IAG’s Managing Director and CEO on 2 November 2020. Before that, he was Deputy CEO, after spending 12 years as CFO. He’d also been CEO of IAG New Zealand. Before joining IAG, he spent a decade at KPMG in financial services across Perth, London, and Sydney. He’s a fellow of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Australia and New Zealand, a Harvard Advanced Management Program graduate, and holds a Bachelor of Commerce from the University of Western Australia.

In other words, he’s not a headline-chasing dealmaker by instinct. Hawkins’ background—chartered accountant, long-time CFO—shows up in a leadership style built around financial discipline and operational delivery.

And then, in late 2024 and 2025, IAG made two moves that were very “IAG”: big, partnership-based acquisitions that deepen distribution in its home markets rather than chasing new geographies.

First came Queensland. IAG and RACQ announced a 25-year exclusive strategic alliance to provide RACQ general insurance products and services for RACQ members and Queenslanders. Under the deal, IAG would acquire 90% of RACQ’s existing insurance underwriting business, with an option to acquire the remaining 10% in two years. The consideration was $855 million, comprising net tangible asset value plus entry into the long-term exclusive distribution agreement. IAG completed the acquisition in September 2025, formally kicking off the alliance.

Then Western Australia. In May 2025, IAG agreed to acquire the insurance operations of the Royal Automobile Club of Western Australia (RAC). The $1.35 billion deal included $400 million to acquire all RAC shares, plus a $950 million initial payment to secure an exclusive 20-year distribution and brand licensing agreement for insurance products under the RAC brand.

IAG’s own summary of the two deals was explicit about the ambition: “When completed, the combination of these strategic alliances is expected to add around $3 billion in GWP, increase insurance profit by at least $300 million, and deliver double-digit earnings per share accretion on a full synergy run-rate basis. This results in an improved return on equity target of 15% on a ‘through the cycle’ basis.”

Strategically, the point wasn’t novelty. It was repetition—scaling the model that had worked for decades. Just as IAG had partnered with RACV in Victoria, it was now locking in RACQ in Queensland and RAC in Western Australia. The motoring clubs keep the brands and the member relationships; IAG brings the underwriting, the technology platform, reinsurance access, and the claims engine.

In a business where trust is local and risk is increasingly global, it’s a very IAG answer: own the machinery, rent the front door, and lock in the distribution for a generation.

XIV. Bull Case, Bear Case, and Competitive Analysis

The Bull Case

The bullish argument for IAG isn’t that it has some secret product nobody else can copy. It’s that it sits on a set of advantages that are surprisingly hard to dislodge—advantages that Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework would recognise as durable.

Brand Power: NRMA, RACV, RACQ, and RAC aren’t just logos on a policy schedule. For a lot of Australians, these names feel like institutions—membership organisations that have literally shown up on the side of the road, helped after storms, and been present in stressful, high-emotion moments. That kind of trust doesn’t just drive retention. It supports pricing power, because when things go wrong, customers care about who will actually pick up the phone and pay the claim.

Counter-positioning: IAG’s most effective distribution channel is also its hardest to replicate: long-term partnerships with the automobile clubs. For a competitor to copy this, it would need to convince the same clubs—already locked into exclusive, multi-decade alliances—to switch. Or it would need to build a competing member organisation from scratch. Both options are slow, expensive, and uncertain, which is exactly what makes the position defensible.

Scale Economies: At IAG’s size, scale is not just about overhead. It’s a lever in the most important “supplier” market insurers face: reinsurance. With a premium base around the $17 billion mark, IAG can buy catastrophe protection more efficiently than smaller players. The Berkshire Hathaway quota share is a vivid example of how scale can attract unusually favourable partnership terms—and how those terms, in turn, reduce volatility and free up capital.

Bulls also point to execution. IAG has been migrating onto its Enterprise Platform, modernising how it prices risk and runs claims. The basic promise is leverage: if you can automate and standardise more of the work, every additional policy you write becomes more profitable.

On top of that, IAG has highlighted AI-driven improvements in claims—reporting that it can resolve a large share of claims in real time and materially reduce claims handling costs. If those benefits hold, they don’t just save money in one year; they permanently change the cost curve.

The Bear Case

The bearish argument is simpler: insurance looks stable until it isn’t. And IAG is exposed to a few risks that can overwhelm even a well-run machine.

Climate Exposure: IAG is concentrated in Australia and New Zealand—two markets where natural perils are becoming more frequent and more severe. Reinsurance and improved modelling help, but they don’t eliminate the core problem. If premiums have to keep rising to match risk, more households may reduce cover or drop it altogether. That’s the nightmare scenario for a general insurer: affordability pressures turning into a shrinking market.

Regulatory Risk: This is a heavily regulated industry, and regulation is only getting more complex—especially around disclosure, fairness, and climate-related affordability. The business interruption episode showed how quickly a technical issue in policy wording can become a major liability and a public scrutiny event. The bear case assumes there will be more of these surprises.

Competition from Digital Insurgents: IAG’s advantages are real, but so is the steady pressure from digital-first competitors. Lower-cost operating models, slicker customer experiences, and new distribution formats—embedded insurance, pay-per-use, parametric products—could chip away at traditional insurer economics, especially in personal lines where customer loyalty can be thin.

