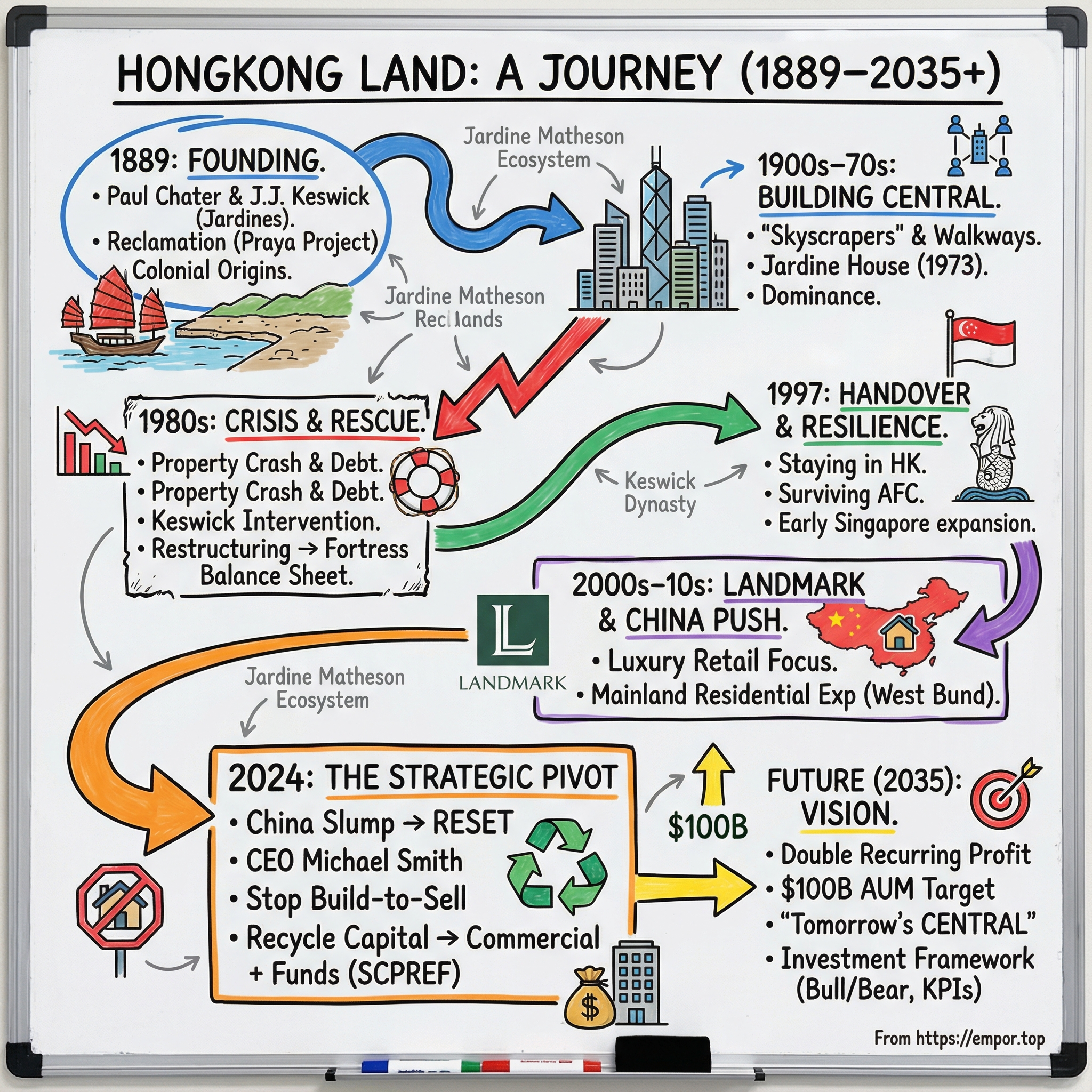

Hongkong Land Holdings: The Story of Asia's Premier Landlord

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture Central, Hong Kong on a humid evening in 2024. The sun drops behind Victoria Peak and the skyline lights up — glass towers, marble lobbies, and storefronts that look more like galleries than shops. In a small patch of streets near the waterfront sits some of the most valuable commercial real estate on the planet. And an outsized share of it traces back to one landlord: Hongkong Land.

In Central, Hongkong Land is the dominant player. Across Asia, it owns and manages roughly 850,000 square meters of premium office and luxury retail space, concentrated in a handful of gateway cities.

But this isn’t really a story about square meters. It’s a story about power — the slow, compounding kind that comes from owning the most irreplaceable addresses in the region, then surviving long enough to keep them. It’s about how a clerk from Calcutta teamed up with a Scottish trading dynasty with opium in its origin story to build a property empire that outlived the colonial era that created it. And it’s about how that empire kept going through property crashes, takeover threats, and geopolitical regime change.

Because the central question is almost too cinematic to be true: how does a company born from colonial land reclamation in 1889 make it through the 1997 handover, multiple market collapses, a defensive maneuver that nearly sank it, and then — 135 years in — decide to pivot away from China right as its model is under pressure?

Structurally, Hongkong Land is a public company listed in Hong Kong and Singapore. Strategically, it sits inside one of the most famous corporate families in Asia: it’s 53% owned by Jardine Matheson, controlled by the Keswick family — descendants of co-founder William Jardine’s older sister, Jean Johnstone.

That Jardines link matters. Jardine Matheson is Hong Kong–based, Bermuda–domiciled, British–founded, and still one of the great Asian conglomerates: listed primarily in London, with secondary listings in Singapore and Bermuda, and with major businesses across the region. Its portfolio includes Hongkong Land, DFI Retail Group, Mandarin Oriental, Jardine Cycle & Carriage, Astra International, and more.

As we go, a few big themes keep resurfacing: the craft of owning “can’t replicate” real estate, the reality of geopolitics for companies rooted in place, the quiet mechanics of dynasty control, and the modern question hanging over every trophy asset — does location still command the same premium in the twenty-first century?

All of that brings us to the present. In October 2024, Hongkong Land announced its most significant strategic shift in decades: it would stop doing build-to-sell residential development, double down on commercial property management, and ultimately move assets into real estate investment trusts and other capital vehicles. The timing was not an accident — it came as the property downturn in mainland China and Hong Kong was bruising the entire sector.

To understand why this pivot was necessary — and what it says about the future of prime city-center real estate in Asia — we have to go back to the beginning. Back before the towers, before the bridges, before Central looked like Central. To a young Armenian orphan arriving in Hong Kong with almost nothing, except ambition and an instinct for where money was about to flow.