Customer Switching: Even with high renewal rates, insurance is easy to compare and easy to switch, particularly as comparison sites and digital channels make price differences more visible. If the market trains customers to shop purely on premium, brand trust matters less—and IAG’s moat narrows.

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate. Regulation and capital requirements remain meaningful barriers, but digital distribution makes it cheaper to get to customers. Newer entrants have won pockets of share in certain product niches, but the incumbents still dominate the mainstream.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate. Reinsurers tend to gain leverage after big catastrophe years, when prices rise and capacity tightens. IAG’s scale—and partnerships like Berkshire—offer some insulation, but they don’t remove exposure to the global reinsurance cycle.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Moderate to high. Individual consumers have limited negotiating power, but they can switch. In commercial lines, large clients and brokers have more leverage, and the market is more explicitly price-and-service competitive.

Threat of Substitutes: Low to moderate. Large corporates can self-insure at the margin, and government-backed schemes (such as New Zealand’s Earthquake Commission) can replace parts of private coverage. But for most households and small businesses, there’s no true substitute for general insurance.

Industry Rivalry: High. Australia’s general insurance market is mature and intensely competitive. Major rivals like Suncorp and QBE are well-resourced and aggressive, and competition shows up quickly in pricing, service levels, and distribution partnerships.

XV. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you’re tracking IAG as a long-term, fundamentals-driven investor, there are three numbers that quietly tell you most of what you need to know. Not because they’re perfect, but because they sit at the centre of the whole machine: underwriting discipline, franchise momentum, and catastrophe reality.

1. Insurance Margin (Reported)

Insurance margin—insurance profit divided by net earned premium—is the cleanest read on whether IAG is actually making money from insurance, before the story gets complicated by one-off noise. It bundles together pricing, claims, and operating efficiency in a single measure.

In FY25, IAG’s insurance profit translated into a reported margin of 17.5%. Management’s stated target is 15% “through the cycle,” a deliberate reminder that an insurer’s best years and worst years can look wildly different depending on natural perils and other shocks.

The thing to watch is whether the margin starts slipping for structural reasons. Competitive discounting, rising claims inflation, or repeated catastrophe hits can all compress margins. Sustained performance below 13% would be a meaningful warning sign that pricing power and/or risk selection is weakening.

2. Gross Written Premium (GWP) Growth

GWP is the top-line signal: is IAG writing more business, or is it being outcompeted? But it’s also a deceptive number, because growth can come from three very different sources: higher prices, higher volumes (more policies), or acquisitions.

The RACQI acquisition was expected to complete on 1 September 2025, and IAG expected that to lift GWP growth to around 10%.

For investors, the key is to break that growth apart. Price-led growth can look good until it drives churn. Volume-led growth is often higher quality, but harder to achieve in a mature market. And acquisition-led growth only counts if integration is executed well and the economics hold up after the deal dust settles.

3. Natural Perils Costs Relative to Allowance

Natural perils are where an insurer’s nice, smooth spreadsheet meets the real world. IAG sets an annual allowance for natural peril costs, and the gap between actual costs and that allowance can swing the year’s reported result dramatically.

In FY25, IAG’s natural perils costs were $1,088 million, which was $195 million below allowance—an important tailwind behind the year’s strong profitability.

Over time, this KPI becomes less about any single year and more about the pattern. If the allowance keeps rising, it’s IAG effectively saying: we think the climate-adjusted “normal” is getting worse. If results are consistently better than allowance, budgeting may be conservative. If they’re consistently worse, it can be a sign the risk environment is outrunning the models—or that pricing and protection need to adjust faster.

XVI. Conclusion: A Century of Helping Australians

As NRMA Insurance marks 100 years since it first offered cover in 1925, it’s worth stepping back and seeing what that simple idea became.

It started as a motoring association doing something practical for its members: helping early Australian drivers deal with the financial aftermath of crashes, theft, and the everyday chaos of roads that were still being built. Over time, that promise expanded from cars to homes, from one state to a continent, and then across the Tasman.

Today, that original NRMA insurance arm sits inside Insurance Australia Group: the dominant general insurer across Australia and New Zealand, a company Warren Buffett chose as his first-ever Australian investment, and a business now operating on the front lines of climate risk.

The reasons IAG got here—and stayed here—are also the reasons it’s hard to copy. The house of brands protects something fragile and valuable: local trust, accumulated over generations. The long-term partnerships with automobile clubs create distribution that isn’t just effective, but defensible. And the scale built through patient compounding and disciplined acquisitions buys real advantages in reinsurance and capital efficiency that smaller insurers simply can’t access on the same terms.

But the next century won’t be a victory lap. Climate risk is intensifying. Customer behaviour is shifting as digital distribution gets sharper and faster. Regulators are watching more closely. And the business interruption saga proved a humbling truth: in insurance, tiny technical details—like outdated wording—can turn into enormous liabilities.

So IAG sits in a familiar insurance tension: a mature, essential franchise with real structural strengths, operating in a world where the underlying risk is changing. For long-term investors, that’s the bet. Not that shocks won’t happen, but that IAG can keep pricing them, managing them, and adapting through them—like it has through demutualisation, takeover pressure, earthquakes, pandemics, and regulatory battles.

The company that began by helping motorists on the dusty roads of 1920s Australia now helps millions of families protect their homes, their cars, and their livelihoods across Australia and New Zealand. And the core mission is unchanged: be there when people need help most.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music