II. The Colonial Origins: Opium, Reclamation & The Birth of Central

The story begins not in Hong Kong, but in Calcutta — with a seven-year-old orphan who would grow up to redraw the coastline of a city.

Catchick Paul Chater was born in Calcutta, British India, into an Armenian family. His father worked in the Indian civil service. When Chater was orphaned at seven, he won a scholarship to La Martiniere College — the kind of break that changes the trajectory of a life. In 1864, as a teenager, he sailed to Hong Kong and moved in with his sister Anna and her husband, Jordan Paul Jordan. He took a job as an assistant at the Bank of Hindustan, China and Japan.

That could have been the whole story: a modest colonial career, stable pay, respectable title. But Chater had a rare kind of instinct — the ability to look at a place and see what it could become.

With backing from the Sassoon family, he left the bank to strike out as an exchange broker. He traded gold bullion. He traded land. And in one of the most telling images of his early life, he spent nights taking sea-bed soundings in Victoria Harbour from a sampan — literally measuring the depths, mapping the future, figuring out where water could become land.

He partnered with Sir Hormusjee Naorojee Mody in 1868 to form Chater & Mody, and the business took off. By 1870, Chater was buying property of his own; that year he leased his first piece of land to the Victoria Club. Over the next decade, he developed sites right in the island’s core commercial district — the dense strip between the harbour and the slope up to the Peak. It’s hard to stand in Central today, amid its tight grid of towers and crowds, and remember that so much of the platform beneath it had to be imagined first. Chater became so influential that he was later described as “one of the most powerful and beneficent figures in the Empire.”

By the 1880s, he was everywhere. He helped found or shape some of the institutions that became the city’s operating system: Hong Kong and Kowloon Wharf and Godown (1884), Dairy Farm (1886), Hongkong Land (1889), Hongkong Electric (1889), the Star Ferry (1898), and Hongkong Telephone (1924). He also held substantial stakes in companies like the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, Hong Kong & Shanghai Hotels, Hongkong Tramways, and the Hong Kong and Whampoa Dock Company. He was among the first to see what Kowloon could become after it was newly acquired.

But Chater’s real superpower wasn’t simply making deals. It was understanding Hong Kong’s fundamental constraint: land. A mountainous island city with limited flat ground creates a permanent scarcity premium. And if you can’t find more land… you make it.

In 1887, Chater began pursuing what became the Praya Reclamation Project in Central — a major effort that would ultimately underpin some of Hong Kong Island’s most prestigious real estate, including the site where the Mandarin Oriental would later stand. To push it through, he bypassed the local governor, Sir William Des Voeux, and went straight to London to negotiate with the Colonial Office. And to turn that ambition into a corporate vehicle, The Hongkong Land Investment and Agency Company was incorporated in March 1889.

To make it work, Chater needed more than engineering and vision. He needed a partner with deep capital, influence, and staying power. So he brought in James Johnstone Keswick of Jardine Matheson. Chater and J.J. Keswick became permanent joint managing directors. The founding pairing mattered: Chater brought the land thesis; Keswick brought the dynasty.

Jardine Matheson wasn’t just any trading house. By the late nineteenth century it was one of the defining commercial powers in Asia — rooted in the early Hong Kong “hong” system, and shaped by the region’s most controversial trade flows. After the cession of Hong Kong under the 1842 Treaty of Nanking, Jardine, Matheson & Company established its headquarters on the island and expanded rapidly, including smuggling illegal opium from British-controlled India into China. It has even been described as the “most successful opium smuggling company in the world.” The firm’s leadership and ownership became intertwined with the Keswick family: descendants of William Jardine’s sister Jean, through the marriage of her daughter to Thomas Keswick.

J.J. Keswick himself arrived in the Far East in 1870 and spent the next 26 years mostly based in Hong Kong. He was deeply embedded in the colony’s power structure — a member of the legislative council, a multi-term chairman of the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce, and a taipan of Jardine Matheson from the 1890s into the early twentieth century. He was also Sir Harry Smith Parkes’ son-in-law. And he co-founded Hongkong Land with Chater in 1889, cementing the relationship between the property company and Jardines that would endure for generations.

Then came the physical act of creation.

Chater returned to London to secure government approval, and in 1890 the foundation stone was laid by the Duke of Connaught. Completed in 1904, the reclamation ran along the waterfront of Central and the Western districts — roughly 75 metres wide and more than 3 kilometres long. Previous reclamation work had been piecemeal, done lot by lot, leaving the foreshore chaotic and disrupting the natural flow of water. Chater’s solution was a coordinated plan under government control: marine lot-holders could extend their lots to the new shoreline at their own expense, then rent the newly formed land from the government. It was a political and commercial compromise that turned dissent into momentum.

And once it was done, it changed everything. The core of Hongkong Land’s prime portfolio still sits on land created by Chater’s reclamation vision.

Decades later, the city would keep his name alive in public rituals — like the Hong Kong Jockey Club’s “Chater Cup,” established in 1955 — and in memorials like the South China Morning Post’s 1926 tribute, which captured his dual legacy: “he gave Hong Kong its bones and its beauty.”

The partnership Chater built with Keswick created Hongkong Land’s enduring template: patient capital, premium locations, and value created through infrastructure and city-shaping projects — not quick speculation. In a place like Hong Kong, whoever controls the reclaimed waterfront controls the commercial future.

That relationship with Jardine Matheson would become both blessing and burden: it brought capital, clout, and continuity — and, eventually, governance complexity that would echo through the next century.

III. Building the Crown Jewels: A Century of Central Dominance (1889–1970)

With the Praya Reclamation Project reshaping the waterfront, Hongkong Land started doing what it would do better than anyone else for the next century: quietly assembling the addresses that would become the economic command center of Hong Kong.

Its earliest trophy was the New Oriental Building, a four-storey commercial block completed in 1898 on Marine Lot 278 at No. 2 Connaught Road — brand-new frontage on brand-new land. It didn’t last forever. The building was demolished in the early 1960s, and the site is now occupied by AIA Central. But as a starting gun for what Central would become, it was perfect: a proof that reclaimed shoreline could turn into the city’s most valuable strip.

Then the pace accelerated. In the short window between mid-1904 and the end of 1905, five major buildings went up on the reclamation — the first generation of what Hong Kong would call “skyscrapers.” One of them was Alexandra Building, completed in 1904 on the site where today’s Alexandra House stands. By 1941, Hongkong Land already held 13 properties in Central. The company wasn’t just building on the new coastline; it was effectively helping define the district itself.

Through these formative decades, Paul Chater’s fingerprints were on everything. After J.J. Keswick retired in 1896, Chater continued first as joint managing director and then, effectively, as the singular guiding force until his death in 1926. His edge wasn’t merely operational competence. It was his instinct for what Hong Kong could become — and his willingness to plan for it years, even decades, before the rest of the market caught up.

That long horizon wasn’t always popular.

At the company’s first annual general meeting in January 1890, shareholders learned that Hongkong Land had made a net profit of $117,000 in its first nine months and declared a 7 percent dividend on paid-up capital. Instead of celebration, there was frustration. Some investors had expected a get-rich-quick scheme and had borrowed heavily to buy in, assuming the new company would immediately spin off outsized returns. To make matters worse, a meaningful portion of the company’s capital hadn’t been deployed yet, even after early property purchases. Tempers flared, criticism landed on Chater’s outside business interests, and he even offered to resign. The board refused.

The real issue was philosophical: shareholders wanted speed; Chater was building for control. He was aiming for steady, deliberate growth — the kind that doesn’t look exciting in month nine, but becomes almost impossible to dislodge by decade four. That choice became Hongkong Land’s DNA.

The next great test came with the Second World War. The company effectively ceased business for three years and eight months. When it recovered its office buildings in September 1945, they were still structurally sound — and Hongkong Land went right back to work.

Post-war Central needed modern space. In 1947, the company added three floors to the five-storey Marina House. It redeveloped 11 and 13 Queen’s Road Central into the nine-storey Edinburgh House, completed in 1950, on the sites of what are now Edinburgh Tower and York House. On a prime triangular site bounded by Des Voeux Road, Chater Road, and Ice House Street, three older buildings — Alexandra Building, Royal Building, and Chung Tin Building — were demolished and replaced by the 13-storey Alexandra House.

By the mid-1960s, the portfolio had become a self-reinforcing cluster: nine office blocks in Central, plus the shopping complex at Prince’s Building and The Mandarin Hotel. And Hongkong Land began leaning into something that would become one of its most distinctive advantages — connecting its properties into a single, walkable system. Through pedestrian bridges, tenants and shoppers could move between buildings without ever stepping into the heat, rain, or street-level congestion. In subtropical Hong Kong, that wasn’t a nice-to-have. It was a moat.

Then, in 1970, Hongkong Land made a statement that it intended to remain the landlord of Central for the modern era too. On June 1, it paid a then world-record price of HK$258 million at public auction for a key Central reclamation site. The resulting building — completed in 1973 as a 52-level, 696,000 square foot tower — became Hong Kong’s largest and most advanced office block. It would later be renamed Jardine House.

By the late 1970s, the pattern was unmistakable: premium sites, patient capital, and an interlinked fortress of commercial space that made Hongkong Land feel less like a developer and more like a piece of the city’s infrastructure.

Which is exactly why what happened next was so shocking. The company looked unassailable — and that sense of invincibility would help set up the near-death experience to come.

IV. The 1980s Crisis: Near-Death Experience & The Keswick Rescue

The early 1980s brought Hongkong Land to the edge of collapse — a reminder that even the most dominant landlord can get fragile fast when leverage meets a turning market.

On the surface, Hong Kong had just come off a property boom in 1980 and 1981. Underneath, the world economy was weakening, unemployment was high, and by early 1982 confidence started to crack. Prices fell. Buyers hesitated. Purchasing power dried up. The market turned depressed — and it turned quickly.

Hongkong Land’s first instinct was to spread its risk. In 1982 it moved beyond its traditional property focus and bought large stakes in Hong Kong Telephone and Hongkong Electric. But at the same time, the company made the most consequential property bet of the era: it acquired the last major site available in Core Central, near Connaught Centre, and began work on Exchange Square — the largest commercial development the colony had ever seen. (The purchase price was HK$4.7 billion, not million.)

It was a classic Hongkong Land move: secure the irreplaceable site, build something that defines the next generation of Central.

It was also disastrously timed.

Exchange Square required heavy borrowing. When the property market then crashed in 1983, and demand for large residential units and prime office space slumped into a broader recession in 1984, Hongkong Land suddenly found itself exposed. The company reorganized to reduce its borrowing, but the damage was already visible in one brutal metric: in 1984, gearing — borrowing relative to shareholders’ funds — stood at 103 percent.

In other words, Hongkong Land owed more than the equity value of the company. And it was carrying that load precisely as property values were falling and rental income was under pressure. The company that looked unassailable in Central was, financially, close to insolvency.

Then the situation got even worse, because the crisis wasn’t only in property. It was also corporate and political.

At the Jardine Matheson level, Chinese tycoons had begun circling. Jardines looked vulnerable, and in Hong Kong, vulnerability attracts predators. In early November, David Newbigging announced a defensive move: Jardine Matheson and Hongkong Land would increase their stakes in each other so no outsider could gain control of either company. The idea was simple — make the shareholding structure so tangled that a takeover becomes impossible.

The execution was expensive. The cross-ownership scheme loaded both companies with debt, forcing asset sales just to raise cash. Jardine Matheson sold its interest in Reunion Properties. Newbigging drew criticism for being overly conservative and too focused on Hong Kong and the region. The pressure campaign to remove him built, and no one pushed harder than John Keswick. In June 1983, Newbigging stepped down as senior managing director, keeping only the chairman title. The taipan role passed to 40-year-old Simon Keswick — a choice that initially unsettled investors, because Simon had yet to prove he could run a sprawling, embattled empire.

He proved it fast.

Once in control, Simon moved to de-lever, simplify, and stabilize. He raised cash by selling Jardine Matheson’s majority stake in Rennies Consolidated Holdings, a South African hotel, travel, and industries group, for $180.1 million. He reorganized management into a decentralized system split between a Hong Kong and China division and an international division. In early 1984, he replaced Newbigging as chairman. And on March 28, with Hong Kong’s future being negotiated between Britain and China, he made a decision designed to protect the group’s corporate footing: Jardine Matheson would create a new holding company, Jardine Matheson Holdings, incorporated in Bermuda.

This was the Keswick playbook in full: preserve control, reduce existential risk, and make the organization harder to attack — financially and politically.

For Hongkong Land, the rescue was just as direct. The company sold most of its overseas properties and non-core investments, including its stakes in Hong Kong Telephone and Hongkong Electric. It demerged Dairy Farm in 1986 and Mandarin Oriental in 1987. It sold off its residential portfolio in 1986, then sold Harcourt House and Windsor House a year later.

The result was an extraordinary reversal. By the end of 1986, gearing had fallen to a manageable 31 percent without materially shrinking the company’s position in Core Central. By 1987, gearing fell again — down to just 6 percent of shareholders’ funds.

Hongkong Land had gone from overleveraged to fortress-balance-sheet in roughly three years, largely by selling everything that wasn’t the crown jewels.

And then, almost as if the city wanted to underline the lesson, Exchange Square started to pay off.

Towers One and Two opened in 1985. Tower Three followed in 1988. As the complex filled out, office rentals there rose sharply, reaching roughly three times their 1985 level. The project that had nearly bankrupted the company became one of its defining assets — proof that concentrating on premium Central locations could be both terrifying in the downturn and hugely rewarding on the other side.

But the escape came with a lasting tradeoff. The cross-shareholding and control mechanisms built to fend off takeovers and stabilize the group also created a governance structure that would draw criticism for decades. Hongkong Land survived. Jardines survived. And the Keswicks tightened their grip.

Which set the stage for the next, bigger question: if the 1980s were about surviving a market collapse, the 1990s would be about surviving a regime change.

V. The 1997 Question: Fleeing Hong Kong or Doubling Down?

By the early 1990s, Hongkong Land had survived its near-death experience and rebuilt a fortress balance sheet. But Hong Kong itself was heading toward an event no landlord could diversify away from: the 1997 handover to China.

For Hongkong Land, the question was existential in the simplest possible way. Do you treat Hong Kong as a melting ice cube and sell down risk? Or do you lean in even harder to Central — the very asset base that only works if the city stays open, liquid, and globally trusted?

In 1989, Hongkong Land Holdings Limited was incorporated in Bermuda, and The Hongkong Land Company became a wholly owned subsidiary. It was a hedge: a legal and corporate layer of separation from whatever might follow the handover. At the same time, Hongkong Land entered the last decade of the century in strong financial shape, even as the city’s talent and capital showed signs of leakage — a steady draining off of people and resources as families and firms planned for worst-case scenarios.

The move wasn’t isolated. With the agreement to return Hong Kong to Chinese oversight now signed, the wider Jardine Matheson group took the drastic step of shifting incorporation to Bermuda too. It was defensive, but it was also very Jardines: when the ground under you might change, you make sure the legal foundation of your empire sits somewhere else.

Then there was the other defense — the one aimed not at geopolitics, but at takeovers.

The Keswicks had spent decades building control mechanisms that made Jardines, and by extension Hongkong Land, extremely difficult to capture. Critics argued the structure entrenched family control at minority shareholders’ expense. By the mid-1980s, Jardines had assembled a shareholding system that allowed the Keswick family — distant relatives of co-founder William Jardine — to control the group while owning only a small percentage of Jardine Matheson Holdings.

So Hongkong Land hedged offshore, locked down control at home, and then did something that surprises people who expect corporations to flee uncertainty.

It kept building.

Through the 1990s, Hongkong Land continued upgrading its core Central office portfolio while starting to look more seriously at other Asian cities. In Hong Kong, Central office supply expanded substantially in the late 1990s. In 1997, the company launched the redevelopment of Swire House into what became Chater House — positioned as a world-class building in the heart of Central.

And it began laying a second anchor in Singapore. There, Hongkong Land started construction on One Raffles Link, an office building in the city center and an early example of sustainable construction. The building was completed in 2000.

Then the region got its stress test.

The Asian Financial Crisis hit in 1997–98, and Hong Kong’s property market took it on the chin. From 1997 to 2003, residential property prices fell by 61%. It was a brutal reminder that even the most supply-constrained market can reprice fast when confidence breaks.

But Hongkong Land’s posture was different this time. The conservative leverage it had rebuilt after the 1980s restructuring proved prescient. And while the wider market convulsed, the Central portfolio showed why it was the crown jewel: prime office space in the financial district maintained occupancy that helped cushion the blow.

Then came the handover itself. And, at least in the immediate aftermath, the nightmare scenarios didn’t arrive. Beijing maintained the “one country, two systems” framework. Foreign capital kept flowing through Hong Kong. The feared instant collapse — the mass exodus, the sudden freezing of commerce — didn’t materialize.

Hongkong Land’s bet on Hong Kong had worked. But the company’s leadership also understood the deeper lesson: concentration risk doesn’t disappear just because you survived the first test. The seeds of diversification planted in the 1990s — especially in Singapore — were about to become much more than a side project.

VI. The 2000s–2010s: Luxury Retail Pivot & Southeast Asian Expansion

The early 2000s marked a quiet but decisive shift for Hongkong Land. It wasn’t just going to be the landlord of Central’s best office towers. It was going to curate the neighborhood itself — offices above, luxury below, and a seamless, weatherproof experience connecting it all.

The work started with the crown jewels. In 2003, the redevelopment of Swire House into the new Chater House was completed. Prince’s Building was substantially renovated. The Landmark was redeveloped too, with the Landmark Mandarin Oriental Hotel and York House added. Even Exchange Square got its upgrade: The Forum, its retail block, was redeveloped into a five-storey office building, wholly leased to Standard Chartered Hong Kong.

Then, in early 2012, Hongkong Land put a name and a narrative around what it had been building: “LANDMARK.” The brand covered its four flagship shopping destinations — The Landmark, Alexandra House, Chater House, and Prince’s Building — stitched together by pedestrian bridges as part of the Central Elevated Walkway. It launched with a new “L” logo meant to stand for LANDMARK and luxury retail.

This wasn’t marketing for marketing’s sake. It was an admission of where retail was headed. If e-commerce could deliver products, physical spaces had to deliver something else: an experience. By concentrating the world’s leading luxury brands inside a tightly connected cluster of premium buildings — where you could move from store to store without touching the street — Hongkong Land made LANDMARK feel less like “shops in Central” and more like a destination with its own gravity.

By this point, the company’s footprint had become both deep and deliberately narrow. In Central Hong Kong, its portfolio represented about 450,000 square meters of prime property. In Singapore, it had roughly 165,000 square meters of office space, mainly through joint ventures. It owned five retail centers on the Chinese mainland, including one at Wangfujing in Beijing, and it held an interest in an office complex in Central Jakarta. On top of that were residential, commercial, and mixed-use projects under development across China and Southeast Asia — including a mixed-use project at West Bund, Shanghai.

Through the 2010s, that geographic expansion accelerated. In Singapore, Hongkong Land built meaningful positions in Marina Bay Financial Centre and One Raffles Quay through joint ventures. In mainland China, it expanded retail and leaned harder into residential development — the line of business that would later come back to haunt it.

And despite a common perception that the firm avoided mainland China in favor of Southeast Asia, the reality was more complicated. Its subsidiary, Hongkong Land, spent 4.4 billion dollars buying a plot of land in Shanghai — a move that analyst Jonathan Galligan of CLSA read as a clear signal of commitment to the mainland. Bloomberg’s informal calculations suggested that by 2019, mainland business ventures were the company’s third-largest profit contributor at $255.4 million. And by 2021, the company’s annual report stated that 55% of its profits came from China, compared with 42% from Southeast Asia and 3% from the rest of the world.

That China push would become the most consequential strategic choice of the decade — producing strong results for years, and then turning into a major drag just as the cycle finally broke.

VII. Key Inflection Point: The China Residential Gamble (2010s–2024)

At the time, the pivot into mainland China residential development looked like the obvious next move. China’s middle class was expanding, urbanization was relentless, and Hongkong Land had spent a century proving it knew how to build “premium” in dense Asian city centers. The assumption was that the brand, the design standards, and the execution discipline that worked in Central could travel across the border.

The flagship for that ambition was Shanghai’s West Bund Financial Hub — an approximately $8 billion bet on creating a new, modern version of what Hongkong Land had built in Hong Kong: a dense, integrated, high-end district where offices, retail, hospitality, and residences reinforce each other.

The plan was huge. The West Bund site covered about 1.1 million square meters of development area — including Grade A offices, luxury retail, high-end waterfront residential units, plus a hotel and broader convention and cultural facilities. A public art center designed by Thomas Heatherwick, the West Bund Orbit, was part of the vision, along with LEED- and WELL-certified office buildings and “Central,” the project’s premium lifestyle retail concept.

It was, by scale, a statement. This became Hongkong Land’s single largest investment ever — a portfolio described as more than double the total size of its 12 prime buildings in Hong Kong’s Central. Delivery was set across three phases, with offices, most of the luxury retail, and a luxury hotel targeted for completion by 2027.

And then the cycle turned.

Just as Hongkong Land was leaning harder into China, the mainland property market began a long, grinding decline. What started as a crisis among heavily indebted developers — Evergrande became the symbol — spread across the sector. Confidence weakened, transactions slowed, and even developers focused on more affluent buyers weren’t immune.

The numbers started to tell the story. Hongkong Land’s net loss widened 150% in the first half of the year on lower sales of projects in mainland China, while the slump in Hong Kong’s office and retail markets added pressure on rental income. For the half year ended 30 June, the company booked an attributable loss of $833 million, more than double the shortfall from the same period a year earlier. Its development properties segment — residential and mixed-use projects across mainland China and Southeast Asia — swung to an operating loss of $260 million, after annual losses in three of the past four years.

By year-end, the damage was still visible. Hongkong Land reported that underlying profit fell 44% to US$410 million for the year ended December 31, 2024, driven by non-cash provisions tied to its Chinese mainland build-to-sell business. Excluding those provisions, underlying profit would have been down 12% to US$724 million.

This is the cruel irony of the China expansion: it was supposed to reduce dependence on Hong Kong, but it introduced a different kind of concentration risk — exposure to a property downturn on the mainland that didn’t look like it was ending anytime soon.

And it forced a fundamental rethink. Did Hongkong Land want to keep running a build-to-sell residential engine — high potential in good times, capital-hungry and painful when the market turns? Or did it want to double down on what it had always been best at: recurring rental income from premium commercial properties?

The company’s answer arrived in October 2024.

VIII. Key Inflection Point: The 2024 Strategic Reset

On October 29, 2024, Hongkong Land announced the biggest strategic shift in its 135-year history — a decision that amounted to saying, out loud, what the numbers had been implying for years: the build-to-sell residential model was no longer worth the volatility.

The company laid out a ten-year plan designed to double recurring profit by 2035 and unlock up to $10 billion of capital. The mechanism was straightforward, if sweeping: stop allocating fresh capital to build-to-sell residential development, recycle out of that portfolio, and redeploy into premium, income-producing commercial properties — while bringing in third-party capital through REITs and private vehicles.

CEO Michael Smith framed it as a return to first principles. “Today marks the beginning of an exciting new phase of growth for Hongkong Land,” he said. “Building on our 135-year heritage of innovation, exceptional hospitality and longstanding partnerships, our ambition is to become the leader in creating experience-led city centres in major Asian gateway cities that reshape how people live and work.”

CFO Craig Beattie added detail to the capital plan. The company targeted $10 billion over the next decade by disposing of some assets and placing others into investment vehicles. Around $4 billion was expected to come from potential REIT listings or private vehicles backed by premium commercial properties. The remaining $6 billion would come from selling 50 existing projects — mostly residential — along with some mass-market shopping malls in mainland China.

In parallel, Hongkong Land said it aimed to expand assets under management from $40 billion to $100 billion by 2035, with much of that ultimately owned by outside investors rather than sitting permanently on Hongkong Land’s balance sheet. The company also estimated the new model would double profits and dividends.

The market’s verdict was immediate. Shares jumped as much as 17% in Singapore the next morning — the biggest intraday gain in 16 years. That reaction wasn’t just excitement; it was relief. Investors had long questioned why Hongkong Land was pouring capital into cyclical residential development in mainland China when its historical edge was owning and operating prime commercial assets that throw off steady rent.

The reset also tackled a different vulnerability: geographic concentration. With Hong Kong generating 61 percent of underlying operating profit before corporate expenses in 2023, the company said it was aiming for a 40 percent cap on underlying profit before interest and tax from any single city. The expanded commercial portfolio would be anchored by existing flagship investment properties in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Shanghai, with recurring earnings helping fund new projects. The plan also leaned heavily on partnerships — with financial services and luxury tenants, and with Jardine Matheson’s Mandarin Oriental Hotel Group.

Hongkong Land summarized the shift in unusually plain language: simplify the business, focus on Investment Properties in Asia’s gateway cities, and drive long-term recurring income. Practically, that meant no longer investing in build-to-sell — and actively recycling capital out of it into new integrated commercial property opportunities.

In other words: less development risk, more landlord economics, and more fee and management income layered on top.

And the company paired that strategic narrative with something tangible — a reminder that, even as it tried to diversify away from over-dependence on Hong Kong, it still believed the beating heart of its franchise was Central.

Hongkong Land announced “Tomorrow’s CENTRAL,” a plan to invest over US$400 million (HK$3.1 billion) to expand and upgrade its LANDMARK retail portfolio over three years, with phase one beginning in the third quarter of 2024. Tenants across LANDMARK were expected to invest an additional US$600 million (HK$4.7 billion) into new store concepts and fit-outs. The headline feature was the creation of 10 multi-storey “Maison” destinations — designed to give the world’s top luxury houses more space, more presence, and more reasons for customers to visit in person.

Cartier, Chanel, Dior, Hermes, Louis Vuitton, Prada, Saint Laurent, Sotheby’s, Tiffany, and Van Cleef & Arpels were expected to collectively spend about US$600 million on fit-outs. Hongkong Land’s share of the project was US$400 million. The tenants, on average, committed to 10-year leases at The Landmark.

Those lease terms were more than just commercial fine print. They were a signal. When global luxury brands commit for a decade and spend hundreds of millions to build flagship spaces, they’re making a long bet on foot traffic, status, and place — and, by extension, a long bet on Central itself.

The strategic reset, then, wasn’t simply “leave China residential.” It was Hongkong Land trying to reassert the thing that made it powerful in the first place: control of the best addresses, paired with tenants who plan in decades, not quarters.

IX. Key Inflection Point: The Singapore Central Private Real Estate Fund (2024–2025)

A strategy reset only matters if it turns into action. For Hongkong Land, the first real proof point arrived in December 2024, with the announcement of its first private real estate fund: the Singapore Central Private Real Estate Fund, or SCPREF.

In its release, the company positioned SCPREF as a cornerstone of the new model. At inception, it expected the fund to be the largest Singapore private real estate fund, with more than S$8 billion in assets under management. The mandate was narrow by design: prime, downtown Singapore commercial properties — the kind of assets defined less by flashy development upside and more by location, blue-chip tenants, and rental income that holds up across cycles.

The seed portfolio made clear what Hongkong Land was putting on the table. SCPREF was set to be anchored by the company’s one-third stakes in Marina Bay Financial Centre (MBFC) Towers 1 and 2 and One Raffles Quay, plus its 100 percent interest in One Raffles Link. Together, these four office assets in Singapore’s core financial district had a combined attributable value of S$3.9 billion, according to Hongkong Land. And the ambition wasn’t subtle: the company said SCPREF aimed to launch with assets under management more than double the size of that seed portfolio, by bringing in additional assets at inception and over time.

The fund announcement also came alongside a major transaction that showed how the capital-recycling machine would actually work. SGX-listed Keppel REIT exercised its right of first refusal and agreed to buy Hongkong Land’s one-third stake in Marina Bay Financial Centre Tower 3 for S$1.45 billion. Hongkong Land was explicit about why that mattered: Singapore remained a core market, and it planned to redeploy capital from the MBFC Tower 3 sale — and from SCPREF — into ultra-premium, integrated commercial projects in the city.

Put the pieces together and you can see the new playbook taking shape. Between the sale proceeds and third-party equity commitments into SCPREF (which the company said were in the final stage of documentation), Hongkong Land would recycle capital faster, carry less balance-sheet concentration, and earn a new stream of fee income for managing assets — not just owning them.

Financially, the company said net proceeds from the MBFC Tower 3 sale would lift total capital recycling achieved since 2024 to US$2.8 billion, up from US$2.1 billion — roughly 70% of its US$4 billion target for 2027. Strategically, SCPREF fit squarely into the bigger ambition: grow assets under management to US$100 billion by 2035, with meaningful participation from third-party investors.

And this is the real inflection point. SCPREF wasn’t just a Singapore transaction. It was Hongkong Land stepping into a different identity: not only a landlord, but a platform. A company that can package premium assets, bring in outside capital, and scale its footprint without having to keep everything on its own balance sheet.

The open question, of course, is whether this becomes a one-off or a template — and whether Hongkong Land can keep executing at this pace, in other cities, with the same quality of assets and partners.

X. The Jardine Matheson Ecosystem & Keswick Dynasty

To really understand Hongkong Land, you have to understand its controlling shareholder — and the family system that has steered Jardine Matheson for generations.

The Jardines story begins in 1832, when two Scots, William Jardine and James Matheson, founded Jardine, Matheson & Co. in Guangzhou. But the modern power structure that still shapes Hongkong Land flows through a different branch of the family tree: William Jardine’s older sister, Jean Johnstone. Through marriage and inheritance, her descendants became the Keswicks — and over time, the Keswicks became the people who ran Jardines.

That connection starts early. Thomas Keswick entered the Jardine business through marriage into the Johnstone line, and their son, William Keswick, became one of the defining figures of the dynasty. Born in 1834 in Dumfriesshire in the Scottish Lowlands, he arrived in China and Hong Kong in 1855 — the first of five generations of Keswicks to be associated with Jardines. He opened a Jardine Matheson office in Yokohama in 1859, became a partner in Hong Kong in 1862, and served as managing partner, or taipan, from 1874 to 1886.

From there, the Keswicks became a recurring presence wherever Hong Kong’s modern economy was being built. As Jardines evolved from a nineteenth-century trading house into a twentieth-century conglomerate, family members were closely associated with a long list of the territory’s institutional pillars — including, at various times, businesses linked to shipping, insurance, utilities, transport, and property. Hongkong Land sits squarely inside that lineage: it wasn’t just a company the Jardines invested in; it was one the Keswicks helped found and then protected as part of the group’s core.

Fast-forward to the modern era, and the family continuity is still striking. Henry Keswick served as taipan from 1970 to 1975 and later became chairman emeritus. His brother Simon was taipan from 1983 to 1988 — the same Simon Keswick who helped stabilize the group during the early-1980s crisis we just covered. The next generation stayed involved too: Ben Keswick, Simon’s son, became executive chairman of Jardine Matheson Group and served as taipan from 2012 to 2021. Adam Keswick, son of Sir Chips Keswick, was deputy managing director. The organizational chart has changed dramatically since the nineteenth century, but the family influence has not disappeared.

That influence has also been reinforced by ownership and structure. For decades, Jardines used a complex cross-shareholding system designed to make hostile takeovers effectively impossible — and to keep control anchored with the Keswick-led inner circle. The structure drew criticism for years, especially from corporate governance advocates, because it entrenched control and made accountability to minority shareholders feel, at times, optional.

In 2021, that system was finally simplified. Jardine Matheson moved to consolidate Jardine Strategic as a wholly owned subsidiary, unwinding the old cross-holding arrangement where Jardine Matheson owned the majority of Jardine Strategic, and Jardine Strategic in turn owned a large stake in Jardine Matheson. The market largely welcomed the simplification on governance grounds. But the process was controversial: Jardine Matheson offered Jardine Strategic shareholders US$33 per share, and critics argued minority holders had little meaningful say in the outcome. Even so, the end result was clear: fewer layers, a cleaner structure, and a Jardines ecosystem that was easier for investors to understand.

And the Jardines story isn’t just corporate history — it’s cultural mythology. James Clavell drew heavily on the aura and legacy of Jardines for his Asia novels, including Tai-Pan, Whirlwind, Gai-Jin, and Noble House. The Noble House TV miniseries used Jardine House as the headquarters for Struan’s & Co., Clavell’s fictional trading empire. In Taipan, Dirk Struan is loosely based on William Jardine, while Robb Struan is loosely based on James Matheson.

That literary afterlife matters because it captures something true: Jardine Matheson has long occupied a near-mythic place in the story of Hong Kong. And Hongkong Land — the owner of some of the city’s most irreplaceable blocks — is one of the clearest, most tangible expressions of that influence.

XI. The Hong Kong Question: Geopolitical Risk & Current Market Challenges

Hongkong Land’s reset is happening against a backdrop that’s uncomfortable for any company whose identity is tied to one city: Hong Kong’s much-hoped-for post-pandemic rebound hasn’t arrived on schedule. Property prices are still under pressure, and the wider economy is sending mixed signals — enough stabilization to keep deals moving, but not enough confidence to make the weakness feel temporary.

Start with housing, because in Hong Kong, housing is the mood ring. Official data from the Ratings and Valuation Department shows the residential price index fell again in Q1 2025 — the thirteenth straight quarter of year-on-year declines — and it was down even more once you adjust for inflation. On a quarter-on-quarter basis, prices also slipped. Finimize puts the bigger picture in simpler terms: Hong Kong property prices are down nearly 30% from their 2021 peak, a downturn closely linked to slower growth in mainland China and a weaker yuan.

Commercial real estate hasn’t been spared either. In 2024, Hong Kong’s commercial and residential markets continued to consolidate amid high vacancy and a weak economy. Still, there have been real policy and rate-driven tailwinds: the government removed housing “cooling measures,” and recent rate cuts helped lift activity. As Cathie Chung, Senior Director of Research at JLL, put it, 2025 is still defined by oversupply and uncertainty — and the economic and interest rate posture under the new US administration could meaningfully shape housing and investment demand. The more encouraging note: office leasing is expected to improve gradually, with a significant reduction in new office supply anticipated from 2027.

This is where Hongkong Land’s story gets interesting. The company doesn’t need the whole city to be booming if Central is holding up — and so far, its prime portfolio has been more resilient than the broader market. Even as profits declined, its prime assets maintained market-leading occupancy levels.

You can see the “flight to quality” dynamic in the rent data. In Q3, overall rental declines narrowed, while Prime Central rents actually ticked up. More IPO activity should help sentiment and downstream office demand, especially from banking, finance, and professional services — the exact tenant base that tends to pay for the best addresses. Meanwhile, Cushman & Wakefield still expects overall office rents to fall in 2025, given ample new supply and cost-cautious occupiers.

Put differently: Hong Kong is weak, but it’s not weak in a uniform way. The gap between top-tier Central space and everything else is widening. And that divergence is essentially the thesis behind Hongkong Land’s pivot. In choppy markets, quality usually outperforms — and if you’re going to bet on physical place still mattering in the 2020s, there are few places to bet on more than the very best blocks in Central.

XII. Leadership: Michael Smith and the New Direction

If the 2024 reset is about becoming more of a platform — recycling capital, bringing in third-party money, and spinning out assets into REIT-like vehicles — then the leadership question matters a lot. You don’t hand a plan like that to someone who’s only ever been a traditional developer.

Hongkong Land’s pick was Michael Smith, and his resume reads like it was built for this moment: investment banking, fund management, and REIT structuring — the exact toolkit you’d want if you’re trying to pivot from “own everything ourselves” to “own some, manage more, and earn fees on top.”

Hongkong Land appointed Smith as chief executive effective 1 April 2024. The timing was telling. Jardine Matheson’s property unit had just signaled that Hongkong Land expected underlying profit for 2023 to come in below 2022’s underlying profit attributable to shareholders of $776 million — setting up a second straight year of declining returns. Smith replaced Robert Wong, who had joined Hongkong Land’s board as chief executive and executive director in 2016 and departed after a 38-year career with the company. Announcing the change, chairman Ben Keswick framed it around the new mandate: “Michael brings a proven track record in real estate investment and capital allocation.”

Smith brought deep institutional real estate experience from Mapletree Investments, the real estate arm of Singapore’s Temasek. Before joining Hongkong Land, he served as Mapletree’s Regional CEO for Europe and the USA. During his tenure, that business grew to more than a third of Mapletree’s roughly US$55 billion of assets under management.

Before Mapletree, Smith spent decades in investment banking, including as a partner at Goldman Sachs. There, he led Southeast Asia investment banking and the Asia Pacific (ex-Japan) real estate business — a vantage point that put him at the intersection of capital markets and property cycles.

And then there’s the detail that matters most for Hongkong Land’s new playbook: REITs. The company has described Smith as a pioneer of Asia’s REIT industry, having played key roles in multiple listings — including Link REIT in Hong Kong and all four Mapletree REITs in Singapore — plus advisory work across other listed trusts and real estate companies around Asia Pacific.

Investors didn’t miss the signal. Since Smith came on board in April, Hongkong Land’s stock climbed nearly 35 percent. That rebound came off a brutal stretch: shares that were at $7.51 in March 2019 sank to a 15-year low of $2.82 in April.

And the rally had a second leg. After the October strategy announcement, the stock jumped another 17 percent in a single day. Put together, it looked less like a reaction to one announcement and more like the market recognizing something broader: Hongkong Land wasn’t just changing the plan. It was finally putting the plan in the hands of someone built to execute it.

XIII. Investment Framework: Bull Case, Bear Case & Key KPIs

For long-term fundamental investors, Hongkong Land is a study in contrasts: a company with some of Asia’s most irreplaceable real estate — and a set of macro and execution risks that are just as real.

The Bull Case

The optimistic view is built on a few big ideas:

-

Irreplaceable assets: The company’s Central Hong Kong portfolio — roughly 450,000 square meters of premium office and retail — sits on land that was literally created through reclamation more than a century ago. You can renovate it, re-tenant it, and rebrand it. But you can’t recreate it. That scarcity is the foundation of the franchise.

-

The strategic reset actually works: If Hongkong Land can execute on capital recycling and third-party vehicles, it has a path to evolve from a property owner that trades at a discount to its underlying asset value into something closer to a capital-light manager — still collecting rent, but also earning recurring fees.

-

SCPREF becomes the template, not the exception: The Singapore Central Private Real Estate Fund is the first proof point. If it scales, it’s easy to imagine Hongkong Land launching similar structures for Hong Kong and Shanghai assets — turning trophy buildings into engines for both capital recycling and fee income.

-

Luxury retail resilience at the very top: LANDMARK’s business is unusually concentrated in ultra-high-net-worth spending. Very Important Clients spend more than $25,600 per year and account for 80% of LANDMARK sales. That kind of customer base tends to be less sensitive to broad consumer slowdowns.

-

Management fit for the plan: Michael Smith’s background is in capital markets, real estate investing, and REIT structuring — the exact skill set this pivot demands. The bull case assumes that alignment translates into faster execution and more disciplined capital allocation.

The Bear Case

The skeptical view focuses on five categories of risk:

-

Hong Kong’s structural headwinds: Thirteen straight quarters of year-on-year property price declines is hard to wave away as “just the cycle.” Competition from Shenzhen, uncertainty around Hong Kong’s long-term positioning under “one country, two systems,” and talent outflows all threaten the durability of premium valuations — even in Central.

-

China is still in the picture: Exiting build-to-sell reduces exposure, but it doesn’t eliminate it. Hongkong Land still has meaningful mainland risk through projects like West Bund Shanghai and other commercial developments. And the broader China property downturn has not convincingly cleared.

-

Execution risk is the whole ballgame: Turning a 135-year-old landlord and developer into a fund management platform isn’t a slide deck exercise. It requires new capabilities, cultural change, and successful fundraising — all while market conditions are still uncertain.

-

Governance and minority shareholder risk: Jardine Matheson’s control, and the Keswick family’s influence through it, can create misalignment. Critics point to the 2021 Jardine Strategic privatization, which happened at a significant discount to NAV, as a reminder that governance outcomes may not always favor minority shareholders.

-

Interest rate sensitivity: Like all real estate, valuations are exposed to the cost of capital. If rates stay higher for longer, cap rates can expand and asset values can fall, regardless of how well the buildings are run.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW. The Central portfolio is the definition of non-replicable. Between land constraints and a 135-year head start, the barriers are enormous.

Supplier Power: MODERATE. Hong Kong construction is expensive, but Hongkong Land’s scale and reputation help — especially for premium projects and tenant-driven upgrades.

Buyer Power: MODERATE. Top-tier tenants have alternatives, but LANDMARK’s concentration creates its own gravitational pull: brands benefit from clustering where other brands already are.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH. Remote work and digital commerce are real substitutes for traditional office and retail. The counterargument is that the ultra-premium segment tends to hold up better than the mass market — but it’s still a risk.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE. In Central, true peers are limited. Across Asia, competition is broader and well-capitalized — including Swire, Henderson Land, and CapitaLand.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Moderate. A concentrated portfolio and connected buildings create real operating leverage.

Network Effects: Most visible in luxury retail, where clustering turns the district into a destination.

Counter-Positioning: The move toward fund management could differentiate Hongkong Land from traditional owner-operators.

Switching Costs: Moderate. Leases create stickiness, but relocation is always possible at renewal.

Branding: Strong. LANDMARK and Hongkong Land carry premium positioning.

Cornered Resource: Strong. Core Central is the cornered resource.

Process Power: Moderate. Decades of operating premium mixed-use property compounds into know-how that’s hard to copy.

Key KPIs to Monitor

If you’re tracking whether the reset is working, three signals matter most:

-

Capital recycling progress: Hongkong Land targets $4 billion by 2027 and had reached $2.8 billion by December 2024. Hitting that pace is a direct read on execution.

-

Central portfolio occupancy and rental reversion: Occupancy and renewal spreads in Central are the health metrics for the core franchise — and the clearest indicator of whether “flight to quality” is still real.

-

Third-party capital raised: The transition only becomes durable if external investors commit real money to SCPREF and future vehicles. Fundraising success is market confidence, quantified.

XIV. Conclusion: 135 Years and Counting

From Paul Chater taking midnight soundings in Victoria Harbour to Michael Smith building a fund-management playbook, Hongkong Land’s story runs alongside Hong Kong’s own transformation — from colonial entrepôt to global financial center.

It has lived through Japanese occupation, multiple property crashes, takeover threats, the 1997 handover, the Asian Financial Crisis, and now a downturn that has stretched across thirteen straight quarters of year-on-year housing declines. Each shock forced change. And each time, the company protected the same core advantage: control of irreplaceable real estate in the places where Asian commerce concentrates.

That’s why the 2024 reset matters. It isn’t a tweak — it’s the biggest rethink since Simon Keswick’s 1980s rescue. Hongkong Land is trying to move from a balance-sheet-heavy developer to a platform: less build-to-sell risk, more recurring commercial income, and more third-party capital alongside its own. It’s also trying to loosen its dependence on any single city, even as it keeps investing in the beating heart of the franchise.

Near term, the company expected only a partial recovery in underlying profits in 2025, with markets still uncertain and profit levels still well below 2023. The focus, for now, is on the first, practical steps: executing the initial phase of the new strategy and proving the capital-recycling machine works in the real world, not just in presentations.

The fair read is that the risks are real. Hong Kong’s property market may not return to its old peaks. China’s property slump may take years to clear. And shifting into fund management demands flawless execution, especially when sentiment is fragile.

But it’s also hard to ignore what has endured. The Central portfolio that began forming in 1889 is still one of the most valuable collections of commercial real estate in Asia. LANDMARK’s tenant commitments — with hundreds of millions earmarked for new store concepts and fit-outs — show that the very top end of physical retail still believes in place. And the leadership team has been chosen specifically for the new era: capital allocation, structuring, and scaling assets under management.

For 135 years, Hongkong Land’s edge has been patient capital applied to premium locations, reinforced by deep tenant relationships. The next chapter depends on whether it can translate those same strengths into a world where capital is more mobile, work is more flexible, and “prime” has to be re-earned every cycle.

The story continues.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music